1. Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the leading causes of death worldwide, predominantly affecting women, with an estimated 2.3 million cases and 685,000 deaths reported in 2020 [

1]. Although the incidence of breast cancer in African countries classified as low-middle-income countries (LMICs) is reported to be lower than in high-income countries (HICs), mortality rates are disproportionately high due to underdiagnosis, limited screening, and poor healthcare infrastructure [

2]. In 2020, Africa reported approximately 186,598 new cases and 85,78 7 deaths due to breast cancer [

3]. Among the African countries, South Africa appears to have the highest prevalence rates of breast cancer, with reported 110,000 new cases and over 56,000 deaths in a single year [

4]. Alarmingly, projections indicate that breast cancer cases across Africa could double by 2050, highlighting the urgent need for robust public health interventions [

3,

5].

Genetic predisposition plays a significant role in breast cancer risk. The presence of a mutation in breast cancer genes 1 or 2 (BRCA1 and BRCA2) is strongly related to hereditary breast cancer. These genes encode proteins responsible for DNA repair, and their dysfunction due to mutations can lead to genomic instability and increased cancer susceptibility [

6,

7]. Literature has reported that approximately 15–10% of breast cancer cases are associated with a family history of the disease [

8]. Worth noting, most research on BRCA mutations has focused on developed countries, with limited data from regions such as Africa [

9,

10]. This underrepresentation, especially in black African populations, emphasizes the urgent need for inclusive genetic studies. Furthermore, African countries, particularly South Africa, face a double burden of disease characterised by the high prevalence of infectious diseases such as HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis in conjunction with increasing rates of non-communicable diseases such as cancer [

11,

12]. This double burden strains healthcare systems, impacting the availability of resources for cancer prevention, screening, and treatment [

12]. As a result, breast cancer management is often delayed or inadequate, contributing to poorer outcomes for women diagnosed with the disease [

13,

14]. This narrative review aims to critically examine the barriers to early detection of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in breast cancer patients within African and other low-resource settings and to propose cost-effective, context-specific strategies for expanding genetic testing capacity to improve breast cancer prevention, early diagnosis, and management in resource-limited healthcare settings.

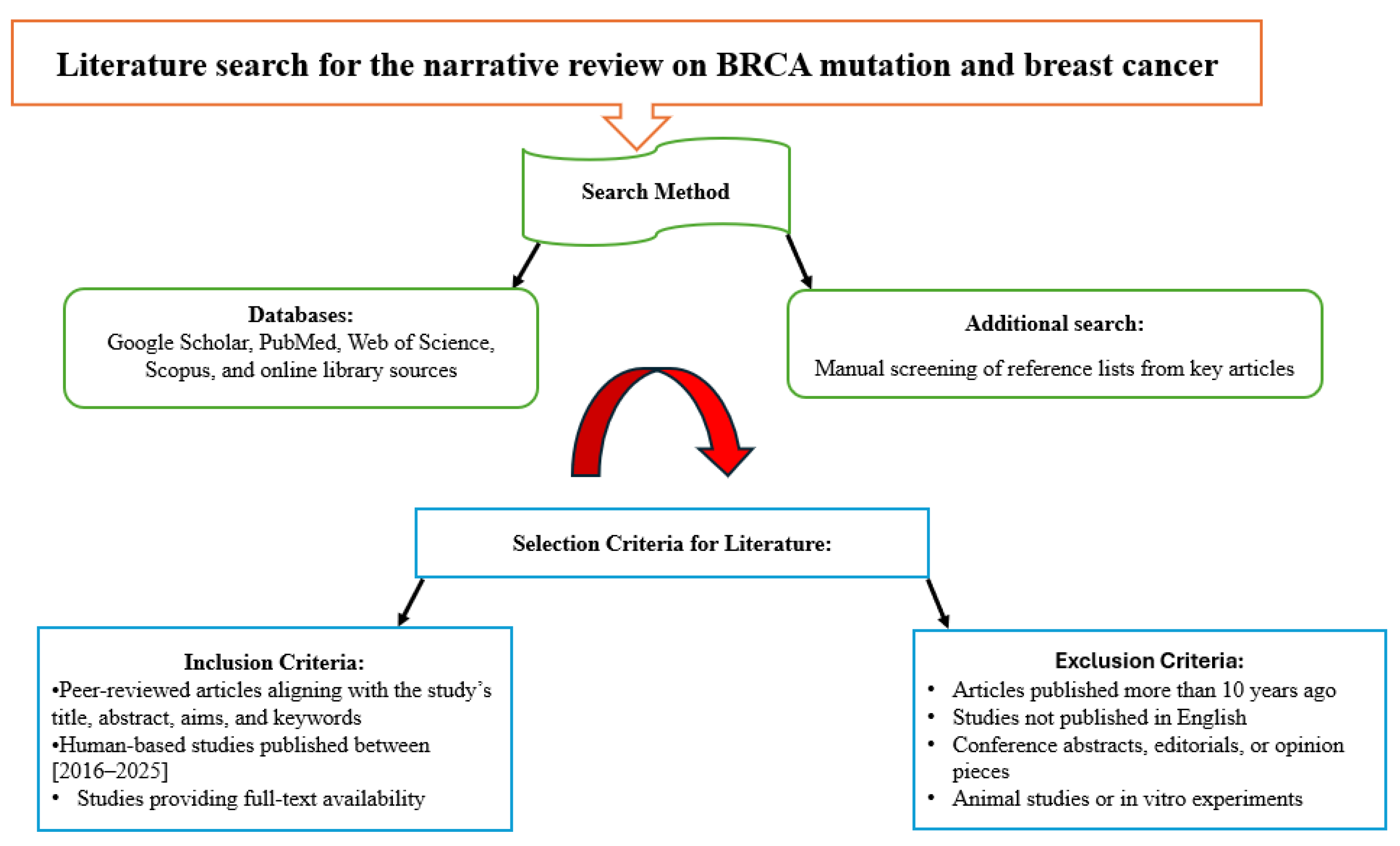

2. Literature Search for the Current Narrative Review Study

A comprehensive literature search was conducted to identify relevant studies for the current review, with the search methodology illustrated below in

Figure 1.

3. Pathogenic Mechanisms of BRCA1/2 Mutations and Cancer Development

Notably, BRCA1 and BRCA2 are two of the most extensively studied genes related to hereditary breast cancer and ovarian cancer [

6]. BRCA1 and BRCA2 proteins play a critical role in homologous recombination (HR), which is one of the most accurate pathways for repairing double-strand breaks in DNA. When these genes are mutated, the cell is unable to properly repair DNA damage, leading to genomic instability and accumulation of harmful mutations that can initiate and promote cancer development [

15]. In BRCA mutation carriers, the defect originates from a germline mutation that occurs in one allele of either BRCA1 or BRCA2, which is inherited. If the second copy of BRCA1/2 in a cell is later damaged by a somatic mutation or deletion, then both copies are lost. This results in a total loss of BRCA protein function, meaning the cell can no longer properly repair DNA breaks. As a result, this promotes genomic instability, increasing the likelihood of accumulating further mutations that drive cancer development [

6].

In addition to their role in DNA repair, BRCA1 and BRCA2 also associate with important cell-cycle mediators and apoptotic pathways. For example, BRCA1 is known to interact with the p53 tumour suppressor pathway, which regulates cell cycle control and apoptosis. When BRCA1 is mutated, this interaction is disrupted, weakening p53-mediated tumor suppression and allowing abnormal cells to survive and proliferate [

16].

Clinically, there are also phenotypical differences between the effects of BRCA mutations in cancer. BRCA1 mutations are frequently associated with triple-negative breast cancers (TNBCs), which are aggressive and lack estrogen, progesterone, and HER2 receptors, limiting treatment options [

17]. In contrast, BRCA2 mutations are more often linked to hormone receptor–positive breast cancers, expressing either estrogen or progesterone receptors; these cancers typically develop later in life compared with BRCA1-related cancers [

18]. Both BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations also increase the risk of ovarian, prostate, and pancreatic cancers [

19]. Importantly, the identification of BRCA mutations has guided the development of targeted therapies, particularly the use of PARP inhibitors, which exploit defective homologous recombination repair through synthetic lethality [

20].

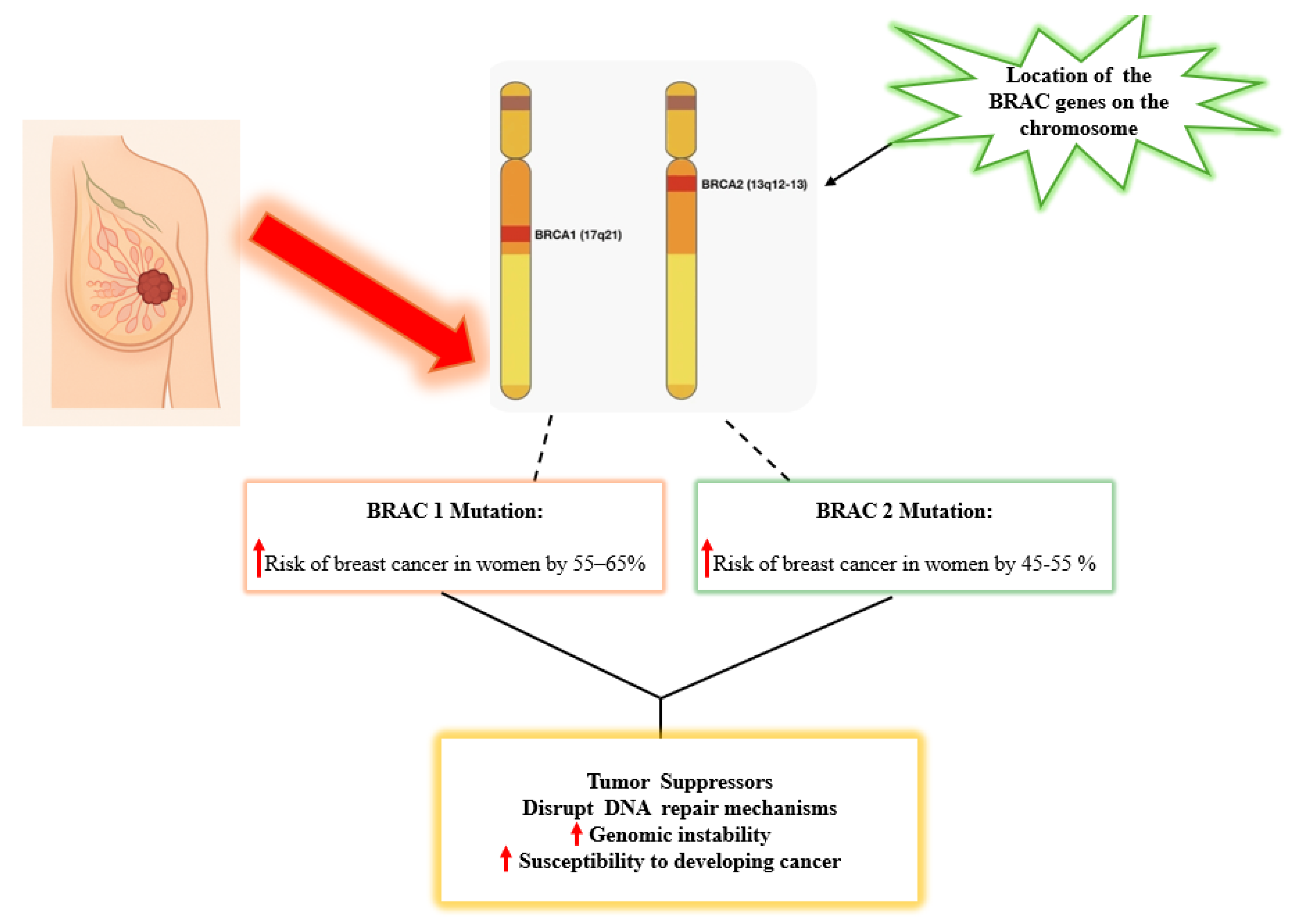

Genomic BRCA1 is located on chromosome 17q21 and encodes a protein that is involved in double-strand DNA break repair by homologous recombination, cell cycle checkpoint control, and transcriptional regulation [

21]. Women with a BRCA1 germline mutation have a 55-65% lifetime risk of developing breast cancer by age 70 [

6,

22]. BRCA2, on the other hand, is located on chromosome 13 at the 13q12.3 position and encodes a protein critical for homologous recombination repair. It assists in stabilizing and facilitating the repair process by aiding the loading of RAD51, a key protein in the Homologous Recombination Repair (HRR) pathway [

23]. Women who carry BRCA2 mutations have a 45–55% lifetime risk of developing breast cancer by age 70 [

19].

Ongoing research is crucial to deepen our understanding of how BRCA mutations contribute to breast cancer development, the effectiveness of targeted treatments, and the involvement of other genes in the BRCA-associated repair pathway. The link between BRCA mutations and breast cancer highlights the importance of identifying genetic risk factors to enhance prevention strategies, treatment options, and personalized care, especially in regions such as South Africa, where access to genetic testing and tailored therapies is limited. Expanding research and healthcare capacity in such regions can help bridge the gap, improving affordability, access, and ultimately patient outcomes.

Figure 2 illustrates the chromosomal locations of BRCA1 on chromosome 17 and BRCA2 on chromosome 13, highlighting how mutations in these genes increase the risk of breast cancer in women and contribute to genomic instability by disrupting DNA repair mechanisms.

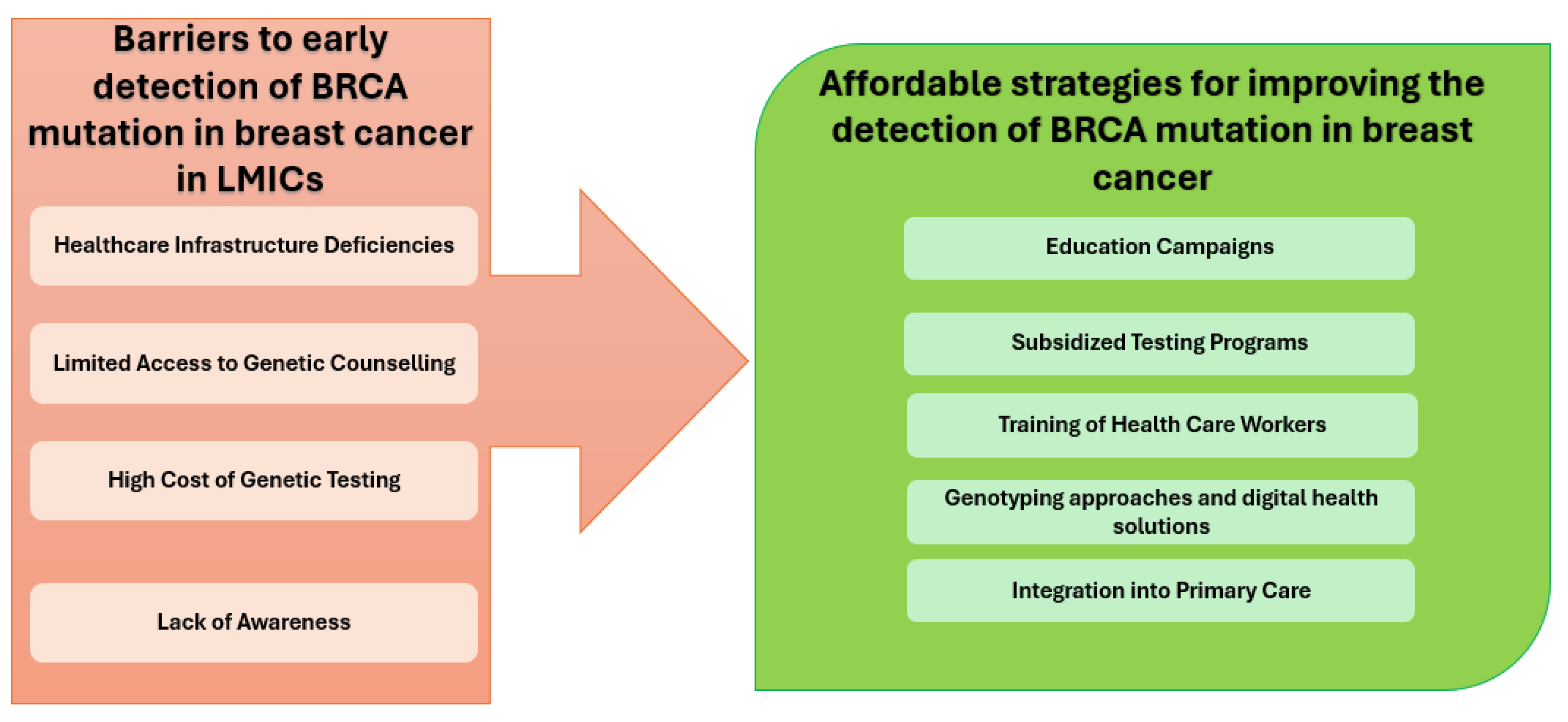

4. Barriers to Early Detection of BRCA Mutations in LMICs with a Focus on African Countries, Especially South Africa

Barriers to early detection of BRCA mutations in LMICs, particularly in African countries including South Africa, are multifaceted and include socioeconomic, healthcare system, awareness challenges, low referral, testing rates, technical and cost-effectiveness [

24]. These barriers not only delay diagnosis and appropriate risk stratification but also contribute to poorer outcomes in breast cancer patients across these regions [

25].

4.1. Socioeconomic and Financial Barriers

Socioeconomic status is a major contributor to health outcomes in LMICs, especially in access to genetic testing and preventive measures for hereditary cancers [

24]. In many LMICs, particularly in African countries, the financial burden associated with BRCA1 and BRCA2 testing presents a substantial barrier to the early detection and clinical management of hereditary breast cancer. The high cost of genetic testing remains a significant limitation, placing a substantial financial burden on both individuals and already strained national healthcare systems [

26]. Moreover, BRCA testing is often excluded from public health insurance schemes and essential diagnostic service packages, further limiting access for economically disadvantaged populations. Consequently, individuals must frequently self-fund these tests, exacerbating existing health inequities [

24,

27]. This challenge is particularly pronounced among those in the missing middle individuals who do not qualify for subsidized public healthcare due to slightly higher income levels, however, are unable to afford private insurance or specialist services [

28]. Without affordable access to genetic counselling and testing, many at-risk individuals remain undiagnosed, delaying preventive care and increasing the likelihood of late-stage cancer diagnoses [

24,

27].

4.2. Limited Awareness and Education

Limited awareness and insufficient education about hereditary breast cancer, particularly BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations, represent critical barriers to early detection and effective risk management in LMICs, especially across the African continent [

2,

25]. In the context of many African countries, both patients and healthcare providers often lack adequate knowledge regarding the genetic basis of breast cancer, the role of BRCA mutations, and the benefits of early genetic counselling and testing [

25]. This paucity of knowledge significantly contributes to under-referral for genetic services, delayed diagnosis, and limited implementation of preventive strategies, such as enhanced surveillance, risk-reducing surgery, or targeted therapies [

29].

Healthcare providers, especially those working in primary and district-level facilities, may not receive sufficient training on hereditary cancer syndromes, failing to recognize individuals who meet the criteria for genetic testing. The limited incorporation of genetic education in medical and nursing curricula in many LMICs further perpetuates low levels of awareness and referral rates [

30].

Interestingly, cultural beliefs, religious considerations, and ethical concerns also play a substantial role in shaping attitudes toward genetic testing and counselling. In some communities, a cancer diagnosis is associated with stigma, fear, or fatalism, which can discourage individuals from seeking information or testing services [

31,

32]. Concerns around confidentiality, potential discrimination, and the psychological impact of knowing one’s genetic risk can also negatively influence the acceptance and uptake of genetic services [

31].

Therefore, addressing these challenges requires targeted public health education campaigns, culturally sensitive awareness programs, and improved training for healthcare workers at all levels of care. Community-based engagement, collaboration with traditional leaders, and integration of genetic counselling into routine oncology care can help bridge these gaps and enhance the early detection of BRCA mutations in resource-limited settings.

4.3. Healthcare Infrastructure and Resource Limitations

The healthcare systems in LMICs, particularly across Africa, face significant infrastructural and resource-related challenges that hinder the early detection and management of hereditary breast cancers, including those associated with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. One of the most pressing issues is the scarcity of trained professionals in genetics and oncology [

24,

33]. There is a marked shortage of certified genetic counsellors, clinical geneticists, and oncologists across many LMIC settings. This gap in human resources not only limits patient access to accurate risk assessment and genetic counselling but also impedes the integration of genetic testing into routine cancer care pathways [

34]. Furthermore, several LMICs do not have established national guidelines or reimbursement policies for genetic screening, making testing inaccessible or unaffordable for the majority of patients [

24,

35]. Moreover, access to reliable pathology and diagnostic services is often compromised due to under-resourced laboratories, inadequate equipment, and limited availability of trained histopathologists and molecular pathologists [

36]. Many facilities suffer from delays in tissue processing, poor sample quality, or misclassification of tumor subtypes, factors that contribute to late or inaccurate diagnoses. These systemic delays result in many patients presenting at advanced stages of disease when treatment options are limited and less effective [

37].

Access to care is exacerbated further by geographical and infrastructural barriers. Patients living in rural or remote areas often face long travel distances to reach tertiary care centers. In countries with limited referral networks, these patients are subjected to long waiting periods before receiving diagnostic imaging, biopsy, or surgical consultations [

38,

39]. Moreover, public hospitals are frequently overburdened with high patient volumes and insufficient staffing, which extends waiting times for both diagnostic and treatment services. These delays can lead to missed opportunities for early cancer detection, timely BRCA mutation screening, and effective risk-reducing strategies [

24,

40,

41]. Collectively, these healthcare system limitations highlight the urgent need for investments in infrastructure, capacity building, and policy development to improve the early detection and genetic risk assessment of breast cancer in LMICs. Without these measures, disparities in cancer outcomes between high-income and low-resource settings will continue to widen.

4.4. Low Referral and Testing Rates

Despite the existence of national and international clinical guidelines that recommend BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic testing for individuals considered at high risk such as women diagnosed with ovarian cancer under the age of 60 or those with a family history of breast or ovarian cancer, the actual referral and testing rates in many LMICs remain alarmingly low [

42]. In the South African public healthcare sector, it has been reported that, on average, only 3.9 ovarian cancer patients are referred for BRCA testing per year. This figure is disproportionately low given the estimated number of patients who meet the criteria for testing, indicating a significant gap between clinical recommendations and real-world practice [

25,

42,

43].

There are several factors that contribute to this underutilization. First, limited awareness and understanding of genetic testing among both healthcare providers and patients often result in missed opportunities for referral [

25,

46]. Most clinicians in LMICs receive minimal training in medical genetics, which can lead to uncertainty about which patients qualify for testing or how to navigate referral pathways. Additionally, genetic services are often centralized in urban academic hospitals, making them less accessible to patients in rural or underserved regions [

24,

45].

Systemic issues also play a critical role. In many public healthcare systems, there are no streamlined pathways for genetic counselling and testing, and referrals depend heavily on individual clinician initiative [

46,

47]. Moreover, genetic testing is often not integrated into routine oncology care, and testing may be delayed or overlooked in the face of more immediate clinical needs, such as chemotherapy or surgery [

48,

49]. Therefore, the implications of these low referral rates are profound. In the absence of genetic testing, many patients and their families remain unaware of hereditary cancer risk, missing the opportunity for risk-reducing strategies such as enhanced surveillance, prophylactic surgery, or cascade testing of at-risk relatives [

50,

51]. This contributes to delayed diagnosis, increased cancer burden, and higher mortality rates [

52].

4.5. Technical and Cost-Effectiveness Challenges

In LMICs, especially in many African countries, the clinical value of cascade testing which enables the identification of at-risk relatives of BRCA mutation carriers, remains markedly underutilized [

53]. Several interrelated technical and economic factors hinder the implementation of genetic testing. The high cost of genetic counselling and testing remains prohibitive for both patients and national health systems. Many public health systems in Africa do not have dedicated funding or reimbursement mechanisms for genetic testing, making it inaccessible to most families unless supported by research programs or international aid [

54,

55]. Furthermore, the lack of robust infrastructure for genetic services, including limited numbers of accredited laboratories, no or minimal local testing platforms and limited availability of trained genetic counsellors, contributes to these technical hurdles [

56]. These limitations often result in long turnaround times, reliance on international labs, and high expenses, thus discouraging follow-up testing on family members [

46].

Additionally, cascade testing programs require systematic identification and contact of family members, a process that is complicated in settings with fragmented health records, low health literacy, and sociocultural stigma associated with genetic diseases. These patients are reluctant to be tested because of fear of disclosure, concerns about discrimination, and a lack of understanding of how genetic testing can provide preventive services [

57,

58]. The absence of national guidelines mandating or facilitating cascade screening in public healthcare settings further compounds the problem, leaving a large proportion of at-risk individuals undiagnosed. Ultimately, the low uptake of cascade testing undermines the cost-effectiveness of BRCA mutation screening efforts by limiting their preventative impact, particularly in populations already burdened by resource constraints and late-stage cancer diagnoses [

59,

60].

5. Affordable and Scalable Strategies for Improving Detection of BRCA Mutations in Breast Cancer in LIMIC’s

In LMICs, the implementation of cost-effective and scalable strategies is essential for improving the detection of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations, which are associated with increased risk for hereditary breast and ovarian cancers [

61,

62]. Due to constrained healthcare budgets and limited laboratory infrastructure, traditional approaches such as full-gene sequencing are often not feasible at the population level. Therefore, several affordable and scalable alternatives have been proposed to improve early identification of at-risk individuals [

51,

62].

5.1. Use of Low-Cost Genotyping Techniques

Alternatively, cost-effective approaches based on polymerase chain reaction (PCR) have also been developed for known mutations in BRCA, including allele-specific PCR, real-time PCR and multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) [

63]. These targeted approaches are especially suitable in populations with well-characterized founder mutations or recurrent variants, where full sequencing may not be necessary. PCR-based methods offer the advantage of being relatively inexpensive, require minimal equipment, and can be implemented even in low-resource laboratory settings. Furthermore, advances in point-of-care molecular diagnostics could further simplify mutation detection at the community level [

64,

65].

5.2. Targeted Screening in High-Risk Populations

A resource-effective strategy involves focusing testing efforts on individuals who are at higher risk of carrying BRCA mutations. This includes women with a strong family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer, those diagnosed at a young age, or those with triple-negative breast cancer [

22]. Implementing clinical risk prediction tools, such as the Manchester or BOADICEA scoring systems, can help identify such individuals for priority testing. This targeted approach maximizes the yield of mutation detection and ensures efficient use of limited resources, making it a practical option for LMICs [

66,

67].

5.3. Integration into Existing Healthcare Programs

Leveraging existing healthcare infrastructure, particularly programs already focused on chronic conditions such as HIV, tuberculosis, or non-communicable diseases (NCDs), can significantly improve the reach and sustainability of BRCA testing initiatives [

68,

69]. For example, integrating genetic counselling and risk assessment at maternal and child health clinics, HIV treatment facilities, or NCD clinic settings can provide wider access to testing services without implementing separate programs. This integrated approach also supports continuity of care and enables cross-referral for women who may already be accessing healthcare services for other reasons [

68,

70].

5.2. Mobile Health (mHealth) and Tele-Genetics Initiatives

The introduction of mobile health (mHealth) systems and telemedicine technology has the potential to revolutionize people’s access to genetic services in underserved or remote locations. The mHealth applications can facilitate the dissemination of educational content, enable remote risk assessments, and support electronic referral systems for genetic testing [

71,

72]. Tele-genetics services can bridge the gap in access to trained genetic counsellors by allowing virtual consultations, therefore overcoming geographical and workforce limitations. These digital solutions are particularly promising in countries with high mobile phone penetration, and they offer a scalable model for delivering genetic information and support [

73]. Collectively, these strategies offer a multidimensional framework for improving BRCA mutation detection in low-resource settings. By combining low-cost diagnostics, targeted risk-based screening, integration into routine healthcare services, and the use of digital health tools, LMICs can develop sustainable and equitable models for hereditary cancer risk assessment. These strategies not only improve early detection and prevention but also support personalized care and better outcomes for individuals affected by breast cancer [

74].

Figure 3 provides an overview of the barriers to early BRCA mutation detection in LMICs and highlights affordable strategies to improve detection.

6. Policy Recommendations and Future Directions

Despite the growing importance of genetic testing for hereditary breast cancer, access to BRCA testing remains limited in many LMICs due to high costs, limited laboratory infrastructure, lack of trained personnel, and low awareness among healthcare providers and the public [

75]. There is a critical need for advocacy efforts that emphasize the integration of genetic services into national cancer control plans and public healthcare systems. Governments, civil society organizations, and international health agencies must work collaboratively to subsidize the cost of genetic testing, ensure the availability of appropriate genetic counselling services, and educate communities about the benefits and implications of genetic risk assessment [

76]. Equitable access should be prioritized, especially for high-risk individuals, including those with strong family histories or early-onset breast cancer, regardless of socioeconomic or geographic barriers [

77,

78].

Policy frameworks that utilize information generated by genomic data will require clear policy guidance in LMICs to address the ethical, legal, and social issues associated with genetic testing. Such frameworks need to be consistent with national health priorities and protect data privacy, informed consent, non-discrimination, and access to follow-up care [

79,

80]. The policy should allow for cost-effective testing, including targeted gene panels, population screening in populations with founder gene mutation and integration with existing health programs such as HIV clinics and NCD (Non-Communicable Disease) clinics [

54,

81]. The public–private partnership can be applied to enhance laboratory infrastructure and bioinformatics capacity. Additionally, education for healthcare providers (including family practitioners and nurses) should be established to increase local capacity in genetic risk assessment and counselling [

82].

Concernedly, most BRCA mutation research to date has been conducted in HICs and among populations of European ancestry, leading to significant gaps in our understanding of the mutation spectrum and cancer risk in African and other underrepresented populations [

83,

84]. LMICs, particularly in African countries, require more inclusive, population-specific genomic studies to better characterize the prevalence, penetrance, and types of BRCA mutations [

10]. These studies will inform the development of appropriate diagnostic tools, risk models, and prevention strategies. Research should also address psychosocial, cultural, and structural barriers to testing uptake and cascade screening. Building local biobanks, promoting data sharing, and strengthening collaboration between LMIC researchers and global genomics initiatives will be essential in closing the data gap and fostering equitable advancements in cancer genomics.

7. Conclusions

Breast cancer continues to pose a major public health burden in LMICs, where limited resources, socioeconomic challenges, and low awareness drive delayed diagnosis and poor outcomes. Despite the critical role of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in hereditary breast cancer, access to genetic testing and counselling remains scarce and inequitable. This review highlights the multifaceted barriers to early BRCA detection, while also highlighting feasible, cost-effective strategies, including affordable genotyping, targeted testing of high-risk groups, integration into existing health programs, and the use of digital health solutions. To build sustainable capacity, LMICs will require policies that increase access to testing, train providers and integrate genetics into cancer care. Strong partnerships between governments, researchers, and global stakeholders are also essential. Improving early detection of BRCA mutations in LMICs is not only a scientific and clinical priority but also a matter of health equity. Investing in scalable, context-appropriate genetic testing strategies has the potential to transform breast cancer prevention, diagnosis, and treatment in resource-limited settings, offering women and families at risk a better chance at survival and improved quality of life.

Author Contributions

I confirm that all authors contributed to the conceptualization, review, and editing of the manuscript in preparation for submission. All listed authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University, particularly the Department of Chemical Pathology for their immense support that made this review possible.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no competing interests declared by the authors.

References

- Arnold, M.; Morgan, E.; Rumgay, H.; Mafra, A.; Singh, D.; Laversanne, M.; Vignat, J.; Gralow, J.R.; Cardoso, F.; Siesling, S.; et al. Current and future burden of breast cancer: Global statistics for 2020 and 2040. Breast 2022, 66, 15–23. [CrossRef]

- Pace, L.E.; Shulman, L.N. Breast Cancer in Sub-Saharan Africa: Challenges and Opportunities to Reduce Mortality. Oncol. 2016, 21, 739–744. [CrossRef]

- A Anyigba, C.; A Awandare, G.; Paemka, L. Breast cancer in sub-Saharan Africa: The current state and uncertain future. Exp. Biol. Med. 2021, 246, 1377–1387. [CrossRef]

- Dlamini, Z., Molefi, T., Khanyile, Mkhabele, M., Damane B., Bida M., Chauke-Malinga N., Hull, R. From Incidence to Intervention: A Comprehensive Look at Breast Cancer in South Africa. Oncol Ther. 2024, 12, 1–11.

- Yakong, V.N.; Afaya, A.; Alhassan, R.K.; Sang, S.; Salia, S.M.; Afaya, R.A.; Karim, J.F.; Kuug, A.; Selorm, D.-D.S.; Atakro, C.A.; et al. Leveraging breast cancer screening to promote timely detection, diagnosis and treatment among women in sub-Saharan Africa: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e058729. [CrossRef]

- Petrucelli, N., Daly, M.B., Pal, T. BRCA1-and BRCA2-Associated Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer. 1998 September 4 [updated March 20, 2025]. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa, G.M., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Amemiya, A., editors. Gene Reviews ® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993–2025.

- Arun, B.; Couch, F.J.; Abraham, J.; Tung, N.; Fasching, P.A. BRCA-mutated breast cancer: the unmet need, challenges and therapeutic benefits of genetic testing. Br. J. Cancer 2024, 131, 1400–1414. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Hao, X.; Song, Z.; Zhi, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, J. Correlation between family history and characteristics of breast cancer. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Christopher, P.W., Weiderpass, E., Bernard, W.S: World Cancer Report: Cancer Research for Cancer Prevention. Lyon, France, International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2020, 1-630.

- Hayat, M.; Chen, W.C.; Brandenburg, J.-T.; de Villiers, C.B.; Ramsay, M.; Mathew, C.G. Genetic Susceptibility to Breast Cancer in Sub-Saharan African Populations. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2021, 7, 1462–1471. [CrossRef]

- Sibomana, O. Genetic Diversity Landscape in African Population: A Review of Implications for Personalized and Precision Medicine. Pharmacogenomics Pers. Med. 2024, ume 17, 487–496. [CrossRef]

- Samodien, E., Abrahams, Y., Muller, C., Louw, J., Chellan, N. Noncommunicable diseases—a catastrophe for South Africa. S Afr J Sci. 2021;117(5/6).

- WHO. WHO report on cancer: Setting priorities, investing wisely and providing care for all. Report No.: 9789240001299. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020.

- Finestone, E.; Wishnia, J. Estimating the burden of cancer in South Africa. South Afr. J. Oncol. 2022, 6. [CrossRef]

- Creeden, J.F.; Nanavaty, N.S.; Einloth, K.R.; Gillman, C.E.; Stanbery, L.; Hamouda, D.M.; Dworkin, L.; Nemunaitis, J. Homologous recombination proficiency in ovarian and breast cancer patients. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Huo, Y.; Selenica, P.; Mahdi, A.H.; Pareja, F.; Kyker-Snowman, K.; Chen, Y.; Kumar, R.; Paula, A.D.C.; Basili, T.; Brown, D.N.; et al. Genetic interactions among Brca1, Brca2, Palb2, and Trp53 in mammary tumor development. npj Breast Cancer 2021, 7, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Tang, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, S.; Cao, S.; Li, X. Association Between BRCA Status and Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 909. [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, K.; Lynch, H.T.; Foulkes, W.D.; Tung, N.; Olopade, O.I.; Eisen, A.; Lerner-Ellis, J.; Snyder, C.; Kim, S.J.; Sun, P.; et al. Oestrogen receptor status and survival in women with BRCA2-associated breast cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2019, 120, 398–403. [CrossRef]

- Kuchenbaecker, K.B.; Hopper, J.L.; Barnes, D.R.; Phillips, K.-A.; Mooij, T.M.; Roos-Blom, M.-J.; Jervis, S.; Van Leeuwen, F.E.; Milne, R.L.; Andrieu, N.; et al. Risks of Breast, Ovarian, and Contralateral Breast Cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation Carriers. JAMA 2017, 317, 2402–2416. [CrossRef]

- Pilarski, R. The Role of BRCA Testing in Hereditary Pancreatic and Prostate Cancer Families. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2019, 39, 79–86. [CrossRef]

- Gorodetska, I.; Kozeretska, I.; Dubrovska, A. BRCA Genes: The Role in Genome Stability, Cancer Stemness and Therapy Resistance. J. Cancer 2019, 10, 2109–2127. [CrossRef]

- Godet, I., Gilkes, D.M. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations and treatment strategies for breast cancer. Integr Cancer Sci Ther. 2017, 4, 10.15761/ICST.

- Meynard, G.; Mansi, L.; Lebahar, P.; Villanueva, C.; Klajer, E.; Calcagno, F.; Vivalta, A.; Chaix, M.; Collonge-Rame, M.-A.; Populaire, C.; et al. First description of a double heterozygosity for BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variants in a French metastatic breast cancer patient: A case report. Oncol. Rep. 2017, 37, 1573–1578. [CrossRef]

- Saj, F.; Nag, S.; Nair, N.; Sirohi, B. Management of BRCA-associated breast cancer patients in low and middle-income countries: a review. ecancermedicalscience 2024, 18. [CrossRef]

- Osler, T.S.; Schoeman, M.; Edge, J.; Pretorius, W.J.S.; Rabe, F.H.; Mathew, C.G.; Urban, M.F. Breast Cancer Genetic Services in a South African Setting: Proband Testing, Cascading and Clinical Management. Cancer Med. 2025, 14, e70743. [CrossRef]

- A Gardiner, S.; Smith, D.; Loubser, F.; Raimond, P.; Gerber, J.; Conradie, M. New recurring BRCA1 variant: An additional South African founder mutation?. South Afr. Med J. 2019, 109, 544–544. [CrossRef]

- Hooley, B.; Afriyie, D.O.; Fink, G.; Tediosi, F. Health insurance coverage in low-income and middle-income countries: progress made to date and related changes in private and public health expenditure. BMJ Glob. Heal. 2022, 7, e008722. [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Care Services; Committee on Health Care Utilization and Adults with Disabilities. Health-Care Utilization as a Proxy in Disability Determination. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2018 Mar 1. 2, Factors That Affect Health-Care Utilization. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK500097/.

- Tshabalala, G.; Blanchard, C.; Mmoledi, K.; Malope, D.; O’nEil, D.S.; Norris, S.A.; Joffe, M.; Dietrich, J.J. A qualitative study to explore healthcare providers’ perspectives on barriers and enablers to early detection of breast and cervical cancers among women attending primary healthcare clinics in Johannesburg, South Africa. PLOS Glob. Public Heal. 2023, 3, e0001826. [CrossRef]

- Walters, S.; Aldous, C.; Malherbe, H. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of primary healthcare practitioners in low- and middle-income countries: a scoping review on genetics. J. Community Genet. 2024, 15, 461–474. [CrossRef]

- for the PROMISE study team; Hann, K.E.J.; Freeman, M.; Fraser, L.; Waller, J.; Sanderson, S.C.; Rahman, B.; Side, L.; Gessler, S.; Lanceley, A. Awareness, knowledge, perceptions, and attitudes towards genetic testing for cancer risk among ethnic minority groups: a systematic review. BMC Public Heal. 2017, 17, 1–30. [CrossRef]

- Yi, H.; Trivedi, M.S.; Crew, K.D.; Schechter, I.; Appelbaum, P.; Chung, W.K.; Allegrante, J.P.; Kukafka, R. Understanding Social, Cultural, and Religious Factors Influencing Medical Decision-Making on BRCA1/2 Genetic Testing in the Orthodox Jewish Community. Public Heal. Genom. 2024, 27, 57–67. [CrossRef]

- Eldridge, L., Goodman, N.R., Chtourou, A., Galassi, A., Monge, C., Cira, M.K., Pearlman, P.C., Loehrer, P.J Sr., Gopal, S., Ginsburg, O. Barriers and Opportunities for Cancer Clinical Trials in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. JAMA Netw Open. 2025, 8, e257733.

- Apofeed. Urgent action needed to reinforce breast cancer control measures in Africa: World Health Organization (WHO) report. February 4th, 2025. https://african.business/2025/02/apo-newsfeed/urgent-action-needed-to-reinforce-breast-cancer-control-measures-in-africa-world-health-organization-who-report.

- Goh, S.P.; Ong, S.C.; Chan, J.E. Economic evaluation of germline genetic testing for breast cancer in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Ziegenhorn, H.-V.; Frie, K.G.; Ekanem, I.-O.; Ebughe, G.; Kamate, B.; Traore, C.; Dzamalala, C.; Ogunbiyi, O.; Igbinoba, F.; Liu, B.; et al. Breast cancer pathology services in sub-Saharan Africa: a survey within population-based cancer registries. BMC Heal. Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Tesfaw, A.; Demis, S.; Munye, T.; Ashuro, Z. Patient Delay and Contributing Factors Among Breast Cancer Patients at Two Cancer Referral Centres in Ethiopia: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Multidiscip. Heal. 2020, ume 13, 1391–1401. [CrossRef]

- Sarmah, N.; Sibiya, M.N.; Khoza, T.E. Barriers and enablers to breast cancer screening in rural South Africa. Curationis 2023, 47, 8–e8. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Macharia, P.M.; McCormack, V.; Foerster, M.; Galukande, M.; Joffe, M.; Cubasch, H.; Zietsman, A.; Anele, A.; Offiah, S.; et al. Geospatial disparities in survival of patients with breast cancer in sub-Saharan Africa from the African Breast Cancer-Disparities in Outcomes cohort (ABC-DO): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Glob. Heal. 2024, 12, e1111–e1119. [CrossRef]

- Joffe, M.; Ayeni, O.; Norris, S.A.; McCormack, V.A.; Ruff, P.; Das, I.; I Neugut, A.; Jacobson, J.S.; Cubasch, H. Barriers to early presentation of breast cancer among women in Soweto, South Africa. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0192071. [CrossRef]

- Minucci, A., Scambia, G., De Bonis, M., De Paolis, E., Santonocito, C., Fagotti, A., Capoluongo, E., Concolino, P., Urbani, A. BRCA testing delay during the COVID-19 pandemic: How to act? Mol Biol Rep. 2021, 48, 983-987.

- van der Merwe, N.C.; Ntaita, K.S.; Stofberg, H.; Combrink, H.M.; Oosthuizen, J.; Kotze, M.J. Implementation of multigene panel testing for breast and ovarian cancer in South Africa: A step towards excellence in oncology for the public sector. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 938561. [CrossRef]

- Van der Merwe, N.C.; Combrink, H.M.; Ntaita, K.S.; Oosthuizen, J. Prevalence of Clinically Relevant Germline BRCA Variants in a Large Unselected South African Breast and Ovarian Cancer Cohort: A Public Sector Experience. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 834265. [CrossRef]

- Wuraola, F.O.; Dare, A.; Ramruthan, J.; Reel, E.; Santiago, A.T.; Sharif, F.; Olayide, A.; Sunday-Nweke, N.; Alatise, O.; Cil, T.D. Knowledge and perceptions of genetic testing for patients with breast cancer in Nigeria: a survey of healthcare providers. Hered. Cancer Clin. Pr. 2025, 23, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Yip, C.H.; Evans, D.G.; Agarwal, G.; Buccimazza, I.; Kwong, A.; Morant, R.; Prakash, I.; Song, C.Y.; Taib, N.A.; Tausch, C.; et al. Global Disparities in Breast Cancer Genetics Testing, Counselling and Management. World J. Surg. 2019, 43, 1264–1270. [CrossRef]

- Dusic, E.J.; Theoryn, T.; Wang, C.; Swisher, E.M.; Bowen, D.J.; EDGE Study Team Barriers, interventions, and recommendations: Improving the genetic testing landscape. Front. Digit. Heal. 2022, 4, 961128. [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y., Barge, H., Escoffery, C., Cellai, M., Alfonso, S., Johnson II, T.M. Examining barriers and facilitators to implementing evidence-based genetic risk-stratified breast cancer screening in primary care. Front. Cancer Control Soc. 2025, 3, 1521486.

- Freitas-Junior, R.; Ferreira-Filho, D.L.; Soares, L.R.; Paulinelli, R.R. Oncoplastic Breast-Conserving Surgery in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Training Surgeons and Bridging the Gap. Curr. Breast Cancer Rep. 2019, 11, 136–142. [CrossRef]

- Afaya, A.; Ramazanu, S.; Bolarinwa, O.A.; Yakong, V.N.; Afaya, R.A.; Aboagye, R.G.; Daniels-Donkor, S.S.; Yahaya, A.-R.; Shin, J.; Dzomeku, V.M.; et al. Health system barriers influencing timely breast cancer diagnosis and treatment among women in low and middle-income Asian countries: evidence from a mixed-methods systematic review. BMC Heal. Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Adedokun, B.; Zheng, Y.; Ndom, P.; Gakwaya, A.; Makumbi, T.; Zhou, A.Y.; Yoshimatsu, T.F.; Rodriguez, A.; Madduri, R.K.; Foster, I.T.; et al. Prevalence of Inherited Mutations in Breast Cancer Predisposition Genes among Women in Uganda and Cameroon. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers Prev. 2020, 29, 359–367. [CrossRef]

- Adejumo, P.O.; Aniagwu, T.I.; Awolude, O.A.; Adedokun, B.; Kochheiser, M.; Sowunmi, A.; Popoola, A.; Ojengbede, O.; Huo, D.; Olopade, O.I. Cancer Genetic Services in a Low- to Middle-Income Country: Cross-Sectional Survey Assessing Willingness to Undergo and Pay for Germline Genetic Testing. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2023, 9, e2100140. [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.B.A., Barrios, C., de Jesus, R.G., et al.Germline Genetic Testing in Breast Cancer: Utilization and Disparities in a Middle-Income Country. JCO Glob Oncol. 2025, 11, e2400337.

- Ongaro, G.; Hamilton, J.G.; Groner, V.; Hay, J.L.; Calvello, M.; Oliveri, S.; Bonanni, B.; Feroce, I.; Pravettoni, G. A Multi-Level Analysis of Barriers and Promoting Factors to Cascade Screening Uptake Among Male Relatives of BRCA1/2 Carriers: A Qualitative Study. Psycho-Oncology 2025, 34, e70160. [CrossRef]

- Adebamowo, S.N.; Francis, V.; Tambo, E.; Diallo, S.H.; Landouré, G.; Nembaware, V.; Dareng, E.; Muhamed, B.; Odutola, M.; Akeredolu, T.; et al. Implementation of genomics research in Africa: challenges and recommendations. Glob. Heal. Action 2018, 11, 1419033. [CrossRef]

- Kamga, K.K.; Marlyse, P.F.; Nguefack, S.; Wonkam, A. Advancing genetic services in African healthcare: Challenges, opportunities, and strategic insights from a scoping review. Hum. Genet. Genom. Adv. 2025, 6, 100439. [CrossRef]

- Kwong, A.; Tan, D.S.; Ryu, J.M.; the ACROSS Consortium Current practices and challenges in genetic testing and counseling for women with breast and ovarian cancer in Asia. Asia-Pacific J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 21, 211–220. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, M.C., Dotson, W.D., DeVore, C.S., Bednar, E.M., Bowen, D.J., Ganiats, T.G., Green, R.F., Hurst, G.M., Philp, A.R., Ricker, C.N., Sturm, A.C., Trepanier, A.M., Williams, J.L., Zierhut, H.A., Wilemon, K.A., Hampel, H. Delivery Of Cascade Screening For Hereditary Conditions: A Scoping Review Of The Literature. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018, 37, 801-808.

- Srinivasan, S.; Won, N.Y.; Dotson, W.D.; Wright, S.T.; Roberts, M.C. Barriers and facilitators for cascade testing in genetic conditions: a systematic review. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2020, 28, 1631–1644. [CrossRef]

- Manchanda, R.; Patel, S.; Gordeev, V.S.; Antoniou, A.C.; Smith, S.; Lee, A.; Hopper, J.L.; MacInnis, R.J.; Turnbull, C.; Ramus, S.J.; et al. Cost-effectiveness of Population-Based BRCA1, BRCA2, RAD51C, RAD51D, BRIP1, PALB2 Mutation Testing in Unselected General Population Women. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2018, 110, 714–725. [CrossRef]

- Kahn, R.M.; Ahsan, M.D.; Chapman-Davis, E.; Holcomb, K.; Nitecki, R.; Rauh-Hain, J.A.; Fowlkes, R.K.; Tubito, F.; Pires, M.; Christos, P.J.; et al. Barriers to completion of cascade genetic testing: how can we improve the uptake of testing for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome?. Fam. Cancer 2022, 22, 127–133. [CrossRef]

- McAlarnen, L.; Stearns, K.; Uyar, D. Challenges of Genomic Testing for Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancers. Appl. Clin. Genet. 2021, ume 14, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Bourke, M.; McInerney-Leo, A.; Steinberg, J.; Boughtwood, T.; Milch, V.; Ross, A.L.; Ambrosino, E.; Dalziel, K.; Franchini, F.; Huang, L.; et al. The Cost Effectiveness of Genomic Medicine in Cancer Control: A Systematic Literature Review. Appl. Heal. Econ. Heal. Policy 2025, 23, 359–393. [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Hu, O.; Chen, M.; Liang, Z.; Liang, L.; Chen, Z. A novel and cost-efficient allele-specific PCR method for multiple SNP genotyping in a single run. Anal. Chim. Acta 2022, 1229, 340366. [CrossRef]

- Ezquerra-Inchausti, M., Anasagasti, A., Barandika, O., Garay-Aramburu, G., Galdós, M., López de Munain, A., Irigoyen, C., Ruiz-Ederra, J. A new approach based on targeted pooled DNA sequencing identifies novel mutations in patients with Inherited Retinal Dystrophies. Sci Rep. 2018, 18;8, 15457.

- Khodaparast, M.; Sharley, D.; Marshall, S.; Beddoe, T. Advances in point-of-care and molecular techniques to detect waterborne pathogens. npj Clean Water 2024, 7, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Ming, C.; Viassolo, V.; Probst-Hensch, N.; Chappuis, P.O.; Dinov, I.D.; Katapodi, M.C. Machine learning techniques for personalized breast cancer risk prediction: comparison with the BCRAT and BOADICEA models. Breast Cancer Res. 2019, 21, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Bahl, M. Assessing Risk of Breast Cancer: A Review of Risk Prediction Models. J. Breast Imaging 2021, 3, 144–155. [CrossRef]

- Brault, M.A.; Vermund, S.H.; Aliyu, M.H.; Omer, S.B.; Clark, D.; Spiegelman, D. Leveraging HIV Care Infrastructures for Integrated Chronic Disease and Pandemic Management in Sub-Saharan Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 10751. [CrossRef]

- van der Mannen, J.S.; Heine, M.; Lalla-Edward, S.T.; Ojji, D.B.; Mocumbi, A.O.; Klipstein-Grobusch, K. Lessons Learnt from HIV and Noncommunicable Disease Healthcare Integration in Sub-Saharan Africa. Glob. Hear. 2024, 19. [CrossRef]

- Dowdy, D.W.; A Powers, K.; Hallett, T.B. Towards evidence-based integration of services for HIV, non-communicable diseases and substance use: insights from modelling. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2020, 23, e25525. [CrossRef]

- Gorrie, A.; Gold, J.; Cameron, C.; Krause, M.; Kincaid, H. Benefits and limitations of telegenetics: A literature review. J. Genet. Couns. 2021, 30, 924–937. [CrossRef]

- Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics; Mathews, D.; Abernethy, A.; Verily; Butte, A.J.; Ginsburg, P.; University of Southern California; Kocher, B.; Venrock; Novelli, C.; et al. Telehealth and Mobile Health: Case Study for Understanding and Anticipating Emerging Science and Technology. NAM Perspect. 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- McCool, J.; Dobson, R.; Whittaker, R.; Paton, C. Mobile Health (mHealth) in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Annu. Rev. Public Heal. 2022, 43, 525–539. [CrossRef]

- Schliemann, D.; Tan, M.M.; Hoe, W.M.K.; Mohan, D.; Taib, N.A.; Donnelly, M.; Su, T.T. mHealth Interventions to Improve Cancer Screening and Early Detection: Scoping Review of Reviews. J. Med Internet Res. 2022, 24, e36316. [CrossRef]

- Martinez, M.E.; Schmeler, K.M.; Lajous, M.; Newman, L.A. Cancer Screening in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2024, 44, e431272. [CrossRef]

- Kamga, K.K., Fonkam, M.P., Nguefack, S., Wonkam, A. Navigating the Genetic Frontier for the Integration of Genetic Services into African Healthcare Systems: A scoping review. Res Sq [Preprint]. 2024, rs.3.rs-3978686.

- Swami, N.; Yamoah, K.; Mahal, B.A.; Dee, E.C. The right to be screened: Identifying and addressing inequities in genetic screening. Lancet Reg. Heal. - Am. 2022, 11, 100251. [CrossRef]

- Wilkerson, A.D.; Gentle, C.K.; Ortega, C.; Al-Hilli, Z. Disparities in Breast Cancer Care—How Factors Related to Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment Drive Inequity. Healthcare 2024, 12, 462. [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. Genomic Data Policy Framework and Ethical Tensions, June 2020. Available:chromeextension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Genomic_Data_Policy_and_Ethics_Framework_pages_2020.

- Ralalage, P.B.; Mitchell, T.; Zammit, C.; Baynam, G.; Kowal, E.; Masey, L.; McLaughlin, J.; Boughtwood, T.; Jenkins, M.; Pratt, G.; et al. “Equity” in genomic health policies: a review of policies in the international arena. Front. Public Heal. 2024, 12, 1464701. [CrossRef]

- Mudau, M.M.; Seymour, H.; Nevondwe, P.; Kerr, R.; Spencer, C.; Feben, C.; Lombard, Z.; Honey, E.; Krause, A.; Carstens, N. A feasible molecular diagnostic strategy for rare genetic disorders within resource-constrained environments. J. Community Genet. 2023, 15, 39–48. [CrossRef]

- Fanelli, S.; Salvatore, F.P.; De Pascale, G.; Faccilongo, N. Insights for the future of health system partnerships in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic literature review. BMC Heal. Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Felix, G.E.S.; Zheng, Y.; Olopade, O.I. Mutations in context: implications of BRCA testing in diverse populations. Fam. Cancer 2018, 17, 471–483. [CrossRef]

- Cupertino, S.E.S.; Gonçalves, A.C.A.; Lopes, C.V.G.; Gradia, D.F.; Beltrame, M.H. The Current State of Breast Cancer Genetics in Populations of African Ancestry. Genes 2025, 16, 199. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).