Submitted:

21 October 2025

Posted:

22 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

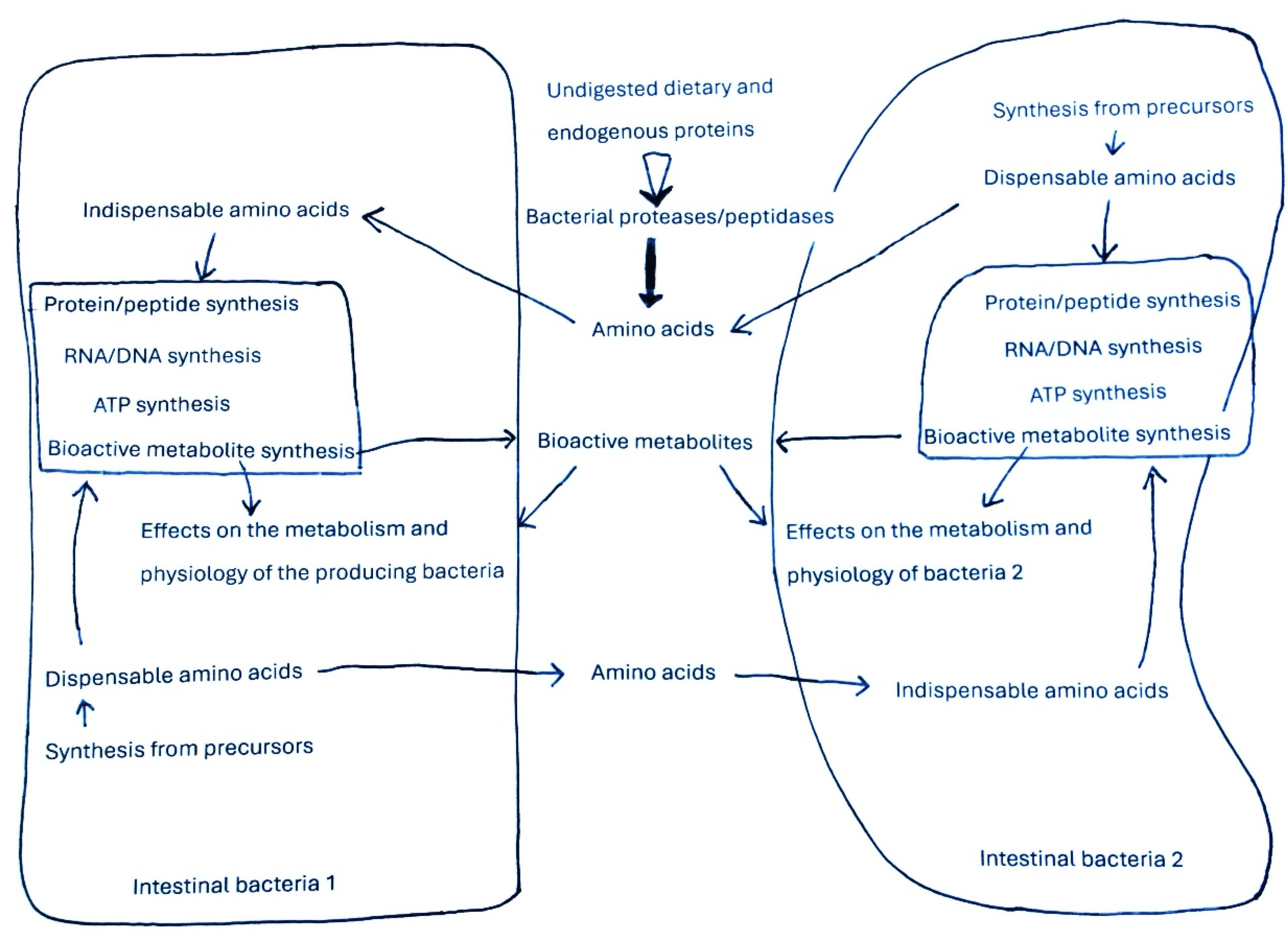

2. Origin of Proteins Available for the Large Intestine Microbiota

3. Metabolism of Proteins by the Large Intestine Bacteria

3.1. Degradation of Proteins by the Bacterial Proteases and Peptidases and Transport of Peptides and Amino Acids in Bacteria

3.2. The Indispensable Amino Acids for Intestinal Bacterial Species

3.3. Utilization of Amino Acid for Macromolecule Synthesis in Bacteria

3.4. Utilization of Amino Acids for ATP Synthesis in Bacteria

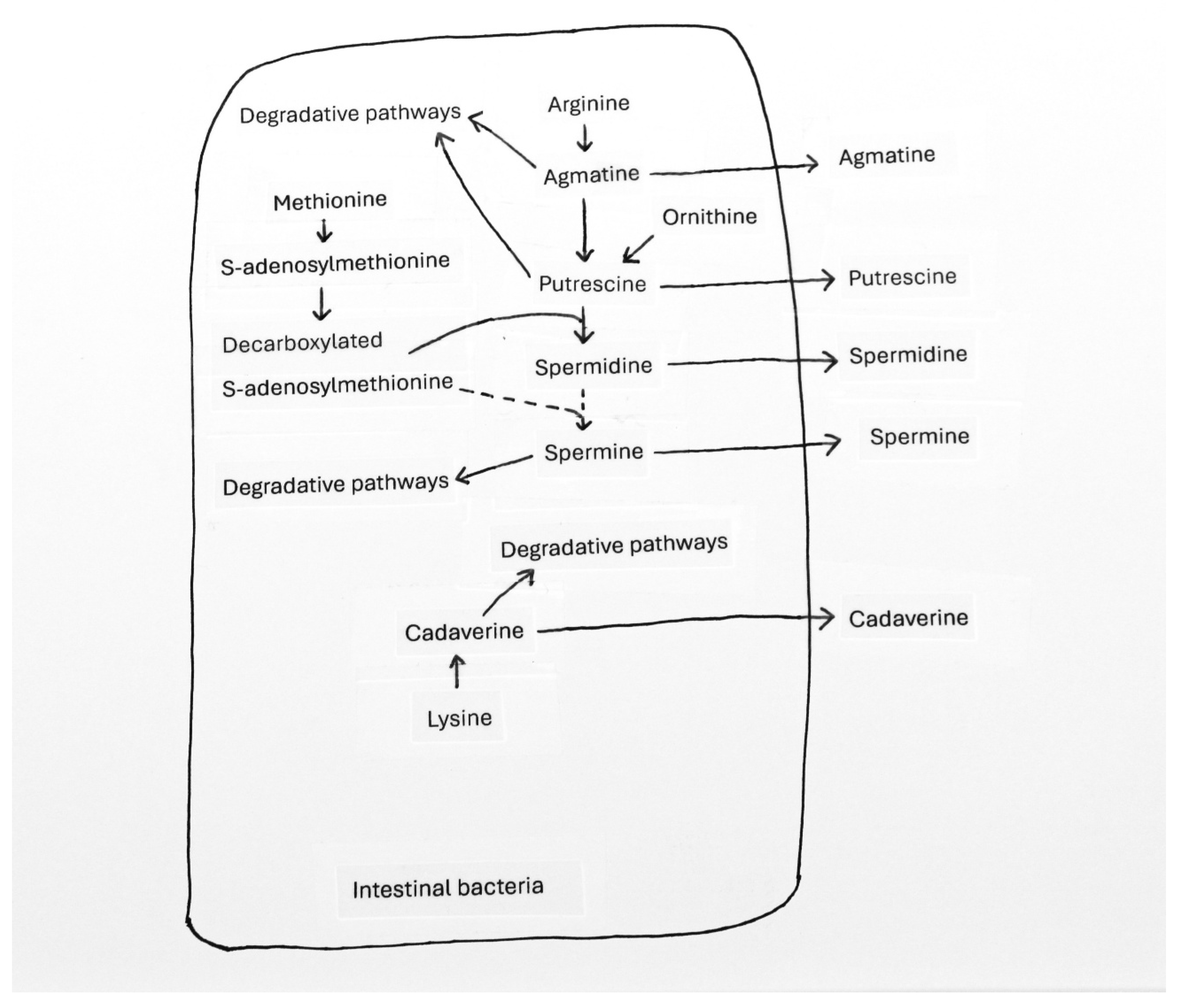

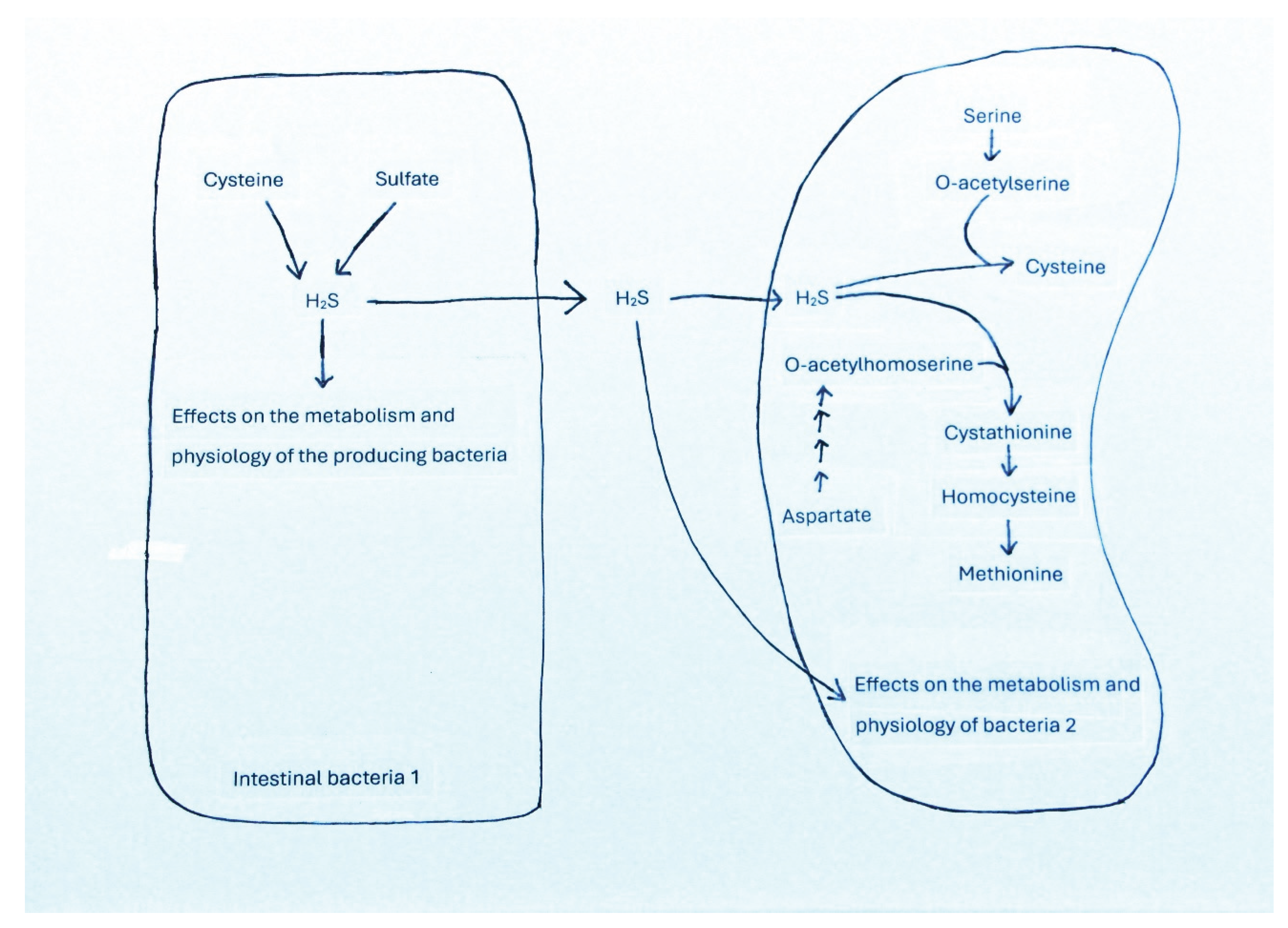

3.5. Utilization of Amino Acids for the Synthesis of Bioactive Metabolites in Bacteria and Effects of These Compounds on Bacterial Growth and Physiology

4. Conclusion and Perspectives

Funding

Informed Consent statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Blachier, F. Metabolism of Alimentary Compounds by the intestinal microbiota and Health; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Schleifer, KH. Classification of bacteria and archaea: past, present and future. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2009, 32, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matijašić M, Meštrović T, Paljetak HČ, Perić M, Barešić A, Verbanac D. Gut microbiota beyond bacteria-mycobiome, virome, archaeome, and eukaryotic parasites in IBD. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigottier-Gois, L. Dysbiosis in inflammatory bowel diseases: the oxygen hypothesis. ISME J. 2013, 7, 1256–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carding SR, Davis N, Hoyles L. Review article: the human intestinal virome in health and disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 46, 800–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sausset R, Petit MA, Gaboriau-Routhiau V, De Paepe M. New insights into intestinal phages. Mucosal. Immunol. 2020, 13, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartor RB, Wu GD. Roles for Intestinal Bacteria, Viruses, and Fungi in Pathogenesis of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases and Therapeutic Approaches. Gastroenterology. 2017, 152, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess SL, Gilchrist CA, Lynn TC, Petri WA Jr. Parasitic Protozoa and Interactions with the Host Intestinal Microbiota. Infect. Immun. 2017, 85, e00101–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marteau P, Pochart P, Doré J, Béra-Maillet C, Bernalier A, Corthier G. Comparative study of bacterial groups within the human cecal and fecal microbiota. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 67, 4939–4942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephen AM, Cummings JH. The microbial contribution to human faecal mass. J. Med. Microbiol. 1980, 13, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen AM, Wiggins HS, Cummings JH. Effect of changing transit time on colonic microbial metabolism in man. Gut. 1987, 28, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharucha AE, Anderson B, Bouchoucha M. More movement with evaluating colonic transit in humans. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2019, 31, e13541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint HJ, Scott KP, Louis P, Duncan SH. The role of the gut microbiota in nutrition and health. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 9, 577–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter SE, Bäumler AJ. Why related bacterial species bloom simultaneously in the gut: principles underlying the ‘Like will to like’ concept. Cell. Microbiol. 2014, 16, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macfarlane GT, Cummings JH. The colonic flora, fermentation, and large bowel digestive function. In: Phillips SF, Pemberton JH, Shorter RG, editors. The large intestine: physiology, pathophysiology, and disease. Raven Press, New York, USA, 1991.

- Windey K, De Preter V, Verbeke K. Relevance of protein fermentation to gut health. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2012, 56, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpela, K. Diet, Microbiota, and Metabolic Health: Trade-Off Between Saccharolytic and Proteolytic Fermentation. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 9, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith EA, Macfarlane GT. Enumeration of human colonic bacteria producing phenolic and indolic compounds: effects of pH, carbohydrate availability and retention time on dissimilatory aromatic amino acid metabolism. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1996, 81, 288–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkett A, Muir J, Phillips J, Jones G, O’Dea K. Resistant starch lowers fecal concentrations of ammonia and phenols in humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1996, 63, 766–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geboes KP, De Hertogh G, De Preter V, Luypaerts A, Bammens B, Evenepoel P, Ghoos Y, Geboes K, Rutgeerts P, Verbeke K. The influence of inulin on the absorption of nitrogen and the production of metabolites of protein fermentation in the colon. Br. J. Nutr. 2006, 96, 1078–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummings JH, Hill MJ, Bone ES, Branch WJ, Jenkins DJ. The effect of meat protein and dietary fiber on colonic function and metabolism. II. Bacterial metabolites in feces and urine. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1979, 32, 2094–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macfarlane GT, Cummings JH, Macfarlane S, Gibson GR. Influence of retention time on degradation of pancreatic enzymes by human colonic bacteria grown in a 3-stage continuous culture system. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1989, 67, 520–527. [Google Scholar]

- Blachier, F. Amino acid metabolism for bacterial physiology. In: The evolutionary journey of amino acids. From the origin of life to human metabolism. Springer Nature, Cham, Switzerland, 2025.

- Bröer, S. Intestinal Amino Acid Transport and Metabolic Health. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2023, 43, 73–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaudichon C, Bos C, Morens C, Petzke KJ, Mariotti F, Everwand J, Benamouzig R, Daré S, Tomé D, Metges CC. Ileal losses of nitrogen and amino acids in humans and their importance to the assessment of amino acid requirements. Gastroenterology. 2002, 123, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blachier F, Andriamihaja M, Kong XF. Fate of undigested proteins in the pig large intestine: What impact on the colon epithelium? Anim. Nutr. 2021, 9, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baglieri A, Mahe S, Zidi S, Huneau JF, Thuillier F, Marteau P, Tome D. Gastro-jejunal digestion of soya-bean-milk protein in humans. Br. J. Nutr. 1994, 72, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos C, Juillet B, Fouillet H, Turlan L, Daré S, Luengo C, N’tounda R, Benamouzig R, Gausserès N, Tomé D, Gaudichon C. Postprandial metabolic utilization of wheat protein in humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 81, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao CK, Muir JG, Gibson PR. Review article: insights into colonic protein fermentation, its modulation and potential health implications. Aliment.Pharmacol. Ther. 2016, 43, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson JA, Sladen GE, Dawson AM. Protein absorption and ammonia production: the effects of dietary protein and removal of the colon. Br. J. Nutr. 1976, 35, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, P. The effect of varying sodium loads on the ileal excreta of human ileostomized subjects J. Clin. Invest. 1966, 45, 1710–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smiddy FG, Gregory SD, Smith IB, Goligher J. Faecal loss of fluid, electrolytes, and nitrogen in colitis before and after ileostomy. Lancet. 7114.

- Chacko A, Cummings JH. Nitrogen losses from the human small bowel: obligatory losses and the effect of physical form of food. Gut. 1988, 29, 809–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubuisson C, Lioret S, Touvier M, Dufour A, Calamassi-Tran G, Volatier JL, Lafay L. Trends in food and nutritional intakes of French adults from 1999 to 2007: results from the INCA surveys. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 103, 1035–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasiakos SM, Agarwal S, Lieberman HR, Fulgoni VL 3rd. Sources and Amounts of Animal, Dairy, and Plant Protein Intake of US Adults in 2007-2010. Nutrients. 2015, 7, 7058–7069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blachier, F. Amino acid metabolism in the large intestine and physiological consequences. In: The evolutionary journey of amino acids. From the origin of life to human metabolism. Springer Nature, Cham, Switzerland, 2025.

- Kaman WE, Hays JP, Endtz HP, Bikker FJ. Bacterial proteases: targets for diagnostics and therapy. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2014, 33, 1081–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portune K, Beaumont M, Davila AM, Tomé D, Blachier F, Sanz Y. Gut microbiota role in protein metabolism and health-related outcomes: the two side of the coin. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 57, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessione, E. Lactic acid bacteria contribution to gut microbiota complexity: lights and shadows. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2012, 2, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu M, Bayjanov JR, Renckens B, Nauta A, Siezen RJ. The proteolytic system of lactic acid bacteria revisited: a genomic comparison. BMC Genomics. 2010, 11, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Saier MH, Jr. Families of transmembrane transporters selective for amino acids and their derivatives. Microbiology (Reading). 2000, 146, 1775–1795. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka KJ, Song S, Mason K, Pinkett HW. Selective substrate uptake: The role of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) importers in pathogenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2018, 1860, 868–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosie AH, Poole PS. Bacterial ABC transporters of amino acids. Res. Microbiol. 2001, 152, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkovski A, Krämer R. Bacterial amino acid transport proteins: occurrence, functions, and significance for biotechnological applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2002, 58, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konings, WN. The cell membrane and the struggle for life of lactic acid bacteria. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2002, 82, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Dinges MM, Green A, Cramer SE, Larive CK, Lytle C. Absorptive transport of amino acids by the rat colon. Am. J. Physiol. 2020, 318, G189–G202. [Google Scholar]

- van der Wielen N, Moughan PJ, Mensink M. Amino acid absorption in the large intestine of humans and porcine models. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 1493–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuller, M. Determination of protein and amino acid digestibility in foods including implications of gut microbial amino acid synthesis. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108, S238–S246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darragh AJ, Cranwell PD, Moughan PJ. Absorption of lysine and methionine from the proximal colon of the piglet. Br. J. Nutr. 1994, 71, 739–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaafsma, G. The protein digestibility-corrected amino acid score. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 1865S–1867S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metges, CC. Contribution of microbial amino acids to amino acid homeostasis of the host. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 1857S–1864S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller MF, Reeds PJ. Nitrogen cycling in the gut. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 1998, 18, 385–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niiyama M, Deguchi E, Kagota K, Namioka S. Appearance of 15N-labeled intestinal microbial amino acids in the venous blood of the pig colon. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1979, 40, 716–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi T, Hatanaka T, Huang W, Prasad PD, Leibach FH, Ganapathy ME, Ganapathy V. Na+- and Cl--coupled active transport of carnitine by the amino acid transporter ATB(0,+) from mouse colon expressed in HRPE cells and Xenopus oocytes. J. Physiol. 2001, 532, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatanaka T, Huang W, Nakanishi T, Bridges CC, Smith SB, Prasad PD, Ganapathy ME, Ganapathy V. Transport of D-serine via the amino acid transporter ATB(0,+) expressed in the colon. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002, 291, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugawa S, Sunouchi Y, Ueda T, Takahashi E, Saishin Y, Shimada S. Characterization of a mouse colonic system B(0+) amino acid transporter related to amino acid absorption in colon. Am. J. Physiol. 2001, 281, G365–G370.

- Blachier F, Mariotti F, Huneau JF, Tomé D. Effects of amino acid-derived luminal metabolites on the colonic epithelium and physiopathological consequences. Amino Acids. 2007, 33, 547–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James PS, Smith MW. Methionine transport by pig colonic mucosa measured during early post-natal development. J. Physiol. 1976, 262, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sepúlveda FV, Smith MW. Different mechanisms for neutral amino acid uptake by new-born pig colon. J. Physiol. 1979, 286, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou Y, Yin Y, Wu G. Dietary essentiality of “nutritionally non-essential amino acids” for animals and humans. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood). 2015, 240, 997–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathai JK, Liu Y, Stein HH. Values for digestible indispensable amino acid scores (DIAAS) for some dairy and plant proteins may better describe protein quality than values calculated using the concept for protein digestibility-corrected amino acid scores (PDCAAS). Br. J. Nutr. 2017, 117, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Detzner J, Pohlentz G, Müthing J. Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli and a fresh view on Shiga toxin-binding glycosphingolipids of primary human kidney and colon epithelial cells and their toxin susceptibility. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang YG, Singhal M, Lin Z, Manzella C, Kumar A, Alrefai WA, Dudeja PK, Saksena S, Sun J, Gill RK. Infection with enteric pathogens Salmonella typhimurium and Citrobacter rodentium modulate TGF-beta/Smad signaling pathways in the intestine. Gut Microbes. 2018, 9, 326–337. [Google Scholar]

- Jones SE, Knight KL. Bacillus subtilis-mediated protection from Citrobacter rodentium-associated enteric disease requires espH and functional flagella. Infect. Immun. 2012, 80, 710–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha A, Mehdizadeh Gohari I, Li J, Navarro M, Uzal FA, McClane BA. The biology and pathogenicity of Clostridium perfringens type F: a common human enteropathogen with a new(ish) name. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2024, 88, e0014023.

- Shimizu T, Ohtani K, Hirakawa H, Ohshima K, Yamashita A, Shiba T, Ogasawara N, Hattori M, Kuhara S, Hayashi H. Complete genome sequence of Clostridium perfringens, an anaerobic flesh-eater. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2002, 99, 996–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denou E, Rezzonico E, Panoff JM, Arigoni F, Brüssow H. A Mesocosm of Lactobacillus johnsonii, Bifidobacterium longum, and Escherichia coli in the mouse gut. DNA Cell. Biol. 2009, 28, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pridmore RD, Berger B, Desiere F, Vilanova D, Barretto C, Pittet AC, Zwahlen MC, Rouvet M, Altermann E, Barrangou R, Mollet B, Mercenier A, Klaenhammer T, Arigoni F, Schell MA. The genome sequence of the probiotic intestinal bacterium Lactobacillus johnsonii NCC 533. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2004, 101, 2512–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young KT, Davis LM, Dirita VJ. Campylobacter jejuni: molecular biology and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2007, 5, 665–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan TJ, Goeser L, Naziripour A, Redinbo MR, Hansen JJ. Enterococcus faecalis gluconate phosphotransferase system accelerates experimental colitis and bacterial killing by macrophages. Infect. Immun. 2019, 87, e00080–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu XJ, Walker DH, Liu Y, Zhang L. Amino acid biosynthesis deficiency in bacteria associated with human and animal hosts. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2009, 9, 514–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes-Santos AC, de Oliveira RP, Moreira TG, Castro-Junior AB, Horta BC, Lemos L, de Almeida LA, Rezende RM, Cara DC, Oliveira SC, Azevedo VA, Miyoshi A, Faria AM. Hsp65-producing Lactococcus lactis prevents inflammatory intestinal disease in mice by IL-10- and TLR2-dependent pathways. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Bolotin A, Wincker P, Mauger S, Jaillon O, Malarme K, Weissenbach J, Ehrlich SD, Sorokin A. The complete genome sequence of the lactic acid bacterium Lactococcus lactis ssp. lactis IL1403. Genome Res. 2001, 11, 731–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godon JJ, Delorme C, Bardowski J, Chopin MC, Ehrlich SD, Renault P. Gene inactivation in Lactococcus lactis: branched-chain amino acid biosynthesis. J Bacteriol. 1993, 175, 4383–4390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsultan A, Walton G, Andrews SC, Clarke SR. Staphylococcus aureus FadB is a dehydrogenase that mediates cholate resistance and survival under human colonic conditions. Microbiology (Reading). 2023, 169, 001314.

- Kuroda M, Ohta T, Uchiyama I, Baba T, Yuzawa H, Kobayashi I, Cui L, Oguchi A, Aoki K, Nagai Y, Lian J, Ito T, Kanamori M, Matsumaru H, Maruyama A, Murakami H, Hosoyama A, Mizutani-Ui Y, Takahashi NK, Sawano T, Inoue R, Kaito C, Sekimizu K, Hirakawa H, Kuhara S, Goto S, Yabuzaki J, Kanehisa M, Yamashita A, Oshima K, Furuya K, Yoshino C, Shiba T, Hattori M, Ogasawara N, Hayashi H, Hiramatsu K. Whole genome sequencing of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet. 2001, 357, 1225–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njenga R, Boele J, Öztürk Y, Koch HG. Coping with stress: How bacteria fine-tune protein synthesis and protein transport. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299, 105163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tollerson R 2nd, Ibba M. Translational regulation of environmental adaptation in bacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 10434–10445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macek B, Forchhammer K, Hardouin J, Weber-Ban E, Grangeasse C, Mijakovic I. Protein post-translational modifications in bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 651–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu Y, Qing Y, Chen J, Liu C, Lu J, Wang Q, Zhen S, Zhou H, Huang L, Zhang R. Prevalence, risk factors, and molecular epidemiology of intestinal carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiol. Spectr. 2021, 9, e0134421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang J, Hoedt EC, Liu Q, Berendsen E, Teh JJ, Hamilton A, O’ Brien AW, Ching JYL, Wei H, Yang K, Xu Z, Wong SH, Mak JWY, Sung JJY, Morrison M, Yu J, Kamm MA, Ng SC. Elucidation of Proteus mirabilis as a key bacterium in Crohn’s disease inflammation. Gastroenterology. 2021, 160, 317–330.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlier D, Nguyen Le Minh P, Roovers M. Regulation of carbamoylphosphate synthesis in Escherichia coli: an amazing metabolite at the crossroad of arginine and pyrimidine biosynthesis. Amino Acids. 2018, 50, 1647–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiva LE, Zegarra V, Bange G, Ibba M. At the crossroad of nucleotide dynamics and protein synthesis in bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2023, 87, e0004422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliphant K, Allen-Vercoe E. Macronutrient metabolism by the human gut microbiome: major fermentation by-products and their impact on host health. Microbiome. 2019, 7, 91. [Google Scholar]

- Davila AM, Blachier F, Gotteland M, Andriamihaja M, Benetti PH, Sanz Y, Tomé D. Intestinal luminal nitrogen metabolism: role of the gut microbiota and consequences for the host. Pharmacol. Res. 2013, 68, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim J, Hetzel M, Boiangiu CD, Buckel W. Dehydration of (R)-2-hydroxyacyl-CoA to enoyl-CoA in the fermentation of alpha-amino acids by anaerobic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2004, 28, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckel, W. Energy conservation in fermentations of anaerobic bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 703525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macfarlane GT, Macfarlane S. Bacteria, colonic fermentation, and gastrointestinal health. J. AOAC Int. 2012, 95, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, HA. Amino acid degradation by anaerobic bacteria. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1981, 50, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessione A, Lamberti C, Pessione E. Proteomics as a tool for studying energy metabolism in lactic acid bacteria. Mol. Biosyst. 2010, 6, 1419–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández M, Zúñiga M. Amino acid catabolic pathways of lactic acid bacteria. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2006, 32, 155–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira CI, Matos D, San Romão MV, Crespo MT. Dual role for the tyrosine decarboxylation pathway in Enterococcus faecium E17: response to an acid challenge and generation of a proton motive force. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stickland, LH. Studies in the metabolism of the strict anaerobes (Genus Clostridium): The reduction of proline by Cl. sporogenes. Biochem. J. 1935, 29, 288–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall A, McGrath JW, Graham R, McMullan G. Food for thought-The link between Clostridioides difficile metabolism and pathogenesis. PLoS Pathog. 2023, 19, e1011034. [Google Scholar]

- Pruss KM, Enam F, Battaglioli E, DeFeo M, Diaz OR, Higginbottom SK, Fischer CR, Hryckowian AJ, Van Treuren W, Dodd D, Kashyap P, Sonnenburg JL. Oxidative ornithine metabolism supports non-inflammatory C. difficile colonization. Nat. Metab. 2022, 4, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavao A, Graham M, Arrieta-Ortiz ML, Immanuel SRC, Baliga NS, Bry L. Reconsidering the in vivo functions of Clostridial Stickland amino acid fermentations. Anaerobe. 2022, 76, 102600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonknechten N, Chaussonnerie S, Tricot S, Lajus A, Andreesen JR, Perchat N, Pelletier E, Gouyvenoux M, Barbe V, Salanoubat M, Le Paslier D, Weissenbach J, Cohen GN, Kreimeyer A. Clostridium sticklandii, a specialist in amino acid degradation:revisiting its metabolism through its genome sequence. BMC Genomics. 2010, 11, 555. [Google Scholar]

- Blachier, F. Amino acid-derived bacterial metabolites in the colorectal luminal fluid: effects on microbial communication, metabolism, physiology, and growth. Microorganisms. 2023, 11, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, AJ. Polyamines in eukaryotes, bacteria, and archaea. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 14896–14903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li B, Baniasadi HR, Liang J, Phillips MA, Michael AJ. New routes for spermine biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2025, 301, 108390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah P, Swiatlo E. A multifaceted role for polyamines in bacterial pathogens. Mol. Microbiol. 2008, 68, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida M, Kashiwagi K, Shigemasa A, Taniguchi S, Yamamoto K, Makinoshima H, Ishihama A, Igarashi K. A unifying model for the role of polyamines in bacterial cell growth, the polyamine modulon. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 46008–46013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay MK, Keembiyehetty CN, Chen W, Tabor H. Polyamines stimulate the level of the sigma38 subunit (RpoS) of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase, resulting in the induction of the glutamate decarboxylase-dependent acid response system via the gadE regulon. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 17809–17821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Igarashi K, Kashiwagi K. Effects of polyamines on protein synthesis and growth of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 18702–18709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Igarashi K, Kashiwagi K. Polyamine transport in bacteria and yeast. Biochem. J. 1999, 344, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driessen AJ, Smid EJ, Konings WN. Transport of diamines by Enterococcus faecalis is mediated by an agmatine-putrescine antiporter. J. Bacteriol. 1988, 170, 4522–4527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Large, PJ. Enzymes and pathways of polyamine breakdown in microorganisms. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 1992, 8, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chattopadhyay MK, Tabor CW, Tabor H. Polyamines are not required for aerobic growth of Escherichia coli: preparation of a strain with deletions in all of the genes for polyamine biosynthesis. J. Bacteriol. 2009, 191, 5549–5552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakada Y, Itoh Y. Identification of the putrescine biosynthetic genes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and characterization of agmatine deiminase and N-carbamoylputrescine amidohydrolase of the arginine decarboxylase pathway. Microbiology (Reading). 2003, 149, 707–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanfrey CC, Pearson BM, Hazeldine S, Lee J, Gaskin DJ, Woster PM, Phillips MA, Michael AJ. Alternative spermidine biosynthetic route is critical for growth of Campylobacter jejuni and is the dominant polyamine pathway in human gut microbiota. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 43301–43312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagneau CV, Garcie C, Bossuet-Greif N, Tronnet S, Brachmann AO, Piel J, Nougayrède JP, Martin P, Oswald E. The polyamine spermidine modulates the production of the bacterial genotoxin colibactin. mSphere. 2019, 4, e00414–19. [Google Scholar]

- Goforth JB, Walter NE, Karatan E. Effects of polyamines on Vibrio cholerae virulence properties. PLoS One. 2013, 8, e60765. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer J, Özkaya Ö, Kümmerli R. Bacterial siderophores in community and host interactions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamana K, Saito T, Okada M, Sakamoto A, Hosoya R. Covalently linked polyamines in the cell wall peptidoglycan of Selenomonas, Anaeromusa, Dendrosporobacter, Acidaminococcus and Anaerovibrio belonging to the Sporomusa subbranch. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 2002, 48, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samartzidou H, Mehrazin M, Xu Z, Benedik MJ, Delcour AH. Cadaverine inhibition of porin plays a role in cell survival at acidic pH. J. Bacteriol. 2003, 185, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka Y, Kimura B, Takahashi H, Watanabe T, Obata H, Kai A, Morozumi S, Fujii T. Lysine decarboxylase of Vibrio parahaemolyticus: kinetics of transcription and role in acid resistance. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2008, 104, 1283–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall-Stoodley L, Costerton JW, Stoodley P. Bacterial biofilms: from the natural environment to infectious diseases. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004, 2, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flemming HC, Wingender J. The biofilm matrix. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010, 8, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blachier F, Beaumont M, Andriamihaja M, Davila AM, Lan A, Grauso M, Armand L, Benamouzig R, Tomé D. Changes in the luminal environment of the colonic epithelial cells and physiopathological consequences. Am. J. Pathol. 2017, 187, 476–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probert HM, Gibson GR. Bacterial biofilms in the human gastrointestinal tract. Curr. Issues Intest. Microbiol. 2002, 3, 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Roy R, Tiwari M, Donelli G, Tiwari V. Strategies for combating bacterial biofilms: A focus on anti-biofilm agents and their mechanisms of action. Virulence. 2018, 9, 522–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solano C, Echeverz M, Lasa I. Biofilm dispersion and quorum sensing. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2014, 18, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee S, Bassler BL. Bacterial quorum sensing in complex and dynamically changing environments. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerji R, Kanojiya P, Saroj SD. Role of interspecies bacterial communication in the virulence of pathogenic bacteria. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 46, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrell M, Hanfrey CC, Murray EJ, Stanley-Wall NR, Michael AJ. Evolution and multiplicity of arginine decarboxylases in polyamine biosynthesis and essential role in Bacillus subtilis biofilm formation. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 39224–39238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice JA, Bridges AA, Bassler BL. Synergy between c-di-GMP and quorum-sensing signaling in Vibrio cholerae biofilm morphogenesis. J. Bacteriol. 2022, 204, e0024922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatan E, Duncan TR, Watnick PI. NspS, a predicted polyamine sensor, mediates activation of Vibrio cholerae biofilm formation by norspermidine. J. Bacteriol. 2005, 187, 7434–7443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee J, Sperandio V, Frantz DE, Longgood J, Camilli A, Phillips MA, Michael AJ. An alternative polyamine biosynthetic pathway is widespread in bacteria and essential for biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 9899–9907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobe RC, Bond WG, Wotanis CK, Zayner JP, Burriss MA, Fernandez N, Bruger EL, Waters CM, Neufeld HS, Karatan E. Spermine inhibits Vibrio cholerae biofilm formation through the NspS-MbaA polyamine signaling system. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 17025–17036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blachier F, Davila AM, Mimoun S, Benetti PH, Atanasiu C, Andriamihaja M, Benamouzig R, Bouillaud F, Tomé D. Luminal sulfide and large intestine mucosa: friend or foe? Amino Acids. 2010, 39, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton LL, Ritz NL, Fauque GD, Lin HC. Sulfur cycling and the intestinal microbiome. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2017, 62, 2241–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basic A, Blomqvist M, Dahlén G, Svensäter G. The proteins of Fusobacterium spp. involved in hydrogen sulfide production from L-cysteine. BMC Microbiol. 2017, 17, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linden, DR. Hydrogen sulfide signaling in the gastrointestinal tract. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2014, 20, 818–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Croix JA, Carbonero F, Nava GM, Russell M, Greenberg E, Gaskins HR. On the relationship between sialomucin and sulfomucin expression and hydrogenotrophic microbes in the human colonic mucosa. PLoS One. 2011, 6, e24447. [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva-Millan MJ, Leite G, Mathur R, Rezaie A, Fajardo CM, de Freitas Germano J, Morales W, Sanchez M, Rivera I, Parodi G, Weitsman S, Rashid M, Hosseini A, Brimberry D, Barlow GM, Pimentel M. Hydrogen Sulfide and Methane on Breath Test Correlate with Human Small Intestinal Hydrogen Sulfide Producers and Methanogens. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2025, in press.

- Gibson GR, Macfarlane GT, Cummings JH. Occurrence of sulphate-reducing bacteria in human faeces and the relationship of dissimilatory sulphate reduction to methanogenesis in the large gut. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1988, 65, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohge H, Furne JK, Springfield J, Sueda T, Madoff RD, Levitt MD. The effect of antibiotics and bismuth on fecal hydrogen sulfide and sulfate-reducing bacteria in the rat. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2003, 228, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowan FE, Docherty NG, Coffey JC, O’Connell PR. Sulphate-reducing bacteria and hydrogen sulphide in the aetiology of ulcerative colitis. Br. J. Surg. 2009, 96, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kushkevych I, Dordević D, Alberfkani MI, Gajdács M, Ostorházi E, Vítězová M, Rittmann SKR. NADH and NADPH peroxidases as antioxidant defense mechanisms in intestinal sulfate-reducing bacteria. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 13922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Florin T, Neale G, Gibson GR, Christl SU, Cummings JH. Metabolism of dietary sulphate: absorption and excretion in humans. Gut. 1991, 32, 766–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis S, Cochrane S. Alteration of sulfate and hydrogen metabolism in the human colon by changing intestinal transit rate. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 102, 624–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blachier F, Andriamihaja M, Larraufie P, Ahn E, Lan A, Kim E. Production of hydrogen sulfide by the intestinal microbiota and epithelial cells and consequences for the colonic and rectal mucosa. Am. J. Physiol. 2021, 320, G125–G135. [Google Scholar]

- Bouillaud F, Blachier F. Mitochondria and sulfide: a very old story of poisoning, feeding, and signaling? Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2011, 15, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen J, Mortensen PB. Hydrogen sulfide and colonic epithelial metabolism: implications for ulcerative colitis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2001, 46, 1722–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez F, Furne J, Springfield J, Levitt M. Production and elimination of sulfur-containing gases in the rat colon. Am. J. Physiol. 1998, 274, G727–G733. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen B, Fago A. Reactions of ferric hemoglobin and myoglobin with hydrogen sulfide under physiological conditions. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2018, 182, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriamihaja M, Lan A, Beaumont M, Grauso M, Gotteland M, Pastene E, Cires MJ, Carrasco-Pozo C, Tomé D, Blachier F. Proanthocyanidin-containing polyphenol extracts from fruits prevent the inhibitory effect of hydrogen sulfide on human colonocyte oxygen consumption. Amino Acids. 2018, 50, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oldham KEA, Prentice EJ, Summers EL, Hicks JL. Serine acetyltransferase from Neisseria gonorrhoeae; structural and biochemical basis of inhibition. Biochem. J. 2022, 479, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hicks JL, Mullholland CV. Cysteine biosynthesis in Neisseria species. Microbiology (Reading). 2018, 164, 1471–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao S, Zhao Z, Wang W, Liu X. Bifidobacterium longum: protection against inflammatory bowel disease. J. Immunol. Res. 2021, 2021, 8030297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schell MA, Karmirantzou M, Snel B, Vilanova D, Berger B, Pessi G, Zwahlen MC, Desiere F, Bork P, Delley M, Pridmore RD, Arigoni F. The genome sequence of Bifidobacterium longum reflects its adaptation to the human gastrointestinal tract. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2002, 99, 14422–14427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodionov DA, Vitreschak AG, Mironov AA, Gelfand MS. Comparative genomics of the methionine metabolism in Gram-positive bacteria: a variety of regulatory systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 3340–3353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferla MP, Patrick WM. Bacterial methionine biosynthesis. Microbiology (Reading). 2014, 160, 1571–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saini V, Chinta KC, Reddy VP, Glasgow JN, Stein A, Lamprecht DA, Rahman MA, Mackenzie JS, Truebody BE, Adamson JH, Kunota TTR, Bailey SM, Moellering DR, Lancaster JR Jr, Steyn AJC. Hydrogen sulfide stimulates Mycobacterium tuberculosis respiration, growth and pathogenesis. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borisov VB, Forte E. Impact of hydrogen sulfide on mitochondrial and bacterial bioenergetics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo AM, Teixeira M. Supramolecular organization of bacterial aerobic respiratory chains: From cells and back. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016, 1857, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forte E, Borisov VB, Falabella M, Colaço HG, Tinajero-Trejo M, Poole RK, Vicente JB, Sarti P, Giuffrè A. The terminal oxidase cytochrome bd promotes sulfide-resistant bacterial respiration and growth. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 23788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastasi MR, Caruso L, Giordano F, Mellini M, Rampioni G, Giuffrè A, Forte E. Cyanide insensitive oxidase confers hydrogen sulfide and nitric oxide tolerance to Pseudomonas aeruginosa aerobic respiration. Antioxidants (Basel). 2024, 13, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachenheimer AG, Bennett EO. The sensitivity of mixed population of bacteria to inhibitors. I. The mechanism by which Desulfovibrio desulfuricans protects Ps. aeruginosa from the toxicity of mercurials. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 1961, 27, 180–188. [Google Scholar]

- Stutzenberger FJ, Bennett EO. Sensitivity of mixed populations of Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli to mercurials. Appl. Microbiol. 1965, 13, 570–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatalin K, Shatalina E, Mironov A, Nudler E. H2S: a universal defense against antibiotics in bacteria. Science. 2011, 334, 986–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal VK, Bandyopadhyay P, Singh A. Hydrogen sulfide in physiology and pathogenesis of bacteria and viruses. IUBMB Life. 2018, 70, 393–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mironov A, Seregina T, Nagornykh M, Luhachack LG, Korolkova N, Lopes LE, Kotova V, Zavilgelsky G, Shakulov R, Shatalin K, Nudler E. Mechanism of H2S-mediated protection against oxidative stress in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2017, 114, 6022–6027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla P, Khodade VS, SharathChandra M, Chauhan P, Mishra S, Siddaramappa S, Pradeep BE, Singh A, Chakrapani H. “On demand” redox buffering by H2S contributes to antibiotic resistance revealed by a bacteria-specific H2S donor. Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 4967–4972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatalin K, Nuthanakanti A, Kaushik A, Shishov D, Peselis A, Shamovsky I, Pani B, Lechpammer M, Vasilyev N, Shatalina E, Rebatchouk D, Mironov A, Fedichev P, Serganov A, Nudler E. Inhibitors of bacterial H2S biogenesis targeting antibiotic resistance and tolerance. Science. 2021, 372, 1169–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng SY, Ong KX, Surendran ST, Sinha A, Lai JJH, Chen J, Liang J, Tay LKS, Cui L, Loo HL, Ho P, Han J, Moreira W. Hydrogen Sulfide Sensitizes Acinetobacter baumannii to Killing by Antibiotics. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacy A, Andrade-Oliveira V, McCulloch JA, Hild B, Oh JH, Perez-Chaparro PJ, Sim CK, Lim AI, Link VM, Enamorado M, Trinchieri G, Segre JA, Rehermann B, Belkaid Y. Infection trains the host for microbiota-enhanced resistance to pathogens. Cell. 2021, 184, 615–627.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta JP, Flannigan KL, Agbor TA, Beatty JK, Blackler RW, Workentine ML, Da Silva GJ, Wang R, Buret AG, Wallace JL. Hydrogen sulfide protects from colitis and restores intestinal microbiota biofilm and mucus production. Inflamm. Bowel. Dis. 2015, 21, 1006–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen YW, Camacho MI, Chen Y, Bhat AH, Chang C, Peluso EA, Wu C, Das A, Ton-That H. Genetic determinants of hydrogen sulfide biosynthesis in Fusobacterium nucleatum are required for bacterial fitness, antibiotic sensitivity, and virulence. mBio. 2022, 13, 0193622. [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Wang X, Gao Y, Li S, Hu Z, Huang Y, Fan B, Wang X, Liu M, Qiao C, Zhang W, Wang Y, Ji X. H2S scavenger as a broad-spectrum strategy to deplete bacteria-derived H2S for antibacterial sensitization. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudhamsu J, Crane BR. Bacterial nitric oxide synthases: what are they good for? Trends Microbiol. 2009, 17, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adak S, Aulak KS, Stuehr DJ. Direct evidence for nitric oxide production by a nitric-oxide synthase-like protein from Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 16167–16171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita H, Yoshikawa H, Sakata R, Nagata Y, Tanaka H. Synthesis of nitric oxide from the two equivalent guanidino nitrogens of L-arginine by Lactobacillus fermentum. J. Bacteriol. 1997, 179, 7812–7815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sellars MJ, Hall SJ, Kelly DJ. Growth of Campylobacter jejuni supported by respiration of fumarate, nitrate, nitrite, trimethylamine-N-oxide, or dimethyl sulfoxide requires oxygen. J. Bacteriol. 2002, 184, 4187–4196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weingarten RA, Grimes JL, Olson JW. Role of Campylobacter jejuni respiratory oxidases and reductases in host colonization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 1367–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestrini MC, Falcinelli S, Ciabatti I, Cutruzzolà F, Brunori M. Pseudomonas aeruginosa nitrite reductase (or cytochrome oxidase): an overview. Biochimie. 1994, 76, 641–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daims H, Lebedeva EV, Pjevac P, Han P, Herbold C, Albertsen M, Jehmlich N, Palatinszky M, Vierheilig J, Bulaev A, Kirkegaard RH, von Bergen M, Rattei T, Bendinger B, Nielsen PH, Wagner M. Complete nitrification by Nitrospira bacteria. Nature. 2015, 528, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng Y, Ke J, Song J, Li X, Kuang R, Wang H, Li S, Li Y. Correlation between daily physical activity and intestinal microbiota in perimenopausal women. Sports Med. Health Sci. 2024, 7, 230–236. [Google Scholar]

- Kastner J, Pfeffel F, Rajek A, Pezawas T, Hiesmayr M, Eichler HG. Nitric oxide concentration in the gas phase of the gastrointestinal tract in man. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 1997, 27, 992–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson AR, Payne EC, Younger N, Karlinsey JE, Thomas VC, Becker LA, Navarre WW, Castor ME, Libby SJ, Fang FC. Multiple targets of nitric oxide in the tricarboxylic acid cycle of Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium. Cell Host Microbe. 2011, 10, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern AM, Zhu J. An introduction to nitric oxide sensing and response in bacteria. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 87, 187–220. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao G, Guo YY, Yao S, Shi X, Lv L, Du YL. Nitric oxide as a source for bacterial triazole biosynthesis. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caranto, JD. The emergence of nitric oxide in the biosynthesis of bacterial natural products. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2019, 49, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choules MP, Wolf NM, Lee H, Anderson JR, Grzelak EM, Wang Y, Ma R, Gao W, McAlpine JB, Jin YY, Cheng J, Lee H, Suh JW, Duc NM, Paik S, Choe JH, Jo EK, Chang CL, Lee JS, Jaki BU, Pauli GF, Franzblau SG, Cho S. Rufomycin targets ClpC1 proteolysis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and M. abscessus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e02204–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anantharaman S, Guercio D, Mendoza AG, Withorn JM, Boon EM. Negative regulation of biofilm formation by nitric oxide sensing proteins. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2023, 51, 1447–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poh WH, Rice SA. Recent Developments in nitric oxide donors and delivery for antimicrobial and anti-biofilm applications. Molecules. 2022, 27, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueno T, Fischer JT, Boon EM. Nitric oxide enters quorum sensing via the H-NOX signaling pathway in Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keszthelyi D, Troost FJ, Masclee AA. Understanding the role of tryptophan and serotonin metabolism in gastrointestinal function. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2009, 21, 1239–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee JH, Wood TK, Lee J. Roles of indole as an interspecies and interkingdom signaling molecule. Trends Microbiol. 2015, 23, 707–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roager HM, Licht TR. Microbial tryptophan catabolites in health and disease. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rattanaphan P, Mittraparp-Arthorn P, Srinoun K, Vuddhakul V, Tansila N. Indole signaling decreases biofilm formation and related virulence of Listeria monocytogenes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2020, 367, fnaa116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee J, Attila C, Cirillo SL, Cirillo JD, Wood TK. Indole and 7-hydroxyindole diminish Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence. Microb. Biotechnol. 2009, 2, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikaido E, Giraud E, Baucheron S, Yamasaki S, Wiedemann A, Okamoto K, Takagi T, Yamaguchi A, Cloeckaert A, Nishino K. Effects of indole on drug resistance and virulence of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium revealed by genome-wide analyses. Gut Pathog. 2012, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh S, Go GW, Mylonakis E, Kim Y. The bacterial signalling molecule indole attenuates the virulence of the fungal pathogen Candida albicans. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2012, 113, 622–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talapko J, Juzbašić M, Matijević T, Pustijanac E, Bekić S, Kotris I, Škrlec I. Candida albicans-The virulence factors and clinical manifestations of infection. J. Fungi (Basel). 2021, 7, 79.

- Nowak A, Libudzisz Z. Influence of phenol, p-cresol and indole on growth and survival of intestinal lactic acid bacteria. Anaerobe. 2006, 12, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledala N, Malik M, Rezaul K, Paveglio S, Provatas A, Kiel A, Caimano M, Zhou Y, Lindgren J, Krasulova K, Illes P, Dvořák Z, Kortagere S, Kienesberger S, Cosic A, Pöltl L, Zechner EL, Ghosh S, Mani S, Radolf JD, Matson AP. Bacterial indole as a multifunctional regulator of Klebsiella oxytoca complex enterotoxicity. mBio. 2022, 13, e0375221. [Google Scholar]

- Högenauer C, Langner C, Beubler E, Lippe IT, Schicho R, Gorkiewicz G, Krause R, Gerstgrasser N, Krejs GJ, Hinterleitner TA. Klebsiella oxytoca as a causative organism of antibiotic-associated hemorrhagic colitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 355, 2418–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bone E, Tamm A, Hill M. The production of urinary phenols by gut bacteria and their possible role in the causation of large bowel cancer. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1976, 29, 1448–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito Y, Sato T, Nomoto K, Tsuji H. Identification of phenol- and p-cresol-producing intestinal bacteria by using media supplemented with tyrosine and its metabolites. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2018, 94, fiy125.

- Harrison MA, Kaur H, Wren BW, Dawson LF. Production of p-cresol by Decarboxylation of p-HPA by All Five Lineages of Clostridioides difficile Provides a Growth Advantage. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 757599. [Google Scholar]

- Passmore IJ, Letertre MPM, Preston MD, Bianconi I, Harrison MA, Nasher F, Kaur H, Hong HA, Baines SD, Cutting SM, Swann JR, Wren BW, Dawson LF. Para-cresol production by Clostridium difficile affects microbial diversity and membrane integrity of Gram-negative bacteria. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1007191. [Google Scholar]

- Abt MC, McKenney PT, Pamer EG. Clostridium difficile colitis: pathogenesis and host defence. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 609–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafiz S, Oakley CL. Clostridium difficile: isolation and characteristics. J. Med. Microbiol. 1976, 9, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson LF, Donahue EH, Cartman ST, Barton RH, Bundy J, McNerney R, Minton NP, Wren BW. The analysis of para-cresol production and tolerance in Clostridium difficile 027 and 012 strains. BMC Microbiol. 2011, 11, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen MT, Cox RP, Jensen BB. 3-Methylindole (skatole) and indole production by mixed populations of pig fecal bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995, 61, 3180–3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama MT, Carlson JR. Microbial metabolites of tryptophan in the intestinal tract with special reference to skatole. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1979, 32, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead TR, Price NP, Drake HL, Cotta MA. Catabolic pathway for the production of skatole and indoleacetic acid by the acetogen Clostridium drakei, Clostridium scatologenes, and swine manure. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 1950–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi SH, Kim Y, Oh S, Oh S, Chun T, Kim SH. Inhibitory effect of skatole (3-methylindole) on enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 ATCC 43894 biofilm formation mediated by elevated endogenous oxidative stress. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 58, 454–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morbach S, Krämer R. Structure and function of the betaine uptake system BetP of Corynebacterium glutamicum: strategies to sense osmotic and chill stress. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2005, 10, 143–153. [Google Scholar]

- Nau-Wagner G, Opper D, Rolbetzki A, Boch J, Kempf B, Hoffmann T, Bremer E. Genetic control of osmoadaptive glycine betaine synthesis in Bacillus subtilis through the choline-sensing and glycine betaine-responsive GbsR repressor. J. Bacteriol. 2012, 194, 2703–2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou H, Chen N, Shi M, Xian M, Song Y, Liu J. The metabolism and biotechnological application of betaine in microorganism. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 3865–3876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wargo, MJ. Homeostasis and catabolism of choline and glycine betaine: lessons from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 2112–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku JW, Gan YH. Modulation of bacterial virulence and fitness by host glutathione. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2019, 47, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masip L, Veeravalli K, Georgiou G. The many faces of glutathione in bacteria. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2006, 8, 753–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landete JM, De las Rivas B, Marcobal A, Muñoz R. Updated molecular knowledge about histamine biosynthesis by bacteria. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2008, 48, 697–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicks LMT. Gut bacteria and neurotransmitters. Microorganisms. 2022, 10, 1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molenaar D, Bosscher JS, ten Brink B, Driessen AJ, Konings WN. Generation of a proton motive force by histidine decarboxylation and electrogenic histidine/histamine antiport in Lactobacillus buchneri. J. Bacteriol. 1993, 175, 2864–2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trip H, Mulder NL, Lolkema JS. Improved acid stress survival of Lactococcus lactis expressing the histidine decarboxylation pathway of Streptococcus thermophilus CHCC1524. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 11195–11204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugent SG, Kumar D, Rampton DS, Evans DF. Intestinal luminal pH in inflammatory bowel disease: possible determinants and implications for therapy with aminosalicylates and other drugs. Gut. 2001, 48, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strandwitz, P. Neurotransmitter modulation by the gut microbiota. Brain Res. 2018, 1693, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claus H, Decker H. Bacterial tyrosinases. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2006, 29, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asano Y, Hiramoto T, Nishino R, Aiba Y, Kimura T, Yoshihara K, Koga Y, Sudo N. Critical role of gut microbiota in the production of biologically active, free catecholamines in the gut lumen of mice. Am. J. Physiol. 2012, 303, G1288–G1295. [Google Scholar]

- Belay T, Sonnenfeld G. Differential effects of catecholamines on in vitro growth of pathogenic bacteria. Life Sci. 2002, 71, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dichtl S, Demetz E, Haschka D, Tymoszuk P, Petzer V, Nairz M, Seifert M, Hoffmann A, Brigo N, Würzner R, Theurl I, Karlinsey JE, Fang FC, Weiss G. Dopamine is a siderophore-like iron chelator that promotes Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium virulence in mice. mBio. 2019, 10, e02624–18. [Google Scholar]

- Knecht LD, O’Connor G, Mittal R, Liu XZ, Daftarian P, Deo SK, Daunert S. Serotonin activates bacterial quorum sensing and enhances the virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the host. EBioMedicine. 2016, 9, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyanova, L. Stress hormone epinephrine (adrenaline) and norepinephrine (noradrenaline) effects on the anaerobic bacteria. Anaerobe. 2017, 44, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lustri BC, Sperandio V, Moreira CG. Bacterial chat: intestinal metabolites and signals in host-microbiota-pathogen interactions. Infect. Immun. 2017, 85, e00476–17. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell PM, Aviles H, Lyte M, Sonnenfeld G. Enhancement of in vitro growth of pathogenic bacteria by norepinephrine: importance of inoculum density and role of transferrin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 5097–5099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim J, Lee MH, Kim MS, Kim GH, Yoon SS. Probiotic properties and optimization of gamma-aminobutyric acid production by Lactiplantibacillus plantarum FBT215. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 32, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett E, Ross RP, O’Toole PW, Fitzgerald GF, Stanton C. gamma-aminobutyric acid production by culturable bacteria from the human intestine. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2012, 113, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura M, Nakajima I, Fujita Y, Kobayashi M, Kimoto H, Suzuki I, Aso H. Lactococcus lactis contains only one glutamate decarboxylase gene. Microbiology (Reading). 1999, 145, 1375–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otaru N, Ye K, Mujezinovic D, Berchtold L, Constancias F, Cornejo FA, Krzystek A, de Wouters T, Braegger C, Lacroix C, Pugin B. GABA Production by human intestinal Bacteroides spp.: prevalence, regulation, and role in acid stress tolerance. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 656895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feehily C, Karatzas KA. Role of glutamate metabolism in bacterial responses towards acid and other stresses. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2013, 114, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prieto MA, García JL. Identification of the 4-hydroxyphenylacetate transport gene of Escherichia coli W: construction of a highly sensitive cellular biosensor. FEBS Lett. 1997, 414, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- YujiaLiu, Shi C, Zhang G, Zhan H, Liu B, Li C, Wang L, Wang H, Wang J. Antimicrobial mechanism of 4-hydroxyphenylacetic acid on Listeria monocytogenes membrane and virulence. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 572, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai ZL, Wu G, Zhu WY. Amino acid metabolism in intestinal bacteria: links between gut ecology and host health. Front. Biosci (Landmark Ed). 2011, 16, 1768–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endo A, Nakamura S, Konishi K, Nakagawa J, Tochio T. Variations in prebiotic oligosaccharide fermentation by intestinal lactic acid bacteria. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 67, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liong MT, Shah NP. Production of organic acids from fermentation of mannitol, fructooligosaccharide and inulin by a cholesterol removing Lactobacillus acidophilus strain. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2005, 99, 783–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goocher CR, Woodside EE, Kocholaty W. The influence of 2,4-dinitrophenol on the oxidation of acetate and succinate by Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1954, 67, 593–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemma E, Hägerhäll C, Geisler V, Brandt U, von Jagow G, Kröger A. Reactivity of the Bacillus subtilis succinate dehydrogenase complex with quinones. Biochim. Biophys Acta. 1991, 1059, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adolph C, McNeil MB, Cook GM. Impaired succinate oxidation prevents growth and influences drug susceptibility in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. mBio. 2022, 13, e0167222. [Google Scholar]

- Hartman T, Weinrick B, Vilchèze C, Berney M, Tufariello J, Cook GM, Jacobs WR Jr. Succinate dehydrogenase is the regulator of respiration in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004510. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreyra JA, Wu KJ, Hryckowian AJ, Bouley DM, Weimer BC, Sonnenburg JL. Gut microbiota-produced succinate promotes C. difficile infection after antibiotic treatment or motility disturbance. Cell Host Microbe. 2014, 16, 770–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auria E, Deschamps J, Briandet R, Dupuy B. Extracellular succinate induces spatially organized biofilm formation in Clostridioides difficile. Biofilm. 2023, 5, 100125. [Google Scholar]

- Hagihara M, Ariyoshi T, Kuroki Y, Eguchi S, Higashi S, Mori T, Nonogaki T, Iwasaki K, Yamashita M, Asai N, Koizumi Y, Oka K, Takahashi M, Yamagishi Y, Mikamo H. Clostridium butyricum enhances colonization resistance against Clostridioides difficile by metabolic and immune modulation. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 15007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaulov Y, Shimokawa C, Trebicz-Geffen M, Nagaraja S, Methling K, Lalk M, Weiss-Cerem L, Lamm AT, Hisaeda H, Ankri S. Escherichia coli mediated resistance of Entamoeba histolytica to oxidative stress is triggered by oxaloacetate. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1007295. [Google Scholar]

- Guillén, N. Pathogenicity and virulence of Entamoeba histolytica, the agent of amoebiasis. Virulence. 2023, 14, 2158656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassem II, Candelero-Rueda RA, Esseili KA, Rajashekara G. Formate simultaneously reduces oxidase activity and enhances respiration in Campylobacter jejuni. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 40117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voskuhl L, Brusilova D, Brauer VS, Meckenstock RU. Inhibition of sulfate-reducing bacteria with formate. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2022, 98, fiac003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koestler BJ, Fisher CR, Payne SM. Formate promotes Shigella intercellular spread and virulence gene expression. mBio. 2018, 9, e01777–18. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, SQ. Practical implications of lactate and pyruvate metabolism by lactic acid bacteria in food and beverage fermentations. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2003, 83, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheridan PO, Louis P, Tsompanidou E, Shaw S, Harmsen HJ, Duncan SH, Flint HJ, Walker AW. Distribution, organization and expression of genes concerned with anaerobic lactate utilization in human intestinal bacteria. Microb. Genom. 2022, 8, 000739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weghoff MC, Bertsch J, Müller V. A novel mode of lactate metabolism in strictly anaerobic bacteria. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 17, 670–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thauer, RK. Citric-acid cycle, 50 years on. Modifications and an alternative pathway in anaerobic bacteria. Eur. J. Biochem. 1988, 176, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampieri M, Hörl M, Hotz F, Müller NF, Sauer U. Regulatory mechanisms underlying coordination of amino acid and glucose catabolism in Escherichia coli. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarantinopoulos P, Makras L, Vaningelgem F, Kalantzopoulos G, De Vuyst L, Tsakalidou E. Growth and energy generation by Enterococcus faecium FAIR-E 198 during citrate metabolism. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2003, 84, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Elías EJ, McKinney JD. Carbon metabolism of intracellular bacteria. Cell Microbiol. 2006, 8, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underhill SAM, Cabeen MT. Redundancy in Citrate and cis-Aconitate Transport in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 2022, 204, e0028422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortera P, Pudlik A, Magni C, Alarcón S, Lolkema JS. Ca2+-citrate uptake and metabolism in Lactobacillus casei ATCC 334. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 4603–4612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfenninger-Li XD, Dimroth P. NADH formation by Na(+)-coupled reversed electron transfer in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 1992, 6, 1943–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos A, Poolman B, Santos H, Lolkema JS, Konings WN. Uniport of anionic citrate and proton consumption in citrate metabolism generates a proton motive force in Leuconostoc oenos. J. Bacteriol. 1994, 176, 4899–4905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pudlik AM, Lolkema JS. Citrate uptake in exchange with intermediates in the citrate metabolic pathway in Lactococcus lactis IL1403. J. Bacteriol. 2011, 193, 706–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon JR, Marolda CL, Heinrichs DE. TCA cycle activity in Staphylococcus aureus is essential for iron-regulated synthesis of staphyloferrin A, but not staphyloferrin B: the benefit of a second citrate synthase. Mol. Microbiol. 2014, 92, 824–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaumont M, Portune KJ, Steuer N, Lan A, Cerrudo V, Audebert M, Dumont F, Mancano G, Khodorova N, Andriamihaja M, Airinei G, Tomé D, Benamouzig R, Davila AM, Claus SP, Sanz Y, Blachier F. Quantity and source of dietary protein influence metabolite production by gut microbiota and rectal mucosa gene expression: a randomized, parallel, double-blind trial in overweight humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 106, 1005–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).