1. Introduction

In 1998, Swedo and colleagues first described a subgroup of prepubertal children exhibiting acute-onset obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) and/or tic disorder symptoms (Swedo et al., 1998). The timing of these neuropsychi- atric symptoms, coinciding with a recent Group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus (GABHS) infection, suggested an autoimmune origin, in which the postinfectious immune response mistakenly targeted the brain. This condition was subsequently termed pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections, otherwise known as PANDAS (Snider & Swedo, 2004).

PANDAS is diagnosed according to five clinical characteristics: (1) the presence of OCD and/or a tic disorder, (2) onset between the age of 3 and puberty, (3) temporal association with a GABHS infection, (4) association with neurological abnormalities (e.g., motor hyperactivity, choreiform movements), and (5) sudden onset (Swedo et al., 1998). Symptoms can also include behavioral regression, emotional lability, loss of motor skills, and food restrictions. These symptoms follow a relapsing-remitting pattern in which they disappear or decrease in severity for extended periods before returning with the same or heightened intensity (Swedo et al., 1998).

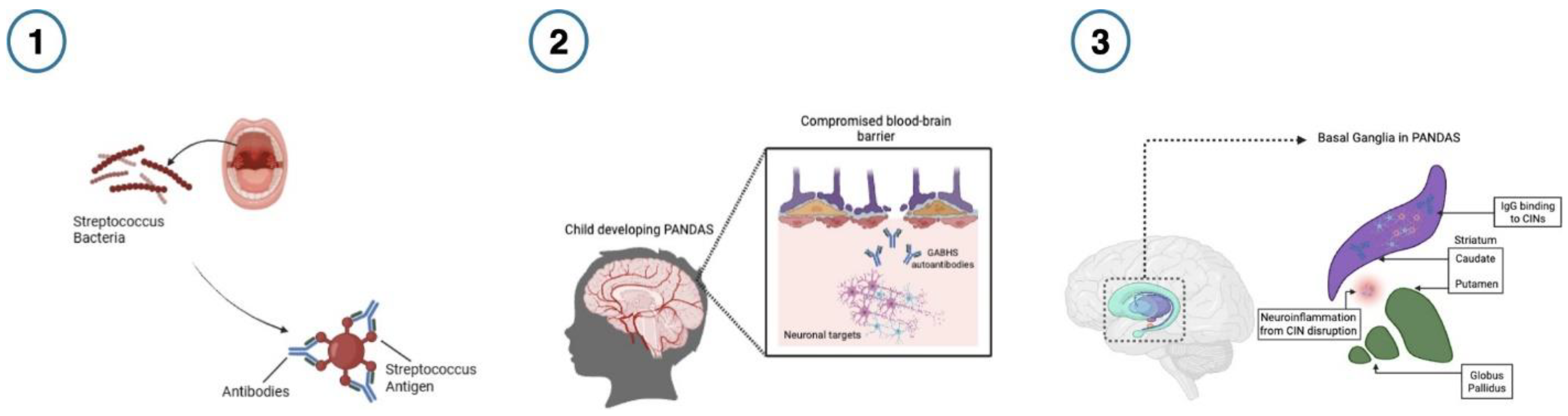

Though the pathophysiology of PANDAS is still under investigation, a leading theory argues that molecular mimicry is central to its pathogenesis (Singer & Loiselle, 2003). In this model, streptococcal antigens prompt the host immune system to generate antibodies to combat infection (see

Figure 1. ). Due to structural similarities between antigens and neuronal proteins, when these antibodies enter the brain through a compromised blood-brain barrier, they mistakenly cross-react with neuronal targets (e.g., dopamine receptors), interfere with neuronal signaling, and precipitate the symptoms associated with PANDAS (Arcilla & Singla, 2024). This captures some of the etiology of PANDAS (Snider & Swedo, 2004), and aligns with reports of neuroinflammation (Frick et al., 2016), basal ganglia abnormalities (La Bella et al., 2023), and the presence of anti-basal ganglia antibodies (Singer et al., 2004). Treatment for PANDAS involves management of the active infection, standard psychiatric interventions for OCD/tics, antibiotics, and immunomodulatory therapies. Evidence for these interventions is mixed, access is limited, and patient responses are heterogeneous, complicating prognosis (W Tang et al., 2021).

Currently, PANDAS is diagnosed through psychiatric evaluation, which does not address the biological etiology of the disorder. Moreover, there are no biological diagnostic markers that distinguish PANDAS from neuropsychiatric (e.g., OCD, Tourette) or rheumatological disorders (Martino et al., 2005). Given the diagnostic challenges and prognostic variability, there is a need for robust, reproducible biomarkers to aid diagnosis, stratify risk, and guide treatment. The development of biomarkers for PANDAS has the potential to help distinguish the prognoses for patients (Gromark et al., 2021). Data from neuroimaging and immunological studies can illuminate potential biomarkers and provide direction for refining the diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of PANDAS.

Figure 1.

The progression of autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS).

Figure 1.

The progression of autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS).

- 1)

When Group A -hemolytic streptococcal (GABHS) infection is present, the host produces antibodies to fight infection.

- 2)

GABHS infection weakens the blood-brain barrier, allowing host antibodies to enter the brain and mistakenly cross-react with neuronal proteins due to the structural similarities between the streptococcal antigens and neuronal proteins (Arcilla & Singla, 2024). 3) Preferential binding of immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies to basal ganglia cholinergic interneurons (CINs) in PANDAS causes symptom flare-up in the relapsing stage of PANDAS. This improper binding disrupts CIN activity, which in turn leads to neuroinflammation and worsening neuropsychiatric symptoms. Treatment with immunoglobulin can improve symptoms, which is associated with resolved elevated CIN binding (Xu et al., 2021). Figure created in Biorender.

1.1. Methods

A literature search was conducted in PubMed for articles published between 1997 and 2025 using the search terms "pediatric acuteonset autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections" and "PANDAS." Studies referring to pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorder (PANS) were also considered, as patients may meet all criteria for PANDAS, but do not exhibit a close temporal relationship with the preceding streptococcal infection at the time of diagnosis (Swedo et al., 2012). Articles were included if they met diagnostic criteria for PANS/PANDAS and were available in English. Additionally, the reference lists of included studies and relevant review articles were considered to identify further eligible publications.

2. Results

Several articles (n=27) were identified that met the defined criteria. We examined these reported biomarkers across two major categories. First, we review neuroimaging studies, which provide insight into the structural and functional alterations in the brain. Next, we discuss immunological markers, including antibody profiles, cytokines, and other immunerelated findings implicated in the disorders. This structure is intended to guide the reader through the diverse biomarker domains relative to PANS/PANDAS.

2.1. Neuroimaging Markers

Across magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies, a recurrent observation is the alteration of basal ganglia size in PANDAS subjects relative to healthy controls (Prato et al., 2021). For example, using computer-assisted morphometric analyses of MRI scans, Giedd et al. (2000) compared brain volumes in 34 PANDAS patients and found size differences in several basal ganglia structures, specifically 8% for the caudate, 5% for the putamen, and 7% for globus pallidus. No associations emerged between basal ganglia size and symptom severity (Giedd et al., 2000).

Taking a different approach, Cabrera and colleagues applied voxel-based morphometry (VBM) and multivoxel pattern analysis (MVPA) to assess whether differences in gray and white matter patterns found in the cortex, subcortex, and cerebellum of PANDAS patients could be used to distinguish PANDAS patients from healthy controls. VBM produced a statistical map reflecting the probability of increased or decreased grey and white matter tissue between groups. The VBM analysis results were used as inputs for MVPA, a machine learning algorithm that uses information from the gray and white matter tissue to train a classifier that can assign class-conditional probabilities based on information carried by an image voxel. The classifier assigns to the participant data the probability of either belonging to a PANDAS patient or healthy control; the accuracy of the classifier reflects the ability to assign subjects to their correct group, the sensitivity reflects the probability of being correctly classified as a patient, and the specificity reflects the probability of being correctly classified as a control. This analysis found that the classifier had an overall 75% accuracy (sensitivity = 78.56%; specificity = 71.43%) for gray matter tissue in the study sample (Cabrera et al., 2018). Although not yet sufficient for diagnosis, these results suggest the potential diagnostic utility of MRI data using classification algorithms pending replication, external validation, and assessment across scanners and cohorts.

Another neuroimaging technique used to examine neuroanatomical differences in PANDAS patients is positron emission tomography (PET). Kumar et al. (2014) used PET imaging with 11C-[R]-PK11195 (PK), a ligand that binds to the translocator protein (TSPO), to evaluate immune-related dysfunction in PANDAS patients. TSPO is expressed by activated microglia, a class of brain cells that act as immune receptor cells and regulate brain development, injury repair, and neuronal network maintenance (Colonna & Butovsky, 2017). This study involved 17 children with PANDAS, 12 with Tourette syndrome, and 15 healthy adults. The PK binding potential values, a measure expressed by activated microglia, were increased in the bilateral caudate and bilateral lentiform nucleus of PANDAS patients compared to healthy subjects (Kumar et al., 2014). Conversely, the Tourette syndrome group exhibited increased PK binding in the bilateral caudate only compared to the control group. Comparing PANDAS and Tourette syndrome groups, there was increased binding potential in the bilateral caudate and the lentiform nucleus in PANDAS than in the non-PANDAS Tourette cohort. In a follow-up analysis, the authors also reported an inverse relationship between PK binding potential in the basal ganglia and duration of illness in PANDAS. Additionally, a reduction in PK binding potential was found in the PANDAS patients following intravenous immunoglobulin G (IVIG) treatment in all but one patient. Together, the PET imaging and MRI studies reveal a pattern of neuroinflammation and structural differences in the basal ganglia of PANDAS patients.

2.1. Immunological Markers

Beyond imaging markers, studies using patient serum, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and plasma from PANS/PANDAS patients have identified potential immunological markers that could contribute to our understanding of the disorder’s etiology and aid in more effective diagnostic processes.

One of the earliest studies designed to evaluate immunological markers for PANDAS examined the presence of elevated D8/17 expression in PANDAS patients (Swedo et al., 1997). The D8/17 antigen, a cell-surface marker found on B lymphocytes, is a known genetic marker for rheumatic fever susceptibility. In this study, authors found that 85% of PANDAS patients were D8/17 positive compared to only 17% of healthy children. However, 89% of children with Sydenham chorea – a neuropsychiatric manifestation of rheumatic fever – were D8/17 positive. The mean number of D8/17 positive cells in patient groups was higher than in the healthy comparison group (Swedo et al., 1997). The presence of D8/17-positive cells has been reported in at least two subsequent studies in patients with childhood-onset OCD (Murphy et al., 1997) and tic disorders (Hoekstra et al., 2001). The frequency of this marker in broader pediatric OCD and tic disorders along with the high rates in Sydenham chorea suggest limited specificity of D8/17 as a marker for PANDAS.

To address specificity, more recent work has investigated the role of immunological factors on neuronal targets in line with the molecular mimicry hypothesis and basal ganglia alterations observed in neuroimaging studies. Researchers have focused on the binding of PANDAS-associated antibodies to specific cell types in the basal ganglia (Xu et al.,2024) (Frick et al., 2018). For instance, Xu and colleagues examined the binding of the immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies to striatal interneurons after infusion of sera from PANDAS patients into the brains of mice in vivo. In comparison to a control group, they reported elevated IgG binding to CINs (See

Figure 1), but not to other striatal neurons (Xu et al., 2024). In a follow-up study within the broader PANS population, the same group observed elevated binding of patient IgG antibodies to CINs. Moreover, using patient plasma taken during symptom flare-up, results showed decreased CIN activity due to IgG binding relative to control samples (Xu et al., 2024). As reduced IgG binding has been linked with symptom improvement after IVIG treatment (Xu et al., 2021), the presence of IgG binding to CINs holds promise as a potential prognostic biomarker for PANDAS patients treated with IVIG.

In another study, Wells et al. (2024) collected serum from 47 PANS/PANDAS patients to analyze for the presence of folate receptor alpha autoantibodies (FRAAs). FRAAs either block or bind to folate receptors, rendering them less functional. Folate is a B-vitamin vital for cerebral function, and patients with folate receptor alpha dysfunction cannot transport folate across the blood-brain barrier. The presence of FRAAs can therefore significantly harm proper neurological function. Children with PANS/PANDAS were found to have an increased prevalence of FRAAs than healthy peers, with 63.8% of PANS/PANDAS subjects having blocking and/or binding FRAAs, suggesting that abnormalities in folate metabolism may contribute to PANS/PANDAS. Authors suggest that treatment plans targeting folate dysfunction such as leucovorin, a kind of folic acid, can improve symptoms in FRAA-positive PANS/PANDAS patients (Wells et al., 2024).

In another study using patient serum along with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), the concentration of interleukin-17 (IL-17), a pro-inflammatory cytokine, was analyzed in PANDAS patients. In the 30 patients with PANDAS, this study found a significant elevation in IL-17 levels in patient serum, but not in CSF (Foiadelli et al., 2025). Within PANDAS patients, IL-17 levels were higher in the CSF compared to patient sera. In a follow-up analysis, there were higher median values for IL-17 levels in the CSF of post-pubertal PANDAS children (>10 years of age) compared to younger subjects.

Beyond antibodies and cytokines, genetic polymorphisms have also been investigated as possible susceptibility markers. Celik et al. (2018) investigated polymorphisms of the mannose-binding lectin 2 (MBL2) gene in pediatric OCD patients and healthy controls. The MBL2 gene provides instructions to make mannose-binding lectin (MBL), a protein that identifies and binds to sugars on the surface of pathogens, including GABHS. This study found that polymorphisms of the MBL2 gene were more frequent in the OCD group compared to the controls. Moreover, the presence of any variant of the MBL2 gene was found at a 14.5-fold increased rate in PANDAS OCD patients compared to non-PANDAS OCD patients and healthy controls. This study suggests MBL2 as a candidate marker for susceptibility to childhood-onset OCD, especially PANDAS. Complementing this work, Luleyap et al. (2013) investigated polymorphisms in the promoter regions of the TNF-a gene, which codes for TNF-a, another pro-inflammatory cytokine. Authors reported a positive relationship between the —308 G/A polymorphism in PANDAS patients, but not the —850 C/T polymorphism, with both polymorphisms being chosen for the study due to their association with autoimmune disorders. A majority of PANDAS patients sampled (32 of the 37 for whom results were obtained) presented with polymorphic AA genotypes, leading the researchers to propose that the AA polymorphism of the —308 G/A polymorphism can be used as an indicator for PANDAS (Luleyap et al., 2013). These findings suggest that multiple genetic variants affecting immune regulation may contribute to PANDAS susceptibility.

3. Discussion

The studies included in this review identify candidate PANDAS biomarkers with prognostic, diagnostic, and therapeutic potential, spanning neuroimaging and immunological assays. In neuroimaging studies, PET imaging revealed increased PK binding indicative of microglial activation, supporting the suggested neuroinflammation hypothesis. The finding of elevated IL-17 levels in PANDAS patients (Foiadelli et al., 2025) also aligns with this hypothesis, as the pro- inflammatory cytokines play a role in causing the inflammatory reaction. Additionally, the finding of increased IgG binding to CINs and decreased CIN activity during flares (Xu et al., 2024) connects disrupted immune function with brain inflammation.

Currently, PANDAS is diagnosed through psychiatric evaluation, which does not address the biological etiology of the disorder. The earliest studies to explore biomarkers in PANDAS highlighted the presence of D8/17+ cells in PANDAS as a promising susceptibility marker. With PANDAS patients displaying higher expression (85%) compared to healthy controls (Swedo et al., 1997), results suggest that testing patient blood samples for D8/17 lymphocytes can provide doctors with an idea of how likely a child is to develop PANDAS. However, D8/17 lymphocytes are an indicator of both rheumatic fever and Sydenham chorea, suggesting that these markers may not be specific to the development of PANS/PANDAS.

Another promising diagnostic approach involves the use of neuroimaging. There is evidence of volumetric differences in the caudate, putamen, and globus pallidus in PANDAS (Giedd et al., 2000). Moreover, as shown by Cabrera and colleagues, gray matter differences can be used to distinguish PANDAS from non-PANDAS using machine learning algorithms applied to MRI datasets. However, a limitation of classification results is that they often lack external validation, which would help establish the model as generalizable enough to be reliably applied to data outside of the original study.

Another potential marker that may aid in the prognosis and diagnosis of PANDAS is the presence of the TNF-a —308 G/A polymorphism. Luleyap et al. (2013) found this polymorphism at a 14.5-fold increased frequency in PANDAS patients, giving it the potential to act as a prognostic tool to determine whether a child may develop the disorder. Similarly, the presence of MBL2 variants was suggested as a candidate marker for PANDAS OCD (Celik et al., 2018), distinct from other childhood-onset OCD variants.

Prognosis poses a significant challenge in the case of PANDAS. It is currently difficult to determine whether a child will develop PANDAS or whether they will be able to recover fully from the disorder, enter a relapsing-remitting state, or reach the chronic-static/progressive stage. The literature suggests that neuroinflammation in the basal ganglia is a key marker of PANDAS, although this is only applicable before a patient reaches the chronic state. It is hypothesized that inflammation during the early course of disease results in swelling, whereas chronic disease is linked to atrophy (Zheng et al., 2020). This is supported by Giedd et al.’s findings of an inflammatory increase in basal ganglia volume in subjects with recent-onset PANDAS. Additionally, in the PET study, increased PK binding that was found in PANDAS patients decreased with a longer duration of illness (Kumar et al., 2014). PET imaging can be used with treatment in patients to evaluate the efficacy of a particular treatment.

Finally, the studies included in this review also reveal the therapeutic potential of certain markers. Current treatments for PANDAS are costly and inaccessible (W Tang et al., 2021). The heightened presence of blocking and/or binding FRAAs in PANDAS patients suggests that taking leucovorin, a type of folic acid, may assist in improving the symptoms of PANDAS (Wells et al., 2024). This, although not necessarily the most long-term or effective solution, provides a more cost-effective therapeutic plan for patients.

Further characterization of these markers will enable researchers to better understand biological targets for new therapeutic methods – such as targeting IL-17 to lower neuroinflammatory response. Through identifying potential markers, the studies have also identified potential targets for future therapeutic approaches.

3.1. Limitations

Currently, because of the variability of PANDAS and its relatively recent discovery, there is little known about its long-term prognosis or how to determine whether or not a child is at risk of developing the disease (Gromark et al., 2021). Due to the generally small patient populations available, identified markers within individual studies may not be generalizable. As the majority of studies included in this review were conducted in the United States and Europe, potential biases were present due to nationality, ethnicity, and/or race of subjects. Additionally, findings from animal models may not be wholly accurate when applied to humans. Many of the studies did not clarify the disease stage of their participants, potentially skewing results or limiting interpretation. Furthermore, some of the identified markers were not unique to PANDAS, instead representing childhood-onset OCD as a whole or diseases such as Sydenham chorea, and therefore lack PANDAS-specific diagnostic or prognostic value (as seen in Swedo et al., 1997). Lastly, a few studies used in this review conflated PANS and PANDAS. Although PANDAS falls under the umbrella of PANS, the separation of PANDAS and PANS is an ongoing debate in the research community.

4. Conclusion

The research compiled thus far on potential biomarkers for PANDAS provides an interesting path for further studies into possible prognostic, diagnostic, and therapeutic innovations. While studies have identified multiple candidate markers, the research has not yet discussed integrating them for more effective diagnostic or prognostic use. Future research should confirm the widespread applicability and accuracy of proposed biomarkers, as well as explore the optimal use of these markers to develop new prognostic, diagnostic, and therapeutic techniques. Researching candidate markers presents an important path forward into developing accessible care for PANDAS, as current diagnostic and care methods are often unattainable.

References

- Swedo, S., Leonard, H., Garvey, M., Mittleman, B., Allen, A., Perlmutter, S., Dow, S., Zamkoff, J., Dubbert, B., & Lougee, L. (1998). Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated With Streptococcal Infections: Clinical Description of the First 50 Cases. American Journal of Psychiatry, 155(2). [CrossRef]

- Snider, L. A., & Swedo, S. E. (2004). PANDAS: Current Status and Directions for Research. Molecular Psychiatry, 9(10), 900–907. [CrossRef]

- Singer, H. S., & Loiselle, C. (2003). PANDAS: A Commentary. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 55(1), 31–39. [CrossRef]

- Arcilla, C., & Singla, R. (2024). Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated With Streptococcal Infections (PANDAS). StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK606088/.

- Frick, L., & Pittenger, C. (2016). Microglial Dysregulation in OCD, Tourette Syndrome, and PANDAS. Journal of Immunology Research, 2016(1). [CrossRef]

- La Bella, S., Scorrano, G., Rinaldi, M., Di Ludovico, A., Mainieri, F., Attanasi, M., Spalice, A., Chiarelli, F., & Breda, L. (2023). Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal Infec- tions (PANDAS): Myth or Reality? The State of the Art on a Controversial Disease. Microorganisms, 11(10). [CrossRef]

- Singer, H. S., Loiselle, C.R., Lee, O., Minzer, K., Swedo, S. E., & Grus, F. H. (2004). Anti-basal ganglia an- tibodies in PANDAS. Movement Disorders: Official Journal of the Movement Disorder Society, 19(4), 406–415. [CrossRef]

- Martino, D., Church, A. J., Dale, R. C., & Giovannoni, G. (2005). Antibasal ganglia antibodies and PANDAS. Movement Disorders: Official Journal of the Movement Disorder Society, 20(1). [CrossRef]

- W Tang, A., J Appel, H., C Bennett, S., H Forsyth, L., K Glasser, S., A Jarka, M., D Kory, P., N Malik, A., I Martonoffy, A., K Wahlin, L., T Williams, T., A Woodin, N., C Woodin, L., K T Miller, I., & G Miller, L. (2021). Treatment barriers in PANS/PANDAS: Observations from eleven health care provider families. Family Systems Health, 39(3). [CrossRef]

- Gromark, C., Hesselmark, E., Djupedal, I., Silverberg, M., Horne, A., Harris, R., Serlachius, E., & Mataix-Cols,.

- D. (2021). A Two-to-Five Year Follow-Up of a Pediatric Acute-Onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome Cohort. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 53, 354–364. [CrossRef]

- Swedo, S. E., Leckman, J., & Rose, N. (2012). From Research Subgroup to Clinical Syndrome: Modifying the PANDAS Criteria to Describe PANS (Pediatric Acute-onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome). Pediatrics and Therapeutics, 2(2).

- Prato, A., Gulisano, M., Scerbo, M., Barone, R., Vicario, C., & Rizzo, R. (2021). Diagnostic Approach to Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated With Streptococcal Infections (PANDAS): A Narrative Review of Literature Data. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 9. [CrossRef]

- Giedd, J., Rapoport, J., Garvey, M., Perlmutter, S., & Swedo, S. (2000). MRI Assessment of Children With Obsessive- Compulsive Disorder or Tics Associated With Streptococcal Infection. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 157(2). [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, B., Romero-Rebollar, C., Jiménez-Ángeles, L., Genis-Mendoza, A., Flores, J., Lanzagorta, N., Arroyo, M., de la Fuente-Sandoval, C., Santana, D., Medina-Bañuelos, V., Sacristán, E., & Nicolini, H. (2018). Neuroanatomical fea- tures and its usefulness in classification of patients with PANDAS. CNS Spectrums, 24(5). [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A., Williams, M., & Chugani, H. (2014). Evaluation of Basal Ganglia and Thalamic Inflammation in Children With Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated With Streptococcal Infection and Tourette Syndrome: A Positron Emission Tomographic (PET) Study Using 11C-[R]-PK11195. Journal of Child Neurology.

-

30(6). [CrossRef]

- Colonna, M., & Butovsky, O. (2017). Microglia Function in the Central Nervous System During Health and Neurode- generation. Annual Review of Immunology, 35, 441–468. [CrossRef]

- Swedo, S., Leonard, H., Mittleman, B., Allen, A., Rapoport, J., Dow, S., Kanter, M., Chapman, F., & Zabriskie, J. (1997). Identification of Children With Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated With Streptococ- calInfections by a Marker Associated With Rheumatic Fever. American Journal of Psychiatry, 154(1), 110–112.

- Murphy, T. K., Goodman, W. K., Fudge, M. W., Williams, R. C., Ayoub, E. M., Dalal, M., Lewis, M. H., & Zabriskie, J.

- B. (1997). B lymphocyte antigen D8/17: A peripheral marker for childhood-onset obsessive-compulsive disorder and Tourette’s syndrome? American Journal of Psychiatry, 154(3).

- Hoekstra, P. J., Bijzet, J., Limburg, P. C., Steenhuis, M. P., Troost, P. W., Oosterhoff, M. D., Korf, J., Kallenberg, C. G., & Minderaa, R. B. (2001). Elevated D8/17 expression on B lymphocytes, a marker of rheumatic fever, measured with flow cytometry in tic disorder patients. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158(4). [CrossRef]

- Frick, L., Rapanelli, M., Jindachomthong, K., Grant, P., Leckman, J., Swedo, S., Williams, K., & Pittenger, C. (2018). Differential binding of antibodies in PANDAS patients to cholinergic interneurons in the striatum. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 69. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J., Frankovich, J., Liu, R.-J., Thienemann, M., Silverman, M., Farhadian, B., Willett, T., Manko, C., Columbo, L., Leibold, C., Vaccarino, F., Che, A., & Pittenger, C. (2024). Elevated antibody binding to striatal cholinergic interneurons in patients with pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 122, 241–255. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J., Liu, R.-J., Fahey, S., Frick, L., Leckman, J., Vaccarino, F., Duman, R., Williams, K., Swedo, S., & Pittenger, C. (n.d.). Antibodies From Children With PANDAS Bind Specifically to Striatal Cholinergic Interneurons and Alter Their Activity. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 178(1). [CrossRef]

- Wells, L., O’Hara, N., Frye, R., Hullavard, N., & Smith, E. (2024). Folate Receptor Alpha Autoantibodies in the Pediatric Acute-Onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome (PANS) and Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal Infections (PANDAS) Population. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 14(166). [CrossRef]

- Foiadelli, T., Loddo, N., Sacchi, L., Santi, V., D’Imporzano, G., Spreafico, E., Orsini, A., Ferretti, A., De Amici, M., Testa, G., Luigi Marseglia, G., & Savasta, S. (2025). IL-17 in serum and cerebrospinal fluid of pediatric patients with acute neuropsychiatric disorders: Implications for PANDAS and PANS. European Journal of Pediatric Neurology, 54, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Celik, G., Arslan Tas, D., Yolga Tahiroglu, A., Erken, E., Seydaoglu, G., Cam Ray, P., & Avci, A. (2018). Mannose- Binding Lectin 2 Gene Polymorphism in PANDAS Patients. Archives of Neuropsychiatry, 56(2), 99–105.

- Luleyap, H. U., Onatoglu, D., Yilmaz, M. B., Alptekin, D., Tahiroglu, A., Cetiner, S., Pazarbasi, A., Unal, I., Avci, A., & Comertpay, G. (2013). Association between pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections disease and tumor necrosis factor-a gene 308 g/a, 850 c/t polymorphisms in 4-12-year- old children in Adana/Turkey. Indian Journal of Human Genetics, 19(2), 196–201. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J., Frankovich, J., McKenna, E., Rowe, N., MacEachern, S., Ng, N., Tam, L., Moon, P., Gao, J., Thienemann, M., Forkert, N., & Yeom, K. (2020). Association of Pediatric Acute-Onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome With Microstructural Differences in Brain Regions Detected via Diffusion-Weighted Magnetic Resonance Imaging. JAMA Netw Open, 3(5). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).