1. Introduction

According to the World Health Organization, respiratory diseases are among the top global health threats, ranking as the second (tuberculosis) and third (lower respiratory tract infections) leading causes of death worldwide [

1]. More than one billion people suffer from acute or chronic respiratory conditions, leading to a substantial burden on healthcare systems and significantly affecting patients’ quality of life and life expectancy.

Among the various indicators of respiratory health, respiratory sounds are particularly important, as they reflect underlying pulmonary conditions and provide noninvasive, real-time insight into the state of the lungs. These sounds play a critical role in the early detection and auxiliary diagnosis of diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, and pneumonia. Traditionally, auscultation has been the cornerstone of pulmonary assessment, where stethoscopes are used to listen to lung sounds and evaluate respiratory conditions [

2]. However, this approach is inherently restricted to clinicians’ experience, perceptual acuity, and subjective interpretation [

3]. As a result, diagnostic accuracy can vary significantly between practitioners. Given these limitations, there is a growing demand for intelligent diagnosis that is not only automated, accurate, and efficient but also user-friendly and capable of providing consistent, expert-level assessments across diverse settings.

Recent developments in electronic stethoscope technology have enabled the recording of high-quality lung sounds, creating new opportunities for automated analysis of pulmonary auscultation. The International Conference on Biomedical and Health Informatics (ICBHI) launched a scientific challenge in 2017 using the ICBHI2017 dataset [

4]. This dataset includes respiratory cycles manually annotated by clinical experts, with labels specifying the presence of crackles, wheezes, their combinations, or normal breath sounds. Unlike crowdsourced datasets collected online, the ICBHI2017 dataset was curated in clinical environments under professional supervision, ensuring greater annotation reliability and clinical relevance [

5]. Since its release, the ICBHI2017 dataset has become a benchmark for evaluating respiratory sound classification algorithms.

Numerous studies leveraging convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have been conducted to detect and classify abnormal respiratory sounds, achieving promising results. These efforts underscore the importance of identifying acoustic anomalies, particularly crackles and wheezes, for the accurate diagnosis of pulmonary diseases [

6]. Specifically, crackles are brief, discontinuous, non-musical sounds typically associated with conditions such as COPD and pneumonia [

7], while wheezes are continuous, high-pitched, musical sounds often linked to airway obstruction, commonly observed in patients with asthma and COPD [

6,

7,

8]. Automated detection of these sounds holds great potential for early screening, remote monitoring, and decision support in clinical practice.

The development of efficient and intelligent methods for respiratory sound classification (RSC) has become a critical pathway for enhancing early screening and auxiliary diagnosis of pulmonary diseases. Recently, deep learning has emerged as the predominant approach for modeling and classifying respiratory sounds, with commonly used architectures including CNNs, recurrent neural networks (RNNs), long short-term memory (LSTM) networks, and Transformer-based models [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. Notably, Audio Spectrogram Transformer (AST) has shown remarkable effectiveness and adaptability in capturing temporal and spectral dependencies [

9], yielding superior RSC performance. Further, techniques, such as transfer learning, feature fusion, and attention mechanisms, have contributed to performance improvements by leveraging prior knowledge, combining complementary representations, and focusing on salient signal components [

5].

Despite these advancements, current research still faces significant challenges, particularly in audio feature fusion strategies. Many existing methods rely on simple concatenation of handcrafted or learned features without adequately modeling the semantic complementarity or interaction dynamics between different feature inputs. Consequently, these models may overlook sample-specific discriminative cues and fail to extract the most informative features. Moreover, such static fusion schemes lack the ability to dynamically adjust feature importance based on input context, which limits their effectiveness in capturing diverse acoustic patterns and ultimately constrains real-world RSC performance.

To address the challenges, we propose an Attention-based Dual-stream Feature Fusion Network (ADFF-Net) enhanced with skip connections. First, acoustic representations of Mel-filter bank (Mel-FBank), Mel-spectrogram, and Mel-frequency cepstral coefficients (MFCCs), are extracted [

17]. Through experiments, Mel-FBank and Mel-spectrogram are found to be particularly discriminative for representing respiratory sound characteristics. To fully exploit the complementary information between the dual-stream feature inputs, an attention mechanism is employed for adaptive weighting of features. In parallel, skip connections are incorporated to retain the original information and to prevent the loss of important details during feature fusion. The final fused representation, enriched with both contextual emphasis and original signal integrity, is fed into the backbone AST to perform the classification of respiratory sound events. The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows,

An ADFF module is designed which uses an attention mechanism for dual-stream feature fusion and employs skip connection for detail preservation.

An ADFF-Net framework is proposed that utilizes the ADFF module for deep feature representation and the pre-trained AST for final sound classification.

Extensive experimental results on the ICBHI2017 database verifies the effectiveness of the proposed ADFF-Net framework for classifying respiratory sounds.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews the RSC advances in time–frequency representations, AST-based approaches, and multi-stream feature fusion strategies.

Section 3 introduces the ICBHI2017 database, the computation of the three acoustic features, and the proposed ADFF-Net framework.

Section 4 reports the experimental results, including the evaluation of feature representation capacity, comparisons of different fusion strategies, and benchmarking against recent state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods on the ICBHI2017 database.

Section 5 provides an in-depth analysis of the findings and discusses potential future research directions. Finally,

Section 6 summarizes the study and highlights the potential of ADFF-Net for advancing biomedical signal analysis.

2. Related Work

This section presents the related work, ranging from two-dimensional (d) representation of respiratory sounds, application of AST in the RSC task, and the fusion techniques for multi-stream feature inputs.

2.1. Respiratory Sound Representation

Transforming raw acoustic signals into time–frequency quantification is preferred for respiratory sound feature representation. This transformation allows the extraction of both temporal dynamics and spectral characteristics, while also enabling the adaptation of off-the-shelf deep models originally designed for image inputs.

Mel-FBank features, Mel-spectrograms, and MFCCs are preferred

representations, owing to their strong biological relevance in capturing acoustic patterns [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Bae et al. [

16] employ Mel-FBank features and incorporate data augmentation and contrastive learning. Bacanin et al. [

18] utilize Mel-spectrograms and fine-tune the embedding parameters through metaheuristic learning. Zhu et al. [

19] adopt a VGGish-BiLSTM-Attention model by using Mel-spectrogram inputs. Wall et al. [

20] utilize MFCCs in an attention-based architecture for the abnormality diagnosis. Latifi et al. [

21] introduce maximum entropy Mel-FBank features by combining MFCCs and Gabor Filter Bank features. Li et al. [

22] address class imbalance by coupling MFCCs with adaptive synthetic sampling.

2.2. AST-Based RSC Applications

Transformer-based models, particularly AST [

9], have established itself as the SOTA approach for non-stationary sound analysis. Its success is largely attributable to the capacity of modeling long-range temporal dependencies and global acoustic context through multi-head self-attention mechanisms. Wu et al. [

14] enhance the robustness of AST to background noise by designing a dual-input variant that simultaneously processes spectrograms and log Mel-spectrograms. Ariyanti et al. [

15] introduce Audio Spectrogram Vision Transformer, which segments Mel-spectrograms into overlapping patches with positional encoding and applies multi-layer self-attention to capture global acoustic patterns. Bae et al. [

16] show that integrating AST with data augmentation and contrastive learning achieves superior RSC performance. Neto et al. [

23] extract deep features from MFCCs, Mel-spectrograms, and Constant-Q Transform (CQT) representation for refinement of a Vision Transformer. Kim et al. [

24] employ an audio diffusion model to generate synthetic data, which is combined with AST to address the problem of limited training samples. Stethoscope-guided contrastive learning is proposed [

25] that mitigates domain shifts caused by differences in recording devices, thereby improving the real-world applicability of AST in respiratory sound classification. Xiao et al. [

26] leverages multi-scale convolutions for spectral details and feature adaptation into the AST backbone.

2.3. Multi-Stream Feature Fusion Strategies

Single-source features are widely used for their simplicity, even though the representation capacity is limited by uni-dimensional information coverage [

5]. In contrast, fusion of multi-stream inputs combines complementary acoustic cues, such as spectral structure, temporal dynamics, and tonal features. A more holistic capture of diverse pathological patterns has been shown to significantly improve model discrimination.

Dual-stream feature fusion enhances acoustic separability by combining complementary representations. Chu et al. [

27] fuse Mel-spectrograms and CQT spectrograms into hybrid spectrograms, processed by frequency masking and time grouping, and extracted features using a grouped time-frequency attention network, achieving 71% accuracy on four-class ICBHI2017 classification. Xu et al. [

12] combine MFCCs and Mel-spectrograms as inputs to a residual-attention-enhanced parallel encoder, achieving 80.0% accuracy for binary and 56.76% for four-class RSC tasks.

Multi-stream feature fusion holds the potential to improve the performance by leveraging multi-dimensional information. Neto et al. [

23] utilize Mel-spectrograms, MFCCs, and CQT to overcome the limitations of frequency resolution. Borwankar et al. [

28] integrate Mel-spectrograms, MFCCs, and chroma energy normalized statistics to cover spectral, auditory, and pitch features jointly. Roy et al. [

29] combine Mel-spectrograms, CQT, and MFCCs to form comprehensive time-frequency representations for COPD detection [

30]. Wanasinghe et al. [

31] organize MFCCs, Mel-spectrograms, and chromagrams in

representation, and a lightweight network is designed to learn spectral, auditory, and pitch features for balancing model compactness and performance in binary and multi-class prediction. Xu et al. [

32] integrate acoustic features such as MFCCs and zero-crossing rate with deeply learned features, and a Bi-LSTM is employed to model temporal dependencies that achieves a classification accuracy of 96.33% in cough sound detection.

Fusion of deep learning features are also popular for comprehensive representation and performance improvement. Kim et al. [

24] design an audio diffusion model to generate realistic respiratory sound samples and employ adversarial fine-tuning to mitigate distributional discrepancies between synthetic and real data. Further, they incorporated cross-domain adaptation to transfer learned knowledge from the source to target domain by treating different types of stethoscope as distinct domains in a supervised contrastive learning manner [

25]. Pham et al. [

33] implement an ensemble framework by integrating multiple transferred models. Three levels of feature fusion, including early, middle, and late, are explored, achieving a maximum ICBHI2017 score of 57.3%. Shehab et al. [

34] extract multi-source features from different pre-trained CNNs and obtain an 8064-

d vector. By employing early fusion through direct concatenation, they achieved an accuracy of 96.03% in classifying eight categories of pulmonary diseases.

3. Materials and Methods

This section begins with the ICBHI2017 database, followed by the description of computing features for respiratory sound representation. The proposed ADFF-Net framework is then detailed from the integration of attention mechanism and skip connections (i.e., the ADFF module) to the use of AST for sound classification. After that, the experimental design is described, covering a unified pre-processing pipeline for respiratory cycle segments, evaluation of different feature representations, and comparison of various fusion strategies. Finally, the evaluation metrics used to assess model performance is outlined.

3.1. The ICBHI2017 database

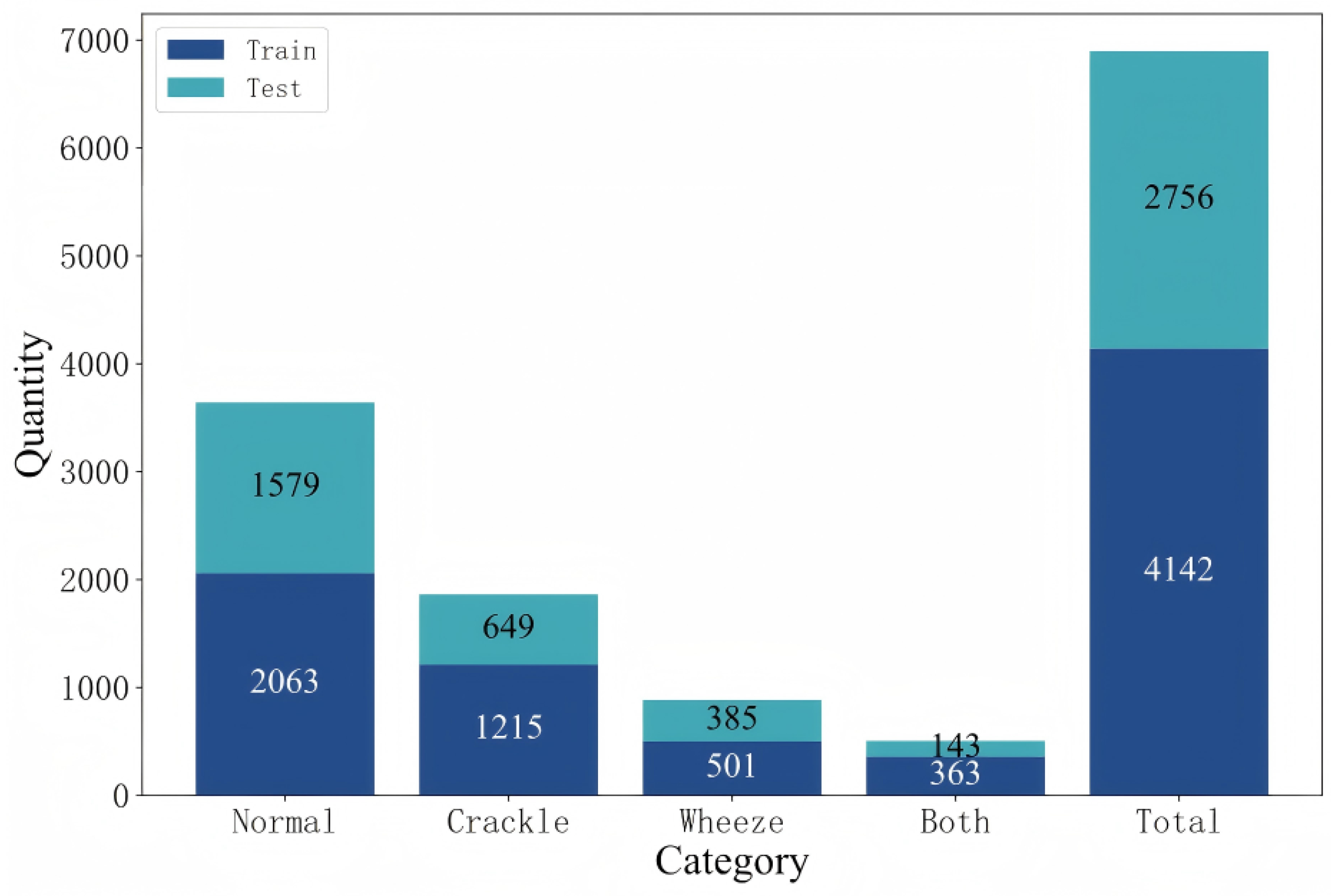

Figure 1 illustrates the category-wise distribution of data samples across the officially defined training and testing sets in the ICBHI2017 database [

4]. The database consists of 6898 respiratory cycles, totally ≈ 5.5 hours of recordings. To facilitate fair model evaluation and comparison, the dataset is officially partitioned into a training set (60% of the samples) and a testing set. Notably, respiratory cycles from the same patient are assigned exclusively to either the training or the test set, ensuring that there is no patient case overlap between the two sets to prevent data leakage. This standardized split supports reproducibility and benchmarking in respiratory sound classification [

5].

As illustrated in

Figure 1, each respiratory cycle in the database is annotated as one of the four categories, “Normal”, “Crackle”, “Wheeze”, or “Both” (i.e., the presence of both crackle and wheeze). In total, the training set includes 2063 normal cycles, 1215 cycles with crackles, 501 with wheezes, and 363 with both crackles and wheezes, while the testing set contains 1579 normal cycles, 649 with crackles, 385 with wheezes, and 143 with both adventitious sounds.

3.2. Feature Representation of Respiratory Sounds

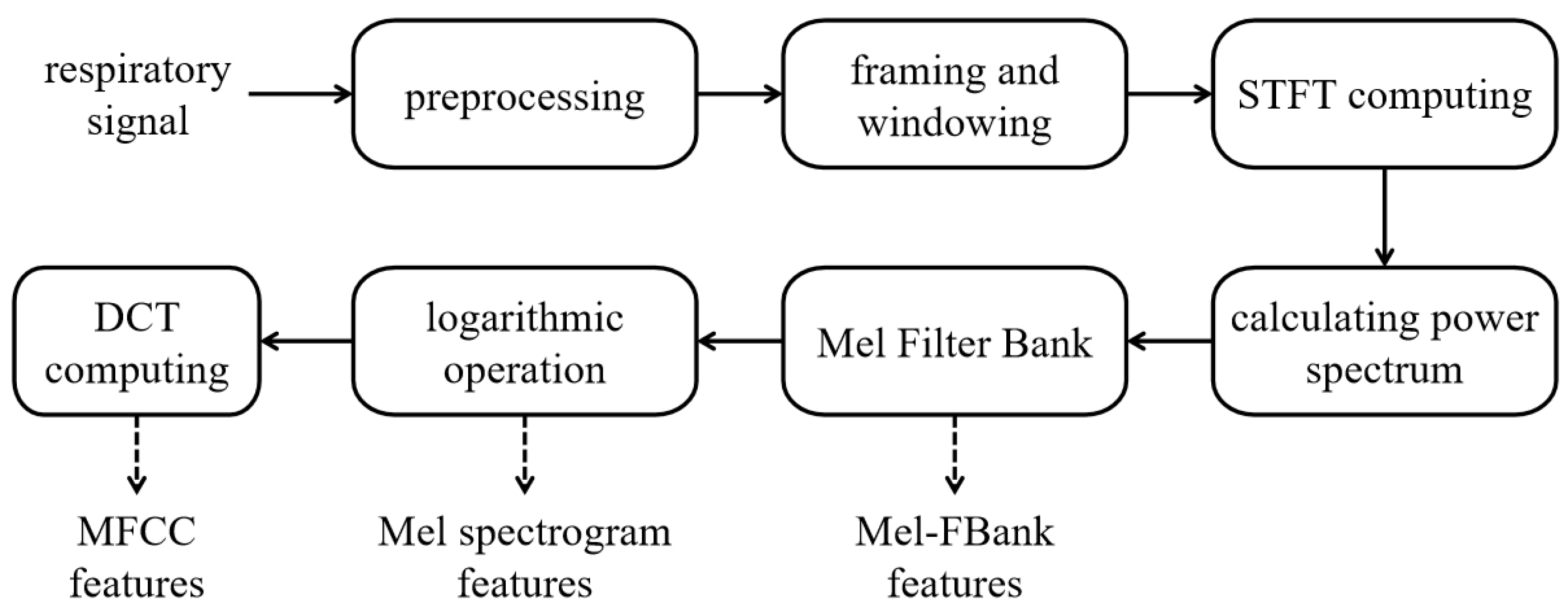

Mel-FBank, Mel-Spectrogram and MFCC features are computed for respiratory sound representation [

17].

Figure 2 shows the procedure, including signal pre-processing, framing and windowing, short-time Fourier transform (STFT) computation, and power spectrum calculation. Mel-FBank features are derived by applying a bank of Mel-scale filters to the power spectrum, Mel-Spectrogram features are obtained by taking the logarithm of the Mel-FBank energies, and MFCC features are generated by applying the Discrete Cosine Transform (DCT) to the log-Mel spectrum, providing a compact representation of the spectral envelope.

To enhance the readability and clarity of the feature extraction process,

Table 1 provides a summary of the symbols and parameter definitions used in the computing of Mel-FBank, Mel-Spectrogram, and MFCC features. It facilitates a clear understanding of the underlying mathematical operations and processing steps.

3.2.1. Signal Preprocessing

After loading an original audio signal

, pre-emphasis is applied. It employs a high-pass filter to enhance the high-frequency components of the input signal. Eq.

1 shows the operation of the pre-emphasis, in which

denotes the pre-emphasis coefficient and its value is defined as 0.97 as suggested [

36].

3.2.2. Framing and Windowing

Framing refers to segmenting a signal into a series of short frame S, each containing N samples, and adjacent frames typically overlap to a certain extent. The frame length and shift determine the size of each frame and the degree of overlap between frames.

Windowing is applied by multiplying each frame with a window function

, such as Hamming window, to reduce spectral leakage. The windowed signal of the

m-th frame is calculated as Eq.

2 in which

is the pre-emphasized signal.

3.2.3. STFT Computing

Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) is performed on each frame for obtaining its frequency spectrum. Eq.

3 defines the operation, in which

denotes the windowed time-domain sample at index

n in the

m-th frame, and

represents the complex value of the

k-th frequency component in the

m-th frame.

During feature extraction, STFT was applied using a window size of 25 ms and a frame shift of 10 ms, with Hanning window employed to minimize spectral leakage.

3.2.4. Calculating Power Spectrum

The power spectrum for each frame is calculated by squaring the magnitude of the spectrum. Eq.

4 shows the formulation of the power spectrum,

.

3.2.5. Summarizing Mel Filters for Mel-FBank Features

A set of Mel filters

is designed to transform the power spectrum from the linear frequency scale to the Mel scale. These filters are typically triangular, with center frequencies evenly spaced on the Mel scale. The output of each filter is the weighted sum of the input power spectrum within that filter. Eq.

5 shows the operation of the output of each filter, in which

represents the frequency response of the

i-th Mel filter.

In this study, raw audio waveforms are transformed into a sequence of 128-d Mel-FBank features. The resulting spectrograms were further standardized with a mean of -4.27 and a standard deviation of 4.57 for normalization as suggested.

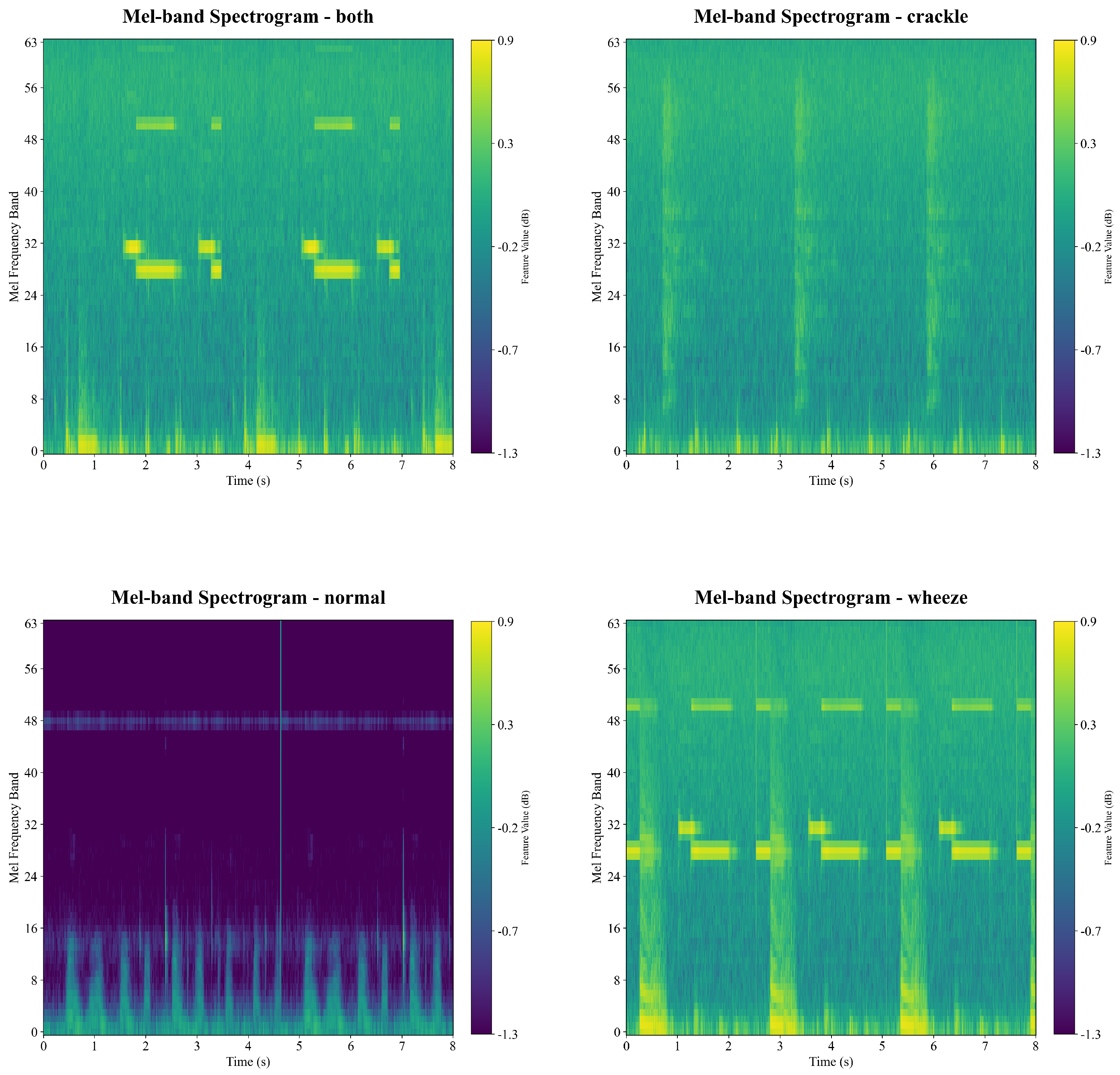

Figure 3 demonstrates representative examples of Mel-FBank features for the four categories of respiratory sounds. In each spectrogram, the horizontal axis represents time, and the vertical axis shows the filter bank index. The color bar indicates the amplitude intensity in decibels (dB) for capturing the temporal and spectral variations of the signal through color mapping.

It is observed in

Figure 3 that the normal signal is quite different from the other three types of sounds due to the lowest signal amplitude intensity, while the exemplar signals of the Wheeze and the Both category are visually hard to be differentiated from each other, because of perceived similar patterns and strength.

3.2.6. Logarithmic Computing for Mel-Spectrogram Features

The Mel-Spectrogram is a 2-

d time-frequency representation obtained by taking the logarithm of the Mel-FBank outputs and arranging them sequentially along the time axis. It provides an intuitive visualization of the time-varying energy distribution of the signal in the Mel frequency domain. Eq.

6 shows the operation of Mel-Spectrogram. The log Mel-spectrograms of each frame are subsequently arranged sequentially along the time axis to form a 2-

d Mel-spectrogram, with the horizontal axis representing time (frame sequence) and the vertical axis representing Mel frequency.

In this study, the Librosa [

35] is used to extract Mel-Spectrogram features from the raw audio signals that generates 64-

d Mel filter bank feature maps. The parameters are set as the frame length of 1024 samples (≈ 64 ms), frame shift of 512 samples (≈ 32 ms), Hanning window function, frequency range from 50 to 2000 Hz, and FFT size of 1024 points as suggested [

36]. The extracted spectrograms are log-power scaled and normalized to the [0,1] range, then converted into image format for model input.

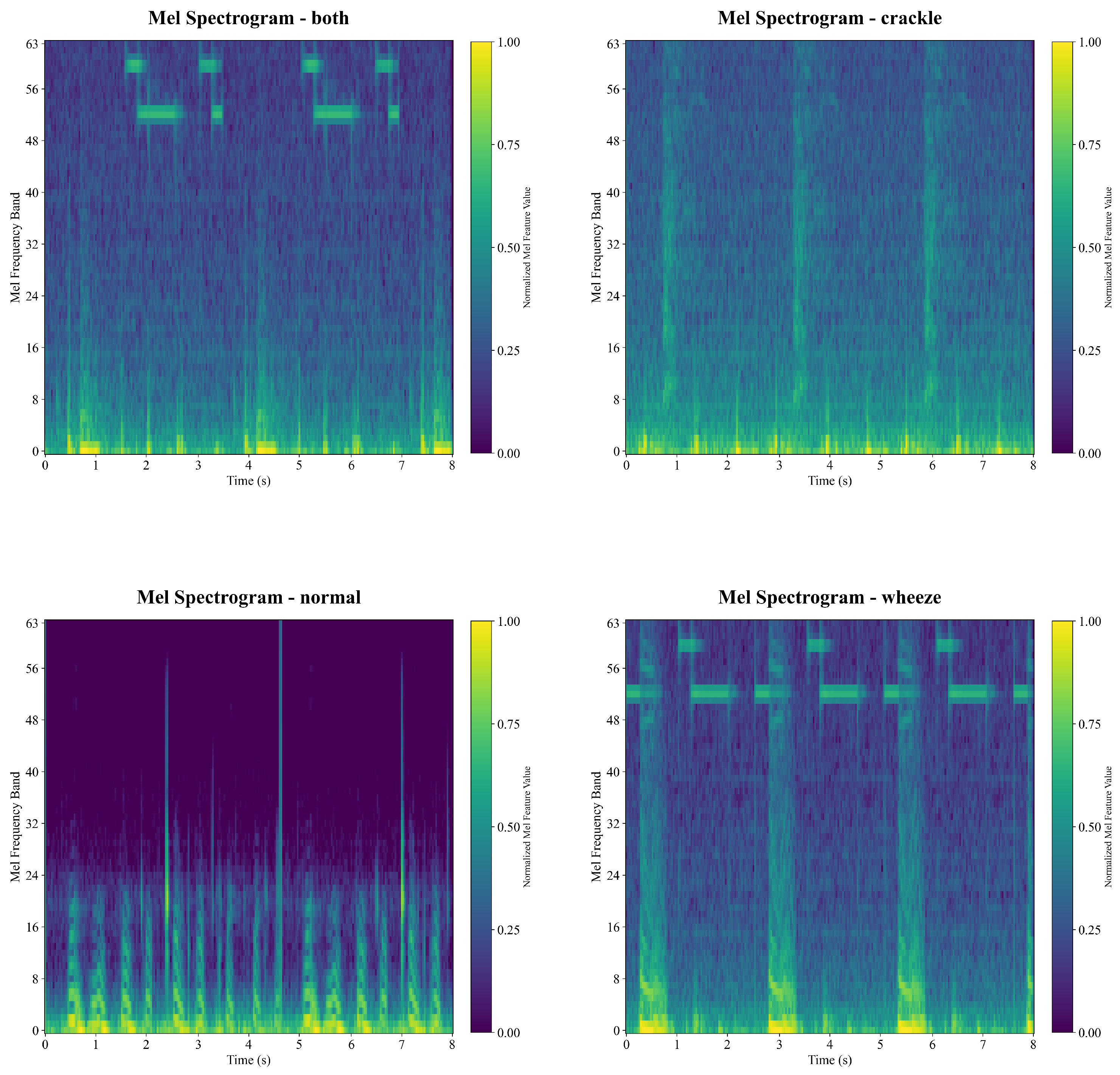

Figure 4 illustrates example Mel-Spectrogram features of different categories. The horizontal axis represents the time, and the vertical axis denotes the Mel frequency index. The color bar intuitively reflects the intensity of frequency components over time, with color saturation corresponding to signal power in dBs.

It is found in

Figure 4 that the normal signal is quite different from the other three types of sounds due to the lowest signal amplitude intensity, while the exemplar signals of the Wheeze and the Both category are visually similar because of similar pattens and strength in the feature map.

3.2.7. DCT Computing for MFCC Features

MFCCs are are obtained by applying DCT to the log Mel frequency spectrum, and a set of cepstral coefficients are generated. Typically, only the first

K coefficients are retained as the final output of a MFCC feature vector, reducing feature dimensionality while preserving the essential characteristics of the input signal. Eq.

7 shows the operation of the MFCC features, in which

denotes the

q-th cepstral coefficient of the

m-th frame,

L is the number of Mel filters, and

K is the number of retained cepstral coefficients. In this study, the MFCC function in the Librosa [

35] is employed to extract 13-

d MFCC features of the input audio signals.

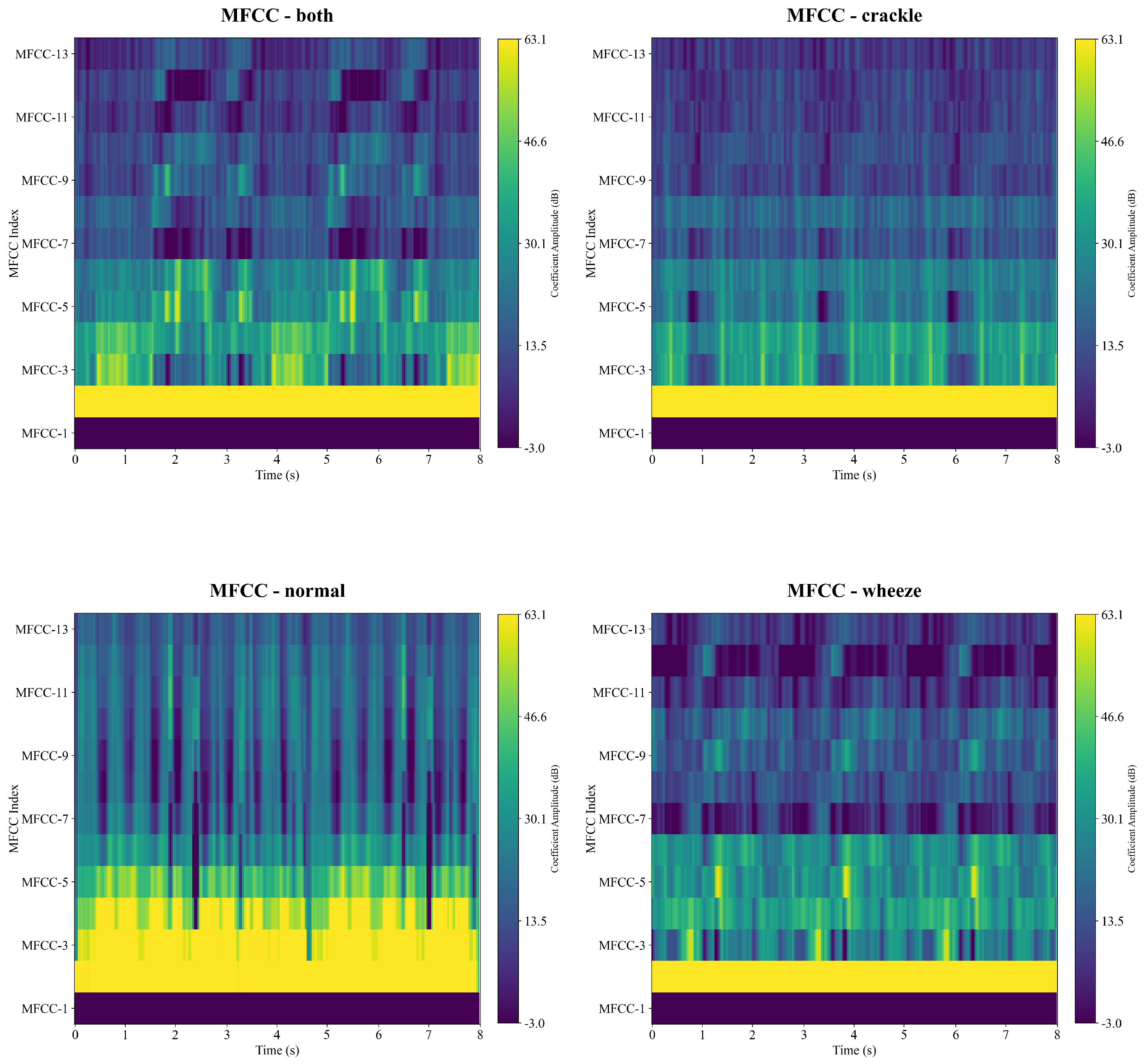

Figure 5 shows MFCC features of the categories of respiratory sounds. The horizontal axis represents time, and the vertical axis shows the 13 coefficients, each capturing the energy variation of the signal within a specific frequency band. The color map provides an intuitive visualization of the temporal dynamics of each coefficient, where the intensity of the color indicates the magnitude of the coefficient values. This representation effectively reveals the time–frequency structure of the audio signal.

As illustrated in

Figure 5, the normal respiratory sound shows highest coefficient intensity, particularly in the lower-order MFCC dimensions from MFCC-1 to MFCC-5, while the other categories of sounds demonstrate highest coefficient values in the MFCC-1 and MFCC-2. Notably, the sounds of Both, Crackle and Wheeze show similar patterns which are hard to differentiate from each other.

3.3. The Proposed ADFF-Net Framework

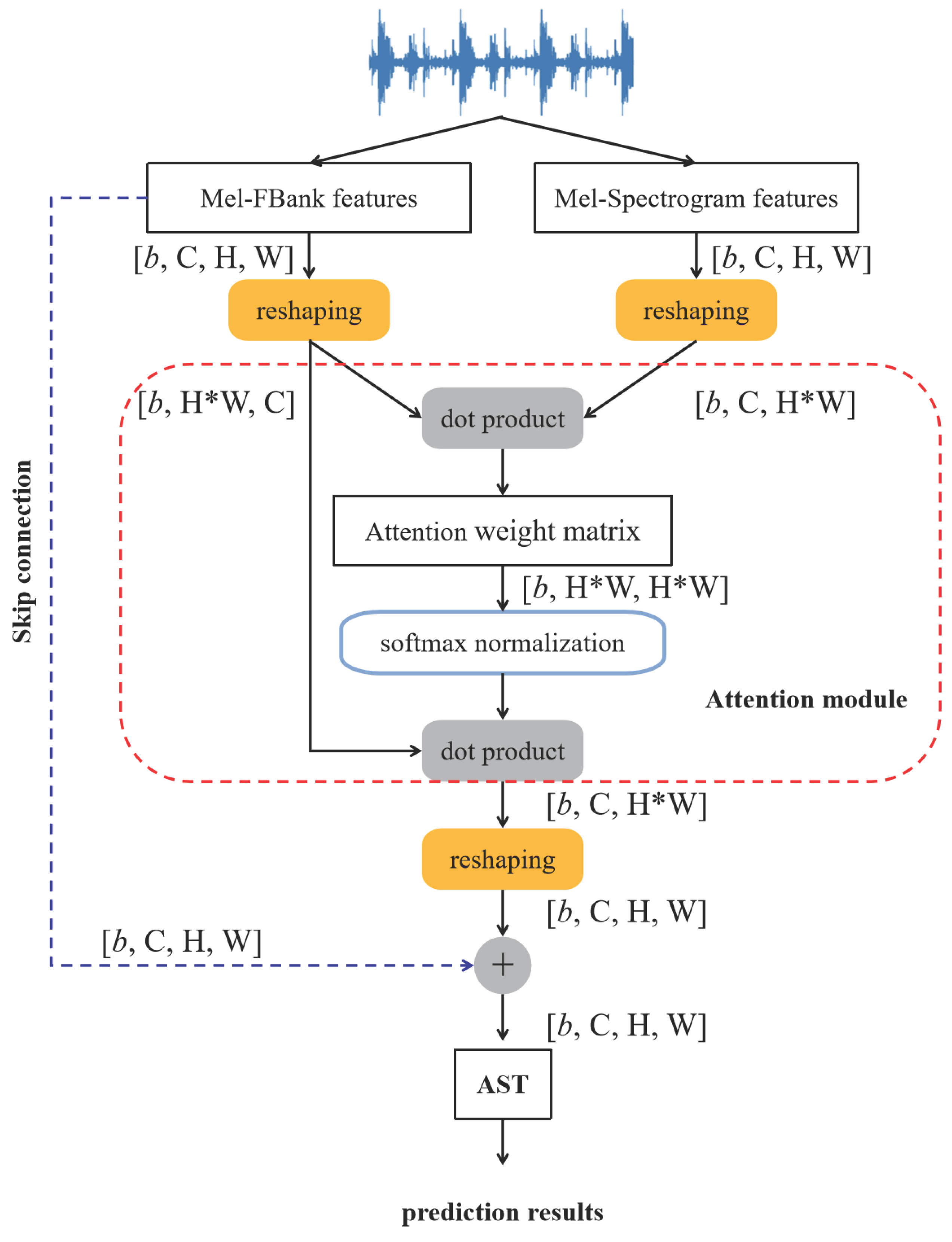

The proposed framework integrates both the ADFF module and the AST, as illustrated in

Figure 6. The ADFF module is designed to fuse dual-representative features effectively for enhancing the expressiveness of the input data, and the AST is responsible for the final classification of respiratory signals. In the example shown in

Figure 6, Mel-FBank features and Mel-Spectrogram features are used to show the processing workflow, and the matrix structures are detailed at each step in which

b,

C,

H and

W correspond to the batch size, the number of input channels, the input height and width.

It is important to noted that, the novelty of the framework lies primarily in the ADFF module, which introduces an attention mechanism to weight and integrate complementary features. Additionally, a skip connection structure is used to preserve low-level feature information and improve gradient flow during model training. Together, these designs enhance the capacity to capture both global and local patterns in respiratory sounds, ultimately boosting classification performance.

3.3.1. Attention Mechanism

Attention was introduced in machine translation, and has since become a fundamental component in deep learning architectures [

10]. It assigns learnable weights to different parts of the input sequence and enables the model to dynamically focus on regions most relevant to the current task. This enhances the model’s ability to capture both local and global contextual information and is particularly valuable for complex and sequential data analysis. A typical attention mechanism consists of three key steps. First, attention scores are computed by measuring the similarity between query (

Q) and key (

K) vectors. Second, these scores are normalized into a probability distribution using the Softmax function, yielding attention weights. Finally, a weighted sum of the value (

V) vectors is computed using the attention weights, producing context-aware representation vectors. This process allows the network to selectively emphasize informative parts of the input while suppressing less relevant components. In Eq.

8, the dimensionality,

d, of the

Q,

K and

V performs as the scaling factor, ensuring the output of the self-attention mechanism that maintains a distribution consistent with the input, thereby enhancing the model’s generalization capability.

3.3.2. The ADFF Module

The ADFF module combines an attention mechanism with skip connection for dynamic representation of multi-source features. The attention mechanism allows adaptive focus on critical correlations between different features for enhancing feature relevance and interaction. Meanwhile, the skip connection preserves low-level feature information that helps to mitigate degradation during feature propagation and enriches the overall multi-level semantic representation.

As shown in

Figure 6, different feature types, such as Mel-FBank and Mel-Spectrogram features, are extracted, each with a shape of

(here,

). To facilitate the computation of attention weights, the Mel-FBank features are reshaped to

, and the Mel-Spectrogram features are reshaped to

. Attention weights are then computed as the similarity between the two feature sets using the

torch.bmm function, resulting in an attention weight matrix sized

where each element quantifies the correlation between pixels across the feature types. After that, the attention weights are normalized to ensure numerical stability by using the

nn.Softmax function along the second dimension, producing a valid probability distribution. Next, the attention weights are used to perform as a weighted summation of the features. The normalized attention matrix is multiplied with the reshaped Mel-FBank features, producing a fused feature tensor of shape

that enhances the discriminative capability. At last, the fused tensor is reshaped back to its original dimensions

to maintain compatibility with the subsequent layers of the network.

3.3.3. Audio Spectrogram Transformer

AST adopts Transformer architecture to overcome the limitations of local receptive fields in CNNs and the sequential inefficiency of RNNs [

9]. It leverages cross-modal transfer learning by adapting Vision Transformer [

37] which is pre-trained on the ImageNet dataset [

38] to the audio domain by fine-tuning on the AudioSet database [

39]. The Transformer architecture based on self-attention allows for parallel processing of sequential data. It generally consists of an input module, an encoder, a decoder, and an output module. Notably, the input module includes an embedding layer and a positional encoding (PE) mechanism. The embedding layer converts input tokens (e.g., spectrogram patches) into dense vector representations. To address the lack inherent awareness of token order, PEs are added to the token embeddings to preserve sequence information. These PEs have the same dimensionality as the token embeddings and can either be learned during training or computed using a fixed formula (e.g., sinusoidal functions). By incorporating positional information, the model can better capture the sequential structure of the input data.

3.4. Experiment Design

A unified respiratory signal pre-processing pipeline is designed for standardizing respiratory cycle segments for subsequent analysis. Meanwhile, different feature fusion strategies are designed and compared. In addition, algorithm implementation and parameter settings are provided.

3.4.1. Unified Respiratory Signal Pre-Processing

To enhance model robustness, a unified pre-processing pipeline is designed for the respiratory cycle segments [

5]. All segments are first resampled to 16 kHz. Given the substantial variability in segment durations, each recording is then normalized to a fixed length of 8 seconds (≈ 798 frames) using truncation or padding. Furthermore, to mitigate boundary artifacts caused by abrupt truncation or repetition, linear fade-in and fade-out techniques are applied at the beginning and end of each segment, which help suppress high-frequency transients and reduce spectral discontinuities. This unified pre-processing pipeline ensures that all segments are consistent in length, facilitating fair and reproducible model training, evaluation, and benchmarking in respiratory sound classification.

3.4.2. Analysis of Feature Representation Performance

Three features, including Mel-FBank, Mel-Spectrogram, and MFCCs, are investigated for representation performance in respiratory signal classification. The goal is to assess the representational capacity and complementarity of each features, thereby informing the design of subsequent feature fusion strategy. Both individual features and combinations of two different feature inputs are evaluated to assess their effectiveness in capturing discriminative patterns from respiratory sounds, highlighting their individual and complementary contributions to model performance.

3.4.3. Comparison of Different Feature Fusion Strategies

Several feature fusion strategies are compared, including (1) two concatenation-based fusion methods, (2) attention mechanism–based fusion, and (3) the proposed ADFF module. To ensure fair comparison, all experiments are conducted using the same pre-trained AST as the backbone model.

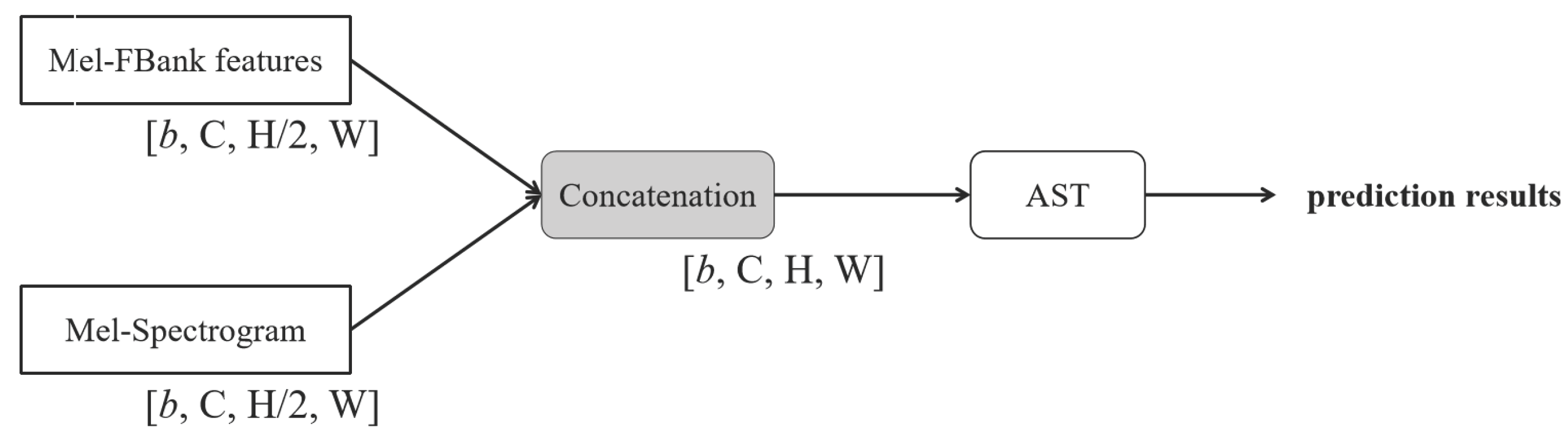

The first concatenation-based fusion approach, referred to as Concat-AST shown in

Figure 7, involves concatenating two feature inputs prior to classification using the AST model. To ensure dimensional compatibility with AST input requirements, the concatenated features are compressed along the height (

H) dimension before being fed into the model.

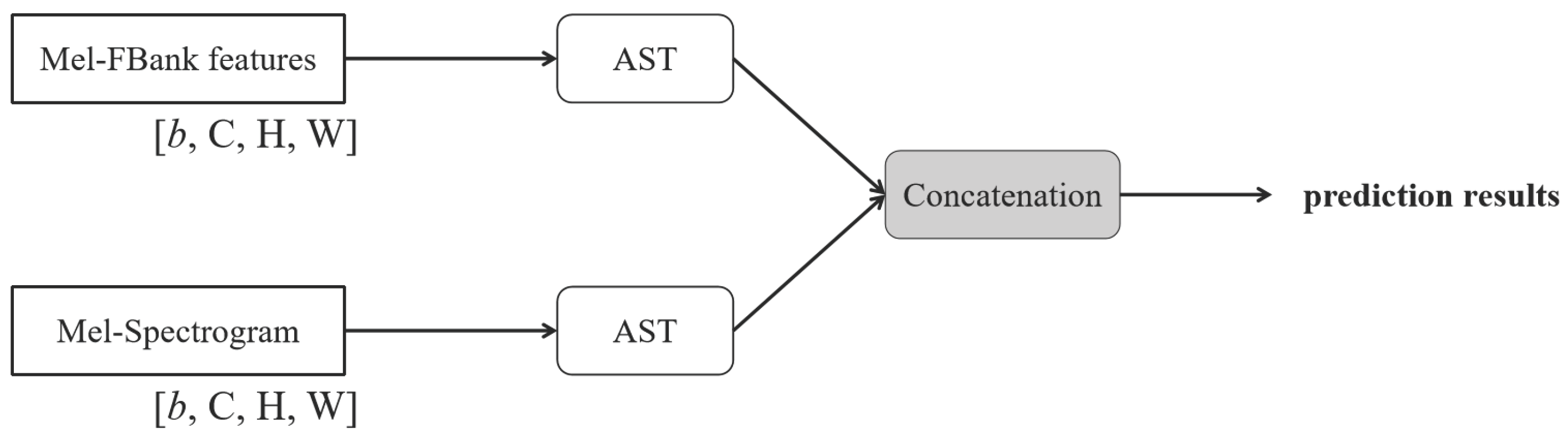

The second concatenation-based fusion approach, referred to as AST-Concat shown in

Figure 8, processes each input feature independently through the pre-trained AST model. The output representations from each stream are then concatenated and passed through a linear classification layer to perform respiratory signal prediction.

Additionally, an attention mechanism–based fusion approach, implemented using the proposed ADFF module without the skip connection as shown in

Figure 6, is introduced to evaluate the individual contribution of the skip connection. This setup is intended to verify the importance and effectiveness of skip connections in enhancing feature representation.

3.4.4. Parameter Settings

In the experiments, model training was performed on a Linux system (Ubuntu 20.04) equipped with an NVIDIA GTX 2080 Ti GPU. The network was implemented with PyTorch, where pre-processed respiratory sound data were fed into the model for feature extraction and classification. The learning rate was set to 0.00005, with a training batch size of 4 and a total of 50 training epochs. The classification task used the standard cross-entropy loss function and the Adam optimizer. Hyper-parameters were primarily selected based on best practices reported in related literature. The configuration was used to evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed network and feature fusion strategy.

3.5. Evaluation Metrics

In this four-class prediction task, , , , and correspond to the number of correctly predicted samples in the “normal,” “crackle,” “wheeze,” and “both” categories, and , , , and to the number of samples for the classes.

Evaluation metrics used in this study include Specificity (SPE), Sensitivity (SEN), and the ICBHI score (HS), as established in the ICBHI 2017 Challenge [

4]. The metric SPE measures the capacity of a model to correctly identify healthy samples, and Eq.

9 shows how to compute the metric,

The metric SEN measures model capacity to correctly identify pathological samples, which can be computed as shown in Eq.

10,

The metric HS concerns both specificity and sensitivity to evaluate the overall performance as shown in Eq.

11,

The metrics are widely used for performance evaluation that can be computed in a similar way for binary, ternary, and multi-class classification tasks [

40,

41].

4. Results

This section presents the evaluation results on feature representation capacity, comparisons of various feature fusion strategies, and a summary of SOTA results on the ICBHI2017 database. For ease of comparison, the highest and lowest values of each metric are highlighted in red and blue, respectively.

4.1. Evaluation of Feature Representation Capacity

Feature effectiveness is evaluated through the four-class RSC task. When a single feature is used, classification is performed using the AST model. For combinations of two feature types, the proposed ADFF-Net framework (

Figure 6) is applied. Experimental results are presented in

Table 2.

As shown in

Table 2, when using a single feature, MFCCs yield the highest SPE but the lowest SEN and HS. Notably, the SEN value is 9.43%, significantly lower than that of the other two features. In contrast, Mel-FBank features achieve the highest SEN and HS values but have the lowest SPE. When combining two types of features, the combination of Mel-FBank and Mel-Spectrogram features produces the highest values across SPE, SEN, and HS, suggesting this fusion provides the most discriminative representation. In addition, combining the two features achieves a better balance between the SEN and SPE metrics, with a notable improvement in the SEN value. Therefore, Mel-FBank and Mel-Spectrogram features are combined for respiratory sound representation.

4.2. Performance Comparison of Various Feature Fusion Strategies

Based on the Mel-FBank and Mel-Spectrogram features, different fusion strategies are conducted for verifying the effectiveness. As shown in

Table 3, ADFF-Net achieves the best performance across all evaluation metrics among the four feature fusion strategies. This demonstrates that the combination of attention and skip connections enables more effective and balanced feature fusion. Specifically, Concat-AST yields the lowest SPE and HS values, although its SEN is slightly higher than that of AST-Concat. In contrast, AST-Concat shows relatively high SPE but suffers from the lowest SEN, which limits its applicability in clinical scenarios where correctly identifying positive cases (i.e., high sensitivity) is critical. Without skip connection, the ADFF-Net module outperforms both concatenation-based methods in terms of HS (58.49%) and SEN (42.06%), indicating that the attention mechanism alone contributes meaningfully to feature fusion effectiveness.

Overall, the results reveal the importance of integrating attention mechanisms with skip connections in the proposed ADFF-Net framework. This combination not only enables the model to dynamically focus on informative regions but also preserves low-level features, leading to more robust and generalizable representations. Such capabilities are especially beneficial in medical applications where maintaining high SEN and SPE is essential for reliable diagnosis and decision-making.

4.3. Current Achievement on the ICBHI2017 Database

Table 4 presents a comparative evaluation of recent RSC models using the ICBHI2017 database. All models were trained and evaluated under identical experimental conditions, using the official data splittings to ensure the reproducibility and fair comparison.

The proposed framework achieves comparative SOTA performance across all metrics, and its HS value verifies the effectiveness of the ADFF-Net module. BTS [

42] obtains the highest HS (63.54%), primarily driven by its highest SEN and strong SPE. This suggests BTS is well-balanced and especially suitable for scenarios where high SEN is critical (e.g., detecting as many abnormal cases as possible). CycleGuardian [

44] obtains the highest SPE (82.06%), indicating excellent capability in correctly identifying normal samples. It also maintains strong SEN and HS values, slightly behind BTS. The other models [

25,

26,

43] all show balanced performance that typically integrate contrastive learning, data augmentation, or domain adaptation, showing how leveraging large-scale or cross-domain techniques improves robustness.

5. Discussion

Despite the easy computing of diverse quantitative features, respiratory sound classification remains challenging [

5]. The proposed ADFF-Net framework achieves competitive SOTA performance on the ICBHI2017 database in the four-class classification task by using the official training and testing splits. This improvement is largely attributed to the introduced attention mechanism and skip connections, which effectively integrate both Mel-FBank and Mel-spectrogram features. When combined with AST [

9] pre-trained on the AudioSet database [

39], these components substantially enhance the performance.

5.1. Our Findings

The strong performance of the proposed ADFF-Net framework can be attributed to two key aspects, the use of dual-stream acoustic feature inputs and the novel architectural design of the attention-based fusion module with skip connections. First, combining Mel-FBank and Mel-spectrogram features effectively balances the classification metrics (

Table 2). For example, MFCC features yield the highest specificity (88.16%) but extremely low sensitivity (9.43%), reflecting a severe imbalance. By contrast, Mel-FBank features achieve a higher HS score (57.69%), slightly outperforming Mel-spectrogram features. Importantly, the combination of Mel-FBank and Mel-spectrogram features consistently outperforms any single feature input or other pairwise combinations, demonstrating their strong complementarity. Second, the ADFF-Net module achieves superior performance compared to baseline fusion strategies such as Concat-AST, AST-Concat, and ADFF-Net without skip connections (

Table 3). While simple concatenation remains a common approach for feature integration, it often lacks the capacity to exploit complex dependencies between features. More advanced strategies, such as feature-wise linear modulation for context-aware computation [

45] or cross-attention fusion for integrating multi-stream outputs [

46], highlight the need for principled fusion mechanisms. ADFF-Net addresses this by leveraging attention-guided fusion and skip connections to enhance feature interactions and stabilize learning. Overall, by jointly incorporating dual-branch acoustic inputs and an advanced fusion architecture, ADFF-Net achieves a balanced trade-off between sensitivity and specificity, while maintaining SOTA performance. This indicates strong generalization capability even under class imbalance conditions.

On the ICBHI2017 database, there is still considerable room for improvement in the four-class classification task (

Table 4). The HS values remain below 65.00%, with the best performance (63.54%) achieved by the BTS model [

42], which introduces a text–audio multi-modal approach leveraging metadata from respiratory sounds. Specifically, free-text descriptions derived from metadata, such as patient gender and age, recording device type, and recording location, are used to fine-tune a pre-trained multi-modal model. Meanwhile, similar advanced techniques are commonly adopted in recent SOTA methods, including large-scale models [

24,

26,

43], contrastive learning [

25,

43,

44], fine-tuning strategies [

24,

26], and data augmentation or cross-domain adaptation [

24,

25,

43]. A key limitation underlying the low HS values is the poor SEN, which typically ranges between 42.31% and 45.67%. In clinic, low SEN is particularly problematic in disease diagnosis because it implies failure to detect a substantial portion of true patients, leading to missed diagnoses that may delay treatment, worsen outcomes, or even pose life-threatening risks. On the other hand, even with high SPE, such low SEN undermines clinical trust, as both doctors and patients prioritize avoiding missed disease cases. Thus, improving SEN remains critical. Promising directions include enhancing data balance, applying careful threshold tuning, designing architectures that better capture fine-grained features, and conducting multi-center validation with additional related databases [

5].

5.2. Future Directions

While substantial improvement in structural design and classification performance is achieved in the four-class prediction task on the ICBHI2017 database, several directions remain open for future investigation.

An important direction is balancing the number of patient cases across categories in respiratory sound databases [

4]. Imbalanced datasets often bias models toward majority classes, resulting in poor sensitivity for minority categories [

5]. Several strategies can be considered to address this issue. First, expanding clinical collaborations can help collect more recordings from underrepresented disease categories, ensuring a more representative distribution of patient conditions. However, this approach is resource-intensive, requiring significant time, expert involvement, and funding. Second, data augmentation can be applied using signal processing techniques such as time-stretching, pitch shifting, noise injection, or spectrogram-level transformations to artificially increase the diversity of existing samples [

5]. Third, generative modeling offers a promising direction, where realistic synthetic respiratory sound samples are produced to enrich minority categories while maintaining clinical validity [

47,

48]. In addition, domain adaptation provides another feasible solution by mitigating distribution shifts across recording devices, patient populations, or clinical centers [

9,

24,

25,

26,

43]. This can effectively increase usable data samples and improve the generalization of deep learning models.

Diverse signal collection is another direction essential for advancing respiratory sound analysis. Relying solely on acoustic signals may restrict a model’s ability to capture whole relevant information. Four complementary directions can be considered. First, fully exploiting acoustic signals remains fundamental. High-quality respiratory sound recordings are the core modality, and improvements such as multi-site recordings and standardized acquisition protocols [

4,

5] can enhance reliability while reducing noise-related biases. Second, incorporating additional modalities can provide richer diagnostic context. For instance, integrating physiological signals or chest imaging data can complement acoustic features and improve robustness in clinical decision-making [

41]. Finally, leveraging contextual metadata, including patient age, gender, medical history, recording device type, and auscultation location, provides valuable cues that refine model predictions and support more personalized assessments [

42]. Besides, the transformation of respiratory sounds into diverse quantitative forms, not limited to MFCCs, Mel-spectrograms and deeply learned features [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26], facilitates comprehensive information representation [

5], enabling more effective discriminative feature identification and knowledge discovery.

Advances in network design are also key to driving further improvements in RSC performance. First, Transformer architectures remain the dominant backbone, often outperforming traditional deep networks. Their self-attention mechanisms allow models to capture long-range temporal dependencies in acoustic signals and highlight subtle but clinically relevant sound events [

14,

15,

16,

23,

24,

25,

26]. Second, extending large multi-modal models to integrate respiratory sounds, free-text patient descriptions, additional modalities, and acoustic feature interpretations can provide more comprehensive and context-aware representations [

42,

49]. This integration bridges the gap between signal-level patterns and clinical knowledge, thereby enhancing model robustness and generalization. In addition, other advanced strategies hold significant promise for boosting performance and clinical applicability. These include multi-task learning, which enables joint optimization of related tasks such as RSC and disease diagnosis [

50]; contrastive learning, which facilitates the extraction of discriminative embeddings under limited labeled data [

25,

43,

44]; and domain adaptation, which mitigates distribution shifts across recording devices, patient populations, and clinical centers [

9,

24,

25,

26,

43].

6. Conclusion

This study introduces the ADFF-Net framework, a dual-stream feature fusion approach designed to advance RSC performance by overcoming limitations in modeling semantic complementarity across diverse features. By integrating attention mechanisms and skip connections, ADFF-Net effectively combines Mel-FBank and Mel-Spectrogram representations while preserving fine-grained spectral details. The framework achieves competitive SOTA performance on the ICBHI2017 database, demonstrating its capacity to extract more informative and clinically relevant acoustic features. Beyond its empirical results, ADFF-Net highlights the importance of feature complementarity and architectural design in biomedical acoustic analysis, offering insights that can inspire future respiratory sound research. Promising directions for further work include balancing patient distributions across categories to reduce data bias, expanding signal collection and feature diversity to improve generalizability, and developing advanced network designs to further enhance robustness and clinical applicability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.Z., S.Y. and Q.S.; Data curation, B.Z., L.C. and S.Z.; Formal analysis, X.L., Y.X. and Q.S.; Funding acquisition, L.C., X.L. and Q.S.; Investigation, S.Y. and Q.S.; Methodology, B.Z., L.C. and X.L.; Project administration, Q.S.; Software, B.Z., L.C. and X.L.; Supervision, Q.S.; Validation, S.Y. and S.Z.; Visualization, L.C., S.Z. and X.L.; Writing - original draft, L.C. and S.Y.; Writing - review & editing, B.Z., S.Y. and Q.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was in part supported by the National Key Research and Develop Program ofChina (Grant No. 2024YFF0907401, 2022ZD0115901, and 2022YFC2409000), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62177007, U20A20373, and 82202954), the China-Central Eastern European Countries High Education Joint Education Project (Grant No. 202012), the Application of Trusted Education Digital Identity in the Construction of Smart Campus in Vocational Colleges (Grant No. 2242000393), the Knowledge Blockchain Research Fund (Grant No. 500230), and the Medium- and Long-term Technology Plan for Radio, Television and Online Audiovisual (Grant No. ZG23011). The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADFF-Net |

Attention-based Dual-stream Feature Fusion Network |

| COPD |

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| ICBHI |

International Conference on Biomedical and Health Informatics |

| ICBHI2017 |

ICBHI 2017 database |

| CNN |

Convolutional Neural Network |

| RSC |

Respiratory Sound Classification |

| RNN |

Recurrent Neural Network |

| LSTM |

Long Short-Term Memory |

| AST |

Audio Spectrogram Transformer |

| Mel-FBank |

Mel-Filter Bank |

| MFCC |

Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficient |

| SOTA |

State-Of-The-Art |

| CQT |

Constant-Q Transform |

| STFT |

Short-Time Fourier Transform |

| DCT |

Discrete Cosine Transform |

| FFT |

Fast Fourier Transform |

| dB |

decibel |

| PE |

Positional Encoding |

| SPE |

Specificity |

| SEN |

Sensitivity |

| HS |

The ICBHI score |

References

- World Health Organization. World health statistics 2025: Monitoring health for the SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals. World Health Organization, Geneva, 2025, 7.

- Arabi, Yaseen M and Azoulay, Elie and Al-Dorzi, Hasan M and Phua, Jason and Salluh, Jorge and Binnie, Alexandra and Hodgson, Carol and Angus, Derek C and Cecconi, Maurizio and Du, Bin and others. How the COVID-19 pandemic will change the future of critical care. Intensive care medicine, 2021, 47, 282–291. [CrossRef]

- Arts, Luca and Lim, Endry Hartono Taslim and van de Ven, Peter Marinus and Heunks, Leo and Tuinman, Pieter R. The diagnostic accuracy of lung auscultation in adult patients with acute pulmonary pathologies: a meta-analysis. Scientific Reports 2020, 10(1), 7347. [CrossRef]

- Rocha, BM and Filos, Dimitris and Mendes, Lea and Vogiatzis, Ioannis and Perantoni, Eleni and Kaimakamis, Evangelos and Natsiavas, P and Oliveira, Ana and Jácome, C and Marques, A and others. A respiratory sound database for the development of automated classification. Precision Medicine Powered by pHealth and Connected Health: ICBHI 2017, Thessaloniki, Greece, 18-21 November 2017, 2018,33–37.

- Yu, Shaode and Yu, Jieyang and Chen, Lijun and Zhu, Bing and Liang, Xiaokun and Xie, Yaoqin and Sun, Qiurui. Advances and Challenges in Respiratory Sound Analysis: A Technique Review Based on the ICBHI2017 Database. Electronics 2025, 14(14), 2794. [CrossRef]

- Bohadana, Abraham and Izbicki, Gabriel and Kraman, Steve S. Fundamentals of lung auscultation. New England Journal of Medicine 2014, 370(8), 744–751. [CrossRef]

- Flietstra, B and Markuzon, Natasha and Vyshedskiy, Andrey and Murphy, R. Automated analysis of crackles in patients with interstitial pulmonary fibrosis. Pulmonary medicine 2011, 2011(1), 590506. [CrossRef]

- Reichert, Sandra and Gass, Raymond and Brandt, Christian and Andrès, Emmanuel. Analysis of respiratory sounds: state of the art. Clinical medicine. Circulatory, respiratory and pulmonary medicine,2008, 2, CCRPM–S530. [CrossRef]

- Gong, Yuan and Chung, Yu-An and Glass, James. AST: Audio spectrogram transformer. Proceedings of Interspeech 2021 2021, 571–575.

- Vaswani, Ashish and Shazeer, Noam and Parmar, Niki and Uszkoreit, Jakob and Jones, Llion and Gomez, Aidan N. and Kaiser, Łukasz and Polosukhin, Illia. Attention is all you need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2017, 30.

- Yang, Zijiang and Liu, Shuo and Song, Meishu and Parada-Cabaleiro, Emilia and Schuller, Björn W. Adventitious respiratory classification using attentive residual neural networks. Proceedings of Interspeech 2020 2020, 2912–2916.

- Xu, Lei and Cheng, Jianhong and Liu, Jin and Kuang, Hulin and Wu, Fan and Wang, Jianxin. Arsc-net: Adventitious respiratory sound classification network using parallel paths with channel-spatial attention. Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM) 2021, 1125–1130.

- Zhang, Yipeng and Huang, Qiong and Sun, Wenhui and Chen, Fenlan and Lin, Dongmei and Chen, Fuming. Research on lung sound classification model based on dual-channel CNN-LSTM algorithm. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2024, 94, 106257. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Changyi and Huang, Dongmin and Tao, Xiaoting and Qiao, Kun and Lu, Hongzhou and Wang, Wenjin. Intelligent stethoscope using full self-attention mechanism for abnormal respiratory sound recognition. Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE EMBS International Conference on Biomedical and Health Informatics 2023, 1, 1–4.

- Ariyanti, Whenty and Liu, Kai-Chun and Chen, Kuan-Yu and others. Abnormal respiratory sound identification using audio-spectrogram vision transformer. Proceedings of the 2023 45th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC) 2023, 1–4.

- Bae, Sangmin and Kim, June-Woo and Cho, Won-Yang and Baek, Hyerim and Son, Soyoun and Lee, Byungjo and Ha, Changwan and Tae, Kyongpil and Kim, Sungnyun and Yun, Se-Young. Patch-mix contrastive learning with audio spectrogram transformer on respiratory sound classification. Proceedings of INTERSPEECH 2023 2023, 5436–5440.

- Davis, Steven and Mermelstein, Paul. Comparison of parametric representations for monosyllabic word recognition in continuously spoken sentences. IEEE transactions on acoustics, speech, and signal processing 1980, 28(4), 357–366. [CrossRef]

- Bacanin, Nebojsa and Jovanovic, Luka and Stoean, Ruxandra and Stoean, Catalin and Zivkovic, Miodrag and Antonijevic, Milos and Dobrojevic, Milos. Respiratory condition detection using audio analysis and convolutional neural networks optimized by modified metaheuristics. Axioms 2024, 13(5), 335. [CrossRef]

- Zhu B, Li X, Feng J, Yu S. VGGish-BiLSTM-attention for COVID-19 identification using cough sound analysis. 2023 8th International Conference on Signal and Image Processing 2023, 49-53.

- Wall C, Zhang L, Yu Y, Kumar A, Gao R. A deep ensemble neural network with attention mechanisms for lung abnormality classification using audio inputs. Sensors 2022, 22(15), 5566. [CrossRef]

- Latifi, Seyed Amir; Ghassemian, Hassan; Imani, Maryam. Feature extraction and classification of respiratory sound and lung diseases. Proceedings of the 2023 6th International Conference on Pattern Recognition and Image Analysis 2023, 1, 1–6.

- Li, Xiaoqiong; Qi, Bei; Wan, Xiao; Zhang, Jingwen; Yang, Wei; Xiao, Yongjun; Mao, Fuwei; Cai, Kailin; Huang, Liang; Zhou, Jun. Electret-based flexible pressure sensor for respiratory diseases auxiliary diagnosis system using machine learning technique. Nano Energy 2023, 114, 108652. [CrossRef]

- Neto, José; Arrais, Nicksson; Vinuto, Tiago; Lucena, João. Convolution-vision transformer for automatic lung sound classification. Proceedings of the 2022 35th SIBGRAPI Conference on Graphics, Patterns and Images 2022, 1, 97–102.

- Kim, June-Woo and Yoon, Chihyeon and Toikkanen, Miika and Bae, Sangmin and Jung, Ho-Young. Adversarial fine-tuning using generated respiratory sound to address class imbalance. Deep Generative Models for Health Workshop NeurIPS 2023 2023.

- Kim, June-Woo and Bae, Sangmin and Cho, Won-Yang and Lee, Byungjo and Jung, Ho-Young. Stethoscope-guided supervised contrastive learning for cross-domain adaptation on respiratory sound classification. Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP) 2024, 1431–1435.

- Xiao, L.; Fang, L.; Yang, Y.; Tu, W. LungAdapter: Efficient Adapting Audio Spectrogram Transformer for Lung Sound Classification. In Proceedings of the 25th Annual Conference of the International Speech Communication Association (INTERSPEECH 2024), Kos Island, Greece, 1–5 September 2024; pp. 4738–4742.

- Chu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, E.; Zheng, G.; Liu, Q. Hybrid Spectrogram for the Automatic Respiratory Sound Classification With Group Time Frequency Attention Network. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 6th International Conference on Pattern Recognition and Artificial Intelligence (PRAI), Haikou, China, 18—20 August 2023; pp. 839–845.

- Borwankar, Saumya; Verma, Jai Prakash; Jain, Rachna; Nayyar, Anand. Improvise approach for respiratory pathologies classification with multilayer convolutional neural networks. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2022, 81(27), 39185–39205. [CrossRef]

- Roy, Arka; Satija, Udit; Karmakar, Saurabh. Pulmo-TS2ONN: a novel triple scale self operational neural network for pulmonary disorder detection using respiratory sounds. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2024, 73, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Roy, Arka; Satija, Udit. A novel multi-head self-organized operational neural network architecture for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease detection using lung sounds. IEEE/ACM Transactions on Audio, Speech, and Language Processing 2024, 32, 2566–2575. [CrossRef]

- Wanasinghe, Thinira; Bandara, Sakuni; Madusanka, Supun; Meedeniya, Dulani; Bandara, Meelan; De La Torre, Isabel Díez. Lung sound classification with multi-feature integration utilizing lightweight CNN model. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 21262–21276. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Wenlong and Bao, Xiaofan and Lou, Xiaomin and Liu, Xiaofang and Chen, Yuanyuan and Zhao, Xiaoqiang and Zhang, Chenlu and Pan, Chen and Liu, Wenlong and Liu, Feng. Feature fusion method for pulmonary tuberculosis patient detection based on cough sound. PLOS ONE 2024, 19(5), e0302651. [CrossRef]

- Pham, Lam and Ngo, Dat and Tran, Khoa and Hoang, Truong and Schindler, Alexander and McLoughlin, Ian. An ensemble of deep learning frameworks for predicting respiratory anomalies. Proceedings of the 2022 44th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC) 2022, 4595–4598.

- Shehab, Sara A. and Mohammed, Kamel K. and Darwish, Ashraf and Hassanien, Aboul Ella. Deep learning and feature fusion-based lung sound recognition model to diagnoses the respiratory diseases. Soft Computing 2024, 28(19), 11667–11683. [CrossRef]

- McFee, Brian and Raffel, Colin and Liang, Dawen and Ellis, Daniel PW and McVicar, Matt and Battenberg, Eric and Nieto, Oriol. librosa: Audio and music signal analysis in python. SciPy 2015, 1, 18–24. [CrossRef]

- Jung, Jee-Weon and Heo, Hee-Soo and Yang, Il-Ho and Shim, Hye-Jin and Yu, Ha-Jin. A complete end-to-end speaker verification system using deep neural networks: From raw signals to verification result. IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing 2018, 1, 5349–5353.

- Dosovitskiy, Alexey and Beyer, Lucas and Kolesnikov, Alexander and Weissenborn, Dirk and Zhai, Xiaohua and Unterthiner, Thomas and Dehghani, Mostafa and Minderer, Matthias and Heigold, Georg and Gelly, Sylvain and Uszkoreit, Jakob and Houlsby, Neil. An image is worth 16x16 words: transformers for image recognition at scale. International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) 2021.

- Deng, Jia and Dong, Wei and Socher, Richard and Li, Li-Jia and Li, Kai and Fei-Fei, Li. Imagenet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition 2009, 1, 248–255.

- Gemmeke, Jort F and Ellis, Daniel PW and Freedman, Dylan and Jansen, Aren and Lawrence, Wade and Moore, R Channing and Plakal, Manoj and Ritter, Marvin. Audio set: An ontology and human-labeled dataset for audio events. IEEE international conference on acoustics, speech and signal processing (ICASSP) 2017, 1, 776–780.

- Zou, L.; Yu, S.; Meng, T.; Zhang, Z.; Liang, X.; Xie, Y. A Technical Review of Convolutional Neural Network-Based Mammographic Breast Cancer Diagnosis. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2019, 1, 6509357. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Zhou, Z.; Yu, S.; Liang, X.; Xie, Y.; Sun, Q. Review of phonocardiogram signal analysis: Insights from the PhysioNet/CinC challenge 2016 database. Electronics 2024, 13, 3222.

- Kim, J.W.; Toikkanen, M.; Choi, Y.; Moon, S.E.; Jung, H.Y. BTS: Bridging Text and Sound Modalities for Metadata-Aided Respiratory Sound Classification. In Proceedings of the 25th Annual Conference of the International Speech Communication Association (INTERSPEECH 2024), Kos Island, Greece, 1–5 September 2024;1690–1694.

- Bae, S.; Kim, J.W.; Cho, W.Y.; Baek, H.; Son, S.; Lee, B.; Ha, C.; Tae, K.; Kim, S.; Yun, S.Y. Patch-Mix Contrastive Learning with Audio Spectrogram Transformer on Respiratory Sound Classification. In Proceedings of the 24th Annual Conference of the International Speech Communication Association (INTERSPEECH 2023) Dublin, Ireland, 20–24 August 2023; 5436–5440.

- Chu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, E.; Fu, L.; Liu, Q.; Zheng, G. CycleGuardian: A Framework for Automatic Respiratory Sound Classification Based on Improved Deep Clustering and Contrastive Learning. Complex Intell. Syst. 2025, 11, 200. [CrossRef]

- Perez, Ethan and Florian Strub, Harm De Vries and Vincent, Dumoulin and Aaron Courville. FiLM: Visual reasoning with a general conditioning layer. Proceedings of the AAAI conference on Artificial Intelligence 2018, 32(1), 3942–3951. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Shaode and Meng, Jiajian and Fan, Wenqing and Chen, Ye and Zhu, Bing and Yu, Hang and Xie, Yaoqin and Sun, Qiurui. Speech emotion recognition using dual-stream representation and cross-attention fusion. Electronics 2024, 13(11), 2191. [CrossRef]

- Jayalakshmy, S. and Sudha, G.F. Conditional GAN based augmentation for predictive modeling of respiratory signals. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2021, 138, 104930. [CrossRef]

- Pessoa, D., Rocha, B.M., Gomes, M., Rodrigues, G., Petmezas, G., Cheimariotis, G.A., Maglaveras, N., Marques, A., Frerichs, I., de Carvalho, P. and Paiva, R.P. Ensemble deep learning model for dimensionless respiratory airflow estimation using respiratory sound. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2024, 87, 105451. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Xiao and Chen, Guangyao and Qian, Guangwu and Gao, Pengcheng and Wei, Xiao-Yong and Wang, Yaowei and Tian, Yonghong and Gao, Wen. Large-scale multi-modal pre-trained models: A comprehensive survey. Machine Intelligence Research 2023, 20(4), 447–482. [CrossRef]

- Kim, June-Woo and Lee, Sanghoon and Toikkanen, Miika and Hwang, Daehwan and Kim, Kyunghoon. Tri-MTL: A Triple Multitask Learning Approach for Respiratory Disease Diagnosis. arXiv preprint 2025, arXiv, 2505.06271.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).