1. Introduction

Elite sport offers a unique experimental model for studying the adaptive limits of human physiology. Through rigorous training, specialized nutrition, and—in some cases—the use of pharmacological agents, athletes continuously push cellular systems to optimize energy flux, recovery, and performance. These strategies rely on the dynamic regulation of energy-sensing pathways, particularly the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR), which together orchestrate the balance between catabolic and anabolic metabolism [

1,

2,

3]. Under normal conditions, this oscillation ensures efficient substrate use, mitochondrial quality control, and tissue repair. However, chronic stimulation of anabolic pathways by nutrient overload, supplementation, or doping may lead to a loss of regulatory balance—a state of

metabolic overdrive [

4,

5].

Recent advances in molecular physiology and nutrition research have revealed that nutrient-sensitive signaling cascades not only control energy metabolism but also influence the epigenetic landscape of the cell. Modifications such as DNA methylation, histone acetylation, and noncoding RNA expression act as metabolic sensors, translating nutritional and redox states into gene-regulatory outcomes [

6,

7,

8]. This has profound implications for both performance enhancement and disease risk, as dysregulated AMPK–mTOR activity and oxidative stress can promote aberrant DNA methylation, genomic instability, and tumorigenic signaling [

9,

10,

11].

While exercise is broadly recognized as protective against metabolic and oncologic disorders, the extremes of performance physiology may blur the boundary between adaptation and pathology. The overlap between anabolic signaling in hypertrophying muscle and in proliferating cancer cells raises an important question: can the biological mechanisms that drive elite performance also predispose to molecular instability when chronically overstimulated? This issue is particularly relevant in the context of nutritional excess and ergogenic aids, which can amplify both anabolic and oxidative stress pathways [

12,

13].

The present review aims to synthesize current evidence on the interactions between nutritional signaling, AMPK–mTOR regulation, oxidative stress, and epigenetic drift, using elite sport as a conceptual framework for exploring the limits of human adaptation. By integrating findings from molecular nutrition, exercise physiology, and cancer biology, this work proposes a mechanistic model of metabolic overdrive that may help clarify how chronic anabolic stimulation affects both performance optimization and long-term cellular stability.

2. Mechanistic Synthesis

This section integrates existing molecular evidence into a mechanistic synthesis rather than reporting new experimental results; emphasis is placed on feedback topology (AMPK–mTOR antagonism, SIRT1–PARP NAD+ economy) and energetic context.

2.1. Nutritional Signaling and the AMPK–mTOR Axis

Energy and nutrient availability act as master regulators of metabolic homeostasis, governing the balance between catabolism and anabolism in virtually all eukaryotic cells. The AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) represent the two central signaling nodes coordinating this metabolic dialogue [

1,

2,

3]. AMPK acts as a low-energy sensor activated by an increased AMP/ATP ratio through the upstream kinase LKB1 and the calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase kinase β (CaMKKβ) [

14]. Once activated, AMPK phosphorylates multiple downstream targets, including acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1α (PGC-1α), thereby enhancing glucose uptake, fatty-acid oxidation, and mitochondrial biogenesis [

15].

mTOR, in contrast, serves as a nutrient and growth sensor, existing in two complexes—mTORC1 and mTORC2—with distinct regulatory roles. mTORC1 responds primarily to amino-acid sufficiency, insulin, and growth factors to promote ribosomal biogenesis, protein synthesis, and lipid production via activation of p70S6 kinase (S6K1) and inhibition of the eukaryotic initiation factor 4E-binding protein (4E-BP1) [

5,

6,

16]. mTORC2, conversely, modulates cell survival and cytoskeletal organization through AKT and SGK1 signaling [

17]. This bidirectional interplay ensures metabolic flexibility, where AMPK activation under energy stress suppresses mTORC1 through phosphorylation of tuberous sclerosis complex 2 (TSC2) and raptor, whereas sufficient energy and amino acids reverse the inhibition, restoring anabolic signaling [

18].

In skeletal muscle, this AMPK–mTOR oscillation underpins the molecular basis of

training–fuel coupling [

8,

19]. During exercise, AMPK activation favors catabolic fluxes—autophagy, lipid oxidation, and mitochondrial turnover—essential for energetic recovery. Following exercise, nutrient repletion and growth signals transiently reactivate mTOR to promote hypertrophy and protein synthesis. Such rhythmic alternation maintains

metabolic flexibility, defined as the capacity to efficiently switch between oxidative and glycolytic metabolism depending on substrate availability [

20].

However, chronic nutrient oversupply or pharmacologic stimulation can flatten this oscillatory pattern. High-protein or high-carbohydrate diets with constant amino-acid and insulin stimulation maintain mTORC1 activation and suppress AMPK-mediated checkpoints [

9,

10]. The resulting anabolic “lock-in” diminishes autophagy, impairs mitophagy, and exacerbates mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) production [

21]. This oxidative burden promotes endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, unfolded protein response (UPR) activation, and redox imbalance, compromising mitochondrial quality control [

22,

23]. In the long term, these processes may contribute to insulin resistance, inflammation, and epigenetic dysregulation, mirroring several molecular hallmarks of tumorigenesis [

24].

Nutritional factors can either exacerbate or mitigate this imbalance. Amino acids such as leucine and methionine are potent mTORC1 activators through Rag GTPase signaling [

25], whereas bioactive compounds like resveratrol, curcumin, and epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) stimulate AMPK and restore redox equilibrium [

26,

27,

28]. Caloric restriction, intermittent fasting, and endurance training represent physiological strategies that periodically reactivate AMPK and improve mitochondrial efficiency [

29,

30]. Conversely, chronic overfeeding or supplementation-driven anabolic excess perpetuates mTOR dominance, driving

metabolic overdrive—a state of sustained anabolism, suppressed autophagy, and cumulative oxidative and epigenetic stress [

31].

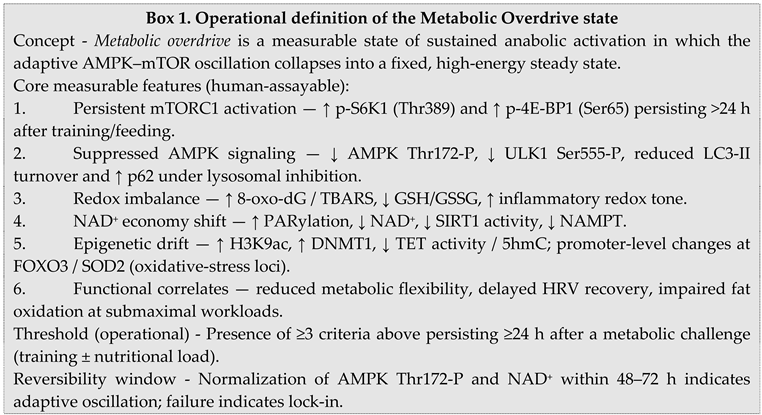

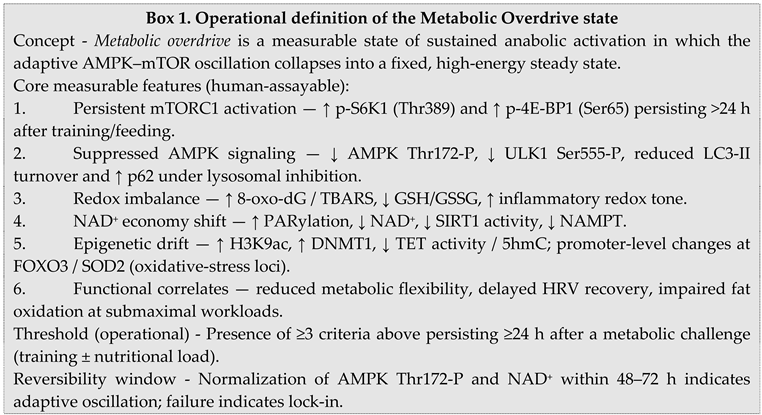

To make this construct actionable in human studies, we define an operational set of criteria for the metabolic overdrive state (Box 1).

At the systems level, the AMPK–mTOR axis acts as a molecular interface between nutrition, metabolism, and growth signaling. Understanding how dietary and pharmacological interventions modulate this crosstalk is crucial for defining the threshold between adaptive remodeling and pathological overload in elite performance contexts. In this review, the AMPK–mTOR regulatory dyad serves as the central mechanistic framework through which nutritional signaling connects energy balance, redox homeostasis, and epigenetic stability. Together, these signaling nodes form an adaptive triad that integrates energetic demand, substrate availability, and anabolic drive. Their dynamic cross-regulation ensures that catabolic and anabolic fluxes oscillate in harmony, preserving mitochondrial integrity and metabolic flexibility across varying nutritional states. The principal components and interactions of this network are summarized in

Table 1, which integrates upstream regulators, downstream targets, and physiological outcomes of AMPK–mTOR–SIRT1 coordination.

Following this integrative overview, it becomes evident that sustained nutrient stimulation or pharmacological enhancement may disturb this oscillatory equilibrium, driving metabolic overdrive and initiating downstream redox and epigenetic consequences.

2.2. Molecular Parallels between Performance Enhancement and Tumorigenesis

The molecular architecture of performance adaptation shares striking similarities with the signaling networks that drive oncogenic growth. Both rely on sustained anabolic activation, redox modulation, and metabolic reprogramming to support energy-intensive biosynthesis. Central to this overlap is the insulin/IGF-1–PI3K–AKT–mTOR cascade, which governs nutrient sensing and cell growth. In skeletal muscle, transient activation of this pathway stimulates protein synthesis and hypertrophy following training or nutritional stimuli. However, chronic hyperactivation through excessive caloric intake, anabolic steroids, or exogenous insulin-like factors may disrupt the homeostatic balance between growth and repair [

32,

33]. Continuous mTORC1 stimulation bypasses AMPK checkpoints, promoting unrestrained anabolism and attenuated autophagy—features that closely parallel those of neoplastic proliferation [

34,

35]. Detailed analysis of neuromuscular adaptations to strength and plyometric training has further clarified how anabolic drive interacts with adaptive signaling cascades at the molecular level, highlighting the fine boundary between beneficial remodeling and pathological overactivation [

36].

Insulin and IGF-1 signaling are among the most studied molecular links between nutrition, muscle hypertrophy, and cancer biology. Both ligands activate receptor tyrosine kinases, leading to PI3K–AKT phosphorylation cascades that enhance glucose uptake, inhibit FOXO-dependent catabolic genes, and suppress apoptosis [

37]. While beneficial for short-term adaptation, persistent activation of this axis contributes to insulin resistance and tumorigenic potential by stabilizing mTORC1 activity and driving oxidative and ER stress [

38]. Epidemiological data support this duality: hyperinsulinemic states and high circulating IGF-1 are associated with increased cancer risk in metabolic diseases and overnutrition [

39,

40].

Another converging mechanism involves the hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) pathway, which is upregulated both during intense exercise and in the hypoxic microenvironment of tumors. In athletes, HIF-1α activation promotes angiogenesis, mitochondrial remodeling, and erythropoietin (EPO) production to improve oxygen delivery [

41]. In tumors, the same transcriptional program drives vascularization, glycolytic enzyme expression, and cell survival under hypoxia [

42]. Exogenous EPO administration—a doping practice in endurance sports—mimics this pathway, further elevating HIF-1α and VEGF signaling, a pattern that resembles oxidative and genomic stress responses observed in other high-drive systems. [

43,

44]. Although EPO doping in athletes differs mechanistically from tumor hypoxia, the shared molecular endpoints—ROS generation, mitochondrial remodeling, and DNA repair stress—highlight a conserved bioenergetic logic across physiological and pathological adaptation.

Oxidative stress represents another axis of convergence. Both exercise and cancer involve transient ROS production; however, chronic oxidative overload shifts ROS from signaling intermediates to damaging agents. In skeletal muscle, ROS act as secondary messengers activating AMPK, PGC-1α, and MAPK cascades, mediating adaptation to endurance training [

45]. Yet under sustained nutrient excess or pharmacologic overstimulation, antioxidant defenses become insufficient, leading to lipid peroxidation, mitochondrial DNA damage, and redox-dependent epigenetic drift [

46]. This imbalance recapitulates the oxidative phenotype of cancer cells, where mitochondrial dysfunction, NADPH oxidase upregulation, and impaired mitophagy promote genomic instability [

47,

48].

Finally, both hypertrophying muscle and proliferating cancer cells display a metabolic preference for aerobic glycolysis—a phenomenon akin to the

Warburg effect [

49]. During high-intensity training or anabolic stimulation, increased glycolytic flux provides rapid ATP and biosynthetic precursors (e.g., serine, glycine, acetyl-CoA) for protein and nucleotide synthesis. In cancer, this same metabolic configuration supports biomass accumulation and redox control. The intersection of glycolytic metabolism, one-carbon flux, and methyl donor availability also affects epigenetic regulation, as enzymes in the methionine and folate cycles are tightly coupled to cellular redox and energy status [

50,

51]. Persistent activation of these nutrient–signaling circuits, particularly when combined with exogenous ergogenic aids, may therefore shift the metabolic landscape from adaptive remodeling toward oncogenic instability.

Understanding these parallels does not imply causality between performance enhancement and cancer but rather underscores the shared molecular economy underlying growth, repair, and survival. Both systems exploit nutrient-driven signaling to optimize function—one physiologic, the other pathologic. Distinguishing where adaptation ends and instability begins remains a key challenge in deciphering the limits of metabolic plasticity in elite athletes.

The mechanistic parallels between anabolic adaptation and oncogenic signaling are summarized in

Table 2, which integrates key physiological drivers, molecular mediators, and pathological counterparts that illustrate the shared architecture of metabolic overdrive across sport and cancer biology.

This convergence underscores how anabolic, oxidative, and epigenetic pathways form a common biochemical language between adaptation and disease. When sustained beyond physiological thresholds, the same nutrient-sensing mechanisms that promote recovery and remodeling can drive instability, genomic stress, and redox imbalance. These transitions define the mechanistic foundation for the next section, which explores how metabolic stress reshapes the epigenetic landscape through redox-dependent signaling and NAD+-linked regulation

2.3. Epigenetic Modulation under Metabolic Stress

The interface between metabolism and epigenetics has emerged as one of the defining discoveries of modern molecular physiology. Cellular energy flux dictates the availability of cofactors that directly modify chromatin, making metabolism not merely a supplier of energy but an active governor of gene expression. Enzymes responsible for DNA and histone modifications depend on metabolites such as S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), acetyl-CoA, α-ketoglutarate (α-KG), and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD

+) [

52]. These metabolites serve as dynamic reporters of the nutritional and redox environment: changes in diet, exercise load, or mitochondrial efficiency immediately reverberate in the epigenome.

In low-energy states, AMPK activation promotes NAD

+ synthesis through the salvage enzyme NAMPT, which in turn enhances SIRT1 activity. SIRT1 deacetylates histones H3 and H4 and transcriptional regulators such as PGC-1α, FOXO, and p53, thereby promoting oxidative metabolism, autophagy, and stress resistance [

53]. This AMPK–SIRT1–PGC-1α axis epitomizes a nutrient-sensing feedback that maintains chromatin compactness and genomic integrity during caloric scarcity. In contrast, nutrient oversupply generates abundant acetyl-CoA and SAM, driving histone hyperacetylation and DNA hypermethylation at promoters of oxidative and stress-response genes [

54,

55]. The chromatin thus “remembers” energy abundance through an anabolic epigenetic imprint.

DNA Methylation and Histone Acetylation in Exercise and Overload - exercise transiently remodels the skeletal muscle methylome. Acute endurance sessions induce hypomethylation at promoter CpG sites of metabolic regulators such as

PGC-1α,

PDK4, and

TFAM, facilitating transcriptional activation and mitochondrial biogenesis [

56]. Over repeated training cycles, this hypomethylated pattern stabilizes, giving rise to the so-called

epigenetic memory of exercise, which persists even after detraining [

57,

58]. Such “memory” reflects a primed chromatin state that accelerates re-adaptation upon retraining — a beneficial example of epigenetic plasticity.

However, this flexibility has limits. When nutrient intake, supplementation, or anabolic pharmacology impose chronic mTOR activation, the methylome drifts toward hypermethylation of catabolic and antioxidant genes (

FOXO3,

SOD2,

CAT) and hypomethylation of anabolic and proliferative loci (

IGF1,

MYC,

mTOR) [

59,

60]. The resulting transcriptional asymmetry mirrors the epigenetic architecture of many cancers, in which DNA methylation suppresses checkpoints and reinforces growth signaling [

61]. Histone acetylation patterns behave analogously: during caloric restriction or endurance training, reduced acetyl-CoA levels and increased SIRT activity condense chromatin and favor repair pathways, whereas chronic nutrient overload expands chromatin through HAT activation (notably p300/CBP and GCN5) and enhances transcription of biosynthetic programs [

62,

63].

The Sirtuin–PARP Axis: NAD

+ Competition and Redox Imbalance - a less visible but crucial intersection between metabolism and the epigenome lies in NAD

+ partitioning between sirtuins and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARPs). Both enzyme families consume NAD

+, but for divergent purposes: sirtuins preserve mitochondrial function and genomic stability via deacetylation, while PARPs respond to DNA damage by poly-ADP-ribosylation, a repair signal [

63]. Under chronic oxidative stress, excessive PARP activation depletes NAD

+, silencing sirtuin activity and collapsing the AMPK–SIRT1 axis [

64]. This shift diverts energy from repair and metabolic regulation toward futile cycles of DNA damage and inflammatory signaling — a mechanism shared by overtrained muscle and tumor cells. Nutritional or pharmacological activation of AMPK (via resveratrol, berberine, or caloric restriction) can rebalance this NAD

+ economy, restoring redox homeostasis and chromatin fidelity [

26,

29].

MicroRNAs and Translational Noise - microRNAs (miRNAs) represent an additional, fast-acting mechanism through which metabolic stress reshapes the adaptive landscape. Several miRNAs — notably miR-1, miR-133a, miR-206, and miR-378 — coordinate muscle differentiation, mitochondrial turnover, and oxidative defense [

64,

65]. Endurance training typically upregulates oxidative miRNAs (miR-494, miR-181a) that enhance PGC-1α signaling, whereas resistance or overload training preferentially increases miR-378 and miR-486, which promote hypertrophy [

66]. Chronic nutrient and redox stress, however, destabilize this regulatory network, producing aberrant miRNA expression such as persistent miR-21 or miR-34a overexpression, both associated with fibrotic remodeling and oncogenic pathways [

67,

68]. In this context, miRNAs act as both messengers and memory traces of metabolic experience — biomarkers that reflect whether adaptation remains reversible or slides toward pathology.

From Metabolic Flexibility to Epigenetic Drift - epigenetic mechanisms are inherently reversible, yet their reversibility is time- and context-dependent. Prolonged oxidative overload exhausts α-KG and NAD

+ pools, while accumulating succinate and fumarate — competitive inhibitors of TET and Jumonji demethylases [

69]. This inhibition stabilizes aberrant histone and DNA methylation, anchoring the chromatin in maladaptive configurations. Mitochondrial dysfunction amplifies this process through disrupted one-carbon flux and altered SAM/SAH ratios, leading to global methylation instability [

70,

71].

The term

epigenetic drift describes this cumulative loss of methylation precision across the genome. In cancer and aging, drift manifests as hypervariable methylation, local hypomethylation, and transposon reactivation. In the context of high-performance sport, analogous processes might underlie the progressive reduction in adaptive potential observed in chronically overloaded athletes. Methylation noise could blunt the genomic responsiveness to training stimuli, a molecular correlate of the overtraining syndrome [

72].

Such convergence of redox imbalance, NAD+ depletion, and methylation drift reveals a unifying framework: the same biochemical plasticity that enables human adaptation also contains the seeds of instability. The oscillation between anabolic expansion and catabolic renewal—between acetylation and deacetylation, methylation and demethylation—is the molecular rhythm of life. When that rhythm is flattened by nutritional excess or pharmacologic drive, the epigenome ceases to dance to the music of adaptation and begins to echo the static of disease.

The principal metabolic–epigenetic mechanisms are summarized in

Table 3, which integrates molecular cofactors, enzymatic regulators, and evidence from elite sport to illustrate how nutrient-driven signaling shapes the reversible—or progressive—nature of epigenetic remodeling.

These findings consolidate the concept that metabolism and chromatin function as two interlocked systems, each continuously rewriting the state of the other. In elite athletes, periodic metabolic stress through training and recovery fosters a reversible form of epigenetic plasticity, allowing performance optimization without molecular instability. Yet, when this oscillation is flattened by chronic overnutrition, excessive supplementation, or pharmacological drive, the same adaptive machinery turns against itself.

Redox imbalance, NAD+ depletion, and one-carbon overload jointly erode the fidelity of chromatin signaling, promoting transcriptional noise and cumulative methylation drift. This progression defines a redox-epigenetic continuum that bridges adaptive exhaustion in sport with genomic instability in disease.

2.4. Case Contexts: Elite Sport and Doping Paradigms

This section describes molecular parallels and health risks associated with performance-enhancing practices; it does not imply causation or endorsement of such interventions.

Elite sport represents an unparalleled natural laboratory for studying the extremes of human adaptation — and, occasionally, its pathologies. The metabolic ambition to optimize performance often blurs into a gray zone where physiology meets pharmacology. Recent advances in artificial intelligence now assist in identifying performance determinants in elite team sports, offering data-driven perspectives on training load, nutritional status and adaptive physiology [

73]. Big-data analytical frameworks further enhance such decision-making processes by integrating multivariate performance, physiological, and contextual metrics [

74]. The interplay between

training, nutrition, and doping creates an environment of sustained metabolic stimulation rarely encountered in any other context. This section examines how performance-enhancing practices recapitulate the molecular features of

metabolic overdrive and

epigenetic destabilization described earlier.

Endurance Sports and the Hypoxic–Erythropoietic Axis - endurance sports such as professional cycling provide the most emblematic example of physiological adaptation pushed to its biochemical edge. Chronic endurance training induces a hypoxia-like signaling pattern characterized by transient stabilization of HIF-1α, activation of erythropoietin (EPO), angiogenic remodeling, and mitochondrial biogenesis [

75,

76]. These responses are adaptive under normal conditions, improving oxygen transport and aerobic metabolism. However, exogenous EPO administration and blood transfusions — practices widely documented in professional cycling during the 1990s and early 2000s — exaggerated this system far beyond physiological boundaries [

77].

Artificially elevated hematocrit increases oxygen-carrying capacity but imposes hemodynamic strain, oxidative load, and erythroid proliferation. Sustained HIF-1α activity amplifies ROS generation and promotes a metabolic shift toward glycolysis and lactate accumulation even at rest [

78]. In the long term, such

pseudo-hypoxic signaling profiles are indistinguishable, at the molecular level, from tumor hypoxia responses, featuring upregulation of VEGF, GLUT1, and glycolytic enzymes [

42,

79]. Moreover, EPO itself acts as a growth and survival factor beyond erythroid cells, activating JAK2–STAT5 and PI3K–AKT pathways implicated in cancer progression [

80]. While no causal link exists between EPO doping and malignancy, its signaling footprint overlaps substantially with pro-oncogenic pathways, illustrating how chronic stimulation of adaptive systems can drift toward dysregulation.

Strength Sports and the Anabolic–Epigenetic Axis - bodybuilding and other strength disciplines push the opposite side of the metabolic spectrum: sustained activation of the IGF-1–AKT–mTOR axis through resistance training, high-protein diets, and anabolic–androgenic steroids (AAS). Supraphysiological androgen exposure amplifies protein synthesis and suppresses catabolic genes via AR–mTORC1 crosstalk, while exogenous growth hormone (GH) and insulin potentiate this effect through the IGF-1 receptor [

81,

82,

83]. In muscle tissue, these stimuli enlarge fiber cross-sectional area but also suppress autophagy, reduce mitochondrial density, and generate oxidative stress [

84].

Recent molecular profiling of long-term AAS users revealed persistent epigenetic modifications, including hypomethylation of hypertrophy-related genes and hypermethylation of stress-response pathways, consistent with the “epigenetic memory” of drug-induced adaptation [

85]. Moreover, chronic AAS exposure alters liver methylation and acetylation profiles, induces gene-expression signatures that overlap with hepatocellular carcinoma profiles, without implying causal progression. [

86]. Case studies of elite bodybuilders who developed cardiac hypertrophy, hepatic adenomas, or renal neoplasms suggest that these effects appear molecularly traceable, though no causal inference can be drawn [

87].

Nutritionally, high-protein intakes exceeding 3 g·kg

−1·day

−1, coupled with insulinotropic supplements and carbohydrate overfeeding, sustain mTOR activation while suppressing AMPK and SIRT1 activity [

88]. The resulting anabolic lock-in mirrors the metabolic rigidity described in cancer cells: persistent mTORC1 signaling, reduced autophagic flux, and redox imbalance [

9,

31]. This creates a cellular environment favoring DNA damage and aberrant methylation. When compounded with androgen-driven oxidative metabolism, the milieu becomes one of

metabolic overdrive — high energy throughput but low regulatory elasticity.

Hormonal Manipulation and “Metabolic Doping” - beyond classical anabolic agents, a new frontier of

metabolic doping targets pathways originally intended for therapeutic modulation. Thyroid hormones, β2-agonists (e.g., clenbuterol), insulin, and selective AMPK modulators (AICAR, metformin) have been misused by athletes to alter substrate utilization or enhance endurance [

89,

90]. These agents interfere directly with metabolic sensors and cofactor pools, producing unpredictable downstream effects on the epigenome. For instance, AICAR activates AMPK pharmacologically and can mimic the transcriptional signature of endurance training, whereas clenbuterol overstimulates adrenergic pathways and induces mitochondrial uncoupling [

91,

92]. Chronic manipulation of these sensors may uncouple the finely tuned oscillation between AMPK and mTOR, destabilizing redox balance and epigenetic control.

Ethical and Biomedical Implications - the molecular parallels between performance optimization and disease raise ethical and medical questions that transcend doping control. Current anti-doping frameworks focus on detection and fairness, yet the long-term health consequences of chronic metabolic stimulation remain insufficiently understood. Persistent alterations in DNA methylation, histone acetylation, and microRNA networks could represent a form of

molecular scarring that outlasts pharmacological exposure. This concept reframes the notion of “clean recovery”: molecular homeostasis may take years to restore, and in some cases, residual epigenetic instability could persist indefinitely [

93].

The cases of high-profile endurance and strength athletes — from those involved in EPO-era cycling to long-term steroid users in bodybuilding — exemplify how human physiology can be optimized to the edge of self-destruction. Their bodies serve as extreme testbeds where metabolic and epigenetic mechanisms of adaptation, plasticity, and degeneration converge. Understanding these processes is not merely an exercise in moral scrutiny but an opportunity to learn how the same molecular programs that sustain elite performance can, under persistent drive, erode the genomic architecture they were meant to enhance.

The integrated dynamics of oxidative metabolism and chromatin remodeling are summarized in

Table 4, illustrating how redox flux and epigenetic regulation form a unified feedback architecture that defines the physiological and pathological boundaries of adaptation.

Together, these findings delineate a dynamic equilibrium in which oxidative metabolism and chromatin architecture continually inform one another. Within this circuit, redox flux is not simply a by-product of energy turnover but a transcriptional signal that encodes the metabolic state into chromatin memory. As long as this feedback remains oscillatory—alternating between activation and recovery—the system preserves its resilience. When that oscillation collapses under continuous anabolic or oxidative drive, the feedback loop loses its corrective power, locking the cell into a state of sustained activation.

At this point, adaptation ceases to be reversible. The biochemical symphony that once synchronized energy use, redox balance, and gene regulation turns into a self-perpetuating echo of stress. What begins as performance optimization thus converges, mechanistically, toward the molecular grammar of instability.

2.5. The Metabolic Overdrive Model

Across the spectrum of elite performance, metabolic adaptation is characterized by oscillations between catabolic and anabolic states — a rhythmic negotiation between energy depletion and restoration. In physiological balance, this oscillation forms a closed adaptive loop governed by reciprocal activation of AMPK and mTOR, periodic fluctuations in redox tone, and reversible epigenetic remodeling. The loop functions as an information-processing system: metabolic cues are encoded as transient chemical modifications on chromatin, which in turn regulate the next cycle of energy flux.

From Oscillation to Lock-In - in the adaptive state, AMPK activation during energetic stress initiates autophagy, mitochondrial renewal, and chromatin deacetylation through SIRT1. During recovery, nutrient abundance and growth signals transiently activate mTORC1, promoting protein synthesis and tissue repair. This rhythmic succession of AMPK–mTOR–SIRT1 signaling maintains metabolic flexibility, minimizes oxidative stress, and preserves epigenetic plasticity.

Metabolic overdrive arises when this rhythm collapses into a static state of chronic anabolism. Persistent nutrient or hormonal stimulation suppresses AMPK checkpoints, silences sirtuins, and locks mTORC1 in constitutive activation. The system transitions from oscillation to saturation — energy continues to flow, but regulatory feedback weakens. Elevated acetyl-CoA, NADH/NAD

+ imbalance, and ROS accumulation feed forward into histone hyperacetylation and aberrant DNA methylation [

93,

94]. The epigenome, once adaptive, becomes entrained to a pathological steady state: hypertranscriptional but inflexible.

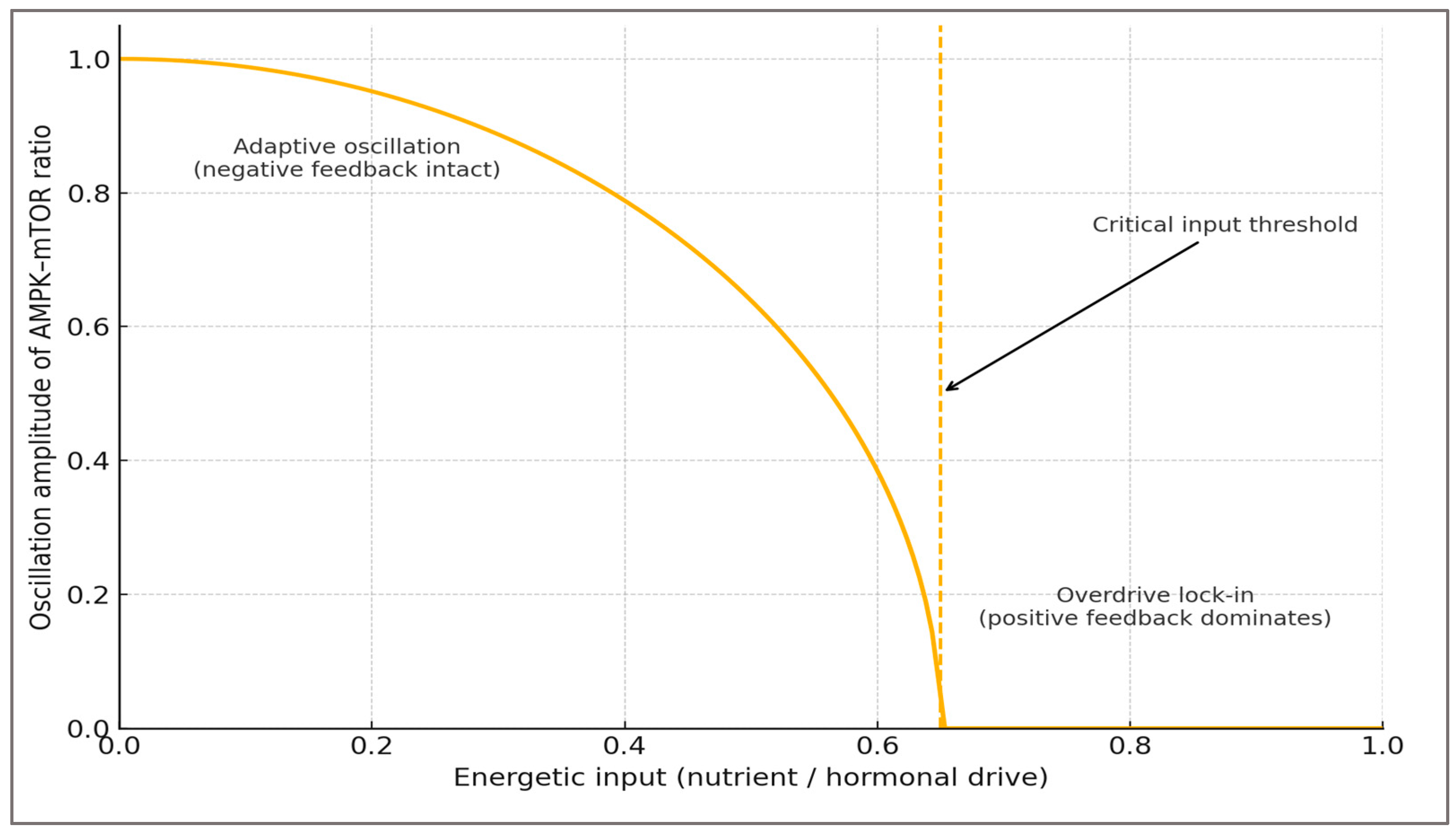

Formal view - The dynamics can be approximated as a loss-of-oscillation (Hopf-like) bifurcation: as energetic input (nutrient/hormonal drive) increases, the amplitude of the AMPK–mTOR oscillation diminishes toward zero; beyond a critical input threshold, the oscillatory attractor disappears and the system converges to a single high-anabolic steady state (mTORC1-dominant “lock-in”).

For conceptual clarity, the oscillatory behavior of the AMPK–mTOR system can be represented by a minimal three-variable model:

where A = AMPK activity, M = mTORC1 activation, and N = NAD

+ pool, while ηᵢ represent stochastic fluctuations. Increasing energetic or hormonal input raises k

4 and suppresses k

5, weakening negative feedback from AMPK to mTOR. Numerical simulation under these constraints yields a Hopf-like transition: oscillation amplitude decreases until the system collapses to a high-M steady state. This simplified structure captures the loss-of-oscillation threshold illustrated in

Figure 1.

Bridge to architecture - Operationally, the threshold in Figure 1 maps onto the Box 1 criteria: persistence >24 h of ↑p-S6K1/4E-BP1 with ↓AMPK Thr172-P, accompanied by NAD+ depletion / ↑PARylation and redox/epigenetic drift. This is the measurement logic summarized in Table 6.

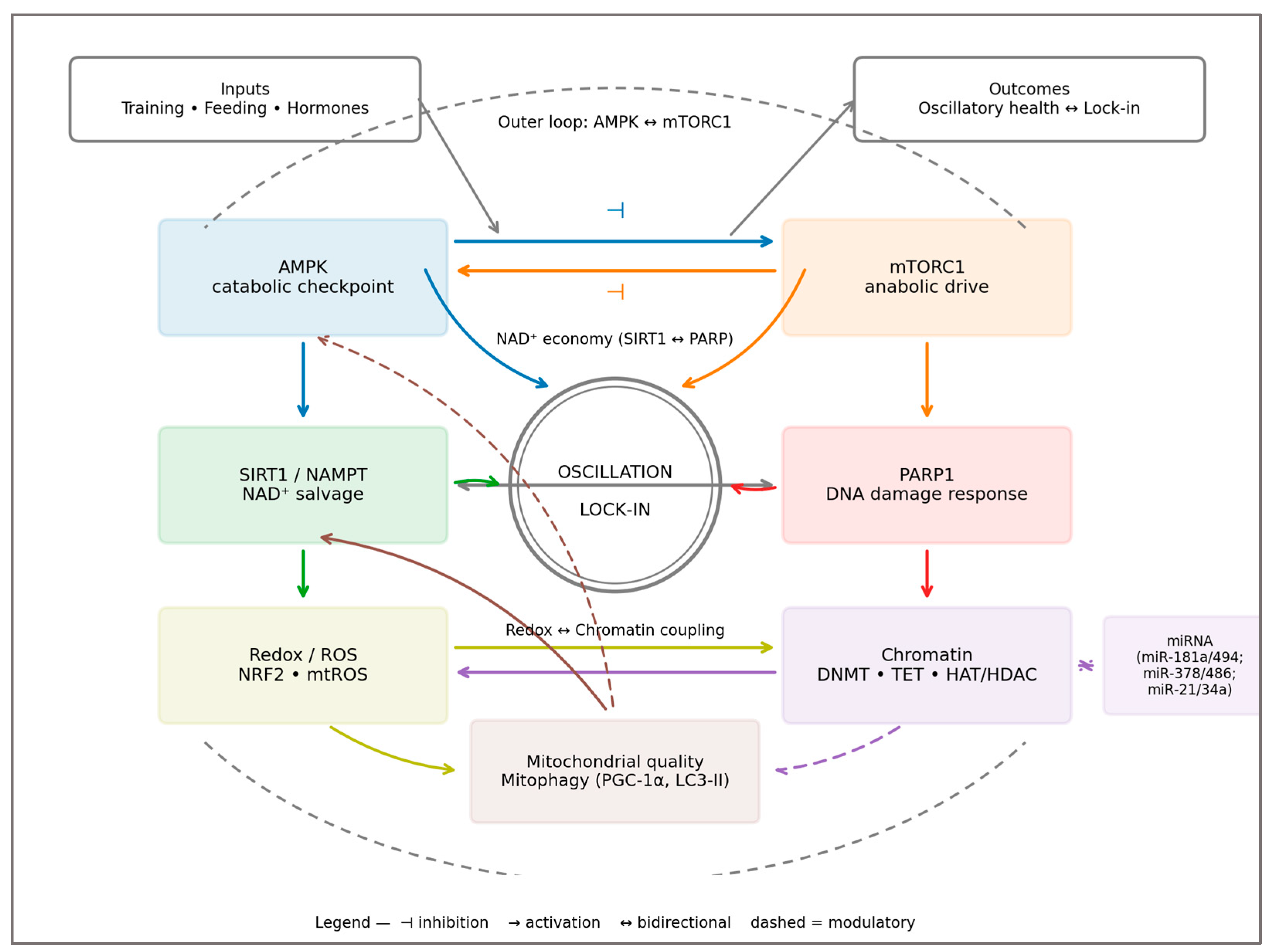

The Closed-Loop Architecture of Adaptation -

Figure 2 (conceptual diagram) illustrates the dual loop underpinning these dynamics: the outer AMPK–mTOR oscillator and the inner redox–epigenetic coupling via the SIRT1–PARP NAD

+ economy

. When negative feedback is intact, the loops remain anti-phased and resilient; under chronic drive, feedback polarity flips toward positive, leading to lock-in

. Top banner indicates Inputs (Training, Feeding, Hormones) and Outcomes (Oscillatory health - Lock-in), mapping boundary conditions and system state.

Together, the outer AMPK–mTOR and inner redox–epigenetic circuits form a closed-loop system in which metabolic sensing and chromatin remodeling are dynamically coupled.

Redox-Epigenetic Coupling and Systemic Instability - at the biochemical level, overdrive couples redox imbalance to epigenetic drift. Excess ROS oxidize 5-methylcytosine and histone residues, impairing TET- and Jumonji-mediated demethylation [

94]. NAD

+ depletion through PARP overactivation reduces SIRT-dependent chromatin silencing, compounding transcriptional noise. As feedback fidelity deteriorates, the epigenome begins to store the metabolic history of stress — a persistent “memory” of overload. Biomechanical asymmetry during repetitive effort may further amplify local metabolic load and redox stress, providing a physical correlate of systemic overdrive [

96]. Such molecular scars explain the lingering performance decrements and altered recovery profiles seen in chronically overtrained athletes [

97].

From Adaptation to Pathology - in its terminal form,

metabolic overdrive recapitulates the molecular hallmarks of tumorigenesis: constitutive mTOR signaling, defective autophagy, mitochondrial hyperpolarization, and aberrant methylation [

98]. Yet the model is not a statement of equivalence between athletic performance and cancer, but of shared architecture — both are systems pushed beyond adaptive elasticity. The lesson is systemic: human performance is limited not by energy supply, but by the capacity to restore homeostatic oscillation after each perturbation.

Implications - the Metabolic Overdrive Model redefines performance physiology as a dynamic equilibrium rather than a linear progression. It integrates nutrient sensing, redox homeostasis, and epigenetic regulation into one mechanistic continuum, uniting the biology of adaptation, aging, and disease. By identifying the molecular inflection point between beneficial stress and chronic overload, this framework offers a language to discuss both the promise and the peril of metabolic enhancement. In elite sport — and perhaps in life itself — resilience may depend less on how much energy we can generate than on how gracefully we can oscillate between expenditure and renewal.

To operationalize the Metabolic Overdrive Model, the key regulatory axes—nutritional, redox, and epigenetic—can be compared between adaptive and pathological configurations. This framework summarizes how oscillatory control across these domains sustains performance resilience, whereas persistent activation transforms feedback into self-reinforcing instability.

Table 5 presents a comparative synthesis of molecular, functional, and systemic features characterizing the transition from physiological adaptation to metabolic lock-in, integrating evidence from elite sport contexts.

Together, these patterns reveal that high performance and molecular fragility are separated not by intensity but by rhythm. When oscillatory checkpoints fail, systems designed for renewal become trapped in activation. The restoration of resilience, therefore, lies not in suppressing energy flux, but in reestablishing periodicity—the cellular capacity to alternate between catabolic repair and anabolic growth without losing feedback integrity.

2.6. Testable Predictions and Biomarkers

P1. Persistent anabolic drive flattens the AMPK–mTOR rhythm. After heavy training plus high nutrient/hormonal load, p-S6K1/4E-BP1 remain elevated >24 h while AMPK Thr172-P is depressed, indicating a shift toward sustained mTORC1 dominance and reduced autophagy. Readouts: AMPK Thr172-P, p-S6K1, p-4E-BP1, LC3-II, p62.

Rationale: Section 2.1 and

Section 2.5.

P2. Redox stress drives an NAD

+ sink and epigenetic drift. Overreaching under anabolic excess increases PARP activity (PARylation), lowers NAD

+ and SIRT1 activity, and biases chromatin toward ↑H3K9ac with ↓TET activity/5hmC. Readouts: NAD

+/NADH, PARylation, SIRT1 activity, H3K9ac, 5hmC.

Rationale: Section 2.3 and

Section 2.5.

P3. Periodic AMPK restoration re-establishes oscillation. Interventions that intermittently activate AMPK (e.g., fasted endurance, time-restricted feeding, polyphenol-driven AMPK activation) normalize NAD

+, reduce PARylation/ROS, and reverse acetylation/methylation drift. Readouts: AMPK Thr172-P, NAD

+, PARylation, H3K9ac, LC3-II.

Rationale: Section 2.1,

Section 2.3,

Section 2.5.

Measurement window: 24–48 h post-stimulus phase used to distinguish adaptive oscillation from lock-in dynamics. These hypotheses are non-causal claims but operational tests of the Metabolic Overdrive Model.

Operational biomarkers, preferred sampling windows and the strength of evidence supporting each axis are summarized in

Table 6.

This synthesis prioritizes operationalization over exhaustiveness. When feasible,

muscle biopsy allows direct quantification of AMPK Thr172-P and autophagy markers; otherwise,

PBMCs and plasma provide translational surrogates for

NAD+/NADH, PARylation, and circulating miRNAs. Arrows in

Table 6 denote the

expected deviation under metabolic overdrive, whereas the “Reversibility signal” column summarizes the direction of change when

oscillatory control is restored by AMPK-centric strategies (e.g., fasted endurance, time-restricted feeding, polyphenol-mediated AMPK activation). The

sampling windows (0–6 h; 24–72 h) are chosen to distinguish

transient adaptive oscillations from

pathological lock-in. Together with

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 and

Section 2.1,

Section 2.2,

Section 2.3,

Section 2.4 and

Section 2.5,

Table 6 anchors the Metabolic Overdrive Model in

measurable outcomes, closing the loop between mechanism and application. These operational choices define a biomarker panel and timing strategy that can be prospectively tested in elite athletes, informing periodization and health monitoring.

Pre-Analytical Considerations - translational application of the proposed biomarker panel requires strict pre-analytical control. NAD+, PARylation, and oxidative adducts are labile and sensitive to handling delays. PBMC isolation should occur within two hours of venipuncture in EDTA tubes kept on ice, followed by immediate centrifugation and quenching in methanol or −80 °C storage. Plasma redox assays (GSH/GSSG, TBARS) need rapid deproteinization to prevent artifactual oxidation. Whenever feasible, paired muscle biopsies remain the reference for AMPK Thr172-P and autophagic flux, but PBMCs are acceptable translational proxies if standardized processing is ensured. Inconsistent handling can mask oscillatory signatures and inflate inter-subject variability.

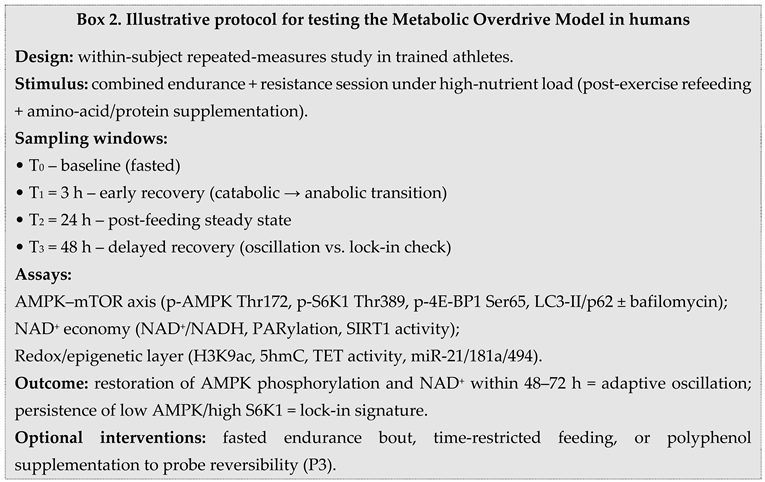

To illustrate how these biomarker axes can be empirically tested in human settings, an example protocol is outlined in Box 2.

3. Discussion

Elite sport represents the most concentrated form of physiological adaptation. Training, recovery, and nutrition interact through molecular pathways that sustain a delicate balance between energy demand and cellular renewal. This review integrated evidence from molecular physiology, redox biology, and epigenetic regulation to propose a unified view of exercise adaptation—the

Metabolic Overdrive Model. At its core, this model frames the oscillatory interplay between AMPK and mTOR as the molecular rhythm that governs energy homeostasis and cellular remodeling. When this rhythm is maintained, performance optimization and cellular resilience coexist; when it collapses, chronic anabolic signaling, oxidative imbalance, and epigenetic drift emerge as markers of metabolic saturation [

99].

Molecular Integration and Adaptive Oscillation - Exercise imposes alternating metabolic states—energy depletion followed by nutrient restoration—that naturally activate AMPK and mTOR in sequence. AMPK responds to energetic stress by promoting catabolic fluxes, mitochondrial biogenesis, and NAD

+ regeneration, while mTOR reactivates during recovery to stimulate protein synthesis and hypertrophy. This rhythmic succession underlies training adaptation: muscle repair, metabolic flexibility, and efficient redox management. Such periodicity prevents the accumulation of reactive oxygen species and preserves genomic stability through the coupling of energy and chromatin regulation [

100].

However, excessive training load, hypercaloric intake, or anabolic enhancement may flatten this oscillation. Constant nutrient abundance maintains mTORC1 activation, suppressing AMPK and silencing sirtuin signaling. The system enters a quasi-steady state of “metabolic overdrive,” in which feedback loops become feedforward, energy consumption continues without renewal, and oxidative stress amplifies [

101]. The same molecular mechanisms that drive adaptation under transient activation can, under persistent stimulation, erode the balance between synthesis and repair.

Redox–Epigenetic Coupling and Molecular Memory - Redox signaling provides a bridge between metabolic flux and long-term gene regulation. ROS generated during exercise act as transient messengers that activate AMPK, PGC-1α, and MAPK cascades—promoting antioxidant defense and mitochondrial turnover. When recovery is adequate, these signals resolve, leaving behind an adaptive chromatin imprint. Epigenetic mechanisms such as DNA demethylation at

PGC-1α,

TFAM, and

PDK4 loci or histone deacetylation via SIRT1 enhance oxidative capacity and metabolic resilience [

102].

In contrast, chronic anabolic activation alters this balance. Persistent nutrient supply increases acetyl-CoA and SAM availability, favoring histone hyperacetylation and DNA hypermethylation at antioxidant and catabolic genes while maintaining open chromatin at anabolic loci (

IGF1,

MYC,

mTOR). Combined with NAD

+ depletion through PARP overactivation, this state stabilizes transcriptional noise and accelerates epigenetic drift [

103]. These findings suggest that redox imbalance and methylation instability are not side effects of exercise overload but integral components of its molecular ceiling—the point where adaptability reaches saturation.

From Adaptive Drive to Overdrive - The boundaries of adaptation become most visible in elite contexts where metabolic pathways are chronically stressed. In endurance athletes, repeated hypoxic stimuli amplify HIF-1α signaling and erythropoietic drive, enhancing oxygen delivery but simultaneously elevating oxidative load. In strength and hypertrophy sports, sustained nutrient signaling and high protein or supplement intake reinforce mTOR dominance, suppressing autophagy and narrowing metabolic flexibility. Both scenarios reflect the duality of exercise as a molecular amplifier—capable of generating resilience or instability depending on rhythm and recovery [

104].

These parallels indicate that exercise, while fundamentally beneficial, shares with pathological systems the same feedback architecture: oscillatory when adaptive, rigid when overstimulated. Recognizing this continuum can help refine nutritional and training periodization strategies aimed at maintaining oscillatory fidelity—the biochemical equivalent of recovery capacity. Periodic activation of AMPK through endurance work, caloric modulation, or redox-based interventions (polyphenols, fasting, mitochondrial uncouplers) may restore flexibility and counteract chronic mTOR saturation [

105].

Integrative Implications and Conceptual Outlook - The

Metabolic Overdrive Model thus provides a mechanistic language to describe how exercise-induced molecular rhythms sustain or lose coherence under stress. It reconciles findings from performance physiology, sports nutrition [

106], and redox biology, showing that metabolic resilience depends less on the magnitude of energy flux than on the precision of feedback control. In practice, maintaining rhythmic transitions between activation and renewal—training and recovery, feeding and fasting—may be the most fundamental determinant of long-term performance stability [

107].

Beyond sport, the same logic applies to broader contexts of human adaptation: aging, metabolic disease, and tissue regeneration all depend on the fidelity of oscillatory control. Exercise serves here as both model and metaphor—a living system that teaches how biological renewal is sustained through periodic imbalance.

Limitations and Future Directions - While this review offers a mechanistic synthesis grounded in established molecular principles, it remains a conceptual construct requiring empirical validation. Most data supporting the oscillatory model derive from indirect or cross-sectional evidence. Future studies should employ longitudinal multi-omics approaches—integrating transcriptomic, metabolomic, and methylomic time-series—to track molecular cycles of AMPK–mTOR activation, NAD+ flux, and redox oscillation during structured training interventions. Computational modeling could further identify energetic thresholds or “bifurcation points” marking the transition from adaptive to maladaptive states.

Elite performance provides an ideal setting for this inquiry. The same interventions used to maximize adaptation—nutritional periodization, recovery modulation, and exercise dosing—can serve as experimental tools for testing system stability. Integrating molecular assays with performance metrics may reveal biomarkers of oscillatory health, guiding safer performance enhancement and long-term metabolic preservation.

4. Materials and Methods - Mechanistic Evidence Mapping and Causal-Loop Synthesis (Non-Systematic)

Aim and review type - We sought to construct a working mechanistic model explaining how sustained nutrient/hormonal drive can flatten the AMPK–mTOR oscillation and couple redox imbalance to epigenetic drift, and to translate this into assayable human biomarkers. This is a mechanistic synthesis (narrative, non-systematic); no meta-analysis or risk-of-bias scoring was attempted.

Conceptual frame - Evidence items were treated as nodes (AMPK, mTORC1, SIRT1, PARP1, NAD+/NADH, ROS, H3K9ac, 5mC/5hmC, miRNAs) and edges (activation/inhibition, cofactor dependence, feedback polarity) across three pre-specified axes: nutritional signaling (AMPK–mTOR), NAD+ economy (SIRT1–PARP/redox), and chromatin regulation (DNMT/TET, HAT/HDAC, miRNAs).

Eligibility criteria (mechanistic) - Include: studies with directionality/cofactor coupling (e.g., AMPK Thr172-P; p-S6K1/4E-BP1; PARylation with NAD+/SIRT1; H3K9ac; 5mC/5hmC; TET activity; miRNA shifts), clear upstream–downstream logic, or explicit feedback relevant to exercise/nutrition/doping; Exclude: purely descriptive associations; single-time-point phenomenology without temporal context; off-axis pathways; non-primary commentaries. Preference for human acute/training-block data and human-assayable readouts (PBMCs/plasma/muscle).

Literature provenance (seed corpus and expansion) - We initiated mapping from sentinel papers already cited in the manuscript (AMPK/mTOR core, NAD+/PARP–sirtuin crosstalk, exercise-epigenetics) and expanded by backward/forward citation chasing and topic adjacency across the three axes. No pre-registered search was used; the synthesis prioritizes mechanistic coherence over exhaustiveness.

Screening and selection (two-pass, consensus) - Titles/abstracts and then full texts were independently screened by both authors against §4.3; disagreements were resolved by consensus with logged exclusion reasons (insufficient mechanistic readouts; off-axis; non-primary). This two-pass approach limits selection drift while avoiding PRISMA-style apparatus, which is not appropriate for cross-domain mechanistic integration.

Data extraction (fields and timing) - For each item we recorded: model/specimen; intervention and timing; directional readouts (e.g., ↑p-S6K1 with ↓AMPK Thr172-P; ↑PARylation with ↓NAD+/SIRT1); cofactor status (NAD+, acetyl-CoA, SAM, α-KG where available); epigenetic marks (H3K9ac; DNMT1; TET/5hmC; locus-specific methylation at PGC-1α, TFAM, PDK4); and human-assayable proxies (PBMC/plasma miRNAs, oxidative adducts).

Mechanistic quality and consistency appraisal (non-scored) - Heuristics emphasized internal validity of mechanisms rather than effect sizes:

(1) Orthogonal concordance (e.g., p-S6K1 and 4E-BP1 for mTORC1; PARylation with NAD+ drawdown and SIRT1 suppression).

(2) Temporality (0–6 h vs 24–72 h windows to separate oscillation from lock-in).

(3) Dose/context response (nutrient load, anabolic agents, hypoxia/EPO).

(4) Cross-species triangulation privileging human alignment. Conflicts (e.g., ROS hormesis vs damage) were resolved by context splitting (acute vs sustained anabolic load).

Synthesis and predefined outputs - Edges were graded strong/moderate/limited by readout concordance, temporality, and human support. We then condensed relations into five operational domains (AMPK–mTOR balance; NAD+ economy; redox status; epigenetic layer; mitochondrial quality/miRNAs), yielding the biomarker panel and sampling windows in Table 6 and the testable predictions.

Limitations - Selection bias toward studies with rich mechanistic readouts; scarcity of longitudinal multi-omics in elite cohorts; potential publication bias favoring positive signaling results; limited availability of human biopsies at the exact windows that separate oscillation from lock-in. These constraints are acknowledged in Discussion and motivate the prospective biomarker agenda (

Table 6).

5. Conclusions

Human performance emerges from a dynamic equilibrium between energy generation and molecular repair. The Metabolic Overdrive Model proposed here reframes this equilibrium as an oscillatory dialogue between nutrient sensing, redox regulation, and epigenetic plasticity. Within this loop, AMPK and mTOR act not as antagonists but as temporal partners, orchestrating periodic cycles of depletion and renewal that sustain adaptation. When this rhythm collapses—through nutritional excess, pharmacologic stimulation, or chronic overload—the system enters metabolic overdrive: an energetically amplified but informationally unstable state.

This framework unites the physiology of performance with the biology of instability. The same molecular circuits that enable hypertrophy, angiogenesis, and resilience under stress can, when persistently activated, erode redox homeostasis, silence autophagy, and imprint maladaptive epigenetic marks. The border between adaptation and pathology is therefore not structural but rhythmic — defined by whether the organism can restore oscillation after each pulse of stress.

Understanding performance through this lens moves the field beyond simple narratives of training load or nutrient intake toward a systems view of resilience. It invites a future in which athlete health is monitored not only through hormonal or metabolic markers but also through signatures of epigenetic flexibility and redox rhythm. Protecting the capacity to oscillate — to alternate between anabolism and repair — may prove to be the true foundation of both longevity and excellence.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.C.M. and A.M.M.; methodology, D.C.M. and A.M.M.; software, D.C.M. and A.M.M.; validation, D.C.M. and A.M.M.; formal analysis, D.C.M. and A.M.M.; investigation, D.C.M. and A.M.M.; resources, D.C.M. and A.M.M.; data curation, D.C.M. and A.M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, D.C.M. and A.M.M.; writing—review and editing, D.C.M. and A.M.M.; visualization, D.C.M. and A.M.M.; supervision, D.C.M. and A.M.M.; project administration, D.C.M. and A.M.M.; funding acquisition, D.C.M. and A.M.M. All authors have equal contribution. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

This research received no external funding

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are included within the article. Additional information or analytical materials are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

AMPK – AMP-activated protein kinase

mTORC1/2 – mechanistic target of rapamycin complex ½

SIRT1 – NAD+-dependent deacetylase

PARP – Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase

NAD+ – nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

UPR – unfolded protein response

ROS – reactive oxygen species

DNMT – DNA methyltransferase

TET – ten–eleven translocation enzyme

HAT – histone acetyltransferase

HDAC – histone deacetylase

miRNA – microRNA

PBMC – peripheral blood mononuclear cell

References

- González, A.; Hall, M.N.; Lin, S.C.; Hardie, D.G. AMPK and TOR: The Yin and Yang of Cellular Nutrient Sensing and Growth Control. Cell Metab. 2020, 31, 472–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, C.G.R.; Hawley, J.A. Molecular Basis of Exercise-Induced Skeletal Muscle Mitochondrial Biogenesis: Historical Advances, Current Knowledge, and Future Challenges. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2018, 8, a029686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxton, R.A.; Sabatini, D.M. mTOR signaling in growth, metabolism, and disease. Cell 2017, 169, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esteves, J.V.; Stanford, K.I. Exercise as a tool to mitigate metabolic disease. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2024, 327, C587–C598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camera, D.M.; Smiles, W.J.; Hawley, J.A. Exercise-induced skeletal muscle signaling pathways and the regulation of metabolism. Biochem. J. 2016, 473, 2319–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentch, S.J.; Locasale, J.W. One-carbon metabolism and epigenetics: Understanding the specificity of the methyl donor pathway. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016, 17, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaborne, R.A.; Strauss, J.; Cocks, M.; Shepherd, S.O.; O’Brien, T.D.; van Someren, K.A.; Bell, P.G.; Murgatroyd, C.; Morton, J.P.; Stewart, C.E. Human Skeletal Muscle Possesses an Epigenetic Memory of Hypertrophy. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barres, R.; Zierath, J.R. The role of diet and exercise in the transgenerational epigenetic landscape of T2DM. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2016, 12, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihaylova, M.M.; Shaw, R.J. The AMPK signaling pathway coordinates cell growth, autophagy, and metabolism. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011, 13, 1016–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharples, A.P. Skeletal Muscle Possesses an Epigenetic Memory of Exercise: Role of Nucleus Type-Specific DNA Methylation. Function (Oxf.) 2021, 2, zqab047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Redondo-Flórez, L.; Ruisoto, P.; Navarro-Jiménez, E.; Ramos-Campo, D.J.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. Metabolic Health, Mitochondrial Fitness, Physical Activity, and Cancer. Cancers 2023, 15, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, R.W.; McGlory, C.; Phillips, S.M. Nutritional interventions to augment resistance training-induced skeletal muscle hypertrophy. Front. Physiol. 2015, 6, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powers, S.K.; Deminice, R.; Ozdemir, M.; Yoshihara, T.; Bomkamp, M.P.; Hyatt, H. Exercise-induced oxidative stress: Friend or foe? J. Sport Health Sci. 2020, 9, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herzig, S.; Shaw, R.J. AMPK: Guardian of Metabolism and Mitochondrial Homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karasawa, T.; Choi, R.H.; Meza, C.A.; Maschek, J.A.; Cox, J.E.; Funai, K. Skeletal muscle PGC-1α remodels mitochondrial phospholipidome but does not alter energy efficiency for ATP synthesis. bioRxiv 2024, 2024.05.22.595374. [CrossRef]

- Goul, C.; Peruzzo, R.; Zoncu, R. The molecular basis of nutrient sensing and signalling by mTORC1 in metabolism regulation and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2023, 24, 857–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Lopez, N.; Mattar, P.; Toledo, M.; Aoun, M.L.; Sharma, M.; McIntire, L.B.; Gunther-Cummins, L.; Macaluso, F.P.; Aguilan, J.T.; Sidoli, S.; et al. mTORC2–NDRG1–CDC42 axis couples fasting to mitochondrial fission. Nat. Cell Biol. 2023, 25, 989–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, J.R.; Blaschke, S.; et al. Exercise increases phosphorylation of the putative mTORC2 activity marker NDRG1 Thr346 in human skeletal muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 322, E465–E475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, C.; Song, Y.; Wang, Y.; Bo, H.; Zhang, Y. Impact of Exercise and Aging on Mitochondrial Homeostasis in Skeletal Muscle: Roles of ROS and Epigenetics. Cells 2022, 11, 2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaguri, A.; Nahar, P.; Srinivasan, S.; et al. Exercise Metabolome: Insights for Health and Performance. Metabolites 2023, 13, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwalm, C.; Jamart, C.; Benoit, N.; Naslain, D.; Premont, C.; Prevet, J.; Van Thienen, R.; Deldicque, L.; Francaux, M. Activation of Autophagy in Human Skeletal Muscle Is Dependent on Exercise Intensity and AMPK Activation. FASEB J. 2015, 29, 3515–3526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouchiroud, L.; et al. The NAD+/Sirtuin pathway modulates longevity through mitochondrial UPR. Cell 2013, 154, 430–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, S.K.; Morton, A.B.; Ahn, B.; Smuder, A.J. Redox control of skeletal muscle atrophy. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016, 98, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanti, M.; Longo, V.D. Nutrition, GH/IGF-1 Signaling, and Cancer. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2024, 31, e230048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jewell, J.L.; Kim, Y.C.; Russell, R.C.; Yu, F.X.; Park, H.W.; Plouffe, S.W.; Tagliabracci, V.S.; Guan, K.L. Metabolism. Differential regulation of mTORC1 by leucine and glutamine. Science 2015, 347, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zubrzycki, I.Z.; Ossowski, Z.; Przybylski, S.; Wiacek, M.; Clarke, A.; Trąbka, B. Supplementation with Silk Amino Acids Improves Physiological Parameters Defining Stamina in Elite Fin-Swimmers. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2014, 11, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Courneya, K.S.; Friedenreich, C.M. The Physical Activity and Cancer Control (PACC) framework: Update on the evidence, guidelines, and future research priorities. Br. J. Cancer 2024, 131, 957–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, K.T.; Noake, C.; Wolff, R.; Bauld, L.; Espina, C.; Foucaud, J.; Steindorf, K.; Thorat, M.A.; Weijenberg, M.P.; Schüz, J.; Kleijnen, J. Digital interventions to moderate physical inactivity and/or nutrition in young people: A Cancer Prevention Europe overview of systematic reviews. Front. Digit. Health 2023, 5, 1185586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantó, C.; Menzies, K.J.; Auwerx, J. NAD(+) Metabolism and the Control of Energy Homeostasis: A Balancing Act between Mitochondria and the Nucleus. Cell Metab. 2015, 22, 31–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, V.D.; Panda, S. Fasting, circadian rhythms, and time-restricted feeding in healthy lifespan. Cell Metab. 2016, 23, 1048–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, M.; Spriet, L.L. Skeletal Muscle Energy Metabolism during Exercise. Nat. Metab. 2020, 2, 817–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirago, G.; Maggi, L.; et al. Mammalian Target of Rapamycin (mTOR) Signaling at the Crossroad of Multicellular Muscle Adaptation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Wei, Y.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, S.; Ma, N.; Wang, K.; Tan, P.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, J.; Ma, X. Arginine Regulates Skeletal Muscle Fiber Type Formation via mTOR Signaling Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Wu, G. Targeting mTOR for Anti-Aging and Anti-Cancer Therapy. Molecules 2023, 28, 3157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fingar, D.C.; Blenis, J. Target of rapamycin (TOR): An integrator of nutrient and growth factor signals and coordinator of cell growth and cell cycle progression. Oncogene 2024, 23, 3151–3171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mănescu, D.C. Computational Analysis of Neuromuscular Adaptations to Strength and Plyometric Training: An Integrated Modeling Study. Sports 2025, 13, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemmons, D.R. Metabolic actions of insulin-like growth factor-I in normal physiology and diabetes. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 2012, 41, 425–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galifi, C.A.; Colalillo, S.; Bertuzzi, A.; Bianchini, M.; Silletti, S. Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 Receptor Crosstalk with Integrins in Cancer Progression. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2023, 30, ERC–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.; Bergholz, J.; Zhang, H.; He, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Q.; Kirkland, J.L.; Xiao, Z.; Wang, C.; et al. Insulin-like growth factor-1 regulates the SIRT1–p53 pathway in cellular senescence. Aging Cell 2014, 13, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Yan, Z. Molecular Mechanisms of Exercise and Healthspan. Cells 2022, 11, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacko, D.; Schaaf, K.; Masur, L.; Windoffer, H.; Aussieker, T.; Schiffer, T.; Zacher, J.; Bloch, W.; Gehlert, S. Repeated and Interrupted Resistance Exercise Induces the Desensitization and Re-Sensitization of mTOR-Related Signaling in Human Skeletal Muscle Fibers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciejczyk, M.; Palka, T.; Wiecek, M.; Masel, S.; Szygula, Z. The Effects of Intermittent Hypoxic Training on Anaerobic Performance in Young Men. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.S.; Lee, C.; Kim, S.; et al. Baf155 Regulates Skeletal Muscle Metabolism via HIF-1α Signalling. PLoS Biol. 2023, 21, e3002192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, W.; Noguchi, C.T. The Role of Erythropoietin in Metabolic Regulation. Cells 2025, 14, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Man, M.C.; Ganera, C.; Bărbuleţ, G.D.; Krzysztofik, M.; Panaet, A.E.; Cucui, A.I.; Tohănean, D.I.; Alexe, D.I. The Modifications of Haemoglobin, Erythropoietin Values and Running Performance While Training at Mountain vs. Hilltop vs. Seaside. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Chen, C.; Teo, E.-C.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, J.; Xu, Y.; Gu, Y. Intracellular Oxidative Stress Induced by Physical Exercise in Adults: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Su, C-H. The Impact of Physical Exercise on Oxidative and Nitrosative Stress: Balancing the Benefits and Risks. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabharwal, S.S.; Schumacker, P.T. Mitochondrial ROS in cancer: Initiators, amplifiers or an Achilles' heel? Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 709–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, L.B.; Chandel, N.S. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and cancer. Cancer Metab. 2014, 2, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, I.; Carrillo-Bosch, L.; Seoane, J. Targeting the Warburg Effect in Cancer: Where Do We Stand? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddocks, O.D.K.; Labuschagne, C.F.; Adams, P.D.; Vousden, K.H. Serine metabolism supports the methionine cycle and DNA/RNA methylation through de novo ATP synthesis in cancer cells. Mol. Cell 2016, 61, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chauhan, A.; Dai, Y. Connections between metabolism and epigenetics: From basic mechanisms to clinical implications. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2022, 13, 935536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pouikli, A.; Tessarz, P. Metabolism and chromatin: A dynamic duo that regulates development and ageing. BioEssays 2021, 43, e2000273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, N.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Dong, Y. NAD+ metabolism: Pathophysiologic mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2020, 5, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mentch, S.J.; Locasale, J.W. One-carbon metabolism and epigenetics: Understanding the specificity of the methyl donor pathway. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016, 17, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janke, R.; Dodson, A.E.; Rine, J. Metabolism and epigenetics. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2015, 31, 473–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrès, R.; Yan, J.; Egan, B.; Treebak, J.T.; Rasmussen, M.; Fritz, T.; Caidahl, K.; Krook, A.; O’Gorman, D.J.; Zierath, J.R. Acute exercise remodels promoter methylation in human skeletal muscle. Cell Metab. 2012, 15, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, G.R.; Kemp, B.E. AMPK in health and disease. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 89, 1025–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaborne, R.A.; Strauss, J.; Cocks, M.; Shepherd, S.O.; O’Brien, T.D.; van Someren, K.A.; Bell, P.G.; Murgatroyd, C.; Morton, J.P.; Stewart, C.E. Human skeletal muscle possesses an epigenetic memory of hypertrophy. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrès, R.; Zierath, J.R. The role of diet and exercise in the transgenerational epigenetic landscape of T2DM. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2016, 12, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Costello, J. DNA methylation: An epigenetic mark of cellular memory. Exp. Mol. Med. 2017, 49, e322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baylin, S.B.; Jones, P.A. A decade of exploring the cancer epigenome—Biological and translational implications. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2011, 11, 726–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shvedunova, M.; Akhtar, A. Modulation of cellular processes by histone and non-histone lysine acetylation: Mechanisms, targets, and physiological significance. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 304–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantó, C.; Sauve, A.A.; Bai, P. Crosstalk between poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase and sirtuin enzymes. Mol. Aspects Med. 2013, 34, 1168–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afzal, M.; Greco, F.; Quinzi, F.; Scionti, F.; Maurotti, S.; Montalcini, T.; Mancini, A.; Buono, P.; Emerenziani, G.P. The Effect of Physical Activity/Exercise on miRNA Expression and Function in Non-Communicable Diseases—A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grieb, A.; Schmitt, A.; Fragasso, A.; Widmann, M.; Mattioni Maturana, F.; Burgstahler, C.; Erz, G.; Schellhorn, P.; Nieß, A.M.; Munz, B. Skeletal Muscle MicroRNA Patterns in Response to a Single Bout of Exercise in Females: Biomarkers for Subsequent Training Adaptation? Biomolecules 2023, 13, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintanilha, B.J.; Reis, B.Z.; Duarte, G.B.S.; Cozzolino, S.M.F.; Rogero, M.M. Nutrimiromics: Role of microRNAs and nutrition in modulating inflammation and chronic diseases. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radom-Aizik, S.; et al. Effects of exercise training on microRNA expression in young and older men. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 29, 831–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X. MicroRNA-34 Family in Cancers: Role, Mechanism, and Therapeutic Potential. Cancers 2023, 15, 4723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M.; Yang, H.; Xu, W.; Ma, S.; Lin, H.; Zhu, H.; Liu, L.; Liu, Y.; Yang, C.; Xu, Y.; et al. Inhibition of α-KG–dependent histone and DNA demethylases by fumarate and succinate that are accumulated in mutations of FH and SDH tumor suppressors. Genes Dev. 2012, 26, 1326–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walzik, D.; Jonas, W.; Joisten, N.; Belen, S.; Wüst, R.C.I.; Guillemin, G.; Zimmer, P. Tissue-Specific Effects of Exercise as NAD+-Boosting Strategy: Current Knowledge and Future Perspectives. Acta Physiol. 2023, 237, e13921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, S.; Raj, K. DNA methylation-based biomarkers and the epigenetic clock theory of ageing. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2018, 19, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mănescu, D.C.; Mănescu, A.M. Artificial Intelligence in the Selection of Top-Performing Athletes for Team Sports: A Proof-of-Concept Predictive Modeling Study. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mănescu, D.C. Big Data Analytics Framework for Decision-Making in Sports Performance Optimization. Data 2025, 10, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeusen, R.; Duclos, M.; Foster, C.; Fry, A.; Gleeson, M.; Nieman, D.; Raglin, J.; Rietjens, G.; Steinacker, J.; Urhausen, A. Prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of the overtraining syndrome. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2013, 13, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Lázaro, D.; Mielgo-Ayuso, J.; Caballero-García, A.; Calleja-González, J.; Herrador-Pérez, M.; Armegod-Benítez, M.; Crespo-Otín, S.; Carratalá-Tejada, R. Adequacy of an Altitude Fitness Program (Living and Training at Moderate Altitude) Supplemented with Intermittent Hypoxic Training: Effects on Sports Performance, Blood Biomarkers and Safety Profiles in Elite Athletes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maciejczyk, M.; Palka, T.; Wiecek, M.; Szymura, J.; Kusmierczyk, J.; Bawelski, M.; Masel, S.; Szygula, Z. Effects of Intermittent Hypoxic Training on Aerobic Capacity and Second Ventilatory Threshold in Untrained Men. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goliniewski, J.; Czuba, M.; Płoszczyca, K.; Chalimoniuk, M.; Gajda, R.; Niemaszyk, A.; Kaczmarczyk, K.; Langfort, J. The Impact of Normobaric Hypoxia and Intermittent Hypoxic Training on Cardiac Biomarkers in Endurance Athletes: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, A.B.; Bejder, J.; Bonne, T.C.; Nordsborg, N.B. Contemporary Blood Doping—Performance, Mechanism, and Detection. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2024, 34, e14243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordeuk, V.R.; Key, N.S.; Prchal, J.T. Re-Evaluation of Hematocrit as a Determinant of Thrombotic Risk in Erythrocytosis. Haematologica 2019, 104, 653–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Han, F.; Du, Y.; Shi, H.; Zhou, W. Hypoxic Microenvironment in Cancer: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Interventions. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuoka, Y.; Izumi, Y.; Sands, J.M.; Kawahara, K.; Nonoguchi, H. Progress in the Detection of Erythropoietin in Blood, Urine, and Tissue. Molecules 2023, 28, 4446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagel, M.J.; Jarrard, C.P.; Lalande, S. Effect of a Single Session of Intermittent Hypoxia on Erythropoietin and Oxygen-Carrying Capacity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manescu, D.C. Alimentaţia în fitness şi bodybuilding. 2010, Editura AS.

- Hurst, P.; Kavussanu, M.; Davies, R.; Dallaway, N.; Ring, C. Use of Sport Supplements and Doping Substances by Athletes: Prevalence and Relationships. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J. ; The mechanisms of anabolic steroids, selective androgen receptor modulators and resistance exercise in skeletal muscle hypertrophy. Korean J. Sports Med. 2022, 40, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waskiw-Ford, M.; Hodson, N.; Fung, H.J.W.; West, D.W.D.; Apong, P.; Bashir, R.; Moore, D.R. Essential Amino Acid Ingestion Facilitates Leucine Retention and Attenuates Myofibrillar Protein Breakdown following Bodyweight Resistance Exercise in Young Adults in a Home-Based Setting. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivalokanathan, S.; Małek, Ł.A.; Malhotra, A. The Cardiac Effects of Performance-Enhancing Medications: Caffeine vs. Anabolic Androgenic Steroids. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, J.L.; Rasmussen, J.J.; Frandsen, M.N.; Fredberg, J.; Brandt-Jacobsen, N.H.; Aagaard, P.; Kistorp, C. Higher Myonuclei Density in Muscle Fibers Persists Among Former Users of Anabolic Androgenic Steroids. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2024, 109. [CrossRef]

- Herlitz, L.C.; Markowitz, G.S.; Farris, A.B. ; Development of Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis after Anabolic Steroid Abuse. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010, 21, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, B.P.; Kanayama, G.; Hudson, J.I.; Pope, H.G. Jr. Human Growth Hormone Abuse in Male Weightlifters. Am. J. Addict. 2011, 20, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshino, D.; Yoshida, Y.; Holloway, G.P.; Lally, J.; Hatta, H.; Bonen, A. Clenbuterol, a β2-Adrenergic Agonist, Reciprocally Alters PGC-1α and RIP140 and Reduces Fatty Acid and Pyruvate Oxidation in Rat Skeletal Muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2012, 302, R373–R384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiacek, M.; Trąbka, B.; Tomasiuk, R.; Zubrzycki, I.Z. Changes in Health-Related Parameters Associated with Sports Performance Enhancement Drugs. Int. J. Sports Med. 2023, 44, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Gerche, A.; Wasfy, M.M.; Brosnan, M.J.; Claessen, G.; Fatkin, D.; Heidbüchel, H.; Thompson, P.D. The Athlete’s Heart—Challenges and Controversies. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022, 80, 1346–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mănescu, A.M.; Grigoroiu, C.; Smîdu, N.; Dinciu, C.C.; Mărgărit, I.R.; Iacobini, A.; Mănescu, D.C. Biomechanical Effects of Lower Limb Asymmetry During Running: An OpenSim Computational Study. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furrer, R.; Handschin, C. Molecular Aspects of the Exercise Response and Training Adaptation in Skeletal Muscle. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 223, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zubrzycki, I.Z.; Wiacek, M.; Trąbka, B.; Ossowski, Z. Anabolic Steroids in a Contest Preparation of the Top World-Class Bodybuilder. Int. J. Med. Pharm. Case Rep. 2015, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza-Díaz, J.; Izquierdo, D.; Torres-Martos, Á.; Baig, A.T.; Aguilera, C.M.; Ruiz-Ojeda, F.J. Impact of Physical Activity and Exercise on the Epigenome in Skeletal Muscle and Effects on Systemic Metabolism. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Bustamante-Sánchez, Á.; Mielgo-Ayuso, J.; Martínez-Guardado, I.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. Antioxidants and Sports Performance. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, H.; Liu, Q.; Xu, W.; Chen, X. Impact of Exercise and Aging on Mitochondrial Function via Epigenetic Modifications. Cells 2022, 11, 2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.; Wadsworth, D.D.; Geetha, T. Exercise, Epigenetics, and Body Composition: Molecular Connections. Cells 2025, 14, 1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Centner, C.; Gollhofer, A.; König, D. Effects of Dietary Strategies on Exercise-Induced Oxidative Stress: A Narrative Review of Human Studies. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolodziej, F.; O’Halloran, K.D. Re-Evaluating the Oxidative Phenotype: Can Endurance Exercise Save the Western World? Antioxidants 2021, 10, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Villanueva M, Kramer A, Hammes T, Venegas-Carro M, Thumm P, Bürkle A, Gruber, M. Influence of Acute Exercise on DNA Repair and PARP Activity before and after Irradiation in Lymphocytes from Trained and Untrained Individuals. Int J Mol Sci. 2019, 20, 2999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasemi, M.; Jolicoeur, M. Modelling Cell Metabolism: A Review on Constraint-Based Steady-State and Kinetic Approaches. Processes 2021, 9, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manescu, D.C. Nutritional tips for muscular mass hypertrophy. Marathon 2016, 8, 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Volkova, S.; Matos, M.R.A.; Mattanovich, M.; Marín de Mas, I. Metabolic Modelling as a Framework for Metabolomics Data Integration and Analysis. Metabolites 2020, 10, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |