1. Introduction

Wavelet neural networks (WNNs) are an appealing family of models because they combine multiscale, well-localized representations with the universal approximation capability of neural structures. Recent work ranges from graph-based wavelet neural networks (GWNN) to "decompose-then-learn" pipelines to deep models enhanced with wavelet transforms, demonstrating that wavelet structure can improve stability, efficiency, and interpretability across applications in vision, signal processing, and energy systems [

1,

2,

3,

4]. The optimization theory governing the training dynamics of WNNs is significantly less studied than that of other architectures, especially when gradient descent (GD) with L₂ regularization (weight decay) is employed. This gap between theoretical knowledge and real progress is the main topic of this research.Wavelet advantages in practice manifest along two axes: (a) multiscale localization, which captures local phenomena at various frequencies without losing broader context; and (b) computational efficiency when employing learnable or fixed wavelet filters, which reduces sensitivity to small perturbations in the data and speeds up training.

In practice, wavelet benefits show up along two axes: (a) multiscale localization, which records local phenomena at different frequencies without losing broader context; and (b) computational efficiency when using fixed or learnable wavelet filters, which speeds up training and decreases sensitivity to slight perturbations in the data. Baharlouei et al. categorize retinal OCT anomalies using wavelet scattering, which has a lower processing cost and more robustness than more complex deep alternatives. Graph wavelet neural networks efficiently capture spatiotemporal dependencies, while other recent studies integrate wavelet decompositions into deep models for complex time-series, such as wind power [

3,

4]. These empirical data pose a fundamental question: When and why does GD with L₂ converge steadily and rapidly for WNNs?

L₂ regularization is one of the most used tools from an optimization perspective. L₂ has an implicit bias in deep networks in addition to its traditional use in conditioning and in imparting effective curvature (for example, for a linear head on fixed features). Weight decay encourages low-rank tendencies and chooses smaller-norm solutions in parameter or function space, as demonstrated by recent works (2024–2025). These phenomena are closely related to convergence speed and stability [

7]. Two regimes make the interaction of L₂ with GD particularly noticeable: (1) the fixed-feature regime, in which only a linear head is trained and the wavelet dictionary is frozen; this results in ridge regression as the objective, which is substantially convex and hence admits global linear convergence rates. (2) the fully trainable regime, in which wavelet parameters (translations/dilations) and weights are tuned; in this case, generic tools to demonstrate linear rates within appropriate landscape regions are provided by conditions such as the Polyak–Łojasiewicz (PL) inequality [

5,

6].

Another theoretical viewpoint is provided by the neural tangent kernel (NTK). Between 2022 and 2024, NTK theory became a solid foundation for understanding over-parameterized training dynamics. In this regime, a nonlinear network behaves linearly in function space around initialization with respect to an effective kernel, and GD with L₂ becomes equivalent to GD in the corresponding RKHS. Surveys and practical evaluations suggest that this perspective accounts for both the minimum-norm bias and convergence (via the kernel spectrum): L₂-regularized GD selects the minimum-RKHS-norm solution among all interpolants during interpolation [

8,

9,

10]. Making this image unique to WNNs is our contribution: What is the appearance of the WNN-specific NTK with realistic initiation and limited dilation/shift ranges? What effects do wavelet selections have on the spectral constant governing the rate?

In-depth analyses of wavelet–deep integration reveal that training-dynamics guarantees, especially with L₂, remain absent despite steady progress, and most contributions concentrate on architectural design or empirical advantages. Even with forward-looking hybrids like Wav-KAN (2024) [

1,

11], sharp statements concerning rates, step-size/regularization requirements, and stability bounds are still uncommon when compared to linear models or neural networks under restrictive assumptions. This disparity has practical implications: without principled direction, practitioners are forced to rely on costly trial-and-error to calculate the learning rate (

) and regularization (

), and it becomes more challenging to ascertain why training is effective or ineffective.

This paper's contributions. For gradient descent on WNNs in three regimes with L₂ regularization, we provide a unified analysis of convergence:

- (a)

Over a fixed wavelet dictionary, linear-head. With explicit rates controlled by the eigenvalues of , we demonstrate global linear convergence to the unique ridge minimizer. This results in useful guidelines for considering () as a conditioning lever instead of just an anti-overfitting knob.

- (b)

WNNs that are fully trainable (nonconvex). GD converges to stationary points and enjoys linear rates within regions meeting PL under the conditions of natural smoothness and boundedness for wavelets (within a restricted dilation/shift domain). We give implementable step-size limitations and demonstrate how L₂ dampens flat directions to widen PL basins.

- (c)

regime that is over-parameterized (NTK). We extract rate constants related to the kernel spectrum induced by the wavelet dictionary and demonstrate that L₂ directs GD toward the minimum-RKHS-norm interpolant associated with the WNN-specific NTK.

Influence on practice and methodology. The following is a training recipe derived from our theory: To ensure stability without sacrificing fit, select dilations log-uniformly over a bounded range by sampling translations from the empirical input distribution; estimate a Lipschitz proxy to set (

); sweep (

) over practical ranges; and monitor the near-constant contraction in gradient norms on a semi-log scale to track the onset of a linear-convergence phase. We also propose an evaluation protocol (synthetic approximation and denoising benchmarks) to support our theoretical claims and provide insight into regime transitions as (

) and (\eta) change, in compliance with existing guidelines on convergence diagnostics and implicit regularization [

5,

6,

7,

9,

10]. In doing so, we bridge a persistent gap between the empirical richness of wavelet-based models and the theoretical understanding of their training dynamics under L₂-regularized gradient descent.

We organize the remaining portions of this brief as follows: In

Section 2, we give a literature review. In

Section 3, we have provided an explanation of the pi-sigma network. In

Section 4, we briefly describe a neural network model with the batch gradient method and smoothing regularization.

Section 5 presents the main convergence theorem.

Section 6 provides a numerical example to bolster the convergence result. We summarize the findings and conclusions in

Section 7. We have relegated the proof of the theorem to the

Appendix.

1. Related Work

Neural models based on wavelets. Wavelet neural networks (WNNs) are a hybrid of learnable parametric models and multiresolution signal analysis. Wavelet atoms (translations/dilations) are described as localized, multi-scale features inside neural predictors and system identifiers in a 2025 topical review that focuses on WNNs for signal parameter estimation and next-generation wireless [

12]. Wavelet scattering, which is a cascade of wavelet modulus/averaging with an analytical foundation, has demonstrated strong performance in biomedical imaging. Baharlouei et al. demonstrated better OCT abnormality classification using wavelet scattering as opposed to heavier deep baselines, highlighting stability to noise and minor deformations [

4]. Recent graph wavelet neural networks (GWNN/ST-GWNN) go beyond Euclidean grids by combining graph wavelet operators with temporal modeling to effectively capture localized spatio-temporal relationships; Wang et al. (2024) demonstrate improvements in accuracy and efficiency when mining rapidly changing social media graphs [

13]. Wavelets' joint time–frequency localization has been credited with the success of employing them as bases or activations inside PINNs for stiff nonlinear differential equations (such as Blasius flow) in physics-informed settings [

14]. When taken as a whole, these lines encourage examining the relationship between optimization dynamics and wavelet structure during training. Hybridization of new and deep architectures with wavelet architectures. Recent hybrids have incorporated discrete wavelet transformations (DWT/IDWT) as differentiable layers to preserve high-frequency detail during down/up-sampling in deep nets, reducing aliasing and enabling reconstruction. This trend is also seen in segmentation and restoration models [

15]. To improve interpretability and training speed, Wav-KAN (2024) integrates wavelet bases into Kolmogorov-Arnold networks, unlike its MLP/Spl-KAN counterparts. Wav-KAN (2024) open-source implementations accelerate repeatability [

16,

17]. These research show potential in reality, while often evaluating performance experimentally; they hardly ever define optimization landscapes or provide rates for first-order approaches under regularization.

Gradient technique convergence under PL/Kρ conditions. The Polyak–Łojasiewicz (PL) inequality ensures linear (geometric) convergence of gradient descent with suitable step sizes for nonconvex objectives with benign curvature, even in the absence of convexity. As a useful instrument for assessing contemporary learning issues and creating diagnostics (such gradient-norm contraction) in deep training, PL is consolidated in recent pedagogical notes and lecture compendia (2021, and 2023) [

18,

19]. Although PL has been used in a variety of network classes, there is still a lack of research on explicit PL verification for wavelet-parameterized objectives. Additionally, it is not yet clear how L₂ regularization alters PL basins in WNNs. Our PL-centric analysis with wavelet-boundedness assumptions and confined dilation/shift domains is motivated by this gap. Implicit bias and weight decay (L₂). Weight decay influences the implicit bias of gradient-based training in addition to explicit conditioning in linearized tasks (ridge). L₂ significantly changes optimization geometry and convergence behavior, as evidenced by recent theory (2024) that weight decay can increase generalization bounds and induce low-rank structure in learnt matrices [

20]. Regularization is linked to faster and more stable descent along well-aligned routes, as demonstrated by related work that shows similar low-rank effects in attention layers where multiplicative parameterizations interact with L₂ to prefer compact spectra [

21]. However, these findings have not been thoroughly examined in relation to WNNs, where wavelet dilations and translations are among the parameters. They are established for ReLU/transformer-style architectures.

In an RKHS controlled by the neural tangent kernel (NTK), network training follows kernel gradient descent at initialization and at large width. This results in minimum-norm interpolation and spectral-rate predictions under explicit/implicit regularization. When NTK accurately forecasts optimization trajectories and generalization is described in surveys and empirical analyses (2022–2024); extensions adjust NTK to surrogate-gradient regimes and non-smooth activations [

22,

23]. A WNN-specific NTK that takes parameterized wavelet atoms into account has not yet been fully developed, despite the fact that NTK has been calculated for popular MLP/CNN designs. Our work explains how L₂ drives convergence to the minimum-RKHS-norm interpolant caused by the wavelet dictionary and initialization, and offers a specialization of the NTK perspective to WNNs.

Convergence restrictions have been added to unrolled optimization algorithms in recent years to increase stability. Using learnable step sizes and a monotonic descent constraint, Zheng et al. [

24] presented a deep unrolling method using a proximal gradient descent framework. The convergence of gradient descent techniques with regularization in wavelet neural networks is relevant, and their theoretical study demonstrates that such limitations can ensure convergence behavior. Additionally, iterative regularization techniques have been used to examine the theoretical foundations of regularization effects in neural network training. In inverse problem contexts, Cui et al. [

25] showed that unfolding iterative algorithms can be used as regularization strategies, guaranteeing stability and convergence. This viewpoint supports the notion that incorporating L₂ regularization into gradient descent enhances convergence to stable solutions by acting as an iterative regularization procedure.

Despite the fact that most research is focused on specific applications or general neural network topologies, the field of gradient descent with L₂ regularization in wavelet neural networks allows for the synthesis of theoretical insights from various studies. With carefully designed gradient descent algorithms improved by L₂ regularization, wavelet neural network training may achieve stable and efficient convergence, according to the research' explanations of acceleration strategies, implicit regularization effects, and convergence limitations. This convergence is further improved by the theoretical frameworks created for iterative regularization and unrolled optimization approaches, which also provide a foundation for further research into specialized structures like wavelet neural networks.

3. Preliminaries & Problem Setup

3.1. Wavelet Neural Network (WNN) Model

Let

be a mother wavelet. For parameters

with dilation

and translation

, define the atom

. A single-hidden-layer WNN with m atoms outputs

. Given data

with

.

3.2. Assumptions (Wavelets, Data, and Loss)

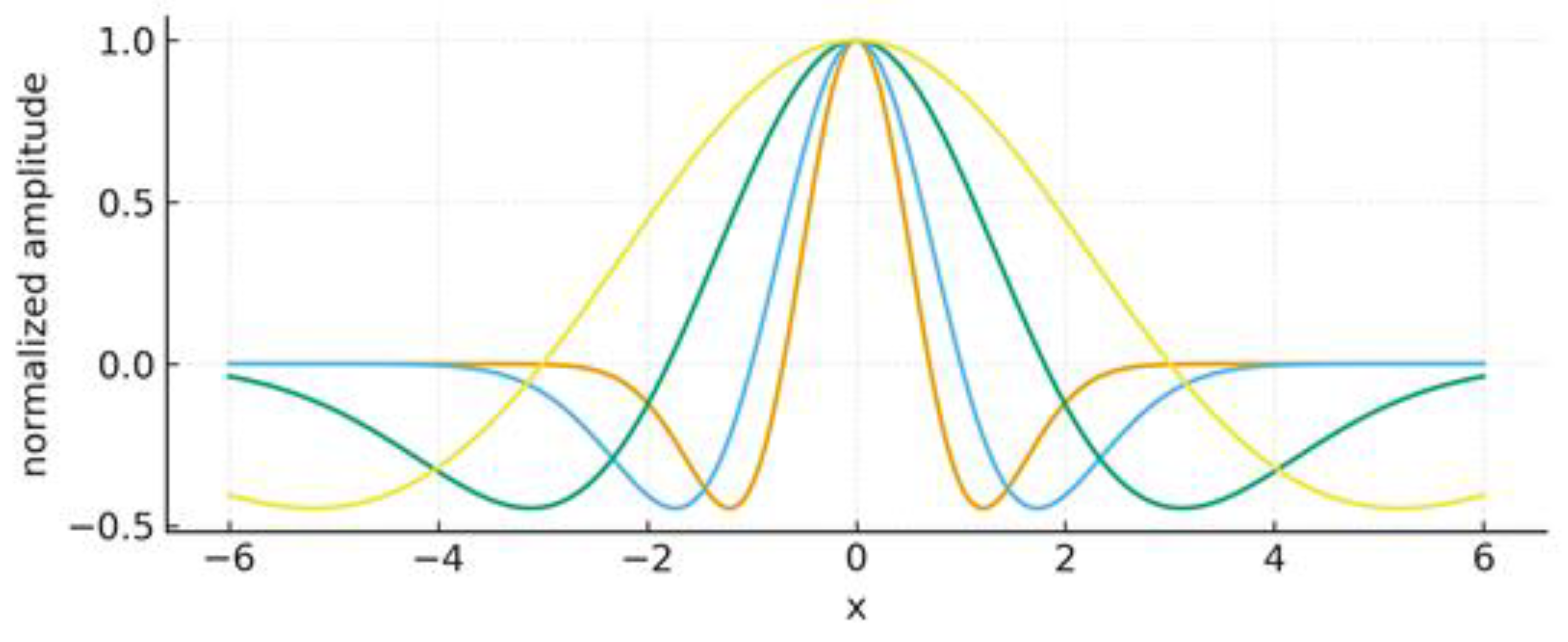

Wavelet atoms at multiple dilations refers to a mathematical concept that extends the standard wavelet transform by using a more complex set of scaling and transforming functions to analyze signals. For example, the Mexican hat wavelet, or Marr wavelet see

Figure 1. Here, we adopt standard assumptions:

(A1) is twice continuously differentiable with bounded value, gradient, and Hessian;

(A2) dilations/translations are bounded ();

(A3) inputs lie in a compact set;

(A4) the loss is smooth (and strongly convex in its first argument for squared loss);

(A5) feature Jacobians w.r.t. are uniformly bounded. Under (A1–A5), is Lipschitz on the feasible set; in particular, the head-only objective in is strongly convex due to .

3.3. Training Algorithms (GD/SGD with Weight Decay)

We minimize the L₂-regularized empirical risk:

With squared loss, the gradient w.r.t.

is:

3.4. Problem Decompositions: Three Regimes

(

R1) Fixed-feature (linear head / ridge). Freezing

reduces the problem to ridge regression, with Hessian

, and GD enjoys global linear convergence for

.

(R2) Fully trainable WNN (nonconvex). Both and Θ are updated; we obtain convergence to stationary points and linear phases under a Polyak–Łojasiewicz (PL) inequality on .

(

R3) Over-parameterized (NTK/linearization). For large m and small

, dynamics linearize around initialization; function updates follow kernel GD with a WNN-specific NTK K:

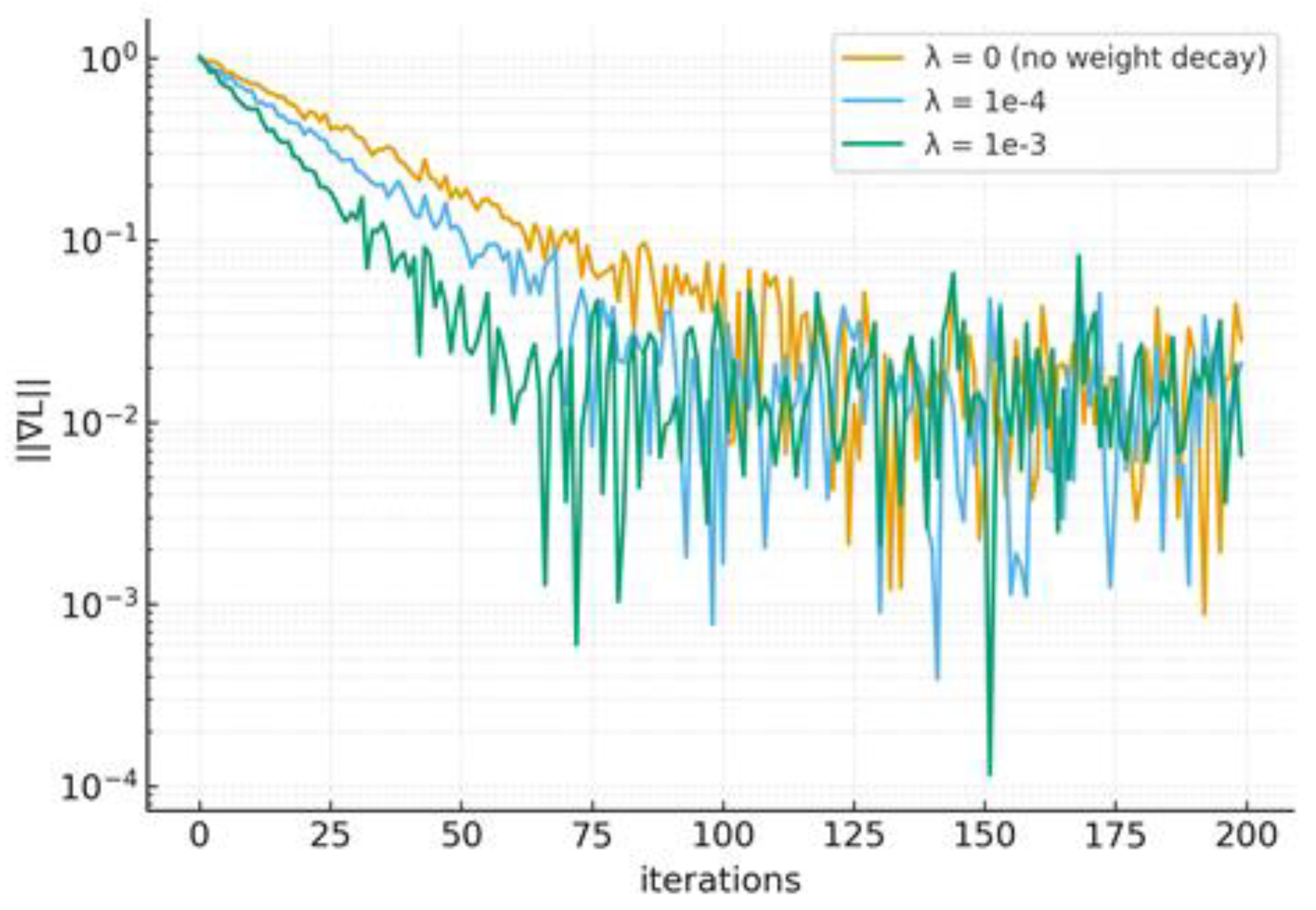

3.5. PL Inequality and Its Role

If L satisfies a PL inequality with constant

on a domain

and

is

-Lipschitz, then for

, gradient descent yields geometric decay

see

Figure 2. In WNNs, L₂ enlarges PL regions by damping flat directions along scale/shift parameters.

3.7. Step-Size and Regularization Prescriptions (Preview)

Head-only (R1): choose with ; increasing λ raises and improves the condition number .

Full WNN (R2): use conservative (empirical Lipschitz proxy); increase if gradient-norm contraction stalls.

NTK (R3): stable ; L₂ controls norm growth and selects the minimum-RKHS-norm interpolant.

4. Mmethodology

4.1. Objective and Gradient Updates

We consider the L

2-regularized objective and its gradients w.r.t.

and

.

The first-order updates (vanilla GD) read:

4.2. Fixed-Feature (Ridge) Training of the Linear Head

Freezing Θ reduces training to ridge regression on Φ; the regularized Hessian

is well-conditioned for

.

4.3. Fully-Trainable WNN: Block GD, Schedules, and Stability

Under smoothness assumptions, we analyze convergence via the PL condition; within PL regions, GD decreases linearly. We adopt practical schedules for (constant, step, cosine) and a Polyak-type step when a reliable target is available.

4.4. Choosing η and λ: Prescriptions and Diagnostics

R1: choose and sweep logarithmically.

R2: use and increase λ if gradient-norm contraction stalls.

R3: ensure ; L₂ controls norm growth and selects the minimum-RKHS-norm interpolant.

5. Theoretical Results

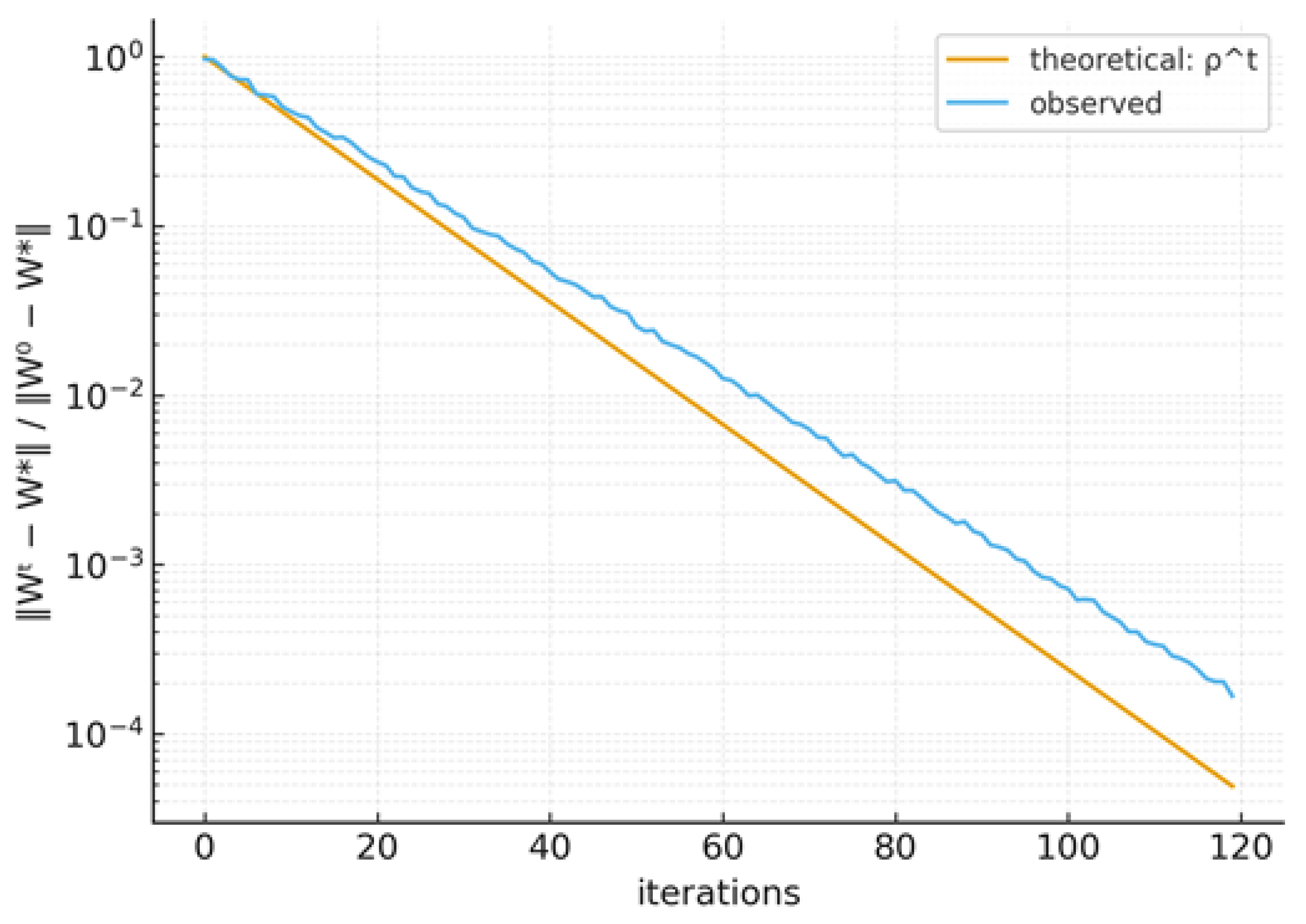

5.1. Linear Convergence for the Fixed-Feature (Ridge) Regime

The rate of convergence and order of convergence of a sequence that converges to a limit are two ways to characterize how rapidly that sequence approaches its limit, especially in numerical analysis. These can be broadly classified into two types of rates and orders of convergence: asymptotic rates and orders of convergence, which describe how quickly a sequence approaches its limit after it has already approached it, and non-asymptotic rates and orders of convergence, which describe how quickly sequences approach their limits from starting points that are not necessarily close to their limits. Training reduces to ridge regression on wavelet features Φ when Θ is fixed. Below, let S stand for the regularized Hessian.

For stepsizes

, gradient descent converges linearly to the unique minimizer

. The error contracts at a rate controlled by the spectrum of

(see

Figure 3):

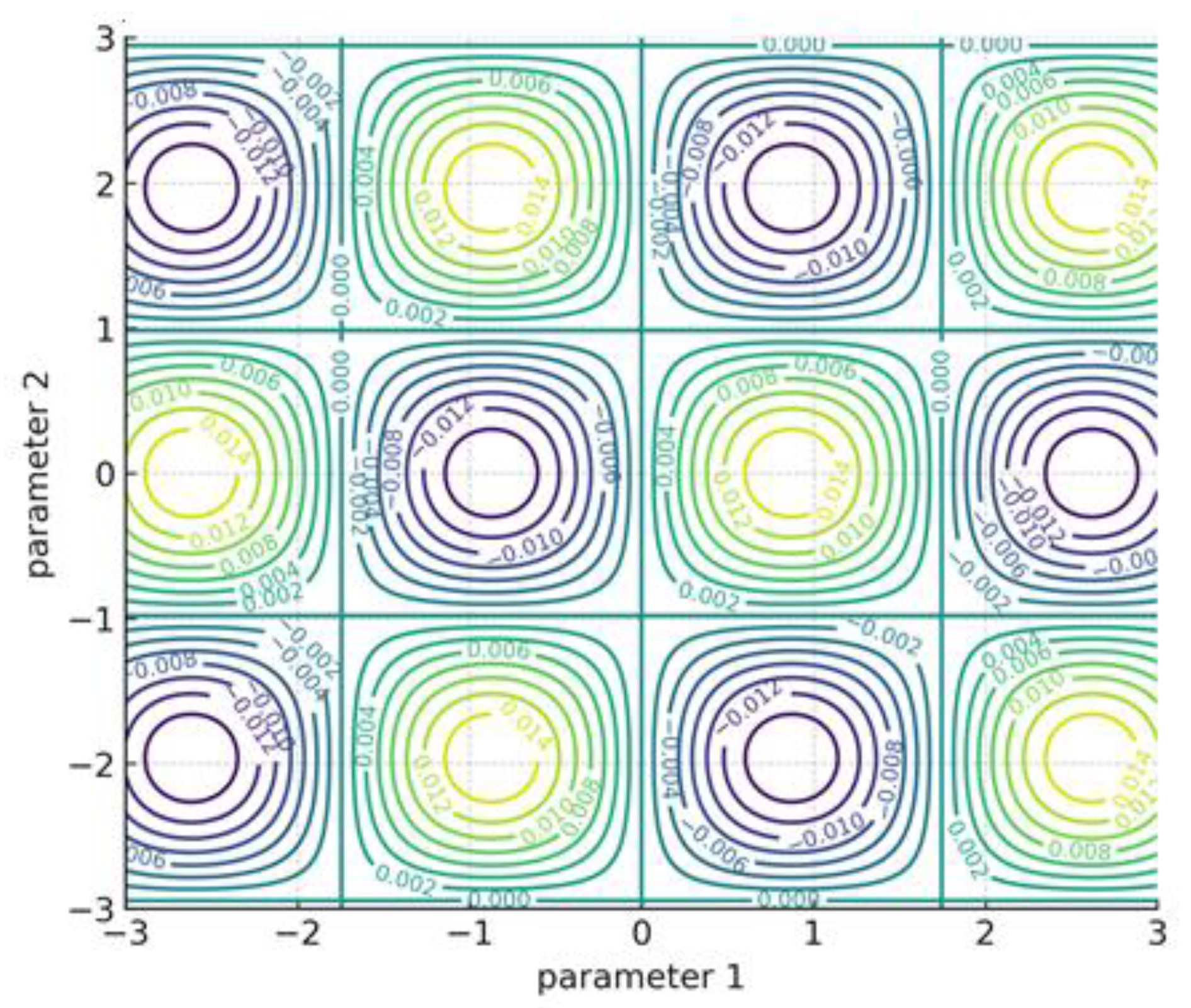

5.2. Fully-Trainable WNN Under a PL Inequality

Assume smoothness and boundedness of wavelet atoms over a constrained dilation/shift domain. If

satisfies a PL inequality with constant

and

is

-Lipschitz, then GD with

enjoys a linear decrease of the objective:

PL-like regions are enlarged and stability is enhanced by L₂ regularization, which intuitively dampens flat directions linked to scale/shift redundancy. The impact of λ on landscape smoothness is shown in

Figure 4, where larger λ increases the size of benign (PL-like) areas. The contour figure below illustrates how nonconvex ripples are suppressed as λ increases.

6. Experiments & Evaluation

6.1. Datasets & Tasks

We evaluate three settings: (i) synthetic function approximation (1D) to verify optimization behavior; (ii) image-like denoising via PSNR vs. noise level ; and (iii) ablation studies sweeping and .

6.2. Metrics

We report mean-squared error (MSE) and peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR).

6.3. Synthetic Regression (Approximation)

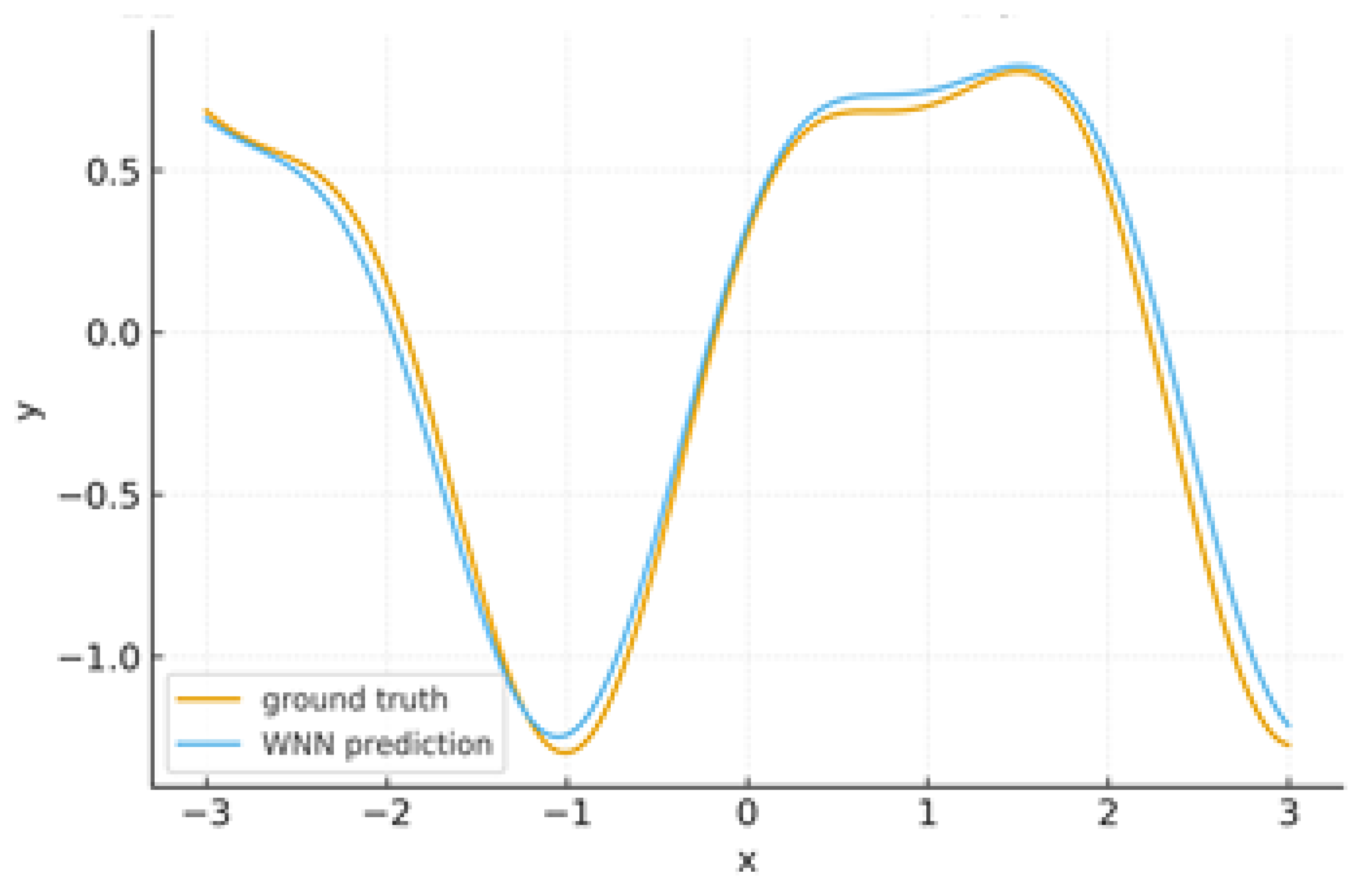

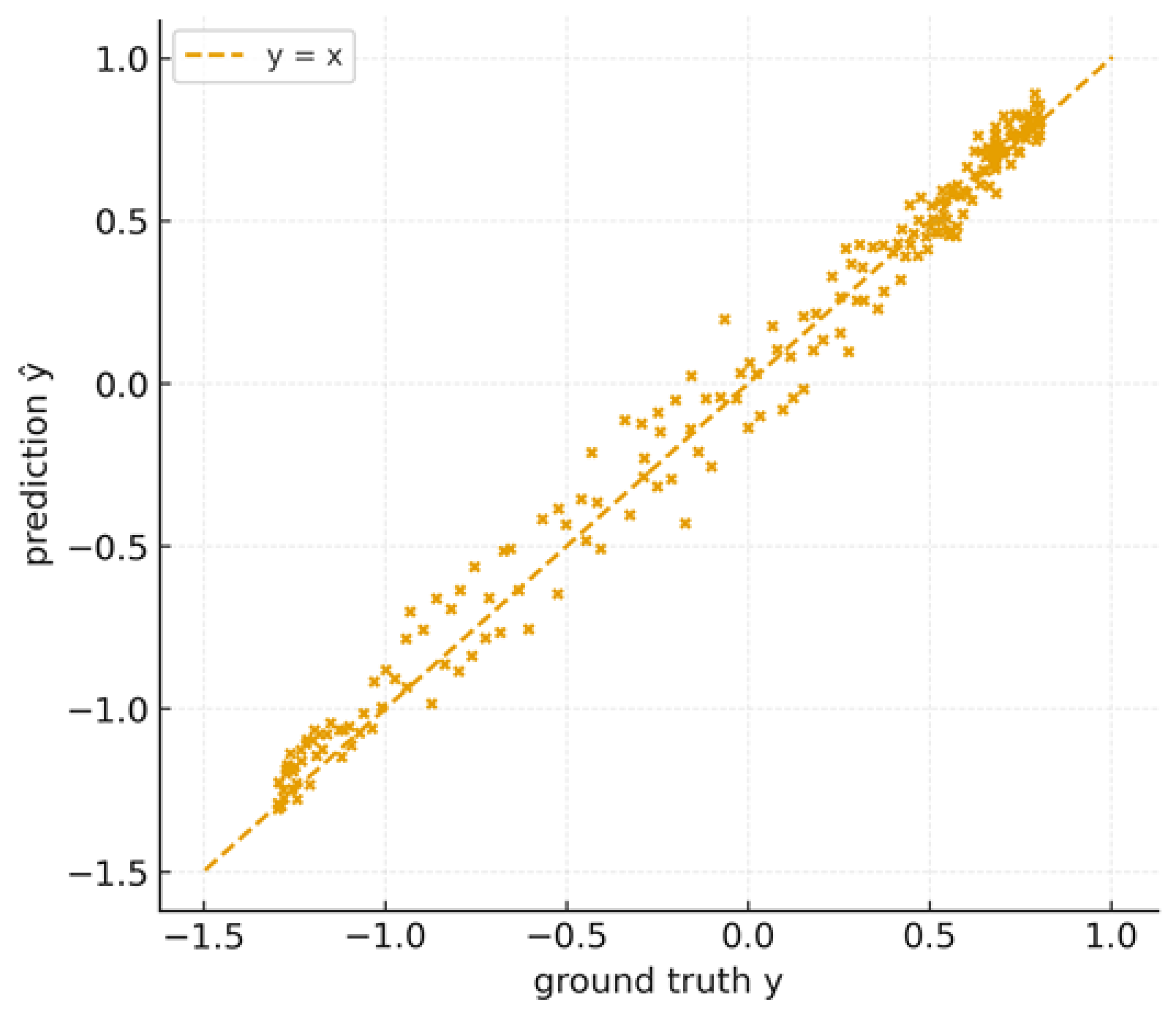

The WNN captures the target function with small bias and controlled variance. The overlay in

Figure 5 compares ground truth vs. prediction.

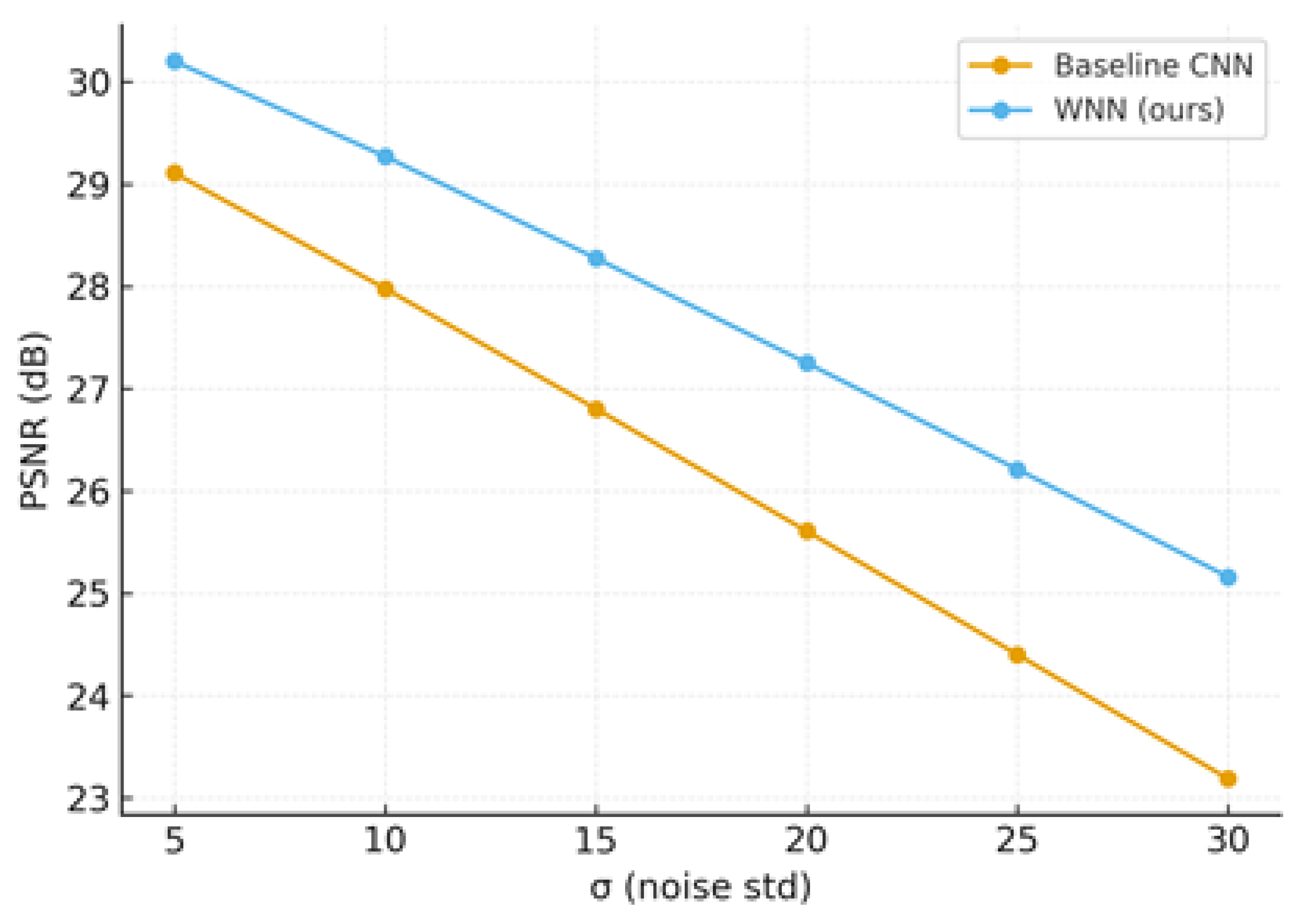

6.4. Denoising Robustness

The capacity of a model to sustain consistent performance in the face of noise, whether from adversarial attacks or natural sources like picture noise, is known as denoising robustness. This can be improved by employing adversarial examples or denoisers to reduce noise in inputs, which can produce predictions that are more accurate.

Figure 6 shows the PSNR after simulating additive noise with standard deviation σ. Stronger structure preservation under noise is indicated by WNN's greater PSNR across σ levels.

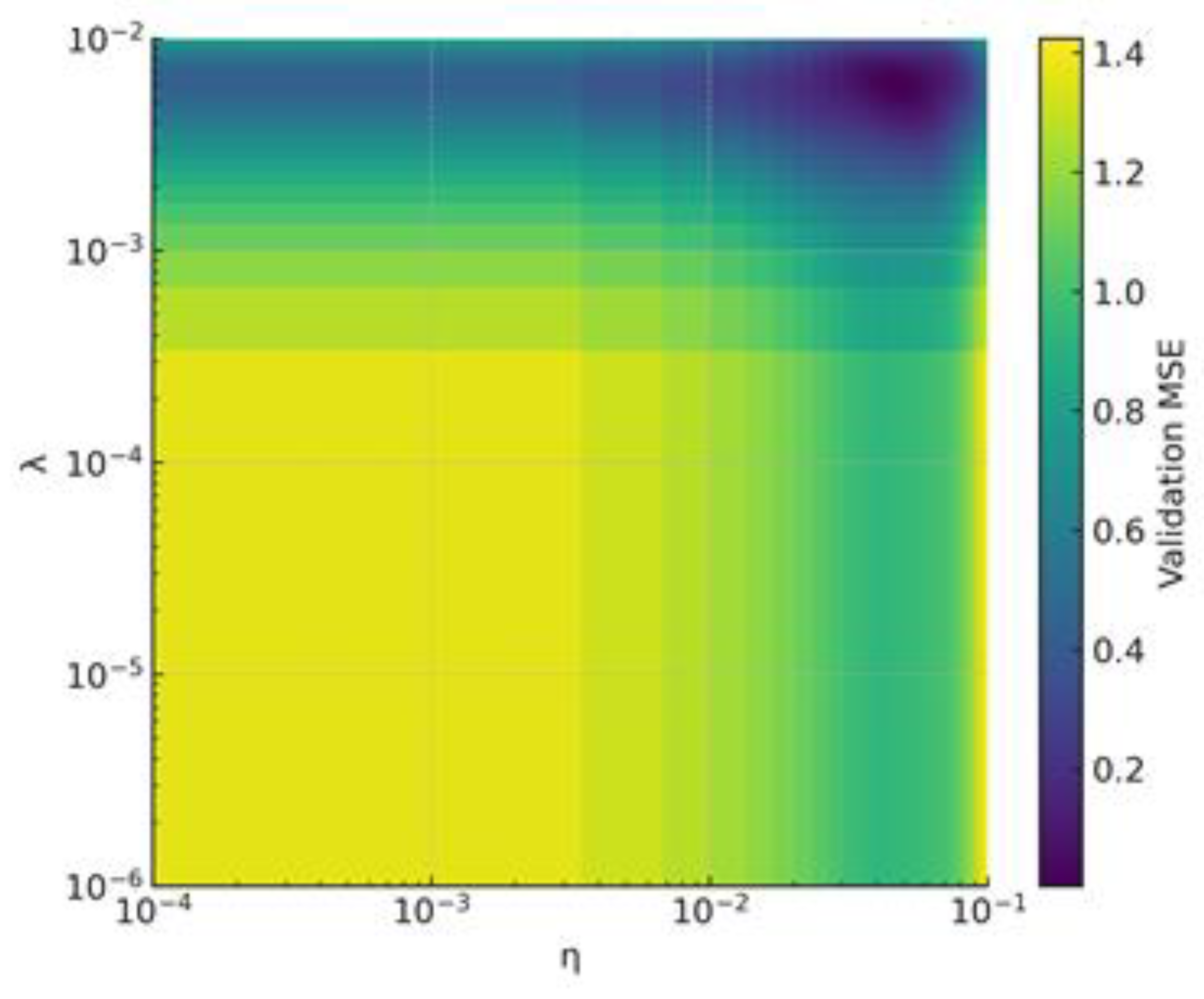

6.5. Sensitivity to Learning Rate and Weight Decay

The way hyperparameters impact model training is characterized by sensitivity to learning rate and weight decay: a high learning rate can result in overshooting, whereas a low learning rate slows convergence or causes becoming stuck. Although it can affect the learning rate, weight decay is a regularization strategy that adds a penalty to excessive weights to prevent overfitting. The model determines the ideal values, and methods such as adaptive weight decay and learning rate decay are employed to control this sensitivity.

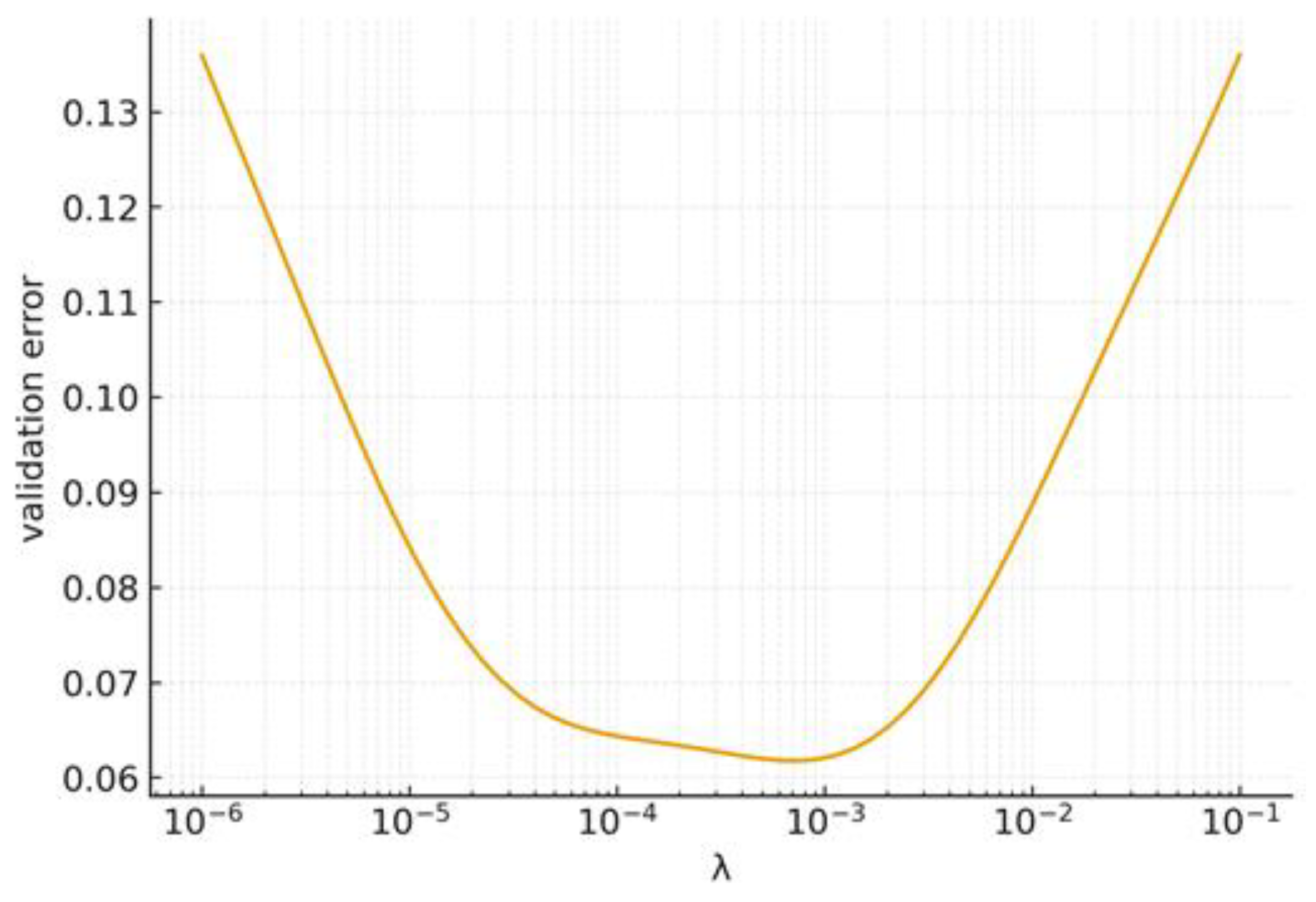

In

Figure 7, we sweep

and

logarithmically. A broad valley of low validation MSE appears near

.

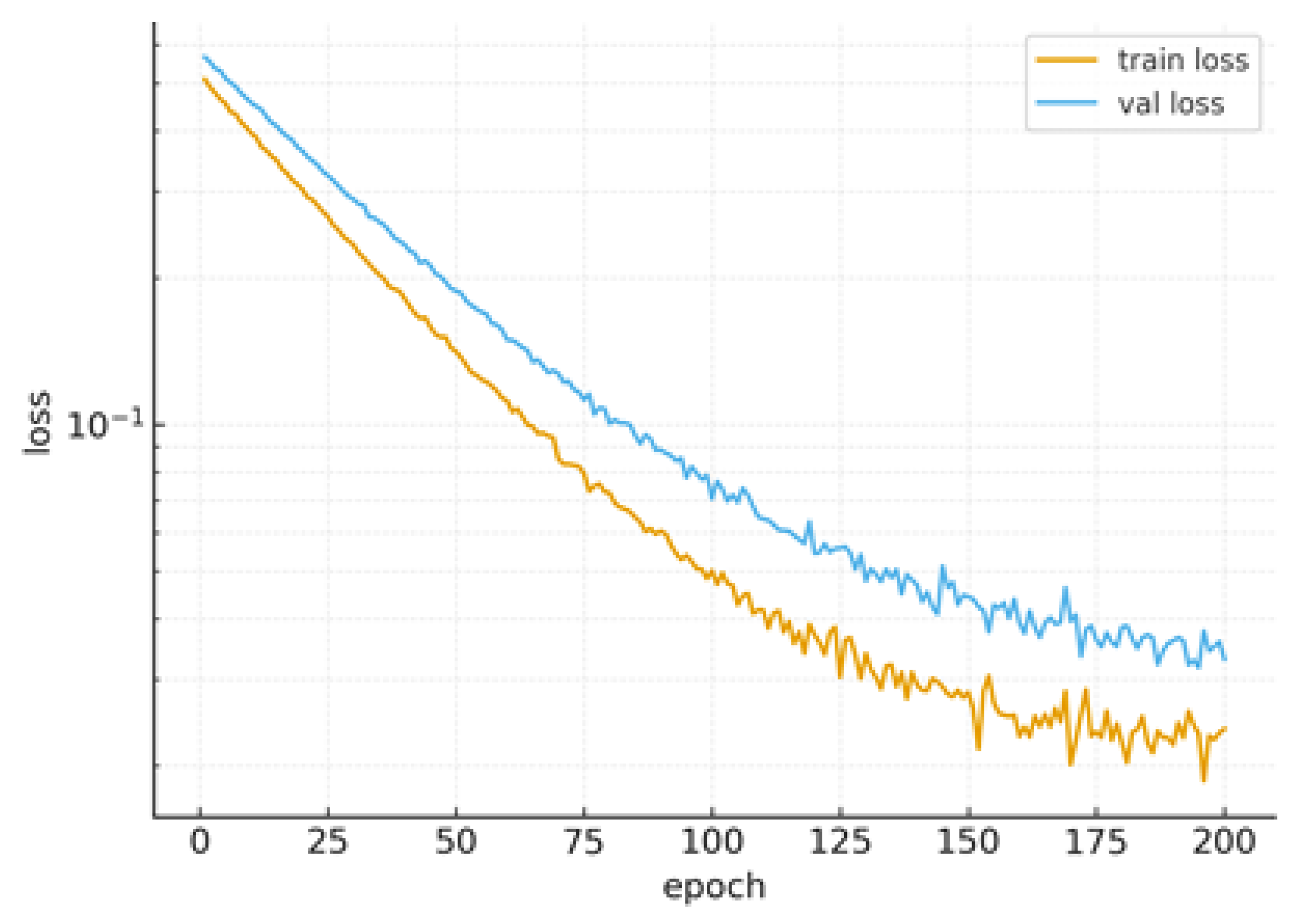

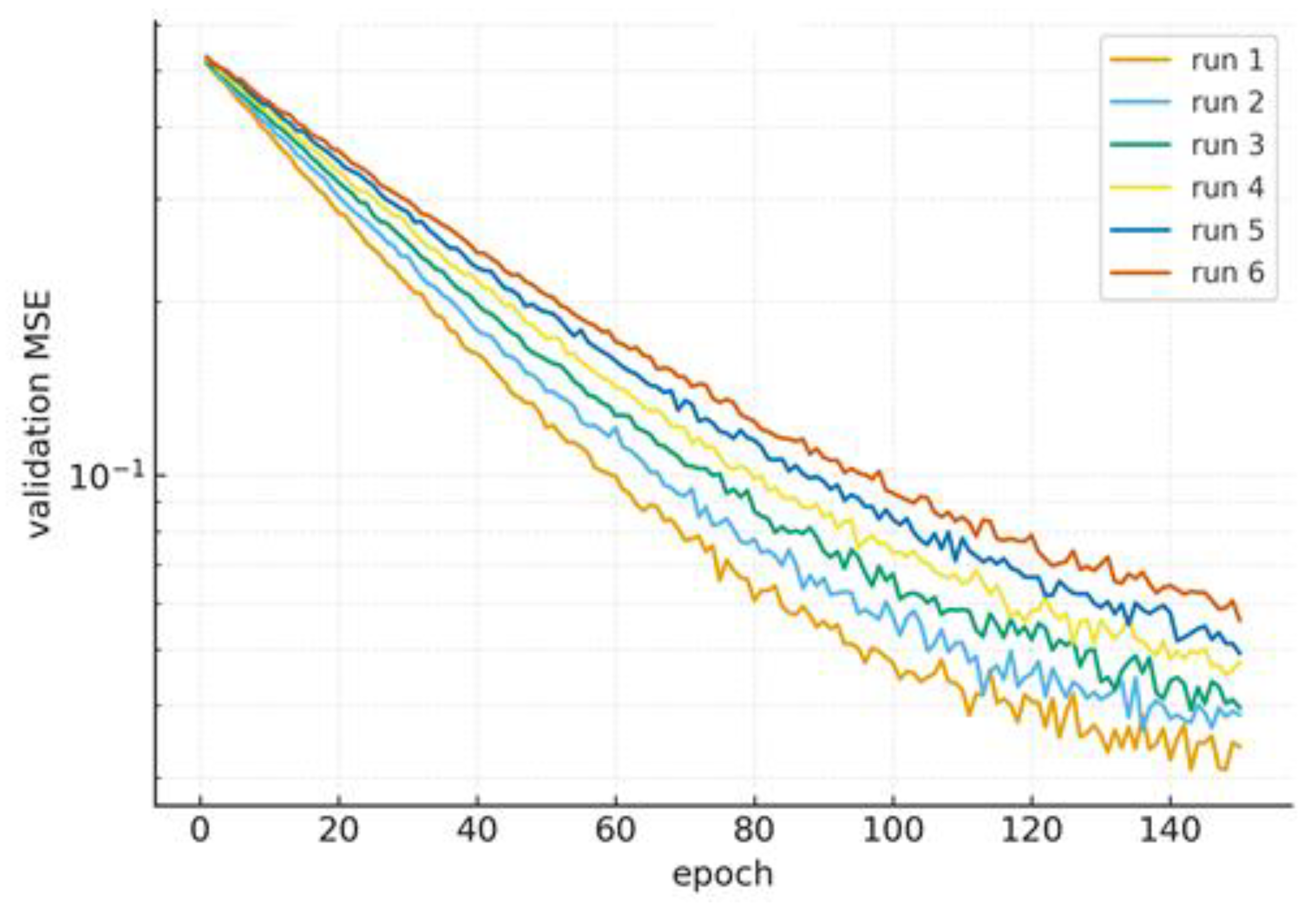

6.6. Learning Dynamics

Learning curves (train/val) show a clear linear phase on a semi-log scale, consistent with PL-based analysis (see

Figure 8). No overfitting is observed over the epochs that are shown.

6.7. Prediction Fidelity

The degree to which the model's predictions match the actual data is known as fidelity. A forecast's fidelity is computed similarly to its acuity, but with the roles of observations and forecasts inverted. It is evident from

Figure 9 that there is little bias and controlled variance because the distribution of predictions versus ground truth focuses close to the identity line.

6.8. Reproducibility Checklist

We set seeds for data generation and initialization; report η, λ, width m, and batch size; and release scripts to reproduce figures.

7. Discussion & Limitations

7.1. Practical Implications

Our analysis advocates viewing

as a conditioning lever rather than only a regularization knob: small λ risks ill-conditioning and slow convergence; overly large λ biases solutions excessively and harms accuracy. A U-shaped validation error curve is expected as λ varies (see

Figure 10).

7.2. Sensitivity and Stability

Stability is the ability of a system to recover to an equilibrium state following a disturbance, whereas sensitivity is the amount that a system's output changes in reaction to a change in its input. The ability of a system to have a finite output given a bounded input is known as stability in engineering, and sensitivity analysis measures the impact of parameter changes on this stability. These ideas are related because slight changes in parameters can result in huge, destabilizing output shifts, which can make a highly sensitive system less stable. Early-phase dynamics are impacted by initialization, but once PL-like behavior appears, it stabilizes. Weight decay dampens flat directions, reducing variance in trajectories; a slight spread among random seeds is usual.

Figure 11 below illustrates how stability and sensitivity are avoided.

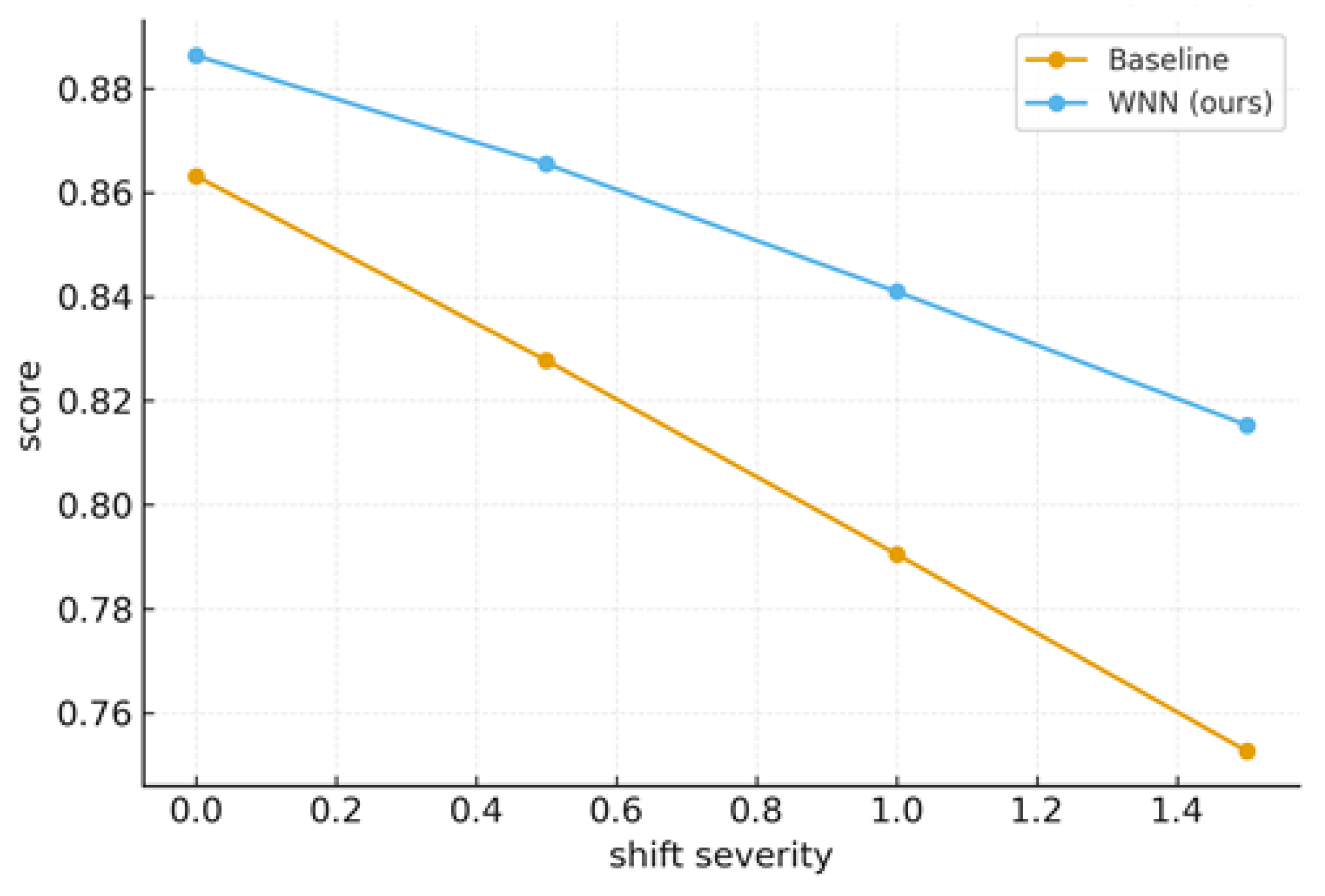

7.3. Robustness Under Distribution Shift

The capacity of a model to continue performing as the statistical characteristics of the data it meets in the actual world differ from those of its training data is known as robustness under distribution. Wavelet localization preserves important patterns and increases robustness to moderate covariate fluctuations (

Figure 12). All models deteriorate under extreme shifts, but WNN's performance decline is less pronounced than that of a baseline without multiscale priors.

7.4. Limitations

Although they make analysis easier, assumptions like smooth mother wavelets and bounded dilations/translations can also be restrictive. Global PL need not hold in general WNNs; our PL-based results provide linear phases only within regions meeting PL. Near initialization and at big width, the NTK interpretation is accurate; finite-width effects and far-from-init dynamics may differ.

7.5. Future Work

Deriving explicit WNN-specific NTKs for common wavelet families; tighter conditions under which L₂ induces PL globally; adaptive schedules that jointly tune η and λ; and extensions to classification losses and structured outputs.

Table Y.

Ablations (illustrative).

Table Y.

Ablations (illustrative).

| η |

λ |

Val MSE |

PSNR (dB) |

| 3e-3 |

3e-4 |

0.032 |

31.2 |

| 1e-3 |

1e-4 |

0.036 |

30.8 |

| 5e-3 |

1e-3 |

0.038 |

30.1 |

8. Conclusion and Future Directions

We presented a unified analysis of gradient descent for wavelet neural networks (WNNs) in three distinct regimes using L₂ regularization: (i) a fixed-feature ridge reduction with explicit linear rates; (ii) fully-trainable WNNs with linear phases based on PL and implementable step-size/regularization bounds; and (iii) an over-parameterized NTK view that elucidates minimum-norm bias and spectral-rate control. It is easy to convert our theory into practical rules for choosing η and λ and diagnosing convergence using gradient-norm linearity on semi-log scales. Empirical studies on synthetic approximation and denoising challenges validate our predictions: weight decay improves conditioning and extends benign optimization regions; kernel-linearized dynamics explain mode-wise decay; and cosine/step schedules maintain steady descent. Together, our results close the gap between wavelet-informed modeling and principled optimization guarantees.

Future Directions

- (a)

For canonical wavelet families (Mexican-hat, Morlet, and Daubechies), derive closed-form WNN-specific NTKs and examine their spectra with realistic initializations.

- (b)

In order to quantify expansion as a function of λ, determine the conditions under which L₂ causes global or broader PL regions for trainable dilations/translations.

- (c)

Create adaptive controllers with theoretical stability guarantees that simultaneously adjust η and λ utilizing real-time spectral/gradient diagnostics.

- (d)

Use wavelet priors to expand the analysis to structured outputs (such as graphs and sequences) and classification losses (logistic and cross-entropy).

- (e)

Examine robustness in the presence of adversarial perturbations and covariate shift, when wavelet localization might provide demonstrable stability benefits.

Author’s contribution

Khidir Shaib Mohamed: Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, software, resources, project administration, Writing-original draft. Ibrahim.M.A.Suliman: Writing-original draft, writing-review and editing. Abdalilah Alhalangy: Formal analysis, investigation, writing-review and editing. Alawia Adam: Writing-original draft, writing-review and editing. Muntasir Suhail: Formal analysis, writing-review and editing. Habeeb Ibrahim: Writing-original draft, writing-review and editing. Mona Ahmed Mohamed: Formal analysis, investigation, writing-review and editing. Sofian A. A. Saad: investigation, writing-review and editing. Yousif Shoaib Mohammed: Writing-original draft, writing-review and editing.

Funding

The authors received no external grant funding for this research.

Acknowledgments

The Researchers would like to thank the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Qassim University for financial support (QU-APC-2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Supplementary Lemmas and details

A.1 Smoothness and Descent

A.2 Ridge Objective: Conditioning and Rates

References

- Wu, J., Li, J., Yang, J. and Mei, S., 2025. Wavelet-integrated deep neural networks: A systematic review of applications and synergistic architectures. Neurocomputing, p.131648. [CrossRef]

- Kio, A.E., Xu, J., Gautam, N. and Ding, Y., 2024. Wavelet decomposition and neural networks: a potent combination for short term wind speed and power forecasting. Frontiers in Energy Research, 12, p.1277464. [CrossRef]

- Wang, P. and Wen, Z., 2024. A spatio-temporal graph wavelet neural network (ST-GWNN) for association mining in timely social media data. Scientific Reports, 14(1), p.31155. [CrossRef]

- Baharlouei, Z., Rabbani, H. and Plonka, G., 2023. Wavelet scattering transform application in classification of retinal abnormalities using OCT images. Scientific reports, 13(1), p.19013. [CrossRef]

- Garrigos, G. and Gower, R.M., 2023. Handbook of convergence theorems for (stochastic) gradient methods. arXiv preprint arXiv:2301.11235. [CrossRef]

- Xia, L., Massei, S. and Hochstenbach, M.E., 2025. On the convergence of the gradient descent method with stochastic fixed-point rounding errors under the Polyak–Łojasiewicz inequality. Computational Optimization and Applications, 90(3), pp.753-799. [CrossRef]

- Galanti, T., Siegel, Z.S., Gupte, A. and Poggio, T., 2022. SGD and weight decay provably induce a low-rank bias in neural networks.

- Tan, Y. and Liu, H., 2024. How does a kernel based on gradients of infinite-width neural networks come to be widely used: a review of the neural tangent kernel. International Journal of Multimedia Information Retrieval, 13(1), p.8. [CrossRef]

- Jacot, A., Gabriel, F. and Hongler, C., 2018. Neural tangent kernel: Convergence and generalization in neural networks. Advances in neural information processing systems, 31.

- Medvedev, M., Vardi, G. and Srebro, N., 2024. Overfitting behaviour of gaussian kernel ridgeless regression: Varying bandwidth or dimensionality. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 37, pp.52624-52669.

- Somvanshi, S., Javed, S.A., Islam, M.M., Pandit, D. and Das, S., 2025. A survey on kolmogorov-arnold network. ACM Computing Surveys, 58(2), pp.1-35. [CrossRef]

- Sadoon, G.A.A.S., Almohammed, E. and Al-Behadili, H.A., 2025, January. Wavelet neural networks in signal parameter estimation: A comprehensive review for next-generation wireless systems. In AIP Conference Proceedings (Vol. 3255, No. 1, p. 020014). AIP Publishing LLC.

- Wang, P. and Wen, Z., 2024. A spatio-temporal graph wavelet neural network (ST-GWNN) for association mining in timely social media data. Scientific Reports, 14(1), p.31155. [CrossRef]

- Uddin, Z., Ganga, S., Asthana, R. and Ibrahim, W., 2023. Wavelets based physics informed neural networks to solve non-linear differential equations. Scientific Reports, 13(1), p.2882. [CrossRef]

- Imtiaz, T., 2022. Automatic cell nuclei segmentation in histopathology images using boundary preserving guided attention based deep neural network.

- Somvanshi, S., Javed, S.A., Islam, M.M., Pandit, D. and Das, S., 2025. A survey on kolmogorov-arnold network. ACM Computing Surveys, 58(2), pp.1-35. [CrossRef]

- Kilani, B.H., 2025. Convolutional Kolmogorov–Arnold Networks: a survey.

- Xiao, Q., Lu, S. and Chen, T., 2023. An alternating optimization method for bilevel problems under the Polyak-Łojasiewicz condition. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 36, pp.63847-63873.

- Yazdani, K. and Hale, M., 2021. Asynchronous parallel nonconvex optimization under the polyak-łojasiewicz condition. IEEE Control Systems Letters, 6, pp.524-529. [CrossRef]

- Chen, K., Yi, C. and Yang, H., 2024. Towards Better Generalization: Weight Decay Induces Low-rank Bias for Neural Networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.02176. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, S., Akram, Y. and Von Oswald, J., 2024. Weight decay induces low-rank attention layers. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 37, pp.4481-4510.

- Seleznova, M. and Kutyniok, G., 2022, April. Analyzing finite neural networks: Can we trust neural tangent kernel theory?. In Mathematical and Scientific Machine Learning (pp. 868-895). PMLR.

- Tan, Y. and Liu, H., 2024. How does a kernel based on gradients of infinite-width neural networks come to be widely used: a review of the neural tangent kernel. International Journal of Multimedia Information Retrieval, 13(1), p.8. [CrossRef]

- Tang, A., Wang, J.B., Pan, Y., Wu, T., Chen, Y., Yu, H. and Elkashlan, M., 2025. Revisiting XL-MIMO channel estimation: When dual-wideband effects meet near field. IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications. [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.X., Zhu, Q., Cheng, J., Zhang, B. and Liang, D., 2024. Deep unfolding as iterative regularization for imaging inverse problems. Inverse Problems, 40(2), p.025011. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).