1. Introduction

Environmental pollutants are toxic substances introduced into the environment from both anthropogenic and natural sources. Certain industrial and ecological processes—such as synthetic chemical manufacturing, coal processing, and waste incineration—pose significant threats to abiotic components (water, air, and soil) as well as biotic communities (animals, plants, and humans) [

1,

2,

3]. Numerous heavy metals—including arsenic (As), cadmium (Cd), chromium (Cr), copper (Cu), mercury (Hg), nickel (Ni), plumbum (Pb), and zinc (Zn)—currently represent a global environmental hazard, adversely affecting human health [

3]. These elements are highly persistent in the environment, with half-lives exceeding twenty years [

4]. For instance, plumbum (Pb) can persist in soil for 150 to 5,000 years and remain at elevated concentrations for up to 150 years following the application of sewage sludge [

5], while the biological half-life of cadmium (Cd) in organisms ranges from 10 to 30 years [

6].

The removal of heavy metals from the environment presents a major challenge, as these elements are neither biologically nor chemically degradable. Conventional remediation strategies for contaminated soils include both ex situ and in situ technologies, such as chemical reduction, electrokinetic remediation, excavation, pneumatic fracturing, soil washing, solidification, and vitrification. Traditional “pump-and-treat” or “dig-and-dump” approaches are generally limited to small-scale sites and suffer from significant technical, economic, and ecological constraints [

7].

Heavy metals are also highly toxic due to their high lethality and their toxic, genotoxic, teratogenic, and mutagenic effects on living organisms. Even at low concentrations, they can induce endocrine disruption and neurological disorders [

8,

9,

10].

In recent decades, plant-based environmental restoration—particularly phytoremediation—has garnered considerable global interest as a sustainable strategy for decontaminating polluted soils [

11,

12]. Among emerging remediation techniques, phytoremediation is now widely regarded as one of the most promising approaches in industrially developed regions [

13]. Certain plant species naturally thriving on contaminated sites can accumulate substantial amounts of heavy metals in their tissues without exhibiting visible phytotoxic symptoms [

14]. This method is cost-effective, environmentally benign, operationally simple, and applicable across diverse and ecologically degraded landscapes [

15,

16,

17,

18].

Phytoremediation—defined as the use of plants to extract, contain, or immobilize soil contaminants—represents an innovative and economically viable alternative to conventional remediation. However, its widespread adoption is often limited by the relatively slow growth rates of many hyperaccumulator species and the prolonged time required to achieve significant contaminant reduction [

19]. Consequently, current research prioritizes the identification and development of plant species that combine high metal accumulation capacity, substantial biomass production, and economic value [

20].

A key advantage of phytoremediation lies in the ability to remove pollutants by harvesting and processing metal-laden biomass. The simplicity of biomass collection and post-harvest management—such as incineration followed by safe ash disposal or utilization of ash as a secondary raw material—enhances the practicality and sustainability of this approach [

21,

22,

23,

24].

Among cultivated hyperaccumulator candidates, sunflower, alfalfa, and jute have received particular attention. Sunflower (

Helianthus annuus L.) exhibits a strong capacity for heavy metal uptake [

25]. Sponge gourd (

Luffa aegyptiaca Mill.), an annual vegetable crop, demonstrates adaptability to diverse growing conditions, though cultivar-specific differences in the uptake of chromium (Cr), cadmium (Cd), plumbum (Pb), and zinc (Zn) have been reported [

26]. Jute (

Corchorus capsularis L.) is characterized by rapid growth and high biomass yield, enabling multiple harvests within a single growing season and thereby reducing internal metal concentrations through dilution [

27].

Sweet sorghum (

Sorghum bicolor L.) has emerged as a highly promising species for phytoremediation. It displays remarkable tolerance to extreme levels of heavy metal contamination and produces abundant above-ground biomass. Its efficient translocation of metal ions from roots to shoots and leaves confers significant potential for phytoextraction of toxic metals from polluted soils [

28]. Importantly, all these species are not only effective phytoremediants but also economically valuable crops, making them ideal candidates for integrated agro-remediation systems.

The accumulation of heavy metals in plants is influenced not only by the concentration and chemical speciation of metals in the soil but also by interactions with other elements exhibiting antagonistic or synergistic effects. Key criteria for selecting suitable species for phytoextraction include: adaptability to local soil and climatic conditions, tolerance to high contaminant loads, rapid growth, high biomass yield, extensive root system, efficient metal translocation to aerial parts, resistance to phytopathogens, and compatibility with mechanized agricultural practices [

29,

30,

31].

2. Results

2.1. Selection of High-Performing Sweet Sorghum Genotypes for Phytoremediation

During in vitro culture of somatic cells of sweet sorghum (

Sorghum bicolor L.), significant variation in callus induction capacity was observed among the tested genotypes (

Table 1). The highest callus formation frequencies were recorded for Hybrid-2 (69.11%), SAB-3 (43.83%), SABB-1 (42.31%), and SAB-10 (40.32%). Moderate callus induction was observed in SAB-11 (36.70%) and Hybrid-1 (25.33%), whereas SAB-2 exhibited an extremely low response, with only 4.47% of explants producing callus.

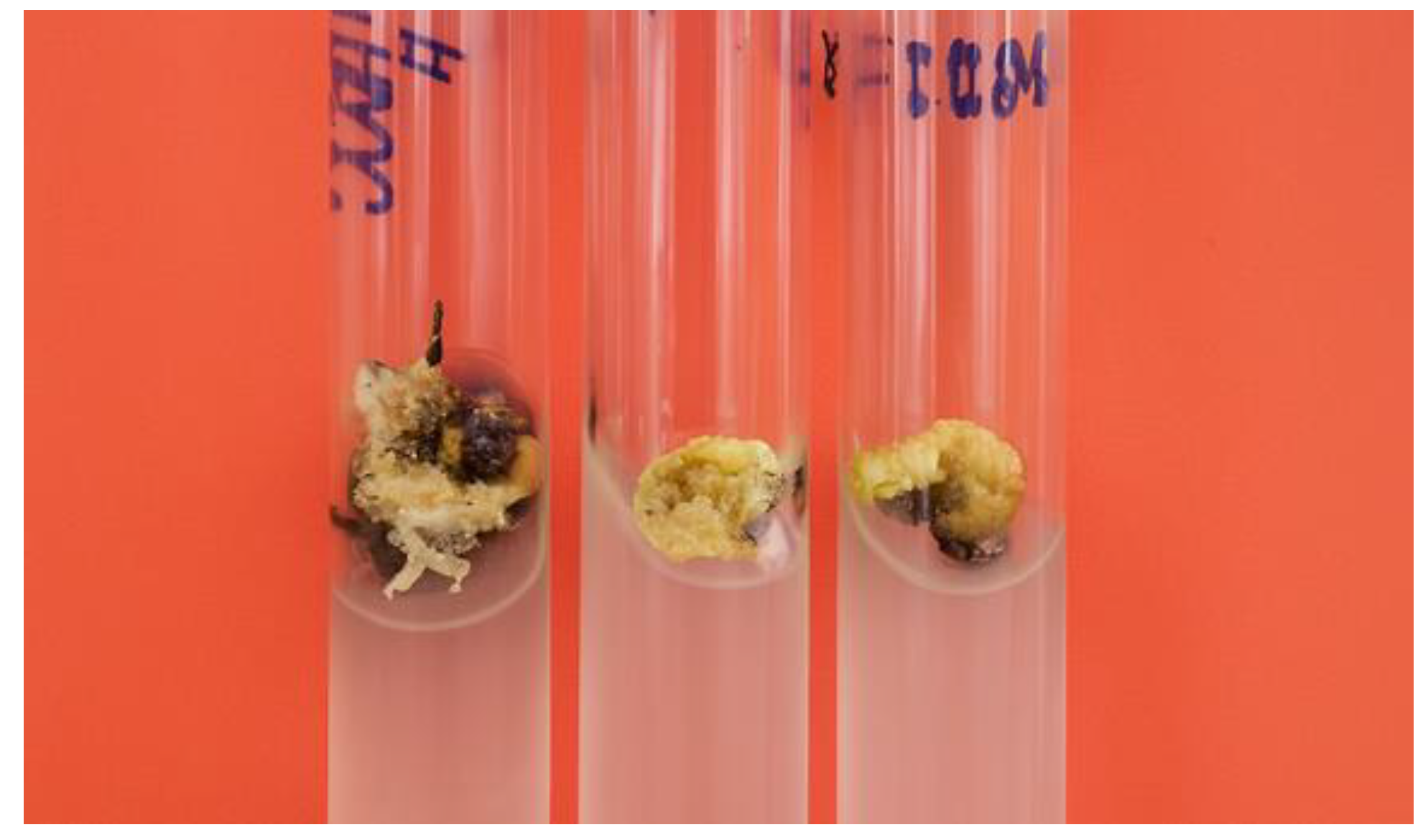

The resulting callus tissues also differed markedly in morphology and developmental potential. In most cases, the calli remained non-morphogenic, appearing as loose, undifferentiated aggregates of parenchyma-like cells (

Figure 1).

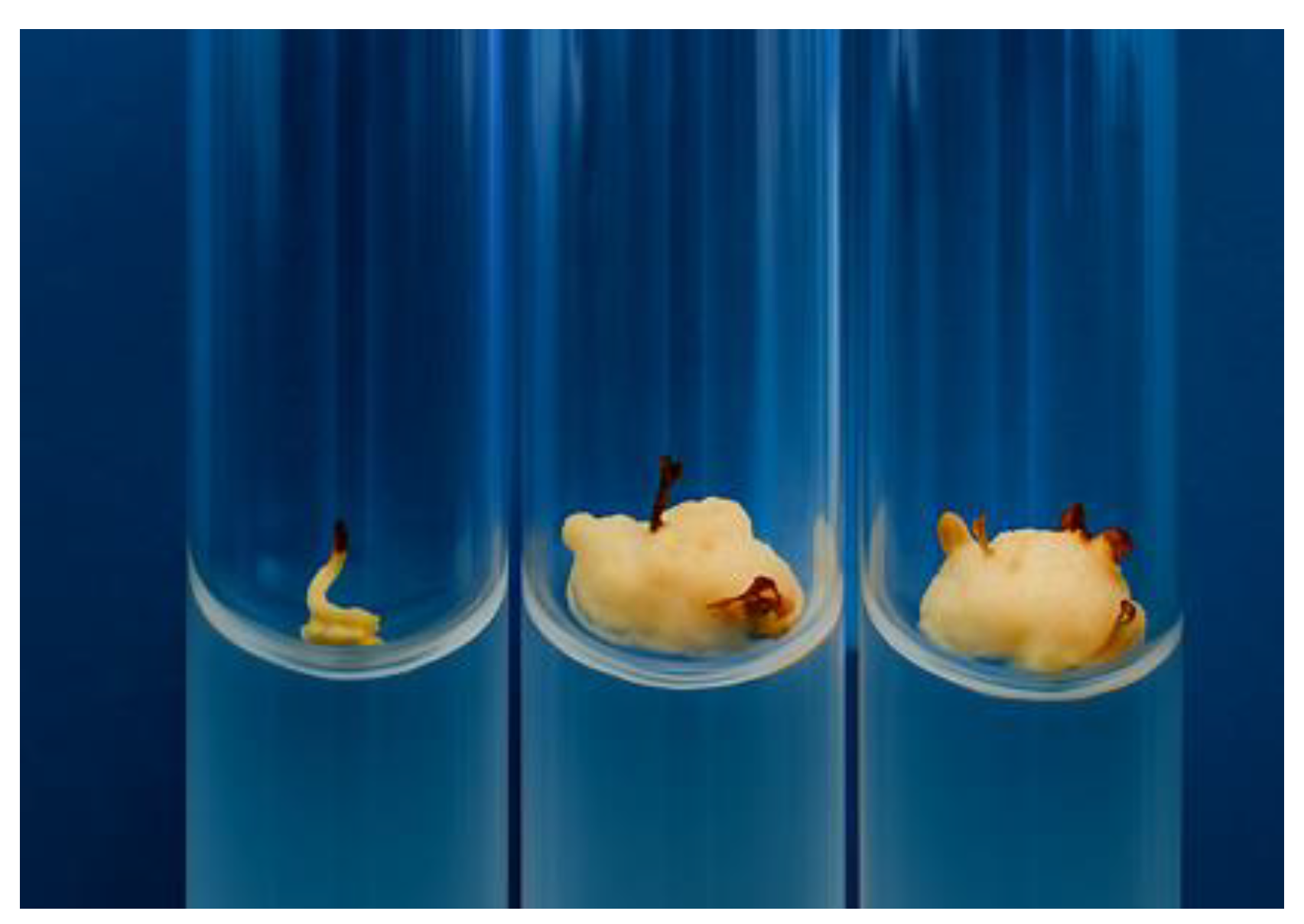

Nevertheless, certain genotypes produced callus tissues exhibiting clear signs of morphogenesis, indicating their potential suitability for subsequent micropropagation and clonal propagation programs.

Of particular interest are the genotypes that produced morphogenic calli characterized by dense tissue organization and actively dividing meristematic cells (

Figure 2).

These calli exhibited a whitish coloration and maintained a high proliferative capacity upon subculturing onto fresh nutrient media. The frequency of morphogenic callus formation varied among genotypes, with the highest values observed in Hybrid-2 (27.94%) and SAB-3 (23.28%) (

Table 2), confirming the superior morphogenetic potential of these lines.

As a result of the conducted studies, a collection of valuable genotypes of sweet sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L.) has been developed, intended for use as a feedstock in phytoremediation applications. Optimal seed pre-sowing treatments were identified, which promote vigorous development of both the root system and the aboveground parts of seedlings. Enhanced root and leaf growth represents a key physiological factor determining the overall growth intensity and, ultimately, the yield potential of the plants.

Given the critical role of these traits in plant adaptation to environmental conditions, the next phase of the research involved phenological observations. These assessments enabled the classification of sweet sorghum genotypes according to their growing season duration into early-, mid-, and late-maturing groups, all of which demonstrated good adaptability to the arid conditions of southeastern Kazakhstan. Furthermore, field trials conducted under extreme arid conditions identified genotypes exhibiting resistance to major diseases. In contrast, less resistant genotypes showed susceptibility to smut, root rot, and Fusarium wilt [

32,

33].

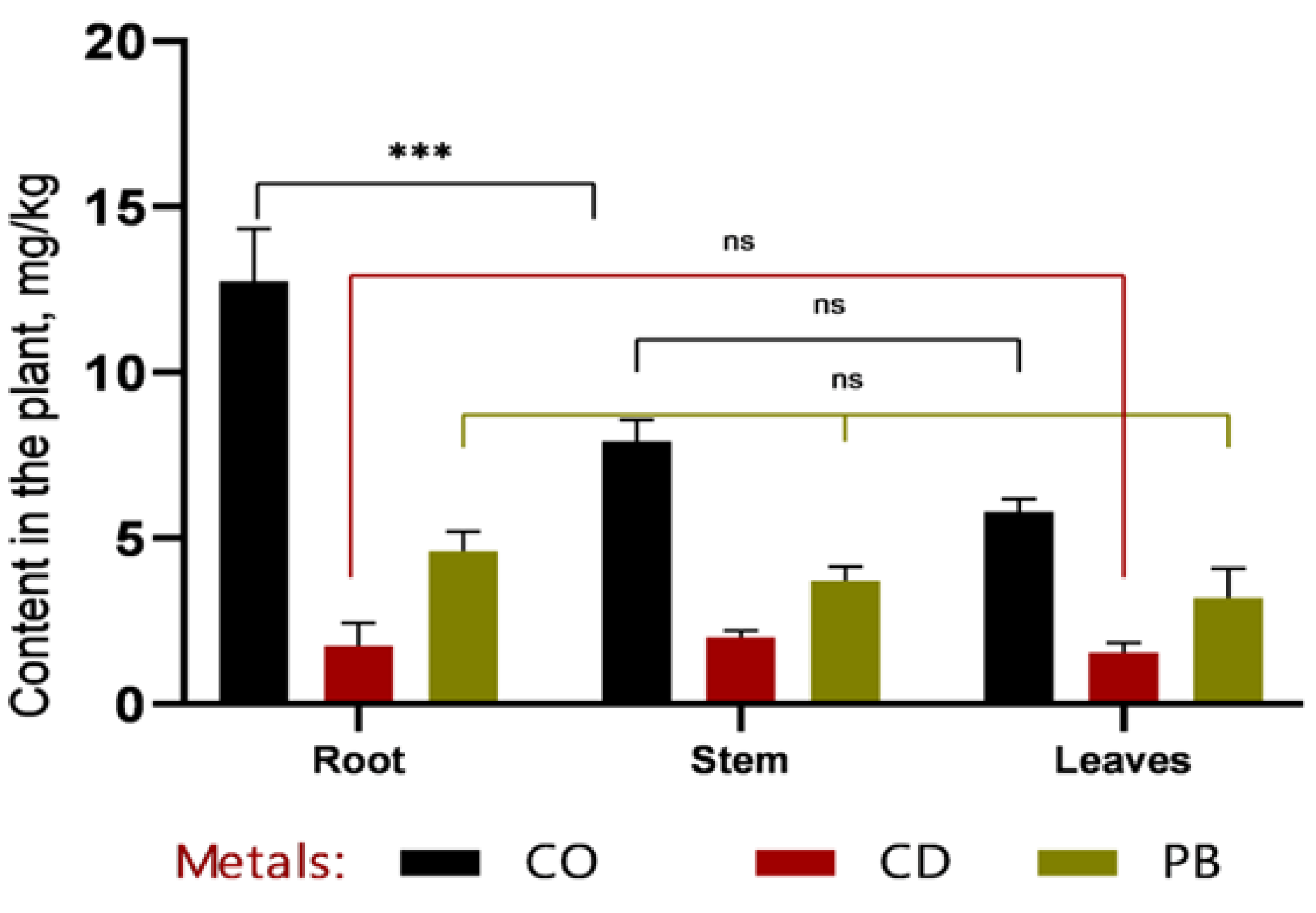

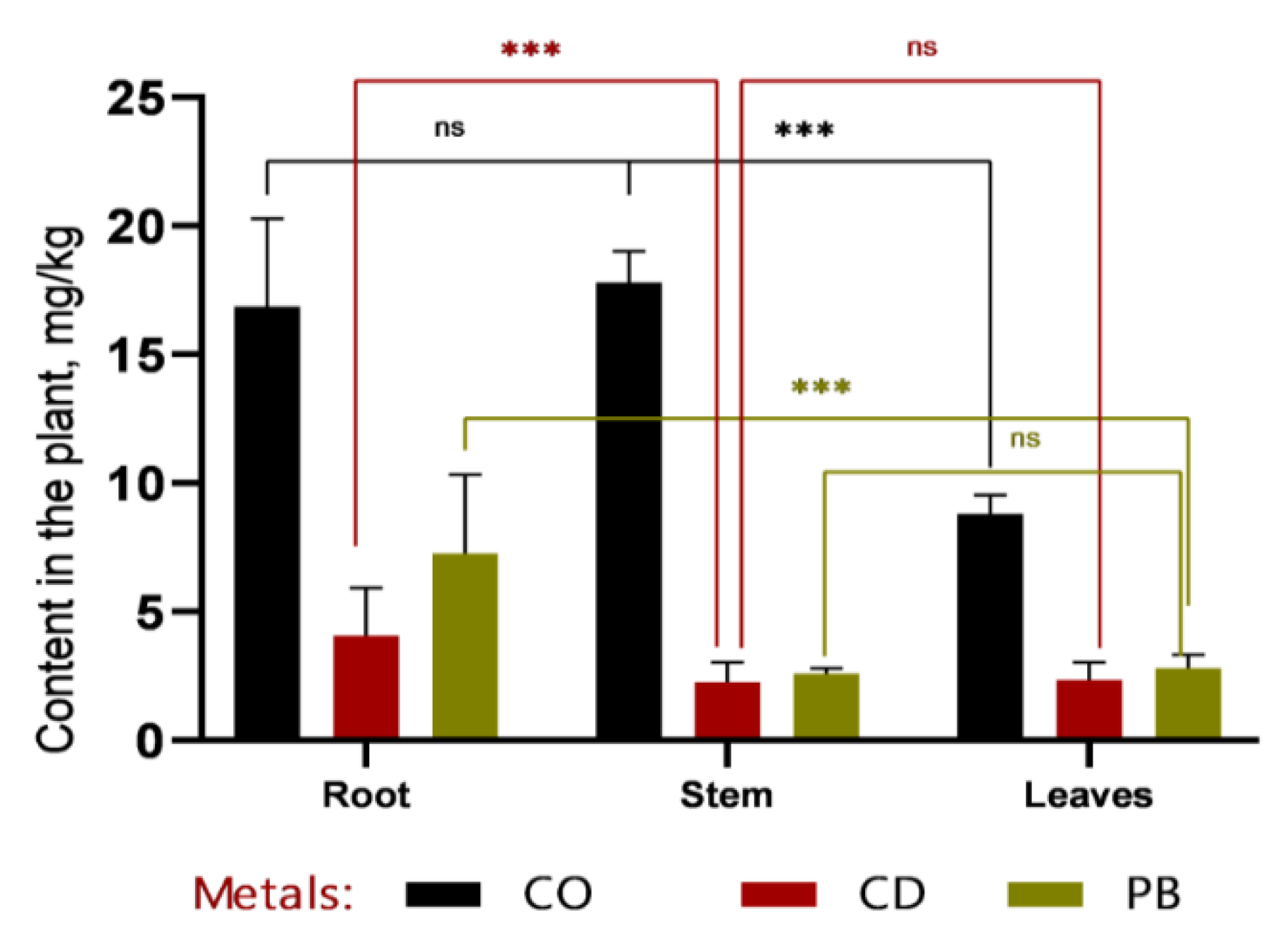

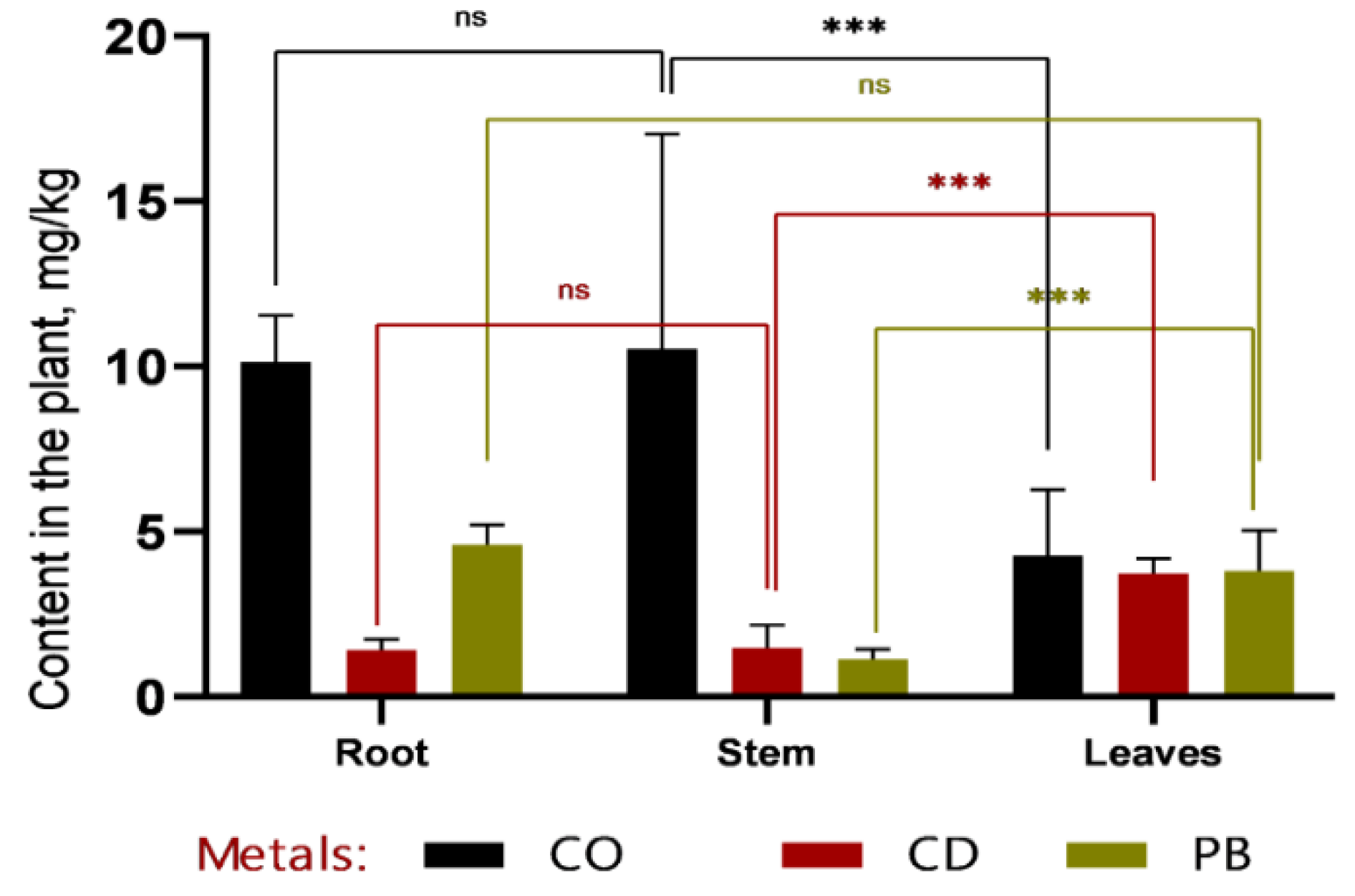

3.2. Comparative Analysis of Heavy Metal Accumulation in Sorghum Tissues and Soil

In the phytoremediation experiment employing Sorghum bicolor L. for the removal of heavy metals (Pb, Cd, Co) from contaminated soil, data were obtained on metal accumulation in plant tissues and concurrent changes in soil metal concentrations (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

Based on the data presented in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, it can be concluded that, within the first 30 days of vegetation, the primary accumulation of heavy metals (Co, Cd, and Pb) occurred in the roots, indicating a high rate of metal uptake from soil to roots. Efficient translocation from roots to stems is particularly important for phytoremediation, as it enables the sequestration of heavy metals in easily harvestable aboveground biomass—specifically, stems. The highest cobalt concentrations were recorded in roots (12.7 ± 1.32 mg/kg at 1 MAC and 16.87 ± 2.78 mg/kg at 2 MAC), accounting for more than 50% of the total Co content in the plant. A similar pattern was observed for cadmium, with 49% of its total accumulation localized in roots, further confirming the high efficiency of metal uptake from soil. Plumbum accumulation in roots constituted 53% of the total Pb content in the plant.

Analysis of heavy metal concentrations 60 days after emergence revealed that, in all samples except for cobalt (Co at 1 MAC) and plumbum (Pb at 1 MAC), metal levels in stems remained within permissible limits.

The investigation of heavy metal accumulation dynamics across different plant organs yielded significant findings that can inform both quantitative and qualitative assessments of phytoremediation efficacy. Clear patterns of metal partitioning among roots, stems, and leaves were established, providing valuable insights for optimizing soil remediation strategies targeting specific contaminants.

According to the data presented in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, cobalt (Co) exhibits distinct accumulation patterns across plant tissues. At the 1 MAC (maximum allowable concentration) level, Co is predominantly localized in leaves (8.8 mg/kg), with markedly lower concentrations in stems and roots. This suggests a high capacity of sweet sorghum to translocate and sequester cobalt in photosynthetically active tissues.

Similarly, plumbum (Pb) shows elevated concentrations in leaves compared to roots and stems, particularly at the 2 MAC level (5.7 ± 1.20 mg/kg in leaves, 4.8 ± 0.86 mg/kg in roots, and 3.5 ± 0.75 mg/kg in stems). This pattern indicates efficient root-to-shoot translocation of Pb, underscoring the potential of Sorghum bicolor L. for phytoextraction-based phytoremediation strategies.

In contrast, cadmium (Cd) concentrations remain consistently low across all plant organs and do not reach levels comparable to those of Co or Pb. This may reflect either lower bioavailability of Cd in the tested soil or limited physiological capacity of sorghum to absorb and translocate this metal, suggesting a more restricted role for this species in Cd-specific remediation contexts.

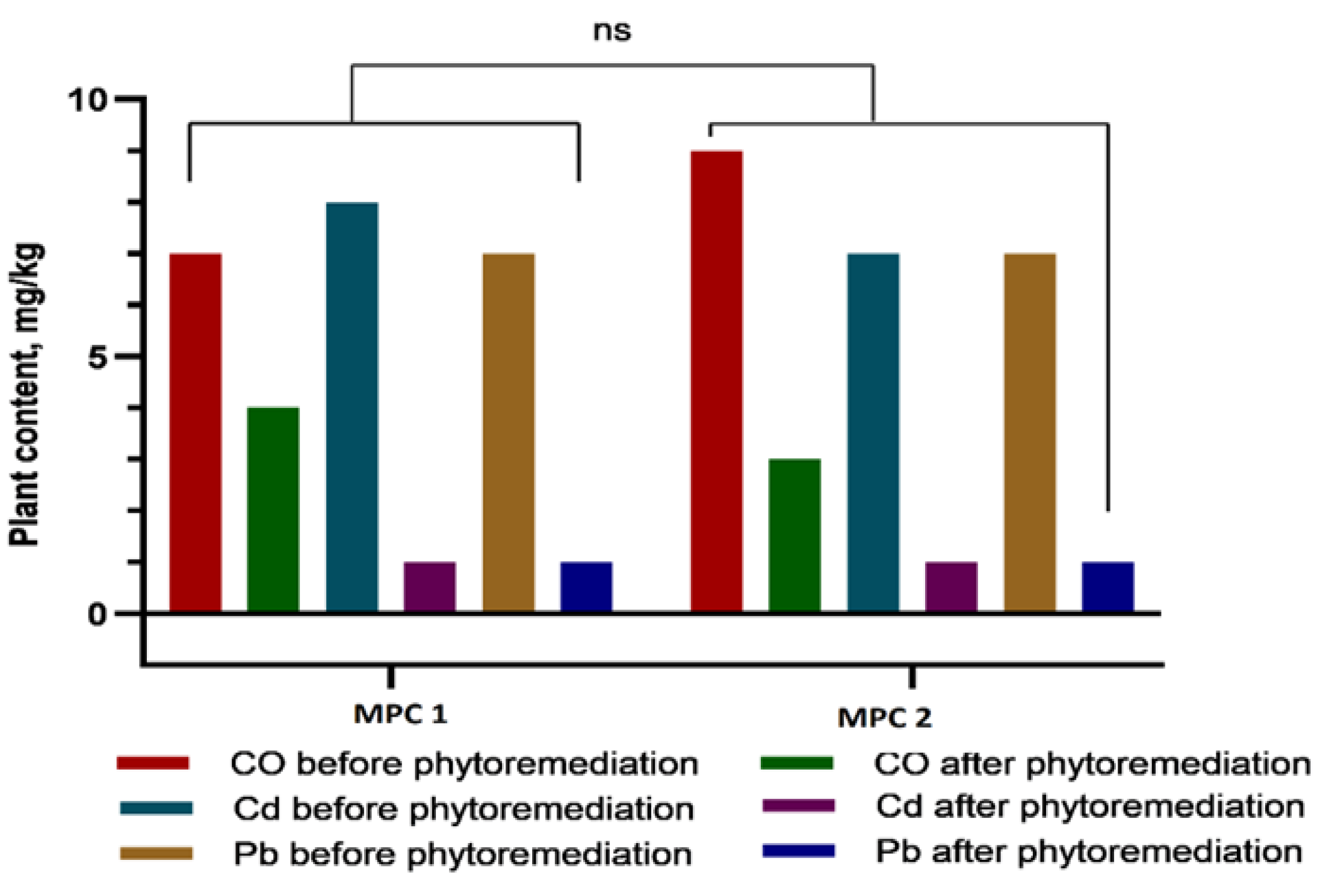

Soil analysis data (

Figure 7) further demonstrate that Sorghum bicolor L. exhibits high tolerance to elevated soil concentrations of heavy metals, both after 30 and 60 days of the vegetative period. This indicates a robust capacity of the species to acclimate to contaminated environments and maintain normal growth and physiological functions despite the presence of toxic elements, reinforcing its suitability for phytoremediation applications in metal-polluted soils.

3. Discussion

Sorghum bicolor L. is a highly adaptive crop that combines valuable agronomic and ecological traits: rapid growth, high biomass productivity, tolerance to abiotic stresses, and a notable capacity for heavy metal accumulation. Owing to these characteristics, it is increasingly regarded as a promising candidate for phytoremediation of contaminated soils, with the added benefit of utilizing the harvested biomass for biofuel production [

34].

Numerous studies [

35,

36] have demonstrated that Sorghum bicolor L. exhibits superior efficiency in heavy metal uptake compared to conventional cereal crops such as wheat and maize. This advantage is attributed to its extensive root system and its physiological ability to transform and translocate contaminants. Critically, sorghum maintains vigorous growth and development even in metal-contaminated soils, highlighting its potential for environmentally sustainable land reclamation and restoration strategies.

Our findings align closely with recent research [

37] on the use of different sorghum varieties for phytoremediation of heavy metal–polluted soils. Notably, genotypic differences significantly influence cadmium accumulation: energy sorghum cultivars have been shown to extract substantially more Cd from soil than sweet sorghum. This effect has been linked not only to morphological traits but also to total biomass production, which directly determines a plant’s phytoremediation potential. A similar trend was observed in our study, where pronounced accumulation of heavy metals was recorded in vegetative tissues—further validating the practical relevance of this approach.

Moreover, data from other studies [

38] emphasize the dominant role of the root system in plumbum sequestration: the bioconcentration factor (BCF) for Pb often exceeds 1, while its translocation to aboveground parts remains limited. Our results fully corroborate these observations, confirming that roots act as the primary barrier and “filter” for Pb and other heavy metals. This mechanism constitutes a key component of plant adaptive strategies and provides a foundation for designing effective phytoremediation technologies. Importantly, it also enables the safe utilization of aboveground sorghum biomass for contaminant removal through harvest and subsequent disposal or valorization.

Chemical analysis of soil-extractable (mobile) metal fractions before and after the vegetative cycle revealed a marked reduction in pollutant concentrations, particularly in treatments with a 60-day growth period. This indicates a genuine capacity of Sorghum bicolor L. to extract heavy metals from soil and supports its dual role in both phytoextraction and the initial phase of phytostabilization.

In summary, our experimental data, in conjunction with existing literature, confirm that sorghum is an effective and versatile species for the remediation of contaminated soils. Its phytoremediation potential is shaped by an interplay of varietal traits and cultivation conditions, positioning Sorghum bicolor L. as a high-priority subject for further research and practical implementation in sustainable soil restoration programs.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Development of a High-Productivity Genotype of Sweet Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L.)

The study focused on sweet sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L.), a promising crop characterized by high biomass yield, resilience to adverse environmental conditions, and a demonstrated capacity for heavy metal accumulation—traits that render it highly valuable for phytoremediation applications.

Immature embryos from diverse Sorghum bicolor L. genotypes were used as explants for in vitro somatic cell culture. The protocol for explant isolation, surface sterilization, and culture medium composition was adapted from established plant tissue culture methodologies [

39,

40]. Callus induction was carried out on a modified Murashige and Skoog (MS) basal medium supplemented with 2 mg/L 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D), 20 g/L sucrose, and 100 mg/L myo-inositol, adjusted to pH 5.7. Cultures were maintained under controlled conditions at 27 ± 1 °C in the dark for 30–60 days.

Explant sterilization involved sequential treatment with 70% ethanol, 50% sodium hypochlorite solution, and 3% hydrogen peroxide, as well as optimized combinations of these agents to maximize decontamination efficiency while preserving tissue viability.

To evaluate genotype productivity, a comprehensive assessment of agronomic and morphological traits was conducted at full maturity. Agronomic parameters included grain yield, seed weight, seed germination rate, and total biological productivity. Morphological characteristics encompassed plant height, panicle length and weight, and visual assessment of root system development.

The laboratory phase of genotype development was carried out at the Center for Biotechnology of the Satbayev University (Kazakh National Research Technical University). Field trials and phenotypic evaluation of promising lines were conducted under the agroecological conditions of southeastern Kazakhstan at the experimental plots of the Institute of Agriculture and Crop Production. This integrated laboratory–field approach enabled a robust evaluation of the adaptive potential and abiotic stress tolerance of the selected genotypes.

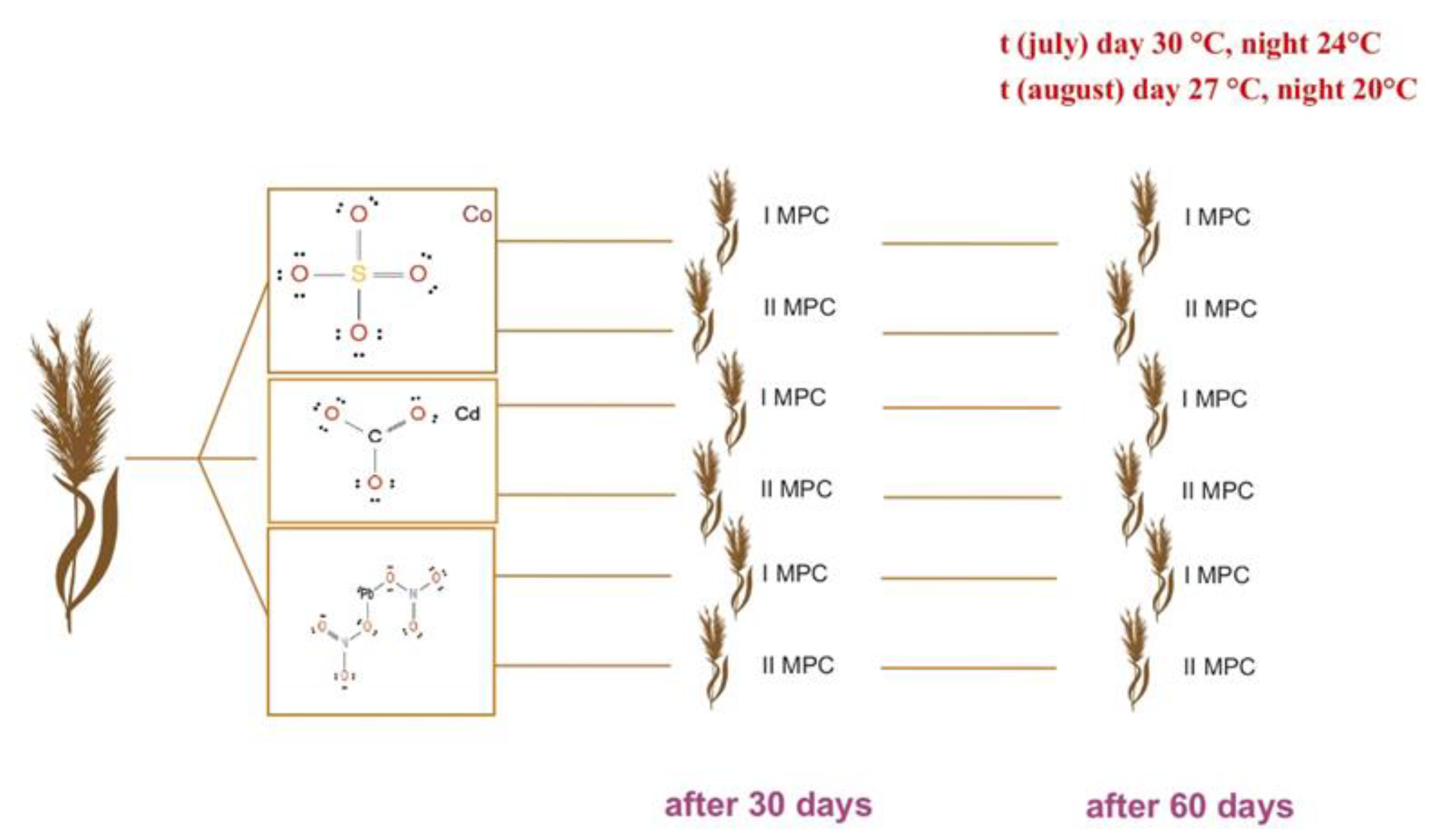

4.2. Laboratory-Scale Model Experiment on Phytoremediation of Heavy Metal–Contaminated Soils

To assess the phytoremediation potential of sweet sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L.), a controlled model experiment was conducted under laboratory conditions during the summer period. Average daily temperatures were maintained at 30 °C (day) / 24 °C (night) in July and 27 °C (day) / 20 °C (night) in August.

Air-dried chernozem soil was used as the growth substrate. The soil was sieved, ground, and thoroughly homogenized to ensure uniform texture and composition. Two kilograms of prepared soil were placed into individual pots.

The experimental design included two groups: (1) a treatment group with soil artificially contaminated with heavy metal salts, and (2) a control group with uncontaminated soil. Contamination was achieved by adding aqueous solutions of plumbum nitrate (Pb(NO₃)₂), cobalt sulfate (CoSO₄), and cadmium carbonate (CdCO₃). Each salt was dissolved in distilled water and uniformly applied to the soil to reach target contamination levels corresponding to 1× and 2× the maximum allowable concentration (MAC, or ПДК in Russian). The soil was thoroughly mixed to ensure homogeneous distribution of contaminants. Control pots received identical soil and irrigation regimes but without any added pollutants (

Figure 8).

Five seeds of sweet sorghum were sown per pot. All plants, in both control and treatment groups, received identical irrigation—daily watering to field capacity—to eliminate the confounding effects of water stress on growth and development.

Soil and plant sampling was carried out at two key vegetative stages: on day 30 and day 60. Harvested plants were separated into morphological components—roots, stems, and leaves. Samples were thoroughly rinsed with tap water to remove adhering soil particles, air-dried at room temperature to constant weight, and stored in parchment paper envelopes for subsequent analysis.

Concentrations of heavy metals (Pb, Cd, Co) in both soil and plant tissues were determined at the laboratory of LLP “Kazakh Scientific Research Institute of Soil Science and Agrochemistry named after U.U. Uspanov.”

The inclusion of an uncontaminated control group enabled an objective comparison of the effects of heavy metal exposure on the growth and development of sweet sorghum under otherwise identical cultivation conditions.

4.3. Determination of Heavy Metal Content in Soil and Plant Tissues

Concentrations of plumbum (Pb), cadmium (Cd), and cobalt (Co) were quantified using atomic absorption spectrometry (AAS) with a Shimadzu AA-7000 spectrophotometer (Japan). Soil sample preparation followed ISO 11466:1995 [

41]: samples were digested in a 3:1 (v/v) mixture of nitric and hydrochloric acids, heated to complete dissolution, filtered, and diluted to a defined volume. Plant material (roots, stems, leaves) was processed according to ISO 11047:1998 [

42]: after drying and grinding, samples underwent wet digestion using concentrated HNO₃ and H₂O₂, followed by filtration and dilution with distilled water.

Measurements were performed in an air–acetylene flame at the following wavelengths: Pb – 283.3 nm, Cd – 228.8 nm, and Co – 240.7 nm.

4.4. Statistical Data Analysis

All experimental data were statistically analyzed using GraphPad Prism software, version 8.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, California, USA). Heavy metal accumulation in different plant organs was expressed as mean values ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Differences in metal accumulation between sampling time points or plant parts were assessed using Student’s t-test. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

5. Conclusions

Among the evaluated sweet sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L.) genotypes, Hybrid-2 emerged as the most promising. It exhibited the highest frequency of callus induction and a robust capacity for morphogenesis. Coupled with its strong stress tolerance and well-developed root system, Hybrid-2 represents a prime candidate for phytoremediation of heavy metal–contaminated soils and for further biotechnological applications.

Under field conditions in southeastern Kazakhstan, we also identified disease- and stress-resistant genotypes that maintain high productivity even under arid climatic conditions. Their vigorous root architecture and environmental adaptability render these lines particularly valuable for phytoremediation purposes.

The results of this study provide compelling evidence of the high phytoremediation potential of sweet sorghum for soils contaminated with heavy metals. As early as 30 days into the vegetative period, the root system functioned as the primary accumulator of contaminants, sequestering up to 53% of plumbum (Pb), 49% of cadmium (Cd), and over 50% of cobalt (Co). This confirms the critical role of roots as a natural “filter,” effectively limiting metal translocation to aboveground tissues.

By day 60, partial translocation of heavy metals to shoots became evident: cobalt concentrations reached 8.8 mg/kg in leaves at the 1 MAC contamination level, while plumbum accumulated up to 5.7 mg/kg in leaves at 2 MAC. These findings demonstrate sorghum’s ability to mobilize substantial quantities of pollutants into photosynthetically active organs—a key requirement for efficient phytoextraction.

A direct comparison of metal concentrations before and after phytoremediation revealed a pronounced remediation effect: Cd and Pb levels decreased by 70–80%, while Co content was reduced by nearly half. Notably, no significant differences were observed between the 1 MAC and 2 MAC contamination levels, underscoring the robustness and reproducibility of the remediation process across varying pollution intensities.

Overall, Sorghum bicolor L. demonstrated remarkable adaptability and tolerance to contaminated environments, sustaining normal growth and development even in the presence of elevated soil concentrations of Pb, Cd, and Co. These findings support the dual utility of sweet sorghum—not only as a high-value bioenergy crop but also as an effective, sustainable tool for the restoration of heavy metal–polluted and degraded lands.6. Patents

This section is not mandatory but may be added if there are patents resulting from the work reported in this manuscript.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Table 1. Callus induction in in vitro somatic cell cultures of sweet sorghum (

Sorghum bicolor L.); Table 2. Frequency of morphogenic callus formation in in vitro somatic cell cultures of sweet sorghum (

Sorghum bicolor L.);

Figure 1 – Friable, non-morphogenic calli obtained from in vitro somatic cell culture of sweet sorghum (

Sorghum bicolor L.);

Figure 2. Morphogenic calli obtained from in vitro somatic cell cultures of sweet sorghum (

Sorghum bicolor L.);

Figure 3. Comparative distribution of heavy metals (Co, Cd, and Pb) in roots, stems, and leaves of Sorghum bicolor L. after 30 days of the vegetative period;

Figure 4. Comparative distribution of heavy metals (Co, Cd, and Pb) in plant organs after 30 days of the vegetative period;

Figure 5. Concentrations of heavy metals (Co, Cd, and Pb) in roots, stems, and leaves of Sorghum bicolor L. after 60 days of the vegetative period;

Figure 6. Distribution of heavy metals in sorghum organs after 60 days of the vegetative period;

Figure 7. Concentrations of heavy metals (Co, Cd, and Pb) in Sorghum bicolor L. plants before and after phytoremediation in two experimental treatments (1 MAC and 2 MAC);

Figure 8. Experimental design: sorghum plants were grown under two levels of heavy metal contamination (1× and 2× MAC) and sampled at 30 and 60 days after sowing.

Author Contributions

S.A. and A.B., together with T.N., conceived and designed the study. S.A., O.B., and I.K. performed the experiments. S.A. and S.G. carried out the heavy metal analyses using atomic absorption spectrometry and interpreted the resulting data. A.E., .A., and N.S. contributed to the analysis of supplementary data. S.A. wrote the original draft of the manuscript. A.N. (Nurika Assanzhanova) and A.B. reviewed and edited the manuscript. A.B. supervised the research project, and A.N. ( Nurlan Akmyrzayev) was responsible for data processing. All authors have read and approved the final published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AAS |

Atomic absorption spectroscopy |

| MPC |

Maximum Permissible Concentration |

| As |

Arsenic |

| Cd |

Cadmium |

| Cr |

Chromium |

| Hg |

Mercury |

| Cu |

Copper |

| Pb |

Рlumbum |

| Ni |

Nickel |

| Zn |

Zinc |

| MAC |

Maximum allowable concentration |

| MS |

Murashige and Skoog |

References

- Bhunia, P. Environmental toxicants and hazardous contaminants: Recent advances in technologies for sustainable development. Journal of Hazardous, Toxic, and Radioactive Waste 2017, 21, 02017001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, A. K. , & Nagan, S. (2015). Bioremediation of dye effluent and metal contaminated soil: Low-cost method for environmental clean up by microbes. Journal of Environmental Science and Engineering 2015, 57, 109–119. [Google Scholar]

- Alengebawy, A. , Abdelkhalek, S. T., Qureshi, S. R., & Wang, M.-Q. (2021). Heavy metals and pesticides toxicity in agricultural soil and plants: Ecological risks and human health implications. Toxics 2021, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kapoor, D. , & Singh, M. P. (2021). Heavy metal contamination in water and its possible sources. In Heavy metals in the environment 2021, (pp. 179–189). Elsevier.

- Jabeen, R. , Ahmad, A., & Iqbal, M. (2009). Phytoremediation of heavy metals: Physiological and molecular mechanisms. Botanical Review 2009, 75, 339–364. [Google Scholar]

- Berglund, M. , Larsson, K., Grandér, M., Casteleyn, L., Kolossa-Gehring, M., Schwedler, G., et al. Exposure determinants of cadmium in European mothers and their children. Environmental Research 2015, 141, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dada, E. O. , Njoku, K. I., Osuntoki, A. A., & Akinola, M. O. A review of current techniques of physico-chemical and biological remediation of heavy metals polluted soil. Ethiopian Journal of Environmental Studies and Management 2015, 8, 606–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, R. , Wasiullah, M. D., Pandiyan, K., Singh, U. B., Sahu, A., Shukla, R., Singh, B. P., Rai, J. P., Sharma, P. K., Lade, H., & Paul, D. Bioremediation of heavy metals from soil and aquatic environment: An overview of principles and criteria of fundamental processes. Sustainability 2015, 7, 2189–2212. [Google Scholar]

- Sarwar, N. , Imran, M., Shaheen, M. R., Ishaq, W., Kamran, A., Matloob, A., Rehim, A., & Hussain, S. Phytoremediation strategies for soils contaminated with heavy metals: Modifications and future perspectives. Chemosphere 2017, 171, 710–721. [Google Scholar]

- Maszenan, A. M. , Liu, Y., & Ng, W. J. Bioremediation of wastewaters with r. ecalcitrant organic compounds and metals by aerobic granules. Biotechnology Advances 2011, 29, 111–123. [Google Scholar]

- Stearns, J. C. , Shah, S., & Glick, B. R. Increasing plant tolerance to metals in the environment. In N. Willey (Ed.), Phytoremediation: Methods and Reviews 2006, (pp. 15–26). Humana Press.

- Verma, R.K. , Awasthi, K., Sankhla, M.S., Jadhav, E.B. and Parihar, K. Phytoremediation of Heavy Metals Extracted from Soil and Aquatic Environments: Current Advances as Well as Emerging Trends. Biointerface Research in Applied Chemistry 2022, 12, 5486–5509. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, J. K.; Kumar, N.; Singh, N. P.; Santal, A. R. Phytoremediation Technologies and Their Mechanism for Removal of Heavy Metal from Contaminated Soil: An Approach for a Sustainable Environment. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1076876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, A. J. M. , & Brooks, R. R. Terrestrial higher plants which hyperaccumulate metal elements—A review of their distribution, ecology and phytochemistry. Biorecovery 1989, 1, 81–126. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, H. , Khan, E., & Sajad, M. A. Phytoremediation of heavy metals—Concepts and applications. Chemosphere 2013, 91, 869–881. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra, R. , Saxena, G., & Kumar, V. Phytoremediation of environmental pollutants: An eco-sustainable green technology to environmental management. In R. Chandra (Ed.), Advances in biodegradation and bioremediation of industrial waste 2015, pp. 1–30. CRC Press.

- Mahar, A. , Wang, P., Ali, A., Awasthi, M. K., Lahori, A. H., Wang, Q., Li, R., & Zhang, Z. Challenges and opportunities in the phytoremediation of heavy metals contaminated soils: A review. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2016, 126, 111–121. [Google Scholar]

- Muthusaravanan, S. , Sivarajasekar, N., Vivek, J. S., Paramasivan, T., Naushad, M., Prakashmaran, J., Gayathri, V., & Al-Duaij, O. K. Phytoremediation of heavy metals: Mechanisms, methods and enhancements. Environmental Chemistry Letters 2018, 16, 1339–1359. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, K. , Li, T., Cheng, H., Xie, Y., & Yonemochi, S. Study on tolerance and accumulation potential of bio-fuel crops for phytoremediation of heavy metals. International Journal of Environmental Science and Development 2013, 4, 152–156. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, K. , Cao, T., Li, T., & Cheng, H. Study on application of phytoremediation technology in management and remediation of contaminated soils. Journal of Clean Energy Technologies 2014, 2, 216–220. [Google Scholar]

- Zaynutdinova, E. M. , Yagafarova, G. G., Shamsudinova, E. A., & Mazitova, A. K. Phytoremediation of Technogenically Disturbed Areas. Bulletin of Kazan Technological University, 2017; 157–159. [Google Scholar]

- Elekes, C. C. Eco-technological solutions for the remediation of polluted soil and heavy metal recovery. In M. C. Hernández-Soriano (Ed.), Environmental risk assessment of soil contamination 2014, (pp. 309–335). InTech.

- Lin, H. , Wang, Z., Liu, C., & Dong, Y. (2022). Technologies for removing heavy metal from contaminated soils on farmland: A review. Chemosphere 2022, 305, 135457. [Google Scholar]

- Noor, I. , Sohail, H., Sun, J., Nawaz, M. A., Li, G., Hasanuzzaman, M., & Liu, J. Heavy metal and metalloid toxicity in horticultural plants: Tolerance mechanism and remediation strategies. Chemosphere 2022, 303, 135196. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, P. , & Mathur, J. Phytoremediation efficiency of Helianthus annuus L. for reclamation of heavy metals-contaminated industrial soil. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2020, 27, 29954–29966. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, J. , et al. Phytoremediation potential of wheat intercropped with different densities of Sedum plumbizincicola in soil contaminated with cadmium and zinc. Chemosphere 2021, 276, 130223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W. , et al. Strengthening role and the mechanism of optimum nitrogen addition in relation to Solanum nigrum L. Cd hyperaccumulation in soil. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2019, 182, 109444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, X. , Xiong, T., Yao, S., Liu, C., Yin, Y., Li, H., & Li, N. A real field phytoremediation of multi-metals contaminated soils by selected hybrid sweet sorghum with high biomass and high accumulation ability. Chemosphere 2019, 237, 124536. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, J. , Verma, R. K., & Singh, S. Suitability of aromatic plants for phytoremediation of heavy metal contaminated areas: A review. International Journal of Phytoremediation 2019, 21, 405–418. [Google Scholar]

- Sheoran, V. , Sheoran, A. S., & Poonia, P. Factors affecting phytoextraction: A review. Pedosphere 2016, 26, 148–166. [Google Scholar]

- Salifu, M. , John, M., Abubakar, M., Bankole, I., Ajayi, N., & Amusan, O. Phytoremediation strategies for heavy metal contamination: A review on sustainable approach for environmental restoration. Journal of Environmental Protection 2024, 15, 450–474. [Google Scholar]

- Anapiyaev, B. B. , Iskakova, K. M., Beisenbek, E. B., Kapalova, S. K., Sagimbayeva, A. M., & Omarova, A. Sh. Features of Sorghum bicolor L. Resistance to Biotic Stress Factors under Arid Conditions of Southeastern Kazakhstan. Agrarian Science 2019, (S1), 166–170. [Google Scholar]

- Sagimbayeva, A. M. Selection of Highly Productive Genotypes of Sweet Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L.) for Further Use in Phytoremediation of Soils Contaminated with Heavy Metals. Biosafety and Biotechnology 2022, (11), 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Soudek, P. , Petrová, Š. , Vaňková, R., Song, J., & Vaněk, T. Accumulation of heavy metals using Sorghum sp. Chemosphere 2014, 104, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. , Chen, C., & Wang, J. Phytoremediation of strontium contaminated soil by Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench and soil microbial community-level physiological profiles (CLPPs). Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2017, 24, 7668–7678. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Di Giuseppe, D. , Melchiorre, M., Bianchini, G., & Vaněk, T. Assessment of heavy metal bioaccumulation in sorghum from neutral saline soils in the Po River Delta Plain (Northern Italy). Environmental Earth Sciences 2017, 76, 519. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Luo, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Chen, W. Energy Sorghum Removal of Soil Cadmium in Chinese Subtropical Farmland: Effects of Variety and Cropping System. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, H. E. , Fadhlallah, R. S., Alamoudi, W. M., Eid, E. M., & Abdelhafez, A. A. Phytoremediation potential of sorghum as a bioenergy crop in Pb-amendment soil. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2178. [Google Scholar]

- Murashige, T. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Plant Physiology 1962, 15, 473–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, E.F.; Hall, M.A.; de Klerk, G.J. Plant Propagation by Tissue Culture. Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands 2008, p. 401.

- ISO 11466:1995; International Organization for Standardization. ISO 11466:1995—Soil Quality—Extraction of Trace Elements Soluble in Aqua Regia; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 11047:1998; International Organization for Standardization. ISO 11047:1998—Soil Quality—Determination of Cadmium, Chromium, Cobalt, Copper, Lead, Manganese, Nickel and Zinc—Flame and Electrothermal Atomic Absorption Spectrometric Methods; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1998. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Friable, non-morphogenic calli obtained from in vitro somatic cell culture of sweet sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L.).

Figure 1.

Friable, non-morphogenic calli obtained from in vitro somatic cell culture of sweet sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L.).

Figure 2.

Morphogenic calli obtained from in vitro somatic cell cultures of sweet sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L.).

Figure 2.

Morphogenic calli obtained from in vitro somatic cell cultures of sweet sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L.).

Figure 3.

Comparative distribution of heavy metals (Co, Cd, and Pb) in roots, stems, and leaves of Sorghum bicolor L. after 30 days of the vegetative period. The highest concentration of cobalt was observed in the roots (approximately 15 mg/kg), which was significantly higher than in stems and leaves (***p < 0.001). Cadmium and plumbum levels remained low and showed no statistically significant differences among plant organs (ns, *p* > 0.05). Overall, metal concentrations decreased from roots to leaves, with the most pronounced gradient observed for cobalt.

Figure 3.

Comparative distribution of heavy metals (Co, Cd, and Pb) in roots, stems, and leaves of Sorghum bicolor L. after 30 days of the vegetative period. The highest concentration of cobalt was observed in the roots (approximately 15 mg/kg), which was significantly higher than in stems and leaves (***p < 0.001). Cadmium and plumbum levels remained low and showed no statistically significant differences among plant organs (ns, *p* > 0.05). Overall, metal concentrations decreased from roots to leaves, with the most pronounced gradient observed for cobalt.

Figure 4.

Comparative distribution of heavy metals (Co, Cd, and Pb) in plant organs after 30 days of the vegetative period. Cobalt predominantly accumulated in roots and stems, with lower concentrations detected in leaves. Cadmium was present only in trace amounts, showing no marked differences among organs. Plumbum was primarily retained in roots and leaves, whereas its concentration in stems remained low. Data are presented as mean values ± standard errors; *** denotes p < 0.0001, and “ns” indicates no statistically significant difference (*p* > 0.05).

Figure 4.

Comparative distribution of heavy metals (Co, Cd, and Pb) in plant organs after 30 days of the vegetative period. Cobalt predominantly accumulated in roots and stems, with lower concentrations detected in leaves. Cadmium was present only in trace amounts, showing no marked differences among organs. Plumbum was primarily retained in roots and leaves, whereas its concentration in stems remained low. Data are presented as mean values ± standard errors; *** denotes p < 0.0001, and “ns” indicates no statistically significant difference (*p* > 0.05).

Figure 5.

Concentrations of heavy metals (Co, Cd, and Pb) in roots, stems, and leaves of Sorghum bicolor L. after 60 days of the vegetative period. Cobalt (Co) accumulated predominantly in roots and stems, with significantly lower levels detected in leaves. Cadmium (Cd) was present in all plant organs at low concentrations, showing a slight tendency toward higher accumulation in leaves. Plumbum (Pb) was primarily localized in roots and leaves, while its concentration in stems remained minimal. Asterisks denote statistically significant differences between plant organs (*** p < 0.001); “ns” indicates no significant difference (*p* > 0.05).

Figure 5.

Concentrations of heavy metals (Co, Cd, and Pb) in roots, stems, and leaves of Sorghum bicolor L. after 60 days of the vegetative period. Cobalt (Co) accumulated predominantly in roots and stems, with significantly lower levels detected in leaves. Cadmium (Cd) was present in all plant organs at low concentrations, showing a slight tendency toward higher accumulation in leaves. Plumbum (Pb) was primarily localized in roots and leaves, while its concentration in stems remained minimal. Asterisks denote statistically significant differences between plant organs (*** p < 0.001); “ns” indicates no significant difference (*p* > 0.05).

Figure 6.

Distribution of heavy metals in sorghum organs after 60 days of the vegetative period. Cobalt accumulates primarily in roots and stems, plumbum is predominantly found in roots and leaves, while cadmium is present in all plant organs at low concentrations. Statistically significant differences were observed only for specific metals (*** p < 0.001; “ns” denotes non-significant differences, *p* > 0.05).

Figure 6.

Distribution of heavy metals in sorghum organs after 60 days of the vegetative period. Cobalt accumulates primarily in roots and stems, plumbum is predominantly found in roots and leaves, while cadmium is present in all plant organs at low concentrations. Statistically significant differences were observed only for specific metals (*** p < 0.001; “ns” denotes non-significant differences, *p* > 0.05).

Figure 7.

Concentrations of heavy metals (Co, Cd, and Pb) in Sorghum bicolor L. plants before and after phytoremediation in two experimental treatments (1 MAC and 2 MAC). Following phytoremediation, Cd and Pb concentrations decreased markedly—nearly to baseline levels—whereas Co content was reduced by approximately half. No statistically significant differences were observed between the 1 MAC and 2 MAC treatments (ns, p > 0.05).

Figure 7.

Concentrations of heavy metals (Co, Cd, and Pb) in Sorghum bicolor L. plants before and after phytoremediation in two experimental treatments (1 MAC and 2 MAC). Following phytoremediation, Cd and Pb concentrations decreased markedly—nearly to baseline levels—whereas Co content was reduced by approximately half. No statistically significant differences were observed between the 1 MAC and 2 MAC treatments (ns, p > 0.05).

Figure 8.

Experimental design: sorghum plants were grown under two levels of heavy metal contamination (1× and 2× MAC) and sampled at 30 and 60 days after sowing. The experiment was conducted under natural summer conditions—in July (30 °C day / 24 °C night) and August (27 °C day / 20 °C night).

Figure 8.

Experimental design: sorghum plants were grown under two levels of heavy metal contamination (1× and 2× MAC) and sampled at 30 and 60 days after sowing. The experiment was conducted under natural summer conditions—in July (30 °C day / 24 °C night) and August (27 °C day / 20 °C night).

Table 1.

Callus induction in in vitro somatic cell cultures of sweet sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L.).

Table 1.

Callus induction in in vitro somatic cell cultures of sweet sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L.).

| Genotype |

Number of isolated embryos |

Number of calli formed |

Callus induction rate (%) |

| SABB-1 |

52 |

22 |

42,31 |

| SAB-2 |

67 |

3 |

4,47 |

| SAB-3 |

73 |

32 |

43,83 |

| SAB-10 |

62 |

25 |

40,32 |

| SAB-11 |

79 |

29 |

36,70 |

| Hybrid-1 |

75 |

19 |

25,33 |

| Hybrid-2 |

68 |

47 |

69,11 |

Table 2.

Frequency of morphogenic callus formation in in vitro somatic cell cultures of sweet sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L.).

Table 2.

Frequency of morphogenic callus formation in in vitro somatic cell cultures of sweet sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L.).

| Genotype |

Number of isolated embryos |

Number of calli formed |

Callus induction rate (%) |

| SABB-1 |

52 |

9 |

2,99 |

| SAB-2 |

67 |

0 |

0 |

| SAB-3 |

73 |

17 |

23,28 |

| SAB-10 |

62 |

8 |

12,90 |

| SAB-11 |

79 |

6 |

7,59 |

| Hybrid-1 |

75 |

12 |

16,0 |

| Hybrid-2 |

68 |

19 |

27,94 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).