Submitted:

20 October 2025

Posted:

21 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

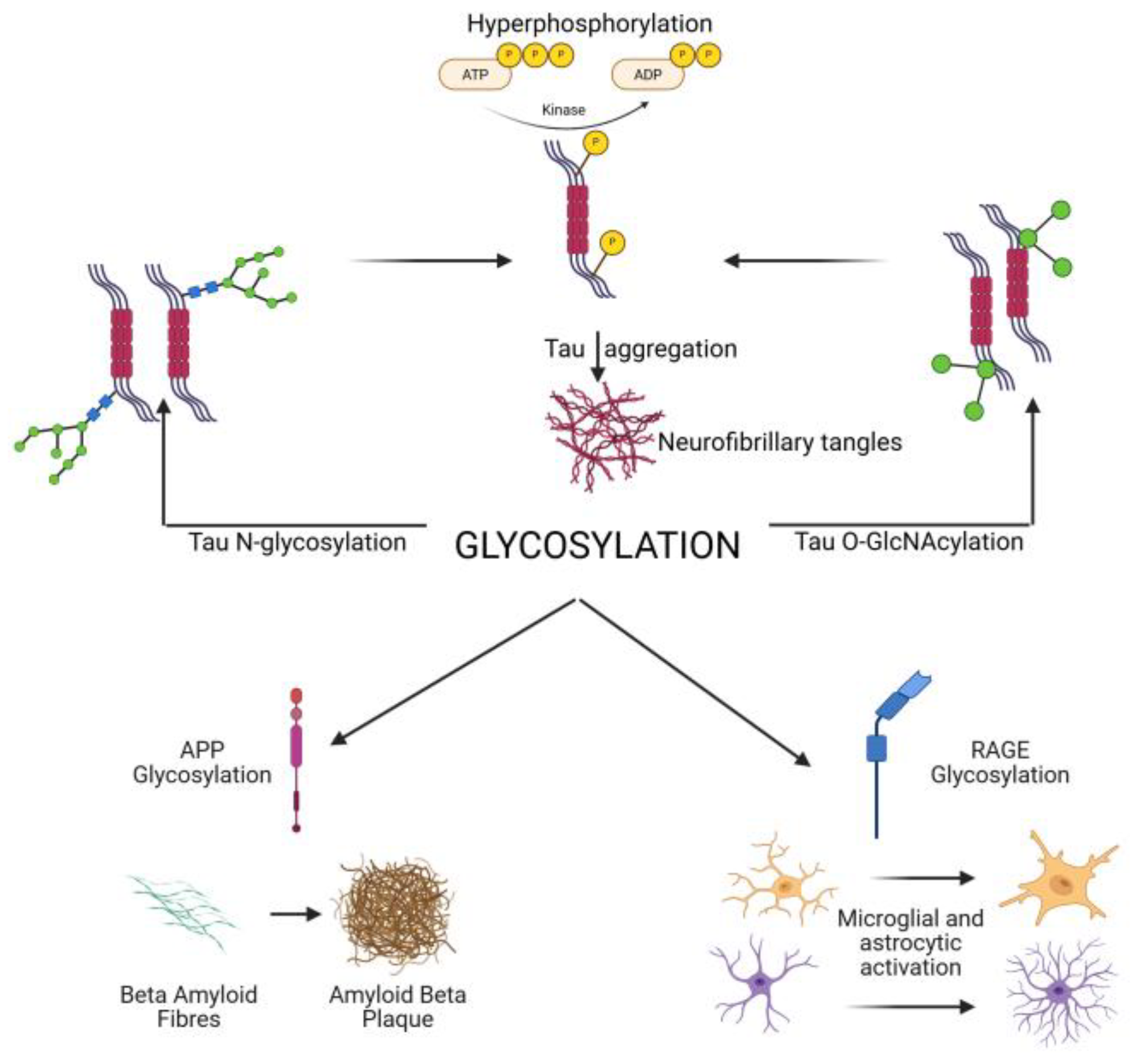

2. Tau Glycosylation in Alzheimer’s and Related Tauopathies

2.1. N-glycosylation of Tau

2.2. O-GlcNAcylation of Tau

2.3. Glycosylation in Other Tauopathies

2.4. Interplay Between Glycosylation and Phosphorylation

3. Glycosylation and Amyloid-β Pathology

3.1. APP N-glycosylation and Trafficking

3.2. O-glycosylation and Secretase Regulation

3.3. Aberrant Glycosylation of Aβ Peptides

3.5. Implications for Therapy

4. Glycosylation, Synaptic Function, and Neuroinflammation

4.1. Glycosylation of Synaptic Receptors and Adhesion Molecules

4.2. Immune Receptor Glycosylation and Microglial Activation

4.3. Cytokines, Chemokines, and Glycosylation

4.4. Glycosylation and the Complement System

4.5. Neuroinflammation Beyond Amyloid and Tau

4.6. Therapeutic Implications

5. Advances in Glycoproteomics and Biomarker Discovery

5.1. Glycoproteomic Alterations in Alzheimer’s Disease

5.2. Glycosylation as a Diagnostic and Prognostic Biomarker

5.3. Mass Spectrometry and Glycoproteomic Technologies

5.4. Immunoglobulin Glycosylation and Systemic Biomarkers

5.5. Integration with Multimodal Biomarkers

5.6. Challenges and Opportunities

6. Enzymatic Regulators of Glycosylation in Neurodegeneration

6.1. Glycosyltransferases in AD and Tauopathies

6.2. Glycosidases and Tau Pathology

6.3. Hexosamine Biosynthetic Pathway and Metabolic Regulation

6.4. Crosstalk with Phosphorylation Pathways

6.5. Enzymatic Dysregulation as Biomarkers

6.6. Therapeutic Implications

7. Discussion

7.1. Glycosylation and the Hierarchy of Pathological Events

7.2. Protective Versus Pathogenic Roles

7.3. Crosstalk with Metabolism and Phosphorylation

7.4. Neuroinflammation as a Glycosylation-Driven Amplifier

7.5. Biomarker Potential and Translational Challenges

7.6. Therapeutic Perspectives

7.7. Remaining Controversies

8. Future Directions

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gao, G.; Li, C.; Fan, W.; Zhang, M.; Li, X.; Chen, W.; Li, W.; Liang, R.; Li, Z.; Zhu, X. Brilliant Glycans and Glycosylation: Seq and Ye Shall Find. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 189, 279–291. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Park, H.; Kim, Y.; Kim, S.-H.; Lee, J.H.; Yang, H.; Kim, S.J.; Li, C.M.; Lee, H.; Na, D.-H.; et al. Pathogenic Role of RAGE in Tau Transmission and Memory Deficits. Biol. Psychiatry 2023, 93, 829–841. [CrossRef]

- Yi, L.; Fu, M.; Shao, Y.; Tang, K.; Yan, Y.; Ding, C.-F. Bifunctional Super-Hydrophilic Mesoporous Nanocomposite: A Novel Nanoprobe for Investigation of Glycosylation and Phosphorylation in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Chromatogr. A 2022, 1676, 463236. [CrossRef]

- Maria, C.; Rauter, A.P. Nucleoside Analogues: N-Glycosylation Methodologies, Synthesis of Antiviral and Antitumor Drugs and Potential against Drug-Resistant Bacteria and Alzheimer’s Disease. Carbohydr. Res. 2023, 532, 108889. [CrossRef]

- Tachida, Y.; Iijima, J.; Takahashi, K.; Suzuki, H.; Kizuka, Y.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Nakano, M.; Takakura, D.; Kawasaki, N.; et al. O-GalNAc Glycosylation Determines Intracellular Trafficking of APP and Aβ Production. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299, 104905. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, H.-L.; Wang, J.-Z.; Liu, R.; Wang, X. Abnormal Protein Post-Translational Modifications Induces Aggregation and Abnormal Deposition of Protein, Mediating Neurodegenerative Diseases. Cell Biosci. 2024, 14, 22. [CrossRef]

- Tsay, H.-J.; Huang, Y.-C.; Chen, Y.-J.; Lee, Y.-H.; Hsu, S.-M.; Tsai, K.-C.; Yang, C.-N.; Huang, F.-L.; Shie, F.-S.; Lee, L.-C.; et al. Identifying N-Linked Glycan Moiety and Motifs in the Cysteine-Rich Domain Critical for N-Glycosylation and Intracellular Trafficking of SR-AI and MARCO. J. Biomed. Sci. 2016, 23, 27. [CrossRef]

- Akasaka-Manya, K.; Manya, H. The Role of APP O-Glycosylation in Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1569. [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.C.; Jensen, E.H.; Rexach, J.E.; Vinters, H.V.; Hsieh-Wilson, L.C. Loss of O -GlcNAc Glycosylation in Forebrain Excitatory Neurons Induces Neurodegeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2016, 113, 15120–15125. [CrossRef]

- Mashal, Y.; Abdelhady, H.; Iyer, A.K. Comparison of Tau and Amyloid-β Targeted Immunotherapy Nanoparticles for Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1001. [CrossRef]

- Fastenau, C.; Bunce, M.; Keating, M.; Wickline, J.; Hopp, S.C.; Bieniek, K.F. Distinct Patterns of Plaque and Microglia Glycosylation in Alzheimer’s Disease. Brain Pathol. 2024, 34, e13267. [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Ren, X.; Zhang, W.; Dong, M.; Ge, Y.; Yu, Y.; Ye, M. Development of Complementary Enrichment Strategies for Analysis of N-Linked Intact Glycopeptides and Potential Site-Specific Glycoforms in Alzheimer’s Disease. Talanta 2026, 297, 128595. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Sahu, M.; Srivastava, D.; Tiwari, S.; Ambasta, R.K.; Kumar, P. Post-Translational Modifications: Regulators of Neurodegenerative Proteinopathies. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 68, 101336. [CrossRef]

- Krawczuk, D.; Kulczyńska-Przybik, A.; Mroczko, B. The Potential Regulators of Amyloidogenic Pathway of APP Processing in Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1513. [CrossRef]

- Kizuka, Y.; Kitazume, S.; Taniguchi, N. N -Glycan and Alzheimer’s Disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA - Gen. Subj. 2017, 1861, 2447–2454. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, S.; Itoh, M. Synergistic Effects of Mutation and Glycosylation on Disease Progression. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2025, 12, 1550815. [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Yuan, Z.; Yang, S.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Can, D.; Lei, A.; Li, H.; Leng, L.; Zhang, J. Mannose Promotes β-Amyloid Pathology by Regulating BACE1 Glycosylation in Alzheimer’s Disease. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, 2409105. [CrossRef]

- Moniruzzaman, M.; Ishihara, S.; Nobuhara, M.; Higashide, H.; Funamoto, S. Glycosylation Status of Nicastrin Influences Catalytic Activity and Substrate Preference of γ-Secretase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 502, 98–103. [CrossRef]

- C, R.Cathrine.; Lukose, B.; Rani, P. G82S RAGE Polymorphism Influences Amyloid-RAGE Interactions Relevant in Alzheimer’s Disease Pathology. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0225487. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, M.; Sun, J.; Guo, A.; Fernando, R.L.; Chen, Y.; Peng, P.; Zhao, G.; Deng, Y. DPP-4 Inhibitor Improves Learning and Memory Deficits and AD-like Neurodegeneration by Modulating the GLP-1 Signaling. Neuropharmacology 2019, 157, 107668. [CrossRef]

- Aljadaan, A.M.; AlSaadi, A.M.; Shaikh, I.A.; Whitby, A.; Ray, A.; Kim, D.-H.; Carter, W.G. Characterization of the Anticholinesterase and Antioxidant Properties of Phytochemicals from Moringa Oleifera as a Potential Treatment for Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2148. [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Allen, M.; Sakae, N.; Ertekin-Taner, N.; Graff-Radford, N.R.; Dickson, D.W.; Younkin, S.G.; Sevlever, D. Expression and Processing Analyses of Wild Type and p.R47H TREM2 Variant in Alzheimer’s Disease Brains. Mol. Neurodegener. 2016, 11, 72. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Q.; Wang, L.H.; Zhan, Q.W.; Liu, Y.L.; Zhang, Q.; Li, J.F.; Fan, F.F. Mapping Quantitative Trait Loci for Five Forage Quality Traits in a Sorghum-Sudangrass Hybrid. Genet. Mol. Res. 2015, 14, 13266–13273. [CrossRef]

- Tolstova, A.P.; Adzhubei, A.A.; Mitkevich, V.A.; Petrushanko, I.Yu.; Makarov, A.A. Docking and Molecular Dynamics-Based Identification of Interaction between Various Beta-Amyloid Isoforms and RAGE Receptor. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11816. [CrossRef]

- Mocanu, A.-I.; Mocanu, H.; Moldovan, C.; Soare, I.; Niculet, E.; Tatu, A.L.; Vasile, C.I.; Diculencu, D.; Postolache, P.A.; Nechifor, A. Some Manifestations of Tuberculosis in Otorhinolaryngology – Case Series and a Short Review of Related Data from South-Eastern Europe. Infect. Drug Resist. 2022, Volume 15, 2753–2762. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Ji, I.J.; An, H.J.; Kang, M.; Kang, S.; Kim, D.; Yoon, S. Disease-Associated Mutations of TREM2 Alter the Processing of N-Linked Oligosaccharides in the Golgi Apparatus. Traffic 2015, 16, 510–518. [CrossRef]

- Shirotani, K.; Hatta, D.; Wakita, N.; Watanabe, K.; Iwata, N. The Role of TREM2 N-Glycans in Trafficking to the Cell Surface and Signal Transduction of TREM2. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 2022, 172, 347–353. [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Schindler, R.L.; Di Lucente, J.; Oloumi, A.; Tena, J.; Harvey, D.; Lebrilla, C.B.; Zivkovic, A.M.; Jin, L.-W.; Maezawa, I. Unique N-Glycosylation Signatures in Human iPSC Derived Microglia Activated by Aβ Oligomer and Lipopolysaccharide. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 12348. [CrossRef]

- Gizaw, S.T.; Ohashi, T.; Tanaka, M.; Hinou, H.; Nishimura, S.-I. Glycoblotting Method Allows for Rapid and Efficient Glycome Profiling of Human Alzheimer’s Disease Brain, Serum and Cerebrospinal Fluid towards Potential Biomarker Discovery. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA - Gen. Subj. 2016, 1860, 1716–1727. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Karuppagounder, S.S.; Chen, Y.; Corona, C.; Kawaguchi, R.; Cheng, Y.; Balkaya, M.; Sagdullaev, B.T.; Wen, Z.; Stuart, C.; et al. 2-Deoxyglucose Drives Plasticity via an Adaptive ER Stress-ATF4 Pathway and Elicits Stroke Recovery and Alzheimer’s Resilience. Neuron 2023, 111, 2831-2846.e10. [CrossRef]

- Iordache, M.P.; Buliman, A.; Costea-Firan, C.; Gligore, T.C.I.; Cazacu, I.S.; Stoian, M.; Teoibaș-Şerban, D.; Blendea, C.-D.; Protosevici, M.G.-I.; Tanase, C.; et al. Immunological and Inflammatory Biomarkers in the Prognosis, Prevention, and Treatment of Ischemic Stroke: A Review of a Decade of Advancement. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7928. [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Martinez, I.; Martínez-Loustalot, P.; Lozano, L.; Issad, T.; Limón, D.; Díaz, A.; Perez-Torres, A.; Guevara, J.; Zenteno, E. Neuroinflammation Induced by Amyloid Β25–35 Modifies Mucin-Type O -Glycosylation in the Rat’s Hippocampus. Neuropeptides 2018, 67, 56–62. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yu, Q.; Yu, Q.; Johnson, J.; Shipman, R.; Zhong, X.; Huang, J.; Asthana, S.; Carlsson, C.; Okonkwo, O.; et al. In-Depth Site-Specific Analysis of N-Glycoproteome in Human Cerebrospinal Fluid and Glycosylation Landscape Changes in Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2021, 20, 100081. [CrossRef]

- Kobeissy, F.; Kobaisi, A.; Peng, W.; Barsa, C.; Goli, M.; Sibahi, A.; El Hayek, S.; Abdelhady, S.; Ali Haidar, M.; Sabra, M.; et al. Glycomic and Glycoproteomic Techniques in Neurodegenerative Disorders and Neurotrauma: Towards Personalized Markers. Cells 2022, 11, 581. [CrossRef]

- Schloss, J.V. Is Dolichol Pathway Dysfunction a Significant Factor in Alzheimer’s Disease? Inflammopharmacology 2025, 33, 4651–4658. [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-W.; Rust, N.; Wu, H.-F.; Hart, G. Altered O-GlcNAcylation and Mitochondrial Dysfunction, a Molecular Link between Brain Glucose Dysregulation and Sporadic Alzheimer’s Disease. Neural Regen. Res. 2023, 18, 779. [CrossRef]

- Medina, M.; Hernández, F.; Avila, J. New Features about Tau Function and Dysfunction. Biomolecules 2016, 6, 21. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ma, C.; Li, L.; Chin, L.-S. Differential Analysis of N-Glycopeptide Abundance and N-Glycosylation Site Occupancy for Studying Protein N-Glycosylation Dysregulation in Human Disease. BIO-Protoc. 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, M.; Ibrahim, M.; Alkorbi, N.; Alkuwari, S.; Pedersen, S.; Rathore, H.A. Epoxide Hydrolase Inhibitors for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Neurological Disorders: A Comprehensive Review. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2073. [CrossRef]

- Demirev, A.V.; Song, H.-L.; Cho, M.-H.; Cho, K.; Peak, J.-J.; Yoo, H.J.; Kim, D.-H.; Yoon, S.-Y. V232M Substitution Restricts a Distinct O-Glycosylation of PLD3 and Its Neuroprotective Function. Neurobiol. Dis. 2019, 129, 182–194. [CrossRef]

- Fang, P.; Yu, X.; Ding, M.; Qifei, C.; Jiang, H.; Shi, Q.; Zhao, W.; Zheng, W.; Li, Y.; Ling, Z.; et al. Ultradeep N-Glycoproteome Atlas of Mouse Reveals Spatiotemporal Signatures of Brain Aging and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 5568. [CrossRef]

- Gaunitz, S.; Tjernberg, L.O.; Schedin-Weiss, S. What Can N-Glycomics and N-Glycoproteomics of Cerebrospinal Fluid Tell Us about Alzheimer Disease? Biomolecules 2021, 11, 858. [CrossRef]

- Rajabally, Y.A. Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyneuropathy with Positive Anti-myelin Associated Glycoprotein Antibodies: Back to Clinical Basics. Eur. J. Neurol. 2023, 30, 301–302. [CrossRef]

- Frenkel-Pinter, M.; Stempler, S.; Tal-Mazaki, S.; Losev, Y.; Singh-Anand, A.; Escobar-Álvarez, D.; Lezmy, J.; Gazit, E.; Ruppin, E.; Segal, D. Altered Protein Glycosylation Predicts Alzheimer’s Disease and Modulates Its Pathology in Disease Model Drosophila. Neurobiol. Aging 2017, 56, 159–171. [CrossRef]

- Rusu, E.; Necula, L.G.; Neagu, A.I.; Alecu, M.; Stan, C.; Albulescu, R.; Tanase, C.P. Current Status of Stem Cell Therapy: Opportunities and Limitations. Turk. J. Biol. 2016, 40, 955–967. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W.; Shabbiri, K.; Ahmad, I. Prediction of Human Tau 3D Structure, and Interplay between O-β-GlcNAc and Phosphorylation Modifications in Alzheimer’s Disease: C. Elegans as a Suitable Model to Study These Interactions in Vivo. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 528, 466–472. [CrossRef]

- Meuret, C.J.; Hu, Y.; Smadi, S.; Bantugan, M.A.; Xian, H.; Martinez, A.E.; Krauss, R.M.; Ma, Q.-L.; Nedelkov, D.; Yassine, H.N. An Association of CSF Apolipoprotein E Glycosylation and Amyloid-Beta 42 in Individuals Who Carry the APOE4 Allele. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2023, 15, 96. [CrossRef]

- Popa, M.-L.; Popa, A.; Tanase, C.; Gheorghisan-Galateanu, A.-A. Acanthosis Nigricans: To Be or Not to Be Afraid (Review). Oncol. Lett. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Tena, J.; Tang, X.; Zhou, Q.; Harvey, D.; Barajas-Mendoza, M.; Jin, L.; Maezawa, I.; Zivkovic, A.M.; Lebrilla, C.B. Glycosylation Alterations in Serum of Alzheimer’s Disease Patients Show Widespread Changes in N -glycosylation of Proteins Related to Immune Function, Inflammation, and Lipoprotein Metabolism. Alzheimers Dement. Diagn. Assess. Dis. Monit. 2022, 14, e12309. [CrossRef]

- Alquezar, C.; Arya, S.; Kao, A.W. Tau Post-Translational Modifications: Dynamic Transformers of Tau Function, Degradation, and Aggregation. Front. Neurol. 2021, 11, 595532. [CrossRef]

- Ercan, E.; Eid, S.; Weber, C.; Kowalski, A.; Bichmann, M.; Behrendt, A.; Matthes, F.; Krauss, S.; Reinhardt, P.; Fulle, S.; et al. A Validated Antibody Panel for the Characterization of Tau Post-Translational Modifications. Mol. Neurodegener. 2017, 12, 87. [CrossRef]

- Thummel, R.; Li, L.; Tanase, C.; Sarras, M.P.; Godwin, A.R. Differences in Expression Pattern and Function between Zebrafish Hoxc13 Orthologs: Recruitment of Hoxc13b into an Early Embryonic Role. Dev. Biol. 2004, 274, 318–333. [CrossRef]

- Okła, E.; Hołota, M.; Michlewska, S.; Zawadzki, S.; Miłowska, K.; Sánchez-Nieves, J.; Gómez, R.; De La Mata, F.J.; Bryszewska, M.; Ionov, M. Crossing Barriers: PEGylated Gold Nanoparticles as Promising Delivery Vehicles for siRNA Delivery in Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2108. [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; He, C.; Abbasi, A.Z.; Tian, M.; Huang, S.; Wang, L.; Georgiou, J.; Collingridge, G.L.; Fraser, P.E.; Henderson, J.T.; et al. Brain Microenvironment-Remodeling Nanomedicine Improves Cerebral Glucose Metabolism, Mitochondrial Activity and Synaptic Function in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomaterials 2025, 318, 123142. [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Xu, K.; Xu, Z.; De Las Rivas, M.; Wang, C.; Li, X.; Lu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Delso, I.; Merino, P.; et al. The Small Molecule Luteolin Inhibits N-Acetyl-α-Galactosaminyltransferases and Reduces Mucin-Type O-Glycosylation of Amyloid Precursor Protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 21304–21319. [CrossRef]

- Bukke, V.N.; Villani, R.; Archana, M.; Wawrzyniak, A.; Balawender, K.; Orkisz, S.; Ferraro, L.; Serviddio, G.; Cassano, T. The Glucose Metabolic Pathway as A Potential Target for Therapeutics: Crucial Role of Glycosylation in Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7739. [CrossRef]

- Hoshi, K.; Ito, H.; Abe, E.; Fuwa, T.J.; Kanno, M.; Murakami, Y.; Abe, M.; Murakami, T.; Yoshihara, A.; Ugawa, Y.; et al. Transferrin Biosynthesized in the Brain Is a Novel Biomarker for Alzheimer’s Disease. Metabolites 2021, 11, 616. [CrossRef]

- Constantinoiu, S.; Cochior, D. Severe Acute Pancreatitis - Determinant Factors and Current Therapeutic Conduct. Chirurgia (Bucur.) 2018, 113, 385. [CrossRef]

- Pan, K.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y.; Yao, W.; Gao, X. MicroRNA-23b Attenuates Tau Pathology and Inhibits Oxidative Stress by Targeting GnT-III in Alzheimer’s Disease. Neuropharmacology 2021, 196, 108671. [CrossRef]

- Rosewood, T.J.; Nho, K.; Risacher, S.L.; Liu, S.; Gao, S.; Shen, L.; Foroud, T.; Saykin, A.J.; for the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Pathway Enrichment in Genome-wide Analysis of Longitudinal Alzheimer’s Disease Biomarker Endophenotypes. Alzheimers Dement. 2024, 20, 8639–8650. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Huang, H.; Xue, Y.; Chen, S.; Gao, X. DHEC Mesylate Attenuates Pathologies and Aberrant Bisecting N-Glycosylation in Alzheimer’s Disease Models. Neuropharmacology 2024, 248, 109863. [CrossRef]

- Finke, J.M.; Ayres, K.R.; Brisbin, R.P.; Hill, H.A.; Wing, E.E.; Banks, W.A. Antibody Blood-Brain Barrier Efflux Is Modulated by Glycan Modification. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA - Gen. Subj. 2017, 1861, 2228–2239. [CrossRef]

- Blendea, C.-D.; Khan, M.T.; Stoian, M.; Gligore, T.C.I.; Cuculici, Ștefan; Stanciu, I.L.; Protosevici, M.G.-I.; Iordache, M.; Buliman, A.; Costea-Firan, C.; et al. Advances in Minimally Invasive Treatments for Prostate Cancer: A Review of the Role of Ultrasound Therapy and Laser Therapy. Balneo PRM Res. J. 2025, 16, 827–827. [CrossRef]

- Gaunitz, S.; Tjernberg, L.O.; Schedin-Weiss, S. The N-glycan Profile in Cortex and Hippocampus Is Altered in Alzheimer Disease. J. Neurochem. 2021, 159, 292–304. [CrossRef]

- Nyarko, J.N.K.; Quartey, M.O.; Heistad, R.M.; Pennington, P.R.; Poon, L.J.; Knudsen, K.J.; Allonby, O.; El Zawily, A.M.; Freywald, A.; Rauw, G.; et al. Glycosylation States of Pre- and Post-Synaptic Markers of 5-HT Neurons Differ With Sex and 5-HTTLPR Genotype in Cortical Autopsy Samples. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 545. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Du, Y.; Huang, H.; Cao, Y.; Pan, K.; Zhou, Y.; He, J.; Yao, W.; Chen, S.; Gao, X. Targeting Aberrant Glycosylation to Modulate Microglial Response and Improve Cognition in Models of Alzheimer’s Disease. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 202, 107133. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, W.; Marcus, J.; Pearson, M.; Song, L.; Smith, K.; Terracina, G.; Lee, J.; Hong, K.-L.K.; Lu, S.X.; et al. MK-8719, a Novel and Selective O-GlcNAcase Inhibitor That Reduces the Formation of Pathological Tau and Ameliorates Neurodegeneration in a Mouse Model of Tauopathy. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2020, 374, 252–263. [CrossRef]

- Adnan, M.; Siddiqui, A.J.; Bardakci, F.; Surti, M.; Badraoui, R.; Patel, M. NEU1-Mediated Extracellular Vesicle Glycosylation in Alzheimer’s Disease: Mechanistic Insights into Intercellular Communication and Therapeutic Targeting. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 921. [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Su, Z.; Wang, S.; Meng, Y.; Xiao, F.; Xu, D.; Li, X.; Qian, X.; Lee, S.B.; Lee, J.; et al. EGFR-Induced and c-Src-Mediated CD47 Phosphorylation Inhibits TRIM21-Dependent Polyubiquitylation and Degradation of CD47 to Promote Tumor Immune Evasion. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10. [CrossRef]

- Barbu, L.A.; Vasile, L.; Cercelaru, L.; Șurlin, V.; Mogoantă, S.-Ștefaniță; Mogoș, G.F.R.; Țenea Cojan, T.S.; Mărgăritescu, N.-D.; Iordache, M.P.; Buliman, A. Aggressiveness in Well-Differentiated Small Intestinal Neuroendocrine Tumors: A Rare Case and Narrative Literature Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5821. [CrossRef]

- Tanase, C.; Enciu, A.M.; Codrici, E.; Popescu, I.D.; Dudau, M.; Dobri, A.M.; Pop, S.; Mihai, S.; Gheorghișan-Gălățeanu, A.-A.; Hinescu, M.E. Fatty Acids, CD36, Thrombospondin-1, and CD47 in Glioblastoma: Together and/or Separately? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 604. [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Shen, S.; Xu, Y.; Wang, L.; Feng, R.; Zhang, J.; Lu, H. Computational Studies on the Potency and Selectivity of PUGNAc Derivatives Against GH3, GH20, and GH84 β-N-Acetyl-D-Hexosaminidases. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 235. [CrossRef]

- Krüger, L.; Biskup, K.; Schipke, C.G.; Kochnowsky, B.; Schneider, L.-S.; Peters, O.; Blanchard, V. The Cerebrospinal Fluid Free-Glycans Hex1 and HexNAc1Hex1Neu5Ac1 as Potential Biomarkers of Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 512. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.Z.; Gaunitz, S.; Kirsebom, B.-E.; Lundin, B.; Hellström, M.; Jejcic, A.; Sköldunger, A.; Wimo, A.; Winblad, B.; Fladby, T.; et al. Blood N-Glycomics Reveals Individuals at Risk for Cognitive Decline and Alzheimer’s Disease. eBioMedicine 2025, 113, 105598. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.Z.; Vetrano, D.L.; Grande, G.; Duell, F.; Jönsson, L.; Laukka, E.J.; Fredolini, C.; Winblad, B.; Tjernberg, L.; Schedin-Weiss, S. A Glycan Epitope Correlates with Tau in Serum and Predicts Progression to Alzheimer’s Disease in Combination with APOE4 Allele Status. Alzheimers Dement. 2023, 19, 3244–3249. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.Z.; Duell, F.; Axenhus, M.; Jönsson, L.; Winblad, B.; Tjernberg, L.O.; Schedin-Weiss, S. A Glycan Biomarker Predicts Cognitive Decline in Amyloid- and Tau-Negative Patients. Brain Commun. 2024, 6, fcae371. [CrossRef]

- Chun, Y.S.; Kwon, O.-H.; Chung, S. O-GlcNAcylation of Amyloid-β Precursor Protein at Threonine 576 Residue Regulates Trafficking and Processing. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 490, 486–491. [CrossRef]

- Moldovan, C.; Cochior, D.; Gorecki, G.; Rusu, E.; Ungureanu, F.-D. Clinical and Surgical Algorithm for Managing Iatrogenic Bile Duct Injuries during Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy: A Multicenter Study. Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 22, 1385. [CrossRef]

- Fabiano, M.; Oikawa, N.; Kerksiek, A.; Furukawa, J.; Yagi, H.; Kato, K.; Schweizer, U.; Annaert, W.; Kang, J.; Shen, J.; et al. Presenilin Deficiency Results in Cellular Cholesterol Accumulation by Impairment of Protein Glycosylation and NPC1 Function. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5417. [CrossRef]

- Ohkawa, Y.; Kizuka, Y.; Takata, M.; Nakano, M.; Ito, E.; Mishra, S.; Akatsuka, H.; Harada, Y.; Taniguchi, N. Peptide Sequence Mapping around Bisecting GlcNAc-Bearing N-Glycans in Mouse Brain. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8579. [CrossRef]

- Cioffi, F.; Adam, R.H.I.; Broersen, K. Molecular Mechanisms and Genetics of Oxidative Stress in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2019, 72, 981–1017. [CrossRef]

- Reyes, C.D.G.; Hakim, Md.A.; Atashi, M.; Goli, M.; Gautam, S.; Wang, J.; Bennett, A.I.; Zhu, J.; Lubman, D.M.; Mechref, Y. LC-MS/MS Isomeric Profiling of N-Glycans Derived from Low-Abundant Serum Glycoproteins in Mild Cognitive Impairment Patients. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1657. [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Yi, L.; Fu, M.; Feng, Q.; Mao, X.; Mao, H.; Yan, Y.; Ding, C.-F. Anti-Nonspecific Hydrophilic Hydrogel for Efficient Capture of N-Glycopeptides from Alzheimer’s Disease Patient’s Serum. Talanta 2023, 253, 124068. [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Yang, Z.; Chen, X.; Li, W. The Significance of Sialylation on the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Brain Res. Bull. 2021, 173, 116–123. [CrossRef]

- Caramello, A.; Fancy, N.; Tournerie, C.; Eklund, M.; Chau, V.; Adair, E.; Papageorgopoulou, M.; Willumsen, N.; Jackson, J.S.; Hardy, J.; et al. Intracellular Accumulation of Amyloid-ß Is a Marker of Selective Neuronal Vulnerability in Alzheimer’s Disease. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 5189. [CrossRef]

- Didonna, A.; Benetti, F.; 1 Department of Neurology, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA 94158, USA Post-Translational Modifications in Neurodegeneration. AIMS Biophys. 2015, 3, 27–49. [CrossRef]

- Georgakis, M.K.; Gill, D.; Rannikmäe, K.; Traylor, M.; Anderson, C.D.; MEGASTROKE consortium of the International Stroke Genetics Consortium (ISGC); Lee, J.-M.; Kamatani, Y.; Hopewell, J.C.; Worrall, B.B.; et al. Genetically Determined Levels of Circulating Cytokines and Risk of Stroke: Role of Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1. Circulation 2019, 139, 256–268. [CrossRef]

- Cui, S.; Jin, Z.; Yu, T.; Guo, C.; He, Y.; Kan, Y.; Yan, L.; Wu, L. Effect of Glycosylation on the Enzymatic Degradation of D-Amino Acid-Containing Peptides. Molecules 2025, 30, 441. [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Tena, J.; Di Lucente, J.; Maezawa, I.; Harvey, D.J.; Jin, L.-W.; Lebrilla, C.B.; Zivkovic, A.M. Transcriptomic and Glycomic Analyses Highlight Pathway-Specific Glycosylation Alterations Unique to Alzheimer’s Disease. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7816. [CrossRef]

- Alkuhlani, A.; Gad, W.; Roushdy, M.; Salem, A.-B.M. PUStackNGly: Positive-Unlabeled and Stacking Learning for N-Linked Glycosylation Site Prediction. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 12702–12713. [CrossRef]

- Alkuhlani, A.; Gad, W.; Roushdy, M.; Voskoglou, M.Gr.; Salem, A.M. PTG-PLM: Predicting Post-Translational Glycosylation and Glycation Sites Using Protein Language Models and Deep Learning. Axioms 2022, 11, 469. [CrossRef]

- Lebart, M.-C.; Trousse, F.; Valette, G.; Torrent, J.; Denus, M.; Mestre-Frances, N.; Marcilhac, A. Reg-1α, a New Substrate of Calpain-2 Depending on Its Glycosylation Status. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8591. [CrossRef]

- Liang, N.; Nho, K.; Newman, J.W.; Arnold, M.; Huynh, K.; Meikle, P.J.; Borkowski, K.; Kaddurah-Daouk, R.; the Alzheimer’s Disease Metabolomics Consortium; Kueider-Paisley, A.; et al. Peripheral Inflammation Is Associated with Brain Atrophy and Cognitive Decline Linked to Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 17423. [CrossRef]

- Losev, Y.; Paul, A.; Frenkel-Pinter, M.; Abu-Hussein, M.; Khalaila, I.; Gazit, E.; Segal, D. Novel Model of Secreted Human Tau Protein Reveals the Impact of the Abnormal N-Glycosylation of Tau on Its Aggregation Propensity. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 2254. [CrossRef]

- Flowers, S.A.; Grant, O.C.; Woods, R.J.; Rebeck, G.W. O-Glycosylation on Cerebrospinal Fluid and Plasma Apolipoprotein E Differs in the Lipid-Binding Domain. Glycobiology 2020, 30, 74–85. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Meuret, C.; Go, S.; Yassine, H.N.; Nedelkov, D. Simple and Fast Assay for Apolipoprotein E Phenotyping and Glycotyping: Discovering Isoform-Specific Glycosylation in Plasma and Cerebrospinal Fluid. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2020, 76, 883–893. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lan, J.; Zhao, D.; Ruan, C.; Zhou, J.; Tan, H.; Bao, Y. Netrin-1 Upregulates GPX4 and Prevents Ferroptosis after Traumatic Brain Injury via the UNC5B/Nrf2 Signaling Pathway. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2023, 29, 216–227. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Yang, F.; Fan, J.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Chen, W.; Sun, H.; Ma, T.; Wang, Q.; Maihaiti, Y.; et al. Identification and Immune Characteristics of Molecular Subtypes Related to Protein Glycosylation in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 968190. [CrossRef]

- Kronimus, Y.; Albus, A.; Hasenberg, M.; Walkenfort, B.; Seifert, M.; Budeus, B.; Gronewold, J.; Hermann, D.M.; Ross, J.A.; Lochnit, G.; et al. Fc N-glycosylation of Autoreactive Aβ Antibodies as a Blood-based Biomarker for Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2023, 19, 5563–5572. [CrossRef]

- Lawler, P.E.; Bollinger, J.G.; Schindler, S.E.; Hodge, C.R.; Iglesias, N.J.; Krishnan, V.; Coulton, J.B.; Li, Y.; Holtzman, D.M.; Bateman, R.J. Apolipoprotein E O-Glycosylation Is Associated with Amyloid Plaques and APOE Genotype. Anal. Biochem. 2023, 672, 115156. [CrossRef]

- Ephrame, S.J.; Cork, G.K.; Marshall, V.; Johnston, M.A.; Shawa, J.; Alghusen, I.; Qiang, A.; Denson, A.R.; Carman, M.S.; Fedosyuk, H.; et al. O-GlcNAcylation Regulates Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase (ERK) Activation in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2023, 15, 1155630. [CrossRef]

- Pinho, T.S.; Correia, S.C.; Perry, G.; Ambrósio, A.F.; Moreira, P.I. Diminished O-GlcNAcylation in Alzheimer’s Disease Is Strongly Correlated with Mitochondrial Anomalies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA - Mol. Basis Dis. 2019, 1865, 2048–2059. [CrossRef]

- Frenkel-Pinter, M.; Shmueli, M.D.; Raz, C.; Yanku, M.; Zilberzwige, S.; Gazit, E.; Segal, D. Interplay between Protein Glycosylation Pathways in Alzheimer’s Disease. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1601576. [CrossRef]

- Boix, C.P.; Lopez-Font, I.; Cuchillo-Ibañez, I.; Sáez-Valero, J. Amyloid Precursor Protein Glycosylation Is Altered in the Brain of Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2020, 12, 96. [CrossRef]

- Haukedal, H.; Freude, K.K. Implications of Glycosylation in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 14, 625348. [CrossRef]

- Helmfors, L.; Boman, A.; Civitelli, L.; Nath, S.; Sandin, L.; Janefjord, C.; McCann, H.; Zetterberg, H.; Blennow, K.; Halliday, G.; et al. Protective Properties of Lysozyme on β-Amyloid Pathology: Implications for Alzheimer Disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2015, 83, 122–133. [CrossRef]

- Vela Navarro, N.; De Nadai Mundim, G.; Cudic, M. Implications of Mucin-Type O-Glycosylation in Alzheimer’s Disease. Molecules 2025, 30, 1895. [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, S.; Yu, Y. The Alteration and Role of Glycoconjugates in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2024, 16, 1398641. [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.; Huang, L.; Lei, F.; Li, T.; Luo, Y.; Zeng, M.; Wang, Z. The Role and Pathogenesis of Tau Protein in Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 824. [CrossRef]

- Nedelkov, D.; Tsokolas, Z.E.; Rodrigues, M.S.; Sible, I.; Han, S.D.; Kerman, B.E.; Renteln, M.; Mack, W.J.; Pascoal, T.A.; Yassine, H.N.; et al. Increased Cerebrospinal Fluid and Plasma apoE Glycosylation Is Associated with Reduced Levels of Alzheimer’s Disease Biomarkers. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2025, 17, 151. [CrossRef]

- Olejnik, B.; Ferens-Sieczkowska, M. Lectins and Neurodegeneration: A Glycobiologist’s Perspective. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2025, 34, 673–679. [CrossRef]

- Pająk, B.; Kania, E.; Orzechowski, A. Killing Me Softly: Connotations to Unfolded Protein Response and Oxidative Stress in Alzheimer’s Disease. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 1805304. [CrossRef]

- Pimenova, A.A.; Goate, A.M. Novel Presenilin 1 and 2 Double Knock-out Cell Line for in Vitro Validation of PSEN1 and PSEN2 Mutations. Neurobiol. Dis. 2020, 138, 104785. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, G.; Cao, L.; Chen, Y.-J. Novel Heterozygous Mutation in Alpha-2-Macroglobulin (A2M) Suppressing the Binding of Amyloid-β (Aβ). Front. Neurol. 2023, 13, 1090900. [CrossRef]

- Piscitelli, E.; Abeni, E.; Balbino, C.; Angeli, E.; Cocola, C.; Pelucchi, P.; Palizban, M.; Diaspro, A.; Götte, M.; Zucchi, I.; et al. Glycosylation Regulation by TMEM230 in Aging and Autoimmunity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2412. [CrossRef]

- Ercan-Herbst, E.; Ehrig, J.; Schöndorf, D.C.; Behrendt, A.; Klaus, B.; Gomez Ramos, B.; Prat Oriol, N.; Weber, C.; Ehrnhoefer, D.E. A Post-Translational Modification Signature Defines Changes in Soluble Tau Correlating with Oligomerization in Early Stage Alzheimer’s Disease Brain. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2019, 7, 192. [CrossRef]

- Nagae, M.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Taniguchi, N.; Kizuka, Y. 3D Structure and Function of Glycosyltransferases Involved in N-Glycan Maturation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 437. [CrossRef]

- Ramazi, S.; Dadzadi, M.; Darvazi, M.; Seddigh, N.; Allahverdi, A. Protein Modification in Neurodegenerative Diseases. MedComm 2024, 5, e674. [CrossRef]

- Saha, A.; Fernández-Tejada, A. Chemical Biology Tools to Interrogate the Roles of O-GlcNAc in Immunity. Front. Immunol. 2023, 13, 1089824. [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Ku, X.; Zou, X.; Hou, J.; Yan, W.; Zhang, Y. Comprehensive Analysis of O-Glycosylation of Amyloid Precursor Protein (APP) Using Targeted and Multi-Fragmentation MS Strategy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA - Gen. Subj. 2021, 1865, 129954. [CrossRef]

- Singh, Y.; Regmi, D.; Ormaza, D.; Ayyalasomayajula, R.; Vela, N.; Mundim, G.; Du, D.; Minond, D.; Cudic, M. Mucin-Type O-Glycosylation Proximal to β-Secretase Cleavage Site Affects APP Processing and Aggregation Fate. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 859822. [CrossRef]

- Suttapitugsakul, S.; Stavenhagen, K.; Donskaya, S.; Bennett, D.A.; Mealer, R.G.; Seyfried, N.T.; Cummings, R.D. Glycoproteomics Landscape of Asymptomatic and Symptomatic Human Alzheimer’s Disease Brain. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2022, 21, 100433. [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, N.; Ohkawa, Y.; Maeda, K.; Kanto, N.; Johnson, E.L.; Harada, Y. N-Glycan Branching Enzymes Involved in Cancer, Alzheimer’s Disease and COPD and Future Perspectives. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2022, 633, 68–71. [CrossRef]

- Tena, J.; Maezawa, I.; Barboza, M.; Wong, M.; Zhu, C.; Alvarez, M.R.; Jin, L.-W.; Zivkovic, A.M.; Lebrilla, C.B. Regio-Specific N-Glycome and N-Glycoproteome Map of the Elderly Human Brain With and Without Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2022, 21, 100427. [CrossRef]

- Urano, Y.; Takahachi, M.; Higashiura, R.; Fujiwara, H.; Funamoto, S.; Imai, S.; Futai, E.; Okuda, M.; Sugimoto, H.; Noguchi, N. Curcumin Derivative GT863 Inhibits Amyloid-Beta Production via Inhibition of Protein N-Glycosylation. Cells 2020, 9, 349. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Cheng, X.; Zeng, J.; Yuan, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, Y. LW-AFC Effects on N-Glycan Profile in Senescence-Accelerated Mouse Prone 8 Strain, a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Aging Dis. 2017, 8, 101. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Gopal, S.; Pocock, R.; Xiao, Z. Glycan Mimetics from Natural Products: New Therapeutic Opportunities for Neurodegenerative Disease. Molecules 2019, 24, 4604. [CrossRef]

- Wani, W.Y.; Chatham, J.C.; Darley-Usmar, V.; McMahon, L.L.; Zhang, J. O-GlcNAcylation and Neurodegeneration. Brain Res. Bull. 2017, 133, 80–87. [CrossRef]

- Weber, P.; Bojarová, P.; Brouzdová, J.; Křen, V.; Kulik, N.; Stütz, A.E.; Thonhofer, M.; Wrodnigg, T.M. Diaminocyclopentane – l-Lysine Adducts: Potent and Selective Inhibitors of Human O-GlcNAcase. Bioorganic Chem. 2024, 148, 107452. [CrossRef]

- Wheatley, E.G.; Albarran, E.; White, C.W.; Bieri, G.; Sanchez-Diaz, C.; Pratt, K.; Snethlage, C.E.; Ding, J.B.; Villeda, S.A. Neuronal O-GlcNAcylation Improves Cognitive Function in the Aged Mouse Brain. Curr. Biol. 2019, 29, 3359-3369.e4. [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Li, W.; Lu, H.; Li, L. Recent Advances in Mass Spectrometry-Based Studies of Post-Translational Modifications in Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2025, 24, 101003. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.-H.; Wen, R.; Yang, N.; Zhang, T.-N.; Liu, C.-F. Roles of Protein Post-Translational Modifications in Glucose and Lipid Metabolism: Mechanisms and Perspectives. Mol. Med. 2023, 29, 93. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Chen, T.; Zhao, H.; Ren, S. Glycosylation in Aging and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2024, 56, 1208–1220. [CrossRef]

- Reddy, V.P.; Aryal, P.; Darkwah, E.K. Advanced Glycation End Products in Health and Disease. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1848. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Lang, M. New Insight into Protein Glycosylation in the Development of Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell Death Discov. 2023, 9, 314. [CrossRef]

- Moll, T.; Shaw, P.J.; Cooper-Knock, J. Disrupted Glycosylation of Lipids and Proteins Is a Cause of Neurodegeneration. Brain 2020, 143, 1332–1340. [CrossRef]

- Pradeep, P.; Kang, H.; Lee, B. Glycosylation and Behavioral Symptoms in Neurological Disorders. Transl. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 154. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ma, C.; Chin, L.-S.; Pan, S.; Li, L. Human Brain Glycoform Coregulation Network and Glycan Modification Alterations in Alzheimer’s Disease. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadk6911. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ma, C.; Chin, L.-S.; Li, L. Integrative Glycoproteomics Reveals Protein N-Glycosylation Aberrations and Glycoproteomic Network Alterations in Alzheimer’s Disease. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabc5802. [CrossRef]

- Schreiner, T.G.; Menéndez-González, M.; Schreiner, O.D.; Ciobanu, R.C. Intrathecal Therapies for Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Review of Current Approaches and the Urgent Need for Advanced Delivery Systems. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2167. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Gu, Y.; Wan, B.; Ren, X.; Guo, L.-H. Label-Free Electrochemical Biosensing of Small-Molecule Inhibition on O-GlcNAc Glycosylation. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 95, 94–99. [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Van Husen, L.S.; Yu, Y.; Tjernberg, L.O.; Schedin-Weiss, S. Lack of N-Glycosylation Increases Amyloidogenic Processing of the Amyloid Precursor Protein. Glycobiology 2022, 32, 506–517. [CrossRef]

- Buliman, A.; Calin, M.A.; Iordache, M.P. Targeting Anxiety with Light: Mechanistic and Clinical Insights into Photobiomodulation Therapy: A Mini Narrative Review.

- Adam, R.; Moldovan, C.; Tudorache, S.; Hârșovescu, T.; Orban, C.; Pogărășteanu, M.; Rusu, E. Patellar Resurfacing in Total Knee Arthroplasty, a Never-Ending Controversy; Case Report and Literature Review. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 383. [CrossRef]

| Process / Target | Type of Glycosylation | Pathological Consequence | Biomarker / Therapeutic Relevance | Key References |

| Tau protein | N-glycosylation | Promotes hyperphosphorylation and aggregation | Detected in NFTs; biomarker potential | [12,82] |

| Tau protein | O-GlcNAcylation | Protective, reduces phosphorylation and aggregation | Reduced in AD brains; OGA inhibitors in trials | [20,59,68] |

| APP | N-glycosylation | Alters trafficking; increases amyloidogenic cleavage | Potential target for secretase regulation | [5,8,26] |

| BACE1 (β-secretase) | N-glycosylation | Stabilizes enzyme, promotes Aβ production | Inhibition reduces Aβ levels | [17,24,32,47,77,85] |

| Nicastrin (γ-secretase) | N-glycosylation | Modulates substrate binding and Aβ species ratio | Glycan-targeting therapies under exploration | [18,55,64,80] |

| Synaptic receptors (NMDA, AMPA) | N-glycosylation | Controls receptor trafficking and function | Aberrant glycosylation increases Aβ vulnerability | [38,61] |

| NCAM (adhesion) | Polysialylation | Regulates neurite outgrowth and synaptic plasticity | Reduced in AD hippocampus | [32,64,68] |

| Immune receptors (TREM2, CD33) | N-glycosylation | Controls stability and microglial response | Mutations affect AD risk | [27,59,67] |

| Cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α) | N-glycosylation | Regulates secretion and signaling | Altered profiles detected in CSF | [28,41] |

| Complement proteins (C1q, C3) | Sialylation | Regulates activation and synaptic pruning | Aberrant glycosylation enhances synapse loss | [9,12,54,60] |

| Enzymes (OGT, OGA) | Glycosylation enzymes | Balance O-GlcNAcylation/phosphorylation | Biomarker and therapeutic target | [83,88] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).