Submitted:

16 October 2025

Posted:

17 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- (1)

- What’s a simple system in statistical mechanics that manifests structure and patterns?

- (2)

- How could one extend statistical mechanics to formalize structure and patterns within such a system?

2. Background

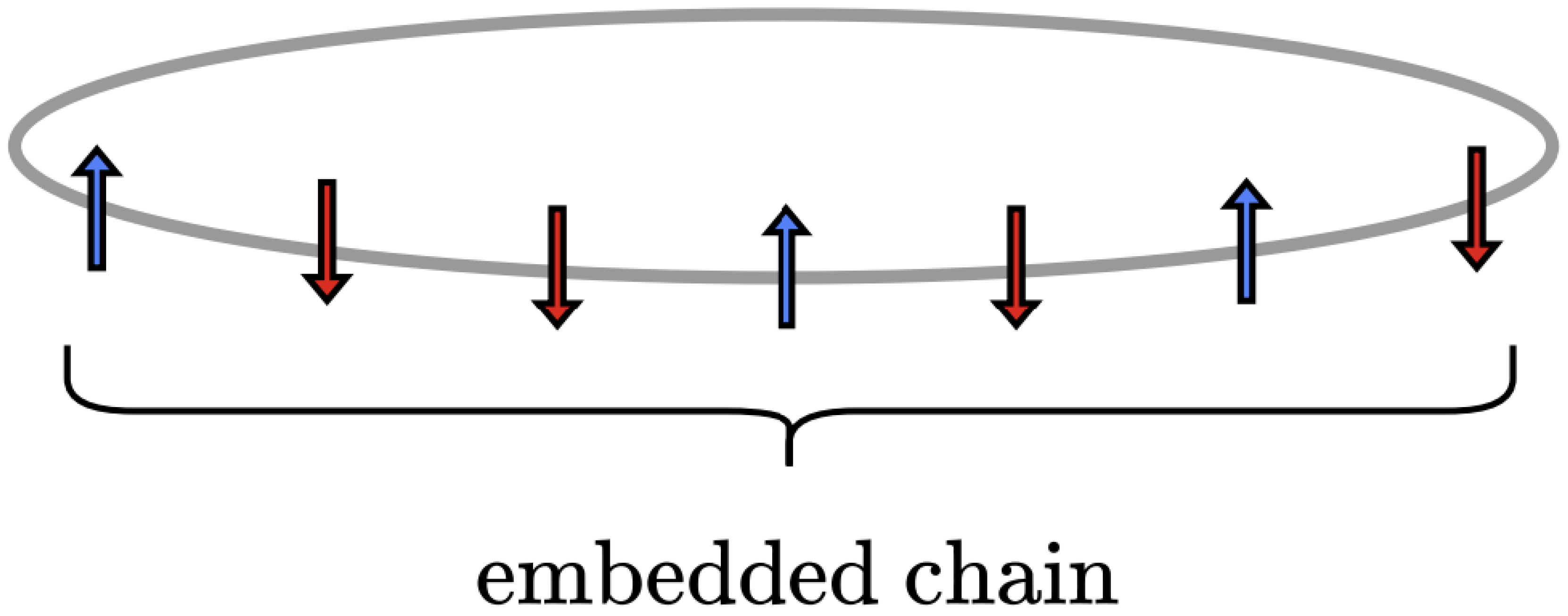

2.1. Spin Measurements: Boltzmann Distribution of Finite Chain Embedded in Infinite Chain

- In the denominator, is raised to as each embedded configuration has L spins and its boundaries are not periodic.

- In the numerator, the product of transfer matrix components consists of factors. This reflects the fact that only the spins within the bulk have neighboring spins to interact with on both their left and right sides.

- Also in the numerator, we include two extra terms: and , which are the normalized principal eigenvector components associated with the boundary spins and . Since the embedded configuration does not have periodic boundaries, these extra terms ensure that the boundary spins contribute to the system’s magnetization as much as the bulk spins. Moreover, these terms are key for normalizing the joint probabilities.

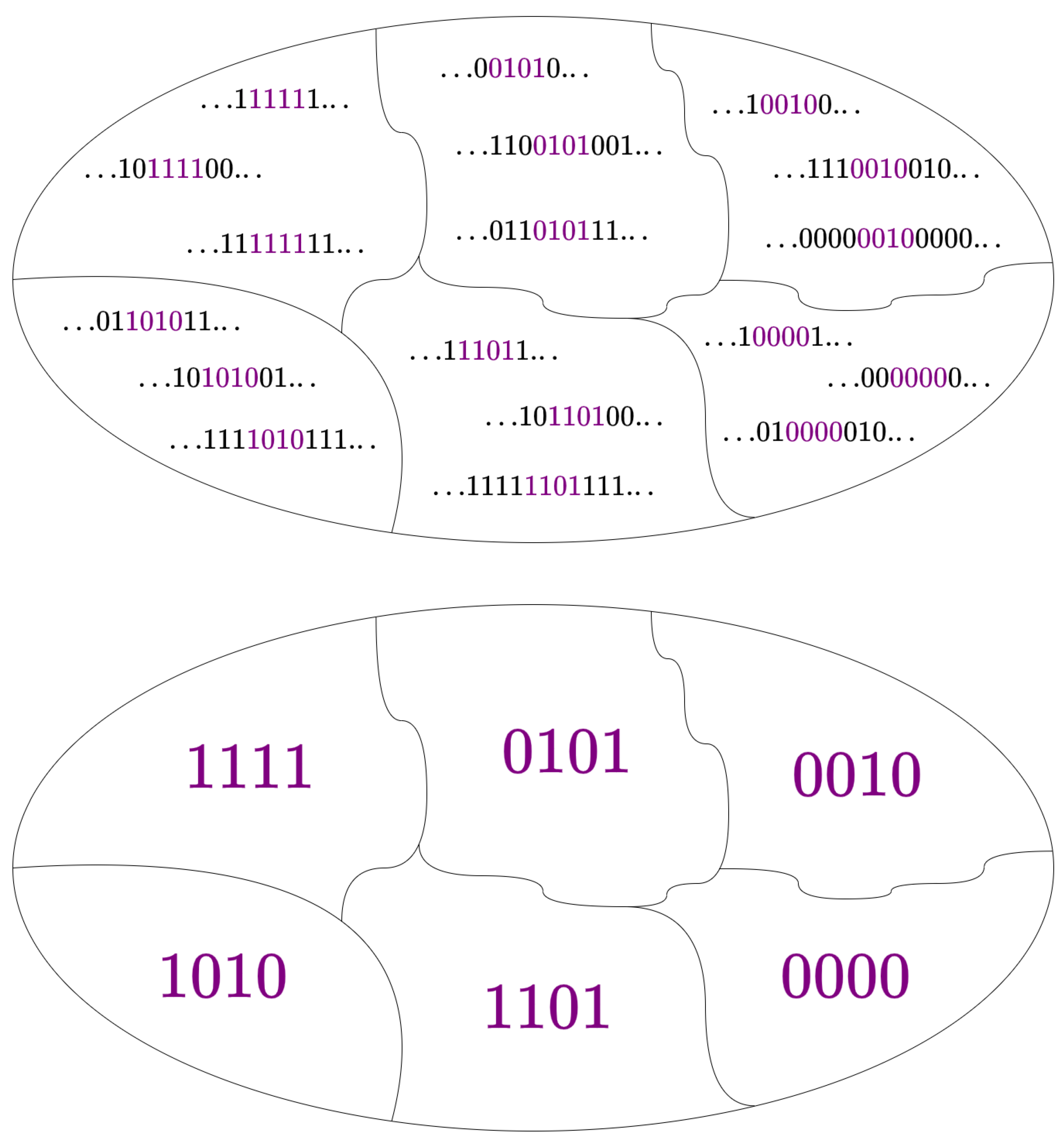

2.2. Coarse-Graining via Measure Theory

- Entire Set Containment: includes the sample space. In this case, that is the coarse-grained set of all infinite configurations :

- Complement Closure: If a set A is in , then its complement must also be in :

- Countable Union Closure: If are in , then their countable union is also in :

- Nonnegativity: In the same way that joint probabilities for finite configurations are never negative, the probability measure assigned to any set in must also be nonnegative.

- Normalization: Similar to the sum of joint probabilities for all configurations equaling 1, the probability measure for the entire sample space, the set of coarse-grained configurations , must be 1.

- Countable addivity: Mirroring the additivity of joint probabilities, which asserts that the total probability of finite configurations equals the sum of their individual probabilities, probability measures demonstrate countable additivity. This property dictates that for any countable collection of non-overlapping sets (cylinder sets) , the probability of their union is the sum of the probabilities of the individual sets:where each is a cylinder set corresponding to a coarse-grained configuration, and the union represents the combined event of these configurations.

2.3. System and Measurements: Stochastic Processes

2.3.1. Types of Processes

Stationary process

Strictly stationary process

Markovian process

R-order Markovian process

Spin process

2.4. Information Measures

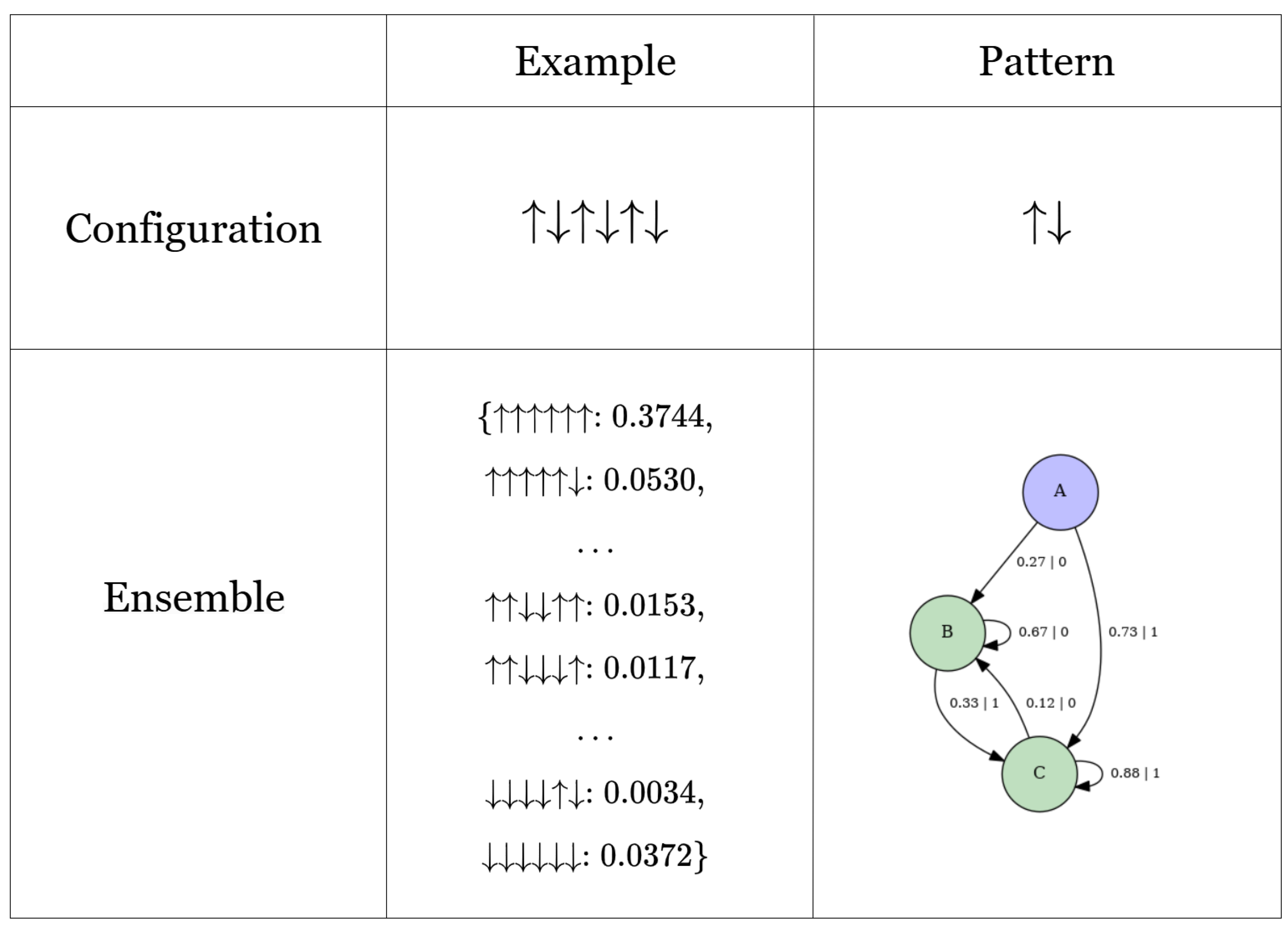

2.5. Structure: Computational Mechanics

- Be capable of reproducing ensembles

- Possess a well-defined notion of “state"

- Be derivable from first principles

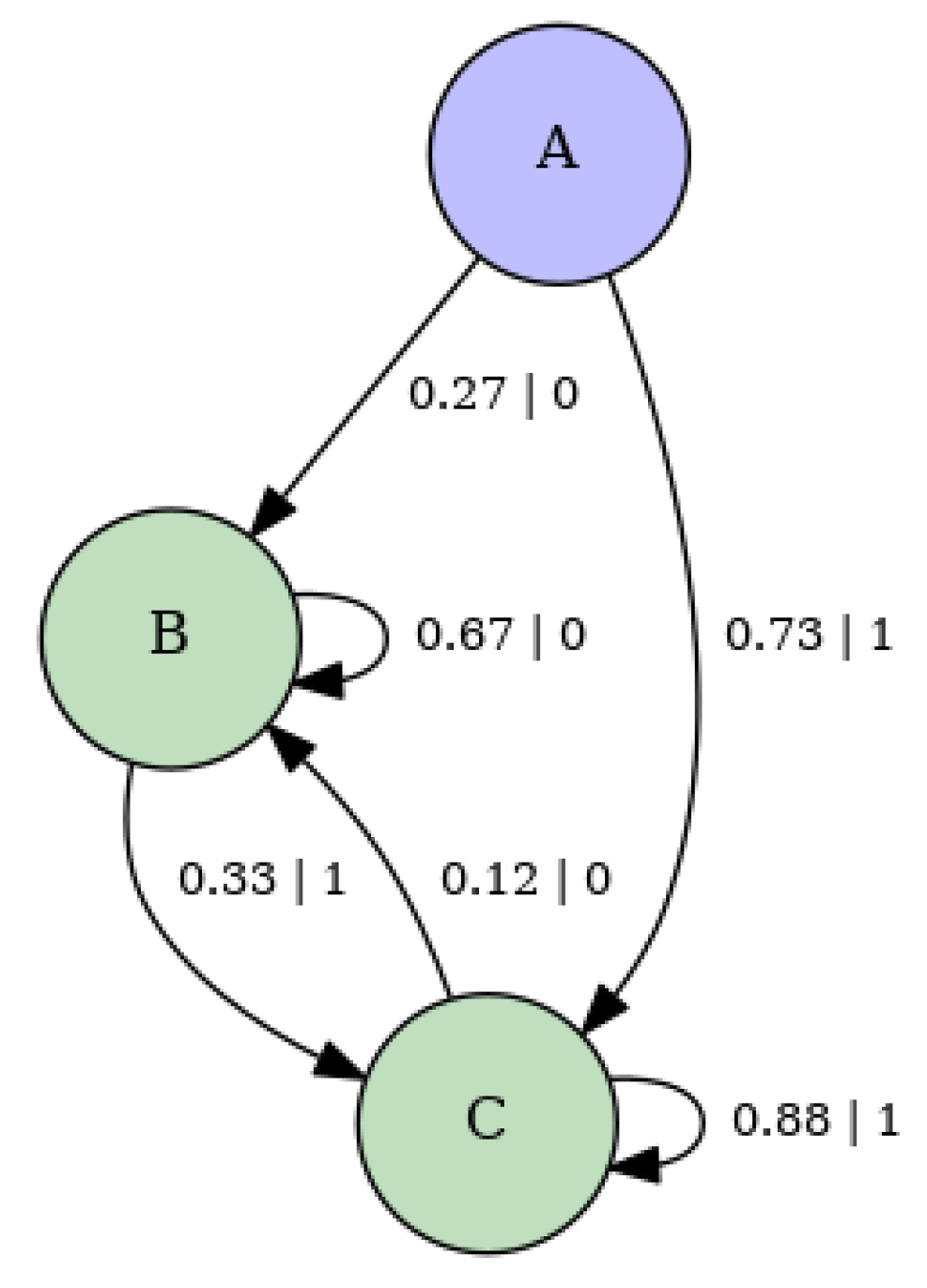

- An event with its associated probability of the causal state random variable :

- A distribution of the future conditioned on the causal event, i.e., a morph:

- The set of histories that lead to the same morph:

- The set of causal states

- Transition dynamic (causal transitions gathered in a matrix) [27]

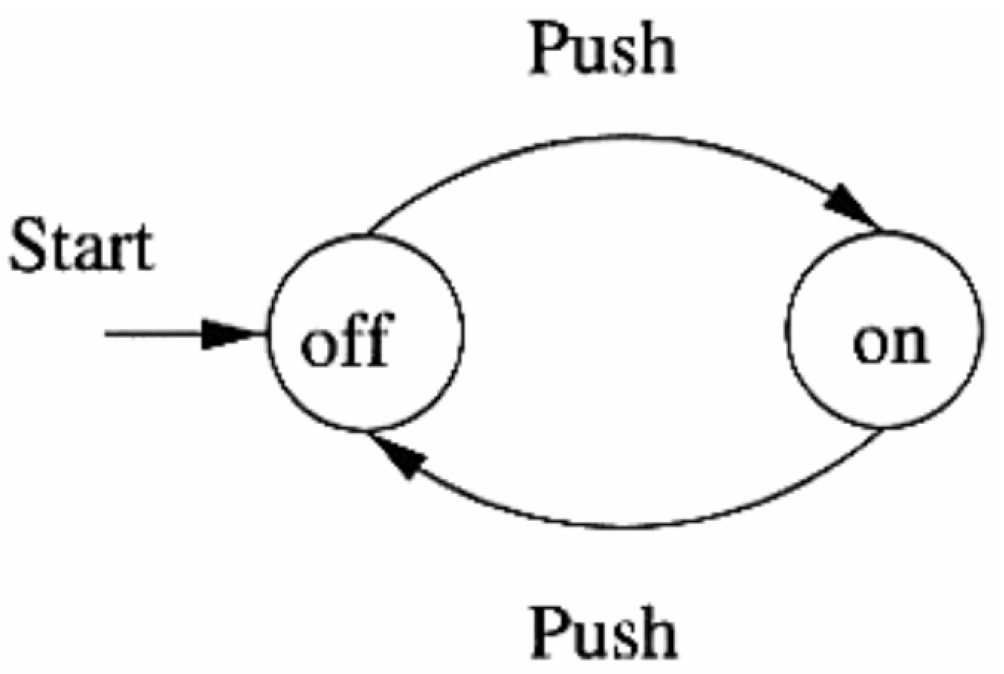

- Recurrent causal states: These are states to which the machine will repeatedly transition as it operates. Consequently, their asymptotic probability is non-zero.

- Transient causal states: These are states that the machine may reach temporarily but will not return to. As a result, their asymptotic probability is zero: .

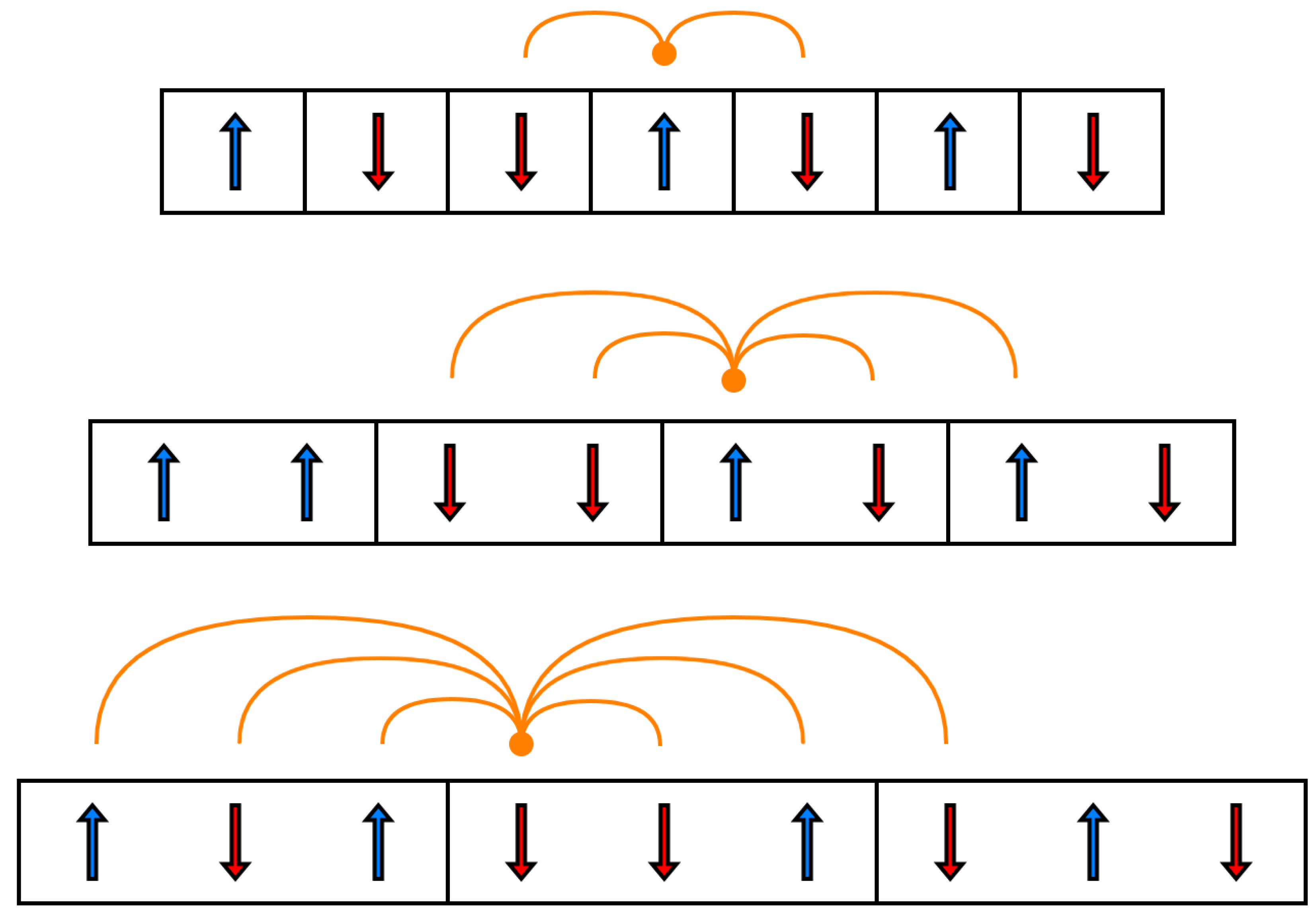

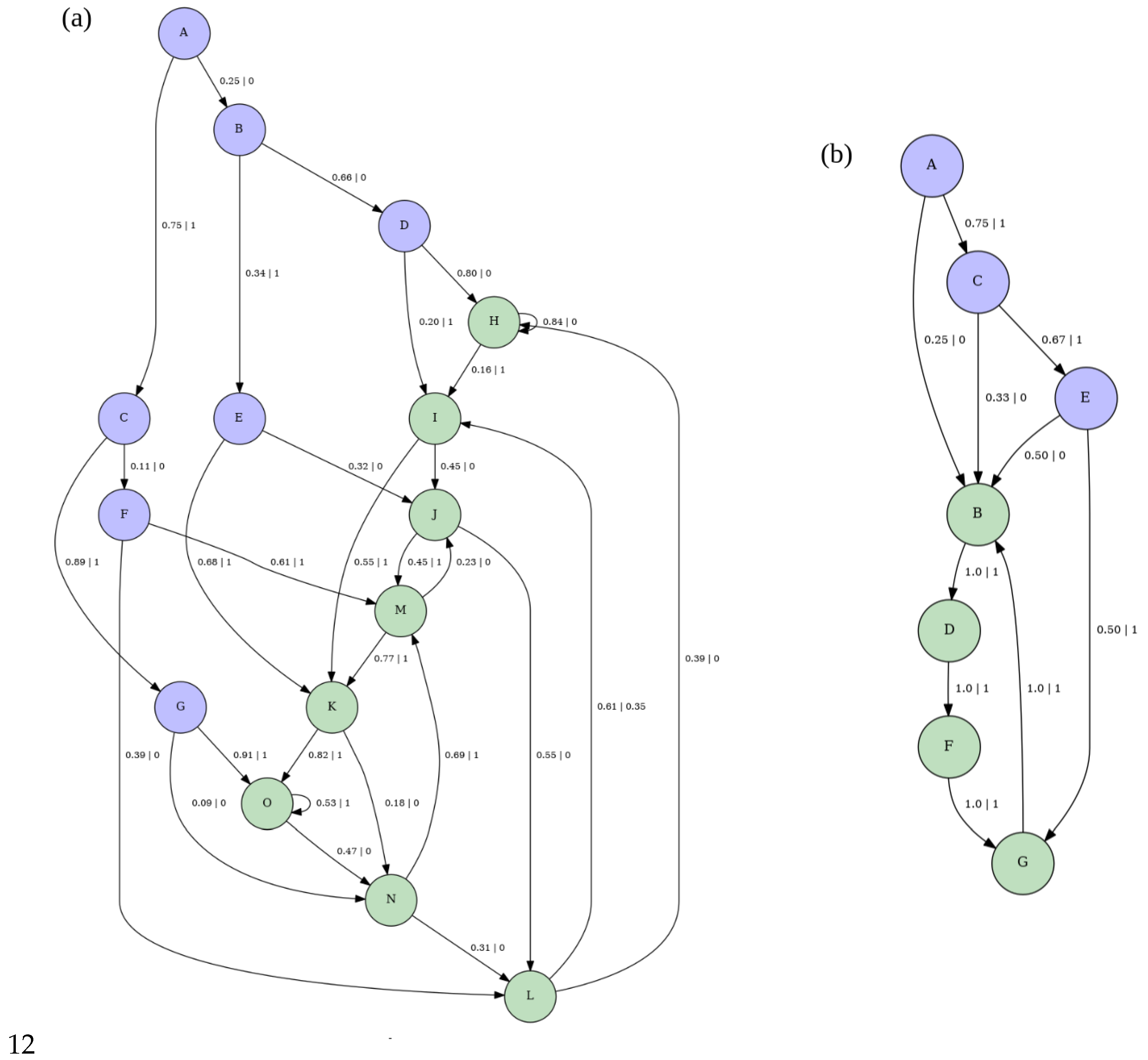

2.5.1. Analytical Method to Infer -Machines

- Consider a finite configuration of length embedded in an infinite one.

- Consider the joint probability of the embedded finite configuration.

- Compute the conditional probability of the right half of the configuration given the left half.

- Notice that the only past element the conditional probability depends on is its last spin . Thus, the conditional probability is Markovian.

- Identify morphs.

-

Identify the number of causal states.Since there are two morphs, there are twocausal states at most

- Identify sets of histories that lead to the same morph.

- Apply definition of causal transitions.

-

Calculate asymptotic causal state probabilities using two facts:Since , by inspection, we have

- Build transition dynamic T.

-

Find left eigenvector using .

- Build HMM representation of -machine using the transition matrix . Details of the resulting machine, for the parameter values , , and , are provided in Appendix E.

2.6. Patterns as -Machines

3. Spin Models

- Randomness Parameter: This parameter governs the degree of randomness within the system. As it increases, it leads configurations to become more uniformly likely. In the nn Ising model, temperature T usually fulfills this role.

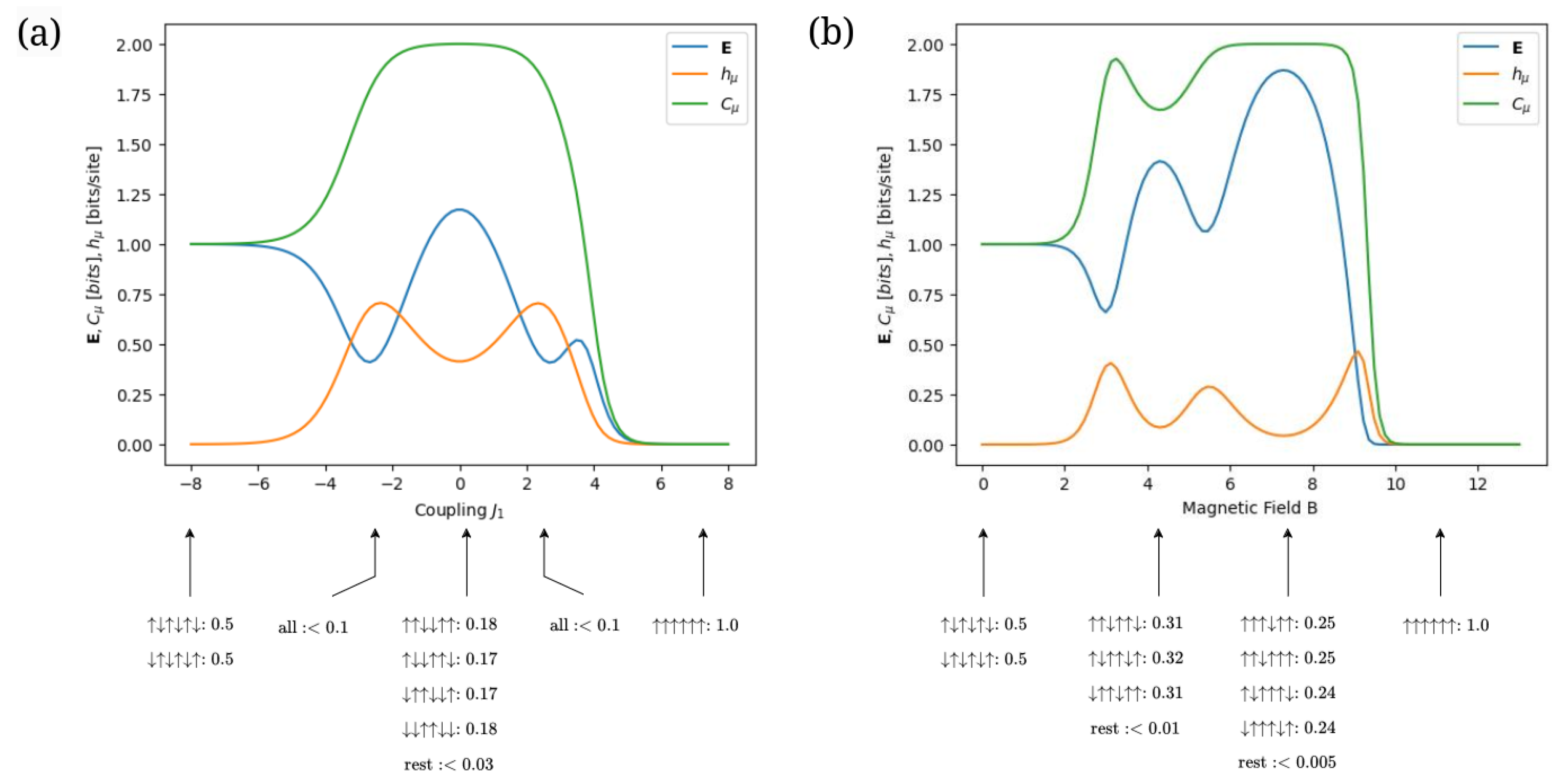

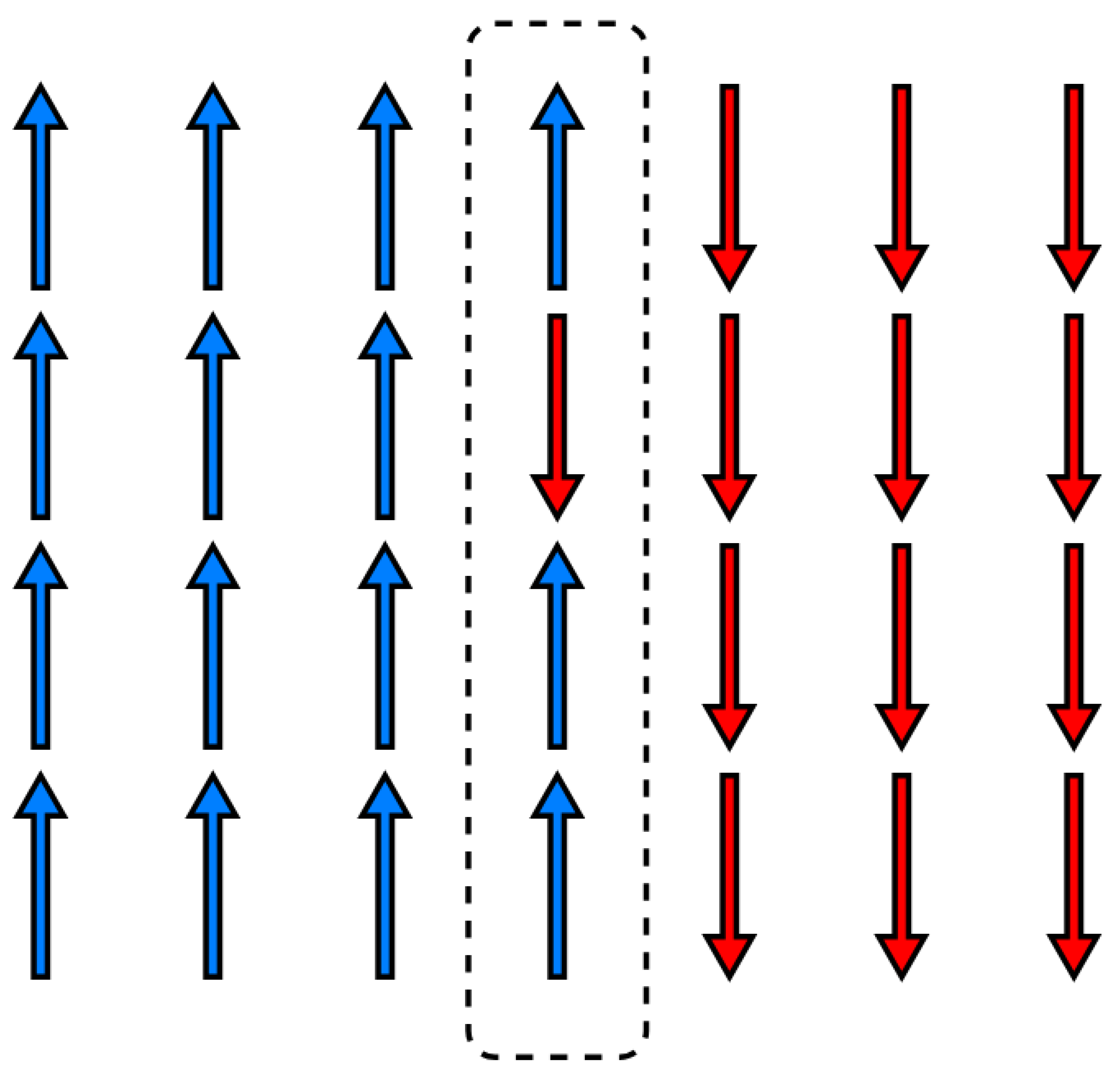

- Periodicity Parameter (Type 1): This parameter enhances periodicity and, as it varies, biases the system toward configurations that consist exclusively of a single period. In the nn Ising model, the coupling constant B exemplifies this. It induces period 1 configurations whether B is significantly positive or negative. Specifically, a high positive B biases all spins to point upwards, while a high negative B results in all spins pointing downwards.

- Periodicity Parameter (Type 2): Similarly, this parameter enhances periodicity but, as it varies, steers the system towards typical configurations with multiple distinct periods. In the nn Ising model, this role is played by the coupling constant J. A high positive J value tends to produce period 1 configurations (all spins up), akin to B, but a negative J value leads to alternating spin configurations (e.g., up-down-up-down), indicating that the typical configuration can be of period 2.

3.1. Finite-Range Ising Model

- represents the energy contribution from the interactions between each spin in the block and the magnetic field B. For , configurations tend to have all spins pointing up, while for all spins pointing down are favored. Therefore, B acts as a type-1 periodicity parameter.

- represents the energy from the neighbor interactions between the spins within block . For , spins tend to align either all up or all down, favoring period-1 configurations. When , spin configurations of period- are prone to occur. Thus, serves as a type-2 periodicity parameter.

- denotes the energy associated with interactions between spins in neighboring blocks and . Since this term shares the same form and coupling as , it leads to the same configuration patterns for corresponding values of . Thus, again acts as a type-2 periodicity parameter.

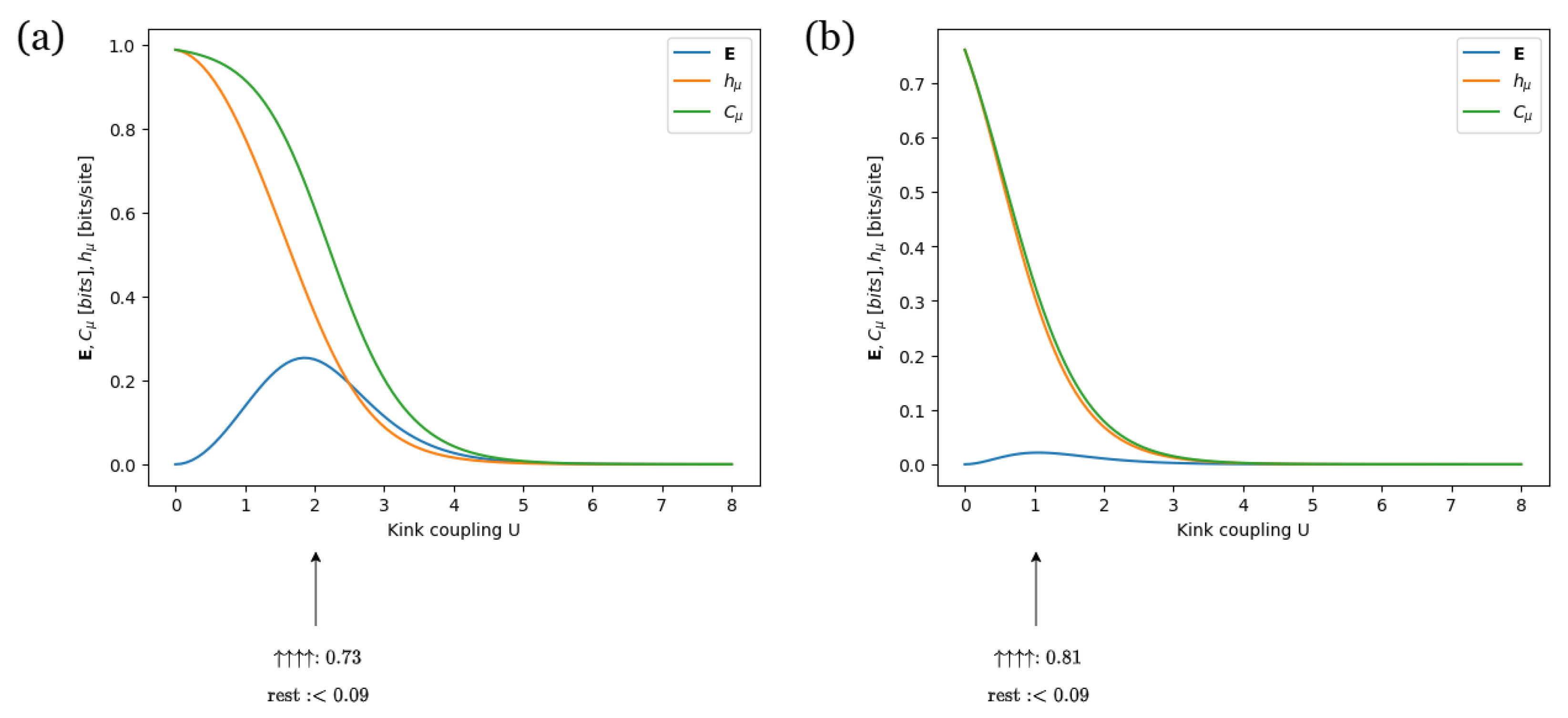

3.2. Solid on Solid Model

- represents the energy cost of forming a kink in the interface. biases the system toward period-1 configurations, while favors alternating spins. Therefore, U acts as a periodicity parameter of type 2.

- represents the energy associated with pinning the interface to the wall [79]. For , prevails, while for , dominates. In both cases, the system favors period-1 configurations. Thus, W serves as a type 1 periodicity parameter.

- represents the energy contribution from an external field that influences the interface’s orientation or tilt [79]. For , an interface made up of 1s is favored, while for , an interface made up of 0s is preferred. Therefore, the parameters in this term function as type-1 periodicity parameters.

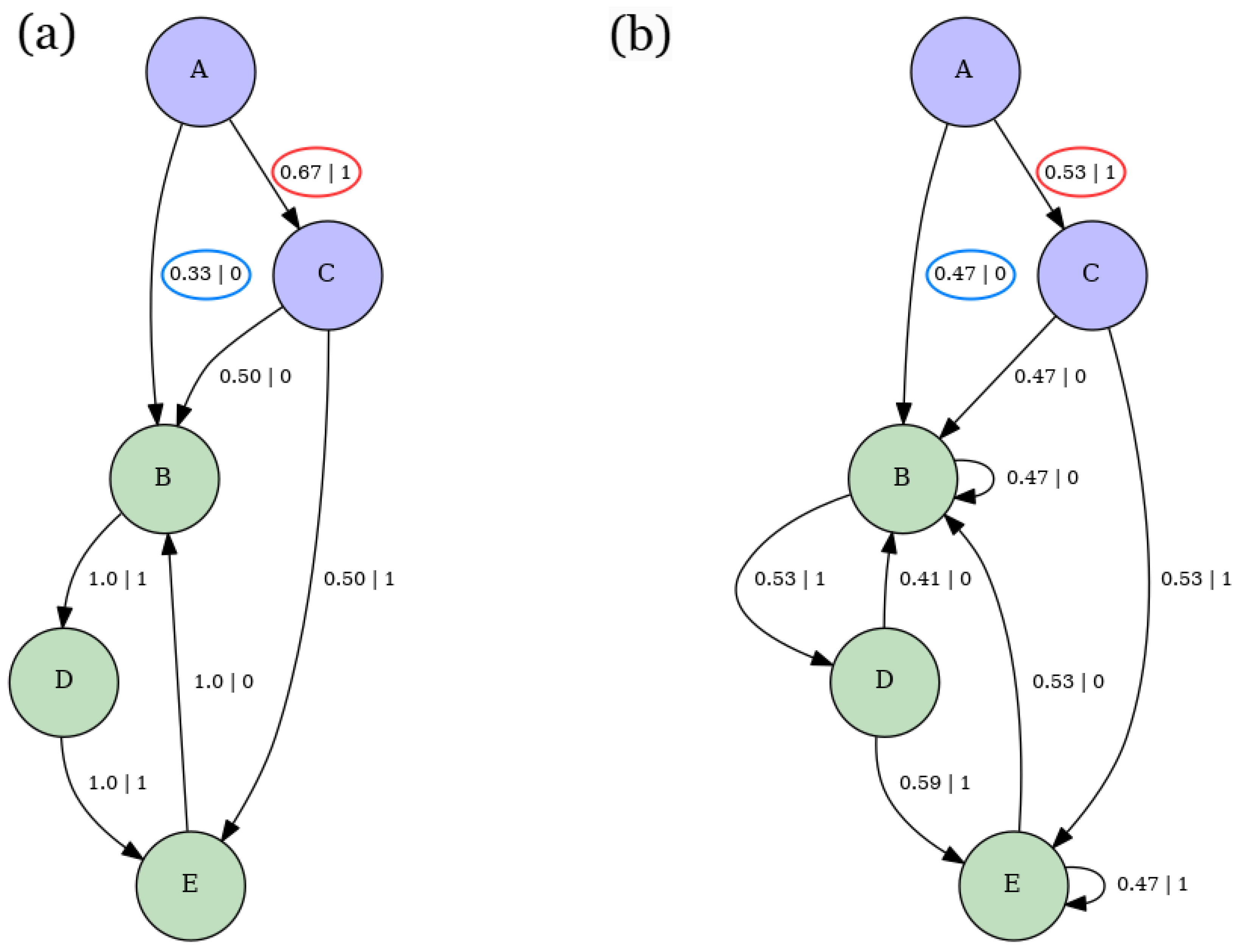

3.3. Three-Body Model

- The splitting of thermal desorption peaks becomes progressively weaker as one goes from Ni to Ru

- The integral intensities of the peaks are distinct

- is the term associated with the nearest-neighbor coupling. For , the model induces period-1 configurations, while for , the model induces period-2 configurations. Thus, serves as a type-2 periodicity parameter.

- is the energy contribution of the next-nearest-neighbour coupling. When , the model tends toward period-1 configurations, whereas for , it leans toward period-4 configurations. Therefore, acts as a periodicity parameter of type 2.

- is the expression that represents the three-body interaction. When , the configurations are biased toward a period-1 pattern, while favors period-4 configurations. As a result, functions as a type 2 periodicity parameter.

4. Conclusion

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Appendix A. Concept of “State" in Theory of Computation and Its Formalization in Computational Mechanics

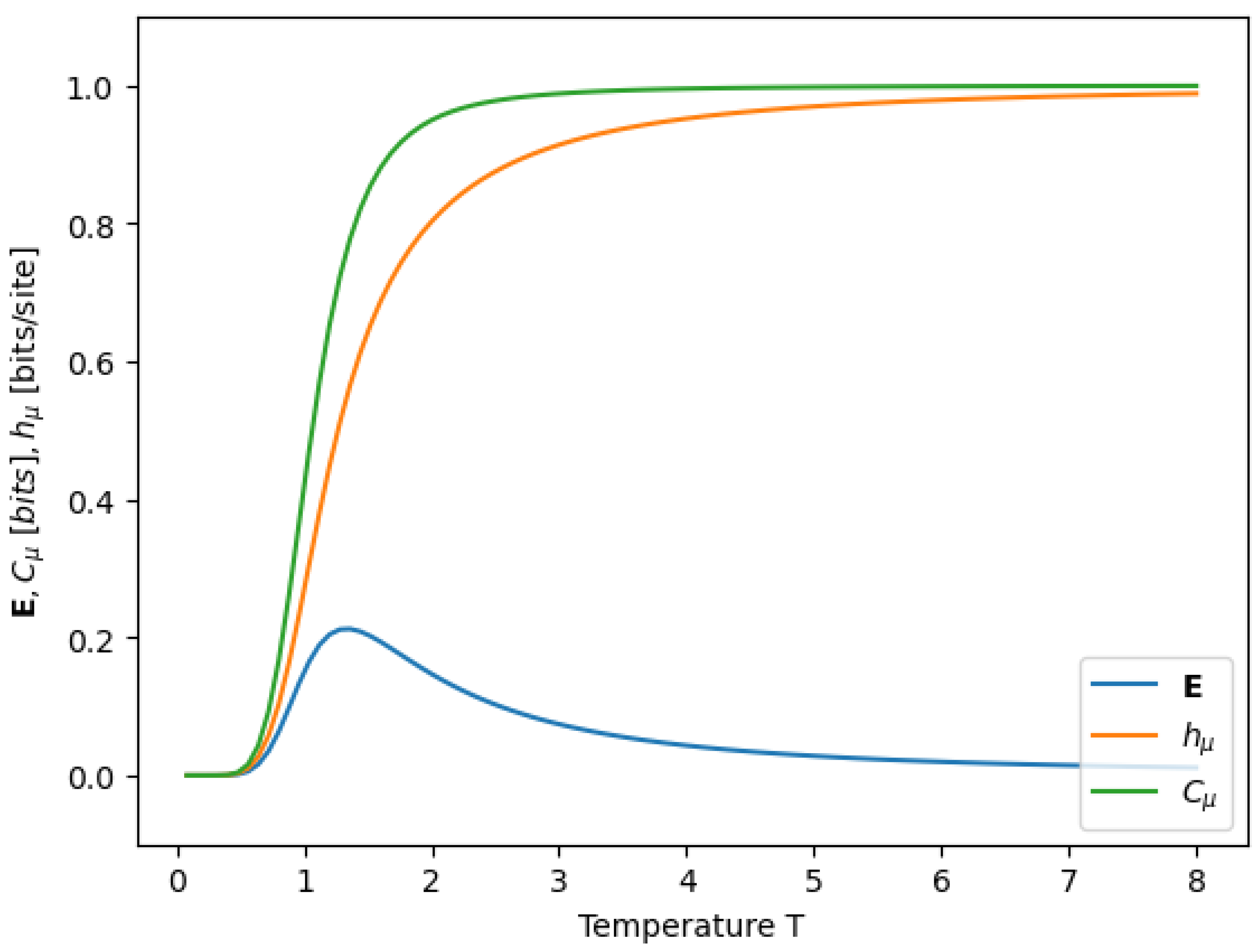

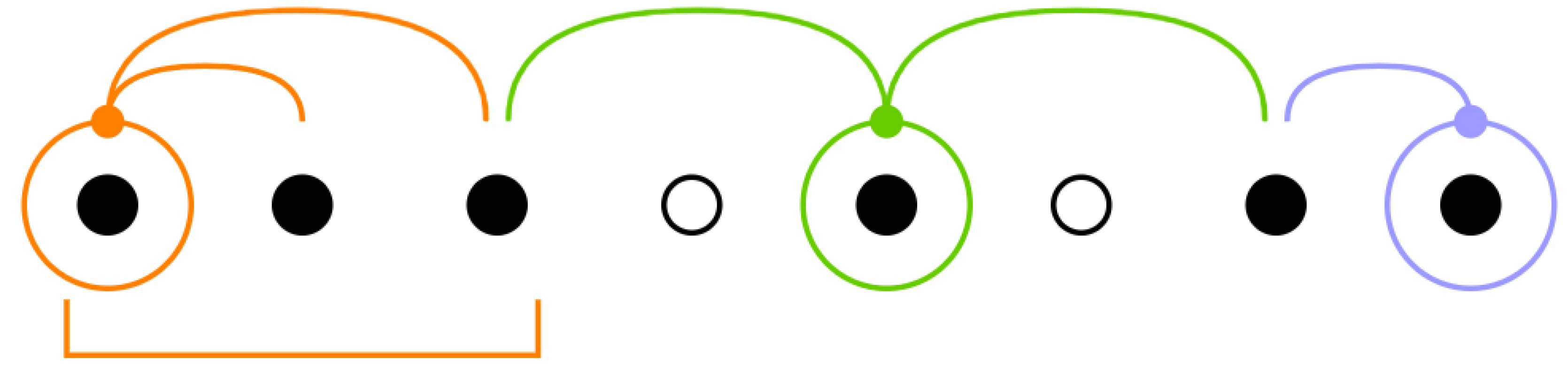

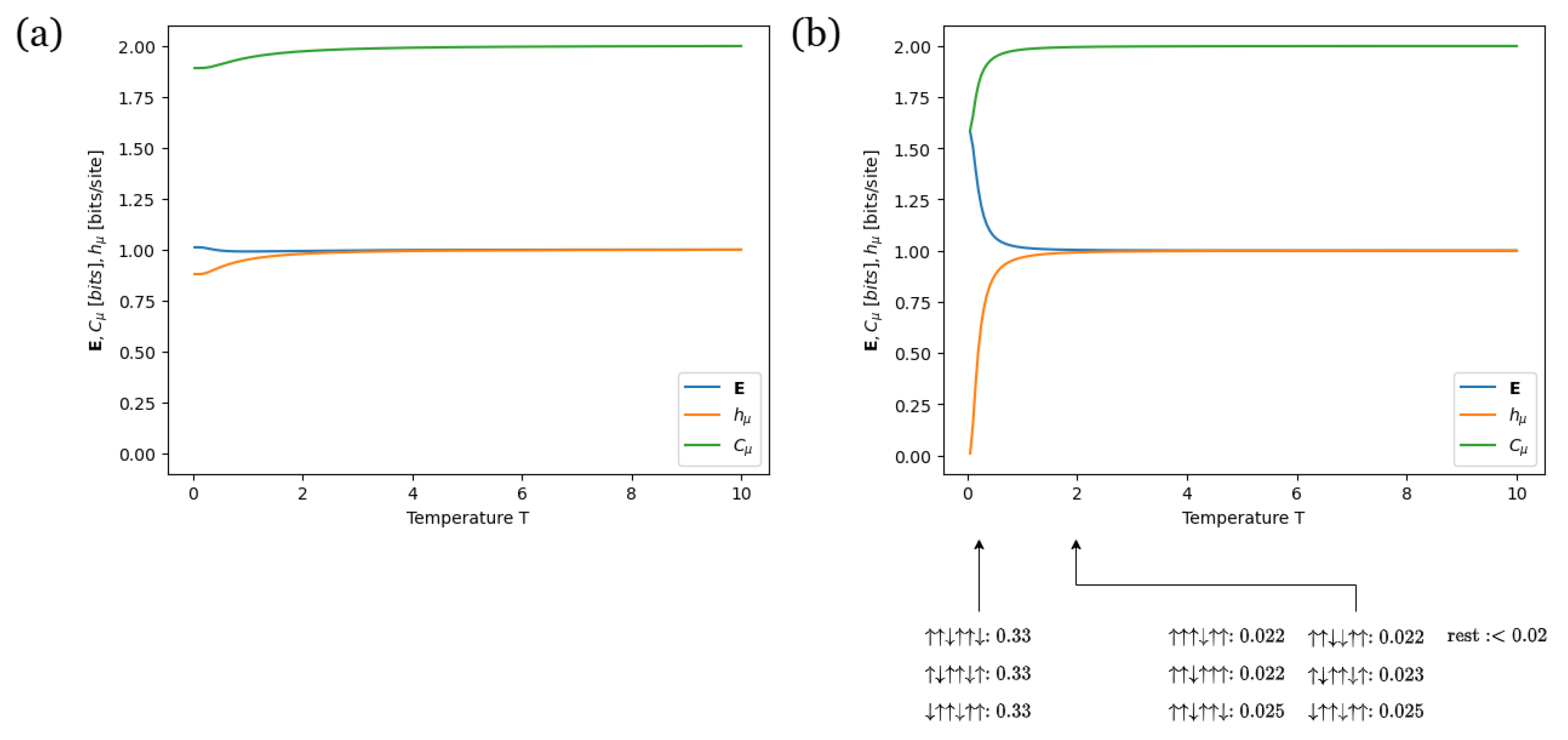

Appendix B. Information Measures Across Varying Temperature in a Nearest-Neighbor Ising Model

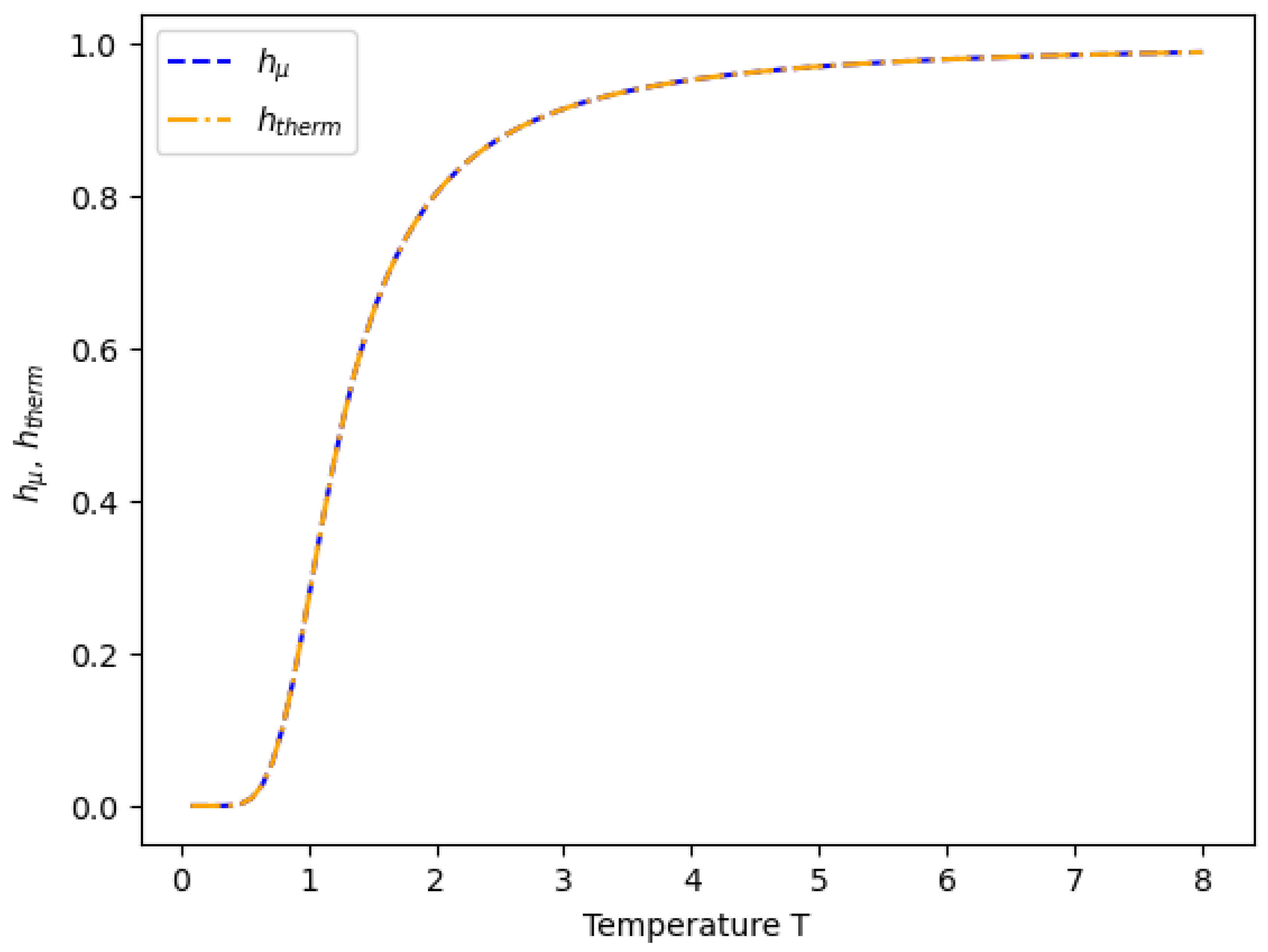

Appendix C. Shannon Entropy Density h μ and Boltzmann Entropy Density h therm

Appendix D. Derivation of Boltzmann (Thermodynamic) Entropy Density for Nearest-Neighbor Ising Model

- Consider

- Using the chain rule:

- Rewrite in terms of

- Split principal eigenvalue into two terms

- Carry out and

- Simplify

- Simplify

- Simplify

- Replace in

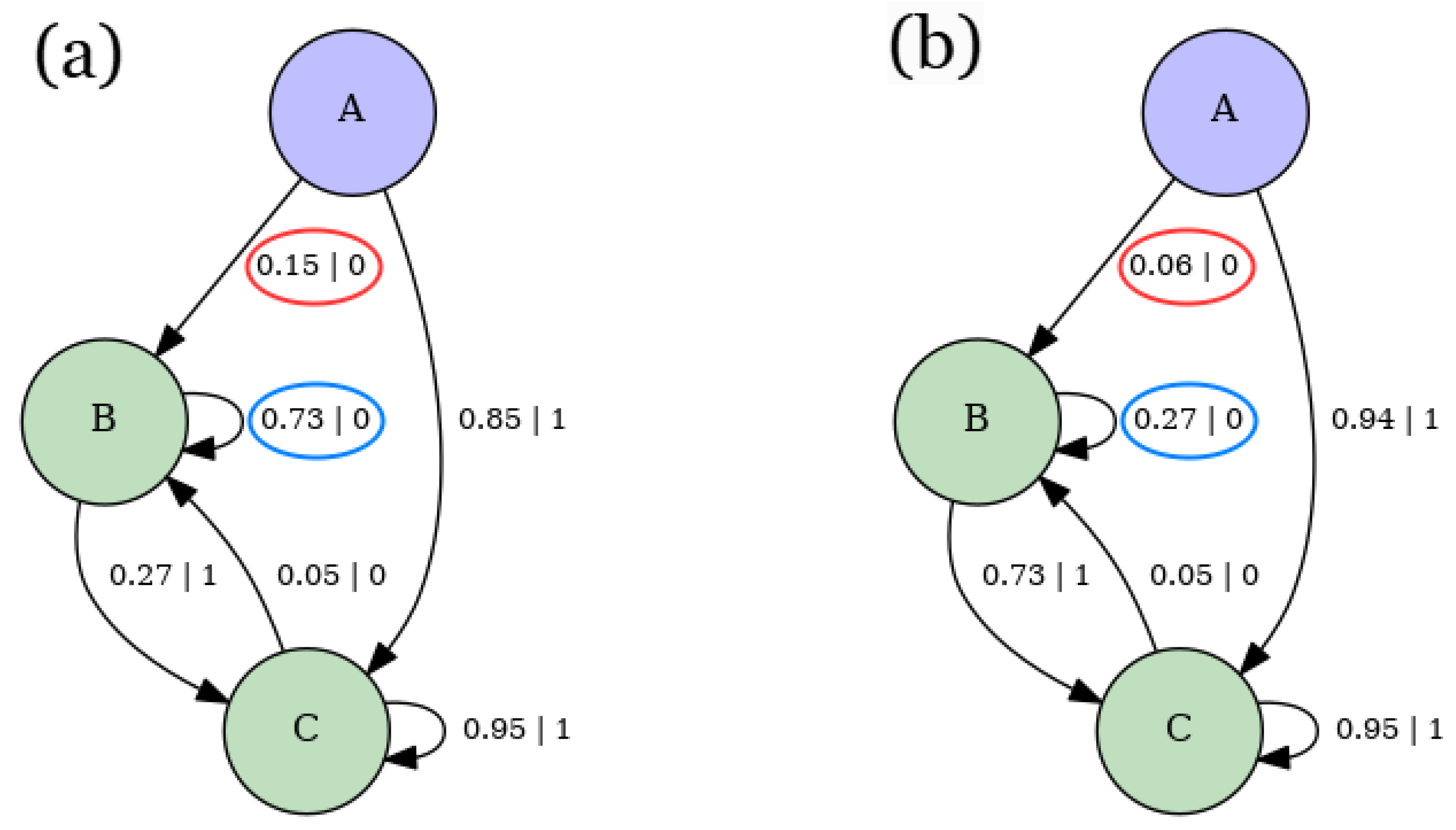

Appendix E. ϵ-Machine of Nearest-Neighbor Ising Model

Appendix F. Joint Probability of Infinite Chain

- Consider a periodic infinite spin chain whose spins can only take two values (up or down) and only interact with their nearest neighbors.

- Define a Hamiltonian for this system in a translation-invariant manner.

- Calculate the system’s partition function.

- Define the Boltzmann probability of a given infinite configuration.

- Define the transfer matrix matrix, with components .

- Express Boltzmann probability weight in terms of transfer matrix components.

- Calculate partition function in the thermodynamic limit .

- Apply definition of matrix multiplication and enforce periodic boundary conditions .

- Apply definition of trace.

- Express joint probability of a given infinite spin chain in terms of principal eigenvalue and transfer matrix components .

Appendix G. Eigenvalue Decomposition of Transfer Matrix

- Express in terms of its eigenvalue decomposition .

-

Use fact that in the thermodynamic limit , . Rename as .Therefore,

- Express transfer matrix components in terms of the principal eigenvalue and the principal eigenvector components and at the thermodynamic limit.

Appendix H. Partition Function of Finite Chain with Fixed Boundary Conditions Embedded on Infinite Chain

- Consider the partition function of a finite chain of length 3 with fixed boundary conditions.

- Express transfer matrix components in terms of principal eigenvalue and principal eigenvector components. For simplicity, we will drop the and , because for the nn Ising model the left and right eigenvectors are the same.

Appendix I. Joint Probability of Finite Chain Embedded on Infinite Chain

- Consider a finite spin chain embedded in an infinite spin chain.

-

The embedding of the finite spin chain implies:

- The thermodynamic limit applies to the finite chain.

- The magnetization is uniform across the bulk and boundaries of the finite chain.

- To ensure uniform magnetization, express in terms of conditional and marginal probabilities to separate the contributions from the bulk and boundaries. For simplicity, we denote as .

- Since and are independent, their probabilities can be factored as:

-

Express as a joint probability using .Thus,

- To recover Eq. (36), consider instead of

Appendix J. Finite-Range Ising Model Hamiltonian for R=1,2 and 3

Appendix K. Three-Body Model Transfer Matrix

References

- S. Aaronson, S. M. Carroll, and L. Ouellette. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1405.6903.

- D. P. Feldman and J. P. Crutchfield, authors’ note: Manuscript completed in 1998 (Santa Fe Institute Working Paper 98-04-026). Entropy 2022, 24, 1282.

- Bak, P. How Nature Works: The Science of Self-organized Criticality; Springer New York: New York, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- J. Rothstein. Science 1951, 114, 171.

- I. Eliazar. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2021, 568, 125662.

- J. M. Yeomans, Statistical Mechanics of Phase Transitions (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1992).

- S. Krinsky and D. Furman. Physical Review B 1975, 11, 2602.

- R. Gheissari, C. R. Gheissari, C. Hongler, and S. C. Park. Communications in Mathematical Physics 2019, 367, 771. [Google Scholar]

- M. Schulz and S. Trimper. Journal of Statistical Physics 1999, 94, 173.

- R. H. Lacombe and R. Simha, The Journal of Chemical Physics 61, 1899 (1974).

- D. P. Landau and K. Binder, in A Guide to Monte Carlo Simulations in Statistical Physics (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2015) 4th ed., pp. 7–46.

- B. M. McCoy and T. T. Wu, Physical Review 176, 631 (1968).

- P. D. Beale, Physical Review Letters 76, 78 (1996).

- J. Köfinger and C. Dellago, New Journal of Physics 12, 093044 (2010).

- M. M. Tsypin and H.W. J. Blote, Physical Review E 62, 73 (2000).

- C. Chatelain and D. Karevski, Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment 2006, P06005 (2006).

- R. K. Pathria and P. D. Beale, Statistical Mechanics, 3rd ed. (Butterworth-Heinemann, 2011).

- B. Derrida, Physical Review Letters 45, 79 (1980).

- M. Tribus, Thermostatics and Thermodynamics: An Introduction to Energy, Information and States of Matter, with Engineering Applications (D. Van Nostrand Company, Inc., Princeton, New Jersey, USA, 1961).

- G. Bateson, Steps to an Ecology of Mind: Collected Essays in Anthropology, Psychiatry, Evolution, and Epistemology (Jason Aronson Inc., Northvale, NJ and London, 1987).

- T. M. Cover and J. A. Thomas, Elements of Information Theory, 2nd ed. (Wiley-Interscience, Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006).

- R. Shaw, The Dripping Faucet as a Model Chaotic System (Aerial Press, Santa Cruz, California, 1984).

- J. P. Crutchfield and N. H. Packard, Physica D 7, 201 (1983).

- P. Grassberger, International Journal of Theoretical Physics 25, 907 (1986).

- K. Lindgren and M. G. Nordhal, Complex Systems 2, 409 (1988).

- J. P. Crutchfield and K. Young, Physical Review Letters 63, 105 (1989).

- J. P. Crutchfield, Physica D 75, 11 (1994).

- J. P. Crutchfield, Nature Physics 8, 17 (2012).

- C. R. Shalizi and J. P. Crutchfield, Journal of Statistical Physics 104, 817 (2001).

- J. E. Hopcroft and J. D. Ullman, Introduction to Automata Theory, Languages, and Computation, 2nd ed. (Addison-Wesley, 2001).

- J. P. Crutchfield and C. R. Shalizi, Physical Review E 59, 275 (1999).

- S. Still, J. P. Crutchfield, and C. J. Ellison, CHAOS 20, 037111 (2010).

- C. C. Streloff and J. P. Crutchfield, Phys. Rev. E 89, 042119 (2014).

- S. E. Marzen and J. P. Crutchfield, Journal of Statistical Physics 163, 1312 (2016).

- A. Rupe, N. Kumar, V. Epifanov, K. Kashinath, O. Pavlyk, F. Schimbach, M. Patwary, S. Maidanov, V. Lee, Prabhat, and J. P. Crutchfield, in 2019 IEEE/ACM Workshop on Machine Learning in High Performance Computing Environments (MLHPC) (2019) pp. 75–87.

- A. Rupe and J. P. Crutchfield. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.05451.

- N. Brodu and J. P. Crutchfield, Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science 32, 023103 (2022).

- A. M. Jurgens and N. Brodu, Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science 35, 033162 (2025).

- D. P. Feldman and J. P. Crutchfield, Physical Review E 67, 051104 (2003).

- V. S. Vijayaraghavan, R. G. James, and J. P. Crutchfield, Santa Fe Institute Working Paper 15-10-042 (2016).

- C. Aghamohammadi, J. R. Mahoney, and J. P. Crutchfield, Scientific Reports 7, 6735 (2017).

- C. Aghamohammadi, J. R. Mahoney, and J. P. Crutchfield, Physics Letters A 381, 1223 (2017).

- P. Chattopadhyay and G. Paul. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2102.09981.

- D. Chu and R. E. Spinney, Interface Focus 8, 20180037 (2018).

- P. Strasberg, J. Cerrillo, G. Schaller, and T. Brandes. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1506.00894.

- D. H. Wolpert and J. Scharnhorst. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.07131.

- L. Li, L. Chang, R. Cleaveland, M. Zhu, and X. Wu. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.13469.

- A. S. Bhatia and A. Kumar. arxiv 2019, arXiv:1901.07992.

- D.-S. Wang. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1912.03767.

- A. Molina and J. Watrous, Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 475, 20180767 (2019).

- N. A. Alves, B. A. Berg, and R. Villanova, Physical Review B 41, 383 (1990).

- Y. Lin, F. Wang, X. Zheng, H. Gao, and L. Zhang, Journal of Computational Physics 237, 224 (2013).

- A. M. Ferrenberg, J. Xu, and D. P. Landau, Physical Review E 97, 043301 (2018).

- D. J. MacKay, Information Theory, Inference, and Learning Algorithms (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2003).

- A. V. Myshlyavtsev, in Studies in Surface Science and Catalysis, Vol. 138, edited by A. Guerrero-Ruiz and I. Rodríguez-Ramos (Elsevier Science B.V., Amsterdam, 2001) pp. 173–190.

- J. C. Flack, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 375, 20160338 (2017).

- C. R. Shalizi and C. Moore, Foundations of Physics 55, 2 (2025).

- A. L. Ny. lectures given at the Semana de Mecânica Estatística, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais and Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul. arXiv 2007, arXiv:0712.1171.

- S. Muir, Nonlinearity 24, 2933 (2011).

- N. Ganikhodjaev, Journal of Mathematical Analysis and Applications 336, 693 (2007).

- D. Lind and B. Marcus, An Introduction to Symbolic Dynamics and Coding, second edition ed. (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2021).

- J. P. Crutchfield and D. P. Feldman, arXiv preprint cond-mat/0102181 (2001), santa Fe Institute Working Paper 01-02-012.

- C. E. Shannon and W. Weaver, The Mathematical Theory of Communication (University of Illinois Press, Champaign-Urbana, 1963).

- D. Feldman, A Brief Introduction to Information Theory, Excess Entropy, and Computational Mechanics, College of the Atlantic, Bar Harbor, ME (1998), revised October 2002.

- C. R. Shalizi, Causal Architecture, Complexity, and Self-Organization in Time Series and Cellular Automata, Ph.d. dissertation, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI (2001), available at Santa Fe Institute: http://www.santafe.edu/~shalizi/thesis.

- S. E. Marzen and J. P. Crutchfield, Entropy 24, 90 (2022).

- K. Young and J. P. Crutchfield, Chaos, Solitons and Fractals 4, 5 (1994).

- K. A. Young, The Grammar and Statistical Mechanics of Complex Physical Systems, Ph.d. dissertation, University of California, Santa Cruz (1991).

- D. C. Dennett, The Journal of Philosophy 88, 27 (1991).

- R. Kikuchi, Physical Review 99, 1666 (1955).

- J. F. Dobson, Journal of Mathematical Physics 10 (1969).

- M. Slotnick, Physical Review 83, 996 (1951).

- C. Zener and R. R. Heikes, Reviews of Modern Physics 25, 191 (1953).

- A. V. Zarubin, F. A. Kassan-Ogly, A. I. Proshkin, and A. E. Shestakov, Journal of Experimental and Theoretical Physics 128, 778 (2019).

- K. A. Mutallib and J. H. Barry, Physical Review E 106, 014149 (2022).

- R. Moessner and S. L. Sondhi, Physical Review B 63, 224401 (2001).

- W. K. Burton, N. Cabrera, and F. C. Frank, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences 243, 299 (1951).

- J. D. Weeks, in Ordering in Strongly Fluctuating Condensed Matter Systems, NATO Advanced Study Institutes Series: Series B, Physics, Vol. 50, edited by T. Riste (Plenum Press, New York, 1980) pp. 293–315.

- V. Privman and N. M. Švrakić, Journal of Statistical Physics 51, 819 (1988).

- D. B. Abraham, Department of Mathematics, University of Newcastle, Newcastle, New South Wales 2308, Australia (1979).

- J. Wang, X. Feng, C. W. Anderson, Y. Xing, and L. Shang, Journal of Hazardous Materials 221, 1 (2012).

- J. D. Aparicio, E. E. Raimondo, J. M. Saez, S. B. Costa-Gutierrez, A. Alvarez, C. S. Benimeli, and M. A. Polti, Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 10, 107141 (2022).

- V. P. Zhdanov, Surface Science 111, 63 (1981).

- P. A. Redhead, Vacuum 12, 203 (1962).

- M. A. Morris, M. Bowker, and D. A. King, in Comprehensive Chemical Kinetics, Vol. 19 (Elsevier, 1984) pp. 1–179.

- V. P. Zhdanov and K. I. Zamaraev, Soviet Physics Uspekhi 29, 755 (1986).

- A. V. Myshlyavtsev, J. L. Sales, G. Zgrablich, and V. P. Zhdanov, Journal of Chemical Physics 91, 7500 (1989).

| 1 | This paper uses two notions of structure. One refers to a system’s general type of arrangement, which we call generic structure. The other captures a more specific type of arrangement—one that exhibits patterns—which we call intrinsic structure. Throughout the paper, the intended notion will be clear from context. |

| 2 | |

| 3 | Without loss of generality |

| 4 | It should be highlighted that for 1D spin lattice models, the conventional time index is taken to be site location index and there is no time dependence. |

| 5 | This principle formalizes the implicit definition of a state commonly used in theoretical computer science when constructing machines. In this context, a state represents the information that must be retained to predict the system’s future behavior (see Appendix A). |

| 6 | To avoid accounting for computation not inherent to our system |

| 7 | In the 21st century, “computation” often evokes laptops, which perform useful computation—that is, computation carried out for some external task. In contrast, we focus on intrinsic computation, the computation a system performs by itself. To analyze this, we use abstract machines [30]—mathematical models that consist of states and transitions and laid the groundwork for theory of computation. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).