1. Introduction

Mathematics, as an intellectual discipline, possesses unique epistemological characteristics distinguished by abstraction, logic, and systematic reasoning. The nature of mathematics transcends mere numerical manipulation; it embodies a structured system of interrelated concepts that evolve through rigorous deductive processes. These abstract entities require learners to construct mental representations that connect symbols to meaning. As such, mathematics provides not only tools for quantification and measurement but also a universal language for interpreting phenomena across scientific disciplines. The abstractness of mathematics, however, presents challenges for learners, demanding cognitive maturity and high-level reasoning abilities. Thus, mathematics education must be designed to bridge the gap between abstract theory and practical comprehension through purposeful pedagogical interventions [

21,

22].

Mathematics is a field of study with distinctive characteristics that involve abstract ideas and hierarchically structured concepts. It plays a crucial role in shaping students into high-quality human resources. Mathematics education, which is integrated into an individual’s life from preschool to higher education, serves as an essential component of the overall learning process in schools. In this context, students need to develop not only computational skills but also deep conceptual understanding and the ability to think and reason mathematically to solve problems and grasp new concepts [

23,

24]. Therefore, every mathematics learning session must include fundamental elements of mathematical understanding.

In the broader educational framework, mathematics serves as a cornerstone for cognitive development, nurturing logical reasoning, critical analysis, and systematic problem-solving abilities. The mastery of mathematics enables individuals to navigate technological and scientific domains, which are indispensable in modern society. According to [

25,

26], the teaching of mathematics contributes significantly to shaping learners into analytical thinkers who can engage effectively with complex issues. This transformative function of mathematics positions it as a fundamental element in building high-quality human resources capable of responding to global challenges in science, economy, and technology. Consequently, mathematics learning must be more than an accumulation of formulas; it must cultivate intellectual habits that promote curiosity, persistence, and creativity [

27,

28].

Mathematics education also operates as a dynamic and continuous process that accompanies learners throughout their academic journey—from early childhood education to higher education. At each level, the cognitive demands of mathematical learning increase, requiring learners to assimilate prior knowledge into increasingly complex conceptual frameworks. This cumulative nature underscores the importance of solid foundational understanding at every stage of learning. When early mathematical experiences are meaningful and contextually relevant, they lay the groundwork for higher-order reasoning and advanced mathematical thinking in later years. Therefore, effective instructional strategies must emphasize conceptual continuity and scaffolding to ensure sustainable cognitive growth [

29,

30].

One of the most critical objectives of mathematics education is to foster deep conceptual understanding rather than superficial memorization. Conceptual understanding refers to the learner’s ability to comprehend mathematical principles, recognize relationships among ideas, and apply them flexibly to various problem situations. This type of understanding allows students to interpret mathematical structures intuitively, transfer knowledge to new contexts, and develop self-regulated learning strategies. However, research indicates that traditional instruction—dominated by rote learning and teacher-centered approaches—often fails to cultivate such depth of comprehension. This limitation necessitates the exploration of innovative pedagogical models that can promote genuine understanding through interaction, collaboration, and discovery [

31,

32].

Moreover, the hierarchical nature of mathematical knowledge requires learners to construct new concepts upon previously established foundations. For example, proficiency in arithmetic operations forms the basis for understanding algebraic reasoning, which in turn supports the comprehension of calculus and advanced mathematical analysis. When foundational understanding is weak, subsequent learning becomes fragmented and unstable. Thus, teachers play a crucial role in diagnosing misconceptions and providing remedial interventions that strengthen conceptual coherence. Instructional design must integrate diagnostic assessment and formative feedback as integral components of teaching to guide students toward mastery of mathematical structures systematically [

33,

34].

Equally important is the cultivation of mathematical reasoning, which encompasses logical thinking, justification, and proof construction. Mathematical reasoning enables students to formulate conjectures, test hypotheses, and derive valid conclusions through deductive or inductive methods. In modern mathematics education, reasoning is recognized as a central competency alongside problem-solving and communication. Encouraging reasoning processes requires teachers to design learning environments that challenge students to explain their thinking, critique alternative solutions, and justify their methods. By engaging in such practices, students internalize mathematics as a coherent and logical discipline rather than a collection of isolated procedures [

35,

36].

Problem-solving, as another pillar of mathematical literacy, represents the application of conceptual understanding and reasoning in meaningful contexts. It is through problem-solving that students experience the relevance and power of mathematics in addressing real-world challenges. Effective problem-solving involves identifying the problem, formulating strategies, executing plans, and evaluating results. It also promotes metacognitive awareness, allowing learners to monitor and regulate their cognitive processes. Consequently, mathematics education must integrate authentic, contextually rich problems that reflect students’ lived experiences and stimulate their intellectual engagement. When learning tasks are meaningful, motivation and perseverance tend to increase, leading to deeper learning outcomes [

37,

38].

Motivation plays an indispensable role in sustaining students’ engagement with mathematical learning. The abstract nature of mathematics can often lead to anxiety, resistance, or disengagement among students. Therefore, instructional methods should aim to enhance intrinsic motivation by emphasizing mastery goals, autonomy, and relevance. When students perceive mathematics as valuable and attainable, they are more likely to invest effort in understanding difficult concepts. Additionally, supportive classroom interactions—such as peer collaboration and teacher encouragement—can foster a positive emotional climate conducive to learning. As a result, motivation and understanding become mutually reinforcing elements that determine overall achievement [

36,

40].

In the current era of educational reform, there is growing recognition that mathematics learning should not only transmit knowledge but also develop 21st-century competencies. These competencies include creativity, critical thinking, communication, and collaboration—skills that extend beyond the mathematics classroom and are essential for lifelong learning. Integrating technology, contextual learning, and inquiry-based approaches can help achieve these goals. Mathematics education must therefore evolve toward more student-centered paradigms that value exploration and reflection. The alignment of curriculum, instruction, and assessment toward these holistic objectives ensures that mathematics remains a living, dynamic field that empowers learners to think independently and innovatively [

41].

Ultimately, the inclusion of mathematical understanding as a fundamental element in every learning session is indispensable for building a strong intellectual foundation among students. Teaching that promotes deep understanding enables learners to connect abstract symbols with real-world meaning, fostering a sense of coherence and purpose in their learning journey. The responsibility lies with educators to design experiences that balance procedural fluency with conceptual insight, guided by sound pedagogical principles and reflective practice. Through sustained commitment to quality mathematics instruction, education can fulfill its mission of developing individuals who are not only proficient in computation but also capable of reasoning critically, solving problems creatively, and contributing meaningfully to the advancement of science and society [

1,

2].

In Indonesia, mathematics education faces various challenges, one of which is the low level of students’ mathematical understanding. Many students, particularly at the junior high school level, struggle to comprehend basic mathematical concepts. According to research conducted by [

3], initial testing revealed that students’ mathematical understanding abilities were generally low. This was evident from their limited grasp of operational concepts and frequent errors when applying them. Such conditions are concerning, as the mastery of basic understanding serves as a foundation for more complex mathematical learning at higher levels [

3].

Mathematics education continues to face persistent and multifaceted challenges that have significant implications for students’ academic achievement and cognitive development. Among these, the low level of mathematical understanding remains one of the most pressing issues confronting educators and policymakers alike. Despite curriculum reforms and pedagogical innovations introduced over the past two decades, many students still exhibit limited comprehension of fundamental mathematical principles. This phenomenon reflects deeper structural and pedagogical problems within the educational system, including the quality of instruction, classroom engagement, and assessment practices. Consequently, improving mathematical understanding has become an urgent educational priority to strengthen the nation’s human resource development in the era of global competitiveness [

4,

5].

At the junior high school level, the challenge becomes particularly pronounced, as this stage serves as a critical transition point where students are expected to shift from concrete operational thinking to more abstract mathematical reasoning. However, many students in Indonesia experience significant difficulty in making this cognitive leap. According to [

5], diagnostic evaluations conducted across several schools revealed that the majority of learners demonstrated weak conceptual understanding, particularly in topics requiring symbolic representation and logical reasoning. This deficiency suggests that mathematics learning in earlier grades may have overly emphasized procedural fluency at the expense of conceptual mastery, resulting in students who can perform operations mechanically without understanding their underlying meaning [

6,

7].

Empirical findings from various studies corroborate these observations, indicating that Indonesian students often struggle to connect mathematical symbols with real-world contexts. The inability to internalize the meaning of abstract concepts leads to fragmented knowledge and inconsistent performance across topics [

8]. identified that even basic operational concepts, such as fractions, ratios, and equations, were frequently misunderstood by learners, leading to systematic errors in computation and problem-solving. These difficulties are not merely cognitive but also pedagogical in nature, reflecting instructional practices that prioritize memorization over reasoning and accuracy over understanding. This condition underscores the need to reorient mathematics instruction toward deeper conceptual engagement [

9].

Furthermore, these deficiencies are reflected in national assessment results and international benchmarking studies such as PISA and TIMSS, where Indonesian students consistently rank below the global average in mathematical literacy. The low performance in these assessments signifies not only limited mastery of content but also the inability to apply mathematical reasoning to unfamiliar or real-life situations. Such outcomes point to systemic shortcomings in teaching approaches, curriculum implementation, and learning environments. When mathematical understanding is weak, students struggle to progress to higher-level concepts such as algebraic manipulation, geometric reasoning, and statistical interpretation—skills that are essential for academic and professional advancement in science, technology, and engineering [

10,

11].

The roots of this issue can be traced to traditional teaching methods that remain dominant in many Indonesian classrooms. Teacher-centered instruction, characterized by lecture-based delivery and minimal student interaction, tends to position learners as passive recipients of information. While such methods may efficiently transmit procedural knowledge, they do little to cultivate critical thinking, exploration, or conceptual understanding. Students are often trained to memorize formulas and follow algorithms without questioning the rationale behind them. As a result, learning becomes an act of repetition rather than discovery. This mode of instruction limits students’ capacity to transfer knowledge to novel contexts, thereby stunting the development of higher-order mathematical reasoning [

12,

13].

Another contributing factor is the limited use of formative assessment and feedback mechanisms in mathematics instruction. Many teachers focus on summative evaluation, emphasizing correct answers over the reasoning process that leads to them. This approach fails to identify and address students’ misconceptions in real time, allowing misunderstandings to persist and compound over time. Studies such as that by [

14] demonstrate that students’ frequent computational errors often stem from conceptual confusion, which could have been corrected through timely feedback and reflective discussion. Therefore, assessment should be reconceptualized as a tool for learning rather than merely a means of grading performance [

15,

16].

Socioeconomic and contextual factors also play a role in shaping students’ mathematical understanding. Variations in resource availability, teacher quality, and classroom size across urban and rural regions contribute to disparities in learning outcomes. In many schools, the lack of instructional materials, technological tools, and teacher training programs constrains the implementation of effective pedagogies. Teachers often face pressure to complete the curriculum within limited time frames, leaving little room for exploration or remediation. Consequently, learning becomes superficial and examination-oriented. Such systemic constraints highlight the need for educational reforms that emphasize quality over quantity and understanding over coverage [

17,

18].

Students’ attitudes toward mathematics significantly influence their learning outcomes. Mathematics is frequently perceived as a difficult and intimidating subject, leading to anxiety, avoidance, and low motivation. When students approach mathematics with fear rather than curiosity, their engagement diminishes, and their conceptual growth stagnates. Research suggests that these affective factors are particularly pronounced in early adolescence, the age group represented by junior high school students. Therefore, addressing the issue of low mathematical understanding requires not only cognitive but also affective interventions that build students’ confidence, resilience, and intrinsic motivation to learn mathematics [

19,

20].

To overcome these challenges, mathematics education in Indonesia must adopt more student-centered and inquiry-based pedagogical approaches. Approaches such as problem-based learning, peer tutoring, and collaborative learning have shown promise in enhancing conceptual understanding and engagement. These strategies encourage students to construct their own knowledge through active participation, discussion, and reflection. By situating learning in meaningful contexts, students are better able to see the relevance of mathematics to everyday life and thus develop deeper, more connected understandings. The integration of such methods into classroom practice can transform mathematics from a subject of rote learning into a discipline of reasoning and discovery [

21,

22].

Ultimately, improving students’ mathematical understanding in Indonesia requires a comprehensive and systemic effort that involves curriculum redesign, teacher professional development, and supportive learning environments. As [

23] emphasized, the mastery of fundamental mathematical concepts forms the essential foundation upon which more advanced learning is built. Without this foundation, students are unlikely to succeed in higher levels of education or in fields that rely heavily on quantitative reasoning. Therefore, strategic interventions must focus on strengthening conceptual understanding at the junior high school level, ensuring that every learner possesses the cognitive and motivational readiness to engage with mathematics meaningfully and successfully [

24].

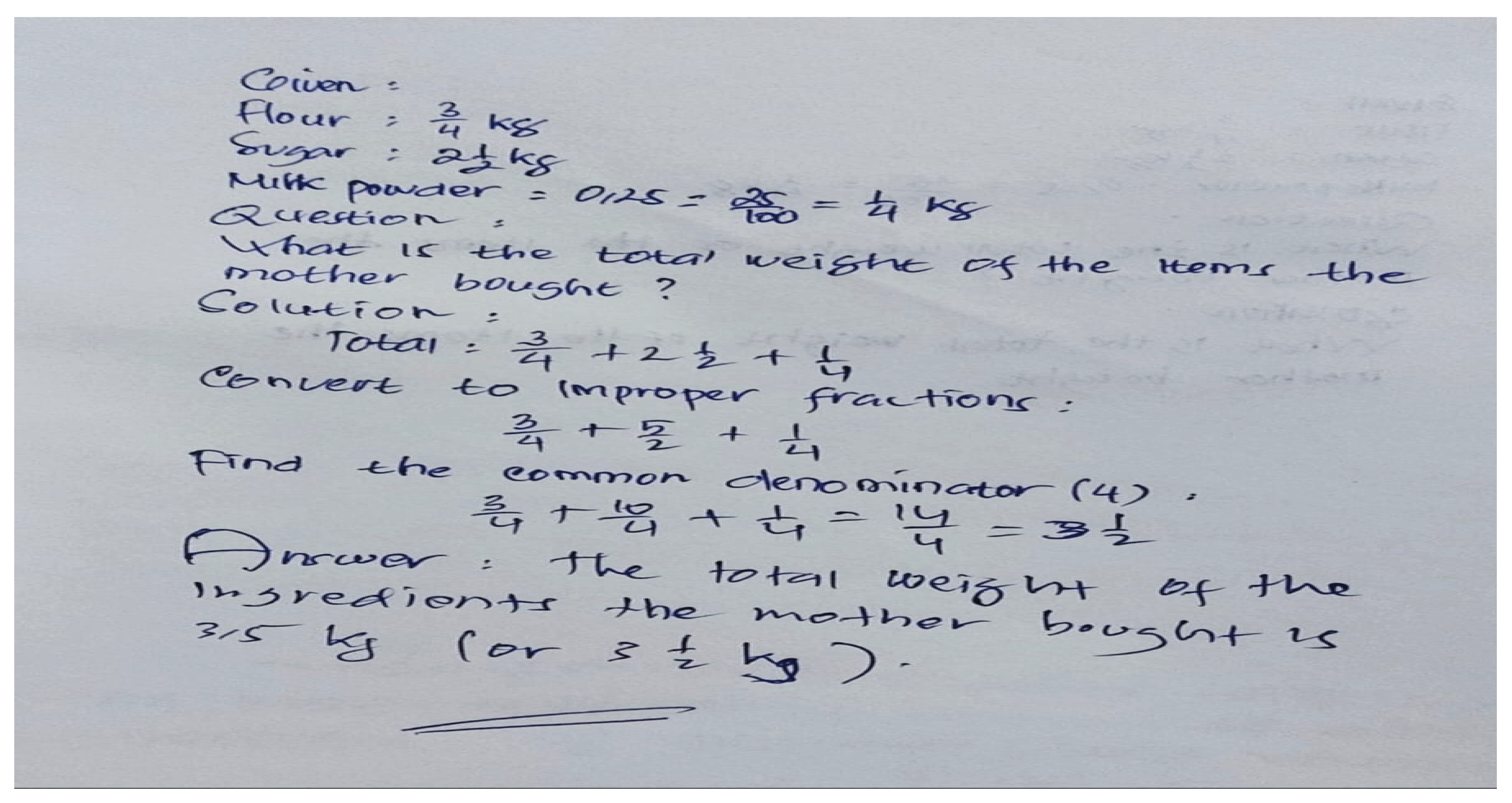

Based on the evaluation of students’ mathematical understanding skills at SMP Negeri 1 Sinunukan, it was found that 74% of seventh-grade students still had difficulties in solving mathematical comprehension problems related to arithmetic operations on rational numbers. This difficulty was evident in students’ responses to basic mathematical tasks, such as the following example problem:

Example: Preliminary Study Problem on Mathematical Understanding

A mother wants to buy ingredients for baking. She buys ¼ kg of flour, 2½ kg of sugar, and 0.25 kg of milk powder. What is the total weight of the items she bought?

Figure 1.

Student’s Answer.

Figure 1.

Student’s Answer.

This example illustrates that students often encounter obstacles when interpreting and applying rational number operations in real-life contexts. Such findings emphasize the urgent need for effective instructional methods—such as the Peer Tutoring Method—to improve students’ conceptual understanding and problem-solving abilities in mathematics.

In the figure presented, it can be observed that the student has successfully noted the essential information from the problem but still encountered difficulties in solving it. This challenge arises due to an inadequate mathematical understanding, particularly in operating with fractional numbers. Although the student can identify the key components of the problem, they are unable to apply the correct concepts to calculate the total weight of the purchased items. The identified indicators of mathematical understanding include difficulties in comprehending the addition and subtraction of rational numbers and the inability to formulate structured problem-solving steps. From this analysis, it can be concluded that the student’s level of mathematical understanding remains relatively low.

Based on classroom observations of mathematics learning at SMP Negeri 1 Sinunukan, this phenomenon is quite common. During mathematics lessons, it is often found that several students struggle when asked about basic arithmetic operations. This situation indicates a significant gap in understanding among students—those with lower comprehension levels are unable to keep up with peers who understand the material better. As a result, they tend to become passive and feel pressured in the learning environment. The teacher’s attitude also plays a crucial role in this context. Observations show that teachers often continue the lesson while focusing on achieving curriculum targets, sometimes overlooking students who require special attention. Moreover, students who experience difficulties in understanding the material often feel reluctant or embarrassed to ask questions, which leads to prolonged confusion and weak foundational mathematical knowledge.

Therefore, a more inclusive approach is needed to support students with low mathematical comprehension. One effective solution is the

peer tutoring method, in which students are divided into small groups consisting of mixed abilities—those above and below average. According to [

25], the peer tutoring model encourages active student participation by utilizing more capable peers as tutors for their classmates. This method also enhances students’ confidence in expressing their ideas [

26]. adds that one of the key advantages of peer tutoring is the development of closer and more personal relationships among students. It fosters a sense of responsibility and self-confidence, while the tutoring activities function as enrichment that increases learning motivation.

In response to the persistent issue of students’ low mathematical comprehension, a more inclusive and participatory learning approach has become essential within contemporary mathematics education. The conventional model of instruction, which relies heavily on teacher-centered explanation and individual performance, often fails to accommodate the diversity of student abilities found in typical classrooms. Consequently, differentiated pedagogical strategies that emphasize collaboration and peer interaction have gained increasing attention. Among these strategies, peer tutoring stands out as a practical and evidence-based method that promotes equity, engagement, and cognitive growth through social learning processes [

27].

Peer tutoring, in its simplest form, involves students helping one another to learn academic content under structured guidance from the teacher. This model operates on the premise that learning is not only an individual cognitive act but also a social process, in which knowledge is co-constructed through dialogue, interaction, and shared experience. According to [

28], peer tutoring facilitates active participation by assigning more proficient learners as tutors to assist their peers who may be struggling with specific topics. Such collaboration transforms the classroom into a community of learners, where every student has both the opportunity to teach and to learn. This reciprocal relationship strengthens understanding for both parties—the tutor consolidates their mastery by explaining concepts, while the tutee benefits from accessible, peer-level explanations [

29].

Empirical evidence supports the efficacy of peer tutoring in enhancing conceptual understanding and problem-solving abilities, particularly in mathematics. Unlike traditional instruction, peer tutoring provides an interactive learning environment where students can express confusion, ask questions freely, and receive immediate feedback in a non-threatening setting. This dynamic fosters a deeper cognitive engagement with the material, as students actively process information rather than passively absorb it. Research conducted by [

30] revealed that students participating in peer tutoring sessions demonstrated significant improvement in their mathematical reasoning skills and confidence levels compared to those in conventional classes [

31].

A key strength of peer tutoring lies in its ability to accommodate learners of varying abilities within the same classroom context. By grouping students into mixed-ability pairs or small groups, the learning process becomes more inclusive and differentiated. The tutors, often students with higher academic achievement, not only reinforce their own understanding through teaching but also develop empathy, leadership, and communication skills. Meanwhile, the tutees gain access to peer support that bridges the cognitive gap between teacher instruction and personal comprehension. This form of scaffolding aligns closely with [

1,

2] concept of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), wherein learning occurs most effectively through social interaction with more knowledgeable peers [

32].

Beyond cognitive gains, peer tutoring has profound socio-emotional benefits [

3,

4]. notes that one of the most salient outcomes of this model is the development of closer and more personal relationships among students. The collaborative nature of tutoring fosters trust, mutual respect, and a sense of belonging within the classroom community. These interpersonal dynamics are critical for creating a positive learning environment in which students feel valued and supported. When learners perceive that their struggles are shared and that assistance is available from their peers, they are more likely to engage actively in the learning process and less likely to experience feelings of isolation or academic anxiety [

5,

6].

Peer tutoring also contributes to the enhancement of student confidence and self-efficacy, both for tutors and tutees. For tutors, the act of explaining mathematical concepts to others reinforces their mastery and validates their competence. For tutees, receiving guidance from a peer who is perceived as approachable and relatable reduces affective barriers to learning. According to [

7,

8], this interaction helps build students’ confidence in articulating their ideas, asking questions, and taking intellectual risks—skills that are essential for deeper mathematical thinking. As confidence grows, students become more autonomous learners, capable of pursuing understanding through collaboration and inquiry rather than reliance on direct instruction [

2].

The motivational dimension of peer tutoring has also been widely documented. As [

10] emphasized, the tutoring process functions not only as a form of academic support but also as an enrichment activity that stimulates students’ intrinsic motivation. When students see tangible improvements in their understanding as a result of peer interaction, they experience a sense of achievement and ownership over their learning. This sense of accomplishment, in turn, nurtures a positive attitude toward mathematics—a subject often regarded with apprehension. Moreover, the social accountability inherent in tutoring relationships encourages students to prepare, participate, and persist more diligently in their learning tasks [

12].

However, the success of peer tutoring depends heavily on effective planning, guidance, and monitoring by teachers. The teacher’s role is crucial in establishing clear objectives, defining roles, and ensuring that the interactions remain productive and focused on learning goals. Without proper structure, peer tutoring risks devolving into casual conversation or misinformation exchange. Therefore, teachers must design activities that promote constructive dialogue, critical questioning, and reflection. Providing training for student tutors, offering formative feedback, and integrating peer tutoring with formal assessment can maximize its educational value while maintaining academic rigor and alignment with curricular standards [

41].

From a pedagogical standpoint, peer tutoring aligns with constructivist learning theories that emphasize active engagement and social collaboration. The method shifts the epistemological foundation of learning from teacher-transmitted knowledge to student-constructed understanding. In mathematics education, this shift is particularly valuable, as it encourages learners to make sense of abstract concepts through verbal explanation, argumentation, and contextual application. Through peer discussion and cooperative problem-solving, students learn to communicate mathematically—an essential competency identified in contemporary educational frameworks such as the 21st-century skills and the OECD learning compass (OECD, 2020) [

42].

In summary, peer tutoring represents a powerful and inclusive pedagogical innovation capable of addressing the diverse learning needs found in mathematics classrooms. It bridges cognitive, social, and emotional dimensions of learning by empowering students to take active roles as both teachers and learners. As [

43] have observed, its implementation not only enhances mathematical comprehension but also cultivates confidence, motivation, and social cohesion—qualities indispensable for lifelong learning. Given these multifaceted benefits, the integration of peer tutoring into mathematics instruction can be viewed as a strategic approach to promoting equity, improving academic outcomes, and nurturing a collaborative culture of learning within Indonesian schools and beyond [

44].

Furthermore, the success of the peer tutoring method strongly depends on students’

learning motivation. Research by [

45] shows that peer tutoring can improve motivation and encourage students to be more active in the learning process. Through this approach, students do not merely sit, listen, and take notes from the teacher’s explanation but instead engage actively with their tutors and peers [

46]. defines learning motivation as a set of efforts to create specific conditions and stimuli that encourage individuals to engage in particular learning activities. Learning motivation is crucial to establish a supportive atmosphere for achieving learning objectives. Students with high motivation tend to be more active and open to receiving help from their peers. With strong motivation, they are more confident in asking questions and participating in group discussions—behaviors that are essential for enhancing their mathematical understanding [

41].

The effectiveness of the peer tutoring method in mathematics education is inextricably linked to students’ level of learning motivation. Motivation functions as a vital internal force that drives learners to engage in and persist through the cognitive challenges associated with mathematical problem-solving. Without sufficient motivation, even the most well-designed instructional methods often fail to produce meaningful learning outcomes. According to [48], the implementation of peer tutoring significantly enhances students’ motivation to learn, which subsequently influences their engagement, persistence, and achievement. The motivational element serves not merely as an accessory to instruction but as an essential psychological condition that determines the success of pedagogical strategies [

42].

Motivation in learning can be conceptualized as the combination of internal drives, needs, and external stimuli that guide learners’ behavior toward achieving specific goals [

43]. defines learning motivation as a structured effort to create conditions that stimulate individuals to engage actively in educational activities. In the context of peer tutoring, such stimulation often arises from the social dynamics of cooperation, accountability, and recognition. When students are placed in collaborative roles—either as tutors or tutees—they experience a heightened sense of responsibility and belonging, which strengthens their intrinsic motivation to learn. This aligns with [

44] self-determination theory, which posits that motivation is optimized when learners experience autonomy, competence, and relatedness—all of which are inherent to peer tutoring activities [

45].

The peer tutoring environment provides a natural platform for fulfilling these psychological needs. As students engage in reciprocal teaching and learning, they gain autonomy by taking ownership of their educational processes. Tutors, for instance, plan how to explain concepts, select examples, and monitor their peers’ progress, while tutees exercise autonomy through questioning and self-assessment. Simultaneously, the sense of competence emerges as both parties witness their growing mastery of mathematical concepts. Relatedness, the third motivational driver, is fostered through meaningful interaction and mutual support among peers. The presence of these three conditions cultivates sustained intrinsic motivation, which in turn promotes deeper engagement and long-term retention of mathematical knowledge [

1].

Motivated learners exhibit greater persistence and are more inclined to participate in problem-solving and exploratory activities that demand higher-order thinking. In mathematics, this translates into a willingness to tackle complex and abstract problems, even in the face of initial difficulty or failure. Peer tutoring enhances this persistence by providing a safe, supportive environment where learners can receive immediate assistance from peers. As [

2] observed, students involved in peer tutoring sessions are more inclined to ask questions, clarify doubts, and persist in solving problems compared to those in teacher-dominated classrooms. The social reinforcement from peers serves as both encouragement and validation, sustaining motivation throughout the learning process [

3].

Motivated learners typically demonstrate higher persistence and greater willingness to engage in challenging cognitive tasks, particularly those involving problem-solving and critical inquiry. In the context of mathematics education, such motivation translates into students’ readiness to confront complex and abstract problems, even when initial attempts result in errors or conceptual confusion [

4]. This perseverance is an essential element of higher-order thinking, as it enables learners to explore alternative strategies, reflect on misconceptions, and gradually develop a more profound conceptual understanding. Within this framework, motivation functions as both a driving force and a sustaining mechanism for intellectual engagement, promoting resilience and self-regulation in the learning process [

6].

Peer tutoring plays a vital role in reinforcing this persistence by cultivating a safe, interactive learning environment where students feel comfortable seeking help and expressing uncertainty. Unlike traditional teacher-centered instruction, peer-assisted settings foster reciprocal communication that empowers learners to articulate ideas and receive immediate feedback. As noted by [

23], students who participate in peer tutoring sessions exhibit greater inquiry behaviors—they ask more questions, seek clarification, and demonstrate sustained engagement with problem-solving tasks. The presence of supportive peers acts as a form of social reinforcement, offering encouragement and validation that strengthen intrinsic motivation. Consequently, the interplay between motivation and peer interaction not only enhances mathematical comprehension but also builds confidence, perseverance, and a sense of academic belonging among students [

11].

Moreover, motivation plays a pivotal role in shaping students’ attitudes toward mathematics itself. Many students harbor anxiety or negative perceptions about mathematics due to repeated failure experiences or the perceived difficulty of the subject. Peer tutoring has the potential to transform these perceptions by fostering a more relaxed and collaborative atmosphere. Students who learn from peers often perceive mathematics as more accessible and relevant because explanations are conveyed in a relatable manner. This shift in perception reduces mathematics anxiety and builds a more positive attitude toward learning, which in turn enhances overall motivation and academic self-concept [

1,

2].

In addition to cognitive engagement, motivational enhancement through peer tutoring also affects emotional and behavioral aspects of learning. Motivated students display greater enthusiasm and curiosity, which are critical for sustaining attention and active participation during lessons. They are more likely to contribute ideas, discuss alternative solutions, and provide constructive feedback during group interactions. This behavioral activation further reinforces their understanding and retention of mathematical concepts. Conversely, students with low motivation tend to exhibit avoidance behaviors—such as passivity, disengagement, or fear of failure—that hinder their progress. Therefore, increasing motivation through peer interaction is not only beneficial but necessary for equitable learning outcomes [

3,

4].

It is also worth noting that motivation operates bidirectionally with achievement in the peer tutoring context. While motivated students tend to perform better academically, improved performance also enhances motivation, creating a positive feedback loop. As students achieve success through collaborative learning, they experience a sense of efficacy and pride that reinforces their drive to continue learning. This cyclical relationship underscores the importance of designing learning environments that integrate both cognitive and motivational components. Peer tutoring, by its nature, embodies this integration by combining task-oriented collaboration with emotionally supportive peer relationships [

5].

From a pedagogical standpoint, fostering motivation through peer tutoring requires intentional teacher facilitation. Teachers must ensure that group compositions are balanced, learning goals are clearly defined, and feedback mechanisms are continuous. When students understand the purpose of their roles and receive recognition for their contributions, their motivation is amplified. Additionally, teachers should model enthusiasm and encouragement, creating a classroom culture where effort and collaboration are valued over competition. Such an environment aligns with motivational theories emphasizing mastery goals rather than performance goals, thereby promoting sustained engagement and resilience among students [

6].

Cultural factors also play a role in shaping students’ motivational responses to peer tutoring. In collectivist societies such as Indonesia, cooperative learning aligns well with social norms that value harmony, mutual assistance, and community interdependence. These cultural predispositions can amplify the motivational impact of peer-based learning, as students find intrinsic satisfaction in helping others and contributing to group success. Thus, the peer tutoring model not only supports academic objectives but also resonates with the cultural context, enhancing both cognitive and affective learning outcomes [

7].

Cultural factors exert a profound influence on how students perceive and respond to various pedagogical approaches, including peer tutoring. In educational settings, learning is never a culturally neutral activity—it is shaped by the shared values, beliefs, and behavioral norms of the community in which it occurs. In collectivist societies such as Indonesia, learning is often viewed as a communal endeavor rather than an individual pursuit. This orientation toward collective well-being significantly affects students’ motivation, attitudes, and interactions within the classroom. As such, understanding the cultural backdrop becomes essential for the effective implementation of collaborative models such as peer tutoring, which rely on interpersonal cooperation and mutual respect [

8].

In Indonesian classrooms, the concept of

gotong royong—a traditional expression of mutual assistance—deeply reflects the collectivist ethos of the society. This cultural norm encourages individuals to contribute to group success and to view achievement as a shared accomplishment rather than an individual triumph. When applied to education, such values naturally align with cooperative learning environments, where peer support and shared responsibility are central. Within the peer tutoring framework, students who act as tutors do not merely transmit knowledge; they embody cultural ideals of empathy, service, and communal contribution. These factors strengthen intrinsic motivation by linking learning to culturally meaningful behaviors [

10].

Research on cultural psychology supports the notion that students from collectivist backgrounds often derive greater satisfaction and persistence from social forms of learning [

19]. explains that collectivist learners prioritize group harmony and cooperation, which makes them more receptive to instructional methods that emphasize collaboration over competition. In the Indonesian context, peer tutoring capitalizes on these predispositions by fostering environments in which students work interdependently, share responsibilities, and celebrate collective achievements. This alignment between pedagogy and culture creates a synergistic effect that enhances both academic performance and affective engagement [

21].

Moreover, cultural congruence contributes to the emotional safety of the learning environment. In traditional teacher-centered classrooms, students may hesitate to express uncertainty or ask questions due to fear of losing face or appearing disrespectful. Peer tutoring mitigates these concerns by creating a more egalitarian dynamic where students interact as partners rather than subordinates. This sense of psychological safety encourages risk-taking, which is essential for cognitive growth and conceptual exploration. Consequently, the peer tutoring model not only supports cognitive development but also cultivates a positive emotional climate that reinforces motivation and confidence [

22].

The motivational benefits of culturally embedded peer tutoring also extend to students’ sense of belonging and identity formation. Learners who participate in such cooperative settings often experience increased social connectedness, which in turn enhances their intrinsic motivation. Deci and Ryan’s Self-Determination [

41] highlights the importance of relatedness—the feeling of connection to others—as a fundamental psychological need that drives engagement and persistence. Peer tutoring naturally fulfills this need by fostering reciprocal relationships that validate each student’s role within the learning community. This process supports not only academic outcomes but also socio-emotional growth.

From a socio-constructivist perspective [

42], concept of the

Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) further explains why peer tutoring is particularly effective in collectivist contexts. The ZPD emphasizes that learning occurs most effectively through social interaction with more capable peers who provide scaffolding and guidance. In Indonesia’s cooperative culture, where interdependence is valued, this process aligns seamlessly with cultural expectations of mutual assistance and shared learning responsibility. Thus, cultural values do not merely support peer tutoring—they amplify its pedagogical power [

43].

Furthermore, the affective dimensions of peer interaction contribute to the sustainability of learning motivation. Students who tutor others often experience a sense of pride and self-efficacy, reinforcing their belief in their own competence. At the same time, those who receive tutoring feel cared for and supported by their peers, which reduces anxiety and promotes a positive attitude toward learning. This reciprocal dynamic strengthens classroom cohesion, transforming the learning environment into a microcosm of social cooperation that mirrors broader cultural patterns of community life in Indonesia [

44].

The integration of peer tutoring within a culturally responsive framework also addresses issues of equity and inclusivity in education. By recognizing and valuing collective learning orientations, teachers can design instructional strategies that empower all students to contribute meaningfully, regardless of their initial ability levels. Such practices help dismantle hierarchical classroom structures that often privilege high achievers while marginalizing those who struggle. Instead, every student becomes both a learner and a resource, reinforcing the idea that knowledge is co-constructed through shared effort [

45].

However, successful implementation of peer tutoring in collectivist settings requires careful facilitation. Teachers must ensure that the collaborative process remains academically rigorous and does not devolve into social interaction devoid of learning focus. Structured guidance, clear role assignments, and systematic reflection activities are necessary to maintain balance between cooperation and cognitive challenge. When properly managed, this approach leverages cultural strengths while avoiding potential pitfalls such as conformity pressure or overreliance on peer explanations without sufficient teacher oversight [47].

In summary, the cultural context of Indonesia offers fertile ground for the successful application of peer tutoring as a motivational and pedagogical tool. The collectivist values of cooperation, mutual assistance, and community interdependence align naturally with the principles of peer-based learning. This harmony between cultural disposition and instructional design enhances both cognitive outcomes—such as improved mathematical understanding—and affective outcomes, including motivation, confidence, and sense of belonging. Therefore, integrating cultural awareness into the design of peer tutoring programs represents not merely an adaptation but an optimization of the educational process, ensuring that teaching strategies resonate deeply with students’ lived cultural realities [

2].

Motivation serves as the psychological foundation that determines the effectiveness of peer tutoring in mathematics education. As demonstrated by [

34] and [

12], the interaction between motivation and learning engagement is dynamic and reciprocal, influencing students’ persistence, confidence, and conceptual understanding. By creating conditions that foster autonomy, competence, and relatedness, the peer tutoring approach transforms the learning experience from passive reception into active collaboration. Motivated learners are more inclined to explore, inquire, and construct meaning—behaviors essential for mastering mathematical concepts. Therefore, cultivating motivation through structured peer interaction should be a central consideration in designing inclusive and impactful mathematics instruction.

Thus, this study aims to explore the implementation of the peer tutoring method as a strategy to improve students’ mathematical understanding based on their learning motivation. It is expected that this research will provide valuable insights for developing more effective teaching strategies in the future.

3. Results and Discussion

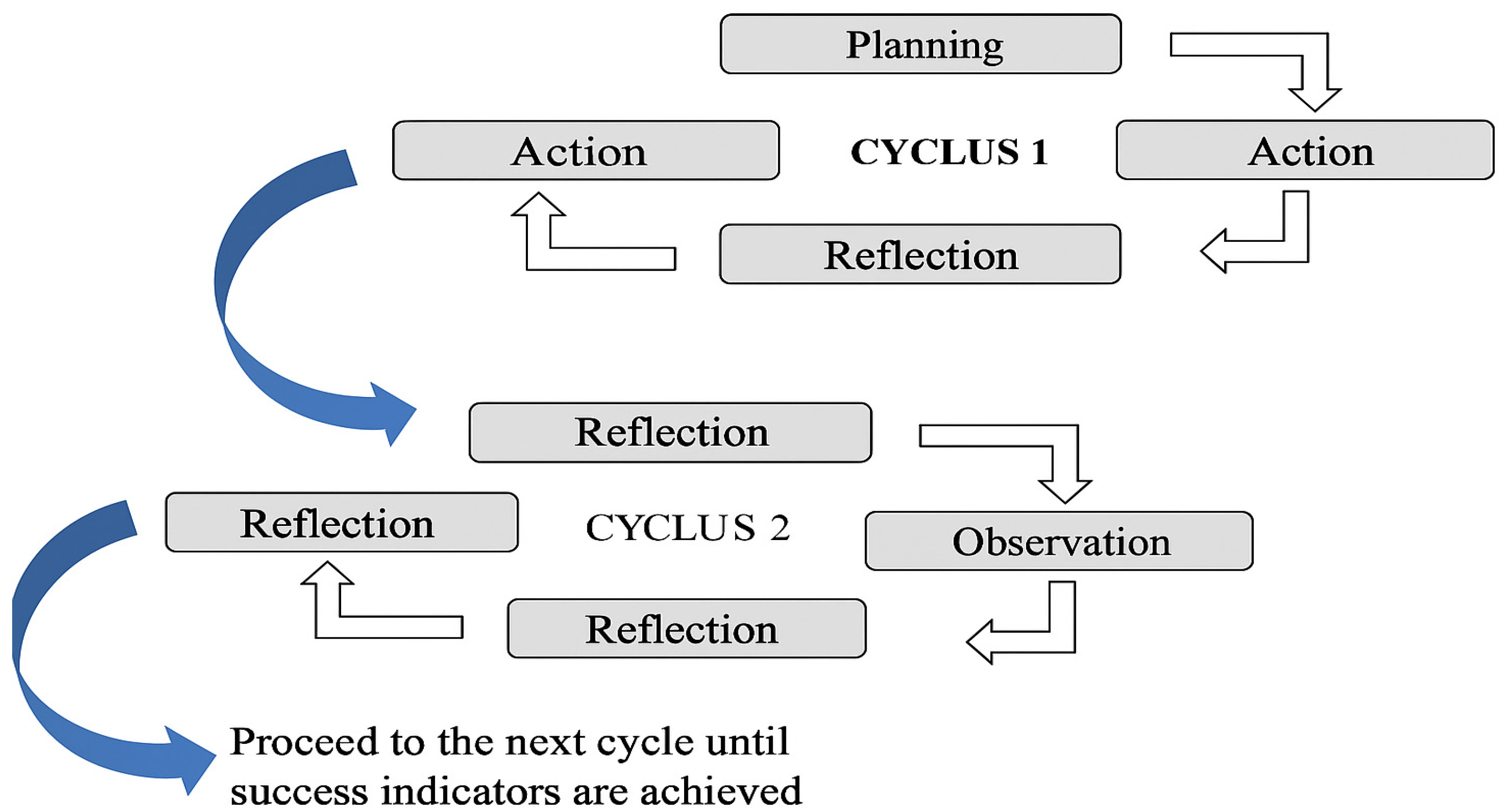

The implementation of the peer tutoring method was conducted in Class VII-A of SMP Negeri 1 Sinunukan with the primary objective of evaluating the improvement in students’ mathematical understanding. This method was chosen because it is believed to enhance peer interaction and deepen students’ conceptual grasp of mathematical topics. Prior to the implementation, the researcher conducted a comprehensive discussion with the supervising teacher to determine the most effective strategy for applying the peer tutoring method and to design the necessary research instruments.

The instruments included a mathematical understanding test, a learning motivation questionnaire, and a teacher activity observation sheet. The use of these instruments ensured the collection of accurate data regarding the effectiveness of the implemented method. These preliminary discussions also aimed to ensure the readiness of all parties involved in the research process.

Cycle I

The first cycle was conducted in two meetings, totaling four instructional periods (4 × 40 minutes). The implementation of the peer tutoring method was evaluated through observation sheets completed by the teacher throughout the lessons. A total of 27 students participated in this cycle.

At the end of Cycle I, a mathematical understanding test was administered to measure the effectiveness of the peer tutoring method. The test results revealed that 15 students had not yet achieved the mastery criterion, indicating the need for further improvement in the next cycle. The percentage of students who successfully demonstrated adequate understanding was 55.5%, while 44.4% (15 students) did not meet the standard.

These findings suggest that the percentage of students who achieved mastery was still below the predetermined success criterion of 75%. This evaluation provided a clearer insight into students’ performance levels and indicated that additional reinforcement and refinements were necessary in Cycle II to improve outcomes.

Table 1.

Results of Mathematical Understanding Test Analysis – Cycle 1.

Table 1.

Results of Mathematical Understanding Test Analysis – Cycle 1.

| SCORE PERCENTAGE RANGE |

CATEGORY |

NUMBER OF STUDENTS |

| 1% < x < 25% |

Poor |

0 |

| 25% < x < 50% |

Fair |

8 |

| 50% < x < 75% |

Good |

7 |

| 75% < x < 100% |

Very Good |

12 |

Findings from Cycle I

As shown in

Table 2, the results of the mathematical understanding test administered to Grade VII-A students in Cycle I indicate that no student fell into the

poor performance category. Specifically, 8 students (29.6%) were classified as

fair, 7 students (25.9%) as

good, and 12 students (44.4%) as

very good.

Concurrently, data from the learning motivation questionnaire revealed that 30.5% of students exhibited low motivation, while 69.5% demonstrated moderate to high motivation levels. These findings are based on responses from all 27 students, with the detailed distribution presented in

Table 2.

This distribution underscores a significant challenge in fostering student engagement. The low motivation levels were further corroborated through classroom observations and analysis of the motivation questionnaire.

The study was collaboratively conducted by the researcher and the cooperating teacher throughout the entire instructional process. Initially, students displayed enthusiasm—particularly when the peer tutoring method was introduced. However, the implementation deviated from the planned sequence due to difficulties in group formation, which resulted in classroom disruption. Given that peer tutoring relies heavily on structured group discussion, this disorganization negatively impacted the learning environment. Highly motivated students, in particular, appeared distracted by the noisy atmosphere.

Despite these challenges, most students attempted to complete assigned tasks through group collaboration. Nevertheless, several groups required repeated clarification from the teacher regarding problem-solving procedures. While the majority of students demonstrated cooperative behavior and incremental progress during discussions, a subset exhibited signs of disengagement—such as drowsiness and reluctance to participate. This was likely attributable to the timing of the lesson, which occurred close to the end of the school day, leading to fatigue and diminished attentiveness.

Observational assessment of teacher performance yielded a score of 31 out of 40 (77.5%), categorized as adequate. Strengths observed during instruction included:

(1) adherence to the lesson plan,

(2) consistent efforts to encourage student participation, and

(3) effective use of engaging instructional media.

However, several limitations were noted:

(1) absence of forward-looking guidance for subsequent lessons,

(2) insufficiently assertive classroom management during disruptive episodes,

(3) limited inclusion of all students in active learning roles, and

(4) poorly timed group discussions that extended beyond allocated periods, enabling some students to procrastinate on task completion.

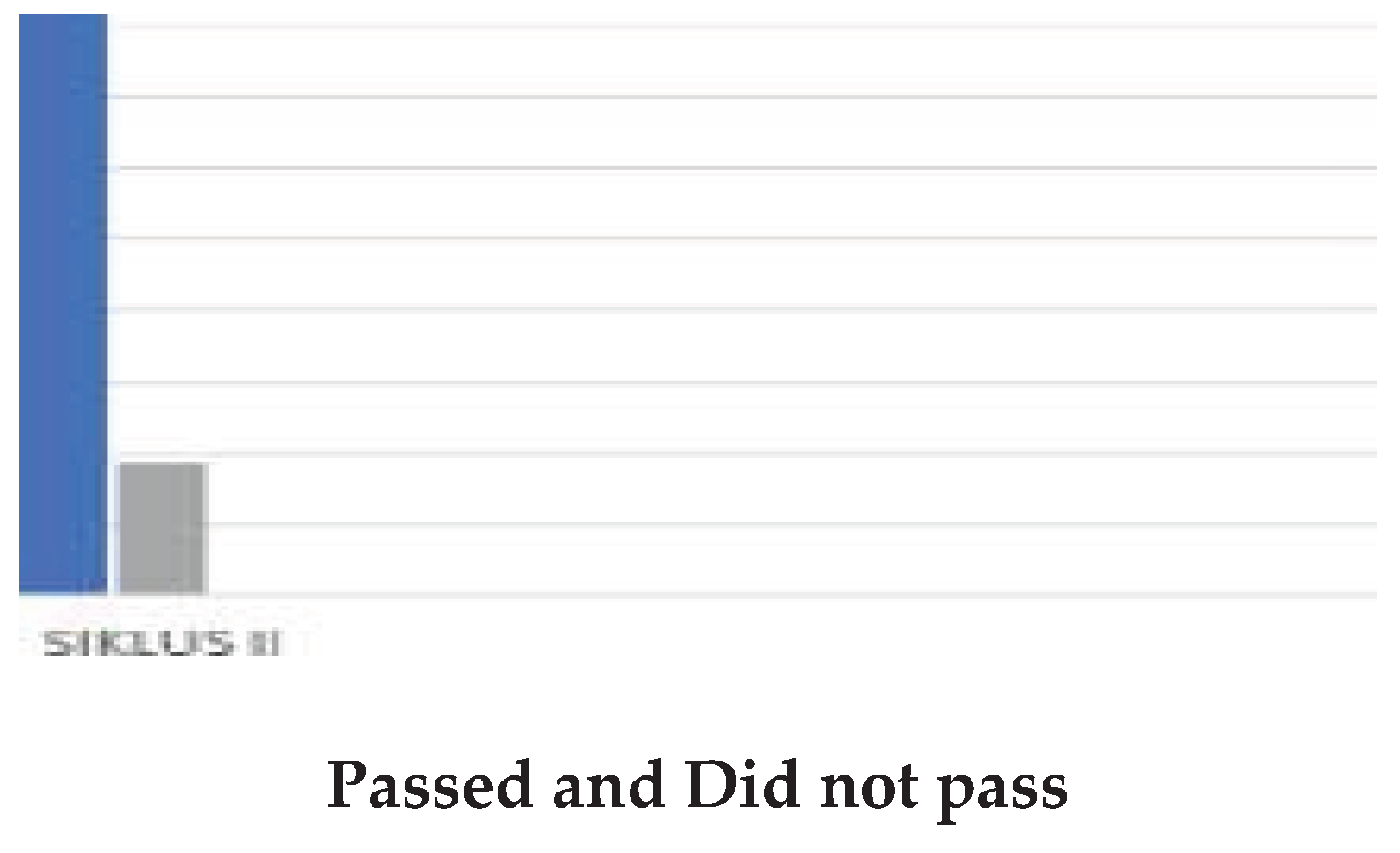

Cycle II Implementation and Outcomes

Cycle II was implemented over two sessions (totaling 4 instructional hours). The peer tutoring strategy was monitored using a validated observation checklist completed by the cooperating teacher. The cycle concluded with a post-intervention mathematical understanding test to evaluate the effectiveness of the instructional approach.

Results indicated a marked improvement in student performance. Although five students (18.5%) did not achieve the minimum mastery threshold, 22 students (81.4%) met or exceeded it. This mastery rate surpasses the predetermined success criterion of 75%, thereby confirming the efficacy of the revised peer tutoring implementation in enhancing mathematical comprehension.

Findings from Cycle II

As presented in

Table 3, the analysis of students’ mathematical understanding in Cycle II reveals a notable improvement. No student was classified in the

poor category. Specifically, 2 students (7.4%) scored in the

fair range, 3 students (11.1%) in the

good range, and 22 students (81.5%) achieved the

very good category.

Concurrently, student motivation showed marked enhancement. As shown in

Table 4, 13 students (48.1%) were categorized as having

very high motivation—reflecting strong enthusiasm and commitment to learning. An additional 10 students (37.0%) fell into the

high motivation category, indicating consistent engagement. Only 3 students (11.1%) demonstrated

moderate motivation, and just 1 student (3.7%) was classified as having

low motivation. Notably, no student was rated in the

very low category. These results collectively indicate a positive motivational climate conducive to academic achievement and signify that the intervention successfully met the study’s success criteria for learning motivation.

This improvement can be attributed to several contextual and pedagogical factors identified through systematic classroom observation conducted jointly by the researcher and the cooperating teacher throughout Cycle II.

Unlike Cycle I—where lessons were scheduled near the end of the school day—Cycle II sessions were held during the first period, when students exhibited higher alertness and energy levels. This scheduling change contributed significantly to increased attentiveness and participation. Moreover, the teacher demonstrated greater clarity and assertiveness in introducing the peer tutoring method, including explicit instructions on roles, expectations, and time management.

The lesson implementation closely followed the lesson plan, which enhanced instructional coherence and student focus. Students who had previously mastered the content actively supported their peers, fostering bidirectional, interactive discussions within groups. Consequently, requests for teacher assistance decreased markedly, and group discussions became more self-sustaining and collaborative.

Teacher performance in Cycle II was evaluated at 35 out of 40 points (87.5%), falling into the good category. Key strengths included:

(1) smooth and engaging delivery of the peer tutoring activity, with students visibly enjoying the collaborative process;

(2) high levels of student participation across most groups; and

(3) effective scaffolding that empowered students to take ownership of their learning.

Teacher performance in Cycle II was evaluated at 35 out of 40 points (87.5%), which falls under the “Good” performance category. This significant improvement reflects the teacher’s growing proficiency in implementing the peer tutoring method effectively and responsively within the classroom context. Several key strengths were observed during this cycle, each contributing to the overall success of the learning process and the enhancement of students’ mathematical understanding.

First, the delivery of the peer tutoring activity was smooth, well-structured, and engaging. The teacher demonstrated strong facilitation skills by clearly communicating lesson objectives, guiding group formation, and ensuring that each student understood their role as either tutor or tutee. The classroom environment became more dynamic and student-centered, with learners showing genuine enthusiasm for collaborative learning. This engagement was evidenced by active discussions, positive peer interactions, and a noticeable reduction in classroom anxiety compared to the previous cycle. The teacher’s ability to maintain a supportive and stimulating atmosphere contributed significantly to sustaining students’ motivation throughout the learning process.

Second, there was a marked increase in student participation across most peer groups. Nearly all students took part in group discussions, problem-solving, and peer explanations. This improvement indicates that the peer tutoring method successfully addressed earlier issues of passivity and uneven participation. Students who were previously hesitant to contribute became more confident, often seeking clarification or assisting their peers without direct teacher intervention. This behavioral shift reflects the effectiveness of the teacher’s strategy in creating equitable learning opportunities for all students, fostering both cognitive engagement and social collaboration.

Third, the teacher exhibited strong scaffolding skills that enabled students to take greater ownership of their learning. Instead of providing direct answers, the teacher guided students through probing questions, strategic hints, and constructive feedback that encouraged independent thinking. Such scaffolding promoted metacognitive awareness, helping students to reflect on their reasoning processes and to identify areas requiring improvement. Moreover, this approach aligns with [

20] theory of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), which emphasizes the importance of guided support in helping learners progress beyond their current level of competence.

The teacher’s facilitation also promoted reciprocal learning, where both tutors and tutees benefited cognitively and affectively. Tutors developed deeper conceptual understanding by explaining mathematical procedures to peers, while tutees gained confidence and comprehension through relatable peer explanations. The teacher’s role in orchestrating these interactions ensured that learning goals were met while maintaining a balance between autonomy and guidance.

Furthermore, the effective management of classroom time and transitions between instructional phases demonstrated the teacher’s improved pedagogical fluency. The smooth flow from explanation to peer collaboration, followed by reflection and feedback, ensured that students remained focused and engaged. This fluidity of instruction not only enhanced comprehension but also reinforced the perception of mathematics as an enjoyable and meaningful subject.

In addition, the teacher’s performance in maintaining positive classroom dynamics deserves recognition. The respectful and cooperative atmosphere encouraged students to share ideas freely, listen attentively, and value different problem-solving strategies. This cultural shift towards collaborative learning represents a crucial pedagogical achievement, particularly in mathematics classrooms where students often experience apprehension and competition.

Overall, the results of Cycle II indicate that the teacher has successfully internalized the principles of student-centered pedagogy and demonstrated strong professional growth in implementing the peer tutoring model. The observed improvements in classroom engagement, motivation, and comprehension collectively affirm that effective teacher performance plays a pivotal role in maximizing the benefits of peer-assisted learning.

The outcomes of this cycle highlight that when teachers act as facilitators—rather than sole knowledge transmitters—they create a learning environment that empowers students to construct knowledge collaboratively. Thus, the Cycle II evaluation underscores the teacher’s crucial contribution to achieving the research objectives: enhancing mathematical understanding and fostering motivation through active, inclusive, and well-guided peer tutoring practices.

A minor limitation was noted: two students initially struggled during group discussions, requiring targeted support to fully engage. However, this did not impede overall progress.

Overall Conclusions

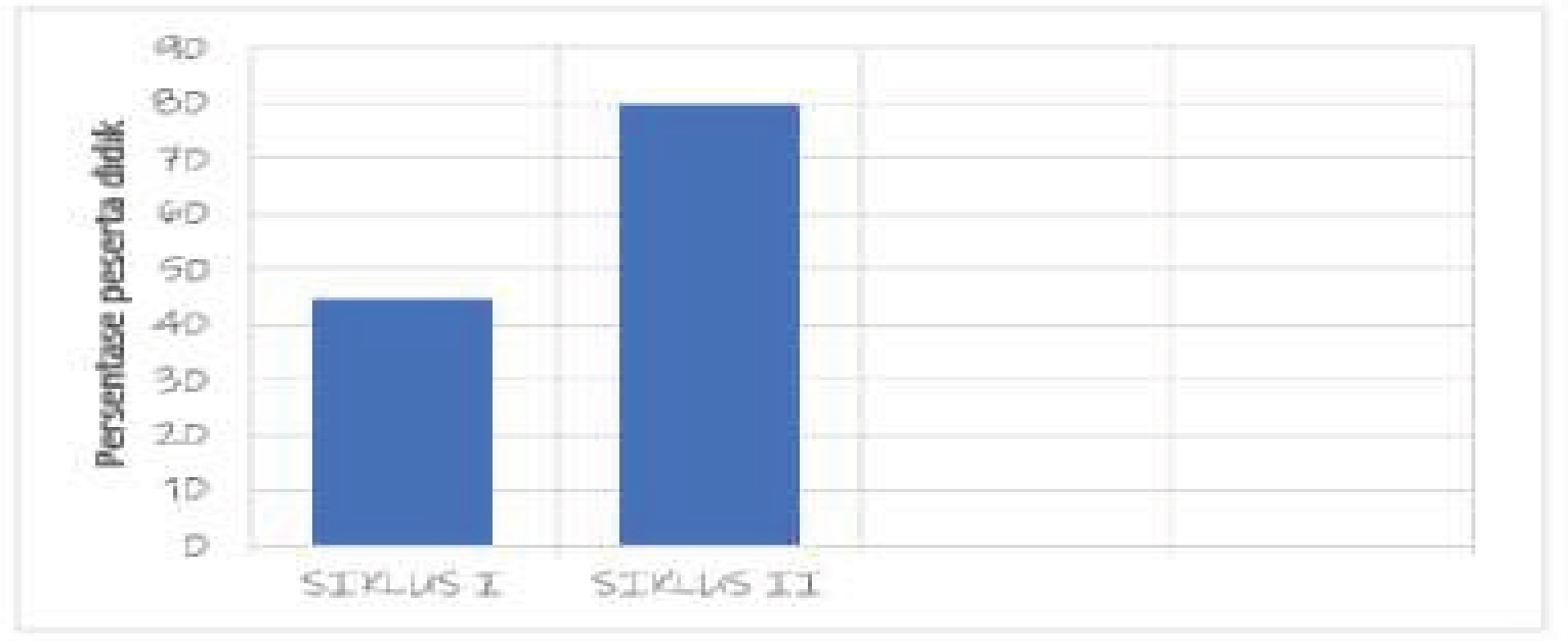

A comparative analysis of data from Cycles I and II confirms that the research objectives were successfully achieved by the end of Cycle II. Both mathematical understanding and learning motivation demonstrated statistically and pedagogically meaningful improvements. The mastery rate rose to 81.5%, surpassing the predetermined success threshold of 75%, while motivation levels shifted dramatically from predominantly low (Cycle I) to predominantly high/very high (Cycle II). These trends are visually summarized in the bar chart presented in Figure 2.

The findings underscore the effectiveness of well-structured peer tutoring—when implemented with clear guidelines, appropriate timing, and active teacher facilitation—in enhancing both cognitive and affective learning outcomes in middle school mathematics classrooms.

As illustrated in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, both students’ mathematical understanding ability and learning motivation demonstrated noticeable improvement across the two cycles. In each cycle, the teacher implemented the peer tutoring method and consistently provided motivational support to maintain student engagement throughout the learning process.

Despite these strengths, certain limitations were identified. First, not all students were fully engaged in the learning activities, indicating room for improvement in inclusive participation. Second, the evaluation test was administered only at the end of each cycle (i.e., after the second lesson), which limited opportunities for formative assessment and timely instructional adjustments.

As illustrated in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, students’ mathematical understanding and learning motivation demonstrated a steady upward trend across both learning cycles. The application of the peer tutoring method played a pivotal role in this progression, allowing students to engage in collaborative knowledge construction rather than relying solely on teacher-centered explanations. This shift toward active learning encouraged deeper conceptual comprehension and nurtured confidence in expressing mathematical ideas.

Throughout each cycle, the teacher systematically implemented peer tutoring strategies while simultaneously providing motivational reinforcement to sustain student enthusiasm. This dual focus on collaboration and motivation created a dynamic learning environment where students felt supported both cognitively and affectively. The encouragement given by peers and the teacher fostered a sense of belonging and responsibility, which is essential for maintaining long-term engagement.

The results revealed that peer tutoring enhanced not only academic outcomes but also interpersonal skills such as communication, cooperation, and empathy. Students who served as tutors developed leadership qualities and a deeper understanding of mathematical concepts, as teaching required them to clarify and reorganize their knowledge. Conversely, those who received guidance benefited from peer explanations that were often more relatable and less intimidating than formal teacher instruction.

Motivational factors also played a crucial role in determining the success of this approach. Students with higher intrinsic motivation were more likely to participate actively, seek clarification, and persist through challenging problems. The teacher’s consistent reinforcement—through praise, feedback, and encouragement—acted as an extrinsic motivator that complemented the students’ internal drive to succeed.

According to the classroom observations, Cycle II exhibited a more collaborative and enthusiastic atmosphere compared to Cycle I. Students were seen discussing mathematical problems more openly, exchanging strategies, and demonstrating curiosity about different problem-solving methods. This behavioral shift indicated that the classroom culture had evolved into a learning community characterized by mutual support and shared responsibility.

Teacher performance also improved significantly during Cycle II, with an evaluation score of 35 out of 40 (87.5%), categorizing it as good. The teacher demonstrated smoother facilitation of peer tutoring activities and displayed better classroom management skills. Students responded positively to this improved guidance, showing enjoyment and sustained attention during group tasks. These observations underline the importance of the teacher’s role as a facilitator rather than a sole source of information.

Nevertheless, despite these strengths, certain limitations persisted throughout the study. Not all students were equally engaged in the learning process, as some displayed passive tendencies or relied heavily on their peers’ efforts. This highlights the need for differentiated strategies to ensure more equitable participation across diverse student profiles. Encouraging quieter or less confident learners to take active roles remains a critical challenge for future implementations.

Another limitation concerns the timing of the evaluation tests, which were conducted only at the end of each cycle. This approach limited opportunities for formative assessment and hindered the ability to provide timely feedback for individual improvement. Incorporating short, ongoing assessments during the learning process could enhance responsiveness and enable adaptive instruction tailored to students’ evolving needs.

To further strengthen the impact of peer tutoring, future studies could integrate technological tools or digital platforms that facilitate interaction, such as online discussion boards or collaborative apps. These tools may help increase engagement among less active students while also enabling real-time feedback from both peers and instructors. Combining digital support with peer tutoring could promote inclusivity and ensure continuous learning beyond the classroom context.

The findings from both cycles affirm that the peer tutoring method, when complemented by sustained motivational support, can substantially enhance students’ mathematical understanding and learning motivation. While some areas still require improvement—particularly in promoting inclusivity and incorporating formative assessment—the overall outcomes demonstrate the transformative potential of collaborative learning in mathematics education. The study underscores that meaningful learning occurs not only through individual effort but also through collective interaction, reflection, and mutual empowerment.