1. Introduction

Fractional differentiation extends integer-order differentiation and integration to arbitrary orders. There is a growing interest in developing numerical methods for fractional differential equations due to their wide applicability in various branches of science [

2,

3,

4]. Finite difference schemes provide a powerful approach for the numerical solution of fractional differential equations and the study of their properties. The Caputo fractional derivative of order

, where

, is defined as

The power function

and the functions

,

, and

have fractional derivatives.

where

and

is the Mittag-Leffler function

The lower limit of fractional differentiation may be an arbitrary number. The kernel of the fractional derivative has a singularity of order

. A direct application of numerical integration methods for discretizations of the fractional derivative leads to reduced accuracy and a lower order of approximation. Therefore, the construction of high-order approximations of fractional derivatives requires additional considerations.

Fractional calculus is a rapidly developing scientific field that extends and generalizes differential calculus. Other definitions of fractional derivatives and integrals include the Riemann–Liouville and Grünwald–Letnikov derivatives, introduced in the 19

th century. The Riemann–Liouville derivative is the first known generalization of integer-order derivatives and is a widely used definition in fractional calculus. The three definitions of the fractional derivative are directly related and share similar properties. The main difference between fractional and integer-order derivatives lies in their nonlocal properties. Fractional derivatives have a strong dependence on the previous values of the function according to the power law, or exhibit memory-influenced dynamics. The definition of integer-order derivatives depends only on the local behavior of the function in a small neighborhood around the point of differentiation. The definitions of integer-order derivatives imply an exponential dependence on previous values, and this effect may be negligible or minimal. The choice of a particular definition of the fractional derivative and its advantages depend on the problem under consideration. The Caputo fractional derivative, defined in 1967, has the advantage that when solving differential equations, it allows the use of initial conditions expressed in terms of integer-order derivatives, which often have direct physical meaning. In addition to the most commonly used definitions of the fractional derivative, such as those of Riemann–Liouville and Caputo, there exist other important and widely applicable definitions in the theory of fractional calculus. Among them are the fractional derivatives of Weyl, Hadamard, Marchaud, and Riesz. The recently introduced fractional derivatives, the Caputo–Fabrizio derivative (2015), the Atangana–Baleanu–Caputo (ABC) fractional derivative (2016), have also proven their significance in modeling various time-dependent complex processes. These derivatives, provide improved accuracy in describing memory effects in physical, biological, and engineering phenomena [

5,

6,

7].

Fractional Differential Equations (FDEs) are a generalization of ordinary and partial differential equations and provide powerful tools for modeling complex systems with memory, hereditary properties, or anomalous diffusion. Due to the complexity of fractional differential equations and their corresponding models, numerical methods are the main and, in many cases, the only approach for solving them. Numerical methods could be applied to a much wider class of fractional differential equations compared to analytical methods. Many of the properties and approaches used for solving ordinary and partial differential equations are also applicable to the corresponding fractional differential equations. The development of numerical methods is based on the growing number and diversity of the considered models, as well as on the improvement of the technical means for their solution. The main types of approaches for solving differential and fractional differential equations include the Finite Difference Methods [

8,

9,

10,

11], Spectral Methods [

12,

13,

14,

15], Finite Element Methods [

16,

17], and Predictor–Corrector Methods [

18,

19].

Finite difference schemes for the numerical solution of fractional differential equations are widely used because of their simplicity, flexibility, and consistency of the numerical results. The difference schemes for fractional differential equations use discretizations of the fractional derivative on uniform or nonuniform grids over the interval of fractional differentiation. These approximations involve the previous values of the function, which leads to a more complex analysis of the difference schemes and increases the computational time required for their solution. Constructions of fast difference schemes for fractional differential equations that achieve optimal computational complexity using sum of exponentials approximation of the kernel function are presented in [

20,

21,

22,

23]. To improve the efficiency of difference schemes and achieve high computational accuracy, high-order approximations of the fractional derivative are used. The development of high-order approximations of the fractional derivative and the investigation of their properties are important problems in the construction and analysis of difference schemes for fractional differential equations. Constructions of second-order approximations are discussed in [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. High-order approximations of the fractional derivative are constructed in [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34].

The Grünwald–Letnikov difference approximation and the L1 approximation are important and widely used discretizations of fractional derivatives[

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. The Grünwald–Letnikov approximation has first-order accuracy and a generating function

. The L1 approximation has an accuracy of order

and a generating function

where

is the polylogarithm function. The generating function of an approximation of the fractional derivative satisfies

The present paper continues the study in [

1] and focuses on the properties of the L1 approximation and on methods for extending it to higher-order approximations while preserving the properties of the weights. Consider fractional differentiation on the interval

and a uniform net with a step size

, where

N is a positive integer. Denote

. L1 approximation of the Caputo derivative has an order

and is defined as:

where

and

The weights of L1 and Grünwald–Letnikov approximations have properties:

The properties of the weights of Grünwald–Letnikov and L1 approximations enable an efficient analysis of the stability and convergence of difference schemes for fractional differential equations.

In section 4 we obtain the second order expansion formula of the L1 approximation

where

One approach to constructing discretizations of the fractional derivative is by specifying the generating function. This method also applies to the construction of approximations for integer-order derivatives. In [

1], we constructed a parameter-dependent approximation of the first derivative and applied it to obtain a discretization of the fractional derivative of order

.

where

. Approximation (

4) has a generating function

where

b is a parameter,

.The generating function

has properties

In the present paper we use the method from [

1,

41] for constructing a parameter-dependent approximation of the second derivative

In

Section 4, we use (

5) to construct second-order approximations of the fractional derivative. By substituting the second derivative in the expansionn formula of the L1 approximation (

3) with its approximation

and choosing the parameter value

, we obtain a second-order approximation of the Caputo derivative

where

, and

From the formula for the sum of the zeta sequence, we obtain that the numbers

converge to the value of the zeta function

. By substituting

with

in (

3) and (

6), we obtain the second-order asymptotic expansion formula of the L1 approximation.

and a second order asymptotic approximation

where

, and

The value of the parameter

is chosen so that the weights of discretizations (

6) and (

8) satisfy properties (

2). One difference between the two approximations is that, while approximation (

6) has second-order accuracy for every

, the order of approximation in (

7) and(

8) varies from

when

to second order when

. In

Section 5, we prove that the difference schemes for fractional differential equations using both approximations achieve second-order accuracy. The results of the paper are summarized below.

In

Section 2, we derive an approximation (

5) of the second derivative. In

Section 3, we consider applications of approximation (

4) and its corresponding right-side approximation to the numerical solution of initial value and boundary value ordinary differential equations. These two approximations are related to two-point approximations and lead to efficient numerical methods whose performance and accuracy are comparable to standard finite difference methods. A convergence and error analysis of the numerical solution of a first-order ordinary differential equation is presented, with respect to the values of the parameter.

In

Section 4, we derive the second-order expansion formula (

3) of the L1 approximation and construct second-order approximations (

6) and (

8) of the fractional derivative. In

Section 5, we consider applications of approximations (

6) and (

8) to the construction of difference schemes for the two-term ordinary fractional differential equation and the fractional subdiffusion equation. The difference schemes based on approximations (

6) and (

8) achieve second-order accuracy, and the proof of their convergence and order relies on the magnitude of the last weight of the L1 approximation.

3. Numerical Solutions of Ordinary Differential Equations

The weights of the approximations (

4) and (

5) contain powers of the parameter

b, which makes it possible to use them in constructions of approximations of the fractional derivative satisfying property (

2). Both approximations can be derived from two-point approximations and are suitable for numerical solution of differential equations. In [

1] we showed that, with an appropriate choice of the parameter, the numerical methods using approximation (

4) attain an arbitrary order in

, and that their performance is comparable to standard difference schemes with respect to accuracy and computational time. Depending on the values of the parameters, the numerical solutions of initial- and boundary-value ordinary differential equations have different properties and regions of convergence [

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47]. In this section, we consider applications of (

4) and the corresponding right-hand approximation to the numerical solution of initial- and boundary-value ordinary differential equations. In the following we derive a two-point approximation corresponding to approximation

.

Express the formula in the form

Hence

From (

11) we obtain the two-point approximation

Approximation (

4) follows from successive applications of (

12). When

two-point approximation (

12) has a second order accuracy

From Taylor’s theorem we obtain an estimate for the error

where

. We consider an application of (

13) to the numerical solution of first-order ordinary differential equation

By substituting the first derivatives from the equation into (

13), we obtain

Canceling the error term yields a second-order numerical solution of equation (

14).

Example 1.

Consider the following ordinary differential equation

Equation (

17) has a solution

. The experimental results for the maximum error and the order of the numerical solution (

16) of equation (

17) are presented in

Table 1 and

Table 2. The experiments are carried out using Mathematica 13 and the orders of the numerical methods are computed by formula

.

The experimental results in

Table 1 and

Table 2 indicate that (

16) is of second order, and the error of the numerical solution is less than

when the parameter

. The error increases for decreasing values of the parameter

. The results in

Table 2 show that the error of the method becomes very large for

, exceeding

for

. Denote by

the error of (

16) at the point

. From (

15) and (

16) the sequence of the errors

satisfies the recursive formula

In the following we establish the convergence of numerical solution (

16) and obtain an estimate for the error.

Proof. Denote

Formula (

18) for the errors

takes the form

Then

Applying (

20) recursively

times yields

The numbers

satisfy the estimate

Therefore

Using the equality

we obtain

□

Claim 3. Let and . Then the function is decreasing.

Proof.

Since

is increasing and

it follows that

for all

x. Hence,

is decreasing. □

Lemma 4.

Let and . Then

Proof. From Claim 2

The function

is decreasing and has a maximum at

.

□

Lemma 5.

Let and . Then

Proof.

The function

is decreasing with respect to

N and

Therefore

□

Proof. The function

is increasing because its derivative is positive. Then

□

In most practical applications, it is sufficient to compute the solution of a differential equation with an error less than

. The estimate (6) for the error of the numerical method (

16) guarantees that, for

and

, the error of the solution is less than

for parameter values

.

We consider the case

. The results in

Table 2, as well as estimate (

21), show that in this case the error of the numerical solution (

16) of equation (

14) can become very large, exceeding

for

and

. We use the following approach to solve equation (

14) numerically: Consider the boundary-value ODE, which is obtained from equation (

14) by converting the initial condition into a boundary condition.

Equation (

23) is chosen so that its numerical solution can also serve as a numerical solution of equation (

14). This is justified because the difference between the solutions of the two equations is negligible for

. Note that the boundary condition may be specified at a different point, e.g.,

. In the following claim, we provide an estimate of the difference between the solutions of equations (

14) and (

23) on the interval

.

Claim 7.

Let and . Then the difference of the solutions of equations (14) and (23) satisfies the estimate

where .

Proof. The function

satisfies the equation

Therefore

Applying the condition

:

Substituting back:

□

The numerical solutions of the boundary value ordinary differential equation (

23) exhibit high accuracy for negative values of the parameter

L. In Claim 7, it was demonstrated that for negative values of the parameter,

the difference between the solutions of equations (

14) and (

23) is insignificant. These properties enable us to compute a numerical solution of equation (

23) on the interval

and employ this solution for equation (

14) on the interval

. In the following we compute the numerical solution of boundary value problem (

23) using the right approximation of (

11). Let

. The right-hand approximation corresponding to (

11) is obtained by the substitution

.

and has a related two-point approximation

When

and

approximation (

24) has a second order accuracy. We use the two-point approximation (

24) to obtain a numerical solution of equation (

23).

The numerical solution (

) satisfies

The numerical solution

converges when

, since the modulus of the coefficient in front of

is less than one

Denote by

the first half of the values of

, which are used as a numerical solution of equation (

14) on the interval

. The numerical solution

consists of

and has accuracy

, where

and

. The accuracy of

is

when the parameter

.

Example 2.

Consider the following boundary value ODE

The numerical results for the error and order of numerical solution

of equation (

17) and values of the parameter

and

are presented in

Table 3.

The experimental results in

Table 3 show that the error of the numerical method

is less than

. The results in

Table 3 represent a significant improvement over those in

Table 3 for the numerical method (

16). The graphs of the exact solution of equation (

17) on the interval

and numerical solution

are given in Figure 3.

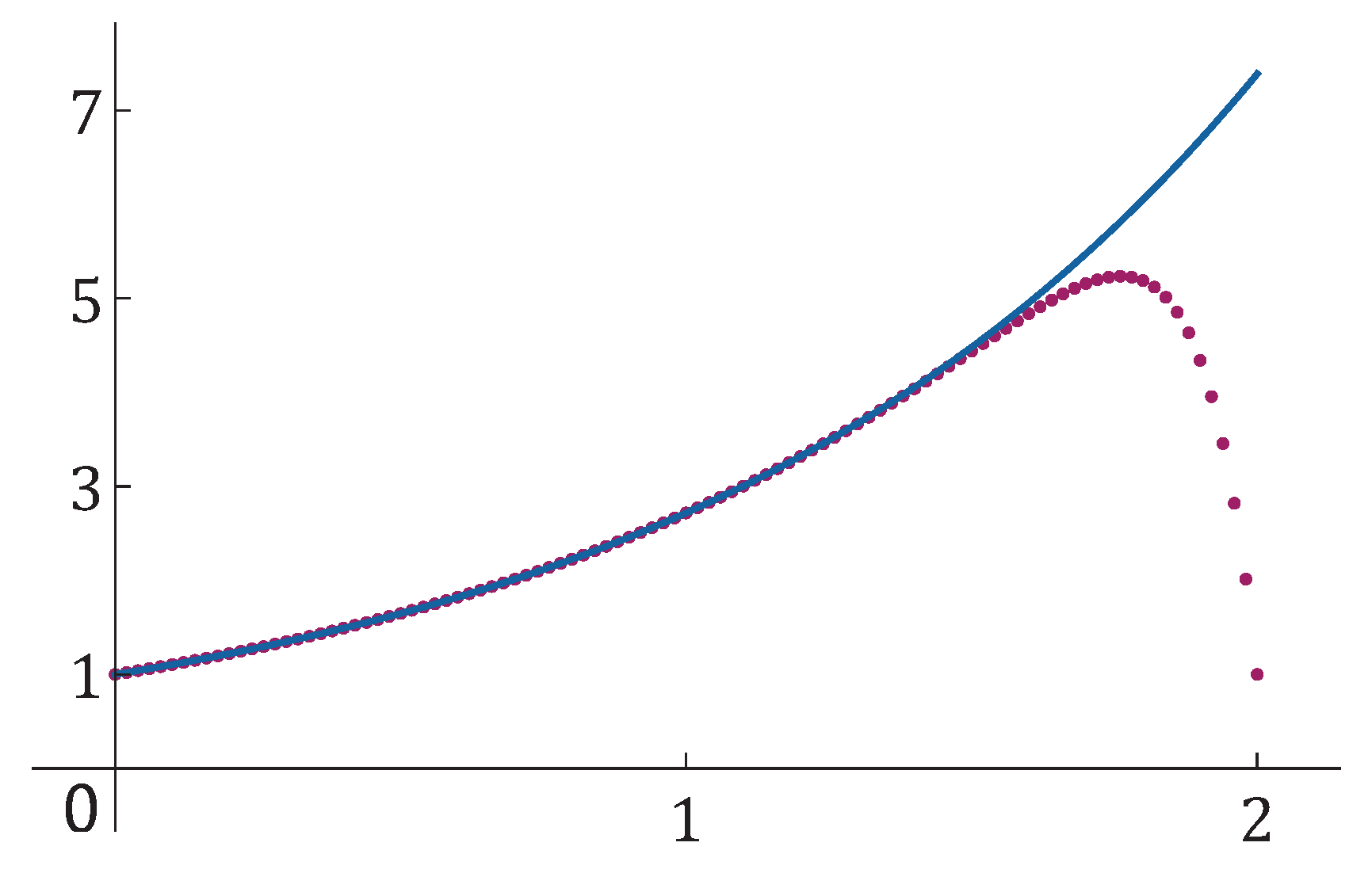

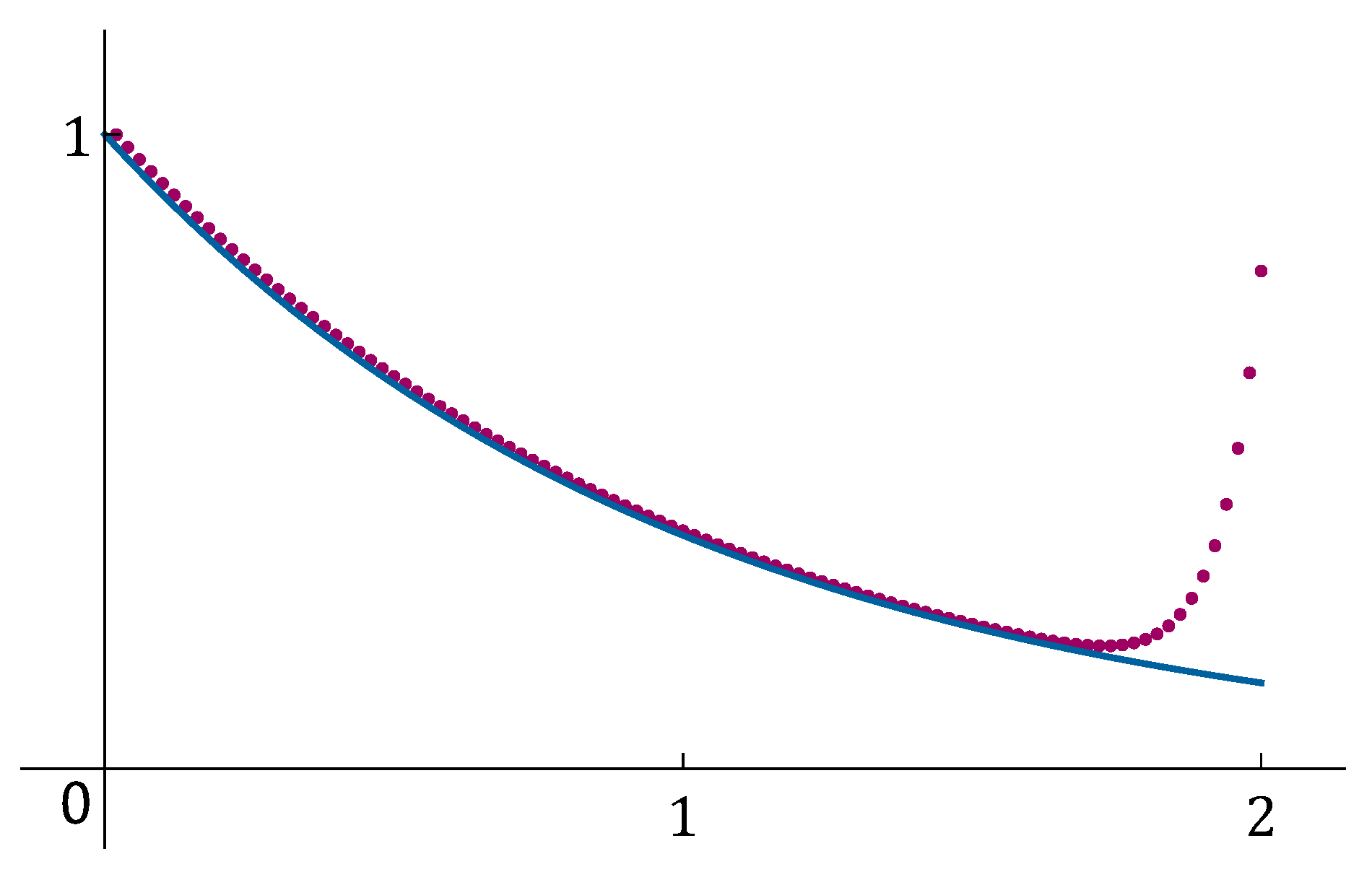

Figure 1.

Graphs of the exact solution of equation (

17) and of the numerical solution

for

and

.

Figure 1.

Graphs of the exact solution of equation (

17) and of the numerical solution

for

and

.

Example 3.

Consider the ordinary differential equation

for , and the corresponding boundary value ordinary differential equation

where

□

Equation (

26) has a solution

. The numerical solution of the initial value ordinary differential equation

which uses 2-point approximation (

24) is computed as

The numerical solution of the boundary value ordinary differential equation

which uses two-point approximation (

24) is computed as

Denote by

the numerical solution (

28) of equation (

26), and by

the first half of the values

of (

29), regarded as a numerical solution of equation (

26). The second column of

Table 4 contains the numerical results for the error and order of numerical solution

. The third and fourth columns contain the results for the error and order of numerical solution

.

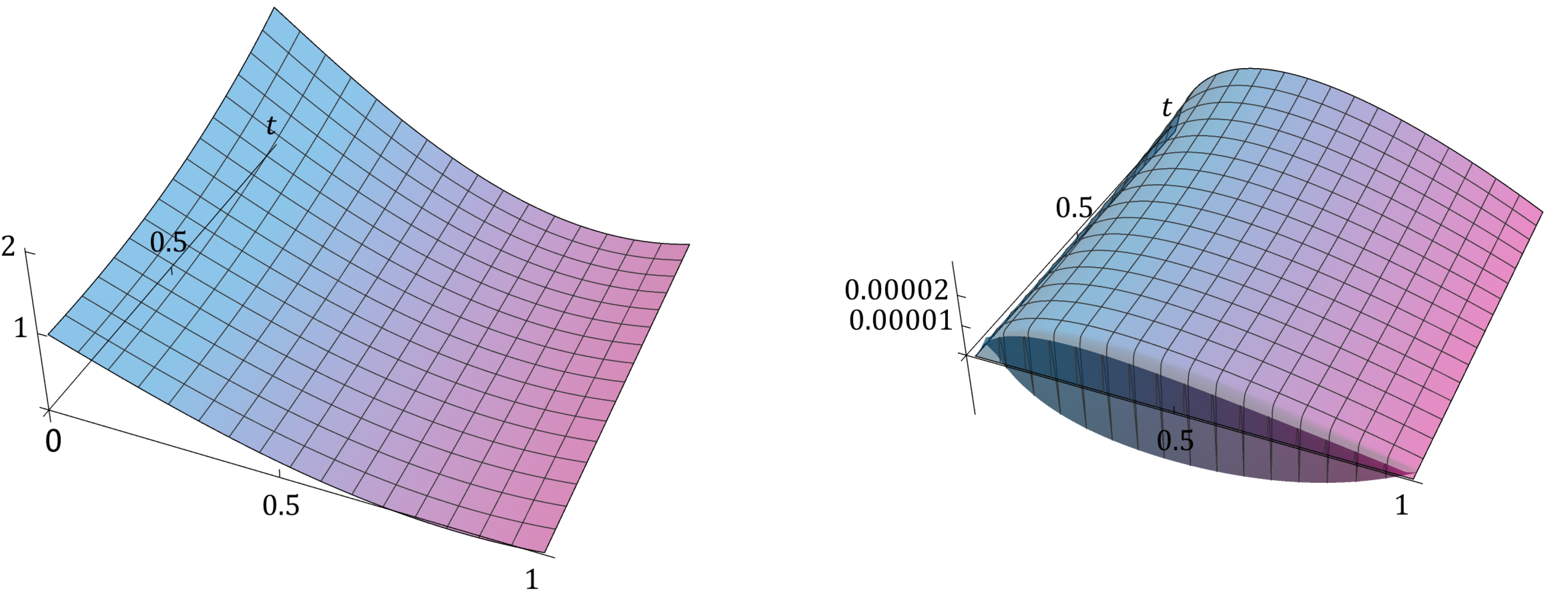

The graphs of the solution of equation (

26) and numerical solution (

29) of boundary value ordinary differential equation (

27) are given on

Figure 2. While the numerical results in the second column of

Table 4 show that the numerical solution

is of first order, its error is quite large, making this method impractical for real applications. The applied approach for computing the numerical solutions of the ordinary differential equations (

17) and (

26), which uses the numerical solutions of the boundary value problems (

25) and (

27), allows one to obtain solutions with an error smaller than

, which is sufficient for real-life problems.

Shifted approximations are employed for the solution of nonlinear ordinary differential equations. In order to derive the shifted approximation of (

11), we make use of the two-point approximation (

24).

When

we obtain

From (

11) and (

30) we obtain the shifted approximation of the first derivative

Consider the nonlinear ordinary differential equation

By approximating the first derivative at

with (

31) we obtain

The numerical solution of equation (

32) satisfies

and has initial conditions

The numerical solution (

33) is computed with

operations. The number of computations can be reduced to

in the following way [

1]: Let

The sequence

is computed recursively as

The sequence

and the numerical solution (

33) are computed with

operations by means of the following pseudocode.

Initialization:

Loop: for

n from 3 to

N do

The computational time of the numerical method (

33) is comparable to that of standard difference methods. The numerical solution (

33) has first-order accuracy, and second-order accuracy when

. When the parameter

, the numerical solution (

33) has an accuracy of order

.

Example 4.

Consider the following nonlinear ordinary differential equation

Equation (

34) has the solution

. The experimental results for the error and the order of the numerical solution (

33) of equation (

34) are presented in

Table 5.

5. Numerical Solutions of Fractional Differential Equations

Difference schemes are the main approach for the numerical solution of ordinary and partial fractional differential equations [

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58]. In paper [

1], we construct difference schemes for the two-term ordinary fractional differential equation and the fractional subdiffusion equation, which use approximations of the fractional derivative of order

, obtained in a manner similar to the construction of approximations (

6) and (

8). In this section, we study the difference schemes that use approximations (

6) and (

8). The convergence and order of the difference schemes based on the second-order asymptotic approximation (

8) are proved. Consider the two-term ordinary fractional differential equation

Suppose that

is an approximation of the fractional derivative that has an error term

. By substituting the fractional derivative

in equation (

45) with (

46), we obtain

The numerical solution of equation (

45) obtained using approximation (

46) is computed as

The initial values of

and

are computed using the L1 approximation, where

for

. Denote by

the numerical solution (

47) of equation (

45) that uses approximation (

6), where

, and by

the numerical solution that uses approximation (

8), where

.

Example 5.

Consider the following boundary value OFDE

Equation (

48) has a solution

. The numerical results for the error and order of numerical solutions

and

on the interval

are given in

Table 6 and

Table 7. The error of numerical solution

is smaller than the error of

because approximation (

6) has a smaller truncation error than (

8). The computational time of

is longer that that of

because on every iteration the weights of approximation (

6) are recomputed.

In the following, we prove the convergence of the numerical solution

and obtain an estimate for the error. Denote by

the error of

at the point

. The errors

and

are computed as

and

where

is the truncation error of the L1 approximation [

48]. Therefore, the numerical solution

has second-order accuracy for the first four iterations. Let

The sequence of the errors of numerical solution

, for

satisfies

Theorem 18.

Suppose that . Then

where and

Proof. We prove the statement by induction on

n. The estimate holds for

. Assume that (

49) holds for all

.

Applying the induction assumption

From Corollary 13 and Claim 17

Factoring out

we write

When

, the number

. Hence

To ensure

, it suffices to show that the coefficient is at most one:

From Corollary 13 and

, we obtain

Combining (

50) with the bound for

A, we obtain that when

estimate (

49) holds,

, completing the induction. □

In Theorem 18, we proved that when the parameter

numerical solution

has second-order accuracy. The proof of the convergence and order of

is similar. When the parameter

L is negative, the errors of the two numerical solutions become large. Experimental results for the error and order of

and

for negative values of the parameter

L are presented in

Table 8 and

Table 9. The errors of the numerical solutions in

Table 8 and

Table 9 are greater than

for

,

, and

.

The numerical methods

and

exhibit behavior similar to that of numerical method (

16) for equation (

14) To compute the numerical solution of equation (

48) with an accuracy not exceeding

, we use the approach from Example 2. We consider the corresponding boundary value fractional ordinary differential equation whose boundary condition coincides with the initial condition of equation (

48). Its numerical solution, obtained using the L1 approximation of the fractional derivative, is used as the numerical solution of equation (

48), and it has an accuracy of

, which is sufficient to solve both equations with an error smaller than

. The accuracy of the numerical solution can be improved by using higher-order approximations of the fractional derivative and boundary conditions at different points.

Example 6.

Consider the following boundary value OFDE

Let

. By approximating the fractional derivative using the L1 approximation we obtain

The numerical solution satisfies

where

. The numerical solution is computed with the system of

equations, which consists of equations (

52) and the boundary condition

. The coefficient matrix of the system has entries

on the diagonal above the main diagonal and is reduced to a lower-triangular form, using

row operations. The graphs of the exact solution of equation (

48) and numerical solution (

52) for

are given on

Figure 3. The experimental results for the error of the numerical solution (

52) are presented in

Table 10, where all errors are smaller than

. The results in

Table 8,

Table 9, and

Table 10 demonstrate that the numerical method (

52) for equation (

48) represents a significant improvement over

and

for negative values of the parameter

L.

The fractional subdiffusion equation is a fractional partial differential equation of the following form

where

L is the diffusion coefficient and has initial and boundary conditions

Let

and

, where

M and

N are integers. Denote

and by

the rectangular grid on

By substituting the fractional derivative at the point

with approximation (

8) and the second-order partial derivative with the second-order central difference formula, we obtain

where

and

are the coefficients of the error of approximation (

8) and

is the error of central difference approximation. Denote

.

The numerical solution

on row

m of the grid

is computed as

where

and has boundary conditions

.

The numerical solution for the first row is obtained using shifted approximation (

43)

Let

. The numerical solution

satisfies

and has boundary conditions boundary conditions

. The coefficient matrix for the system of equations of the first row is a diagonally dominant matrix of size

. The

(maximum) norm of a vector is the maximum of the absolute values of its elements and the

norm of a matrix is the maximum of the absolute row sums. The norm of the inverse coefficient matrix of (

54) is smaller than one [

49,

50]. Therefore, the numerical solution on the first row of the grid

has an error of order

. The numerical solution for the second row of the grid

is computed explicitly using the shifted approximation (

44)

The numerical solution satisfies

The error of the numerical solution in the second row of

is also of order

. The numerical solutions for the third and fourth rows are computed explicitly using the third order approximations

The errors for the third and fourth rows also have accuracy of

.

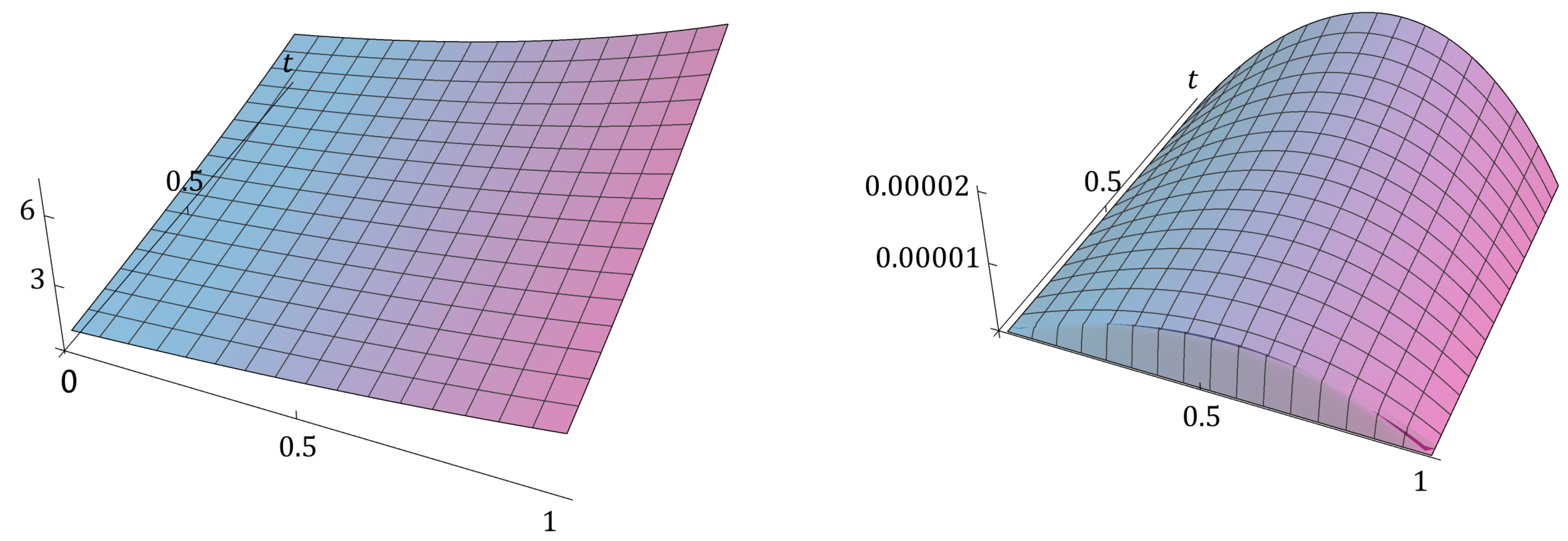

Example 7.

Consider the following fractional subdiffusion equation

Equation (

55) has the solution

The numerical results for the error and order of the difference scheme (

53) for the subdiffusion equation (

55) with

and

are presented in the third and fourth columns of

Table 11. The graphs for

,

,

, and

are shown in

Figure 4.

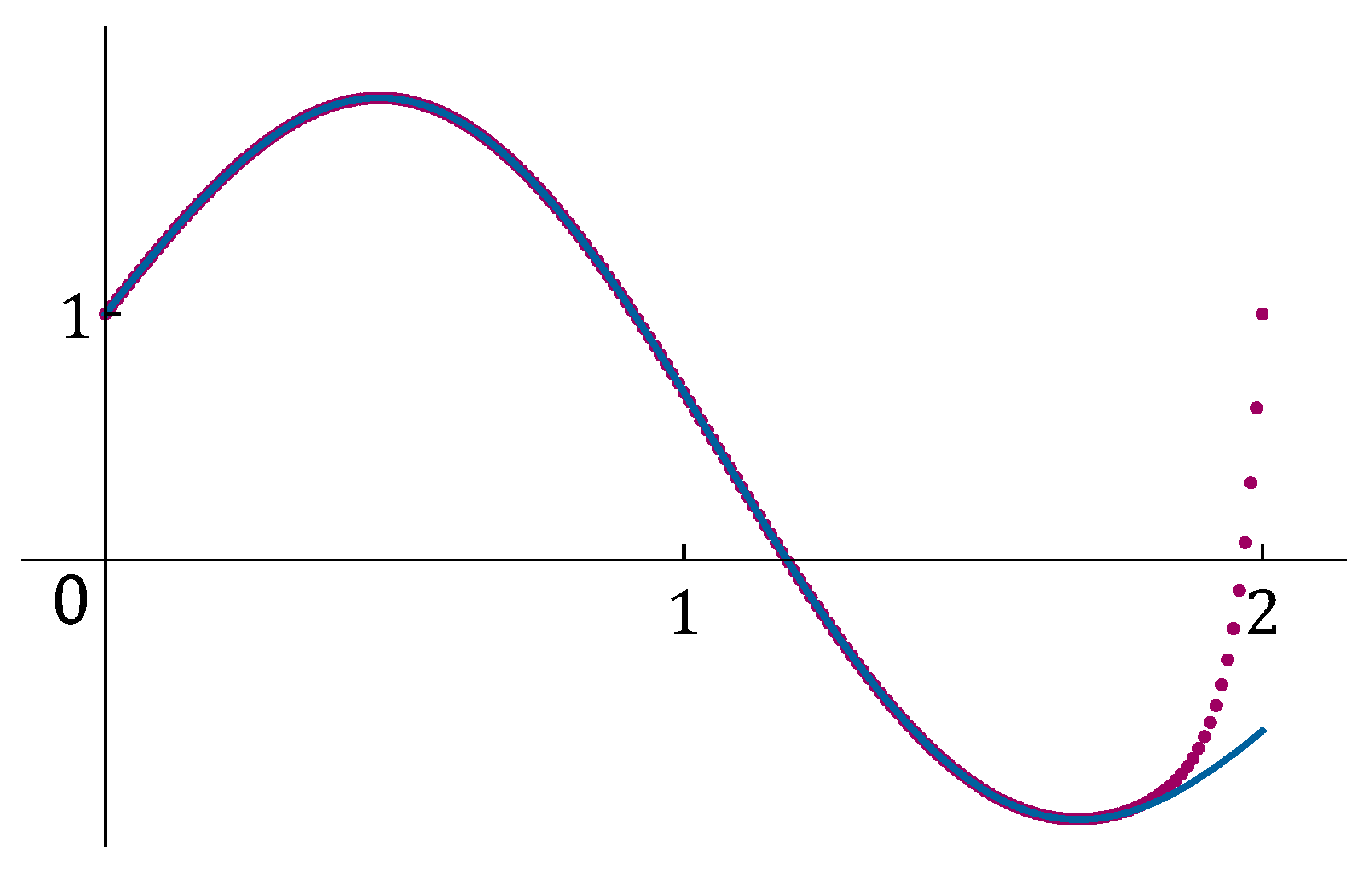

Example 8.

Consider the following fractional subdiffusion equation

Equation (

56) has the solution

. The results of the numerical experiments for the error and order of the difference scheme (

53) for the subdiffusion equation (

56) with

are presented in the second column of

Table 11. The graphs of numerical solution (

53) and its error for

,

,

, and

are shown in

Figure 5.

In the following, we prove that the difference scheme (

53) for the fractional subdiffusion equation converges with second-order accuracy. The errors

on the first four rows of the grid

have accuracy of

. Therefore

where

is a positive constant. The errors on row

of the grid

are the solutions of the system of equations

where

and

Denote

where the maximums are taken for all

and the coefficients

and

satisfy the bounds

Let

be an

-dimensional vector whose entries are the errors

of difference scheme (

53) on row

m of the grid

, and let

be the vector of truncation errors (

57). The system of equations for the errors of difference scheme (

53) in row

m of the grid

can be written in matrix form as

where

is a tridiagonal square matrix with nonzero entries

and

Theorem 19.

The errors of difference scheme (53) satisfy

for all , where

Proof. We prove the statement by induction. The estimate (

59) holds for

. Assume that (

59) holds for all rows

of the grid

. From formula (

57)

When

the gamma function satisfies

(see [

51]). Applying the induction assumption

where

. From Claim 17

When

C satisfies the conditions of the theorem, the two coefficients

and

are positive.Therefore

From (

58) the infinity norm of the inverse matrix satisfies [

49,

50]

Hence

The error estimate (

59) holds for the

m-th row of the grid

, completing the induction. □