Submitted:

17 October 2025

Posted:

17 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Data and Methods

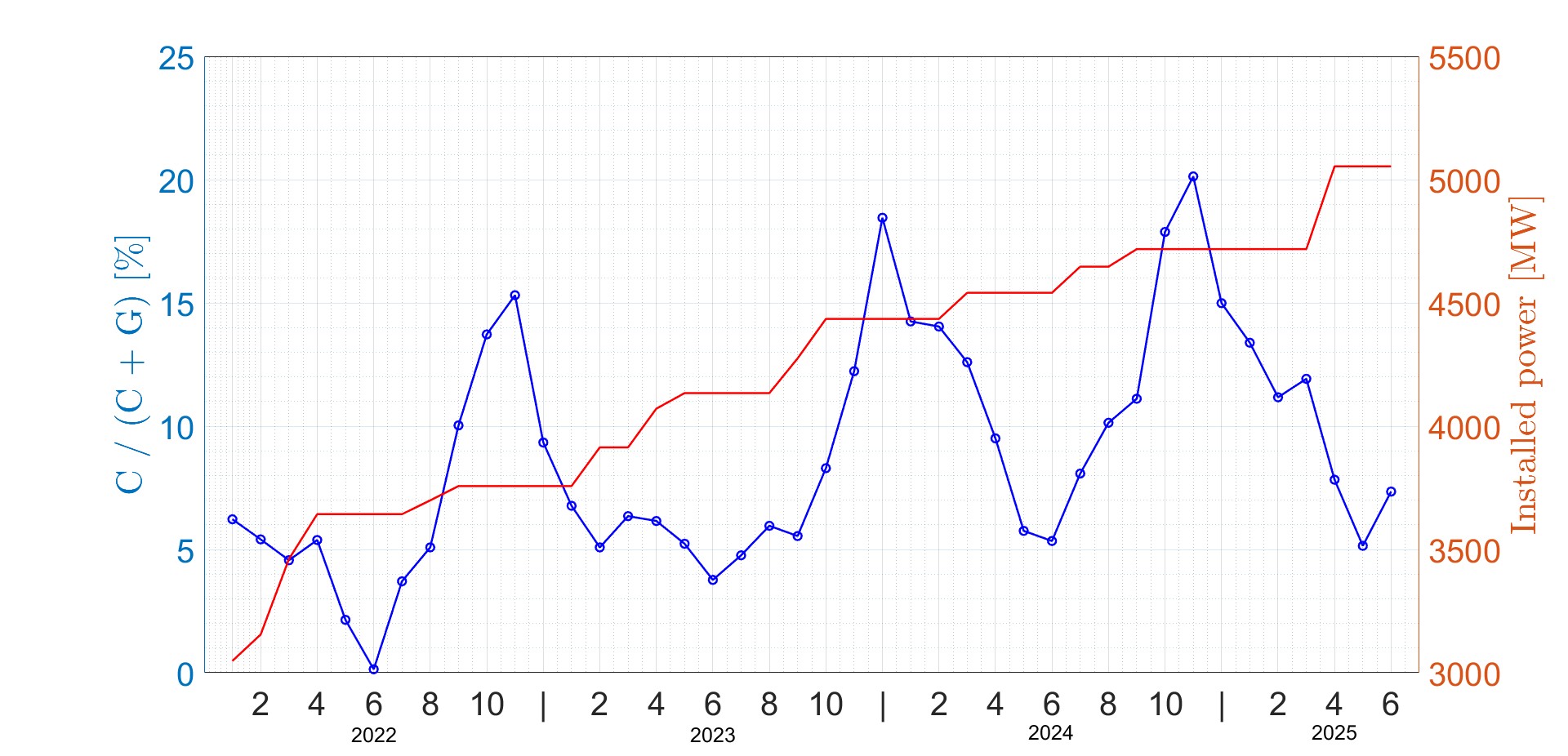

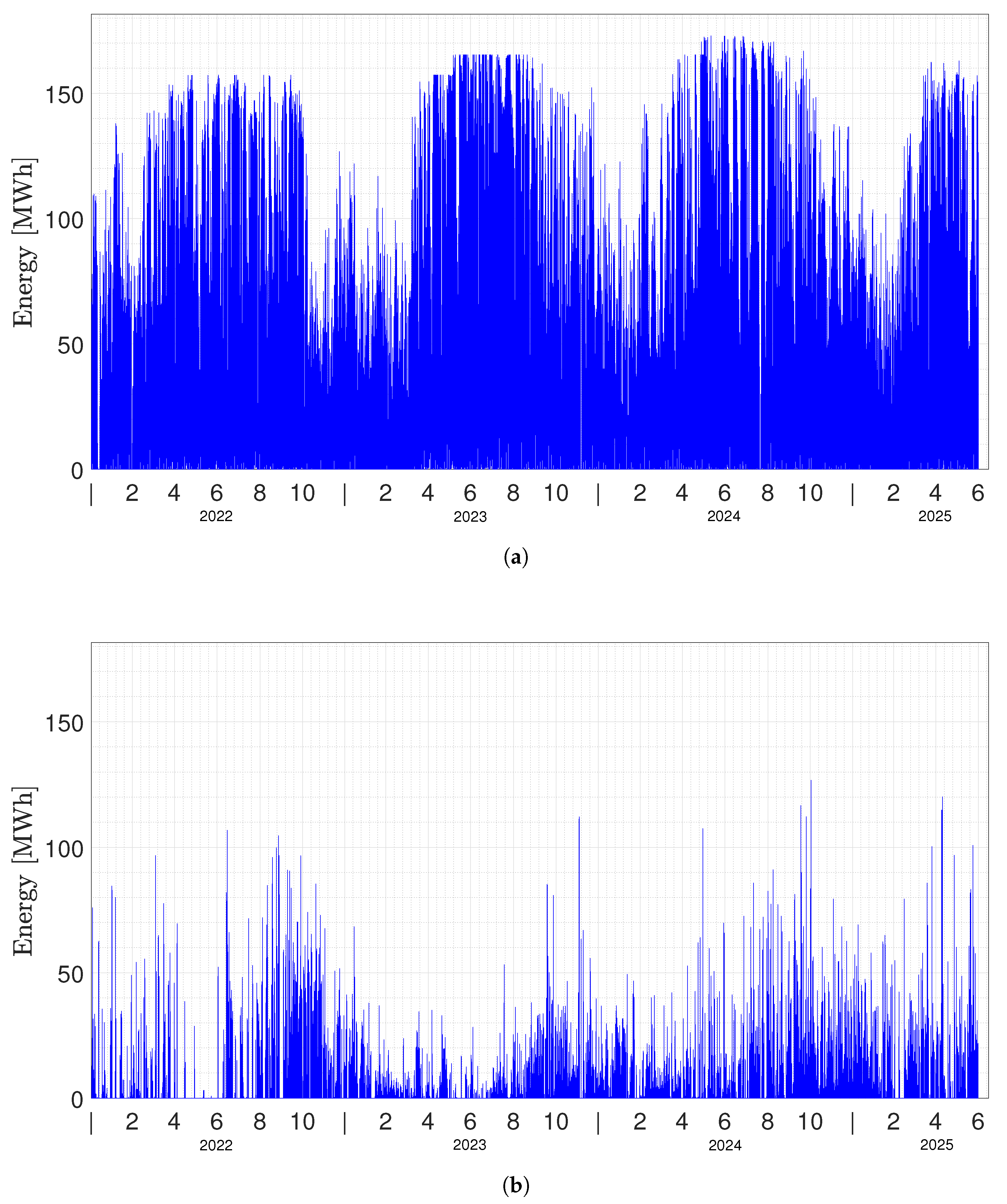

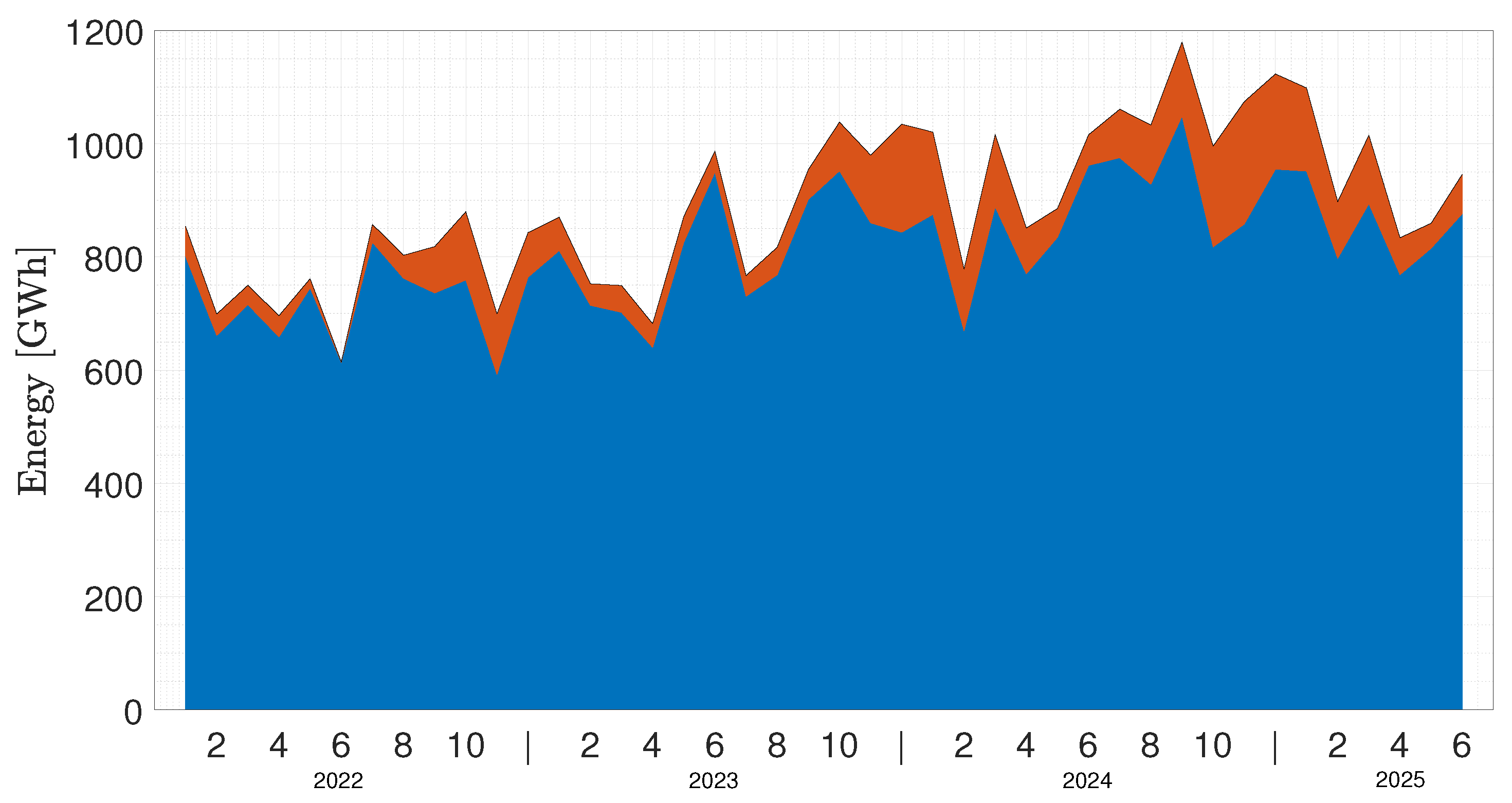

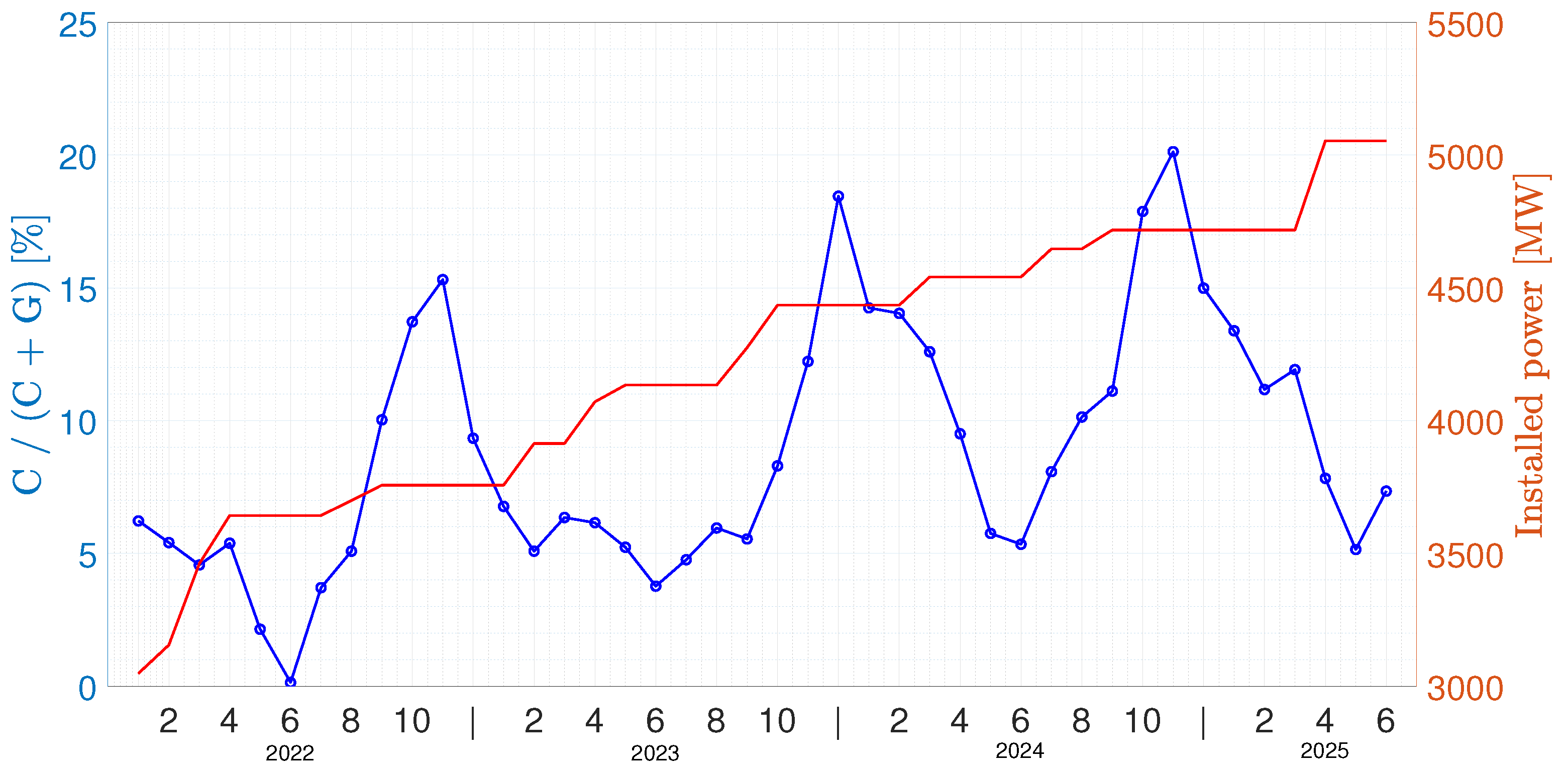

2.1. Generation and Curtailment

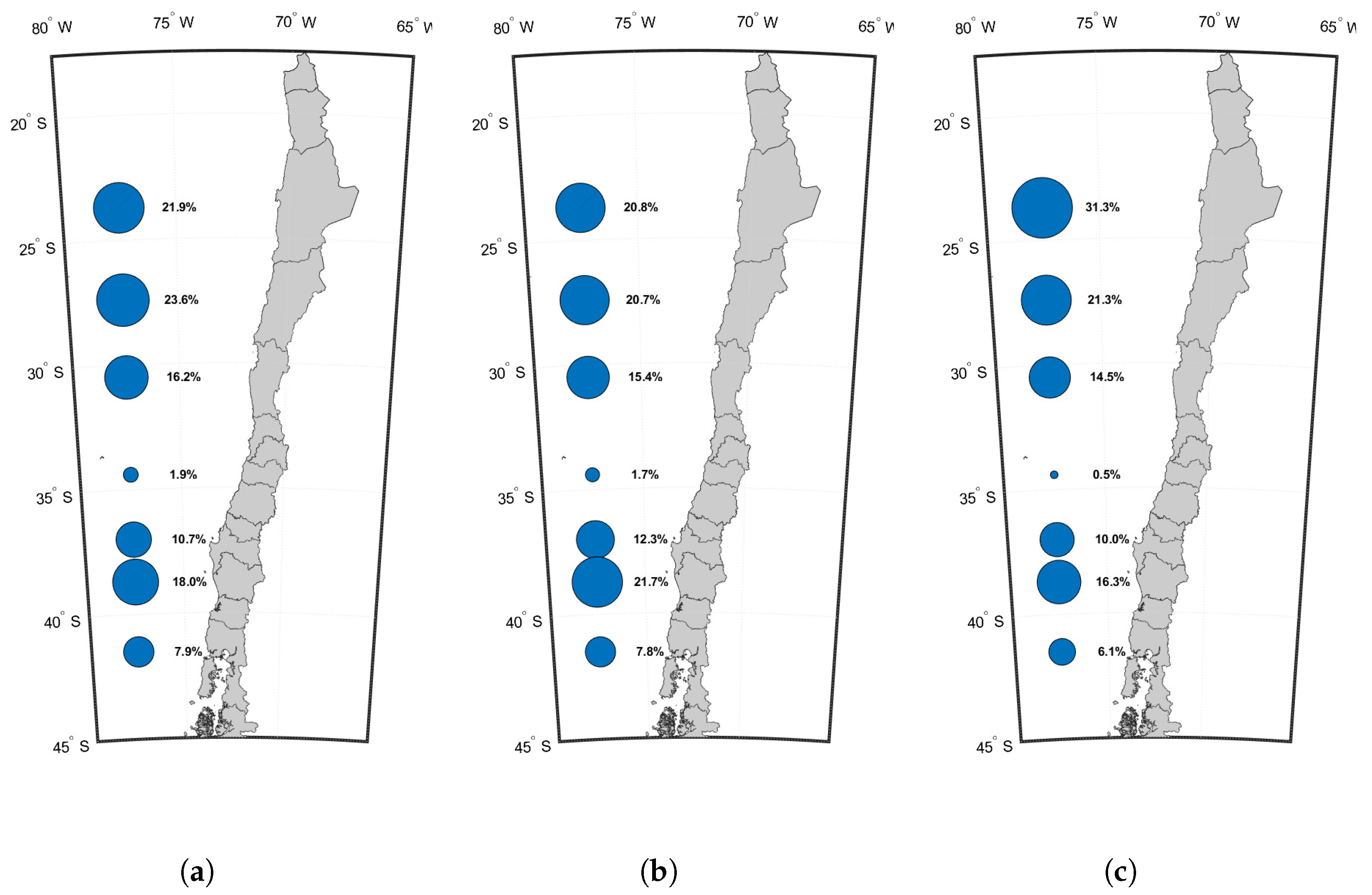

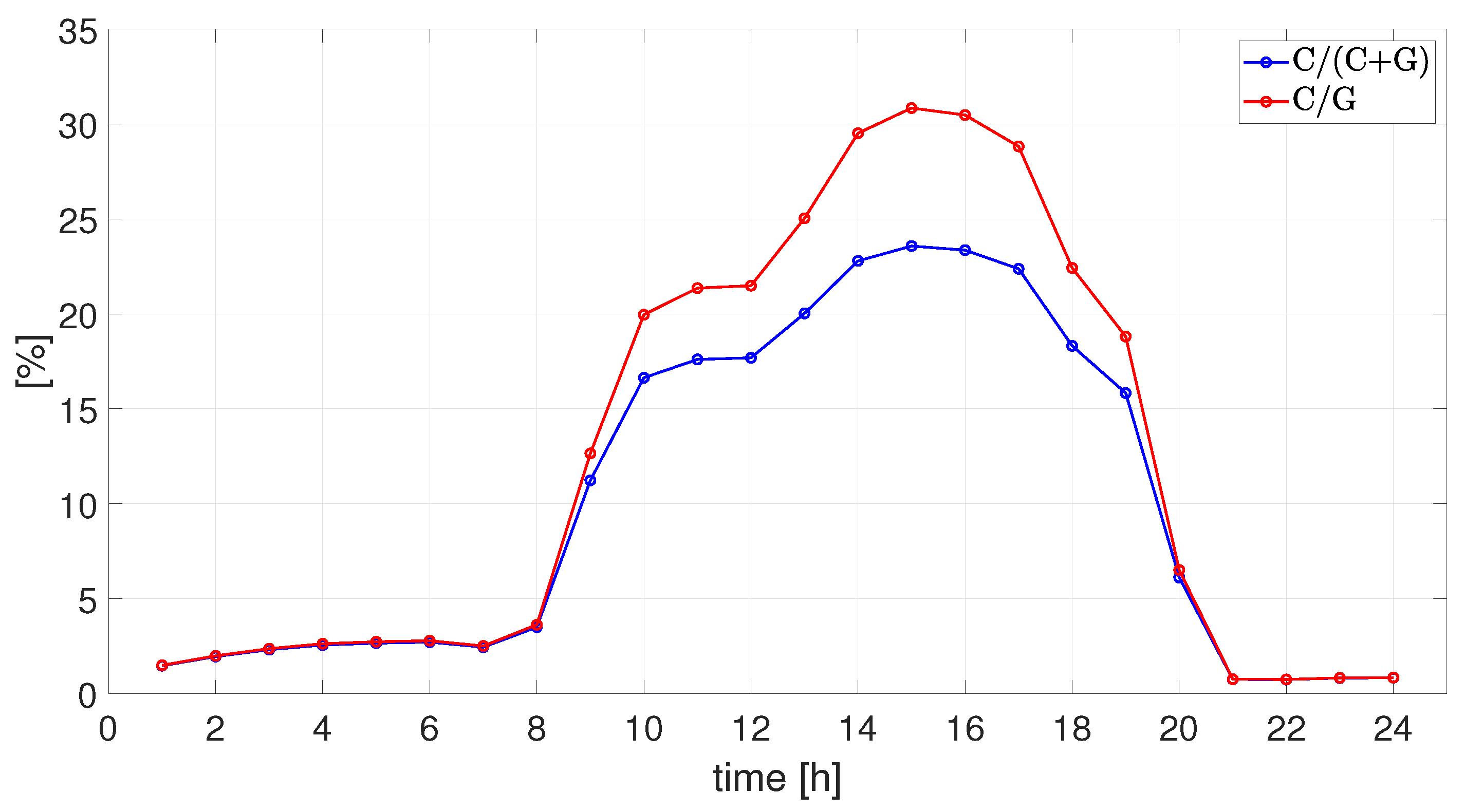

2.2. Methodology

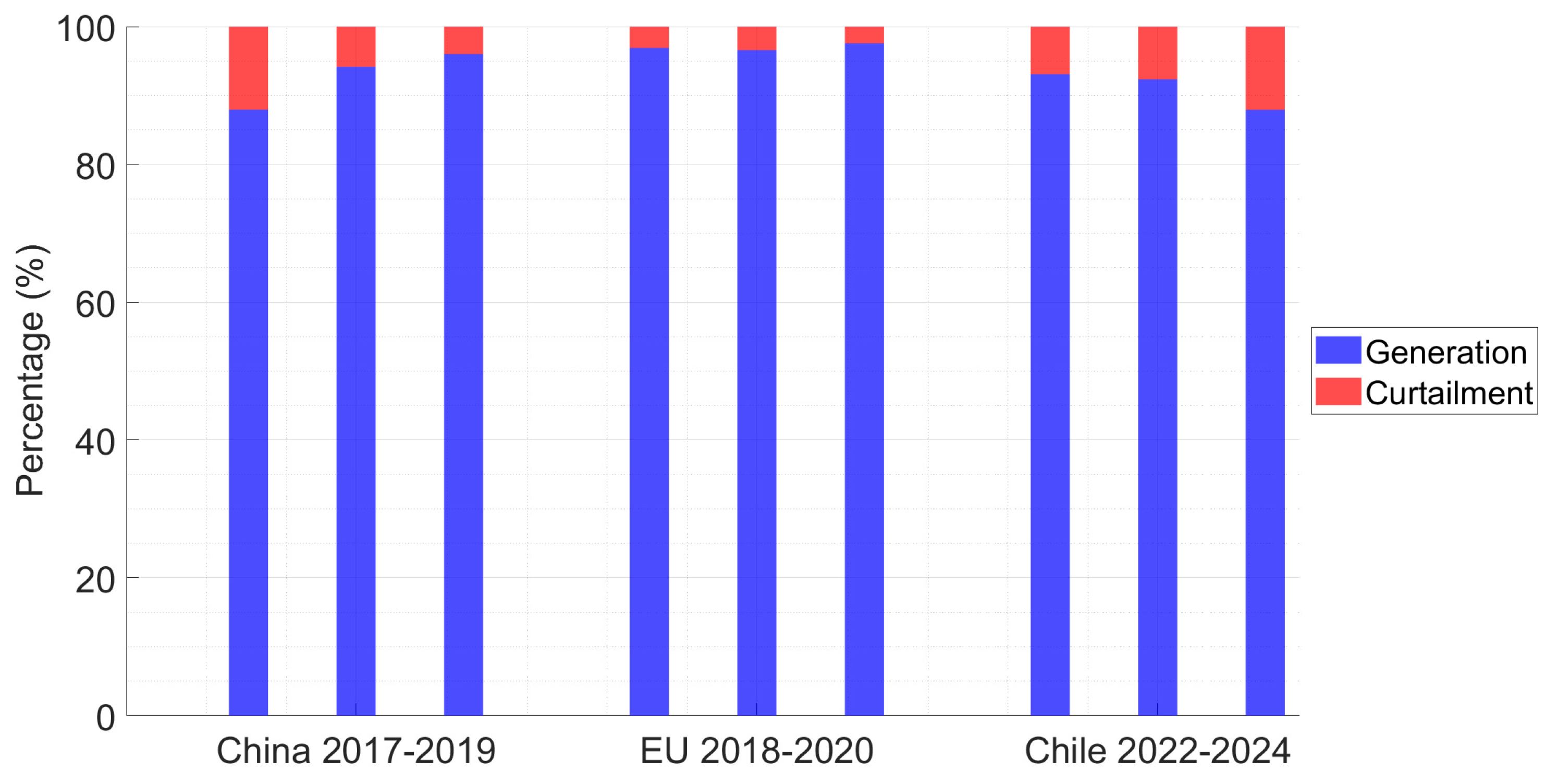

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Frew, B.; Sergi, B.; Denholm, P.; Cole, W.; Gates, N.; Levie, D.; Margolis, R. The curtailment paradox in the transition to high solar power systems. Joule 2021, 5, 1143–1167. [CrossRef]

- Laimon, M. Renewable energy curtailment: A problem or an opportunity? Results in Engineering 2025, p. 104925. [CrossRef]

- Bird, L.; Lew, D.; Milligan, M.; Carlini, E.M.; Estanqueiro, A.; Flynn, D.; Gomez-Lazaro, E.; Holttinen, H.; Menemenlis, N.; Orths, A.; et al. Wind and solar energy curtailment: A review of international experience. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2016, 65, 577–586. [CrossRef]

- O’Shaughnessy, E.; Cruce, J.R.; Xu, K. Too much of a good thing? Global trends in the curtailment of solar PV. Solar Energy 2020, 208, 1068–1077. [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, Y.; Bird, L.; Carlini, E.M.; Estanqueiro, A.; Flynn, D.; Forcione, A.; Lázaro, E.G.; Higgins, P.; Holttinen, H.; Lew, D.; et al. International comparison of wind and solar curtailment ratio. In Proceedings of the In 14th International Workshop on Large-Scale Integration of Wind Power into Power Systems as well as on Transmission Networks for Offshore Wind Farms. Brussels, Belgium, 2015.

- Yasuda, Y.; Bird, L.; Carlini, E.M.; Eriksen, P.B.; Estanqueiro, A.; Flynn, D.; Fraile, D.; Lázaro, E.G.; Martín-Martínez, S.; Hayashi, D.; et al. CE (curtailment–Energy share) map: An objective and quantitative measure to evaluate wind and solar curtailment. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2022, 160, 112212. [CrossRef]

- Prol, J.L.; Zilberman, D. No alarms and no surprises: Dynamics of renewable energy curtailment in California. Energy Economics 2023, 126, 106974. [CrossRef]

- Odeh, R.P.; Watts, D. Impacts of wind and solar spatial diversification on its market value: A case study of the Chilean electricity market. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2019, 111, 442–461. [CrossRef]

- Coordinador Eléctrico Nacional (CEN), Gobierno de Chile. Reporte energético marzo, 2024. Last accessed 20.12.24 Access here.

- Ministerio de Energía, Chile. Reporte de proyectos en Construcción e Inversión en el Sector Energía mes de julio, 2024. División de Desarrollo de Proyectos Unidad de Acompañamiento de Proyectos. Last accessed 14.10.25 Access here.

- Serra, P. Chile’s electricity markets: Four decades on from their original design. Energy Strategy Reviews 2022, 39, 100798. [CrossRef]

- Acosta, K.; Salazar, I.; Saldaña, M.; Ramos, J.; Navarra, A.; Toro, N. Chile and its potential role among the most affordable green hydrogen producers in the world. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2022, 10, 890104. [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, L.E.; Ito, K.; Reguant, M. The investment effects of market integration: Evidence from renewable energy expansion in Chile. Econometrica 2023, 91, 1659–1693. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Squella, A.; Muñoz, M.; Toledo, M.; Yanine, F. Techno-economic assessment of a green hydrogen production plant for a mining operation in Chile. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2025, 112, 531–543. [CrossRef]

- Losada, A.M.I. Green hydrogen: Chances and barriers for the Energiewende in Chile. Science Talks 2022, 4, 100088. [CrossRef]

- Chavez-Angel, E.; Castro-Alvarez, A.; Sapunar, N.; Henríquez, F.; Saavedra, J.; Rodríguez, S.; Cornejo, I.; Maxwell, L. Exploring the potential of green hydrogen production and application in the antofagasta region of Chile. Energies 2023, 16, 4509. [CrossRef]

- Osorio-Aravena, J.C.; Aghahosseini, A.; Bogdanov, D.; Caldera, U.; Ghorbani, N.; Mensah, T.N.O.; Khalili, S.; Muñoz-Cerón, E.; Breyer, C. The impact of renewable energy and sector coupling on the pathway towards a sustainable energy system in Chile. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021, 151, 111557. [CrossRef]

- Parrado, C.; Fontalvo, A.; Ordóñez, J.; Girard, A. Optimizing dispatch strategies for CSP plants: A Monte Carlo simulation approach to maximize annual revenue in Chile’s renewable energy sector. Energy 2025, 317, 134551. [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Renewable Energy Market Update: Outlook for 2023 and 2024, 2023. Last accessed 08.10.2025.

- Ember. Reducing Curtailment in Chile: Key to Unlocking the Full Potential of Renewable Energy, 2025. Last accessed 07.10.2025.

- Zhao, H.; Cui, C.; Zhang, Z. Assessing the dynamics of power curtailment in China: Market insights from wind, solar, and nuclear energy integration. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2025, 118, 209–216. [CrossRef]

- Phivos, T.; Rogiros, T.; Petros, A.; Charalambides, A. RES curtailments in Cyprus: A review of technical constraints and solutions. Solar Energy Advances 2025, p. 100097. [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Ma, J.; Zhu, M.; Khan, T. Advancements in energy storage technologies: Implications for sustainable energy strategy and electricity supply towards sustainable development goals. Energy Strategy Reviews 2025, 59, 101710. [CrossRef]

- Enasel, E.; Dumitrascu, G. Storage solutions for renewable energy: A review. Energy Nexus 2025, p. 100391. [CrossRef]

- Le Coq, C.; Bennato, A.R.; Duma, D.; Lazarczyk, E. Flexibility in the Energy Sector. Technical report, Centre on Regulation in Europe (CERRE), 2025. Last accessed 14.10.25 Access here.

- Travaglini, R.; Superchi, F.; Bianchini, A. Mitigating curtailments in offshore wind energy: A comparative analysis of new and second-life battery storage solutions. Journal of Cleaner Production 2025, 519, 146055. [CrossRef]

- Coordinador Eléctrico Nacional (CEN), Gobierno de Chile. Operación: Generación Real, 2022-2025. Last accessed 12.09.25 Access here.

- Coordinador Eléctrico Nacional (CEN), Gobierno de Chile. Operación: Reducciones de Generación Renovable, 2022-2025. Last accessed 12.09.25 Access here.

- Coordinador Eléctrico Nacional (CEN), Gobierno de Chile. Infotécnica, 2024. Last accessed 28.12.24 Access here.

- Superintendencia del Medio Ambiente, Gobierno de Chile. Sistema Nacional de INformación de Fiscalización Ambiental (SNIFA), 2024. Last accessed 28.12.24 Access here.

- Micheli, L.; Soria-Moya, A.; Talavera, D.L.; Abbasi, B.; Fernández, E.F. Energy and economic implications of photovoltaic curtailment: Current status and future scenarios. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments 2025, 81, 104414. [CrossRef]

- Fotis, G.; Maris, T.I.; Mladenov, V. Risks, Obstacles and Challenges of the Electrical Energy Transition in Europe: Greece as a Case Study. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5325. [CrossRef]

- Spiru, P.; Simona, P.L. Wind energy resource assessment and wind turbine selection analysis for sustainable energy production. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 10708. [CrossRef]

- Albatayneh, A.; AbuAlRous, R.; Kay, M.; Abdallah, R.; Juaidi, A.; García-Cruz, A.; Manzano-Agugliaro, F. Wind farm capacity factor forecasting: An Australian case study. Energy Nexus 2025, p. 100422. [CrossRef]

- Abed, K.; El-Mallah, A. Capacity factor of wind turbines. Energy 1997, 22, 487–491. [CrossRef]

- Benalcazar, P.; Komorowska, A. Techno-economic analysis and uncertainty assessment of green hydrogen production in future exporting countries. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2024, 199, 114512. [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Q.; Zeng, X.; Lin, B. Mitigating wind curtailment risk in China: The impact of subsidy reduction policy. Applied energy 2024, 368, 123493. [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Renewables 2017: Analysis and Forecast to 2022. Technical report, International Energy Agency (IEA), 2017. Last accessed 14.10.2025 Access here.

- Lewis, J.I. Wind energy in China: Getting more from wind farms. Nature Energy 2016, 1, 1–2. [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, P.B. The transition of the Danish power system from a fossil fueled system to presently having 40% wind penetration. In Proceedings of the In Grand Renewable Energy Conference, Yokohama, Japan, June 2018.

- Martín-Martínez, S.; Lorenzo-Bonache, A.; Honrubia-Escribano, A.; Cañas-Carretón, M.; Gómez-Lázaro, E. Contribution of wind energy to balancing markets: The case of Spain. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Energy and Environment 2018, 7, e300. [CrossRef]

- Coordinador Eléctrico Nacional (CEN), Gobierno de Chile. Propuesta final de expansión de la transmisión: Proceso de planificación de la transmisión, 2025. Gerencia planificación y desarrollo de la red. Last accessed 05.10.2025 Access here.

- American Clean Power Association. Clean Power Annual Market Report 2021, 2022. Last accessed 08.10.2025 Access here.

- Garcia-Sanz, M.; Marden, M.; Cvetkovic, I.; Oh, H.; LoCicero, E.; Khalid, S. Grid Fragility, Blackouts, and Control Co-Design Solutions. Advanced Control for Applications: Engineering and Industrial Systems 2025, 7, e70022. [CrossRef]

- Flores, E.A.; Curi, V.T.; Mattos, S.M.T.; Cayllahua, E.C.; Quezada, P.R.Q. Distributed Generation as a Complement to the Reliability of Electricity Supply: For Peruvian Social Economic Development. Centro Sur 2025, 9, 15–26. [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Energía, Chile. Decreto 13 Exento, Energía, 2025. Last accessed 08.10.2025 Access here.

| Item | information |

|---|---|

| ID | 1 |

| wind park name | Tchamma |

| Region, code | Antofagasta, AN |

| City | Calama |

| Net effective power, NEP | 171.78 MW |

| east coordinate, UTMWGS84 | 492341 |

| north coordinate, UTMWGS84 | 7511625 |

| Officially operative since | 21.02.2022 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).