Submitted:

02 February 2025

Posted:

03 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

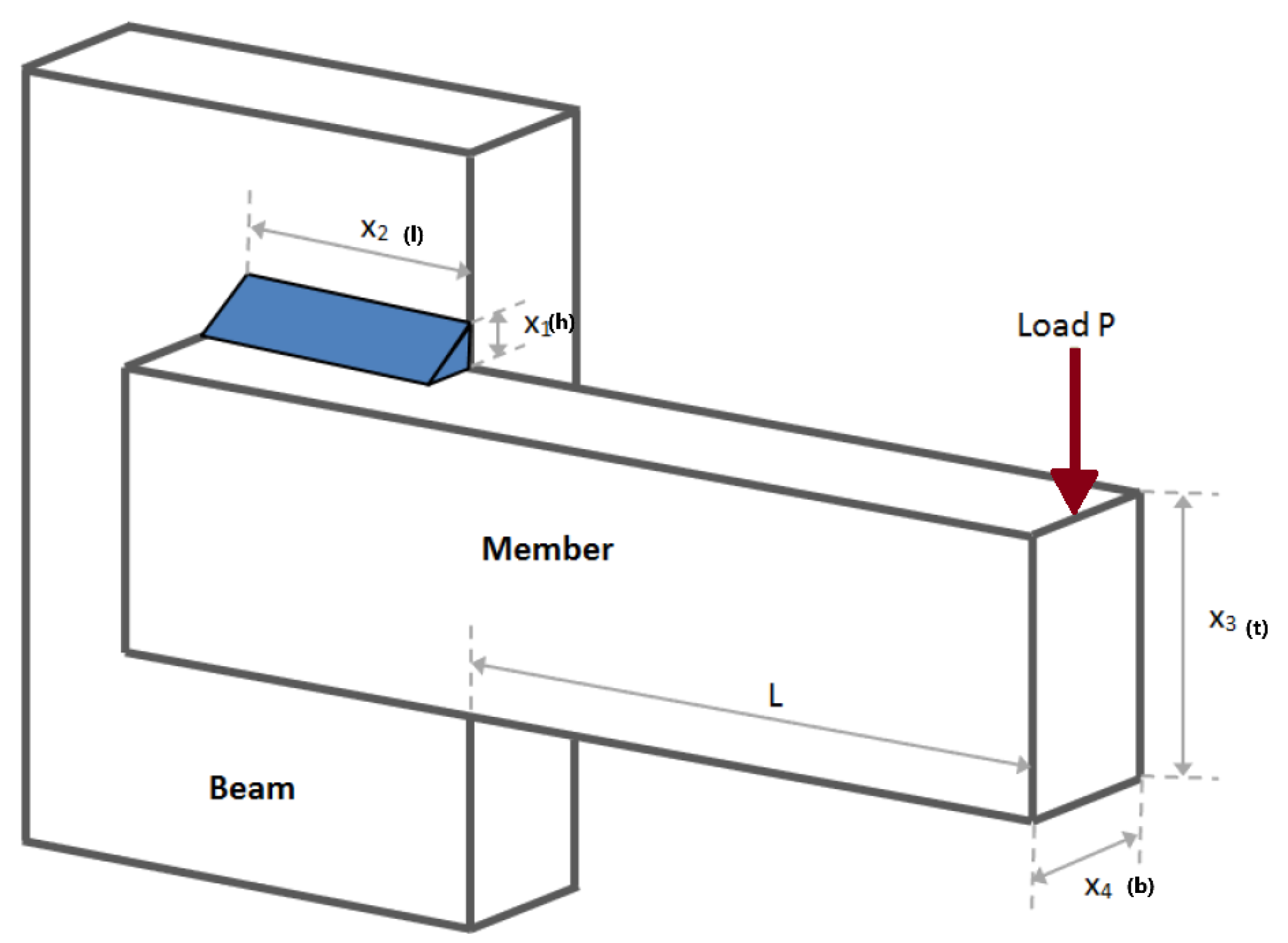

The welded beam design problem represents a real-world engineering challenge in structural optimization. The objective is to determine the optimal dimensions of a steel beam and weld length to minimize cost while satisfying constraints related to shear stress (τ), bending stress (σ), critical buckling load (Pc), end deflection (δ), and side constraints. The structural analysis of this problem involves four design variables: weld height (x1), support length (x2), beam thickness (x3), and beam width (x4), which are commonly denoted in structural engineering as h, l, t, b, respectively. The structural formulation of this problem leads to a nonlinear objective function, which is subject to five nonlinear and two linear inequality constraints. The optimal solution lies on the boundary of the feasible region, with a very small feasible-to-search-space ratio, making it a highly challenging problem for classical optimization algorithms. This paper explores the application of quantum computing to solve the welded beam optimization problem, utilizing the unique properties of quantum computers for constrained optimization in engineering problems. Specifically, we employ the D-Wave quantum computing system, which utilizes quantum annealing and is particularly well-suited for solving constrained optimization problems. The study presents a detailed formulation of the problem in a format compatible with the D-Wave system, ensuring efficient encoding of constraints and objective functions. Furthermore, we analyze the performance of quantum computing in solving this problem and compare the obtained results with classical optimization methods. The effectiveness of quantum computing is evaluated in terms of computational efficiency, accuracy, and its ability to navigate complex, constrained search spaces. This research highlights the potential of quantum algorithms in tackling real-world engineering optimization problems and discusses the challenges and limitations of current quantum hardware in solving practical industrial applications.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Problem spawanej belki jako problem optymalizacujny

Design Variables

- (1)

- : Height of the weld.

- (2)

- : Length of the weld.

- (3)

- : Thickness of the beam.

- (4)

- : Width of the beam.

Objective Function

Constraints

- (1)

- Shear Stress ():

- (2)

- Bending Stress ():

- (3)

- Deflection ():

- (4)

- Geometry ():

- (5)

- Buckling Load ():

- (6)

- Minimum Thickness ():

- (7)

- Cost Limit ():

Design Variables’ Ranges

Material Properties and Parameters

- Applied force: ,

- Beam length: ,

- Maximum deflection: ,

- Young’s modulus: ,

- Shear modulus: ,

- Maximum shear stress: ,

- Maximum bending stress: .

Stress and Deflection Formulas

- (1)

- Shear Stress ():where:

- (2)

- Bending Stress ():

- (3)

- Deflection ():

- (4)

- Buckling Load ():

Strength Constraints

Shear Stress Constraint

Normal Stress Constraint

Deflection Constraint

Weld Geometry Constraint

Buckling Load Constraint

Minimum Weld Height Constraint

Cost Constraint

3. Quadratic Unconstrained Binary Optimization (QUBO)

3.1. Basic Elements of QUBO

- (1)

-

Binary variablesEach component of the vector can only be 0 or 1.

- (2)

-

The matrix

- Diagonal elements capture the contribution of each variable (the “linear” part in the binary sense, since for ).

- Off-diagonal elements (for ) describe the interaction between variables and .

- (3)

-

Objective functionIt is given by . Typically, one aims to minimize this function, though maximizing is also possible by inverting the sign of the relevant terms in .

- (4)

-

Constraint penaltiesIn real-world applications, constraints (e.g., ) are introduced by adding penalty terms to the objective, for instance:where is sufficiently large so that violating the constraint becomes too costly.

3.2. Applications of QUBO

-

Combinatorial optimization problems. For example:

- Max-Cut: partitioning a graph’s vertices into two sets to maximize the sum of edges “cut” by that partition.

- SAT (Satisfiability): logical formulas can be mapped to QUBO by introducing penalties for unsatisfied clauses.

- Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP): minimizing the total route distance while visiting each city exactly once.

-

Business optimization.

- Knapsack Problem: choosing a subset of items under capacity constraints.

- Production planning and scheduling: allocating tasks to resources.

- Resource allocation: selecting investment projects with limited budgets.

-

Machine learning.

- Clustering: minimizing a chosen error function to group data points.

- Feature selection: choosing an optimal subset of features for classification tasks.

3.3. Solving QUBO

- Simulated Annealing, Genetic Algorithms, Tabu Search: metaheuristics that search the space of solutions.

- Hybrid methods combining exact search (e.g., integer programming) with heuristic approaches.

- Quantum Annealing: realized on machines like D-Wave, where QUBO is expressed as an equivalent Ising problem.

- Gate-based algorithms: e.g., QAOA (Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm), requiring additional implementation steps and an active area of research.

4. Formulating Welded Beam Design as QUBO

4.1. Objective Function

- Each design variable () is discretized into a finite range of values, represented as binary vectors.

- Each variable is described as:

4.2. Constraints

4.3. Constraints

4.4. QUBO Matrix

- are the linear weights for the binary variables,

- are the quadratic interaction coefficients between the variables.

5. Results

| Algorithm Name | Best Result | Result Source |

|---|---|---|

| WOA | 1.732 | (Mirjalili & Lewis, 2016) |

| PSO | 1.742 | (Mirjalili & Lewis, 2016) |

| GOOSE | 3.188 | arxiv2024 |

| GSA | 3.576 | (Mirjalili & Lewis, 2016) |

| Quantum Start 1 | 1.234 | – |

| Quantum Start 2 | 1.016 | – |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| x1 (Height of weld) | 0.3533 |

| x2 (Length of weld) | 6.0400 |

| x3 (Height of beam) | 2.0800 |

| x4 (Width of beam) | 2.0000 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| x1 (Height of weld) | 0.3533 |

| x2 (Length of weld) | 4.7200 |

| x3 (Height of beam) | 4.7200 |

| x4 (Width of beam) | 0.8600 |

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ewald, D.; Czerniak, J.M.; Paprzycki, M. A New OFNBee Method as an Example of Fuzzy Observance Applied for ABC Optimization. In Theory and Applications of Ordered Fuzzy Numbers; Prokopowicz, P., Czerniak, J., Mikolajewski, D., Apiecionek, L., Slzak, D., Eds.; Studies in Fuzziness and Soft Computing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 356. [Google Scholar]

- Czerniak, J.M.; Zarzycki, H.; Ewald, D. AAO as a new strategy in modeling and simulation of constructional problems optimization. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2017, 76, 22–33, ISSN 1569-190X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewald, D.; Czerniak, J.M.; Zarzycki, H. Approach to Solve a Criteria Problem of the ABC Algorithm Used to the WBDP Multicriteria Optimization. In Intelligent Systems’2014. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Angelov, P., et al., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D-Wave Documentation. Available online: https://docs.dwavesys.com/docs/latest/c_gs_2.html (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- What Is the Hamiltonian? Available online: https://support.dwavesys.com/hc/en-us/articles/360003684614-What-Is-the-Hamiltonian (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- D-Wave Hybrid Solver Documentation. Available online: https://docs.dwavesys.com/docs/latest/handbook_hybrid.html (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- Introduction to D-Wave Systems. Available online: https://docs.dwavesys.com/docs/latest/handbook_intro.html (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- Mirjalili, S.; Mirjalili, S.M.; Lewis, A. Grey Wolf Optimizer. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2014, 69, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, K.; Sundar, J.; N, U.B.R.; Chaudhuri, S. Reference Point Based Multi-Objective Optimization Using Evolutionary Algorithms. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Res. 2006, 2, 273–286. Available online: https://www.softcomputing.net/ijcir/vol2-issu3-paper4.pdf.

- Ray, T.; Liew, K.M. A Swarm Metaphor for Multiobjective Design Optimization. Eng. Optim. 2002, 34, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, R.K.; Rashid, T.A. GOOSE Algorithm: A Powerful Optimization Tool for Real-World Engineering Challenges and Beyond. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2307.10420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S. Dragonfly algorithm: a new meta-heuristic optimization technique for solving single-objective, discrete, and multi-objective problems. Neural Comput. Appl. 2016, 27, 1053–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochenberger, G.A.; Hao, J.K.; Glover, F.; Lewis, M.; Lü, Z.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y. The unconstrained binary quadratic programming problem: a survey. J. Comb. Optim. 2014, 28, 58–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, A. Ising formulations of many NP problems. Front. Phys. 2014, 2, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, F.; Kochenberger, G.A.; Du, Y. Quantum-Inspired Evolutionary Algorithms; Studies in Computational Intelligence; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).