Submitted:

17 October 2025

Posted:

20 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Background

2.2. Methodology

- A review of the orogenic gold deposit model with a focus on deposits of this type within the study area and broader Yilgarn Craton.

- A solid geology (lithostructural) interpretation based on all available geological, structural and geophysical information.

- Mineral potential modeling (MPM), adopting a multi-technique approach that entailed the use of continuous as well as data- and knowledge-driven mathematical techniques and, thereby, facilitated the cross-validation and comparison of the resulting prospectivity maps [31].

- The identification of gold exploration targets.

2.3. Supporting Data

2.4. Processing and Interpreation of Geophysical and Remote Sensing Data

2.4.1. Geophysical Data and Processing

- Gravity data, which respond to variations in rock density and reflect density contrasts in the subsurface. As such, gravity surveys are effectively a ‘depth penetrative’ method.

- Magnetic data, which respond to variations in rock magnetism, are mostly controlled by magnetic susceptibility. Like gravity data, magnetic data reflect subsurface contrasts.

- Radiometric data, which respond to surface variations in naturally occurring gamma radiation, mostly originating from radioactive isotopes of potassium (K), thorium (Th) and uranium (U).

- Edges (i.e., maximum gradient curves), which represent traces of physical property boundaries across gravity or magnetic data grids, arising from structural breaks such as faults or shear zones, or lithological contacts.

- Ridges (i.e., surface maximum/peak curves), which correspond to ridgeline curves across gravity and magnetic data grids. Gravity ridges, for example, reflect peak gravity responses. In granite-greenstone terrain, gravity ridges often coincide with the thickest parts of dense, mafic rock units and, thus, work well in terms of mapping structurally thickened mafic-ultramafic rocks in the central parts of inverted greenstone basins.

- Valleys (i.e., curves of surface minimum), which correspond to valley line curves across gravity or magnetic data grids. Magnetic valleys, for example, often coincide with faults or fault corridors along which primary magnetite was partly, or mostly, destroyed due to fluid-rock interaction.

2.4.2. Remote Sensing Data and Processing

2.4.3. Solid Geology Interpretation

2.5. Mineral Systems Concept

- Source processes that extract the essential mineral deposit components (i.e., melts and/or fluids, metals, and ligands) from their crustal or mantle sources;

- Transport processes that drive the transfer of the essential components from source to trap regions via melts and/or fluids;

- Trap processes that focus melt and/or fluid flow into physically and/or chemically responsive, deposit-scale sites;

- Deposition processes that drive the efficient extraction of metals from melts and/or fluids passing through the traps;

- Preservation processes that act to preserve the accumulated metals through time.

2.6. Fry Analysis

2.7. Mineral Potential Modeling (MPM)

- Genetic model stage: Recognition the critical geological processes responsible for the formation of the targeted deposit type to establish a conceptual deposit model.

- Targeting model stage: Translation of the genetic model into a targeting model in which the critical ore-forming processes are expressed through mappable targeting criteria (also referred to as spatial proxies, predictor maps, predictors, or targeting elements).

- Mathematical model stage: Assignment of weights to integrate the diverse predictor maps utilizing mathematical algorithms.

- Target identification and prioritized stage: Mapping and prioritization of the most prospective areas.

3. Geology

3.1. Eastern Goldfields Superterrane (EGST), Yilgarn Craton

3.1.1. Overview

3.1.2. Geology and Structure

- A basal volcanic package dominated by ~2720 to 2690 Ma komatiite and basalt;

- A sedimentary package dominated by ~2690 to 2670 Ma deep marine siliciclastic and volcaniclastic sedimentary rocks; and

- High-Ca granites: Constitute the most abundant group of granites (∼60% of all EGST granitoids) and occur both within and external to greenstone belts. They are typically granite, granodiorite or trondhjemite in composition. Emplacement ages fall into three clusters at ∼2800 Ma, 2740 to 2650 Ma and, most commonly, 2685 to 2655 Ma.

- High field strength element (HFSE)-enriched granites: Make up 5 to 10% of all Yilgarn Craton granites. They are typically granite or, to a lesser degree, granodiorite in composition and occur mostly internal or marginal to greenstone belts. Emplacement ages fall into two clusters at >2720 to 2665 Ma and, most commonly, 2700 to 2680 Ma.

- Mafic granites: Make up 5 to 10% of all Yilgarn Craton granites. They are typically granite, granodiorite, tonalite, trondhjemite or diorite in composition and occur mostly internal or marginal to greenstone belts. A common spatial association with gold mineralization has been noted. Their emplacement ages fall into a relatively narrow time bracket from >2720 to 2650 Ma, although younger examples likely exist.

- Low-Ca granites: Are the second most abundant granite group by volume (∼20%) and mostly external to greenstone belts. Compositionally, the granites of this group are typically granitic or granodioritic. Their emplacement ages fall into a relatively narrow time bracket from 2655 to 2630 Ma. Low-Ca granites are considered products of partial melting of high-Ca granite source rocks.

- Syenitic granites: Are the least abundant granite group (<5%) and typically internal or marginal to greenstone belts. Granites of this group are syenite or quartz syenite in composition. A spatial association with gold mineralization has been noted. Emplacement ages cluster at 2650 Ma and 2655 to 2645 Ma.

3.1.3. Deformation History

- D1: ENE-WSW-directed extension at ~2720 to 2670 Ma marked by rifting and greenstone deposition.

- D2: ENE-WSW-directed shortening at ~2670 to 2665 Ma marked by the termination of volcanic activity and generation of NNW-SSE-trending upright folds and N-S-to NE-SW-striking dextral strike-slip and reverse faults.

- D3: NE-SW-directed extension and extensional doming (i.e., core complex formation) at ~2665 to 2655 Ma marked by deep crustal exhumation and the formation of late basins with the late basin sequences constituting the first record of the deposition of granite detritus in the EGST.

- D4: ENE-WSW-directed shortening at ~2655 to 2650 Ma (D4a) marked by the tightening of earlier formed fold structures, WSW-directed thrusting along NNW-SSW-striking faults as well as the generation of NNW-SSE-trending upright folds and reverse faults; and WNW-ESE-directed shortening at (D4b) marked by reactivation of and sinistral transpression along earlier formed NNW-SSE-striking faults and generation of ENE-WSW-striking thrust faults, which recorded transport to the NW and SE.

- D5: NE-SW-directed shortening at ~2650 to 2635 Ma marked by dextral strike-slip movement along N-S- to NNE-SSW-striking faults and thrusting along NNW-SSE- to NW-SE-striking faults.

- D6: Low-strain vertical shortening and horizontal extension at <2630 Ma marked by the development of crenulations.

3.1.4. Metamorphic History

- Ma: Early-formed, low-P/high-T upper-amphibolite to granulite facies assemblages of the Ma metamorphic event are rare. They are restricted to magmatic arc-related, ~2730 to 2810 Ma greenstone sequences of the western Burtville Terrane and HFSE granites and ~2675 to 2715 Ma greenstones of similar affinity in the Gindalbie Domain of the Kurnalpi Terrane.

- M1: This metamorphic event, which occurred at ~2750 to 2700 Ma, produced high-P/moderate-T assemblages preserved in relatively narrow, upper-amphibolite grade domains along major, crustal-scale fault zones. The structural setting, depth of burial and rapid exhumation of these rocks are consistent with partial burial of buoyant magmatic arcs, or terranes, during magmatic arc accretion events in subduction-like environments.

- M2: This ~2680 to 2670 Ma, low-P/moderate-T metamorphic event produced a contact metamorphic pattern linked to the emplacement of large volumes of high-Ca granite melt into the upper crust, which were generated by partial melting of a down-going slab subducted beneath the Kalgoorlie and Kurnalpi terranes. The M2 event coincided in time with the cessation of volcanism and D2 crustal shortening.

- M3: The M3 metamorphic event is believed to have been caused by lithospheric extension at ~2665 to 2650 Ma, linked to the cessation of subduction with sag on the previously subducted plate causing slab rollback and extension of the overriding plate. The M3 event coincided in time with the D3, that is metamorphic core complex formation.

- M4: Low-P/high-T metamorphism at ~2650 to 2610 Ma was likely triggered by delamination of the lower crust, resulting in mantle upwelling and the arrival of a thermal anomaly in the upper crust associated with widespread and voluminous low-Ca granite magmatism.

3.1.5. Geodynamic Implications

3.2. Kalgoorlie-Kurnalpi Rift

3.3. Kalgoorlie Terrane

3.4. Kurnalpi Terrane

4. Gold Mineralization

4.1. Gold Endowment

4.2. Gold Deposit Styles

4.3. Gold Depositional Events

- D3 (~2665 to 2655 Ma): Formation of EGST crustal architecture during a period of NE-SW-directed extension and associated metamorphic core complex formation. Most of the large crustal-penetrating fault systems had already been established at this time, connecting the upper crust to a metasomatized mantle as indicated by the first arrival of mafic and syenitic granites. The mantle link would have resulted in the addition of significant heat into the base of the crust and aided in mantle-to-crust metal transfer. A prominent D3 deposit example in the study area is Gwalia (>8.2 Moz Au).

- D4 (~2655 to 2650 Ma): The extensional crustal architecture established during D3 was inverted during D4, a brittle-ductile deformation event that can be divided into an initial phase of ENE-WSW-directed shortening (D4a) followed by a switch in contraction to WNW-ESE-directed shortening (D4b). Deformation was accompanied by a switch from high- to low-Ca granite magmatism due to crustal melting. Most importantly, D4 coincided with the most significant gold mineralization event in the EGST. In particular, strike-slip deformation and reactivation of pre-existing structural heterogeneities during D4b served as a highly effective fluid focusing mechanism. The most prominent D4 deposit example is the Golden Mile (>65 Moz Au), located ~35 km S of the study area.

- D5 (~2650 to 2635 Ma): A further switch in the stress field triggered NE-SW-directed shortening associated with dextral strike-slip, thrusting and low-Ca granite melt emplacement. Gold mineralization was controlled by brittle structures. A prominent D5 deposit example is Sunrise Dam (>10.3 Moz Au), located ~20 km E of the study area.

5. Data Integration and Interpretation

5.1. Insights from the Enhancement Filtering of Geophysical and Remote Sensing Data

- Belt-parallel gravity ridges serve as proxies for greenstone basin centers or zones of thicker mafic-ultramafic material along greenstone keels and root zones (Figure 4). As demonstrated by a confidential gravity data enhancement filter for the entire Australian continent, a large proportion of Yilgarn gold (and nickel) deposits have proximity, association and abundance relationships with gravity ridges. A similar relationship can be observed within the study area where gold occurrences, other than those wholly contained within intrusive rocks, have proximity, association and abundance relationships with gravity ridges observable at multiple scales (Figure 5).

- Gravity edges, on the other hand, represent discontinuities such as fault or shear zones, or significant lithological boundaries. In the case of the study area, the Thunderbox, King of the Hills, Gwalia and Ulysses gold deposits all sit along the same curvilinear belt-parallel gravity edge, which can be traced along strike for >230 km and appears to continue north beyond the study area boundary. Interestingly, this gravity linear only coincides with the Perseverance-Ockerbury-McClure fault system in places whilst there is strong spatial coincidence between it and the basement granite-greenstone contact (Figure 6). Similar, semi-parallel linear features in the study area may represent attractive targets for first pass exploration.

5.2. Solid Geology (Lithostructural) Interpretation

- Late basin sequences: Polymictic to oligomictic conglomerate and sandstone.

- Sedimentary siliciclastic sequences: Felsic volcaniclastic sandstone, siltstone ± conglomerate, chemical sedimentary and interleaved felsic volcanic rock.

- Felsic to intermediate volcanic sequences: Rhyolite to rhyodacite, andesite, felsic volcaniclastic and siliciclastic rock ± felsic and mafic volcanic rock, interleaved with coeval basalt and dolerite.

- Mafic to ultramafic volcanic sequences: Basalt, komatiite, peridotite, serpentinite, mafic to ultramafic schist (chlorite schist, tremolite schist, fuchsite-andalusite schist) ± coeval dolerite and gabbro.

6. Targeting Model

7. Mineral Potential Modeling (MPM)

7.1. Statistical Evaluation of Predictor Maps

7.2. Continuously-Weighted Mineral Potential Models

7.2.1. Continuous Fuzzy Gamma Technique

7.2.2. Geometric Average Technique

7.2.3. Improved Index Overlay Technique

7.3. Knowledge-Driven BWM-SAW Technique

7.4. Data-Driven Random Forest (RF) Algorithm

8. Discussion

8.1. Geology and Structure

8.2. Geophysics and Remote Sensing

8.3. Mineral Potential Modeling (MPM)

8.3.1. Predictor Map Performance

8.3.2. Multi-Technique Approach

8.3.3. Predictor Map Sensitivity

8.3.4. Using Fractal Thresholding for Target Generation

8.4. Targeting

8.4.1. Role of MPM as a Targeting Tool

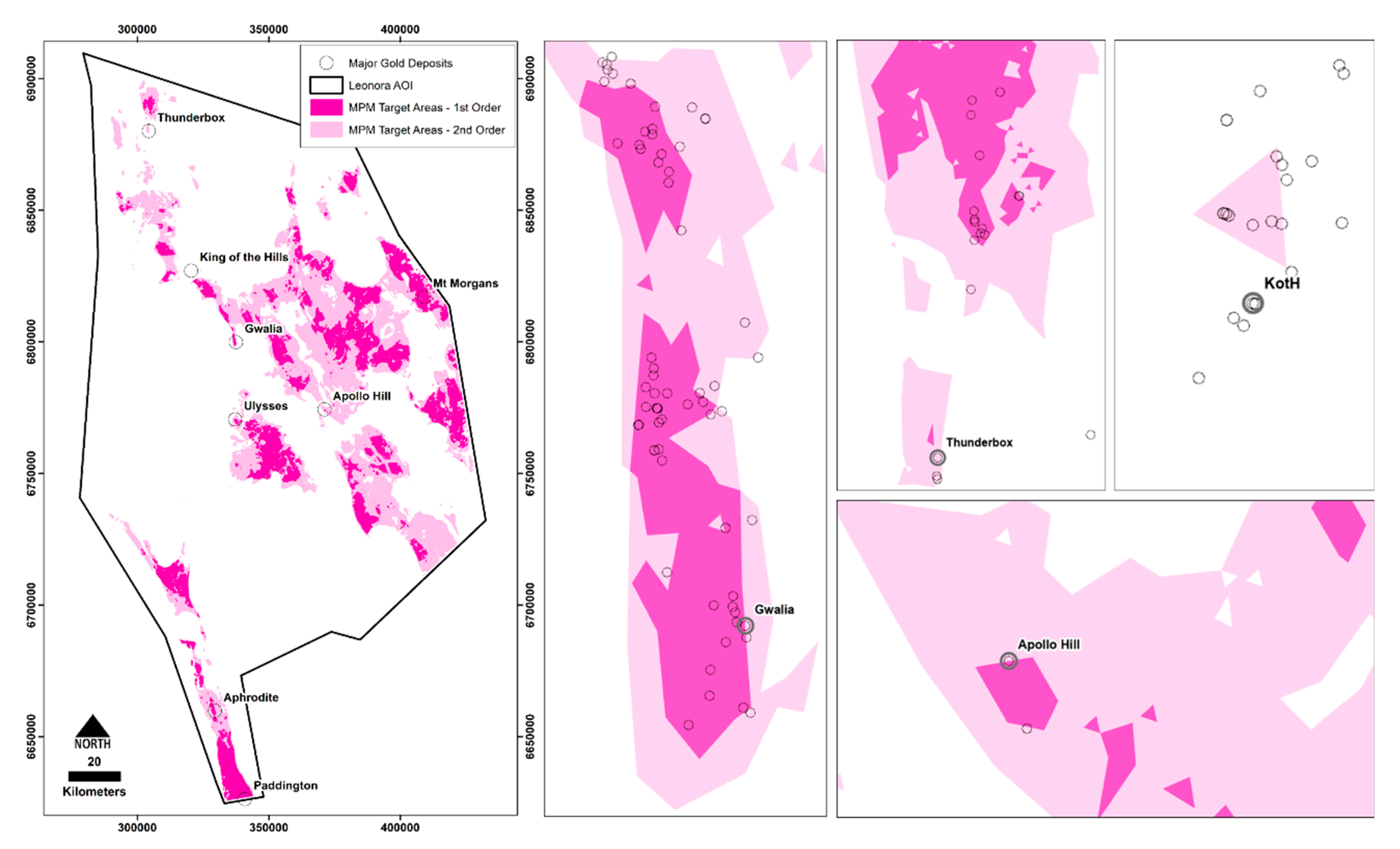

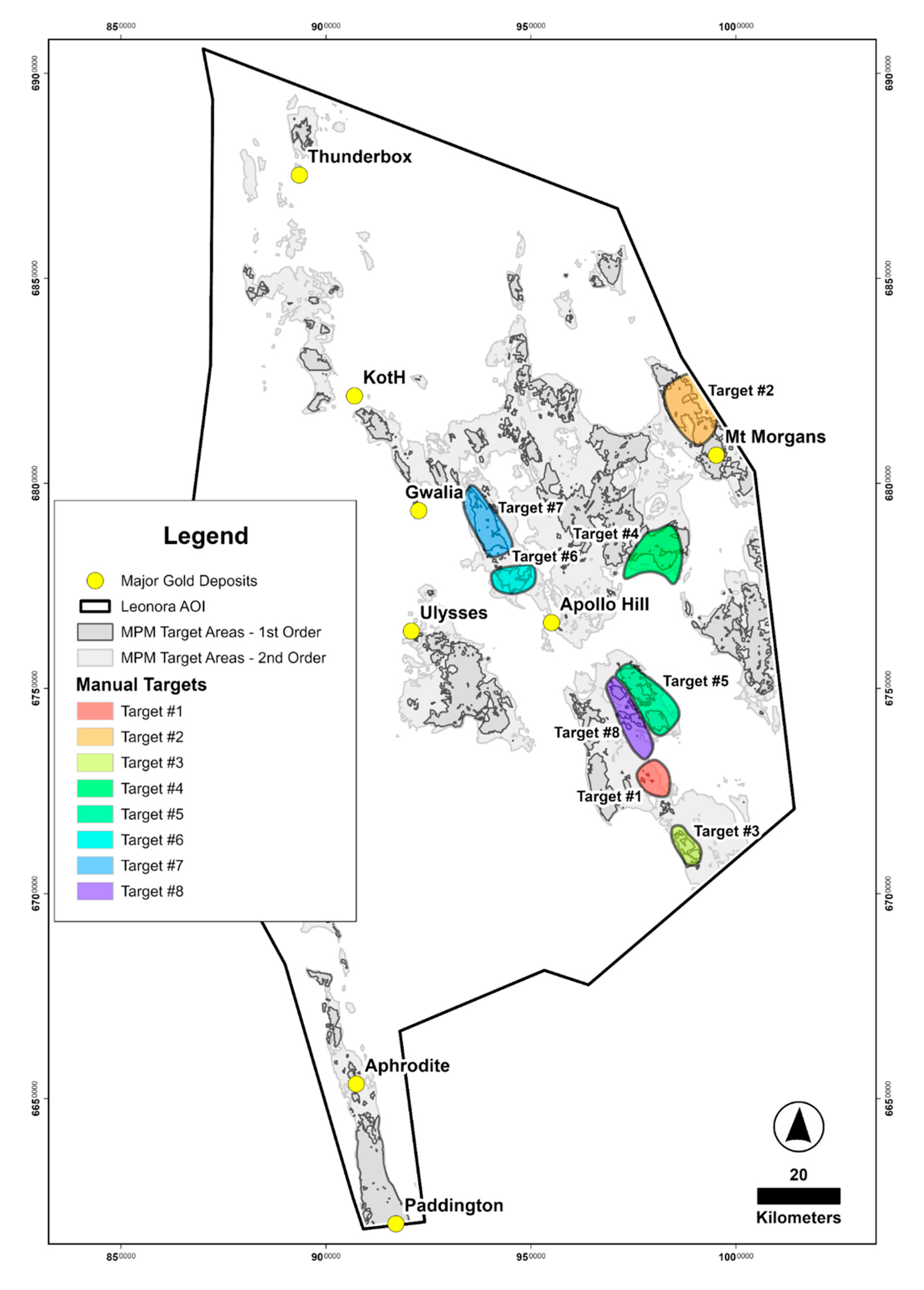

8.4.2. Assessment of MPM Target Areas

- Target #1: Covers a cluster of poorly tested intrusions of the McAuliffe Well Syenite that intruded mafic volcanic-dominant greenstone sequences, abut the first-order order Keith-Kilkenny fault system and are cut by E-W- to NW-SW-striking dolerite dykes. Shallow (maximum hole depth of 45 m) rotary air blast drilling by Saracen Gold Mines Proprietary Limited returned intercepts up to 1.00 m @ 12.28 g/t Au from 9.00 m (hole YER143), 1.00 m @ 6.94 g/t Au from 10 m (hole YER158) and 2.00 m @ 2.20 g/t Au (hole YER159), defining surficial, saprolite-hosted gold mineralization over an area of 400 by 300 m at the Dingo prospect. The adjacent Bull Terrier prospect returned up to 16.00 m # 2.59 g/t Au from 105.00 m (hole YBD-2) and 16.00 m @ 1.52 g/t Au from 60.00 m, including 1.00 m @ 211.70 g/t Au from 65.00 m (hole YRC-63) [164,165]. No deeper or broader, more systematic exploration drilling appears to have been completed across the McAuliffe Well Syenite intrusive cluster. Moreover, the cluster is held by various exploration companies. The disjointed ownership, which appears to have prevailed over decades, likely played a role in preventing a more holistic exploration approach.

- Target #2: Covers prospective mafic and felsic volcanic-dominant greenstone sequences, comprising chemically reactive banded iron formations (BIF) and syenite intrusions, along strike from the Mt Morgans gold production center. Previous drilling returned drilling intersections of up to 6.70 m @ 13.15 g/t Au from 95.00 m (hole MRC036), 5.90 m @ 7.24 g/t from 79.00 m (hole MRC003) and 2.90 m @ 5.41 m from 112 m (hole MRC028) from and defined a small (>150 koz Au @ 1.40 g/t Au) resource at the Korong-Waihi prospect. The latter remains open along strike and at depth with no prior drilling below a vertical depth of 150 m [166,167]. Similar to target #1, ownership of target #2 is disjointed, currently preventing a broader, more holistic approach to exploration.

9. Summary and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Au | Gold |

| DEMIRS | Department of Energy, Mines, Industry Regulation and Safety |

| EGST | Eastern Goldfields Superterrane |

| GSWA | Geological Survey of Western Australia |

| koz | Thousand ounces |

| MA | Time ago in millions of years |

| Moz | Million ounces |

| MPM | Mineral potential modeling |

| Mtpa | Millions of tonnes per annum |

| m.y. | Time span in millions of years |

| SBM | St Barbara Limited |

References

- Geological Survey of Western Australia. Gold Investment Opportunities; Government of Western Australia, Department of Energy, Mines, Industry Regulation and Safety: East Perth, Australia, 2023; 2p.

- Phillips, G.N.; Vearncombe, J.R.; Eshuys, E. Gold production and the importance of exploration success: Yilgarn Craton, Western Australia. Ore Geology Reviews 2019, 105, 137–150.

- Williams, P.R.; Nisbet, B.W.; Etheridge, M.A. Shear zones, gold mineralization and structural history in the Leonora district, Eastern Goldfields Province, Western Australia. Australian Journal of Earth Sciences 1989, 36(3), 383–403.

- Duuring, P.; Hagemann, S.G.; Cassidy, K.F.; Johnson, C.A. Hydrothermal alteration, ore fluid characteristics, and gold depositional processes along a trondhjemite-komatiite contact at Tarmoola, Western Australia. Economic Geology 2004, 99(3), 423–451.

- Morey, A.A.; Weinberg, R.F.; Bierlein, F.P. The structural controls of gold mineralisation within the Bardoc Tectonic Zone, Eastern Goldfields Province, Western Australia: Implications for gold endowment in shear systems. Mineralium Deposita 2007, 42(6), 583–600.

- Weinberg, R.F.; Van Der Borgh, P. Extension and gold mineralization in the Archean Kalgoorlie terrane, Yilgarn craton. Precambrian Research 2008, 161(1–2), 77–88.

- Blewett, R.S.; Czarnota, K.; Henson, P.A. Structural-event framework for the eastern Yilgarn Craton, Western Australia, and its implications for orogenic gold. Precambrian Research 2010, 183(2), 203–229.

- Czarnota, K.; Champion, D.C.; Goscombe, B.; Blewett, R.S.; Cassidy, K.F.; Henson, P.A.; Groenewald, P.B. Geodynamics of the eastern Yilgarn Craton. Precambrian Research 2010, 183(2), 175–202.

- Jones, S.A. Contrasting structural styles of gold deposits in the Leonora Domain: Evidence for early gold deposition, Eastern Goldfields, Western Australia. Australian Journal of Earth Sciences 2014, 61(7), 881–917.

- Jones, S.A. 2730-2670 Ma rifting triggers sagduction prior to the onset of orogenesis at ca 2650 Ma: Implications for gold mineralisation, Eastern Goldfields, Western Australia. Australian Journal of Earth Sciences 2024, 71(5), 647–672.

- Goscombe, B.; Foster, D.A.; Blewett, R.; Czarnota, K.; Wade, B.; Groenewald, B.; Gray, D. Neoarchean metamorphic evolution of the Yilgarn craton: A record of subduction, accretion, extension and lithospheric delamination. Precambrian Research 2019, 335, 105441.

- Witt, W.K.; Cassidy, K.F.; Lu, Y.J.; Hagemann, S.G. The tectonic setting and evolution of the 2.7 Ga Kalgoorlie–Kurnalpi Rift, a world-class Archean gold province. Mineralium Deposita 2020, 55(4), 601–631.

- Jones, S.A.; Cassidy, K.F.; Davis, B.K. Unravelling the D1 event: Evidence for early granite-up, greenstone-down tectonics in the Eastern Goldfields, Western Australia. Australian Journal of Earth Sciences 2021, 68(1), 1–35.

- Groves, D.I.; Goldfarb, R.J.; Knox-Robinson, C.M.; Ojala, J.; Gardoll, S.; Yun, G.Y.; Holyland, P. Late-kinematic timing of orogenic gold deposits and significance for computer-based exploration techniques with emphasis on the Yilgarn Block, Western Australia. Ore Geology Reviews 2000, 17(1–2), 1–38.

- Czarnota, K.; Blewett, R.S.; Goscombe, B. Predictive mineral discovery in the eastern Yilgarn Craton, Western Australia: an example of district scale targeting of an orogenic gold mineral system. Precambrian Research 2010, 183(2), 356–377.

- Witt, W.K.; Ford, A.; Hanrahan, B.; Mamuse, A. Regional-scale targeting for gold in the Yilgarn Craton: Part 1 of the Yilgarn gold exploration targeting atlas; Report 125. Geological Survey of Western Australia: East Perth, Australia, 2013; 130p.

- Witt, W.K.; Ford, A.; Hanrahan, B. District-scale targeting for gold in the Yilgarn Craton: Part 2 of the Yilgarn gold exploration targeting atlas; Report 132. Geological Survey of Western Australia: East Perth, Australia, 2015; 276p.

- Witt, W.K. Deposit-scale targeting for gold in the Yilgarn Craton: Part 3 of the Yilgarn gold exploration targeting atlas; Report 158. Geological Survey of Western Australia: East Perth, Australia, 2016; 182p.

- Knox-Robinson, C.M. Vectorial fuzzy logic: A novel technique for enhanced mineral prospectivity mapping, with reference to the orogenic gold mineralisation potential of the Kalgoorlie Terrane, Western Australia. Australian Journal of Earth Sciences 2000, 47(5), 929–941.

- Wyborn, L.A.I.; Heinrich, C.A.; Jaques, A.L. Australian Proterozoic mineral systems: Essential ingredients and mappable criteria. In Proceedings of the 1994 AusIMM Annual Conference: Australian Mining Looks North—The Challenges and Choices, Darwin, NT, Australia, 5–9 August 1994; pp. 109–115.

- McCuaig, T.C.; Beresford, S.; Hronsky, J. Translating the mineral systems approach into an effective exploration targeting system. Ore Geology Reviews 2010, 38, 128–138.

- McCuaig, T.C.; Hronsky, J.M.A. The mineral system concept—The key to exploration targeting. Society of Economic Geologists Special Publication 2014, 18, 153–175.

- An, P.; Moon, W.M; Rencz, A. Application of fuzzy set theory to integrated mineral exploration. Canadian Journal of Exploration Geophysics 1991, 27(1), 1–11.

- Bonham-Carter, G.F. Geographic Information Systems for Geoscientists: Modelling with GIS; Pergamon: Oxford, UK, 1994; 416p.

- St Barbara Limited. St Barbara agrees to sale of Leonora assets to Genesis Minerals for total consideration of $600 million. In Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) Announcement dated 17 April 2023; St Barbara Limited: West Perth, Australia, 2023; 5p.

- Knox-Robinson, C.M.; Wyborn, L.A.I. Towards a holistic exploration strategy: Using geographic information systems as a tool to enhance exploration. Australian Journal of Earth Sciences 1997, 44, 453–463.

- Kreuzer, O.P.; Etheridge, M.A.; Guj, P.; McMahon, M.E.; Holden, D.J. Linking mineral deposit models to quantitative risk analysis and decision-making in exploration. Economic Geology 2008, 103, 829–850.

- Kreuzer, O.P.; Roshanravan, B. Transforming LCT pegmatite targeting models into AI-powered predictive maps of lithium potential for Western Australia and Ontario: Approach, results and implications. Minerals 2025, 15(4), 397.

- Buckingham, A.J; Core, D.P.; Hart, C.J.R.; Jenkins, S. TREK project area gravity compilation, enhancement filtering and structure detection; Geoscience BC Report 2017-14; Geoscience BC, Vancouver, Canada, 2017; 34p.

- Kreuzer, O.P.; Buckingham, A.; Mortimer, J.; Walker, G.; Wilde, A.; Appiah, K. An integrated approach to the search for gold in a mature, data-rich brownfields environment: A case study from Sigma-Lamaque, Quebec. Ore Geology Reviews 2019, 111, 102977.

- Roshanravan, B.; Kreuzer, O.P.; Buckingham, A.; Keykhay-Hosseinpoor, M.; Keys, E. Mineral potential modelling of orogenic gold systems in the Granites-Tanami Orogen, Northern Territory, Australia: A multi-technique approach. Ore Geology Reviews 2023, 152, 105224.

- Goscombe, B.; Blewett, R.S.; Czarnota, K.; Groenewald, B.; Maas, R. Metamorphic evolution and integrated terrane analysis of the Eastern Yilgarn Craton: Rationale, methods, outcomes and interpretation; Record 2009(23); Geoscience Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2009, 270p.

- Mole, D.R.; Fiorentini, M.L.; Cassidy, K.F.; Kirkland, C.L.; Thébaud, N.; McCuaig, T.C.; Doublier, M.P.; Duuring, P.; Romano, S.S.; Maas, R.; Belousova, E.A.; Barnes, S.J; Miller, J. Crustal evolution, intra-cratonic architecture and the metallogeny of an Archaean craton. In Ore deposits in an evolving Earth; Jenkin, G.R.T.; Lusty, P.A.J.; McDonald, I.; Smith, M.P.; Boyce, A.J.; Wilkinson, J.J., Eds.; Special Publications, Geological Society, London, 2015; Volume 393, pp. 23–80.

- Dentith, M.; Mudge, S.T. Geophysics for the mineral Exploration geoscientist. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, United Kingdom, 454p.

- Bierlein, F.; Murphy, F.C.; Weinberg, R.F.; Lees, T. Distribution of orogenic gold deposits in relation to fault zones and gravity gradients: Targeting tools applied to the Eastern Goldfields, Yilgarn Craton, Western Australia. Mineralium Deposita 2006, 41(2), 107–126.

- Cordell, L. Gravimetric expression of graben faulting in Santa Fe country and the Espanola Basin, New Mexico. In Guidebook to Santa Fe Country: Thirtieth Field Conference, October 4-6, 1979, Ingersoll, R.V., Ed.; New Mexico Geological Society: Socorro, United States, 1979; pp. 59–64.

- Grauch, V.J.S.; Cordell, L. Limitations of determining density or magnetic boundaries from the horizontal gradient of gravity or pseudogravity data. Geophysics 1987, 52, 118–121.

- Kovesi, P.D. Image features from phase congruency. Videre: Journal of Computer Vision Research 1999, 1(3), 1–26.

- Jacobsen, B.H. A case for upward continuation as a standard separation filter for potential-field maps. Geophysics 1987, 52(8), 1138–1148.

- Cazals F.; Pouget M. Topology driven algorithms for ridge extraction on meshes; Raport Recherche 5526. Institut National de Recherche en Sciences et Technologies du Numérique (INRIA), Sophia Antipolis, France, 2005; 29p.

- de Quadros, T.F.; Koppe, J.C.; Strieder, A.J.; Costa, J.F.C. Gamma-ray data processing and integration for lode-Au deposits exploration. Natural Resources Research 2003, 12(1), 57–65.

- Herbert, S.; Woldai, T.; Carranza, E.J.M.; van Ruitenbeek, F.J. Predictive mapping of prospectivity for orogenic gold in Uganda. Journal of African Earth Sciences 2014, 99, 666–693.

- Shebl, A.; Abdellatif; M., Badawi, M.; Dawoud, M.; Fahil, A.S.; Csámer, Á. Towards better delineation of hydrothermal alterations via multi-sensor remote sensing and airborne geophysical data. Scientific Reports 2023, 13(1), 7406.

- Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency. ALOS World 3D 30 meter DEM, version 3.2, Jan 2021. Distributed by OpenTopography. Available online: https://doi.org/10.5069/G94M92HB (accessed on 18 November 2022).

- Mielke, C.; Boesche, N.K.; Rogass, C.; Kaufmann, H.; Gauert, C.; de Wit, M. Spaceborne mine waste mineralogy monitoring in South Africa, applications for modern push-broom missions: Hyperion/OLI and EnMAP/Sentinel-2. Remote Sensing 2014, 6, 6790–6815.

- ISO/CIE. Colorimetry—Part 4: CIE 1976 L*a*b* colour space. International Standard, ISO/CIE 11664-4:2019. Available online: https://cdn.standards.iteh.ai/samples/74166/8056d4c35bb24b54a6a7761c51f2575f/ISO-CIE-11664-4-2019.pdf (accessed on 01 October 2025).

- Siddorn, J.P; Williams, P.R; Isles, D.J., Rankin, L.R. Integrated geologic-geophysical interpretation of district-scale structural frameworks: Systematic approaches for targeting mineralizing systems. In Applied structural geology of ore-forming hydrothermal systems; Reviews in Economic Geology 21; Rowland, J.V., Rhys, D.A., Eds.; Society of Economic Geologists, Littleton, United States, 2020; pp. 271–313.

- Hagemann, S.G.; Lisitsin, V.A.; Huston, D.L. Mineral system analysis: Quo vadis. Ore Geology Reviews 2016, 76, 504–522.

- Kreuzer, O.P.; Miller, A.V.; Peters, K.J.; Payne, C.; Wildman, C.; Partington, G.A.; Puccioni, E.; McMahon, M.E.; Etheridge, M.A. Comparing prospectivity modelling results and past exploration data: A case study of porphyry Cu–Au mineral systems in the Macquarie Arc, Lachlan Fold Belt, New South Wales. Ore Geology Reviews 2015, 71, 516–544.

- Roshanravan, B.; Kreuzer, O.P.; Bruce, M.; Davis, J.; Briggs, M. Modelling gold potential in the Granites-Tanami Orogen, NT, Australia: A comparative study using continuous and data-driven techniques. Ore Geology Reviews 2020, 125, 103661.

- Kreuzer, O.P.; Yousefi, M.; Nykänen, V. Introduction to the special issue on spatial modelling and analysis of ore-forming processes in mineral exploration targeting. Ore Geology Reviews 2020, 119, 103391.

- Fry, N. Random point distributions and strain measurement in rocks. Tectonophysics 1979, 60, 1–2, 89–105.

- Vearncombe, J.R.; Vearncombe, S. The spatial distribution of mineralization; applications of Fry analysis. Economic Geology 1999, 94(4), 475–486.

- Kreuzer, O.P.; Blenkinsop, T.G.; Morrison, R.J.; Peters, S.G. Ore controls in the Charters Towers goldfield, NE Australia: Constraints from geological, geophysical and numerical analyses. Ore Geology Reviews 2007, 32(1–2), 37–80.

- Carranza, E.J.M. Controls on mineral deposit occurrence inferred from analysis of their spatial pattern and spatial association with geological features. Ore Geology Reviews 2009, 35, 383–400.

- Agterberg, F.P. Computer programs for mineral exploration. Science 1989, 245, 76–81.

- Bonham-Carter, G.F.; Agterberg, F.P.; Wright, D.F. Integration of geological datasets for gold exploration in Nova Scotia. Digital Geological and Geographical Information Systems 1989, 10, 15–23.

- Carranza, E.J.M. Geochemical Anomaly and Mineral Prospectivity Mapping in GIS—Handbook of Exploration and Environmental Geochemistry 11; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; 351p.

- Joly, A.; Porwal, A.K.; McCuaig, T.C. Exploration targeting for orogenic gold deposits in the Granites-Tanami Orogen: Mineral system analysis, targeting model and prospectivity analysis. Ore Geology Reviews 2012, 48, 349–383.

- Porwal, A.K.; Carranza, E.J.M. Introduction to the special issue: GIS-based mineral potential modelling and geological data analyses for mineral exploration. Ore Geology Reviews 2015, 71, 477–483.

- Keykhay-Hosseinpoor, M.; Porwal, A.; Rajendran, K.; Panja, S. Mineral system modeling of Lithium-Cesium- Tantalum (LCT)-type pegmatites: Regional-scale exploration targeting and uncertainty analysis in the Sanandaj-Sirjan zone, Western Iran. Journal of Geochemical Exploration 2025, 107885.

- Roshanravan, B.; Kreuzer, O.P.; Buckingham, A. BWM-MARCOS: A new hybrid MCDM approach for mineral potential modelling. Journal of Geochemical Exploration 2025, 269, 107639.

- Yousefi, M.; Nykänen, V. Data-driven logistic-based weighting of geochemical and geological evidence layers in mineral prospectivity mapping. Journal of Geochemical Exploration 2016, 164, 94–106.

- Yousefi, M.; Carranza, E.J.M. Fuzzification of continuous-value spatial evidence for mineral prospectivity mapping. Computers & Geosciences 2015, 74, 97–109.

- Yousefi, M.; Carranza, E.J.M. Geometric average of spatial evidence data layers: a GIS-based multi-criteria decision-making approach to mineral prospectivity mapping. Computers & Geosciences 2015, 83, 72–79.

- Aryafar, A.; Roshanravan, B. Improved index overlay mineral potential modeling in brown- and greenfields exploration using geochemical, geological and remote sensing data. Earth Science Informatics 2020, 1–17.

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Machine Learning 2001, 45, 5–32.

- Hwang, C-L.; Yoon, K. Methods for multiple attribute decision making. In Multiple Attribute Decision Making; Hwang, C-L., Yoon, K., Eds.; Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany, 1981, 58–191.

- Afshari, A.; Mojahed, M.; Yusuff, R.M. Simple additive weighting approach to personnel selection problem. International Journal of Innovation, Management and Technology 2010, 1, 511.

- Rezaei, J. Best-worst multi-criteria decision-making method. Omega 2015, 53, 49–57.

- Huston, D.L.; Blewett, R.S.; Champion, D.C. Australia through time: A summary of its tectonic and metallogenic evolution. Episodes 2012, 35, 23–43.

- Cassidy, K.F.; Champion, D.C.; Krapež, B.; Barley, M.E.; Brown, S.J.A.; Blewett, R.S.; Groenewald, P.; Tyler, I.M. A revised geological framework for the Yilgarn Craton, Western Australia; Record 2006(8); Geological Survey of Western Australia: East Perth, Australia, 2006; 15p.

- Wyche, S.; Fiorentini, M.L.; Miller, J.L.; McCuaig, T.C. Geology and controls on mineralisation in the Eastern Goldfields region, Yilgarn Craton, Western Australia. Episodes Journal of International Geoscience 2012, 35(1), 273–282.

- Masurel, Q.; Thébaud, N. Deformation in the Agnew-Wiluna greenstone belt and host Kalgoorlie Terrane during the c. 2675–2630 Ma Kalgoorlie Orogeny: ∼45 Ma of horizontal shortening in a Neoarchean back-arc region. Precambrian Research 2024, 414, 107586.

- McCuaig, T.C.; Miller, J.M.; Beresford, S. Controls on giant mineral systems in the Yilgarn Craton—a field guide; Record 2010(26); Geological Survey of Western Australia: East Perth, Australia, 2010; 159p.

- Jones, S.A. 2730-2670 Ma rifting triggers sagduction prior to the onset of orogenesis at ca 2650 Ma: Implications for gold mineralisation, Eastern Goldfields, Western Australia. Australian Journal of Earth Sciences 2024, 71(5), 647–672.

- Krapež, B.; Barley, M.E.; Brown, S.J. Late Archaean synorogenic basins of the Eastern Goldfields Superterrane, Yilgarn Craton, Western Australia: Part I. Kalgoorlie and Gindalbie Terranes. Precambrian Research 2008, 161(1–2), 135–153.

- Wyche, S. Geological setting of mineral deposits in the eastern Yilgarn Craton—A field guide; Record 2014(10); Geological Survey of Western Australia: East Perth, Australia, 2014; 56p.

- Czarnota, K.; Blewett, R.S.; Goscombe, B. Structural and metamorphic controls on gold through time and space in the central Eastern Goldfields Superterrane—A field guide, Record 2008(9); Geological Survey of Western Australia: East Perth, Australia, 2008; 66p.

- Weinberg, R.F.; Moresi, L.; Van der Borgh, P. Timing of deformation in the Norseman-Wiluna belt, Yilgarn craton, Western Australia. Precambrian Research 2003, 120(3–4), 219–239.

- Brown, M.; Johnson, T.; Gardiner, N.J. Plate tectonics and the Archean Earth. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 2020, 48(1), 291–320.

- Windley, B.F.; Kusky, T.; Polat, A. Onset of plate tectonics by the Eoarchean. Precambrian Research 2021, 352, 105980.

- Kuang, J.; Morra, G.; Yuen, D.A.; Kusky, T.; Jiang, S.; Yao, H.; Qi, S. Metamorphic constraints on Archean tectonics. Precambrian Research 2023, 397, 107–195.

- Blewett, R.S; Czarnota, K. Tectonostratigraphic architecture and uplift history of the eastern Yilgarn Craton; Record 2007(15); Geological Survey of Western Australia: East Perth, Australia, 2007; 114p.

- Krapež, B.; Barley, M.E. Late Archaean synorogenic basins of the Eastern Goldfields Superterrane, Yilgarn Craton, Western Australia: Part III. Signatures of tectonic escape in an arc-continent collision zone. Precambrian Research 2008, 161(1–2), 183–199.

- Masurel, Q.; Thébaud, N.; Saptoka, J.; De Paoli, M.C.; Drummond, M.; Smithies, R.H. Stratigraphy of the Agnew-Wiluna greenstone belt: Review, synopsis, and implications for the late Mesoarchean to Neoarchean geological evolution of the Yilgarn Craton. Australian Journal of Earth Sciences 2022, 69, 1149–1176.

- Yilgarn Craton—Geology, structure and mineralisation (PorterGeo). Available online: https://portergeo.com.au/database/mineinfo.asp?mineid=mn1626 (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- KCGM operations (Northern Star Resources Limited). Available online: https://www.nsrltd.com/our-assets/kcgm-operations/ (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Sons of Gwalia, Gwalia, Tower Hill (PorterGeo). Available online: https://portergeo.com.au/database/mineinfo.asp?mineid=mn761 (accessed on 02 August 2025).

- Vielreicher, R.M.; Groves, D.I.; Ridley, J.R.; McNaughton, N.J. A replacement origin for the BIF-hosted gold deposit at Mt. Morgans, Yilgarn Block, WA. Ore Geology Reviews 1994, 9(4), 325–347.

- Bennett, M.A. Thunderbox gold and Waterloo nickel deposits. In Gold and nickel deposits in the Norseman-Wiluna greenstone belt, Yilgarn Craton, Western Australia—A field guide, Record 2014(16); Neumayr, P., Harris, M., Beresford, S.W., Eds.; Geological Survey of Western Australia: East Perth, Australia, 2014; 166p.

- Castle, M. Independent geologist’s report on the Apollo Hill gold project in Western Australia. In Prospectus Saturn Metals Limited ACN 619 488 498, Saturn Metals Limited: West Perth, Australia, 2018; pp. 53–132.

- Standing, J.; Outhwaite, M.; Fay, C.; Martin, D.; McCormack, B. Aphrodite geological campaign 2018. Confidential Report to Spitfire Materials Limited, Model Earth Proprietary Limited, March 2018, 59p.

- Harris, M.; Fleming, S.; Dudfield, L.; Savage, B. Melita project—Ulysses gold deposit, Western Australia. In Regolith expression of Australian ore systems—A compilation of geochemical case histories and conceptual models; Butt, C.R.M., Cornelius, M., Scott, K.M., Robertson, I.D.M., Eds.; Cooperative Research Centre for Landscape Environments and Mineral Exploration (CRC LEME), 3p. Available online: https://crcleme.org.au/RegExpOre/Ulysses.pdf (accessed on 02 August 2025).

- Genesis Minerals Limited. Ulysses mineral resource soars 137% to 760,000 ounces. In Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) Announcement dated 09 October 2018; Genesis Minerals Limited: Perth, Australia, 2018; 17p.

- Witt, W.K. Gold mineralization in the Menzies-Kambalda region, Eastern Goldfields, Western Australia; Report 39; Geological Survey of Western Australia: East Perth, Australia, 1993; 165p.

- Martinick McNulty Pty Limited. Notice of intent to mine the Wonder orebody. In Department of Energy, Mines, Industry Regulation and Safety (DEMIRS), Government of Western Australia, GeoDocs, Document MP3808, 09 October 2001; Martinick McNulty Pty Limited: West Perth, Australia; 79p. Available online: https://geodocs.dmirs.wa.gov.au/Web/documentlist/9/EARS_regi_id/17195 (accessed on 02 August 2025).

- Allchurch, J.D. Celtic Project, Annual report covering 01/04/2016 to 31/03/2017, combined reporting number C28/2012 for P37/8306, P37/8382, P37/8383, P37/8384, P37/8385, P37/8386, M37/350, M37/488, M37/513, M37/514 and M37/638. In Department of Energy, Mines, Industry Regulation and Safety (DEMIRS), Government of Western Australia, WAMEX Mineral Reporting System, Report Number A114129, 21 September 2017; S R Mining Pty Limited and Bligh Resources Limited: Fremantle, WA, Australia; 17p. Available online: https://wamex.dmp.wa.gov.au/Wamex/Search/ReportDetails?ANumber=114129 (accessed on 02 August 2025).

- Schmitt, L.A. The dolerite-hosted Zoroastrian gold deposit, Yilgarn Craton, Western Australia: Lithogeochemistry, alteration zonation patterns and source of sulfur. MSc Thesis, Oulu Mining School, University of Oulu, Oulu, Finland, 2017, 91p.

- Dunbar, P.; Fairfield, P. Independent technical assessment & valuation report, Bardoc Gold Limited Scheme Booklet. In Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) Announcement dated 23 February 2022; Bardoc Gold Limited: North Fremantle, WA, Australia, 2022; 328p.

- Kretz, R. Symbols for rock-forming minerals. American Mineralogist 1983, 68, 277–279.

- List of mineral abbreviations. Siivola, J, and Schmid, R. A systematic nomenclature for metamorphic rocks: 12. List of mineral abbreviations. Recommendations by the IUGS Subcommission on the Systematics of Metamorphic Rocks. Recommendations, web version of 01.02.2007. Available online: https://www2.bgs.ac.uk/scmr/products.html (accessed on 02 August 2025).

- Groves, D.I. The crustal continuum model for late-Archaean lode-gold deposits of the Yilgarn Block, Western Australia. Mineralium Deposita 1993, 28(6), 366–374.

- Groves, D.I.; Ridley, J.R.; Bloem, E.M.J.; Gebre-Mariam, M.; Hagemann, S.G.; Hronsky, J.M.A.; Knight, J.T.; McNaughton, N.J.; Ojala, J.; Vielreicher, R.M.; McCuaig, T.C. Lode-gold deposits of the Yilgarn block: Products of Late Archaean crustal-scale overpressured hydrothermal systems. In Early Cambrian processes, Special Publications, 95(1); Coward, M.P., Ries, A.C., Eds.; Geological Society of London: London, United Kingdom, 1995; pp. 155–172.

- Tripp, G.I.; Tosdal, R.M.; Blenkinsop, T.; Rogers, J.R.; Halley, S. Neoarchean Eastern Goldfields of Western Australia. In Geology of the World’s Major Gold Deposits and Provinces, Sillitoe, R.H., Goldfarb, R.J., Simmons, S.F., Eds.; Society of Economic Geologists: Littleton, Colorado, USA; 2020; pp. 709–734.

- Gold Road Resources Limited. Company presentation. In Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) Announcement dated 23 May 2013; Gold Road Resources Limited: West Perth, Australia, 2013; 26p.

- Pisarevsky, S.A.; De Waele, B.; Jones, S.; Söderlund, U.; Ernst, R.E. Paleomagnetism and U-Pb age of the 2.4 Ga Erayinia mafic dykes in the south-western Yilgarn, Western Australia: Paleogeographic and geodynamic implications. Precambrian Research 2015, 259, 222–231.

- Wingate, M.T.D. Mafic dyke swarms and large igneous provinces in Western Australia get a digital makeover. In GSWA 2017 extended abstracts—Promoting the prospectivity of Western Australia, Record 2017/2; Geological Survey of Western Australia: East Perth, Australia, 2017; pp. 4–8.

- McCuaig, T.C.; Kreuzer, O.P.; Brown, W.M. Fooling ourselves—Dealing with model uncertainty in a mineral systems approach to exploration. In Proceedings of the 9th biennial SGA meeting “Mineral exploration and research: Digging deeper”, Dublin, Ireland, 20–23 August 2007, pp. 1435–1438.

- Hronsky, J.M.A.; Groves, D.I. Science of targeting: Definition, strategies, targeting and performance measurement. Australian Journal of Earth Sciences 2008, 55, 3–12.

- Lord, D.; Etheridge, M.A.; Willson, M.; Hall, G.; Uttley, P.J. Measuring exploration success: An alternative to the discovery-cost-per-ounce method of quantifying exploration success. Society of Economic Geologists (SEG) Newsletter 2001, 45, 1 and 10–16.

- Penney, S.R.; Allen, R.M.; Harrisson, S.; Lees, T.C.; Murphy, F.C.; Norman, A.R.; Roberts, P.A. A global-scale exploration risk analysis technique to determine the best mineral belts for exploration. Transactions of Institute of Mining and Metallurgy 2004, 133, B183–B196.

- Porwal, A.K.; Kreuzer, O.P. Introduction to the special issue: Mineral prospectivity analysis and quantitative resource estimation. Ore Geology Reviews 2010, 38(3), 121–127.

- Hronsky, J.M., Kreuzer, O.P. Applying spatial prospectivity mapping to exploration targeting: Fundamental practical issues and suggested solutions for the future. Ore Geology Reviews 2019, 107, 647–653.

- Bárdossy, G.; Fodor, J. Traditional and new ways to handle uncertainty in geology. Natural Resources Research 2001, 10(3), 179–187.

- Hronsky, J.M.; Groves, D.I.; Loucks, R.R.; Begg, G.C. A unified model for gold mineralisation in accretionary orogens and implications for regional-scale exploration targeting methods. Mineralium Deposita 2012, 47(4), 339–358.

- Groves, D.I.; Santosh, M.; Müller, D.; Zhang, L.; Deng, J.; Yang, L.Q.; Wang, Q.F. Mineral systems: Their advantages in terms of developing holistic genetic models and for target generation in global mineral exploration. Geosystems and Geoenvironment 2022, 1(1), 100001.

- Sibson, R.H. Hinge-parallel fluid flow in fold-thrust belts: How widespread? Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association 2005, 116(3–4), 301–309.

- Cox, S.; Knackstedt, M.; Braun, J. Principles of structural control on permeability and fluid flow in hydrothermal systems. Reviews in Economic Geology 2001, 14, 1–24.

- Tripp, G.I.; Vearncombe, J.R. Fault/fracture density and mineralization: A contouring method for targeting in gold exploration. Journal of Structural Geology 2004, 26(6–7), 1087–1108.

- Groves, D.I.; Santosh, M.; Goldfarb, R.J.; Zhang, L. Structural geometry of orogenic gold deposits: Implications for exploration of world-class and giant deposits. Geoscience Frontiers 2018, 9(4), 1163–1177.

- Sibson, R.H.; Scott, J. Stress/fault controls on the containment and release of overpressured fluids: Examples from gold-quartz vein systems in Juneau, Alaska; Victoria, Australia and Otago, New Zealand. Ore Geology Reviews 1998, 13(1–5), 293–306.

- Sibson, R.H. Fault-valve behavior and the hydrostatic-lithostatic fluid pressure interface. Earth-Science Reviews 1992, 32(1–2), 141–144.

- McQueen, K.G. Ore deposit types and their primary expressions. In Regolith expression of Australian ore systems: A Compilation of exploration case histories with conceptual dispersion, process and exploration models; Butt, C.R.M., Robertson, I.D.M., Scott, K.M., Cornelius, M, Eds.; Cooperative Research Centre for Landscape Environments and Mineral Exploration (CRCLEME), Bentley, Australia, 2005; pp. 1–14.

- Phillips, G.N.; Thomson, D.F., Kuehn, C.A. Deep weathering of deposits in the Yilgarn and Carlin gold provinces. In Proceedings of the Regolith ’98 Conference: New approaches to an old continent, Kalgoorlie, Australia, 2–9 May 1998, pp. 1–22; Available online: https://crcleme.org.au/Pubs/Monographs/regolith98/1-phillips_et_al.pdf (accessed on 02 August 2025).

- Mihalasky, M.J.; Bonham-Carter, G.F. Lithodiversity and its spatial association with metallic mineral sites, Great Basin of Nevada. Natural Resources Research 2001, 10, 209–226.

- Roshanravan, B.; Agajani, H.; Yousefi, M.; Kreuzer, O.P. Generation of a geochemical model to prospect podiform chromite deposits in north of Iran. In 80th EAGE Conference and Exhibition, Copenhagen, Denmark, 11-14 June 2018.

- Nykänen, V.; Lahti, I.; Niiranen, T.; Korhonen, K. Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) as validation tool for prospectivity models—A magmatic Ni-Cu case study from the central Lapland greenstone belt, northern Finland. Ore Geology Reviews 2015, 71, 853–860.

- Tsoukalas, L.H.; Uhrig, R.E. Fuzzy and Neural Approaches in Engineering; John Wiley & Sons: New York, USA, 1997; 606p.

- Nykänen, V.; Groves, D.I.; Ojala, V.J.; Eilu, P.; Gardoll, S.J. Reconnaissance-scale conceptual fuzzy-logic prospectivity modelling for iron oxide copper-gold deposits in the northern Fennoscandian Shield, Finland. Australian Journal of Earth Sciences 2008, 55, 25–38.

- Zimmermann, H. J. Fuzzy set theory—and its applications; Kluwer Academic Publishing: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 1996; 399p.

- Karbalaei-Ramezanali, A.; Feizi, F.; Jafarirad, A.; Lotfi, M. Application of best-worst method and additive ratio assessment in mineral prospectivity mapping: A case study of vein-type copper mineralization in the Kuhsiah-e-Urmak Area, Iran. Ore Geology Reviews 2020, 117, 103268.

- Feizi, F.; Karbalaei-Ramezanali, A.A.; Farhadi, S. FUCOM-MOORA and FUCOM-MOOSRA: New MCDM-based knowledge-driven procedures for mineral potential mapping in greenfields. SN Applied Sciences 2021, 3, 358.

- Aryafar, A.; Roshanravan, B. BWM-SAW: A new hybrid MCDM technique for modeling of chromite potential in the Birjand district, east of Iran. Journal of Geochemical Exploration 2021, 231, 106876.

- Riahi, S.; Fathianpour, N.; Tabatabaei, S.H. Improving the accuracy of detecting and ranking favorable porphyry copper prospects in the east of Sarcheshmeh copper mine region using a two-step sequential Fuzzy-Fuzzy TOPSIS integration approach. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences 2023, 10, 100166.

- Roshanravan, B.; Aghajani, H.; Yousefi, M.; Kreuzer, O.P. An improved prediction-area plot for prospectivity analysis of mineral deposits. Natural Resources Research 2019, 28, 1089–1105.

- Roshanravan, B.; Kreuzer, O.P.; Buckingham, A.; Keys, E. On data quality in mineral potential modelling: A case study using Random Forest and fractal techniques. In 84th EAGE Annual Conference & Exhibition, Vienna, Austria, 5-8 June 2023.

- Roshanravan, B.; Kreuzer, O.P. An optimized XGBoost approach to prospectivity modelling of orogenic gold systems in the Granites-Tanami Orogen, Australia. In 86th EAGE Annual Conference & Exhibition, Toulouse, France, 1-5 June 2025.

- Rodriguez-Galiano, V.F.; Chica-Olmo, M.; Chica-Rivas, M.; Predictive modelling of gold potential with the integration of multisource information based on random forest: A case study on the Rodalquilar area, Southern Spain. International Journal of Geographical Information Science 2014, 28, 1336–1354.

- Carranza, E.J.M.; Laborte, A.G.; Random forest predictive modeling of mineral prospectivity with small number of prospects and data with missing values in Abra (Philippines). Computers & Geosciences 2015, 74, 60–70.

- Sun, T.; Chen, F.; Zhong, L.; Liu, W.; Wang, Y.; GIS-based mineral prospectivity mapping using machine learning methods: A case study from Tongling ore district, eastern China. Ore Geology Reviews 2019, 109, 26–49.

- Xiang, J.; Xiao, K.; Carranza, E.J.M.; Chen, J.; Li, S.; 3D mineral prospectivity mapping with random forests: A case study of Tongling, Anhui, China. Natural Resources Research 2020, 29, 395–414.

- Zhang, S.; Carranza, E.J.M.; Xiao, K.; Wei, H.; Yang, F.; Chen, Z.; Xiang, J.; Mineral prospectivity mapping based on isolation forest and random forest: Implication for the existence of spatial signature of mineralization in outliers. Natural Resources Research 2022, 31, 1981–1999.

- Isles, D.J.; Cooke, A.C. Spatial associations between post-cratonisation dykes and gold deposits in the Yilgarn Block, Western Australia. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Dyke Conference—Mafic Dykes and emplacement mechanisms; Adelaide, Australia, 12-16 September 1990; pp. 157–162.

- Cowan, E.J.; Hobbs, B.E. Perkins Discontinuities: Structurally controlled grade patterns diagnostic of epigenetic gold mineralisation at the deposit-scale. Australian Journal of Earth Sciences 2025, 1–41.

- Kreuzer, O.P. Bardoc gold study. Confidential Report to St Barbara Limited, Corporate Geoscience Group, February 2023, 85p.

- Crameri, K. Structural controls on mineralisation within the Alpha Lode at the Aphrodite deposit, Western Australia. BSc (Honours) Thesis, University of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia, 2002, 63p.

- Ge, W.; Cheng, Q.; Jing, L.; Wang, F.; Zhao, M.; Ding, H. Assessment of the capability of Sentinel-2 imagery for iron-bearing minerals mapping: A case study in the Cuprite area, Nevada. Remote Sensing 2020, 12(18), 3028.

- Kimpe, C.D.; Miles, N. Formation of swelling clay minerals by sulfide oxidation in some metamorphic rocks and related soils of Ontario, Canada. Canadian Journal of Soil Science 1992, 72(3), 263–270.

- Anand, R.R.; Butt, C.R.M. A guide for mineral exploration through the regolith in the Yilgarn Craton, Western Australia. Australian Journal of Earth Sciences 2010, 57(8), 1015–1114.

- Cheng, Q.; Agterberg, F.P.; Ballantyne, S.B. The separation of geochemical anomalies from background by fractal methods. Journal of Geochemical Exploration 1994, 51(2), 109–130.

- Afzal, P.; Yasrebi, A.B.; Saein, L.D.; Panahi, S. Prospecting of Ni mineralization based on geochemical exploration in Iran. Journal of Geochemical Exploration 2017, 181, 294–304.

- Nezhad, S.G.; Mokhtari, A.R.; Rodsari, P.R. The true sample catchment basin approach in the analysis of stream sediment geochemical data. Ore Geology Reviews 2017, 83, 127–134.

- Keykhay-Hosseinpoor, M.; Porwal, A.; Rajendran, K.; Panja, S. Mineral system modeling of lithium-cesium-tantalum (LCT)-type pegmatites: Regional-scale exploration targeting and uncertainty analysis in the Sanandaj-Sirjan zone, Western Iran. Journal of Geochemical Exploration 2025, 107885.

- Partington, G. Developing models using GIS to assess geological and economic risk: An example from VMS copper gold mineral exploration in Oman. Ore Geology Reviews 2010, 38(3), 197–207.

- Chudasama, B.; Porwal, A.; Kreuzer, O.P.; Butera, K. Geology, geodynamics and orogenic gold prospectivity modelling of the Paleoproterozoic Kumasi Basin, Ghana, West Africa. Ore Geology Reviews 2016, 78, 692–711.

- Chudasama, B.; Kreuzer, O.P.; Thakur, S.; Porwal, A.; Buckingham, A. Surficial uranium mineral systems in Western Australia: Geologically-permissive tracts and undiscovered endowment. In Quantitative and Spatial Evaluations of Undiscovered Uranium Resources, IAEA-TECDOC-1861; International Atomic Energy Agency: Vienna, Austria, 2018, pp. 446–614.

- Bruce, M.; Kreuzer, O.P.; Wilde, A.; Buckingham, A.; Butera, K.; Bierlein, F. Unconformity-type uranium systems: A comparative review and predictive modelling of critical genetic factors. Minerals 2020, 10(9), 738.

- Partington, G.A.; Peters, K.J.; Czertowicz, T.A.; Greville, P.A.; Blevin, P.L.; Bahiru, E.A. Ranking mineral exploration targets in support of commercial decision making: A key component for inclusion in an exploration information system. Applied Geochemistry 2024, 168, 106010.

- Chalice Mining Limited. Significant nickel-palladium discovery confirmed at Julimar. In Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) Announcement dated 15 April 2020; Chalice Mining Limited: West Perth, Australia, 2020; 19p. Available online: https://chalicemining.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/6975195.pdf (accessed on 08 September 2025).

- Dulfer, H.; Skirrow, R.G.; Champion, D.C; Highet, L.M.; Czarnota, K.; Coghlan, R.; Milligan, P.R. Potential for intrusion-hosted Ni-Cu-PGE sulfide deposits in Australia: A continental-scale analysis of mineral system prospectivity; Record 2016(01); Geoscience Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2016; 97p.

- Porwal, A.; Carranza, E.J.M.; Hale, M. Knowledge-driven and data-driven fuzzy models for predictive mineral potential mapping. Natural Resources Research 2003, 12(1), 1–25.

- Kreuzer, O.P.; Markwitz, V.; Porwal, A.K.; McCuaig, T.C. A continent-wide study of Australia’s uranium potential: Part I: GIS-assisted manual prospectivity analysis. Ore Geology Reviews 2010, 38(4), 334–366.

- Roberts, F.I.; Witt, W.K.; Westaway, J. Gold mineralization in the Edjudina-Kanowna region, Eastern Goldfields, Western Australia; Report 90; Geological Survey of Western Australia: East Perth, Australia, 2004; 277p.

- Blina Minerals NL. Acquisition of Dingo gold project. In Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) Announcement dated 05 May 2017; Blina Minerals NL: West Perth, Australia, 2017; 14p. Available online: https://announcements.asx.com.au/asxpdf/20170505/pdf/43j1p43h2x9km6.pdf (accessed on 08 September 2025).

- Verity Resources Limited. Resource upgrade drilling completed. In Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) Announcement dated 04 August 2025; Verity Resources Limited: Kew East, Australia, 2025; 7p. Available online: https://wcsecure.weblink.com.au/pdf/VRL/02974515.pdf (accessed on 08 September 2025).

- Verity Resources Limited. Historical drill validation study confirms high grade zones at Monument gold project. In Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) Announcement dated 12 September 2025; Verity Resources Limited: Kew East, Australia, 2025; 28p. Available online: https://wcsecure.weblink.com.au/pdf/VRL/02992609.pdf (accessed on 08 September 2025).

| Category | Data Type/Name | Source | Comments |

| Gold occurrences | Mines and mineral deposits (MINEDEX) | GSWA | Data available from DEMIRS Data and Software Centre: https://dasc.dmirs.wa.gov.au/ |

| MINEDEX operating mines map | |||

| Geology | 1:100,000 state interpreted bedrock geology of Western Australia | ||

| 1:500,000 interpreted bedrock geology of Western Australia | |||

| 1:100,000 geological series maps | |||

| 1:500,000 state regolith geology | |||

| In-house Eastern Yilgarn Craton geology map | SBM | Confidential dataset | |

| pmd*CRC 1:100,000 solid geology map, eastern Yilgarn Craton | [15] | Data or data links provided in quoted references | |

| Yilgarn Craton metamorphic facies map | [11,32] | ||

| Geochemistry | Yilgarn Craton εNd (juvenile crust) map | [33] | |

| Drilling | Mineral exploration drill holes (open file) | GSWA | Confidential dataset |

| Leonora drill hole database | SBM | https://dasc.dmirs.wa.gov.au/ | |

| Geophysics | 400 m Bouguer gravity merged grid of Western Australia 2020 version 1 | GSWA | Data available from MAGIX Online: https://geodownloads.dmp.wa.gov.au/downloads/geophysics/72203/, …/72204/ and …/72205/ |

| 40 m reduced to the pole (RTP) magnetic merged grid of Western Australia 2021 version 1 | |||

| Radiometric grids (80 m) of Western Australia | |||

| Remote Sensing | ALOS World 3D - 30 m (AW3D30) ALOS Global Digital Surface Model |

OpenTopography | Data available from https://opentopography.org/ |

| Sentinel-2 (blue, green, red and near-infrared (NIR) bands at 10 m and other bands at 20 m resolution) | European Space Agency |

Data available from https://dataspace.copernicus.eu |

|

Deposit Name |

Discovery (Year) |

Endowment (Moz Au) |

Absolute Age (Ma) | Geology & Mineralization |

| Paddington | 1894 | >11.7 | Unk | Principal host rock(s): granophyric qtz-dolerite (greenschist facies); Mineralization style(s): closely-spaced, 1 to 5 cm-wide, subhorizontal, sheeted gold and sulphide (apy > py, sp > gn)-bearing qtz-dol-ank-ab veins, and a 3 m-wide, steeply-dipping, laminated, gold- and sulfide (apy > py, ccp, gn > sp)-bearing qtz-cb vein; Alteration type(s): carbonatization, chloritization, sericitization, silicification, sulfidation (apy, py, po); Metal association: Note reported (Au-As?); Ore control(s): D2 kinematics and associated brittle-ductile structures; interaction of key structural elements (synclinal fold structure, location along the crustal-scale Bardoc Tectonic Zone), strong competency contrast between dolerite and surrounding ultramafic and sedimentary rocks |

| Gwalia | 1896 | >8.2 | 2755 | Principal host rock(s): mafic schist, basalt (± pillowed) (lower amphibolite facies); Mineralization style(s): variably deformed, millimeter- to meter-scale, laminated and typically tightly folded and boudinaged gold- and sulphide (py, po > ccp)-bearing qtz-cb veins; Alteration type(s): carbonatization, biotitization, sericitization, silicification, sulfidation (py); Metal association: Not reported; Ore control(s): D2 kinematics and associated ductile structures, interaction of key structural elements (mylonite zone, fold hinge of a large M-shaped fold, Poker/Gwalia Fault, bulge of the Raeside Batholith, proximity to crustal-scale Keith-Kilkenny fault system) |

| Mt Morgans | 1896 | >5.0 | 2650-2630 | Principal host rock(s): banded iron formation (BIF) (greenschist facies); Mineralization style(s): structurally controlled, disseminated gold-sulfide (py > ccp) in BIF and along the margins of qtz-cb veins; Alteration type(s): silicification, carbonatization, sulfidation (py > po, ccp, sp); Metal association: Not reported; Ore control(s): D4/5 kinematics and brittle(-ductile) structures, interaction of key structural elements (fault intersections, fold hinges developed on overturned anticlinal fold structure, dilational jog, proximity to crustal-scale Celia fault system), chemically reactive rock type (mag replacement by sulfides) |

| Tarmoola/King of the Hills | 1897 | >4.4 | 2650-2630 | Principal host rock(s): trondhjemite, komatiite (greenschist facies); Mineralization style(s): sets of conjugate, 20 cm to 2 m-wide, gold-, telluride-, sulfide (py, ccp, sp, gn)- and ± scheelite-bearing, laminated qtz-cb veins and breccias; Alteration type(s): silicification, carbonatization, sericitization, chloritization, albitization and sulfidation (py, ccp, sp, ga); Metal association: Au-Sb-Mo-W ± Bi; Ore control(s): D4/5 kinematics and associated brittle-ductile structures, interaction of key structural elements (proximity to local shear zones and crustal-scale Keith-Kilkenny fault system), strong competency contrast between trondhjemite and komatiite, fault-valve action; Note: Tarmoola/King of the Hills is the largest known granite-hosted gold deposit in the Yilgarn Craton |

| Thunderbox | 1999 | >4.4 | Unk | Principal host rock(s): porphyritic dacite (upper greenschist facies); Mineralization styles: structurally-controlled, disseminated gold-sulfide (apy, po > py, sp, gn) accumulations and mm- to cm-thick, boudinaged and folded gold- and sulfide (apy)-bearing qtz veins; Alteration styles: carbonatization, silicification, albitization and sulfidation (apy, po); Metal association: Not reported (Au-As?); Ore control(s): D4/5 kinematics and brittle-ductile structures, interaction of key structural elements (local fold axes, Thunderbox shear zone, proximity to crustal-scale Perseverance fault system), strong competency contrast between porphyritic dacite and enclosing sedimentary and mafic volcanic rocks |

| Apollo Hill | 1986 | >2.0 | Unk | Principal host rock(s): basalt (pillowed), dolerite, felsic volcaniclastic rocks; Mineralization style(s): Four sets of mm- to cm-thick, sheeted and stockwork-type, gold- and sulfide (py > ccp, sp, gn, po)-bearing qtz-cb veins; Alteration type(s): carbonatization, chloritization, sericitization, silicification, pyritization; Metal association: Not reported (Au-Ag-Cu-Pb-Zn?); Ore control(s): D4/5(?) kinematics and associated brittle-ductile structures, interaction of key structural elements (Apollo-Ra shear zone, proximity to crustal-scale Keith-Kilkenny fault system), strong competency contrast, lithological contacts |

| Aphrodite | 1996 | >1.6 | Unk | Principal host rock(s): volcaniclastic rocks, felsic to intermediate (dacitic) porphyries; Mineralization style(s): conjugate, mm- to cm-scale gold- and sulfide (py > apy)-bearing qtz veins and breccias; Alteration type(s): silicification, carbonatization, sericitization, biotitization and sulfidation (py > apy > gn, ccp, stb); Metal association: Not reported (Au-As-Sb?); Ore control(s): D2 kinematics and associated brittle-ductile structures; interaction of key structural elements (local fold axes and crenulations, location along the crustal-scale Bardoc Tectonic Zone), strong competency contrast, chemically reactive sedimentary rock |

| Ulysses | 1993 | >1.6 | Unk | Principal host rock(s): qtz-dolerite (sills), basalt; Mineralization style(s): stacked, shear zone-hosted, gold- and sulfide-bearing qtz veins; Alteration type(s): silicification, carbonatization, sericitization, albitization, sulfidation (py, po > ccp) ± biotitization, chloritization; Metal association: Not reported; Ore control(s): D4/5(?) kinematics and associated brittle-ductile structures; interaction of key structural elements (fault intersections with dolerite sills), strong competency contrast |

| Menzies | 1891 | >1.4 | Unk | Principal host rock(s): metasedimentary rock, basalt, amphibolite ± porphyritic granodiorite; Mineralization style(s): locally stacked, shear zone-hosted, gold- and sulfide (py > apy)-bearing qtz veins and zones of brecciation; Alteration type(s): biotitization, chloritization, sericitization, silicification, sulfidation (py, po) ± carbonatization; Metal association: Au-As; Ore control(s): D4/5(?) kinematics and associated brittle-ductile structures; interaction of key structural elements (shear fabric, proximity to Menzies shear zone, location along the crustal-scale Bardoc Tectonic Zone) |

| Wonder | 1890s | >0.9 | Unk | Principal host rock(s): syenogranite (Bundarra Batholith) with partially assimilated greenstone rafts (mafic roof pendants); Mineralization style(s): gold- and sulphide (py > ccp, gn)-bearing qtz veins; Alteration type(s): silicification, carbonatization, sericitization, propylitization (hem), sulphidation (py) ± chloritization; Metal association: Not reported; Ore control(s): D4/5(?) kinematics and associated brittle-ductile structures; interaction of key structural elements (local faults, granite margin, proximity to the crustal-scale Keith-Kilkenny fault system), strong competency contrast between granite and mafic greenstone rafts |

| Zoroastrian | 1894 | >0.6 | Unk | Principal host rock(s): granophyric dolerite; Mineralization style(s): steeply-dipping and flat-lying, gold- and sulphide (apy, py, po)-bearing qtz stockwork veins; Alteration type(s): silicification, carbonatization, sericitization, chloritization, sulphidation (apy, py, po); Metal association: Not reported; Ore control(s): D4/5(?) kinematics and associated brittle-ductile structures; interaction of key structural elements (narrow synclinal fold structure, constriction zone between two granite domes, location along the crustal-scale Bardoc Tectonic Zone), strong competency contrast between dolerite and surrounding sedimentary, mafic and ultramafic rocks |

|

Critical Processes |

Constituent Processes |

Targeting Criteria (Proxies) |

Rationale for Proxies |

Proxies Used for MPM |

| Source | Availability of energy to drive and sustain the mineral system | Source processes related to orogenic Au systems are cryptic in nature:

|

Broad consensus exists in terms of orogenic Au systems of the Yilgarn Craton being formed in convergent margin settings, particularly in accretionary orogens, which, if mineralised, involve the following ingredients [33,116,117]:

|

Proximity to:

|

| Availability of fertile Au source region | ||||

| Availability of melts and fluids to extract Au from source region | ||||

| Availability of ligands to enhance Au solubility | ||||

| Favorable geodynamic/tectonic (“ground-preparation”) history | ||||

| Transport | Fundamental translithospheric structures | First-order fault systems |

|

Proximity to:

|

| Crustal structures | Second-order fault systems |

|

||

| Regional folds |

|

|||

| Domes |

|

|||

| Greenstone constriction zones |

|

|||

| Late basins |

|

|||

| Proterozoic dolerite dyke swarms |

|

|||

| Trap | Transient catastrophic rock failure and concomitant structurally controlled, and highly focused fluid flow | Second- and higher-order faults |

|

|

| Fault irregularities Dilational or contractional bends/jogs Fault splays, tips and wings En-echelon fracture zones |

|

|||

| Structural intersections and intersection density |

|

|||

| Fold structures |

|

|||

| Ductile structures Boudinage Stretching lineation Deflections in schistosity |

|

|||

| Competency contrasts |

|

|||

| Lithological complexity |

|

|||

| Deposition | Physicochemical destabilization of Au-bearing fluids | Phase separation |

|

|

| Fluid-rock interaction |

|

|||

| Fluid mixing |

|

|||

| Preservation | Geodynamics | Tectonic setting, crustal depth and timing of Au deposit formation and post-Au deformation history |

|

Not used in this study:

|

| Peneplanation and climate | Peneplained, tectonically stable cratonic environments in (semi-) arid climate zones |

|

| Predictor Map | Pr (%) | Oa (%) | Nd | AUC |

| Proximity to known gold occurrences | 100 | 0 | Infinity | 1.000 |

| Proximity to greenstone belts | 69 | 31 | 2.230 | 0.965 |

| Proximity to domains of favorable metamorphic grade | 69 | 31 | 2.230 | 0.950 |

| Proximity to felsic to intermediate volcanic rocks | 59 | 41 | 1.440 | 0.948 |

| Proximity to regional gravity highs | 71 | 29 | 2.450 | 0.931 |

| Proximity to mafic-ultramafic volcanic rocks | 69 | 31 | 2.230 | 0.922 |

| Proximity to basement granitoids | 71 | 29 | 2.450 | 0.858 |

| Proximity to ‘high mag units’ | 66 | 34 | 1.940 | 0.852 |

| Proximity to areas of demagnetization | 62 | 38 | 1.630 | 0.851 |

| Proximity to subsidiary faults | 66 | 34 | 1.940 | 0.833 |

| Proximity to remotely sensed alteration systems | 72 | 28 | 2.570 | 0.824 |

| Proximity to lithological contacts | 68 | 32 | 2.120 | 0.800 |

| Proximity to fold hinges | 59 | 41 | 1.440 | 0.794 |

| Proximity to internal granitoids | 64 | 36 | 1.770 | 0.788 |

| Density of principal faults | 61 | 39 | 1.560 | 0.786 |

| Proximity to principal faults | 64 | 36 | 1.770 | 0.778 |

| Density of lithological contacts | 58 | 42 | 1.380 | 0.758 |

| Density of ENE-WSW-striking gravity ridges | 63 | 37 | 1.700 | 0.746 |

| Density of NNW-SSE-striking gravity ridges | 59 | 41 | 1.440 | 0.715 |

| Density of principal fault intersections | 59 | 41 | 1.440 | 0.700 |

| Proximity to siliciclastic and sedimentary rocks | 64 | 36 | 1.770 | 0.691 |

| Density of ENE-WSW-striking gravity lineaments | 59 | 41 | 1.440 | 0.669 |

| Proximity to flanks of granitoid bodies | 59 | 41 | 1.440 | 0.639 |

| Density of NNW-SSE-striking gravity lineaments | 56 | 44 | 1.270 | 0.611 |

| Proximity to domains of juvenile crust (εNd-values of -0.2 to 2.4) | 52 | 48 | 1.080 | 0.611 |

| Proximity to domains of high K/Th values (≥95th percentile) | 55 | 45 | 1.220 | 0.560 |

| Proximity to Proterozoic dolerite dykes | 52 | 48 | 1.080 | 0.537 |

| Density of Proterozoic dolerite dykes | 51 | 49 | 1.040 | 0.515 |

| Predictor Map | Entropy (e) | Normalized entropy value (h) | Weight (W) |

| Density of lithological contacts | 6095.6771 | 0.0106 | 0.9894 |

| Proximity to basement granitoids | 7645.2808 | 0.0133 | 0.9867 |

| Proximity to felsic to intermediate volcanic rocks | 8618.7458 | 0.0150 | 0.9850 |

| Density of principal fault intersections | 14307.6455 | 0.0249 | 0.9750 |

| Density of Proterozoic dolerite dykes | 15560.7472 | 0.0271 | 0.9729 |

| Density of principal faults | 15964.4654 | 0.0278 | 0.9722 |

| Proximity to greenstone belts | 16756.0867 | 0.0292 | 0.9708 |

| Proximity to domains of favorable metamorphic grade | 17192.3563 | 0.0300 | 0.9700 |

| Proximity to regional gravity highs | 17325.3546 | 0.0302 | 0.9698 |

| Density of NNW-SSE-striking gravity lineaments | 18651.1160 | 0.0325 | 0.9675 |

| Density of ENE-WSW-striking gravity ridges | 20723.5017 | 0.0361 | 0.9639 |

| Density of ENE-WSW-striking gravity lineaments | 20805.6584 | 0.0363 | 0.9637 |

| Density of NNW-SSE-striking gravity ridges | 21253.2799 | 0.0371 | 0.9629 |

| Proximity to mafic-ultramafic volcanic rocks | 21418.1640 | 0.0373 | 0.9627 |

| Proximity to fold hinges | 23135.5471 | 0.0403 | 0.9597 |

| Proximity to siliciclastic and sedimentary rocks | 23344.8807 | 0.0407 | 0.9593 |

| Proximity to domains of high K/Th values (≥95th percentile) | 23608.4979 | 0.0412 | 0.9588 |

| Proximity to domains of juvenile crust (εNd-values of -0.2 to 2.4) | 23831.9069 | 0.0415 | 0.9585 |

| Proximity to internal granitoids | 24255.2574 | 0.0423 | 0.9577 |

| Proximity to lithological contacts | 24480.4544 | 0.0427 | 0.9573 |

| Proximity to remotely sensed alteration systems | 25084.6743 | 0.0437 | 0.9563 |

| Proximity to ‘high mag units’ | 25400.9016 | 0.0443 | 0.9557 |

| Proximity to known gold occurrences | 25649.8157 | 0.0447 | 0.9553 |

| Proximity to flanks of granitoid bodies | 25836.8422 | 0.0450 | 0.9550 |

| Proximity to areas of demagnetization | 25900.6011 | 0.0452 | 0.9548 |

| Proximity to Proterozoic dolerite dykes | 26630.7561 | 0.0464 | 0.9536 |

| Proximity to subsidiary faults | 26876.2032 | 0.0469 | 0.9531 |

| Proximity to principal faults | 27249.1575 | 0.0475 | 0.9525 |

| Competent Predictor Maps | Parameters | ||||||

| Pm | Pn | 100-Pm | 100-Pn | TPr | FPr | Op | |

| Proximity to known gold occurrences (DC1) | 100 | 46 | 0 | 54 | 1 | 0.46 | 0.54 |

| Proximity to regional gravity highs (DC2) | 71 | 43 | 29 | 57 | 0.71 | 0.43 | 0.28 |

| Proximity to basement granitoids (DC3) | 71 | 43 | 29 | 57 | 0.71 | 0.43 | 0.28 |

| Proximity to greenstone belts (DC4) | 69 | 42 | 31 | 58 | 0.69 | 0.42 | 0.27 |

| Proximity to domains of favorable metamorphic grade (DC5) | 69 | 43 | 31 | 57 | 0.69 | 0.43 | 0.26 |

| Proximity to mafic-ultramafic volcanic rocks (DC6) | 69 | 44 | 31 | 56 | 0.69 | 0.44 | 0.25 |

| Proximity to subsidiary faults (DC7) | 66 | 42 | 34 | 58 | 0.66 | 0.42 | 0.24 |

| Proximity to remotely sensed alteration systems (DC8) | 72 | 48 | 28 | 52 | 0.72 | 0.48 | 0.24 |

| Proximity to ‘high mag units’ (DC9) | 66 | 43 | 34 | 57 | 0.66 | 0.43 | 0.23 |

| Proximity to principal faults (DC10) | 64 | 43 | 36 | 57 | 0.64 | 0.43 | 0.21 |

| Proximity to lithological contacts (DC11) | 68 | 47 | 32 | 53 | 0.68 | 0.47 | 0.21 |

| Density of ENE-WSW-striking gravity ridges (DC12) | 63 | 45 | 37 | 55 | 0.63 | 0.45 | 0.18 |

| Proximity to internal granitoids (DC13) | 64 | 47 | 36 | 53 | 0.64 | 0.47 | 0.17 |

| Density of principal faults (DC14) | 61 | 45 | 39 | 55 | 0.61 | 0.45 | 0.16 |

| Proximity to siliciclastic and sedimentary rocks (DC15) | 64 | 48 | 36 | 52 | 0.64 | 0.48 | 0.16 |

| Proximity to areas of demagnetization (DC16) | 62 | 46 | 38 | 54 | 0.62 | 0.46 | 0.16 |

| Proximity to fold hinges (DC17) | 59 | 47 | 41 | 53 | 0.59 | 0.47 | 0.12 |

| Proximity to felsic to intermediate volcanic rocks (DC18) | 59 | 48 | 41 | 52 | 0.59 | 0.48 | 0.11 |

| Density of NNW-SSE-striking gravity ridges (DC19) | 59 | 48 | 41 | 52 | 0.59 | 0.48 | 0.11 |

| Density of ENE-WSW-striking gravity lineaments (DC20) | 59 | 48 | 41 | 52 | 0.59 | 0.48 | 0.11 |

| Density of principal fault intersections (DC21) | 59 | 48 | 41 | 52 | 0.59 | 0.48 | 0.11 |

| Proximity to flanks of granitoid bodies (DC22) | 59 | 48 | 41 | 52 | 0.59 | 0.48 | 0.11 |

| Density of lithological contacts (DC23) | 58 | 49 | 42 | 51 | 0.58 | 0.49 | 0.09 |

| Density of NNW-SSE-striking gravity lineaments (DC24) | 56 | 49 | 44 | 51 | 0.56 | 0.49 | 0.07 |

| Proximity to domains of juvenile crust (DC25) | 52 | 47 | 48 | 53 | 0.52 | 0.47 | 0.05 |

| Proximity to domains of high K/Th values (DC26) | 55 | 50 | 45 | 50 | 0.55 | 0.5 | 0.05 |

| Proximity to Proterozoic dolerite dykes (DC27) | 52 | 50 | 48 | 50 | 0.52 | 0.5 | 0.02 |

| Density of Proterozoic dolerite dykes (DC28) | 51 | 51 | 49 | 49 | 0.51 | 0.51 | 0 |

| Fuzzy Gamma | Geometric Average | Improved Index Overlay | BWM-SAW | RF | |

| Pm (Hits) | 77 | 78 | 79 | 88 | 88 |

| Pn (False Alarms) | 42 | 43 | 42 | 41 | 36 |

| 100-Pm (Misses) | 23 | 22 | 21 | 12 | 12 |

| 100-Pn (Correct Rejection) | 58 | 57 | 58 | 59 | 64 |

| True Positive Rate (TPr) | 0.77 | 0.78 | 0.79 | 0.88 | 0.88 |

| False Positive Rate (FPr) | 0.42 | 0.43 | 0.42 | 0.41 | 0.36 |

| Overall Performance (Op) | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.37 | 0.47 | 0.52 |

| Parameters | GSWA Database | SBM Database | Comments |

| Number of drill holes | 231,760 | 77,675 | |

| Main hole type | |||

| RC | 84,078 (36%) | 19,874 (26%) | Only 39% of all drill holes completed in the study area are RC or DD holes whereas 56% represent geochemical drill holes comprised of RAB, AC and AUG holes. |

| RAB | 62,377 (27%) | 43,180 (56%) | |

| AC | 52,905 (23%) | 8875 (11%) | |

| AUG | 14,276 (6%) | 889 (1%) | |

| DD | 7043 (3%) | 1827 (2%) | |

| Other | 11,081 (5%) | 3030 (4%) | |

| Hole depth—all drill holes | |||

| Min | 0.0 m | 0.0 m | The median value demonstrates that 50% of all drill holes completed in the study area have hole lengths of only 39 m or less. |

| Max | 2895.6 m | 2895.6 m | |

| Median | 39.0 m | 36.0 m | |

| Mean | 50.5 m | 53.9 m | |

| Hole depth—RC holes | |||

| Min | 0.0 m | 0.0 m | Of the 80,078 RC holes in the GSWA database, 31,713 (~40%) targeted Au whilst 32,666 (~41%) targeted Ni ± Co; the remaining holes targeted mostly base metals ± Au |

| Max | 1043.1 m | 624.6 m | |

| Median | 41.0 m | 69.0 m | |

| Mean | 53.1 m | 81.3 m | |

| Hole depth—DD holes | |||

| Min | 0.0 m | 6.0 m | Of the 7043 DD holes in the GSWA database, 3511 (~50%) targeted Au ± Ag, Ni; the remaining holes targeted mostly base metals ± Au |

| Max | 2895.6 m | 2895.6 m | |

| Median | 211.9 m | 220.0 m | |

| Mean | 292.8 m | 403.0 m |

| Target ID & Ranking | Name | Rationale | Exploration & Ownership |

| #1 | Dingo | Lithostructural target comprising a cluster of poorly tested intrusions of the McAuliffe Well Syenite; partially covered by Lake Raeside; hosts Dingo and Bull Terrier Au occurrences; proximal to 1st order Keith-Kilkenny fault system; located along a NNW-SSE-trending gravity ridge | Shallow saprolite drilling only although open-file drill hole data appear to be incomplete; best historic drill intercept: 1.00 m @ 12.28 g/t Au; disjointed ownership |

| #2 | Westralia North | Lithostructural target comprising BIF units and syenite intrusions; Korong and Akicia Au occurrences; proximal to 1st order Celia fault system; located along a NNW-SSE gravity ridge; along strike from the Mt Morgans Au deposit | No deep drilling >150 m vertical; best historic drill intercept: 6.70 m @ 13.15 g/t Au; disjointed ownership |

| #3 | Mt Boyce | Lithostructural target; largely soil covered; no reported Au occurrences in 2021; proximal to 1st order Keith-Kilkenny fault system; located along a NNW-SSE-trending gravity ridge | No deep drilling >100 m vertical; best historic drill intercept: 2.00 m @ 34.50 g/t Au |

| #4 | Mt Redcastle | Lithostructural target in ‘nose region’ of a large granite dome and comprising internal granitoids; hosts several known Au occurrences; proximal to unnamed 2nd order fault system; located along NW-SE-trending gravity ridge | No deep drilling >100 m; disjointed ownership |

| #5 | Mt Remarkable | Lithostructural target covering part of the Pig Well Basin; no reported Au occurrences in 2021; proximal to 1st order Keith-Kilkenny fault system; located along a NNW-SSE-trending gravity ridge | Drilling is mostly associated with the Marvellous Au occurrence; best historic drill intercept: 82.00 m @ 0.83 g/t Au; disjointed ownership; partly located within an extensive registered site of Aboriginal cultural heritage |