Written for the Master’s Programme in Plant and Forest Biotechnology at Umeå University and the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, autumn 2024

INTRODUCTION

As global temperatures are getting increasingly extreme, the molecular strategies that plants have evolved to withstand heat- and chilling stress are becoming insufficient (Ding & Yang, 2022), leading to substantial losses in agricultural yields (Zhao et al., 2017; Hsu & Hsu, 2019) at the same time as the global demand for food is at an all-time high (Ray et al., 2013). To address this issue and enable the development of crop varieties resilient to these new temperature extremes, we need to first chart and understand the molecular pathways underlying the temperature stress (TS) responses.

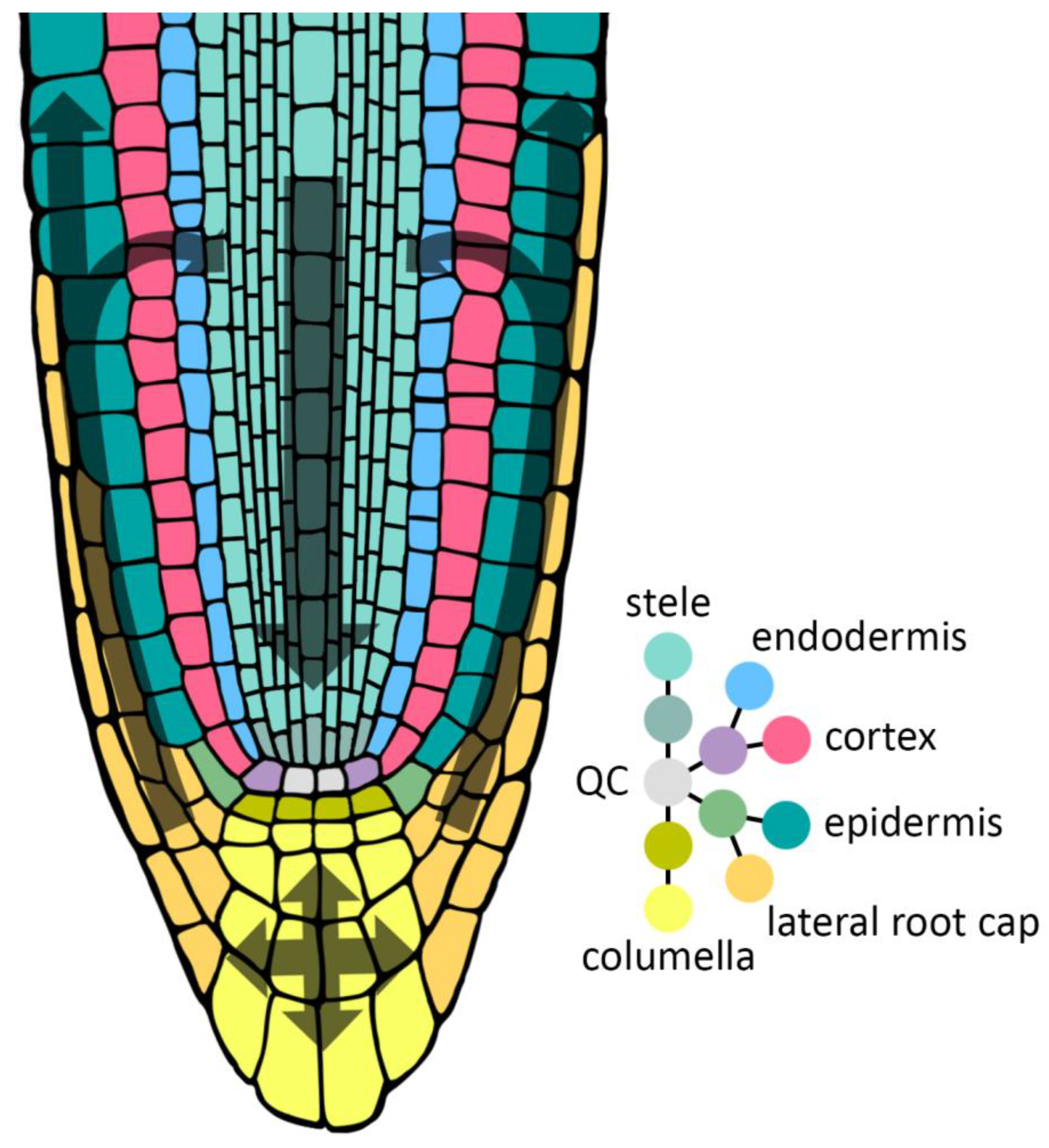

Arabidopsis thaliana, the model species reviewed here, experiences cold stress (CS) in temperatures below 16 °C and heat stress (HS) in temperatures above 28 °C — Any temperature in between these two is called non-stress temperature (Gil & Park, 2018), and any temperature outside of these two will (in the long term) trigger the plant to constrain growth and development to prioritize survival (Figueroa-Macías et al., 2021). This review is focusing on a relatively understudied organ in this field of research: The root (Koevoets et al., 2016), which possesses shoot-independent thermosensory mechanisms (Ai et al., 2023) and contributes significantly to overall plant resilience under TS (Koevoets et al., 2016; Karlova et al., 2021). Here, I will focus specifically on the outer root tissues (ORTs) of

Arabidopsis thaliana and the role that inter- and intracellular auxin transport in these tissues play in TS responses. The ORTs consist of the epidermis, the lateral root cap (LRC) and the columella cells, and these tissues play specific and important roles for root system architecture (Van Den Berg et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2023; Jones et al., 2008) as well as for gravitropic bending (Hanzawa et al., 2013). The flow of auxin through these tissues is part of the “reverse fountain” trajectory, in which shoot-derived auxin travels down towards the root tip (acropetal transport) through the inner tissues (cortex, endodermis and stele) until it reaches the columella cells, where it turns around and travels up through the LRC and the epidermis (basipetal transport) (Van Den Berg et al., 2021;

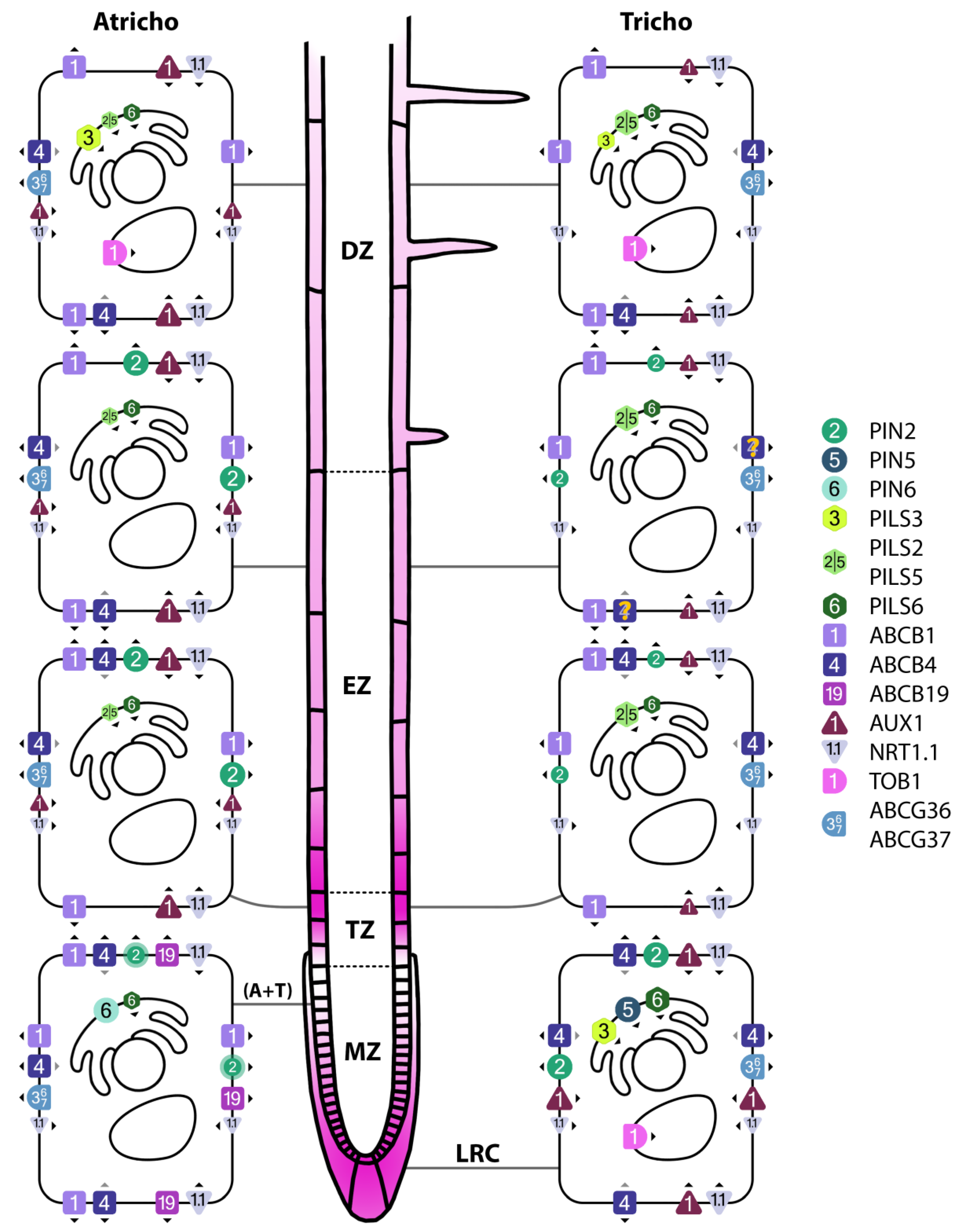

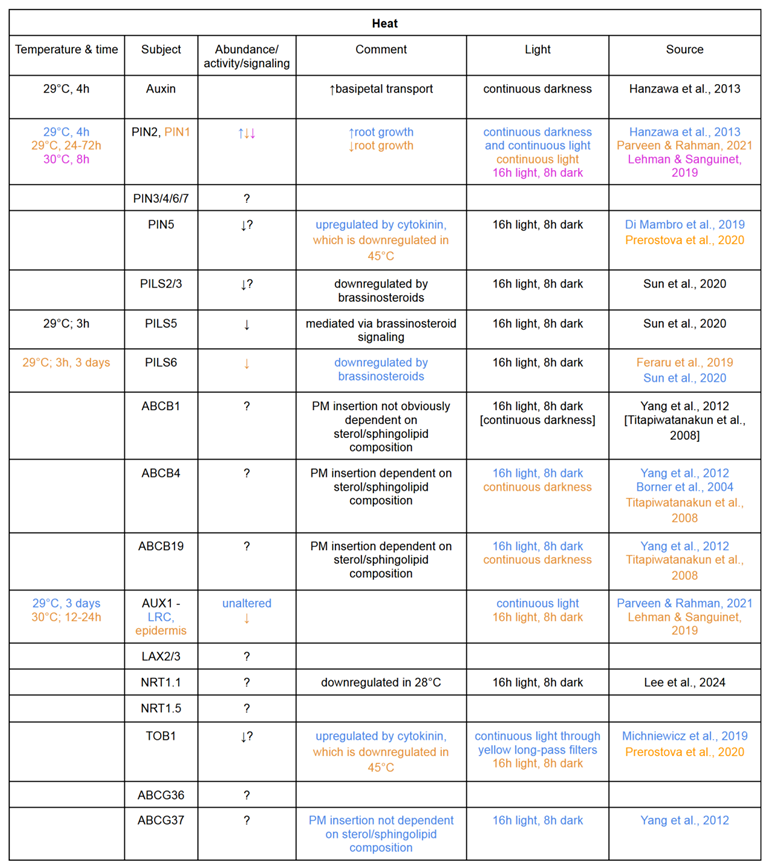

Figure 1 — as shown, some auxin is also recycled back into the inner tissues). The root epidermis is (just like the inner tissues) divided into four developmental zones: The meristematic, transition, elongation and differentiation zone, and consists of root hair-producing trichoblast cells and hairless atrichoblast cells (Jones et al., 2008). The differential auxin concentrations between and along these tissues, zones and epidermal cell types are major determinants for root hair elongation (Jones et al., 2008), gravitropic bending (Hanzawa et al., 2013) and effective priming of lateral root initiation sites (Van Den Berg et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2023), all of which are affected under TS (Koevoets et al., 2016; Pacheco et al., 2023). These differential auxin concentrations are generated and maintained by the many plasma membrane (PM) localized auxin transporters as well as the auxin transporters localized at internal membranes. In this review, I will discuss the current knowledge on the effects of TS on the ORT members of the prominent auxin transporter families PIN-FORMED (PIN), PIN-LIKES (PILS), AUXIN-RESISTANT1 (AUX1), LIKE-AUX1 (LAX) and ATP--binding cassette subfamily B (ABCB), and touch upon what is known about the less prominent transporters TRANSPORTER OF IBA1 (TOB1), NITRATE TRANSPORTER1 (NTR1), and ATP--binding cassette subfamily G (ABCG). Doing so, I aim to provide a comprehensive chart of both explored and unexplored areas of TS-induced changes in auxin transport in the ORTs. For an overview of these changes, see

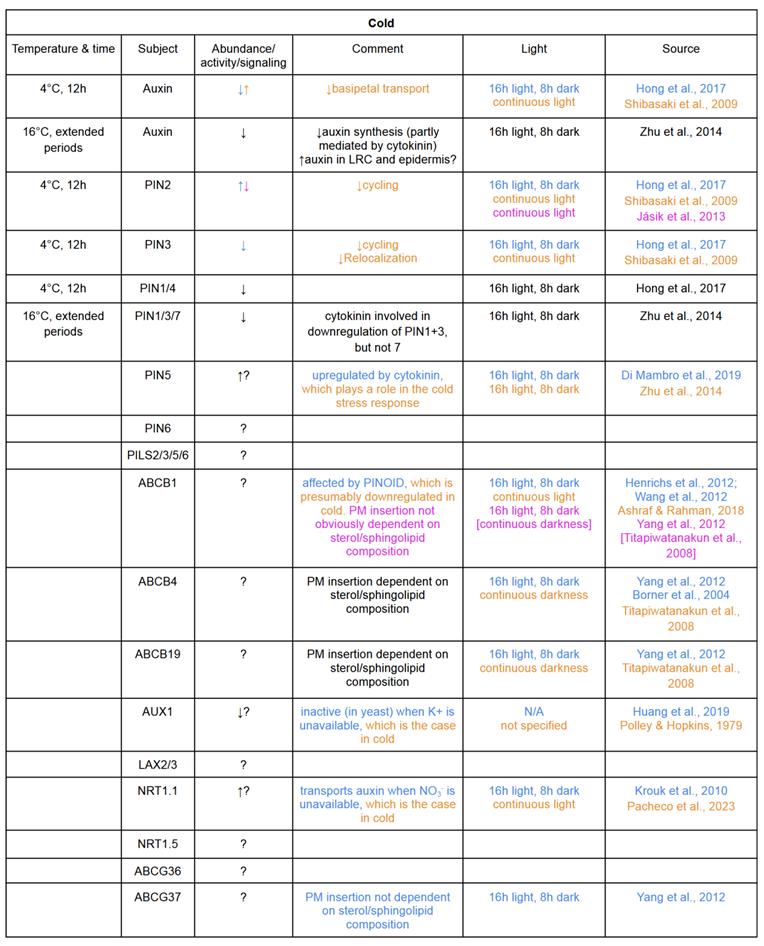

Table 1.

1. LONG-LOOPED PINS

PIN proteins are separated into two subgroups (plus one intermediate member): The long-looped PINs and the short-looped PINs (Hammes et al., 2021). The long-looped PINs are PM localized auxin exporters, which often exhibit strong subcellular polarities and are key players in maintaining and redirecting polar auxin transport (Marhava, 2021). Regulation of long-looped PIN polarity and abundance occurs through a process of continuous recycling and sorting via the vesicular system, a process which is in turn regulated by a multitude of factors (Marhava, 2021) which will be discussed in the coming sections.

The long-looped PIN members in the ORTs are PIN2, PIN3, PIN4 and PIN7. In these tissues, PIN2 is found (apically and inner-plane laterally) in the LRC and epidermis (where it is expressed in a gradient that starts in the meristematic zone and then gradually decreases until it reaches the differentiation zone and disappears; Yuan et al., 2020) (Peng et al., 2024;

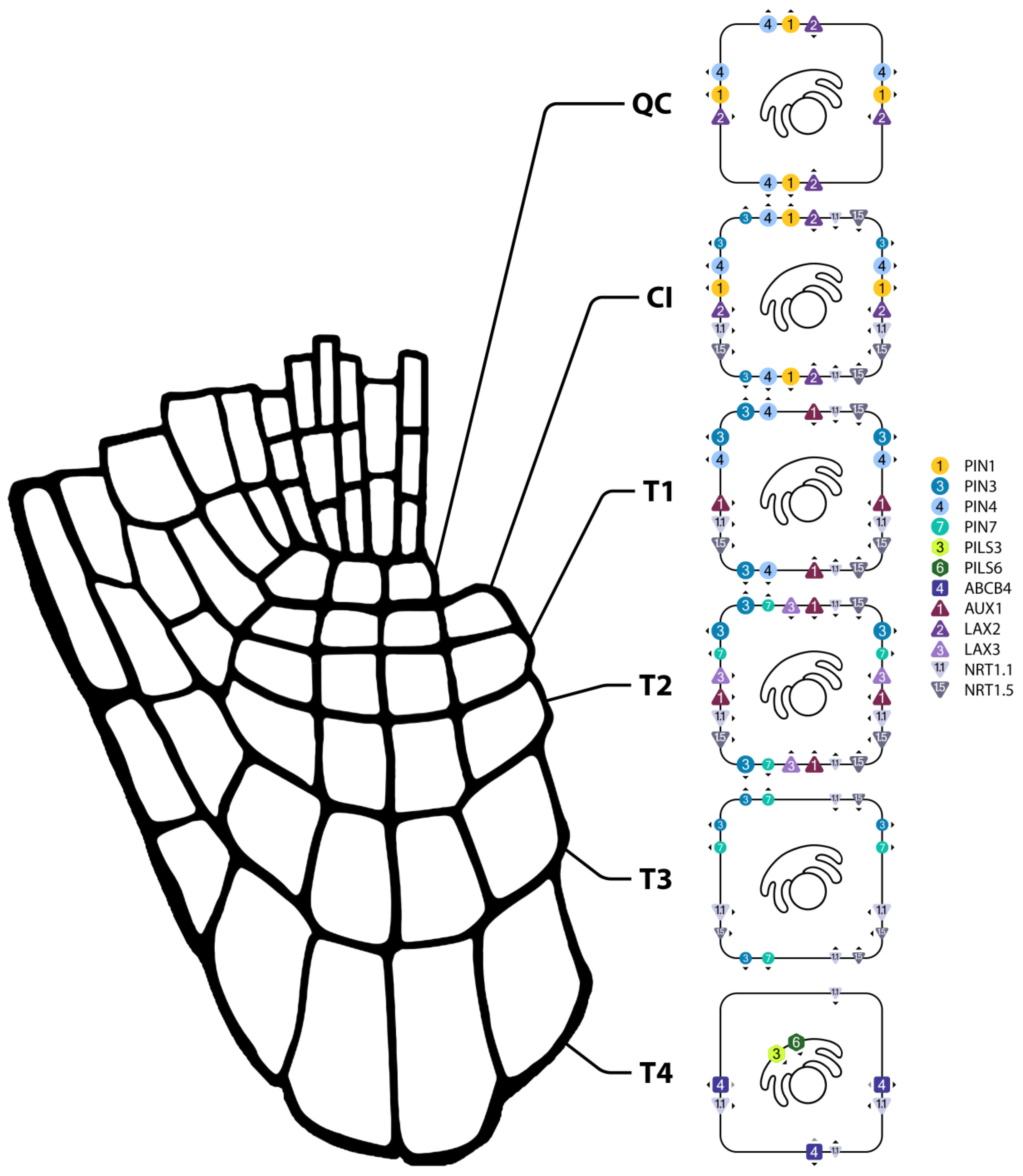

Figure 2). PIN2 also displays a higher abundance in atrichoblasts than trichoblasts (Löfke et al., 2015). PIN3 and 7 are found (apolarly) in semi-overlapping tiers of the columella (Pernisova et al., 2016), and PIN4 is found (apolarly) in the area surrounding the quiescent center (Vieten et al., 2005; Band et al., 2014;

Figure 3). PIN3, 4 and 7 are also found in the inner tissues, where they participate in acropetal transport together with PIN1 (Zhu et al., 2014). Because of this, experimental results involving PIN3/4/7 are often explained in concert with PIN1, and I will therefore at times mention the TS responses of this inner-tissue PIN as well.

A last note on the general behaviours of long-PINs is that they act in synergy with ABCBs (a different type of auxin transporter, discussed in detail below), resulting in more-than-sum auxin efflux in locations where both transporters are present (Mellor et al., 2022). So, it is important to keep in mind that any change in PIN abundance will also affect the transport capacities of ABCBs.

1.1. Increased PIN Clustering/Abundance Might Not Increase Auxin Efflux

Intuitively, a high degree of PIN signal at the PM would be expected to correlate with a high degree of auxin efflux. However, in a study by Ke et al. (2020), high PIN2 signal at the PM was equated to a high degree of PIN2 nanodomain clustering (a phenomenon that affects, among other things, the cycling of PINs; Li et al., 2020; Ke et al., 2020), and this increase in abundance/clustering was counter-intuitively found to be correlated with lower rates of auxin transport. This inverse correlation between clustering and auxin transport has been noted also elsewhere, but the opposite relationship has been noted as well (Li et al., 2020). Hence, before I discuss the effects of TS on PM PIN abundance, I would like to emphasize that an increase in abundance does not necessarily imply an increase in auxin transportation.

On the topic of clustering, an important observation is that Ke et al. (2020) found a reduction in PIN2 clustering in the presence of Mβcd, a compound that perturbs the integrity of lipid rafts and consequently allows PM-bound proteins to diffuse more freely along the PM. Salicylic acid, on the other hand, which increased clustering and reduced internalization, was found to cause a general reduction in PM protein motility. One could therefore speculate that PM integrity, which is strongly affected by temperature (Dufourc, 2008), is a determinant of PIN clustering and consequently also the clustering-dependent inhibition of internalization. In experiments with the PM rigidifier DMSO, however, results have been mixed: While Jásik et al. (2013) reported a significant inhibition on PIN2 internalization by DMSO, the same could not be observed by Shibasaki et al. (2009). Nevertheless, the lipid composition of cell membranes seems to be integral for proper PIN trafficking, given the abhorrent PIN2 polarization in the sterol synthesis-defective cpi1 (Men et al., 2008), and the dramatically reduced abundances of PIN1 and PIN3 in ctl1, a mutant defective in several aspects of lipid synthesis and homeostasis (Y. Wang et al., 2017).

1.2. Cold Stress Affects PIN Abundance and Auxin Distribution in a Variable Manner

Several studies have investigated the effects on long-looped PINs in the specific conditions of 12 hours at 4 °C. While Jásik et al. (2013) reported a decrease in overall PIN2 abundance and turnover rate at the PM in these conditions, Hong et al. (2017) observed an increase in PIN2 abundance along with a decrease in PIN1/3/4/7. The results by Hong and colleagues were accompanied by reduced levels of auxin in the root apex, which is inconsistent with the increased levels of auxin reported by Shibasaki et al. (2009). The latter group also found that the cold treatment caused endosomal cycling of (specifically) PIN2 and 3 to be absent, the relocalization of PIN3 in response to gravity to be diminished, and the related redistribution of auxin to be delayed. The auxin accumulation in the apex was explained by a >50% decrease in basipetal auxin transport. In a screening assessing the rate of root growth recovery of mutants in these same conditions, pin4, but not eir-1 (a PIN2 mutant) or pin3, showed a (slight but) statistically significant decrease in root growth recovery (Aslam et al., 2020). When Zhu et al. (2014) subjected plants to 16 °C for extended periods of time, both auxin synthesis genes and the expression of PIN1/3/7 were reduced in roots, which manifested as reduced auxin accumulation in the root apex (although the images with IAA2::GUS hint at a relative increase of auxin in the LRC and epidermis) and inhibition of root growth. This inhibition of root growth was to a large extent decreased in pin1pin3pin7, to a lesser extent decreased in pin1, and not significantly decreased in pin3 or pin7. Cytokinin signaling mutants arr1 and arr12 were resistant to the cold-induced phenotype, and this resistance was correlated with increased expression of PIN1 and 3 as well as two genes related to auxin synthesis. Lastly, microtubules are important for proper clustering of PIN2 at the PM (Li et al., 2020) and in a study by Kleine-Vehn et al. (2008), microtubule disruption led to the appearance of PIN2-positive bodies in epidermis cells. This, taken together with the fact that (12 hours of 4 °C) cold stress severely disrupted microtubules in the cortex (Shibasaki et al., 2009), implies that microtubules might affect the clustering of epidermal PIN2 during cold stress.

1.3. SORTING NEXIN1 and Actin Mediate the Heat Stress Responses of Long-Looped PINs

Hanzawa et al. (2013) reported that in plants subjected to a four-hour exposure to 29 °C, PIN2 was rerouted from late endosomes to the PM in a SORTING NEXIN1-dependent manner, which increased the rate of basipetal transport, root growth, gravity-dependent redistribution of auxin and gravitropic bending. According to Parveen and Rahman (2021), this initial increase in root growth at 29 °C is temporary; after 24 hours, the growth rates are reversed, with control roots elongating at a rate higher than the roots subjected to heat. They also found that ACT7, a vegetative actin, participates in the heat stress response: In act7, the heat-induced post-transcriptional downregulations of PIN1 and PIN2 were increased relative to controls, especially in the case of PIN2. While the abundances were decreased, there was no effect on localization. Considering the observation by Shibasaki et al. (2009) that actin organization in root cells was unaffected after 12 hours at 4 °C, it seems that the role of actin in TS is heat stress-specific. Furthermore, data from Lehman and Sanguinet (2019) indicate a significant decrease in PIN2 abundance after an eight-hour exposure to 30 °C. PIN abundances are also (differentially) dependent on HSP90-7 (Noureddine et al., 2024), a heat shock protein which when overexpressed confers resistance to short-term 45 °C heat stress (Chong et al., 2014).

2. SHORT- AND INTERMEDIATE-LOOPED PINS

Under their native promoters, short-looped PINs localize intracellularly, at the ER membrane, and regulate the availability of free auxin in the cytoplasm (Seifu et al., 2024). (For reports on PM localization, see Ganguly et al. (2010) and Ganguly et al. (2014).) To date, PIN5 is the only short-looped PIN confirmed to be present in ORTs, specifically in the LRC, where it decreases the cytoplasmic availability of auxin by transporting it into the ER (Di Mambro et al., 2019;

Figure 2). Although there is a complete lack of research regarding the TS responses of PIN5, its abundance appears to be exceptionally dependent on HSP90-7 (Chong et al., 2014). Additionally, the LRC activity of PIN5 was shown to be upregulated by cytokinin (Di Mambro et al., 2019), through (at least partially) the same pathway that limited the expression of PIN1 and 3 during 16 °C cold stress (Zhu et al., 2014). Cytokinin is also downregulated in roots after 3 hours of 45 °C heat stress (Prerostova et al., 2020).

The last PIN of the ORTs, PIN6, has an intermediate loop and can localize both to the PM and the ER (Ditengou et al., 2017). In the ORTs, it is present in low amounts in the meristematic epidermis, and unless overexpressed it localizes to the ER in this tissue (Ditengou et al., 2017;

Figure 2). While the direction of PIN6-mediated auxin at the ER is not clearly elucidated, the increase of (lateral) root tip auxin in

pin6 (Simon et al., 2016) might indicate that PIN6 transports auxin into the ER. Notably, though, PIN6 overexpression induces a similar increase in auxin (Simon et al., 2016; Ditengou et al., 2017), but Ditengou and colleagues suggested that this might be explained by the basal PM localization that PIN6 exhibits in the LRC and distal half of the meristem under overexpression. Unfortunately, no research has been conducted on the TS responses of PIN6, so the primary contribution of this article to the existing knowledge on PIN6 is limited to the detailing of its localization and directionality of transport.

3. PILS

Like PIN5, PILS2/3/5 and 6 are localized at the ER membrane and regulate intracellular auxin availability by removing auxin from the cytoplasm (Barbez et al., 2012; Feraru et al., 2019). PILS2 and PILS5 act redundantly (Barbez et al., 2012), and their genes are expressed in the transition, elongation and differentiation zones of the epidermis (Sun et al., 2020; See Barbez et al. for PILS5 localization in transition zone;

Figure 2). Although not easy to assess in the article images, data from The Bio-Analytic Resource for Plant Biology indicate higher expression in trichoblasts (BAR, 2007). PILS3 is expressed in the LRC and the outermost tier of the columella (Kumar et al., 2023), and BAR data indicate expression in the differentiation zone as well (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3), with slightly higher expression in atrichoblasts. PILS6 is ubiquitously expressed in the root tip, but expression appears to be most prominent in the LRC and outermost tier of the columella (Feraru et al., 2019;

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

In their 2020 study, Sun and colleagues found that brassinosteroid treatment triggers a transcriptional and posttranslational downregulation of PILS proteins 2-6. This same kind of downregulation had previously been described for PILS6, but in response to short (3h) and long (three-day) exposure to 29 °C (Feraru et al., 2019). This led Sun and colleagues to investigate further, and indeed, they found that an analogous downregulation of PILS5 in the short-term heat conditions was mediated via brassinosteroid signaling. They did not investigate the connection to heat in relation to other PILS proteins, but under the assumption that the same pathway goes for all, it is relevant to mention that PILS3 and 5 were more strongly affected by the (21 °C) brassinosteroid treatment than PILS2 and 6. In terms of effects on auxin signaling, however, only the pils2pils3pils5 triple mutant and PILS6OE line displayed clear (relative) differences in auxin signaling/abundance in response to brassinosteroid treatment: In the triple mutant, auxin signaling was increased, and in PILS6OE, auxin abundance was decreased.

4. ABCB

ABCBs are PM localized auxin efflux transporters with zone-dependent polarities (Terasaka et al., 2005; Geisler & Murphy, 2005) that act in synergy with PINs, leading to more-than-sum auxin efflux in locations where both transporters are present (Mellor et al., 2022). Of the three most extensively studied ABCBs found in the ORTs, ABCB1, ABCB4 and ABCB19, ABCB4 is the only one showing expression exclusively in these tissues (Mellor et al., 2022). It is found in the epidermis, lateral root cap and outermost tier of the columella (Cho et al., 2007;

Figure 2 and

Figure 3), contributes greatly to basipetal auxin transport and can remarkably exhibit auxin influx capacity when auxin concentrations are low (Kubeš et al., 2011). Notably,

ABCB4 expression appears to be absent from trichoblasts in the elongation zone (Terasaka et al., 2005). The other two well-known ABCBs, ABCB1 and ABCB19, are present in all three zones of the epidermis (Geisler & Murphy, 2005) and in the epidermal meristem, respectively (Mellor et al., 2022; Kim et al., 2010). However, both transporters also show strong expression in the inner tissues, and only ABCB1 contributes to basipetal transport (Kubeš et al., 2011). Although research is lacking regarding the TS responses of ABCBs, the insertion of ABCB4 and ABCB19 (but not obviously ABCB1) into the PM is dependent on sterol- and sphingolipid-enriched ordered membrane domains (Yang et al., 2012; Borner et al., 2004; Titapiwatanakun et al., 2008), which are in turn affected by temperature (Dufourc, 2008). Thus, it is likely that the abundances of ABCB4 and 19 are affected by temperature as well, which would consequently affect the efflux capacity of PIN2.

Although only a relatively small portion of ABCB1 and ABCB19 expression is found in the epidermis, it can be worth a mention that these transporters have recently been shown to participate not only in auxin efflux, but also in the efflux of brassinosteroids and the positive regulation of brassinosteroid signaling (Ying et al., 2024). (The experiments were mostly focused on ABCB19, but ABCB1 was indicated to participate as well. ABCB4 was shown not to participate.) As brassinosteroid signaling is involved not only in the regulation of PIN2 (Retzer et al., 2019) and the PILS proteins (Sun et al., 2020), but also generally participates in both heat and cold stress responses (Planas-Riverola et al., 2019), an involvement of ABCB1 and ABCB19 in TS responses is possible. Furthermore, the PM abundance of both proteins was shown to be affected by (inversely correlated with) brassinosteroid concentration, which, considering again the synergistic effects between PINs and ABCBs, might affect also the efflux capacities of PINs. Again, though, these effects would probably be more pronounced in acropetal transport. An additional note on ABCB1 is that its activity and synergy with PINs are affected by the AGC kinase PINOID (Henrichs et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2012), which is upregulated during inhibition of GNOM, an ARF-GEF that is downregulated in cold (Ashraf & Rahman, 2018).

Notably, auxin exporters ABCB1/4/19 display an analogous downregulation and compartmentalization in act7 as seen in PIN2, with an especially dramatic reduction of ABCB4 (Zhu et al., 2016). Whether this downregulation also becomes more pronounced in response to an increase in temperature, however, remains to be investigated.

Recently, five additional ABCBs with specific and overlapping expression domains have been found to participate in auxin transport through (almost exclusively!) the ORTs (Chen et al., 2023). As information about both their zone-specific subcellular localizations and TS responses are lacking, they are not included in

Figure 2 and will not be discussed further in this review, but their tissue-specific expression patterns can be found in the article by Chen and colleagues. Notably, one of these ABCBs are (in the ORTs) specific only for trichoblasts.

5. AUX1/LAX

The AUX1/LAX family of auxin importers consists of four members, of which three are present in the ORTs: AUX1, LAX2 and LAX3. AUX1 is present in the LRC, the first two tiers of the columella and all three zones of the epidermis (Band et al., 2014), and while AUX1 is completely apolar in the latter two tissues, it is regularly enriched at both apical and basal cell planes in the epidermis (Kleine-Vehn et al., 2006;

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). When the cell-type specific distribution of AUX1 is assessed by microscopy, it appears to be present only in atrichoblasts (Jones et al., 2008). A membrane potential-based approach, however, showed that AUX1 is likely present in trichoblasts as well, but in lower amounts (Dindas et al., 2018). LAX2 is localized in an apolar manner at the quiescent center and columella initials, and LAX3, also apolar, is localized at the second tier of the columella (

Figure 3). While there is a complete lack of information on the TS responses of LAX2 and 3, more is available on AUX1:

Parveen and Rahman (2021) found that a three-day exposure to 29 °C did not alter AUX1 abundance in the LRC (in neither WT nor act7). Meanwhile, data from Lehman and Sanguinet (2019) indicate a significant reduction in epidermal AUX1 signal after 12 and 24 hours at 30 °C. This reduction might be linked to an observation made by Hanzawa et al. (2013), who noted a diminished increase in root elongation and basipetal auxin transport in aux1 plants subjected to a four-hour exposure to 29 °C. A relative decrease in aux1 primary root growth was also seen in an experiment by Krishnamurthy and Rathinasabapathi (2013), where they first subjected the plants to 1 hour of 37 °C heat stress and then allowed them to grow in non-stress temperature for three days. Notably, they also observed a significant increase in the relative amount of lateral roots produced by aux1 after the treatment. Furthermore, AUX1 abundance was decreased in both hsp90-7 (Chong et al., 2014) and cytokinin-deficient mutants (Pernisova et al., 2016), and intracellular AUX1 aggregates were seen in plants deficient in sphingolipids (Yang et al., 2012). In a heterologous study with yeast, results also indicated that upon binding to K+, AUX1 undergoes a conformational change which increases transport capacity and protects it from heat-induced deterioration (Huang et al., 2019).

There is no direct information regarding the cold stress responses of AUX1 in Arabidopsis, except that it does not appear to be involved in root growth recovery after 12 hours at 4 °C (Aslam et al., 2020). During 4 °C cold stress, however, root uptake of K+ is severely hampered (Polley & Hopkins, 1979), which in light of the results by Huang and colleagues could mean that the conformation of AUX1 is in its closed, relatively inactive state when temperatures are low.

6. NRT1.1

NRT1.1 is a dual-affinity PM localized nitrate transceptor that, in low nitrate conditions, also transports auxin (but not the other way around; nitrate will outcompete auxin, but auxin will not outcompete nitrate, even at high levels) (Krouk et al., 2010).

NRT1.1 is expressed in all layers of the root cap and zones of the epidermis (Guo et al., 2001; Krouk et al., 2010) and might be preferentially located at the anticlinal cell planes (Krouk et al., 2010; S. Lee et al., 2024;

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). Although NRT1.1 was found to facilitate auxin influx, the NRT1.1 mutant

chl1-5 displayed increased levels of auxin in the root tip (Krouk et al., 2010). The authors thus suggested that the NRT1.1-mediated influx contributes to basipetal auxin transport.

In 10 °C, the availability of nutrients—including nitrate—decreases, and root hair growth increases (Pacheco et al., 2023). This cold-induced increase in root hair growth was exacerbated in low-nitrate conditions and partially inhibited by the addition of high levels of nitrate, suggesting a specific connection between nitrate signaling and root hair growth (Pacheco et al., 2023). Experiments with NRT1.1 mutants further supported this: mutants impaired in nitrate transport or signaling displayed no differences in root hair growth in response to either nitrate availability or temperature changes. Considering the capacity of NRT1.1 to transport auxin in conditions of low nitrate, and the fact that root hairs elongate in response to auxin (Ganguly et al., 2010), it is tempting to speculate that the increase in root hair growth was caused not only by (a lack of) nitrate signaling, but also by an NRT1.1-mediated increase in basipetal auxin transport. Whether this is the case or not, however, remains to be investigated.

Research on the responses of NRT1.1 to heat stress is lacking. However, a study in 28 °C showed that downregulation of NRT1.1 is an important part of thermomorphogenesis, the adaptive strategy that promotes root growth in response to elevated non-stress temperature (S. Lee et al., 2024). Notably, low-nitrate conditions inhibited both the downregulation of NRT1.1 and the increase in root growth. Whether this is somehow connected to the auxin-transporting capacity of NRT1.1 constitutes a question for future research.

7. IBA Transporters TOB1, NRT1.5, ABCG36 and ABCG37

In addition to transporters that facilitate the movement of auxin, several transporters are known to mediate the transport of indole-3-butyric acid (IBA), an auxin precursor, between and within the cells of the ORTs. These transporters are TOB1, NRT1.5, ABCG36 and ABCG37. TOB1 is localized at the vacuolar membrane in the LRC and (based on gene expression) the epidermal differentiation zone, and is suspected to facilitate IBA transport into the vacuole (Michniewicz et al., 2019; BAR, 2007;

Figure 2). The PM localized NRT1.5 is expressed in the columella initials and the first three tiers of the columella, and facilitates import of IBA (Watanabe et al., 2020;

Figure 3). ABCG36 and ABCG37, also localized at the PM, function in IBA efflux (Růžička et al., 2010), and can be found in the outer plane of LRC and epidermal cells in all four developmental zones (Růžička et al., 2010; Strader & Bartel, 2009; Aryal et al., 2023; BAR, 2007;

Figure 2).

There is not much information available regarding the TS responses of these less established (but in many cases, highly influential) transporters. Two things, however, can be said: Firstly, TOB1 displays a clear upregulation in response to cytokinin (Michniewicz et al., 2019), which as previously mentioned plays a role in the cold stress response (Zhu et al., 2014) and is downregulated at elevated temperatures (Prerostova et al., 2020). Secondly, ABCG37 abundance is not affected by the inhibition of sterol- or sphingolipid synthesis (Yang et al., 2012), suggesting a tolerance towards temperature-induced changes in PM composition.

8. DISCUSSION

In these times of climate change, successful development of crops resilient to our increasingly extreme temperatures is nothing less than a matter of life and death for many people across the world. It is, therefore, of utmost importance that the molecular mechanisms affecting the TS tolerances of plants are elucidated, and as a step in this direction, I have in this review collected and visualized our scattered fragments of knowledge concerning the subcellular localizations and TS responses of the auxin transporters in the ORTs of

Arabidopsis thaliana. To allow for intuitive assessment of the collective contributions of ORT transporters to the distribution of auxin, I also created a comprehensive graphic (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). The original plan for this graphic actually entailed four additional, analogous figures showing also the cold- and heat-induced alterations in auxin and transporter abundances, but this proved difficult as these factors often manifest in diametrically different ways even in experiments with seemingly identical conditions — See, for example, the account on the cold stress responses of long-looped PINs in section 1.2.

An explanation of these differences could lie in the third, insofar unmentioned experimental condition: light (

Table 1). Several studies have shown that light substantially and differentially affects the abundances of auxin transporters; For example, PIN1, PIN2 (Sassi et al., 2012), PIN7 (Laxmi et al., 2008) and PILS2/3/5 are all downregulated in the absence of light (Béziat et al., 2017), while AUX1 (Laxmi et al., 2008) and ABCB4 are not (Kubeš et al., 2011). In addition to this, Hanzawa et al. (2013) found that the dark-induced downregulation of PIN2 was inhibited under high temperatures, adding an additional layer of complexity to the network. I therefore encourage anyone working with TS and auxin transporters to thoroughly review available literature on the effects of different light conditions before deciding on lighting specifics for their own experiments.

Apart from the obvious gaping holes in our knowledge regarding the TS responses of many of the transporters discussed in this review, there are also more specific avenues of research that could be investigated in the future.

These entail, whether:

the disruption of microtubules in cold stress has any effect on PIN2 clustering

the cold-induced upregulation and heat-induced downregulation of cytokinin causes a respective upregulation and downregulation of PIN5, AUX1 and TOB1

ACT7 regulates the abundance of ABCB1, ABCB4 and ABCB19 during heat stress

the transporting capacity of AUX1 is reduced in low temperatures as a consequence of the low availability of K+

NRT1.1-dependent auxin transport contributes to the increased root hair growth and inhibition of root thermomorphogenesis seen at 10 °C and 28 °C, respectively, under conditions of low nitrate.

As a concluding remark, I would like to say that of course, the ORTs do not operate in a vacuum. Rather, the availability of auxin in the ORTs is to a large extent dependent on acropetal transport and auxin derived from the shoot, especially in the early days of the seedling before the root apex has become competent in auxin synthesis (Bhalerao et al., 2002). I would therefore like to encourage the creation of a complementary review, focusing on the subcellular localizations and TS responses of the transporters in the inner root tissues.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Valdemar Askeljung for providing me with sustenance in times of academic stress.

References

- Ai, H., Bellstaedt, J., Bartusch, K. S., Eschen--Lippold, L., Babben, S., Balcke, G. U., Tissier, A., Hause, B., Andersen, T. G., Delker, C., & Quint, M. (2023). Auxin--dependent regulation of cell division rates governs root thermomorphogenesis. The EMBO Journal, 42(11), e111926. [CrossRef]

- Aryal, B., Xia, J., Hu, Z., Stumpe, M., Tsering, T., Liu, J., Huynh, J., Fukao, Y., Glöckner, N., Huang, H., Sáncho-Andrés, G., Pakula, K., Ziegler, J., Gorzolka, K., Zwiewka, M., Nodzynski, T., Harter, K., Sánchez-Rodríguez, C., Jasiński, M., . . . Geisler, M. M. (2023). An LRR receptor kinase controls ABC transporter substrate preferences during plant growth-defense decisions. Current Biology, 33(10), 2008–2023.e8. [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M. A., & Rahman, A. (2018). Cold stress response in Arabidopsis thaliana is mediated by GNOM ARF-GEF. The Plant Journal, 97(3), 500–516. [CrossRef]

- Aslam, M., Sugita, K., Qin, Y., & Rahman, A. (2020). AUX/IAA14 regulates microRNA-Mediated Cold Stress response in Arabidopsis roots. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(22), 8441. [CrossRef]

- Band, L. R., Wells, D. M., Fozard, J. A., Ghetiu, T., French, A. P., Pound, M. P., Wilson, M. H., Yu, L., Li, W., Hijazi, H. I., Oh, J., Pearce, S. P., Perez-Amador, M. A., Yun, J., Kramer, E., Alonso, J. M., Godin, C., Vernoux, T., Hodgman, T. C., . . . Bennett, M. J. (2014). Systems analysis of Auxin transport in the Arabidopsis Root Apex [Supplemental material]. The Plant Cell, 26(3), 862–875. [CrossRef]

- Barbez, E., Kubeš, M., Rolčík, J., Béziat, C., Pěnčík, A., Wang, B., Rosquete, M. R., Zhu, J., Dobrev, P. I., Lee, Y., Zažímalovà, E., Petrášek, J., Geisler, M., Friml, J., & Kleine-Vehn, J. (2012). A novel putative auxin carrier family regulates intracellular auxin homeostasis in plants. Nature, 485(7396), 119–122. [CrossRef]

- Béziat, C., Barbez, E., Feraru, M. I., Lucyshyn, D., & Kleine-Vehn, J. (2017). Light triggers PILS-dependent reduction in nuclear auxin signalling for growth transition. Nature Plants, 3(8), 17105. [CrossRef]

- Bhalerao, R. P., Eklöf, J., Ljung, K., Marchant, A., Bennett, M., & Sandberg, G. (2002). Shoot--derived auxin is essential for early lateral root emergence in Arabidopsis seedlings. The Plant Journal, 29(3), 325–332. [CrossRef]

- Borner, G. H., Sherrier, D. J., Weimar, T., Michaelson, L. V., Hawkins, N. D., MacAskill, A., Napier, J. A., Beale, M. H., Lilley, K. S., & Dupree, P. (2004). Analysis of Detergent-Resistant membranes in Arabidopsis. Evidence for plasma membrane lipid rafts. PLANT PHYSIOLOGY, 137(1), 104–116. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., Hu, Y., Hao, P., Tsering, T., Xia, J., Zhang, Y., Roth, O., Njo, M. F., Sterck, L., Hu, Y., Zhao, Y., Geelen, D., Geisler, M., Shani, E., Beeckman, T., & Vanneste, S. (2023). ABCB--mediated shootward auxin transport feeds into the root clock. EMBO Reports, 24(4), e56271. [CrossRef]

- Cho, M., Lee, S. H., & Cho, H. (2007). P-Glycoprotein4 displays Auxin Efflux Transporter–Like action in arabidopsis root hair cells and tobacco cells. The Plant Cell, 19(12), 3930–3943. [CrossRef]

- Chong, L. P., Wang, Y., Gad, N., Anderson, N., Shah, B., & Zhao, R. (2014). A highly charged region in the middle domain of plant endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-localized heat-shock protein 90 is required for resistance to tunicamycin or high calcium-induced ER stresses. Journal of Experimental Botany, 66(1), 113–124. [CrossRef]

- Di Mambro, R., De Ruvo, M., Pacifici, E., Salvi, E., Sozzani, R., Benfey, P. N., Busch, W., Novak, O., Ljung, K., Di Paola, L., Marée, A. F. M., Costantino, P., Grieneisen, V. A., & Sabatini, S. (2017). Auxin minimum triggers the developmental switch from cell division to cell differentiation in the Arabidopsis root. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(36), E7641–E7649. [CrossRef]

- Di Mambro, R., Svolacchia, N., Ioio, R. D., Pierdonati, E., Salvi, E., Pedrazzini, E., Vitale, A., Perilli, S., Sozzani, R., Benfey, P. N., Busch, W., Costantino, P., & Sabatini, S. (2019). The Lateral Root Cap Acts as an Auxin Sink that Controls Meristem Size. Current Biology, 29(7), 1199–1205.e4. [CrossRef]

- Dindas, J., Scherzer, S., Roelfsema, M. R. G., Von Meyer, K., Müller, H. M., Al-Rasheid, K. a. S., Palme, K., Dietrich, P., Becker, D., Bennett, M. J., & Hedrich, R. (2018). AUX1-mediated root hair auxin influx governs SCFTIR1/AFB-type Ca2+ signaling [Supplemental material]. Nature Communications, 9(1), 1174. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y., & Yang, S. (2022). Surviving and thriving: How plants perceive and respond to temperature stress. Developmental Cell, 57(8), 947–958. [CrossRef]

- Ditengou, F. A., Gomes, D., Nziengui, H., Kochersperger, P., Lasok, H., Medeiros, V., Paponov, I. A., Nagy, S. K., Nádai, T. V., Mészáros, T., Barnabás, B., Ditengou, B. I., Rapp, K., Qi, L., Li, X., Becker, C., Li, C., Dóczi, R., & Palme, K. (2017). Characterization of auxin transporter PIN6 plasma membrane targeting reveals a function for PIN6 in plant bolting. New Phytologist, 217(4), 1610–1624. [CrossRef]

- Dufourc, E. J. (2008). The role of phytosterols in plant adaptation to temperature. Plant Signaling & Behavior, 3(2), 133–134. [CrossRef]

- Feraru, E., Feraru, M. I., Barbez, E., Waidmann, S., Sun, L., Gaidora, A., & Kleine-Vehn, J. (2019). PILS6 is a temperature-sensitive regulator of nuclear auxin input and organ growth in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(9), 3893–3898. [CrossRef]

- Figueroa-Macías, J. P., García, Y. C., Núñez, M., Díaz, K., Olea, A. F., & Espinoza, L. (2021). Plant Growth-Defense Trade-Offs: molecular processes leading to physiological changes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(2), 693. [CrossRef]

- Friml, J., Benková, E., Blilou, I., Wisniewska, J., Hamann, T., Ljung, K., Woody, S., Sandberg, G., Scheres, B., Jürgens, G., & Palme, K. (2002). ATPIN4 mediates Sink-Driven AUxIn gradients and root patterning in Arabidopsis. Cell, 108(5), 661–673. [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, A., Lee, S. H., Cho, M., Lee, O. R., Yoo, H., & Cho, H. (2010). Differential Auxin-Transporting activities of PIN-FORMED proteins in arabidopsis root hair cells. PLANT PHYSIOLOGY, 153(3), 1046–1061. [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, A., Park, M., Kesawat, M. S., & Cho, H. (2014). Functional analysis of the hydrophilic loop in intracellular trafficking of arabidopsis PIN-FORMED proteins. The Plant Cell, 26(4), 1570–1585. [CrossRef]

- Geisler, M., & Murphy, A. S. (2005). The ABC of auxin transport: The role of p--glycoproteins in plant development. FEBS Letters, 580(4), 1094–1102. [CrossRef]

- Gil, K., & Park, C. (2018). Thermal adaptation and plasticity of the plant circadian clock. New Phytologist, 221(3), 1215–1229. [CrossRef]

- González-García, M. P., Conesa, C. M., Lozano-Enguita, A., Baca-González, V., Simancas, B., Navarro-Neila, S., Sánchez-Bermúdez, M., Salas-González, I., Caro, E., Castrillo, G., & Del Pozo, J. C. (2022). Temperature changes in the root ecosystem affect plant functionality. Plant Communications, 4(3), 100514. [CrossRef]

- Guo, F., Wang, R., Chen, M., & Crawford, N. M. (2001). The Arabidopsis Dual-Affinity Nitrate Transporter Gene AtNRT1.1 (CHL1) Is Activated and Functions in Nascent Organ Development during Vegetative and Reproductive Growth. The Plant Cell, 13(8), 1761–1778. [CrossRef]

- Hammes, U. Z., Murphy, A. S., & Schwechheimer, C. (2021). Auxin Transporters—A biochemical view. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, 14(2), a039875. [CrossRef]

- Hanzawa, T., Shibasaki, K., Numata, T., Kawamura, Y., Gaude, T., & Rahman, A. (2013). Cellular Auxin Homeostasis under High Temperature Is Regulated through a SORTING NEXIN1–Dependent Endosomal Trafficking Pathway. The Plant Cell, 25(9), 3424–3433. [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, K., Nakamura, S., Fukunaga, S., Nishimura, T., Jenness, M. K., Murphy, A. S., Motose, H., Nozaki, H., Furutani, M., & Aoyama, T. (2014). Auxin transport sites are visualized in planta using fluorescent auxin analogs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(31), 11557–11562. [CrossRef]

- Henrichs, S., Wang, B., Fukao, Y., Zhu, J., Charrier, L., Bailly, A., Oehring, S. C., Linnert, M., Weiwad, M., Endler, A., Nanni, P., Pollmann, S., Mancuso, S., Schulz, A., & Geisler, M. (2012). Regulation of ABCB1/PGP1-catalysed auxin transport by linker phosphorylation. The EMBO Journal, 31(13), 2965–2980. [CrossRef]

- Hong, J. H., Savina, M., Du, J., Devendran, A., Ramakanth, K. K., Tian, X., Sim, W. S., Mironova, V. V., & Xu, J. (2017). A Sacrifice-for-Survival Mechanism Protects Root Stem Cell Niche from Chilling Stress. Cell, 170(1), 102–113.e14. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C. H., & Hsu, Y. T. (2019). Biochemical responses of rice roots to cold stress. Botanical Studies, 60(1), 14. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L., Liao, Y., Lin, W., Lin, S., Liu, T., Lee, C., & Pan, R. (2019). Potassium stimulation of IAA transport mediated by the arabidopsis importer AUX1 investigated in a heterologous yeast system. The Journal of Membrane Biology, 252, 183–194. [CrossRef]

- Jásik, J., Boggetti, B., Baluška, F., Volkmann, D., Gensch, T., Rutten, T., Altmann, T., & Schmelzer, E. (2013). PIN2 turnover in Arabidopsis root epidermal cells explored by the photoconvertible protein Dendra2. PLoS ONE, 8(4), e61403. [CrossRef]

- Jones, A. R., Kramer, E. M., Knox, K., Swarup, R., Bennett, M. J., Lazarus, C. M., Leyser, H. M. O., & Grierson, C. S. (2008). Auxin transport through non-hair cells sustains root-hair development. Nature Cell Biology, 11(1), 78–84. [CrossRef]

- Karlova, R., Boer, D., Hayes, S., & Testerink, C. (2021). Root plasticity under abiotic stress. PLANT PHYSIOLOGY, 187(3), 1057–1070. [CrossRef]

- Ke, M., Ma, Z., Wang, D., Sun, Y., Wen, C., Huang, D., Chen, Z., Yang, L., Tan, S., Li, R., Friml, J., Miao, Y., & Chen, X. (2020). Salicylic acid regulates PIN2 auxin transporter hyperclustering and root gravitropic growth via Remorin--dependent lipid nanodomain organisation in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytologist, 229(2), 963–978. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., Henrichs, S., Bailly, A., Vincenzetti, V., Sovero, V., Mancuso, S., Pollmann, S., Kim, D., Geisler, M., & Nam, H. (2010). Identification of an ABCB/P-glycoprotein-specific inhibitor of AUxin transport by chemical genomics. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 285(30), 23309–23317. [CrossRef]

- Kitakura, S., Vanneste, S., Robert, S., Löfke, C., Teichmann, T., Tanaka, H., & Friml, J. (2011). Clathrin mediates endocytosis and polar distribution of PIN Auxin transporters inArabidopsis. The Plant Cell, 23(5), 1920–1931. [CrossRef]

- Kleine-Vehn, J., Dhonukshe, P., Swarup, R., Bennett, M., & Friml, J. (2006). Subcellular Trafficking of the Arabidopsis Auxin Influx Carrier AUX1 Uses a Novel Pathway Distinct from PIN1. The Plant Cell, 18(11), 3171–3181. [CrossRef]

- Kleine-Vehn, J., Łangowski, Ł., Wiśniewska, J., Dhonukshe, P., Brewer, P. B., & Friml, J. (2008). Cellular and molecular requirements for polar PIN targeting and transcytosis in plants. Molecular Plant, 1(6), 1056–1066. [CrossRef]

- Koevoets, I. T., Venema, J. H., Elzenga, J. T. M., & Testerink, C. (2016). Roots Withstanding their Environment: Exploiting Root System Architecture Responses to Abiotic Stress to Improve Crop Tolerance. Frontiers in Plant Science, 07. [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy, A., & Rathinasabapathi, B. (2013). Auxin and its transport play a role in plant tolerance to arsenite--induced oxidative stress in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell & Environment, 36(10), 1838–1849. [CrossRef]

- Krouk, G., Lacombe, B., Bielach, A., Perrine-Walker, F., Malinska, K., Mounier, E., Hoyerova, K., Tillard, P., Leon, S., Ljung, K., Zazimalova, E., Benkova, E., Nacry, P., & Gojon, A. (2010). Nitrate-Regulated Auxin transport by NRT1.1 defines a mechanism for nutrient sensing in plants. Developmental Cell, 18(6), 927–937. [CrossRef]

- Kubeš, M., Yang, H., Richter, G. L., Cheng, Y., Młodzińska, E., Wang, X., Blakeslee, J. J., Carraro, N., Petrášek, J., Zažímalová, E., Hoyerová, K., Peer, W. A., & Murphy, A. S. (2011). The Arabidopsis concentration--dependent influx/efflux transporter ABCB4 regulates cellular auxin levels in the root epidermis. The Plant Journal, 69(4), 640–654. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N., Caldwell, C., & Iyer-Pascuzzi, A. S. (2023). The NIN-LIKE PROTEIN 7 transcription factor modulates auxin pathways to regulate root cap development in Arabidopsis. Journal of Experimental Botany, 74(10), 3047–3059. [CrossRef]

- Laxmi, A., Pan, J., Morsy, M., & Chen, R. (2008). Light Plays an Essential Role in Intracellular Distribution of Auxin Efflux Carrier PIN2 in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS ONE, 3(1), e1510. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H., Ganguly, A., Lee, R. D., Park, M., & Cho, H. (2020). Intracellularly localized PIN-FORMED8 promotes lateral root emergence in arabidopsis. Frontiers in Plant Science, 10. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S., Showalter, J., Zhang, L., Cassin-Ross, G., Rouached, H., & Busch, W. (2024). Nutrient levels control root growth responses to high ambient temperature in plants. Nature Communications, 15(1), 4689. [CrossRef]

- Lehman, T. A., & Sanguinet, K. A. (2019). Auxin and Cell Wall Crosstalk as Revealed by the Arabidopsis thaliana Cellulose Synthase Mutant Radially Swollen 1. Plant and Cell Physiology, 60(7), 1487–1503. [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Von Wangenheim, D., Zhang, X., Tan, S., Darwish--Miranda, N., Naramoto, S., Wabnik, K., De Rycke, R., Kaufmann, W. A., Gütl, D., Tejos, R., Grones, P., Ke, M., Chen, X., Dettmer, J., & Friml, J. (2020). Cellular requirements for PIN polar cargo clustering in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytologist, 229(1), 351–369. [CrossRef]

- Löfke, C., Scheuring, D., Dünser, K., Schöller, M., Luschnig, C., & Kleine-Vehn, J. (2015). Tricho- and atrichoblast cell files show distinct PIN2 auxin efflux carrier exploitations and are jointly required for defined auxin-dependent root organ growth. Journal of Experimental Botany, 66(16), 5103–5112. [CrossRef]

- Marhava, P. (2021). Recent developments in the understanding of PIN polarity. New Phytologist, 233(2), 624–630. [CrossRef]

- Mellor, N. L., Voß, U., Ware, A., Janes, G., Barrack, D., Bishopp, A., Bennett, M. J., Geisler, M., Wells, D. M., & Band, L. R. (2022). Systems approaches reveal that ABCB and PIN proteins mediate co-dependent auxin efflux. The Plant Cell, 34(6), 2309–2327. [CrossRef]

- Men, S., Boutté, Y., Ikeda, Y., Li, X., Palme, K., Stierhof, Y., Hartmann, M., Moritz, T., & Grebe, M. (2008). Sterol-dependent endocytosis mediates post-cytokinetic acquisition of PIN2 auxin efflux carrier polarity. Nature Cell Biology, 10(2), 237–244. [CrossRef]

- Michniewicz, M., Ho, C., Enders, T. A., Floro, E., Damodaran, S., Gunther, L. K., Powers, S. K., Frick, E. M., Topp, C. N., Frommer, W. B., & Strader, L. C. (2019). TRANSPORTER OF IBA1 links Auxin and cytokinin to influence root architecture. Developmental Cell, 50(5), 599–609.e4. [CrossRef]

- Noureddine, J., Mu, B., Hamidzada, H., Mok, W. L., Bonea, D., Nambara, E., & Zhao, R. (2024). Knockout of endoplasmic reticulum--localized molecular chaperone HSP90.7 impairs seedling development and cellular auxin homeostasis in Arabidopsis. The Plant Journal, 119(1), 218–236. [CrossRef]

- Omelyanchuk, N., Kovrizhnykh, V., Oshchepkova, E., Pasternak, T., Palme, K., & Mironova, V. (2016). A detailed expression map of the PIN1 auxin transporter in Arabidopsis thaliana root. BMC Plant Biology, 16(S1), 5. [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, J. M., Song, L., Kuběnová, L., Ovečka, M., Gabarain, V. B., Peralta, J. M., Lehuedé, T. U., Ibeas, M. A., Ricardi, M. M., Zhu, S., Shen, Y., Schepetilnikov, M., Ryabova, L. A., Alvarez, J. M., Gutierrez, R. A., Grossmann, G., Šamaj, J., Yu, F., & Estevez, J. M. (2023). Cell surface receptor kinase FERONIA linked to nutrient sensor TORC signaling controls root hair growth at low temperature linked to low nitrate in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytologist, 238(1), 169–185. [CrossRef]

- Parveen, S., & Rahman, A. (2021). Actin isovariant ACT7 modulates root thermomorphogenesis by altering intracellular auxin homeostasis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(14), 7749. [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y., Ji, K., Mao, Y., Wang, Y., Korbei, B., Luschnig, C., Shen, J., Benková, E., Friml, J., & Tan, S. (2024). Polarly localized Bro1 domain proteins regulate PIN-FORMED abundance and root gravitropic growth in Arabidopsis. Communications Biology, 7(1), 1085. [CrossRef]

- Pernisova, M., Prat, T., Grones, P., Harustiakova, D., Matonohova, M., Spichal, L., Nodzynski, T., Friml, J., & Hejatko, J. (2016). Cytokinins influence root gravitropism via differential regulation of auxin transporter expression and localization in Arabidopsis. New Phytologist, 212(2), 497–509. [CrossRef]

- Planas-Riverola, A., Gupta, A., Betegón-Putze, I., Bosch, N., Ibañes, M., & Caño-Delgado, A. I. (2019). Brassinosteroid signaling in plant development and adaptation to stress. Development, 146(5), dev151894. [CrossRef]

- Polley, L. D., & Hopkins, J. W. (1979). Rubidium (Potassium) Uptake by Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology, 64(3), 374–378. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4265909.

- Prerostova, S., Dobrev, P. I., Kramna, B., Gaudinova, A., Knirsch, V., Spichal, L., Zatloukal, M., & Vankova, R. (2020). Heat acclimation and inhibition of cytokinin degradation positively affect heat stress tolerance of arabidopsis. Frontiers in Plant Science, 11. [CrossRef]

- Ray, D. K., Mueller, N. D., West, P. C., & Foley, J. A. (2013). Yield trends are insufficient to double global crop production by 2050. PLoS ONE, 8(6), e66428. [CrossRef]

- Retzer, K., Akhmanova, M., Konstantinova, N., Malínská, K., Leitner, J., PetráŠEk, J., & Luschnig, C. (2019). Brassinosteroid signaling delimits root gravitropism via sorting of the Arabidopsis PIN2 auxin transporter. Nature Communications, 10(1), 5516. [CrossRef]

- Růžička, K., Strader, L. C., Bailly, A., Yang, H., Blakeslee, J., Łangowski, Ł., Nejedlá, E., Fujita, H., Itoh, H., Syōno, K., Hejátko, J., Gray, W. M., Martinoia, E., Geisler, M., Bartel, B., Murphy, A. S., & Friml, J. (2010). Arabidopsis PIS1 encodes the ABCG37 transporter of auxinic compounds including the auxin precursor indole-3-butyric acid. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(23), 10749–10753. [CrossRef]

- Sassi, M., Lu, Y., Zhang, Y., Wang, J., Dhonukshe, P., Blilou, I., Dai, M., Li, J., Gong, X., Jaillais, Y., Yu, X., Traas, J., Ruberti, I., Wang, H., Scheres, B., Vernoux, T., & Xu, J. (2012). COP1 mediates the coordination of root and shoot growth by light through modulation of PIN1- and PIN2-dependent auxin transport in Arabidopsis. Development, 139(18), 3402–3412. [CrossRef]

- Seifu, Y. W., Pukyšová, V., Rýdza, N., Bilanovičová, V., Zwiewka, M., Sedláček, M., & Nodzyński, T. (2024). Mapping the membrane orientation of auxin homeostasis regulators PIN5 and PIN8 in Arabidopsis thaliana root cells reveals their divergent topology. Plant Methods, 20(1), 84. [CrossRef]

- Shibasaki, K., Uemura, M., Tsurumi, S., & Rahman, A. (2009). Auxin response inArabidopsisUnder Cold Stress: Underlying Molecular Mechanisms. The Plant Cell, 21(12), 3823–3838. [CrossRef]

- Simon, S., Skůpa, P., Viaene, T., Zwiewka, M., Tejos, R., Klíma, P., Čarná, M., Rolčík, J., De Rycke, R., Moreno, I., Dobrev, P. I., Orellana, A., Zažímalová, E., & Friml, J. (2016). PIN6 auxin transporter at endoplasmic reticulum and plasma membrane mediates auxin homeostasis and organogenesis in Arabidopsis. New Phytologist, 211(1), 65–74. [CrossRef]

- Strader, L. C., & Bartel, B. (2009). TheArabidopsisPLEIOTROPIC DRUG RESISTANCE8/ABCG36 ATP binding cassette transporter modulates sensitivity to the Auxin precursor Indole-3-Butyric acid. The Plant Cell, 21(7), 1992–2007. [CrossRef]

- Sun, L., Feraru, E., Feraru, M. I., Waidmann, S., Wang, W., Passaia, G., Wang, Z., Wabnik, K., & Kleine-Vehn, J. (2020). PIN-LIKES Coordinate Brassinosteroid Signaling with Nuclear Auxin Input in Arabidopsis thaliana. Current Biology, 30(9), 1579–1588.e6. [CrossRef]

- Terasaka, K., Blakeslee, J. J., Titapiwatanakun, B., Peer, W. A., Bandyopadhyay, A., Makam, S. N., Lee, O. R., Richards, E. L., Murphy, A. S., Sato, F., & Yazaki, K. (2005). PGP4, an ATP Binding Cassette P-Glycoprotein, Catalyzes Auxin Transport in Arabidopsis thaliana Roots. The Plant Cell, 17(11), 2922–2939. [CrossRef]

-

The Bio-Analytic Resource for Plant Biology. (2007). https://bar.utoronto.ca/eplant/.

- Titapiwatanakun, B., Blakeslee, J. J., Bandyopadhyay, A., Yang, H., Mravec, J., Sauer, M., Cheng, Y., Adamec, J., Nagashima, A., Geisler, M., Sakai, T., Friml, J., Peer, W. A., & Murphy, A. S. (2008). ABCB19/PGP19 stabilises PIN1 in membrane microdomains in Arabidopsis. The Plant Journal, 57(1), 27–44. [CrossRef]

- Van Den Berg, T., Yalamanchili, K., De Gernier, H., Teixeira, J. S., Beeckman, T., Scheres, B., Willemsen, V., & Tusscher, K. T. (2021). A reflux-and-growth mechanism explains oscillatory patterning of lateral root branching sites. Developmental Cell, 56(15), 2176–2191.e10. [CrossRef]

- Vieten, A., Vanneste, S., WiśNiewska, J., Benkova, E., Benjamins, R., Beeckman, T., Luschnig, C., & Friml, J. (2005). Functional redundancy of PIN proteins is accompanied by auxin-dependent cross-regulation of PIN expression. Development, 132(20), 4521–4531. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B., Henrichs, S., & Geisler, M. (2012). The AGC kinase, PINOID, blocks interactive ABCB/PIN auxin transport. Plant Signaling & Behavior, 7(12), 1515–1517. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Yang, L., Tang, Y., Tang, R., Jing, Y., Zhang, C., Zhang, B., Li, X., Cui, Y., Zhang, C., Shi, J., Zhao, F., Lan, W., & Luan, S. (2017). Arabidopsis choline transporter-like 1 (CTL1) regulates secretory trafficking of auxin transporters to control seedling growth. PLoS Biology, 15(12), e2004310. [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, S., Takahashi, N., Kanno, Y., Suzuki, H., Aoi, Y., Takeda-Kamiya, N., Toyooka, K., Kasahara, H., Hayashi, K., Umeda, M., & Seo, M. (2020). The Arabidopsis NRT1/PTR FAMILY protein NPF7.3/NRT1.5 is an indole-3-butyric acid transporter involved in root gravitropism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(49), 31500–31509. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H., Richter, G. L., Wang, X., Młodzińska, E., Carraro, N., Ma, G., Jenness, M., Chao, D., Peer, W. A., & Murphy, A. S. (2012). Sterols and sphingolipids differentially function in trafficking of the Arabidopsis ABCB19 auxin transporter. The Plant Journal, 74(1), 37–47. [CrossRef]

- Ying, W., Wang, Y., Wei, H., Luo, Y., Ma, Q., Zhu, H., Janssens, H., Vukašinović, N., Kvasnica, M., Winne, J. M., Gao, Y., Tan, S., Friml, J., Liu, X., Russinova, E., & Sun, L. (2024). Structure and function of the Arabidopsis ABC transporter ABCB19 in brassinosteroid export. Science, 383(6689), eadj4591. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X., Xu, P., Yu, Y., & Xiong, Y. (2020). Glucose-TOR signaling regulates PIN2 stability to orchestrate auxin gradient and cell expansion in Arabidopsis root. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(51), 32223–32225. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C., Liu, B., Piao, S., Wang, X., Lobell, D. B., Huang, Y., Huang, M., Yao, Y., Bassu, S., Ciais, P., Durand, J., Elliott, J., Ewert, F., Janssens, I. A., Li, T., Lin, E., Liu, Q., Martre, P., Müller, C., . . . Asseng, S. (2017). Temperature increase reduces global yields of major crops in four independent estimates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(35), 9326–9331. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J., Bailly, A., Zwiewka, M., Sovero, V., Di Donato, M., Ge, P., Oehri, J., Aryal, B., Hao, P., Linnert, M., Burgardt, N. I., Lücke, C., Weiwad, M., Michel, M., Weiergräber, O. H., Pollmann, S., Azzarello, E., Mancuso, S., Ferro, N., . . . Geisler, M. (2016). TWISTED DWARF1 mediates the action of AUxin transport inhibitors on Actin cytoskeleton dynamics. The Plant Cell, 28(4), 930–948. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J., Zhang, K., Wang, W., Gong, W., Liu, W., Chen, H., Xu, H., & Lu, Y. (2014). Low temperature inhibits root growth by reducing auxin accumulation via ARR1/12. Plant and Cell Physiology, 56(4), 727–736. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).