Submitted:

15 October 2025

Posted:

17 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Objectives and Research Questions

- How does organizational dysfunction affect employees’ fertility outcomes and reproductive health?

- What organizational factors most significantly hinder reproductive health in the workplace?

- What are the economic and productivity costs associated with insufficient support for fertility?

- Which workplace accommodations and policies have been shown to improve fertility-related outcomes?

- How do stigma and organizational culture influence employees’ willingness to disclose or seek support?

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Search Strategy

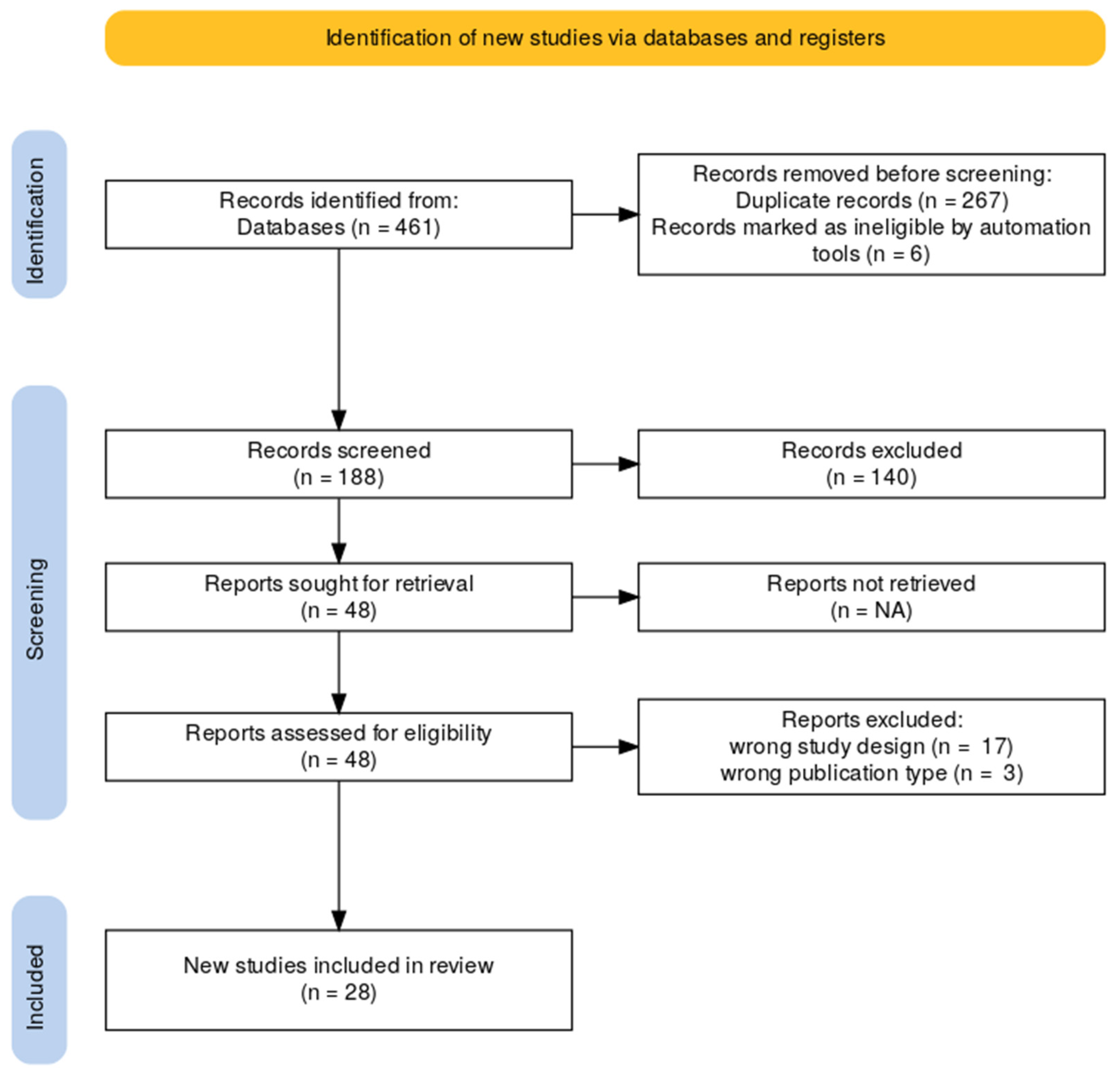

2.4. Study Selection

- Title and Abstract Screening: Two reviewers independently screened all titles and abstracts to determine initial relevance according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria outlined in the PCC framework (see Table 1). Studies that did not meet the basic eligibility requirements were excluded at this stage.

- Full-Text Review: Full texts of potentially eligible studies were retrieved and assessed for inclusion. Discrepancies between reviewers were resolved through discussion.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.2. Synthesis of Research Questions

- Impact of organizational dysfunction on fertility and reproductive health

- Organizational barriers to reproductive well-being

- Economic and productivity consequences of inadequate support

- Effective organizational accommodations and policy interventions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anderson, M., & Goldman, R. H. Occupational Reproductive Hazards for Female Surgeons in the Operating Room. AMA Surgery 2020, 155(3), 243. [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. [CrossRef]

- Armijo, P. R., Flores, L., Huynh, L., Strong, S., Mukkamala, S., & Shillcutt, S. (2021). Fertility and Reproductive Health in Women Physicians. Journal of Women’s Health, 30(12), 1713–1719. [CrossRef]

- Babanov, S. A., Strizhakov, L. A., Agarkova, I. A., Tezikov, Y. V., & Lipatov, I. S. (2019). Workplace factors and reproductive health: Causation and occupational risks assessment. Gynecology, 21(4), 33–43. [CrossRef]

- Baranski, B. (1993). Effects of the workplace on fertility and related reproductive outcome s. Environmental Health Perspectives, 101(suppl 2), 81–90. [CrossRef]

- Barzilai-Pesach, V., Sheiner, E. K., Sheiner, E., Potashnik, G., & Shoham-Vardi, I. (2006). The Effect of Women???s Occupational Psychologic Stress on Outcome of Fertility Treatments. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 48(1), 56–62. [CrossRef]

- Billingsley, S., & Ferrarini, T. (2014). Family Policy and Fertility Intentions in 21 European Countries. Journal of Marriage and Family, 76(2), 428–445. [CrossRef]

- Bisanti, L., Olsen, J., Basso, O., Thonneau, P., & Karmaus, W. (1996). Shift work and subfecundity: A European multicenter study. European St udy Group on Infertility and Subfecundity. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine.

- Boivin, J., & Schmidt, L. (2005). Infertility-related stress in men and women predicts treatment outcome 1 year later. Fertility and Sterility, 83(6), 1745–1752. [CrossRef]

- BOUWMANS, C. A. M., LINTSEN, B. A. M. E., AL, M., VERHAAK, C. M., EIJKEMANS, R. J. C., HABBEMA, J. D. F., BRAAT, D. D. M., & HAKKAART-VAN ROIJEN, L. (2008). Absence from work and emotional stress in women undergoing IVF or ICSI: An analysis of IVF-related absence from work in women and the contri bution of general and emotional factors. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 87(11), 1169–1175. [CrossRef]

- Brugiavini, A., Pasini, G., & Trevisan, E. (2013). The direct impact of maternity benefits on leave taking: Evidence from complete fertility histories. Advances in Life Course Research, 18(1), 46–67. [CrossRef]

- Budig, M. J., Misra, J., & Boeckmann, I. (2012). The Motherhood Penalty in Cross-National Perspective: The Importance o f Work-Family Policies and Cultural Attitudes. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society, 19(2), 163–193. [CrossRef]

- Caetano, G., Bozinovic, I., Dupont, C., Léger, D., Lévy, R., & Sermondade, N. (2021). Impact of sleep on female and male reproductive functions: A systemati c review. Fertility and Sterility, 115(3), 715–731. [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Angeles, M., Atkinson, R. B., Easter, S. R., Gosain, A., Hu, Y.-Y., Cooper, Z., Kim, E. S., Fromson, J. A., & Rangel, E. L. (2022). Postpartum Depression in Surgeons and Workplace Support for Obstetric and Neonatal Complication: Results of a National Study of US Surgeons. Journal of the American College of Surgeons, 234(6), 1051–1061. [CrossRef]

- Castles, F. G. (2003). The World Turned Upside Down: Below Replacement Fertility, Changing Preferences and Family-Friendly Public Policy in 21 OECD Countries. Journal of European Social Policy, 13(3), 209–227. [CrossRef]

- Cech, E. A., & O’Connor, L. T. (2017). ‘Like second-hand smoke’: The toxic effect of workplace flexibility bi as for workers’ health. Community, Work & Family, 20(5), 543–572. [CrossRef]

- Cervi, L., & Knights, D. (2022). Organizing male infertility: Masculinities and fertility treatment. Gender, Work & Organization, 29(4), 1113–1131. [CrossRef]

- Chau, Y. M., West, S., & Mapedzahama, V. (2013). Night Work and the Reproductive Health of Women: An Integrated Literature Review. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 59(2), 113–126. [CrossRef]

- Choi, S., Yellow Horse, A. J., & Yang, T.-C. (2018). Family policies and working women’s fertility intentions in South Kore a. Asian Population Studies, 14(3), 251–270. [CrossRef]

- Cox, S., Cox, T., & Pryce, J. (2000). Work-related reproductive health: A review. Work & Stress, 14(2), 171–180. [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira Trigo, B. R., De Oliveira Trigo, A., Folgado, J., & Lucas, C. (2023). P-576 The perspective of patients and company leaders regarding fertil ity support in the workplace in Portugal. Human Reproduction, 38(Supplement_1). [CrossRef]

- Dehkordi, S. M., Khoshakhlagh, A. H., Yazdanirad, S., Mohammadian-Hafshejani, A., & Rajabi-vardanjani, H. (2025). The effect of job stress on fertility, its intention, and infertility treatment among the workers: A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 25(1). [CrossRef]

- Dyer, S., & Patel, M. (2012). The economic impact of infertility on women in developing countries - a systematic review. Facts, views & vision in ObGyn.

- Fernandez, R., Marino, J., Varcoe, T., Davis, S., Moran, L., Rumbold, A., Brown, H., Whitrow, M., Davies, M., & Moore, V. (2016). Fixed or Rotating Night Shift Work Undertaken by Women: Implications for Fertility and Miscarriage. Seminars in Reproductive Medicine, 34(02), 074–082. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Pineda, M., Black, E. R., & Swift, A. (2025). Secondary Qualitative Analysis of the Effect of Work-Related Stress on Women Who Experienced Miscarriage During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing. [CrossRef]

- Figa-Talamanca, I. (2006). Occupational risk factors and reproductive health of women. Occupational Medicine, 56(8), 521–531. [CrossRef]

- Gamble, K. L., Resuehr, D., & Johnson, C. H. (2013). Shift Work and Circadian Dysregulation of Reproduction. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 4. [CrossRef]

- GIACOLA, G. P. (1992). Reproductive Hazards in the Workplace. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey, 47(10), 679–687. [CrossRef]

- Gifford, B., & Zong, Y. (2017). On-the-Job Productivity Losses Among Employees With Health Problems. Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine, 59(9), 885–893. [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, S. L., Dimoff, J. K., Brady, J. M., Macleod, R., & McPhee, T. (2023). Pregnancy loss: A qualitative exploration of an experience stigmatized in the workplace. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 142, 103848. [CrossRef]

- GLASS, J., & FUJIMOTO, T. (1995). Employer Characteristics and the Provision of Family Responsive Polici es. Work and Occupations, 22(4), 380–411. [CrossRef]

- Goel, L. (2025). Understanding the Impact of Stress on Infertility: Biological Links an d Treatment Strategies. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, 15(1), 207–214. [CrossRef]

- Gold, E. B., & Tomich, E. (1994). Occupational hazards to fertility and pregnancy outcome. Occupational Medicine.

- Győrffy, Z., Dweik, D., & Girasek, E. (2014). Reproductive health and burn-out among female physicians: Nationwide, representative study from Hungary. BMC Women’s Health, 14(1). [CrossRef]

- Hauser, R., Skakkebaek, N. E., Hass, U., Toppari, J., Juul, A., Andersson, A. M., Kortenkamp, A., Heindel, J. J., & Trasande, L. (2015). Male Reproductive Disorders, Diseases, and Costs of Exposure to Endocr ine-Disrupting Chemicals in the European Union. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 100(4), 1267–1277. [CrossRef]

- Henrich, N., Brinson, A., Karwa, S., & Jahnke, H. R. (2025). Use of a digital health benefit to maintain employees’ productivity wh ile trying to conceive. Social Science & Medicine, 382, 118329. [CrossRef]

- Herweck, A. M., Delawalla, M. LM., Reed, C., Carson, T. L., Ahuja, A., Chey, P., McNamara, M., Gupta, K., Bosch, A., Hipp, H. S., & Kawwass, J. F. (2025). Enhancing reproductive access: The influence of expanded employer fertility benefits at a single academic center from 2017 to 2021. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. [CrossRef]

- Hideg, I., Krstic, A., Trau, R. N. C., & Zarina, T. (2018). The unintended consequences of maternity leaves: How agency interventi ons mitigate the negative effects of longer legislated maternity leave s. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(10), 1155–1164. [CrossRef]

- Higgins, C., Duxbury, L., & Julien, M. (2014). The relationship between work arrangements and work-family conflict. WORK: A Journal of Prevention, Assessment & Rehabilitation, 48(1), 69–81. [CrossRef]

- Hvala, T., & Hammarberg, K. (2025). The impact of reproductive health needs on women’s employment: A qualitative insight into managing endometriosis and work. BMC Women’s Health, 25(1). [CrossRef]

- Isaacs, J. C. (2008). Infertility coverage is good business. Fertility and Sterility, 89(5), 1049–1052. [CrossRef]

- Izadi, N., Aminian, O., Ghafourian, K., Aghdaee, A., & Samadanian, S. (2024). Reproductive outcomes among female health care workers. BMC Women’s Health, 24(1). [CrossRef]

- Joseph, D., & Whirledge, S. (2017). Stress and the HPA Axis: Balancing Homeostasis and Fertility. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 18(10), 2224. [CrossRef]

- Jou, J., Kozhimannil, K. B., Blewett, L. A., McGovern, P. M., & Abraham, J. M. (2016). Workplace Accommodations for Pregnant Employees. Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine, 58(6), 561–566. [CrossRef]

- Joyce, K., Pabayo, R., Critchley, J. A., & Bambra, C. (2010). Flexible working conditions and their effects on employee health and w ellbeing. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. [CrossRef]

- Kim, E. J., & Parish, S. L. (2020). Family-supportive workplace policies and benefits and fertility intent ions in South Korea. Community, Work & Family, 25(4), 464–491. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S. (2004). Occupational Exposure Associated with Reproductive Dysfunction. Journal of Occupational Health, 46(1), 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1). [CrossRef]

- Lwin, T. M., Castillo-Angeles, M., Cunningham, C. E., Atkinson, R. B., Kim, E., Easter, S. R., Gosain, A., Hu, Y.-Y., & Rangel, E. L. (2024). The Impact of Low Workplace Support During Pregnancy on Surgeon Distress and Career Dissatisfaction. Annals of Surgery. [CrossRef]

- Lyubykh, Z., Turner, N., Weinhardt, J. M., Davis, J., & Dumaisnil, A. (2025). Facilitating Mental Health Disclosure and Better Work Outcomes: The Ro le of Organizational Support for Disclosing Mental Health Concerns. Human Resource Management. [CrossRef]

- Maeda, E., Hiraike, O., Sugimori, H., Kinoshita, A., Hirao, M., Nomura, K., & Osuga, Y. (2022). Working conditions contribute to fertility-related quality of life: A cross-sectional study in Japan. Reproductive BioMedicine Online, 45(6), 1285–1295. [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, M. M. (2010). Shift Work, Jet Lag, and Female Reproduction. International Journal of Endocrinology, 2010, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, A., Vekved, M., & Tough, S. (2011). P1-242 Impact of work place policies and educational attainment on women’s childbearing decisions in Canada. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 65(Suppl 1), A133–A133. [CrossRef]

- Mills, J., & Kuohung, W. (2019). Impact of circadian rhythms on female reproduction and infertility tre atment success. Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes & Obesity, 26(6), 317–321. [CrossRef]

- Mínguez-Alarcón, L., Souter, I., Williams, P. L., Ford, J. B., Hauser, R., Chavarro, J. E., & Gaskins, A. J. (2017). Occupational factors and markers of ovarian reserve and response among women at a fertility centre. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 74(6), 426–431. [CrossRef]

- Mirick, R. G., & Wladkowski, S. P. (2022). Infertility and Pregnancy Loss in Doctoral Education: Understanding Students’ Experiences. Affilia, 38(3), 503–524. [CrossRef]

- Moćkun-Pietrzak, J., Gaworska-Krzemińska, A., & Michalik, A. (2022). A Cross-Sectional, Exploratory Study on the Impact of Night Shift Work on Midwives’ Reproductive and Sexual Health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(13), 8082. [CrossRef]

- Motaung, L. L., Bussin, M. H. R., & Joseph, R. M. (2017). Maternity and paternity leave and career progression of black African women in dual-career couples. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 1(2). [CrossRef]

- Nachtigall, R. D., Tschann, J. M., Quiroga, S. S., Pitcher, L., & Becker, G. (1997). Stigma, disclosure, and family functioning among parents of children c onceived through donor insemination. Fertility and Sterility, 68(1), 83–89. [CrossRef]

- NEPOMNASCHY, P. A., SHEINER, E., MASTORAKOS, G., & ARCK, P. C. (2007). Stress, Immune Function, and Women’s Reproduction. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1113(1), 350–364. [CrossRef]

- Payne, N., Seenan, S., & van den Akker, O. (2018). Experiences and psychological distress of fertility treatment and empl oyment. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 40(2), 156–165. [CrossRef]

- Peters, M. D. J., Marnie, C., Tricco, A. C., Pollock, D., Munn, Z., Alexander, L., McInerney, P., Godfrey, C. M., & Khalil, H. (2021). Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Implementation, 19(1), 3–10. [CrossRef]

- Pollock, D., Peters, M. D. J., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Alexander, L., Tricco, A. C., Evans, C., De Moraes, É. B., Godfrey, C. M., Pieper, D., Saran, A., Stern, C., & Munn, Z. (2022). Recommendations for the extraction, analysis, and presentation of results in scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 21(3), 520–532. [CrossRef]

- Ponzo, S., Wickham, A., Bamford, R., Radovic, T., Zhaunova, L., Peven, K., Klepchukova, A., & Payne, J. L. (2022). Menstrual cycle-associated symptoms and workplace productivity in US employees: A cross-sectional survey of users of the Flo mobile phone app. DIGITAL HEALTH, 8, 205520762211458. [CrossRef]

- Rangel, E. L., Castillo-Angeles, M., Hu, Y.-Y., Gosain, A., Easter, S. R., Cooper, Z., Atkinson, R. B., & Kim, E. S. (2022). Lack of Workplace Support for Obstetric Health Concerns is Associated With Major Pregnancy Complications. Annals of Surgery, 276(3), 491–499. [CrossRef]

- Rayyan. (2024, agosto 7). Available online: https://www.rayyan.ai/.

- Rim, K.-T. (2017). Reproductive Toxic Chemicals at Work and Efforts to Protect Workers’ H ealth: A Literature Review. Safety and Health at Work, 8(2), 143–150. [CrossRef]

- Sabbath, E. L., Willis, M. D., Wesselink, A. K., Wang, T. R., McKinnon, C. J., Hatch, E. E., & Wise, L. A. (2024). Association between job control and time to pregnancy in a preconception cohort. Fertility and Sterility, 121(3), 497–505. [CrossRef]

- Santa-Cruz, D. C., & Agudo, D. (2020). Impact of underlying stress in infertility. Current Opinion in Obstetrics & Gynecology, 32(3), 233–236. [CrossRef]

- Sen, A., & Sellix, M. T. (2016). The Circadian Timing System and Environmental Circadian Disruption: Fr om Follicles to Fertility. Endocrinology, 157(9), 3366–3373. [CrossRef]

- Shifrin, N. V., & Michel, J. S. (2021). Flexible work arrangements and employee health: A meta-analytic review. Work & Stress, 36(1), 60–85. [CrossRef]

- Shreffler, K. M. (2016). Contextual Understanding of Lower Fertility Among U.S. Women in Professional Occupations. Journal of Family Issues, 38(2), 204–224. [CrossRef]

- Silverberg, K., Meletiche, D., & Del Rosario, G. (2009). An employer’s experience with infertility coverage: A case study. Fertility and Sterility, 92(6), 2103–2105. [CrossRef]

- Simoens, S., Dunselman, G., Dirksen, C., Hummelshoj, L., Bokor, A., Brandes, I., Brodszky, V., Canis, M., Colombo, G. L., DeLeire, T., Falcone, T., Graham, B., Halis, G., Horne, A., Kanj, O., Kjer, J. J., Kristensen, J., Lebovic, D., Mueller, M., … D’Hooghe, T. (2012). The burden of endometriosis: Costs and quality of life of women with e ndometriosis and treated in referral centres. Human Reproduction, 27(5), 1292–1299. [CrossRef]

- Slade, P., O’Neill, C., Simpson, A. J., & Lashen, H. (2007). The relationship between perceived stigma, disclosure patterns, suppor t and distress in new attendees at an infertility clinic. Human Reproduction, 22(8), 2309–2317. [CrossRef]

- Sominsky, L., Hodgson, D. M., McLaughlin, E. A., Smith, R., Wall, H. M., & Spencer, S. J. (2017). Linking Stress and Infertility: A Novel Role for Ghrelin. Endocrine Reviews, 38(5), 432–467. [CrossRef]

- Sonika. (2020). Women Reproductive Health and Occupational Safety: A Literature Review. [CrossRef]

- Stanley, N. B., & Foti, T. R. (2020). HEALTH INSURANCE FOR INFERTILITY SERVICES: IT’S ABOUT WHERE YOU WORK, MORE THAN WHERE YOU LIVE. Fertility and Sterility, 114(3), e50. [CrossRef]

- Stearns, J. (2016). The Long-Run Effects of Wage Replacement and Job Protection: Evidence from Two Maternity Leave Reforms in Great Britain. SSRN Electronic Journal. [CrossRef]

- Steyn, F., Kearns, B., Pericleous-Smith, A., & Imogen, C. (2024). P-455 Exploring the impact of fertility care on the modern workforce: Key research findings. Human Reproduction, 39(Supplement_1). [CrossRef]

- Steyn, F., Sizer, A., & Pericleous-Smith, A. (2022). P-486 Fertility in the workplace: The emotional, physical and psycholo gical impact of infertility in the workplace. Human Reproduction, 37(Supplement_1). [CrossRef]

- Stock, D., & Schernhammer, E. (2019). Does night work affect age at which menopause occurs? Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes & Obesity, 26(6), 306–312. [CrossRef]

- Stocker, L. J., Macklon, N. S., Cheong, Y. C., & Bewley, S. J. (2014). Influence of Shift Work on Early Reproductive Outcomes. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 124(1), 99–110. [CrossRef]

- Toth, K. E., & Dewa, C. S. (2014). Employee Decision-Making About Disclosure of a Mental Disorder at Work. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 24(4), 732–746. [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. [CrossRef]

- van den Akker, O. B. A., Payne, N., & Lewis, S. (2017). Catch 22? Disclosing assisted conception treatment at work. International Journal of Workplace Health Management, 10(5), 364–375. [CrossRef]

- Virgillito, D., Catalfo, P., & Ledda, C. (2025). Wearables in Healthcare Organizations: Implications for Occupational Health, Organizational Performance, and Economic Outcomes. Healthcare, 13(18), 2289. [CrossRef]

- WAN, G., & CHUNG, F. (2011). Working conditions associated with ovarian cycle in a medical center nurses: A Taiwan study. Japan Journal of Nursing Science, 9(1), 112–118. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., & Tan, J. (2024). Negotiating Work and Family Spheres: The Dyadic Effects of Flexible Work Arrangements on Fertility Among Dual-Earner Heterosexual Couples. Demography, 61(4), 1241–1265. [CrossRef]

- Webster, J. R., Adams, G. A., Maranto, C. L., Sawyer, K., & Thoroughgood, C. (2017). Workplace contextual supports for LGBT employees: A review, meta-analy sis, and agenda for future research. Human Resource Management, 57(1), 193–210. [CrossRef]

- Winker, R., & Rüdiger, H. W. (2005). Reproductive toxicology in occupational settings: An update. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 79(1), 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Yaw, A., McLane-Svoboda, A., & Hoffmann, H. (2020). Shiftwork and Light at Night Negatively Impact Molecular and Endocrine Timekeeping in the Female Reproductive Axis in Humans and Rodents. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(1), 324. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J. L., Hjollund, N. H., Boggild, H., & Olsen, J. (2003). Shift work and subfecundity: A causal link or an artefact? Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 60(9), e12–e12. [CrossRef]

| Element | Description | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population | Adult female employees with endometriosis | Women aged ≥18 years with a clinically confirmed diagnosis of endometriosis, employed in any sector | Males, non-employed individuals, or women without confirmed diagnosis of endometriosis |

| Concept | Organizational factors affecting reproductive and work outcomes | Studies addressing workplace policies, organizational dysfunction, workplace accommodations, and their impact on fertility, absenteeism, or productivity | Studies not addressing organizational/workplace dimensions or outcomes related to fertility, absenteeism, or productivity |

| Context | Formal employment settings across sectors and regions | Studies conducted in formal workplace environments (any industry or geographical location) | Studies in informal work contexts, unpaid labor, or non-employment settings (e.g., homemaking, student populations) |

| Study | Study design | Population | Workplace factors | Primary outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson and Goldman, 2020 (Anderson & Goldman, 2020) | Quantitative (retrospective studies) | Female surgeons | Operating room hazards, working conditions | Infertility, pregnancy complications |

| Armijo et al., 2021 (Armijo et al., 2021) | Quantitative (survey) | 377 women physicians | Training demands, work hours, breastfeeding support | Childbearing trends, fertility issues, barriers |

| Barzilai-Pesach et al., 2006 (Barzilai-Pesach et al., 2006) | Quantitative (prospective cohort) | 75 working women (fertility problem) | Job stress, workload, satisfaction | Fertility treatment outcomes |

| Castillo-Angeles et al., 2022 (Castillo-Angeles et al., 2022) | Quantitative (survey) | 692 female surgeons with live birth | Workplace support for work reduction during pregnancy/neonatal complications | Postpartum depression, income loss |

| De Oliveira Trigo et al., 2023 (De Oliveira Trigo et al., 2023) | Mixed methods | 107 workers, 24 employers (Portugal) | Fertility-friendly policies, support | Career progression, anxiety, disclosure |

| Fernandez-Pineda et al., 2025 (Fernandez-Pineda et al., 2025) | Qualitative (interviews) | 13 women post-miscarriage | Work-related stress, accommodations, support | Emotional distress, work performance |

| Gilbert et al., 2023 (Gilbert et al., 2023) | Qualitative (interviews) | 29 working women | Pregnancy loss, workplace stigma, support | Work outcomes, wellbeing, return-to-work |

| Győrffy et al., 2014 (Győrffy et al., 2014) | Quantitative (survey) | 3,039 female physicians (Hungary) | Burnout, workload | Reproductive disorders, burnout |

| Herweck et al., 2025 (Herweck et al., 2025) | Quantitative (retrospective) | 1,586 patients at academic center | Expanded fertility benefits | Access, utilization, demographics |

| Hvala and Hammarberg, 2025 (Hvala & Hammarberg, 2025) | Qualitative (interviews) | 12 employed women with endometriosis, adenomyosis, or infertility | Reproductive health needs, workplace flexibility, sick leave | Impact on work ability, career progression, support needs |

| Izadi et al., 2024 (Izadi et al., 2024) | Quantitative (cross-sectional) | 733 female healthcare workers (Iran) | Chemical, ergonomic, shift work | Reproductive outcomes, breastfeeding |

| Jou et al., 2016 (Jou et al., 2016) | Quantitative (survey) | 700 US women (postpartum) | Paid/unpaid maternity leave | Health insurance coverage, turnover |

| Kim and Parish, 2020 (Kim & Parish, 2020) | Quantitative (survey) | 3,405 Korean working women | Family-supportive policies, benefits | Fertility intentions (by parity) |

| Lwin et al., 2024 (Lwin et al., 2024) | Quantitative (survey) | 557 US surgeons | Workplace support during pregnancy | Burnout, career satisfaction |

| Maeda et al., 2022 (Maeda et al., 2022) | Quantitative (cross-sectional survey) | 721 Japanese women (25-44, employed, fertility care) | Job stress, working hours, time off, partner support | Fertility-related quality of life |

| Metcalfe et al., 2011 (Metcalfe et al., 2011) | Quantitative (survey) | 836 Canadian women (postpartum) | Parental leave, workplace support | Timing of first pregnancy |

| Mínguez-Alarcón et al., 2017 (Mínguez-Alarcón et al., 2017) | Quantitative (prospective cohort, survey) | 473/313 women at fertility center | Physically demanding work, shift work | Ovarian reserve, oocyte yield |

| Mirick and Wladkowski, 2022 (Mirick & Wladkowski, 2022) | Qualitative (interviews) | 328 women doctoral students | Infertility, pregnancy loss, institutional support | Productivity, support needs |

| Moćkun-Pietrzak et al., 2022 (Moćkun-Pietrzak et al., 2022) | Quantitative (survey) | 520 midwives (Poland) | Shift work, night shifts | Infertility, miscarriage, sexual health |

| Payne et al., 2019 (Payne et al., 2018) | Quantitative (online survey) | 563 UK employees (fertility treatment) | Work-treatment conflict, policy | Absence, career impact, distress |

| Ponzo et al., 2022 (Ponzo et al., 2022) | Quantitative (survey) | 1,867 US employees (Flo app users) | Menstrual symptoms, workplace support | Productivity, absenteeism |

| Rangel et al., 2022 (Rangel et al., 2022) | Quantitative (survey) | 671 US surgeons (likely female) | Workplace support for clinical work reduction during pregnancy | Major pregnancy complications, workplace support |

| Sabbath et al., 2023 (Sabbath et al., 2024) | Quantitative (cohort) | 3,110 women (21-45, US/Canada) | Job control, independence, decision-making | Fecundability (time to pregnancy) |

| Shreffler, 2017 (Shreffler, 2016) | Quantitative (survey) | 1,800 US women (employed) | Professional job characteristics | Fertility intentions, behaviors |

| Silverberg et al., 2009 (Silverberg et al., 2009) | Mixed methods (case study, survey) | Employees of Southwest Airlines, 605 employers | Infertility coverage, managed care | Resource use, morale, retention |

| Stanley and Foti, 2020 (Stanley & Foti, 2020) | Qualitative (interviews) | 66 individuals, 8 experts | Employer insurance, state mandates | Access to infertility services |

| Steyn et al., 2022 (Steyn et al., 2022) | Quantitative (survey) | 1,557 UK employees | Fertility journey, workplace support | Wellbeing, job satisfaction, absence |

| Steyn et al., 2024 (Steyn et al., 2024) | Quantitative (survey) | 1,031 UK employees | Fertility support, workplace policies | Fertility challenges, productivity, retention |

| Wan and Chung, 2012 (WAN & CHUNG, 2011) | Quantitative (survey) | 200 nurses (Taiwan) | Shift work, unit type | Ovarian cycle pattern |

| Wang and Tan, 2024 (Wang & Tan, 2024) | Quantitative (longitudinal) | Dual-earner UK couples | Flexible work arrangements | Fertility (first birth probability) |

| Thematic Domain |

Studies | Key Workplace Factors | Reported Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shift Work and Circadian Disruption | (Izadi et al., 2024; Mínguez-Alarcón et al., 2017; Moćkun-Pietrzak et al., 2022; WAN & CHUNG, 2011) | Night shifts, rotating schedules, chemical and ergonomic exposures, physically demanding work | Infertility, miscarriage, reduced ovarian reserve, disrupted ovarian cycles, adverse reproductive outcomes |

| Organizational Stress and Burnout | (Armijo et al., 2021; Barzilai-Pesach et al., 2006; Győrffy et al., 2014) | Job stress, heavy workload, training demands, burnout, lack of breastfeeding support | Reproductive disorders, negative fertility treatment outcomes, barriers to childbearing, burnout |

| Workplace Flexibility and Accommodations | (Castillo-Angeles et al., 2022; Fernandez-Pineda et al., 2025; Gilbert et al., 2023; Hvala & Hammarberg, 2025; Maeda et al., 2022; Mirick & Wladkowski, 2022; Ponzo et al., 2022) | Working hours, workload reduction during pregnancy, sick leave, accommodations for reproductive health, workplace stigma | Fertility-related quality of life, postpartum depression, emotional distress, absenteeism, productivity loss, career impact |

| Fertility-Related Policies and Organizational Support | (Anderson & Goldman, 2020; De Oliveira Trigo et al., 2023; Herweck et al., 2025; Jou et al., 2016; Kim & Parish, 2020; Lwin et al., 2024; Metcalfe et al., 2011; Rangel et al., 2022; Sabbath et al., 2024; Shreffler, 2016; Silverberg et al., 2009; Stanley & Foti, 2020; Steyn et al., 2022, 2024; Wang & Tan, 2024) | Paid/unpaid maternity leave, fertility benefits, family-supportive policies, flexible work arrangements, employer insurance, stigma policies | Fertility intentions, access to services, employee retention, morale, job satisfaction, wellbeing, fecundability, pregnancy complications, productivity and career outcomes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).