1. Introduction

Modern multimodal transport systems operate as interconnected and adaptive networks, challenged by scale, diversity, and ever-growing demands. From the classical four-step travel model to network design problems, and from granular pedestrian dynamics to freight and last-mile logistics, the existing transport modeling approaches are struggling to capture system-wide interdependencies and dynamics. Large-scale events, traffic congestion, and demand surges pose additional challenges that traditional tools often fail to represent due to static assumptions, limited behavioral flexibility, and high computational cost. For example, agent-based and simulation-based approaches offer valuable insights into emergent crowd behavior and flow efficiency; however, their scalability remains constrained when applied to dense environments or complex routing scenarios [

1,

2,

3]. In domains such as vehicle routing, traffic assignment, and behavioral simulation for pedestrian flow optimization, classical optimization techniques often fail to handle the combinatorial complexity of real-world constraints, especially under uncertainty and temporal variability [

4,

5,

6]. Inclusive pedestrian mobility is also emerging as a critical priority in urban transport planning [

7]. As cities transition towards rapid urbanisation, demographic aging, and sustainability imperatives, there is a growing demand for transport systems that equitably accommodate diverse user needs. In particular, the safe and efficient movement of older adults, people with disabilities, and other users with mobility limitations has emerged as a key concern for high-density urban environments such as stadiums, transit hubs, and large event precincts. These contexts require adaptive routing strategies in real time that can respond to dynamic congestion, environmental barriers, and user-specific constraints. Recent studies have emphasized the importance of universal design principles, such as barrier-free crossings, priority waiting zones, and inclusive route-finding, to support the autonomy and well-being of these user groups [

8,

9]. However, such features are not yet largely explored in dynamic pedestrian flow simulation and operational transport models. Additionally, large sporting events such as Olympics games result in huge crowds in and around the sporting arena causing significant traffic and pedestrian challenges.

Classical transport modeling approaches, including demand forecasting, traffic assignment, micro-simulation, and agent-based models, have been widely adopted to capture different aspects of system behavior. These tools provide valuable insights, yet they face fundamental limitations when applied at scale or under dynamic and uncertain conditions. Demand forecasting struggles with short-term variability [

10], traffic assignment models become computationally intensive when extended to dynamic or stochastic formulations, and micro-simulations rapidly grow in complexity when representing large networks with heterogeneous users [

11]. Agent-based models provide higher fidelity by modeling individual decision-making, but remain computationally expensive [

12] and difficult to scale for city-wide, real-time scenarios [

13]. Logistics and freight problems such as the classical vehicle routing problem (VRP) and traveling salesman problem (TSP), as well as their variants, are computationally intractable beyond relatively small instances, especially when time windows, congestion, or multimodal constraints are introduced. Across these domains, the common barrier is the combinatorial explosion of possible decisions, which makes it increasingly difficult to balance scalability, behavioral realism, and constraint-aware optimization on classical computing architectures.

Quantum Computing (QC) is a rapidly emerging paradigm which has become a promising area of research for solving combinatorial optimization problems [

14]. Quantum chemistry [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20], finance [

21] and machine learning [

22] science have been early testbeds, where quatum optimization algorithms such as Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) and Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA) have been applied to energy minimization [

20,

23] and portfolio optimization [

24]. These advances motivate the exploration of QC in the transport field, hereby called Quantum Transport Computing, where problems in logistics share similar combinatorial structures and computational bottlenecks. In particular, its application to TSP and VRP through hybrid quantum–classical algorithms has already demonstrated early success for small-scale problems [

25,

26,

27,

28]. Unlike classical solvers that are constrained by combinatorial explosion and limited scalability, quantum algorithms have the potential to explore large decision spaces in a fundamentally new way, which could allow more natural representations of multi-modal interactions, stochastic variations, and behavioral diversity. QC is therefore attracting growing attention within the transport research community for its potential to increase computational power beyond current limits and to overcome the challenges present in the existing modeling and optimization frameworks. While the promise is compelling, key questions remain: Where can quantum computing deliver the greatest impact in transport modeling? How should the field prepare for the opportunities and challenges posed by this technological shift? And what practical steps can be taken now to ensure transport researchers and practitioners are ready to take advantage of quantum advances as the technology matures?

This review addresses these questions by surveying the current state-of-play in quantum computing and exploring its early applications to transport modeling.

Section II introduces the challenges in transport modeling and optimization.

Section III reviews the existing quantum approaches explored to-date in certain types of transport problems.

Section IV provides a forward-looking discussion on the step-by-step transition from proof-of-concept studies to practical deployment, highlighting both the opportunities and the challenges ahead, and identifying future directions for scaling small experimental instances to large, real-world transport systems.

Section V discusses a special case of Olympics Games and provides our perspective to use QC in the Australian 2032 Brisbane Olympics context.

The review has been written to appeal researchers from both transport and quantum computing communities providing ample background on transport problems in Section II and quantum computing methods in section III, and will instigate new ideas for future research enhancing the uptake for the quantum transport computing.

2. Challenges in Transport Modelling and Optimisation

Transport systems face a wide range of operational and planning challenges that affect the movement of people and goods. These challenges originate from variability in demand, constraints in network capacity, and the dynamic nature of real-world operating conditions.

Figure 1 highlights key problems areas where Quantum Transport Computing may enable novel solutions, along with a few widely used quantum algorithms. In the following section, we briefly discuss some of the key challenges that affect the efficiency, reliability, and inclusivity of transport systems.

2.1. Travel Demand Forecasting

In transport networks, mismatches between forecasted and actual demand often lead to overcrowding on some routes while the others remain under-utilised. During peak periods, passengers may be unable to board services due to capacity limits, while parallel routes operate below capacity. When forecasts are inaccurate, transport service providers need to decide how to use the limited resources, such as vehicles and infrastructure, across the network. Typically, this involves adjusting service frequency, re-allocating fleets, and managing capacity to better match actual demand [

29,

30]. Conventional demand forecasting methods mainly rely on historical travel patterns, household surveys, and socio-economic indicators, which are more effective for long-term planning but have limited ability for short-term variations caused by weather events, special occasions, network disruptions, or rapid uptake of emerging transport services. The expansion of emerging mobility options, including ride hailing, shared micro-mobility, and on-demand public transport, has introduced additional uncertainty in when, where, and how people travel. Conventional activity-based modeling frameworks [

31] often assume consistent behavioral patterns that do not fully capture fluctuations in mode choice, trip timing, and destination selection, leading to a persistent gap between the planned capacity and the actual demand.

Forecasting is fundamentally predictive, therefore, quantum machine learning (QML) may provide new ways to capture complex correlations in travel behavior that classical models cannot easily represent. Quantum kernels and hybrid quantum-classical classifiers could support demand prediction in settings with high variability and heterogeneous behavior. However, the allocation of services and schedule of fleets are combinatorial optimization problems. These problems require searching through very large numbers of possible schedules and allocations under strict operational constraints. Quantum optimization approaches may offer advantages in exploring these large solution spaces more efficiently than classical heuristics, especially for real-time adjustments where rapid decision-making is critical.

2.2. Logistics

Urban freight operations face growing pressures, including an increased delivery volume and the operational constraint of dense city networks. These pressures are most acute in last-mile delivery, where high-frequency, time-sensitive consignments require access to limited loading and unloading space in areas already saturated with passenger traffic [

32]. In dense central areas, where access is already restricted, these conditions result in longer delivery times, reduced service reliability, and higher operational costs. To address such issues, optimization models derived from the TSP and its generalization, the VRP, have been widely applied in freight scheduling. Variants of VRP, including time-window, pickup-and-delivery, and multi-depot extensions, provide efficient and effective solutions in static and predictable environments [

33]. However, real-world urban freight operations are highly dynamic. Travel time fluctuates with congestion, delivery locations, and availability of loading zones vary throughout the day.

As illustrated in

Figure 2, real-world vehicle scheduling and routing tasks are characterized by high network density, dynamic disruptions, and complex inter-dependencies. The operational network derived from St. John Ambulance logistics in Queensland (

Figure 2 (a)) highlights the combinatorial complexity multi-vehicle coordination across service points. Real-time traffic data from Brisbane (

Figure 2 (b)) further demonstrates how congestion and spatial dependencies amplify this complexity in practice. The schematic examples in

Figure 2 (c)-(f) represent routing disruptions, including congestion, flooding, roadworks, and incidents, which introduce stochastic variations that are difficult to handle with static optimization. These scenarios highlight the need for adaptive and computationally efficient approaches to support real-time decision-making urban logistics systems. Quantum optimization has already been explored for many logistics tasks that can be formulated as combinatorial optimization problems, such as VRP and TSP. Although current quantum implementations remain limited to small-scale instances, logistics is widely studied as one of the most promising areas where future quantum advances could extend classical optimization methods.

The challenges outlined in this section are diverse in scope; however, many of these problems share a common feature such as decision-making problems that are computationally intensive at scale. Although TAP, TSC, and logistics can be formulated as combinatorial optimization tasks; travel demand forecasting and behavioral modeling in pedestrian flows are aligned with predictive methods, where QML may play a role. In all cases, the underlying challenge lies in the complexity of modeling, optimization, and adaptation under dynamic and uncertain conditions.

2.3. Traffic Assignment Problem

Even when demand forecasts are accurate, transport networks can perform poorly if trips are not allocated properly across available routes. Uneven distribution of flows can lead to severe congestion on certain corridors while the others remain under-utilised. This imbalance is particularly problematic in dense urban systems where small routing shifts can trigger substantial changes in network performance. Traffic assignment problem (TAP) formalizes this challenge by modeling how trips are allocated given the origin-destination (OD) pairs across a network. Two widely adopted formulations are user equilibrium, where each traveler seeks to minimize individual travel cost, and system optimum, which minimizes the overall cost across the network [

34]. Although these formulations provide the foundation for modern transport planning, there are challenges to address. Static models cannot represent how congestion evolves over time, whereas dynamic models such as dynamic traffic assignment (DTA) are more realistic but computationally expensive. Models that incorporate uncertainty in travel times and adaptive route choices improve performance [

35], but further increase complexity. Recently, machine learning (ML) has shown promise for predicting dynamic flows and capturing heterogeneous vehicle interactions [

36,

37]. However, large-scale TAP remains difficult to solve in practice, especially in multimodal settings or when real-time responsiveness is required.

TAP is therefore best understood as a large-scale combinatorial optimization problem. Assigning thousands of trips to network routes under dynamic and uncertain conditions produces a vast solution space that quickly exceeds the capacity of classical solvers, especially when rapid updates are required during disruptions or peak periods. At practical scales, classical solvers struggle with computational limits, making it difficult to obtain timely and reliable solutions, and therefore quantum optimization approaches are worth looking into, as discussed in

Section 3.

2.4. Traffic Signal Control

Signalized intersections are major contributors to congestion. Poor coordination of traffic signals forces vehicles into repeated stop–go cycles, which increase travel time variability and emissions while creating long waits for pedestrians and cyclists. Effective traffic signal control (TSC) is therefore essential in improving both efficiency and equity in urban mobility. Traditional fixed-time control approaches [

38] allocate green phases using historical demand data, but such methods cannot adapt to short-term fluctuations or unexpected disruptions. Vehicle-actuated control [

39] improves responsiveness by adjusting green times in real time with on-site detection, although this approach is generally applied at individual intersections rather than across networks. More advanced methods, such as adaptive signal control, attempt to coordinate signals dynamically across a network using optimization [

40,

41], ML and deep learning (DL) approaches [

42,

43]. Despite promising results in simulations and pilot studies, large-scale deployment remains constrained by computational complexity.

Coordinating signals across an entire network represents a large-scale scheduling problem, which requires the selection of timing plans for many intersections simultaneously under dynamic demand conditions. The number of possible schedules grows exponentially with the size of the network, which poses significant challenges for classical solvers. Quantum optimization has the potential to manage this complexity by significantly efficient search of large scheduling spaces. As traffic signal control is inherently sequential and must adapt to fluctuating demand and disruptions, quantum reinforcement learning (QRL) [

48] may offer a framework for learning control policies that could be adapted to adjust dynamically to evolving traffic conditions.

2.5. Pedestrian Modeling

Pedestrian flow management in high-density environments such as transit hubs, commercial districts, and event venues is a significant challenge. Congestion, delays, and unsafe crowding arise when demand exceeds capacity at entrances, walkways, or crossings [

2,

49]. These pressures are further complicated by the diversity of pedestrian characteristics: walking speed, route choice, and tolerance for delay vary with age, mobility limitations, group dynamics, and the use of assistive devices. Existing control measures, such as one-way routing or temporary barriers, provide only reactive solutions and do not address inclusivity requirements. Pedestrian dynamics have been studied using agent-based models [

50], cellular automata [

51], and social force formulations [

2], and hybrid simulation platforms such as PTV Viswalk [

52], Aimsun Next [

53], and Oasys MassMotion [

54]. While these methods capture local interactions and crowd-level patterns, they are limited to incorporate heterogeneous mobility needs, fatigue effects, and real-time behavioral adaptation [

1,

55]. A key gap lies in behavioral prediction such as forecasting whether individuals will continue, pause, reroute, or switch strategies under changing conditions. This aspect is critical for inclusive mobility but is not well represented in the existing models.

Figure 3 illustrates pedestrian flow challenges in high-density environments. Large-scale crowd accumulation and lane formation around a stadium precinct (

Figure 3 (a)) highlight how macroscopic congestion can emerge rapidly from local interactions.

Figure 3 (b) depicts the friction effects experienced by wheelchair users and pedestrian within mixed-mobility spaces, while

Figure 3 (c) shows the complexity of turning and merging flows under limited space and directional conflict near a stadium entrance.

Figure 3 (d) demonstrates heat maps of pedestrian density, congestion zones and dynamic flow propagation across the network, while diffusion-based formulations (

Figure 3(e) conceptualize route-choice probabilities and temporal transitions between locations.

Pedestrian flow management is traditionally considered as a simulation problem, but it can also be framed as an optimization and prediction challenge. For example, the evaluation of routing and evacuation strategies can be expressed as large-scale combinatorial tasks, where the objective is to assign pedestrians to routes or exits while considering for constraints such as capacity, safety, and accessibility. Classical solvers struggle with these problems at scale, particularly under real-time conditions, whereas quantum optimization approaches are designed to explore such exponentially large solution spaces more effectively. At the same time, QML offers potential for modeling heterogeneous pedestrian behaviors by learning complex correlations in behavioral data, and behavior prediction for more adaptive crowd simulations.

2.6. Self-Driving Transport

Autonomous or self-driving transport is rapidly becoming popular and many applications of this emerging transport medium are being tested and deployed around the world. However, a key challenge in the robust deployment of self-driving transport stems from the unreliability of artificial intelligence (AI) or ML methods, which work remarkably well under trained environments but fail to adapt to dynamic, often unpredictable and noisy real-world scenarios. Furthermore, it has been shown in the recent literature that adversarial perturbations of the datasets during testing and deployment of AI/ML methods lead to complete failure of the decision making process based on these models. For example, cleverly placed stickers on traffic signals could trick AI/ML models to mis-identify, leading to traffic crashes and possible loss of lives. While these problems hinder the wide-spread adaptation of autonomous transport, quantum computing may offer an advantage by addressing reliability issue of AI/ML models. Indeed, recent research has shown that by integrating the power of QC in AI/ML, highly secure and trustworthy quantum AI/ML models can be designed [

22,

56,

57]. Despite promising results based on proof-of-concept simulations, significant more work is needed to deploy and benchmark quantum models in practically relevant autonomous transport applications.

3. State-of-the-Art Quantum Approaches

To date, most applications of quantum computing in transport have focused on logistics problems, particularly the TSP, and its generalization, the VRP due to the combinatorial structure. As networks become larger, denser, and more interdependent, classical solvers begin to struggle with both solution quality and computation time, particularly under real-time and uncertainty conditions. Over the last decade, quantum optimization has emerged as a promising area for addressing combinatorial optimization problems. By leveraging the principles of superposition and entanglement, quantum algorithms can explore large solution spaces in parallel, potentially identifying solutions faster than classical heuristics or metaheuristics for certain types of tasks. Although quantum hardware is still in its noisy intermediate-scale (NISQ) phase, early experimental simulations suggest that for certain problem classes, quantum methods are expected to offer advantages, either in solution quality, speed, or the ability to model complex constraints more naturally [

25,

26,

58]. However, other transport challenges, such as dynamic traffic assignment, congestion management, and inclusive pedestrian flow modeling, have not yet been studied in quantum computing.

This section reviews the state-of-the-art quantum approaches that have been applied for transport relevant optimization tasks. We begin with Quadratic Unconstrained Binary Optimization (QUBO), which defines how a transport optimization task is expressed in a form suitable for quantum computation. Building on this foundation, quantum optimization approaches such as quantum annealing, Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA), and Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) have been developed. Furthermore, other quantum approaches have also been explored such as QML, which have the potential to address transport problems.

Figure 4 (a-c) shows schematic diagrams of QAOA, VQE, and QML architectures. Furthermore, there are also emerging areas of research such as topological data and signal processing [

59,

60] which could play an important role in future intelligent transport modeling.

3.1. QUBO-Based Quantum Algorithms for Combinatorial Optimisation Problems

The QUBO is the foundation for most recent quantum optimization studies in transport. The transport problem, whether it is a VRP, TSP, traffic signal coordination, or crew scheduling, can be represented as a quadratic objective function over binary variables. Each binary variable typically encodes a decision, such as whether a vehicle visits a given location, a signal is set to a particular phase at a given time, or a specific crew member is assigned to a shift. These cost functions represent the objective (e.g., minimize distance or congestion) and constraints (e.g., capacity limits, time windows) as binary variables and penalty terms. Once the QUBO model is formulated, it can be embedded onto quantum hardware. For quantum annealers such as D-Wave, we can map the QUBO graph onto the hardware’s physical qubit connectivity. For gate-based approaches such as quantum approximate optimization algorithm (QAOA) and variational quantum eigensolver (VQE), the QUBO is transformed into a problem Hamiltonian and the algorithm then searches for the ground state of this energy landscape, corresponding to a near-optimal or optimal transport solution.

Early research into quantum solutions for the VRP largely focused on quantum annealing, where the problem is formulated as a QUBO model. One of the foundational studies in this area was reported by [

25], where quantum annealing is applied to a traffic flow optimization problem based on an abstracted model of urban road networks. Using a QUBO formulation, the problem encoded vehicle-route assignments and penalized overlapping paths. Due to hardware limitations, the study relied on hybrid classical-quantum decomposition, highlighting the challenges of scaling QUBO-based routing problems on NISQ-era quantum annealers. To improve scalability, Ref. [

62] proposed a more expressive quantum annealing model for the Multi-Depot Capacitated VRP and its dynamic variant. Their QUBO formulation considered vehicle capacities, depot constraints, and customer demands, using slack variables to encode inequalities. Although this approach enabled real-time rerouting and dynamic logistics applications, it significantly increased the number of required qubits. This poses a major challenge as today’s quantum devices provide only a limited number of qubits, and each qubit is noisy with restricted connectivity. The problem of quantum resource overhead can be reduced by decomposing the VRP into more tractable sub-problems, and separate the vehicle-to-customer assignment phase from the TSP phase [

26]. This allows only the smaller TSP problem to be optimized on quantum hardware, which significantly reduces the qubit requirements.

QAOA is one of the most widely studied gate-based methods for solving combinatorial optimization problems within the NISQ era. The method alternates between applying a problem Hamiltonian, which encodes the QUBO formulation of the problem task, and a mixing Hamiltonian, which explores the feasible solution space. In principle, as the circuit depth increases, QAOA can approach the optimal solution, however, practical implementations on today’s hardware face several constraints. Standard QAOA [

63] mappings require one qubit per binary decision variable. For realistic transport models such as VRP or TSP, hundreds or even thousands of qubits might be required, which is far more than current quantum devices can support. In addition, deeper circuits make quantum states more vulnerable to decoherence and noise.

In recent years, several approaches have been proposed to mitigate these challenges. Ref. [

58] benchmarked QAOA and quantum annealing for the ride-pooling problem (RPP) on IBM and D-Wave platforms. Unlike traditional VRP, RPP does not assume a central depot and allows multiple customers to request on-demand pickups and drop-offs through a shared fleet of vehicles. This variant more closely reflects real-world transport services, such as metro networks, bus routes, and ride-sharing services. However, this study suggests that substantial advancements are still needed. While QAOA currently faces challenges in achieving high-quality solutions on near-tern quantum devices due to noise and limited number of qubits, its performance can be enhanced by hardware-aware modifications, as demonstrated in [

64]. Specifically, this approach introduces connectivity-forced (CF) QAOA, which reduces circuit depth by removing long-range interactions, and CF-multi-angle QAOA, to add variational parameters for improved performance. On IBM Quantum hardware, these variants outperform standard QAOA to minimize traffic congestion, and optimizing routes for up to 23 cars. As the limited number of qubits is one of the most significant bottlenecks for scaling QAOA, a promising research direction is qubit-efficient encoding [

65,

66]. Instead of using conventional one-hot or full binary mappings, minimal and logarithmic encoding schemes reduce the qubit requirements for problems such as the VRP and VRP with time windows from linear to logarithmic in the number of routes. This reduction improves the feasibility of implementing QAOA on current quantum hardware platforms, such as IBM, IonQ, and Rigetti devices. Empirical studies demonstrate that approximate yet practically useful solutions to VRP instances can be obtained using as few as 13 qubits. Indirect QAOA (IQAOA) [

67] is another promising approach which introduces a parameterized set of unitary operators with a classical meta-optimization loop. By reducing circuit depth, IQAOA improves adaptability for noisy quantum devices and has been demonstrated on TSP instances with up to eight customers.

VQE is a hybrid quantum-classical algorithm widely applied in quantum chemistry, simulation, and optimization. VQE iteratively combine quantum circuits with classical optimization to approximate the ground state of a problem Hamiltonian to find low-energy solutions. A recent study [

68] decomposed capacitated VRP into a clustering phase and a set of TSPs and evaluated both QAOA and VQE. The findings indicate that VQE achieves feasible energy thresholds and produce higher-quality solutions, while QAOA struggles to find the required energy threshold for feasible TSP solutions, even when enhanced with techniques such as constraint-preserving mixers. Similarly, ref. [

69] compared both approaches to solve VRP and demonstrates that VQE generally achieved better results on small-scale instances (e.g., up to 5 nodes and 2 vehicles); however, unable to solve instances beyond that on current NISQ devices.

3.2. Other Quantum Approaches

Beyond QUBO-based combinatorial methods such as quantum annealing, QAOA, and VQE, quantum researchers are also exploring quantum machine learning (QML) approaches for transport optimization. One such direction is Quantum Support Vector Machines (QSVMs), which use quantum kernel estimation to perform classification in high-dimensional Hilbert spaces [

70]. Rather than encoding routing constraints explicitly into the cost Hamiltonian, QSVMs can learn patterns from data and offer a data-driven pathway to optimization. Recently, Ref. [

71] applied QSVMs to small-scale VRP instances using hybrid quantum-classical circuits and VQE. Although still limited to small problem sizes, this approach demonstrates how problem structure and constraint validity can be captured through learned quantum decision boundaries. For transport modeling, QSVMs may offer potential for encoding soft constraints or user-specific routing behaviors such as fatigue-aware preferences or accessibility thresholds that are challenging to formulate in traditional QUBO-based formulations. Other QML approaches such as quantum reinforcement learning [

72] and quantum neural networks with reinforcement learning [

73] have also been studied for addressing VRP, however, these approaches are still at the proof-of-concept stage.

Recently, Decoded Quantum Interferometry [

74] has been proposed as a different way to tackle combinatorial optimization problems. Instead of using a problem Hamiltonian like in QAOA or quantum annealing, DQI reformulates the optimization task as a decoding problem for an error-correcting code that represents the problem’s constraints. The method prepares quantum states where the interference patterns are designed to add up good solutions (constructive interference) while discard poor solutions. These interference patterns are created by transforming the objective function into the Fourier domain and then applying specific mathematical operations. Once this quantum state is prepared, efficient decoding algorithms, either classical or quantum are used to identify the best solutions. DQI has already shown strong results in certain structured problems and achieved better solutions than the best known classical methods in some settings. However, This approach has not yet been applied to transport optimization problems.

To date, most quantum optimization techniques have been applied only to logistics problems such as TSP and VRP, whereas travel demand forecasting, traffic assignment, congestion management, and pedestrian movement and accessibility have not been studied yet.

4. Challenges and Opportunities

Quantum computing holds significant potential for advancing transport modeling and optimization, however, substantial challenges need to be addressed before large-scale deployment becomes feasible.

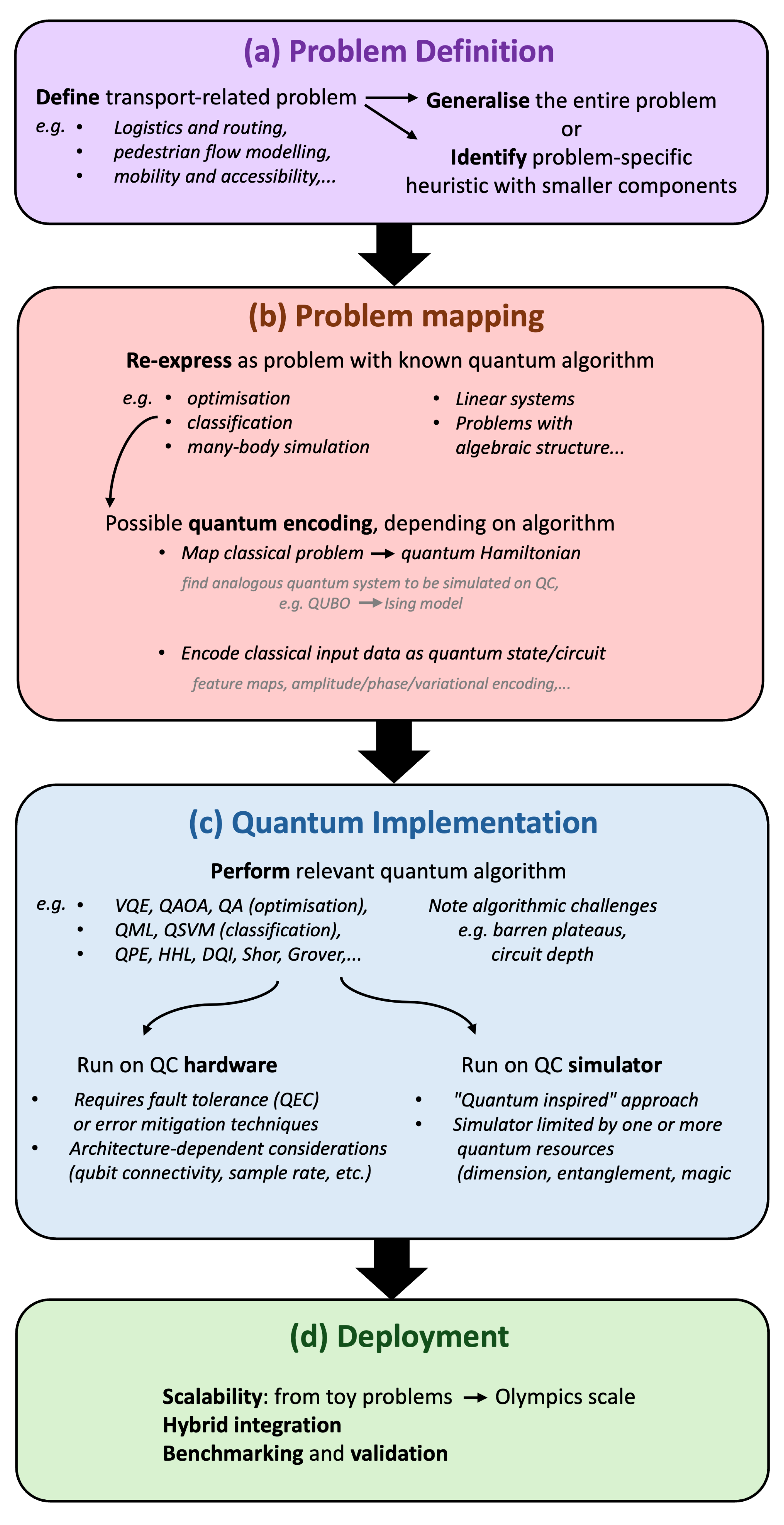

Figure 5 illustrates a schematic of the key stages involved in applying quantum approaches to transport problems, from problem formulation and algorithm selection to implementation on simulators and hardware. These are discussed in detail in the following sections.

4.1. Problem Mapping

Whether we generalize the entire problem or identify the problem-specific smaller components, the real-world transport optimization problems (as discussed in

Section 2) need to be formulated into a representation that is compatible with quantum devices. Most of the existing studies have relied on the QUBO framework, which provides a mathematical formulation to encode problems like the TSP, VRP, and scheduling into a quadratic Hamiltonian form suitable for both quantum annealer and gate-based devices. Early implementations of the QUBO or Ising Hamiltonian based formulation include small-scale routing [

26], and traffic signal coordination [

75,

76,

77] demonstrates that certain subproblems can already be mapped into quantum-ready formulations.

Several transport challenges align naturally within the QUBO framework. TAP can be mapped by representing route allocations as binary variables, where penalty terms can enforce flow conservation and capacity constraints. Congestion management such as re-routing and capacity re-allocation can also be encoded by defining binary variables for intervention choices and incorporating penalties for exceeding link or intersection capacities. Traffic signal coordination can be encoded through binary variables representing the selection of green phases at intersections, with penalty terms ensuring that conflicting movements are avoided and adjacent intersections remain synchronized. Logistics problems such as the TSP and VRP have already been the most extensively studied in quantum optimization literature. Certain pedestrian modeling tasks, such as evacuation planning and crossing allocation, can also be mapped into QUBO, where binary variables represent the assignment of individuals or groups to specific exits or crossing phases, with penalties enforcing walkway limits, exit capacity, and accessibility requirements. Across these transport problems, the combinatorial structure of the decisions makes QUBO a unifying representation, although the scale and complexity of real transport systems introduce significant challenges for practical implementation. Moreover, adapting this general-purpose formulation to realistic transport problems remains a significant challenge, as transport networks are rarely unconstrained. More fundamentally, mapping a real-world combinatorial optimization problem, which likely involves constraints, into a QUBO, where these constraints are mapped to large penalty terms, removes the inherent structure of the problem that is exploited by the state-of-the-art classical solvers.Constraint encoding requires large penalty coefficients that can distort optimization landscapes, leading to poor convergence or infeasibility when implemented on near-term quantum devices [

78,

79].

However, not all transport challenges are naturally combinatorial. TDF, for example, is a predictive task which can be considered as a QML. QML approaches require to encode classical transport data such as socio-economic variables, demand fluctuations, and behavioral features into quantum states. Different encoding strategies have been studied in QML, such as, amplitude encoding [

80], angle or phase encoding [

80], and approximate encoding [

81]. Amplitude encoding can be used to represent high-dimensional transport data in quantum states, while angle encoding is well suited to map temporal and categorical features. Pedestrian behavioral modeling such as prediction of walking speed distributions, group coordination, and delay tolerance can also be framed as classification or regression QML tasks where behavioral features need to encoded into quantum states. Transport datasets, however, are often high-dimensional and heterogeneous, and the selection of encoding strategies will strongly influence the performance and robustness of QML models. To date, such encoding schemes in QML have been explored in proof-of-concept studies on simplified and down-scaled datasets. Adapting these techniques to the real-world transport data has not yet been studied. Developing encoding strategies that can capture the structural and statistical characteristics of transport systems will therefore be an important direction for future research.

4.2. Quantum Implementation

In recent years, several techniques have been proposed for quantum optimization as discussed in

Section 3. Despite the potential to adopt these quantum approaches to transport modeling and optimization, the transition from theoretical formulation to practical application in transport such as vehicle routing, accessibility-aware routing, and pedestrian flow management poses significant methodological and implementation challenges. Gate-based approaches such as the QAOA and VQE offer a variational framework for solving combinatorial and constrained optimization tasks. Refinements such as feasibility-preserving mixers, and warm-starts from classical heuristics have been shown to stabilize training and reduce circuit depth for routing and congestion minimization. However, scaling to realistic transport networks requires hundreds or thousands of qubits, while noisy optimization landscapes, barren plateaus, and the sensitivity of penalty weights for hard constraints remain unresolved barriers. Although hardware-aware variants of QAOA [

64] and qubit-efficient encoding strategies have been applied on small-scale benchmarks [

65] for traffic congestion and logistics, deployment to large, dynamic, and heterogeneous transport environments has not yet been demonstrated. In pedestrian modeling problem, further challenges arise, where walkway capacity, accessibility requirements, and crowd safety need to be encoded simultaneously.

QML models can be developed for demand forecasting, pedestrian flow prediction, and accessibility-aware routing, where improved predictive accuracy and adaptability could directly support operational planning and real-time control. QML has shown promising potential in other domains such as molecular property prediction in quantum chemistry [

82], phase recognition in materials science [

83], semiconductor fabrication optimization [

84], processing sensor datasets [

85], event classification in high-energy physics [

86,

87], and computer vision tasks such as image generation [

88,

89], and image classification [

90,

91,

92]. Although QML has not been widely explored in transport problems, there is a potential to handle complex, multi-modal transport data, including temporal demand profiles, spatial network structures, and heterogeneous user behaviors. Kernel-based QML models, such as QSVMs, could be used for classification tasks such as predicting congestion states or identifying accessibility-critical conditions. Variational quantum classifiers and quantum neural networks may support adaptive crowd management, where real-time sensor data must be translated into safe and efficient routing strategies. At the same time, transport data are high-dimensional, and dynamic which raises questions that how QML models can remain robust to data uncertainty. Furthermore, existing demonstrations of QML have been limited to down-scaled datasets. Practical implementations will also require integration of QML outputs with optimization routines to ensure that the prediction outputs can be embedded directly into decision-support frameworks for scheduling, routing, and infrastructure planning.

Beyond QAOA, VQE, and QML, other approaches could be explored. DQI [

74] reformulates optimization as a decoding task rather than an energy-minimization problem. By exploiting interference patterns to reinforce feasible solutions and suppress infeasible ones, DQI could be valuable for transport applications that require the joint optimization of constrained tasks, such as multi-vehicle routing with accessibility restrictions or evacuation scheduling under safety-critical conditions. Unlike QUBO-based formulations, DQI may reduce the dependence on large penalty weights that distort optimization landscapes in QAOA. However, there is no clear framework for encoding real-world transport constraints into interference patterns, and scaling beyond toy instances remains an open challenge. State-transfer inspired heuristics offer another direction, rapid optimization methods [

93] based on optimal state-transfer Hamiltonians achieve higher approximation quality at minimal circuit depth and could be adapted for fast re-routing and traffic signal coordination. Variants of QAOA, such as the progressive quantum algorithm [

94] explore progressive subgraph expansion to approximate high-quality solutions while requiring significantly fewer qubits, and could therefore be promising for conflict-free scheduling and resource allocation in transport systems. Reinforcement learning provides further opportunities for transport tasks characterized by sequential decision-making under uncertainty, such as adaptive traffic signal control, real-time re-routing, fleet dispatch, and pedestrian evacuation management. It has the potential to accelerate the convergence of variational algorithms and improve adaptive policy learning in dynamic settings [

48]. Policy-based quantum reinforcement learning, where quantum circuits are embedded directly into decision policies, has demonstrated improved performance in sequential decision-making tasks [

95,

96]. This might be particularly relevant to pedestrian mobility, where evacuation scheduling, dynamic exit allocation, and accessibility-aware routing can be modeled as agent-based systems that require adaptive strategies. Other Quantum algorithms such as Harrow-Hassidim-Lloyd (HHL) [

97], Grover’s [

98,

99], Shor’s algorithm [

100] Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE) [

101] have been successfully shown to outperform classical methods in theory, although not yet demonstrated on real hardware or applied to any problems in the transport field. Finally, recent work on trustworthy and robust QML [

22,

56] can play an important role in the adaptation of secure self-driving transport.

Although early quantum demonstrations provide proof-of-concept viability for small-scale transport problems, realistic deployment remains constrained by data encoding challenges, hardware limitations, and the difficulty of scaling models to capture the dynamic and heterogeneous nature of transport systems.

4.3. Hardware Challenges

Despite progress in problem mapping and algorithmic design, the application of quantum optimization to transport systems is also constrained by the limitations of current hardware. Present-day quantum devices provide only a limited number of qubits, restricted connectivity, and short coherence times, which significantly limit the scale and fidelity of problems that can be solved. Many transport optimizations tasks, such as city-wide vehicle routing, multimodal traffic assignment, signal coordination across intersections, require thousand of binary decision variables, which is well beyond the capacity for current quantum processors. The gap between the size of realistic transport instances and the resources available on existing hardware is a major barrier to practical deployment. Noise and decoherence bring additional challenges. On noisy hardware, errors accumulate quickly, reducing the probability of achieving reliable solution. This problem becomes more severe when penalty terms are used to enforce constraints such as vehicle capacity, flow balance, safety margins, since even small hardware-induced errors can cause invalid solutions.

Furthermore, transport models are subject to multiple constraints, including capacity, timing, accessibility, and safety. On quantum hardware, these constraints are usually enforced by penalty coefficients embedded in the objective function. However, the limited precision of coupling strengths on annealers and the sensitivity of variational circuits on gate-based processors make it difficult to balance these penalties. If penalty weights are set too high, the optimization landscape may become distorted and hinder convergence. If penalty weights are set too low, the optimizer may provide solutions that break critical constraints, for example, assigning more vehicles than available, exceeding passenger capacity, ignoring accessibility requirements as such violations do not add enough cost to the objective function. These outcomes may look mathematically valid but are infeasible in real transport systems.

Challenges also arise from the architectural characteristics of current devices. Restricted connectivity in superconducting processors, for example, complicates the encoding of dense urban networks where many routes or intersections interact simultaneously. Trapped-ion systems offer better connectivity and longer coherence times, which are beneficial for assignment-style problems, though slower gate speeds limit their scalability. Neutral-atom arrays have shown progress in solving graph-based optimization problems such as the maximum independent set [

102], which aligns with certain transport formulations, but practical applications remain at the proof-of-concept stage. These architectural differences highlight that only carefully scoped transport subproblems, such as small routing clusters, localized congestion hotspots, or simplified scheduling tasks are currently tractable. Bridging the gap between small-scale demonstrations and realistic, city-wide systems will require advances not only in hardware capacity and error correction but also in problem simplification and hybrid decomposition strategies that align transport structures with device-specific capabilities.

On a positive note, the field of quantum hardware development has been advancing at a remarkable pace. Quantum processors are being developed around the world by major industry players such as IBM, Google, Intel and others along with many newly established start-ups and universities.

Figure 4 (d) and (e) shows examples of quantum processors developed by IBM and QuEra respectively which already consists of hundred of qubits. There are several ambitious road-maps, which aim to build large-scale quantum processors within the next decade, which should place quantum solutions for many of the aforementioned transport and logistics problems within the possibility of practical implementation. Furthermore, the field of quantum error correction is also progressing very fast in which several noisy physical qubits are used to encode error-protected logical qubits.

Figure 4 (f) plots simulation results which show number of error protected quantum operations as a function of the physical error rates in qubits when the error correction code distance d is varied. A larger distance d implies that more qubits are used to encode error-protected quantum operations. For example, if the physical error rate of qubits is 0.1%, a distance d=15 code (around 225 physical qubits per single error protected qubit) will allow roughly 10

7 quantum operations. As the development of quantum processors advances, it is anticipated that quantum error correction codes over larger distances will be implemented allowing deeper quantum circuits to be implemented commesurate with real-world applications. Remarkably, the implementation of quantum error correction methods have already transitioned from theoretical developments to practical implementations and benchmarking [

103,

104,

105,

106,

107,

108].

Figure 4 (g) shows recent results from Google Quantum AI [

61] which demonstrate error suppression when code distance is increased to distance 7, offering further hope that larger-scale error-protected quantum processors may become available to make Quantum Transport Computing a reality.

4.4. Software Challenges

Due to the quantum hardware challenges, software frameworks have become an essential bridge between theory and practice. Platforms such as Qiskit and Pennylane will allow researchers to design, test, and benchmark transport-specific optimization strategies in advance of scalable hardware. These environments accelerate algorithmic development, and prepare the research community for future fault-tolerant devices. However, current simulators run on classical processors and quickly encounter memory and runtime issues as the number of qubits increases, which limits the experiments to small-scale instances. The highly entangled states further increase computational overhead, while noise models built into simulators provide only approximate representations of hardware behavior, leaving gaps between simulated results and real device performance.

4.5. Deployment

Once transport problems are mapped into quantum-ready formulations and quantum algorithms are developed, the next step is to scale from toy problems to the full complexity of real world transport systems. While the hardware challenges section highlighted the limitations of current quantum devices, a key question is how these algorithms perform under operational conditions. Mega-events such as the Olympic and Paralympic Games illustrate the pressures that future deployments need to address sudden peaks in multimodal demand, dense pedestrian flows, dynamic disruptions, and accessibility requirements. These represent highly relevant testbeds for assessing whether quantum approaches can move beyond proof-of-concept and implement for practical optimization at large scale. Problems such as large-scale vehicle routing, demand responsive scheduling, adaptive signal coordination, and pedestrian evacuation expand exponentially with network size. Even when hardware constraints are mitigated through hybrid architectures, quantum algorithms need to demonstrate consistent improvements when applied to datasets involving hundreds of thousands of trips or heterogeneous mobility needs. One promising pathway is modular deployment, where quantum solvers target subproblems such as localized congestion hotspots, accessibility aware routing for wheelchair accessible fleets, or crowd re-routing under disruptions, while classical methods maintain broader system coordination. For deployment to be viable, quantum solutions also need to be embedded within the simulation and control frameworks already used in transport planning and operations. This requires interoperability with classical optimization engines, traffic management systems, and agent-based simulations, ensuring that quantum-derived outputs can directly inform real-time decisions. Benchmarking and validation against classical baselines will therefore be essential. While there are significant challenges of scalability, integration, validation, and the near-term advantages of quantum approaches are likely to be limited, early deployments of quantum algorithms in transport can build the foundation for future large-scale adoption once hardware and algorithmic maturity converge.

5. Olympics 2032 Games – An Australian Case Study

Transport challenges such as traffic congestion during peak hours and unexpected delays due to road incidents influence everyday life. However, big sporting events like Olympics Games are unique scenarios which lead to significant and serious disruptions over a short period of time. These events are often attended by hundreds of thousands of spectators which heavily strain transport and logistics resources whether it is related to the capacity of roads to accommodate traffic or public transport for spectators to move around. Furthermore, in and around the sporting arena, thousands of spectators require efficient pedestrian flow management to ensure public safety. In this section, we discuss a case study which is based on our in-progress project in Australia to implement novel QC models for Olympics 2032 games scheduled to be held in Brisbane Australia [

109]. The project which is funded through the Queensland Government Quantum Challenge 2032 program brings together complementary expertise from researchers with diverse backgrounds including quantum computing experts from CSIRO and transport modeling experts from Griffith University. The research team has expertise in travel behavior, pedestrian modeling and accessible transport, essential to developing appropriate algorithms, including a key paper on pedestrian level-of-service calculation [

110]. In the past, they have developed innovative algorithm portfolios-based evolutionary optimization for optimizing complex and large-scale instances of logistics planning problems [

111] (1st of 43 journals in Industrial Engineering) and [

112] (Q1 in Industrial & Manufacturing Engineering). Furthermore, the team has relevant expertise in data analytics, modeling and optimization of complex and multimodal transportation and logistics systems. These transport related skills are complemented by deep QC expertise, which include developing quantum optimization and quantum machine learning frameworks for logistics and transport management.

The project aims to focus on two aspects of quantum development:

Pedestrian crowd dynamics and pinch-points in locations around Southbank, the Brisbane CBD and Milton will trigger the pre conditions for crowd crushes to occur. This project will develop modelling that can help mitigate against events like the 2010 German Love Parade crush (21 dead; 652 injured) [

113] and 2022 Seoul Halloween crush (159 killed; 196 injured) [

114].

The Games fleet of maxi-taxis and community transport vehicles is going to be worked extremely hard servicing over 1,000 wheelchair users per day. Emphasis will be on managing the dynamic and often unpredictable nature of such movements. By factoring in potential disruptions and variations in demand, quantum computing algorithms will be developed with the capability of rapidly generating alternative schedules and resource allocations, ensuring a seamless and resilient operation even in the face of unexpected challenges. The work on this wheelchair vehicle optimization system will be packaged and delivered to the Queensland State’s maxi-taxi operators for their ongoing use beyond the Games.

The project team aims to work with both The Department of Transport and Main Roads (TMR) and Brisbane City Council (BCC) to ensure that the research findings can be adopted and implemented during the operations and delivery phases of the Games. The project is timed to prepare the transport modeling industry for the arrival of significant local quantum capacity. Although the project will run from 2025 to 2028, the objective it to continue development and benchmarking of the quantum solutions beyond the funding period, leading to the scale up of our quantum algorithms in conjunction with the scaling of the quantum processors. The Queensland Government and the Australian Federal Government has recently announced an investment of

$940 Million in PsiQuantum [

115] to build a large-scale error-corrected quantum processor by 2029. This and similar capacity should be available before the 2032 Olympics and Paralympics games, allowing our quantum solutions to be deployed directly on the sites and the transport systems of Southeast Queensland.

Of particular focus moving forward will be: whether the same methods can better optimize: (i) athlete shuttle bus logistics, (ii) spectator shuttle buses; and/or, (iii) the operations of micromobility (public e-scooters and e-bikes), to better service travel during the Games. The team has already established a research partnership with the Brisbane City micromobility operator (BEAM) to better understand visitor travel during events, to assist this agenda.

This case study features a unique QC capability purposely developed to address challenging transport scenarios which in the past have led to significant disruptions and public safety issues. The timeline of the project is coincided with the anticipated development of QC hardware to target large-scale real-world deployment demonstrating quantum benefits. The successful delivery of the project will be the first ever application of QC in Olympics Games and will have broader application for other large sporting events around the world.

6. Outlook

This review has outlined major challenges covering a broad range of transport modeling and optimization tasks, the opportunities and the barriers of quantum implementation for addressing these challenges, and the possible way forward for scaling proof-of-concept studies to large-scale, real-world transport applications. Among the wide range of transport applications, problems with a combinatorial structure, such as vehicle routing, dynamic traffic assignment, and evacuation scheduling offer the highest near-term potential for quantum optimization. These problems can be naturally mapped to quantum formulations and decomposed into subproblems that are feasible with the limited scale of current quantum devices. Predictive tasks such as travel demand forecasting and behavioral modeling in pedestrian flows present different challenges, which require high-dimensional and heterogeneous data representations. Therefore, quantum machine learning and quantum cellular automata may offer advantages with efficient encoding strategies that can capture transport-specific features such as temporal fluctuations, multimodal interactions, and accessibility constraints.

Quantum adoption in transport will require systematic assessment of where the greatest computational bottlenecks exist in classical methods, and where quantum approaches can realistically provide advantages. While existing quantum approaches have the potential to address some of the transport challenges, new methods and algorithms are needed, especially for demand forecasting, pedestrian modeling, and accessibility-aware routing problems. To address current quantum hardware and software challenges, transport problems may need to be reformulated into structures that are more compatible with current devices. Decomposition into smaller subproblems can make large optimization more scalable for near-term quantum devices, while qubit-efficient techniques can be developed to reduce computational challenges. Hybrid classical-quantum frameworks can help bridge the gap between proof-of-concept demonstrations and realistic applications. These directions provide pathways for developing quantum approaches to advance transport research, and can be scaled up to address large-scale scheduling, pedestrian flow management, and accessible-aware routing, which will pose significant challenges in mega-events such as 2032 Olympic and Paralympic Games.

The field of quantum computing is rapidly progressing. Within the last decade, several quantum processor platforms have been developed which already offer quantum devices with qubit numbers ranging from a few hundreds to thousand. The quality of qubits and quantum operations is also improving and recent devices have shown considerably lower error rates compared to earlier generations. Additionally, developments in quantum software layers including quantum error correction, quantum control, quantum error mitigation, transpilation, and resource optimization have drastically improved the performance of quantum devices. Although the current generation of quantum devices remain limited in their capability to implement full-scale transport problems, it is anticipated that future progress on both quantum hardware and software fronts should enable practically relevant Quantum Transport Computing. A particularly exciting opportunity is to be able to develop use cases for Olympics and Paralympics 2032 Games in Australia, which may coincide with the timeline of useful quantum computing.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge funding from the Queensland Government through the Department of Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation’s (DETSI) Quantum 2032 Challenge Program. The program aims to accelerate the development of quantum-based innovations in sportstech and related fields, foster collaboration between Queensland’s quantum research sector and industry, and showcase the state’s quantum expertise on the global stage during the Brisbane 2032 Olympic and Paralympic Games, contributing to the lasting legacy of the Games.

References

- Dang, H.T.; Gaudou, B.; Verstaevel, N. A literature review of dense crowd simulation. Simulation Modelling Practice and Theory 2024, 134, 102955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbing, D.; Molnar, P. Social force model for pedestrian dynamics. Physical review E 1995, 51, 4282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachmi Khemlani. LEGION and the Technology of Pedestrian Simulation, 2018. Accessed: 2025-06-10.

- Schadschneider, A.; Klingsch, W.; Klüpfel, H.; Kretz, T.; Rogsch, C.; Seyfried, A. Evacuation dynamics: Empirical results, modeling and applications. In Extreme environmental events; Springer, 2011; pp. 517–550. [Google Scholar]

- Somvanshi, S.; Islam, M.M.; Polock, S.B.B.; Chhetri, G.; Anderson, D.; Dutta, A.; Das, S. Quantum computing in transportation engineering: a survey. Available at SSRN 5141686 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Yarkoni, S.; Neukart, F.; Tagle, E.M.G.; Magiera, N.; Mehta, B.; Hire, K.; Narkhede, S.; Hofmann, M. Quantum shuttle: traffic navigation with quantum computing. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 1st ACM SIGSOFT international workshop on architectures and paradigms for engineering quantum software; 2020; pp. 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Du, B.; Zheng, Z.; Shen, J. Space sharing between pedestrians and micro-mobility vehicles: A systematic review. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 2023, 116, 103629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Saiz, A.; Baquero Larriva, M.T.; Jiménez Martín, D.; Alonso, A. Enhancing Urban Mobility for All: The Role of Universal Design in Supporting Social Inclusion for Older Adults and People with Disabilities. Urban Science 2025, 9, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokolo, A.J. Inclusive and safe mobility needs of senior citizens: Implications for age-friendly cities and communities. Urban Science 2023, 7, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soon, K.L.; Chan, R.K.C.; Lim, J.M.Y.; Parthiban, R. Short-term traffic forecasting model: prevailing trends and guidelines. Transportation safety and environment 2023, 5, tdac058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghandeharioun, Z.; Zendehdel Nobari, P.; Wu, W. Exploring deep learning approaches for short-term passenger demand prediction. Data Science for Transportation 2023, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorca, C.; Moeckel, R. Effects of scaling down the population for agent-based traffic simulations. Procedia Computer Science 2019, 151, 782–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smilovitskiy, M.; Olmez, S.; Richmond, P.; Chisholm, R.; Heywood, P.; Cabrejas, A.; van den Berghe, S.; Kobayashi, S. Overcoming computational complexity: a scalable agent-based model of traffic activity using FLAME-GPU. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Practical Applications of Agents and Multi-Agent Systems. Springer; 2024; pp. 240–251. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, S.S.; Kumar, A.; Singh, H.; Singh, M.; Kaur, K.; Usman, M.; Buyya, R. Quantum computing: A taxonomy, systematic review and future directions. Software: Practice and Experience 2022, 52, 66–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Karim, A.; Quiney, H.M.; Usman, M. Full band-structure calculation of semiconducting materials on a noisy quantum processor. Phys. Rev. A 2024, 110, 062415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, A.; Zhang, S.; Usman, M. Low depth virtual distillation of quantum circuits by deterministic circuit decomposition. Phys. Rev. Res. 2024, 6, 033223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Karim, A.; Quiney, H.M.; Usman, M. Symmetry-Checking in Band Structure Calculations on a Noisy Quantum Computer. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.20483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, A.; Zhang, S.; Usman, M. Fast and Noise-aware Machine Learning Variational Quantum Eigensolver Optimiser. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.20210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Hill, C.D.; Usman, M. Comparative analysis of error mitigation techniques for variational quantum eigensolver implementations on IBM quantum system. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.07907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peruzzo, A.; McClean, J.; Shadbolt, P.; Yung, M.H.; Zhou, X.Q.; Love, P.J.; Aspuru-Guzik, A.; O’brien, J.L. A variational eigenvalue solver on a photonic quantum processor. Nature communications 2014, 5, 4213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouland, A.; van Dam, W.; Joorati, H.; Kerenidis, I.; Prakash, A. Prospects and challenges of quantum finance. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2011.06492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, M.T.; et al. Towards quantum enhanced adversarial robustness in machine learning. Nat Mach Intell 2023, 5, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandala, A.; Mezzacapo, A.; Temme, K.; Takita, M.; Brink, M.; Chow, J.M.; Gambetta, J.M. Hardware-efficient variational quantum eigensolver for small molecules and quantum magnets. nature 2017, 549, 242–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodson, M.; Ruck, B.; Ong, H.; Garvin, D.; Dulman, S. Portfolio rebalancing experiments using the quantum alternating operator ansatz. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1911.05296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neukart, F.; Compostella, G.; Seidel, C.; Von Dollen, D.; Yarkoni, S.; Parney, B. Traffic flow optimization using a quantum annealer. Frontiers in ICT 2017, 4, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feld, S.; Roch, C.; Gabor, T.; Seidel, C.; Neukart, F.; Galter, I.; Mauerer, W.; Linnhoff-Popien, C. A hybrid solution method for the capacitated vehicle routing problem using a quantum annealer. Frontiers in ICT 2019, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, C.D.; Marsh, S.; Carvalho, A.R.; Kilby, P.; Biercuk, M.J. Quantum computing for transport optimization. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.07313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmasola, V.; Li, Z.; Chatterjee, R.; Dyk, W. Solving the Traveling Salesman Problem via Different Quantum Computing Architectures. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.17725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puignau Arrigain, S.A.; Pons-Prats, J.; Saurí Marchán, S. New Data and Methods for Modelling Future Urban Travel Demand: A State of the Art Review. In Computation and Big Data for Transport: Digital Innovations in Surface and Air Transport Systems; Diez, P., Neittaanmäki, P., Periaux, J., Tuovinen, T., Pons-Prats, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp. 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Thakuriah, P.; Ampountolas, K. Short-term prediction of demand for ride-hailing services: A deep learning approach. Journal of Big Data Analytics in Transportation 2021, 3, 175–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, C.R.; Srinivasan, S.; Guo, J.Y.; Sivakumar, A. Activity-based travel-demand modeling for metropolitan areas in Texas: A micro-simulation framework for forecasting. Work 2003, 4080, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, J.; Browne, M.; Woodburn, A.; Leonardi, J. The role of urban consolidation centres in sustainable freight transport. Transport reviews 2012, 32, 473–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, T.; Laporte, G.; Matl, P. A concise guide to existing and emerging vehicle routing problem variants. European Journal of Operational Research 2020, 286, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheffi, Y. Urban transportation networks; Vol. 6, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1985.

- Graf, L.; Harks, T.; Markl, M. Stochastic Prediction Equilibrium for Dynamic Traffic Assignment. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.12650. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Meidani, H. Heterogeneous graph sequence neural networks for dynamic traffic assignment. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.04131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Meidani, H. Multi-class traffic assignment using multi-view heterogeneous graph attention networks. Expert Systems with Applications 2025, 286, 128072. [Google Scholar]

- Papageorgiou, M.; Diakaki, C.; Dinopoulou, V.; Kotsialos, A.; Wang, Y. Review of road traffic control strategies. Proceedings of the IEEE 2003, 91, 2043–2067. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.B.; Yin, K.; Liu, H. Vehicle actuated signal performance under general traffic at an isolated intersection. Transportation research part C: emerging technologies 2018, 95, 582–598. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, C.; Ding, Y.; Yang, K.; Zhu, H.; Tang, K. Connected vehicle data-driven robust optimization for traffic signal timing: Modeling traffic flow variability and errors. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.14108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Li, W.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Li, L.; Li, D. Scalable multi-objective optimization for robust traffic signal control in uncertain environments. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.13388. [Google Scholar]

- Miletić, M.; Ivanjko, E.; Gregurić, M.; Kušić, K. A review of reinforcement learning applications in adaptive traffic signal control. IET Intelligent Transport Systems 2022, 16, 1269–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Wu, J.; Shen, J.; Du, B.; Telikani, A.; Fahmideh, M.; Liang, C. Distributed agent-based deep reinforcement learning for large scale traffic signal control. Knowledge-Based Systems 2022, 241, 108304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenAI. Conceptual mock-up. https://openai.com/research/dall-e, 2025. Accessed: 10 Oct. 2025.

- Oasys. Case Studies. https://www.oasys-software.com/case-studies/commercial-lobby-south-korea/, 2025. Accessed: 10 Oct. 2025.

- Wirz, M.; Franke, T.; Roggen, D.; Mitleton-Kelly, E.; Lukowicz, P.; Tröster, G. Inferring Crowd Conditions from Pedestrians’ Location Traces for Real-Time Crowd Monitoring during City-Scale Mass Gatherings. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE 21st International Workshop on Enabling Technologies: Infrastructure for Collaborative Enterprises; 2012; pp. 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, W.; Duives, D.; Hoogendoorn, S. A learning based pedestrian flow prediction approach with diffusion behavior. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies 2025, 179, 105243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairy, S.; Shaydulin, R.; Cincio, L.; Alexeev, Y.; Balaprakash, P. Reinforcement-learning-based variational quantum circuits optimization for combinatorial problems. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1911.04574. [Google Scholar]

- Daamen, W.; Hoogendoorn, S.P. Experimental research of pedestrian walking behavior. Transportation research record 2003, 1828, 20–30. [Google Scholar]

- Pluchino, A.; Garofalo, C.; Inturri, G.; Rapisarda, A.; Ignaccolo, M. Agent-based simulation of pedestrian behaviour in closed spaces: a museum case study. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1302.7153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blue, V.J.; Adler, J.L. Cellular automata microsimulation for modeling bi-directional pedestrian walkways. Transportation Research Part B: Methodological 2001, 35, 293–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Xue, S.; Feliciani, C.; Shiwakoti, N.; Lin, J.; Li, D.; Ye, Z. Verifying the applicability of a pedestrian simulation model to reproduce the effect of exit design on egress flow under normal and emergency conditions. Physica A: statistical mechanics and its applications 2021, 562, 125347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barceló, J.; Casas, J. Dynamic network simulation with AIMSUN. In Simulation approaches in transportation analysis: Recent advances and challenges; Springer, 2005; pp. 57–98. [Google Scholar]

- Rivers, E.; Jaynes, C.; Kimball, A.; Morrow, E. Using case study data to validate 3D agent-based pedestrian simulation tool for building egress modeling. Transportation Research Procedia 2014, 2, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Lo, S.; Ma, J.; Wang, W. An agent-based microscopic pedestrian flow simulation model for pedestrian traffic problems. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2014, 15, 992–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, M.T.; et al. Benchmarking adversarially robust quantum machine learning at scale. Physical Review Research 2023, 5, 023186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, N.; West, M.T.; Southwell, A.; Nakhl, A.C.; Sevior, M.; Usman, M.; Modi, K. Adversarial robustness guarantees for quantum classifiers. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.10360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosendo, B.; Fortunato, D.; Abreu, R. Quantum Approaches for Vehicle Routing Optimization on NISQ Platforms. IEEE Software 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Leditto, C.M.G.; Southwell, A.; Tonekaboni, B.; Usman, M.; Modi, K. Quantum HodgeRank: Topology-based rank aggregation on quantum computers. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2025, 23, L061005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leditto, C.M.; Southwell, A.; Tonekaboni, B.; White, G.A.; Usman, M.; Modi, K. Topological signal processing on quantum computers for higher-order network analysis. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2025, 23, 054054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AI, G.Q.; et al. Quantum error correction below the surface code threshold. Nature 2025, 638, 920–926. [Google Scholar]

- Harikrishnakumar, R.; Nannapaneni, S.; Nguyen, N.H.; Steck, J.E.; Behrman, E.C. A quantum annealing approach for dynamic multi-depot capacitated vehicle routing problem. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.12478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhi, E.; Goldstone, J.; Gutmann, S. A quantum approximate optimization algorithm. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1411.4028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, J.; Mooney, G.J.; Bardhan, B.R.; Ghosh, J.; Hill, C.D.; Hollenberg, L.C. Hybrid quantum optimization in the context of minimizing traffic congestion. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.08275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidas, I.D.; Dukakis, A.; Tan, B.; Angelakis, D.G. Qubit efficient quantum algorithms for the vehicle routing problem on Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum processors. Advanced Quantum Technologies 2024, 7, 2300309. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, B.; Lemonde, M.A.; Thanasilp, S.; Tangpanitanon, J.; Angelakis, D.G. Qubit-efficient encoding schemes for binary optimisation problems. Quantum 2021, 5, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourreau, E.; Fleury, G.; Lacomme, P. Indirect quantum approximate optimization algorithms: application to the TSP. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.03294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palackal, L.; Poggel, B.; Wulff, M.; Ehm, H.; Lorenz, J.M.; Mendl, C.B. Quantum-assisted solution paths for the capacitated vehicle routing problem. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Quantum Computing and Engineering (QCE). IEEE; 2023; Vol. 1, pp. 648–658. [Google Scholar]

- Alsaiyari, M.; Felemban, M. Variational quantum algorithms for solving vehicle routing problem. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Smart Computing and Application (ICSCA). IEEE; 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Havlíček, V.; Córcoles, A.D.; Temme, K.; Harrow, A.W.; Kandala, A.; Chow, J.M.; Gambetta, J.M. Supervised learning with quantum-enhanced feature spaces. Nature 2019, 567, 209–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, N.; Behera, B.K.; Ferrie, C. Solving the vehicle routing problem via quantum support vector machines. Quantum Machine Intelligence 2024, 6, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanches, F.; Weinberg, S.; Ide, T.; Kamiya, K. Short quantum circuits in reinforcement learning policies for the vehicle routing problem. Physical Review A 2022, 105, 062403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correll, R.; Weinberg, S.J.; Sanches, F.; Ide, T.; Suzuki, T. Quantum neural networks for a supply chain logistics application. Advanced Quantum Technologies 2023, 6, 2200183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, S.P.; Shutty, N.; Wootters, M.; Zalcman, A.; Schmidhuber, A.; King, R.; Isakov, S.V.; Babbush, R. Optimization by decoded quantum interferometry. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.08292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Lin, C.Y.; Huang, C.I.; Lin, F.P. Quantum annealing approach for the optimal real-time traffic control using QUBO. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/ACIS 22nd International Conference on Software Engineering, Artificial Intelligence, Networking and Parallel/Distributed Computing (SNPD); IEEE; pp. 74–81.

- Inoue, D.; Okada, A.; Matsumori, T.; Aihara, K.; Yoshida, H. Traffic signal optimization on a square lattice with quantum annealing. Scientific reports 2021, 11, 3303. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, H.; Javaid, M.B.; Khan, F.S.; Dalal, A.; Khalique, A. Optimal control of traffic signals using quantum annealing. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.07134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, F.; Kochenberger, G.; Hennig, R.; Du, Y. Quantum bridge analytics I: a tutorial on formulating and using QUBO models. Annals of Operations Research 2022, 314, 141–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayodele, M. Penalty weights in QUBO formulations: Permutation problems. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Evolutionary Computation in Combinatorial Optimization (Part of EvoStar). Springer; 2022; pp. 159–174. [Google Scholar]

- LaRose, R.; Coyle, B. Robust data encodings for quantum classifiers. Physical Review A 2020, 102, 032420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, M.T.; et al. Drastic Circuit Depth Reductions with Preserved Adversarial Robustness by Approximate Encoding for Quantum Machine Learning. Intelligent Computing 2024, 3, 0100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, G.A.; Mucelini, J.; Soares, M.D.; Prati, R.C.; Da Silva, J.L.; Quiles, M.G. Machine learning prediction of nine molecular properties based on the SMILES representation of the QM9 quantum-chemistry dataset. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A 2020, 124, 9854–9866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]