1. Introduction

There are more than 200 million people affected by critical threatening limb ischemia (CTLI) worldwide, with a growth rate of 23.5% between 2000 and 2010 due to the aging of the general population and the epidemiological increase in risk factors particularly diabetes mellitus [

1]. The increase in the incidence of CTLI parallels the increase in the incidence of aortic valvular stenosis; the prevalence of this condition is estimated to be 2% in the population aged 65 to 75 years, 3% in the population aged 75 to 85 years, and around 4% in the population over 85 years of age [

2,

3]. Often the two conditions coexist with a reported prevalence of CTLI in patient submitted to Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation (TAVI) up to 34% [

4] associated with a high of in-hospital mortality [

5]. Despite this aspect is not underlined by the recent European Guidelines of management of CTLI [

6]. The purpose of this work was to compare the clinical outcomes between patients with moderate-severe aortic valve stenosis and those with mild or no aortic valve stenosis and with critical lower extremity ischemia undergoing surgical revascularization.

2. Materials and Methods

This is a single-center, retrospective, observational cohort study of prospectively collected patients. All patients who underwent infrainguinal surgical revascularization were identified: post-hoc analysis of the institutional database identified those who underwent surgical lower limb revascularization with femoro supra or sub articular bypass for CTLI from November 2016 to April 2022. All patients provided written informed consent, and each center’s institutional review board approved the present study in accordance with the national policy on the retrospective analysis of anonymized data and the Italian privacy act.

Inclusion criteria were:

- CTLI with Rutherford stage 3-4-5-6 [

6].

- Patients submitted to peripheral bypass starting from the infra-inguinal region (common femoral, superficial femoral, or popliteal artery) and landing supra- or sub-articular (popliteal artery or tibial vessels).

Exclusion criteria were:

-Patients treated with endovascular revascularization and those submit ted to TAVI before surgical revascularization or during follow-up.

Each patient underwent preoperative cardiologic examination at the cardiac lab at our Institution. Transthoracic echocardiogram was performed by cardiologists with more than 10 years of experience.

Patients were treated according to the European guidelines taking into account the Global Limb Anatomic Staging System (GLASS classification) [

6]. The great saphenous vein, when available, was the material of choice for revascularization; in case of its unavailability, prosthetic material (PTFE or Dacron) with interposition of vein Linton patch at the distal anastomosis was performed. At the end of the intervention, completion angiography or duplex ultrasound was routinely achieved. Postoperative antithrombotic treatment consisted of single or double antiplatelet treatment or oral anticoagulation; it was determined on the basis of the surgeon’s preference as well as according to the patient’s comorbidities and risk factors, or it was driven by some particular technical aspects performed during the intervention. Clinical and instrumental follow-up with echocolordoppler was performed at 1 - 3 - 6 - 12 months and annually thereafter. At each follow-up visit, functional status and degree of disability was assessed and compared with the preoperative situation. Patients with trophic lesions, gangrene, or amputation were followed at a dedicated outpatient vulnology clinic, performed by professional nurses and supervised by medical staff, until the subjects’ complete recovery, death, or major amputation surgery.

The extent of aortic valve stenosis was assessed according to the criteria of the European Society of Cardiology [

7] [

Table 1]. Patients were divided into two groups, group A those carrying moderate-severe aortic valve stenosis (AVA-cm2 < or = 1.5 cm2) and group B carrying mild or no stenosis (AVA-cm 2 >1.5 cm2). All subjects were classified on the basis of functional status and degree of disability according to the classification proposed by the American Society of Vascular Surgery (SVS) [

8] and consulted in

Table 2.

The total days of each patient’s hospital stay related to the hospitalization performed for bypass was taken into account. Perioperative complications, considered temporally to have occurred within the first 30 days after surgery, were divided according to the type of event into systemic (cardiac, respiratory, renal, neurological, thrombo-embolic, allergic) or bypass-related (including peri-anastomotic stenosis, thrombosis, pseudoaneurysms, arteriovenous fistulae, infection, and need for major amputation due to acute bypass occlusion and non-revascularization of the limb). In the follow-up after 30 days, only late bypass-related complications (including peri-anastomotic stenosis evidenced on postoperative echocolorDoppler follow-up, thrombosis of the same, pseudoaneurysms, arteriovenous fistulas, or infections) were considered.

Rates of major limb amputation and incidence of major cardiovascular events, defined as occurrence of cerebral stroke, myocardial infarction, and sudden cardiac death, were calculated, with calculation of days elapsed from the date of surgery.

Mortality was investigated by consulting demographic information afferent to the Lombardy Region SISS service or by telephone contact with family members. Among the patients who died, it was specified whether death was from cardiovascular or non-cardiovascular causes. In case of doubt or inability to find this information, the cause of death was attributed to "other non-cardiovascular cause”.

Primary outcomes were major amputation rate and mortality rate between the two groups. Secondary outcomes included the rate of major cardiovascular events, late bypass-related complications (including peri-anastomotic stenosis evidenced on postoperative echocolor-Doppler follow-up, thrombosis of the same, pseudoaneurysms, arteriovenous fistulas, or infections) and change in "preoperative functional status".

Clinical data were recorded prospectively and tabulated in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, Wash) database; statistical analysis was performed by means of SPSS 24.0 for Windows (IBM SPSS Inc., Chicago, Ill). Categorical variables were presented using frequencies and percentages, continuous variables were presented with mean 6 standard deviation or median and ranges, on the basis of data distribution. Continuous variables were analyzed with the c2 test and Fisher’s exact test, when necessary. Independent samples Student’s t-test was used for continuous variables, and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to evaluate the difference in ankle-brachial index measurement before and after intervention. Associations that yielded a P value of less than .20 on univariate screen were then included in a forward Cox regression analysis. The strength of the association of variables with PVGI was estimated by calculating the hazard ratio and 95% confidence intervals (Cis; significance criteria of 0.25 for entry and 0.05 for removal). Evaluation of cut-offs for the variable AVA - fx - cm2, in terms of predictive of outcome outcomes, was calculated by ROC curves. All reported P values were 2two sided; a P value of less than .05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Profile, Anatomic Characteristics and Surgical Details

A total of 158 patients were analyzed of whom the majority were male (111, 70.2%), 25 (15.8%) of them belonged to group A and 133 (84.2%) afferents to group B. Patients in group A were found to be significantly older than those in group B (median age 78 [65.81] vs 74 [76.83], p value = 0.005). Demographic characteristics and comorbidities of the population can be consulted in

Table 3. Clinical profile and surgical details are listed on

Table 4.

3.2. Bypass Related Outcomes

Median time in days of hospitalization was 7 for group A (IQR 5.75,9.00) and 6 for group B (IQR 5.00,9.00) p=0.467. Mean follow-up was 1178 days, (SD 991 days). In total we observed 51 (32.2%) bypass related complications within 30 days from intervention. A total of 27 (17%) major amputations were performed at follow-up. Graft related complications are listed in

Table 5. Among patients who had at least 4 complications, those in group A were significantly greater than patients in group B (p=0.010). In general, in patients in group A, complications beyond the second were found in greater numbers than in group B.

The presence of moderate-severe aortic valve stenosis does not appear to be associated with major amputation (OR 0.76, p=0.638). The only variable with statistical significance major was the time elapsed (in days) between the date of revascularization surgery and the date of major amputation: 449 days in group A vs 100 in group B (p=0.016). Other variables associated with increased risk of amputation are highlighted in

Table 6.

Table 5.

graft related complications and amputation rate. .

Table 5.

graft related complications and amputation rate. .

| Variable |

level |

Group B |

Group A |

p-value |

Bypass-related complications within

30 days n (%) |

No |

91 (68.4) |

16 (64.0) |

0.841

|

| Yes |

42 (31.6) |

9 (36.0) |

| Patency, n (%) |

No

|

41 (31.5) |

9 (36.0) |

0.839

|

| Yes |

89 (68.5) |

16 (64.0) |

| Restenosis, n (%) |

No |

87 (97.8) |

16 (100.0) |

1.000

|

| Yes |

2 (2.2) |

0 (0.0) |

| First complication after 30 days n (%) |

No |

77 (57.9) |

12 (48.0) |

0.487 |

| Yes |

56 (42.1) |

13 (52.0) |

| Second complication after 30 days n (%) |

No |

112 (84.2) |

21 (84.0) |

1.000 |

| Yes |

21 (15.8) |

4 (16.0) |

| Third complication after 30 days n (%) |

No |

124 (93.2) |

21 (84.0) |

0.252 |

| Yes |

9 (6.8) |

4 (16.0) |

| Fourth complication after 30 days n (%) |

No |

132 (99.2) |

22 (88.0) |

0.010 |

| Yes |

1 (0.8) |

3 (12.0) |

Mean number of complication after

30 days [SD] |

|

0.65 [0.89] |

0.96 (1.34) |

0.429 |

| Major amputation (%) |

No |

111 (83.5) |

20 (80.0) |

0.895

|

| Yes |

22 (16.5) |

5 (20.0) |

| Time between intervention and major amputation in days (median, [IQR]) |

|

100.00 [64.50, 283.25] |

449.00 [432.00, 1144.00] |

0.016 |

Table 6.

Univariate logistic model for “Major Amputation”, AVA (Aortic Valve Area), MI (Myocardial Infarction).

Table 6.

Univariate logistic model for “Major Amputation”, AVA (Aortic Valve Area), MI (Myocardial Infarction).

| |

Univariate logistic model “Major Amputation” |

| Predictors |

Odds Ratio |

OR 95%CI |

pvalue |

| AVA |

0.76 |

(0.27, 2.49) |

0.638 |

| Age |

1.02 |

(0.97, 1.07) |

0.420 |

|

Complications within 30 days [yes vs no]

|

5.83 |

(2.36, 14.57) |

<0.001 |

|

Functional status [Impaired, but able vs not impaired]

|

2.42 |

(0.87, 25.67) |

0.109 |

|

[Needs some assistance vs not impaired]

|

10.37 |

(1.72, 45.82) |

0.016 |

|

[Requiring total assistance vs not impaired]

|

6.67 |

(1.91, 79.39) |

0.010 |

|

Graft related complications [yes vsno]

|

2.74 |

(1.17, 6.45) |

0.020 |

| Bypass lenght |

7.72 |

(1.53, 140.68) |

0.049 |

|

Cardiac status [recent MI vs asymptomatic]

|

2.65 |

(1.14, 6.26) |

0.024 |

3.3. Clinical Outcomes

Clinical outcomes in terms of cardiovascular and other cause mortality, postoperative functional recovery, and incidence of postoperative major cardiovascular events are listed in

Table 7.

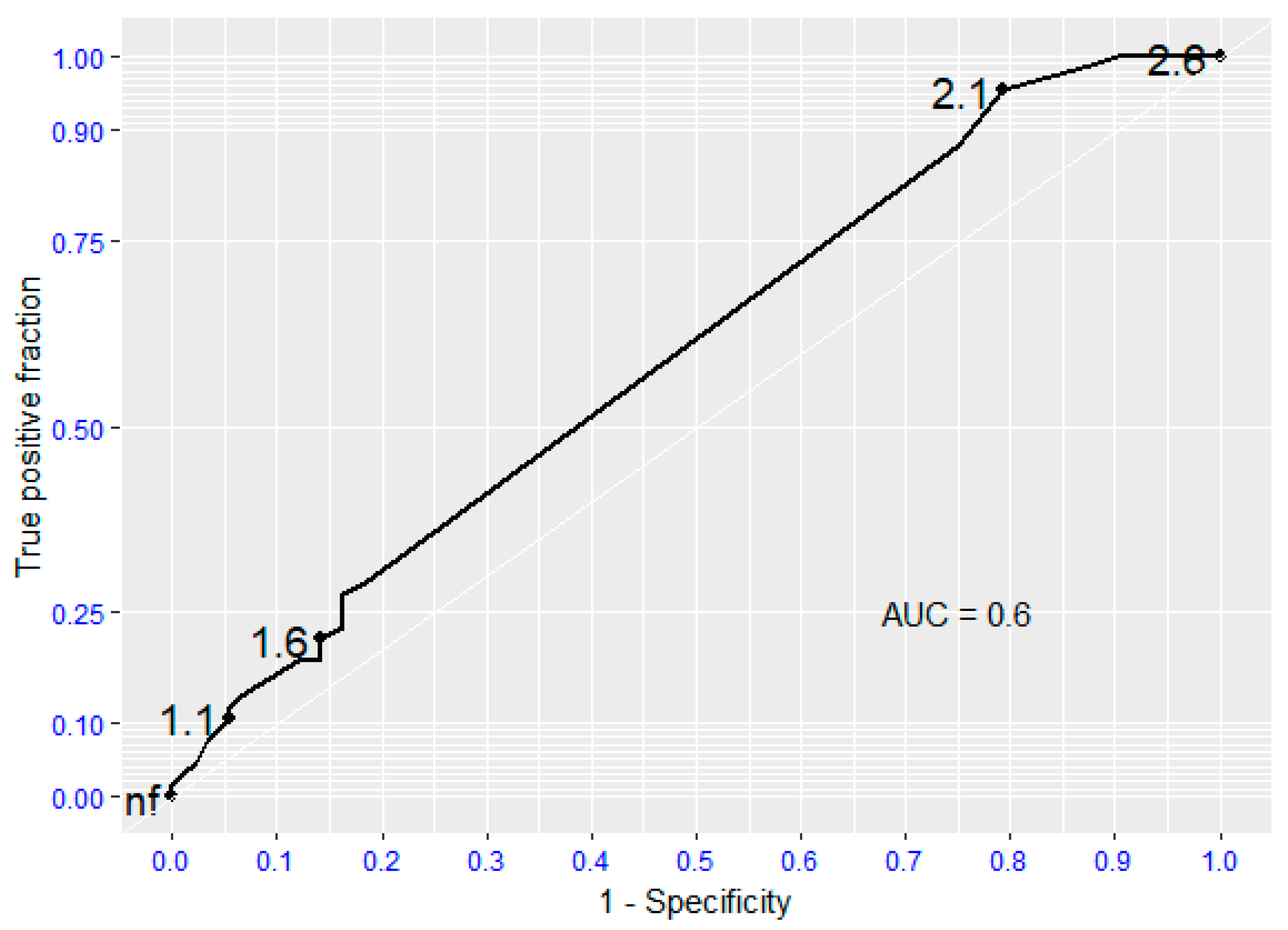

ROC analysis documented that the presence of moderate-to-severe aortic valvular stenosis is not a reliable predictor of death or survival in patients undergoing surgical lower extremity revascularization (AUC 0.6; 95%CI: 0.52,0.68). The absence of aortic valve stenosis is a statistically significant predictor of survival (AUC 0.8 - 0.95). (Fig. 1).

Significant predictors of overall mortality were age (OR=1.07, p<0.001), systemic complication within 30 days (OR 3.83, p=0.002) and pre-operative functional status (OR 8.57, p<0.001).

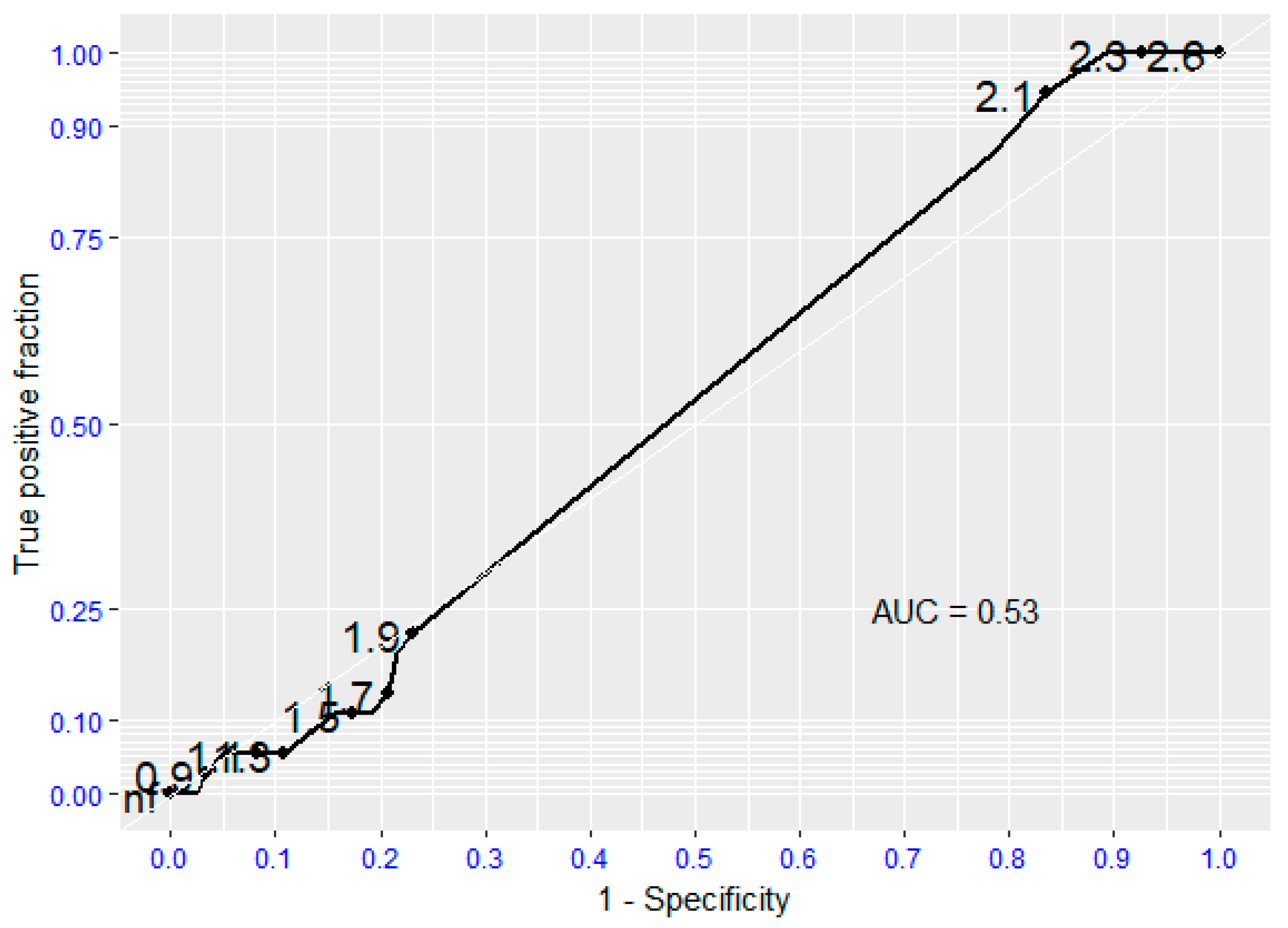

Regarding survival following Major Adverse Event (myocardial infarction, ICTUS, sudden cardiac death), there is no evidence that the moderate/severe aortic valve stenosis is a predictive risk factor for it (p=0.934), the absence of aortic valvular stenosis was predictive of the absence of such events, with sensitivity and specificity values for survival following major cardiovascular complications of 0.95 and 0.8, respectively (Fig. 2).

Significant predictors of cardiovascular mortality were age (OR 1.05, p=0.028), systemic complication within 30 days (OR 3.72, p=0.002) and pre-operative functional status (OR 10.37 p<0.001).

The presence of moderate-severe aortic valve stenosis does not appear to be associated with changes in preoperative functional status (OR 0.45, p=0.111). Variables associated with changes in pre-operative functional status can be consulted in

Table 8.

Table 7.

clinically outcomes between the two groups. MAE: Major Adverse Event, MI: Myocardial Infarcion.

Table 7.

clinically outcomes between the two groups. MAE: Major Adverse Event, MI: Myocardial Infarcion.

| Variable |

level |

Group B |

Group A |

p-value |

| Major Adverse Event (MAE) (%) |

No |

79 (59.4) |

13 (52.0) |

0.142 |

| Cardiovascular event (MI/stroke/Sudden Cardiac death) |

33 (24.8) |

4 (16.0) |

| Death for other causes or unknown |

21 (15.8) |

8 (32.0) |

| Death, n (%) |

No |

79 (59.4) |

13 (52.0) |

0.640

|

| Yes |

33 (24.8) |

12 (48.0) |

| Cardiovascular death, n (%) |

No |

100 (75.2) |

21 (84.0) |

0.486

|

| Yes |

33 (24.8) |

4 (16.0) |

| Times between intervention and any MAE in days (median [IQR]) |

|

936 [238, 1478] |

792.50 [159.25, 1431.50] |

0.673 |

| Time between intervention and death in days (mean; median[IQR]) |

|

961; 744.50 [244.50, 1475.25] |

893; 559 [165.25, 1431.50] |

0.630 |

| Time between intervention and cardiovascular death in days (mean; median [IQR]) |

|

822; 341 [150, 1467] |

358; 181 [86.75, 452.25] |

0.221 |

| Postoperative functional status, n (%) |

No impairment |

58 (43.9) |

7 (29.2) |

0.157 |

| |

Impaired, but able to carry out ADL without assistance |

20 (15.2) |

7 (29.2) |

| Needs some assistance to carry out ADL or ambulatory assistance |

23 (17.4) |

2 (8.3) |

| |

Requiring total assistance for ADL or nonambulatory |

31 (23.5) |

8 (33.3) |

Table 8.

Univariate logistic model for variation of functional status, AVA (Aortic Valve Area), MI (Myocardial Infarction).

Table 8.

Univariate logistic model for variation of functional status, AVA (Aortic Valve Area), MI (Myocardial Infarction).

| |

Univariate logistic model for variation of functional status |

| Predictors |

Odds Ratio |

OR 95%CI |

pvalue |

| AVA |

0.45 |

(0.16, 1.16) |

0.111 |

| Age |

1.08 |

(1.04, 1.13) |

<0.001 |

|

Complications within 30 days [yes vs no]

|

3.52 |

(1.43, 10.04) |

0.010 |

|

Functional status [Impaired, but able vs not impaired]

|

3.02 |

(1.28, 7.49) |

0.013 |

|

[Needs some assistance vs not impaired]

|

10.62 |

(6.09, 51.17) |

<0.001 |

|

[Requiring total assistance vs not impaired]

|

40.72 |

(6.98, 782.41) |

<0.001 |

|

Graft related complications [yes vsno]

|

1.82 |

(0.91, 3.77) |

0.095 |

| Bypass lenght |

2.52 |

(1.13, 5.82) |

0.026 |

|

Cardiac status [recent MI vs asymptomatic]

|

2.12 |

(1.07, 4.30) |

0.033 |

| Rutherford scale |

2.24 |

(1.38, 3.77) |

0.014 |

3.4. Figures, Tables and Schemes

Figure 1.

Receiving Operating Characteristic (ROC curve) regarding global mortality. AUC (Area Under the Curve).

Figure 1.

Receiving Operating Characteristic (ROC curve) regarding global mortality. AUC (Area Under the Curve).

Figure 2.

Receiving Operating Characteristic (ROC curve) regarding Major Adverse Events (MAE). AUC (Area Under the Curve).

Figure 2.

Receiving Operating Characteristic (ROC curve) regarding Major Adverse Events (MAE). AUC (Area Under the Curve).

4. Discussion

Despite the higher rate of mortality and complications in patients undergoing TAVI and suffering from CTLI than in nonarterial patients is well documented [

9,

10], there is lack of evidence in literature of clinical outcomes of patients submitted to surgical revascularization for CTLI and suffering from severe aortic valve stenosis.

One of the reasons could be explained by the increasing application of endovascular revascularization techniques burdened by a low perioperative risk that does not require cardiologic pre-operatory investigations [

11]. In addition, echocardiogram is not always performed, due to the rapidly evolving disease in these categories of patients that need a treatment as quickly as possible. Secondly, with the advent of TAVI, which has made it possible to extend the therapeutic indication even to patients with severe comorbidities considered inoperable with traditional technique, the encounter of patients with untreated severe aortic valve stenosis is increasingly rare [

12].

As expected, the only significant difference in demographic data between the two groups was related to age; patients with moderate-severe aortic valvular stenosis were significantly older than subject’s afferent to the comparison group; these findings are in line with other data reported in the literature [

13,

14]. Age and severe aortic valve stenosis were also associated, albeit non-significantly, with a greater of ischemic foot impairment (Rutherford grade VI) than the control group.

The main finding of this study was that moderate-severe aortic valve stenosis was not significantly associated with a higher rate of amputation or worse survival than patients free of valve disease. Previous works did not found difference in term of limb survival after surgical revascularization between octogenarians and non-octogenarians’ patients [

15,

16,

17]. Considering that patients with moderate-severe aortic valve stenosis are older we can assume that our findings are in line with others. However, even if not significant, patients in group A tend to have a higher rate of bypass complications than the control group. Many factors impact the outcome of lower extremity bypass. It has long been established that veins are the ideal conduit for lower extremity revascularization. With aging, venous compliance decreases especially in the lower extremity which can make vein graft in the elderly more susceptible to early stenosis and graft failure [

18].

However interestingly we found that the time elapsed in days, between the date of revascularization and the date of major amputation was significant longer in the group with moderate-severe stenosis than the group with mild or no stenosis (499 days vs. 100 days, p= 0.016). This apparently counter-intuitive finding could be explained as a bias arising from the comparison of two numerically inhomogeneous groups of patients.

Regarding mortality data, among patients who died of cardiovascular causes, those with moderate/severe aortic valve stenosis had a shorter postoperative survival time in days than patients without significant valve stenosis. This finding confirms what is already evident in literature, that patients with high-grade aortic valve disease suffered from higher mortality rate than the ones without valve stenosis [

19].

In the group of patients with moderate-severe stenosis, the percentage of those who died from non-cardiovascular causes was higher (32.0 % vs. 15.8 %). Among the causes for this, in addition to advanced age and major comorbidities, the advent of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in the early 2020s that caused many to die from COVID19-related respiratory causes may have played a role in these patients [

20].

A very interesting aspect worthy of further study is the change in functional status after revascularization surgery. Although not significant, full recovery of autonomy in the performance of daily activities was observed in a higher percentage within the cohort of patients with mild or absent stenosis, 43.9 %, compared with 29.2 % in the cohort of moderate-severe aortic valve stenosis. Our work confirmed data from that of Taylor et Al who showed that among the most important predictors of failure to improve functional outcome appeared to be "impaired ambulatory ability" at presentation and the presence of dementia [

21].

This study has several limitations, first the retrospective and single design of the work, therefore the possibility of biased analysis cannot be excluded. Secondarily due to limited data it was not possible to calculate ROC curve, we performed logistic model were to verify which variables were statistically associated with major amputation and variation of functional status. Lastly, many of our patients were lost to follow-up.

5. Conclusions

The results obtained from this research showed that patients submitted to surgical peripheral revascularization for CLTI and concomitantly affected by moderate-to-severe aortic valve stenosis have similar outcomes in term of amputation and mortality rate than patients without aortic valve stenosis.

However, this cohort of patients is overall older, frail, and has temporally more "aggressive" cardiovascular mortality than the control group.

This study showed that surgical treatment of CTLI, in addition to bringing, a significant reduction or complete disappearance of pain at rest and ensuring healing of trophic lesions and/or minor amputation site, is associated with improved postoperative functional status in patients without aortic valve disease. Further large-scale prospective studies are needed to confirm these data.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Author contributions

Study design: L. A, A.P, M.A.P, R.B.; Data collection: R.B., L.L., M.A.P., A.P., F.C., G.L, S.T. and L.A.; Data analysis: A.P, L.A, G.P.; Writing: L. A and R.B.; Critical revision and final approval: L. A., GP., L.L., M.A.P., A.P., F.C., G.L., S.T. and R.B.; Overall responsibility: L.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the analysis.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Fowkes FG, Rudan D, Rudan I, Aboyans V, Denenberg JO, McDermott MM, et al. Comparison of global estimates of prevalence and risk factors for peripheral artery disease in 2000 and 2010: a systematic review and analysis. Lancet 2013; 382:1329-40. [CrossRef]

- Manning WJ (October 2013). "Asymptomatic aortic stenosis in the elderly: a clinical review". JAMA. 310 (14): 1490-7.

- Stewart BF, Siscovick D, Lind BK, et al. (March 1997). "Clinical factors associated with calcific aortic valve disease. Cardiovascular Health Study." Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 29 (3): 630-4. [CrossRef]

- Holmes DR Jr, Brennan JM, Rumsfeld JS, Dai D, O’Brien SM, Vemulapalli S, Edwards FH, Carroll J, Shahian D, Grover F, Tuzcu EM, Peterson ED, Brindis RG, Mack MJ; STS/ACC TVT Registry. Clinical outcomes at 1 year following transcatheter aortic valve replacement. JAMA. 2015 Mar 10;313(10):1019-28. [CrossRef]

- Malyar NM, Kaier K, Freisinger E, Lüders F, Kaleschke G, Baumgartner H, Frankenstein L, Reinecke H, Reinöhl J. Prevalence and impact of critical limb ischaemia on in-hospital outcome in transcatheter aortic valve implantation in Germany. EuroIntervention. 2017 Dec 20;13(11):1281-1287. [CrossRef]

- Conte MS, Bradbury AW, Kolh P, White JV, Dick F, Fitridge R, Mills JL, Ricco JB, Suresh KR, Murad MH; GVG Writing Group. Global vascular guidelines on the management of chronic limb-threatening ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2019 Jun;69(6S):3S-125S.e40. Epub 2019 May 28. Erratum in: J Vasc Surg. 2019 Aug;70(2):662. [CrossRef]

- Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F, Milojevic M, Baldus S, Bauersachs J, Capodanno D, Conradi L, De Bonis M, De Paulis R, Delgado V, Freemantle N, Gilard M, Haugaa KH, Jeppsson A, Jüni P, Pierard L, Prendergast BD, Sádaba JR, Tribouilloy C, Wojakowski W; ESC/EACTS Scientific Document Group. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease: Developed by the Task Force for the management of valvular heart disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2022 Jun;75(6):524. [CrossRef]

- Stoner MC, Calligaro KD, Chaer RA, Dietzek AM, Farber A, Guzman RJ, Hamdan AD, Landry GJ, Yamaguchi DJ, on behalf of the Society for Vascular Surgery. Reporting standards of the Society for Vascular Surgery for endovascular treatment of chronic lower extremity peripheral artery disease. J Vasc Surg 2016; 64: 1-21.

- Ueshima D, Barioli A, Nai Fovino L, D’Amico G, Fabris T, Brener SJ, Tarantini G. The impact of pre-existing peripheral artery disease on transcatheter aortic valve implantation outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2020 Apr 1;95(5):993-1000. [CrossRef]

- Shah KB, Elzeneini M, Neal D, Kamisetty S, Winchester D, Shah SK. Chronic Limb-Threatening Ischemia Is Associated with Higher Mortality and Limb Revascularization After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. Am J Cardiol. 2023 Nov 15; 207:202-205. [CrossRef]

- Romiti M, Albers M, Brochado-Neto FC, Durazzo AE, Pereira CA, De Luccia N. Meta-analysis of infrapopliteal angioplasty for chronic critical limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg 2008; 47(5): 975-81. [CrossRef]

- Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients with Valvular Heart Disease: executive summary; a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice. Circulation. 2014;129(23): 2440-2492.

- Manning WJ (October 2013). "Asymptomatic aortic stenosis in the elderly: a clinical review". JAMA. 310 (14): 1490-7.

- Stewart BF, Siscovick D, Lind BK, et al. (March 1997). "Clinical factors associated with calcific aortic valve disease. Cardiovascular Health Study." Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 29 (3): 630-4. [CrossRef]

- Uhl C, Hock C, Ayx I, Zorger N, Steinbauer M, Töpel I. Tibial and peroneal bypasses in octogenarians and nonoctogenarians with critical limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2016 Jun;63(6):1555-62. [CrossRef]

- Myers R, Mushtaq B, Taylor N, Rashid H, Pineda DM. Limb salvage in octogenarians with critical limb ischemia after lower extremity bypass surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2023 Jul;78(1):217-222.

- Morisaki K, Matsuda D, Guntani A, Aoyagi T, Kinoshita G, Yoshino S, Inoue K, Honma K, Yamaoka T, Mii S, Yoshizumi T. Treatment Outcomes in Octogenarians with Chronic Limb-Threatening Ischemia after Infrainguinal Bypass Surgery or Endovascular Therapy. Ann Vasc Surg. 2024 Sep;106:312-320. [CrossRef]

- Molnár AÁ, Nádasy GL, Dörnyei G, Patai BB, Delfavero J, Fülöp GÁ, Kirkpatrick AC, Ungvári Z, Merkely B. The aging venous system: from varicosities to vascular cognitive impairment. Geroscience. 2021 Dec;43(6):2761-2784. [CrossRef]

- Kvaslerud AB, Santic K, Hussain AI, Auensen A, Fiane A, Skulstad H, Aaberge L, Gullestad L, Broch K. Outcomes in asymptomatic, severe aortic stenosis. PLoS One. 2021 Apr 7;16(4):e0249610.

- Bellosta R, Piffaretti G, Bonardelli S, Castelli P, Chiesa R, Frigerio D, Lanza G, Pirrelli S, Rossi G, Trimarchi S; Lombardy Covid-19 Vascular Study Group. Regional Survey in Lombardy, Northern Italy, on Vascular Surgery Intervention Outcomes During The COVID-19 Pandemic. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2021 Apr;61(4):688-697. [CrossRef]

- Taylor SM, Kalbaugh CA, Blackhurst DW, Cass AL, Trent EA, Langan EM 3rd, Youkey JR. Determinants of functional outcome after revascularization for critical limb ischemia: an analysis of 1000 consecutive vascular interventions. J Vasc Surg. 2006 Oct;44(4):747-55; discussion 755-6.

Table 1.

classification of Aortic valve stenosis (AS).

Table 1.

classification of Aortic valve stenosis (AS).

| Echo parameters |

Sclerosis |

Mild AS |

Moderate AS |

Severe AS |

| Peak velocity, m/s |

<2.5 |

2.5 – 3 |

3-4 |

>4 |

| Mean gradient, mmhg |

Normal |

<20 |

20-40 |

40 |

| AVA, cm2 |

Normal |

≥ 1.5 |

1-1.5 |

< 1 |

Table 2.

pre-operatory functional status and disabilities, ADL: Activities of Daily Living.

Table 2.

pre-operatory functional status and disabilities, ADL: Activities of Daily Living.

| Pre-operatory functional status |

|

| 0 |

No impairment |

| 1 |

Impaired, but able to carry out ADL without assistance

|

| 2 |

Needs some assistance to carry out ADL or ambulatory assistance |

| 3 |

Requiring total assistance for ADL or nonambulatory |

Table 3.

Demographic data and comorbidities, BMI: Body Mass Index, COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, MI: Myocardial Infarction, EF: Cardiac Ejection Fraction, ADL: Activities of Daily Living.

Table 3.

Demographic data and comorbidities, BMI: Body Mass Index, COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, MI: Myocardial Infarction, EF: Cardiac Ejection Fraction, ADL: Activities of Daily Living.

| Variable |

level |

Group B |

Group A |

p-value |

| |

|

N= 133 |

N=25 |

|

| Sex (%) |

Female |

39 (29.3) |

8 (32.0) |

0.976

|

| |

Male |

94 (70.7) |

17 (68.0) |

| Age (median, [IQR]) |

|

74.00 [65.00, 81.00] |

78.00 [76.00, 83.00] |

0.005 |

| Vmax (median [IQR]) |

|

1.36 [1.17, 1.65] |

2.89 [2.60, 3.19] |

<0.001 |

| Mean Gp (median [IQR]) |

|

3.80 [2.90, 5.60] |

18.42 [13.16, 24.04] |

<0.001 |

| Weight, kg (median [IQR]) |

|

70.00 [58.00, 80.00] |

70.00 [55.00, 78.00] |

0.911 |

| Height, m (median [IQR]) |

|

1.69 [1.62, 1.75] |

1.67 [1.64, 1.70] |

0.561 |

| BMI (median [IQR]) |

|

24.69 [22.22, 26.67] |

24.80 [22.40, 27.66] |

0.971 |

| Smoking habits (%) |

No – past |

92 (69.2) |

19 (76.0) |

0.655

|

| |

yes |

41 (30.8) |

6 (24.0) |

| Diabetes (%) |

No |

73 (54.9) |

11 (44.0) |

0.434

|

| |

yes |

60 (45.1) |

14 (56.0) |

| Hypertension (%) |

No |

19 (14.3) |

2 (8.0) |

0.597

|

| |

Yes |

114 (85.7) |

23 (92.0) |

| Renal function impairment (%) |

No impairment or mild |

116 (87.2) |

24 (96.0) |

0.355

|

| Severe or pre-terminal |

17 (12.8) |

1 (4.0) |

| Dislipidemia (%) |

No |

34 (25.6) |

6 (24.0) |

1.000

|

| Yes |

99 (74.4) |

19 (76.0) |

| Cardiac status (%) |

Asymptomatic or previous MI ( > 6 months) or silent |

86 (64.7) |

15 (60.0) |

0.827 |

| Recent MI (<6 mesi), arytmia, angina, reduction of EF |

47 (35.3) |

10 (40.0) |

| COPD (%) |

No |

61 (45.9) |

11 (44.0) |

1.000

|

| Yes |

72 (54.1) |

14 (56.0) |

| Stroke (%) |

No |

115 (86.5) |

23 (92.0) |

0.663

|

| Yes |

18 (13.5) |

2 (8.0) |

| Pre-operatory functional status (%) |

No impairment |

39 (29.3) |

4 (16.0) |

0.479

|

| Impaired, but able to carry out ADL without assistance |

44 (33.1) |

8 (32.0) |

| Needs some assistance to carry out ADL or ambulatory assistance |

38 (28.6) |

10 (40.0) |

| Requiring total assistance for ADL or nonambulatory |

12 (9.0) |

3 (12.0) |

Table 4.

clinical presentation, type of intervention and graft material.

Table 4.

clinical presentation, type of intervention and graft material.

| Variable |

level |

Group B |

Group A |

p-value |

| Side n (%) |

Right |

67 (50.4) |

8 (32.0) |

0.142

|

| Left |

66 (49.6) |

17 (68.0) |

| Rutherford Scale (%) |

3 - Severe claudication |

10 (7.5) |

2 (8.0) |

0.157

|

| 4 - Ischemic rest pain |

34 (25.6) |

4 (16.0) |

| 5 - Minor tissue lost |

83 (62.4) |

15 (60.0) |

| 6 - Major tissue lost |

6 (4.5) |

4 (16.0) |

| Level of rivascularization n (%) |

Above the knee |

26 (19.5) |

5 (20.0) |

1.000

|

| Below the knee |

107 (80.5) |

20 (80.0) |

| Graft material, prosthesis n (%) |

No |

47 (35.3) |

9 (36.0) |

1.000

|

| Yes |

86 (64.7) |

16 (64.0) |

| Graft material, great saphenous vein n (%) |

No |

64 (48.1) |

10 (40.0) |

0.597

|

| Yes |

69 (51.9) |

15 (60.0) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).