Submitted:

19 October 2025

Posted:

21 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background

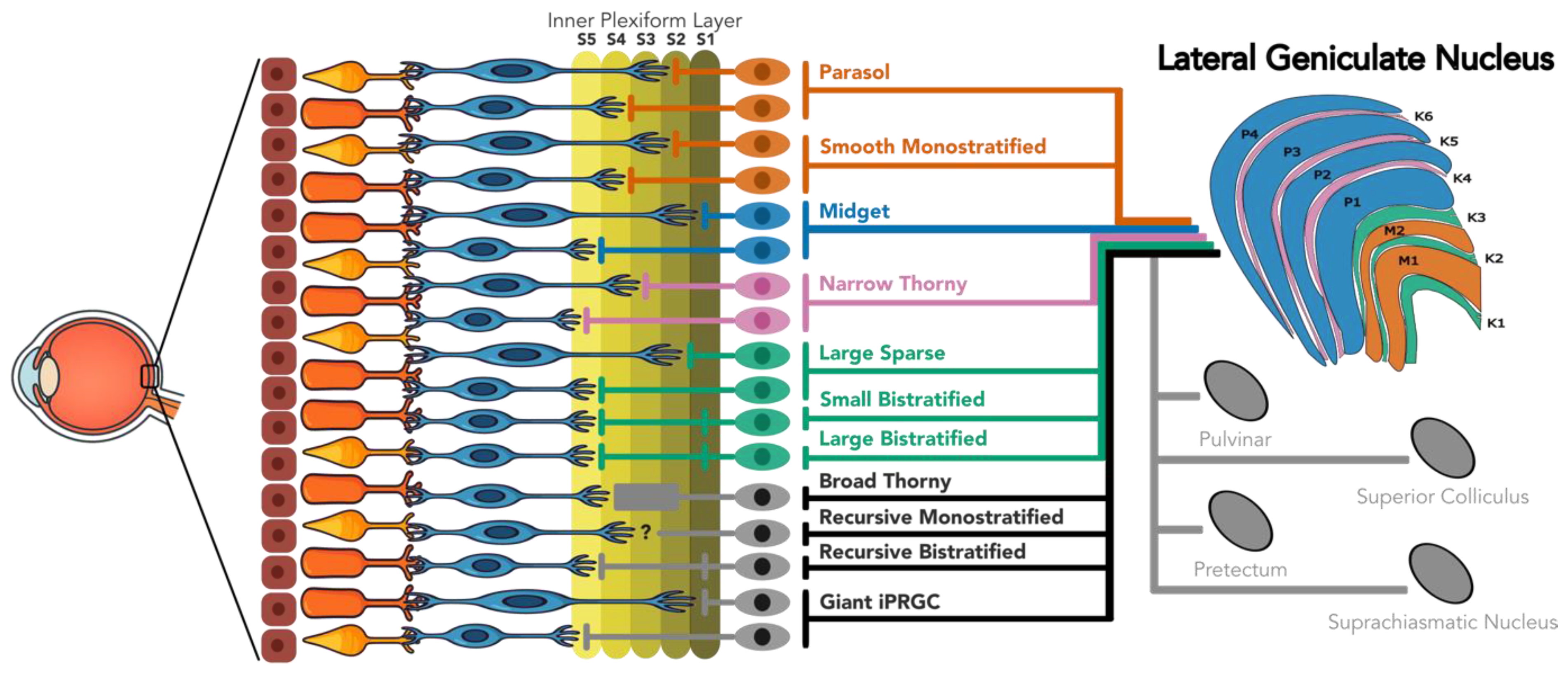

Anatomically and physiologically classifying RGC types

2.1. LGN – the Primary Central Projection for Conscious Vision

2.2. LGN – the Diverse Properties of K Cells

3. Magnocellular Projecting RGCs

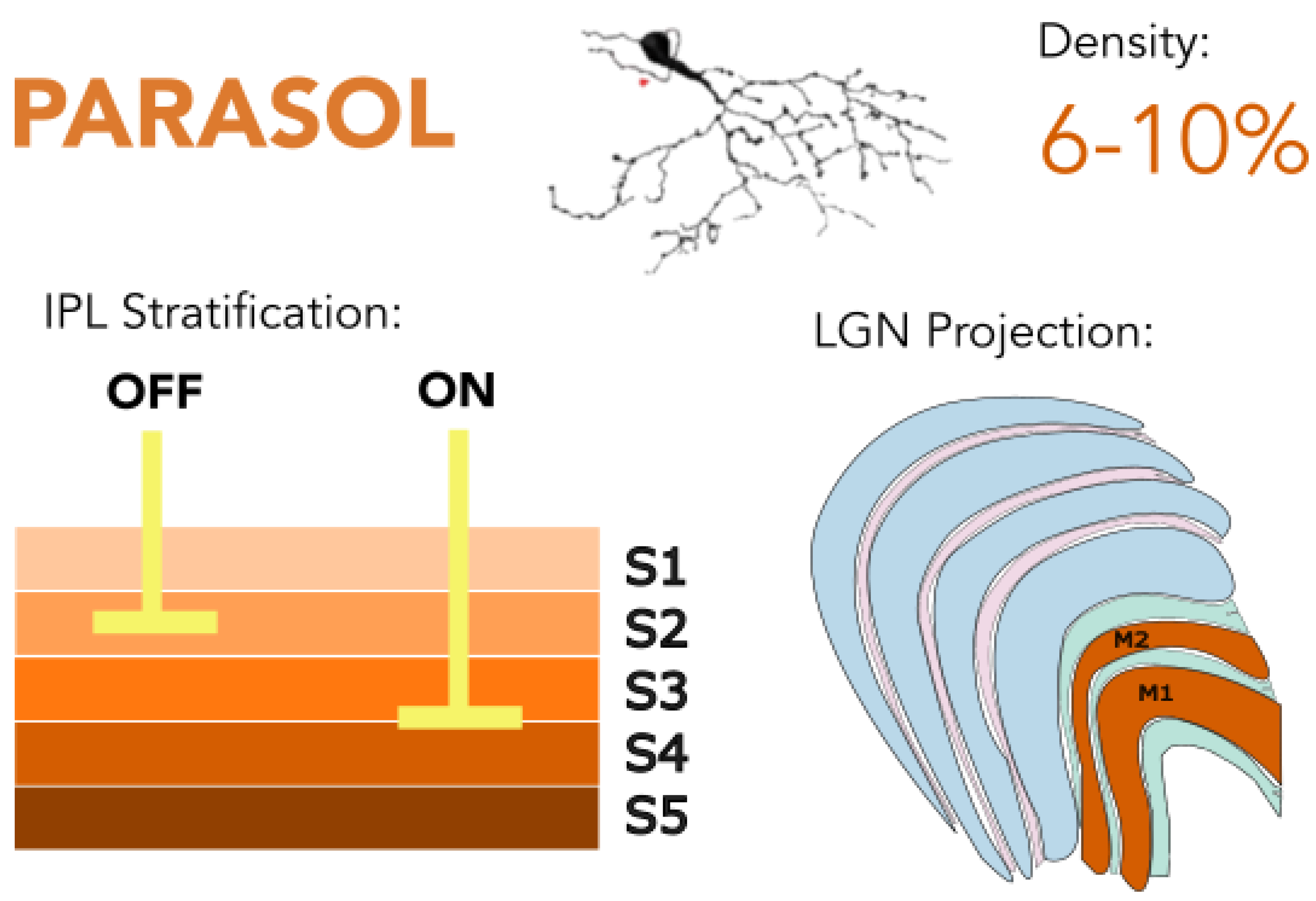

3.1. Parasol RGCs

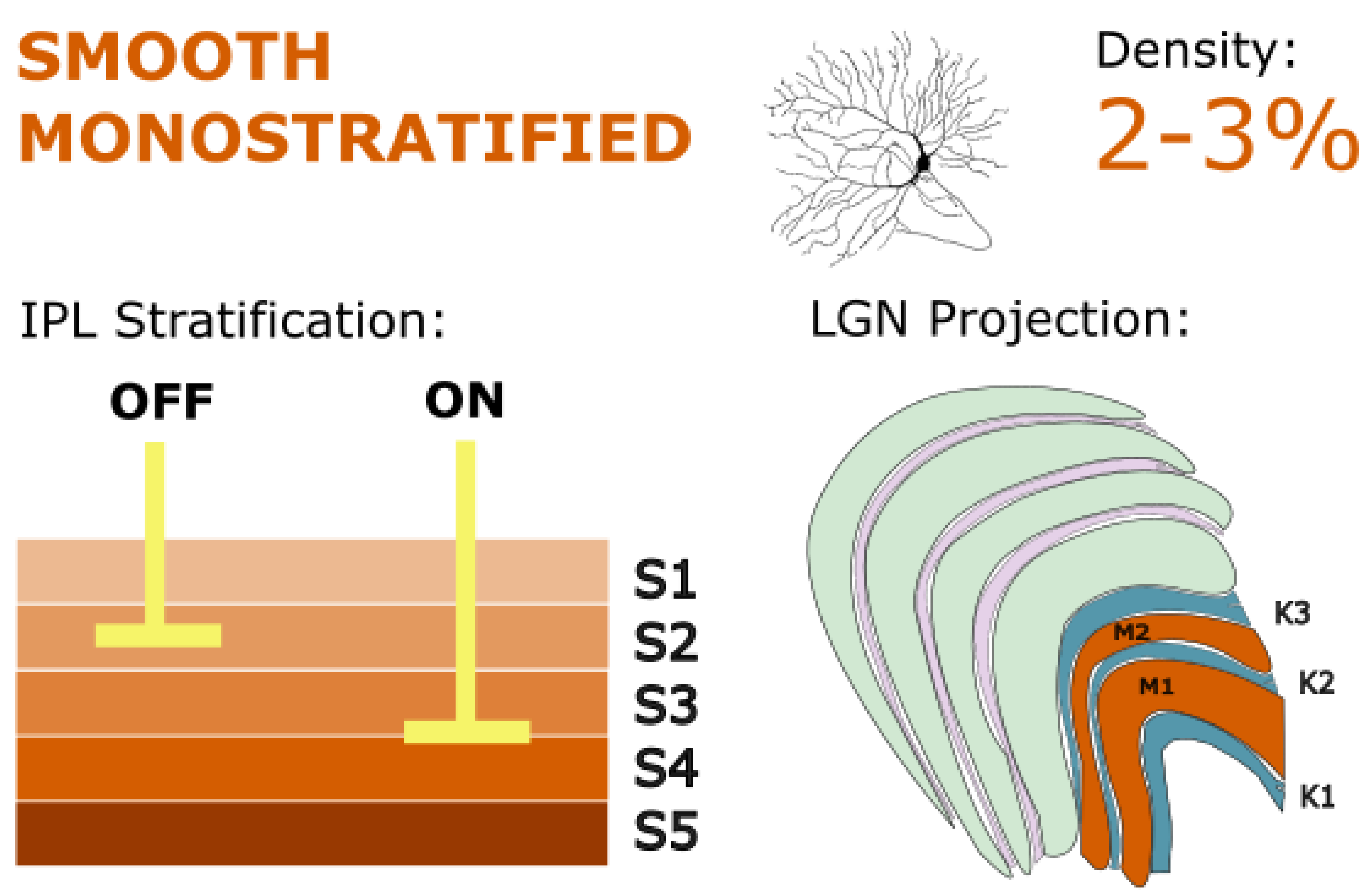

3.2. Smooth Monostratified RGCs

4. Parvocellular Projecting RGCs

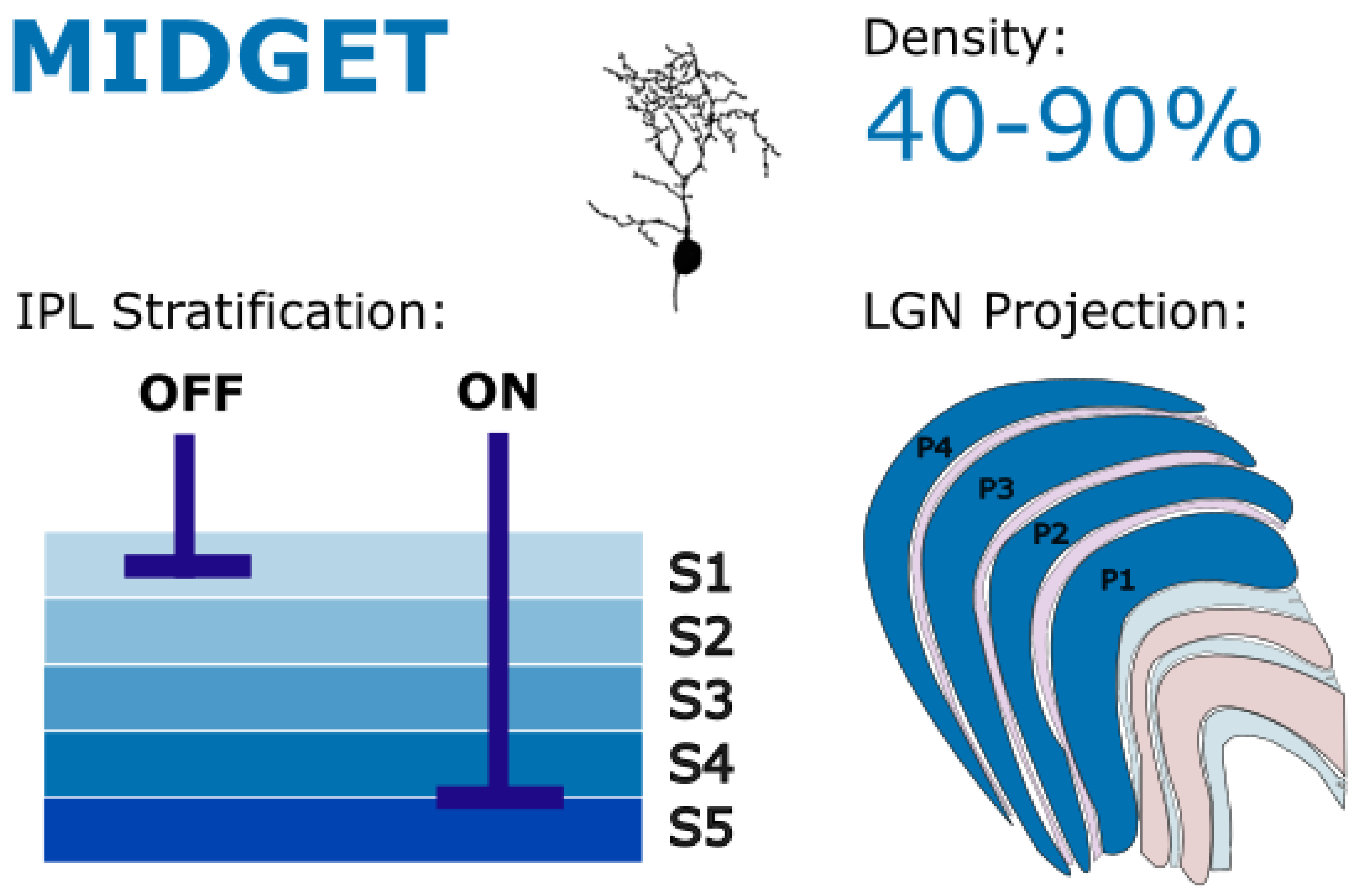

4.1. Midget RGCs

5. Koniocellular Projecting RGCs

5.1. Small Bistratified RGCs

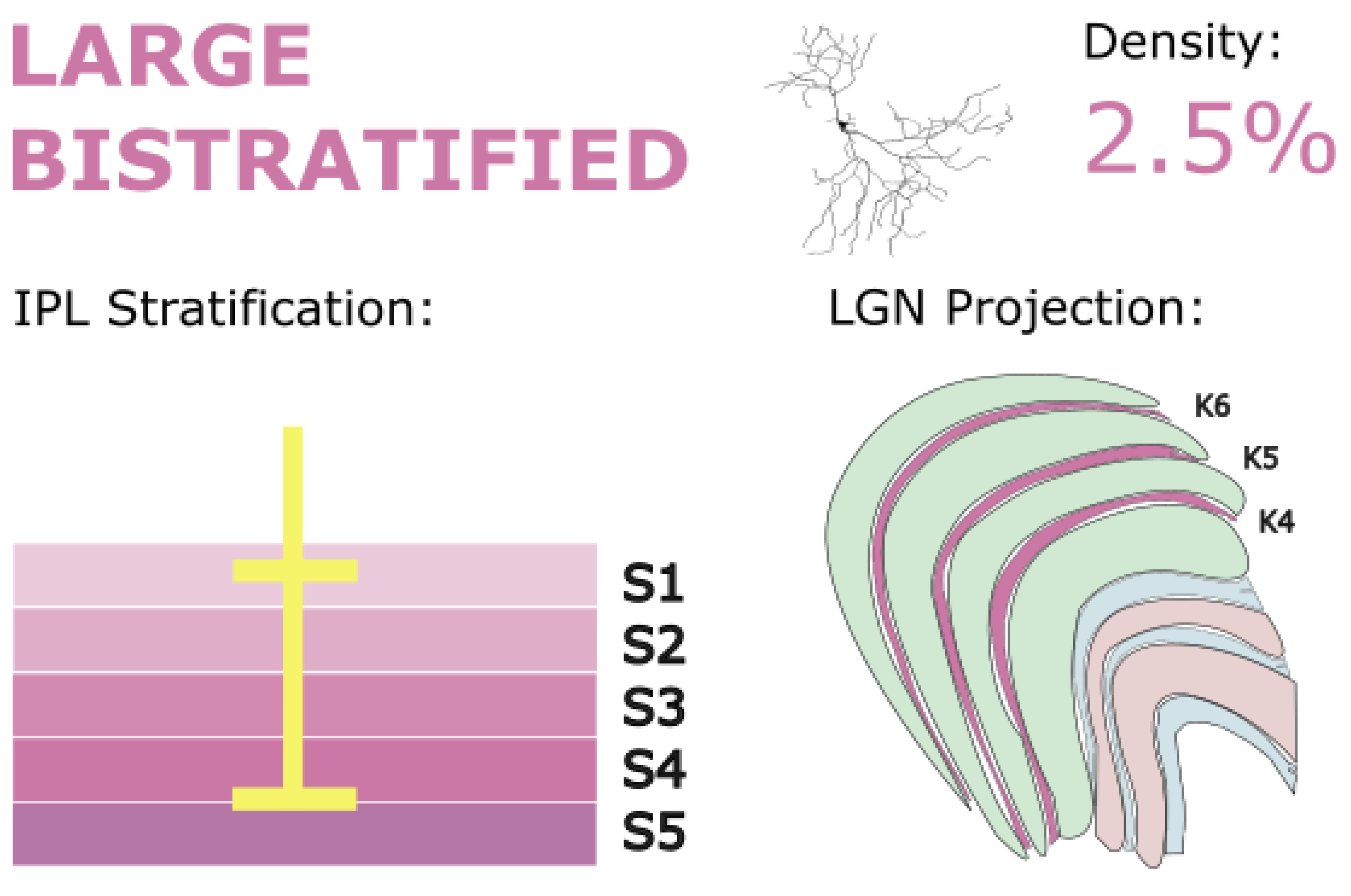

5.2. Large Bistratified RGCs

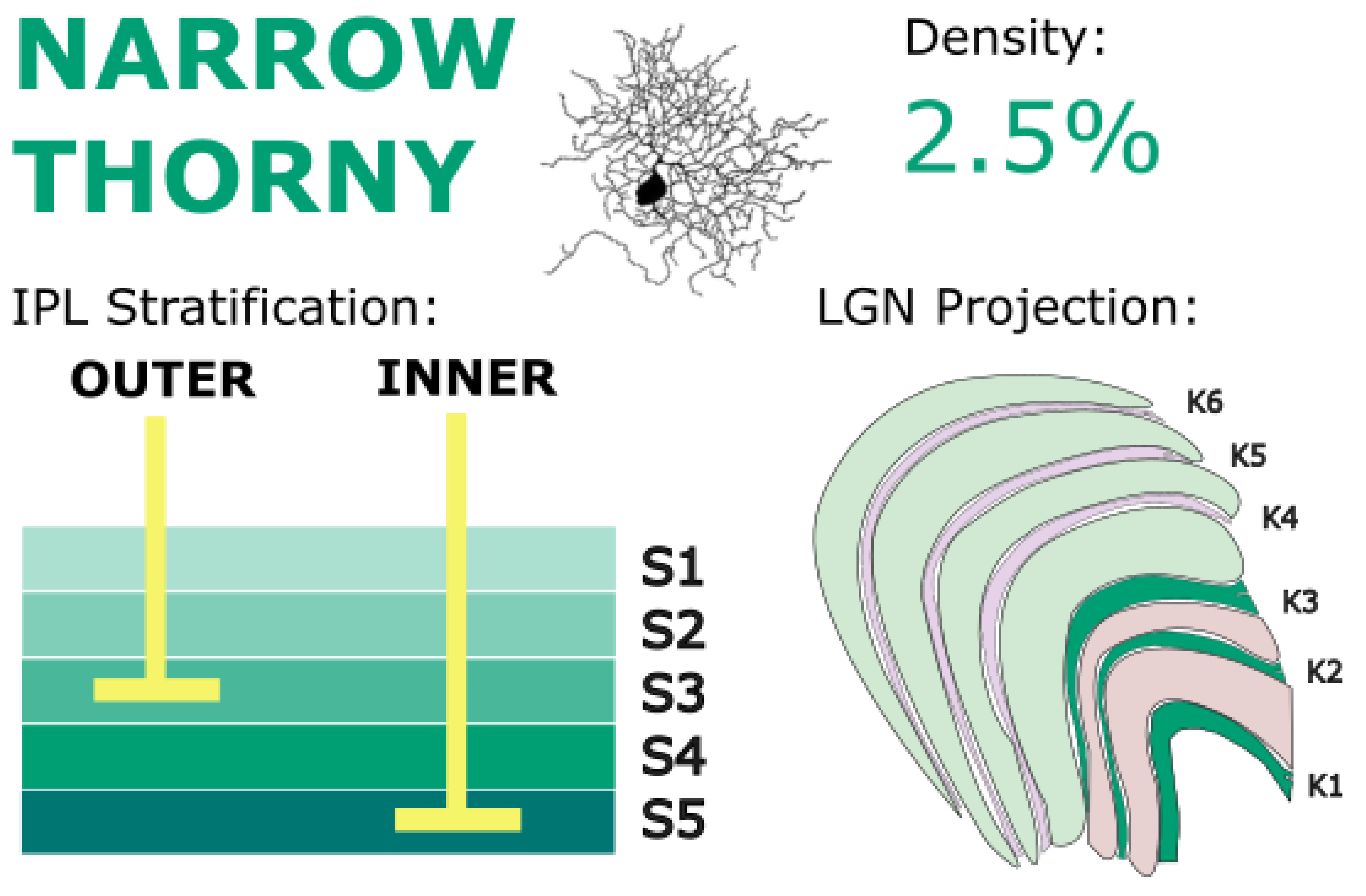

5.3. Narrow Thorny RGCs

5.4. Broad Thorny RGCs

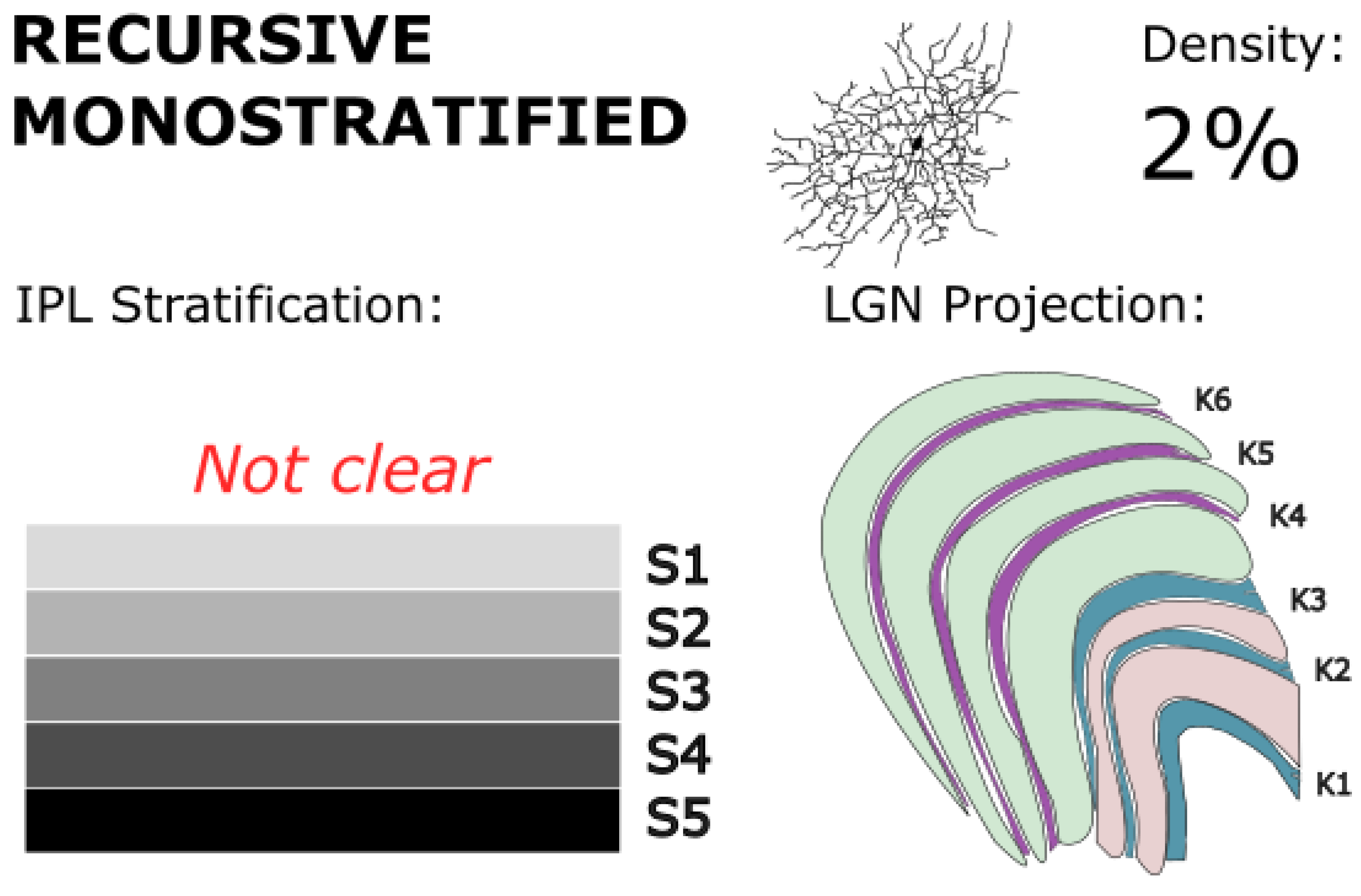

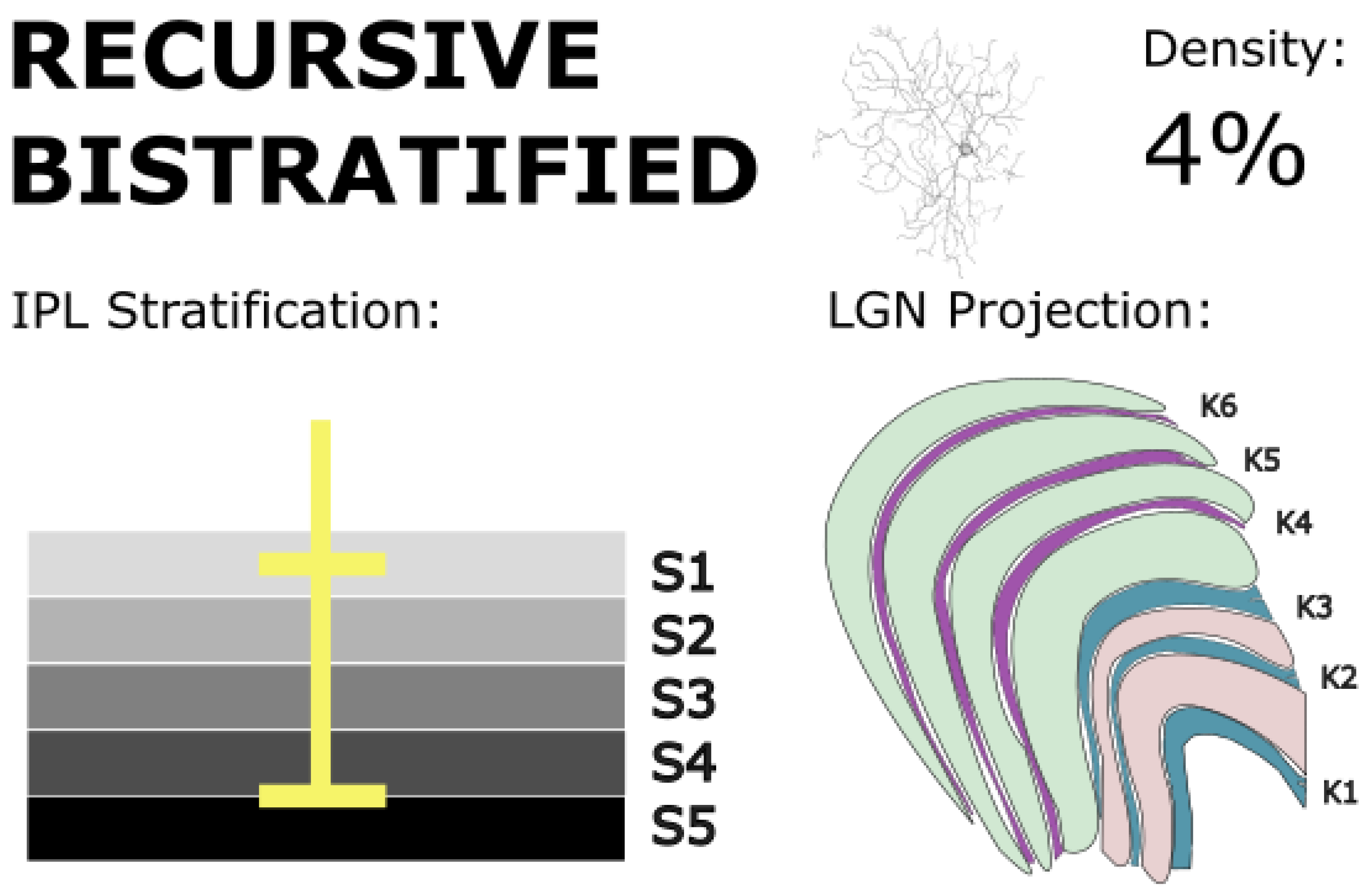

5.5. Recursive RGCs

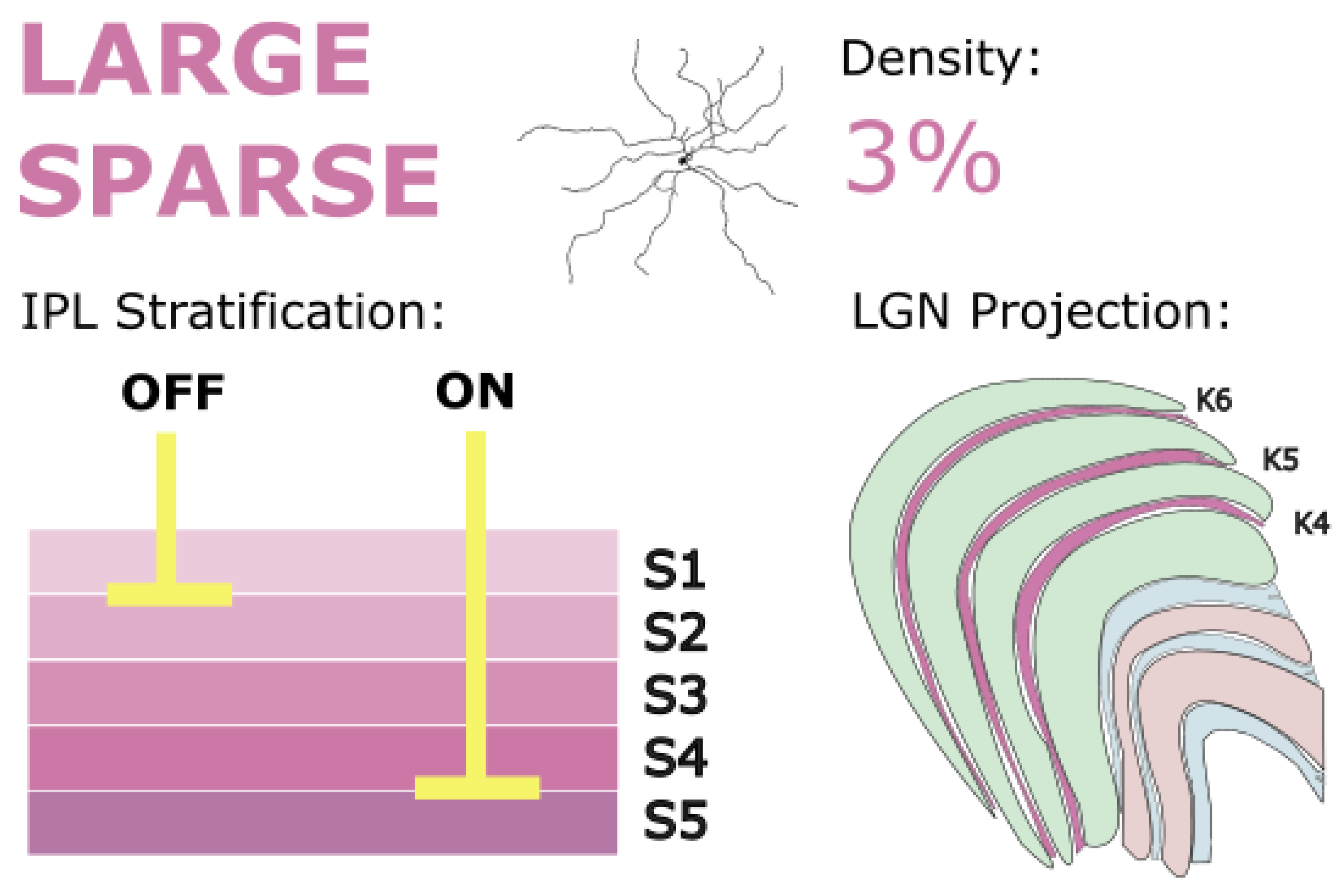

5.6. Sparse Monostratified RGCs (Large Sparse RGCs)

5.7. Giant, Melanopsin-Containing, Intrinsically Photosensitive RGCs

6. Summary and Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adhikari, P.; Uprety, S.; Feigl, B.; Zele, A.J. Melanopsin-mediated amplification of cone signals in the human visual cortex. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2024, 291, 20232708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadlou, M.; Zweifel, L.S.; Heimel, J.A. Functional modulation of primary visual cortex by the superior colliculus in the mouse. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajina, S.; Bridge, H. Blindsight relies on a functional connection between hMT+ and the lateral geniculate nucleus, not the pulvinar. PLOS Biol. 2018, 16, e2005769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Hashmi, A.M.; Kramer, D.J.; Mullen, K.T. Human vision with a lesion of the parvocellular pathway: an optic neuritis model for selective contrast sensitivity deficits with severe loss of midget ganglion cell function. Exp. Brain Res. 2011, 215, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appleby, T.R.; Manookin, M.B. Selectivity to approaching motion in retinal inputs to the dorsal visual pathway. eLife 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleby, T. R. , Rieke, F., & Manookin, M. B. (). Separate pathways for processing local and global motion in the primate retina. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 2021, 62, 3039–3039. [Google Scholar]

- Atapour, N.; Worthy, K.H.; Rosa, M.G.P. Remodeling of lateral geniculate nucleus projections to extrastriate area MT following long-term lesions of striate cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2022, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baden, T.; Berens, P.; Franke, K.; Rosón, M.R.; Bethge, M.; Euler, T. The functional diversity of retinal ganglion cells in the mouse. Nature 2016, 529, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E Bakken, T.; van Velthoven, C.T.; Menon, V.; Hodge, R.D.; Yao, Z.; Nguyen, T.N.; Graybuck, L.T.; Horwitz, G.D.; Bertagnolli, D.; Goldy, J.; et al. Single-cell and single-nucleus RNA-seq uncovers shared and distinct axes of variation in dorsal LGN neurons in mice, non-human primates, and humans. eLife 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldicano, A.K.; Nasir-Ahmad, S.; Novelli, M.; Lee, S.C.; Do, M.T.H.; Martin, P.R.; Grünert, U. Retinal ganglion cells expressing CaM kinase II in human and nonhuman primates. J. Comp. Neurol. 2022, 530, 1470–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, M.K.; Balaram, P.; Kaas, J.H. The evolution and functions of nuclei of the visual pulvinar in primates. J. Comp. Neurol. 2017, 525, 3207–3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrionuevo, P.A.; Cao, D. Contributions of rhodopsin, cone opsins, and melanopsin to postreceptoral pathways inferred from natural image statistics. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 2014, 31, A131–A139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrionuevo, P.A.; Cao, D. Luminance and chromatic signals interact differently with melanopsin activation to control the pupil light response. J. Vis. 2016, 16, 29–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrionuevo, P.A.; Salinas, M.L.S.; Fanchini, J.M. Are ipRGCs involved in human color vision? Hints from physiology, psychophysics, and natural image statistics. Vis. Res. 2024, 217, 108378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benevento, L.; Miller, J. Visual responses of single neurons in the caudal lateral pulvinar of the macaque monkey. J. Neurosci. 1981, 1, 1268–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berson, D.M.; Castrucci, A.M.; Provencio, I. Morphology and mosaics of melanopsin-expressing retinal ganglion cell types in mice. J. Comp. Neurol. 2010, 518, 2405–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackshaw, S.; Sanes, J.R. Turning lead into gold: reprogramming retinal cells to cure blindness. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bordt, A.S.; Hoshi, H.; Yamada, E.S.; Perryman-Stout, W.C.; Marshak, D.W. Synaptic input to OFF parasol ganglion cells in macaque retina. J. Comp. Neurol. 2006, 498, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordt, A.S.; Patterson, S.S.; Girresch, R.J.; Perez, D.; Tseng, L.; Anderson, J.R.; Mazzaferri, M.A.; Kuchenbecker, J.A.; Gonzales-Rojas, R.; Roland, A.; et al. Synaptic inputs to broad thorny ganglion cells in macaque retina. J. Comp. Neurol. 2021, 529, 3098–3111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordt, A.S.; Patterson, S.S.; Girresch, R.J.; Perez, D.; Tseng, L.; Anderson, J.R.; Mazzaferri, M.A.; Kuchenbecker, J.A.; Gonzales-Rojas, R.; Roland, A.; et al. Synaptic inputs to broad thorny ganglion cells in macaque retina. J. Comp. Neurol. 2021, 529, 3098–3111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boycott, B.B.; Wässle, H. Morphological Classification of Bipolar Cells of the Primate Retina. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1991, 3, 1069–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boycott, B.; Wässle, H. Parallel processing in the mammalian retina: the Proctor Lecture. . 1999, 40, 1313–27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Braak, H.; Bachmann, A. The percentage of projection neurons and interneurons in the human lateral geniculate-nucleus. Human Neurobiology 1985, 4, 91–95. [Google Scholar]

- Bridge, H.; Leopold, D.A.; Bourne, J.A. Adaptive Pulvinar Circuitry Supports Visual Cognition. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2016, 20, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, F.; Usrey, W.M. Corticogeniculate feedback and visual processing in the primate. J. Physiol. 2010, 589, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.M.; Gias, C.; Hatori, M.; Keding, S.R.; Semo, M.; Coffey, P.J.; Gigg, J.; Piggins, H.D.; Panda, S.; Lucas, R.J. Melanopsin Contributions to Irradiance Coding in the Thalamo-Cortical Visual System. PLOS Biol. 2010, 8, e1000558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, T.M.; Tsujimura, S.-I.; Allen, A.E.; Wynne, J.; Bedford, R.; Vickery, G.; Vugler, A.; Lucas, R.J. Melanopsin-Based Brightness Discrimination in Mice and Humans. Curr. Biol. 2012, 22, 1134–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calkins, D.J.; Sterling, P. Absence of spectrally specific lateral inputs to midget ganglion cells in primate retina. Nature 1996, 381, 613–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calkins, D.J.; Sterling, P. Microcircuitry for Two Types of Achromatic Ganglion Cell in Primate Fovea. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 2646–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calkins, D.J.; Tsukamoto, Y.; Sterling, P. Microcircuitry and Mosaic of a Blue–Yellow Ganglion Cell in the Primate Retina. J. Neurosci. 1998, 18, 3373–3385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaway, E.M. Structure and function of parallel pathways in the primate early visual system. J. Physiol. 2005, 566, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casagrande, V.; Yazar, F.; Jones, K.; Ding, Y. The Morphology of the Koniocellular Axon Pathway in the Macaque Monkey. Cereb. Cortex 2007, 17, 2334–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casanova, C.; Chalupa, L.M. The dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus and the pulvinar as essential partners for visual cortical functions. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1258393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC. (2022, December 19). Fast Facts of Common Eye Disorders | CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/visionhealth/basics/ced/fastfacts.

- Chandra, A.J.; Lee, S.C.S.; Grünert, U. Thorny ganglion cells in marmoset retina: Morphological and neurochemical characterization with antibodies against calretinin. J. Comp. Neurol. 2017, 525, 3962–3974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Callaway, E.M. S Cone Contributions to the Magnocellular Visual Pathway in Macaque Monkey. Neuron 2002, 35, 1135–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Callaway, E.M. Parallel colour-opponent pathways to primary visual cortex. Nature 2003, 426, 668–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-Y.; Hoffmann, K.-P.; Distler, C.; Hafed, Z.M. The Foveal Visual Representation of the Primate Superior Colliculus. Curr. Biol. 2019, 29, 2109–2119.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, S.K.; Tailby, C.; Solomon, S.G.; Martin, P.R. Cortical-Like Receptive Fields in the Lateral Geniculate Nucleus of Marmoset Monkeys. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 6864–6876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chichilnisky, E.J.; Kalmar, R.S. Temporal Resolution of Ensemble Visual Motion Signals in Primate Retina. J. Neurosci. 2003, 23, 6681–6689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowey, A. Visual System: How Does Blindsight Arise? Curr. Biol. 2010, 20, R702–R704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crook, J.D.; Packer, O.S.; Dacey, D.M. A synaptic signature for ON- and OFF-center parasol ganglion cells of the primate retina. Vis. Neurosci. 2013, 31, 57–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crook, J.D.; Peterson, B.B.; Packer, O.S.; Robinson, F.R.; Troy, J.B.; Dacey, D.M. Y-Cell Receptive Field and Collicular Projection of Parasol Ganglion Cells in Macaque Monkey Retina. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 11277–11291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacey, D.M. Morphology of a small-field bistratified ganglion cell type in the macaque and human retina. Vis. Neurosci. 1993, 10, 1081–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacey, D. The mosaic of midget ganglion cells in the human retina. J. Neurosci. 1993, 13, 5334–5355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dacey, D. M. (2004). Origins of Perception: Retinal Ganglion Cell Diversity and the Creation of Parallel Visual Pathways. In M. S. Gazzaniga (Ed.), The Cognitive Neurosciences Iii (p. 281). MIT Press.

- Dacey, D.M.; Brace, S. A coupled network for parasol but not midget ganglion cells in the primate retina. Vis. Neurosci. 1992, 9, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacey, D. M. , Kim, Y. J., Packer, O. S., & Detwiler, P. B. ON-OFF direction selective ganglion cells in macaque monkey retina are tracer-coupled to an ON-OFF direction selective amacrine cell type. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 2019, 60, 5280–5280. [Google Scholar]

- Dacey, D.M.; Liao, H.-W.; Peterson, B.B.; Robinson, F.R.; Smith, V.C.; Pokorny, J.; Yau, K.-W.; Gamlin, P.D. Melanopsin-expressing ganglion cells in primate retina signal colour and irradiance and project to the LGN. Nature 2005, 433, 749–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dacey, D.M.; Packer, O.S. Colour coding in the primate retina: diverse cell types and cone-specific circuitry. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2003, 13, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacey, D.; Packer, O.S.; Diller, L.; Brainard, D.; Peterson, B.; Lee, B. Center surround receptive field structure of cone bipolar cells in primate retina. Vis. Res. 2000, 40, 1801–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacey, D.M.; Petersen, M.R. Dendritic field size and morphology of midget and parasol ganglion cells of the human retina. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1992, 89, 9666–9670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacey, D.M.; Peterson, B.B.; Robinson, F.R.; Gamlin, P.D. Fireworks in the Primate Retina. Neuron 2003, 37, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, C.M.; Detwiler, P.B.; Dacey, D.M. Functional polarity of dendrites and axons of primate A1 amacrine cells. Vis. Neurosci. 2007, 24, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detwiler, P. B. , Crook, J., Packer, O., Robinson, F., & Dacey, D. M. The recursive bistratified ganglion cell type of the macaque monkey retina is ON-OFF direction selective. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 2019, 60, 3884–3884. [Google Scholar]

- Dhande, O.S.; Stafford, B.K.; Franke, K.; El-Danaf, R.; Percival, K.A.; Phan, A.H.; Li, P.; Hansen, B.J.; Nguyen, P.L.; Berens, P.; et al. Molecular Fingerprinting of On–Off Direction-Selective Retinal Ganglion Cells Across Species and Relevance to Primate Visual Circuits. J. Neurosci. 2018, 39, 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drouyer, E.; Rieux, C.; Hut, R.A.; Cooper, H.M. Responses of Suprachiasmatic Nucleus Neurons to Light and Dark Adaptation: Relative Contributions of Melanopsin and Rod–Cone Inputs. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 9623–9631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecker, J.L.; Dumitrescu, O.N.; Wong, K.Y.; Alam, N.M.; Chen, S.-K.; LeGates, T.; Renna, J.M.; Prusky, G.T.; Berson, D.M.; Hattar, S. Melanopsin-Expressing Retinal Ganglion-Cell Photoreceptors: Cellular Diversity and Role in Pattern Vision. Neuron 2010, 67, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiber, C.; Pietersen, A.; Zeater, N.; Solomon, S.; Martin, P. Chromatic summation and receptive field properties of blue-on and blue-off cells in marmoset lateral geniculate nucleus. Vis. Res. 2018, 151, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiber, C.D.; Rahman, A.S.; Pietersen, A.N.; Zeater, N.; Dreher, B.; Solomon, S.G.; Martin, P.R. Receptive Field Properties of Koniocellular On/Off Neurons in the Lateral Geniculate Nucleus of Marmoset Monkeys. J. Neurosci. 2018, 38, 10384–10398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enroth-Cugell, C.; Robson, J.G. The contrast sensitivity of retinal ganglion cells of the cat. J. Physiol. 1966, 187, 517–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Famiglietti, E.V.; Kaneko, A.; Tachibana, M. Neuronal Architecture of On and Off Pathways to Ganglion Cells in Carp Retina. Science 1977, 198, 1267–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, G.; Chichilnisky, E. Information Processing in the Primate Retina: Circuitry and Coding. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2007, 30, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, S.D.; Murphy, G.J. Distinct cell types in the superficial superior colliculus project to the dorsal lateral geniculate and lateral posterior thalamic nuclei. J. Neurophysiol. 2018, 120, 1286–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghodrati, M.; Khaligh-Razavi, S.-M.; Lehky, S.R. Towards building a more complex view of the lateral geniculate nucleus: Recent advances in understanding its role. Prog. Neurobiol. 2017, 156, 214–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooley, J.J.; Lu, J.; Chou, T.C.; Scammell, T.E.; Saper, C.B. Melanopsin in cells of origin of the retinohypothalamic tract. Nat. Neurosci. 2001, 4, 1165–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouras, P. Identification of cone mechanisms in monkey ganglion cells. J. Physiol. 1968, 199, 533–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieve, K.L.; Acuña, C.; Cudeiro, J. The primate pulvinar nuclei: vision and action. Trends Neurosci. 2000, 23, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grünert, U.; Jusuf, P.R.; Lee, S.C.; Nguyen, D.T. Bipolar input to melanopsin containing ganglion cells in primate retina. Vis. Neurosci. 2010, 28, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grünert, U.; Lee, S.C.S.; Kwan, W.C.; Mundinano, I.-C.; Bourne, J.A.; Martin, P.R. Retinal ganglion cells projecting to superior colliculus and pulvinar in marmoset. Anat. Embryol. 2021, 226, 2745–2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grünert, U.; Martin, P.R. Cell types and cell circuits in human and non-human primate retina. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2020, 78, 100844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grünert, U.; Martin, P.R. Morphology, Molecular Characterization, and Connections of Ganglion Cells in Primate Retina. Annu. Rev. Vis. Sci. 2021, 7, 73–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillery, R.; Sherman, S. Thalamic Relay Functions and Their Role in Corticocortical Communication. Neuron 2002, 33, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güler, A.D.; Ecker, J.L.; Lall, G.S.; Haq, S.; Altimus, C.M.; Liao, H.-W.; Barnard, A.R.; Cahill, H.; Badea, T.C.; Zhao, H.; et al. Melanopsin cells are the principal conduits for rod–cone input to non-image-forming vision. Nature 2008, 453, 102–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, J.; Monavarfeshani, A.; Qiao, M.; Kao, A.H.; Kölsch, Y.; Kumar, A.; Kunze, V.P.; Rasys, A.M.; Richardson, R.; Wekselblatt, J.B.; et al. Evolution of neuronal cell classes and types in the vertebrate retina. Nature 2023, 624, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halnes, G.; Augustinaite, S.; Heggelund, P.; Einevoll, G.T.; Migliore, M. A Multi-Compartment Model for Interneurons in the Dorsal Lateral Geniculate Nucleus. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2011, 7, e1002160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankins, M.W.; Peirson, S.N.; Foster, R.G. Melanopsin: an exciting photopigment. Trends Neurosci. 2008, 31, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannibal, J.; Christiansen, A.T.; Heegaard, S.; Fahrenkrug, J.; Kiilgaard, J.F. Melanopsin expressing human retinal ganglion cells: Subtypes, distribution, and intraretinal connectivity. J. Comp. Neurol. 2017, 525, 1934–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haverkamp, S. (2010). Morphology of Interneurons: Bipolar Cells. In Encyclopedia of the Eye (pp. 65–73). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Haverkamp, S.; Haeseleer, F.; Hendrickson, A. A comparison of immunocytochemical markers to identify bipolar cell types in human and monkey retina. Vis. Neurosci. 2003, 20, 589–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendry, S.H.C.; Reid, R.C. The Koniocellular Pathway in Primate Vision. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2000, 23, 127–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendry, S.H.C.; Yoshioka, T. A Neurochemically Distinct Third Channel in the Macaque Dorsal Lateral Geniculate Nucleus. Science 1994, 264, 575–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey, T.L.; Guillery, R.W. Variability of laminar patterns in the human lateral geniculate nucleus. J. Comp. Neurol. 1979, 183, 221–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwitz, G. What studies of macaque monkeys have told us about human color vision. Neuroscience 2015, 296, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Jonas, P. A supercritical density of Na+ channels ensures fast signaling in GABAergic interneuron axons. Nat. Neurosci. 2014, 17, 686–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huberman, A.D.; Wei, W.; Elstrott, J.; Stafford, B.K.; Feller, M.B.; Barres, B.A. Genetic Identification of an On-Off Direction- Selective Retinal Ganglion Cell Subtype Reveals a Layer-Specific Subcortical Map of Posterior Motion. Neuron 2009, 62, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isa, T.; Yoshida, M. Neural Mechanism of Blindsight in a Macaque Model. Neuroscience 2021, 469, 138–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, S.; Feldheim, D.A. The Mouse Superior Colliculus: An Emerging Model for Studying Circuit Formation and Function. Front. Neural Circuits 2018, 12, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, G.H. THE DISTRIBUTION AND NATURE OF COLOUR VISION AMONG THE MAMMALS. Biol. Rev. 1993, 68, 413–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, R.A.; Marshak, D.W. Synaptic connections of DB3 diffuse bipolar cell axons in macaque retina. J. Comp. Neurol. 2000, 416, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, R.A.; Wiechmann, A.F.; Amara, S.G.; Leighton, B.H.; Marshak, D.W. Diffuse bipolar cells provide input to OFF parasol ganglion cells in the macaque retina. J. Comp. Neurol. 2000, 416, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayakumar, J.; Dreher, B.; Vidyasagar, T.R. Tracking blue cone signals in the primate brain. Clin. Exp. Optom. 2013, 96, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jusuf, P.R.; Lee, S.C.; Grünert, U. Synaptic connectivity of the diffuse bipolar cell type DB6 in the inner plexiform layer of primate retina. J. Comp. Neurol. 2004, 469, 494–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jusuf, P.R.; Lee, S.C.S.; Hannibal, J.; Grünert, U. Characterization and synaptic connectivity of melanopsin-containing ganglion cells in the primate retina. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2007, 26, 2906–2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaas, J.H.; Huerta, M.F.; Weber, J.T.; Harting, J.K. Patterns of retinal terminations and laminar organization of the lateral geniculate nucleus of primates. J. Comp. Neurol. 1978, 182, 517–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaas, J.H.; Lyon, D.C. Pulvinar contributions to the dorsal and ventral streams of visual processing in primates. Brain Res. Rev. 2007, 55, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, E. (2003). The M, P, and K Pathways of the Primate Visual System. In L. M. Chalupa & J. S. Werner (Eds.), The Visual Neurosciences, 2-vol. Set (pp. 481–493). The MIT Press. [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, E.; Shapley, R.M. X and Y cells in the lateral geniculate nucleus of macaque monkeys. J. Physiol. 1982, 330, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastner, S. , Schneider, K. A., & Wunderlich, K. (2006). Beyond a relay nucleus: Neuroimaging views on the human LGN. In Progress in Brain Research (Vol. 155, pp. 125–143). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Peterson, B.B.; Crook, J.D.; Joo, H.R.; Wu, J.; Puller, C.; Robinson, F.R.; Gamlin, P.D.; Yau, K.-W.; Viana, F.; et al. Origins of direction selectivity in the primate retina. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Peterson, B.B.; Crook, J.D.; Joo, H.R.; Wu, J.; Puller, C.; Robinson, F.R.; Gamlin, P.D.; Yau, K.-W.; Viana, F.; et al. Origins of direction selectivity in the primate retina. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, C.; Evrard, H.C.; Shapcott, K.A.; Haverkamp, S.; Logothetis, N.K.; Schmid, M.C. Cell-Targeted Optogenetics and Electrical Microstimulation Reveal the Primate Koniocellular Projection to Supra-granular Visual Cortex. Neuron 2016, 90, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, H. (1995). Roles of Amacrine Cells. In H. Kolb, E. Fernandez, & R. Nelson (Eds.), Webvision: The Organization of the Retina and Visual System. University of Utah Health Sciences Center. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK11539/.

- Kolb, H.; Linberg, K.A.; Fisher, S.K. Neurons of the human retina: A Golgi study. J. Comp. Neurol. 1992, 318, 147–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuffler, S.W. Discharge patterns and functional organization of mammalian retina. J. Neurophysiol. 1953, 16, 37–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.B. Receptive field structure in the primate retina. Vis. Res. 1996, 36, 631–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.B. Receptive field structure in the primate retina. Vis. Res. 1996, 36, 631–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.C.; Jusuf, P.R.; Grünert, U. S-cone connections of the diffuse bipolar cell type DB6 in macaque monkey retina. J. Comp. Neurol. 2004, 474, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.C.S.; Wei, A.J.; Martin, P.R.; Grünert, U. Thorny and Tufted Retinal Ganglion Cells Express the Transcription Factor Forkhead Proteins Foxp1 and Foxp2 in Marmoset (Callithrix jacchus). J. Comp. Neurol. 2024, 532, e25663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennie, P.; Dzmura, M. Mechanisms of color-vision. Critical Reviews in Neurobiology 1988, 3, 333–400. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, W. , & Chen, S. The Origin of the S-Off Signal in a Mammalian Retina. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 2011, 52, 3027–3027. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, H.; Ren, X.; Peterson, B.B.; Marshak, D.W.; Yau, K.; Gamlin, P.D.; Dacey, D.M. Melanopsin-expressing ganglion cells on macaque and human retinas form two morphologically distinct populations. J. Comp. Neurol. 2016, 524, 2845–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, A.; Milner, E.S.; Peng, Y.-R.; Blume, H.A.; Brown, M.C.; Bryman, G.S.; Emanuel, A.J.; Morquette, P.; Viet, N.-M.; Sanes, J.R.; et al. Encoding of environmental illumination by primate melanopsin neurons. Science 2023, 379, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, P.E.; Huff, T.J.; Zuniga, J.M. The potential role of bioengineering and three-dimensional printing in curing global corneal blindness. J. Tissue Eng. 2018, 9, 2041731418769863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, I.C.; Nasir-Ahmad, S.; Lee, S.C.; Grünert, U.; Martin, P.R. Contribution of parasol-magnocellular pathway ganglion cells to foveal retina in macaque monkey. Vis. Res. 2022, 202, 108154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malpeli, J. G. , Lee, D., & Baker, F. H. Laminar and retinotopic organization of the macaque lateral geniculate nucleus: Magnocellular and parvocellular magnification functions. The Journal of Comparative Neurology 1996, 375, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manookin, M.B.; Patterson, S.S.; Linehan, C.M. Neural Mechanisms Mediating Motion Sensitivity in Parasol Ganglion Cells of the Primate Retina. Neuron 2018, 97, 1327–1340.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, A.P. Amacrine cells of the rhesus monkey retina. J. Comp. Neurol. 1990, 301, 382–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshak, D.W.; Mills, S.L. Short-wavelength cone-opponent retinal ganglion cells in mammals. Vis. Neurosci. 2014, 31, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, P.R.; Blessing, E.M.; Buzás, P.; Szmajda, B.A.; Forte, J.D. Transmission of colour and acuity signals by parvocellular cells in marmoset monkeys. J. Physiol. 2011, 589, 2795–2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, P.R.; White, A.J.R.; Goodchild, A.K.; Wilder, H.D.; Sefton, A.E. Evidence that Blue-on Cells are Part of the Third Geniculocortical Pathway in Primates. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1997, 9, 1536–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masri, R.A.; Lee, S.C.S.; Madigan, M.C.; Grünert, U. Particle-Mediated Gene Transfection and Organotypic Culture of Postmortem Human Retina. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2019, 8, 7–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masri, R.A.; Percival, K.A.; Koizumi, A.; Martin, P.R.; Grünert, U. Connectivity between the OFF bipolar type DB3a and six types of ganglion cell in the marmoset retina. J. Comp. Neurol. 2015, 524, 1839–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masri, R.A.; Percival, K.A.; Koizumi, A.; Martin, P.R.; Grünert, U. Survey of retinal ganglion cell morphology in marmoset. J. Comp. Neurol. 2017, 527, 236–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meredith, M.A.; Stein, B.E. Visual, auditory, and somatosensory convergence on cells in superior colliculus results in multisensory integration. J. Neurophysiol. 1986, 56, 640–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merigan, W.; Katz, L.; Maunsell, J. The effects of parvocellular lateral geniculate lesions on the acuity and contrast sensitivity of macaque monkeys. J. Neurosci. 1991, 11, 994–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, C.R. Retinal afferent arborization patterns, dendritic field orientations, and the segregation of function in the lateral geniculate nucleus of the monkey. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1988, 85, 4914–4918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, S.L.; Tian, L.-M.; Hoshi, H.; Whitaker, C.M.; Massey, S.C. Three Distinct Blue-Green Color Pathways in a Mammalian Retina. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 1760–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirochnik, R.M.; Pezaris, J.S. Contemporary approaches to visual prostheses. Mil. Med Res. 2019, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moritoh, S.; Komatsu, Y.; Yamamori, T.; Koizumi, A. Diversity of Retinal Ganglion Cells Identified by Transient GFP Transfection in Organotypic Tissue Culture of Adult Marmoset Monkey Retina. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e54667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullen, K.T.; Kingdom, F.A. Differential distributions of red–green and blue–yellow cone opponency across the visual field. Vis. Neurosci. 2002, 19, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, K.D.; Rubin, C.M.; Jones, E.G.; Chalupa, L.M. Molecular Correlates of Laminar Differences in the Macaque Dorsal Lateral Geniculate Nucleus. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 12010–12022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir-Ahmad, S.; Lee, S.C.; Martin, P.R.; Grünert, U. Melanopsin-expressing ganglion cells in human retina: Morphology, distribution, and synaptic connections. J. Comp. Neurol. 2017, 527, 312–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir-Ahmad, S.; Lee, S.C.S.; Martin, P.R.; Grünert, U. Identification of retinal ganglion cell types expressing the transcription factor Satb2 in three primate species. J. Comp. Neurol. 2021, 529, 2727–2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir-Ahmad, S.; Vanstone, K.A.; Novelli, M.; Lee, S.C.S.; Do, M.T.H.; Martin, P.R.; Grünert, U. Satb1 expression in retinal ganglion cells of marmosets, macaques, and humans. J. Comp. Neurol. 2021, 530, 923–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neitz, J.; Neitz, M. Evolution of the circuitry for conscious color vision in primates. Eye 2016, 31, 286–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, R.; Famiglietti, E.V.; Kolb, H. Intracellular staining reveals different levels of stratification for on- and off-center ganglion cells in cat retina. J. Neurophysiol. 1978, 41, 472–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, S.S.; Girresch, R.J.; Mazzaferri, M.A.; Bordt, A.S.; Piñon-Teal, W.L.; Jesse, B.D.; Perera, D.-C.W.; Schlepphorst, M.A.; Kuchenbecker, J.A.; Chuang, A.Z.; et al. Synaptic Origins of the Complex Receptive Field Structure in Primate Smooth Monostratified Retinal Ganglion Cells. eneuro 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, S.S.; Mazzaferri, M.A.; Bordt, A.S.; Chang, J.; Neitz, M.; Neitz, J. Another Blue-ON ganglion cell in the primate retina. Curr. Biol. 2020, 30, R1409–R1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, S.S.; Neitz, M.; Neitz, J. Reconciling Color Vision Models With Midget Ganglion Cell Receptive Fields. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, S.S.; Neitz, M.; Neitz, J. S-cone circuits in the primate retina for non-image-forming vision. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 126, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.-R.; Shekhar, K.; Yan, W.; Herrmann, D.; Sappington, A.; Bryman, G.S.; van Zyl, T.; Do, M.T.H.; Regev, A.; Sanes, J.R. Molecular Classification and Comparative Taxonomics of Foveal and Peripheral Cells in Primate Retina. Cell 2019, 176, 1222–1237.e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percival, K.A.; Koizumi, A.; Masri, R.A.; Buzás, P.; Martin, P.R.; Grünert, U. Identification of a Pathway from the Retina to Koniocellular Layer K1 in the Lateral Geniculate Nucleus of Marmoset. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 3821–3825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percival, K.A.; Martin, P.R.; Grünert, U. Synaptic inputs to two types of koniocellular pathway ganglion cells in marmoset retina. J. Comp. Neurol. 2010, 519, 2135–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percival, K.A.; Martin, P.R.; Grünert, U. Organisation of koniocellular-projecting ganglion cells and diffuse bipolar cells in the primate fovea. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2013, 37, 1072–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Percival, K.A.; Venkataramani, S.; Smith, R.G.; Taylor, W.R. Directional excitatory input to direction-selective ganglion cells in the rabbit retina. J. Comp. Neurol. 2017, 527, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, V.; Oehler, R.; Cowey, A. Retinal ganglion cells that project to the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus in the macaque monkey. Neuroscience 1984, 12, 1101–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, B. B. , Liao, H., Dacey, D. M., Yau, K., Gamlin, P. D., Robinson, F. R., & Marshak, D. W. Functional architecture of the photoreceptive ganglion cell in primate retina: Morphology, mosaic organization and central targets of melanopsin immunostained cells. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 2003, 44, 5182–5182. [Google Scholar]

- Pietersen, A.N.J.; Cheong, S.K.; Solomon, S.G.; Tailby, C.; Martin, P.R. Temporal response properties of koniocellular (blue-on and blue-off) cells in marmoset lateral geniculate nucleus. J. Neurophysiol. 2014, 112, 1421–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pregowska, A.; Casti, A.; Kaplan, E.; Wajnryb, E.; Szczepanski, J. Information processing in the LGN: a comparison of neural codes and cell types. Biol. Cybern. 2019, 113, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puller, C.; Manookin, M.B.; Neitz, J.; Rieke, F.; Neitz, M. Broad Thorny Ganglion Cells: A Candidate for Visual Pursuit Error Signaling in the Primate Retina. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 5397–5408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puller, C. , Manookin, M., Neitz, M., Rieke, F., & Neitz, J. (). Response properties of broad thorny ganglion cells in the primate retina. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 2013, 54, 1295–1295. [Google Scholar]

- Puthussery, T.; Percival, K.A.; Venkataramani, S.; Gayet-Primo, J.; Grünert, U.; Taylor, W.R. Kainate Receptors Mediate Synaptic Input to Transient and Sustained OFF Visual Pathways in Primate Retina. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 7611–7621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramón y Cajal, S. (1972). The structure of the retina. C. C. Thomas.

- Rhoades, C.E.; Shah, N.P.; Manookin, M.B.; Brackbill, N.; Kling, A.; Goetz, G.; Sher, A.; Litke, A.M.; Chichilnisky, E. Unusual Physiological Properties of Smooth Monostratified Ganglion Cell Types in Primate Retina. Neuron 2019, 103, 658–672.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, D.L.; Petersen, S.E. The pulvinar and visual salience. Trends Neurosci. 1992, 15, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodieck, R. W. (1991). Which Cells Code for Color? In A. Valberg & B. B. Lee (Eds.), From Pigments to Perception: Advances in Understanding Visual Processes (pp. 83–93). Springer US. [CrossRef]

- Rodieck, R.W.; Watanabe, M. Survey of the morphology of macaque retinal ganglion cells that project to the pretectum, superior colliculus, and parvicellular laminae of the lateral geniculate nucleus. J. Comp. Neurol. 1993, 338, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, A.; Talebi, V. The Primate Retina Contains Distinct Types of Y-Like Ganglion Cells: Figure 1. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 5048–5050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roska, B.; Werblin, F. Rapid global shifts in natural scenes block spiking in specific ganglion cell types. Nat. Neurosci. 2003, 6, 600–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Jayakumar, J.; Martin, P.R.; Dreher, B.; Saalmann, Y.B.; Hu, D.; Vidyasagar, T.R. Segregation of short-wavelength-sensitive (S) cone signals in the macaque dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2009, 30, 1517–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanes, J.R.; Masland, R.H. The Types of Retinal Ganglion Cells: Current Status and Implications for Neuronal Classification. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2015, 38, 221–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiller, P.H. Parallel information processing channels created in the retina. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2010, 107, 17087–17094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiller, P.H.; Logothetis, N.K. The color-opponent and broad-band channels of the primate visual system. Trends Neurosci. 1990, 13, 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiller, P.H.; Logothetis, N.K.; Charles, E.R. Functions of the colour-opponent and broad-band channels of the visual system. Nature 1990, 343, 68–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiller, P.H.; Tehovnik, E.J. Vision and the Visual System; Oxford University Press (OUP): Oxford, Oxfordshire, United Kingdom, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, M.C.; Mrowka, S.W.; Turchi, J.; Saunders, R.C.; Wilke, M.; Peters, A.J.; Ye, F.Q.; Leopold, D.A. Blindsight depends on the lateral geniculate nucleus. Nature 2010, 466, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, T.M.; Do, M.T.H.; Dacey, D.; Lucas, R.; Hattar, S.; Matynia, A. Melanopsin-Positive Intrinsically Photosensitive Retinal Ganglion Cells: From Form to Function. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 16094–16101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, T.M.; Taniguchi, K.; Kofuji, P. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Light Responses in Melanopsin-Expressing Ganglion Cells During Mouse Development. J. Neurophysiol. 2008, 100, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sciaccotta, F.; Kipcak, A.; Erisir, A. Morphological and Molecular Distinctions of Parallel Processing Streams Reveal Two Koniocellular Pathways in the Tree Shrew DLGN. eneuro 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhar, K.; Sanes, J.R. Generating and Using Transcriptomically Based Retinal Cell Atlases. Annu. Rev. Vis. Sci. 2021, 7, 43–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.S.; Park, S.S.; Albini, T.A.; Canto-Soler, M.V.; Klassen, H.; MacLaren, R.E.; Takahashi, M.; Nagiel, A.; Schwartz, S.D.; Bharti, K. Retinal stem cell transplantation: Balancing safety and potential. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2020, 75, 100779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sollars, P.J.; Smeraski, C.A.; Kaufman, J.D.; Ogilvie, M.D.; Provencio, I.; Pickard, G.E. Melanopsin and non-melanopsin expressing retinal ganglion cells innervate the hypothalamic suprachiasmatic nucleus. Vis. Neurosci. 2003, 20, 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S. G. (2021). Retinal ganglion cells and the magnocellular, parvocellular, and koniocellular subcortical visual pathways from the eye to the brain. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology (Vol. 178, pp. 31–50). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S.G.; Rosa, M.G.P. A simpler primate brain: the visual system of the marmoset monkey. Front. Neural Circuits 2014, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S.G.; White, A.J.R.; Martin, P.R. Extraclassical Receptive Field Properties of Parvocellular, Magnocellular, and Koniocellular Cells in the Primate Lateral Geniculate Nucleus. J. Neurosci. 2002, 22, 338–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, F.; Hsiang, J.-C.; Rajagopal, R.; Piggott, K.; Harocopos, G.J.; Couch, S.M.; Custer, P.; Morgan, J.L.; Kerschensteiner, D. Efficient Coding by Midget and Parasol Ganglion Cells in the Human Retina. Neuron 2020, 107, 656–666.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stacy, A. K. , & Van Hooser, S. D. Development of Functional Properties in the Early Visual System: New Appreciations of the Roles of Lateral Geniculate Nucleus. Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences 2022, 53, 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Smithson, H.E.; Zaidi, Q.; Lee, B.B. Specificity of Cone Inputs to Macaque Retinal Ganglion Cells. J. Neurophysiol. 2006, 95, 837–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S. H. , Renshaw, K., & Pezaris, J. S. (2024). Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of macaque LGN neurons reveals novel subpopulations (p. 2024.11.14.623611). bioRxiv. [CrossRef]

- Szmajda, B.A.; Buzás, P.; FitzGibbon, T.; Martin, P.R. Geniculocortical relay of blue-off signals in the primate visual system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2006, 103, 19512–19517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szmajda, B.A.; Grünert, U.; Martin, P.R. Retinal ganglion cell inputs to the koniocellular pathway. J. Comp. Neurol. 2008, 510, 251–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tailby, C.; Solomon, S.G.; Dhruv, N.T.; Majaj, N.J.; Sokol, S.H.; Lennie, P. A New Code for Contrast in the Primate Visual Pathway. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 3904–3909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tailby, C.; Solomon, S.G.; Lennie, P. Functional Asymmetries in Visual Pathways Carrying S-Cone Signals in Macaque. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 4078–4087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Todo, Y.; Ji, J.; Tang, Z. A novel motion direction detection mechanism based on dendritic computation of direction-selective ganglion cells. Knowledge-Based Syst. 2022, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoreson, W.B.; Dacey, D.M. Diverse Cell Types, Circuits, and Mechanisms for Color Vision in the Vertebrate Retina. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 1527–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usrey, W.M.; Reppas, J.B.; Reid, R.C. Specificity and Strength of Retinogeniculate Connections. J. Neurophysiol. 1999, 82, 3527–3540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaney, D.I.; Sivyer, B.; Taylor, W.R. Direction selectivity in the retina: symmetry and asymmetry in structure and function. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2012, 13, 194–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walmsley, L.; Hanna, L.; Mouland, J.; Martial, F.; West, A.; Smedley, A.R.; A Bechtold, D.; Webb, A.R.; Lucas, R.J.; Brown, T.M. Colour As a Signal for Entraining the Mammalian Circadian Clock. PLOS Biol. 2015, 13, e1002127–e1002127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, N.; Ghosh, K.K.; FitzGibbon, T. Intraretinal axon diameters of a New World primate, the marmoset (Callithrix jacchus). Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2000, 28, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, C.E.; Kwan, W.C.; Wright, D.; Johnston, L.A.; Egan, G.F.; Bourne, J.A. Preservation of Vision by the Pulvinar following Early-Life Primary Visual Cortex Lesions. Curr. Biol. 2015, 25, 424–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wässle, H. Parallel processing in the mammalian retina. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004, 5, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wässle, H.; Boycott, B.B.; Röhrenbeck, J. Horizontal Cells in the Monkey Retina: Cone connections and dendritic network. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1989, 1, 421–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wässle, H.; Grünert, U.; Röhrenbeck, J.; Boycott, B.B. Cortical magnification factor and the ganglion cell density of the primate retina. Nature 1989, 341, 643–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, M.; Rodieck, R.W. Parasol and midget ganglion cells of the primate retina. J. Comp. Neurol. 1989, 289, 434–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, A.J.R.; Solomon, S.G.; Martin, P.R. Spatial properties of koniocellular cells in the lateral geniculate nucleus of the marmoset Callithrix jacchus. J. Physiol. 2001, 533, 519–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, B.J.; Kan, J.Y.; Levy, R.; Itti, L.; Munoz, D.P. Superior colliculus encodes visual saliency before the primary visual cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2017, 114, 9451–9456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. (2022, October 13). Vision impairment and blindness. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/blindness-and-visual-impairment.

- Wienbar, S.; Schwartz, G.W. The dynamic receptive fields of retinal ganglion cells. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2018, 67, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesel, T.N.; Hubel, D.H. Spatial and chromatic interactions in the lateral geniculate body of the rhesus monkey. J. Neurophysiol. 1966, 29, 1115–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Ichida, J.M.; Allison, J.D.; Boyd, J.D.; Bonds, A.B.; Casagrande, V.A. A comparison of koniocellular, magnocellular and parvocellular receptive field properties in the lateral geniculate nucleus of the owl monkey (Aotus trivirgatus). J. Physiol. 2001, 531, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Ichida, J.; Shostak, Y.; Bonds, A.; Casagrande, V.A. Are primate lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN) cells really sensitive to orientation or direction? Vis. Neurosci. 2002, 19, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Vasudeva, V.; Vardi, N.; Sterling, P.; Freed, M.A. Different types of ganglion cell share a synaptic pattern. J. Comp. Neurol. 2008, 507, 1871–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, E.S.; Bordt, A.S.; Marshak, D.W. Wide-field ganglion cells in macaque retinas. Vis. Neurosci. 2005, 22, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Peng, Y.-R.; van Zyl, T.; Regev, A.; Shekhar, K.; Juric, D.; Sanes, J.R. Cell Atlas of The Human Fovea and Peripheral Retina. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.-H.; Atapour, N.; Chaplin, T.A.; Worthy, K.H.; Rosa, M.G. Robust Visual Responses and Normal Retinotopy in Primate Lateral Geniculate Nucleus following Long-term Lesions of Striate Cortex. J. Neurosci. 2018, 38, 3955–3970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.-H.; Chaplin, T.A.; Egan, G.W.; Reser, D.H.; Worthy, K.H.; Rosa, M.G.P. Visually Evoked Responses in Extrastriate Area MT after Lesions of Striate Cortex in Early Life. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 12479–12489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, F.H.; Hull, J.T.; Peirson, S.N.; Wulff, K.; Aeschbach, D.; Gooley, J.J.; Brainard, G.C.; Gregory-Evans, K.; Rizzo, J.F.; Czeisler, C.A.; et al. Short-Wavelength Light Sensitivity of Circadian, Pupillary, and Visual Awareness in Humans Lacking an Outer Retina. Curr. Biol. 2007, 17, 2122–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeater, N.; Buzás, P.; Dreher, B.; Grünert, U.; Martin, P.R. Projections of three subcortical visual centers to marmoset lateral geniculate nucleus. J. Comp. Neurol. 2018, 527, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Cavallini, M.; Wang, J.; Xin, R.; Zhang, Q.; Feng, G.; Sanes, J.R.; Peng, Y.-R. Evolutionary and developmental specialization of foveal cell types in the marmoset. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2024, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.J.; Adams, D.L.; Gentry, T.N.; Dilbeck, M.D.; Economides, J.R.; Horton, J.C. Retinal Input to Macaque Superior Colliculus Derives from Branching Axons Projecting to the Lateral Geniculate Nucleus. J. Neurosci. 2024, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).