Submitted:

17 October 2025

Posted:

22 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

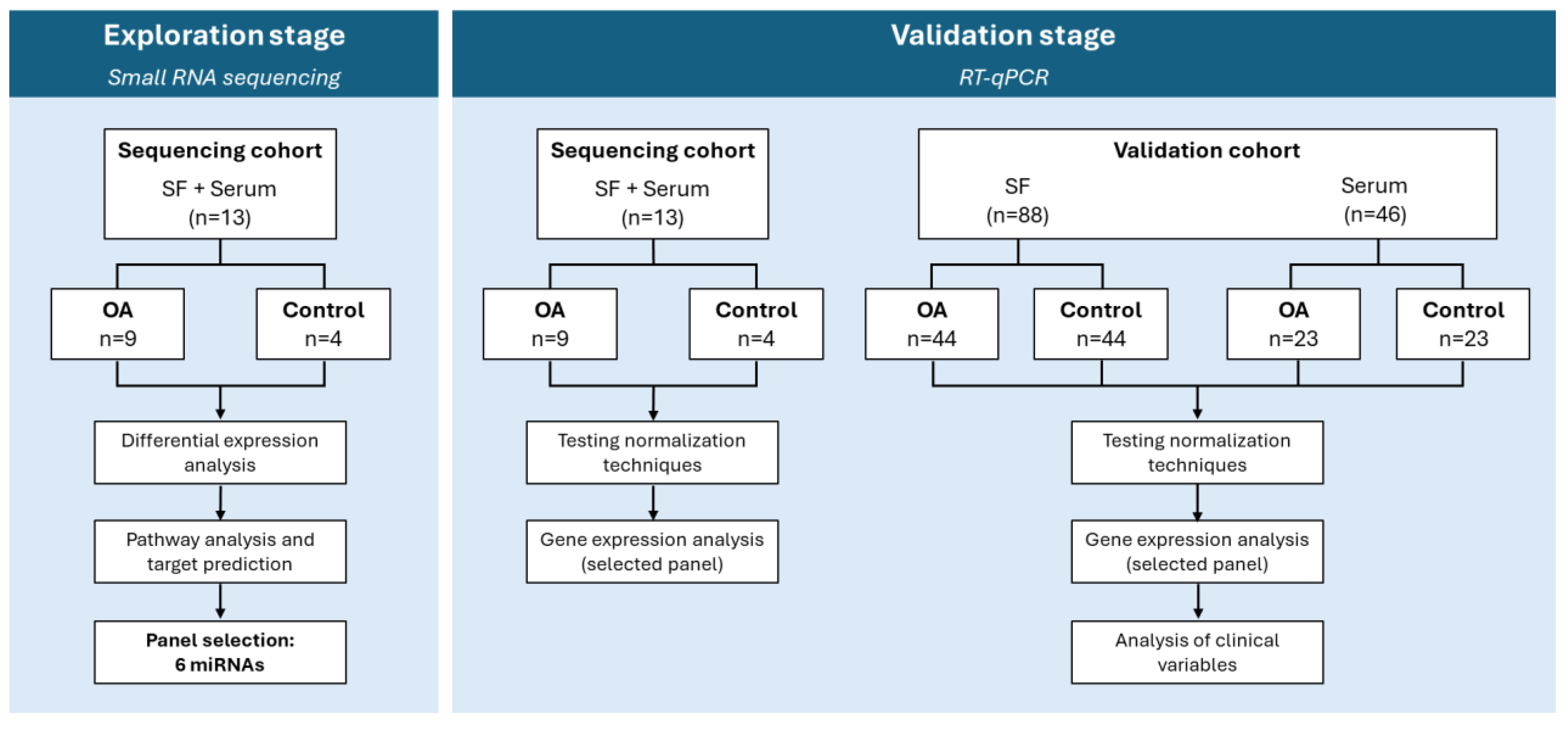

2.1. Exploration Stage

2.1.1. Sample and Group Characterization

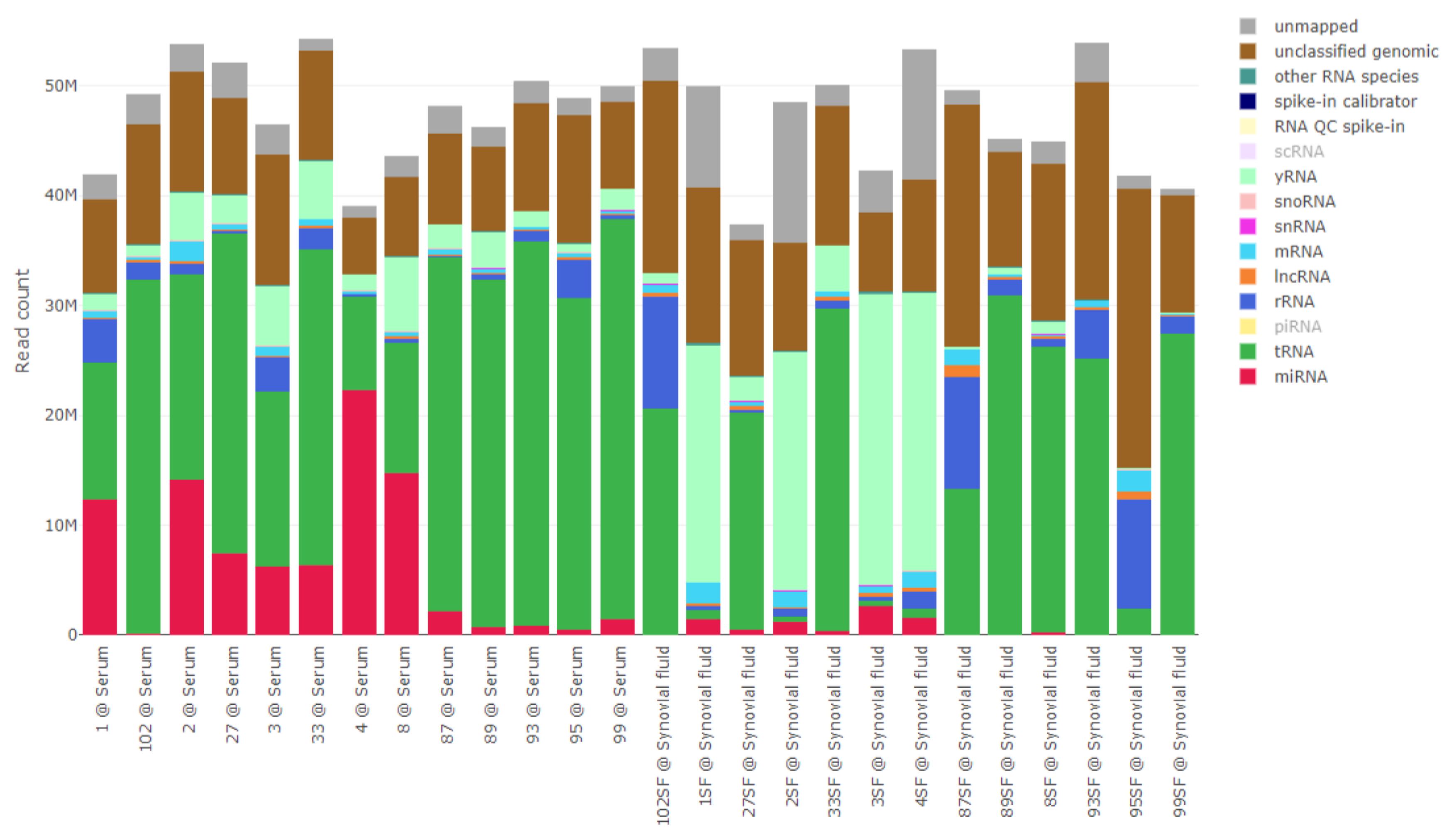

2.1.2. Data Overview

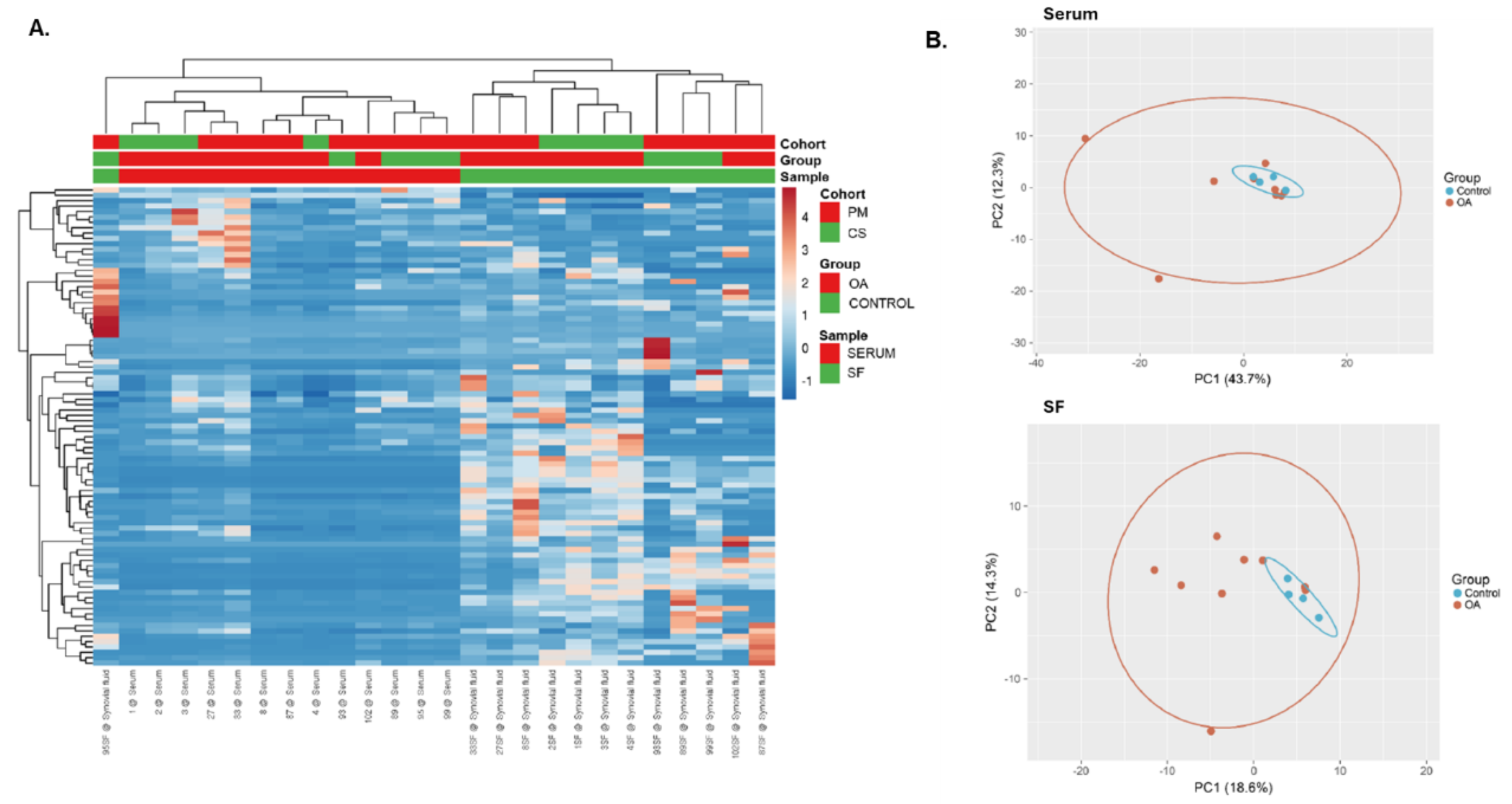

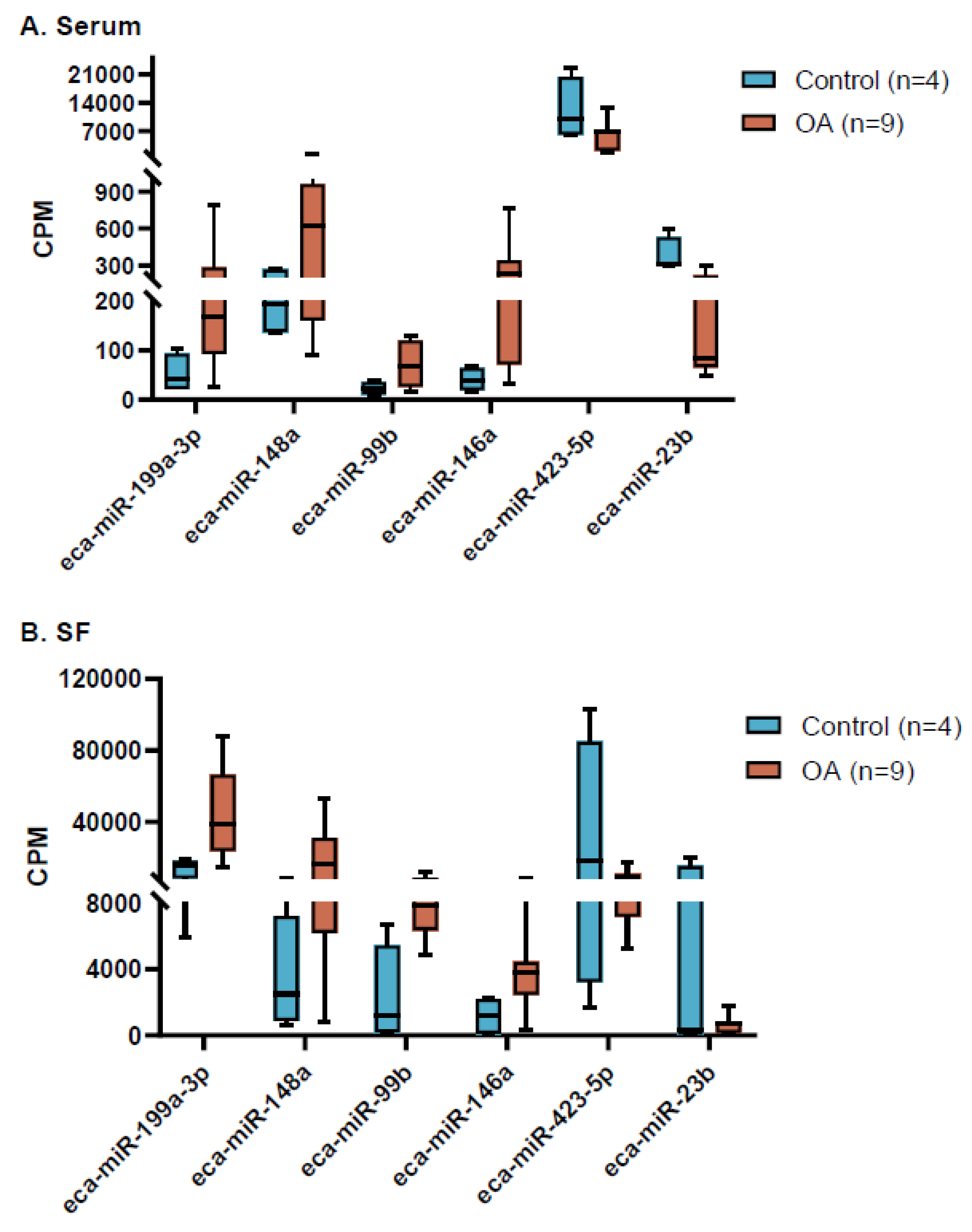

2.1.3. Differential Expression Analysis

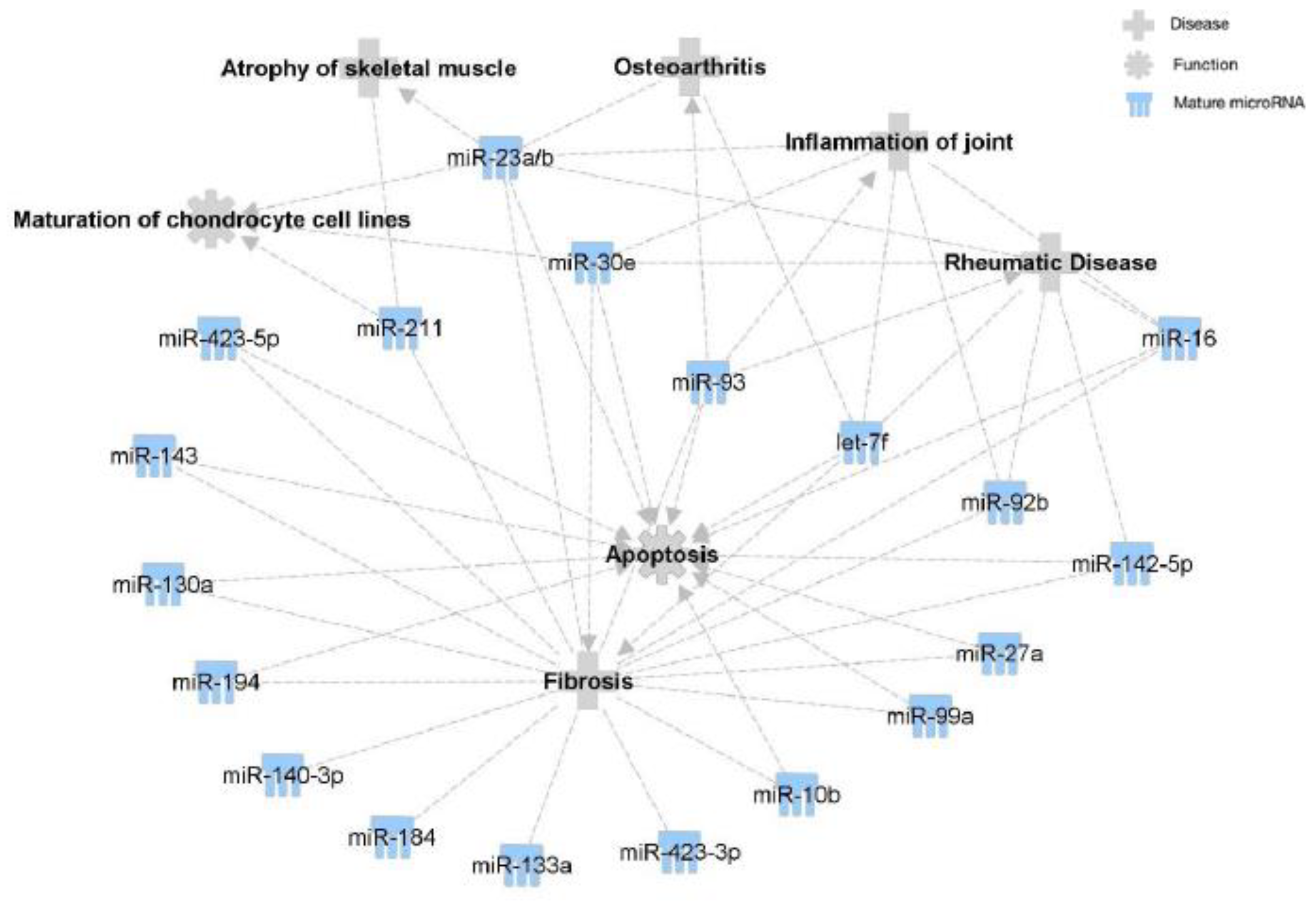

2.1.4. Target Prediction and Pathway Analysis

2.1.5. Selection of miRNAs for Validation

2.2. Validation Stage

2.2.1. Sample and Group Characterization

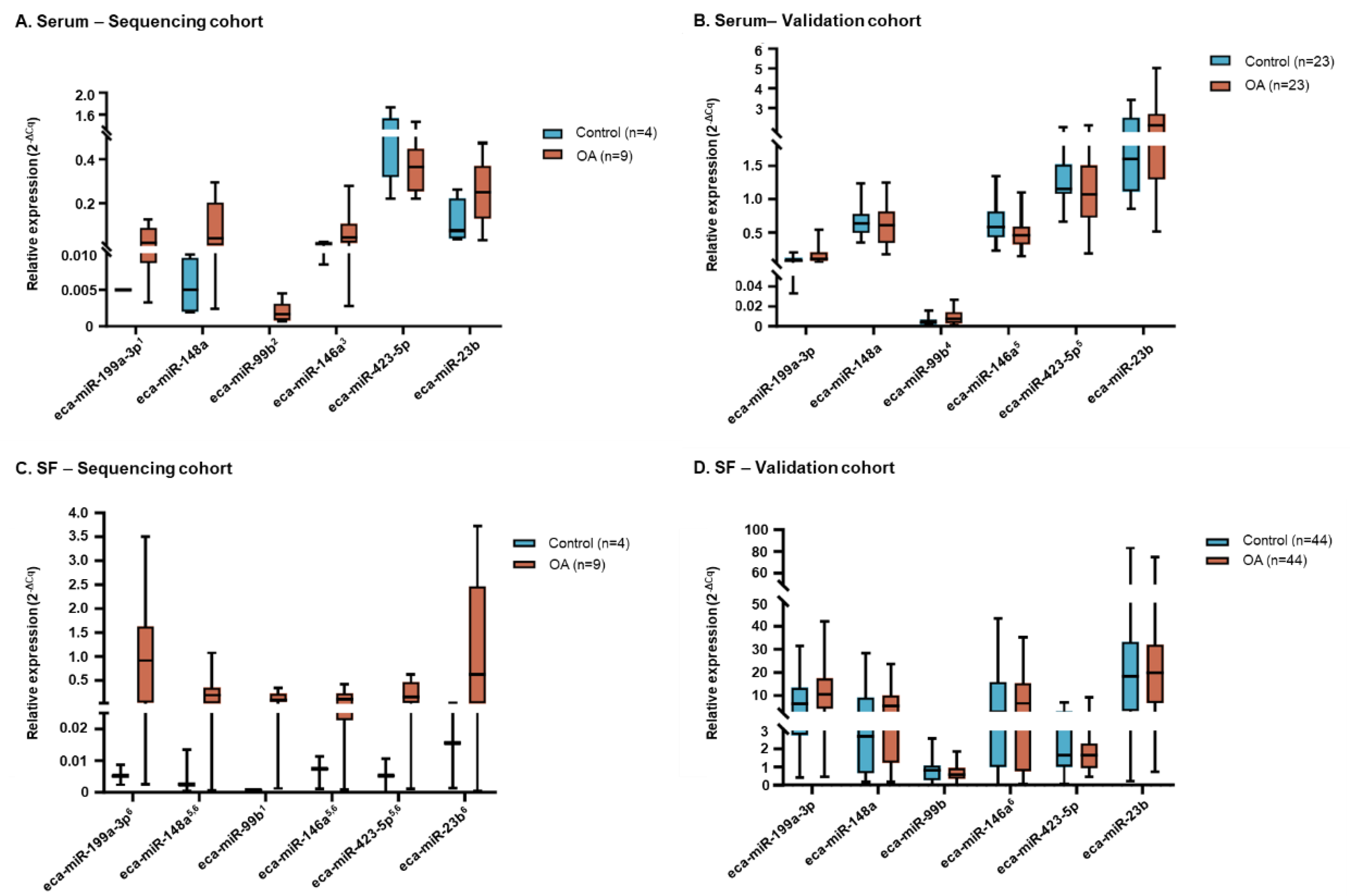

2.2.2. Relative Gene Expression

2.2.3. Influence of Clinical Variables

3. Discussion

4. Methods

4.1. Exploration Stage

4.1.1. Sample Collection (Sequencing Cohort)

4.1.2. Group Categorization (Sequencing Cohort)

4.1.3. Sample Pre-Processing and RNA Isolation

4.1.4. Library Preparation and Sequencing

4.1.5. Data Analysis

4.1.5.1. Small RNA Sequencing Data Processing and Analysis

4.1.6. Pathway Analysis

4.1.6. Selection of Differentially Expressed miRNAs for Validation

4.2. Validation Stage

4.2.1. Sample Collection (Validation Cohort)

4.2.2. Group Characterization (Validation Cohort)

4.2.3. Sample Size Calculation

4.2.4. RNA Extraction, cDNA Synthesis and RT-qPCR

4.2.5. RT-qPCR Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADAMTS5 | A disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin type 1 motif 5 |

| BCS | Body condition score |

| cDNA | Complementary DNA |

| CPM | Counts per million |

| Cq | Quantification cycle |

| CS | Clinical sample |

| CV | Coefficient of variation |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| FC | Fold change |

| FDR | False discovery rate |

| IL | interleukin |

| IPA | Ingenuity Pathway Analysis |

| lncRNA | Long non-coding RNA |

| Max | Maximum |

| Min | Minimum |

| MMP | Metalloproteinase |

| mRNA | Messenger RNA |

| miRNA | microRNA |

| OA | Osteoarthritis |

| OARSI | Osteoarthritis Research Society International |

| PC | Principal component |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| piRNA | Piwi-interfering RNA |

| PM | Post-mortem |

| QC | Quality control |

| qPCR | Quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| RPM | Reads per million |

| rRNA | Ribosomal RNA |

| RT-qPCR | Reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| scRNA | Small conditional RNA |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SF | Synovial fluid |

| siRNA | Small interfering RNA |

| snRNA | Small nuclear RNA |

| snoRNA | Small nucleolar RNA |

| tRNA | Transfer RNA |

References

- Morris, K. V; Mattick, J.S. The Rise of Regulatory RNA. Nat Rev Genet 2014, 15, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hombach, S.; Kretz, M. Non-Coding RNAs: Classification, Biology and Functioning. In Non-coding RNAs in Colorectal Cancer; Slaby, O., Calin, G.A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-42059-2. [Google Scholar]

- Saliminejad, K.; Khorram Khorshid, H.R.; Soleymani Fard, S.; Ghaffari, S.H. An Overview of MicroRNAs: Biology, Functions, Therapeutics, and Analysis Methods. J Cell Physiol 2019, 234, 5451–5465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valinezhad Orang, A.; Safaralizadeh, R.; Kazemzadeh-Bavili, M. Mechanisms of MiRNA-Mediated Gene Regulation from Common Downregulation to MRNA-Specific Upregulation. Int J Genomics 2014, 2014, 970607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blondal, T.; Jensby Nielsen, S.; Baker, A.; Andreasen, D.; Mouritzen, P.; Wrang Teilum, M.; Dahlsveen, I.K. Assessing Sample and MiRNA Profile Quality in Serum and Plasma or Other Biofluids. Methods 2013, 59, S1–S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, J.L.; Clegg, P.D.; McGowan, C.M.; McKane S A; Chandler, K. J.; Pinchbeck, G.L. Disease Prevalence in Geriatric Horses in the United Kingdom: Veterinary Clinical Assessment of 200 Cases. Equine Vet J 2012, 44, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Weeren, P.R.; de Grauw, J.C. Pain in Osteoarthritis. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Equine Practice 2010, 26, 619–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, F.A.C.; Ali, S.A. Soluble Biomarkers in Osteoarthritis in 2022: Year in Review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2023, 31, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanciugelu, S.I.; Homorogan, C.; Selaru, C.; Patrascu, J.M.; Patrascu, J.M.; Stoica, R.; Nitusca, D.; Marian, C. Osteoarthritis and MicroRNAs: Do They Provide Novel Insights into the Pathophysiology of This Degenerative Disorder? Life 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, C.; Zampetaki, A.; Lin, N.-Y.; Kleyer, A.; Perricone, C.; Iagnocco, A.; Distler, A.; Langley, S.R.; Gelse, K.; Sesselmann, S.; et al. Signature of Circulating MicroRNAs in Osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2015, 74, e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munjal, A.; Bapat, S.; Hubbard, D.; Hunter, M.; Kolhe, R.; Fulzele, S. Advances in Molecular Biomarker for Early Diagnosis of Osteoarthritis. 2019; 10, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntoumou, E.; Tzetis, M.; Braoudaki, M.; Lambrou, G.; Poulou, M.; Malizos, K.; Stefanou, N.; Anastasopoulou, L.; Tsezou, A. Serum MicroRNA Array Analysis Identifies MiR-140-3p, MiR-33b-3p and MiR-671-3p as Potential Osteoarthritis Biomarkers Involved in Metabolic Processes. Clin Epigenetics 2017, 9, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.-H.; Tavallaee, G.; Tokar, T.; Nakamura, A.; Sundararajan, K.; Weston, A.; Sharma, A.; Mahomed, N.N.; Gandhi, R.; Jurisica, I.; et al. Identification of Synovial Fluid MicroRNA Signature in Knee Osteoarthritis: Differentiating Early- and Late-Stage Knee Osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2016, 24, 1577–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castanheira, C.; Balaskas, P.; Falls, C.; Ashraf-Kharaz, Y.; Clegg, P.; Burke, K.; Fang, Y.; Dyer, P.; Welting, T.J.M.; Peffers, M.J. Equine Synovial Fluid Small Non-Coding RNA Signatures in Early Osteoarthritis. BMC Vet Res 2021, 17, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skiöldebrand, E.; Lorenzo, P.; Zunino, L.; Rucklidge, G.J.; Sandgren, B.; Carlsten, J.; Ekman, S. Concentration of Collagen, Aggrecan and Cartilage Oligomeric Matrix Protein (COMP) in Synovial Fluid from Equine Middle Carpal Joints. Equine Vet J 2001, 33, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glyn-Jones, S.; Palmer, A.J.R.; Agricola, R.; Price, A.J.; Vincent, T.L.; Weinans, H.; Carr, A.J. Osteoarthritis. The Lancet 2015, 386, 376–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.E.; Lee, S.; Clinton, M.; Hackl, M.; Castanheira, C.; Peffers, M.J.; Taylor, S.E. Investigation of MicroRNA Biomarkers in Equine Distal Interphalangeal Joint Osteoarthritis. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Liu, W.; Qu, X.; Bi, H.; Sun, X.; Yu, Q.; Cheng, G. MiR-296-5p Inhibits IL-1β-Induced Apoptosis and Cartilage Degradation in Human Chondrocytes by Directly Targeting TGF-Β1/CTGF/P38MAPK Pathway. Cell Cycle 2020, 19, 1443–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castanheira, C.; James, V.; Taylor, S.; Skiöldebrand, E.; Clegg, P.D.; Peffers, M.J. Synovial Fluid and Serum Small Non-Coding RNA Signatures in Equine Osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2021, 29, S162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lao, T.D.; Le, T.A.H. Data Integration Reveals the Potential Biomarkers of Circulating MicroRNAs in Osteoarthritis. Diagnostics 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, L.T.T.; Swingler, T.E.; Clark, I.M. Review: The Role of MicroRNAs in Osteoarthritis and Chondrogenesis. Arthritis Rheum 2013, 65, 1963–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertusa, C.; Tarín, J.J.; Cano, A.; García-Pérez, M.Á.; Mifsut, D. Serum MicroRNAs in Osteoporotic Fracture and Osteoarthritis: A Genetic and Functional Study. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 19372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sondag, G.R.; Haqqi, T.M. The Role of MicroRNAs and Their Targets in Osteoarthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2016, 18, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, P.; Wu, Y.; Li, X.; Jia, Y. MiR-142-5p Protects against Osteoarthritis through Competing with LncRNA XIST. J Gene Med 2020, 22, e3158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Kang, S.; Pei, S.; Sang, C.; Huang, Y. MiR93-5p Inhibits Chondrocyte Apoptosis in Osteoarthritis by Targeting LncRNA CASC2. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2020, 21, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavallaee, G.; Rockel, J.S.; Lively, S.; Kapoor, M. MicroRNAs in Synovial Pathology Associated With Osteoarthritis. Front Med (Lausanne), 2020; Volume 7-2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, J.; Han, D.; Fang, Y.; Jiang, H.; Tan, X.; Xu, Z.; Wang, X.; Hong, W.; Li, T.; Wei, W. MicroRNA-10b Promotes Arthritis Development by Disrupting CD4+T Cell Subtypes. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2022, 27, 733–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woods, S.; Barter, M.J.; Elliott, H.R.; McGillivray, C.M.; Birch, M.A.; Clark, I.M.; Young, D.A. MiR-324-5p Is up Regulated in End-Stage Osteoarthritis and Regulates Indian Hedgehog Signalling by Differing Mechanisms in Human and Mouse. Matrix Biology 2019, 77, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.-M.; Meng, H.-Y.; Yuan, X.-L.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Q.-Y.; Peng, J.; Wang, A.-Y.; Lu, S.-B. MicroRNAs’ Involvement in Osteoarthritis and the Prospects for Treatments. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2015, 2015, 236179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Cheng, P.; Hu, W.; Yin, W.; Guo, F.; Chen, A.; Huang, H. Downregulated MicroRNA-340-5p Promotes Proliferation and Inhibits Apoptosis of Chondrocytes in Osteoarthritis Mice through Inhibiting the Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase Signaling Pathway by Negatively Targeting the FMOD Gene. J Cell Physiol 2019, 234, 927–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Zhai, C.; Shen, K.; Liu, G.; Liu, L.; He, J.; Chen, J.; Xu, Y. MiR-1 Inhibits the Ferroptosis of Chondrocyte by Targeting CX43 and Alleviates Osteoarthritis Progression. J Immunol Res 2023, 2023, 2061071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Hu, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, X.; He, D. CircGCN1L1 Promotes Synoviocyte Proliferation and Chondrocyte Apoptosis by Targeting MiR-330-3p and TNF-α in TMJ Osteoarthritis. Cell Death Dis 2020, 11, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, M.; Skovgaard, K.; Heegaard, P.M.H.; Fang, Y.; Kharaz, Y.A.; Bundgaard, L.; Skovgaard, L.T.; Jensen, H.E.; Andersen, P.H.; Peffers, M.J.; et al. Identification and Characterisation of Temporal Abundance of MicroRNAs in Synovial Fluid from an Experimental Equine Model of Osteoarthritis. Equine Vet J 2025, 57, 1138–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, Z.; Rasheed, N.; Al-Shobaili, H.A. Epigallocatechin-3-O-Gallate up-Regulates MicroRNA-199a-3p Expression by down-Regulating the Expression of Cyclooxygenase-2 in Stimulated Human Osteoarthritis Chondrocytes. J Cell Mol Med 2016, 20, 2241–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukai, T.; Sato, M.; Akutsu, H.; Umezawa, A.; Mochida, J. MicroRNA-199a-3p, MicroRNA-193b, and MicroRNA-320c Are Correlated to Aging and Regulate Human Cartilage Metabolism. Journal of Orthopaedic Research 2012, 30, 1915–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonk, L.A.; Kragten, A.H.M.; Dhert, W.J.A.; Saris, D.B.F.; Creemers, L.B. Overexpression of Hsa-MiR-148a Promotes Cartilage Production and Inhibits Cartilage Degradation by Osteoarthritic Chondrocytes. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2014, 22, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Liu, L.; Pan, J.; Luo, B.; Zeng, H.; Shao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Guan, H.; Guo, D.; Zeng, C.; et al. MFG-E8 Regulated by MiR-99b-5p Protects against Osteoarthritis by Targeting Chondrocyte Senescence and Macrophage Reprogramming via the NF-ΚB Pathway. Cell Death Dis 2021, 12, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de la Rica, L.; García-Gómez, A.; Comet, N.R.; Rodríguez-Ubreva, J.; Ciudad, L.; Vento-Tormo, R.; Company, C.; Álvarez-Errico, D.; García, M.; Gómez-Vaquero, C.; et al. NF-ΚB-Direct Activation of MicroRNAs with Repressive Effects on Monocyte-Specific Genes Is Critical for Osteoclast Differentiation. Genome Biol 2015, 16, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.-N.; Lu, S.; Fu, C.-M. MiR-146a Expression Profiles in Osteoarthritis in Different Tissue Sources: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. J Orthop Surg Res 2022, 17, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.W.; Watkins, G.; Le Good, N.; Roberts, S.; Murphy, C.L.; Brockbank, S.M. V; Needham, M.R.C.; Read, S.J.; Newham, P. The Identification of Differentially Expressed MicroRNA in Osteoarthritic Tissue That Modulate the Production of TNF-α and MMP13. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2009, 17, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-C.; Venø, M.T.; Chen, L.; Ditzel, N.; Le, D.Q.S.; Dillschneider, P.; Kassem, M.; Kjems, J. Global MicroRNA Profiling in Human Bone Marrow–Skeletal Stromal or Mesenchymal–Stem Cells Identified Candidates for Bone Regeneration. Molecular Therapy 2018, 26, 593–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.-F.; Zhang, S.-J.; Zhao, C.; Qiu, B.-S.; Gu, H.-F.; Hong, J.-F.; Cao, L.; Chen, Y.; Xia, B.; Bi, Q.; et al. Altered MicroRNA Expression Profile in Synovial Fluid from Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis with Treatment of Hyaluronic Acid. Mol Diagn Ther 2015, 19, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopańska, M.; Szala, D.; Czech, J.; Gabło, N.; Gargasz, K.; Trzeciak, M.; Zawlik, I.; Snela, S. MiRNA Expression in the Cartilage of Patients with Osteoarthritis. J Orthop Surg Res 2017, 12, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Min, Z.; Jiang, C.; Wang, W.; Yan, J.; Xu, P.; Xu, K.; Xu, J.; Sun, M.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Downregulation of HS6ST2 by MiR-23b-3p Enhances Matrix Degradation through P38 MAPK Pathway in Osteoarthritis. Cell Death Dis 2018, 9, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Cai, P.; Fu, W.; Wang, J.; Wei, Q.; Li, X. Downregulation of MicroRNA-23b-3p Alleviates IL-1β-Induced Injury in Chondrogenic CHON-001 Cells. Drug Des Devel Ther 2019, Volume 13, 2503–2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aird, D.; Ross, M.G.; Chen, W.-S.; Danielsson, M.; Fennell, T.; Russ, C.; Jaffe, D.B.; Nusbaum, C.; Gnirke, A. Analyzing and Minimizing PCR Amplification Bias in Illumina Sequencing Libraries. Genome Biol 2011, 12, R18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, N.; Lockwood, C.M. Pre-Analytical Variables in MiRNA Analysis. Clin Biochem 2013, 46, 861–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelli, K.; Mecocci, S.; Capomaccio, S.; Beccati, F.; Palumbo, A.R.; Tognoloni, A.; Pepe, M.; Chiaradia, E. Circulating Transcriptional Profile Modulation in Response to Metabolic Unbalance Due to Long-Term Exercise in Equine Athletes: A Pilot Study. Genes (Basel) 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.; Denham, M.M.; Spencer, S.J.; Denham, J. Exercise Regulates Shelterin Genes and MicroRNAs Implicated in Ageing in Thoroughbred Horses. Pflugers Arch 2022, 474, 1159–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Jr, G.P.; Porto, W.F.; Palu, C.C.; Pereira, L.M.; Reis, A.M.M.; Marçola, T.G.; Teixeira-Neto, A.R.; Franco, O.L.; Pereira, R.W. Effects of Endurance Racing on Horse Plasma Extracellular Particle MiRNA. Equine Vet J 2021, 53, 618–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooten, N.N.; Abdelmohsen, K.; Gorospe, M.; Ejiogu, N.; Zonderman, A.B.; Evans, M.K. MicroRNA Expression Patterns Reveal Differential Expression of Target Genes with Age. PLoS One 2010, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaskas, P.; Green, J.A.; Haqqi, T.M.; Dyer, P.; Kharaz, Y.A.; Fang, Y.; Liu, X.; Welting, T.J.M.; Peffers, M.J. Small Non-Coding RNAome of Ageing Chondrocytes. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castanheira, C.I.G.D.; Anderson, J.R.; Fang, Y.; Milner, P.I.; Goljanek-Whysall, K.; House, L.; Clegg, P.D.; Peffers, M.J. Mouse MicroRNA Signatures in Joint Ageing and Post-Traumatic Osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil Open 2021, 3, 100186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeser, R.F. The Role of Aging in the Development of Osteoarthritis. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc 2017, 128, 44–54. [Google Scholar]

- Chugh, P.; Dittmer, D.P. Potential Pitfalls in MicroRNA Profiling. WIREs RNA 2012, 3, 601–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, F.-S.; Michiels, S.; Shyr, Y.; Adjei, A.A.; Oberg, A.L. Biomarker Discovery and Validation: Statistical Considerations. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2021, 16, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diendorfer, A.; Khamina, K.; Pultar, M.; Hackl, M. MiND (MiRNA NGS Discovery Pipeline): A Small RNA-Seq Analysis Pipeline and Report Generator for MicroRNA Biomarker Discovery Studies. F1000Res 2022, 11, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewels, P.; Magnusson, M.; Lundin, S.; Käller, M. MultiQC: Summarize Analysis Results for Multiple Tools and Samples in a Single Report. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 3047–3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, M. Cutadapt Removes Adapter Sequences from High-Throughput Sequencing Reads. EMBnet J 2011, 17, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmead, B.; Trapnell, C.; Pop, M.; Salzberg, S.L. Ultrafast and Memory-Efficient Alignment of Short DNA Sequences to the Human Genome. Genome Biol 2009, 10, R25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedländer, M.R.; Mackowiak, S.D.; Li, N.; Chen, W.; Rajewsky, N. MiRDeep2 Accurately Identifies Known and Hundreds of Novel MicroRNA Genes in Seven Animal Clades. Nucleic Acids Res 2012, 40, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerbino, D.R.; Achuthan, P.; Akanni, W.; Amode, M.R.; Barrell, D.; Bhai, J.; Billis, K.; Cummins, C.; Gall, A.; Girón, C.G.; et al. Ensembl 2018. Nucleic Acids Res 2018, 46, D754–D761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths-Jones, S. The MicroRNA Registry. Nucleic Acids Res 2004, 32, D109–D111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The RNAcentral Consortium RNAcentral: A Hub of Information for Non-Coding RNA Sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, 47, D221–D229. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, M.D.; McCarthy, D.J.; Smyth, G.K. EdgeR: A Bioconductor Package for Differential Expression Analysis of Digital Gene Expression Data. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 139–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated Estimation of Fold Change and Dispersion for RNA-Seq Data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henneke, D.R.; Potter, G.D.; Kreider, J.L.; Yeates, B.F. Relationship between Condition Score, Physical Measurements and Body Fat Percentage in Mares. Equine Vet J 1983, 15, 371–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawcak, C.E.; Frisbie, D.D.; Werpy, N.M.; Park, R.D.; McIlwraith, C.W. Effects of Exercise vs Experimental Osteoarthritis on Imaging Outcomes. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2008, 16, 1519–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIlwraith, C.W.; Frisbie, D.D.; Kawcak, C.E.; Fuller, C.J.; Hurtig, M.; Cruz, A. The OARSI Histopathology Initiative – Recommendations for Histological Assessments of Osteoarthritis in the Horse. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2010, 18, S93–S105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, C.L.; Jensen, J.L.; Ørntoft, T.F. Normalization of Real-Time Quantitative Reverse Transcription-PCR Data: A Model-Based Variance Estimation Approach to Identify Genes Suited for Normalization, Applied to Bladder and Colon Cancer Data Sets. Cancer Res 2004, 64, 5245–5250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonge, D.P.; Gant, T.W. Evidence Based Housekeeping Gene Selection for MicroRNA-Sequencing (MiRNA-Seq) Studies. Toxicol Res (Camb) 2013, 2, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Control (N=4) |

OA (N=9) |

|

| Collection site, n (%) | ||

| Abattoir1 | 4 (100) | 5 (55.5) |

| Hospital2 | 0 | 4 (44.4) |

| Age, years | ||

| n | 3 | 9 |

| Mean (SD) | 6.3 (7.5) | 6.6 (3.5) |

| Min; Max | 2; 15 | 2; 14 |

| Missing | 1 | 0 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| n | 3 | 9 |

| Female | 2 (66.7) | 2 (22.2) |

| Neutered male | 1 (33.3) | 7 (77.8) |

| Missing | 1 | 0 |

| Breed, n (%) | ||

| n | 3 | 8 |

| Arab | 1 (33.3) | 0 |

| Friesian | 0 | 1 (12.5) |

| Standardbred | 1 (33.3) | 1 (12.5) |

| Swedish Warmblood | 4 (50.0) | |

| Thoroughbred | 0 | 2 (25.0) |

| Missing | 1 | 1 |

| Occupation, n (%) | ||

| n | 3 | 8 |

| Racing | 3 (100) | 8 (100.0) |

| Missing | 1 | 1 |

| OA severity, n (%)3 | ||

| n | 4 | 5 |

| Control | 4 (100.0) | 0 |

| Mild | 0 | 3 (60.0) |

| Moderate | 0 | 1 (20.0) |

| Severe | 0 | 1 (20.0) |

| Missing | 0 | 4 |

| SF collection site, n (%) | ||

| n | 4 | 9 |

| Carpal | 4 (100.0) | 6 (66.7) |

| Metacarpophalangeal | 0 | 3 (33.3) |

| miRNA | logFC1 | p-value | FDR | Significance |

| Serum | ||||

| eca-miR-9048 | -8.74 | <0.0001 | 0.0164 | Decreased in OA |

| eca-miR-143 | 4.09 | 0.0001 | 0.0164 | Increased in OA |

| eca-miR-25 | 1.99 | 0.0002 | 0.0164 | Increased in OA |

| eca-miR-146a | 2.67 | 0.0004 | 0.0242 | Increased in OA |

| eca-miR-1291a | -7.35 | 0.0007 | 0.0242 | Decreased in OA |

| eca-miR-8986b | -7.35 | 0.0007 | 0.0242 | Decreased in OA |

| eca-miR-1892 | -7.26 | 0.0008 | 0.0242 | Decreased in OA |

| eca-miR-8954 | -7.26 | 0.0008 | 0.0242 | Decreased in OA |

| eca-miR-330 | -6.93 | 0.0008 | 0.0242 | Decreased in OA |

| eca-miR-490-3p | -7.47 | 0.0008 | 0.0242 | Decreased in OA |

| eca-miR-191a | 1.76 | 0.0010 | 0.0255 | Increased in OA |

| eca-miR-345-5p | -6.91 | 0.0010 | 0.0255 | Decreased in OA |

| eca-miR-16 | 2.24 | 0.0014 | 0.0296 | Increased in OA |

| eca-miR-133a | 3.80 | 0.0014 | 0.0296 | Increased in OA |

| eca-miR-223 | 4.32 | 0.0022 | 0.0446 | Increased in OA |

| eca-miR-129b-3p | -5.60 | 0.0033 | 0.0580 | Decreased in OA |

| eca-miR-8951 | -5.60 | 0.0033 | 0.0580 | Decreased in OA |

| eca-miR-199a-3p | 2.15 | 0.0038 | 0.0597 | Increased in OA |

| eca-miR-199b-3p | 2.15 | 0.0038 | 0.0597 | Increased in OA |

| eca-miR-483 | -5.01 | 0.0049 | 0.0729 | Decreased in OA |

| eca-miR-142-5p | 1.69 | 0.0065 | 0.0935 | Increased in OA |

| eca-miR-15a | 3.61 | 0.0076 | 0.1032 | Increased in OA |

| eca-miR-148a | 1.63 | 0.0087 | 0.1094 | Increased in OA |

| eca-miR-423-5p | -1.06 | 0.0088 | 0.1094 | Decreased in OA |

| eca-miR-23b | -1.56 | 0.0106 | 0.1271 | Decreased in OA |

| eca-miR-93 | 1.77 | 0.0112 | 0.1287 | Increased in OA |

| eca-miR-744 | 2.64 | 0.0122 | 0.1351 | Increased in OA |

| eca-miR-130a | 3.42 | 0.0132 | 0.1410 | Increased in OA |

| eca-miR-8992 | -3.88 | 0.0143 | 0.1444 | Decreased in OA |

| eca-miR-8977 | -5.19 | 0.0144 | 0.1444 | Decreased in OA |

| eca-miR-423-3p | -1.12 | 0.0217 | 0.2064 | Decreased in OA |

| eca-miR-206 | 3.59 | 0.0221 | 0.2064 | Increased in OA |

| eca-miR-194 | 2.59 | 0.0227 | 0.2064 | Increased in OA |

| eca-miR-1 | 4.53 | 0.0235 | 0.2077 | Increased in OA |

| eca-let-7f | -1.31 | 0.0278 | 0.2358 | Decreased in OA |

| eca-miR-30e | 1.84 | 0.0283 | 0.2358 | Increased in OA |

| eca-miR-98 | -1.88 | 0.0292 | 0.2371 | Decreased in OA |

| eca-miR-340-5p | 2.30 | 0.0312 | 0.2464 | Increased in OA |

| eca-miR-140-3p | 4.07 | 0.0323 | 0.2482 | Increased in OA |

| eca-miR-23a | -1.24 | 0.0340 | 0.2547 | Decreased in OA |

| eca-miR-27b | 1.55 | 0.0470 | 0.3437 | Increased in OA |

| eca-miR-2483 | 3.24 | 0.0492 | 0.3465 | Increased in OA |

| eca-miR-7177b | 8.21 | 0.0497 | 0.3465 | Increased in OA |

| Synovial Fluid | ||||

| eca-miR-324-5p | -6.66 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | Decreased in OA |

| eca-miR-296 | -5.98 | <0.0001 | 0.0002 | Decreased in OA |

| eca-miR-615-5p | -9.25 | 0.0001 | 0.0072 | Decreased in OA |

| eca-miR-671-3p | -4.69 | 0.0004 | 0.0187 | Decreased in OA |

| eca-miR-27a | -4.42 | 0.0005 | 0.0187 | Decreased in OA |

| eca-miR-184 | -4.47 | 0.0006 | 0.0187 | Decreased in OA |

| eca-miR-1291a | -9.55 | 0.0006 | 0.0187 | Decreased in OA |

| eca-miR-148a | 2.45 | 0.0026 | 0.0646 | Increased in OA |

| eca-miR-423-5p | -1.90 | 0.0032 | 0.0646 | Decreased in OA |

| eca-miR-23b | -3.04 | 0.0032 | 0.0646 | Decreased in OA |

| eca-miR-598 | -7.76 | 0.0059 | 0.1090 | Decreased in OA |

| eca-miR-206 | -7.24 | 0.0075 | 0.1270 | Decreased in OA |

| eca-miR-199a-3p | 1.63 | 0.0122 | 0.1770 | Increased in OA |

| eca-miR-199b-3p | 1.63 | 0.0122 | 0.1770 | Increased in OA |

| eca-miR-31 | -6.76 | 0.0149 | 0.1950 | Decreased in OA |

| eca-miR-92b | -2.66 | 0.0153 | 0.1950 | Decreased in OA |

| eca-miR-99a | 4.81 | 0.0169 | 0.2020 | Increased in OA |

| eca-miR-1892 | -6.60 | 0.0360 | 0.3930 | Decreased in OA |

| eca-miR-10b | 0.89 | 0.0368 | 0.3930 | Increased in OA |

| eca-miR-27b | -2.15 | 0.0437 | 0.4350 | Decreased in OA |

| eca-miR-151-5p | 10.72 | 0.0465 | 0.4350 | Increased in OA |

| eca-miR-342-5p | 10.82 | 0.0480 | 0.4350 | Increased in OA |

| eca-miR-211 | 10.67 | 0.0495 | 0.4350 | Increased in OA |

| Serum | SF | |||

|

Control (N=23) |

OA (N=23) |

Control (N=44) |

OA (N=44) |

|

| Collection site, n (%) | ||||

| Abattoir1 | 0 | 0 | 39 (88.6) | 40 (90.9) |

| Hospital/Clinic2 | 23 (100) | 23 (100) | 5 (11.4) | 4 (9.1) |

| A | 23 (100) | 9 (39.1) | 0 | 0 |

| B | 0 | 5 (21.7) | 5 (100) | 4 (100) |

| C | 0 | 9 (39.1) | 0 | 0 |

| Age, years | ||||

| n | 23 | 9 | 41 | 41 |

| Mean (SD) | 9.8 (4.2) | 11.1 (5.4) | 10.2 (6.8) | 15.7 (6.7) |

| Min; Max | 3; 18 | 4; 23 | 2; 20 | 3; 25 |

| Missing | 0 | 14 | 3 | 3 |

| p-value | 0.65821 | 0.00031 | ||

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| n | 23 | 14 | 25 | 26 |

| Female | 8 (34.8) | 2 (14.3) | 17 (68.0) | 8 (30.8) |

| Neutered male | 15 (65.2) | 12 (85.7) | 8 (32.0) | 181 (69.2) |

| p-value | 0.26032 | 0.02272 | ||

| Missing | 0 | 9 | 19 | 18 |

| Body Condition Score, n (%) | ||||

| n | 23 | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| 1–3 | 0 | 0 | – | – |

| 4 | 0 | 1 (11.1) | – | – |

| 5 | 19 (82.6) | 6 (66.6) | – | – |

| 6 | 3 (13.0) | 2 (22.2) | – | – |

| 7 | 1 (4.3) | 0 | – | – |

| 8–9 | 0 | 0 | – | – |

| Missing | 0 | 14 | 44 | 44 |

| Breed, n (%) | ||||

| n | 233 | 233 | 194 | 164 |

| Appaloosa | 0 | 1 (4.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Cob5 | 1 (4.3) | 0 | 2 (10.5) | 1 (6.3) |

| Connemara5 | 4 (17.4) | 1 (4.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Dales5 | 0 | 1 (4.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Dutch Warmblood | 0 | 1 (4.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Hanoverian | 0 | 2 (8.7) | 0 | 0 |

| Holsteiner | 0 | 1 (4.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Irish cob | 0 | 1 (4.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Irish Draught | 2 (8.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Irish Sport Horse5 | 9 (39.1) | 4 (17.4) | 2 (10.5) | 3 (18.8) |

| Lusitano | 1 (4.3) | 0 | 0 | 1 (6.3) |

| Pony | 1 (4.3) | 1 (4.3) | 4 (21.4) | 0 |

| Thoroughbred5 | 2 (8.7) | 9 (39.1) | 7 (36.8) | 9 (56.3) |

| Warmblood5 | 1 (4.3) | 0 | 0 | 2 (12.5) |

| Welsh Pony/Cob5 | 2 (8.7) | 1 (4.3) | 4 (21.4) | 0 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 25 | 25 |

| Occupation, n (%)3 | ||||

| n | 23 | 18 | 0 | 0 |

| Not in work (out in the field’) | 2 (8.7) | 2 (11.1) | – | – |

| All-rounder | 5 (21.7) | 1 (5.6) | – | – |

| Dressage | 1 (4.3) | 0 | – | – |

| Eventing | 2 (8.7) | 0 | – | – |

| Hacking | 5 (21.7) | 32 (16.5) | – | – |

| Hunting | 3 (13.0) | 1 (5.6) | – | – |

| Leisure | 1 (4.3) | 0 | – | – |

| Racing | 0 | 9 (50.0) | – | – |

| Schooling | 4 (17.4) | 1 (5.6) | – | – |

| Showjumping | 0 | 1 (5.6) | – | – |

| Missing | 0 | 5 | 44 | 44 |

|

Current level of work (0–3), n (%)5 |

||||

| n | 23 | 18 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 (‘out in the field’) | 2 (8.7) | 2 (11.1) | – | – |

| 1 (‘light work’) | 12 (52.2) | 4 (22.2) | – | – |

| 2 (‘medium work’) | 7 (30.4) | 2 (11.1) | – | – |

| 3 (‘intense work’) | 2 (8.7) | 10 (55.6) | – | – |

| Missing | 0 | 10 | 44 | 44 |

| p-value | 0.02146 | – | ||

| Shoes, n (%) | ||||

| n | 18 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| All four feet | 13 (72.2) | 3 (37.5) | n/a | n/a |

| Front feet | 2 (11.1) | 1 (12.5) | n/a | n/a |

| Unshod | 3 (16.7) | 4 (50.0) | n/a | n/a |

| Missing | 5 | 15 | 44 | 44 |

| Joints affected, n (%)7,8 | ||||

| Distal interphalangeal | – | 2 (9.1)3 | 0 | 0 |

| Intervertebral | – | 2 (9.1) | 0 | 0 |

| Metacarpophalangeal | – | 7 (31.8)3 | 44 (100)8 | 44 (100)8 |

| Metatarsophalangeal | – | 4 (18.1)3 | 0 | 0 |

| Sacroiliac | – | 2 (9.1)3 | 0 | 0 |

| Scapulohumeral | – | 1 (4.5)3 | 0 | 0 |

| Tarsometatarsal | – | 2 (9.1)3 | 0 | 0 |

| Front limb9 | – | 2 (9.1)3 | 0 | 0 |

| Joint gross score, n (%)10 | ||||

| n | 0 | 0 | 44 | 44 |

| 0 | – | – | 21 (47.7) | 0 |

| 1 | – | – | 23 (52.3) | 0 |

| 2 | – | – | 0 | 10 (22.7) |

| 3 | – | – | 0 | 16 (36.4) |

| 4 | – | – | 0 | 11 (25.0) |

| 5 | – | – | 0 | 4 (9.1) |

| 6 | – | – | 0 | 2 (4.5) |

| 7 | – | – | 0 | 1 (2.3) |

| 8–9 | – | – | 0 | 0 |

| Mean (SD) | – | – | 0.5 (0.5) | 3.4 (1.2) |

| Min; Max | – | – | 0; 1 | 2; 7 |

| p-value | – | <0.00016 | ||

| Missing | 23 | 23 | 0 | 0 |

|

Articular cartilage microscopic score, n (%)11 |

||||

| n | 0 | 0 | 34 | 30 |

| 0 | – | – | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | – | – | 5 (14.7) | 0 |

| 2 | – | – | 8 (23.5) | 5 (16.7) |

| 3 | – | – | 7 (20.6) | 4 (13.3) |

| 4 | – | – | 9 (26.5) | 5 (16.7) |

| 5 | – | – | 2 (5.9) | 5 (16.7) |

| 6 | – | – | 1 (2.9) | 5 (16.7) |

| 7 | – | – | 1 (2.9) | 4 (13.3) |

| 8 | – | – | 1 (2.9) | 1 (3.3) |

| 9–15 | – | – | 0 | 0 |

| 16 | – | – | 0 | 1 (3.3) |

| 17–20 | – | – | 0 | 0 |

| Mean (SD) | – | – | 3.2 (1.7) | 5.0 (2.9) |

| Min; Max | – | – | 1; 8 | 2; 16 |

| p-value | – | 0.00156 | ||

| Missing | 23 | 23 | 10 | 14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).