1. Introduction

The artificial intelligence industry has experienced explosive growth over the past five years, evolving from primarily research-focused organizations to commercially-oriented enterprises. As AI technologies mature and find broader applications across sectors, the nature of work within AI companies is undergoing significant transformation. While technical talent in machine learning and computer science remains foundational, a growing proportion of roles now encompasses non-technical functions essential for scaling, commercialization, and organizational effectiveness.

Understanding these workforce composition dynamics is crucial for several reasons. First, it provides insights into the maturation patterns of the AI industry and signals potential future trajectories. Second, it informs talent development strategies for both technical and non-technical workers seeking careers in AI. Third, it helps educational institutions align curricula with evolving industry needs. Finally, it assists investors and policymakers in understanding the changing nature of value creation in the AI economy.

This study investigates the changing workforce composition across diverse AI companies, focusing on three research questions:

How is workforce composition evolving across different segments of AI companies?

What non-technical roles are emerging as most critical in the contemporary AI industry?

What do these patterns suggest about the industry's maturation and future talent needs?

By analyzing detailed employment data from 19 AI companies spanning six industry segments, we identify significant patterns in workforce development and provide insights into the shifting balance of technical and non-technical roles in this rapidly evolving sector.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Industry Life Cycles and Organizational Development

The evolution of industries follows recognizable patterns, moving from embryonic to growth, maturity, and eventual decline phases (Klepper, 1997; Utterback & Abernathy, 1975). Each phase is characterized by distinct organizational structures, competitive dynamics, and workforce compositions. In embryonic and early growth phases, technical capabilities predominate as firms focus on product development and technical differentiation. As industries mature, complementary capabilities in marketing, sales, and operations become increasingly critical for commercial success (Teece, 1986).

Klepper's (1997) influential work on industry life cycles demonstrates how industries transition from periods of high entry, diverse products, and process innovation toward concentration, product standardization, and incremental innovation. This evolutionary pattern has significant implications for workforce composition, as early-stage product innovation requires different capabilities than later-stage process optimization and market expansion. Utterback and Abernathy (1975) further elucidate this relationship between innovation types and organizational capabilities, showing how the shift from product to process innovation necessitates corresponding changes in organizational structure and workforce composition.

Technology-intensive industries often display compressed life cycles, with rapid transitions between phases (Agarwal & Gort, 2002). The acceleration of industry evolution has been extensively documented in sectors like semiconductors (Brown & Linden, 2009), biotechnology (Pisano, 2006), and enterprise software (Cusumano, 2004), with each successive technology wave showing faster progression through developmental stages. Guzman and Stern (2020) demonstrate how entrepreneurial quality and quantity have evolved across technology sectors, showing the increasing speed of company growth and market penetration across successive technology waves.

The AI industry represents a particularly dynamic case, with substantial venture capital accelerating development timelines and compressing evolutionary stages that previously unfolded over decades into mere years. Cockburn et al. (2018) document how unprecedented capital investments in AI have accelerated both research breakthroughs and commercial applications, creating compressed industry development trajectories unlike previous technology waves.

2.2. Technical and Non-Technical Roles in Technology Organizations

Research on workforce composition in technology industries has highlighted the evolving relationship between technical and non-technical roles. Early-stage technology companies typically feature higher technical workforce concentrations, with minimal investment in sales, marketing, and operational infrastructure. As companies scale, non-technical functions grow disproportionately, often reaching or exceeding technical staff numbers during growth phases (Bresnahan et al., 2002).

Bresnahan, Brynjolfsson, and Hitt (2002) provide empirical evidence of how information technology adoption drives organizational changes, including shifts in workforce composition toward more non-routine cognitive tasks. Their firm-level analysis demonstrates that technology implementation requires complementary organizational innovations in processes, structures, and human capital deployment.

This transition reflects both organizational specialization and the growing importance of complementary assets in technology commercialization (Teece, 2018). Teece's framework of complementary assets explains why technical innovation alone is rarely sufficient for commercial success; companies must develop or access specialized capabilities in manufacturing, marketing, distribution, and customer support. As Teece (2018) argues in his updated work on profiting from innovation in the digital economy, the importance of complementary assets has only increased in platform-based technology industries, creating new imperatives for organizational development.

Cusumano's (2004) detailed study of software industry evolution shows how successful companies transitioned from product-focused organizations dominated by engineering talent toward more balanced structures incorporating substantial sales, marketing, and service functions. This evolution reflects both market maturation and the increasing complexity of enterprise technology deployment, which requires substantial customer-facing capabilities alongside technical expertise.

Empirical research by Tambe and Hitt (2012) on IT labor markets further demonstrates how technical and non-technical roles evolve in tandem, with changing skill requirements and workforce compositions reflecting broader industry dynamics. Their analysis of changing returns to different skill categories over time shows how the value of specific technical and non-technical capabilities shifts with technology cycles and market maturation.

Studies of previous technology waves, including enterprise software (Cusumano, 2004), cloud computing, and biotechnology, have documented similar patterns of technical-to-non-technical workforce evolution during industry maturation. This literature suggests an evolutionary pattern where early-stage companies emphasize technical capabilities, mid-stage growth companies build complementary commercial functions, and mature companies maintain balanced technical and non-technical workforces with increasing specialization in both domains.

2.3. AI Industry Development and Labor Market Transformations

The artificial intelligence sector represents a distinctive case in technology evolution due to several factors: the fundamental nature of its innovations, dual commercial and research orientations, and significant capital intensity (Brynjolfsson & McAfee, 2014; Webb, 2020). Initial AI organizations emerged primarily from research environments with heavy emphasis on technical talent. As commercial applications have expanded, organizational structures have evolved to accommodate broader functional requirements.

Brynjolfsson and McAfee's (2014) seminal work on the second machine age emphasizes how AI represents a general-purpose technology with broad applications across sectors, suggesting distinctive organizational requirements compared to more specialized technologies. Their analysis highlights how AI's expansive application potential creates unique challenges in organizational design, as companies must develop capabilities addressing diverse use cases and industry verticals.

Webb (2020) provides a detailed empirical analysis of how AI technologies are impacting occupational tasks and labor markets, identifying patterns of complementarity and substitution between AI capabilities and human skills. His research suggests that as AI systems mature, the nature of complementary human work evolves toward tasks requiring social intelligence, creativity, and contextual adaptation – capabilities often associated with non-technical roles.

Recent work by Acemoglu and Restrepo (2019) on automation and new tasks further elucidates how technological change creates both displacement and reinstatement effects in labor markets. Their framework helps explain the simultaneous growth of specialized technical AI roles and complementary non-technical functions within AI companies, as new technologies create novel task requirements alongside automation of existing work.

Research focused specifically on AI labor markets by Alekseeva et al. (2021) has documented the rapid diffusion of AI skills across occupations and industries, highlighting how AI capabilities are becoming embedded in diverse roles beyond core technical positions. Their findings suggest that the distinction between "AI workers" and "non-AI workers" is increasingly blurred, with AI-related skills becoming valuable across organizational functions.

Autor et al. (2020) provide comprehensive analysis of how technological change is reshaping work, emphasizing that emerging technologies create complementary roles alongside automation effects. Their research for MIT's Work of the Future initiative highlights how even advanced technologies like AI continue to require substantial human capabilities in design, implementation, oversight, and customer engagement, pointing to the continuing importance of diverse workforce capabilities.

Recent research has begun to document this transition, noting the emergence of specialized non-technical roles unique to AI companies (Acemoglu & Restrepo, 2019; Autor et al., 2020; Alekseeva et al., 2021). However, comprehensive analysis of workforce composition trends across different AI company segments remains limited, creating a gap this study addresses.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

This study utilizes workforce data collected through the GrauntX AI Talent Intelligence Platform, which aggregates employment information across technology companies. The dataset comprises detailed employment records for 19 AI companies spanning six industry segments, capturing job function distributions, growth trends, and organizational priorities from 2023 to 2025.

The GrauntX platform employs a multi-faceted data collection methodology combining automated and manual approaches. The system aggregates publicly available employment data from company websites, professional networks, job postings, and official company communications. This data is supplemented with information from regulatory filings, industry reports, and press releases to create comprehensive workforce profiles for each organization.

The data collection process employs machine learning algorithms for initial classification and categorization, followed by expert human validation to ensure accuracy and consistency. The platform tracks employment changes over time through regular data refreshes and comparative analysis, enabling the identification of growth trends, emerging roles, and functional shifts across companies and industry segments.

For this specific analysis, the data collection focused on employment records from January 2023 through February 2025, providing a 26-month window for examining workforce evolution. The dataset includes information on job titles, functional areas, reporting relationships, and employment duration, allowing for multi-dimensional analysis of organizational structures.

3.2. Sample Characteristics

The 19 companies in our sample represent major segments of the AI industry ecosystem:

Foundation Model Leaders (n=3): OpenAI, Anthropic, Mistral AI

Enterprise AI Platforms (n=4): Databricks, Scale, Hugging Face, Glean

Specialized AI Solutions (n=4): Cohere, Runway, ElevenLabs, Wayve

Defense & Hardware (n=3): Anduril Industries, Shield AI, Groq

Research & Scientific AI (n=1): Lila Sciences

AI Infrastructure (n=4): Anaconda, Together AI, Lambda, Harvey

These companies were selected based on several criteria to ensure a representative sample of the AI industry ecosystem:

Market Significance: Each company represents a significant player within its segment, either through market share, technological prominence, or investment valuation.

Developmental Diversity: The sample includes companies at different maturity stages, from early-growth organizations to established market leaders.

Business Model Variation: The selected companies encompass diverse business models, including research-oriented organizations, product companies, platform providers, and service-based enterprises.

Functional Breadth: Each company has sufficient organizational scale and complexity to allow meaningful analysis of functional distributions and workforce patterns.

The companies vary considerably in size and structure. Foundation Model Leaders range from approximately 500 to 1,500 employees, Enterprise AI Platforms from 600 to 3,000+ employees, and specialized solutions from 50 to 400 employees. This variation enables comparative analysis across different organizational scales while maintaining focus on companies with sufficient complexity for meaningful functional analysis.

The dataset includes information on approximately 15,000 employees across all companies, with over 600 distinct job titles grouped into 28 functional categories. This provides sufficient granularity for detailed functional analysis while maintaining cross-company comparability through standardized categorization.

3.3. Data Processing and Classification

The methodology employed a systematic approach to classification and analysis of workforce data. Job titles were initially classified using a machine learning algorithm trained on a comprehensive taxonomy of technology industry roles. This automated classification was then validated and refined through manual review by industry experts to ensure accuracy and consistency.

The functional classification system groups positions into 28 distinct categories across both technical and non-technical domains. Technical functions include Research and Science, Engineering, IT, Data Science, Quality Assurance, and specialized AI roles. Non-technical functions encompass Sales, Marketing, Business Development, Operations, Finance, Legal, Human Resources, Customer Success, and Strategy/Planning, among others.

To ensure temporal comparability, the dataset was structured to capture point-in-time employment snapshots at quarterly intervals from January 2023 through February 2025. This approach enables identification of growth trends, functional shifts, and emerging roles across the observation period while controlling for seasonal variations in hiring patterns.

For analysis of growth trends, we calculated both absolute and percentage changes in employment across functions and specific roles. To account for baseline effects in percentage calculations, we applied minimum thresholds for inclusion in growth analysis, typically requiring at least 5-10 employees in a category at the starting point to avoid overemphasizing small-number effects.

3.4. Analytical Framework

Our analysis employs both quantitative and qualitative approaches to examine workforce composition trends. We categorize roles into technical functions (including Research and Science, IT, Quality Assurance) and non-technical functions (including Sales, Marketing, Operations, Finance, HR). For each company and segment, we analyze:

Functional Distribution: Percentage of workforce in each functional area, calculated as the number of employees in each function divided by total company employment.

Growth Trends: Year-over-year changes in employment by function and role, measured as both absolute headcount changes and percentage growth rates.

Emerging Roles: Identification of fastest-growing job titles and categories, with particular attention to newly created positions and rapidly expanding functions.

Cross-Segment Patterns: Comparative analysis of workforce structures across industry segments, examining both commonalities and distinctive patterns.

Role Evolution: Analysis of how similar roles change in description, requirements, and organizational positioning over time.

The analytical framework incorporates both horizontal analysis (examining trends across companies and segments) and vertical analysis (examining functional distributions within individual organizations). This dual approach enables identification of both industry-level patterns and company-specific strategies.

For comparative analysis, we developed standardized metrics including technical-to-non-technical ratios, functional concentration indices (measuring the degree to which employment is concentrated in a few functions versus distributed across many), and growth dispersion indices (measuring whether growth is concentrated in a few functions or distributed across the organization).

This multi-dimensional analysis enables identification of both company-specific strategies and broader industry patterns in AI workforce evolution. By triangulating quantitative measures with qualitative assessment of organizational structures, we develop a comprehensive picture of how workforce composition is evolving across the AI industry.

4. Results

4.1. Overall AI Workforce Composition Patterns

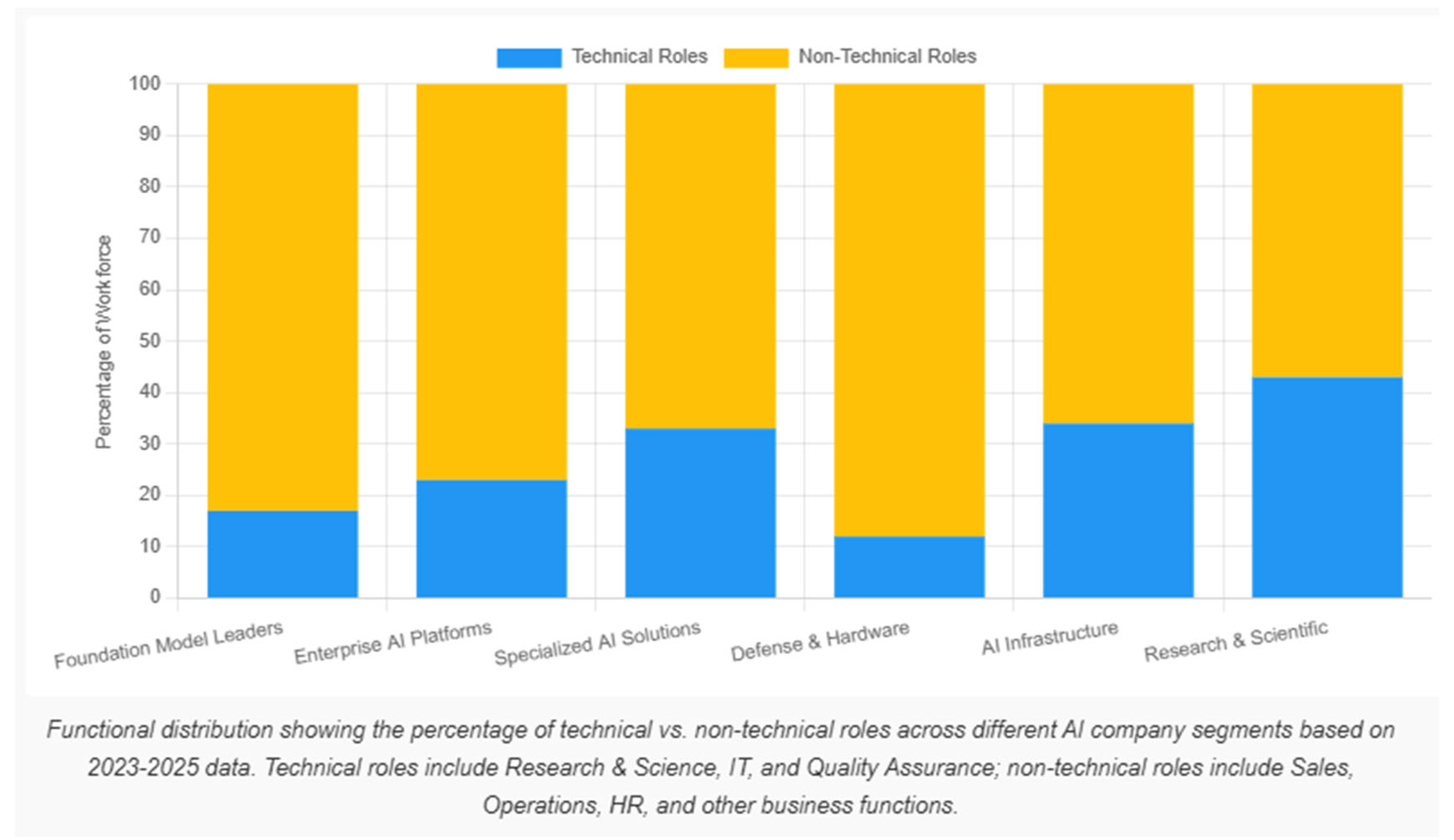

Our analysis reveals significant variation in workforce composition across AI company segments, reflecting different business models, maturity stages, and strategic priorities. To visualize these patterns,

Figure 1 presents the top functions across different AI company segments.

As shown in

Figure 1, Research and Science functions are most prominent in Foundation Model Leaders and Research & Scientific AI companies, while Sales functions dominate Enterprise AI Platforms. Specialized AI Solutions show more diverse functional distributions, reflecting their varied market applications.

The dataset reveals that while technical roles remain critical across all segments, their proportional representation varies considerably. Foundation Model Leaders maintain higher concentrations of research talent (Mistral AI: 27.64%, OpenAI: 6.57%, Anthropic: 4.77% in Research and Science), while Enterprise Platforms show stronger commercial orientations (Databricks: 21.26%, Glean: 28.72% in Sales).

4.2. Segment-Specific Workforce Composition

Table 1 presents a summary of the top functions for selected companies across different segments, highlighting distinct workforce composition patterns.

The data reveals distinct patterns across segments. Foundation Model Leaders maintain strong research orientations but are increasingly balanced by strategic and operational functions. Enterprise AI Platforms demonstrate mature go-to-market structures with dominant sales functions. Specialized AI Solutions show diverse functional priorities reflecting their specific market applications. Defense & Hardware companies emphasize operational and manufacturing capabilities essential to their product delivery.

4.3. Non-Technical Role Growth and Emerging Positions

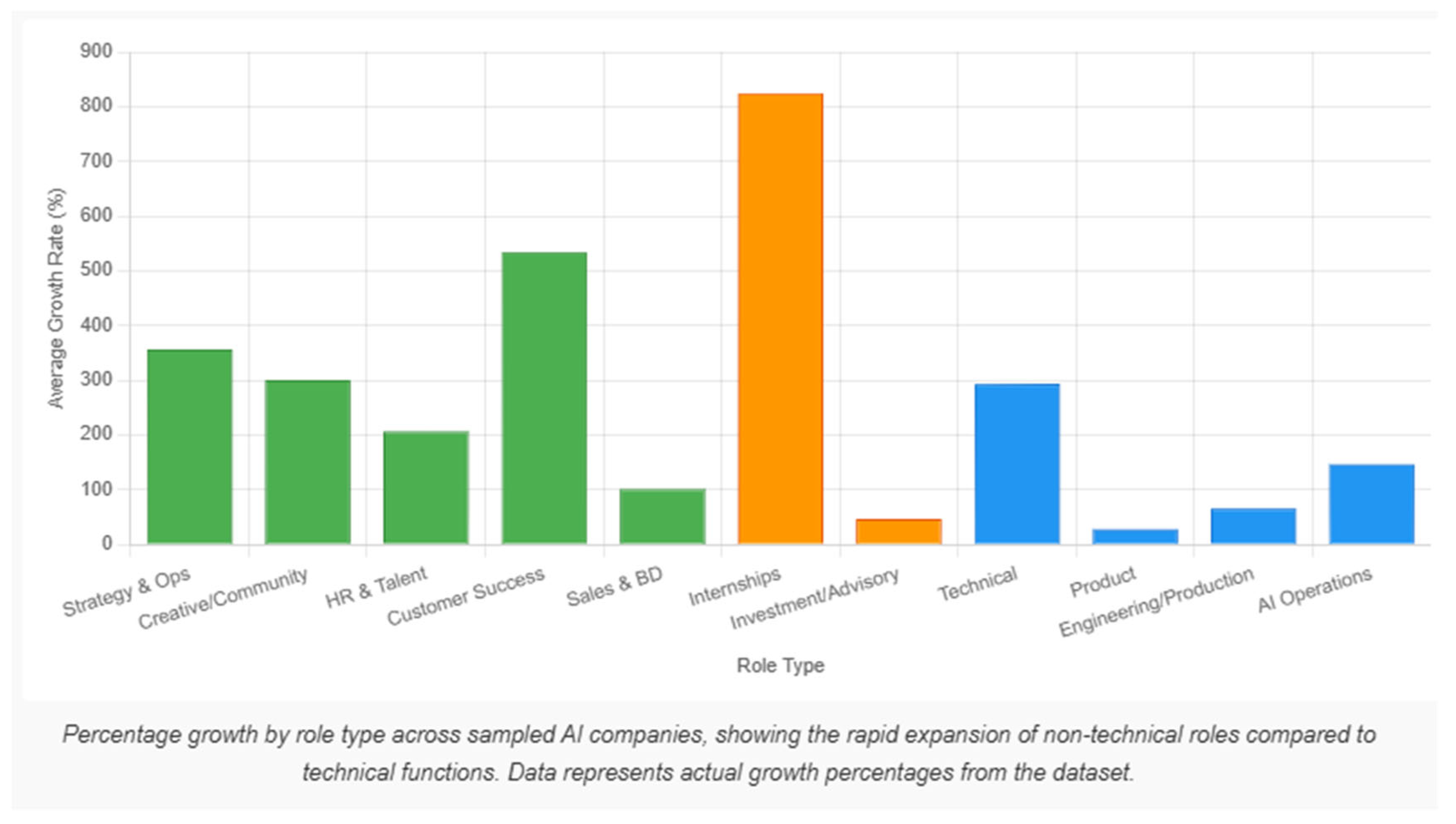

One of the most striking patterns in the data is the rapid growth of non-technical roles across AI companies.

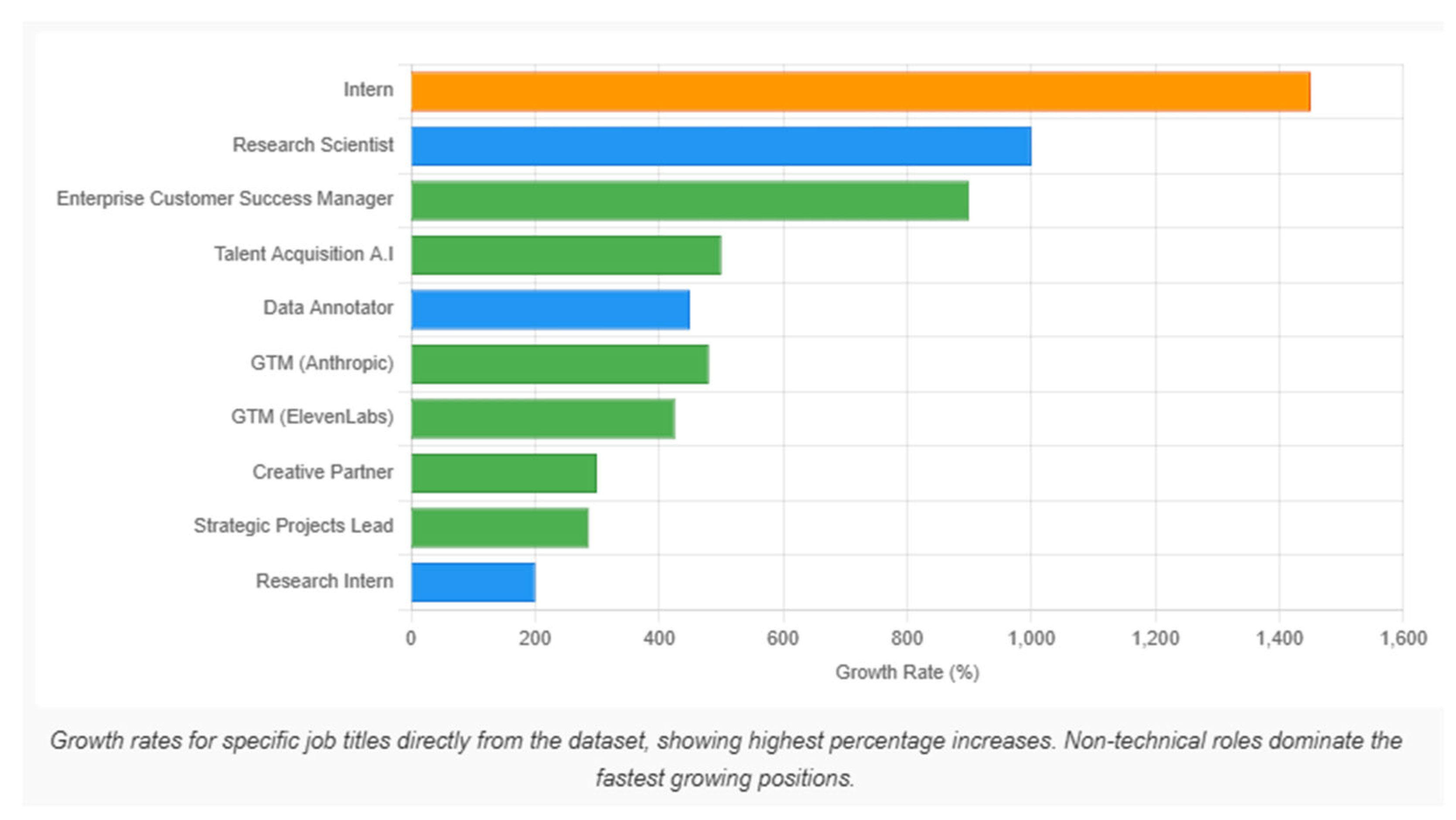

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 highlight the fastest-growing non-technical positions across selected companies.

As illustrated in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3, strategic and go-to-market functions are experiencing exceptional growth across multiple AI companies. Anthropic shows 480% growth in GTM roles, ElevenLabs demonstrates 425% growth in GTM positions, and Scale reports 286% growth in Strategic Projects Lead roles. These patterns suggest increasing organizational focus on commercialization and market execution.

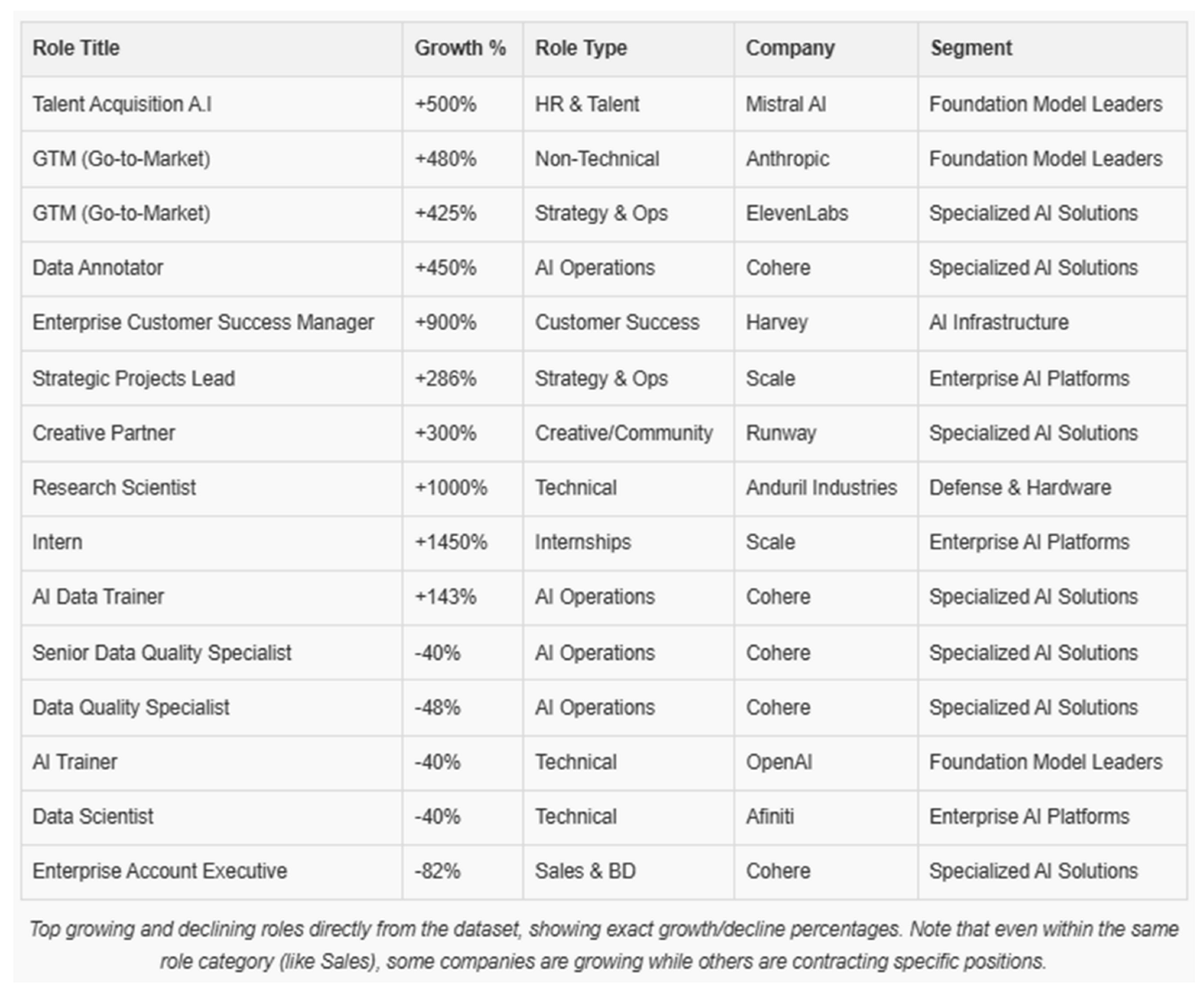

Table 2 provides additional detail on the fastest-growing roles across companies, highlighting both the role title and percentage growth.

The data shows considerable variation in growth priorities across companies, but with a clear emphasis on non-technical roles. Customer-facing positions (Account Executives, Customer Success Managers), strategic functions (GTM, Strategic Projects), and specialized community roles (Creative Partners, Forum Members) dominate the growth patterns.

4.4. Declining Roles and Function Shifts

In contrast to the growth in strategic and go-to-market functions, certain roles are experiencing decline across AI companies.

Table 3 highlights the roles with the largest percentage decreases.

The decline in technical operational roles such as AI Trainers, Data Quality Specialists, and certain product roles suggests a shift away from foundational data processing work toward more specialized and higher-value technical and non-technical functions. This pattern aligns with the maturation of AI technologies, where basic data processing becomes more automated or outsourced while specialized expertise becomes more valuable.

4.5. Detailed Analysis of Growing and Declining Roles

Our dataset reveals significant shifts in specific job roles across AI companies between 2023 and 2025, as illustrated in

Table 4. This detailed examination provides insights into which specific positions are experiencing dramatic growth or decline within the broader functional categories previously discussed.

Several patterns emerge from this granular analysis. First, we observe extraordinary growth in talent acquisition and HR functions, with Mistral AI expanding their Talent Acquisition AI role by 500%. This aligns with the overall surge in non-technical functions seen in

Figure 2, but reveals the specific emphasis companies are placing on specialized recruitment capabilities tailored to AI organizations.

Go-to-market (GTM) roles show remarkable growth across different company segments, with Anthropic and ElevenLabs increasing these positions by 480% and 425% respectively. This indicates a shift toward commercialization across both Foundation Model Leaders and Specialized AI Solutions segments as companies transition from research-focused activities to market-facing operations.

Customer success functions are expanding rapidly, particularly in AI Infrastructure companies like Harvey, where Enterprise Customer Success Manager roles grew by 900%. This suggests growing attention to client satisfaction and retention as AI products mature and reach broader market adoption.

Notably, the roles experiencing the most dramatic growth are predominantly non-technical, supporting our earlier findings about the evolving composition of AI companies. However, there are exceptions—Research Scientist positions at Anduril Industries (Defense & Hardware segment) increased by 1000%, demonstrating that even in segments with traditionally lower research emphasis, technical talent acquisition remains strategic in specific companies.

The decline in certain technical positions provides further evidence of workforce evolution. Roles such as AI Trainer at OpenAI (-40%) and Data Scientist at Afiniti (-40%) show meaningful reductions. This may reflect efficiency gains, automation of certain technical functions, or strategic reprioritization.

Most interestingly, we see opposing trends within similar role categories across different companies. While Enterprise Customer Success Manager positions grew dramatically at Harvey, Enterprise Account Executive roles declined by 82% at Cohere. This suggests that workforce composition changes are not uniform across the industry but rather reflect company-specific strategic directions and maturity stages.

Data quality and annotation roles show mixed trends—Data Annotator positions grew by 450% at Cohere while Data Quality Specialist positions declined by 48% at the same company. This apparent contradiction highlights the nuanced evolution occurring within AI operations, potentially reflecting shifts toward different data quality methodologies or changing priorities in how companies approach training data management.

Table 4 provides concrete evidence supporting our broader findings while revealing the complex, company-specific nature of workforce evolution in the AI industry. These detailed examples demonstrate that while overall trends favor growth in non-technical functions, individual companies are making strategic staffing decisions based on their unique market positions, growth stages, and business models.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

Our findings provide several important insights for understanding industry evolution and organizational development in technology-intensive sectors.

First, the results support theoretical models of industry life cycles (Klepper, 1997; Utterback & Abernathy, 1975) while highlighting the accelerated timeline of evolution in the AI industry. Foundation model companies have rapidly progressed from research-focused organizations to commercially-oriented enterprises in just 3-5 years, a transition that took decades in previous technology waves. This compressed evolution suggests that complementary assets (Teece, 1986) become crucial earlier in AI companies' development compared to historical technology industries.

The acceleration of organizational development in AI companies appears driven by several factors: (1) unprecedented capital availability reducing resource constraints, (2) established organizational templates from previous technology waves providing proven structures, (3) competitive pressures requiring rapid commercial deployment, and (4) the inherent general-purpose nature of AI technology necessitating diverse application capabilities. This compressed evolutionary pattern has significant implications for organizational theory, suggesting that traditional staged models of organizational development may require modification for hyper-accelerated technology sectors.

Second, our findings illustrate the dynamic relationship between technical and non-technical roles during industry maturation. Rather than a simple linear progression from technical to non-technical dominance, we observe complex patterns of functional specialization, with technical roles evolving toward more applied and customer-oriented positions while new specialized non-technical roles emerge to bridge technical capabilities with market applications. This aligns with Bresnahan et al.'s (2002) findings on the complementary nature of technical innovation and organizational change, while demonstrating more complex evolutionary patterns than simple technical-to-commercial transitions.

The emergence of hybrid roles that span traditional technical and non-technical boundaries – such as AI product managers, technical customer success specialists, and AI strategy consultants – suggests that the traditional dichotomy between technical and non-technical functions may be insufficient for understanding workforce evolution in AI companies. Instead, we observe the development of specialized roles that integrate technical understanding with commercial, operational, or strategic capabilities. This pattern aligns with recent literature on T-shaped skills (Hansen, 2010) and hybrid competencies in technology industries.

Third, the segment-specific patterns demonstrate how different business models within the same industry require distinct workforce configurations. This supports contingency theories of organizational design (Lawrence & Lorsch, 1967), showing how workforce composition aligns with strategic positioning within the industry value chain. The distinctive workforce profiles of foundation model providers, enterprise platforms, specialized solutions providers, and infrastructure companies demonstrate how organizational structures evolve to support specific value propositions and market positions.

These segment-specific patterns suggest that there is no universal "optimal" workforce configuration for AI companies. Rather, effective organizational design appears contingent on business model, market position, technology focus, and development stage. This aligns with Lawrence and Lorsch's (1967) foundational work on contingency theory, which emphasizes that effective organizational structures must fit both environmental demands and internal strategic requirements.

Each segment demonstrates distinctive functional emphases reflecting their strategic positioning in the AI value chain. Foundation Model Leaders balance research with growing commercial functions, Enterprise Platforms emphasize sales and customer engagement, and Specialized Solutions show diverse configurations aligned with their specific market applications.

The data also suggests important refinements to theories of organizational evolution in technology industries. While prior research has often emphasized a linear progression from technical to commercial dominance, our findings reveal more nuanced patterns where (1) technical roles evolve rather than diminish, shifting toward more specialized and applied functions; (2) new hybrid roles emerge that bridge traditional functional boundaries; and (3) segment-specific evolutionary patterns reflect distinct value propositions and market positions.

5.2. Practical Implications

5.2.1. Implications for AI Companies

For AI company leadership, our findings highlight the strategic importance of building non-technical capabilities alongside technical excellence. As the industry matures, competitive advantage increasingly derives from complementary organizational capabilities rather than technical innovation alone. Companies should proactively develop specialized non-technical functions, particularly in strategic operations, go-to-market execution, and customer success.

The rapid growth in strategic and go-to-market functions across multiple segments suggests that companies may face first-mover advantages in securing specialized talent in these areas. Organizations should develop comprehensive talent strategies that address both technical and non-technical capabilities, with particular attention to emerging hybrid roles that combine technical understanding with commercial, operational, or strategic skills. Developing internal talent pipelines that enable technical employees to transition into hybrid or non-technical roles may prove particularly valuable given the scarcity of experienced professionals in these specialized areas.

Our segment analysis suggests that companies should tailor their organizational development to their specific business model and market position rather than following generic industry patterns. Foundation Model Leaders require balanced investments in research excellence and commercial capabilities, Enterprise Platforms need robust sales and customer success functions, and Specialized Solutions providers benefit from focused customer engagement capabilities specific to their application domains.

The data also suggests potential talent bottlenecks in rapidly growing specialized roles such as AI-focused strategic operations, technical sales, and AI product management. Companies should develop internal talent pipelines and targeted recruitment strategies for these emerging positions. Organizational initiatives that facilitate knowledge sharing between technical and non-technical functions may help develop the hybrid capabilities that appear increasingly valuable as the industry matures.

5.2.2. Implications for Education and Workforce Development

Educational institutions preparing students for AI careers should recognize the growing importance of non-technical roles in the industry. While technical AI education remains essential, curricula should incorporate complementary skills in product management, operations, and go-to-market strategy. Interdisciplinary programs combining technical foundations with business and operational capabilities may be particularly valuable.

The emergence of specialized hybrid roles suggests potential for new educational approaches that integrate technical and non-technical domains. Programs focusing on AI product management, AI business strategy, or AI operations could address growing industry demand for professionals who can bridge technical and business domains. Such programs might combine core technical curriculum (sufficient for understanding AI capabilities and limitations) with specialized training in commercial, operational, or strategic applications.

Professional development programs for mid-career professionals could focus on transition paths from purely technical roles to hybrid positions, or from traditional business functions to AI-specific commercial roles. Such programs could help address talent shortages in rapidly growing specialized positions while providing career advancement opportunities for existing professionals.

Workforce development initiatives should similarly recognize the diverse career paths emerging in AI beyond traditional technical roles. Programs developing "technical translators" – professionals who can bridge technical and business domains – appear especially aligned with industry needs. Community colleges and vocational training institutions could develop targeted programs for specific emerging non-technical roles, such as AI operations specialists, AI compliance managers, or AI application consultants.

5.2.3. Implications for Policy and Economic Development

Policymakers concerned with AI economic development should note that the industry creates diverse employment opportunities beyond technical roles. Workforce development policies overly focused on technical AI skills may miss significant job creation in complementary functions. A balanced approach supporting both technical and non-technical talent development better aligns with the industry's actual needs.

The data suggests that AI industry development creates employment demand across multiple skill levels and educational backgrounds, not just for highly specialized technical experts. This has important implications for inclusive economic development strategies, as it suggests broader workforce participation possibilities than are often recognized in policy discussions of AI industry growth.

Regional economic development initiatives should consider how to develop comprehensive AI ecosystems that include not only research and development capabilities but also complementary business services, specialized recruitment and training programs, and supportive professional networks. The diversity of roles emerging in AI companies suggests that regions can develop distinctive specializations aligned with their existing workforce strengths rather than competing solely on technical talent development.

The acceleration of organizational development in AI companies also has implications for policy timelines. Traditional workforce development initiatives often operate on multi-year planning cycles, which may be insufficient for addressing rapidly evolving skill needs in the AI sector. More agile approaches to workforce development, perhaps involving closer industry-education partnerships and rapid curriculum adaptation, may better serve this fast-moving industry.

5.3. Future Research Directions

This study identifies several promising avenues for future research:

Longitudinal Studies: Tracking workforce composition changes over longer time periods would provide deeper insights into industry maturation patterns. Following companies from founding through multiple developmental stages could reveal how workforce configurations evolve at different growth phases and in response to changing market conditions. Longitudinal studies could also examine how founding team composition influences subsequent organizational development and functional emphasis.

Performance Linkages: Investigating relationships between workforce composition and company performance metrics would illuminate optimal organizational structures. Research might examine how the timing and sequencing of investments in different functional capabilities affects growth trajectories, customer acquisition, and profitability. Of particular interest would be understanding how the balance between technical and non-technical investments affects innovation output, market penetration, and financial performance at different organizational stages.

International Comparisons: Examining how workforce patterns differ across geographic regions could reveal cultural and institutional influences on AI company development. Comparing workforce composition in AI companies based in North America, Europe, and Asia might identify distinctive regional approaches to organizational design and development. Such research could examine how national innovation systems, educational institutions, and labor market structures influence the evolution of AI organizations.

Career Path Analysis: Studying individual career progressions within and across AI companies would enhance understanding of skill development and career mobility patterns. Research tracking how professionals move between technical and non-technical roles, between companies at different developmental stages, or between industry segments would provide valuable insights for both individual career planning and organizational talent strategies. Such research might identify common transition paths, required skill development, and career progression timelines.

Role Evolution Studies: Detailed analysis of how specific roles evolve in responsibilities, required qualifications, and organizational positioning could provide deeper insights into functional specialization patterns. Examining how roles like "AI product manager" or "AI ethicist" have evolved in job descriptions, reporting relationships, and organizational influence would enhance understanding of emerging specialized functions in AI companies.

Acquisition Impact Analysis: Investigating how acquisitions affect workforce composition and organizational structure would illuminate an important mechanism of capability development in the AI industry. Research might examine how acquiring companies integrate technical and non-technical talent from acquired organizations and how these integration patterns affect subsequent organizational development.

6. Limitations

Several limitations should be acknowledged in interpreting our findings. First, our sample, while representative, is not comprehensive of all AI companies. The focus on 19 prominent companies across six segments provides valuable insights into major industry patterns but may miss distinctive organizational forms in very early-stage startups, smaller specialized firms, or companies in adjacent technology sectors incorporating AI capabilities.

Second, job titles and functions are not perfectly standardized across organizations, creating some classification challenges. While our methodology employs both automated and manual validation to ensure consistent categorization, there remains inherent ambiguity in how companies define and structure roles. This is particularly challenging for emerging hybrid positions that span traditional functional boundaries, which may be classified differently across organizations despite similar responsibilities.

Third, our cross-sectional approach provides limited insights into causal relationships. While we identify correlations between company segments, developmental stages, and workforce compositions, determining causal direction requires additional research. Longitudinal studies tracking companies from formation through multiple developmental stages would provide stronger evidence of causal mechanisms in organizational evolution.

Fourth, our data primarily reflects larger, better-funded AI companies, potentially missing patterns in early-stage startups or smaller specialized firms. This focus on established organizations with substantial workforces provides valuable insights into maturation patterns but may underrepresent innovative organizational forms emerging in newer ventures. The capital-intensive nature of contemporary AI development means that even "small" AI companies in our sample have significant resources compared to typical technology startups.

Fifth, the rapid evolution of the AI industry means that patterns identified in our 2023-2025 observation window may not persist in future periods. The industry remains highly dynamic, with ongoing technological developments, regulatory changes, and market shifts potentially driving new organizational adaptations. Continuous monitoring and periodic reassessment will be essential for validating whether the patterns we identify represent enduring industry characteristics or transitional phenomena.

Sixth, our analysis focuses primarily on formal organizational structures as reflected in job titles and functional categorizations. This approach captures important aspects of organizational design but may miss informal structures, cross-functional collaborations, and evolving work practices not reflected in official organizational charts. Complementary qualitative research examining how work is actually conducted within AI companies would provide additional insights beyond formal structural analysis.

Finally, our analysis examines patterns at the company and segment levels, with limited ability to control for potentially confounding variables like company age, funding level, geographic location, or founder background. While we consider these factors in our qualitative interpretation, more rigorous statistical analysis controlling for multiple variables would be valuable for isolating specific drivers of workforce composition patterns.

7. Conclusions

The artificial intelligence industry is undergoing a significant transition from technical experimentation to commercial maturation, reflected in evolving workforce compositions across company segments. While technical expertise remains foundational, non-technical functions in strategy, operations, and go-to-market execution are increasingly critical for organizational success.

The patterns revealed in this study demonstrate that AI companies follow compressed evolutionary trajectories compared to previous technology waves, rapidly developing diverse functional capabilities to commercialize their technical innovations. This acceleration presents both challenges and opportunities – enabling faster market development but requiring proactive organizational design and talent strategies.

Our analysis shows distinctive workforce configurations across industry segments, with Foundation Model Leaders balancing research excellence and commercial capabilities, Enterprise Platforms emphasizing customer engagement and solution delivery, and Specialized Solutions developing focused capabilities aligned with specific application domains. These segment-specific patterns highlight how organizational structures evolve to support particular business models and market positions rather than following a universal template.

The rapid growth of strategic, operational, and go-to-market functions across multiple segments signals a fundamental shift in how value is created and captured in the AI industry. While technical innovation remains essential, the ability to effectively commercialize, implement, and scale AI solutions increasingly differentiates successful companies. This suggests that competitive advantage in AI is becoming more multidimensional, requiring excellence across technical, commercial, and operational domains.

The emergence of specialized hybrid roles bridging technical and non-technical functions represents a particularly important development. These positions – including AI product managers, AI ethicists, and AI strategy consultants – enable organizations to more effectively translate technical capabilities into business value. The growing prevalence of these roles suggests that the traditional dichotomy between technical and non-technical functions is insufficient for understanding workforce evolution in AI companies.

For individuals pursuing careers in AI, our findings highlight the diverse pathways available beyond traditional technical roles. While deep technical expertise remains highly valued, there are expanding opportunities for professionals who can bridge technical understanding with commercial, operational, or strategic capabilities. This suggests potential for broader participation in the AI economy across diverse educational backgrounds and skill sets.

For educational institutions and workforce development programs, our results underscore the importance of developing multifaceted capabilities that span traditional domain boundaries. Programs that combine technical foundations with business, operational, or domain-specific knowledge appear particularly well-aligned with emerging industry needs. The rapid evolution of the industry also suggests value in more agile, continuous learning approaches rather than static degree programs.

The patterns revealed in this study suggest that as AI technologies mature, competitive advantage increasingly derives from complementary organizational capabilities rather than technical innovation alone. Organizations that proactively develop balanced capabilities across technical and non-technical domains will be better positioned to translate technical potential into market success. This has profound implications for AI company strategy, talent development, and educational preparation.

Future research should continue to monitor these evolving workforce dynamics to enhance our understanding of AI industry development and inform effective organizational design for technology-intensive enterprises. As the industry continues to mature and differentiate, more granular analysis of segment-specific patterns, role evolution, and performance linkages will provide valuable insights for both theory development and practical application.

References

- Acemoglu, D. , & Restrepo, P. (2019). Automation and new tasks: How technology displaces and reinstates labor. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33(2), 3-30.

- Agarwal, R., & Gort, M. (2002). Firm and product life cycles and firm survival. American Economic Review, 92(2), 184-190.

- Alekseeva, L., Azar, J., Gine, M., Samila, S., & Taska, B. (2021). The demand for AI skills in the labor market. Labour Economics, 71, 102002.

- Autor, D. , Mindell, D., & Reynolds, E. (2020). The work of the future: Building better jobs in an age of intelligent machines. MIT Work of the Future.

- Bresnahan, T. F. , Brynjolfsson, E., & Hitt, L. M. (2002). Information technology, workplace organization, and the demand for skilled labor: Firm-level evidence. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(1), 339-376.

- Brown, C. , & Linden, G. (2009). Chips and change: How crisis reshapes the semiconductor industry. MIT Press.

- Brynjolfsson, E. , & McAfee, A. (2014). The second machine age: Work, progress, and prosperity in a time of brilliant technologies. W.W. Norton & Company.

- Cockburn, I. M. , Henderson, R., & Stern, S. (2018). The impact of artificial intelligence on innovation: An exploratory analysis. In The Economics of Artificial Intelligence: An Agenda (pp. 115-146). University of Chicago Press.

- Cusumano, M. A. (2004). The business of software: What every manager, programmer, and entrepreneur must know to thrive and survive in good times and bad. Free Press.

- Guzman, J. , & Stern, S. (2020). The state of American entrepreneurship: New estimates of the quantity and quality of entrepreneurship for 32 US states, 1988-2014. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 12(4), 212-43.

- Hansen, M. T. (2010). IDEO CEO Tim Brown: T-shaped stars: The backbone of IDEO's collaborative culture. Chief Executive, 21.

- Klepper, S. (1997). Industry life cycles. Industrial and Corporate Change, 6(1), 145-182.

- Lawrence, P. R. , & Lorsch, J. W. (1967). Organization and environment: Managing differentiation and integration. Harvard Business School Press.

- Pisano, G. P. (2006). Science business: The promise, the reality, and the future of biotech. Harvard Business Press.

- Tambe, P. , & Hitt, L. M. (2012). The productivity of information technology investments: New evidence from IT labor data. Information Systems Research, 23(3-part-1), 599-617.

- Teece, D. J. (1986). Profiting from technological innovation: Implications for integration, collaboration, licensing and public policy. Research Policy, 15(6), 285-305.

- Teece, D. J. (2018). Profiting from innovation in the digital economy: Enabling technologies, standards, and licensing models in the wireless world. Research Policy, 47(8), 1367-1387.

- Utterback, J. M., & Abernathy, W. J. (1975). A dynamic model of process and product innovation. Omega, 3(6), 639-656.

- Webb, M. (2020). The impact of artificial intelligence on the labor market. Stanford Digital Economy Lab Working Paper.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).