Submitted:

20 October 2025

Posted:

21 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

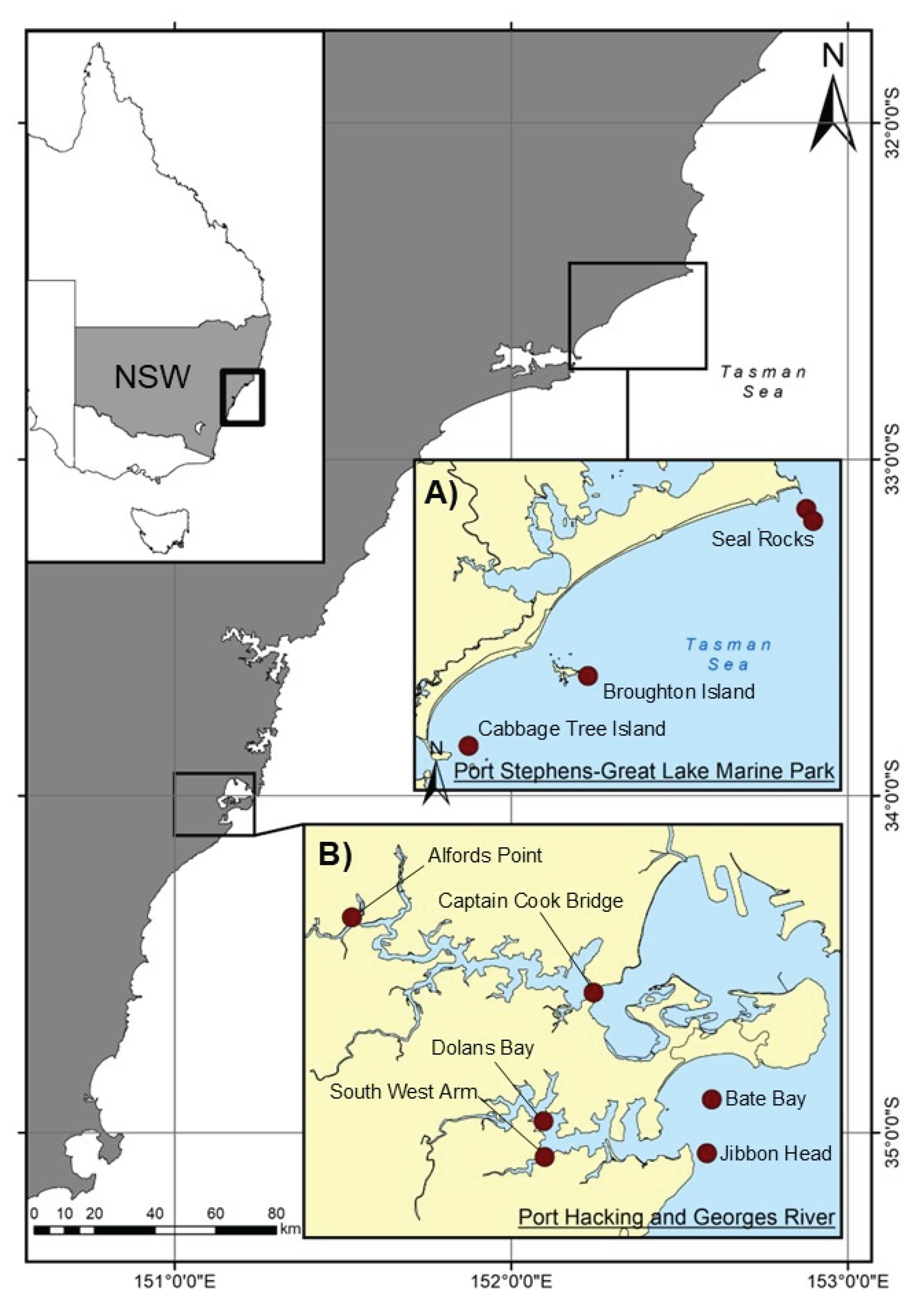

2.1. Capture of Experimental Animals

2.2. Treatment, Release and Monitoring

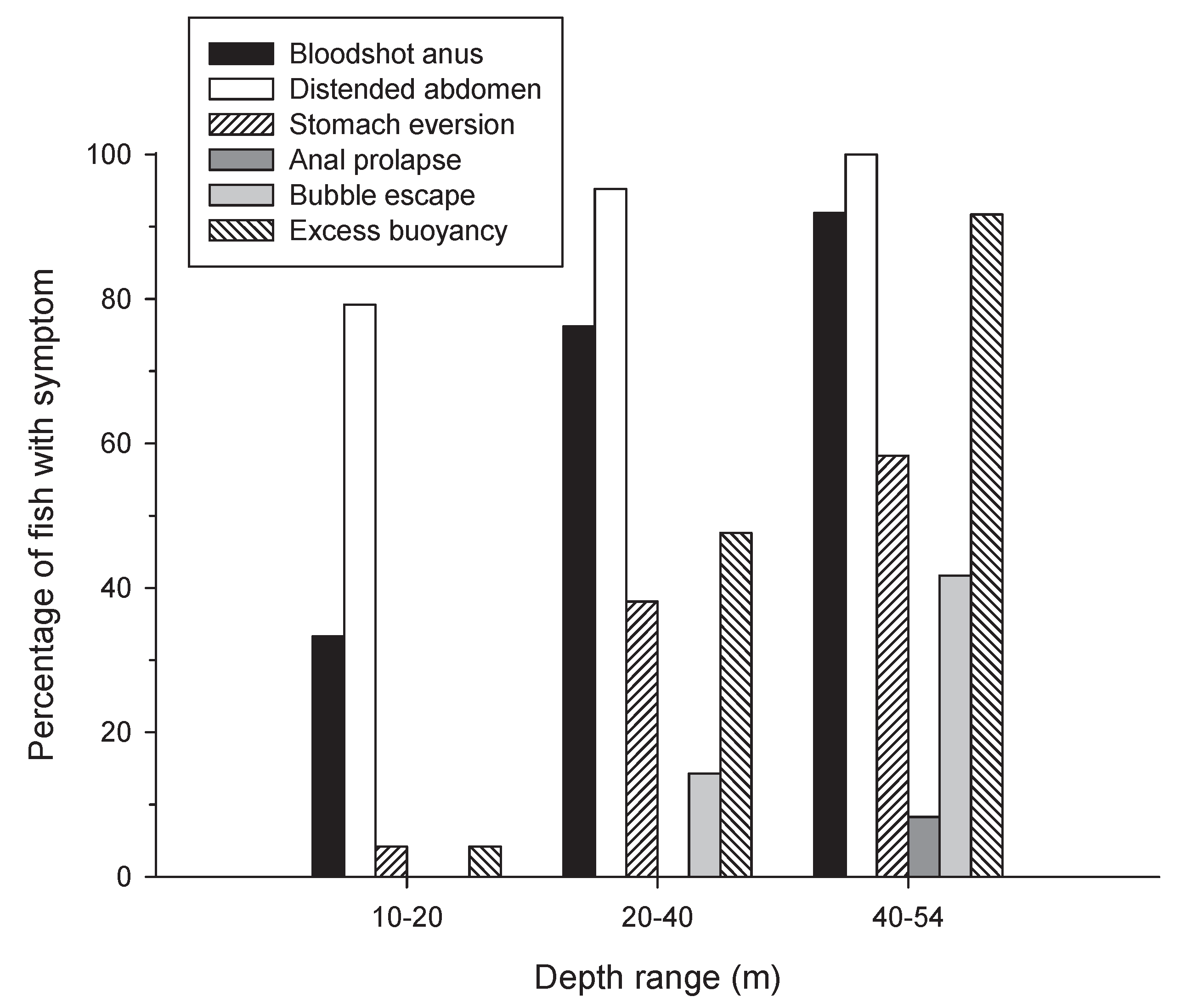

2.3. Barotrauma Symptoms

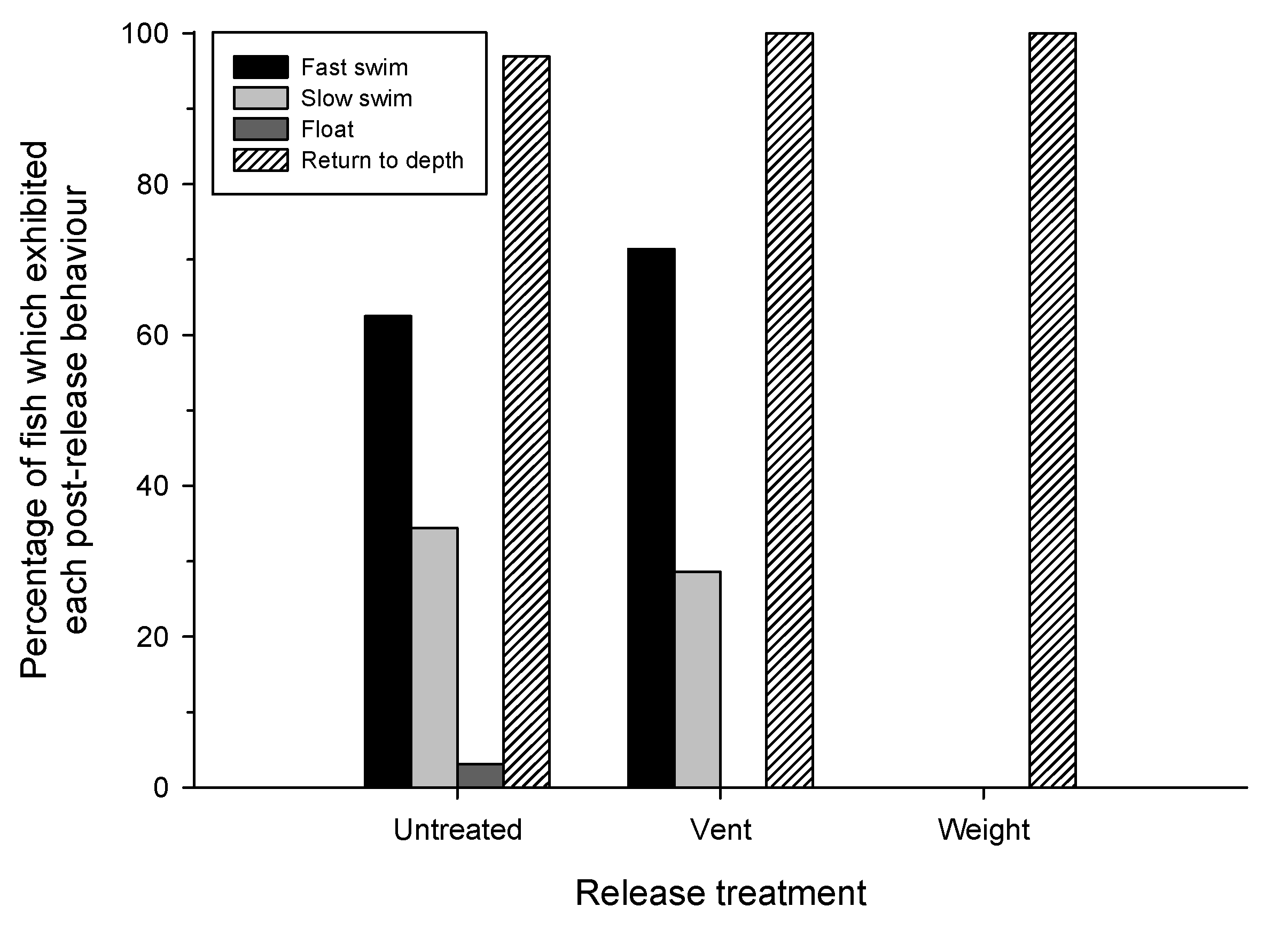

2.4. Immediate Post-Release Behavior

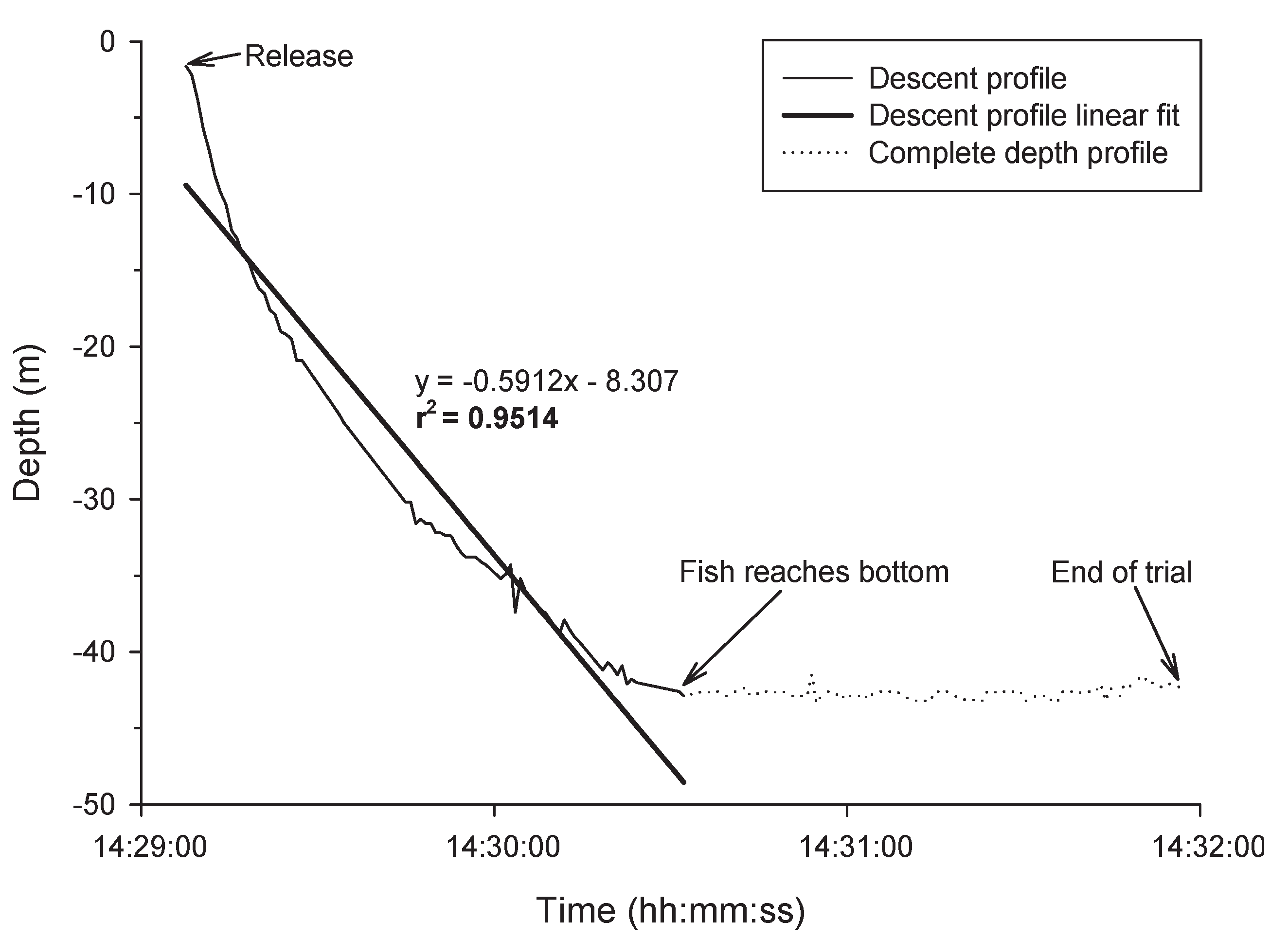

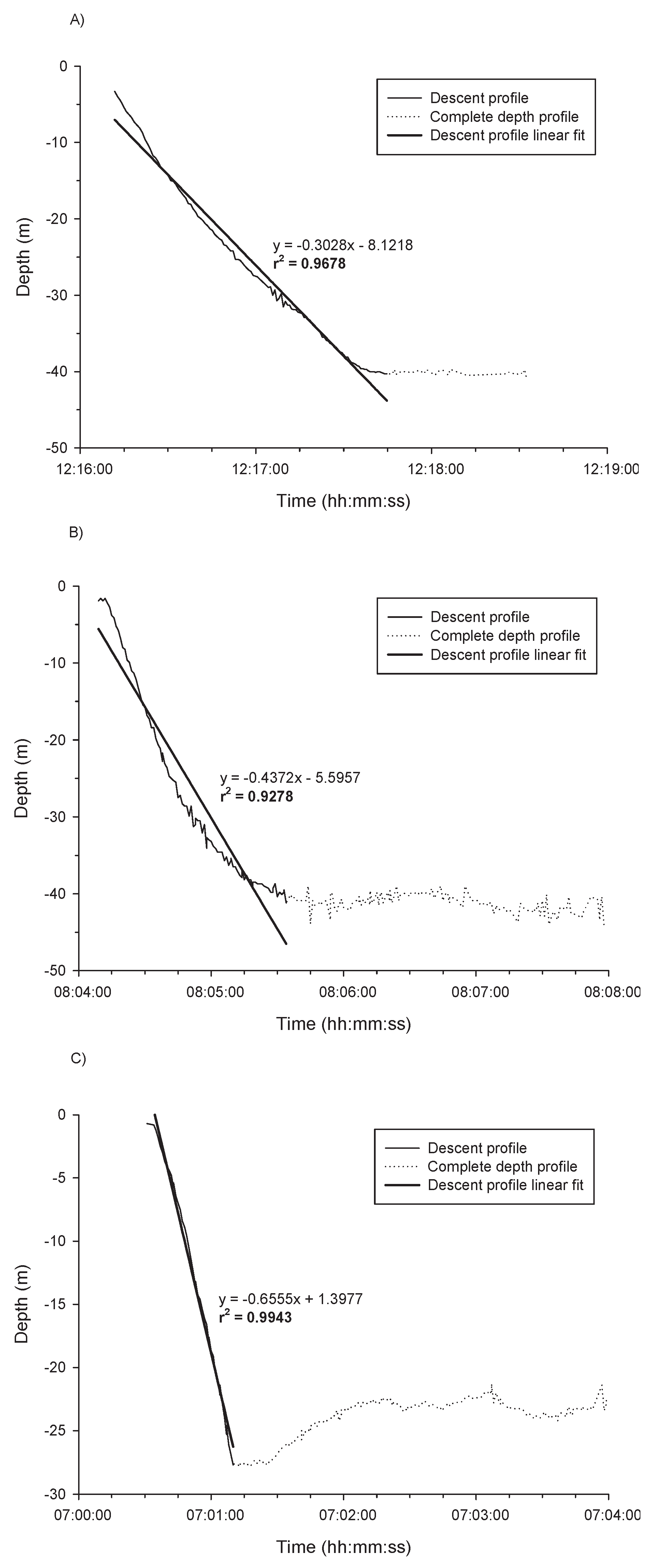

2.5. Post-Release Return to Depth Profiles and Descent Rates

3. Results

3.1. Barotrauma Symptoms

3.2. Release Treatments

3.3. Immediate Post-Release Behavior

3.4. Post-Release Return to Depth Profiles

3.5. Post-Release Descent Rates and Variability in Descent

4. Discussion

4.1. Symptoms

4.2. Post-Release Behavior and Depth Choice

4.3. Conclusions and Recommendations

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Strand E., Jørgensen C., Huse G. 2005. Modelling buoyancy regulation in fishes with swimbladders: bioenergetics and behavior. Ecol. Modell. 185(2-4): 309–327. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J. M., Rowland, A. J., Stewart, J., and Gill, H. S. (2016). Discovery of a specialised anatomical structure in some physoclistous carangid fishes which permits rapid ascent without barotrauma. Marine biology, 163(8), 169. [CrossRef]

- Rummer, J.L., Bennett, W.A., 2005. Physiological effects of swim bladder overexpansion and catastrophic decompression on red snapper. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 134, 1457–1470. [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, E.T., Lowe, C.G., 2008. The effects of barotrauma on the catch-and-release survival of southern California nearshore and shelf rockfish (Scorpaenidae Sebastes spp.). Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 65, 1286–1296. [CrossRef]

- Pribyl, A.L., Schreck, C.B., Kent, M.L., Parker, S.J., 2009. The differential response to decompression of three species of nearshore Pacific rockfish. N. Am. J. Fish. Manage. 9, 1479–1486. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.M., Stewart, J., Collins, D., 2019a. Experimental hyperbaric chamber trials reveal high resilience to barotrauma in Australian snapper (Chrysophrys auratus). Fish. Res. 212, 172–182. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.M., Stewart, J., Collins, D., 2019b. Simulated catch-and-release using experimental hyperbaric chamber trials reveal high levels of delayed mortality due to barotrauma in mulloway (Argyrosomus japonicus). J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 516,89–102. [CrossRef]

- Hannah, R.W., Matteson, K.M., 2007. Behavior of nine species of Pacific rockfish after hook-and-line capture recompression, and release. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 136, 24–33. [CrossRef]

- Hannah, R.W., Parker, S.J., Matteson, K.M., 2008. Escaping the surface: the effects of capture depth on submergence success of surface-released Pacific rockfish. North Am. J. Fish. Manage. 28, 694–700. [CrossRef]

- Diamond, S. L. and M. D. Campbell (2009). Linking “sink or swim” indicators to delayed mortality in red snapper by using a condition index. Marine and Coastal fisheries: Dynamics, Management, and Ecosystem Science 1: 107-120. [CrossRef]

- Rodgveller, C.J., Malecha, P.W., Lunsford, C.R., 2017. Long-term Survival and Observable Healing of Two Deepwater Rockfishes, Sebastes, after Barotrauma and Subsequent Recompression in Pressure Tanks. U.S. Dep. Commer., NOAA Tech. Memo. NMFSAFSC 359 37 p.

- Wilde G.R. 2009. Does venting promote survival of released fish? Fisheries, 34(1): 20–28. [CrossRef]

- Brown, I. S., McLennan, M., Mayer, D., Campbell, M., Kirkwood, J., Butcher, A., Halliday, I., Mapleston, A., Welch, D., Begg, G. A. and Sawynok, B. (2010). An improved technique for estimating short-term survival of released line-caught fish, and an application comparing barotrauma-relief methods in red emperor (Lutjanus sebae Cuvier 1816). Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 385: 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Gravel M.A., Cooke S.J. 2008. Severity of barotrauma influences the physiological status, postrelease behavior, and fate of tournament-caught smallmouth bass. N. Am. J. Fish. Manag. 28(2): 607–617. [CrossRef]

- Pribyl, A.L., Schreck, C.B., Kent, M.L., Kelley, K. M. and Parker, S.J. 2012. Recovery potential of black rockfish, Sebastes melanops Girard, recompressed following barotrauma. Journal of Fish Diseases 35: 275–286. [CrossRef]

- McLennan, M. F., Campbell, M. J., and Sumpton, W. D. (2014). Surviving the effects of barotrauma: assessing treatment options and a ‘natural’remedy to enhance the release survival of line caught pink snapper (Pagrus auratus). Fisheries management and ecology, 21(4), 330-337. [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, A. and Bohnsack, J. A. (2005). A review of catch-and-release angling mortality with implications for no-take reserves. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries 15: 129-154. [CrossRef]

- St John, J. and C. J. Syers (2005). “Mortality of the demersal West Australian dhufish, Glaucosoma hebraicum (Richardson 1845) following catch and release: The influence of capture depth, venting and hook type.” Fisheries Research 76(1): 106-116. [CrossRef]

- Burns, K. M., Koenig, C. C. and Coleman, F. C. (2002) Evaluation of multiple factors involved in release mortality of undersized red grouper, gag, red snapper, and vermilion snapper. Mote Marine Laboratory Technical Report No. 790. 53 pp.

- Eberts R.L., Zak M.A., Manzon R.G., Somers C.M. 2018. Walleye responses to barotrauma relief treatments for catch-and-release angling: short-term changes to condition and behavior. J. Fish Wildl. Manag. 9(2): 415–430. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J. (2008). Capture depth related mortality of discarded snapper (Pagrus auratus) and implications for management. Fisheries Research 90(1-3): 289-295. [CrossRef]

- Lenanton, R., Wise, B., St John, J., Keay, I., Gaughan, D., 2009. Maximising Survival of Released Undersize West Coast Reef Fish. Final FRDC Report (Project 2000/194). Department of Fisheries, North Beach, Western Australia, Australia, 126 pp.

- Butcher, P. A., Broadhurst, M. K., Hall, K. C., Cullis, B. R. and Raidal, S. R. (2012). Assessing barotrauma among angled snapper (Pagrus auratus) and the utility of release methods. Fisheries Research 127: 49-55. [CrossRef]

- Madden, J. C., L. LaRochelle, D. Burton, S. C. Danylchuk, A. J.Danylchuk, and S. J. Cooke. 2024. “Biologgers Reveal Unanticipated Issues With Descending Angled Walleye With Barotrauma Symptoms.” Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 81, no. 2: 212–222. [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, M. R., Arlinghaus, R., Hanson, K. C. & Cooke, S. J. (2008). Enhancing catch and release science with biotelemetry. Fish and Fisheries 9, 79–105. [CrossRef]

- Curtis J.M., Johnson M.W., Diamond S.L., Stunz G.W. 2015. Quantifying delayed mortality from barotrauma impairment in discarded red snapper using acoustic telemetry. Mar. Coast. Fish. 7(1): 434–449. [CrossRef]

- Wegner N.C., Portner E.J., Nguyen D.T., Bellquist L., Nosal A.P., Pribyl A.L., et al. 2021. Post-release survival and prolonged sublethal effects of capture and barotrauma on deep-dwelling rockfishes (genus Sebastes): implications for fish management and conservation. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 78(9): 3230–3244. [CrossRef]

- Butcher, P.A., Broadhurst, M.K., Cullis, B.R., Raidal, S.R., 2013. Physical damage, behavior and post-release mortality of Argyrosomus japonicus after barotrauma and treatment. Afr. J. Mar. Sci. 35 (4), 511–521. [CrossRef]

- Dolton H. R., Jackson A. L., Drumm A., Harding L., Ó Maoiléidigh N., Maxwell H., et al. (2022). Short-term behavioral responses of Atlantic bluefin tuna to catch-and-release fishing. Conserv. Physiol. 10, coac060. [CrossRef]

- Skomal, G.B. (2007) Evaluating the physiological and physical consequences of capture on post-release survivorship in large pelagic fishes. Fisheries Management and Ecology 14, 81–89. [CrossRef]

- Bridger, C.J. and Booth, R.K. (2003) The effects of biotelemetry transmitter presence and attachment procedures on fish physiology and behavior. Reviews in Fisheries Science 11, 13–34. [CrossRef]

- Pollock, K.H. and Pine W.E., III (2007) The design and analysis of field studies to estimate catch-and-release mortality. Fisheries Management and Ecology 14, 123–130. [CrossRef]

- Kailola, P.J., Williams, M.J., Stewart, P.C., Reichelt, R.E., McNee, A., Grieve, C., 1993. Australian Fisheries Resources. Commonwealth of Australia (Bureau of Resource Sciences), Canberra, Australia, 422 pp.

- Rogers, T., Stewart, J., Bell, J., Garland, A., Jackson, G., Fisher, E. 2024. Snapper Chrysophrys auratus, in Roelofs, A, Piddocke, T, et al. (eds) 2024, Status of Australian Fish Stocks Reports 2024, Fisheries Research and Development Corporation, Canberra.

- West, L. D., Stark, K. E., Murphy, J. J., Lyle, J. M., and Ochwada-Doyle, F. A. (2015). Survey of recreational fishing in New South Wales and the ACT, 2013/14.

- Hughes, J. M., and Stewart, J. (2013). Assessment of barotrauma and its mitigation measures on the behavior and survival of snapper and mulloway. NSW DPI—Fisheries Final Report Series, (138).

- Ferter, K, Weltersbach, MS, Humborstad, OB, Fjelldal, PG, Sambraus, F, Strehlow, HV, Vølstad, JH. (2015) Dive to survive: effects of capture depth on barotrauma and post-release survival of Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) in recreational fisheries. ICES Journal of Marine Science 72(8): 2467–2481. [CrossRef]

- Edgar, G. J. (2008a). Pagrus auratus. Reef Life Survey. Australian Marine Life, New Holland, Sydney. Available at: https://reeflifesurvey.com/species/pagrus-auratus/.

- Harasti D, Williams J, Mitchell E, Lindfield S, Jordan A (2018) Increase in Relative Abundance and Size of Snapper Chrysophrys auratus Within Partially-Protected and No-Take Areas in a Temperate Marine Protected Area. Front. Mar. Sci. 5: 208. [CrossRef]

- Williams J, Jordan A, Harasti D, Davies P, Ingleton T (2019) Taking a deeper look: Quantifying the differences in fish assemblages between shallow and mesophotic temperate rocky reefs. PLoS ONE 14(3): e0206778. [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.J., McElderry, H.I., Rankin, P.S., Hannah, R.W., 2006. Buoyancy regulation and barotrauma in two species of nearshore rockfish. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 135, 1213–1223. [CrossRef]

- Overton, A. S., C. S. Manooch, J. W. Smith, and K. Brennan. 2008. Interactions between adult migratory striped bass (Morone saxatilis) and their prey during winter off the Virginia and North Carolina Atlantic coast from 1994 through 2007. U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service Fishery Bulletin 106:174.

- Haggarty D.R. 2019. A review of the use of recompression devices as a tool for reducing the effects of barotrauma on rockfishes in British Columbia. Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat.

- Danylchuk, S.E., Danylchuk, A.J., Cooke, S.J., Goldberg, T.L., Koppelman, J., Philipp, D.P., 2007. Effects of recreational angling on the post-release behavior and predation of bonefish (Albula vulpes): the role of equilibrium status at the time of release. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 346, 127–133. [CrossRef]

- Eberts, R.L. and Somers, C.M. (2017), Venting and Descending Provide Equivocal Benefits for Catch-and-Release Survival: Study Design Influences Effectiveness More than Barotrauma Relief Method. North American Journal of Fisheries Management, 37: 612-623. [CrossRef]

- Rankin P. S., Hannah R. W., Blume M. T., Miller-Morgan T. J., Heidel J. R. 2017. Delayed effects of capture-induced barotrauma on physical condition and behavioral competency of recompressed yelloweye rockfish, Sebastes ruberrimus. Fisheries Research, 186: 258–268. [CrossRef]

- Nichol, D. G. and E. A. Chilton (2006). Recuperation and behavior of Pacific cod after barotrauma. ICES Journal of Marine Science: Journal du Conseil 63(1): 83-94. [CrossRef]

- Van Der Kooij, J., Righton, D., Strand, E., Michalsen, K., Thorsteinsson, V., Svedang, H., Neat, F. C. & Neuenfeldt, S. (2007). Life under pressure: insights from electronic data-storage tags into cod swimbladder function. ICES Journal of Marine Science 64, 1293–1301. [CrossRef]

- Burns, K. M. and Restrepo, V. (2002). Survival of reef fish after rapid depressurization: field and laboratory studies. American Fisheries Society Symposium 30: 148-151.

- Rudershausen, P.J., Buckel, J.A., Williams, E.H., 2007. Discard composition and release fate in the snapper and grouper commercial hook-and-line fishery in North Carolina, USA. Fish. Manage. Ecol. 14, 103–113. [CrossRef]

| Depth range (m) | n | Mean FL (cm) ± SE (range) |

Mean fight duration (min) ± SE (range) | Mean surface interval (min) ± SE (range) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10–20 | 24 | 28.1 ± 3.4 (14.2–61.5) | 1.3 ± 0.3 (0.2–4.0) | 3.7 ± 0.6 (0.5–12.0) |

| 20–40 | 21 | 47.3 ± 2.7 (19.0–68.6) | 2.7 ± 0.3 (1.0–5.0) | 3.1 ± 0.7 (0.5–13.0) |

| >40 | 12 | 32.8 ± 2.4 (20.5–49.1) | 1.3 ± 0.1 (1.0–2.0) | 5.6 ± 1.1 (2.0–15.0) |

| Overall | 57 | 36.2 ± 2.1 (14.2–68.6) | 1.8 ± 0.2 (0.2–5.0) | 3.9 ± 0.4 (0.5–15.0) |

| n | Mean depth (m) ± SE (range) | Mean FL (cm) ± SE (range) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated | 32 | 23.4 ± 2.8 (10.0–49.9) | 29.6 ± 2.8 (14.2–68.6) | |

| Vented | 14 | 34.3 ± 3.6 (14.0–54.0) | 41.0 ± 3.6 (20.5–61.5) | |

| Release weight | 11 | 31.4 ± 2.5 (16.0–41.0) | 49.2 ± 2.9 (32.5–61.0) | |

| Overall | 57 | 27.6 ± 1.6 (10.0–54.0) | 36.2 ± 2.2 (14.2–68.6) |

| Treatment | n | Descent rate (m/min) ± SE (range) | Descent variability (r2) ± SE (range) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated | 31* | 14.3 ± 1.8 (4.0–43.6) | 0.95 ± 0.01 (0.80–0.99) | |

| Vented | 14 | 16.2 ± 2.6 (5.8–33.1) | 0.92 ± 0.02 (0.80–0.99) | |

| Release weight | 11 | 69.7 ± 11.2 (37.0–135.8)** | 0.99 ± 0.00 (0.96–0.99)** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).