1. Introduction

Traditional psychiatric practice has long conceptualized mental disorders as discrete clinical entities with distinct etiologies, symptoms, and treatment approaches. However, mounting evidence suggests that this categorical framework may insufficiently capture the underlying biological reality of psychiatric pathology. Instead, an emerging body of research indicates that psychiatric disorders may be better understood as manifestations of accelerated aging processes that compromise neural and systemic functions across multiple domains.

Geropsychosis, defined as psychiatric symptoms arising from age-related cellular and molecular changes in post-pubescent individuals, represents a fundamental reconceptualization of mental disorders. This framework builds upon the novel Conglomerate Theory of Aging, which proposes that the inexorable accumulation of metals, advanced glycation end products (AGEs), advanced lipoxidation end products (ALEs), and their hybrid complexes drives synergistic, self-reinforcing feedback loops that accelerate systemic decline (Nelson-Goedert, 2025).

These mechanistic foundations rest upon well-established hallmarks of aging, as they demonstrate noteworthy convergence with psychiatric pathology. Cellular senescence, characterized by permanent growth cessation and the secretory phenotype of inflammatory mediators, accumulates disproportionately in individuals with psychiatric disorders and correlates with treatment resistance (Diniz et al., 2022). Neuroinflammation creates a proinflammatory state that sensitizes the aging brain to produce inconsistent responses to stress and immune stimuli (Dilger & Johnson, 2008).

Collectively, these processes point towards a comprehensive neurological phenotype of aging, and neuroimaging studies consistently demonstrate advanced brain aging in patients with major depressive disorder, with brains appearing significantly older than their chronological age (Han et al., 2021). Longitudinal research following individuals from birth through midlife reveals that those with higher general psychopathology scores exhibit accelerated biological aging equivalent to approximately 5.3 years of additional aging between ages 26 and 45 (Wertz et al., 2021). Based on these findings, researchers may glean that psychiatric disorders are not merely subjective or experiential phenomena but represent fundamental disruptions to the biological aging process.

The conceptual framework of geropsychosis extends beyond identifying parallels between aging and psychiatric disorders to propose a mechanistic understanding of how aging processes directly constitute psychiatric symptomatology. This approach offers several potential advantages over traditional psychiatric frameworks. First, it provides a unifying biological foundation that can explain the following: the heterogeneity of psychiatric presentations, the common comorbidity patterns between different mental health conditions, and the frequent co-occurrence of psychiatric and physical health problems. Second, it offers a plausibly more granular explanation for why certain individuals develop psychiatric disorders while others do not, based on their individual susceptibility to aging-related cellular dysfunction. Third, it suggests using novel therapeutic approaches that target the underlying aging mechanisms rather than managing psychiatric symptoms in isolation. This provides the avenue for testing geroscience-based interventions, including mitochondrial therapeutics, anti-inflammatory agents, and comprehensive nutritional protocols designed to address the root causes of psychiatric pathology.

Figure 1.

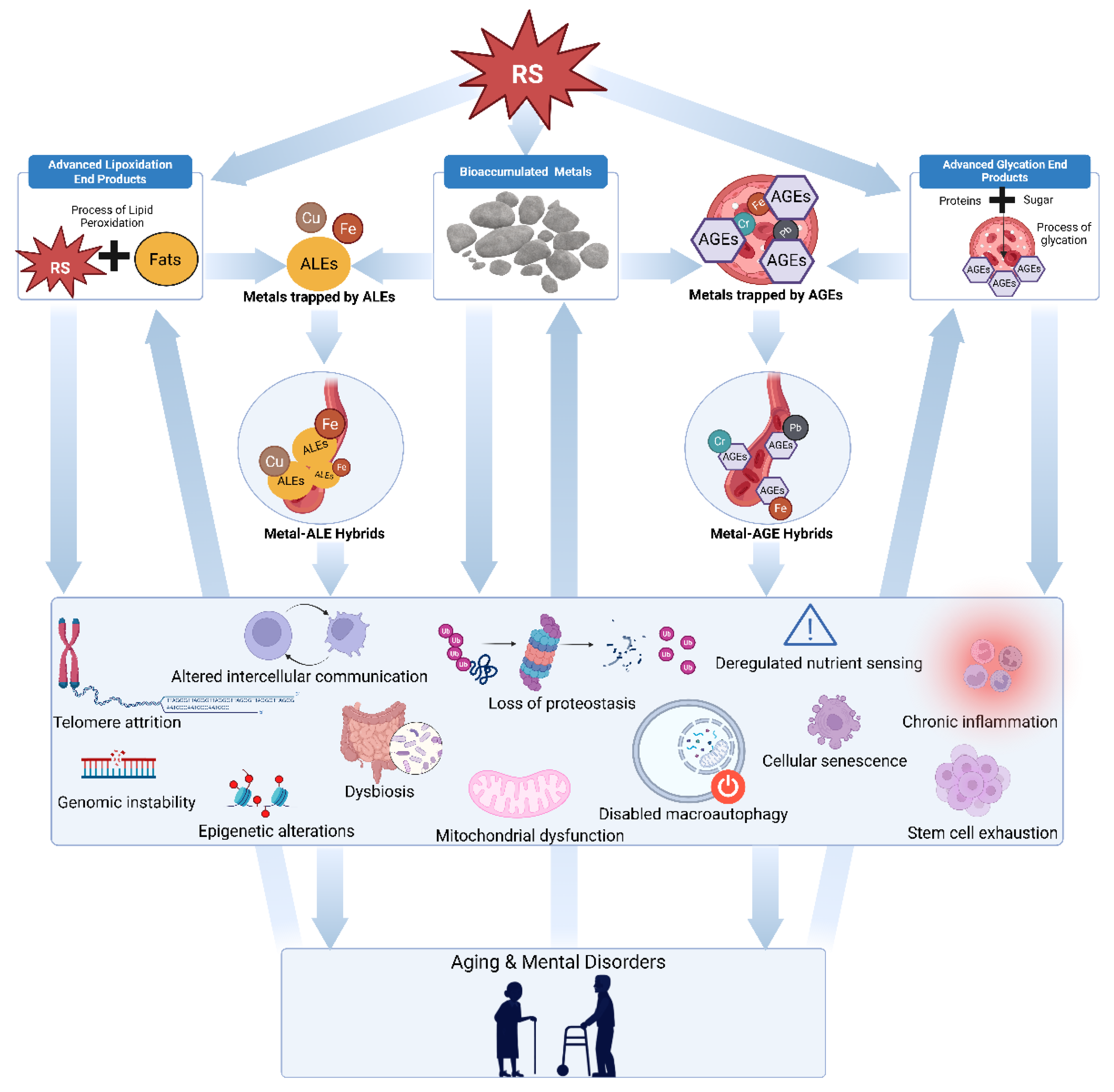

Diagram illustrating the geropsychosis framework. The arrows show proposed causal pathways, starting with damage from multiple types of reactive species which generate advanced glycation end products, accumulated metals, advanced lipoxidation end products, and metal AGE/ALE hybrid compounds. These entities collectively trigger various forms of cellular damage and mental disorders through synergistic and autocatalytic mechanisms.

Figure 1.

Diagram illustrating the geropsychosis framework. The arrows show proposed causal pathways, starting with damage from multiple types of reactive species which generate advanced glycation end products, accumulated metals, advanced lipoxidation end products, and metal AGE/ALE hybrid compounds. These entities collectively trigger various forms of cellular damage and mental disorders through synergistic and autocatalytic mechanisms.

2. Metal Bioaccumulation and Neurotoxicity

Several transition metals, including iron, copper, and zinc, contribute to both aging and psychiatric pathology. Excessive iron catalyzes the formation of highly reactive oxygen species through Fenton reactions, which overwhelm the brain’s antioxidant defenses, damage mitochondrial function, and cause oxidative modifications to proteins, lipids, and DNA (Zhao et al., 2024; Urrutia et al., 2014). These pro-oxidant conditions promote the aggregation of misfolded proteins and compromise energy metabolism (Joppe et al., 2019). Both processes have been linked to neurodegenerative and psychiatric diseases including depression, schizophrenia, and Alzheimer’s disease (Duarte-Silva et al., 2025; Theleritis et al., 2025; Szewczyk, 2013). Importantly, transition metals can interact with pathogenic proteins, as seen when iron and copper accumulate in amyloid plaques or tau tangles, accelerating neuronal injury and cognitive dysfunction (Kim et al., 2018; Zubčić et al., 2020).

In addition to causing oxidative damage, transition metal dysregulation disrupts essential neurotransmitter pathways. Copper and zinc serve as critical cofactors in the synthesis and regulation of neurotransmitters such as dopamine, glutamate, GABA, and serotonin (Joe et al., 2018). Imbalances in copper levels disrupt dopamine and monoamine oxidase metabolism, while zinc modulates synaptic inhibition and excitation (Olivero et al., 2018). These metals also participate in the folding and turnover of neuropeptides and synaptic proteins, which means that their imbalance can impair synaptic plasticity, learning, and memory (Wingo et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2016). The accumulation of transition metals ultimately leads to catastrophic cascades that include oxidative stress, abnormal gene expression, protein aggregation, bioenergetic failure, and neurotransmitter dysfunction (Cristóvão et al., 2016).

Heavy metals such as lead, mercury, cadmium, and aluminum also accumulate in brain tissue over time and promote neurodegeneration through multiple mechanisms including oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and protein aggregation (Bakulsi et al., 2020). The neurotoxic effects of heavy metals are particularly relevant to psychiatric disorders, as these metals preferentially accumulate in brain regions involved in mood regulation and cognitive function (Pamphlett & Bishop, 2023).

Moreover, heavy metals can interfere with neurotransmitter synthesis and signaling by binding to sulfhydryl groups in proteins and enzymes (Cheng et al., 2025). Lead, for example, can substitute for calcium in synaptic transmission, leading to impaired neurotransmitter release and altered synaptic function (Rădulescu & Lundgren, 2019). Mercury can disrupt microtubule function and interfere with axonal transport, leading to neuronal dysfunction and death (Sadiq et al., 2012; De Vos & Hafezparast, 2017).

The relationship between heavy metal exposure and psychiatric disorders is supported by numerous epidemiological studies. Individuals with higher levels of heavy metals in blood or tissues have increased rates of depression, anxiety, and cognitive impairment (Li et al., 2025; Bai et al., 2024; Chen et al., 2024). The effects of heavy metals on psychiatric symptoms may be particularly pronounced in vulnerable populations, including children, older adults, and individuals with genetic susceptibilities to metal toxicity. The blood-brain barrier, which normally protects the brain from toxic substances, may also be compromised in psychiatric disorders, allowing greater metal accumulation in brain tissue (Lv & Luo, 2025; Shalev et al., 2009).

3. Advanced Glycation End Products and Neurodegeneration

Advanced glycation end products (AGEs), formed through the non-enzymatic glycation of proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, represent a critical link between metabolic dysfunction and neurodegeneration in psychiatric disorders. AGEs accumulate with age and are elevated in individuals with psychiatric conditions such as depression and schizophrenia, particularly those with comorbid metabolic disorders (D’Cunha et al., 2022; Miyashita et al., 2021). The formation of AGEs is accelerated by hyperglycemia, oxidative stress, and inflammation, conditions that are commonly present in psychiatric disorders.

The mechanisms by which AGEs contribute to psychiatric pathology involve multiple pathways. AGE-modified proteins resist degradation and form crosslinks that impair cellular function (Gan et al., 2025). The interaction of AGEs with their receptor (RAGE) activates inflammatory cascades and promotes oxidative stress, creating a feed-forward loop that accelerates aging and neurodegeneration (Boccardi et al., 2025; Koerich et al., 2023; Piras et al., 2016). RAGE activation leads to the production of inflammatory cytokines and reactive oxygen species, which can damage neural tissue and promote further AGE formation (Ray et al., 2016; Piras et al., 2016).

In the brain, AGEs accumulate in vulnerable regions and contribute to neuronal dysfunction through several mechanisms. AGE-modified proteins interfere with synaptic function by disrupting protein-protein interactions and altering cellular signaling pathways (Zhang et al., 2014). AGEs can also impair neurotransmitter metabolism by modifying enzymes involved in neurotransmitter synthesis and degradation (Lee & Kim, 2022). The resulting neuronal damage manifests as cognitive dysfunction, mood disturbances, and behavioral abnormalities characteristic of psychiatric disorders (Morozova et al., 2022; Lee & Kim, 2022).

The relationship between AGEs and psychiatric disorders is particularly evident in conditions associated with metabolic dysfunction. Diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and obesity are all associated with increased AGE formation and higher rates of psychiatric disorders (Leutner et al., 2023; Toalson et al., 2004). The metabolic dysfunction associated with many psychiatric medications may also contribute to AGE formation and worsen psychiatric symptoms over time (Meshkat et al., 2025). In fact, many experience a vicious cycle where psychiatric disorders promote metabolic dysfunction, which leads to increased AGE formation and further psychiatric pathology. Specifically, the glyoxalase system, which detoxifies AGE precursors, is impaired in multiple psychiatric disorders and may contribute to AGE accumulation (Toriumi et al., 2022; Yin et al., 2021). Genetic variations in glyoxalase genes may affect psychiatric risk by altering the efficiency of AGE detoxification (Yin et al., 2021).

4. Advanced Lipoxidation End Products and Neuronal Dysfunction

Emerging mechanistic and animal research suggests that advanced lipoxidation end products (ALEs) contribute to cognitive impairment and neurodegeneration. Wang et al. (2024) found that long-term dietary ALE exposure in mice damaged spatial learning and memory, raised oxidative stress levels, and triggered neuroinflammation by disrupting the AMPK/SIRT1 pathway and the gut microbiota-brain axis, effects linked to cognitive disorders including mild cognitive impairment and dementia. Research reviews show that ALEs, along with advanced glycation end products (AGEs), disrupt protein structure and cellular signaling in the central nervous system through mechanisms such as RAGE (receptor for advanced glycation end products) activation, a process implicated in neurodegenerative diseases and psychiatric conditions including schizophrenia and depression (Boccardi et al., 2025). Additionally, higher ALE levels appear in brains with Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, both of which commonly involve neuropsychiatric symptoms like depression, psychosis, and cognitive decline (Moldogazieva et al., 2019).

Lipofuscin, an autofluorescent lipopigment formed through lipid peroxidation and protein oxidation, emerges as a superlative ALE. It accumulates in neurons during aging and shows accelerated accumulation in psychiatric disorders. This “aging pigment” represents a marker of oxidative damage and impaired cellular clearance mechanisms, serving as a visible manifestation of the cellular aging process (Song et al., 2023). The formation of lipofuscin involves the oxidation of lipids and proteins, followed by the formation of cross-linked aggregates that resist degradation (Höhn & Gruhn, 2013). The process is accelerated by oxidative stress, inflammation, and impaired lysosomal function, all of which are present in psychiatric disorders (Moreno-García et al., 2018). The accumulation of lipofuscin impairs cellular function by interfering with lysosomal activity, disrupting cellular trafficking, and promoting further oxidative stress (Ilie et al., 2020). This creates a self-reinforcing cycle where lipofuscin accumulation promotes cellular dysfunction, which in turn leads to further lipofuscin formation (Baldensperger et al., 2024).

In psychiatric disorders, lipofuscin accumulation is associated with neuronal dysfunction and contributes to the progressive decline in cognitive and emotional function observed in these conditions (Moreno-García et al., 2018; Vijayan & Selvaraj, 2025; Simonati & Williams, 2023). Lipofuscin accumulation is particularly pronounced in brain regions that are vulnerable to psychiatric pathology. The hippocampus, a region critical for memory and emotional regulation, shows significant lipofuscin accumulation in individuals with depression and other psychiatric conditions (Alper et al., 2023; Sheline, 2013). Within animal models, the accumulation is most pronounced in specific hippocampal subregions, including CA1 and CA3, which are also the regions most vulnerable to age-related neuronal loss (Ojo et al., 2013). The prefrontal cortex, another region critical for cognitive and emotional function, also shows increased lipofuscin accumulation in psychiatric disorders (Bernstein et al., 2025).

The relationship between lipofuscin accumulation and psychiatric symptoms appears to be particularly relevant in late-life depression and cognitive disorders. Accelerated lipofuscin formation in vulnerable brain regions may contribute to the treatment resistance and progressive nature of these conditions (Moreno-García et al., 2018). The accumulation of lipofuscin may also explain the age-related increase in psychiatric symptoms and the greater vulnerability of older adults to psychiatric disorders (Sulzer et al., 2008).

5. Cellular Senescence and Psychiatric Disorders

All components of the Conglomerate Theory of Aging independently induce cellular senescence, defined as permanent growth cessation accompanied by the secretory phenotype of inflammatory mediators. The senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) includes numerous cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors that promote chronic inflammation and tissue dysfunction (Carocci et al., 2018). This process creates a self-perpetuating cycle where senescent cells accumulate over time, releasing inflammatory mediators that promote further senescence in neighboring cells (Guo et al., 2013).

In late-life depression, elevated SASP index scores are associated with poorer treatment outcomes, with higher senescence burden predicting reduced likelihood of achieving remission with antidepressant therapy (Diniz et al., 2022). The SASP index correlates strongly with cognitive dysfunction and cardiovascular health problems but shows weaker associations with depression severity itself, suggesting that cellular senescence may represent a common pathway linking psychiatric disorders to broader health outcomes. This finding supports the notion that psychiatric disorders may be manifestations of systemic aging processes rather than isolated brain-based pathologies.

The mechanisms underlying senescence in psychiatric disorders involve multiple interconnected pathways. Chronic stress, a key precipitant of psychiatric symptoms, directly induces cellular senescence through persistent activation of stress response systems (Rentscher et al., 2019). Elevated glucocorticoid levels, characteristic of many psychiatric disorders, accelerate telomere shortening and promote senescence in vulnerable cell populations. The resulting accumulation of senescent cells creates a feed-forward loop, as the SASP factors released by senescent cells can induce senescence in neighboring cells and promote systemic inflammation.

The relationship between cellular senescence and psychiatric disorders extends beyond simple correlation to suggest causal mechanisms. Senescent cells accumulate preferentially in brain regions that are most vulnerable to psychiatric pathology, including the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and limbic structures (Sikora et al., 2021). The SASP factors released by these cells can directly impair neuronal function through multiple mechanisms, including disruption of synaptic transmission, impairment of neuroplasticity, and promotion of neuroinflammation. The inflammatory mediators in the SASP, including interleukin-1β, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α, have been consistently associated with psychiatric symptoms across multiple disorders (Sikora et al., 2021).

The role of cellular senescence in psychiatric disorders is particularly evident in the context of stress-induced pathology. Chronic stress exposure leads to the accumulation of senescent cells in stress-sensitive brain regions, creating a persistent inflammatory state that impairs neural function and promotes psychiatric symptoms (Lyons et al., 2025). The senescent cells themselves become sources of ongoing stress signaling, creating a vicious cycle where stress promotes senescence, which in turn promotes further stress responses and cellular dysfunction.

Recent research has identified specific senescence pathways that may be particularly relevant to psychiatric disorders. The p16INK4a-Rb pathway, which mediates cell cycle arrest in response to stress, is upregulated in individuals with depression and correlates with symptom severity (Teyssier et al., 2012). The p53-p21 pathway, which responds to DNA damage and cellular stress, is also activated in psychiatric disorders and may contribute to the cognitive dysfunction commonly observed in these conditions (Abate et al., 2020). These pathways represent potential therapeutic targets for interventions designed to reduce senescence burden and improve psychiatric outcomes.

6. Neuroinflammation and Inflammaging in Psychiatric Disorders

Akin to the induction of sensesence, all components of the Conglomerate Theory of Aging produce systemic inflammation both independently and collectively in a process deemed “inflammaging”. Thus, neuroinflammation, characterized by activation of microglia and astrocytes with subsequent release of proinflammatory mediators, serves as an additional nexus between aging and psychiatric pathology. The aging brain exhibits a shift from homeostatic balance toward a proinflammatory state, with increased numbers of activated microglia, elevated cytokine levels, and decreased anti-inflammatory mediators (Norden & Godbout, 2013). This neuroinflammatory milieu sensitizes the aged brain to produce exaggerated responses to immune stimuli and psychological stressors, creating a state of chronic inflammation that accelerates neural aging and compromises cognitive and emotional function (Sparkman & Johnson, 2008).

The concept of inflammaging, first described in the context of systemic aging, is particularly relevant to psychiatric disorders. Inflammaging refers to the chronic, low-grade inflammatory state that develops with age and contributes to age-related pathology across multiple organ systems. In the brain, inflammaging manifests as persistent microglial activation, elevated cytokine production, and impaired resolution of inflammatory responses. This creates a hostile environment for neural tissue that promotes oxidative damage, protein aggregation, and cellular dysfunction (Dunn et al., 2020; Jurcau et al., 2024).

In psychiatric disorders, chronic neuroinflammation creates a state of inflammaging that accelerates the aging process and compromises neural function. The resulting cytokine dysregulation affects neurotransmitter systems, impairs neuroplasticity, and promotes the accumulation of pathological proteins associated with neurodegeneration (Rhie et al., 2020). The inflammatory state also disrupts the blood-brain barrier, allowing peripheral inflammatory mediators to enter the brain and further exacerbate neuroinflammation. This creates a self-perpetuating cycle where psychiatric symptoms promote neuroinflammation, which in turn accelerates aging and perpetuates mental health problems.

The relationship between neuroinflammation and psychiatric symptoms is bidirectional and self-reinforcing. Psychological stress activates microglia through multiple pathways, including the release of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) and the activation of toll-like receptors (Beurel et al., 2020; Schramm & Waisman 2022). Activated microglia then produce inflammatory cytokines that can directly affect mood and cognition by interfering with neurotransmitter synthesis and signaling (Singhal & Baune, 2017; Afridi & Suk, 2023). The inflammatory state also activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, leading to elevated cortisol levels that further promote inflammation and neural damage (Bertollo et al., 2025).

Recent research has identified specific inflammatory pathways that may serve as therapeutic targets in psychiatric disorders. The NLRP3 inflammasome, activated by various aging-related stimuli, promotes the release of interleukin-1β and interleukin-18, cytokines that are consistently elevated in depression and other psychiatric conditions (Kouba et al., 2022). The inflammasome serves as a sensor of cellular stress and damage, becoming increasingly active with age and contributing to the chronic inflammatory state associated with aging (Lee & Lee, 2025). Targeting inflammasome activation or downstream inflammatory cascades may provide novel therapeutic approaches for treating psychiatric disorders by addressing the underlying inflammatory aging processes.

The role of astrocytes in neuroinflammation and psychiatric disorders has gained increasing attention. Astrocytes, the most abundant glial cells in the brain, play critical roles in maintaining neural homeostasis and supporting synaptic function. In psychiatric disorders, astrocytes become reactive and release inflammatory mediators that contribute to neuroinflammation and neural dysfunction (Puentes-Orozco, 2024; Novakovic et al., 2023). Reactive astrocytes also lose their ability to provide metabolic support to neurons and to maintain the blood-brain barrier, further contributing to neural pathology (Takata et al., 2021; Manu et al., 2023).

The complement system, part of the innate immune response, also plays a significant role in neuroinflammation and psychiatric disorders. Complement activation leads to the formation of membrane attack complexes that can damage neural tissue and promote further inflammation (Orsini et al., 2014). In psychiatric disorders, complement activation is increased and correlates with symptom severity and cognitive dysfunction (Sierra et al., 2022; Hogenaar & van Bokhoven, 2021). The complement system also plays a role in synaptic pruning, and dysregulated complement activity may contribute to the synaptic pathology observed in psychiatric disorders (Katsuri, 2025).

Peripheral inflammation also contributes to neuroinflammation in psychiatric disorders through multiple mechanisms. Inflammatory cytokines produced in peripheral tissues can cross the blood-brain barrier and activate microglia (Sun et al., 2022). Immune cells from the periphery can also infiltrate the brain through disrupted blood-brain barrier and contribute to neuroinflammation (Millett et al., 2022). The gut-brain axis represents another important pathway by which peripheral inflammation can affect brain function and contribute to psychiatric symptoms (Evrensel et al., 2020).

Anti-inflammatory interventions, including both pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches, show promise in treating psychiatric symptoms. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, although not specifically developed for psychiatric disorders, have shown modest benefits in some studies (Du et al., 2024). More targeted anti-inflammatory approaches, including cytokine inhibitors and microglial modulators, are being investigated for their potential therapeutic effects in psychiatric disorders (Rahimian et al., 2022; Frick et al., 2013).

7. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Bioenergetic Decline

Mitochondrial dysfunction represents a central mechanism linking psychiatric disorders to accelerated aging, as all components of the Conglomerate Theory of Aging both independently and collectively contribute to their systemic decline. Mitochondria are essential for energy production, calcium homeostasis, and regulation of cellular death pathways. In psychiatric disorders, mitochondrial abnormalities manifest as impaired oxidative phosphorylation, increased reactive oxygen species production, and dysregulated calcium handling. The brain’s high energy demands make it particularly vulnerable to mitochondrial dysfunction, with even subtle impairments in mitochondrial function potentially leading to significant neuronal dysfunction and psychiatric symptoms.

The relationship between mitochondrial dysfunction and psychiatric pathology is particularly evident in depression and bipolar disorder. Patients with these conditions show decreased mitochondrial DNA copy number, altered expression of mitochondrial genes, and reduced activity of respiratory chain complexes (Shao et al., 2008). These changes compromise the bioenergetic capacity of neurons, leading to impaired synaptic function and altered neurotransmitter metabolism. The energy deficits associated with mitochondrial dysfunction may manifest as the fatigue, cognitive impairment, and motivational deficits commonly observed in psychiatric disorders.

Mitochondrial dysfunction in psychiatric disorders appears to be both a cause and consequence of aging processes. Chronic stress and inflammatory mediators directly impair mitochondrial function through multiple mechanisms, including disruption of the electron transport chain, alteration of mitochondrial membrane composition, and impairment of mitochondrial biogenesis (Daniels et al., 2020). The resulting bioenergetic crisis compromises the cell’s ability to maintain homeostasis and repair damage, leading to progressive functional decline and accelerated aging (Zhang et al., 2025).

The mechanisms by which mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to psychiatric symptoms are complex and multifaceted. Impaired energy production affects all cellular processes but is particularly detrimental to energy-demanding processes such as neurotransmitter synthesis, synaptic transmission, and neuroplasticity (Clemente-Suárez et al., 2023). Mitochondrial dysfunction also leads to increased production of reactive oxygen species, which can damage cellular components and promote aging-related pathology (Anglin, 2016). The disruption of calcium homeostasis associated with mitochondrial dysfunction can affect synaptic function and contribute to excitotoxicity (Mira & Cerpa, 2021).

Recent research has identified specific mitochondrial pathways that may be particularly relevant to psychiatric disorders. The mitochondrial permeability transition pore, which regulates mitochondrial membrane permeability, is dysregulated in psychiatric disorders and may contribute to cell death and dysfunction (Kalani et al., 2018). Mitochondrial dynamics, including fusion and fission processes, are also altered in psychiatric disorders and may affect mitochondrial function and distribution within neurons (Su et al., 2010). The mitochondrial unfolded protein response, which helps maintain mitochondrial protein homeostasis, is impaired in psychiatric disorders and may contribute to the accumulation of damaged mitochondrial proteins (Olivero et al., 2018).

The role of mitochondrial genetics in psychiatric disorders is also becoming increasingly recognized. Mitochondrial DNA mutations, which accumulate with age, may contribute to psychiatric vulnerability (Sequeira et al., 2012). Variations in nuclear genes that encode mitochondrial proteins may also affect psychiatric risk (Schulmann et al., 2019). The maternal inheritance of mitochondrial DNA may explain some aspects of psychiatric heritability that are not accounted for by nuclear genetics alone (Verge et al., 2011; Boles et al., 2005).

The therapeutic implications of mitochondrial dysfunction in psychiatric disorders are significant. Interventions targeting mitochondrial function, including coenzyme Q10 supplementation, mitochondrial antioxidants, and metabolic modulators, show promise in treating psychiatric symptoms. Coenzyme Q10, a critical component of the electron transport chain, has shown benefits in multiple psychiatric conditions, including depression and bipolar disorder (Forester et al., 2015; Maguire et al., 2020). The effects appear to be most pronounced in individuals with evidence of mitochondrial dysfunction, suggesting that biomarkers of mitochondrial function may help identify patients who would benefit from mitochondrial-targeted therapies.

Metabolic interventions that support mitochondrial function may also be beneficial in psychiatric disorders. Ketogenic diets, which provide alternative fuel sources for the brain, have shown promise in treating bipolar disorder and may work by improving mitochondrial function (Needham et al., 2023). Exercise, which promotes mitochondrial biogenesis and function, has established benefits in psychiatric disorders and may work partly through its effects on mitochondrial health (Sun et al., 2022).

8. DNA Damage and Genomic Instability

DNA damage accumulation represents an additional Conglomerate induced mechanism of aging that shows striking parallels with psychiatric pathology. Individuals with psychiatric disorders exhibit significantly elevated levels of oxidative DNA damage, including increased 8-oxo-dG levels in serum and brain tissue (Jorgensen et al., 2022). This genomic instability compromises cellular function and promotes the aging process through multiple mechanisms, including impaired gene expression, cellular senescence, and programmed cell death.

The sources of DNA damage in psychiatric disorders are multifaceted and include oxidative stress, inflammatory mediators, and glucocorticoid-induced genomic instability. Chronic elevation of stress hormones, characteristic of many psychiatric conditions, directly promotes DNA damage through increased reactive oxygen species production and impaired DNA repair mechanisms (Jenkins et al., 2014). The inflammatory state associated with psychiatric disorders also contributes to DNA damage through the production of reactive nitrogen species and the activation of enzymes that can damage DNA (Czarny et al., 2018).

The relationship between DNA damage and psychiatric symptoms appears to be bidirectional and self-reinforcing. While psychiatric disorders promote DNA damage through stress-induced oxidative stress and inflammation, genomic instability itself may contribute to psychiatric symptoms by impairing neuronal function and promoting neurodegeneration. DNA damage can disrupt gene expression, leading to altered protein synthesis and cellular dysfunction. The accumulation of DNA damage may also trigger cellular senescence or apoptosis, contributing to the neural pathology observed in psychiatric disorders (Raza et al., 2016).

Telomere attrition, a specific form of DNA damage, is consistently observed in psychiatric disorders and correlates with symptom severity and treatment resistance (Muneer & Minhas, 2019)). Shortened telomeres in individuals with depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia equivalent to 10-15 years of accelerated aging, suggesting that psychiatric disorders fundamentally disrupt the cellular aging process (Pousa et al., 2021; Squassina et al., 2020). The mechanisms underlying telomere attrition in psychiatric disorders include chronic stress exposure, inflammation, and oxidative stress, all of which can accelerate telomere shortening.

The role of DNA repair mechanisms in psychiatric disorders is also important to consider. DNA repair systems, which normally protect against genomic instability, may be impaired in psychiatric disorders. Chronic stress and inflammation can interfere with DNA repair processes, leading to the accumulation of unrepaired DNA damage. Genetic variations in DNA repair genes may also contribute to psychiatric vulnerability by affecting the efficiency of DNA repair processes.

Recent research has identified specific DNA damage pathways that may be particularly relevant to psychiatric disorders. The ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) pathway, which responds to DNA double-strand breaks, is activated in psychiatric disorders and may contribute to cellular senescence and neurodegeneration (Focchi et al., 2022; Pizzamiglio et al., 2021). The poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) pathway, which is involved in DNA repair, is also dysregulated in psychiatric disorders and may contribute to cellular dysfunction (Arat Çelik et al., 2024).

The therapeutic implications of DNA damage in psychiatric disorders include the development of interventions that can reduce DNA damage or enhance DNA repair. Antioxidant therapies, which can reduce oxidative stress and prevent DNA damage, show promise in treating psychiatric symptoms (Liu et al., 2024). Compounds that can enhance DNA repair, such as NAD+ precursors, may also have therapeutic potential. The identification of DNA damage biomarkers in psychiatric disorders may enable more precise diagnosis and treatment monitoring.

9. MicroRNA Dysregulation

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) represent a class of regulatory molecules that control gene expression and play critical roles in aging and psychiatric disorders. Age-related changes in miRNA expression, termed “senomiRs,” contribute to cellular senescence and age-related pathology, with evidence of impact for bioaccumulated metals, AGEs, and ALEs (Turko et al., 2025; Wallace et al., 2020). (Weigl et al., 2024). In psychiatric disorders, dysregulation of specific miRNAs is associated with altered neuroplasticity, impaired stress responses, and accelerated aging (Pal & Mandal, 2025; Adly et al., 2025). The identification of circulating senomiRs provides potential biomarkers for monitoring aging-related changes in psychiatric patients and assessing treatment response (van den Berg, 2020).

The mechanisms by which miRNAs contribute to aging and psychiatric disorders involve the regulation of multiple cellular pathways. miRNAs can regulate the expression of genes involved in cellular senescence, inflammation, mitochondrial function, and DNA repair (Williams et al., 2016). Changes in miRNA expression with age can lead to the dysregulation of these pathways and contribute to cellular dysfunction. In psychiatric disorders, miRNA dysregulation may amplify aging-related pathology and contribute to the accelerated aging observed in these conditions (Tamatta & Singh, 2025). Recent research has identified specific miRNAs that may be particularly relevant to psychiatric disorders and aging. miR-124, which is specifically expressed in neurons and regulates neuronal differentiation, is altered in psychiatric disorders and may contribute to neuronal dysfunction (Chen et al., 2024; Namkung et al., 2023).

The role of miRNAs in neuroplasticity and psychiatric disorders is also important to consider. miRNAs regulate the expression of genes involved in synaptic plasticity, neurogenesis, and neuronal survival (Sun et al., 2015). Changes in miRNA expression in psychiatric disorders may impair these processes and contribute to the cognitive and emotional symptoms observed in these conditions. The dysregulation of miRNAs may also contribute to the impaired response to antidepressant treatment observed in some patients.

10. Integrated Pathophysiological Model of Geropsychosis

The geropsychosis framework proposes that psychiatric disorders arise from the convergent action of multiple aging mechanisms that compromise neural and systemic function. The Conglomerate Theory of Aging provides the underlying theory for this approach by identifying the major biophysical, upstream drivers of consistent tissue damage via long term accumulation. This integrated model explains several key features of psychiatric disorders that are difficult to account for using traditional approaches.

The heterogeneity of psychiatric presentations reflects the differential vulnerability of neural circuits to aging processes. Different brain regions have varying susceptibilities to aging-related damage based on their metabolic demands, connectivity patterns, and cellular composition. The prefrontal cortex, with its high metabolic demands and extensive connectivity, is particularly vulnerable to aging-related pathology and is commonly affected in psychiatric disorders. The hippocampus, with its ongoing neurogenesis and high plasticity, is also vulnerable to aging-related dysfunction and is implicated in mood and cognitive disorders.

The progressive nature of many psychiatric conditions mirrors the cumulative effects of aging-related damage. As aging mechanisms accumulate and interact over time, they create increasingly severe disruptions to neural function. This progression may explain why psychiatric disorders often worsen over time and why early intervention is so important. The self-reinforcing nature of aging mechanisms means that small initial insults can cascade into larger pathological changes over time.

The comorbidity between psychiatric and physical disorders reflects the systemic nature of aging processes that affect multiple organ systems simultaneously. The same aging mechanisms that contribute to psychiatric symptoms also contribute to cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and other age-related conditions. This shared pathophysiology explains why individuals with psychiatric disorders have higher rates of physical health problems and shortened lifespans.

This understanding has profound implications for prevention, treatment, and prognosis in psychiatric disorders. By addressing the root causes of psychiatric pathology, aging-targeted interventions may provide more durable and comprehensive benefits. The model also suggests that combinations of interventions targeting multiple aging mechanisms may be more effective than single-target approaches given the heterogeneity of damage pathways.

11. Accelerated Brain Aging in Psychiatric Disorders

The most compelling evidence for geropsychosis comes from neuroimaging studies demonstrating accelerated brain aging across multiple psychiatric conditions. Brain age prediction models, which estimate biological age based on structural MRI features, consistently show that individuals with psychiatric disorders have brains that appear older than their chronological age.

In major depressive disorder, the brain-predicted age difference (brain-PAD) is significantly elevated, with patients showing an average of 2.78 years of additional brain aging compared to healthy controls (Han et al., 2021). This acceleration is most pronounced in patients with somatic depressive symptoms, suggesting that the physical manifestations of depression may reflect underlying neurobiological aging processes. The relationship between brain aging and depression severity appears to be dose-dependent, with more severe depressive episodes associated with greater degrees of brain aging acceleration. Importantly, antidepressant treatment appears to have a protective effect, reducing brain-PAD by approximately 2.53 years, indicating that therapeutic interventions may slow or reverse aging-related changes (Han et al., 2021).

The relationship between brain aging and psychiatric disorders varies across the lifespan, with particularly striking patterns emerging in geriatric populations. While midlife adults with depression show differences in brain aging compared to controls, older adults with depression exhibit significantly accelerated brain aging (Christman et al., 2020). This age-dependent effect suggests that the cumulative burden of psychiatric pathology may compound over time, creating increasingly severe disruptions to brain structure and function. The phenomenon may reflect the progressive nature of aging-related cellular dysfunction, whereby early subtle changes eventually cascade into more pronounced pathological alterations.

The specificity of brain aging patterns provides further evidence for the geropsychosis framework. In schizophrenia, brain aging acceleration is most pronounced in the frontal cortex and occurs primarily in younger individuals, with the effect diminishing with age (Pei et al., 2025). This pattern suggests that different psychiatric disorders may target specific neural circuits and developmental periods, consistent with the heterogeneous nature of aging processes across different brain regions and cellular populations. The frontal cortex, being particularly vulnerable to aging-related changes due to its high metabolic demands and extensive connectivity, may serve as a sentinel region for detecting early aging-related pathology in psychiatric disorders.

Regional specificity of brain aging in psychiatric disorders extends beyond schizophrenia to include other conditions. In bipolar disorder, accelerated aging appears most pronounced in limbic structures, including the hippocampus and amygdala, regions critical for emotional regulation and memory processing (Maletic and Raison, 2014). Anxiety disorders show preferential aging in the insula and anterior cingulate cortex, areas involved in interoception and emotional processing (Alvarez et al., 2015). These regional patterns suggest that the aging process may selectively target neural circuits that are most relevant to the specific symptom profiles of different psychiatric conditions.

The mechanisms underlying accelerated brain aging in geropsychosis encompass multiple interconnected pathways. Inflammatory processes, driven by activated microglia and peripheral immune activation, create a hostile environment for neural tissue that promotes oxidative damage and protein aggregation (Muzio et al., 2021). Vascular changes, including blood-brain barrier disruption and reduced cerebral blood flow, compromise the delivery of nutrients and oxygen to neural tissue, further accelerating aging processes (Hussain et al., 2021).

12. Therapeutic Implications and Novel Interventions

Emerging geropsychosis interventions fall into several categories, including senolytic agents, mitochondrial therapeutics, anti-inflammatory interventions, and comprehensive nutritional protocols. The development of such therapies for psychiatric disorders represents a paradigm shift from symptom-based treatment to mechanism-based interventions.

Senolytic agents, which selectively eliminate senescent cells, represent one of the most promising approaches to aging-targeted therapy. Dasatinib and quercetin, a senolytic combination that has shown efficacy in animal models of aging, is currently being tested in clinical trials for psychiatric disorders (Schweiger et al., 2025). Preliminary data suggest that senolytic therapy may improve cognitive function in older adults with Alzheimer’s pathology (Millar et al., 205). The mechanism of action involves the elimination of senescent cells and the reduction of inflammatory mediators that contribute to neurodegeneration (Lee et al., 2021).

Mitochondrial therapeutics, which target mitochondrial dysfunction, represent another promising approach. Coenzyme Q10, a critical component of the electron transport chain, has shown benefits in multiple psychiatric conditions (Shinkai et al., 2000; Maguire et al., 2020). NAD+ precursors, which support mitochondrial function and DNA repair, are also being investigated for their therapeutic potential with regard to mitochondrial biogenesis (Cambridge University, 2018). Mitochondria-targeted antioxidants, which can provide selective protection against mitochondrial oxidative damage, may also have therapeutic benefits.

Anti-inflammatory interventions, which target neuroinflammation and systemic inflammation, show promise in treating psychiatric symptoms. While traditional anti-inflammatory drugs have shown efficacy in psychiatric disorders, more targeted approaches may be more effective (Gong et al., 2025). Inhibitors of specific inflammatory pathways, such as the NLRP3 inflammasome, are being investigated for their therapeutic potential (Kalaga & Ray, 2025).

Comprehensive nutritional protocols, which provide the nutrients necessary for optimal cellular function and aging resistance, may also have therapeutic benefits. These protocols typically include antioxidants, anti-inflammatory compounds, nutrients that support DNA repair and cellular detoxification, and compounds that promote mitochondrial function. The synergistic effects of these nutrients may be greater than their individual effects.

12.1. Nutritional Protocol Based on Conglomerate Theory

A comprehensive nutritional protocol can be designed to target the underlying aging mechanisms contributing to psychiatric disorders. This protocol addresses the four major aging components that undergird the geropsychosis theory: bioaccumulated metals, AGEs, ALEs, and their hybrid complexes. The recommended protocol is divided into core compounds that address fundamental aging mechanisms and adjuvant compounds that provide additional support for specific pathways.

12.2. Core Compounds

Glutathione is often called the “master regulator” because it coordinates the body’s antioxidant defense system and serves as the primary intracellular antioxidant. N-acetylcysteine (NAC) is a precursor to cysteine, the rate-limiting substrate for glutathione production. Research demonstrates that NAC supplementation can improve glutathione levels, reduce oxidative stress, and provide neuroprotective effects in psychiatric disorders (Schmitt et al., 2015; Dean et al., 2011; Bradlow et al., 2022). NAC has shown particular promise in treating depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia by reducing inflammatory cytokines and improving cellular energy metabolism (Dean et al., 2011; Hans et al., 2022).

Glycine is a conditionally essential amino acid involved in neurotransmission and detoxification. It is also a direct precursor for glutathione. Research has shown that glycine supplementation can improve sleep quality, reduce subjective fatigue, and modulate NMDA receptor function, all of which are relevant to psychiatric health (Kawai et al., 2015). It also plays a role in anti-inflammation and cytoprotection by decreasing pro-inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress, thereby offering therapeutic support in disorders associated with accelerated aging and mitochondrial dysfunction (Johnson & Cuelar, 2023; Aguayo-Cerón et al., 2023; Ramos-Jiménez et al., 2024). The combination of glycine and NAC, known as GlyNAC has shown a 24% increase in lifespan in mice, suggesting a synergistic effect via glutathione production that may also provide outsized mental health dividends.

Alpha-lipoic acid is a potent, naturally occurring antioxidant and metal chelator uniquely capable of crossing the blood-brain barrier, making it effective in protecting neural tissue from both water-soluble and fat-soluble toxicants. It not only neutralizes free radicals directly but also plays a role in regenerating other antioxidants such as vitamins C and E, thereby enhancing the body’s overall antioxidant defenses. Research indicates that alpha-lipoic acid mitigates oxidative stress, improves mitochondrial function, and reduces inflammation, with preliminary animal models demonstrating its neuroprotective effects in both neurodegenerative conditions and psychiatric disorders (Gomes et al., 2025; Fahmy et al., 2024).

Benfotiamine is a lipid-soluble form of vitamin B1 (thiamine) with superior cellular bioavailability, enabling it to cross biological membranes efficiently. By inhibiting the formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs), benfotiamine prevents glycation-induced damage, which is especially beneficial in conditions associated with elevated blood sugar or metabolic dysfunction. Clinical studies have demonstrated that benfotiamine can improve nerve conduction and reduce neuropathic symptoms in diabetic patients, highlighting its value for individuals at risk of metabolic and neurodegenerative complications (Bozic & Lavrnja, 2023; Haupt et al., 2005).

Carnosine, a dipeptide composed of beta-alanine and histidine, exerts dual action as an antiglycation and antioxidant agent. It inhibits the formation of AGEs and is capable of breaking existing protein cross-links, thus helping to maintain protein function in aging tissues. Carnosine also scavenges reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reduces oxidative damage while demonstrating neuroprotective effects in animal models of neurodegeneration and cognitive impairment (O’Toole et al., 2025; Shen et al., 2024; Peng et al., 2022). These properties make carnosine a promising supplement for protecting against both metabolic and neuropsychiatric sequelae of accelerated aging.

Gamma-tocopherol, a form of vitamin E, is a fat-soluble antioxidant that offers superior protection against lipid peroxidation compared to the more common alpha-tocopherol. It is particularly effective in quenching reactive nitrogen species such as peroxynitrite, playing a unique role in the detoxification of advanced lipid peroxidation end products (ALEs). Studies suggest that gamma-tocopherol reduces inflammation and oxidative stress more efficiently than alpha-tocopherol alone, and its presence in the diet or as a supplement may help counteract neurodegenerative and psychiatric processes linked to oxidative lipid damage (Jiang et al., 2022; Pahrudin Arrozi et al., 2020).

Lycopene is a lipid-soluble carotenoid with potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, particularly effective in neutralizing singlet oxygen and reducing lipid peroxidation, preventing ALE formation. Studies have found that higher lycopene levels are associated with lower rates of cognitive decline, improved mitochondrial function, and reduced oxidative stress in neurodegenerative and psychiatric conditions (Xu et al., 2025; Crowe-White et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2024). Lycopene also supports vascular health and may help protect against blood-brain barrier disruption, making it valuable in addressing neurovascular components of psychiatric aging (Adelakun et al., 2025).

Magnesium is involved in more than 300 enzymatic reactions and is essential for proper nervous system function. Its role as a cofactor for enzymes like superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase also makes it an essential defender against cellular aging, directly inhibiting the lipid peroxidation that forms ALEs and indirectly reducing the AGEs that contribute to tissue damage (Vural et al., 2010; de Oliveira et al., 2024; Brahma et al., 2025). Magnesium deficiency is common in psychiatric disorders, including depression and anxiety, and supplementation has been shown to improve mood, reduce anxiety, and enhance stress resilience (Botturi et al., 2020; Noah et al., 2021; Moabedi et al., 2023).

Zinc is essential for immune regulation and neurotransmitter synthesis. It plays a direct role in mitigating cellular aging by serving as a cofactor for the antioxidant enzyme superoxide dismutase (SOD1), directly scavenging AGE precursors like methylglyoxal, and competing with pro-oxidant metals to inhibit the formation of AGEs and ALEs (Zago & Oteiza, 2001; Kheirouri et al., 2018; McCarty et al., 2022; Anandan et al., 2019;. Zinc deficiency has been associated with higher rates of depression and anxiety, and supplementation can improve mood and cognitive performance in both clinical and subclinical populations (Grønli et al., 2013, Yosaee et al., 2022).

12.3. Adjuvant Compounds

Vitamin D deficiency is highly prevalent in individuals with psychiatric disorders (McCue et al., 2012; Cuomo et al., 2019). Clinical studies and meta-analyses indicate that vitamin D supplementation can reduce depressive symptoms and lower inflammation (Musazadeh et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2024). Monitoring blood levels to maintain concentrations above 40–50 ng/mL is recommended for optimal mental health outcomes (Cuomo et al., 2017).

A B-complex formula provides therapeutic doses of all B vitamins, which are crucial for energy metabolism and the synthesis of neurotransmitters. Deficiencies in B vitamins are common in psychiatric populations and have been shown to contribute to fatigue, mood disturbances, and cognitive impairment (Firth et al., 2018; Young et al., 2019). Supplementation can improve psychiatric symptoms and overall well-being (Mahdavifar et al., 2021; Firth et al., 2017; Fatima et al., 2024).

13. Future Directions and Clinical Implementation

The geropsychosis framework presents significant opportunities for advancing psychiatric research and clinical practice. Critical priorities include developing and validating aging-related biomarkers for psychiatric disorders, conducting rigorous clinical trials of aging-targeted interventions, and integrating these assessments into standard psychiatric evaluation protocols. Biomarkers of bioaccumulated metals, AGEs, and ALEs offer potential for objective measurement of psychiatric pathology. These biological indicators could complement traditional symptom-based assessments and inform personalized health approaches by predicting treatment response and guiding individualized intervention strategies.

Large-scale, well-controlled clinical trials are paramount to establishing the therapeutic efficacy of aging-targeted interventions. Such studies should employ diverse patient populations, validated outcome measures, and assess both clinical symptoms and aging-related biomarkers. Multi-target combination therapies addressing multiple aging mechanisms may demonstrate superior efficacy compared to single-target approaches. With empirical support, integration of aging-focused assessments into routine psychiatric care has potential to enhance treatment outcomes and prevention strategies.

Additionally, early intervention targeting aging mechanisms represents a promising avenue for primary prevention of psychiatric disorders. Addressing these processes before full disorder manifestation could substantially reduce the public health burden of mental illness. Moreover, the geropsychosis framework provides insight into treatment-resistant psychiatric conditions. Patients with elevated aging-related pathology may exhibit diminished response to conventional treatments, potentially requiring aging-targeted interventions for optimal outcomes.

14. Conclusion

Geropsychosis reframes psychiatric disorders as manifestations of accelerated aging for post-pubescent individuals. By integrating the Conglomerate Theory of Aging with psychiatric pathology, this framework explains how bioaccumulated metals, AGEs, ALEs, and their hybrid complexes create the self-reinforcing pathological cycles seen in mental illness.

The evidence supporting this model comes from several sources. Neuroimaging studies show accelerated brain aging in psychiatric patients. Cellular research demonstrates aging-related pathology at the molecular level. Longitudinal studies reveal that psychiatric symptoms predict biological aging. Together, these observations have important therapeutic implications. With specific systemic damage routes identified, we can target aging mechanisms to address root causes of mental disorders. The nutritional protocol based on the Conglomerate Theory offers a practical clinical framework for such interventions. Combined with conventional psychiatric care, this approach may produce stronger outcomes than either strategy in isolation. Viewing psychiatric disorders as accelerated aging also shapes prevention efforts. Thus, the geropsychosis framework points toward the reduction of mental illness burden at a population level if mechanistically validated and integrated into best practices. By exploring the nexus of these fundamental biological processes, we can achieve more durable well-being for all current patients while preventing the advent of future suffering.

Author Contributions

The author is solely responsible for all aspects of this work, including theory development, manuscript preparation, and analysis.

Funding

No funding was received to support this work.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Dr. Chidi Nwekwo, Near East University, for his expert contributions as a biomedical illustrator in creating the schematic diagram used to demonstrate our theory of aging. Dr. Nwekwo’s skillful visual interpretation of the major concepts presented in this work greatly enhanced the clarity and accessibility of our theoretical framework.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest related to this work.

References

- Abate, G., Frisoni, G. B., Bourdon, J. C., Piccirella, S., Memo, M., & Uberti, D. (2020). The pleiotropic role of p53 in functional/dysfunctional neurons: focus on pathogenesis and diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s research & therapy, 12(1), 160. [CrossRef]

- Adelakun, S. A., Siyanbade, J. A., Peter, A. B., Salami, M. A., Adeyeluwa, B. E., & Kaka, O. Z. (2025). Neurological mechanism of the dietary supplementations of lycopene on chemotherapy-induced cognitive dysfunction/chemobrain and hippocampal toxicity in the rat model. Aspects of Molecular Medicine, 6, Article 100094. [CrossRef]

- Adly, N. M., Khalifa, D., Abdel-Ghany, S., & Sabit, H. (2025). Dysregulation of MiRNAs in schizophrenia in an Egyptian patient population. Scientific reports, 15(1), 16998. [CrossRef]

- Afridi, R., & Suk, K. (2023). Microglial Responses to Stress-Induced Depression: Causes and Consequences. Cells, 12(11), 1521. [CrossRef]

- Aguayo-Cerón, K. A., Sánchez-Muñoz, F., Gutierrez-Rojas, R. A., Acevedo-Villavicencio, L. N., Flores-Zarate, A. V., Huang, F., Giacoman-Martinez, A., Villafaña, S., & Romero-Nava, R. (2023). Glycine: The Smallest Anti-Inflammatory Micronutrient. International journal of molecular sciences, 24(14), 11236. [CrossRef]

- Alper, J., Feng, R., Verma, G., Rutter, S., Huang, K. H., Xie, L., Yushkevich, P., Jacob, Y., Brown, S., Kautz, M., Schneider, M., Lin, H. M., Fleysher, L., Delman, B. N., Hof, P. R., Murrough, J. W., & Balchandani, P. (2023). Stress-related reduction of hippocampal subfield volumes in major depressive disorder: A 7-Tesla study. Frontiers in psychiatry, 14, 1060770. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, R. P., Kirlic, N., Misaki, M., Bodurka, J., Rhudy, J. L., Paulus, M. P., & Drevets, W. C. (2015). Increased anterior insula activity in anxious individuals is linked to diminished perceived control. Translational psychiatry, 5(6), e591. [CrossRef]

- Anandan, S., Mahadevamurthy, M., Ansari, M. A., Alzohairy, M. A., Alomary, M. N., Farha Siraj, S., Halugudde Nagaraja, S., Chikkamadaiah, M., Thimappa Ramachandrappa, L., Naguvanahalli Krishnappa, H. K., Ledesma, A. E., Nagaraj, A. K., & Urooj, A. (2019). Biosynthesized ZnO-NPs from Morus indica Attenuates Methylglyoxal-Induced Protein Glycation and RBC Damage: In-Vitro, In-Vivo and Molecular Docking Study. Biomolecules, 9(12), 882. [CrossRef]

- Anglin R. (2016). Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Psychiatric Illness. Canadian journal of psychiatry. Revue canadienne de psychiatrie, 61(8), 444–445. [CrossRef]

- Arat Çelik, H. E., Yılmaz, S., Akşahin, İ. C., Kök Kendirlioğlu, B., Çörekli, E., Dal Bekar, N. E., Çelik, Ö. F., Yorguner, N., Targıtay Öztürk, B., İşlekel, H., Özerdem, A., Akan, P., Ceylan, D., & Tuna, G. (2024). Oxidatively-induced DNA base damage and base excision repair abnormalities in siblings of individuals with bipolar disorder DNA damage and repair in bipolar disorder. Translational psychiatry, 14(1), 207. [CrossRef]

- Bai, L., Wen, Z., Zhu, Y., Jama, H. A., Sawmadal, J. D., & Chen, J. (2024). Association of blood cadmium, lead, and mercury with anxiety: a cross-sectional study from NHANES 2007-2012. Frontiers in public health, 12, 1402715. [CrossRef]

- Bakulski, K. M., Seo, Y. A., Hickman, R. C., Brandt, D., Vadari, H. S., Hu, H., & Park, S. K. (2020). Heavy Metals Exposure and Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease: JAD, 76(4), 1215–1242. [CrossRef]

- Baldensperger, T., Jung, T., Heinze, T., Schwerdtle, T., Höhn, A., & Grune, T. (2024). The age pigment lipofuscin causes oxidative stress, lysosomal dysfunction, and pyroptotic cell death. Free radical biology & medicine, 225, 871–880. [CrossRef]

- Berk, M., Malhi, G. S., Gray, L. J., & Dean, O. M. (2013). The promise of N-acetylcysteine in neuropsychiatry. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences, 34(3), 167-177. [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, H. G., Nussbaumer, M., Vasilevska, V., Dobrowolny, H., Nickl-Jockschat, T., Guest, P. C., & Steiner, J. (2025). Glial cell deficits are a key feature of schizophrenia: implications for neuronal circuit maintenance and histological differentiation from classical neurodegeneration. Molecular psychiatry, 30(3), 1102–1116. [CrossRef]

- Bertollo, A. G., Santos, C. F., Bagatini, M. D., & Ignácio, Z. M. (2025). Hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal and gut-brain axes in biological interaction pathway of the depression. Frontiers in neuroscience, 19, 1541075. [CrossRef]

- Beurel, E., Toups, M., & Nemeroff, C. B. (2020). The Bidirectional Relationship of Depression and Inflammation: Double Trouble. Neuron, 107(2), 234–256. [CrossRef]

- Boccardi, V., Mancinetti, F., & Mecocci, P. (2025). Oxidative Stress, Advanced Glycation End Products (AGEs), and Neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Metabolic Perspective. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland), 14(9), 1044. [CrossRef]

- Boles, R. G., Burnett, B. B., Gleditsch, K., Wong, S., Guedalia, A., Kaariainen, A., Eloed, J., Stern, A., & Brumm, V. (2005). A high predisposition to depression and anxiety in mothers and other matrilineal relatives of children with presumed maternally inherited mitochondrial disorders. American journal of medical genetics. Part B, Neuropsychiatric genetics: the official publication of the International Society of Psychiatric Genetics, 137B(1), 20–24. [CrossRef]

- Botturi, A., Ciappolino, V., Delvecchio, G., Boscutti, A., Viscardi, B., & Brambilla, P. (2020). The Role and the Effect of Magnesium in Mental Disorders: A Systematic Review. Nutrients, 12(6), 1661. [CrossRef]

- Bozic, I., & Lavrnja, I. (2023). Thiamine and benfotiamine: Focus on their therapeutic potential. Heliyon, 9(11), e21839. [CrossRef]

- Bradlow, R. C. J., Berk, M., Kalivas, P. W., Back, S. E., & Kanaan, R. A. (2022). The Potential of N-Acetyl-L-Cysteine (NAC) in the Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders. CNS drugs, 36(5), 451–482. [CrossRef]

- Brahma, D., Sinha, U., & Gupta, A. N. (2025). Effect of magnesium(II) on the glycation-induced oxidative stress of human serum albumin: a spectroscopic investigation. Physical chemistry chemical physics: PCCP, 27(30), 16077–16089. [CrossRef]

- Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. (2018). Nicotinamide riboside and mitochondrial biogenesis [Clinical trial identifier NCT03432871]. ClinicalTrials.gov. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03432871.

- Carocci, A., Catalano, A., Sinicropi, M. S., & Genchi, G. (2018). Oxidative stress and neurodegeneration: the involvement of iron. Biometals: an international journal on the role of metal ions in biology, biochemistry, and medicine, 31(5), 715–735. [CrossRef]

- Chen, K., Tan, M., Li, Y., Song, S., & Meng, X. (2024). Association of blood metals with anxiety among adults: A nationally representative cross-sectional study. Journal of affective disorders, 351, 948–955. [CrossRef]

- Chen, P., Miah, M. R., & Aschner, M. (2016). Metals and Neurodegeneration. F1000Research, 5, F1000 Faculty Rev-366. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S., Ding, S., Pang, Y., Jin, Y., Sun, P., Li, Y., Cao, M., Wang, Y., Wang, Z., Wang, T., Zou, Y., Zhang, Y., & Xiao, M. (2024). Dysregulated miR-124 mediates impaired social memory behavior caused by paternal early social isolation. Translational psychiatry, 14(1), 392. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y. F., Zhao, Y. J., Chen, C., & Zhang, F. (2025). Heavy Metals Toxicity: Mechanism, Health Effects, and Therapeutic Interventions. MedComm, 6(9), e70241. [CrossRef]

- Christman, S., Bermudez, C., Hao, L., Landman, B. A., Boyd, B., Albert, K., Woodward, N., Shokouhi, S., Vega, J., Andrews, P., & Taylor, W. D. (2020). Accelerated brain aging predicts impaired cognitive performance and greater disability in geriatric but not midlife adult depression. Translational psychiatry, 10(1), 317. [CrossRef]

- Clemente-Suárez, V. J., Redondo-Flórez, L., Beltrán-Velasco, A. I., Ramos-Campo, D. J., Belinchón-deMiguel, P., Martinez-Guardado, I., Dalamitros, A. A., Yáñez-Sepúlveda, R., Martín-Rodríguez, A., & Tornero-Aguilera, J. F. (2023). Mitochondria and Brain Disease: A Comprehensive Review of Pathological Mechanisms and Therapeutic Opportunities. Biomedicines, 11(9), 2488. [CrossRef]

- Cristóvão, J. S., Santos, R., & Gomes, C. M. (2016). Metals and Neuronal Metal Binding Proteins Implicated in Alzheimer’s Disease. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity, 2016, 9812178. [CrossRef]

- Crowe-White, K. M., Phillips, T. A., & Ellis, A. C. (2019). Lycopene and cognitive function. Journal of nutritional science, 8, e20. [CrossRef]

- Cuomo, A., Giordano, N., Goracci, A., & Fagiolini, A. (2017). Depression and vitamin D deficiency: Causality, assessment, and clinical practice implications. Neuropsychiatry, 7(5), 606–614. [CrossRef]

- Cuomo, A., Maina, G., Bolognesi, S., Rosso, G., Beccarini Crescenzi, B., Zanobini, F., Goracci, A., Facchi, E., Favaretto, E., Baldini, I., Santucci, A., & Fagiolini, A. (2019). Prevalence and Correlates of Vitamin D Deficiency in a Sample of 290 Inpatients With Mental Illness. Frontiers in psychiatry, 10, 167. [CrossRef]

- Czarny, P., Wigner, P., Galecki, P., & Sliwinski, T. (2018). The interplay between inflammation, oxidative stress, DNA damage, DNA repair and mitochondrial dysfunction in depression. Progress in neuro-psychopharmacology & biological psychiatry, 80(Pt C), 309–321. [CrossRef]

- Daniels, T. E., Olsen, E. M., & Tyrka, A. R. (2020). Stress and psychiatric disorders: The role of mitochondria. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 16, 165-186. [CrossRef]

- D’Cunha, N. M., Sergi, D., Lane, M. M., Naumovski, N., Gamage, E., Rajendran, A., Kouvari, M., Gauci, S., Dissanayka, T., Marx, W., & Travica, N. (2022). The Effects of Dietary Advanced Glycation End-Products on Neurocognitive and Mental Disorders. Nutrients, 14(12), 2421. [CrossRef]

- Dean, O., Giorlando, F., & Berk, M. (2011). N-acetylcysteine in psychiatry: current therapeutic evidence and potential mechanisms of action. Journal of psychiatry & neuroscience: JPN, 36(2), 78–86. [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, A. R. S., Cruz, K. J. C., Morais, J. B. S., Dos Santos, L. R., de Sousa Melo, S. R., Fontenelle, L. C., Severo, J. S., Beserra, J. B., de Sousa, T. G. V., de Freitas, S. T., de Oliveira, E. H. S., Maia, C. S. C., de Matos Neto, E. M., de Oliveira, F. E., Henriques, G. S., & Marreiro, D. D. N. (2024). Magnesium, selenium and zinc deficiency compromises antioxidant defense in women with obesity. Biometals: an international journal on the role of metal ions in biology, biochemistry, and medicine, 37(6), 1551–1563. [CrossRef]

- De Vos, K. J., & Hafezparast, M. (2017). Neurobiology of axonal transport defects in motor neuron diseases: Opportunities for translational research?. Neurobiology of disease, 105, 283–299. [CrossRef]

- Dilger, R. N., & Johnson, R. W. (2008). Aging, microglial cell priming, and the discordant central inflammatory response to signals from the peripheral immune system. Journal of Leukocyte Biology, 84(4), 932-939. [CrossRef]

- Diniz, B. S., Mulsant, B. H., Reynolds, C. F., 3rd, Blumberger, D. M., Karp, J. F., Butters, M. A., Mendes-Silva, A. P., Vieira, E. L., Tseng, G., & Lenze, E. J. (2022). Association of Molecular Senescence Markers in Late-Life Depression With Clinical Characteristics and Treatment Outcome. JAMA network open, 5(6), e2219678. [CrossRef]

- Du, Y., Dou, Y., Wang, M., Wang, Y., Yan, Y., Fan, H., Fan, N., Yang, X., & Ma, X. (2024). Efficacy and acceptability of anti-inflammatory agents in major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in psychiatry, 15, 1407529. [CrossRef]

- Duarte-Silva, E., Maes, M., & Peixoto, C. A. (2025). Iron metabolism dysfunction in neuropsychiatric disorders: Implications for therapeutic intervention. Behavioural Brain Research, 479, Article 115343. [CrossRef]

- Dunn, G. A., Loftis, J. M., & Sullivan, E. L. (2020). Neuroinflammation in psychiatric disorders: An introductory primer. Pharmacology, biochemistry, and behavior, 196, 172981. [CrossRef]

- Evrensel, A., Ünsalver, B. Ö., & Ceylan, M. E. (2020). Neuroinflammation, Gut-Brain Axis and Depression. Psychiatry investigation, 17(1), 2–8. [CrossRef]

- Fahmy, M. I., Khalaf, S. S., & Elrayess, R. A. (2024). The neuroprotective effects of alpha lipoic acid in rotenone-induced Parkinson’s disease in mice via activating PI3K/AKT pathway and antagonizing related inflammatory cascades. European journal of pharmacology, 980, 176878. [CrossRef]

- Fatima, S., Khalid, A., Ijaz, A., Tauqeer, A., Abid, M., Farooq, A., Ali, S., Rasheed, I., Ahmed, Z., & Rana, R. (2024). Vitamin B complex and its association with anxiety and depression. Journal of Population Therapeutics & Clinical Pharmacology, 31(4), 1339–1351. [CrossRef]

- Firth, J., Stubbs, B., Sarris, J., Rosenbaum, S., Teasdale, S., Berk, M., & Yung, A. R. (2017). The effects of vitamin and mineral supplementation on symptoms of schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 47(9), 1515–1527. [CrossRef]

- Firth, J., Carney, R., Stubbs, B., Teasdale, S. B., Vancampfort, D., Ward, P. B., Berk, M., & Sarris, J. (2018). Nutritional deficiencies and clinical correlates in first-episode psychosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 44(6), 1275–1292. [CrossRef]

- Forester, B. P., Harper, D. G., Georgakas, J., Ravichandran, C., Madurai, N., & Cohen, B. M. (2015). Antidepressant effects of open label treatment with coenzyme Q10 in geriatric bipolar depression. Journal of clinical psychopharmacology, 35(3), 338–340. [CrossRef]

- Focchi, E., Cambria, C., Pizzamiglio, L., Murru, L., Pelucchi, S., D’Andrea, L., Piazza, S., Mattioni, L., Passafaro, M., Marcello, E., Provenzano, G., & Antonucci, F. (2022). ATM rules neurodevelopment and glutamatergic transmission in the hippocampus but not in the cortex. Cell death & disease, 13(7), 616. [CrossRef]

- Frick, L. R., Williams, K., & Pittenger, C. (2013). Microglial dysregulation in psychiatric disease. Clinical & developmental immunology, 2013, 608654. [CrossRef]

- Gan, L., Du, X., Wei, Y., & Hu, Z. (2025). Sources of advanced glycation end products in the human body: A mini review. International Journal of Food Science and Technology, 60(1), Article vvaf119. [CrossRef]

- Gomes, B. A. Q., Santos, S. M. D., Gato, L. D. S., Espíndola, K. M. M., Silva, R. K. M. D., Davis, K., Navegantes-Lima, K. C., Burbano, R. M. R., Romao, P. R. T., Coleman, M. D., & Monteiro, M. C. (2025). Alpha-Lipoic Acid Reduces Neuroinflammation and Oxidative Stress Induced by Dapsone in an Animal Model. Nutrients, 17(5), 791. [CrossRef]

- Gong, H., Su, W. J., Deng, S. L., Luo, J., Du, Z. L., Luo, Y., Lv, K. Y., Zhu, D. M., & Fan, X. T. (2025). Anti-inflammatory interventions for the treatment and prevention of depression among older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Translational psychiatry, 15(1), 114. [CrossRef]

- Grønli, O., Kvamme, J. M., Friborg, O., & Wynn, R. (2013). Zinc deficiency is common in several psychiatric disorders. PloS one, 8(12), e82793. [CrossRef]

- Guo, C., Sun, L., Chen, X., & Zhang, D. (2013). Oxidative stress, mitochondrial damage and neurodegenerative diseases. Neural regeneration research, 8(21), 2003–2014. [CrossRef]

- Han, L. K. M., Schnack, H. G., Brouwer, R. M., Veltman, D. J., van der Wee, N. J. A., van Tol, M. J., Aghajani, M., & Penninx, B. W. J. H. (2021). Contributing factors to advanced brain aging in depression and anxiety disorders. Translational psychiatry, 11(1), 402. [CrossRef]

- Han, L. K. M., Dinga, R., Hahn, T., Ching, C. R. K., Eyler, L. T., Aftanas, L., Aghajani, M., Aleman, A., Baune, B. T., Berger, K., Brak, I., Campanella, S., Couvy-Duchesne, B., Cranston, E. E., Cullen, K., Dannlowski, U., Davey, C., Fisch, L., Frenzel, S., Frodl, T., ... Schmaal, L. (2021). Brain aging in major depressive disorder: Results from the ENIGMA major depressive disorder working group. Molecular Psychiatry, 26(9), 5124-5139. [CrossRef]

- Hans, D., Rengel, A., Hans, J., Bassett, D., & Hood, S. (2022). N-Acetylcysteine as a novel rapidly acting anti-suicidal agent: A pilot naturalistic study in the emergency setting. PloS one, 17(1), e0263149. [CrossRef]

- Haupt, E., Ledermann, H., & Köpcke, W. (2005). Benfotiamine in the treatment of diabetic polyneuropathy--a three-week randomized, controlled pilot study (BEDIP study). International journal of clinical pharmacology and therapeutics, 43(2), 71–77. [CrossRef]

- Hogenaar, J. T. T., & van Bokhoven, H. (2021). Schizophrenia: Complement Cleaning or Killing. Genes, 12(2), 259. [CrossRef]

- Höhn, A., & Grune, T. (2013). Lipofuscin: formation, effects and role of macroautophagy. Redox biology, 1(1), 140–144. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, B., Fang, C., & Chang, J. (2021). Blood-Brain Barrier Breakdown: An Emerging Biomarker of Cognitive Impairment in Normal Aging and Dementia. Frontiers in neuroscience, 15, 688090. [CrossRef]

- Ilie, O. D., Ciobica, A., Riga, S., Dhunna, N., McKenna, J., Mavroudis, I., Doroftei, B., Ciobanu, A. M., & Riga, D. (2020). Mini-Review on Lipofuscin and Aging: Focusing on The Molecular Interface, The Biological Recycling Mechanism, Oxidative Stress, and The Gut-Brain Axis Functionality. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania), 56(11), 626. [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, F. J., Van Houten, B., & Bovbjerg, D. H. (2014). Effects on DNA Damage and/or Repair Processes as Biological Mechanisms Linking Psychological Stress to Cancer Risk. Journal of applied biobehavioral research, 19(1), 3–23. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q., Im, S., Wagner, J. G., Hernandez, M. L., & Peden, D. B. (2022). Gamma-tocopherol, a major form of vitamin E in diets: Insights into antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects, mechanisms, and roles in disease management. Free radical biology & medicine, 178, 347–359. [CrossRef]

- Joe, P., Petrilli, M., Malaspina, D., & Weissman, J. (2018). Zinc in schizophrenia: A meta-analysis. General Hospital Psychiatry, 53, 19–24. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A. A., & Cuellar, T. L. (2023). Glycine and aging: Evidence and mechanisms. Ageing Research Reviews, 87, Article 101922. [CrossRef]

- Joppe, K., Roser, A. E., Maass, F., & Lingor, P. (2019). The Contribution of Iron to Protein Aggregation Disorders in the Central Nervous System. Frontiers in neuroscience, 13, 15. [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, A., Baago, I. B., Rygner, Z., Jorgensen, M. B., Andersen, P. K., Kessing, L. V., & Poulsen, H. E. (2022). Association of Oxidative Stress-Induced Nucleic Acid Damage With Psychiatric Disorders in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA psychiatry, 79(9), 920–931. [CrossRef]

- Jurcau, M. C., Jurcau, A., Cristian, A., Hogea, V. O., Diaconu, R. G., & Nunkoo, V. S. (2024). Inflammaging and Brain Aging. International journal of molecular sciences, 25(19), 10535. [CrossRef]

- Jurk, D., Wang, C., Miwa, S., Maddick, M., Korolchuk, V., Tsolou, A., Gonos, E. S., Thrasivoulou, C., Saffrey, M. J., Cameron, K., & von Zglinicki, T. (2012). Postmitotic neurons develop a p21-dependent senescence-like phenotype driven by a DNA damage response. Aging Cell, 11(6), 996-1004. [CrossRef]

- Jurk, D., Wilson, C., Passos, J. F., Oakley, F., Correia-Melo, C., Greaves, L., Saretzki, G., Fox, C., Lawless, C., Anderson, R., Hewitt, G., Pender, S. L., Fullard, N., Nelson, G., Mann, J., van de Sluis, B., Mann, D. A., & von Zglinicki, T. (2014). Chronic inflammation induces telomere dysfunction and accelerates ageing in mice. Nature Communications, 5, 4172. [CrossRef]

- Kalaga, P., & Ray, S. K. (2025). Mental Health Disorders Due to Gut Microbiome Alteration and NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation After Spinal Cord Injury: Molecular Mechanisms, Promising Treatments, and Aids from Artificial Intelligence. Brain sciences, 15(2), 197. [CrossRef]

- Kalani, K., Yan, S. F., & Yan, S. S. (2018). Mitochondrial permeability transition pore: a potential drug target for neurodegeneration. Drug discovery today, 23(12), 1983–1989. [CrossRef]

- Kasturi, S. (2025). Complement C1q in psychiatric disorder: elucidating correlations to synaptic pathology (T). University of British Columbia. Retrieved from https://open.library.ubc.ca/collections/ubctheses/24/items/1.0448996.

- Kawai, N., Sakai, N., Okuro, M., Karakawa, S., Tsuneyoshi, Y., Kawasaki, N., Takeda, T., Bannai, M., & Nishino, S. (2015). The sleep-promoting and hypothermic effects of glycine are mediated by NMDA receptors in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Neuropsychopharmacology: official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 40(6), 1405–1416. [CrossRef]

- Kheirouri, S., Alizadeh, M., & Maleki, V. (2018). Zinc against advanced glycation end products. Clinical and experimental pharmacology & physiology, 45(6), 491–498. [CrossRef]

- Kim, A. C., Lim, S., & Kim, Y. K. (2018). Metal Ion Effects on Aβ and Tau Aggregation. International journal of molecular sciences, 19(1), 128. [CrossRef]