Introduction

Case Presentation

A two-month-old male infant was admitted to the emergency department for persistent non-bilious projectile vomiting episodes, which had started one month before. The child was breastfed; episodes usually occurred 20 minutes after feeding and were preceded by abdominal muscle contraction. The patient has experienced wight loss greater than 10% of neonatal weight in the previous month. Bowel function was regular, while the urinary output was reduced. The child’s family history was unremarkable. He was a full-term born male infant, delivered vaginally. The perinatal was average and no physical examinations were performed at birth. On admission, a physical examination revealed sunken eyes, dry mucosa, abnormal skin fold, and a heart rate of 160 bpm, with a standard capillary refill and blood pressure without fever. Abdominal examination was expected, with no palpable masses and normal peristalsis. His weight was 2290g. Blood glucose 109 mg/dL. Urine analysis indicated a specific gravity of 1030.

After admission, the infant presented with some projectile, non-bilious vomiting. An abdominal X-ray proved a marked gastric distension (

Figure 1). An abdominal ultrasound (US) displayed a thickened pylorus with a wall thickness of 5.7 mm and a length of 17.5 mm (

Figure 2). A diagnosis of hypertrophic pyloric stenosis was made.

Due to the small weight and the degree of dehydration, peripheral venous access and a blood analysis could not be obtained. A nasogastric tube was placed for a rescue feeding, starting with a continuous enteral feeding, then with small and frequent meals (expressed breast milk and infant formula 1), eventually offering increased amounts.

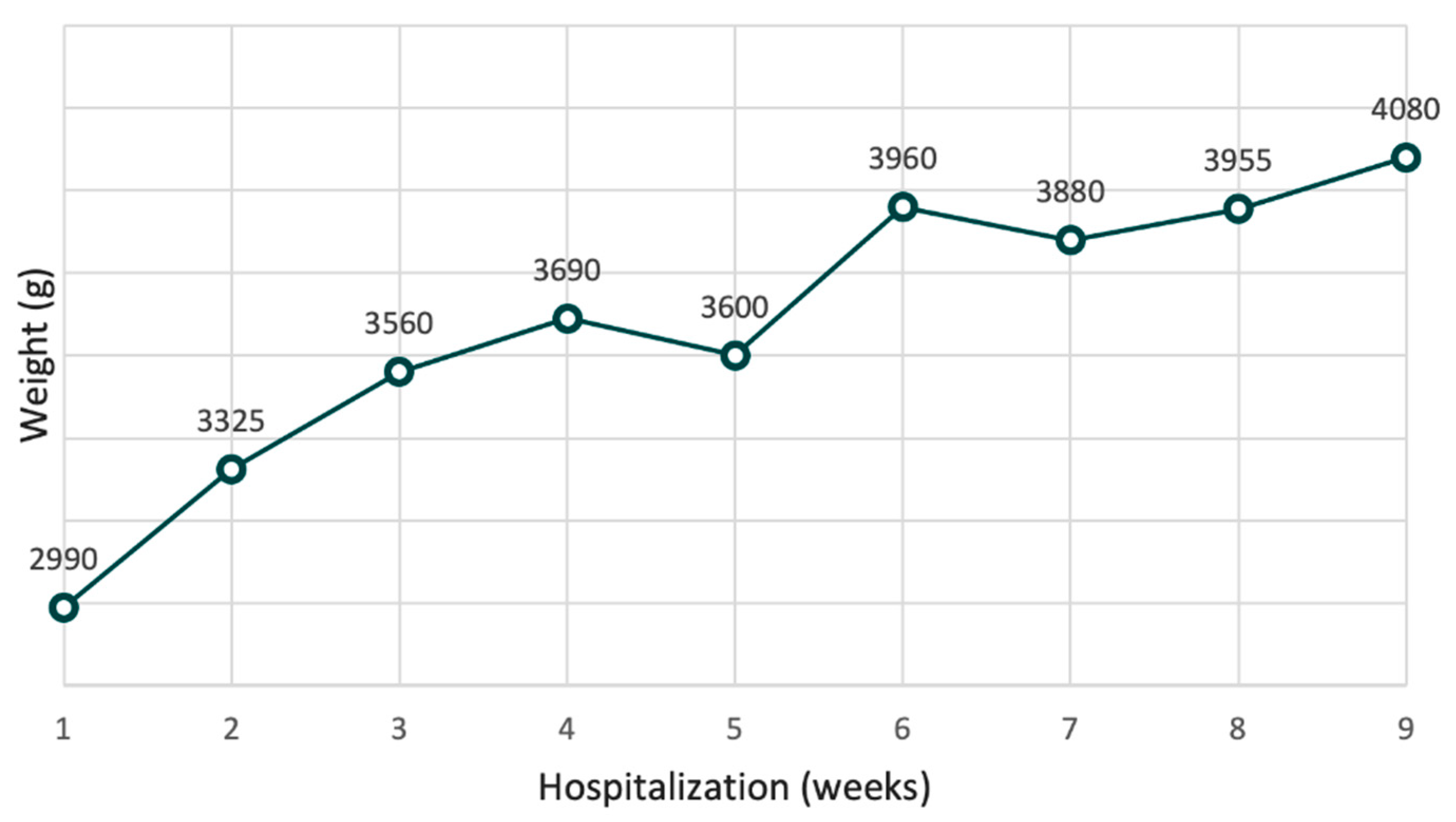

Treatment with oral atropine, at a dosage of 0.1 mg/kg/day, administered four times per day before feeding, was started. Initially, the patient tolerated the meals and the therapy only partially, with some episodes of vomiting; some meals had to be administered several times. Sublingual ondansetron (dose 0.15 mg/kg) was administered as needed. After two weeks, meal tolerance started to improve, with a reduction of vomits and reduction ondansetron needs. The infant’s weight increased, as showned in the

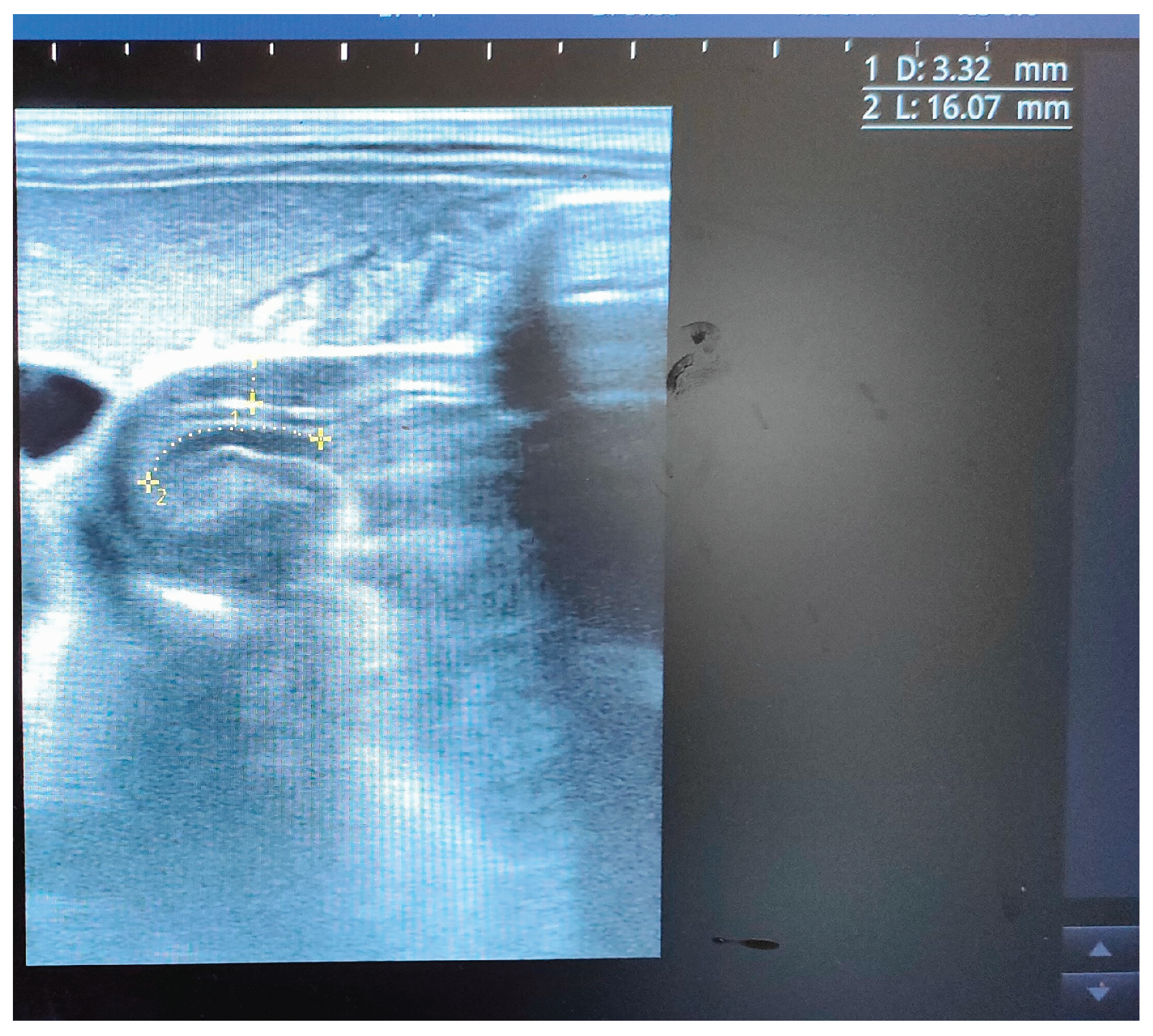

Figure 3. After one month, an abdominal pyloric ultrasound revealed a canal length of 16 mm and muscle thickening reduced to 3 mm (

Figure 4).

Within two months of therapy, the infant gained 1090 grams. The subject achieved a complete oral feeding tolerance until the removal of a nasogastric tube. At four months of age, the infant was discharged. There were no adverse effects during therapy, and his psychomotor development was average for his age.

Discussion

Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (HPS) is a common cause of vomiting in infancy.

Incidence is 2–4 per 1000 live births with geographical variation [

1]

. The typical presentation appears within 4 to 6 weeks of life, with gradual onset of non-bilious projectile vomit which follows every meal, and a characteristic voracious feeding after vomiting. The result is clinically significant dehydration with often electrolyte imbalance (metabolic hypochloremic alkalosis, presenting as a pseudo-Bartter syndrome). Jaundice develops in 2% of patients following a defective hepatic glucuronyl-transferase activity due to starvation [

1]. The diagnosis can be established with clinical history and examination and confirmed with abdominal ultrasound [

1]. The gold standard treatment of HPS is by surgical pyloromyotomy (Ramstedt’s operation). However, this choice involves the presence of trained surgical equipment, which may not be always be available in low-resource settings and carries some surgical risks, including gastric perforation. The existing evidence reports a percentage of good clinical results following conservative management with orale atropine sulfate administration, given alone or as a bridge therapy until surgical equipment is attainable. A large meta-analysis study reported HPS resolution using atropine in 79% of 402 patients [

2]. Atropine is a parasympatholytic, which inhibits peristalsis and muscular spasms that cause muscular hypertrophy of pylorus. It also inhibits meal-induced gastric secretion, with a reduction of the acid environment in the stomach, preventing pyloric sphincter contraction [

3,

4]. Adverse effects, such as tachycardia and oliguria, are documented to be rare and not serious. Suggested dosage is 0.1 mg/kg/day [

5]. However, atropine treatment is not always foolproof, with a rate of failure ranging from 20 to 70% [

6]. For this reason, in our case, due to the severe dehydration and poor general conditions at admission, we empirically added enteral feeding on the first day, as supported by some evidence consistent with the use of a nasogastric or nasoduodenal tube [

6], with frequent and small amounts of milk, along with symptomatic anti-emetic treatment.

The literature does not investigate the add-on value of enteral feeding added to atropine in the setting of HPS or the possible partial effectiveness of anti-emetic drugs.

While no conclusion can be drawn from a single report, this case suggests that in low-resource settings where surgery is not available, a conservative approach should always be attempted, considering enteral feeding and Ondansetron as a possible addition to atropine.

Conclusions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Martina Bradaschia for the English revision of the manuscript

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- El-Gohary, Y.; Abdelhafeez, A.; Paton, E.; Gosain, A.; Murphy, A.J. Pyloric stenosis: an enigma more than a century after the first successful treatment. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2017, 34, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cascini, V.; Chiesa, P.L.; Pierro, A.; Zani, A.; Lauriti, G. Atropine Treatment for Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2017, 28, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi, M.; Yasunaga, H.; Horiguchi, H.; Hashimoto, H.; Matsuda, S. Pyloromyotomy versus i.v. atropine therapy for the treatment of infantile pyloric stenosis: Nationwide hospital discharge database analysis. Pediatr. Int. 2013, 55, 488–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konturek, S.J.; Biernat, J.; Oleksy, J.; Rehfeld, J.F.; Stadil, F. Effect of Atropine on Gastrin and Gastric Acid Response to Peptone Meal. J. Clin. Investig. 1974, 54, 593–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercer, A.E.; Phillips, R. Question 2 * Can a conservative approach to the treatment of hypertrophic pyloric stenosis with atropine be considered a real alternative to surgical pyloromyotomy? Arch. Dis. Child. 2013, 98, 474–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theobald, I.; Rohrschneider, W.K.; Meißner, P.E.; Zieger, B.; Nützenadel, W.; Löffler, W.; Tröger, J. Hypertrophe Pylorusstenose: Sonographisches Monitoringbei konservativer intravenöserTherapie mit Atropinsulfat. Ultraschall der Med. - Eur. J. Ultrasound 2000, 21, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).