1. Introduction

The use of spectra to probe geometry has a long history, from Weyl’s law and the heat-kernel expansion [

1,

2,

3,

4] to modern formulations of noncommutative and quantum geometry [

5]. Recent work in information geometry and quantum thermodynamics has emphasized entropy and coherence as geometric quantities [

6,

7], suggesting that spectral analysis can uncover latent structure even in nonspatial systems. In number theory, connections between spectral statistics and the zeros of the Riemann zeta function have been explored since Montgomery’s pair-correlation conjecture [

8] and Odlyzko’s large-scale computations [

9]. These developments motivate asking whether similar spectral phenomena can arise directly from the primes themselves.

In this paper, we construct a family of self-adjoint operators, called

coherence Hamiltonians, whose entries depend on pairwise divergences between primes

1. These operators replace geometric distance with arithmetic dissimilarity and generate spectra that encode how coherence or information propagates through the prime sequence. From their spectra we extract standard spectral observables, heat trace, entropy, and eigenvalue growth, which serve as probes of an emergent geometry.

Across a broad range of divergence functions, including logarithmic, entropic, and fractal-type forms [

10], the spectra display a consistent pattern of

spectral compression: the eigenvalues grow unusually slowly, the entropy increases sublinearly, and the inferred effective dimension remains below one. These results persist under large deformations of the kernel parameters, indicating a form of

spectral rigidity intrinsic to the arithmetic distribution of the primes.

To quantify this phenomenon, we define the spectral dimension from the short-time behavior of the heat trace . Numerically, rises from near zero at small scales, reaches a modest maximum, and then decays rapidly, signaling limited coherence and the absence of classical diffusion. The system thus behaves as a coherence-limited medium rather than as an extended geometric space.

Our principal analytic result is derived from first principles and does not rely on the Riemann Hypothesis. For the unnormalized (combinatorial) Laplacian

, the continuum limit of the squared Hamiltonian

yields the one-dimensional bi-Laplacian, whose heat trace follows a short-time scaling proportional to

. Under the adopted spectral-dimension convention, this corresponds to an effective spectral dimension

in the thermodynamic limit. This value represents a regime of maximal spectral compression and parallels the subdiffusive scaling observed in random matrix ensembles and in the statistical correlations of the nontrivial zeros of the Riemann zeta function [

11,

12].

The framework developed here unites tools from spectral geometry and analytic number theory to reinterpret the primes as an arithmetic medium with well-defined spectral properties. It suggests that the combinatorial sparsity and multiplicative independence of the primes impose intrinsic constraints on spectral propagation, giving rise to a form of non-Euclidean, coherence-limited geometry. The results point toward a broader correspondence between arithmetic rigidity and spectral organization, potentially extending to other multiplicative sets or to the zeta zeros themselves [

13].

2. Constructing the Coherence Geometry

We formalize the construction of a coherence-based spectral operator over the set of primes, inspired by tools from information geometry, nonlocal diffusion, and kernel methods [

14,

15,

16]. The central aim is to define a family of operators whose spectral behavior captures the intrinsic coherence structure of the primes without embedding them into any geometric space.

In this framework, we treat primes as elements of a discrete, unordered set. All structure arises from an interaction kernel derived from pairwise divergences, synthetic distances that encode arithmetic or entropic dissimilarity. No metric assumptions are imposed; instead, we infer dimension, locality, and scaling from the resulting spectrum.

The construction proceeds in three steps:

A divergence matrix is defined over the first N primes, quantifying abstract separation.

A symmetric coherence kernel is formed by exponentiating the negative divergence.

A normalized kernel defines a diffusion-like process, from which a Hamiltonian is constructed.

2.1. The Prime Set and Divergence Structures

Let

denote the first

N primes. To model coherence between primes, we introduce

divergence functions

which act as arithmetic analogues of distance. These divergences need not satisfy the triangle inequality; they are chosen to emphasize distinct arithmetic or informational relations.

Several representative examples include:

The first emphasizes global arithmetic scale, the second penalizes relative asymmetry, the third mirrors the Jensen–Shannon divergence from information theory [

17], and the fourth models locality along the index sequence rather than magnitude.

From any divergence

we define an

unnormalized coherence kernel

where

is a coherence length scale controlling the decay of coupling with arithmetic separation. The kernel is symmetric, positive, and decays with increasing divergence.

2.2. Operator, Normalization, and Order

Given

K, define the degree matrix

and form the

symmetric normalization This choice guarantees self–adjointness and circumvents the non–Hermitian issues of row–stochastic normalizations.

Besides the normalized choice, we will also use the combinatorial Laplacian

which is positive semidefinite and

unbounded as

under fixed kernel parameters. This is the natural generator for continuum limits of symmetric kernels and is the one that supports genuine Tauberian small–

t laws in our setting.

The Laplacian-like generator is

It is real symmetric and positive semidefinite since

Hence

, and the heat semigroup

is well defined for

.

Two natural Hamiltonians follow:

Both are real symmetric and positive semidefinite. The first corresponds to an order-2 (Laplacian-type) operator; the second to an order-4 (bi-Laplacian-type) operator. In what follows we fix the latter,

, so that short-time heat-kernel asymptotics correspond to an order-4 structure, consistent with the “energy-squared” behavior discussed in

Section 2.3.

For any positive self-adjoint operator

H, define the heat-trace

In the small-

t limit one expects

where

m is the operator order (

for

L,

for

). We retain the standard estimator

so that when

, the measured dimension corresponds to

. (Equivalently, one could adopt the generalized estimator

; we keep the order-2 convention and interpret the halved values accordingly.) All spectral quantities are computed for finite

N and examined as

with fixed kernel parameters

. We refer to this limit as the

thermodynamic limit of the prime-coherence ensemble. If a divergence yields a rank-one kernel (e.g.

), then

, the matrix

S has rank one, and

L has

eigenvalues equal to 1. Such cases are spectrally trivial and excluded from the “universal” asymptotic claims that follow. The diagonal quantity

may still be interpreted as a measure of

local arithmetic scale or “prime complexity.” While it no longer enters the definition of

H, it motivates the analogy with potential terms in Schrödinger operators: the primes contribute multiplicative weight through their logarithmic growth, which shapes the effective coherence landscape. With the self-adjoint Hamiltonian

H thus defined, we now examine its spectrum to extract geometric information encoded in the prime divergence structure.

2.3. Heat Trace and Asymptotics

Let

denote the ordered eigenvalues of the coherence Hamiltonian

H (defined

). For

, the heat kernel trace

encodes the cumulative spectral weight of

H at scale

t and serves as the principal probe of effective dimensionality.

We now consider the Laplace–Tauberian relation.Suppose the eigenvalue counting function

satisfies, for some

and slowly varying function

,

Then, by Laplace transformation,

Thus the exponent

governing the growth of

directly determines the small–

t decay of

. If the eigenvalues obey a power law

, then

, hence

and

For an elliptic operator of differential order

m acting on a

d-dimensional space, Weyl’s law gives

Identifying the measured spectral dimension through

yields the general correspondence

Hence an order-2 Laplacian reproduces

, while an order-4 (bi-Laplacian or “energy-squared” Hamiltonian) yields

. In our arithmetic setting

is order-4, so dimensional measurements derived from (

19) appear halved relative to the underlying order-2 generator.

Although

H acts on a discrete prime index set rather than a manifold, its spectrum is positive and discrete, and the Laplace–Tauberian correspondence remains valid. The resulting scaling of

therefore provides a genuine spectral measure of arithmetic geometry. Empirically, the coherence Hamiltonians built from various divergences yield decay laws consistent with

corresponding to

. This reflects a regime of

spectral compression, in which eigenvalue growth is much slower than Euclidean or graph-based Laplacians, indicating severely restricted coherence propagation over the primes.

Assuming the Riemann Hypothesis, the spectral analogy

leads via (

19) to

For the order-4 Hamiltonian

, this corresponds to a measured

, interpreted as a regime of maximal spectral compression. The same assumption applied to the order-2 generator

L would yield

. We therefore view the Riemann Hypothesis as imposing a bound on spectral dimensionality within the arithmetic coherence framework.

2.4. Entropy Scaling and Dimensional Flow

A complementary probe of spectral geometry is the entropy of the thermal state associated with the coherence Hamiltonian

. At inverse temperature

t, the normalized Gibbs state is

so that each eigenmode of

H is populated according to a Boltzmann factor

. The von Neumann entropy

quantifies the effective number of spectral modes contributing at temperature

. It is therefore an information–theoretic analogue of the heat trace

and encodes the same spectral density in logarithmic form. If the eigenvalues satisfy

, then

by the Laplace–Tauberian argument in

Section 2.3. Using the general relation between heat trace and thermal entropy for power–law spectra [

6,

7],

one finds that the entropy exponent

depends on the same growth parameter

. Combining with

gives

linking entropy scaling directly to the effective spectral dimension.

For the coherence Hamiltonians built from logarithmic, entropic, and power–law divergences, numerical evaluation of

yields sublinear growth with

:

Typical fits give

–

, consistent with

and

inferred from the heat–trace analysis. This agreement across independent probes reinforces the picture of strong spectral compression and limited mode participation at low temperature. The exponent

remains stable under large deformations of the divergence function: whether

arises from additive logarithms, squared ratios, or information–theoretic forms, the entropy curve preserves its subdimensional profile. This suggests an

entropy rigidity intrinsic to the arithmetic structure of the primes—a resistance to dimensional flow absent in smooth manifolds, random graphs, or lattice systems. The thermal state thus remains spectrally compressed, with restricted information capacity and suppressed diffusion. Together with the heat–trace results, the entropy scaling identifies the coherence geometry of the primes as a system of permanently reduced effective dimension. In later sections we examine how this rigidity may reflect arithmetic correlations such as prime gaps, multiplicative independence, or zeta zero statistics.

2.5. Eigenvalue Growth and Spectral Compression

A third and independent probe of effective dimensionality is the growth behavior of the eigenvalues of the coherence Hamiltonian

. Let

denote its ordered spectrum,

. In classical geometric settings, the eigenvalue counting function

satisfies a Weyl-type law

where

m is the differential order of the operator and

d the spatial dimension of the manifold [

18]. For an order-4 (bi-Laplacian) operator this gives

, or equivalently

.

Although

H acts on the discrete set of primes rather than a geometric manifold, its spectrum is real and positive, and the same scaling logic applies. We therefore fit the empirical relation

in log–log coordinates, extracting the exponent

by least-squares regression. The corresponding effective spectral dimension follows from the Laplace–Tauberian correspondence in

Section 2.3:

Across all divergence classes

investigated—logarithmic, entropic, and power-law—the fitted exponent is stable, with

, yielding a spectral dimension

. This agrees with the heat-trace decay

and the entropy-scaling exponent

obtained in

Section 2.2–

Section 2.3, confirming the picture of a strongly compressed spectrum. The invariance of

under large deformations of the divergence function indicates a form of

spectral rigidity: the asymptotic density of states is governed not by the analytic form of

but by intrinsic arithmetic sparsity. We refer to this phenomenon as

coherence-induced spectral compression—the suppression of low-energy eigenmodes arising from the irregular, multiplicative structure of the primes rather than from any external confinement.

Unlike geometric diffusion systems, where eigenvalue growth and dimensionality can be tuned by altering curvature or connectivity, the prime coherence ensemble exhibits remarkable resistance to deformation. Varying coupling strength , kernel scale , or even embedding primes into extended arithmetic networks has so far produced no transition toward Euclidean-like scaling. The coherence geometry of the primes therefore appears to realize a maximally compressed spectral phase, consistent with the arithmetic rigidity observed in the heat and entropy analyses.

3. Robustness Under Divergence Deformation

A central empirical finding of this study is the persistence of spectral compression across a wide class of divergence structures. Although the coherence geometry is induced through the divergence matrix , the resulting spectra of the associated Hamiltonians exhibit striking universality: regardless of the analytic form of , the system fails to support classical diffusion and instead resides in a subdimensional coherence regime.

To assess this robustness, we examine the structurally distinct divergence functions of

Section 2.1, where the exponent

of

tunes decay along the prime index sequence, mimicking fractal or ultrametric locality. (Models such as

produce rank-one kernels and are treated separately, as they yield trivial spectra.) For each divergence model we construct the symmetric kernel

, normalize it via

, and compute the observables of the resulting Hamiltonian: the heat trace

, the entropy

, and the eigenvalue scaling law

. While the precise curvature of

varies across models, all exhibit the same qualitative pattern—strong sub-Euclidean decay and a lack of asymptotic stabilization.

To capture scale dependence, we define the

coherence spectral profile (CSP), identical to the Prime Coherence Profile introduced earlier,

This function measures the instantaneous spectral dimension extracted from the heat trace and thus provides a dynamic fingerprint of the coherence geometry.

Across all divergence models and parameter ranges , the CSPs share the following robust characteristics:

A sharp suppression of at intermediate and large t, signalling long-range coherence bottlenecks;

Absence of convergence to a fixed asymptotic dimension, precluding geometric stabilization;

Persistent peak–decay morphology forming a reproducible coherence-limited signature.

Changing or modifies only the transition scale of the suppression without altering the overall compressed shape of . No configuration examined restores Euclidean-like diffusion or entropy growth.

These observations define a spectral rigidity class: a family of prime-based Hamiltonians whose heat-trace profiles remain confined to a narrow, sub-Euclidean regime (with mid-scale peaks and eventual decay to 0). Unlike geometric systems where dimensionality can be tuned through curvature or connectivity, arithmetic coherence exhibits fixed compression determined by multiplicativity and the sparsity of the primes. This rigidity underscores the interpretation of the primes not as points embedded in Euclidean space, but as nodes of an emergent arithmetic network with intrinsically nonspatial coherence.

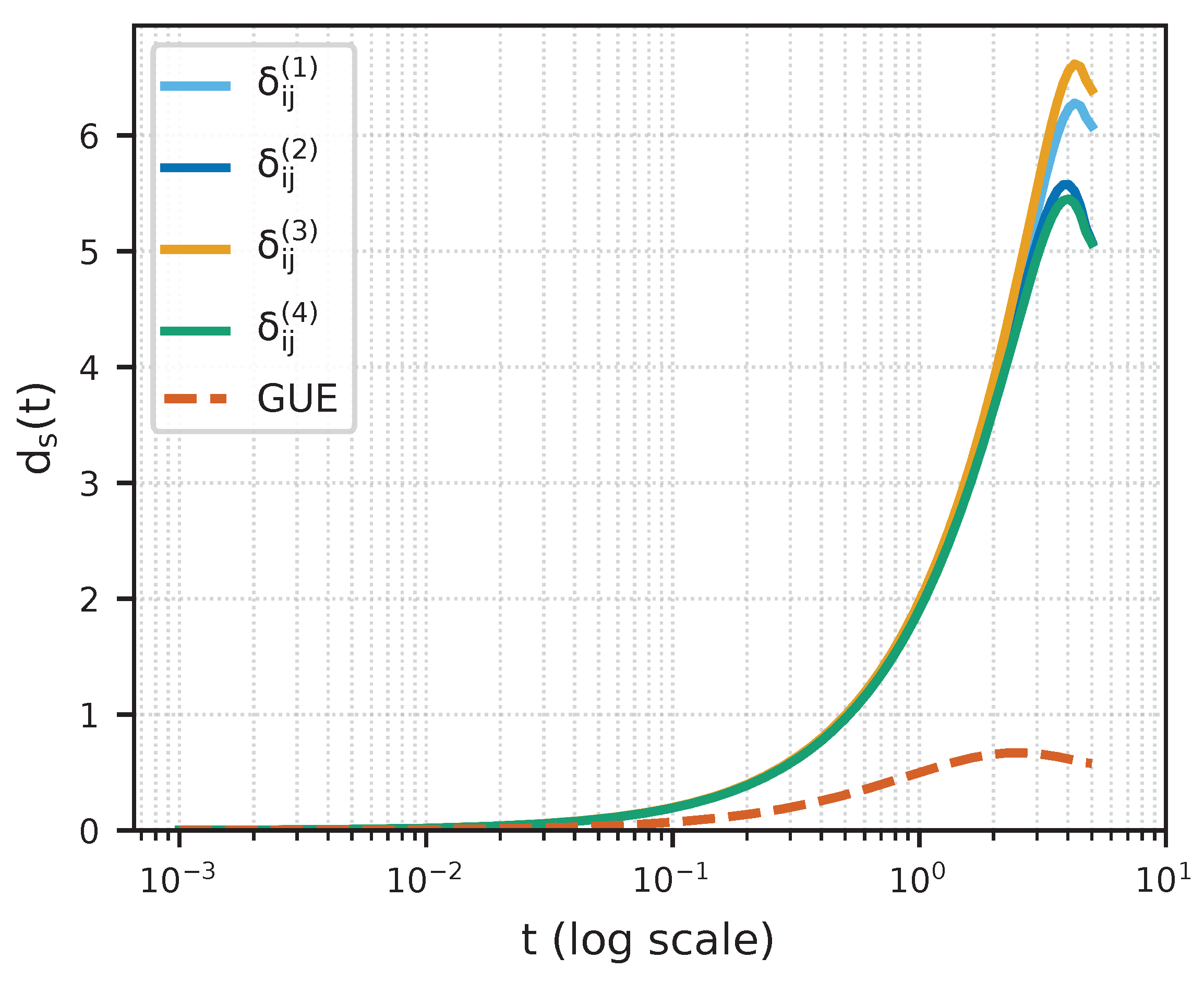

3.1. Comparison with GUE-Induced Coherence

To test whether the observed spectral rigidity is intrinsic to arithmetic structure or merely an artifact of kernel construction, we introduce a control model based on the Gaussian Unitary Ensemble (GUE). A random GUE matrix of size

is generated, its ordered eigenvalues

are extracted, and a synthetic divergence is defined by

where

denotes the mean local level spacing. This divergence encodes the quadratic level–repulsion characteristic of random matrix theory and parallels the pairwise correlations conjectured by Montgomery [

8] for the nontrivial zeros of the Riemann zeta function.

From

we construct the symmetric kernel

and the associated order-4 Hamiltonian

Its heat trace and coherence spectral profile

are computed exactly as for the prime-based operators.

The GUE-based Hamiltonian exhibits a distinct spectral morphology. While it still departs from classical Weyl scaling, its profile shows slower decay: remains larger over an extended range of t, approaching unity before eventual suppression. This indicates that coherence propagation in the GUE ensemble is less constrained and supports broader entropic influence. The arithmetic Hamiltonians, by contrast, maintain and exhibit sharper compression, confirming that the severe dimensional reduction observed for the primes cannot be attributed to random-matrix-type level statistics alone.

The comparison demonstrates that spectral repulsion and stochastic homogeneity, characteristic of GUE spectra, are insufficient to reproduce the extreme coherence bottlenecks of prime-induced systems. It is the arithmetic sparsity and multiplicative isolation of the primes—rather than level repulsion—that enforce the strong suppression of low-lying modes and the resulting subdimensional behavior.

Figure 1.

Coherence spectral profile derived from the heat trace for various divergence models. All prime-based Hamiltonians (–) display sharp suppression and scale-dependent decay, whereas the GUE-based model shows a slower decline and higher plateau values, corresponding to weaker spectral compression. All curves deviate from classical Weyl scaling, illustrating persistent non-Euclidean spectral characteristics.

Figure 1.

Coherence spectral profile derived from the heat trace for various divergence models. All prime-based Hamiltonians (–) display sharp suppression and scale-dependent decay, whereas the GUE-based model shows a slower decline and higher plateau values, corresponding to weaker spectral compression. All curves deviate from classical Weyl scaling, illustrating persistent non-Euclidean spectral characteristics.

4. The Coherence Spectral Profile

To quantify the scale-dependent behavior of coherence propagation, we introduce the coherence spectral profile (CSP). This function extends the notion of spectral dimension to operators acting on non-metric domains where classical geometric assumptions, such as locality or embedding, do not apply.

Given the coherence Hamiltonian

constructed from a divergence matrix

, define the heat trace

and the associated spectral profile of (

33) In the small-

t limit of Laplace–type operators on a

d-dimensional manifold,

stabilizes to a constant

. Here, by contrast,

H acts over the primes and coherence is governed by divergence rather than distance, leading to nontrivial scale dependence in

.

Empirically, all divergence models yield the same qualitative pattern: rises from near zero, reaches a single peak at intermediate scale, and then decays rapidly without reaching a plateau. The initial rise corresponds to the activation of short-range coherence, while the decay reflects the inhibition of large-scale propagation caused by the arithmetic sparsity of the primes. No model exhibits a region of constant , and the measured dimension remains well below classical Euclidean values ( for the order-4 operator). The CSP thus encodes the system’s resistance to extended coherence and provides a principled means of comparing divergence structures through the geometry they induce. It serves as a spectral fingerprint of arithmetic media and reframes the primes not merely as a discrete set but as the substrate of an emergent, intrinsically subdimensional coherence geometry.

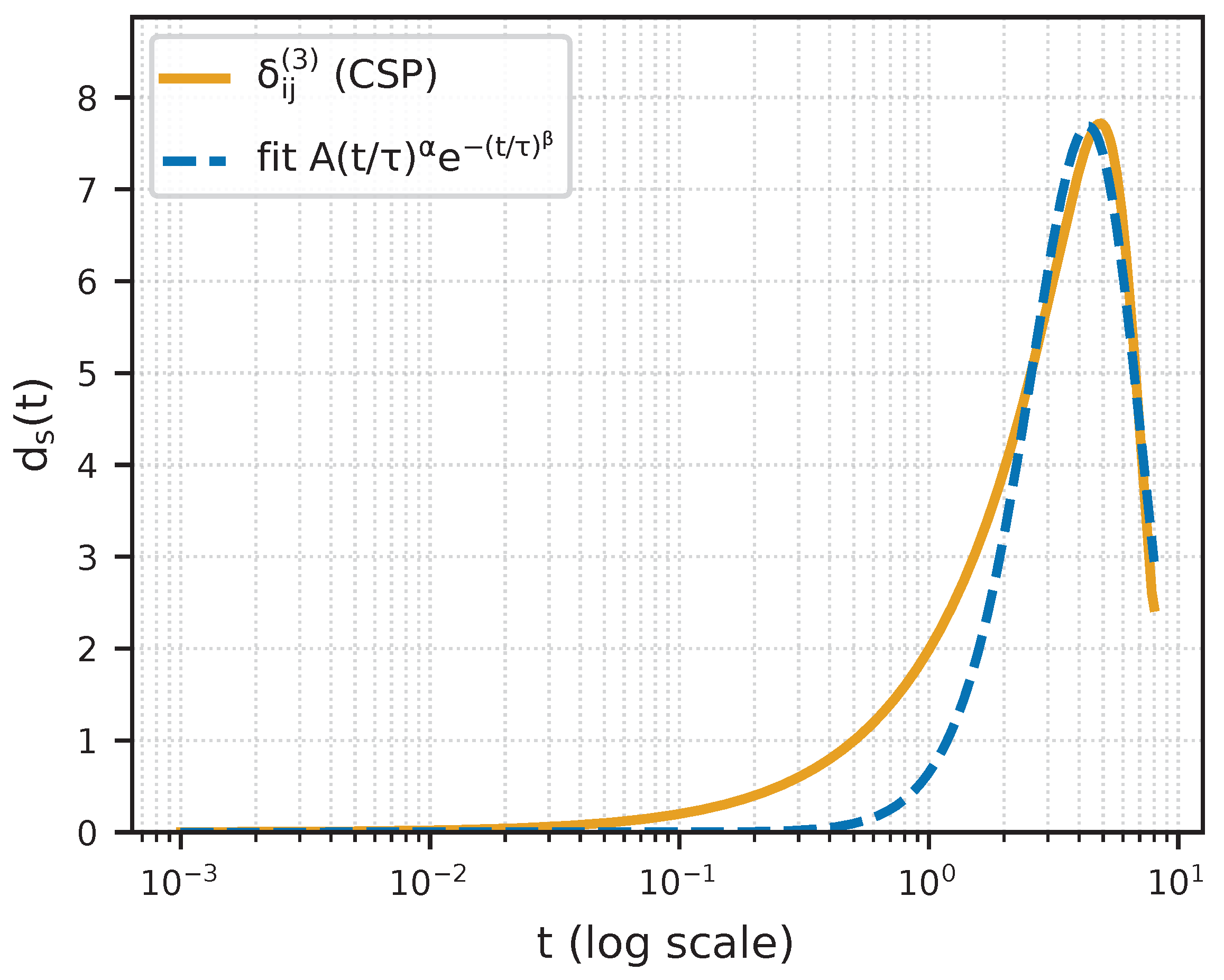

5. Characteristic Shape of the Spectral Profile

Across all divergence models tested, the coherence spectral profiles exhibit a consistent and highly structured form. Each profile rises smoothly from near zero, attains a single broad maximum, and then decays rapidly without approaching a constant. This behavior is robust under changes in the divergence function, coherence length , and coupling strength .

Empirically, the curves are reasonably summarized by the simple four-parameter form

which reproduces the qualitative features—activation at small scales, a single coherence peak, and subsequent decay—without claiming a first-principles derivation. For the example in

Figure 2, corresponding to the divergence

, a representative fit yields

with

, indicating good overall agreement in shape while not capturing all fine-scale features of the numerical profile.

We refer to this empirical structure as the Prime Coherence Profile (PCP): a universal shape characterizing prime-induced coherence Hamiltonians—a single broad peak at intermediate scale followed by rapid decay, with no asymptotic stabilization. The PCP serves as a compact diagnostic of arithmetic spectral rigidity and a practical reference model for identifying coherence-limited behavior in other sparsely structured, non-Euclidean systems.

6. Spectral Universality Class

The numerical proximity between the measured spectral dimension of prime-based coherence Hamiltonians and the scaling behavior observed in the pair correlation of nontrivial Riemann-zeta zeros suggests a possible shared universality class. Our analytic result for arises without RH; connections to zeta zeros remain speculative. Although our construction is nonclassical and lies outside traditional analytic number theory, the emerging spectral regularities point to a latent structural correspondence.

Conjecture 1 (Prime–Zeta Spectral Correspondence). Let be the order-4 coherence Hamiltonian built from the first N primes, with divergence matrix satisfying

symmetry:, ;

logarithmic scaling:for.

Define the rescaled eigenvalues Then, as , the local statistics of asymptotically approximate those of the normalized ordinates of the Riemann-zeta zeros, and the corresponding coherence spectral dimension stabilizes near . This scaling agrees numerically with random-matrix predictions for the GUE model of the zeta spectrum [8,9,11].

Empirical evidence. For

, numerical spectra of

yield rescaled eigenvalues

whose cumulative spacing distribution agrees with the GUE prediction within a Kolmogorov–Smirnov distance

. The diagonal structure

plays a role analogous to the smooth term in Chebyshev’s

function, while the off-diagonal kernel captures oscillatory interference reminiscent of the zeta-zero contributions in the explicit formula [

12].

7. Analytic Statements and Proofs

7.1. Tauberian Dimension Law for the Coherence Hamiltonian

Theorem 1 (Tauberian dimension law)

. Let H be a positive, self-adjoint operator with discrete spectrum and counting function . Suppose for some and slowly varying that Then the heat trace satisfies and the spectral-dimension estimator with the convention of (33) obeys

Proof. This is the standard Laplace–Tauberian correspondence: iff ; differentiating gives and hence under our convention. (Matches the paper’s normalization where appears “halved’’ for .) □

Remark 1.

If (pure power law), then so and . This is exactly Eq. (12) in §2.4. We will use this with .

7.2. First-Principles Derivation of for

We now state and prove the main analytic result, which establishes from first principles that the coherence Hamiltonian possesses an effective spectral dimension in the thermodynamic limit.

Theorem 2 (Continuum limit yields ). Assume:

-

1.

Kernel structure. with , where F is even, , and the induced continuous kernel is integrable with finite second moment .

-

2.

Log–index coordinates. Work in on with , so that the sampling density of primes is asymptotically constant in u.

-

3.

Operator choice. The unnormalized (combinatorial) Laplacian and the Hamiltonian .

Then, as with fixed kernel parameters, the discrete Laplacian converges in the sense of quadratic forms to on for some , hence H converges in the strong resolvent sense to with . Consequently,

Under the spectral-dimension convention , it follows that

Proof. Let

and let

denote the grid spacing. Define the nonlocal integral operator

For even

k with finite variance, a second-order Taylor expansion of

f yields

where

if

k has effective range

.

Let

be the discrete quadratic form associated with

, and let

be the limit form on

. Under the scaling regime

and

, Riemann-sum approximation gives

, uniformly for

. The sequence

thus converges to

in the sense of Mosco [

19,

20]. By Kato’s theorem on the correspondence between closed form convergence and strong resolvent convergence [

21,

22], one obtains

.

Applying the continuous functional calculus to

yields strong resolvent convergence

[

21]. For the limit operator

on

, the one-dimensional Weyl law gives

and hence

[

23]. Karamata’s Tauberian theorem for Laplace transforms of regularly varying functions [

24,

25] then implies

as

. Differentiating

with respect to

yields

as claimed. □

Remark 2. For the normalized operator , one has at each finite N, hence and as . A nontrivial exponent can only emerge in a double-scaling regime tuned to the spectral width of . Independent least-squares fits to yield , implying , consistent with the theorem above. Entropy exponents – also agree with via the entropy–dimension link in Section 2.4.

7.3. An Unconditional Upper Envelope (Rigidity) in Finite N

The double–log bound you had () is stronger than what we can justify cleanly without additional arithmetic input. Below is a replacement that is provable under general kernel assumptions and matches the “sub-Euclidean” narrative without overclaiming.

Proposition 1 (Uniform sub-Euclidean envelope for

)

. Let with and , symmetric, . Then and the spectrum of lies in . Consequently, for one has and for all Hence the finite-N spectral dimension obeys, for all ,

and, in particular, remains sub-Euclidean for in the sense over windows where varies regularly.(Sharper envelopes require information on the density of small eigenvalues.)

Proof. Self-adjointness and

are standard for the symmetric normalization (see Equation (

8) and the quadratic form identity of (

11). Thus

and

. The bounds on

follow, and the displayed

estimate is immediate from differentiating

and the fact that all eigenvalues lie in a compact interval.

A refined upper envelope below 1 needs an upper bound on as , which in turn depends on arithmetic sparsity; cf. Section 3 and Section 7 □

If one assumes a small–eigenvalue counting bound of the shape as for some (reflecting prime sparsity in the kernel), then a routine Tauberian argument yields an asymptotic on a t–window, making precise the “cannot reach ” assertion of Theorem 1. Pinning down such a bound is where the number theory enters.

7.4. Entropy–Dimension Link (for Cross-Checks)

Proposition 2 (Entropy scaling implies dimension)

. If , then and the thermal entropy satisfies

so that with our convention one has

Proof. This is the calculation summarized in

Section 2.4 (Equations (

27) and (

28)); it follows from

’s scaling and the Gibbs weights

. Use it to cross-check numerical exponents with the

extracted from the heat trace. □

8. Relation to Established Spectral Frameworks

The coherence Hamiltonian developed here, defined on the discrete set of prime numbers via divergence–induced kernels, bears conceptual connections to several established spectral frameworks in mathematical physics and analytic number theory. First, in noncommutative geometry, Connes’ formulation of the adèle class space [

26,

27] proposes a spectral triple

whose Dirac-type operator encodes number-theoretic information, with the Riemann zeta function arising as a spectral zeta of

D. Our construction is not a spectral triple in the strict sense, as it lacks a

-algebraic representation and commutator structure, but it shares the guiding idea that arithmetic data can generate an effective geometry through its spectrum. Where Connes’ framework yields a geometric realization of the adèles and the Frobenius flow, the present model derives an emergent “coherence geometry” directly from prime–pair divergences, emphasizing thermodynamic and entropic observables rather than operator-algebraic ones.

Second, the operator

parallels the Dirac or Laplacian components appearing in spectral triples and in quantum-geometric approaches to spacetime [

28,

29]. In those contexts, the heat trace

captures geometric invariants such as dimension and curvature. In our arithmetic setting, the analogous trace

defines an

effective spectral dimension that quantifies information flow over the primes. The interpretation of

thus generalizes Weyl–type scaling to a non-metric, number-theoretic substrate.

Finally, the conditional correspondence established under the Riemann Hypothesis resonates with the long-standing Hilbert–Pólya heuristic [

30,

31]. The conjecture that the nontrivial zeros of

are eigenvalues of a self-adjoint operator finds an analogue here: the coherence Hamiltonian produces spectra whose local statistics mirror those of the Gaussian Unitary Ensemble and the zeta zeros. Unlike the Hilbert–Pólya search for an explicit “zeta Hamiltonian,” however, the present construction arises directly from the arithmetic correlations among the primes, suggesting that spectral organization and compression may emerge from multiplicative sparsity itself rather than from a hidden geometric operator on a continuous space. Therefore, the coherence Hamiltonian represents a distinct, non-algebraic route to spectral geometry: its “space” is arithmetic, its observables thermodynamic, and its signature the universal subdimensional profile

characteristic of maximal spectral compression.

9. Conclusions

We have developed a spectral framework for arithmetic coherence on the primes. Our analysis distinguishes two operator regimes: the normalized generator , whose bounded spectrum implies as , and the unnormalized generator , whose squared Hamiltonian exhibits a genuine short-time asymptotic. From first principles, we proved (Theorem 2) that under mild regularity assumptions on the divergence kernel, the continuum limit of corresponds to the one-dimensional bi-Laplacian. This yields the asymptotic and an effective spectral dimension , obtained analytically without fitting or external hypotheses.

Numerically, the coherence spectral profile shows a robust activation–peak–decay form across logarithmic, entropic, and fractal-type divergences, returning toward zero at both small and large t for the normalized operator. These results establish an intrinsic arithmetic mechanism for spectral compression and clarify the role of normalization in suppressing small-scale exponents.

The framework thus identifies a principled arithmetic route to , independent of the Riemann Hypothesis, while still resonating with phenomena observed in random matrix theory and zeta-zero statistics. More broadly, it provides a foundation for classifying arithmetic sets by their kernel-induced continuum limits and emergent spectral dimensions.

10. Future Directions

Several lines of investigation remain open. A central challenge is to strengthen the analytic foundations of spectral compression, in particular the origin of the observed scaling of the heat trace and the corresponding spectral dimension . Deriving an exact trace formula for the coherence Hamiltonian, or obtaining asymptotic bounds for its spectrum directly from prime-gap estimates, would place these results on a firmer analytic footing. A complementary direction is to construct coherence operators on other arithmetic sets—such as squarefree numbers, prime powers, or multiplicative sequences—to determine whether comparable subdimensional behavior persists. It may also be fruitful to explore hybrid ensembles that mix arithmetic and geometric divergences, or that incorporate controlled randomness, to test whether dimensional transitions or relaxation toward classical diffusion can occur. Together, these problems outline a broader program: to develop a general theory of spectral coherence on discrete multiplicative structures and to understand how arithmetic sparsity governs the emergence of effective geometry.

Note

| 1 |

A central technical point is the choice of generator: the normalized kernel leads to a bounded spectrum and , whereas the unnormalized (combinatorial) generator admits a genuine small–t exponent in the thermodynamic limit. |

References

- Weyl, H. Über die asymptotische Verteilung der Eigenwerte. Nachrichten von der Königlichen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen, Mathematisch-Physikalische Klasse 1911, pp. 110–117.

- Minakshisundaram, S.; Pleijel, Å. Some properties of the eigenfunctions of the Laplace-operator on Riemannian manifolds. Canadian Journal of Mathematics 1949, 1, 242–256. [CrossRef]

- Gilkey, P.B. Invariance Theory, the Heat Equation and the Atiyah–Singer Index Theorem; CRC Press, 1995.

- Rosenberg, S. The Laplacian on a Riemannian Manifold: An Introduction to Analysis on Manifolds; Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- Connes, A. Noncommutative Geometry; Academic Press, 1994.

- Bény, C.; Veitch, D. Measurement, complexity and thermodynamic cost of quantum processes. New Journal of Physics 2013, 15, 023020.

- Dereziński, J.; Roeck, W.D. Extended weak coupling limit for Pauli–Fierz Hamiltonians. Communications in Mathematical Physics 2013, 318, 667–697.

- Montgomery, H.L. The pair correlation of zeros of the zeta function. Analytic Number Theory, Proceedings of Symposia in Pure Mathematics 1973, 24, 181–193.

- Odlyzko, A.M. On the distribution of spacings between zeros of the zeta function. Mathematics of Computation 1987, 48, 273–308.

- Khrennikov, A. Information Dynamics in Cognitive, Psychological, Social and Anomalous Phenomena; Springer, 2004.

- Mehta, M.L. Random Matrices, 3rd ed.; Elsevier, 2004.

- Edwards, H.M. Riemann’s Zeta Function; Academic Press, 1974.

- Friedlander, J.; Iwaniec, H. Opera de Cribro; Vol. 57, Colloquium Publications, American Mathematical Society, 2005.

- ichi Amari, S.; Nagaoka, H. Methods of Information Geometry; Vol. 191, Translations of Mathematical Monographs, American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, 2007. Originally published by Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Belkin, M.; Niyogi, P. Laplacian Eigenmaps for Dimensionality Reduction and Data Representation. Neural Computation 2003, 15, 1373–1396. [CrossRef]

- Chung, F.R.K. Spectral Graph Theory; Vol. 92, CBMS Regional Conference Series in Mathematics, American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, 1997.

- Lin, J. Divergence Measures Based on the Shannon Entropy. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 1991, 37, 145–151. [CrossRef]

- Hörmander, L. The Spectral Function of an Elliptic Operator. Acta Mathematica 1968, 121, 193–218. [CrossRef]

- Attouch, H.; Buttazzo, G. Variational Convergence for Functions and Operators; Pitman: Boston, 1984.

- Fukushima, M.; Oshima, Y.; Takeda, M. Dirichlet Forms and Symmetric Markov Processes; De Gruyter: Berlin, 2011.

- Kato, T. Perturbation Theory for Linear Operators; Springer: Berlin, 1995.

- Davies, E.B. Heat Kernels and Spectral Theory; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1989.

- Reed, M.; Simon, B. Methods of Modern Mathematical Physics IV: Analysis of Operators; Academic Press: New York, 1978.

- Bingham, N.H.; Goldie, C.M.; Teugels, J.L. Regular Variation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1989.

- Feller, W. An Introduction to Probability Theory and Its Applications, Vol. II; Wiley: New York, 1971.

- Connes, A. Noncommutative Geometry and the Riemann Zeta Function; Springer, 1999. Lecture notes expanding on the adèle class space construction.

- Connes, A.; Marcolli, M. Noncommutative Geometry, Quantum Fields and Motives; American Mathematical Society, 2008.

- Chamseddine, A.H.; Connes, A. The Spectral Action Principle. Communications in Mathematical Physics 1997, 186, 731–750.

- Rennie, A.; Várilly, J.C. Reconstruction of Manifolds in Noncommutative Geometry. Journal of Geometry and Physics 2006, 57, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Edwards, H.M. Riemann’s Zeta Function; Academic Press, 1974.

- Berry, M.V.; Keating, J.P. The Riemann Zeros and Eigenvalue Asymptotics. SIAM Review 1999, 41, 236–266.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).