Submitted:

17 October 2025

Posted:

17 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Data Preprocessing

2.2.2. Spatiotemporal Collocation

- Temporal matching: FY-3E and HY-2B are both in sun-synchronous orbits with local equator crossing times of 05:30/17:30 and 06:00/18:00, respectively. Their observation time difference is typically within ±30 min. Accordingly, a temporal window of ±30 min was applied, and only collocated orbits within this interval were retained.

- Spatial matching: Taking FY-3E/WindRAD pixels as the reference, the nearest neighbor in HY-2B/SCA was identified using great-circle distance. Pairs with separation less than 25 km (corresponding to the scatterometer footprint) were retained. The great-circle distance was calculated as follows:

- Wind direction normalization: To resolve 360° periodic ambiguity, wind direction differences were normalized to the [−180°, +180°] interval:

2.2.3. Evaluation Metrics

- Wind speed metrics: Mean Bias, Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and Pearson correlation coefficient (R).

- Wind direction metrics: Mean Bias, Standard Deviation (Std), Median Bias, and Median Absolute Bias.

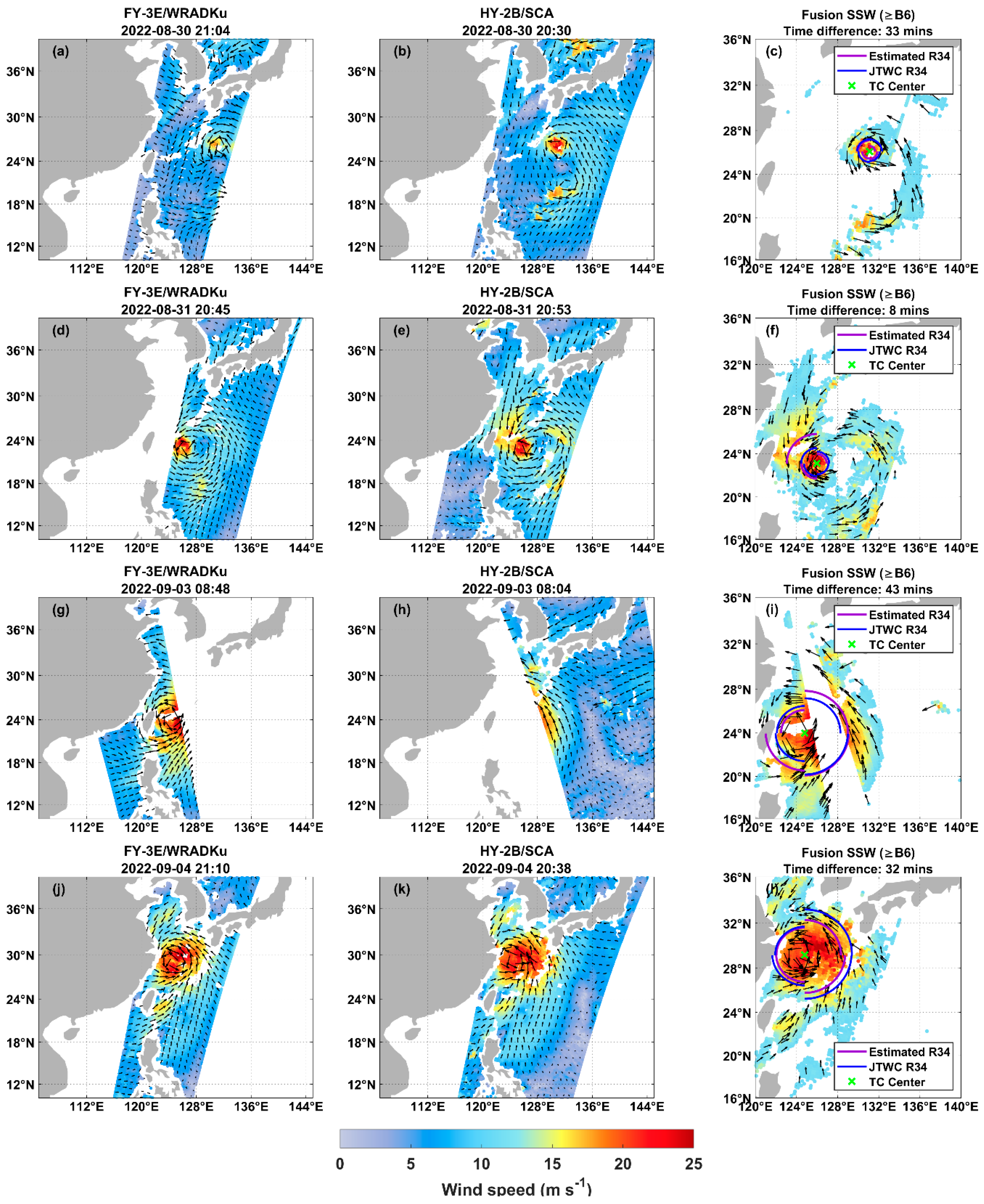

2.2.4. Satellite Data Fusion

- Quality control and preprocessing. Both datasets underwent unified quality control to remove retrieval failures, precipitation, and land contamination.

- Sample selection. Only pixels with wind speed ≥10.8 m/s (Beaufort scale 6 or higher) were retained to focus on TC core structures and reduce low-wind noise.

- Resolution harmonization and fusion. HY-2B/SCA data were resampled to 10 km resolution, consistent with FY-3E/WRADKu. FY-3E was given priority, with HY-2B used to fill uncovered areas. Spatial tolerance was set to 0.06° (~6 km), approximately half of the native FY-3E/WindRADKu footprint. This value balances collocation density and representativeness errors, and is consistent with commonly adopted spatial collocation windows in previous scatterometer validation and intercomparison studies [58,59].

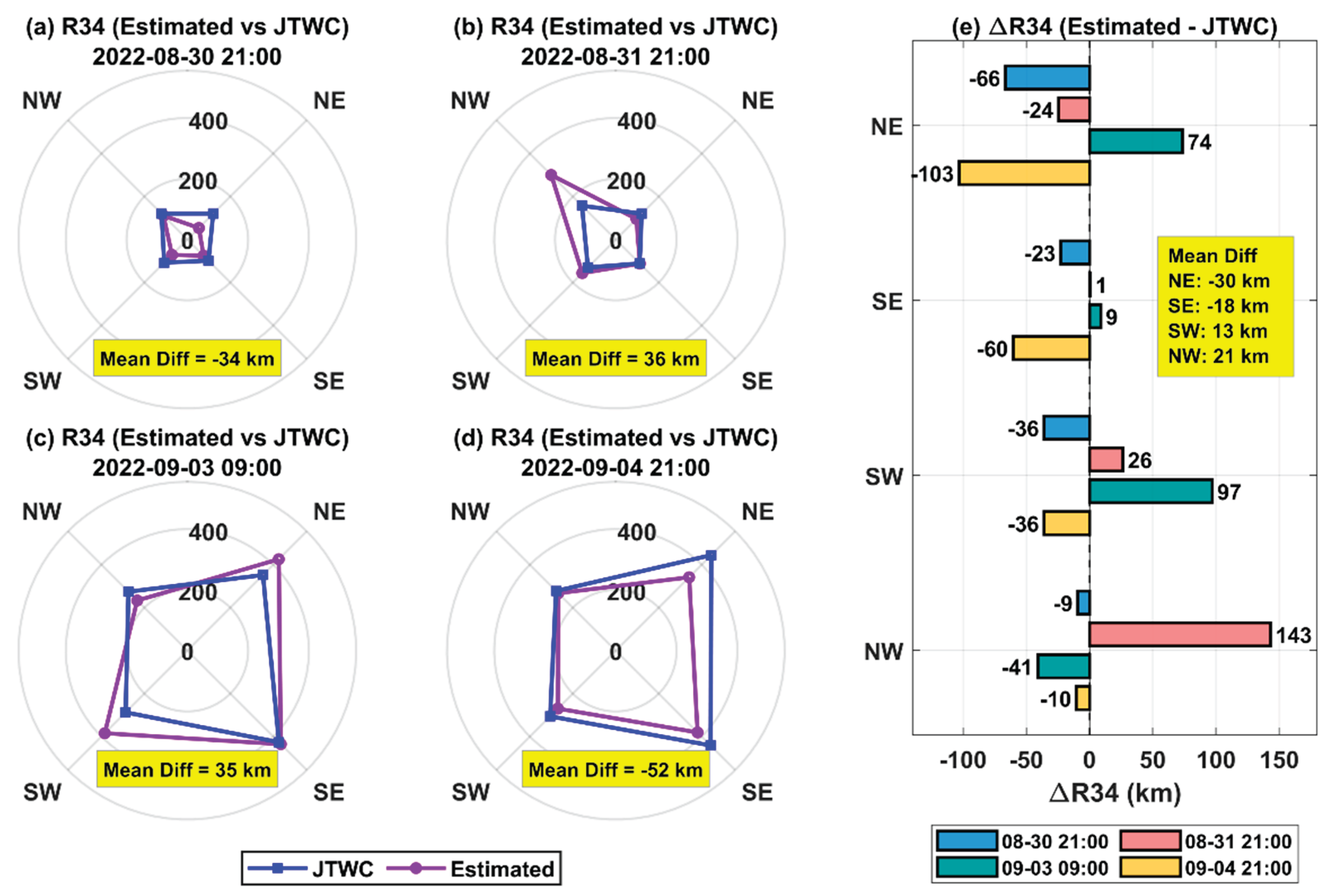

2.2.5. Estimation of Wind Radius (R34) and Comparison with JTWC

3. Results

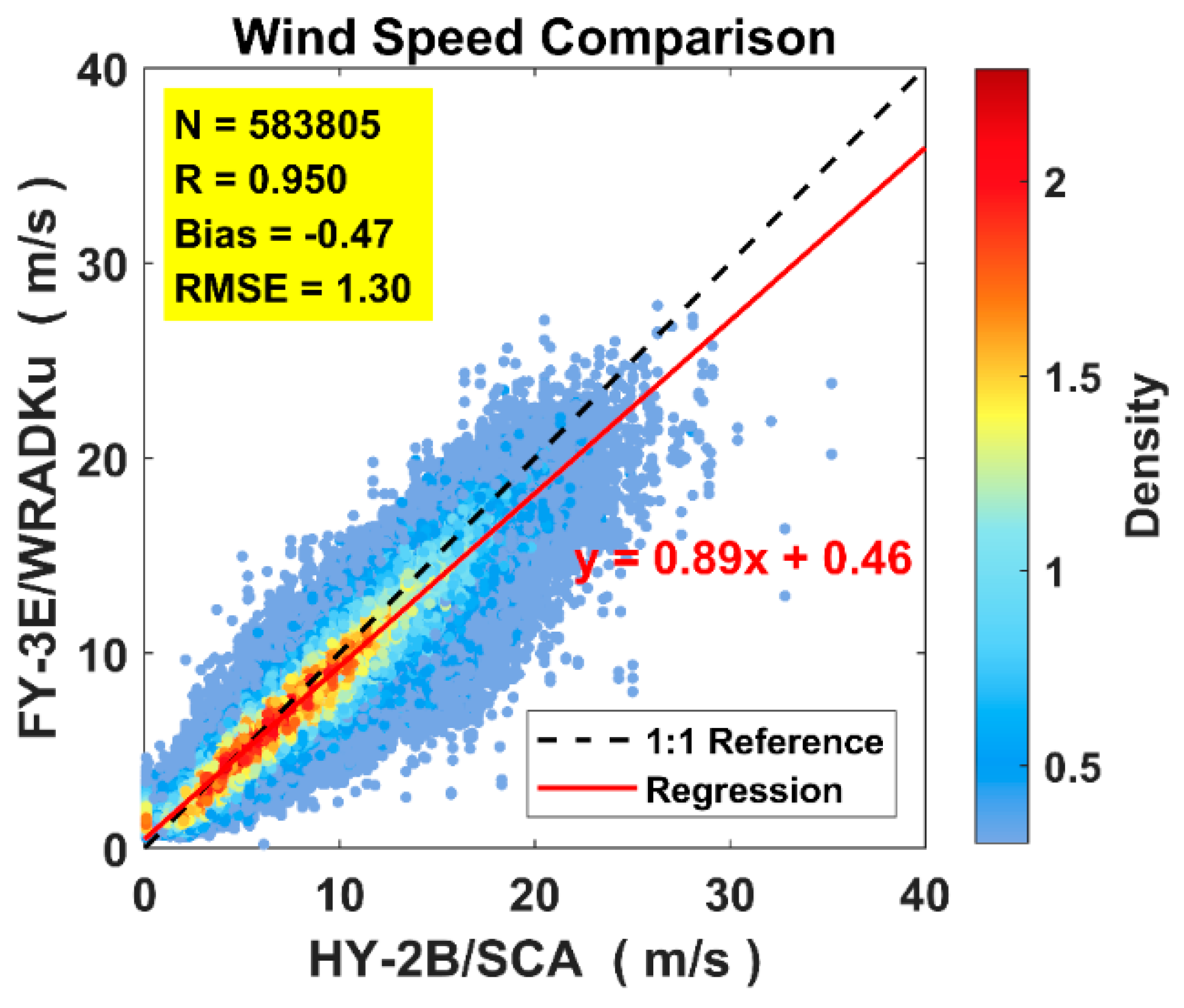

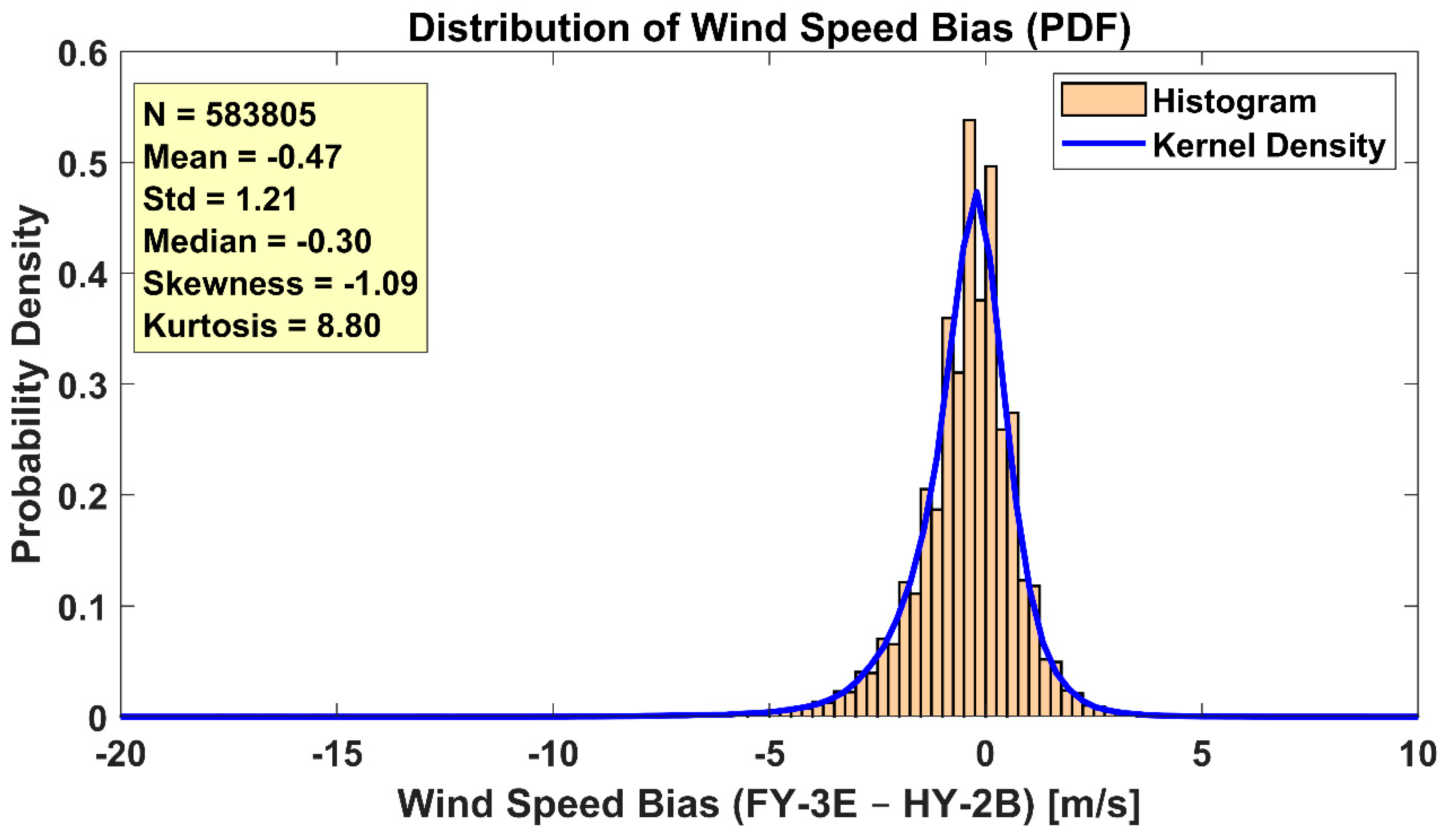

3.1. Wind Speed Comparison

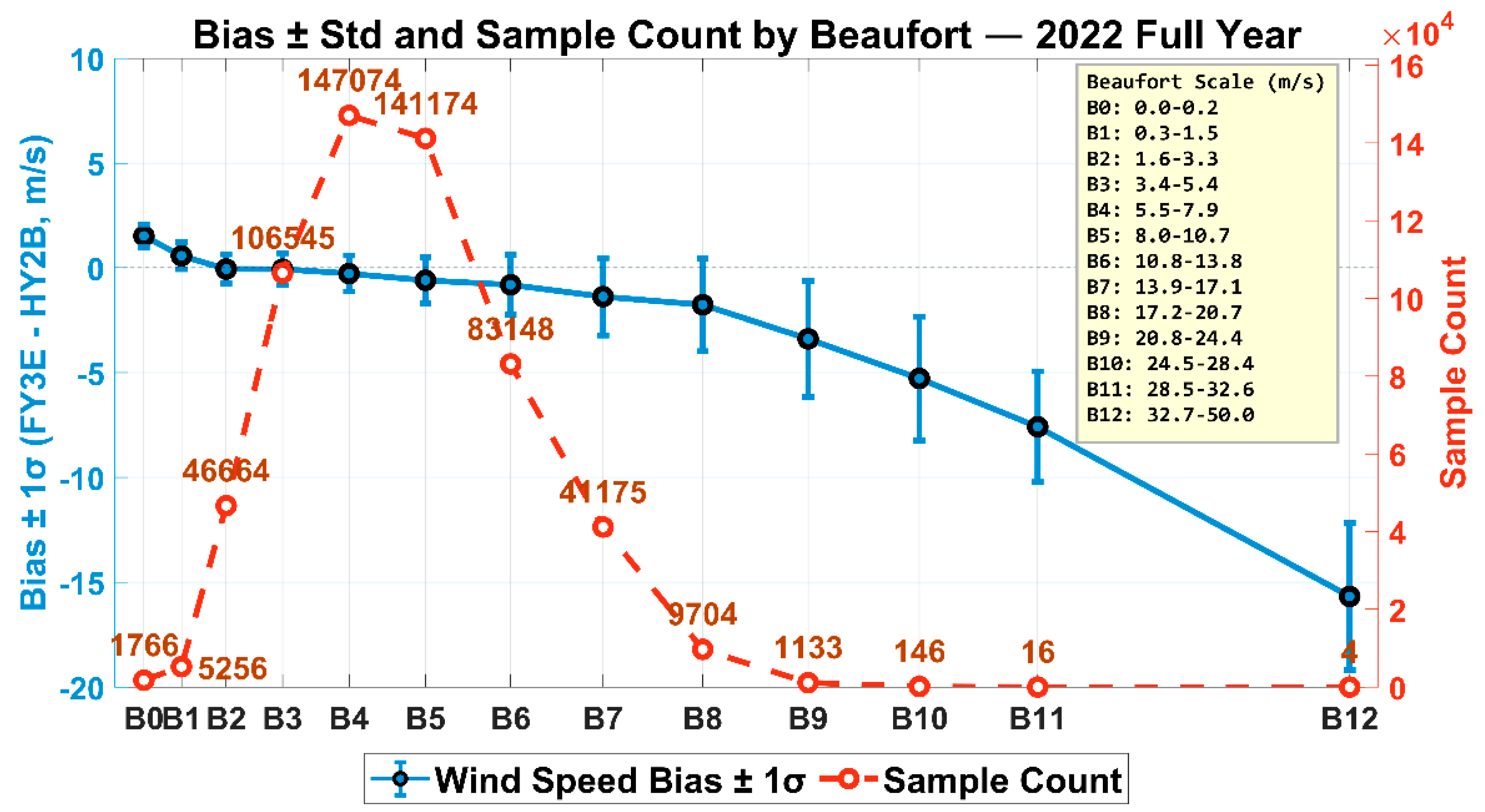

3.1.1. Bias Under Different Wind Speeds

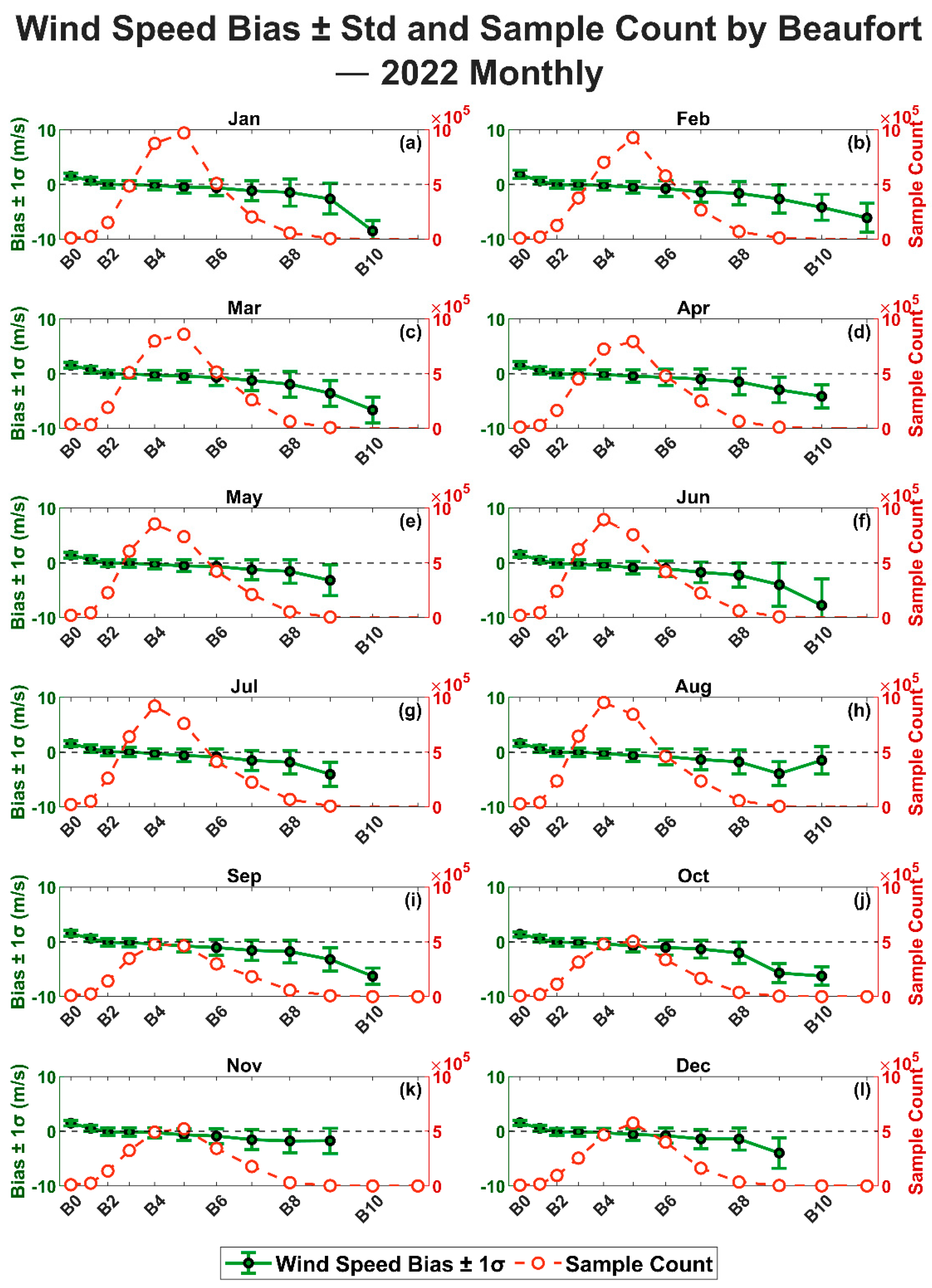

3.1.2. Monthly Bias Variation

3.2. Wind Direction Comparison

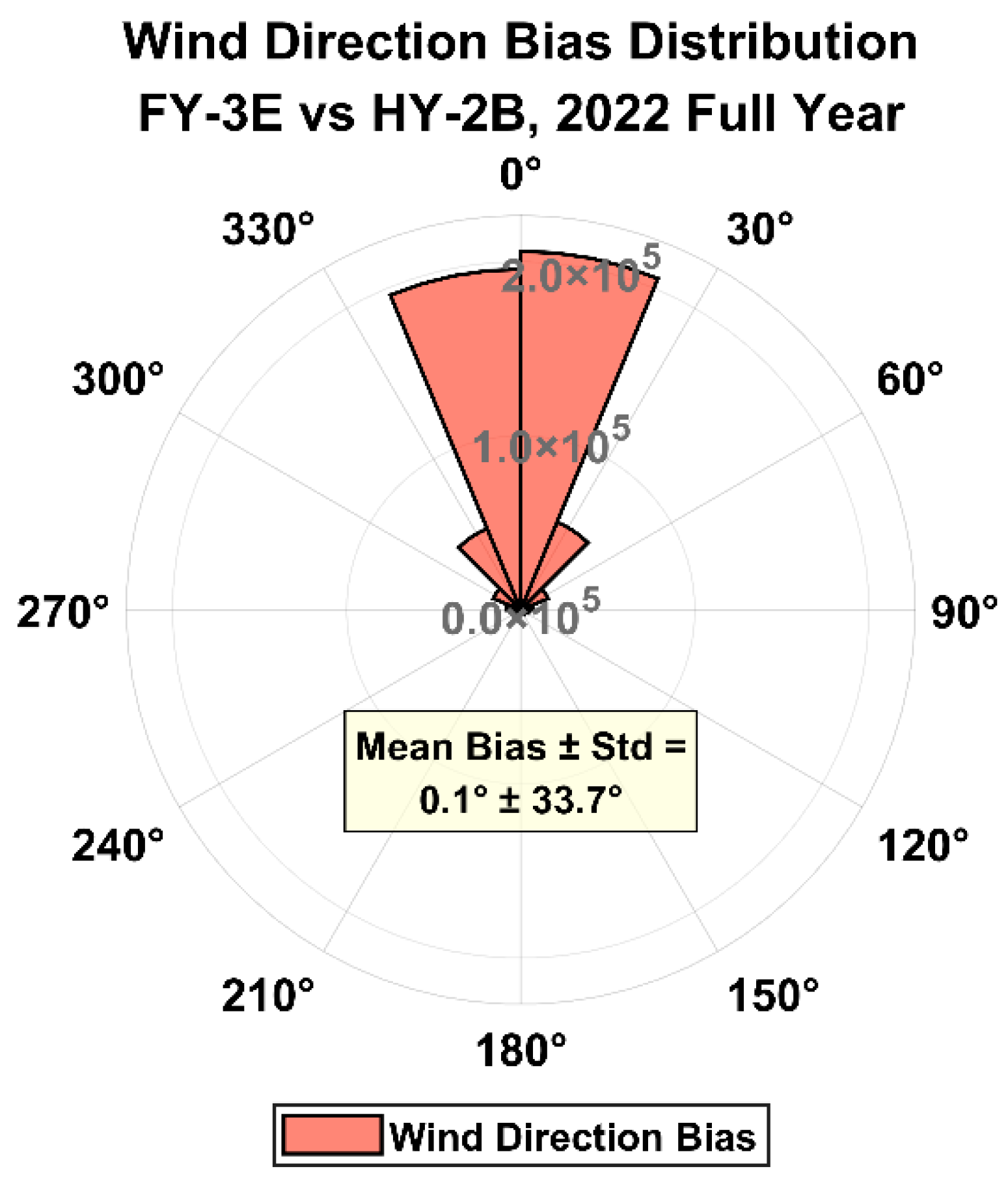

3.2.1. Annual Bias Distribution

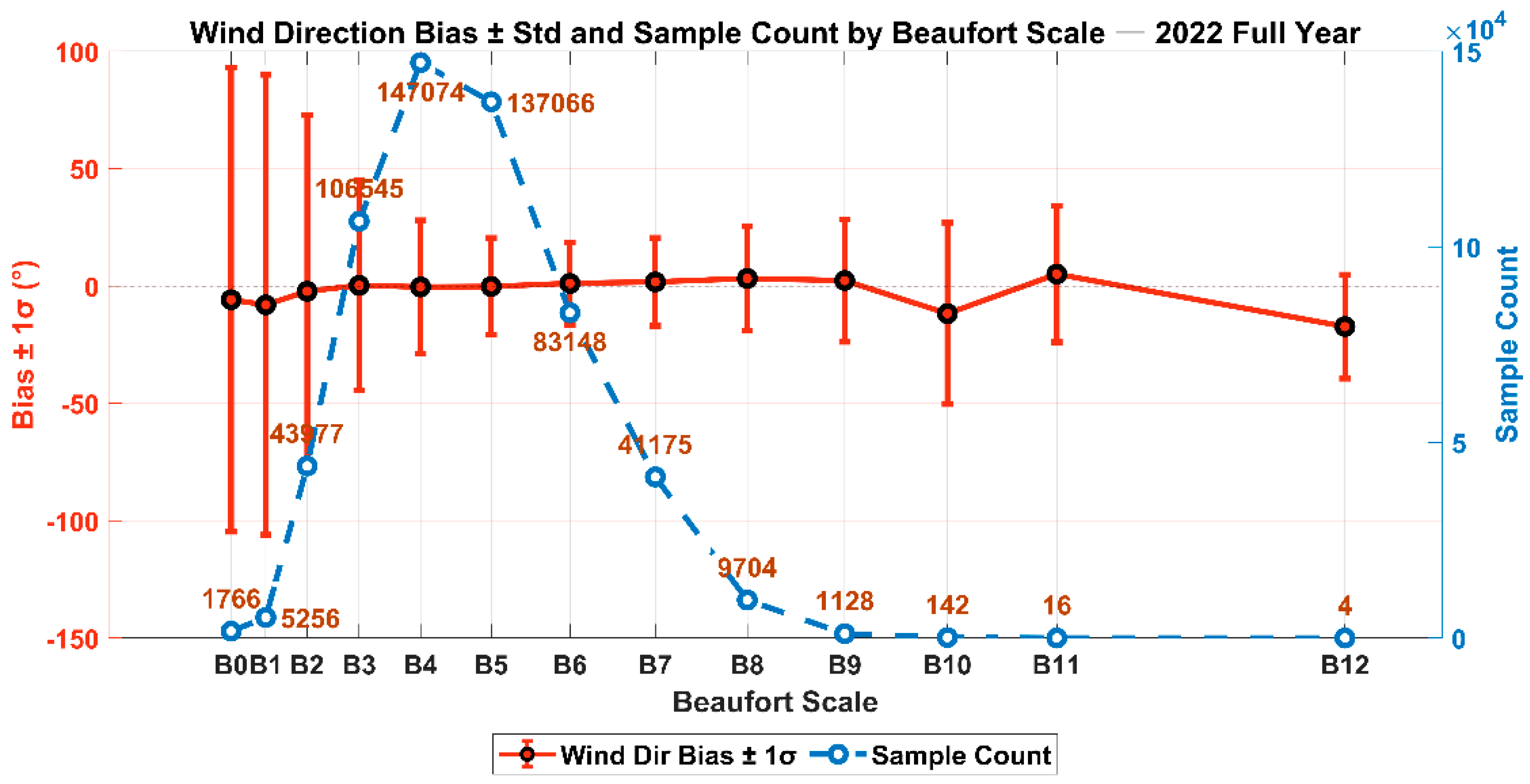

3.2.2. Bias Under Different Wind Speeds

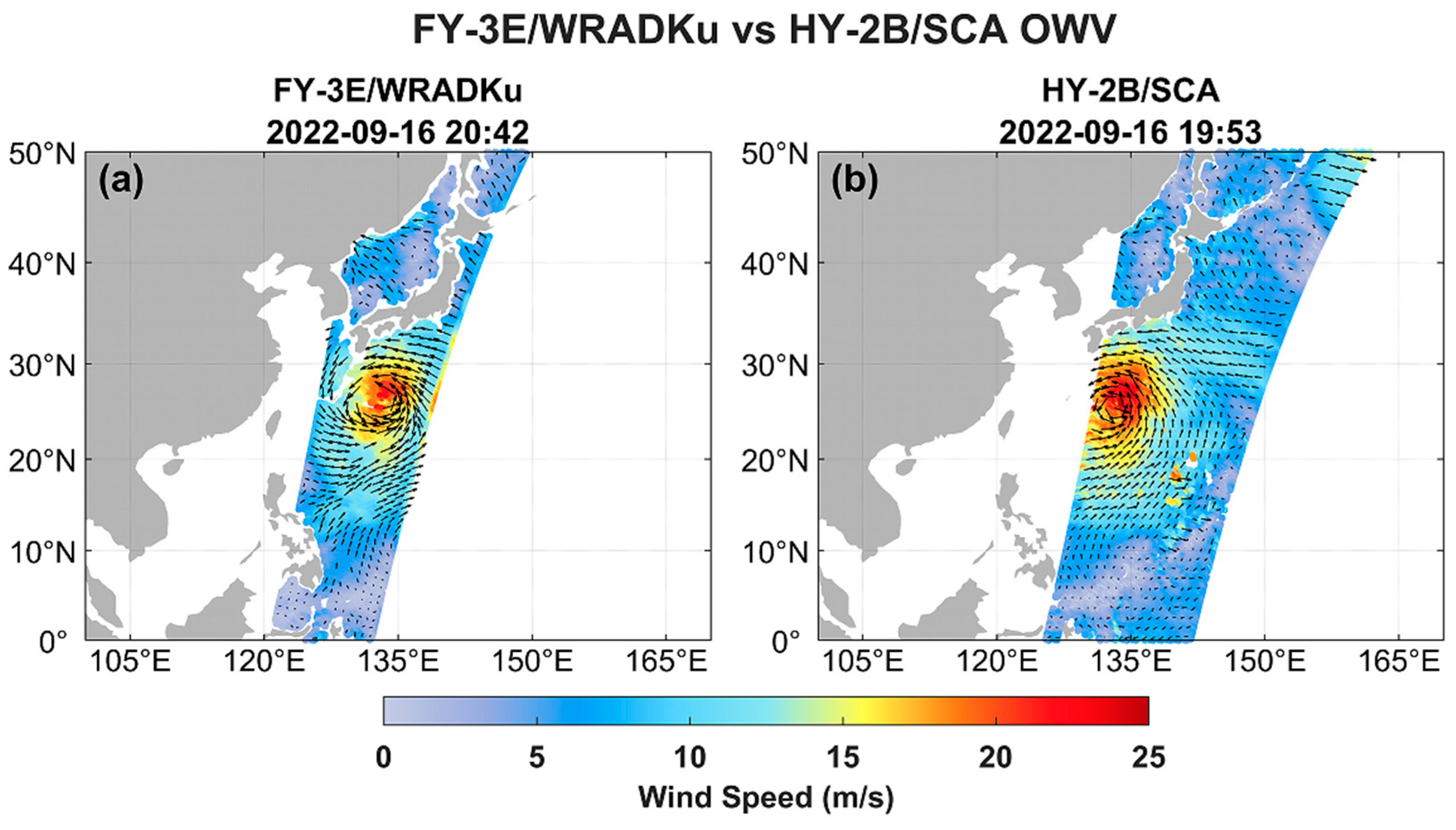

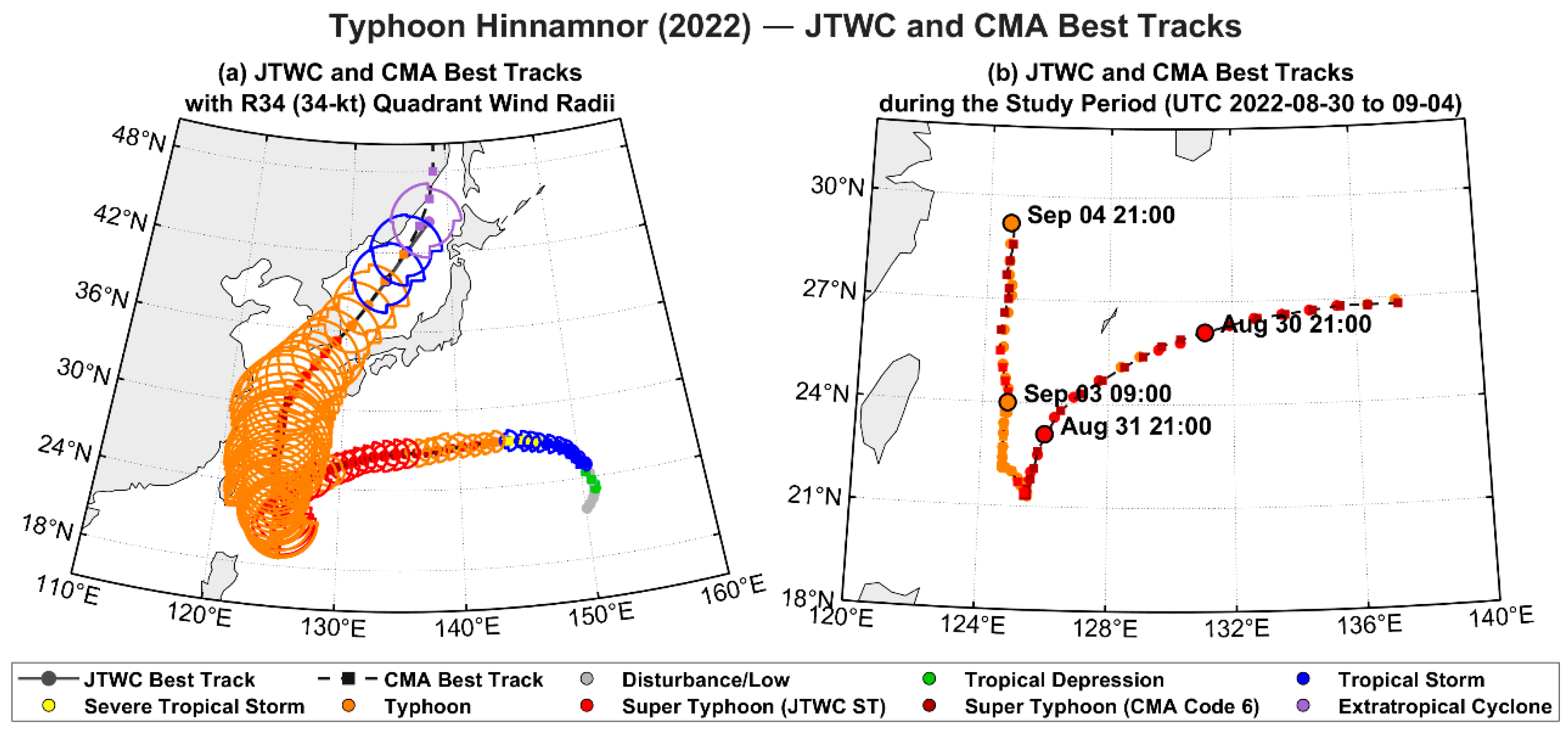

3.3. Application of Wind Field Fusion in TC Monitoring

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Beaufort scale 3–8 (B3–B8) | Beaufort scale force 3 to 8 |

| CMA | China Meteorological Administration |

| ERC | Eyewall replacement cycle |

| FY-3E | FengYun-3E polar-orbiting meteorological satellite |

| GMF | Geophysical model function (σ⁰-to-wind retrieval) |

| HY-2B | HaiYang-2B ocean-dynamics satellite |

| IBTrACS | International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship |

| JTWC | Joint Typhoon Warning Center |

| Ku-band | Microwave band near 12–18 GHz used by the scatterometers |

| R34 / R50 / R64 | Radii of 34/50/64-kt winds (34 kt ≈ 17.5 m s⁻¹) |

| RMSE | Root-mean-square error |

| SCA | Scatterometer onboard HY-2B |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SNR | Signal-to-noise ratio |

| TC | Tropical cyclone |

| WindRAD | Wind Radiometer scatterometer onboard FY-3E |

| WRADKu | FY-3E/WindRAD Ku-band OWV product |

References

- Chelton, D.B.; Schlax, M.G.; Freilich, M.H.; Milliff, R.F. Satellite measurements reveal persistent small-scale features in ocean winds. Science 2004, 303, 978–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyre, J.R.; English, S.J.; Forsythe, M. Assimilation of satellite data in numerical weather prediction. Part I: The early years. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 2020, 146, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.T.; Tang, W.Q.; Polito, P.S. NASA scatterometer provides global ocean-surface wind fields with more structures than numerical weather prediction. Geophysical Research Letters 1998, 25, 761–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, D.; Abdalla, S.; Ardhuin, F.; Bidlot, J.R.; Bourassa, M.; Cotton, D.; Gommenginger, C.; Evers-King, H.; Johnsen, H.; Knaff, J.; et al. Satellite Remote Sensing of Surface Winds, Waves, and Currents: Where are we Now? Surveys in Geophysics 2023, 44, 1357–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desbiolles, F.; Bentamy, A.; Blanke, B.; Roy, C.; Mestas-Nuñez, A.M.; Grodsky, S.A.; Herbette, S.; Cambon, G.; Maes, C. Two decades 1992-2012 of surface wind analyses based on satellite scatterometer observations. Journal of Marine Systems 2017, 168, 38–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlas, R.; Hoffman, R.N.; Leidner, S.M.; Sienkiewicz, J.; Yu, T.W.; Bloom, S.C.; Brin, E.; Ardizzone, J.; Terry, J.; Bungato, D.; et al. The effects of marine winds from scatterometer data on weather analysis and forecasting. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 2001, 82, 1965–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, W.L.; Schroeder, L.C.; Boggs, D.H.; Bracalente, E.M.; Brown, R.A.; Dome, G.J.; Pierson, W.J.; Wentz, F.J. THE SEASAT-A SATELLITE SCATTEROMETER - THE GEOPHYSICAL EVALUATION OF REMOTELY SENSED WIND VECTORS OVER THE OCEAN. Journal of Geophysical Research-Oceans 1982, 87, 3297–3317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracalente, E.M.; Boggs, D.H.; Grantham, W.L.; Sweet, J.L. THE SASS SCATTERING COEFFICIENT SIGMA-DEGREES ALGORITHM. Ieee Journal of Oceanic Engineering 1980, 5, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offiler, D. THE CALIBRATION OF ERS-1 SATELLITE SCATTEROMETER WINDS. Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology 1994, 11, 1002–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderi, F.M.; Freilich, M.H.; Long, D.G. SPACEBORNE RADAR MEASUREMENT OF WIND VELOCITY OVER THE OCEAN - AN OVERVIEW OF THE NSCAT SCATTEROMETER SYSTEM. Proceedings of the Ieee 1991, 79, 850–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freilich, M.H.; Dunbar, R.S. The accuracy of the NSCAT 1 vector winds: Comparisons with National Data Buoy Center buoys. Journal of Geophysical Research-Oceans 1999, 104, 11231–11246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.Y.; Spencer, M.; Wu, C.; Winn, C.; Kellogg, K. SeaWinds on QuikSCAT: Sensor description and mission overview. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Honolulu, Hi, Jul 24-28, 2000; pp. 1021–1023. [Google Scholar]

- Figa-Saldaña, J.; Wilson, J.J.W.; Attema, E.; Gelsthorpe, R.; Drinkwater, M.R.; Stoffelen, A. The advanced scatterometer (ASCAT) on the meteorological operational (MetOp) platform:: A follow on for European wind scatterometers. Canadian Journal of Remote Sensing 2002, 28, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelton, D.B.; Freilich, M.H.; Sienkiewicz, J.M.; Von Ahn, J.M. On the use of QuikSCAT scatterometer measurements of surface winds for marine weather prediction. Monthly Weather Review 2006, 134, 2055–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Ahn, J.M.; Sienkiewicz, J.M.; Chang, P.S. Operational impact of QuikSCAT winds at the NOAA Ocean Prediction Center. Weather and Forecasting 2006, 21, 523–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.; Chen, Z.; Li, J.; Xu, Q.; Yang, H. Characterizing the Effect of Ocean Surface Currents on Advanced Scatterometer (ASCAT) Winds Using Open Ocean Moored Buoy Data. Remote Sensing 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, M.J.; Hennon, C.C.; Knabb, R.D. The Operational Use of QuikSCAT Ocean Surface Vector Winds at the National Hurricane Center. Weather and Forecasting 2009, 24, 621–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentz, F.J.; Smith, D.K. A model function for the ocean-normalized radar cross section at 14 GHz derived from NSCAT observations. Journal of Geophysical Research-Oceans 1999, 104, 11499–11514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornillon, P.; Park, K.A. Warm core ring velocities inferred from NSCAT. Geophysical Research Letters 2001, 28, 575–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.A.; Cornillon, P.; Codiga, D.L. Modification of surface winds near ocean fronts: Effects of Gulf Stream rings on scatterometer (QuikSCAT, NSCAT) wind observations. Journal of Geophysical Research-Oceans 2006, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhang, L.; Ma, C.F.; Peng, H.L.; Zhou, W.; Lu, Y.C.; Wang, Z.X.; Wei, S.Y.; Mu, B.; Zou, J.H. Evaluating the Accuracy of Scatterometer Winds: A Study of Wind Correction Methods Using Buoy Observations. Ieee Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2024, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.X.; Stoffelen, A.; Zhang, B.; He, Y.J.; Lin, W.M.; Li, X.Z. Inconsistencies in scatterometer wind products based on ASCAT and OSCAT-2 collocations. Remote Sensing of Environment 2019, 225, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, D.; Rocha, A.; Gómez-Gesteira, M.; Santos, C.S. Offshore winds and wind energy production estimates derived from ASCAT, OSCAT, numerical weather prediction models and buoys - A comparative study for the Iberian Peninsula Atlantic coast. Renewable Energy 2017, 102, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.; Wang, Z.; Dou, F.; Yuan, M.; Yin, H.; Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; Hu, X.; Zhang, P. Preliminary Performance of the WindRAD Scatterometer Onboard the FY-3E Meteorological Satellite. Ieee Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2024, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Perrie, W.; Zhang, G.S.; Zhang, P.; Chen, L.; Xu, C. Tropical Cyclone Center Estimates Purely From FY-3E WindRAD Measurements in the Dawn-Dusk Orbit. Geophysical Research Letters 2025, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Fang, H.; Li, X.H.; Fan, G.F.; He, Z.H.; Cai, J.Z. Assessment of Spatiotemporal Variations in Wind Field Measurements by the Chinese FengYun-3E Wind Radar Scatterometer. Ieee Access 2023, 11, 128224–128234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Verhoef, A.; Stoffelen, A.; Shang, J.; Dou, F.L. First Results from the WindRAD Scatterometer on Board FY-3E: Data Analysis, Calibration and Wind Retrieval Evaluation. Remote Sensing 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.X.; Jin, A.X.; Jin, A.Z.; Xue, S.Y.; Yao, P.; Dong, G.; Shi, H.Q.; Jin, X.; Liu, S.B.; Lv, A.L.; et al. FY-3E Wind Scatterometer Prelaunch and Commissioning Performance Verification. Ieee Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2023, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.; Wang, Z.X.; Dou, F.L.; Yuan, M.; Yin, H.G.; Liu, L.X.; Wang, Y.T.; Hu, X.Q.; Zhang, P. Preliminary Performance of the WindRAD Scatterometer Onboard the FY-3E Meteorological Satellite. Ieee Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2024, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Mu, B.; Lin, M.S.; Song, Q.T. An Evaluation of the Chinese HY-2B Satellites Microwave Scatterometer Instrument. Ieee Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2021, 59, 4513–4521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Xie, X.; Zhang, J.; Zou, J.; Zhang, Y. Accuracy analysis of the retrieved wind from HY-2B scatterometer. Journal of Tropical Oceanography 2020, 39, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Q.; Lin, W.M.; Portabella, M.; Wang, Z.X. Characterization of Tropical Cyclone Intensity Using the HY-2B Scatterometer Wind Data. Remote Sensing 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, S.; Lin, W.; Wang, Z.; Zou, J. Blending Sea Surface Winds from the HY-2 Satellite Scatterometers Based on a 2D-Var Method. Remote Sensing 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Mu, B.; Shi, H.Q.; Ma, C.F.; Zhou, W.; Zou, J.H.; Lin, M.S. Validation and accuracy analysis of wind products from scatterometer onboard the HY-2B satellite. Acta Oceanologica Sinica 2023, 42, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhu, J.H.; Lin, M.S.; Zhang, Y.G.; Chang, Y.T. Evaluating Chinese HY-2B HSCAT Ocean Wind Products Using Buoys and Other Scatterometers. Ieee Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2020, 17, 923–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Stoffelen, A.; Zou, J.; Lin, W.; Verhoef, A.; Zhang, Y.; He, Y.; Lin, M. Validation of New Sea Surface Wind Products From Scatterometers Onboard the HY-2B and MetOp-C Satellites. Ieee Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2020, 58, 4387–4394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, J.; Wang, J.; Han, G. Evaluation and Calibration of Remotely Sensed High Winds from the HY-2B/C/D Scatterometer in Tropical Cyclones. Remote Sensing 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Lin, W.; Portabella, M.; Wang, Z. Characterization of Tropical Cyclone Intensity Using the HY-2B Scatterometer Wind Data. Remote Sensing 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.G.; Wu, Y.Y.; Zheng, G.; Zhang, D.R.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Li, Y. Tropical Cyclone Center Automatic Determination Model Based on HY-2 and QuikSCAT Wind Vector Products. Ieee Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2019, 57, 709–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffelen, A.; Verspeek, J.A.; Vogelzang, J.; Verhoef, A. The CMOD7 Geophysical Model Function for ASCAT and ERS Wind Retrievals. Ieee Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2017, 10, 2123–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, J.; Fraser, A.D.; Porter-Smith, R. Polar maps of C-band backscatter parameters from the Advanced Scatterometer. Earth System Science Data 2022, 14, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.Q.; Yu, H.; Ying, M.; Zhao, B.K.; Zhang, S.; Lin, L.M.; Bai, L.N.; Wan, R.J. Western North Pacific Tropical Cyclone Database Created by the China Meteorological Administration. Advances in Atmospheric Sciences 2021, 38, 690–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Bai, L.; Zhu, X.; Huang, X.; Jin, R.; Yu, H.; Tang, J. The extraordinarily large vortex structure of Typhoon In-fa (2021), observed by spaceborne microwave radiometer and synthetic aperture radar. Atmospheric Research 2023, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentamy, A.; Grodsky, S.A.; Carton, J.A.; Croize-Fillon, D.; Chapron, B. Matching ASCAT and QuikSCAT winds. Journal of Geophysical Research-Oceans 2012, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardulli, L.; Howell, B.; Jackson, C.R.; Hawkins, J.; Courtney, J.; Stoffelen, A.; Langlade, S.; Fogarty, C.; Mouche, A.; Blackwell, W.; et al. Remote sensing and analysis of tropical cyclones: Current and emerging satellite sensors. Tropical Cyclone Research and Review 2023, 12, 267–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, C.R.; Fukada, E.M.; Knaff, J.A.; Strahl, B.R.; Brennan, M.J.; Marchok, T. Tropical Cyclone Gale Wind Radii Estimates for the Western North Pacific. Weather and Forecasting 2017, 32, 1029–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaff, J.A.; Sampson, C.R.; Kucas, M.E.; Slocum, C.J.; Brennan, M.J.; Meissner, T.; Ricciardulli, L.; Mouche, A.; Reul, N.; Morris, M.; et al. Estimating tropical cyclone surface winds: Current status, emerging technologies, historical evolution, and a look to the future. Tropical Cyclone Research and Review 2021, 10, 125–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.N.; Chan, J.C.L.; Guo, R.; Sun, T.T. Increasing trend in intensity change of tropical cyclones before making landfall in China. Climate Dynamics 2025, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Satellite Meteorological, C. FY-3E WindRAD Ocean Surface Wind Vector Product User Guide (Version 1.2.0); National Satellite Meteorological Center (NSMC): Beijing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- National Satellite Ocean Application, S. HY-2B Satellite Data User Guide; National Satellite Ocean Application Service (NSOAS): Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sergeev, D.; Ermakova, O.; Rusakov, N.; Poplavsky, E.; Gladskikh, D. Verification of C-Band Geophysical Model Function for Wind Speed Retrieval in the Open Ocean and Inland Water Conditions. Geosciences 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Verhoef, A.; Stoffelen, A. WindRAD Scatterometer Quality Control in Rain. Preprints 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Stoffelen, A.; Verhoef, A.; Wang, Z.X.; Shang, J.; Yin, H.G. Higher-order calibration on WindRAD (Wind Radar) scatterometer winds. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques 2023, 16, 4769–4783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.X.; Stoffelen, A.; Zhao, C.F.; Vogelzang, J.; Verhoef, A.; Verspeek, J.; Lin, M.S.; Chen, G. An SST-dependent Ku-band geophysical model function for RapidScat. Journal of Geophysical Research-Oceans 2017, 122, 3461–3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.X.; Zou, J.H.; Zhang, Y.G.; Stoffelen, A.; Lin, W.M.; He, Y.J.; Feng, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Mu, B.; Lin, M.S. Intercalibration of Backscatter Measurements among Ku-Band Scatterometers Onboard the Chinese HY-2 Satellite Constellation. Remote Sensing 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Information, N.N.C.f.E. International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS) Version 4r01: Technical Details; NOAA NCEI: Asheville, NC, 2025-09-25 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, X.; Wei, J.; Huang, L. Evaluation of ASCAT Coastal Wind Product Using Nearshore Buoy Data. Journal of Applied Meteorolgical Science 2014, 25, 445–453. [Google Scholar]

- Vogelzang, J.; Stoffelen, A.; Verhoef, A.; Figa-Saldaña, J. On the quality of high-resolution scatterometer winds. Journal of Geophysical Research-Oceans 2011, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffelen, A. Toward the true near-surface wind speed: Error modeling and calibration using triple collocation. Journal of Geophysical Research-Oceans 1998, 103, 7755–7766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhao, D.; Duan, Y.; Guan, S.; Dong, L.; Xu, H.; Wang, H. Super Typhoon Hinnamnor (2022) with a Record-Breaking Lifespan over the Western North Pacific. Advances in Atmospheric Sciences 2023, 40, 1558–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, W. How Did the Merger With a Tropical Depression Amplify the Rapid Weakening of Super Typhoon Hinnamnor (2022)? Geophysical Research Letters 2024, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center, N.N.H. Glossary of NHC Terms — "Best track". Available online: https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/aboutgloss.shtml (accessed on 2025-09-25).

| Parameter | FY-3E/WindRAD | HY-2B/SCA |

| Orbit type | Sun-synchronous orbit | Sun-synchronous orbit |

| Equator crossing time | 05:30 (descending) / 17:30 (ascending) | 06:00 (descending) / 18:00 (ascending) |

| Orbital period | ~99 min per cycle | ~100 min per cycle |

| Global coverage cycle | Twice daily over global oceans | >90% coverage every 1–2 days |

| Wind measurement mode | Dual-frequency, dual-polarization, conical scanning scatterometer | Single-frequency, dual-polarization, conical scanning scatterometer |

| Operating frequency | C-band (5.3 GHz) + Ku-band (13.256 GHz) | Ku-band (13.256 GHz) |

| Polarization | HH, VV | HH, VV |

| Calibration | External calibration + onboard calibration | Onboard calibration |

| Spatial resolution | ~20–25 km | ~25 km |

| Swath width | ~1250–1300 km | 1350 km (H-pol), 1700 km (V-pol) |

| Observation cycle | Global coverage twice per day | Global coverage every 1–2 days |

| Wind retrieval model | CMOD7 (C-band), NSCAT-6 (Ku-band), CMOD7+NSCAT-6 (dual-frequency) | NSCAT-4 GMF model |

| Wind products | WRADC (C-band), WRADKu (Ku-band), WRADX (dual-frequency) | L2B wind speed and direction (HDF5) |

| Wind definition | 10 m stress-equivalent wind | 10 m stress-equivalent wind |

| Wind speed range | 3–40 m/s | 3–35 m/s |

| Quality control | Multi-bit QC flags (e.g., Bit13–Bit16) | Multi-bit QC flags (rain, land contamination, anomalies, retrieval failure) |

| Wind direction processing | MSS + 2DVAR ambiguity removal | MSS + 2DVAR ambiguity removal |

| Data format | HDF5 | HDF5 |

| Beaufort scale | Wind speed range (m/s) |

| 0 | <0.2 |

| 1 | 0.3–1.5 |

| 2 | 1.6–3.3 |

| 3 | 3.4–5.4 |

| 4 | 5.5–7.9 |

| 5 | 8.0–10.7 |

| 6 | 10.8–13.8 |

| 7 | 13.9–17.1 |

| 8 | 17.2–20.7 |

| 9 | 20.8–24.4 |

| 10 | 24.5–28.4 |

| 11 | 28.5–32.6 |

| 12 | ≥32.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).