Submitted:

17 October 2025

Posted:

20 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

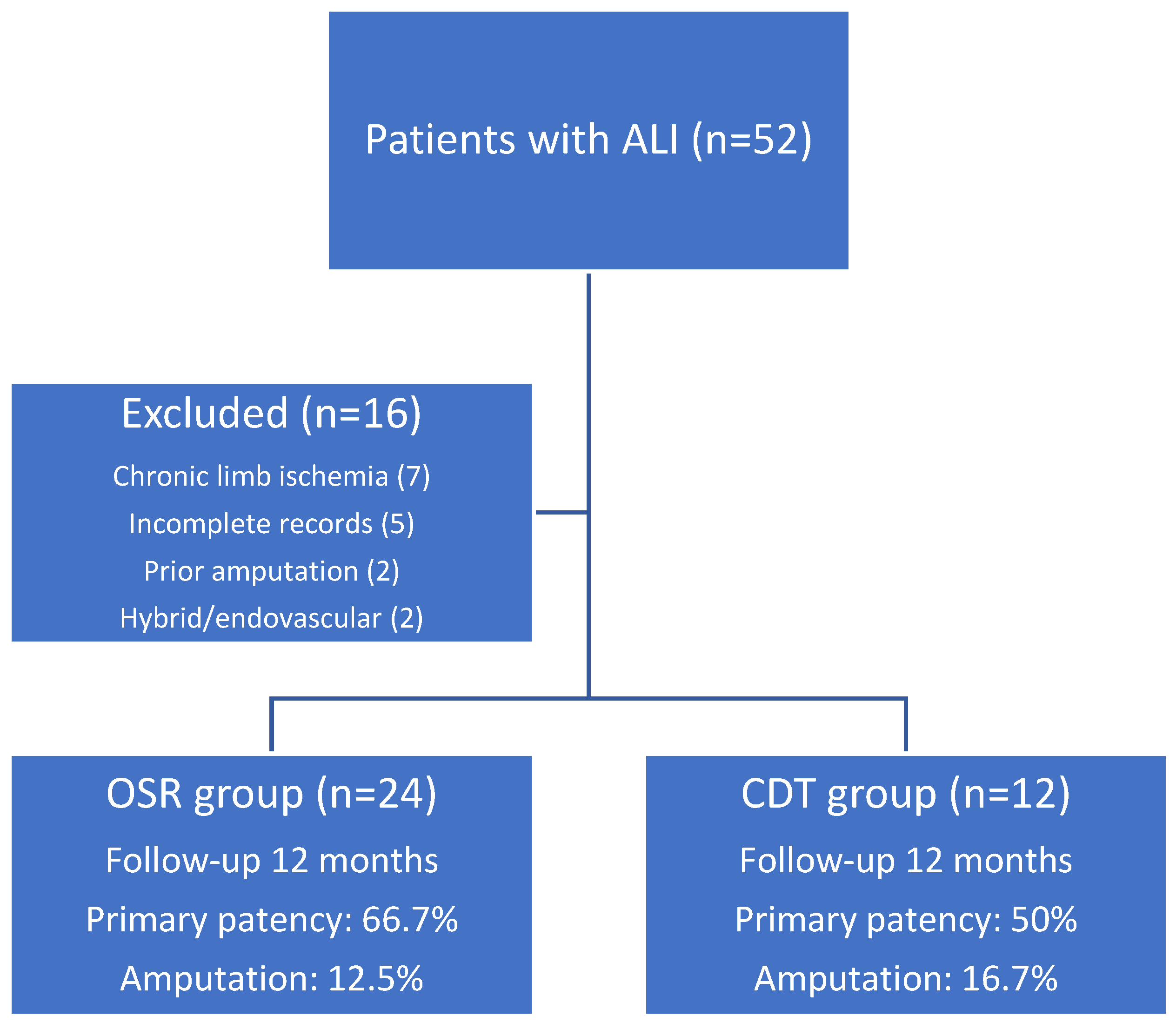

Patient Selection and Inclusion Criteria:

Intervention Details

Outcome Measures

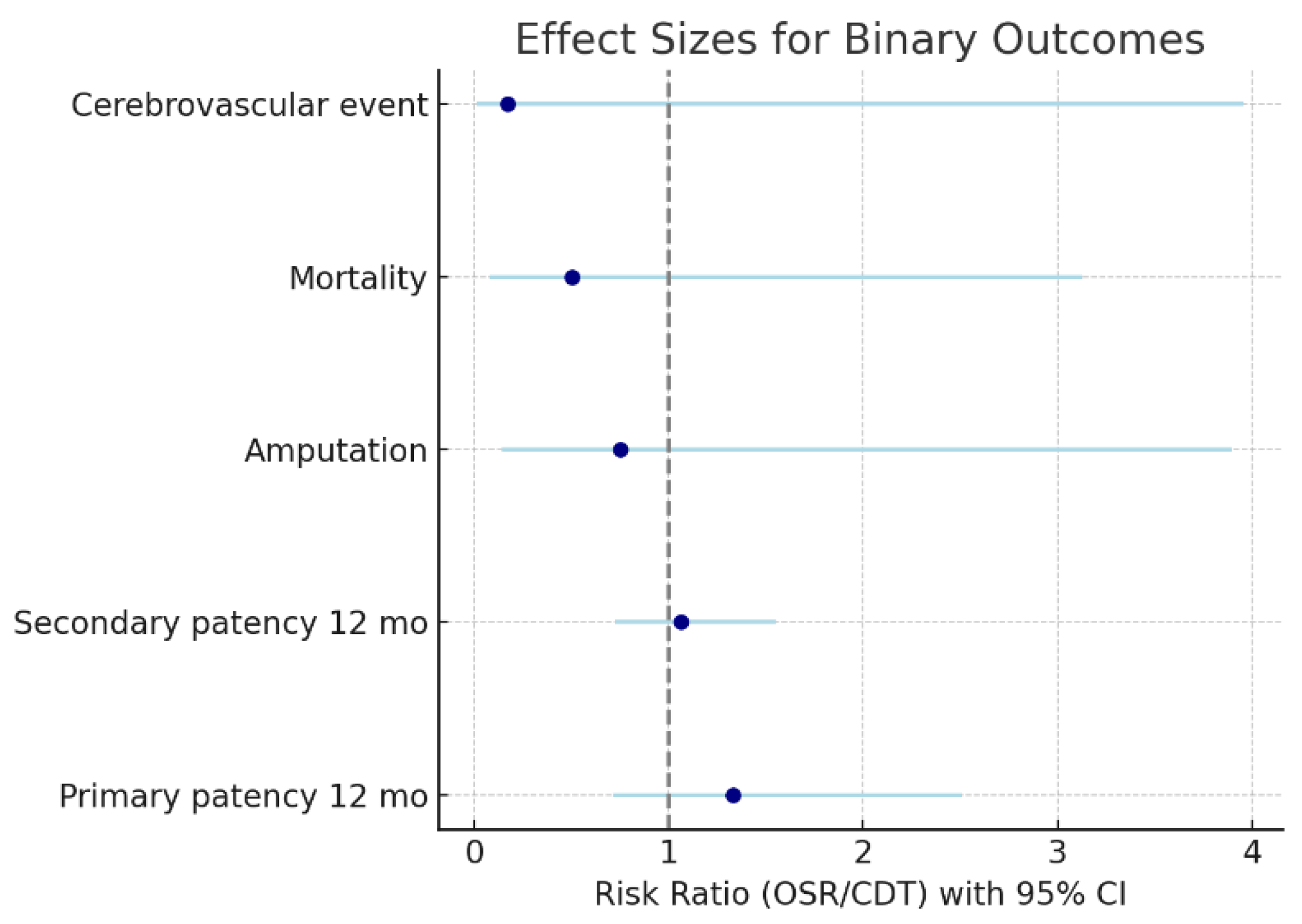

- In-hospital mortality,

- Primary patency, defined as uninterrupted patency of the treated vessel without need for further intervention, and

- Secondary patency, defined as patency restored after a reintervention following an initial occlusion.

- Major amputation rates (above the ankle),

- Incidence of cerebrovascular events (e.g., stroke or transient ischemic attack) during hospitalization, and

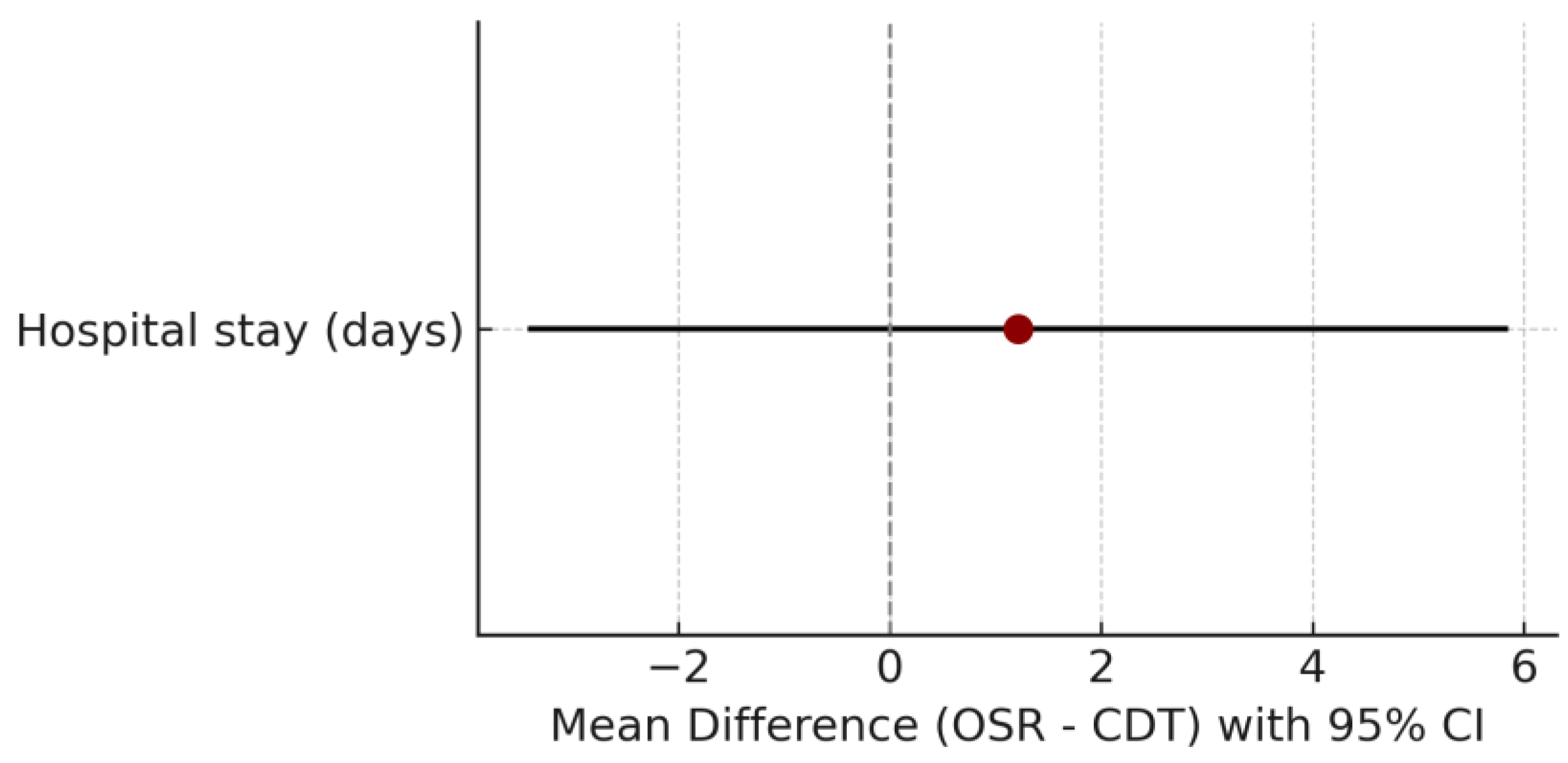

- Length of hospital stay, measured in days from admission to discharge.

Statistical Analysis

Ethical Considerations

Results

Preoperative and Postoperative Clinical Parameters

Comorbidities and Baseline Characteristics

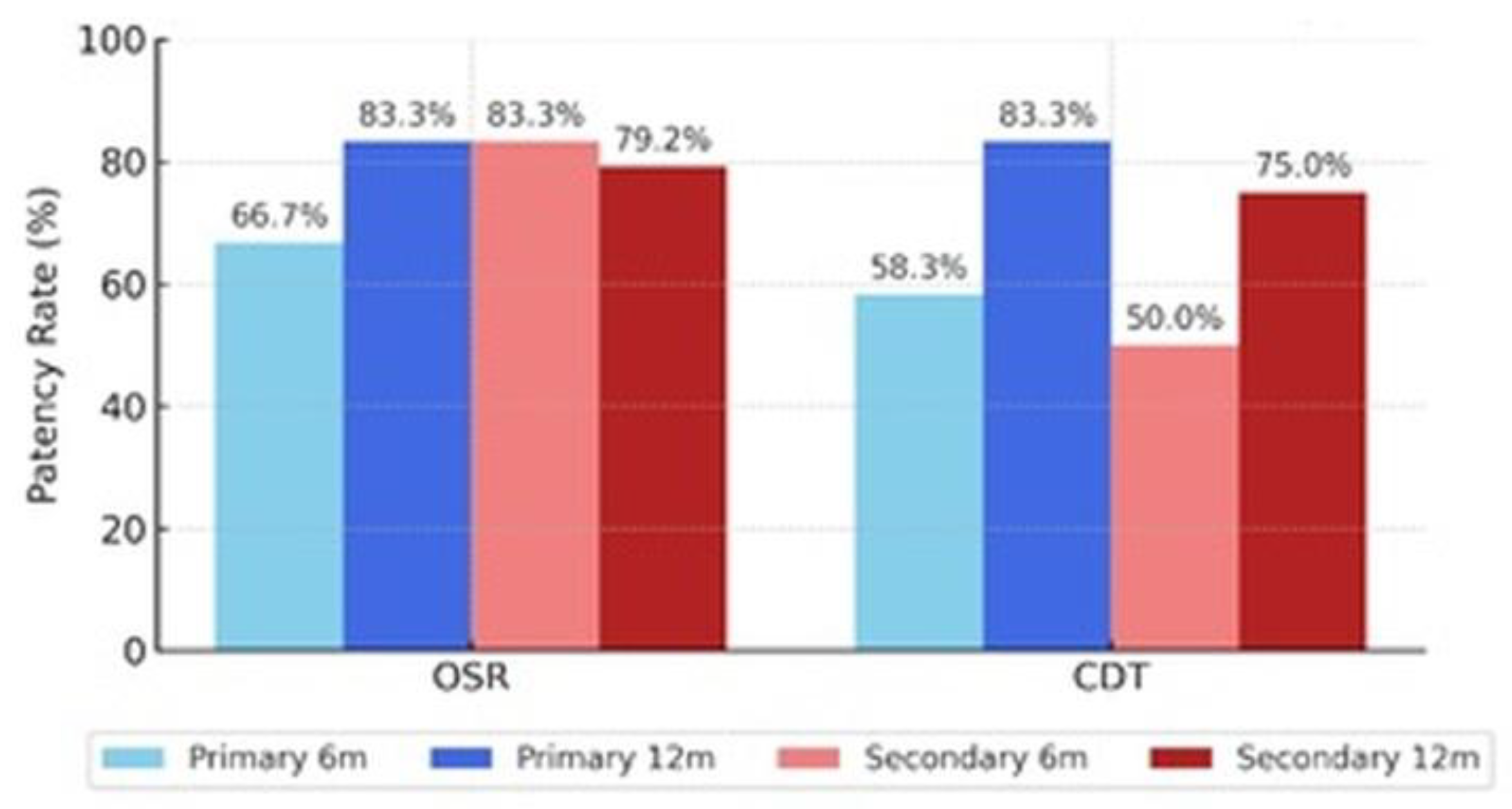

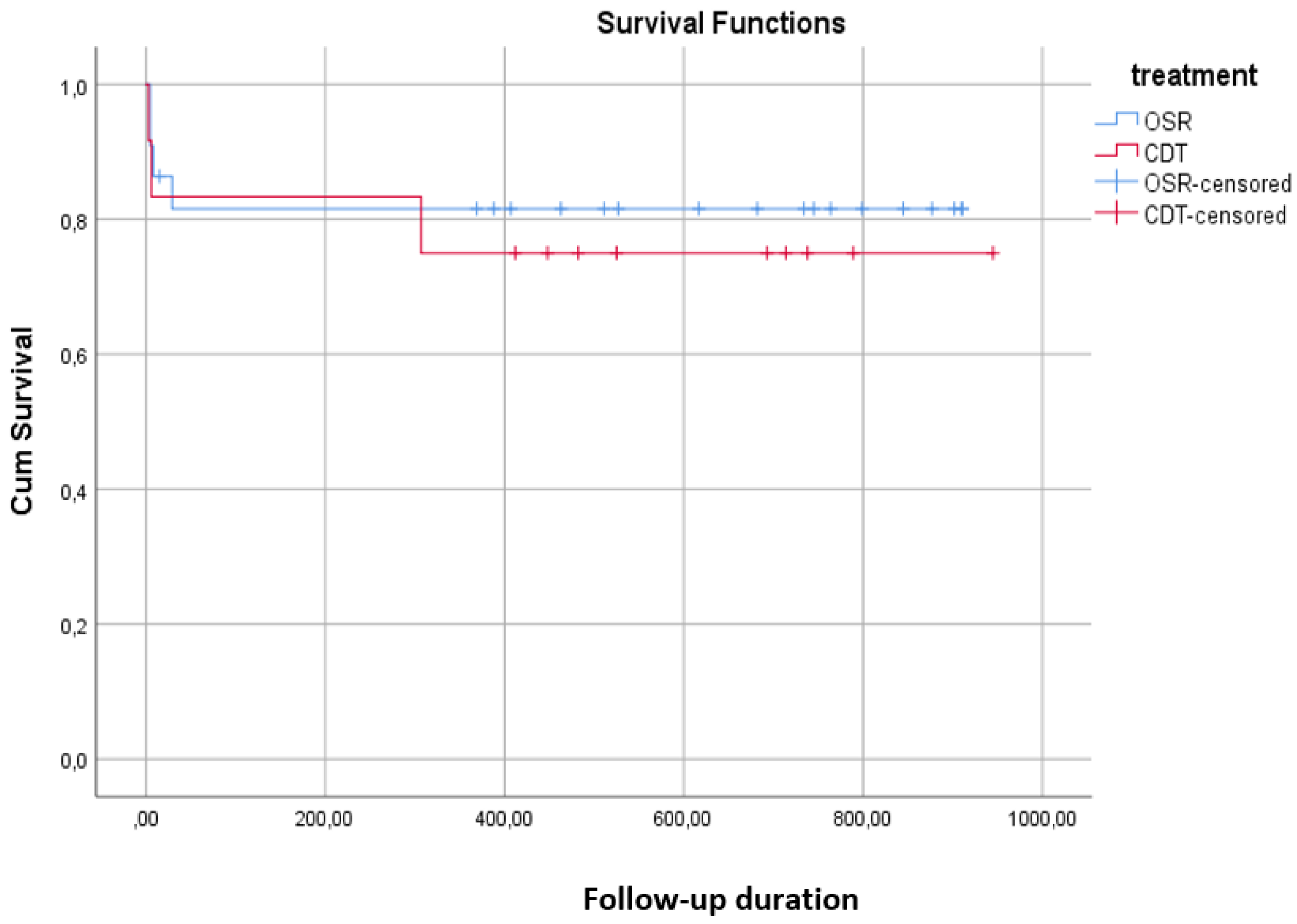

Patency and Outcomes

Comparison Between OSR and CDT Groups

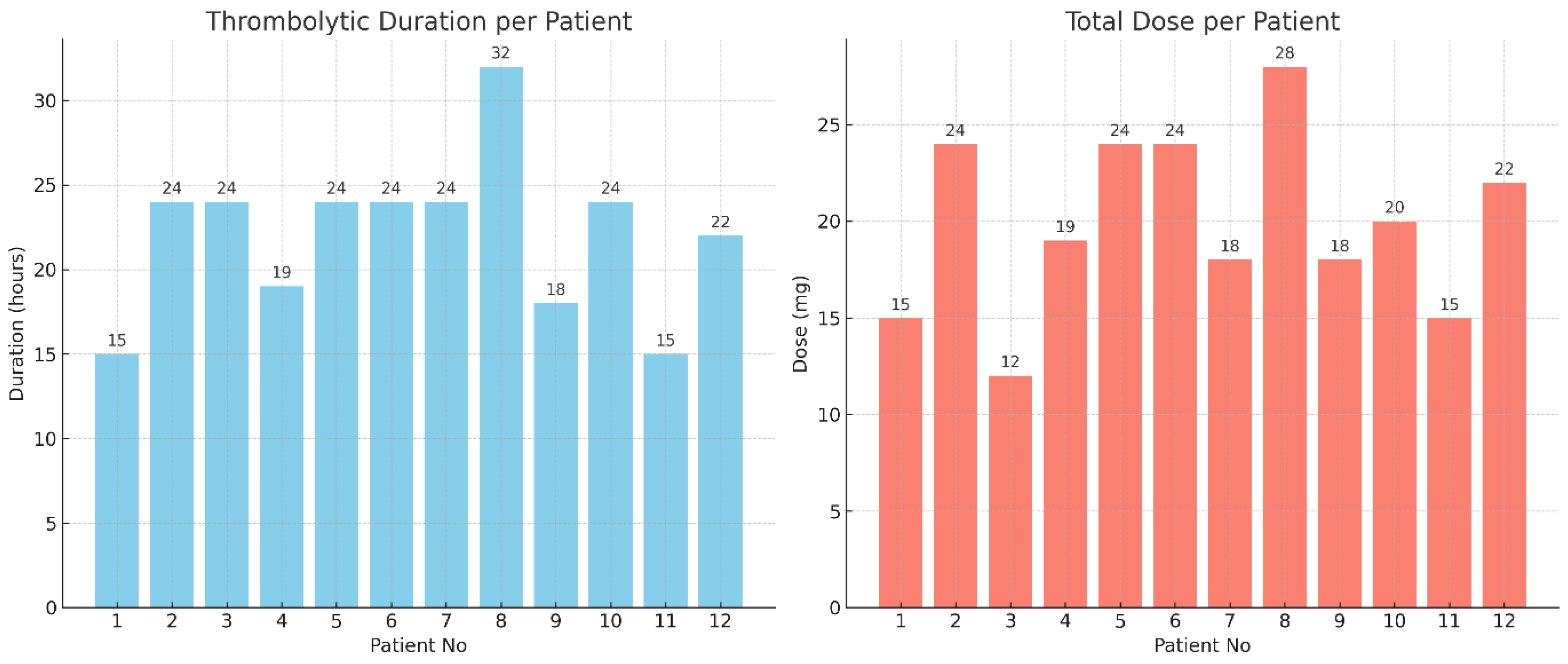

Thrombolytic Infusion

Fibrinogen Levels

Longitudinal Analysis

Arterial Segment Patency Comparison

Discussion

Limitations

Conclusion

References

- Ugwumba, L.; Mannan, F.; El-Sayed, T.; Saratzis, A.; Nandhra, S. A Systematic Review of Modern Endovascular Techniques Compared to Surgery for Acute Limb Ischaemia. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2025, 119, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Stoner, M.C.; Calligaro, K.D.; Chaer, R.A.; Dietzek, A.M.; Farber, A.; Guzman, R.J.; Hamdan, A.D.; Landry, G.J.; Yamaguchi, D.J. Reporting standards of the Society for Vascular Surgery for endovascular treatment of chronic lower extremity peripheral artery disease. J. Vasc. Surg. 2016, 64, e1–e21. [CrossRef]

- Obara H, Matsubara K, Kitagawa Y. Acute Limb Ischemia. Ann Vasc Dis. 2018;11(4):443-8.

- Olinic, D.-M.; Stanek, A.; Tătaru, D.-A.; Homorodean, C.; Olinic, M. Acute Limb Ischemia: An Update on Diagnosis and Management. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1215. [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.; Kwon, T.W. Endovascular Treatment versus Open Surgical Repair for Isolated Iliac Artery Aneurysms. Vasc. Spéc. Int. 2024, 40, 31. [CrossRef]

- Ozawa T, Yanishi K, Fujioka A, Seki T, Zen K, Matoba S. Editor’s Choice - Comparison of Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Acute Lower Limb Ischaemia Undergoing Endovascular Therapy and Open Surgical Revascularisation: A Large Scale Analysis in Japan. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2024;68(6):748-56.

- Morrison, H. Catheter-Directed Thrombolysis for Acute Limb Ischemia. Semin. Interv. Radiol. 2006, 23, 258–269. [CrossRef]

- Konstantinou, N.; Argyriou, A.; Dammer, F.; Bisdas, T.; Chlouverakis, G.; Torsello, G.; Tsilimparis, N.; Stavroulakis, K. Outcomes After Open Surgical, Hybrid, and Endovascular Revascularization for Acute Limb Ischemia. J. Endovasc. Ther. 2023, 32, 1499–1507. [CrossRef]

- Maheta, D.; Desai, D.; Agrawal, S.P.; Dani, A.; Frishman, W.H.; Aronow, W.S.M. Acute Limb Ischemia Management and Complications: From Catheter-Directed Thrombolysis to Long-Term Follow-up. Cardiol. Rev. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Butt, T.; Lehti, L.; Apelqvist, J.; Gottsäter, A.; Acosta, S. Contrast-Associated Acute Kidney Injury in Patients with and without Diabetes Mellitus Undergoing Computed Tomography Angiography and Local Thrombolysis for Acute Lower Limb Ischemia. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2021, 56, 151–157. [CrossRef]

- Lind, B.; Morcos, O.; Ferral, H.; Chen, A.; Aquisto, T.; Lee, S.; Lee, C.J. Endovascular Strategies in the Management of Acute Limb Ischemia. Vasc. Spéc. Int. 2019, 35, 4–9. [CrossRef]

- Björck, M.; Earnshaw, J.J.; Acosta, S.; Gonçalves, F.B.; Cochennec, F.; Debus, E.S.; Hinchliffe, R.; Jongkind, V.; Koelemay, M.J.W.; Menyhei, G.; et al. Editor's Choice – European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2020 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Acute Limb Ischaemia. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2020, 59, 173–218. [CrossRef]

- Kolte D, Kennedy KF, Shishehbor MH, Mamdani ST, Stangenberg L, Hyder ON, et al. Endovascular Versus Surgical Revascularization for Acute Limb Ischemia: A Propensity-Score Matched Analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13(1):e008150.

- Gunes Y, Sincer I, Erdal E. Catheter-directed intra-arterial thrombolysis for lower extremity arterial occlusions. Anatol J Cardiol. 2019;22(2):54-9.

- Veenstra, E.B.; van der Laan, M.J.; Zeebregts, C.J.; de Heide, E.-J.; Kater, M.; Bokkers, R.P. A systematic review and meta-analysis of endovascular and surgical revascularization techniques in acute limb ischemia. J. Vasc. Surg. 2020, 71, 654–668.e3. [CrossRef]

- Hoebink, M.; Steunenberg, T.A.; Roosendaal, L.C.; Wiersema, A.M.; Hamer, H.M.; Yeung, K.K.; Jongkind, V. Ability of Activated Clotting Time Measurements to Monitor Unfractionated Heparin Activity During NonCardiac Arterial Procedures. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2024, 110, 460–468. [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.; Maan, B.S.; El-Sayed, T. 460 Exploring Optimal Antithrombotic Strategies for Acute Limb Ischaemia: A Comprehensive Review. Br. J. Surg. 2024, 111. [CrossRef]

- Durran, A.C.; Watts, C. Current Trends in Heparin Use During Arterial Vascular Interventional Radiology. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2012, 35, 1308–1314. [CrossRef]

- Sista, A.K. Fibrinogen Monitoring during Catheter-Directed Thrombolysis for Pulmonary Embolism: Can It Be Cleaved from Our Practice?. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2020, 31, 1290–1291. [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, C.; Kinney, T.; Quencer, K. Practice Trends of Fibrinogen Monitoring in Thrombolysis. J. Clin. Med. 2018, 7, 111. [CrossRef]

- Dorey, T.; Kong, D.; Lobo, W.; Hanlon, E.; Abramowitz, S.; Turcotte, J.; Jeyabalan, G. Plasma Fibrinogen Change as a Predictor of Major Bleeding During Catheter-Directed Thrombolysis. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2023, 99, 262–271. [CrossRef]

- Ouriel, K.; Veith, F.J.; Sasahara, A.A. A Comparison of Recombinant Urokinase with Vascular Surgery as Initial Treatment for Acute Arterial Occlusion of the Legs. New Engl. J. Med. 1998, 338, 1105–1111. [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.-K.; Su, C.-C.; Hsu, C.-H. Clinical outcomes of surgical embolectomy versus catheter-directed thrombolysis for acute limb ischemia: a nationwide cohort study. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 2021, 53, 517–522. [CrossRef]

- Pascoe, H.M.; Robertson, D. Catheter-directed thrombolysis for acute limb ischaemia: An audit. Australas. Med J. 2014, 7. [CrossRef]

- Results of a prospective randomized trial evaluating surgery versus thrombolysis for ischemia of the lower extremity. The STILE trial. Ann Surg. 1994;220(3):251-66; discussion 66-8.

- Enezate, T.H.; Omran, J.; Mahmud, E.; Patel, M.; Abu-Fadel, M.S.; White, C.J.; Al-Dadah, A.S. Endovascular versus surgical treatment for acute limb ischemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2017, 7, 264–271. [CrossRef]

- Jarosinski, M.C.; Li, K.; Andraska, E.A.; Reitz, K.M.; Liang, N.L.; Chaer, R.; Tzeng, E.; Sridharan, N.D. Comparison of open and endovascular therapy for infrainguinal acute limb ischemia in the era of percutaneous thrombectomy. J. Vasc. Surg. 2025, 82, 952–960.e3. [CrossRef]

- Doelare, S.A.; Oukrich, S.; Ergin, K.; Jongkind, V.; Wiersema, A.M.; Lely, R.J.; Ebben, H.P.; Yeung, K.K.; Hoksbergen, A.W. Major Bleeding During Thrombolytic Therapy for Acute Lower Limb Ischaemia: Value of Laboratory Tests for Clinical Decision Making, 17 Years of Experience. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2022, 65, 398–404. [CrossRef]

- Decker, J.A.; Helmer, M.; Bette, S.; Schwarz, F.; Kroencke, T.J.; Scheurig-Muenkler, C. Comparison and Trends of Endovascular, Surgical and Hybrid Revascularizations and the Influence of Comorbidity in 1 Million Hospitalizations Due to Peripheral Artery Disease in Germany Between 2009 and 2018. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2022, 45, 1472–1482. [CrossRef]

| Variable | OSR | CDT |

| Age | 60.21±11.76 61.00 (32.00 – 78.00) |

67.25±15.66 67.50 (50.00 – 100.00) |

| Gender, K | 7 (29.17) | 2 (16.67) |

| Hypertension | 13 (54.17) | 6 (50.00) |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 14 (58.33) | 6 (50.00) |

| Heart Failure | 5 (20.83) | 3 (25.00) |

| Coronary Artery Disease | 10 (41.67) | 4 (33.33) |

| Stroke | 4 (16.67) | 2 (16.67) |

| Atrial Fibrillation | 8 (33.33) | 7 (58.33) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 14 (58.33) | 7 (58.33) |

| COPD | 4 (16.67) | 2 (16.67) |

| Renal Disease | 4 (16.67) | 4 (33.33) |

| Smoking | 18 (75.00) | 6 (50.00) |

| Previous Vascular Intervention | 13 (54.17) | 4 (33.33) |

| Rutherford Class (I-IIa) | 20 (83.33) | 8 (66.67) |

| Study (Year) | Design / Setting | Population (ALI stage) | Interventions | Primary/Key Outcomes | Main Findings | Notes / Limitations |

| TOPAS (Ouriel et al., 1998, NEJM) | RCT, multicenter | Acute arterial occlusion (mixed) | CDT (urokinase) vs Surgery | Limb salvage, complications | Comparable limb salvage; higher bleeding with thrombolysis | Early protocols; outdated drugs/devices |

| STILE (Comerota et al., 1996, JVS) | Prospective randomized | Acute limb ischemia | CDT vs Operative therapy | Limb salvage, patency, bleeding | Similar limb salvage; increased bleeding in CDT | Older technology; limited generalizability |

| Enezate et al., 2017 (Cardiovasc Diagn Ther) | Meta-analysis | ALI (pooled) | Endovascular vs Surgery | Mortality, amputation, recurrent ischemia (1–12 mo) | No significant differences; trend toward lower short-term amputation with endovascular | Heterogeneity across included studies |

| Veenstra et al., 2020 (EJVES) | Systematic review & meta-analysis | ALI | CDT vs Surgery | Composite clinical endpoints | Comparable endpoints when appropriately selected | Supports individualized treatment selection |

| Yang et al., 2022 (J Thromb Thrombolysis) | Large cohort (Taiwan) | ALI | CDT vs Surgical thrombectomy | In-hospital mortality, amputation | No difference in mortality or amputation | Observational; potential selection bias |

| Kolte et al., 2020 (Circ Cardiovasc Interv) | Propensity-matched analysis | ALI | Endovascular vs Surgical | Limb salvage, mortality | Better in-hospital outcomes for endovascular therapy | Residual confounding possible |

| ESVS Guideline (Björck et al., 2020) | Guideline synthesis | ALI | — | Evidence-based recommendations | Both OSR and CDT valid depending on stage/anatomy | Emphasizes expertise & timely reperfusion |

| Ozawa et al., 2024 (EJVES, Japan) | Large-scale analysis | Acute lower-limb ischemia | Endovascular vs OSR | Clinical outcomes (national dataset) | Comparable results in modern practice | Administrative dataset; limited detail |

| Ugwumba et al., 2025 (Ann Vasc Surg) | Systematic review | Modern endovascular vs Surgery | Contemporary CDT vs OSR | Comparative effectiveness | No consistent superiority; selection matters | Highlights need for standardized protocols |

| Maheta et al., 2024 (Cardiol Rev) | Narrative review | ALI | Spectrum of CDT | Management/complications | Modern CDT feasible with careful monitoring | Bleeding/renal risks remain |

| This study (2019–2023) | Retrospective cohort (single-center) | Rutherford I–IIa (n=36; OSR 24 vs CDT 12) | OSR vs CDT (alteplase; heparin) | 6–12 mo patency, amputation, mortality, LOS | Comparable outcomes; OSR longer LOS; renal function stable | Small sample, non-randomized, no fibrinogen monitoring |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).