Submitted:

20 October 2025

Posted:

21 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures and Instrumentation

Questionnaire Development and Pre-Testing

Questionnaire

Data Collection Procedure

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Analysis

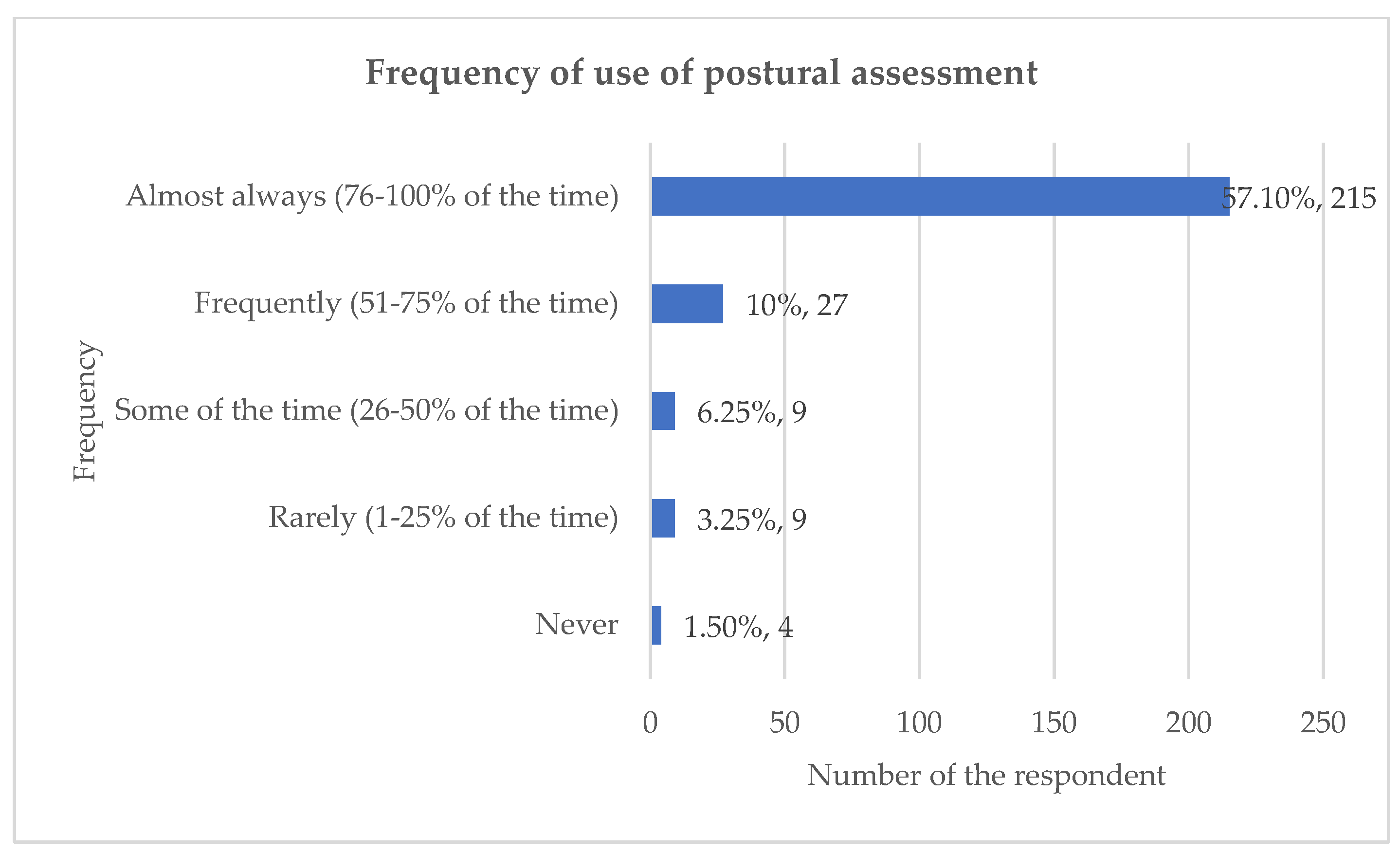

3.1.1. The Frequency of Use of Postural Assessment

3.1.2. Rationale for the Use of Postural Assessment

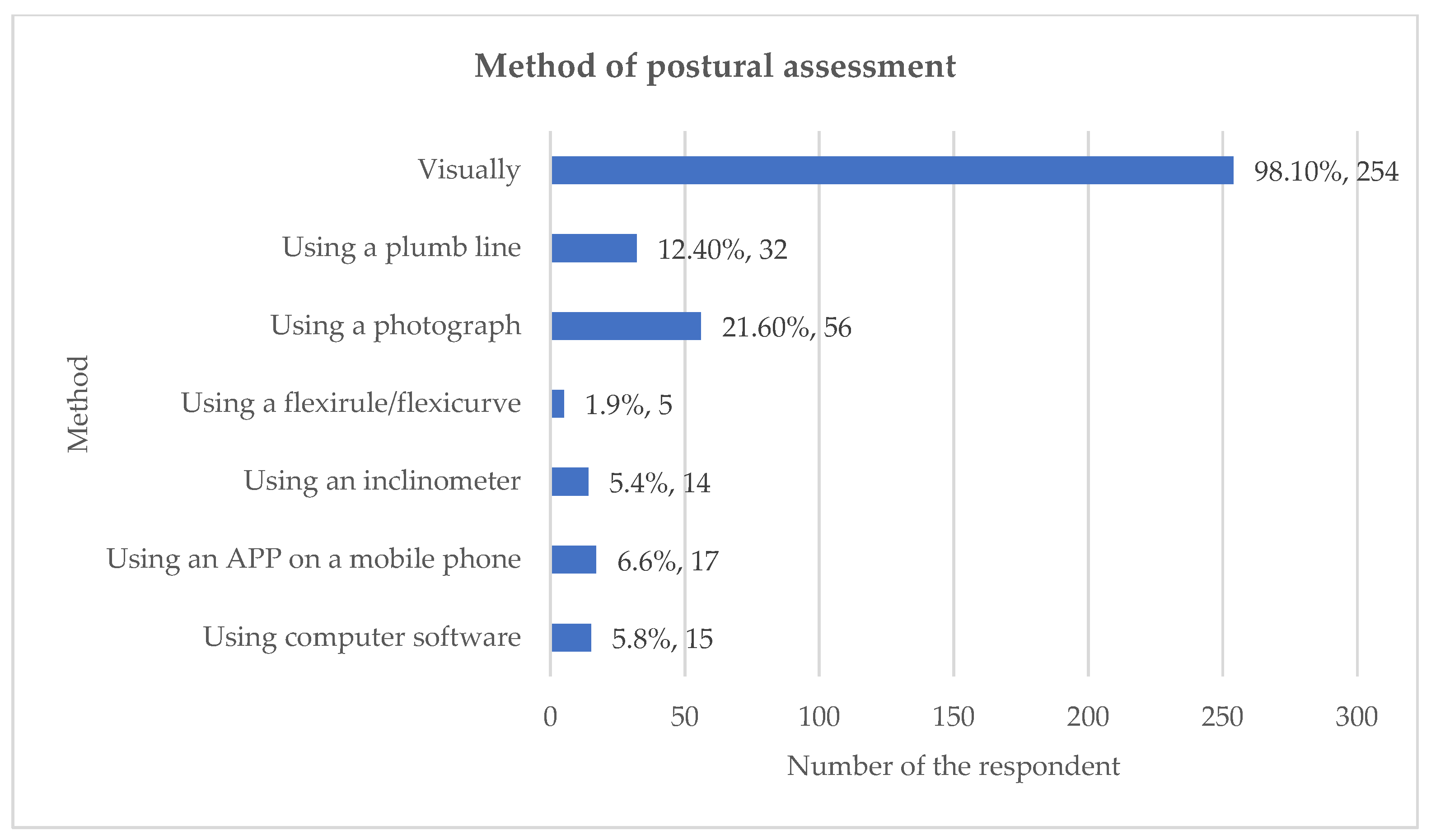

3.1.3. Method of Assessing Posture

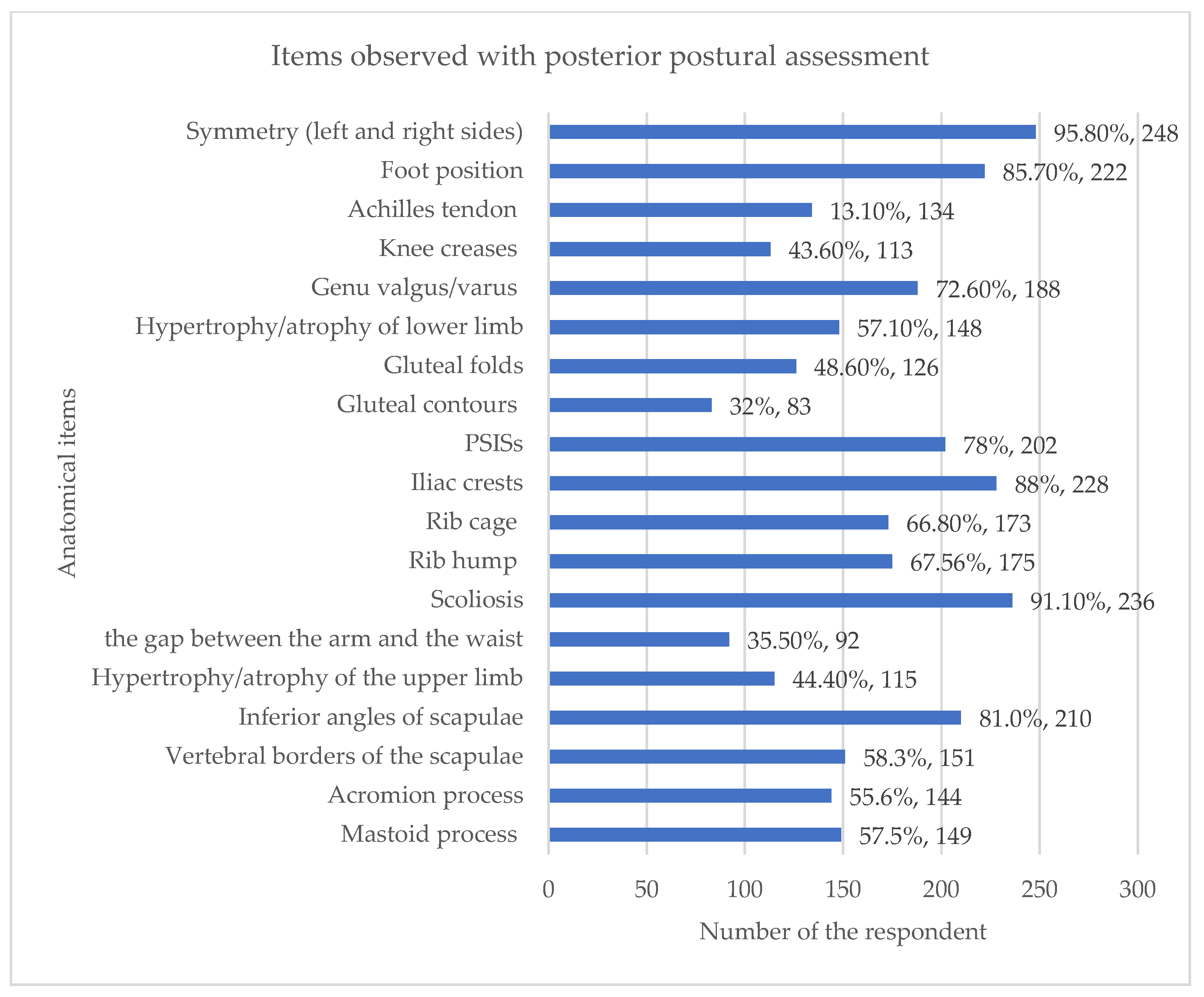

3.1.4. Specific Postural Assessment Indices

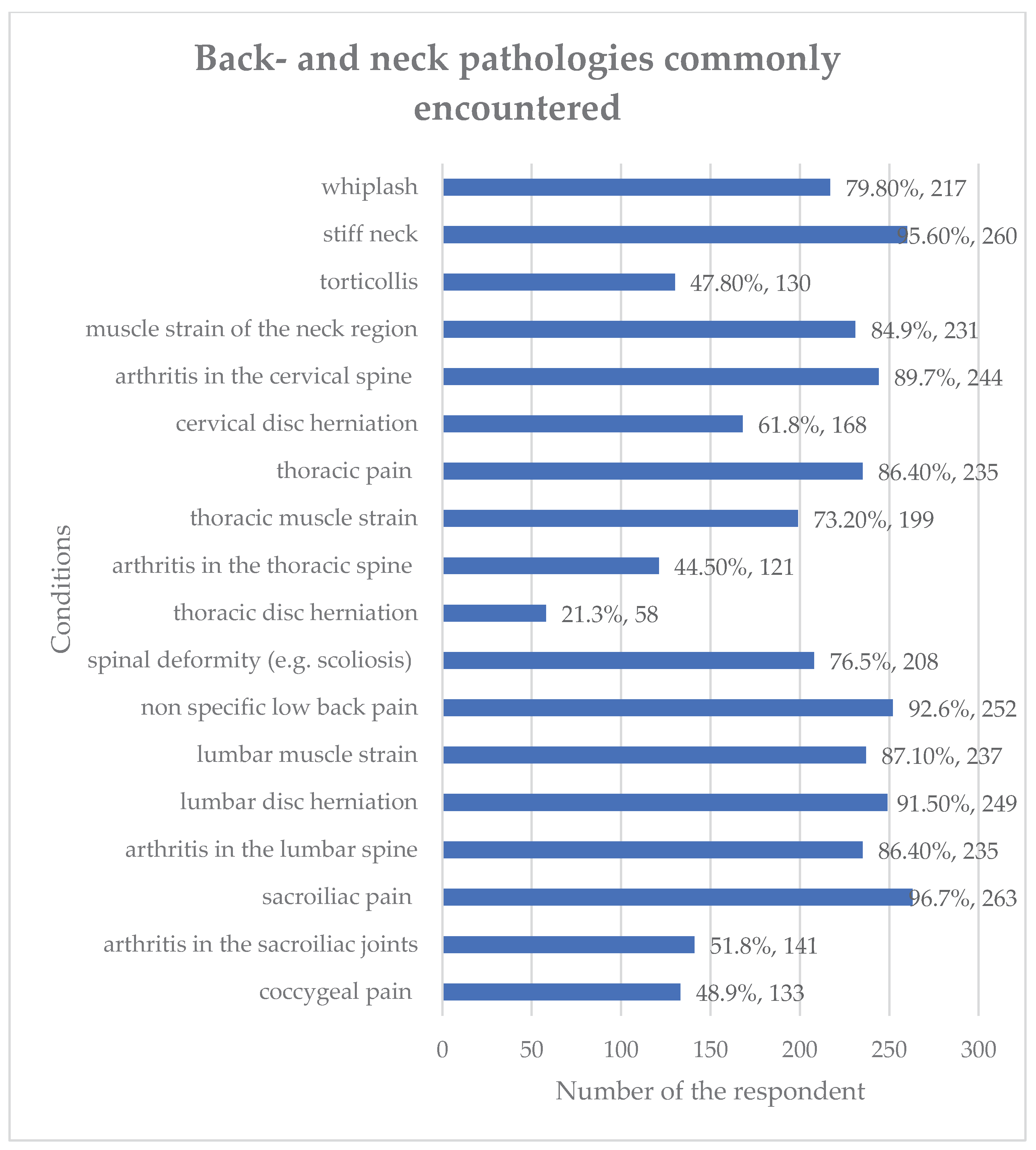

3.1.5. Back and Neck Pathologies Encountered by Chiropractors

3.2. Qualitative Analysis

3.2.1. Rationale for the Use for Postural Assessment

3.2.2. Methods Used to Carry Out Postural Assessment

3.2.3. Positions Used for Postural Assessment

3.2.4. Back- and Neck Pathologies Encountered in Clinical Practice

3.2.5. Additional Comments

4. Discussion

Key Findings

Quantitative and Qualitative Data

Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (2005) WHO Guidelines on basic training and safety in chiropractic. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available at: https://www.who.int/medicines/areas/traditional/Chiro-Guidelines.pdf (Accessed: 29 Jun 2016).

- General Chiropractic Council (2010b) Your first visit? Available at: https://www.gcc- uk.org/chiropractic-standards/seeing-a-chiropractor-for-the-first-time (Accessed: ). 1 July.

- Kendall, F.P.; McCreary, E.K.; Provance, P.G.; Rodgers, M.M.; Romani, W.A. Muscles: Testing and Function, with Posture and Pain, 5th ed.; LWW: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-0-7817-4780-6. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J. (2012) Postural assessment. Champaign: Human Kinetics. Author 1, A.; Author 2, B. Book Title, 3rd ed.; Publisher: Publisher Location, Country, 2008; pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar]

- Magee, D. J. (2002) Orthopedic physical assessment. Philadelphia, US: Saunders.

- Page, P. , Frank, C.C. and Lardner, R. (2010) Assessment and treatment of muscle imbalance: the Janda approach. Champaign, US: Human Kinetics.

- Hartvigsen, J.; French, S. What is chiropractic? Chiropr. Man. Ther. 2017, 25, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederman, E. The fall of the postural-structural-biomechanical model in manual and physical therapies: Exemplified by lower back pain. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2011, 15, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enwemeka, C.S.; Bonet, I.M.; Ingle, J.A.; Prudhithumrong, S.; Ogbahon, F.E.; Gbenedio, N.A. Postural Correction in Persons with Neck Pain. I. A Survey of Neck Positions Recommended by Physical Therapists. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 1986, 8, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorak, C.; Ashworth, N.; Marshall, J.; Paull, H. Reliability of the Visual Assessment of Cervical and Lumbar Lordosis: How Good Are We? Spine 2003, 28, 1857–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A. , Punt D, Johnson M. (2009) ‘A postal survey gathering information about physiotherapists’ assessment of head posture for patients with chronic idiopathic neck pain’, European Journal of Pain. 13:S223.

- Silva, A.G.; Punt, T.D.; Sharples, P.; Vilas-Boas, J.P.; Johnson, M.I. Head Posture and Neck Pain of Chronic Nontraumatic Origin: A Comparison Between Patients and Pain-Free Persons. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabilitation 2009, 90, 669–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ailliet, L.; Rubinstein, S.M.; de Vet, H.C. Characteristics of Chiropractors and their Patients in Belgium. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 2010, 33, 618–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinton, P.M.; McLeod, R.; Broker, B.; Maclellan, C.E. Outcome measures and their everyday use in chiropractic practice. . 2010, 54, 118–31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- A Puhl, A.; Reinhart, C.J.; Injeyan, H.S. Diagnostic and treatment methods used by chiropractors: A random sample survey of Canada's English-speaking provinces. . 2015, 59, 279–87. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bone and Joint Decade: Global Alliance for Musculoskeletal Health. (2017) The Neck. Available at: http://bjdonline.org/the-neck/. (Accessed: 20 Feb 2017).

- World Health Organization (2003) Preventing musculoskeletal disorders in the workplace. Switzerland: World Health organization. Available at: https://www.who.int/occupational_health/publications/en/oehmsd3.pdf. (Accessed: ). 14 August.

- International Organization for Standardization (2000) International Standard ISO 11226. Ergonomics – evaluation of static working postures. Available at: https://www.iso.org/standard/25573.html.

- NHS (2019) Common posture mistakes and fixes. Available at: http://www.nhs.uk/Livewell/Backpain/Pages/back-pain-and-common-posture- mistakes.aspx (Accessed: ). 2 July.

- Khaleeli, H. (2014) ‘Text neck: how smartphones are damaging our spines’ The Guardian.

- https://www.theguardian. 2014.

- cessed:10 Jan 2017).

- Snodgrass, S. (2016) ‘Is bad posture giving you a hunchback? Expert reveals how to prevent slumping at your desk from damaging your spine’, Daily Mail. 16 May. Available at: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-3592690/Is-bad-posture- giving-hunchback-Expert-reveals-prevent-slumping-desk-damaging-spine.html. (Accessed: 20 Feb 2020).

- Kritz, M.F.; Cronin, J. Static Posture Assessment Screen of Athletes: Benefits and Considerations. Strength Cond. J. 2008, 30, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E Fikar, P.; A Edlund, K.; Newell, D. Current preventative and health promotional care offered to patients by chiropractors in the United Kingdom: a survey. Chiropr. Man. Ther. 2015, 23, 10–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Schaik, P.; Bettany-Saltikov, J.A.; Warren, J.G. Clinical acceptance of a low-cost portable system for postural assessment. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2002, 21, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Chiropractic Council (2010b) Your first visit? Available at: https://www.gcc- uk.org/chiropractic-standards/seeing-a-chiropractor-for-the-first-time (Accessed: ). 1 July.

- Harrison, D.E.; Harrison, D.D.; Troyanovich, S.J.; Harmon, S. A normal spinal position: It's time to accept the evidence. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 2000, 23, 623–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newell, D.; Diment, E.; E Bolton, J. An Electronic Patient-Reported Outcome Measures System in UK Chiropractic Practices: A Feasibility Study of Routine Collection of Outcomes and Costs. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 2016, 39, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DE Looze, M.P.; Toussaint, H.M.; Ensink, J.; Mangnus, C.; VAN DER Beek, A.J. The validity of visual observation to assess posture in a laboratory-simulated, manual material handling task. Ergonomics 1994, 37, 1335–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Question |

| Q 1. Please tick ONE box to indicate how frequently you use postural assessment with a NEW patient who comes to you with back or neck pain. |

| Almost always (76-100% of the time) |

| Frequently (51-75% of the time) |

| Some of the time (26-50% of the time) |

| Rarely (1-25% of the time) |

| Never |

|

Q2. As you answered ‘always’, ‘frequently’ or ‘some of the time’ to the previous question, please tick as many of the statements you agree with. I use postural assessment because: |

| It provides an outcome measure |

| It helps inform my diagnosis |

| It helps inform my treatment |

| It helps me determine whether a patient is making progress or not |

| It is mandatory (employer requires it) |

| I was taught to use it during my training |

| Other (please specify)……………………………………………. |

|

Q3. As you answered ‘rarely or ‘never’ to the previous question, please tick any of the following statements you agree with. I rarely or never carry out postural assessments because: |

| I don’t have time |

| Postural assessment is not relevant to my diagnosis or treatment |

| I don’t believe it is accurate or objective |

| My patients don’t like it or it is not appropriate for them |

| I was not taught to use it |

| Other (please specify)……………………………………………. |

|

Q4. What methods do you use to carry out postural assessment? You may choose more than one option or tick as many as apply. |

| Visually |

| Using a plumb line |

| Using a photograph |

| Using a flexirule/flexicurve |

| Using an inclinometer |

| Using an APP on a mobile phone |

| Using computer software |

| Other (please specify)……………………………………………. |

| Q5. From which positions do you assess your subject?You may choose more than one option. |

| Both left and right sides |

| Right lateral only |

| Left lateral only |

| Posterior |

| Anterior Posterior |

|

Q6. If you perform POSTERIOR postural assessment with back- and neck pain patients, what are the things you observe? You may choose more than one option. |

| Symmetry between left and right sides of the body |

| Foot position |

| Achilles tendon |

| Knee creases |

| Genu valgus/varus |

| Hypertrophy/atrophy of lower limb muscles |

| Gluteal folds |

| Gluteal contours |

| PSISs |

| Iliac crests |

| Rib cage |

| Rib hump |

| Scoliosis |

| Size of the keyhole (gap between the upper limb and thorax) |

| Hypertrophy/atrophy of the upper limb |

| Inferior angles of scapulae |

| Vertebral borders of the scapulae (distance laterally from the spine) |

| Acromion process |

| Mastoid process |

| Other (please specify) ……………………………………………. |

|

Q7. If you perform ANTERIOR postural assessment with back- and neck pain patients, what are the things you observe? You may choose more than one option. |

| General symmetry between left and right sides of the body |

| Feet |

| Knees |

| Genu valgus/ varus |

| Hypertrophy/atrophy of lower limb muscles |

| Greater trochanters |

| ASISs |

| Iliac crests |

| Rib cage |

| Size of the “keyhole” (gap between the upper limb and thorax) |

| Hypertrophy/atrophy of upper limb muscles |

| Clavicles |

| Acromioclavicular joints |

| Muscles of the neck |

| Mastoid processes |

| Facial symmetry |

| Other (please specify) ……………………………………………. |

|

Q 8. If you perform a LATERAL postural assessment with back- and neck pain patients, what are the things you observe? You may choose more than one option. |

| Head position |

| Shape of cervical spine |

| Shape of thoracic spine |

| Shape of lumbar spine |

| Position of pelvis – anterior or posterior pelvic tilt |

| Shoulder position |

| Position of upper limb |

| Position of lower limb – e.g., genu recuravtum/genum flexum |

| Overall body shape |

| Other (please specify) ……………………………………………. |

| Q 9.Thinking only about patients with back or neck pain, which sorts of pathologies do you come across commonly in your practice? Please note, the following are only some of the possible pathologies you may commonly come across. (Please tick as many as apply and use the ‘other’ box to add others) |

| whiplash |

| stiff neck |

| torticollis |

| muscle strain of the neck region |

| arthritis in the cervical spine |

| herniation of an intervertebral disc in cervical spine |

| thoracic pain |

| muscle strain of the thoracic region |

| arthritis in the thoracic spine |

| herniation of an intervertebral disc in thoracic spine |

| spinal deformity (e.g., scoliosis) |

| non-specific low back pain |

| muscle strain of the lumbar spine |

| herniation of an intervertebral disc in lumbar spine |

| arthritis in the lumbar spine |

| sacroiliac pain |

| arthritis in the sacroiliac joints |

| coccygeal pain |

| Other (please specify) ……………………………………………. |

| Q10. Is there anything else you would like to say about your use of postural assessment? |

| please specify) ……………………………………………. |

| Q11. Finally, please select the answer that most closely represents your profession: |

| Chiropractor Osteopath Physiotherapist |

| Sports Therapist |

| Osteopath |

| Physiotherapist |

| Other (please specify) ……………………………………………. |

| Survey question | Number of free-text responses | Percentage (%) agreement |

| 1. No free-text option | NA | NA |

| 2.As you answered ‘always’, ‘frequently’ or ‘some of the time’ to the previous question, please tick as many of the statements you agree with. I use postural assessment because:R where are the statements they were responding to? | 28 | 21 had 100% agreement 2 had 50% agreement 5 had no agreement |

|

3.As you answered ‘rarely’ or ‘never’ to the previous question, please tick any of the following statements you agree with. I rarely or never carry out postural assessment because: |

0 | NA |

|

4.What methods do you use to carry out postural assessment? You may choose more than one option or tick as many as apply. |

17 | 16 had 100% agreement 1 had no agreement |

| 5.No free-text option | NA | NA |

|

6.If you perform POSTERIOR postural assessment with back and neck pain patients, what are the things you observe? You may choose more than one option. |

31 | 24 had 100% agreement 1 had 40% agreement 1 had 33% agreement 2 had 25% agreement 1 had 20% agreement 2 had zero agreement |

| 7.If you perform ANTERIOR postural assessment with back and neck pain patients, what are the things you observe? You may choose more than one option. | 28 | 26 had 100% agreement 1 had 75% agreement 1 had no agreement |

| 8.LATERAL postural assessment with back and neck pain patients, what are the things you observe? You may choose more than one option. | 18 | 6 had 100% agreement 6 had 50% agreement 1 had 33% agreement 1 had 20% agreement 4 had no agreement |

| 9.Thinking only about patients with back or neck pain, which sort of pathologies do you come across commonly in your practice? Please note, the following are only some of the possible pathologies you may commonly come across. (Please tick as many as apply and use the ‘other’ box to add others). | 41 | 26 had 100% agreement 1 had 83% agreement 1 had 66% agreement 1 had 62.5% agreement 6 had 50% agreement 2 had 33% agreement 3 had no agreement 1 response would not be rated |

| 10.Is there anything else you would like to say about your use of postural assessment? | 66 | 34 had 100% agreement 13 had 50% agreement 2 had 66% agreement 1 had 33% agreement 16 had no agreement |

| 11.No free-text option | NA | NA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).