Submitted:

21 October 2025

Posted:

21 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

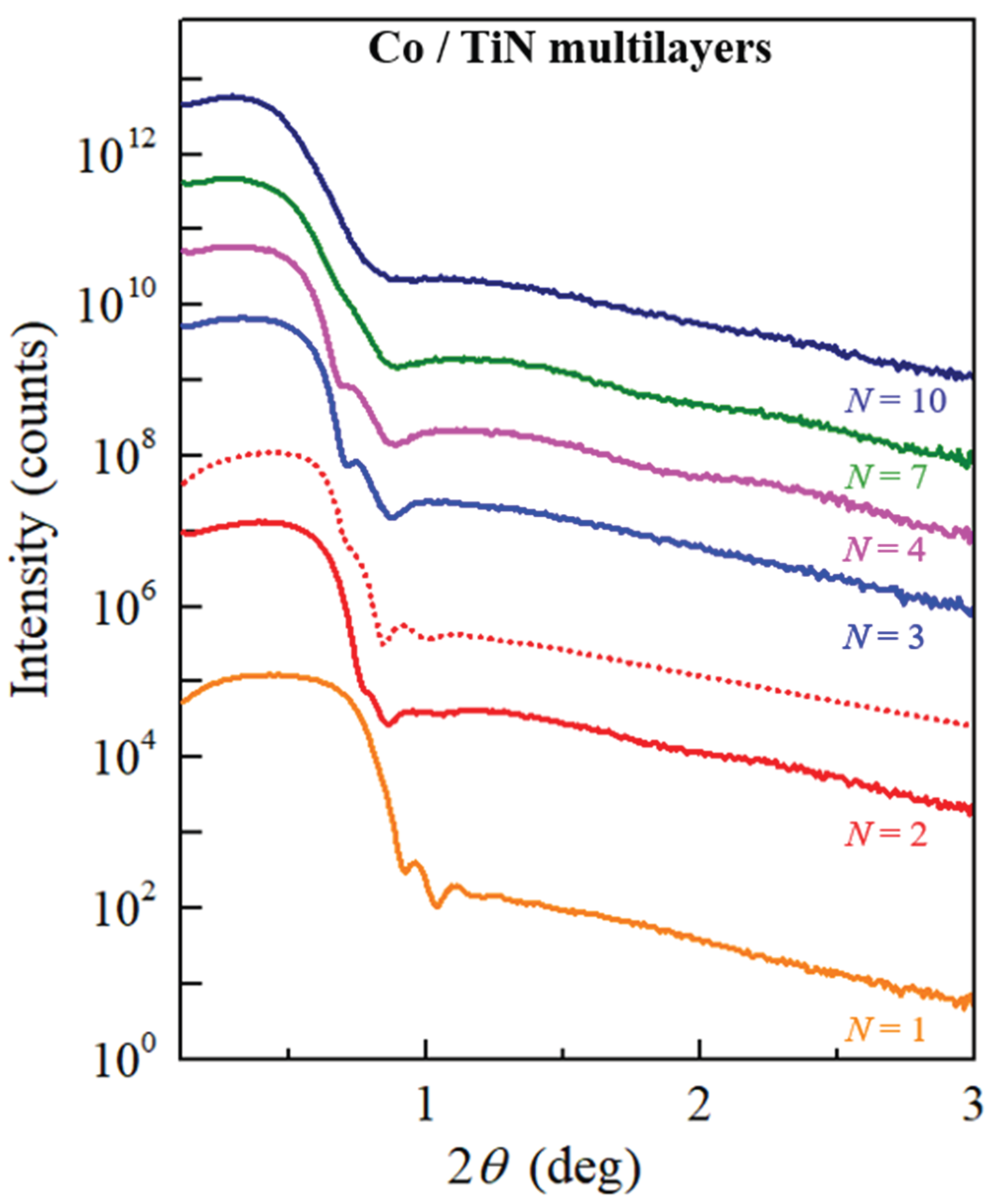

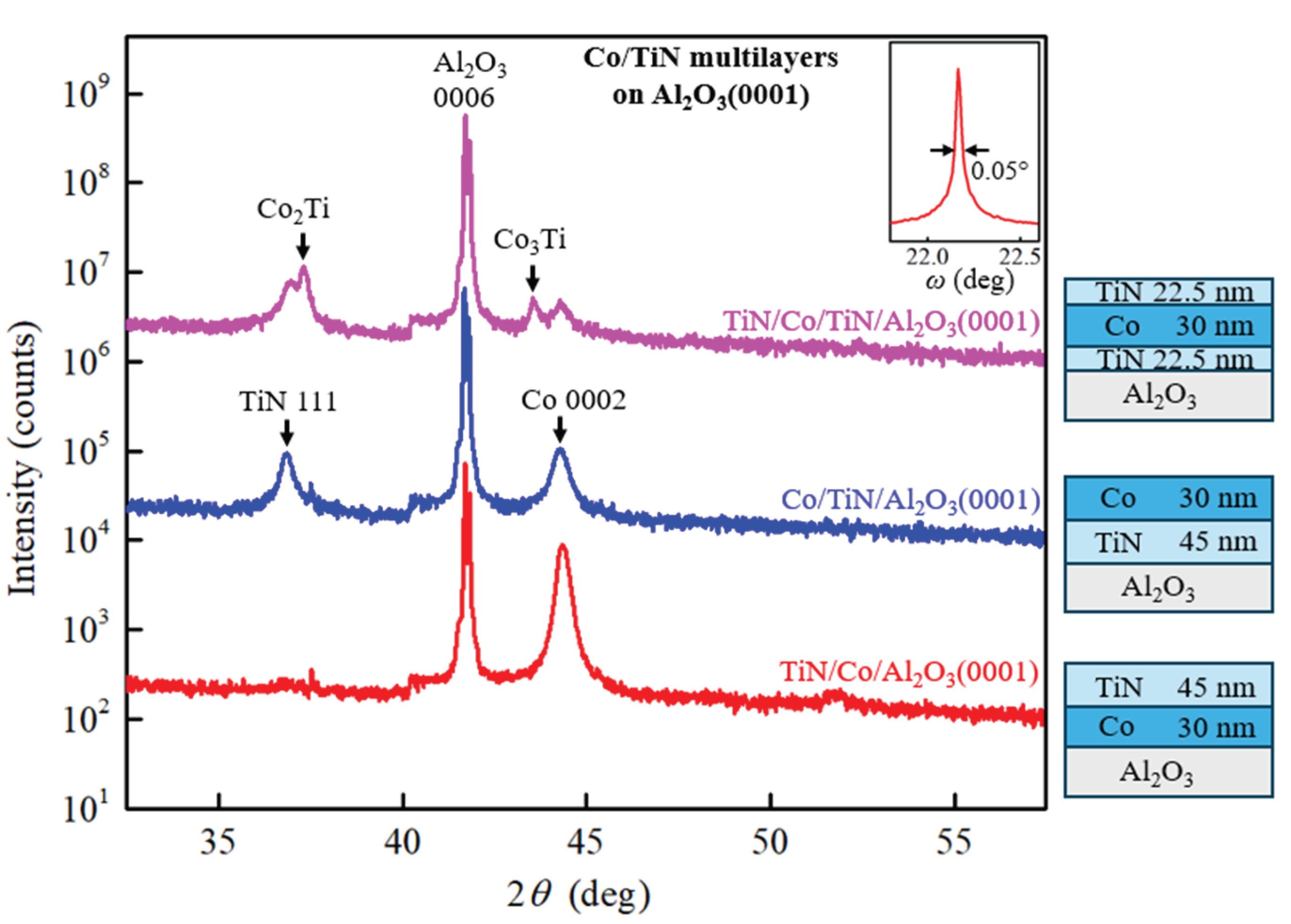

Electron transport measurements on Co/TiN multilayers are employed to explore the effect of TiN layers on the Co resistivity. 50-nm-thick multilayer stacks containing N = 1-10 individual Co layers that are separated by 1-nm-thick TiN layers are sputter deposited on SiO2/Si(001) substrates at 400 °C. X-ray diffraction and reflectivity measurements indicate a tendency for a 0001 preferred orientation, an x-ray coherence length of 13 nm that is nearly independent of N, and an interfacial roughness that increases with N. The in-plane multilayer resistivity ρ increases with increasing N = 1-10, from ρ = 14.4 to 36.6 µΩ-cm at room temperature and from ρ = 11.2 to 19.4 µΩ-cm at 77 K. This increase is due to a combination of increased electron scattering at interfaces and grain boundaries, as quantified using a combined Fuchs-Sondheimer and Mayadas-Shatzkes model. The analysis indicates that a decreasing thickness of the individual Co layers dCo from 50 to 5 nm causes not only an increasing resistivity contribution from Co/TiN interface scattering (from 9 to 88% with respect to the room temperature bulk resistivity), but also an increasing (39 to 154%) grain boundary scattering contribution which exacerbates the resistivity penalty due to the TiN liner. These results are supported by Co/TiN bilayer and trilayer structures deposited on Al2O3 (0001) at 600 °C. Interfacial intermixing causes Co2Ti and Co3Ti alloy phase formation, an increase in the contact resistance, a degradation of the Co crystalline quality, and a 2.3× higher resistivity for Co deposited on TiN than Co directly deposited on Al2O3(0001). The overall results show that TiN liners cause a dramatic increase in Co interconnects due to diffuse surface scattering, interfacial intermixing/roughness, and Co grain renucleation at Co/TiN interfaces.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Data Availability

Acknowledgments

Author Declarations

References

- Kim, H. Recent Trends in Copper Metallization. Electronics 2022, 11, 2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossnagel, S.M.; Kuan, T.S. Alteration of Cu Conductivity in the Size Effect Regime. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B 2004, 22, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gall, D. Metals for Low-Resistivity Interconnects. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Interconnect Technology Conference (IITC); IEEE, June 2018; pp. 157–159. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.H.; Wang, L.; Guo, Z.; Chen, X.; Liu, J.; Huang, X.J. Copper Nanowires as Nanoscale Interconnects: Their Stability, Electrical Transport, and Mechanical Properties. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jog, A.; Zheng, P.; Zhou, T.; Gall, D. Anisotropic Resistivity Size Effect in Epitaxial Mo(001) and Mo(011) Layers. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jog, A.; Gall, D. Electron Scattering at Surfaces and Grain Boundaries in Rh Layers. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2022, 69, 3854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Gall, D. Resistivity Size Effect in Epitaxial VNi2 Layers. J. Appl. Phys. 2023, 134, 105302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Gall, D. CuTi as Potential Liner- and Barrier-Free Interconnect Conductor. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2024, 71, 3252–3257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Gall, D. Resistivity Scaling Due to Electron Surface Scattering in Thin Metal Layers. Phys. Rev. B 2018, 97, 165406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reider, A.M.; Kronthaler, A.; Zappa, F.; Menzel, A.; Laimer, F.; Scheier, P. Comparison of Continuous and Pulsed Low-Power DC Sputtered Ti Thin Films Deposited at Room Temperature. Surfaces 2025, 8, 19–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, J.S.; Gall, D. Epitaxial Ag(001) Grown on MgO(001) and TiN(001): Twinning, Surface Morphology, and Electron Surface Scattering. J. Appl. Phys. 2012, 111, 043708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, J.S.; Zhang, X.Y.; Gall, D. Epitaxial TiN(001) Wetting Layer for Growth of Thin Single-Crystal Cu(001). J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 110, 043714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, P.; Gall, D. Electron Scattering at Interfaces in Epitaxial W(001)-Mo(001) Multilayers. J. Appl. Phys. 2024, 136, 075305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, P.; Lavoie, C.; Gall, D. Electron Scattering at Interfaces in Ru(0001)/Co(0001) Multilayers. J. Appl. Phys. 2025, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milosevic, E.; Gall, D. Electron Scattering at Co(0001) Surfaces: Effects of Ti and TiN Capping Layers. AIP Adv. 2020, 10, 055213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Jog, A.; Gall, D. First-Principles Prediction of Electron Grain Boundary Scattering in Fcc Metals. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2022, 120, 241603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- César, M.; Gall, D.; Guo, H. Reducing Grain-Boundary Resistivity of Copper Nanowires by Doping. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2016, 5, 054018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, J.S.; Gstrein, F.; Brien, K.P.O.; Clarke, J.S.; Gall, D. Electron Scattering at Surfaces and Grain Boundaries in Cu Thin Films and Wires. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 84, 235423–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jog, A.; Gall, D. Resistivity Size Effect in Epitaxial Iridium Layers. J. Appl. Phys. 2021, 130, 115103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Gall, D. Resistivity Scaling in Epitaxial CuAl 2 (001) Layers. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2022, 69, 5110–5115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milosevic, E.; Kerdsongpanya, S.; Mcgahay, M.E.; Wang, B.; Gall, D. The Resistivity Size Effect in Epitaxial Nb(001) and Nb(011) Layers. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2019, 66, 3473–3478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gall, D. The Search for the Most Conductive Metal for Narrow Interconnect Lines. J. Appl. Phys. 2020, 127, 050901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Gall, D. The Anisotropic Size Effect of the Electrical Resistivity of Metal Thin Films: Tungsten. J. Appl. Phys. 2017, 122, 135301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.K.; Gignac, L.; Rosenberg, R. Electromigration of Cu/Low Dielectric Constant Interconnects. Microelectron. Reliab. 2006, 46, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaloyeros, A.E.; Eisenbraun, E. Ultrathin Diffusion Barriers/Liners for Gigascale Copper Metallization. Annu. Rev. Mater. Sci. 2000, 30, 363–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. G. Wen, P. Roussel, O. V. Pedreira, B. Briggs, B. Groven, S. Dutta, M. I. Popovici, N. Heylen, I. Ciofi, K. Vanstreels, F. W. Østerberg, O. Hansen, D. H. Petersen, K. Opsomer, C. Detavernie, C. J. Wilson, S. V. Elshocht, K. Croes, J. Bömmels, Z.T.; Adelmann, C. Atomic Layer Deposition of Ruthenium with TiN Interface for Sub-10 Nm Advanced Interconnects beyond Copper. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 26119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Zhang, X.; Nogami, T.; Lin, X.; Kelly, J.; Kim, H.; Spooner, T.; Edelstein, D.; Zhao, L. Mechanism of Co Liner as Enhancement Layer for Cu Interconnect Gap-Fill. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2013, 160, D3040–D3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Zhou, T.; Gall, D. Electron Channeling in TiO2 Coated Cu Layers. Semicond. Sci. Technol 2016, 31, 055005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.Y.; Deng, R.P.; Gall, D. Ni Doping on Cu Surfaces: Reduced Copper Resistivity. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 105, 131603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sondheimer, E.H. The Mean Free Path of Electrons in Metals. Adv. Phys. 1952, 1, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, M.S.P. Electrical Conductivity of Thin Metallic Films with Unlike Surfaces. J. Appl. Phys. 1965, 36, 1632–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nies, C.L.; Natarajan, S.K.; Nolan, M. Control of the Cu Morphology on Ru-Passivated and Ru-Doped TaN Surfaces-Promoting Growth of 2D Conducting Copper for CMOS Interconnects. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 713–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Gall, J. J. Cha, Z. Chen, H. J. Han, C. Hinkle, J.A. Robinson, R. Sundararaman, R. Torsi Materials for Interconnects. MRS Bull. 2021, 46, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Lanzillo, N.A.; Bhosale, P.; Gall, D.; Quon, R. A First-Principles Analysis of Ballistic Conductance, Grain Boundary Scattering and Vertical Resistance in Aluminum Interconnects. AIP Adv. 2018, 8, 055127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mont, F.W.; Zhang, X.; Wang, W.; Kelly, J.J.; Standaert, T.E.; Quon, R.; Ryan, E.T. Cobalt Interconnect on Same Copper Barrier Process Integration at the 7nm Node. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Interconnect Technology Conference (IITC); IEEE, May 2017; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Thakral, A.; Jog, A.; Gall, D. Resistivity Size Effect in Epitaxial Face-Centered Cubic Co(001) Layers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2024, 124, 121601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Xu, J.; Mao, S.; Zhao, C.; Wang, G.; Luo, X.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, W.; Chen, D.; et al. Co-Sputtering Co–Ti Alloy as a Single Barrier/Liner for Co Interconnects and Thermal Stability Enhancement Using TiN Metal Capping. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2019, 30, 10579–10588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milosevic, E.; Kerdsongpanya, S.; McGahay, M.E.; Zangiabadi, A.; Barmak, K.; Gall, D. Resistivity Scaling and Electron Surface Scattering in Epitaxial Co(0001) Layers. J. Appl. Phys. 2019, 125, 245105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeoh, A. ; A. Madhavan; N. Kybert; S. Anand; J. Shin; M. Asoro; S. Samarajeewa; J. Steigerwald; C. Ganpule; M. Buehler; et al. Interconnect Stack Using Self-Aligned Quad and Double Patterning for 10nm High Volume Manufacturing.; in IEEE International Interconnect Technology Conference (IITC) (IEEE, 2018); p. 144.

- Chawla, J.S.; Zhang, X.Y.; Gall, D. Effective Electron Mean Free Path in TiN(001). J. Appl. Phys. 2013, 113, 063704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, M.A.; Cahill, D.G.; Petrov, I.; Gall, D.; Greene, J.E. Nucleation Kinetics during Homoepitaxial Growth of TiN(001) by Reactive Magnetron Sputtering. Phys. Rev. B 2004, 70, 035413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, J.S.; Gall, D. Specular Electron Scattering at Single-Crystal Cu(001) Surfaces. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009, 94, 252101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milosevic, E.; Kerdsongpanya, S.; Zangiabadi, A.; Barmak, K.; Coffey, K.R.; Gall, D. Resistivity Size Effect in Epitaxial Ru(0001) Layers. J. Appl. Phys. 2018, 124, 165105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, P.; Gall, D. Electron Scattering at Ru–TiN–Ru Interface Stacks. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2024, 71, 6970–6975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, P.; Gall, D. Metal-Metal Contact Resistance Measurements. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Interconnect Technology Conference (IITC); IEEE, June 3 2024; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Smits, F.M. Measurement of Sheet Resistivities with the Four-Point Probe. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1958, 37, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, K. The Conductivity of Thin Metallic Films According to the Electron Theory of Metals. Math. Proc. Cambridge Philos. Soc. 1938, 34, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayadas, A.F.; Shatzkes, M. Electrical-Resistivity Model for Polycrystalline Films: The Case of Arbitrary Reflection at External Surfaces. Phys. Rev. B 1970, 1, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milosevic, E.; Kerdsongpanya, S.; Gall, D. The Resistivity Size Effect in Epitaxial Ru(0001) and Co(0001) Layers. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Nanotechnology Symposium (ANTS); IEEE, November 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.F.; Lang, X.Y.; Zheng, W.T.; Jiang, Q. Electron Scattering and Electrical Conductance in Polycrystalline Metallic Films and Wires: Impact of Grain Boundary Scattering Related to Melting Point. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 3781–3788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, A.K.; Chaudhuri, S.; Barua, A.K. The Electrical Resistivity and Temperature Coefficient of Resistivity of Cobalt Films. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. 1976, 9, 2261–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wislicenus, M.; Liske, R.; Gerlich, L.; Vasilev, B.; Preusse, A. Cobalt Advanced Barrier Metallization: A Resistivity Composition Analysis. Microelectron. Eng. 2015, 137, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulmaa, A.; Cougnon, F.G.; Dedoncker, R.; Depla, D. On the Grain Size-Thickness Correlation for Thin Films. Acta Mater. 2021, 212, 116896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Park, K.R.; Haq, M.A.; Sung, J.M.; Jeong, D.W.; Song, Y.; Kim, B.S. In-Situ Nitriding of CoTi Powders for TiN Shell Formation via Diffusion-Controlled Mechanism. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1036, 181886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakral, A.; Shu, R.; Palisaitisc, J.; Gall, D. Phase Formation Kinetics of Metastable Fcc Cobalt. submitted 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.S.; Lin, M.J.; Huang, C.W.; Cheng, Y.L.; Fang, J.S.; Lin, C.I. The Impact of Titanium Alloying on Altering Nanomechanical Properties and Grain Structures of Sputter-Deposited Cobalt for Electromigration Reliability Enhancement. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1003, 175564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongpiya, R.; Ouyang, J.; Chung, C.J.; Duong, D.T.; Deal, M.; Nishi, Y.; Clemens, B. Structural and Electrical Characterization of CoTiN Metal Gates. J. Appl. Phys. 2015, 117, 075304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, M.; Koike, J. Amorphous CoTix as a Liner/Diffusion Barrier Material for Advanced Copper Metallization. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 721, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Rs (Ω/sq) | ||||

| TiN | / Co | / Al2O3(0001) | 4.7 | |

| 45 nm | 30 nm | |||

| Co | / TiN | / Al2O3(0001) | 8.0 | |

| 30 nm | 45 nm | |||

| TiN | / Co | / TiN | / Al2O3(0001) | 18.1 |

| 22.5 nm | 30 nm | 22.5 nm | ||

| TiN | / Al2O3(0001) | 23.8 | ||

| 45 nm | ||||

| Co | / Al2O3(0001) | 3.3 | ||

| 30 nm |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).