1. Introduction

Rabies virus (RABV) belongs to the genus

Lyssavirus, family

Rhabdoviridae [

1,

2]. It is a single-negative-stranded RNA virus with a genome of approximately 12,000 nucleotides. Its structure mainly comprises the G, M, P and L proteins, together with the N protein and the viral RNA encapsulated by N protein [

3,

4].

RABV is a zoonotic pathogen; infected animals such as cats and dogs can transmit the virus to humans through bites. Cases have been reported in more than 150 countries, and the disease is almost 100 % fatal. Rabies causes an estimated 59,000 deaths annually, about 40 % of which are children under 14 years of age. Although no curative treatment exists, both pre-exposure prophylaxis and timely post-exposure vaccination are highly effective. Consequently, rabies vaccines are central to disease prevention [

5,

6].

Current vaccines are mainly inactivated vaccines (INVs) produced in chicken embryos, hamster kidney cells, human diploid cells and Vero cells [

7]. Their main drawbacks are low productivity and modest immunogenicity, necessitating three doses for pre-exposure and four or five doses for post-exposure regimens [

5]. To overcome these limitations, several groups have developed next-generation candidates. Recombinant G protein or G + M virus-like particles (VLPs) have been successfully produced in yeast, HEK-293, BHK-21, CHO, insect and even plant cells [

8,

9,

10]; however, additional research and technological advances are required before these vaccines can be licensed, and some fail to provide complete protection [

9]. More efficacious rabies vaccines are therefore urgently needed. Advances in mRNA technology have spawned novel rabies mRNA vaccines, most of which focus on the RABV G protein [

11,

12,

13,

14].

The RABV N-protein sequence is highly conserved across strains, it represents an excellent target for cross-protective immunity. During infection it is abundantly expressed, efficiently processed through both MHC-I and MHC-II pathways, and activates CD4⁺ and CD8⁺ T cells while promoting IFN-γ release. Inclusion of N protein thus broadens antigenic coverage, enhances the durability of cellular immunity and provides an additional barrier against escape mutations in the surface G protein [

15,

16].

In this study we designed a composite-structured vaccine in which mRNA encoding the G protein (G-mRNA) of RABV (RABV-G) and recombinant N protein of RABV (RABV-N) expressed in

Escherichia coli (

E. coli) are co-encapsulated within dual-cationic lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) to form a viral nucleocapsid-like nanostructure (NLS) vaccine. Assembly of this architecture was achieved with our proprietary dual-cationic LNP platform composed of two cationic lipids—DOTAP-Cl and DHA-1—together with the helper lipids mPEG-DTA-2K-1 and DOPC [

17,

18].

Compared with the G-mRNA vaccine and INV, the NLS vaccine elicits significantly stronger humoral and cellular immune responses. Seven days after a single dose, the NLS vaccine elicited neutralizing antibody titers of ~10 IU mL

-1—20-fold the internationally accepted protective threshold of 0.5 IU mL

-1 [

7]—and induced an adaptive immune response post the secondary immunization with 1,000 IU ml

-1 of neutralizing antibody and obvious specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) response, which showed more potent than either G-mRNA vaccine or INV. Following two doses on days 0 and 21, 100 % of mice survived challenge with 25 LD₅₀ of RABV fixed strain at day 14 post-boost.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cells

HEK-293T and BSR cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM; ThermoFisher Scientific Gibco) supplemented with 10 % (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone, Cytiva) and 1% (v/v) penicillin–streptomycin (100 U mL⁻¹ penicillin, 100 μg mL⁻¹ streptomycin).

2.2. Viruses

RABV challenge virus standard (CVS) strains CVS-11 and CVS-24 were kindly provided by Professor Zhongpeng Zhao of Shandong University. The CVS-24 strain was propagated in the brains of 3-week-old (10–12 g) SPF BALB/c mice, whereas the CVS-11 strain was propagated in BSR cells.

2.3. Animals

Except for CVS-24 virus propagation, which was performed in 3-week-old BALB/c mice, all other experiments were conducted using four- to five-week-old female SPF BALB/c and KM mice. Immunizations were given by hind-limb intramuscular injection, and euthanasia was performed by CO₂ asphyxiation.

Ethics approval:All procedures of animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Shandong WeigaoLitong Biological Products Co., Ltd (approval number LACUC-RD-2024-010).

2.4. Construction of the Recombinant Template Plasmid

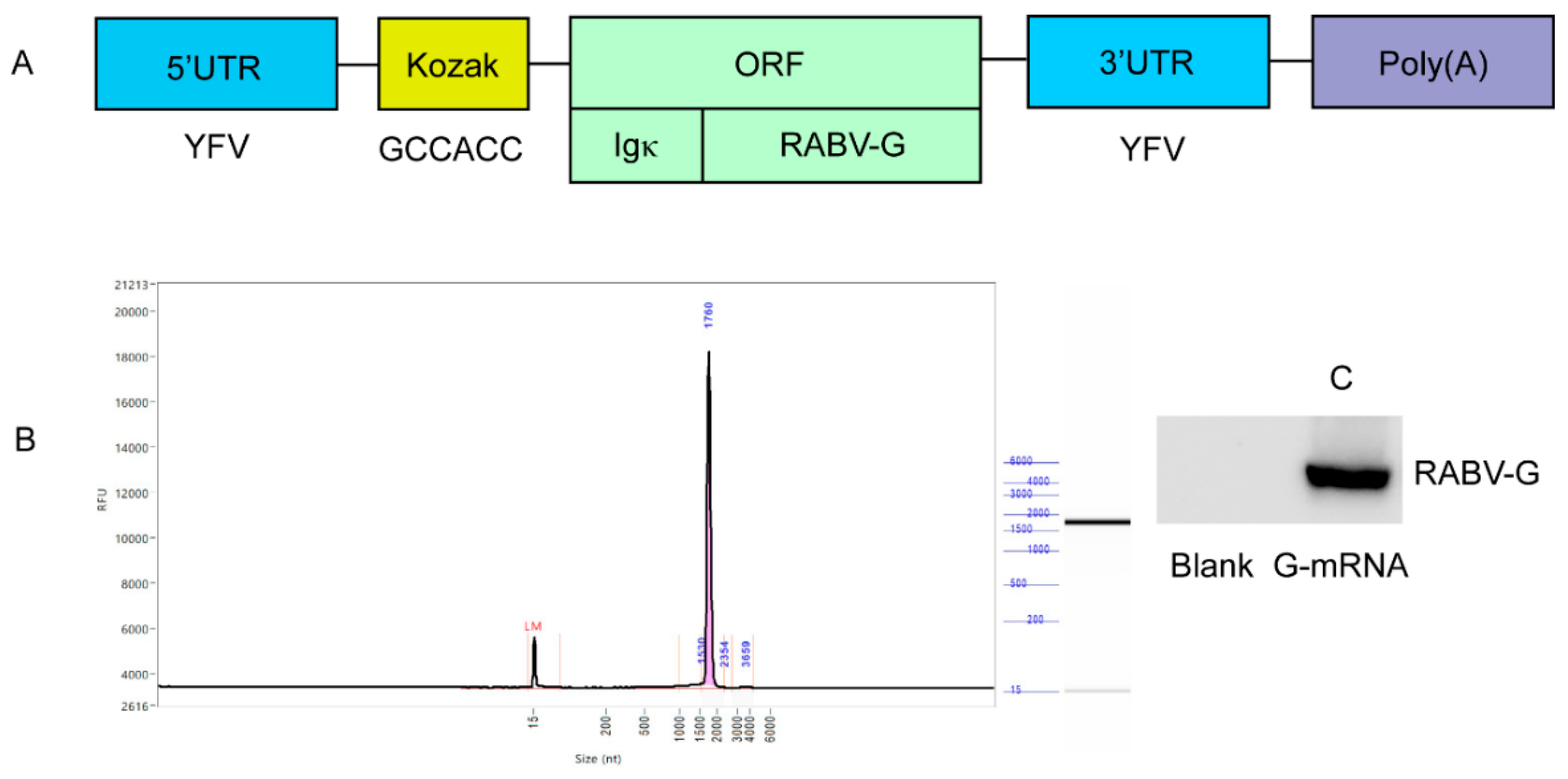

To generate the G-mRNA template plasmid, the following elements (

Table A1) were inserted between the Hind III and Bam H I sites of the pVAX1 vector: the 5′-untranslated region (UTR) from flavivirus, the Ig κ secretory signal, a Kozak sequence, the RABV-G open reading frame (ORF), the 3′-UTR from flavivirus, and a poly(A) tail.

2.5. In Vitro Transcription (IVT)

Linearize the plasmid with Bam H I (NEB) and use it as template for IVT with T7 RNA polymerase. The 20 μL reaction mixture contains: 2 μL T7 CleanCap Reagent AG Reaction Buffer (10×; NEB), 2 μL ATP (60 mM; NEB), 2 μL GTP (50 mM; NEB), 1 μL N1-Me-pUTP (100 mM; Synthgene), 2 μL CTP (50 mM; NEB), 2 μL CleanCap Reagent AG (40 mM; NEB), 1 μg linearized DNA template, 2 μL T7 RNA Polymerase Mix (NEB), and nuclease-free water to 20 μL. Incubate the mixture at 37 °C for 2 h, then add 2 μL DNase I (NEB) and incubate at 37 °C for 15 min to remove the DNA template, yielding the G-mRNA.

2.6. 293T Cells Transfection

Transfect 293T cells with G-mRNA using transfection reagent Lipomaster 2000 (Vazyme). For each well of a 6-well plate, combine 2.5 μg G-mRNA with 5 μL Lipomaster 2000 according to the manufacturer’s instructions; include wells treated with transfection reagent alone as blank controls.

2.7. SDS-PAGE and Coomassie Brilliant Blue (CBB) Staining

SDS-PAGE was carried out using a Bis-Tris SurePAGE pre-cast gel (4–20 %; GeneScript). Samples were diluted in 4× LDS Sample Buffer (GeneScrip), heated at 95 °C for 5 min, and loaded together with the protein ladder (10–200 kDa; BioSharp). Electrophoresis was run in 1× Tris-MOPS-SDS running buffer (GeneScript) at 180 V for 50 min. After electrophoresis, the gel is soaked in CBB R-250 staining solution for 30 min, then destained overnight to visualize protein bands.

2.8. Western Blotting (WB)

Proteins were separated on 4–20 % Bis-Tris gels and electro-transferred to 0.22 µm PVDF membranes (Merck). After blocking with 5 % non-fat dry milk in TBST for 1 h at room temperature, membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies diluted in 5 % BSA-TBST. Following three 15-min washes with TBST, HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:10 000) were applied for 1 h at room temperature. Immunoreactive bands were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) and imaged with a ChemiDoc system.

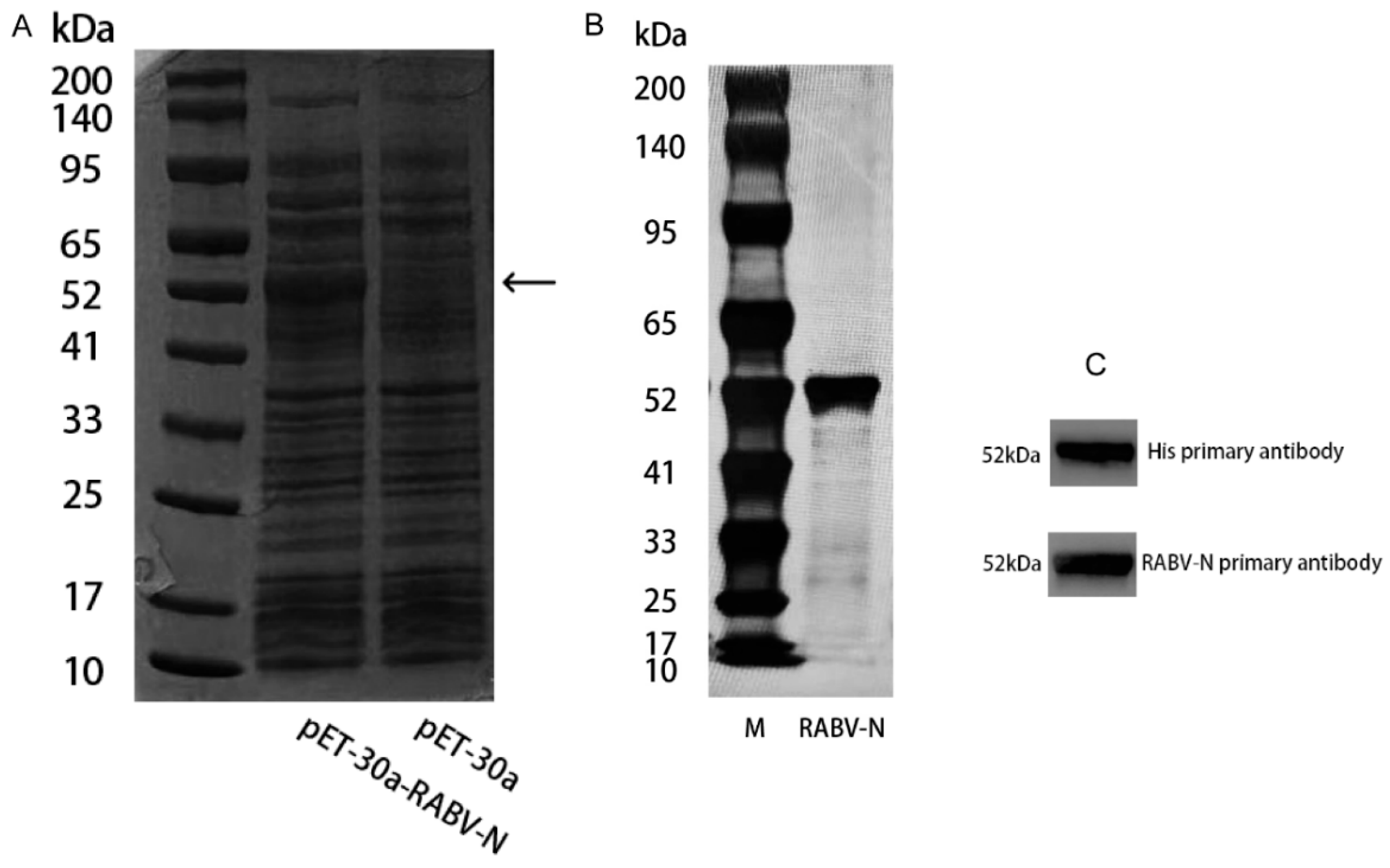

2.9. Recombinant Expressed of RABV-N

Insert the 6×His-tag sequence and the nucleotide sequence encoding the RABV-N (

Table A2) into the pET30a vector to generate the recombinant plasmid pET30a-RABV-N. Transform this plasmid into BL21(DE3) competent

E. coli, select single colonies, and perform fermentation. When the culture reaches an OD₆₀₀ of 0.8, add IPTG to a final concentration of 0.1 mM and induce expression at 16 °C for 24 h. Harvest and lyse the cells, and remove debris by centrifugation. Purify the recombinant RABV-N from the clarified supernatant by His-tag affinity chromatography.

2.10. LNP and Encapsulation

The LNPs consist of four lipid components—DHA-1, DOTAP-Cl, DOPC, and mPEG-DTA-1-2K—at a molar ratio of 36–40 % : 6–10 % : 16–20 % : 0.8–1.2 %, together with 1.0–1.4 % Span 85 and 0.4–0.6 % Tween-80 [

18]. An aqueous phase is prepared by mixing G-mRNA with recombinant RABV-N at a mass ratio of 4 : 1. The pre-formulated lipid phase and aqueous phase are homogenized to generate LNPs at a flow-rate ratio (FRR) of 1 : 3. The resulting nanoparticles are diluted 30- to 35-fold in a buffer containing 10 mM sodium acetate and 0.001 % trehalose (pH 6.4), concentrated through a 100 kDa membrane, and then re-diluted into a solution of 20 mM sodium acetate, 0.01 % trehalose, and 3.5 % sucrose. After sterile filtration, the novel RABV NLS vaccine is obtained.

2.11. Quality Control of LNP Vaccine

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) was employed to determine the particle size, polydispersity index (PDI) and zeta potential of the mRNA-LNP formulations. Samples were diluted 1:50 in 0.1× PBS (pH 7.4) to a final RNA concentration of ~0.1 mg mL⁻¹ and measured at 25 °C using a Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern, UK). For size and PDI, the instrument was operated in back-scatter mode (173°), collecting three consecutive runs of 12 sub-runs each; data were analyzed by the cumulants algorithm and are reported as intensity-weighted mean diameter ± SD. Zeta potential was determined by laser Doppler electrophoresis at 80 V with the Smoluchowski model; each value represents the average of three independent measurements (n = 3).

2.12. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

RABV-G and RABV-N specific IgG levels were quantified using ELISA kits (ACRO Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Serum samples subjected to two-fold serial dilution in kit diluent were added in duplicate and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. After three washes with supplied PBST, 100 µL HRP-conjugated anti-species IgG detection antibody was added for 45 min at 37 °C. Wells were washed again, developed with 100 µL TMB substrate for 10 min, and the reaction was stopped with 50 µL 1 M H₂SO₄. Absorbance was read at 450 nm (630 nm reference). Endpoint titers were reported as geometric mean titers (GMT) ± 95 % CI.

2.13. Rapid Fluorescent Focus Inhibition Test (RFFIT)

RFFIT was performed according to the WHO standard protocol. Briefly, 50 μL of two-fold serially diluted serum (starting at 1:10) was mixed with 50 μL of challenge virus (CVS-11, ~100 TCID₅₀) and incubated for 90 min at 37 °C in 96-well plates. Next, 1.5 × 10⁴ BSR cells in 100 μL complete DMEM were added per well and plates were incubated for 20 h at 37 °C, 5 % CO₂. After fixation with 80 % acetone, foci were stained with fluorescein-conjugated anti-rabies nucleoprotein antibody (1:200, Fujirebio) for 1 h at 37 °C and counted under a fluorescence microscope. Neutralizing antibody titers were calculated as the reciprocal of the highest dilution reducing focus numbers by ≥ 50 % relative to virus control. Each plate included virus control, cell control and reference serum control; tests were run in duplicate and results expressed as GMT ± 95 % CI.

2.14. Enzyme-Linked Immunospot Assay (ELISPOT)

ELISPOT was carried out with mouse IFN-γ pre-coated plates (Mabtech). Splenocytes (2 × 10⁵ per well) were seeded in duplicate and stimulated with 5 μg mL⁻¹ RABV-G and RABV-N peptide pool, ConA (2 μg mL⁻¹, positive) or medium alone (negative) in 100 μL complete RPMI-1640. After 20 h incubation (37 °C, 5 % CO₂), cells were discarded and plates were developed sequentially with biotinylated anti-IFN-γ, streptavidin–ALP and BCIP/NBT substrate according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Spots were counted with an ImmunoSpot reader using identical sensitivity settings; data are presented as spot-forming units (SFU) per 10⁶ cells after subtraction of background (< 5 SFU). A positive response was defined as ≥ 2 × background and ≥ 50 SFU 10⁶ cells-1.

2.15. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR)

As previously described, RABV loads in tissues were determined by qPCR with absolute quantification, and cytokine expression by relative qPCR, using GAPDH as the internal reference (primers: GAPDH-F, AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG; GAPDH-R, TGTAGACCATGTAGTTGAGGTCA) [

17].

2.16. Data Statistics and Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS and GraphPad Prism software. In significance testing, "ns" denotes no significant difference, * indicates p ≤ 0.05, ** indicates p ≤ 0.01, *** indicates p ≤ 0.001, and **** indicates p ≤ 0.0001.

3. Results

3.1. Preparation of G-mRNA of RABV

The recombinant template plasmid pVAX-RABV-G, which enables in-vitro transcription of G-mRNA, was successfully constructed. The inserted elements—5′ UTR, Kozak sequence, Ig-κ leader, RABV-G ORF, 3′ UTR and poly(A) tail—are shown in

Figure 1A. The plasmid was linearized with BamH I and used as the template for G-mRNA synthesis. IVT with T7 RNA polymerase yielded G-mRNA of >95 % purity (

Figure 1B). G-mRNA was transfected into 293T cells; 24 h later, cell lysates were prepared and RABV-G was assessed by WB. Robust expression of RABV-G was clearly detected (

Figure 1C).

3.2. Expression and Purification of RABV-N in E. coli

The RABV-N was induced and expressed in

E. coli. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 2000 rpm and 4 °C for 20 min, washed three times with PBS buffer (pH 7.4), resuspended, and disrupted by sonication. The supernatant of the bacterial lysate was collected after centrifugation at 10,000 rpm and 4 °C for 30 min and then analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by CBB staining. Compared with the blank control, a distinct band corresponding to RABV-N was observed at 52 kDa (

Figure 2A). The supernatant was subjected to His-tag affinity chromatography, yielding recombinant RABV-N with a purity of >90 % (

Figure 2B). Purified RABV-N protein was analyzed by WB using both anti-His and anti-N primary antibodies, each yielding a single specific band (

Figure 2C).

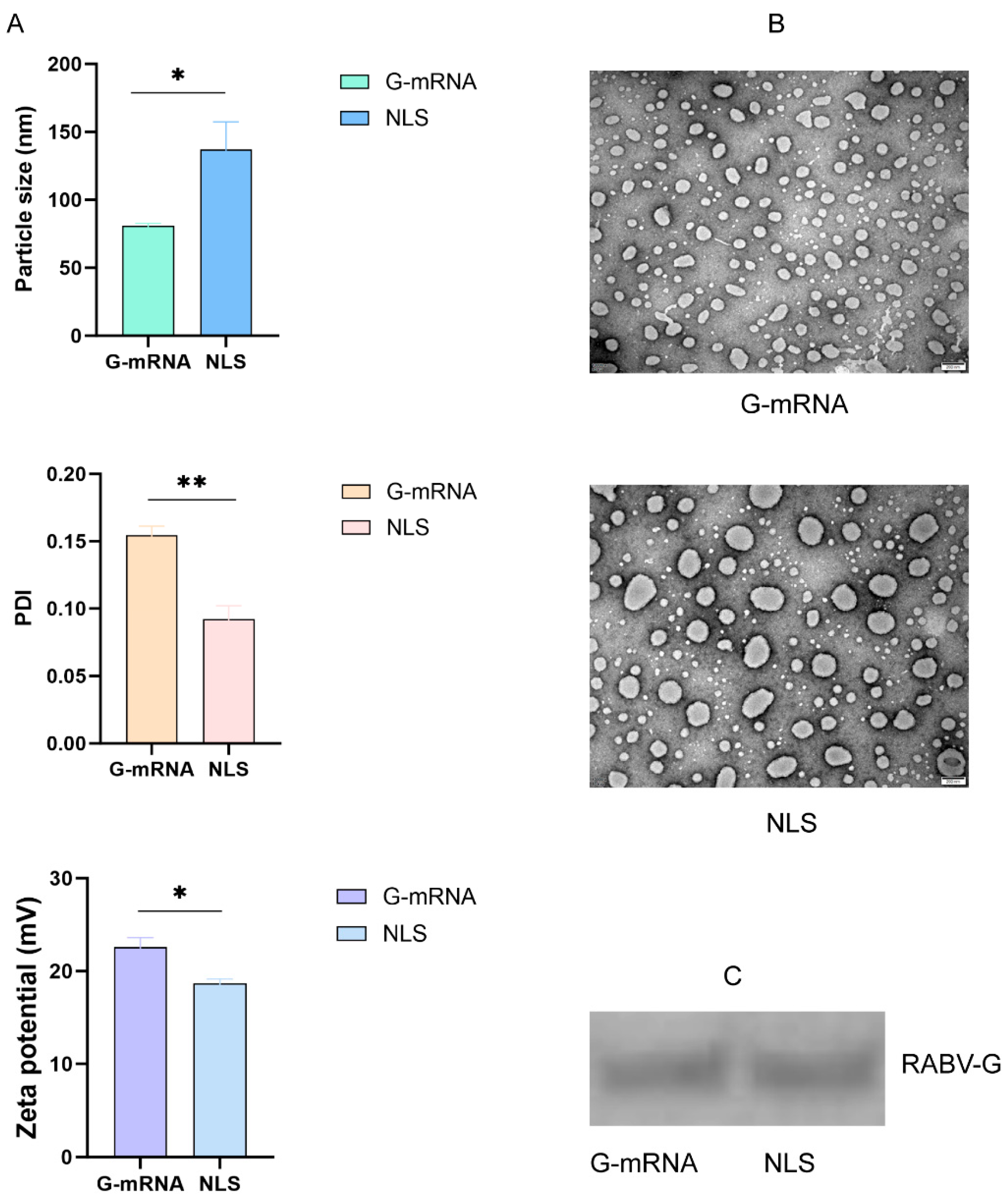

3.3 Quality-Control Data for the G-mRNA Vaccine and NLS Vaccine of RABV Encapsulated in LNPs

The encapsulated RABV G-mRNA vaccine and NLS vaccine were systematically characterized for morphology, encapsulation efficiency, particle size, PDI, and zeta potential by negative-staining transmission electron microscopy combined with RiboGreen fluorescence assay and DLS. The results showed that both vaccines achieved an encapsulation efficiency of over 95%. In addition, the NLS vaccine exhibited a significantly larger particle size (136.9 nm vs 80.9 nm), a lower PDI (0.09 vs 0.15), and a smaller zeta potential (18.7 mV vs 22.6 mV) compared with the G-mRNA vaccine (

Figure 3A). Electron microscopy revealed that both the G-mRNA and NLS vaccines formed uniformly sized LNPs; however, the NLS vaccine particles were noticeably larger (

Figure 3B). Both vaccines were used to transfect 293T cells; after 24 h, cell lysates were harvested and analyzed by WB, revealing a single, highly expressed band (

Figure 3C).

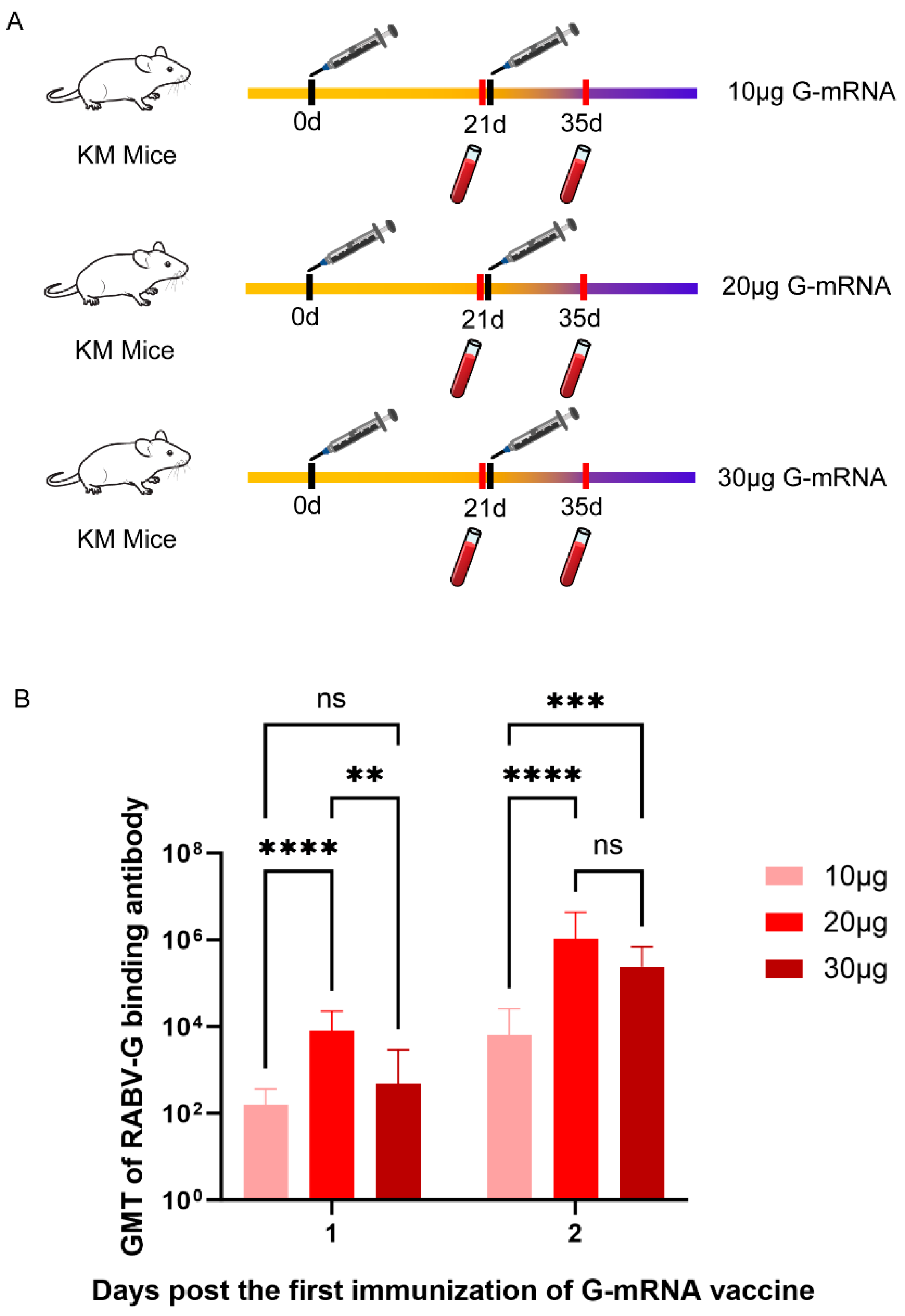

3.4 Determination of RABV G-mRNA Vaccine Immunization Dose

To determine the optimal G-mRNA dose for the vaccine, three groups of KM mice (n = 5 per group) were immunized on days 0 and 21 with 10, 20, or 30 μg of G-mRNA. Serums were collected on days 21 and 35 after the first immunization, and the RABV-G binding antibody titers in serum were determined by ELISA (

Figure 4A). GMT were derived from ELISA read-outs and calculated after log-transformation of individual concentrations. Inter-group comparison of the three doses (10 μg, 20 μg and 30 μg) showed that, on day 21 after the first immunization, the serum binding antibody titers in the 20 μg group was significantly higher than that in both the 10 μg and 30 μg groups, whereas no significant difference was observed between the 10 μg and 30 μg groups. By day 35 post-prime, the 20 μg and 30 μg groups exhibited significantly higher titers than the 10 μg group, while the difference between the 20 μg and 30 μg groups remained non-significant (

Figure 4B).

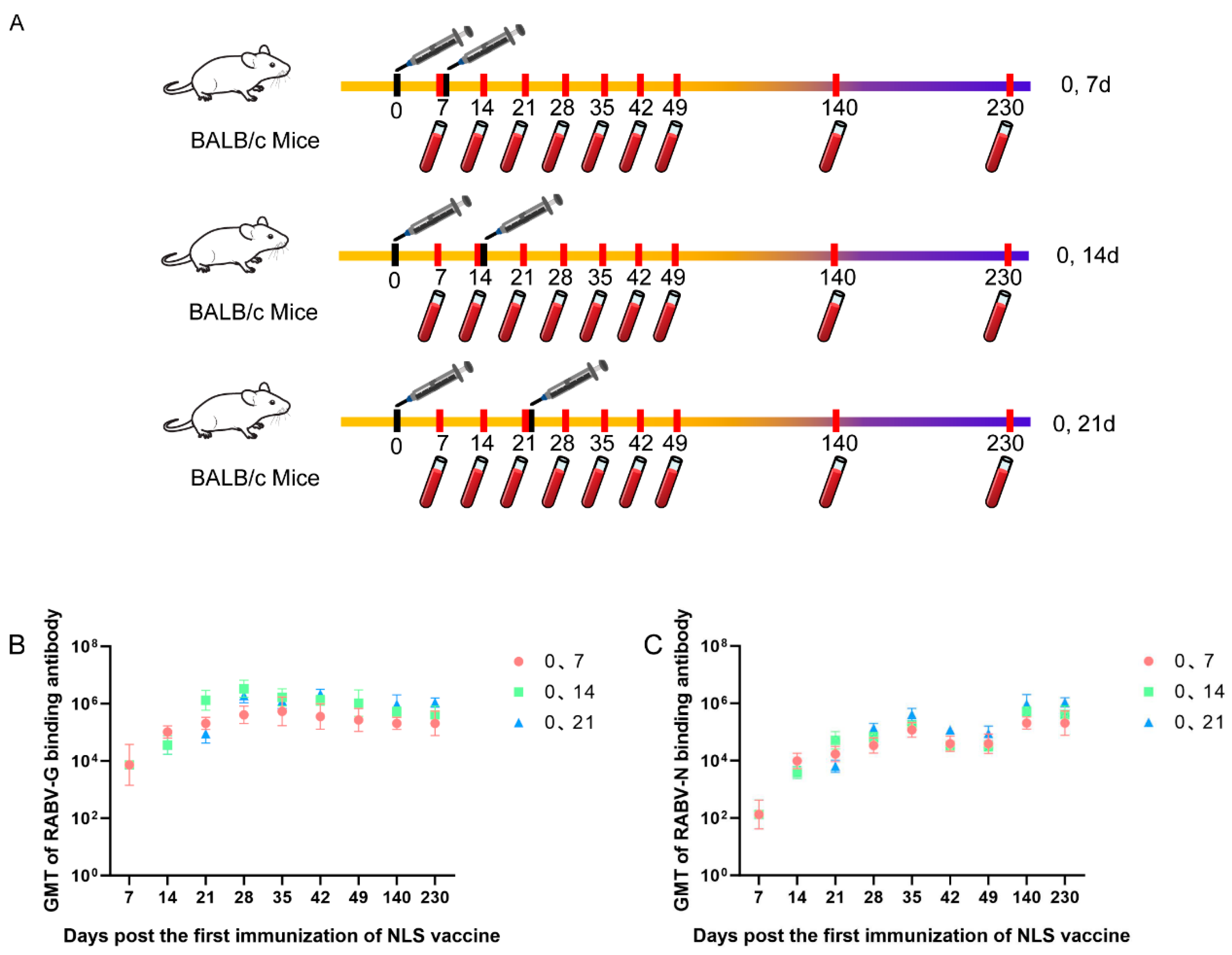

3.5. Dynamic Variation of Humoral Immune Response of RABV-G and RABV-N Induced in Different Immunization Schedules of RABV NLS Vaccine

Three groups of BALB/c mice (n = 5 per group) were immunized twice according to different schedules: days 0 and 7, days 0 and 14, or days 0 and 21. Serums were collected on days 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, 42, 49, 140 and 230. RABV-G and RABV-N binding antibody titers were measured by ELISA (

Figure 5A). The results show that the 0, 7-day schedule elicits RABV-G and RABV-N antibody titers more rapidly, whereas the 0, 21-day schedule induces the highest titers; the 0, 14-day schedule falls between the two. Consequently, for pre-exposure prophylaxis the 0, 21-day regimen is preferable, while for post-exposure prophylaxis the 0, 7-day regimen should be chosen to accelerate the immune response (

Figure 5 B & C).

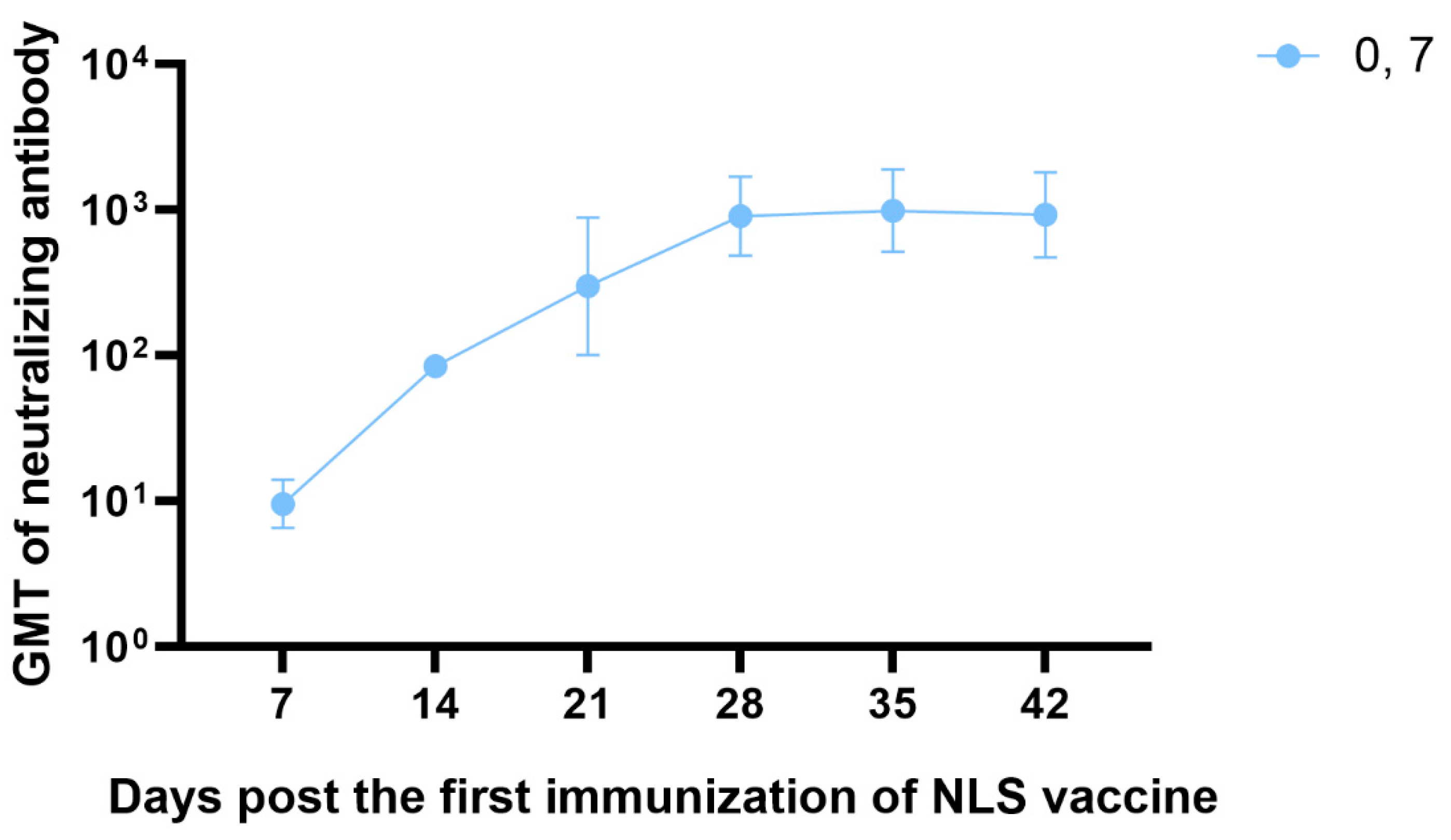

3.6. The Neutralizing Antibody Titration of RABV NLS Vaccine Detected by RFFIT

Neutralizing antibody levels against RABV at or above 0.5 IU mL

-1, as determined by RFFIT, are accepted as proof of sufficient immune response and are associated with protective immunity in both humans and animals[

7]. We therefore immunized BALB/c mice (n = 3) with a two-dose regimen on days 0 and 7, and the kinetics of neutralizing antibody titers of day 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, 42 were measured by the RFFIT. The results showed that 7 days after a single dose of the NLS vaccine, neutralizing antibody titers reached approximately 10 IU mL

-1—20-fold higher than the 0.5 IU mL

-1 threshold recognized by the WHO as protective. 7 days after the second dose (day 14 post-prime), neutralizing antibody titers rose to 85 IU mL

-1, and the peak titer after the two-dose course reached 1,000 IU mL

-1 (

Figure 6).

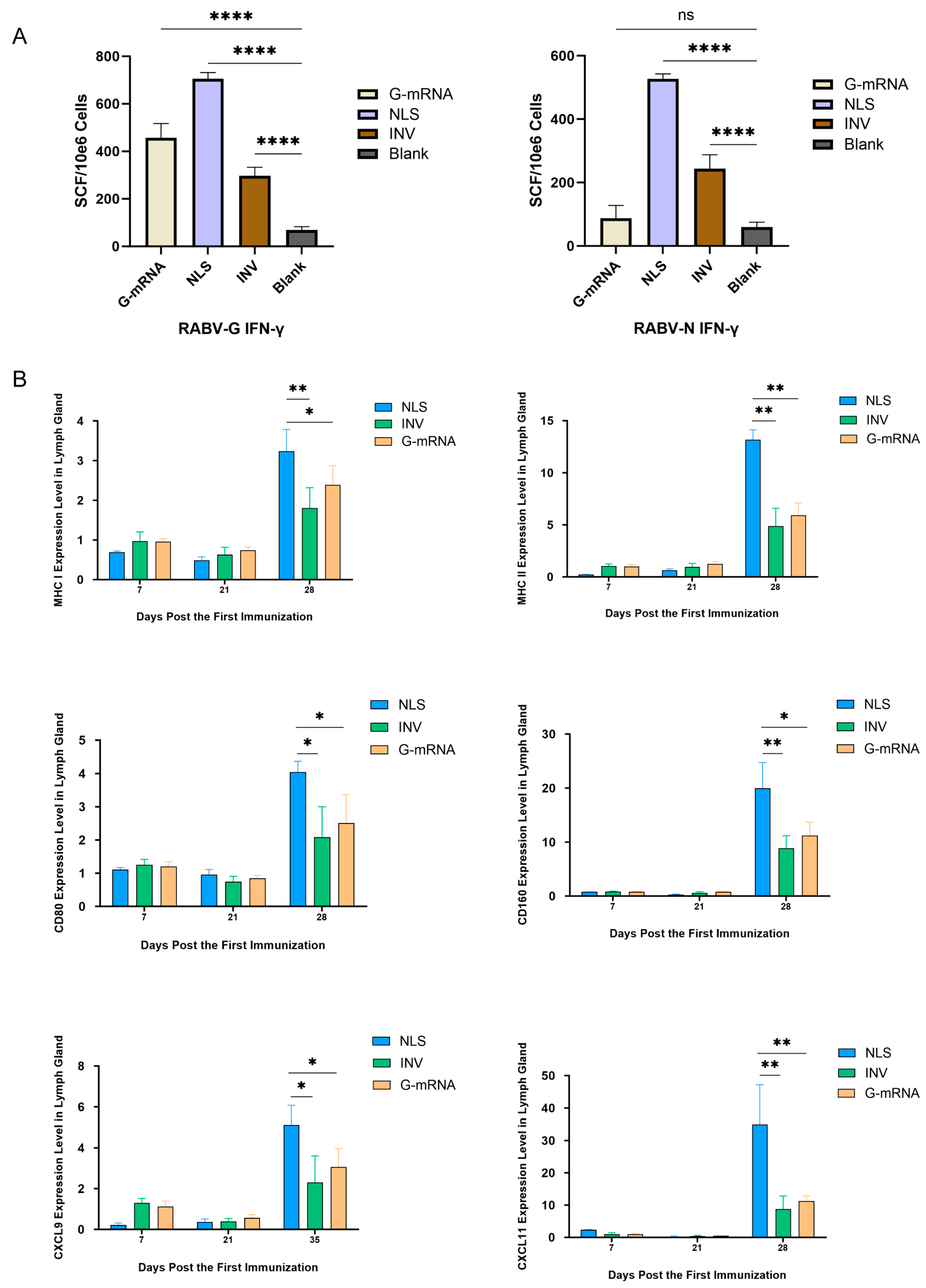

3.7. Specific CTL Response Profiling Elicited by RABV NLS Vaccine, G-mRNA Vaccine and INV

To evaluate the strength of vaccine-induced specific CTL responses, 4 groups (n = 5 each) of BALB/c mice were used. Animals in the G-mRNA and NLS groups received two immunizations on days 0 and 21, whereas the INV group was immunized three times on days 0, 7 and 21; the blank control group received empty LNP only on days 0 and 21. All mice were euthanized on day 7 after the last dose, spleens were aseptically removed and splenocytes were isolated. Antigen-specific IFN-γ-secreting T cells were enumerated by ELISpot. The results showed that, for the G antigen, NLS elicited the strongest specific response, followed by the G-mRNA vaccine, while INV induced a comparatively weaker reaction (

Figure 7A). Regarding the N antigen, the G-mRNA group—lacking N RABV-N component—showed the lowest response; NLS again produced the highest reactivity, and INV fell between the two (

Figure 7A).

To compare cellular immunity activation elicited by the NLS vaccine, INV and G-mRNA vaccine, three groups of BALB/c mice (n = 3) received different vaccine types and immunization schedules. Mice in the G-mRNA and NLS groups received two immunizations on days 0 and 21, whereas the INV group was immunized three times on days 0, 7 and 21. Lymph nodes were harvested on days 7, 21 and 28 post the first immunization, and expression of MHC-I, MHC-II, CXCL9, CXCL11, CD80 and CD160 was quantified by qPCR. Results showed that on day 28 (i.e. 7 days after the boost), all six genes were expressed at significantly higher levels in the NLS-vaccinated group than in the INV and G-mRNA vaccinated groups (

Figure 7B).

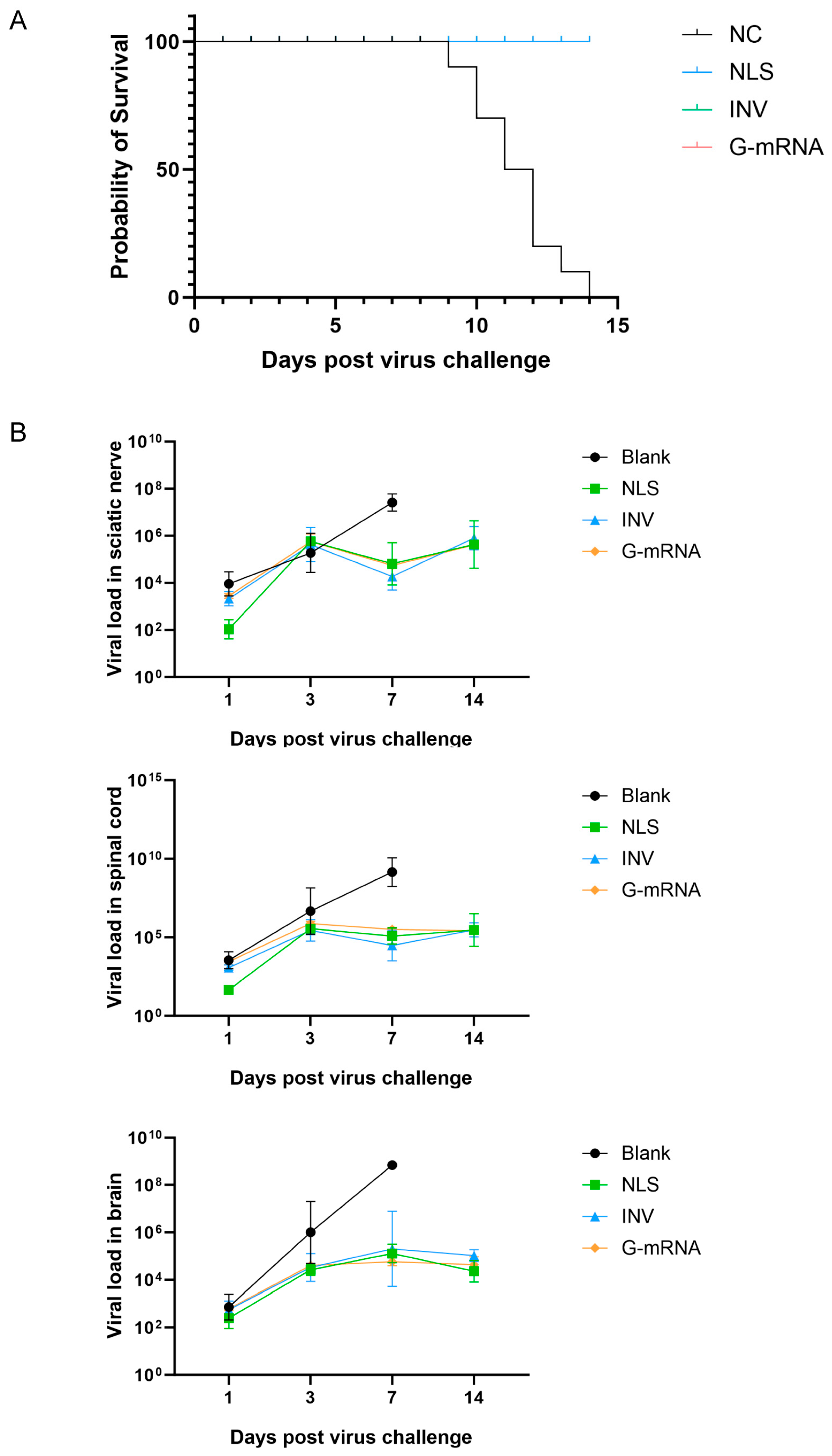

3.8. CVS-24 Strain Challenge Protection Assay

Four groups of KM mice (n=22 per group, 10 mice per group were used for the challenge protection test, and 12 for the viral load kinetics assay.) received injections according to the following schedules: the NLS vaccine and G-mRNA vaccine groups were given two doses on days 0 and 21; the INV group received three doses on days 0, 7 and 21; and the blank control group was administered empty LNPs. On day 35 after the first immunization, all mice were challenged intramuscularly with 25 LD₅₀ of RABV CVS-24. Survival was monitored daily. The results showed that the NLS vaccine, INV and G-mRNA vaccine group conferred 100 % protection to mice, while all animals in the blank control group died between days 9 and 14 post-challenge (

Figure 8A).

After virus challenge, three mice per group were euthanized on days 1, 3, 7, and 14. Sciatic nerve, spinal cord and brain were collected, total RNA was extracted, and viral load was quantified by qPCR. Results showed that viral loads in the three tissues did not differ significantly at 1 and 3 days post-challenge. On day 7, however, the blank control group had markedly higher viral loads in all three tissues than the NLS vaccine, INV and G-mRNA vaccine groups. By day 14, all animals in the blank control group had died, whereas all mice in the NLS vaccine, INV and G-mRNA vaccine groups survived and displayed no appreciable change in viral load in the three tissues (

Figure 8B).

4. Discussion

Our previous study suggested that dual-cationic lipids formulation can not only encapsulate mRNA alone but also simultaneously entrap both mRNA and protein, or allow protein to be anchored on the LNP surface after mRNA loading[

17,

18]. Based on this proprietary dual-cationic lipid technology, we designed the rabies NLS vaccine, which is no longer a simple G-mRNA vaccine but a novel modal that co-encapsulates G-mRNA together with the RABV-N.

This design is based on two rationales. First, the G protein is the principal antigen of RABV; in addition to eliciting specific neutralizing antibodies, it effectively induces robust T-cell immunity. RABV-N is one of the most conserved structural proteins across members of the

Lyssavirus genus, with >90 % amino-acid identity among classical RABV strains[

19,

20,

21], therefore, the T-cell immunity induced by RABV-N is conserved across different strains. Second, following NLS vaccine entry into the cell, the recombinant RABV-N is processed by the proteasome into peptides that are loaded onto surface MHC-I molecules, thereby activating CD8⁺ CTLs[

22,

23]. Additionally, antigen-presenting cells such as dendritic cells and macrophages internalize RABV-N and present RABV-N-derived peptides on MHC-II, triggering CD4⁺ Th cell responses[

24,

25,

26]. Our experiments demonstrate that the NLS vaccine containing N protein elicits markedly stronger T-cell responses than the G-mRNA-only vaccine lacking N protein. The role of the N protein in adaptive immunity has also been demonstrated in the study by Tombari et al.[

27].

Beyond neutralizing antibodies that block viral entry, the CD8⁺ CTL response is indispensable for clearing infected cells, controlling viral spread and can provide long-term protective immunity[

22]. Upon recognition of viral peptides presented by MHC-I molecules, CTLs exert two parallel antiviral mechanisms: One is cytolytic activity – release of perforin and granzyme to induce apoptosis of infected cells, preventing progeny virus production; the other is non-cytolytic suppression – secretion of IFN-γ and TNF-α, which inhibit viral gene expression and prime neighboring cells into an antiviral state. Conversely, viruses that down-regulate MHC-I or generate CTL escape mutations achieve persistence, underscoring that a robust CTL arm is as essential as neutralizing antibodies for durable protection. Thus, next-generation vaccines should deliberately harness both arms of adaptive immunity to maximize efficacy.

CD4⁺ T cells are the master helpers of vaccine immunity. After priming, they differentiate into specialized subsets that drive clonal expansion of CD8⁺ cytotoxic T lymphocytes, B-cell affinity maturation, and long-lived antibody production. Without this help, both primary CD8⁺ responses and humoral memory are severely reduced, whereas their presence correlates with durable protection after vaccination[

28].

In this study, we measured the expression levels of MHC-I and CD160—molecules linked to CTL responses—after the second NLS vaccine dose. Both were significantly higher than in the INV group, indicating that NLS elicits a more robust CTL reaction. Expression of MHC-II (associated with CD4⁺ T cells) and CD80 (involved in both CD4⁺ and CTL activation) was also elevated relative to the INV, demonstrating that NLS induces a stronger CD4⁺ T-cell response as well.

CXCL9 and CXCL11 are IFN-γ–inducible chemokines that act through CXCR3 to orchestrate adaptive immunity. Both create a chemotactic gradient that draws CXCR3⁺ naïve/activated Th1 cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes from the blood into draining lymph nodes and peripheral tissues, ensuring that effector cells reach the antigen depot. In addition, persistent CXCL9/11 signaling during the expansion phase favors differentiation of central-memory CD4⁺ and CD8⁺ T cells; CXCR3-deficient mice exhibit fewer memory precursors and weaker recall responses after booster doses[

29,

30,

31].

In this study we also measured the vaccine-induced expression of CXCL9 and CXCL11. Both chemokines remained significantly higher 7 days after the second NLS dose than after INV, implying that more memory-precursor cells are being generated or re-activated, thereby laying the groundwork for longer-lasting protection.

Certainly, the NLS vaccine also has its drawbacks. First, while mRNA vaccines are characterized by a short development cycle, the addition of a recombinant protein to construct the NLS formulation prolongs this timeline. Second, the inclusion of the recombinant protein introduces extra quality-control items and increases analytical complexity. Nevertheless, for rabies vaccines—where conventional products already exist—in our view, the additional time required to achieve superior immunogenicity is worthwhile.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q. Li and Z. Zhang; formal analysis, W. Chang and Y. Wang; investigation, Z. Zhang, J. Zhang, C. Mu, K. Ma, D. Gao, C. Liu, L. Feng, X. Peng, J. Si, H. Li, Y. Su, F. Zeng, L. He, A. Wang, C. Zhou, Z. Zhang, Q. Li, J. Li, M. Sun, X. Yu, J. Li, L. Wang, Y. Li, H. Yi, L. Zheng, F. He; writing—original draft preparation, Z. Zhang, J. Zhang and S. Zou; writing—review and editing, Q. Li; project administration, Z. Zhang, J. Zhang, S. Zou, H. Li and M. Xing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Professor Zhongpeng Zhao of Shandong University for providing RABV CVS strain.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| RABV |

Rabies virus |

| VLP |

virus-like particle |

| G-mRNA |

mRNA encoding the G protein |

| RABV-G |

G protein of rabies virus |

| RABV-N |

N protein of rabies virus |

| LNP |

lipid nanoparticle |

| NLS |

nucleocapsid-like nanostructure |

| CTL |

cytotoxic T lymphocyte |

| DMEM |

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium |

| FBS |

fetal bovine serum |

| CVS |

challenge virus standard |

| CBB |

Coomassie brilliant blue |

| WB |

Western blotting |

| UTR |

untranslated region |

| ORF |

open reading frame |

| IVT |

in vitro transcription |

| ECL |

enhanced chemiluminescence |

| FRR |

flow-rate ratio |

| DLS |

dynamic light scattering |

| PDI |

polydispersity index |

| ELISA |

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| GMT |

geometric mean titers |

| RFFIT |

rapid fluorescent focus inhibition test |

| ELISPOT |

enzyme-linked immunospot assay |

| SFU |

spot-forming units |

| qPCR |

quantitative real-time PCR |

| INV |

inactivated vaccine |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Composition of the G-mRNA template.

Table A1.

Composition of the G-mRNA template.

| Sequence name |

Sequence length (bp/AA) |

Sequence |

| 5′-UTR from flavivirus |

118 |

agtaaatcctgtgtgctaattgaggtgcattggtctgcaaatcgagttgctaggcaataaacacatttggattaattttaatcgttcgttgagcgattagcagagaactgaccagaac |

| Kozak |

6 |

gccacc |

| Igκ secretory signal |

21 |

METDTLLLWVLLLWVPGSTGD |

| G protein ORF |

439 |

KFPIYTIPDKLGPWSPIDIHHLSCPNNLVVEDEGCTNLSGFSYMELKVGYISAIKVNGFTCTGVVTEAETYTNFVGYVTTTFKRKHFRPTPDACRSAYNWKMAGDPRYEESLHNPYPDYHWLRTVKTTKESVVIISPSVADLDPYDKSLHSRVFPRGKCSGITVSSAYCSTNHDYTIWMPENPRLGTSCDIFTNSRGKRASKGSKTCGFVDERGLYKSLKGACKLKLCGVLGLRLMDGTWVAIQTSNETKWCPPDQLVNLHDFHSDEIEHLVVEELVKKREECLDALESIMTTKSVSFRRLSHLRKLVPGFGKAYTIFNKTLMEADAHYKSVRTWNEIIPSKGCLRVGGRCHPHVNGVFFNGIILGPDGHVLIPEMQSSLLQQHMELLESSVIPLMHPLADPSTVFKDGDEVEDFVEVHLPDVHKQVSGVDLGLPNWGK |

| 3′-UTR from flavivirus |

123 |

gacactgttccaagcaacaaccaagaactagaccttgtacataggacaaaactgaaaccgggataaaaaccacggatggagaaccggactccacacatcaaacagaagaggatgtcagcccag |

| Poly(A) tail |

138 |

aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaagcatatgactaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaccgcgtgctgaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa |

Table A2.

RABV-N sequence.

Table A2.

RABV-N sequence.

| Sequence name |

Sequence length (AA) |

Amino Acid Sequence |

| 6×His Tag |

6 |

HHHHHH |

| N-protein |

449 |

DADKIVFKVNNQVVSLKPEIIVDQYEYKYPAIKDLKKPCITLGKAPDLNKAYKSVLSGMNAAKLDPDDVCSYLAAAMQFFEGTCPEDWTSYGILIARKGDRITPNSLVEIKRTDVEGNWALTGGMELTRDPTVSEHASLVGLLLSLYRLSKISGQNTGNYKTNIADRIEQIFETAPFVKIVEHHTLMTTHKMCANWSTIPNFRFLAGTYDMFFSRIEHLYSAIRVGTVVTAYEDCSGLVSFTGFIKQINLTAREAILYFFHKNFEEEIRRMFEPGQETAVPHSYFIHFRSLGLSGKSPYSSNAVGHVFNLIHFVGCYMGQVRSLNATVIAACAPHEMSVLGGYLGEEFFGKGTFERRFFRDEKELQEYEAAELTKSDVALADDGTVNSDDEDYFSGETRSPEAVYTRIMMNGGRLKRSHIRRYVSVSSNHQARPNSFAEFLNKTYSNDS |

References

- Fooks, A.R., et al., Rabies. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 2017. 3: p. 17091.

- Rupprecht, C.E. and R. Chikwamba, Rabies and Related Lyssaviruses, in Prospects of Plant-Based Vaccines in Veterinary Medicine, J. MacDonald, Editor. 2018, Springer International Publishing AG. p. 45-87.

- Xu, H., et al., Real-time Imaging of Rabies Virus Entry into Living Vero cells. Scientific Reports, 2015. 5: p. 11753. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.-H. and L. Xing, The roles of rabies virus structural proteins in immune evasion and implications for vaccine development. Canadian Journal of Microbiology, 2024. 70(11): p. 461-469. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-J., et al., Infection and Prevention of Rabies Viruses. Microorganisms, 2025. 13. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A., et al., Canine rabies: An epidemiological significance, pathogenesis, diagnosis, prevention, and public health issues. Comparative Immunology, Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 2023. 97.

- WHO, WHO Expert Consultation on Rabies Third Report. 2018. p. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Lemos, M.A., et al., Rabies virus glycoprotein expression in Drosophila S2 cells. I: design of expression/selection vectors, subpopulations selection and influence of sodium butyrate and culture medium on protein expression. J Biotechnol, 2009. 143(2): p. 103-10. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., X. Huang, and X. Yang, Rabies virus-like particles comprised of G and M proteins protect BALB_c mice from lethal dose challenging. Journal of Applied Virology, 2015. 4(2): p. 14-29. [CrossRef]

- Fooks, A.R., A.C. Banyard, and H.C.J. Ertl, New human rabies vaccines in the pipeline. Vaccine, 2019. 37 Suppl 1: p. A140-A145. [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, C., et al., Proof-of-concept of a low-dose unmodified mRNA-based rabies vaccine formulated with lipid nanoparticles in human volunteers: A phase 1 trial. Vaccine, 2021. 39(8): p. 1310-1318. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., et al., An mRNA-based rabies vaccine induces strong protective immune responses in mice and dogs. Virology Journal, 2022. 19: p. 184. [CrossRef]

- Hongtu, Q., et al., Immunogenicity of rabies virus G mRNA formulated with lipid nanoparticles and nucleic acid immunostimulators in mice. Vaccine, 2023. 41(48): p. 7129-7137. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Z., P. Yu, and W. Zhu, Development of mRNA rabies vaccines. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 2024. 20(1). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales-Martínez, M.E., et al., Immunologic importance of the N protein in the rabies virus infection. Veterinaria México, 2006. 37(3): p. 351-367.

- Masatani, T., et al., Rabies Virus Nucleoprotein Functions To Evade Activation of the RIG-I-Mediated Antiviral Response. Journal of Virology, 2010. 84(8): p. 4002-4012. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., et al., Virus-like structures for combination antigen protein mRNA vaccination. Nature Nanotechnology, 2024. 19(8): p. 1224-1233. [CrossRef]

- Qihan Li, et al., Lipid Ddlivery System and VirusI-like Structure (VLS) Vaccine Constructed Therefrom. 2024: United States.

- Nevers, Q., et al., Properties of rabies virus phosphoprotein and nucleoprotein biocondensates formed in vitro and in cellulo. PLoS Pathog, 2022. 18(12): p. e1011022. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P., et al., Exposed nucleoprotein inside rabies virus particle as an ideal target for real-time quantitative evaluation of rabies virus particle integrity in vaccine quality control. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 2025. 19(5).

- Luo, M., J.R. Terrell, and S.A. McManus, Nucleocapsid Structure of Negative Strand RNA Virus. Viruses, 2020. 12(8). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reina-Campos, M., N.E. Scharping, and A.W. Goldrath, CD8+ T cell metabolism in infection and cancer. Nature Reviews Immunology, 2021. 21(11): p. 718-738. [CrossRef]

- Knörck, A., et al., Cytotoxic Efficiency of Human CD8+ T Cell Memory Subtypes. Frontiers in Immunology, 2022. 13. [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, A. and T. Saito, CD4 CTL, a Cytotoxic Subset of CD4+ T Cells, Their Differentiation and Function. Frontiers in Immunology, 2017. 8. [CrossRef]

- Hoeks, C., et al., When Helpers Go Above and Beyond: Development and Characterization of Cytotoxic CD4+ T Cells. Frontiers in Immunology, 2022. 13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofland, T., et al., CD4+ T cell memory is impaired by species-specific cytotoxic differentiation, but not by TCF-1 loss. Frontiers in Immunology, 2023. 14. [CrossRef]

- Tombari, W., et al., A novel mRNA-based multi-epitope vaccine for rabies virus computationally designed via reverse vaccinology and immunoinformatics. Scientific Reports, 2025. 15: p. 30355. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ura, T., et al., Current Vaccine Platforms in Enhancing T-Cell Response. Vaccines, 2022. 10(8). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.K., et al., Expression of chemokine receptor CXCR3 on T cells affects the balance between effector and memory CD8 T-cell generation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2011. 108(21). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabău, G., et al., Long-Lasting Enhanced Cytokine Responses Following SARS-CoV-2 BNT162b2 mRNA Vaccination. Vaccines, 2024. 12(7). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Ewijk, C.E., et al., Innate immune response after BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccination associates with reactogenicity. Vaccine: X, 2025. 22.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).