1. Introduction

Deforestation remains one of the most significant environmental challenges of the twenty-first century, directly contributing to greenhouse gas emissions, biodiversity loss, and disruptions in ecosystem services. Global assessments indicate that deforestation and forest degradation together account for roughly 11 percent of total anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions, undermining progress toward the Paris Agreement and the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. Between 1990 and 2020, the planet lost approximately 420 million hectares of forest—nearly 10% of global cover—primarily due to agricultural expansion and trade-driven land-use change [

1,

2,

3]. This large-scale loss threatens planetary boundaries, destabilizes hydrological cycles, and reduces the resilience of tropical ecosystems that regulate global carbon and climate systems. A growing body of evidence shows that international commodity demand, particularly from high-income economies, continues to externalize deforestation risks to producing countries [

4,

6,

9]. This persistent decoupling between consumption and environmental responsibility underscores a critical gap in the governance of global supply chains.

Despite decades of international conservation programs and corporate sustainability pledges, deforestation rates remain high, signaling that voluntary approaches alone have been insufficient. Studies show that corporate commitments have yielded only modest progress in reducing forest loss, and trade in forest-risk commodities continues to accelerate land-use change [

4,

6,

9]. These findings have prompted policymakers to strengthen accountability through mandatory mechanisms that link market access to sustainability performance. In recent years, the European Union (EU) has emerged as a global leader in advancing such regulations, seeking to internalize environmental externalities through trade-based instruments that align with the Green Deal and Biodiversity Strategy 2030. While these interventions represent a significant step forward in environmental governance, they also generate new scientific and economic questions concerning their distributive impacts on developing-country exporters and the structural inequalities embedded within global value chains.

The EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR), adopted in 2023, introduces legally binding requirements for traceability and due diligence across high-risk commodities such as rubber, palm oil, soy, and wood [

5,

7]. The regulation aims to ensure that products placed on the EU market are legally produced, deforestation-free, and traceable to their geographic origin. It marks a shift from voluntary corporate responsibility to enforceable obligations under transnational environmental law. However, the scientific understanding of how these stringent sustainability requirements reshape business structures, trade equity, and technological adoption in developing economies remains limited. Scholars have emphasized that while the EUDR strengthens global accountability, it also redistributes compliance responsibilities across the supply chain, requiring producers to provide geolocation data, legality verification, and deforestation-free proof before export. This raises critical concerns over the uneven capacity of firms to meet these standards and the risk that such regulations may inadvertently disadvantage smaller producers with limited digital infrastructure or financial resources.

Thailand provides a critical case for studying these dynamics. As the world’s largest producer of natural rubber—supplying over one-third of global output and a major share of EU imports—its agricultural exports sit at the intersection of environmental policy, trade dependency, and technological transition [

15,

16,

17,

18]. The country’s agro-forestry landscape encompasses over six million hectares of rubber plantations, supporting approximately 1.6 million smallholder farmers who account for about 85 percent of total production. This highly fragmented structure complicates traceability and legality verification, as smallholders often lack secure land tenure, geospatial tools, and access to compliance finance. At the same time, Thailand demonstrates early institutional readiness through the Rubber Authority of Thailand (RAOT), which has launched multiple digital traceability platforms to register farmers and capture geolocation data in alignment with EUDR standards [

30,

33]. This dual reality—strong national commitment but uneven implementation capacity—positions Thailand as an important empirical setting for understanding how environmental trade regulations can simultaneously foster innovation and expose systemic inequities.

Existing literature has largely concentrated on global deforestation trajectories, policy design, and the conceptual framing of the EUDR [

6,

10,

12,

14], leaving significant empirical gaps regarding firm-level adaptation, digital traceability adoption, and the socio-economic consequences for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Previous EU policies such as the EU Timber Regulation (EUTR) and the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) illustrate how well-intentioned environmental measures can impose disproportionate burdens on developing-country exporters when institutional and technological capacities are uneven [

7,

18]. In Thailand, similar asymmetries are expected, as large, vertically integrated enterprises can deploy digital monitoring systems, blockchain traceability, and ESG reporting mechanisms, whereas SMEs remain constrained by limited data systems and fragmented supply chains. This divergence raises important questions about how environmental trade regulations affect not only environmental outcomes but also equity and competitiveness among exporters.

This study addresses these knowledge gaps by combining primary data—business surveys and expert interviews—with secondary trade and policy analysis to assess how Thai firms of varying sizes are responding to the EUDR. Conducted amid the regulation’s transitional phase (2024–2025), the research provides timely insights into how developing-country exporters navigate emerging sustainability standards. Beyond compliance, it explores whether environmental regulation can act as a catalyst for innovation, digital transformation, and inclusivity, or whether it reinforces existing structural inequalities within global value chains. By analyzing firm-level readiness, governance responses, and institutional coordination, the study contributes to a growing body of literature on how deforestation-free trade policies influence business behavior, sustainability transitions, and market equity. The paper further situates Thailand’s experience within the broader context of ASEAN economies, offering lessons for how global environmental regulations can be aligned with national green-growth strategies to ensure that the transition toward deforestation-free trade enhances both sustainability and fairness.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR)

The EUDR, formally adopted on 31 May 2023, establishes a legally binding framework to ensure that specific commodities placed on the EU market are deforestation-free, legally produced, and traceable to their geographic origin [

2]. The regulation extends to seven key commodities—cattle, cocoa, coffee, oil palm, rubber, soya, and wood—and their derivative products such as leather, chocolate, furniture, and paper [

6,

7]. Its implementation marks a significant progression from the EU Timber Regulation (EUTR), which addressed only wood-based goods, toward a broader and more integrated approach linking environmental protection with global trade systems [

3,

4].

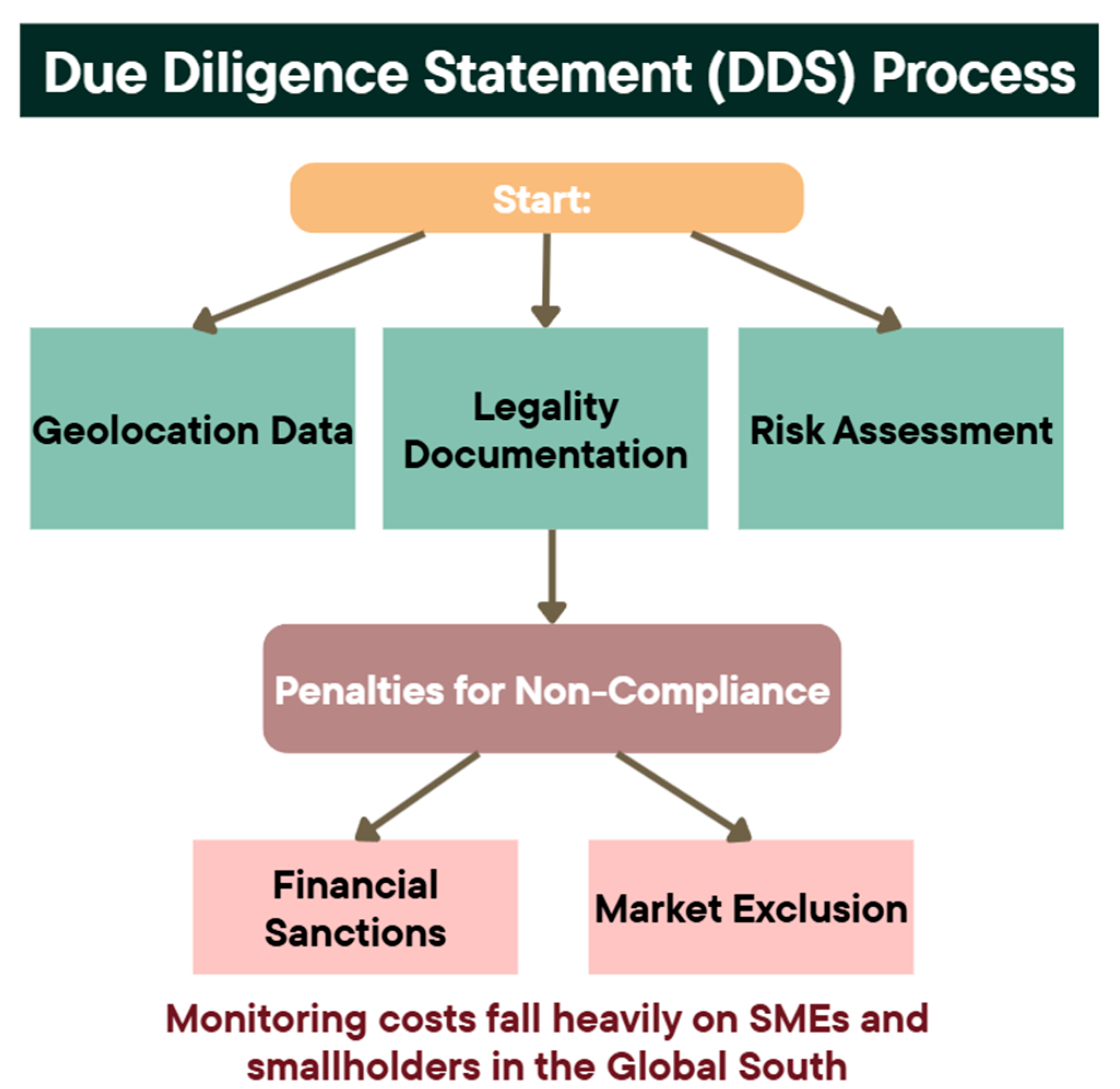

The EUDR requires all operators and traders to submit a Due Diligence Statement (DDS) that includes comprehensive geolocation data, legality verification, and risk assessment documentation for each shipment entering or leaving the EU market [

8,

18]. Non-compliance may result in financial penalties, confiscation of goods, or suspension of market access. The regulation further introduces a country benchmarking system to classify nations as low, standard, or high risk, influencing the level of scrutiny and mitigation required from exporters [

33]. This process of evaluation for the DDS is shown below in

Figure 1, where monitoring costs to SMEs and smallholders in ASEAN countries are highlighted at the end of the process.

While conceptually robust, contributing to the EU’s broader commitment to achieving the Green Deal and Biodiversity Strategy 2030 [

1,

5,

9], the EUDR also introduces practical and distributive challenges. Studies [

10,

12,

19] highlight that developing-country exporters face disproportionate compliance burdens due to limited access to digital traceability technologies, weak land tenure systems, and fragmented supply chains. De Oliveira et al. further emphasize that uniform due diligence requirements can deepen structural inequalities between smallholders and large agribusinesses. Consequently, research into firm-level responses and institutional adaptation, particularly in countries like Thailand, is crucial for identifying pathways toward equitable implementation.

2.2. Thailand’s Affected Sectors Under the EUDR

Thailand’s agricultural export structure makes it particularly vulnerable to the EUDR. As the world’s largest producer and exporter of natural rubber, accounting for approximately 36 percent of global supply and 90 percent of the country’s agricultural exports to the EU, Thailand’s economy is tightly interlinked with commodities directly covered by the regulation [

15,

16]. Rubber, palm oil, and wood products form the core of this exposure, yet each sector presents unique institutional and operational challenges for compliance.

The EUDR mandates that commodities, including rubber, palm oil, soy, cattle, cocoa, coffee, and wood—along with derivative products such as furniture, paper, and leather goods—must be verifiably deforestation-free, legally produced, and traceable to their geographic origin [

6,

7]. This requirement is illustrated in

Figure 2, which highlights the major products within scope for Thailand.

In the rubber sector, Thailand benefits from early institutional readiness through the Rubber Authority of Thailand (RAOT), which has initiated four digital traceability platforms designed to register farmers, verify legality, and capture geolocation data at the plantation level [

30,

33]. Large vertically integrated companies, such as Sri Trang Agro-Industry (STA) and Thai Eastern Group Holdings (TEGH), have already incorporated polygon-based mapping, smallholder training, and blockchain-supported verification into their sustainability programs [

34,

35,

52,

54]. However, smallholders that produce more than 80 percent of Thailand’s natural rubber often lack the financial resources, GPS tools, and legal documentation required for EUDR-aligned reporting [

17,

18,

19].

The palm oil industry, though smaller in EU trade value, faces similar systemic barriers. Large plantations are frequently RSPO-certified and employ satellite monitoring, while independent smallholders remain dependent on intermediaries and informal land-use records, limiting traceability [

11,

23,

27]. The wood and pulp sector, dominated by SMEs and family-owned mills, encounters additional constraints in accessing international certifications such as FSC and PEFC, despite prior experience with the EU Timber Regulation (EUTR) [

9,

12,

26]. Together, these sectors illustrate Thailand’s dual challenge of maintaining EU market access while elevating traceability and legality verification standards across fragmented supply chains.

These findings underscore why Thailand serves as a valuable empirical case for examining the intersection of trade regulation, sustainability, and equity. By studying how firms of different sizes adapt to EUDR requirements, this research aims to identify both the structural constraints and the transformative opportunities emerging within Thailand’s Agri-forestry sectors.

2.3. Data Sources and Design

The data collection and design of this study integrate both qualitative and quantitative approaches to ensure a comprehensive understanding of how the EUDR affects Thai businesses across firm sizes. A mixed-method framework was adopted to capture not only measurable trade and compliance patterns but also the lived experiences and perspectives of stakeholders directly involved in the EUDR’s implementation. This approach allows for triangulation of findings, comparing policy intent, statistical data, and on-the-ground realities, to produce a balanced and evidence-based analysis. The three key data sources and methods used in this research are as follows:

(1) Secondary sources: including EU policy documents, trade statistics, and peer-reviewed literature that establish the regulatory background, economic exposure, and theoretical framework of the study.

(2) Structured survey: conducted as a qualitative, small-scale assessment targeting representatives from companies operating in EUDR-covered sectors. The survey aimed to capture firm-level perspectives on compliance readiness, traceability infrastructure, and cost implications. Given the limited number of participants, the findings are not intended to represent the entire market but to provide nuanced insights into how specific firms within key industries are responding to the regulation. This approach allows for a more contextual understanding of firm behavior, challenges, and adaptation strategies under the evolving EUDR framework.

(3) Semi-structured expert interview with a Counsellor for Environment, Agriculture, and Health at the Delegation of the European Union to Thailand, providing policy-level perspectives on Thailand’s preparedness, EU support mechanisms, and sectoral dynamics influencing implementation.

The structured survey was developed using Google Forms and circulated to producers, processors, and exporters of commodities such as rubber, palm oil, wood, cocoa, coffee, soy, and cattle. Respondents were reached through trade associations and sectoral organizations such as the Member of the Pulp and Paper Industry Club, ensuring coverage across firm sizes and industries. The survey comprised ten questions—both closed and open-ended—designed to capture firm-level variations in compliance capacity, perceived challenges, cost burdens, and opportunities. The criteria of participation were limited to representatives from companies with at least five years of operational experience in EUDR-covered sectors. Respondents were required to hold decision-making or sustainability-related roles, such as chief sustainability officers or compliance managers, to ensure reliability and sectoral representativeness. More details of the survey are shown in the additional information section.

In addition to the analysis of secondary research and business survey, a semi-structured expert interview was conducted via Zoom to provide contextual and policy-level insights into the conceptualization and implementation of the EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR). The interview offered a first-hand policy perspective on the regulation’s design process, Thailand’s comparative readiness, and the operational challenges surrounding risk classification, traceability systems, and firm-level preparedness. The conversation was transcribed and thematically coded to identify patterns related to regulatory interpretation, institutional coordination, and differences in adaptation capacity between large firms and smallholders. While both the survey and interview provide valuable qualitative insights, they are not intended to represent all Thai exporters. Instead, they offer an indicative understanding of how selected firms and policymakers are responding to the evolving regulatory landscape.

2.4. Analytical Framework

Quantitative responses from the business survey were analyzed using descriptive statistics to identify patterns across firm size, while qualitative responses were thematically coded into four key dimensions derived from the literature review: cost burden, compliance readiness, digitalization, and traceability infrastructure. The expert interview was examined through thematic synthesis, integrating policy-level perspectives with firm-level experiences to contextualize the findings. This combined approach allowed the analysis to link structural and institutional dynamics such as Thailand’s low-risk EUDR classification and the influence of government-led traceability platforms to variations in business capacity and readiness across different firm sizes.

2.5. Limitations

This study acknowledges limitations inherent in both primary and secondary data collection. Survey responses are self-reported and may not fully represent all sectors or business sizes, particularly micro-enterprises. Additionally, while Dr. Bucki’s perspective offers invaluable policy insight, the discussion reflects an institutional standpoint rather than firm-level experience. Despite these constraints, combining multiple data sources strengthens the reliability and depth of analysis by bridging regulatory intent with on-the-ground business realities.

3. Literature Review

The EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR), which came into effect on 29 June 2023, represents a central pillar of the EU’s Green Deal and biodiversity strategy. Its primary goal is to ensure that commodities entering the EU are deforestation-free, legally produced, and traceable to their exact origin [

2]. This is operationalized through a mandatory due diligence system (DDS), which requires companies to collect geolocation data of production sites, legal documentation, and environmental risk assessments before placing commodities on the EU market. Non-compliance may lead to fines, seizure of goods, or suspension of market access [

2]. While all firms face equal due diligence obligations, the regulation provides staggered deadlines: large and medium-sized firms must comply by December 2025, whereas small and micro-enterprises have until June 2026 [

5]. Despite this grace period, structural inequalities persist, with small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) facing significant challenges due to their limited resources and digital infrastructure [

8,

10].

The global context for this regulation is shaped by growing concern over the EU’s disproportionate role in tropical deforestation, accounting for 16% of global deforestation linked to international trade [

2]. Scientific studies highlight that commodities such as rubber, palm oil, and wood contribute most to land-use change and biodiversity loss in Southeast Asia [

13,

14]. New research further reveals that deforestation risks are often hidden in global supply chains, requiring satellite monitoring and traceability systems to identify undocumented forest loss [

16]. These findings underscore why the EUDR emphasizes geospatial data and advanced monitoring technologies. However, the ability to operationalize such systems is unevenly distributed across business sizes and countries, creating asymmetries in compliance readiness.

The literature on trade-environment regulations also provides insights into potential impacts. Previous EU policies, such as REACH and the EU Timber Regulation (EUTR), raised entry barriers for exporters in developing countries, with SMEs disproportionately affected by high compliance costs and documentation requirements [

6,

7,

12]. Similarly, the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) introduces carbon tariffs on energy-intensive goods, requiring exporters to monitor and report emissions data. Scholars argue that such mechanisms, while environmentally ambitious, risk reinforcing trade inequalities unless accompanied by capacity-building for developing economies [

7,

18]. In this way, the EUDR continues a broader pattern of regulatory expansion that intertwines environmental governance with market access.

Thailand’s exposure to the EUDR is particularly significant given its reliance on exports of rubber, palm oil, and wood. Thailand is the world’s largest producer of natural rubber, contributing 36% of global supply [

8]. Yet, the supply chain is highly fragmented, with smallholders dominating production, informal transactions, and weak record-keeping. This fragmentation poses substantial barriers to implementing the EUDR’s traceability requirements, which demand plot-level geolocation data [

16,

17]. Palm oil presents a mixed picture: while some large plantations are RSPO-certified and use satellite monitoring, smallholders lack access to such systems, leaving them vulnerable to exclusion [

11,

18]. The wood sector, composed largely of SMEs and family-owned workshops, struggles with limited international certifications like FSC, despite having prior exposure to the EUTR [

9]. Soy, cocoa, and coffee exports remain minor in volume but face similar traceability challenges, especially as smallholders predominate in production [

19].

Recent research highlights that these regulatory burdens fall most heavily on upstream actors, especially SMEs. As Gallemore [

19] demonstrates in the context of coffee supply chains, smallholders face steep costs for compliance technologies such as GPS, making them highly vulnerable to exclusion from EU markets. De Oliveira et al. (2024) similarly argue that high non-compliance rates among smallholder’s risk reinforcing global supply chain inequalities [

18]. By contrast, larger firms are better equipped to integrate digital monitoring systems, hire compliance staff, and absorb the costs of certification. These asymmetries indicate that while the EUDR sets out uniform requirements, the reality of compliance will be stratified by firm size and structural capacity.

Table 1 indicates that the unequal burdens are seen across firm sizes. The Strengths quadrant highlights the regulation’s environmental leadership role and the potential for large firms to leverage compliance into reputational gains. The Weaknesses quadrant illustrates the structural barriers faced by Thai exporters—particularly SMEs—including high compliance costs, fragmented supply chains, and limited technical capacity.

The Opportunities quadrant points to the long-term benefits of EUDR compliance, such as fostering technological innovation, promoting systemic reforms in supply chain transparency, and positioning early adopters for competitive advantages in sustainability-driven markets. Conversely, the Threats quadrant underscores the risks of market exclusion for SMEs, the perception of EUDR as a form of green protectionism, and the imbalance of power within supply chains where smaller producers bear disproportionate costs.

Overall, the table demonstrates the dual nature of the EUDR: while it has the potential to transform global trade towards sustainability, it risks reinforcing trade inequalities unless targeted support mechanisms are implemented for small and medium-sized enterprises.

To conclude, the existing literature points to a dual dynamic: on one hand, the EUDR has the potential to catalyze systemic reforms in supply chain transparency and environmental governance; on the other, it risks entrenching inequalities between large firms and SMEs, as well as between developed and developing economies. This gap between regulatory ambition and structural capacity is particularly evident in Thailand, where fragmented supply chains, limited access to technology, and uneven certification systems challenge the country’s ability to maintain EU market access under the EUDR [

29,

30,

31].

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Firm-Level Readiness and Perceptions of EUDR Compliance

To complement secondary data and policy analysis, a targeted qualitative survey was conducted among Thai businesses directly involved in commodities regulated under the European Union Deforestation Regulation (EUDR). Although the sample size was limited, the respondents—representing both large and medium-sized firms—provided valuable insights into how businesses perceive, prepare for, and experience the compliance process. The findings reveal significant contrasts in capacity, digital readiness, and views on the fairness and feasibility of the regulation.

The first respondent, representing a large enterprise in the rubber sector, reported early and proactive preparation for EUDR compliance. As part of the Rubber Authority of Thailand (RAOT) network, the firm began developing a national database in 2023 to register rubber farmers and validate geolocation data in line with EUDR requirements. The respondent highlighted extensive collaboration with multiple stakeholders and the adoption of GIS and blockchain-based traceability through the Thai Rubber Trade system, supported by an integrated data-management platform. This level of digitalization demonstrates how large, institutionally supported firms have leveraged government-backed infrastructure to align with European due-diligence standards. The respondent viewed the EUDR as an opportunity rather than a constraint, citing potential gains from premium market pricing and sustained EU market access. Furthermore, the participant perceived the regulation as “fair,” given the government investment in providing free compliance systems for smallholders.

In contrast, the second respondent, a medium-sized enterprise in the pulp and paper sector, reflected a more cautious and resource-constrained stance. While aware of EUDR requirements, the firm was still preparing its Due Diligence Statement (DDS) for EU clients. Government assistance was identified as the main source of technical support, and digital record-keeping tools were in use, though with limited integration across the broader supply chain. The respondent identified supply-chain complexity as the principal barrier to achieving full traceability and estimated that compliance would increase operational costs by approximately 5–10%. Although the firm recognized potential benefits from access to environmentally conscious EU buyers, it expressed uncertainty about long-term competitiveness under stricter trade conditions.

Comparison between the two cases illustrates a clear asymmetry in readiness and perception across firm sizes. Large enterprises—especially those connected to government initiatives such as RAOT—demonstrate higher awareness, stronger digital infrastructure, and the capacity to operationalize EUDR-aligned systems. Medium-sized firms, while motivated to comply, face financial, technical, and logistical constraints that hinder rapid adaptation. Their reliance on external support highlights persistent structural barriers for mid-tier exporters lacking economies of scale or advanced technology.

These results reinforce the study’s central finding that the EUDR’s uniform compliance framework, although environmentally justified, imposes unequal burdens across firm sizes. Large firms are capable of converting compliance into a strategic advantage, while smaller actors face rising costs and risks of marginalization. This imbalance echoes concerns raised in earlier studies about “green protectionism,” where sustainability regulations, despite positive environmental intent, may inadvertently exclude smaller exporters in developing economies from global markets [

45,

46]

Although the small sample size limits generalization, the qualitative evidence provides critical insight into Thailand’s differentiated compliance landscape. The findings underscore the need for targeted capacity-building programs, financial incentives, and technology transfer mechanisms—particularly for SMEs—to ensure that sustainability governance under the EUDR fosters inclusive rather than exclusionary trade participation.

4.2. Policy-Level Perspectives on Thailand’s EUDR Readiness

Primary insights from an expert interview with a representative of the Delegation of the European Union to Thailand provide a nuanced understanding of how Thai businesses are adapting to the European Union Deforestation Regulation (EUDR). The interview offered first-hand policy perspectives on how the regulation’s intent translates into implementation at the national level, particularly within Thailand’s agricultural export sectors.

Thailand is recognized as one of the most advanced cases of EUDR preparedness in Southeast Asia, especially in the rubber industry, which accounts for roughly 90 percent of Thailand’s agricultural exports to the EU. The Rubber Authority of Thailand (RAOT) and its partner agencies have proactively developed four digital traceability platforms designed to record plantation-level geolocation data and legality documentation. These platforms are expected to be fully operational by mid-2026 and have already begun facilitating data exchange with European importers. This early digital investment has improved market confidence, with measurable increases in EU-bound rubber exports as buyers recognize Thailand’s comparatively “deforestation-free” status.

However, this preparedness remains uneven across firm sizes. Large exporters and multinational agribusinesses often vertically integrated—benefit from established ESG frameworks, digital mapping systems, and access to compliance specialists. In contrast, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and smallholders continue to face significant barriers, including fragmented land-tenure systems (with over 24 types of land titles managed by multiple agencies), limited access to GPS technology, and financial constraints that restrict investment in monitoring systems. While traceability is technically achievable, legality verification remains far more complex and administratively burdensome for small producers where as observed in Ethiopia’s coffee sector, where procedural compliance rather than production compliance was identified as the main challenge [

50].

The EU’s risk-classification mechanism further shapes these dynamics. Thailand currently holds a low-risk designation, meaning exporters are only required to demonstrate geolocation and legality rather than complete risk-mitigation assessments applicable to medium- or high-risk countries [

2]. Although this classification provides temporary relief, it could change with the release of new FAO Forest Resource Assessment data [

51]. A potential reclassification would add compliance layers that could disproportionately affect SMEs, increasing the risk of exclusion from EU supply chains.

Importantly, the insights highlight that EUDR compliance extends beyond regulation to strategic positioning. The digital traceability platforms developed for EUDR purposes can serve broader functions, such as verifying haze-free or child-labor-free production, turning compliance infrastructure into a competitive advantage. As the expert observed, “the EUDR is not merely a compliance exercise—it is a shift toward building digital trust in supply chains. Those who adapt early will not just meet the regulation; they will define the new standards for sustainable trade.” This perspective is supported by recent corporate disclosures: Sri Trang Agro-Industry (2024) introduced the Sri Trang Friends and Friends Station applications to document farmer transactions digitally, while Thai Eastern Group Holdings (2024) reported polygon-based geolocation mapping, supplier training for 44,607 farmers, and 89.8 percent deforestation-free raw-material verification—demonstrating how digitalization enhances competitiveness and market confidence.

Nonetheless, policy uncertainty— including recent EU proposals to postpone enforcement by one year—poses a risk to early adopters. Institutions and firms that have already invested in compliance systems and personnel may experience delayed returns, reducing incentives for sustained engagement. This uncertainty echoes the concerns expressed by SMEs in the survey and parallels findings from earlier analyses of trade-environment regulations, which show that inconsistent policy timelines can weaken business motivation to invest in long-term sustainability transitions [

46].

Overall, the interview findings reaffirm that firm size remains a critical determinant of EUDR adaptability. Large firms are well-positioned to absorb compliance costs, implement satellite-based verification, and maintain EU market access, while SMEs risk marginalization unless provided with targeted support, funding for digital infrastructure, and simplified legality frameworks. This pattern mirrors broader evidence from global supply-chain studies, which emphasize that environmental trade regulations can simultaneously drive innovation and deepen structural inequality if capacity gaps remain unaddressed [

48,

49]

4.3. Case Studies of EUDR Implementation in the Thai Rubber Sector

According to the literature review, large agribusinesses in Thailand have begun translating the principles of the EUDR into practice through digital traceability and integrated sustainability systems. Two prominent examples—Sri Trang Agro-Industry Public Company Limited (STA) and Thai Eastern Group Holdings Public Company Limited (TEGH)—demonstrate how leading firms are operationalizing compliance requirements and setting benchmarks for the country’s agricultural export sectors.

Sri Trang Agro-Industry (STA), Thailand’s largest fully integrated natural-rubber producer, has adopted proactive measures to ensure deforestation-free and legally produced materials across its supply chain. As reported in its Sustainability Report 2024 [

13], STA has implemented traceability verification for all product categories, including technically specified rubber (TSR), ribbed smoked sheet (RSS), and concentrated latex. The company established procurement centers close to smallholder farming areas and developed two digital applications—Sri Trang Friends and Sri Trang Friends Station—to enable real-time transactions, transparent pricing, and digital recording of farm-level purchases. These platforms allow smallholders to sell directly to STA factories while capturing geolocation and transaction data necessary for EUDR due diligence documentation. Through these initiatives, STA has transformed compliance into an opportunity for digital inclusion and sustainable sourcing, offering a scalable model of farmer engagement and traceability that aligns with EUDR objectives.

Similarly, Thai Eastern Group Holdings (TEGH) has incorporated EUDR compliance into its broader environmental, social, and governance (ESG) strategy under the “Thai Eastern Symbiosis” model. According to its Sustainability Report 2024 [

35], the company applies a risk-based management framework supported by polygon-based geolocation mapping and supplier legality verification. By the end of 2024, TEGH had registered 485,524 rai of cultivation area under its traceability system, with 82% of suppliers adopting digital monitoring tools and 89.8% of raw materials verified as deforestation-free. The company also trained 44,607 smallholder farmers in data literacy and compliance practices, leading to 46.6% of block-rubber sales in the final quarter of 2024 being certified as EUDR-compliant. These efforts are linked to TEGH’s long-term sustainability goals, including carbon neutrality by 2030 and net-zero emissions by 2050, illustrating how EUDR alignment can be integrated with corporate climate strategies.

Together, these two cases provide compelling evidence that large, vertically integrated enterprises in Thailand are not only prepared for EUDR enforcement but are also turning compliance into a source of competitive advantage. Both firms have leveraged digital innovation, stakeholder training, and ESG governance to maintain access to EU markets and enhance brand credibility. However, their progress also highlights the growing disparity between large companies and small and medium-sized enterprises, which continue to face resource and technological constraints. Thus, while the EUDR imposes new regulatory pressures, it simultaneously acts as a catalyst for modernization, digital transformation, and collaborative sustainability in Thailand’s agri-forestry sector.

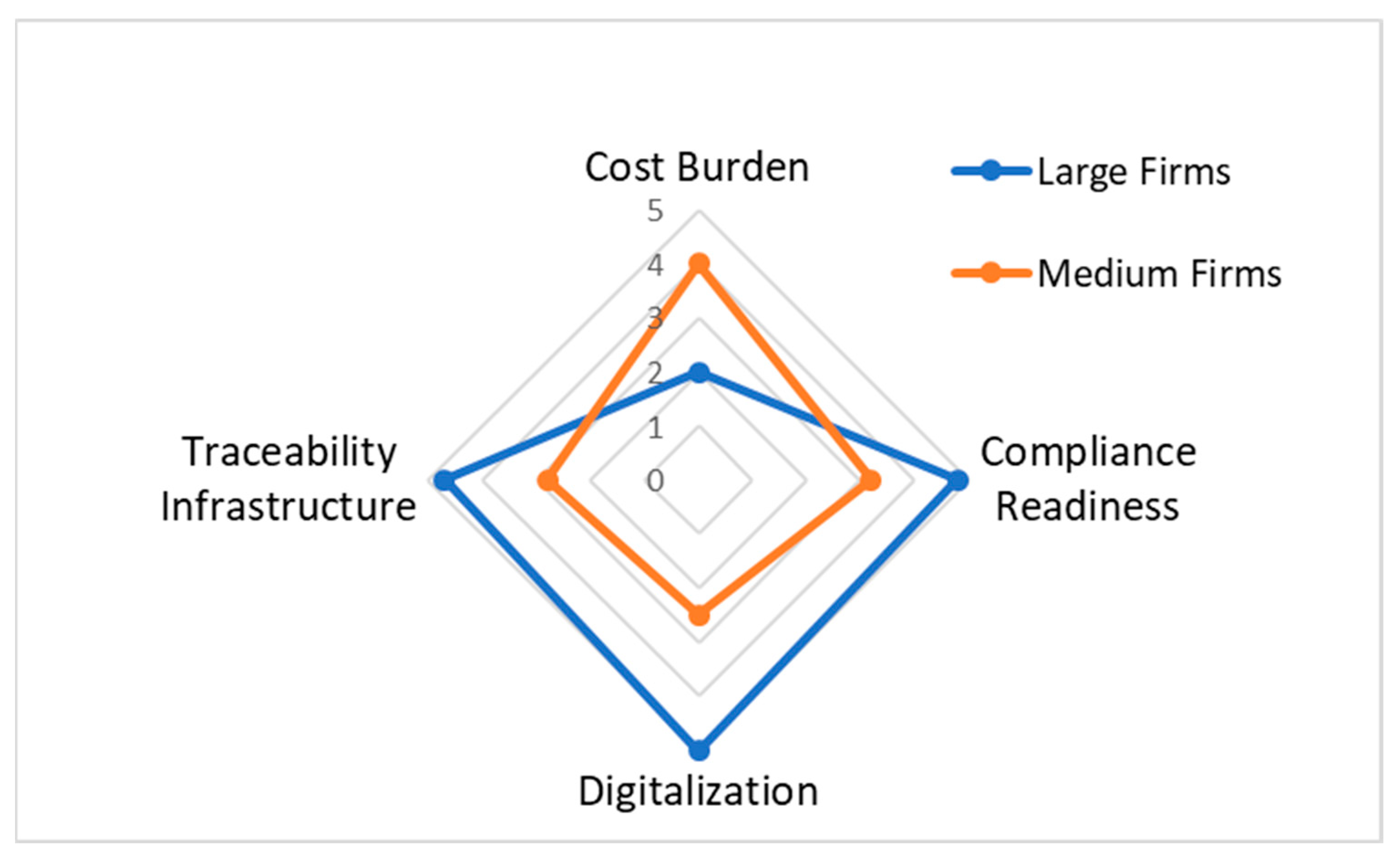

To complement the qualitative insights presented earlier,

Figure 3 summarizes the relative readiness of large and medium-sized Thai firms across four analytical dimensions: cost burden, compliance readiness, digitalization, and traceability infrastructure. The scores (1 = very low to 5 = very high) were derived from the survey, expert interviews, and corporate sustainability reports, following a quantitizing approach that translates qualitative data into ordinal measures for comparison [

54].

The results show a pronounced asymmetry in readiness between firm sizes. Large enterprises supported by government programs such as the RAOT digital platform—exhibit high compliance readiness (4.8 / 5), full digitalization (5 / 5), and strong traceability performance (4.7 / 5). These findings align with recent disclosures by Sri Trang Agro-Industry and Thai Eastern Group Holdings, which have implemented polygon-based mapping, mobile traceability applications, and extensive farmer training programs [

35,

53]. In contrast, medium-sized firms record lower scores across all categories, particularly in digitalization (2.5 / 5) and traceability (2.8 / 5), reflecting limited technical capacity and partial integration of EUDR requirements. The 5–10 percent cost increase reported by medium firms further confirms the higher financial burden identified in earlier studies of environmental trade regulations [

45,

47]. Overall, this comparative assessment reinforces that firm size and resource capacity remain decisive factors for EUDR adaptability—consistent with broader findings that unequal digital infrastructure and institutional support shape compliance trajectories in developing-country exporters [

32,

48].

4.4. Differentiated Readiness and Compliance Pathways of Thai Firms Under the EUDR

The analysis of compliance pathways builds upon both qualitative evidence and secondary data to interpret how Thai firms are positioned along the EUDR implementation timeline. Using information from survey responses, interview insights, and company sustainability reports, firm readiness was categorized by size to assess varying levels of capacity, opportunity, and institutional support.

The analysis of compliance pathways reveals that Thai firms are progressing at different speeds in preparing for the EUDR. While the regulatory framework applies uniformly, the ability to comply varies widely depending on firm size, resource capacity, and supply-chain integration. The EUDR Compliance Burden Summary (

Table 2) illustrates how small, medium, and large enterprises experience distinct opportunities and challenges under the regulation, reflecting their uneven readiness and institutional support levels.

Small firms are identified as having “not yet started” the compliance process. Their main opportunity lies in collective compliance through cooperatives and associations, which can reduce costs and enable access to shared digital traceability systems [

32]. However, their greatest challenges remain limited awareness, insufficient technical capacity, and a lack of traceability tools [

47,

48]. Given these constraints, smallholders are classified as a high-priority group with an extended compliance deadline of 30 June 2026, acknowledging their critical role in inclusive EUDR implementation.

Medium-sized firms, categorized as “in progress”, are partly engaged in compliance. Their main opportunity lies in collaborating with industry associations and cooperatives to share resources and standardize documentation. Nevertheless, they face downstream pressure from EU buyers demanding stronger deforestation-free assurances, which narrows profit margins and raises operational uncertainty. Thus, they are identified as a medium-priority group, with a deadline of 30 December 2025, reflecting their intermediate stage of readiness.

Large firms, labelled as “under review”, are the most advanced in EUDR alignment. Companies such as Sri Trang Agro-Industry and Thai Eastern Group Holdings have invested in digital traceability platforms, polygon-based mapping, and farmer registries to verify legality and deforestation-free sourcing [

35,

53]. However, their visibility also increases reputational risk in the event of non-compliance [

49]. These firms are therefore considered low-priority in terms of support needs but remain under high public and investor scrutiny to lead implementation by December 2025.

Overall, the table illustrates that EUDR compliance among Thai firms follows three distinct pathways—delayed, transitional, and proactive—corresponding to firm size and resource capacity. While small and medium firms require targeted support and collective strategies, large enterprises have transformed compliance into a competitive advantage, demonstrating how regulation can drive digitalization and governance reform within Thailand’s Agri-forestry sector.

5. Conclusions

This study examined how the EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR) affects Thai businesses across different firm sizes, focusing on how structural disparities shape their ability to comply with deforestation-free trade standards. The findings reveal a persistent asymmetry in compliance capacity. Large enterprises generally exhibit stronger digital readiness, traceability infrastructure, and institutional alignment with EUDR requirements, while small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) face significant barriers due to limited financial resources, technical expertise, and fragmented supply chains. These disparities highlight that, although the EUDR promotes environmental accountability, its uniform standards risk amplifying existing inequalities in trade readiness and access to technology.

The analysis underscores that effective implementation of deforestation-free trade requires more than regulatory compliance—it demands systemic support to build inclusive capacity across all firm sizes. Three strategic interventions are therefore recommended. First, national authorities should strengthen technical and financial assistance for SMEs, promote interoperability among digital traceability platforms, and integrate EUDR alignment into broader green-growth and digitalization strategies. Second, the European Union should consider transitional mechanisms and mutual recognition of equivalent local systems to prevent disproportionate exclusion of smaller exporters. Third, the private sector should foster collective traceability solutions, shared data infrastructures, and industry-wide partnerships that lower compliance costs while enhancing transparency and market confidence.

Overall, Thailand’s experience demonstrates that environmental regulation, when implemented through inclusive policy frameworks and coordinated public–private action, can serve as a catalyst for modernization, innovation, and equitable participation in global markets. Ensuring that deforestation-free trade delivers both environmental integrity and social fairness will depend on sustained cooperation between Thai institutions, EU authorities, and regional partners, aligning sustainability governance with development equity across the agricultural and forestry sectors.

Supplementary Materials

The following supplementary materials are available for this study: 1. Survey for Thai Firms: A structured questionnaire distributed to representatives of Thai companies operating in EUDR-covered sectors, including rubber, palm oil, and paper. The survey aimed to collect qualitative and quantitative insights on firm-level awareness, compliance readiness, cost implications, and traceability practices in preparation for the EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR).

https://docs.google.com/forms/d/1AiNAZrH5e-v7aSB__yf-0omdm4tZB2yjLWwZFZiNspI/. 2. Survey for Regulators and Policy Experts: A targeted instrument distributed to Thai government officials and EU policy representatives to evaluate institutional readiness, inter-agency coordination, and perceived challenges in implementing the EUDR at the national level.

https://docs.google.com/forms/d/1k8BEcBzSKONomdgPL5aSU-Vp0g_EgJ8Dg_dfnORcsVc. Responses from both surveys were used to triangulate perspectives between the private and public sectors, supporting the comparative analysis of regulatory alignment, digital infrastructure, and firm adaptability discussed in the main text.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M., E.D.A., and N.S.; methodology, S.M. and E.D.A.; validation, S.M, E.D.A., and N.S.; formal analysis, S.M. and E.D.A.; investigation, S.M. and E.D.A; data curation, S.M. and E.D.A.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M.; writing—review and editing, S.M., E.D.A., and N.S.; visualization, S.M., E.D.A.; supervision, E.D.A and N.S.; project administration, N.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to Dr. Michael Bucki, Counsellor for Environment, Agriculture, and Health at the Delegation of the European Union to Thailand, for his invaluable insights and expert perspectives on the implementation and policy implications of the EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR) in Thailand. His contribution provided essential context for understanding the intersection of trade, sustainability, and governance in the Thai agricultural sector. The authors also wish to thank the participating companies and associations—including the Member of the Pulp and Paper Industry Club, as well as representatives from the rubber and wood industries—for their time and thoughtful responses to the survey. Appreciation is further extended to Sri Trang Agro-Industry and Thai Eastern Group Holdings for the transparency of their sustainability disclosures, which significantly enriched the case study analysis. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used OpenAI, GPT-5 for the purposes of language refinement, formatting consistency, and citation management. All analytical content, interpretations, and conclusions were developed by the authors. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The views expressed in this study are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of any affiliated institutions or stakeholders mentioned.

References

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020: Main Report; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Regulation (EU) 2023/1115 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 31 May 2023 on the Making Available on the Union Market and the Export from the Union of Certain Commodities and Products Associated with Deforestation and Forest Degradation and Repealing Regulation (EU) No 995/2010. Off. J. Eur. Union 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kothke, M.; Lippe, M.; Elsasser, P. Comparing the Former EUTR and Upcoming EUDR: Some Implications for Private Sector and Authorities. Forest Policy Econ. 2023, 157, 103079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berning, L.; Sotirov, M. Hardening Corporate Accountability in Commodity Supply Chains under the EU Deforestation Regulation. Regul. Gov. 2023, 17, 870–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berning, L.; Sotirov, M. The Coalitional Politics of the European Union Regulation on Deforestation-Free Products. Forest Policy Econ. 2024, 158, 103102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendrill, F.; Persson, U.M.; Godar, J.; Kastner, T. Deforestation Displaced: Trade in Forest-Risk Commodities and the Prospects for a Global Forest Transition. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 055003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, P.G.; Slay, C.M.; Harris, N.L.; Tyukavina, A.; Hansen, M.C. Classifying Drivers of Global Forest Loss. Science 2018, 361, 1108–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoang, N.T.; Kanemoto, K. Mapping the Deforestation Footprint of Nations Reveals Growing Threat to Tropical Forests. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 5, 845–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henders, S.; Persson, U.M.; Kastner, T. Trading Forests: Land-Use Change and Carbon Emissions Embodied in Production and Exports of Forest-Risk Commodities. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 125012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambin, E.F.; Gibbs, H.K.; Heilmayr, R.; Carlson, K.M.; Fleck, L.C.; Garrett, R.D.; Walker, N.F. The Role of Supply-Chain Initiatives in Reducing Deforestation. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabs, J.; Cammelli, F.; Levy, S.A.; Garrett, R.D. Designing Effective and Equitable Zero-Deforestation Supply Chain Policies. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2021, 70, 102357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, S.E.M.C.; dos Santos, L.B.; Lima, C.F. The European Union and United Kingdom’s Deforestation Regulation: Comparative Implications for Supply Chains. Land Use Policy 2024, 137, 106872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, S.E.M.C.; dos Santos, L.B.; Silva, R.A. Compliance Readiness for EU Deforestation-Free Supply Chains: A Brazilian Case Study. Ecol. Econ. 2024, 214, 107081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallemore, C. Commodity Governance and the EU Deforestation Regulation: Implications for Supply Chain Transparency. Land Use Policy 2025, 137, 106859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, C. The EU Deforestation Regulation: Global Implications for Commodity Trade. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2025, 72, 102526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainforest Alliance. How the Rainforest Alliance Supports EUDR Compliance from Farm to Retailer; 2024. Available online: https://www.rainforest-alliance.

- ClientEarth. Getting to “Deforestation-Free”: Clarifying the Traceability Requirements in the Proposed EU Deforestation Regulation; 2022. Available online: https://www.clientearth.

- OECD; FAO. OECD–FAO Business Handbook on Deforestation and Due Diligence in Agricultural Supply Chains; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhunusova, E.; Ahimbisibwe, V.; Sen, L.T.H.; Sadeghi, A.; Toledo-Aceves, T.; Kabwe, G.; Günter, S. Potential Impacts of the Proposed EU Regulation on Deforestation-Free Supply Chains on Smallholders, Indigenous Peoples, and Local Communities in Producer Countries outside the EU. Forest Policy Econ. 2022, 143, 102817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkes, C.; Peter, G. Traceability Matters: A Conceptual Framework for Deforestation-Free Supply Chains Applied to Soy Certification. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2020, 11, 1159–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demestichas, K.; Peppes, N.; Alexakis, T.; Adamopoulou, E. Blockchain in Agriculture Traceability Systems: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Turner, P. Blockchain Applications in Forestry: A Systematic Literature Review. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, K.M.; Heilmayr, R.; Gibbs, H.K.; Noojipady, P.; Burns, D.N.; Morton, D.C.; Kremen, C. Effect of Oil Palm Sustainability Certification on Deforestation and Fire in Indonesia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackman, A.; Goff, L.; Rivera Planter, M. Does Eco-Certification Stem Tropical Deforestation? FSC Certification in Mexico. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2018, 89, 306–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, T.; Grabs, J.; Chong, A.E. Mainstreamed Voluntary Sustainability Standards and Their Effectiveness: Evidence from the Honduran Coffee Sector. Regul. Gov. 2021, 15, 333–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preferred by Nature. Study on Certification and Verification Schemes in the Forest Sector and for Wood-Based Products; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RSPO. The RSPO System as a Tool to Help Companies Comply with Requirements of the EU Deforestation Regulation; 2023. Available online: https://rspo.

- United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP). The Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism and Its Implications for Asia-Pacific Developing Countries; UNESCAP: Bangkok, Thailand, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Krungsri Research. EU Deforestation Regulation: Implications for Thai Exports; Bank of Ayudhya: Bangkok, Thailand, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Agroberichten Buitenland. Thailand Advances Deforestation-Free Agri-Food Systems amid EUDR Implementation; Government of the Netherlands: Bangkok, Thailand, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- The Nation. Thai SMEs Face Risks of EU Market Exclusion under EUDR. Thai SMEs Face Risks of EU Market Exclusion under EUDR. The Nation Thailand 2023.

- FAO. EU Deforestation Regulation: Guidance for Smallholder Inclusion in Commodity Supply Chains; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. EUDR Country Benchmarking Methodology and Risk Classification System; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sri Trang Agro-Industry Public Company Limited (STA). Sustainability Report 2024; STA: Songkhla, Thailand, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Thai Eastern Group Holdings Public Company Limited (TEGH). Sustainability Report 2024; TEGH: Chonburi, Thailand, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bucki, M. Expert Interview: Counsellor for Environment, Agriculture and Health, Delegation of the European Union to Thailand. Conducted via Zoom, 25. 20 February.

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldaña, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook, 4th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- LiveEO. Frequently Asked Questions: EU Deforestation Regulation; 2024. Available online: https://green-forum.ec.europa.

- Lambin, E.F.; Furumo, P.R. Deforestation-Free Commodity Supply Chains: Myth or Reality? Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2023, 48, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendrill, F.; Gardner, T.A.; Meyfroidt, P.; Persson, U.M.; Adams, J.; Azevedo, T.; West, C. Disentangling the Numbers behind Agriculture-Driven Tropical Deforestation. Science 2022, 377, eabm9267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasconcelos, A.A.; Lima, M.G.B.; Gardner, T.A.; McDermott, C.L. Prospects and Challenges for Policy Convergence between the EU and China to Address Imported Deforestation. Forest Policy Econ. 2024, 162, 103183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zu Ermgassen, E.K.H.J.; Lima, M.G.B.; Bellfield, H.; Dontenville, A.; Gardner, T.; Godar, J.; Meyfroidt, P. Addressing Indirect Sourcing in Zero-Deforestation Commodity Supply Chains. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabn3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bager, S.L.; Lambin, E.F. How Do Companies Implement Their Zero-Deforestation Commitments? J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 375, 134056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyfroidt, P.; Lambin, E.F.; Erb, K.-H.; Hertel, T.W. Globalization of Land Use: Distant Drivers of Land Change and Geographic Displacement of Land Use. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2013, 5, 438–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, S.E.M.C.; dos Santos, L.B.; Silva, R.A.; Lima, C.F. Governance Challenges in Implementing Deforestation-Free Supply Chains: Insights from the Brazilian Soy and Cattle Sectors. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 314, 128007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berihun, M.L.; Taffesse, A.S.; Teklewold, H. Sustainability Standards and Inclusive Compliance: Smallholder Adaptation to Environmental Trade Regulations. World Development 2024, 174, 106352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berihun, M.L.; Taffesse, A.S.; Teklewold, H. Procedural Compliance Barriers in Developing Country Exports under Environmental Regulations. Ecological Economics 2024, 211, 107454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendrill, F.; Persson, U.M.; Godar, J.; Kastner, T. Deforestation Displaced: Trade in Forest-Risk Commodities and the Prospects for a Global Forest Transition. Environmental Research Letters 2019, 14, 055003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takacs, D.; Schmitz, A.; Ruysschaert, D. Policy Delays and Market Uncertainty in Environmental Trade Regulation: Lessons from Deforestation-Free Commodity Initiatives. Forest Policy and Economics 2022, 140, 102840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berihun, M.L.; Taffesse, A.S.; Teklewold, H. Environmental Regulation and SME Competitiveness in Agricultural Exports: Evidence from Ethiopia. Journal of Environmental Management 2024, 361, 121640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, R.J.; Reams, G.A.; Achard, F.; de Freitas, J.V.; Grainger, A.; Lindquist, E. Dynamics of Global Forest Area: Results from the FAO Global Forest Resources Assessment 2015. Forest Ecology and Management 2015, 352, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sri Trang Agro-Industry Public Company Limited (STA). Sri Trang Sustainability Report 2024: Traceability and Deforestation-Free Supply Chains; STA: Songkhla, Thailand, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sri Trang Agro-Industry Public Company Limited (STA). Sri Trang Friends Application Overview; STA: Songkhla, Thailand, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M. B. , Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2018). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).