Submitted:

20 October 2025

Posted:

20 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

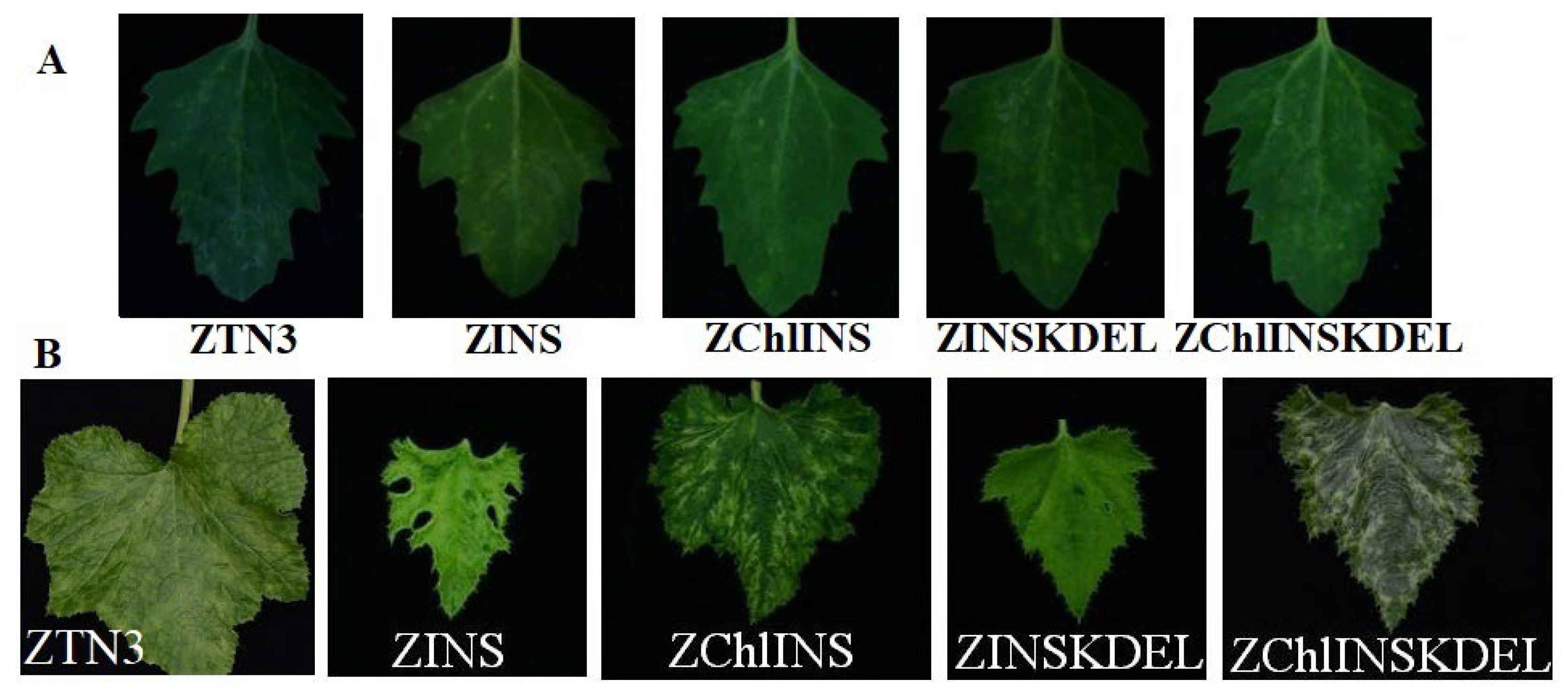

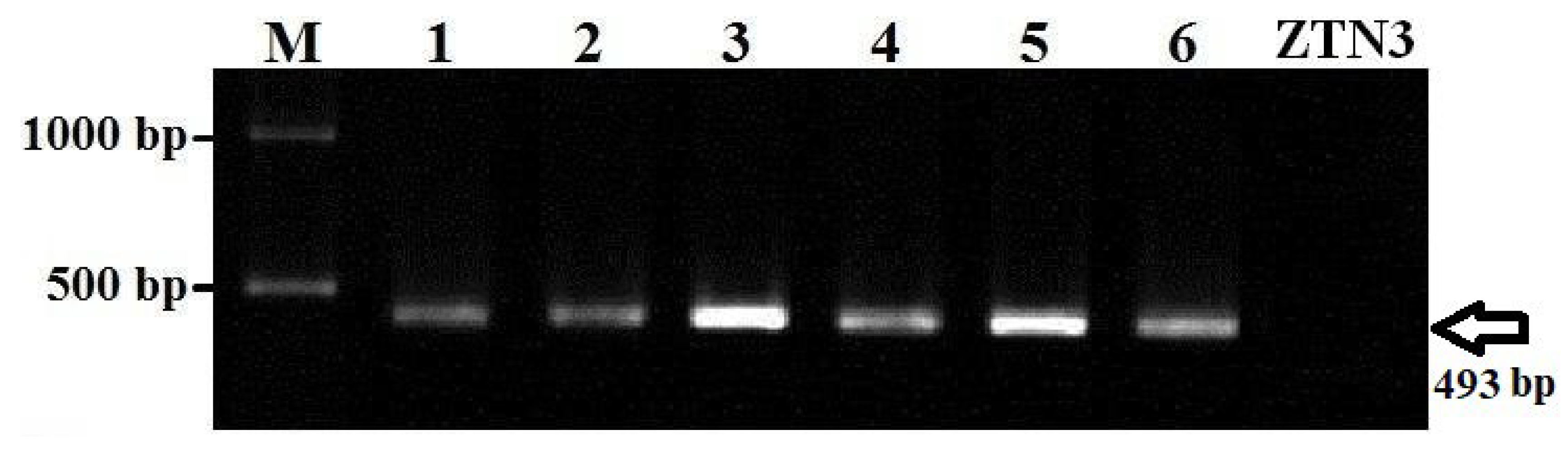

2.1. Infectivity, Stability and Confirmation of the ZYMV Recombinants

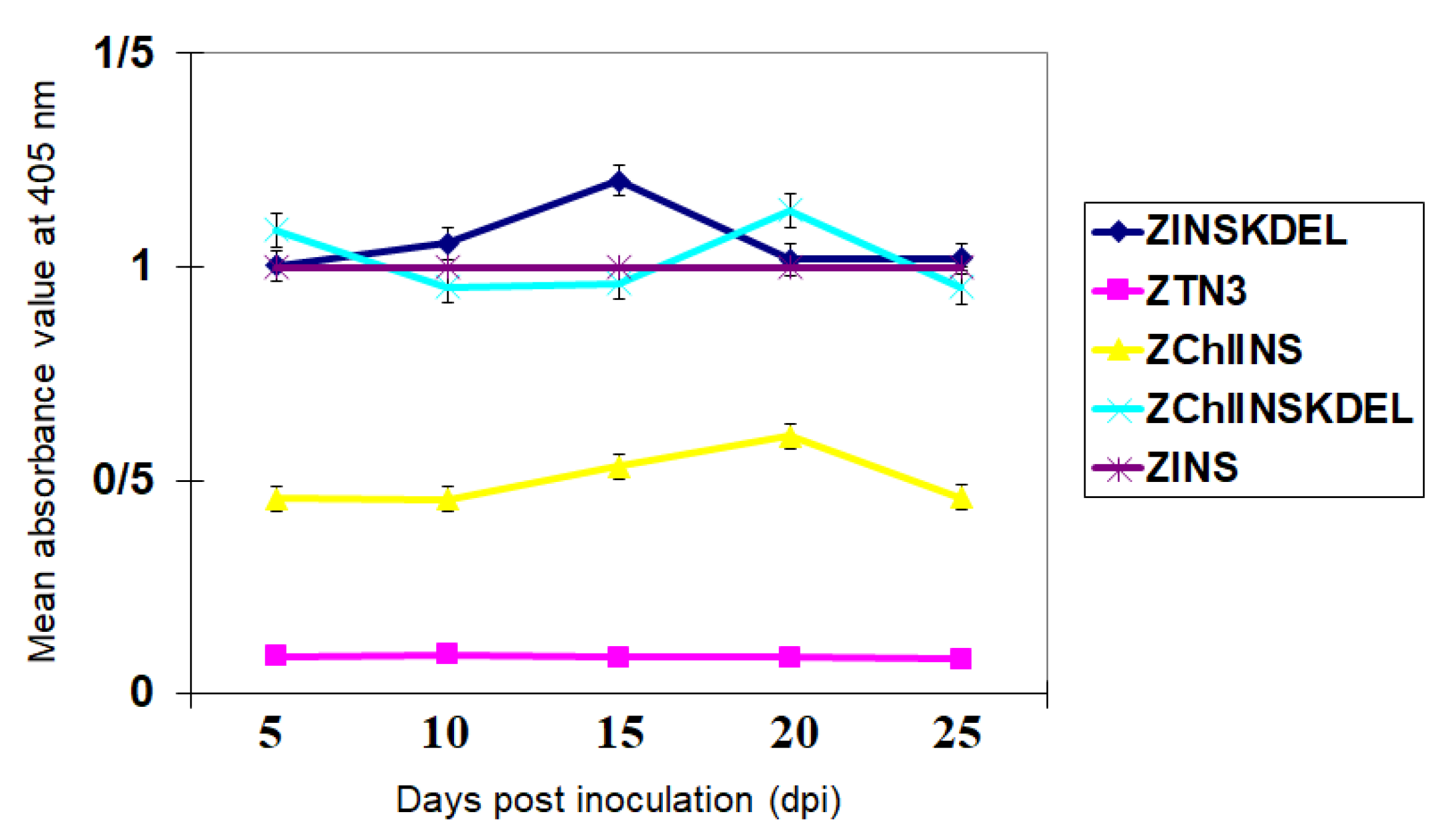

2.2. Detection of ZYMV-Expressed INS

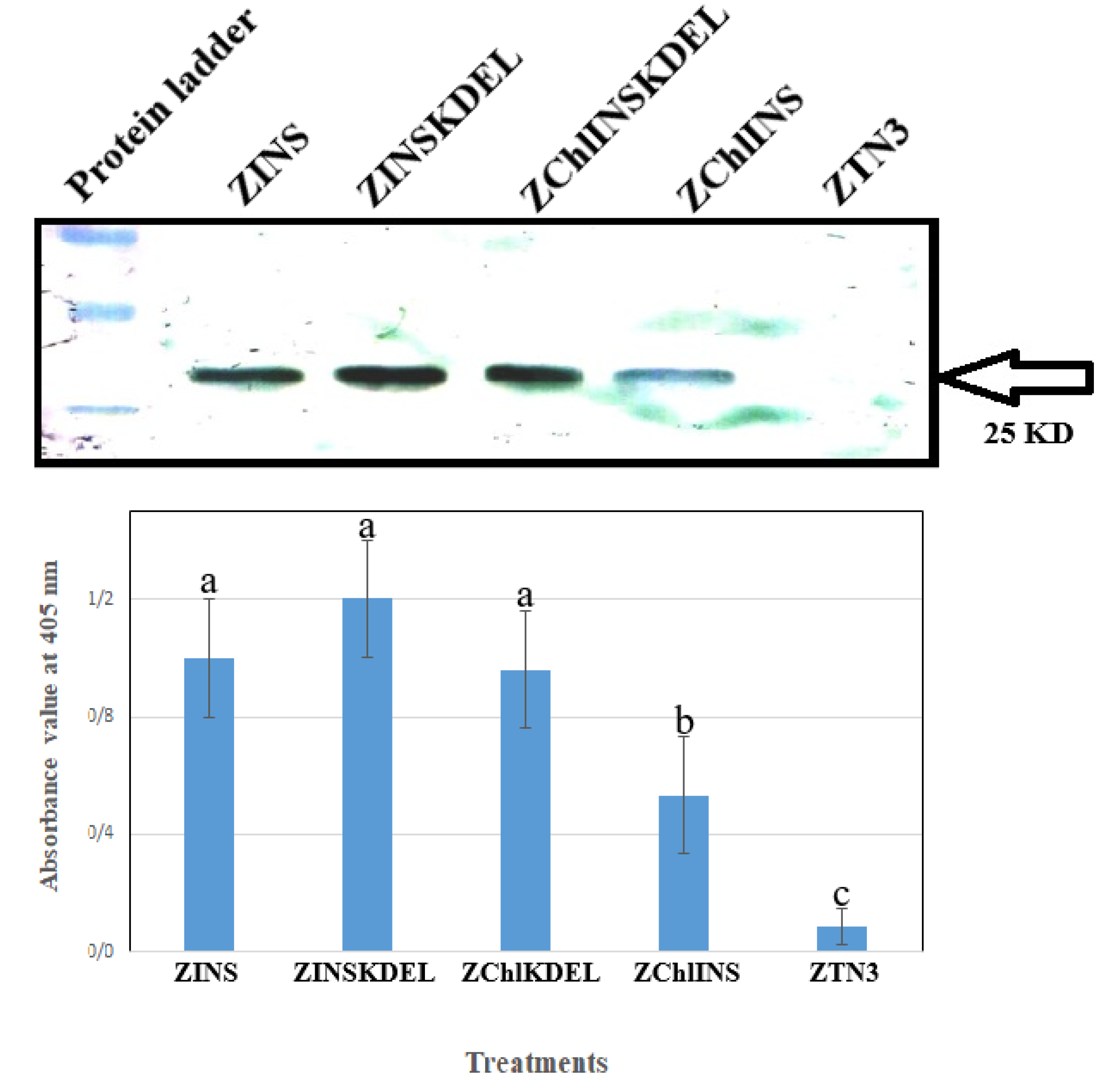

2.3. Purification of ZYMV-Expressed INS from the Infected Squash Plants

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and DNA Sources

4.2. Polymerase Chain Reaction

4.3. Digestion and Cloning of INS to ZYMV Vector

4.4. Infectivity Assay of Chimeric Constructs and RT-PCR Confirmation

4.5. Stability Assay of Recombinants in the Host Plants

4.6. Immunoassay Tests (ELISA, Western Blot)

4.6. Purification of the Expressed INS

5. Conclusions

References

- Walsh, G.; Walsh, E. Biopharmaceutical benchmarks 2022. Nat. Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 1722–1760.

- Baeshen, N.A.; Baeshen, M.N.; Sheikh, A.; Bora, R.S.; Ahmed, M.M.M.; Ramadan, H.A.; Saini, K.S.; Redwan, E.M. Cell factories for insulin production. Microb. Cell Factories 2014, 13, 1–9.

- Jadhav, R.R.; Khare, D. Green biotherapeutics: overcoming challenges in plant-based expression platforms. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2024, 1–22.

- Buyel, J.F. Plant molecular farming–integration and exploitation of side streams to achieve sustainable biomanufacturing. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 9, 1893.

- Sethi, L.; Kumari, K.; Dey, N. Engineering of plants for efficient production of therapeutics. Mol. Biotechnol. 2021, 63, 1125–1137.

- Gaikwad, B.; Wagh, N.; Lakkakula, J. Current scenario of recombinant proteins: extraction, purification, concentration, and storage. In Fundamentals of Recombinant Protein Production, Purification and Characterization; Elsevier: 2025; pp. 173–189.

- Rozov, S.M.; Deineko, E.V. Increasing the efficiency of the accumulation of recombinant proteins in plant cells: the role of transport signal peptides. Plants 2022, 11, 2561.

- Lee, J.; Lee, S.-K.; Park, J.-S.; Lee, K.-R. Plant-made pharmaceuticals: exploring studies for the production of recombinant protein in plants and assessing challenges ahead. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2023, 17, 53–65.

- Eidenberger, L.; Kogelmann, B.; Steinkellner, H. Plant-based biopharmaceutical engineering. Nat. Rev. Bioeng. 2023, 1, 426–439.

- Mahmood, M.A.; Naqvi, R.Z.; Rahman, S.U.; Amin, I.; Mansoor, S. Plant virus-derived vectors for plant genome engineering. Viruses 2023, 15, 531.

- Song, S.-J.; Diao, H.-P.; Guo, Y.-F.; Hwang, I. Advances in Subcellular Accumulation Design for Recombinant Protein Production in Tobacco. BioDesign Res. 2024, 6, 0047.

- Mardanova, E.S.; Vasyagin, E.A.; Ravin, N.V. Virus-like Particles Produced in Plants: A Promising Platform for Recombinant Vaccine Development. Plants 2024, 13, 3564.

- Wang, D.; Li, G. Biological and molecular characterization of Zucchini yellow mosaic virus isolates infecting melon in Xinjiang, China. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 2017, 39, 48–59.

- Bubici, G.; Navarro, B.; Carluccio, A.V.; Ciuffo, M.; Di Serio, F.; Cillo, F. Genomic sequence variability of an Italian Zucchini yellow mosaic virus isolate. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2020, 156, 325–332.

- Gleba, Y.; Klimyuk, V.; Marillonnet, S. Viral vectors for the expression of proteins in plants. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2007, 18, 134–141, doi:S0958-1669(07)00033-X [pii].

- Zaidi, S.S.-e.-A.; Mansoor, S. Viral vectors for plant genome engineering. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 539.

- Yang, Y.-Z.; Xie, L.; Gao, Q.; Nie, Z.-Y.; Zhang, D.-L.; Wang, X.-B.; Han, C.-G.; Wang, Y. A potyvirus provides an efficient viral vector for gene expression and functional studies in Asteraceae plants. Plant Physiol. 2024, 196, 842–855.

- Nassaj Hosseini, S.M.; Shamsbakhsh, M.; Yeh, S.D. Co-Infection of Cucumber Mosaic Virus Could Stabilize Its Recombinant Coat Protein Expressed by Zucchini Yellow Mosaic Virus. Iran. J. Biotechnol. 2025, 23, 92–101.

- Gupta, S.; Mishra, P.; Mishra, P.; Tewari, V.; Pandey, S. Transgenic animals and plants: application and future scope. In Medicinal Biotechnology; Elsevier: 2025; pp. 61–77.

- Hosseini, S.M.N.; Bakhsh, M.S.; Salmanian, A.H.; Ye, S.D. Expression and purification of movement protein of Cucumber green mottle mosaic virus using a plant-virus expression system. 2013.

- Song, E.G.; Ryu, K.H. A pepper mottle virus-based vector enables systemic expression of endoglucanase D in non-transgenic plants. Arch. Virol. 2017, 162, 3717–3726.

- Mei, Y.; Beernink, B.M.; Ellison, E.E.; Konečná, E.; Neelakandan, A.K.; Voytas, D.F.; Whitham, S.A. Protein expression and gene editing in monocots using foxtail mosaic virus vectors. Plant Direct 2019, 3, e00181.

- German-Retana, S.; Candresse, T.; Alias, E.; Delbos, R.-P.; Le Gall, O. Effects of green fluorescent protein or β-glucuronidase tagging on the accumulation and pathogenicity of a resistance-breaking Lettuce mosaic virus isolate in susceptible and resistant lettuce cultivars. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2000, 13, 316–324.

- Arazi, T.; Slutsky, S.G.; Shiboleth, Y.M.; Wang, Y.; Rubinstein, M.; Barak, S.; Yang, J.; Gal-On, A. Engineering zucchini yellow mosaic potyvirus as a non-pathogenic vector for expression of heterologous proteins in cucurbits. J. Biotechnol. 2001, 87, 67–82.

- Nykiforuk, C.L.; Boothe, J.G.; Murray, E.W.; Keon, R.G.; Goren, H.J.; Markley, N.A.; Moloney, M.M. Transgenic expression and recovery of biologically active recombinant human insulin from Arabidopsis thaliana seeds. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2006, 4, 77–85.

- Boyhan, D.; Daniell, H. Low--cost production of proinsulin in tobacco and lettuce chloroplasts for injectable or oral delivery of functional insulin and C--peptide. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2011, 9, 585–598.

- Jin, C.; Hinterdorfer, P.; Lee, J.H.; Ko, K. Plant production systems for recombinant immunotherapeutic proteins. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2025, 19, 1–14.

- Burlec, A.F.; Pecio, Ł.; Mircea, C.; Cioancă, O.; Corciovă, A.; Nicolescu, A.; Oleszek, W.; Hăncianu, M. Chemical profile and antioxidant activity of Zinnia elegans Jacq. fractions. Molecules 2019, 24, 2934.

- Venkataraman, S. Plant molecular pharming and plant-derived compounds towards generation of vaccines and therapeutics against coronaviruses. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1805.

- Moustafa, K.; Makhzoum, A.; Trémouillaux-Guiller, J. Molecular farming on rescue of pharma industry for next generations. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2016, 36, 840–850.

- Ward, B.J.; Gobeil, P.; Séguin, A.; Atkins, J.; Boulay, I.; Charbonneau, P.-Y.; Couture, M.; D’Aoust, M.-A.; Dhaliwall, J.; Finkle, C. Phase 1 randomized trial of a plant-derived virus-like particle vaccine for COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1071–1078.

- Venkataraman, S.; Khan, I.; Habibi, P.; Le, M.; Lippert, R.; Hefferon, K. Recent advances in expression and purification strategies for plant made vaccines. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1273958.

- Hsu, C.H.; Lin, S.S.; Liu, F.L.; Su, W.C.; Yeh, S.D. Oral administration of a mite allergen expressed by zucchini yellow mosaic virus in cucurbit species downregulates allergen-induced airway inflammation and IgE synthesis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004, 113, 1079–1085. [CrossRef]

- Sambrook, J.; Russell, D.W. Detection of DNA in agarose gels. Mol. Cloning A Lab. Man. ,(3rd Ed.) Cold Spring Harb. Lab. Press New York 2001, 5–14.

- Gooderham, K. Transfer techniques in protein blotting. Methods Mol Biol 1984, 1, 165–178. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Gonsalves, D. ELISA detection of various tomato spotted wilt virus isolates using specific antisera to structural proteins of the virus. 1990.

- Gal-On, A.; Canto, T.; Palukaitis, P. Characterisation of genetically modified cucumber mosaic virus expressing histidine-tagged 1a and 2a proteins. Arch. Virol. 2000, 145, 37–50.

| Manufacturing company | application | Restriction site | Primer length | Sequence (restriction sites have been underlined) | Primer name | ||

| MDBio | To produce complementary DNA | - | 20 | ACTTTGCACACATGATCTGG | mz1155 | ||

| MDBio | To run RT-PCR | - | 22 | AGAAAGTGGTGCAAAAGCAAAC | pZ629 | ||

| Genomics | To amplify Pro-Insulin with SphI restriction site | SphI | 33 | CACCATGGCATGCATGGAAGCGGGATTCAACCA | pINS-SN | ||

| Genomics | To amplify Pro-Insulin with KpnI restriction site | KpnI | TAGCTAGCGGTACCGTTGCAGTAGTTTTCCAG | mINS-KN | |||

| Genomics | To add chloroplast signal peptide | SphI | 48 | ATGCATGCACCTGCGCATTGGACTCTTCCATAGTGGTCAACTTCGCTA | mzp1Chltag | ||

| Genomics | To screen recombinants with chloroplast signal peptide | - | 21 | GGAAGAGTCCAATGCGCAGGT | pchltag | ||

| MDBio | To add and screen SEKDEL signal peptide | NcoI | 47 | TTTTCCATGGAAGACTGGTGAAACACATGTAGCTCATCTTTCTCAGA | mKDELnss |

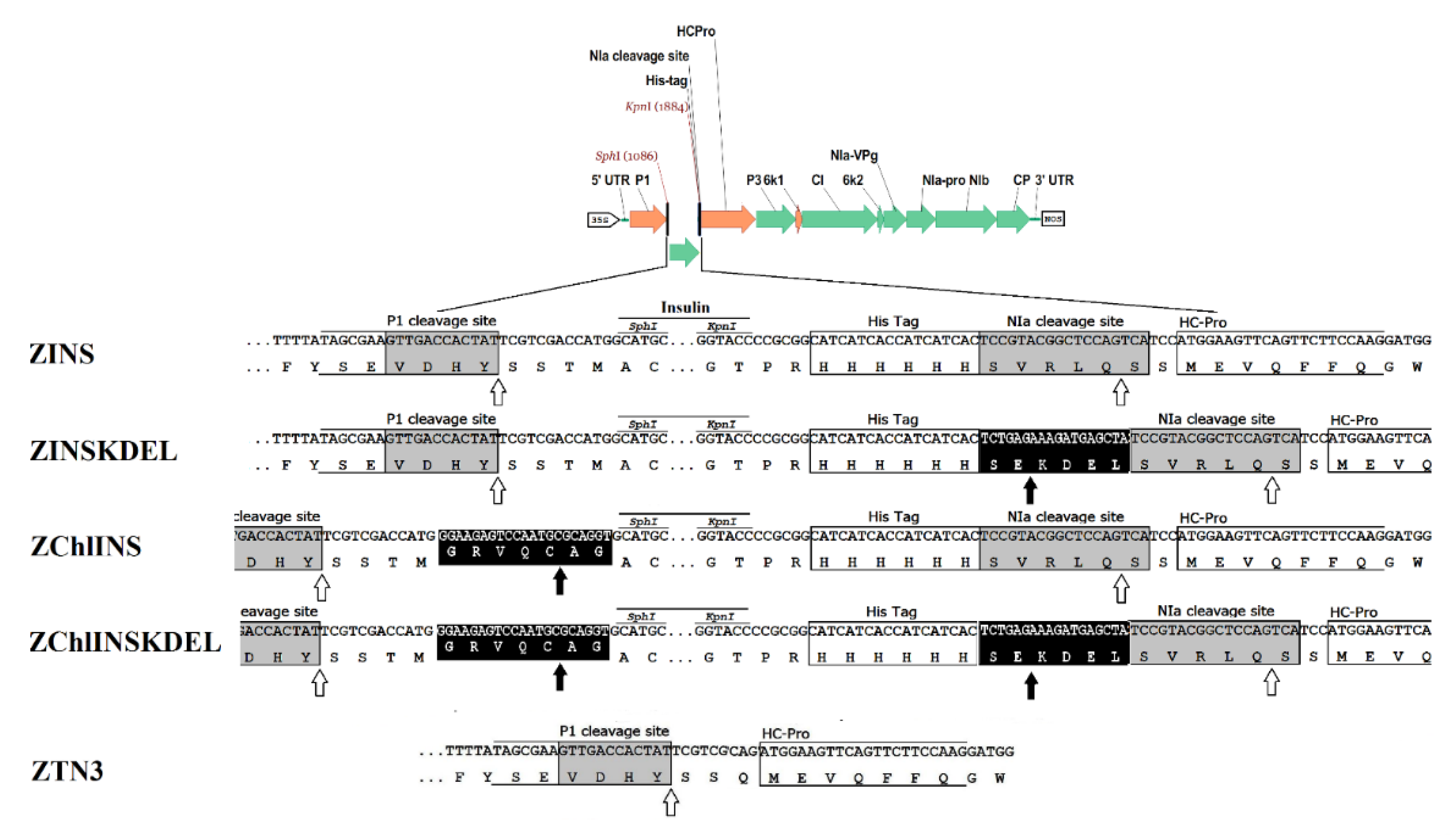

| Abbreviate name | Foreign gene | Tag type and its position | Signal peptide type and its position |

| ZINS | Proinsulin | His tag at the C-termini | - |

| ZChlINS | Proinsulin | His tag at the C-termini | Chloroplast signal peptide at the N-termini |

| ZChlINSKDEL | Proinsulin | His tag at the C-termini | Chloroplast signal peptide at the N-termini and SEKDEL at the C-termini |

| ZINSKDEL | Proinsulin | His tag at the C-termini | SEKDEL at the C-termini |

| ZTN3 | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).