Submitted:

16 October 2025

Posted:

21 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

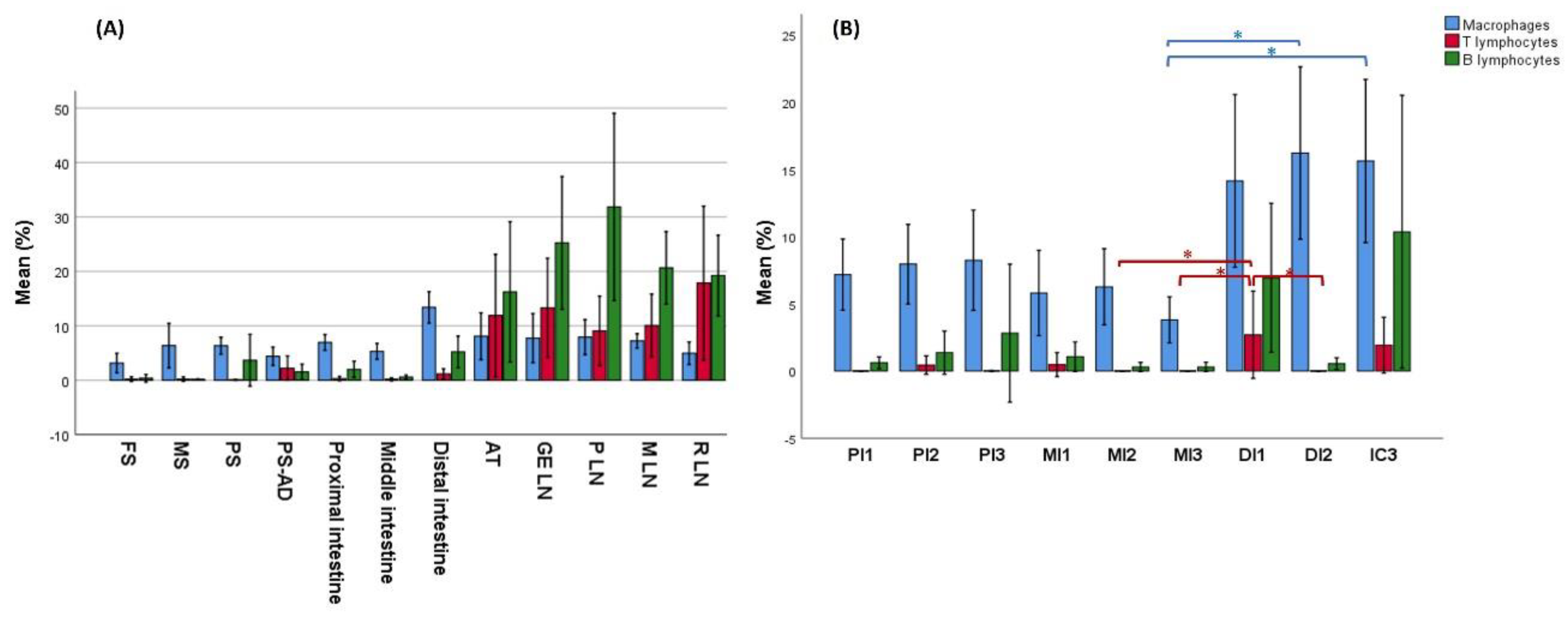

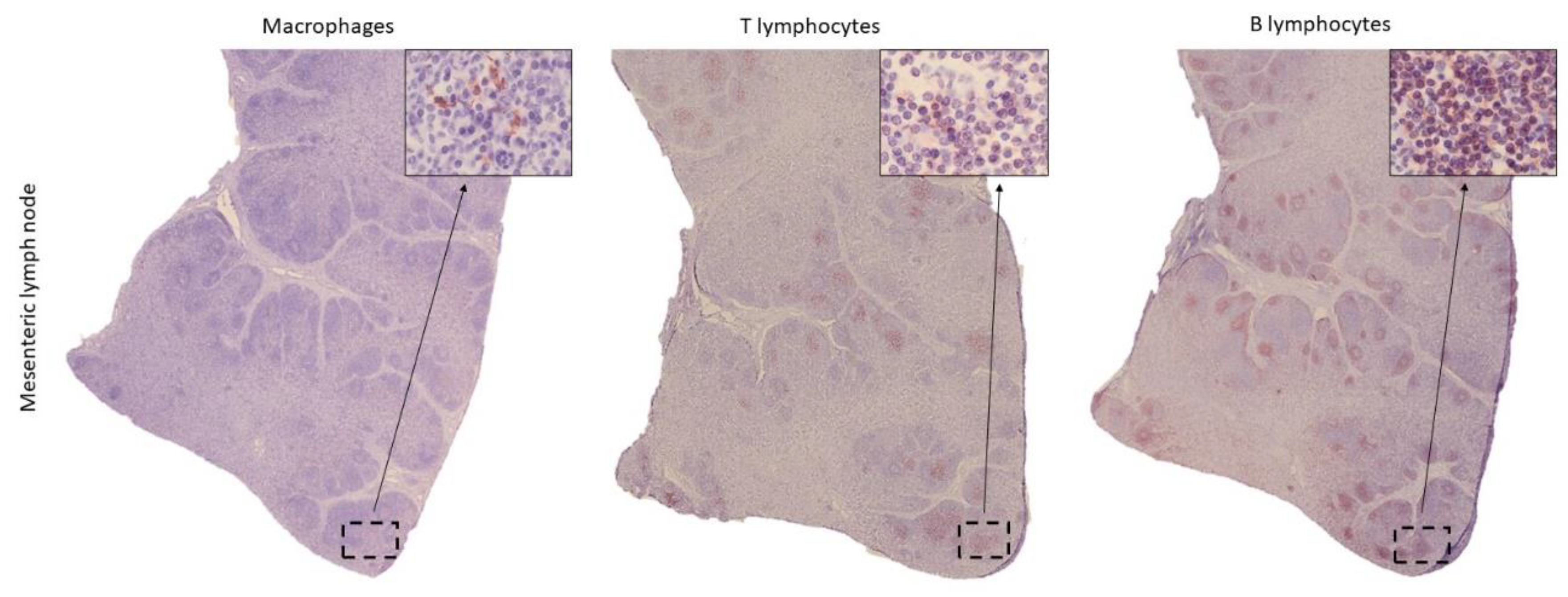

The current knowledge on the histological structure of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) in cetaceans is based on general descriptions, which do not reflect the diversity of these marine mammals. The aim of this study was to characterize the histology and expression of immune cell markers in samples from the GIT and lymph nodes (LNs) in a harbour porpoise (Phocoena phocoena), which died due to bycatch in the Bay of Biscay, Cantabrian Sea. After hematoxylin-eosin and Masson's trichrome staining, the thickness of the histological layers of the GIT was measured, being greater in the stomachs and anal canal, although no significant differences were found among any intestinal segment (p = 0.448). LNs exhibited a well-differentiated cortical region, containing lymphoid follicles, and a medullary area. In addition, immunohistochemical techniques were performed to identify the following markers: IBA1 for macrophages, CD3 for T lymphocytes, and CD20 for B lymphocytes. The distribution of immune cells varied significantly along the GIT, with higher percentages of all three cell types in the distal intestine and the anal tonsil. Variation in thickness, morphology of the folds, and the presence of Peyer's patches allowed to distinguish the duodenal ampulla and the distal segments from the rest of the intestine. Within the LNs, B lymphocytes represented the predominant cell population. This study establishes a reliable methodology for the characterization of the histological structure of the GIT and associated lymphoid tissue in cetaceans and provides a description of the histological structure of those organs in harbour porpoise, useful for future research studies.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

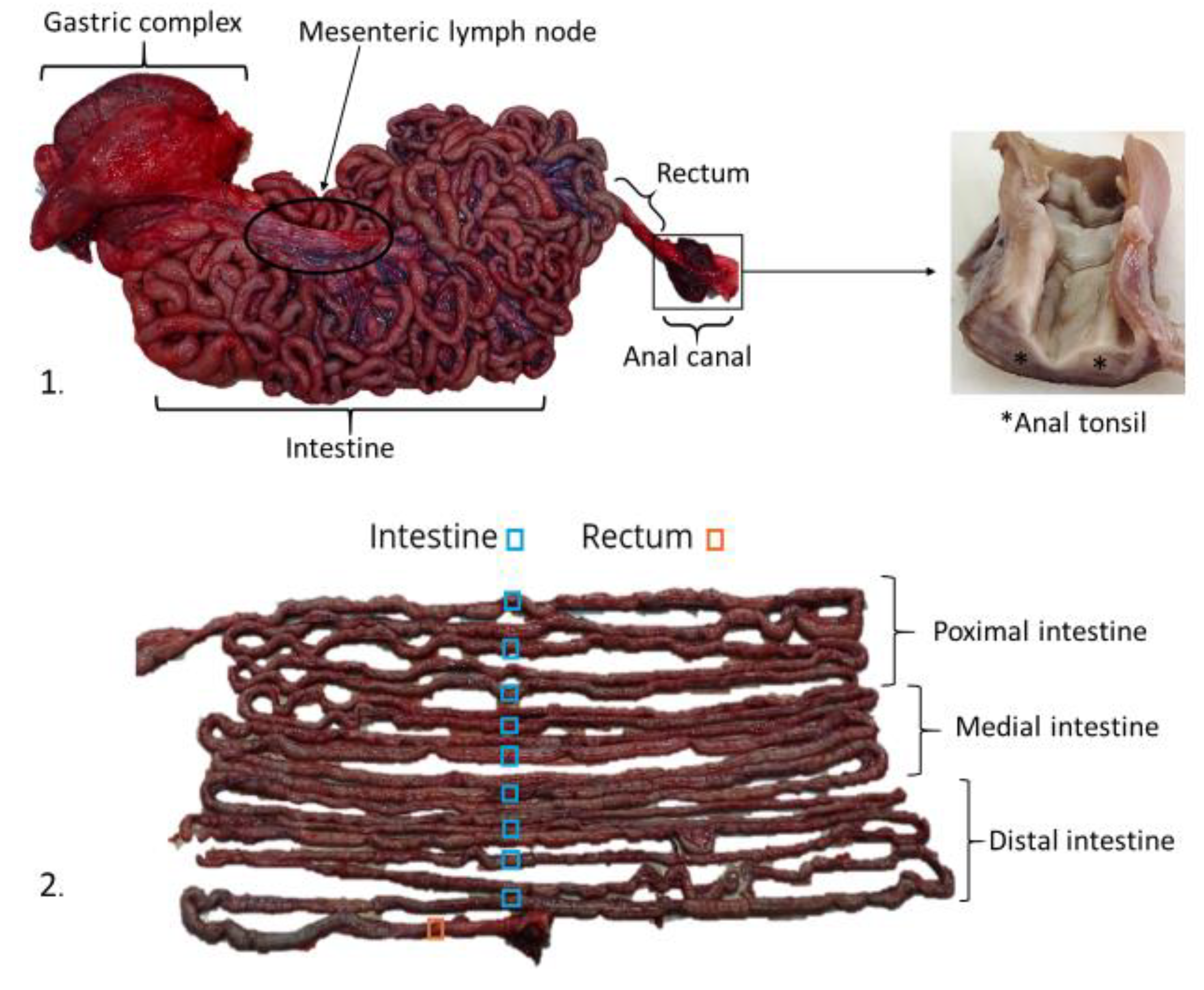

2.1. Sampling

2.2. Histology and Immunohistochemistry

2.3. Measurement of Histological Layer Thickness in the GIT

2.4. Evaluation and Quantification of Cell Types in the Gastrointestinal Tract (GIT) and Lymph Nodes (LNs)

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

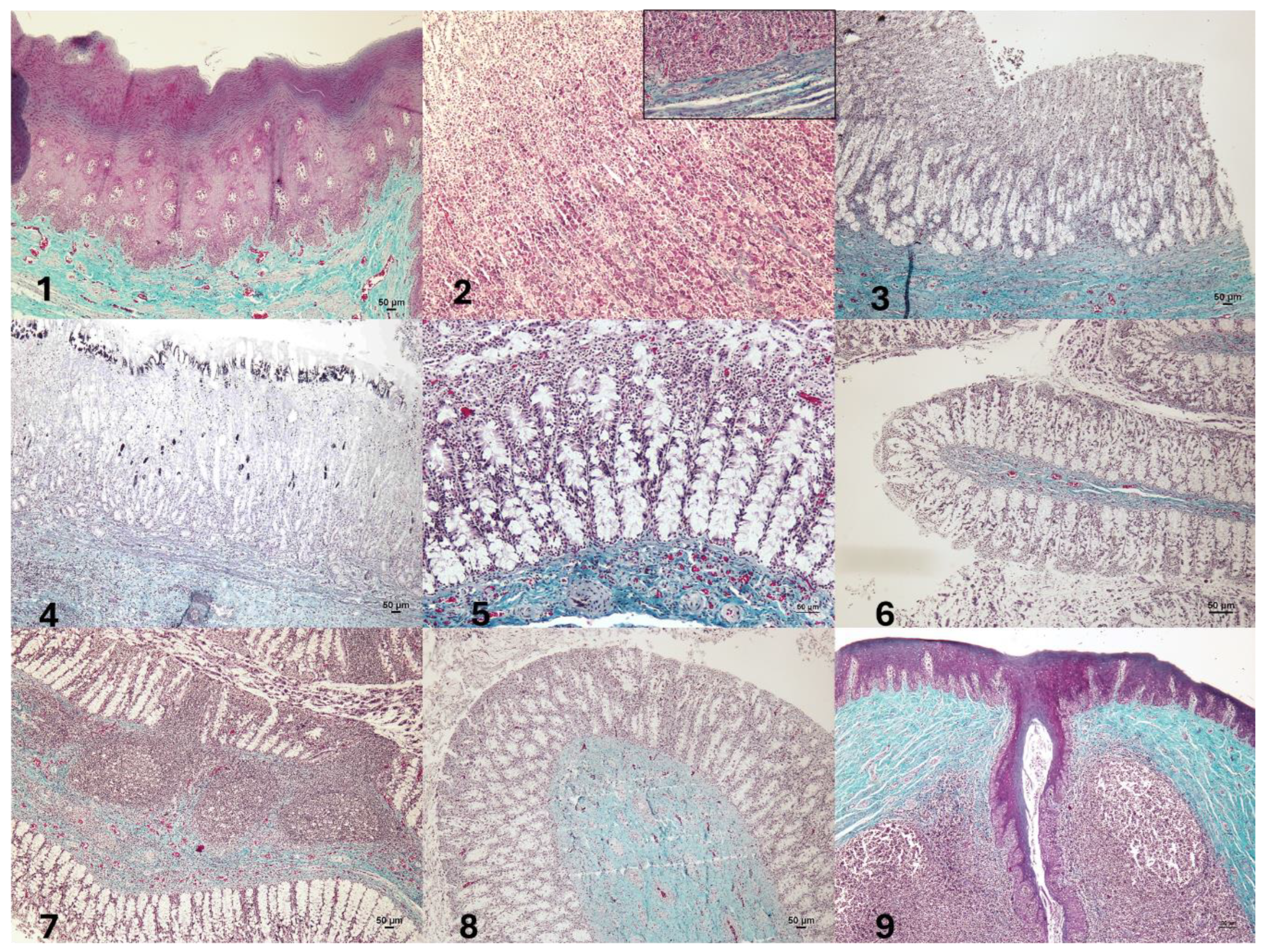

3.1. Histological Structure of the Gastrointestinal Tract (GIT)

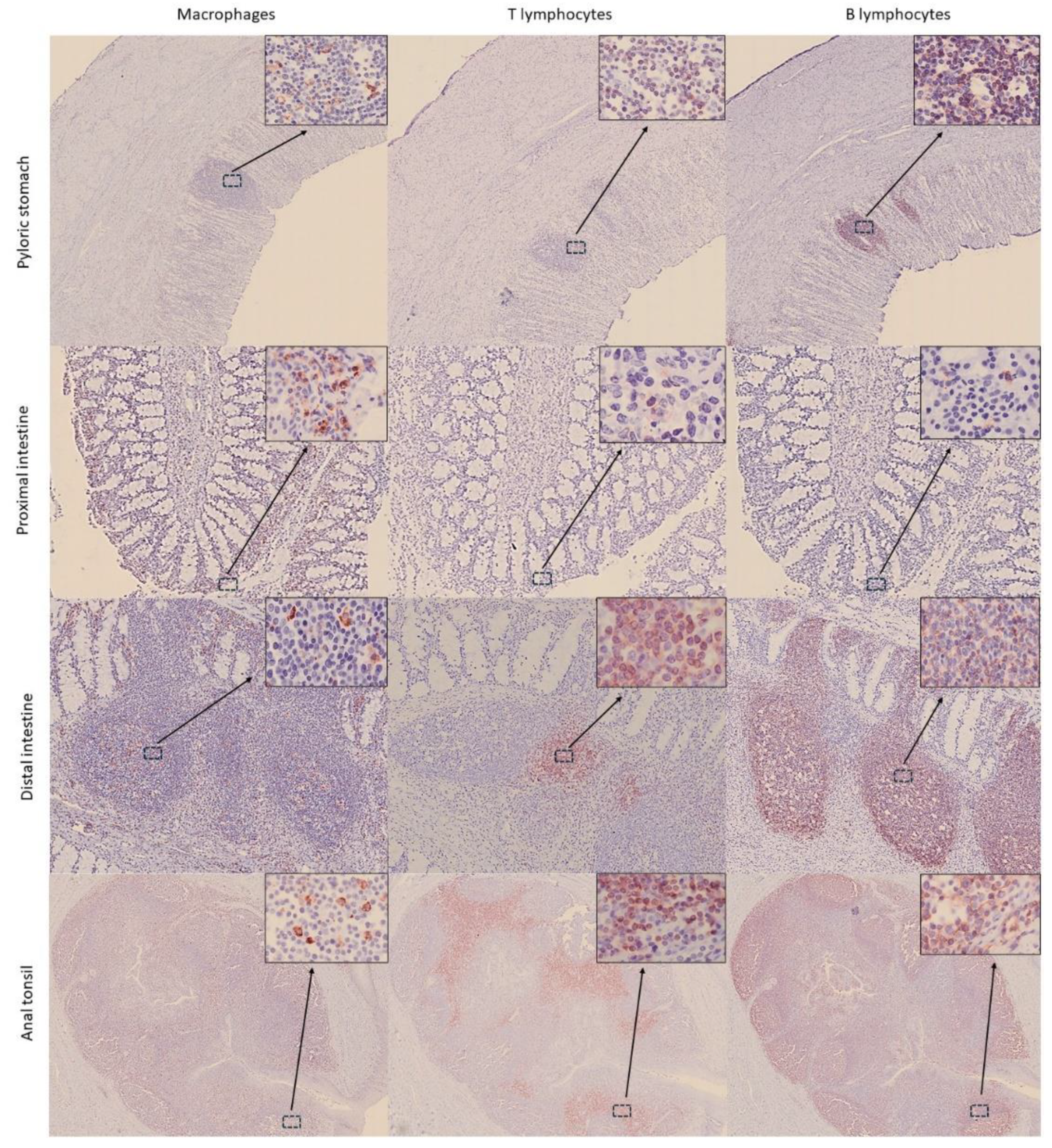

3.2. Distribution of Immune Cells Within Gastrointestinal Tract (GIT) and Associated Lymphoid Tissue

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BL TL GALT GIT IBA1 IHC LN |

B lymphocytes T lymphocytes Gut associated lymphoid tissue Gastrointestinal tract Ionized calcium-binding molecule 1 Immunohistochemistry Lymph node |

References

- Cozzi, B.; Huggenberger, S.; Oelschläger, H. Anatomy of dolphins: insights into body structure and function, 1st ed.; Academic press: London, UK, 2017; pp. 344–359. [Google Scholar]

- Fiorucci, L. Determinación de los principales datos de referencia para el examen del tracto gastrointestinal en delfines mulares (Tursiops truncatus) clínicamente sanos bajo el cuidado humano. Doctoral Dissertation, Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rommel, S.A.; Lowenstine, L.J. Gross and microscopic anatomy. In CRC Handbook of marine mammal medicine, 1st ed.; Dierauf, L.A., Gulland, F.M.D., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Ratón, USA, 2001; pp. 129–164. [Google Scholar]

- Huggenberger, S. : Oelschläger, H.; Cozzi, B. Atlas of the anatomy of dolphins and whales, 1st ed.; Academic press: London, UK, 2019; pp. 363–479. [Google Scholar]

- Caballero Cansino, M.J.; Jaber Mohamad, J.R.; Fernández Rodríguez, A. Atlas de histología de peces y cetáceos, 1st ed.; Vicerrectorado de Planificación y Calidad de la Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria: Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, España, 2005; pp. 87–94. [Google Scholar]

- Mead, J.G. Gastrointestinal tract. In Encyclopedia of marine mammals., 2nd ed.; Perrin, W.F., Würsig, B., Thewissen, J.G.M., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2009; pp. 472–477. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, R.J.; Johnson, F.R.; Young, B.A. The small intestine of dolphins (Tursiops, Delphinus, Stenella). In Functional Anatomy of Marine Mammals., 1st ed.; Harrison, R.J., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, USA, 1977; pp. 297–331. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan, D. F.; Smith, T. L. Morphology of the lymphoid organs of the bottlenose dolphin, Tursiops truncates. J Anat 1999, 194, 505–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bemark, M.; Pitcher, M. J.; Dionisi, C.; Spencer, J. Gut-associated lymphoid tissue: a microbiota-driven hub of B cell immunity. Trends Immunol 2024, 45, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivares-Villagómez, D.; Van Kaer, L. Intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes: sentinels of the mucosal barrier. Trends Immunol 2018, 39, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romano, T.A.; Felten, S.Y.; Olschowka, J.A.; Felten, D.L. A microscopic investigation of the lymphoid organs of the beluga, Delphinapterus leucas. J Morphol 1993, 215, 261–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, F. M. O.; Guimarães, J. P.; Vergara-Parente, J. E.; Carvalho, V. L.; Carolina, A.; Meirelles, O.; Marmontel, M.; Oliveira, B. S. S. P.; Santos, S. M.; Becegato, E. Z.; Evangelista, J. S. A. M.; Miglino, M. A. Morphology of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue in odontocetes. Micros Res Tech 2016, 79, 845–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, L.S.; Turner, J.P.; Cowan, D.F. Involution of lymphoid organs in bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) from the western Gulf of Mexico: implications for life in an aquatic environment. Anat Rec 2005, 282A, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuković, S.; Lucić, H.; Gomerčić, H.; Duras-Gomerčić, M.; Gomerčić, T.; Škrtić, D.; Vurković, S. Morphology of the lymph nodes in bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) and striped dolphin (Stenella coeruleoalba) from the Adriatic Sea. Acta Vet Hung 2005, 53, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskov, M.; Schiwatschewa, T.; Bonev, S. Comparative histological study of lymph nodes in mammals. Lymph nodes of the dolphin. Anat Anz 1969, 124, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bankhead, P.; Loughrey, M.B.; Fernández, J.A.; Dombrowski, Y.; McArt, D. G.; Dunne, P.D.; McQuaid, S.; Gray, R.T.; Murray, L.J.; Coleman, H.G.; James, J.A.; Salto-Tellez, M.; Hamilton, P.W. QuPath: Open source software for digital pathology image analysis. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, J. C.; Gardner, M.D. Comparative microscopic anatomy of selected marine mammals. In Mammals of the sea: biology and medicine., 1st ed.; Ridgway, S.H., Ed.; Charles C Thomas: Springfield, USA, 1972; pp. 298–418. [Google Scholar]

- Russo, F.; Gatta, C.; De Girolamo, P.; Cozzi, B.; Giurisato, M.; Lucini, C.; Varricchio, E. Expression and immunohistochemical detection of leptinlike peptide in the gastrointestinal tract of the South American sea lion (Otaria flavescens) and the bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus). Anat Rec 2012, 295, 1482–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frappier, B.L. Digestive system. In Dellmann’s textbook of veterinary histology., 6th ed.; Eurell, J.A., Frappier, B.L., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing: Ames, USA, 2006; pp. 170–211. [Google Scholar]

- Junqueira, L.C.; Carneiro, J. Junqueira & Carneiro. Histología básica. Texto y atlas, 13th ed.; Editorial Médica Panamericana: City of Mexico, Mexico, 2022; pp. 308–329. [Google Scholar]

- Buendía Martín, A.J.; Durán Flórez, E.; Gázquez Ortiz, A.; Gómez Cabrera, S.; Méndez Sánchez, A.; Navarro Cámara, J.A. Aparato digestivo. In Tratado de histología veterinaria., 1st ed.; Gázquez Ortiz, A., Blanco Rodríguez, A., Eds.; Masson: Barcelona, Spain, 2004; pp. 239–280. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, F. M. D. O. E.; Guimarães, J. P.; Vergara-parente, J. E.; Carvalho, V. L.; De Meirelles, A. C. O.; Marmontel, M. , Ferrão, J. S. P.; Miglino, M. A. Morphological análisis of lymph nodes in odontocetes from northand northeast coast of Brazil. Anat Rec 2014, 297, 939–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Primary antibody (dilution) |

Cell type detected |

Clone nº | Source | Secondary antibody (dilution) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IBA11 (1:1000) |

Macrophages |

Polyclonal 019-19741 |

FLUJIFILM-Wako Chemicals Eu-rope GmbH, Neuss, Germany | Goat anti-rabbit (1:200) |

| CD3 (1:500) |

T lymphocytes |

Monoclonal NCL-L-CD3-565 |

Novacastra, Leica Biosystem, Newcastle, UK | Horse anti-mouse (1:200) |

| CD20 (1:400) |

B lymphocytes |

Polyclonal PA5-16701 |

ThermoFisher, Massachusetts, USA | Goat anti-rabbit (1:200) |

| Structure | Mucosa | Submucosa | Muscularis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forestomach (FS) | Stratified keratinized epithelium. Muscularis mucosae highly developed. Absence of glands. Thickness: 937 microns (µm). | No glands. Submucosal plexus. Thickness: 252 µm. | Layers difficult to differentiate. Myenteric plexus. Thickness: 1430 µm. |

| Main stomach (MS) | Simple columnar epithelium. Gastric pits with secretory cells. Muscularis mucosae less developed than in E1. Thickness: 3180 µm. | No glands. Submucosal plexus. Thickness: 403 µm. | Inner and outer layers easily distinguishable. Myenteric plexus. Thickness: 913 µm (inner) and 432 µm (outer). |

| Pyloric stomach (PS) | Simple columnar epithelium. Pyloric glands. Muscularis mucosae. Thickness: 1260 µm. | No glands. Submucosal plexus. Thickness: 292 µm. | Inner and outer layers easily distinguishable. Myenteric plexus. Thickness: 774 µm (inner) and 212 µm (outer). |

| Duodenal ampulla (DA) | Simple columnar epithelium. Mucous glands. Muscularis mucosae poorly developed. No folds. Thickness: 1140 µm. | No glands. No submucosal plexus. Thickness: 639 µm. | Inner and outer layers easily distinguishable. Myenteric plexus. Thickness: 712 µm (inner) and 512 µm (outer). |

| Proximal intestine 1 (PI1) | Simple columnar epithelium. Mucous glands. Muscularis mucosae very poorly developed. No villi. Numerous folds. Thickness: 272 µm. | No glands. No submucosal plexus. Thickness: 135 µm. | Inner and outer layers easily distinguishable. Myenteric plexus. Thickness: 245 µm (inner) and 61.8 µm (outer). |

| Proximal intestine 2 (PI2) | Simple columnar epithelium. Mucous glands. Muscularis mucosae very poorly developed. No villi. Numerous folds. Thickness: 461 µm. | No glands. No submucosal plexus. Thickness: 97.6 µm. | Inner and outer layers easily distinguishable. Myenteric plexus. Thickness: 629 µm (inner) and 162 µm (outer). |

| Proximal intestine 3 (PI3) | Simple columnar epithelium. Mucous glands. Muscularis mucosae very poorly developed. No villi. Numerous folds. Thickness: 361 µm. | No glands. No submucosal plexus. Thickness: 96.8 µm. | Inner and outer layers easily distinguishable. Myenteric plexus. Thickness: 629 µm (inner) and 191 µm (outer). |

| Middle intestine 1 (MI1) | Simple columnar epithelium. Mucous glands. Muscularis mucosae very poorly developed. No villi. Numerous folds. Thickness: 351 µm. | No glands. No submucosal plexus. Thickness: 63.9 µm. | Inner and outer layers easily distinguishable. Myenteric plexus. Thickness: 522.464 µm (inner) and 130 µm (outer). |

| Middle intestine 2 (MI2) | Simple columnar epithelium. Mucous glands. Muscularis mucosae very poorly developed. No villi. Few folds. Thickness: 423 µm. | No glands. No submucosal plexus. Thickness: 96.3 µm. | Inner and outer layers easily distinguishable. Myenteric plexus. Thickness: 456 µm (inner) and 91.4 µm (outer). |

| Middle intestine 3 (MI3) | Simple columnar epithelium. Mucous glands. Muscularis mucosae very poorly developed. No villi. Few folds. Thickness: 373 µm. | No glands. No submucosal plexus. Thickness: 111 µm. | Inner and outer layers easily distinguishable. Myenteric plexus. Thickness: 408 µm (inner) and 124 µm (outer). |

| Distal intestine 1 (DI1) | Simple columnar epithelium. Mucous glands. Muscularis mucosae very poorly developed. No villi. Few folds. Thickness: 328 µm. | No glands. No submucosal plexus. Thickness: 142 µm. | Inner and outer layers easily distinguishable. Myenteric plexus. Thickness: 359 µm (inner) and 112 µm (outer). |

| Distal intestine 2 (DI2) | Simple columnar epithelium. Mucous glands. Muscularis mucosae very poorly developed. No villi. Few folds. Thickness: 364 µm. | No glands. No submucosal plexus. Thickness: 142 µm. | Inner and outer layers easily distinguishable. Myenteric plexus. Thickness: 373 µm (inner) and 90.3 µm (outer). |

| Distal intestine 3 (DI3) | Simple columnar epithelium. Mucous glands. Muscularis mucosae very poorly developed. No villi. Few folds. Thickness: 344 µm. | No glands. No submucosal plexus. Thickness: 143 µm. | Inner and outer layers easily distinguishable. Myenteric plexus. Thickness: 518 µm (inner) and 103 µm (outer). |

| Rectum (R) | Simple columnar epithelium. Mucous glands. No muscularis mucosae. Wide folds. Thickness: 737 µm. | No glands. Submucosal plexus present. | Inner and outer layers easily distinguishable. Myenteric plexus. Thickness: 808 µm (inner) and 353 µm (outer). |

| Anal canal (AC) | Stratified keratinized epithelium. Crypts with stratified keratinized epithelium. No glands. No muscularis mucosae. Thickness: 3400 µm. | No glands. No submucosal plexus. Large lymphoid aggregates (anal tonsil). | Inner and outer layers easily distinguishable. Myenteric plexus. Thickness: 854 µm (inner) and 544 µm (outer). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).