1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder and the leading cause of dementia worldwide [

1]. Its pathological hallmarks include extracellular aggregation of amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides into plaques and intracellular accumulation of hyperphosphorylated tau in the form of neurofibrillary tangles, both of which disrupt synaptic integrity and neuronal homeostasis, leading to widespread neurodegeneration [

2]. Recently, several disease-modifying anti-Aβ monoclonal antibody therapies have entered the clinic; however, significant challenges remain due to their relatively modest effects, the need for serial MRI monitoring to detect potentially severe side effects and the fact that only patients in the early stages of AD can be treated [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Targeting tau has been proposed as a potentially superior therapeutic strategy to amyloid, as the formation of neurofibrillary tangles closely coincides with the onset of dementia symptoms and more accurately predicts patterns of clinical decline [

9,

10,

11]. Various strategies to target tau pathology in AD have previously been explored with multiple approaches in late-stage clinical trials [

3,

12,

13]. Nucleic acid–based therapeutics, such as antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), provide an opportunity to modify disease progression in AD by downregulating overexpressed genes [

14]. ASOs targeting the MAPT gene (MAPT-ASOs), which encodes for the tau protein, reduce expression by binding to tau mRNA and recruiting RNase H1, which degrades the transcript and prevents tau protein synthesis [

14]. In a Phase 1b clinical study, the MAPT-ASO candidate BIIB080 demonstrated a dose-dependent and sustained reduction of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) total tau and phosphorylated tau (p-tau) and is currently being further evaluated in a Phase 2 trial, thus highlighting the clinical potential of MAPT-ASOs in treating AD [

15,

16].

A major obstacle in the development of AD therapies is the limited penetration of drugs into the brain due to the restrictive nature of the blood–brain barrier (BBB) [

17]. The BBB is a highly selective interface at the brain microvasculature, composed of brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMECs), astrocytes, pericytes, and extracellular matrix components such as the vascular basement membrane and the intraluminal glycocalyx [

18]. BMECs are interconnected by complex tight junctions that strongly limit paracellular transport, forcing most therapeutics to rely on the transcellular pathway for entry into the central nervous system (CNS) [

19]. As a result, drug penetration is poor, often necessitating high systemic doses to achieve therapeutic concentrations in the brain [

17]. ASOs are no exception, as their relatively large size, strong negative charge, and hydrophilicity prevent passive diffusion across the BBB [

20]. Consequently, current clinical trials of MAPT-ASOs employ intrathecal administration, an invasive and repeated procedure associated with uneven brain distribution, procedural risks, and limited patient tolerability [

15,

16]. To address these limitations and enable systemic delivery, ASOs can be incorporated into lipid nanoparticles such as liposomes, which provide protection against nuclease degradation, improve pharmacokinetic properties, and enhance cellular uptake and endosomal escape [

21]. Functionalizing these liposomes with surface ligands that bind to receptors overexpressed at BMECs facilitates BBB crossing through receptor-mediated transcytosis, thus allowing for CNS-specific systemic delivery [

22,

23,

24].

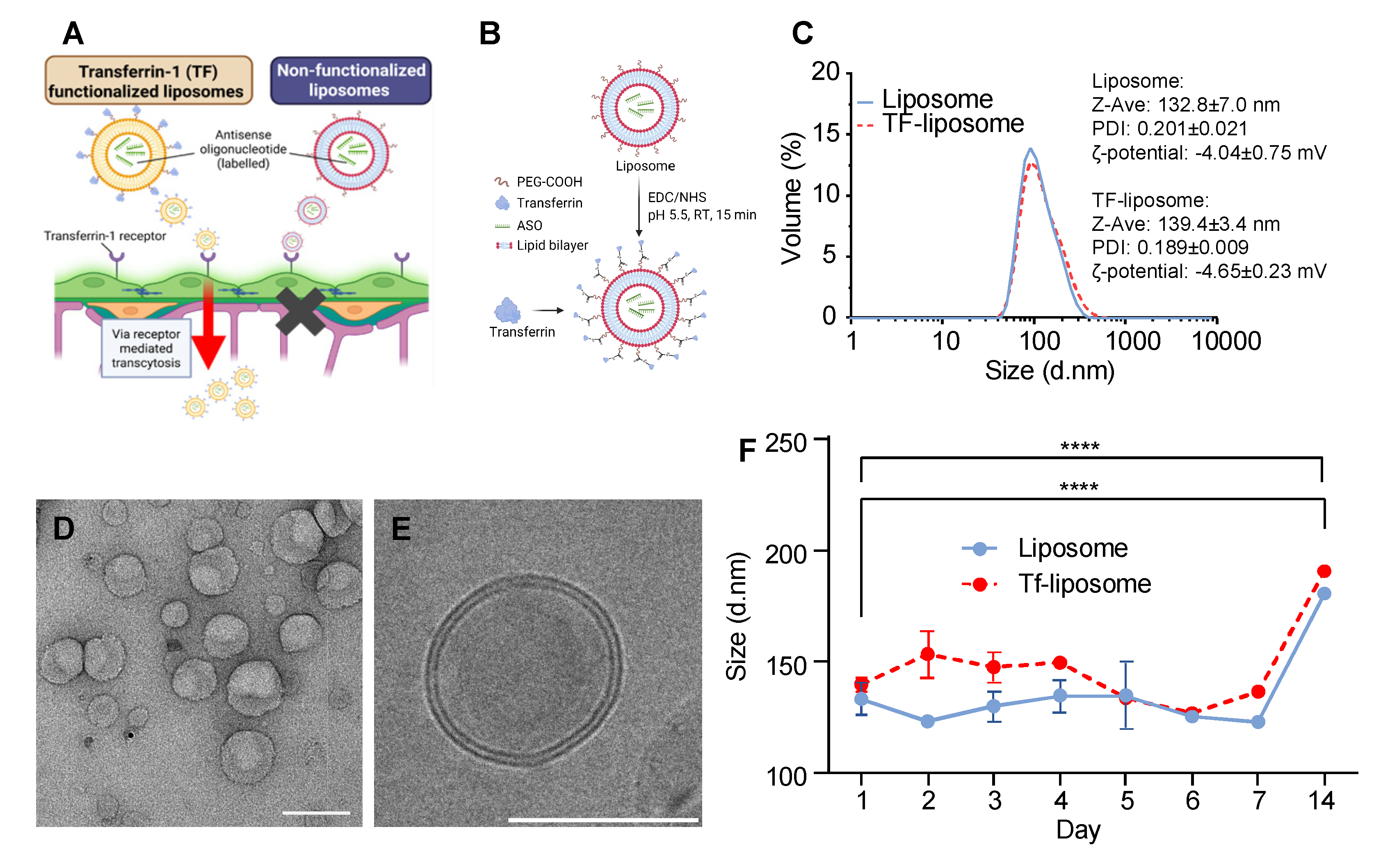

Transferrin receptor 1 (TFR1) is preferentially expressed on the luminal surface of brain BMECs compared to peripheral endothelium, making it an attractive and relatively specific target for delivering substances across the BBB to the CNS [

25]. The physiological role of TFR1 in mediating essential iron transport across the BBB highlights its powerful and active endocytic transport pathway for the delivery of drugs for the treatment of AD. One of the most important features of TFR1 in AD is that its expression levels and functional integrity at the BBB appear to be largely preserved despite AD neuropathology. This is a crucial distinction because many other BBB components, such as tight junctions and efflux transporters, exhibit dysfunction or altered expression in AD, which may complicate the delivery of drugs that rely on their normal function [

26]. Given that transferrin (TF) is a widely tolerated endogenous protein and its conjugates are compatible with scalable chemical systems (EDC/NHS: carboxyl-to-amine; maleimide–thiol; click: fast azide–alkyne), which facilitates its conjugation to various carriers and reduces immunogenicity, in order to allow TF to compete with abundant plasma transferrin and avoid random lysine conjugation interfering with iron binding [

27], TF can be placed on a flexible PEG tether and the surface density of TF can be manipulated to achieve the required affinity for entering endothelial cells.

To evaluate ASO drug delivery strategies, animal models can be used [

21]. However, due to species-specific differences in BBB properties, such as tight junction complexity and TFR1 density, distribution, and ligand-binding characteristics, the translatability of these studies is limited [

28]. In vitro BBB models provide an alternative, yet conventional transwell systems fail to capture the 3D architecture, lack dynamic flow and are further biased by introducing a stiff membrane with non-physiological properties at a critical location in the BBB model [

29]. Self-assembled BBB organoids offer potential high-throughput tools for permeability studies, including nanoparticle evaluation, but they lack a full BBB architecture, allow only for semi-quantitative assessments and may be complex and lengthy to establish [

30,

31]. Hydrogel-based approaches present significant advantages, as cells can organize with cell–cell and cell–extracellular matrix (ECM) interactions that reflect in vivo BBB anatomy. Previous studies have evaluated nanoparticles using hydrogel-based transwell-like systems or self-assembled capillary structures in wells with perfusable openings [

32,

33]. However, these systems still lack fluid flow, an essential factor in BBB physiology and nanoparticle attachment. Microfluidic BBB chips address this limitation by incorporating micro-sized channels that allow controlled fluid flow and simultaneous cell culture [

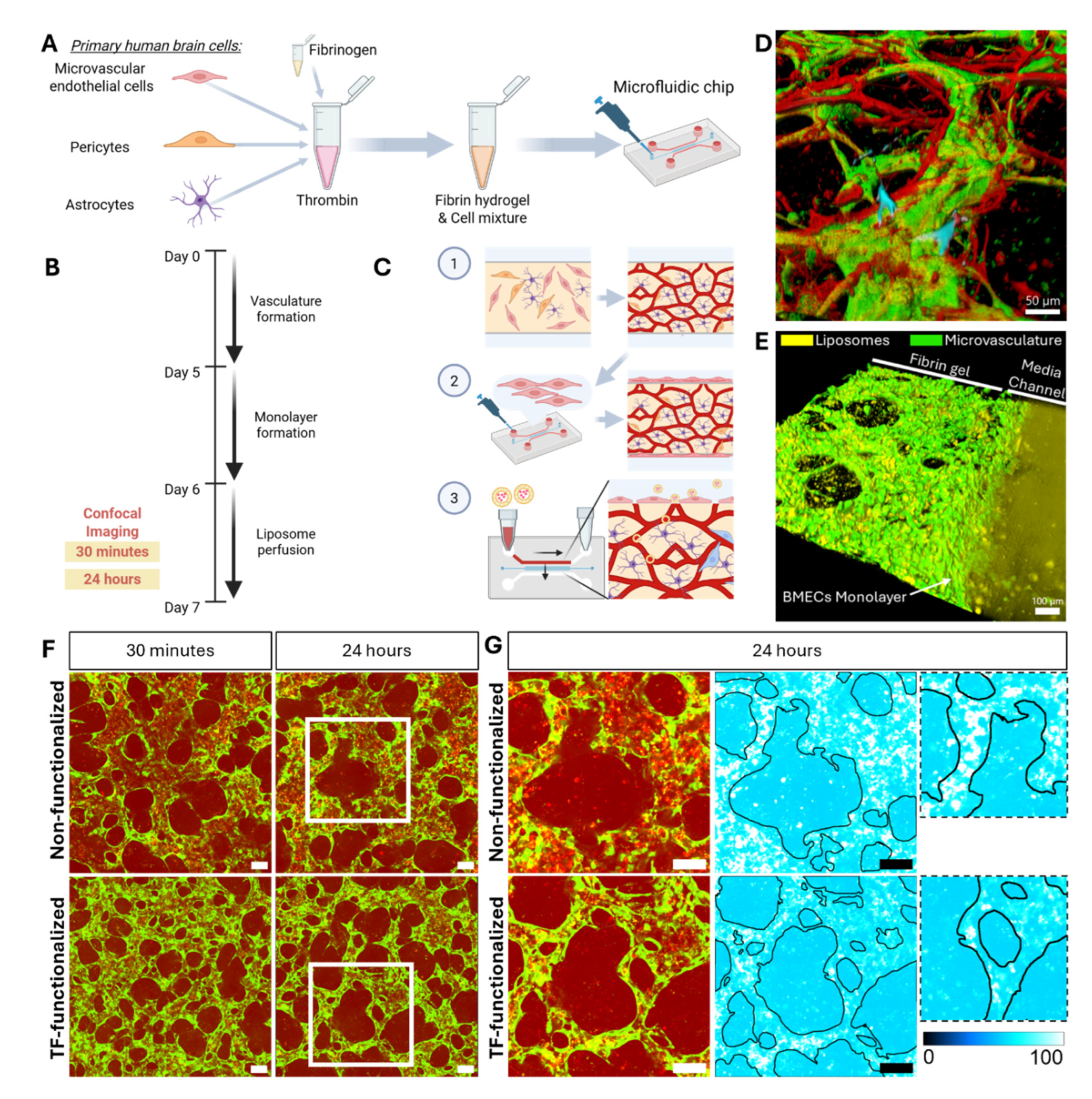

29,

34,

35]. Previously, a perfusable BBB microvasculature network (MVN) model has been developed through self-assembly of brain BMECs, astrocytes, and pericytes within a fibrin hydrogel in a microfluidic chip [

36,

37]. This model accurately recapitulates in vivo BBB architecture, including the formation of luminal microvessels with astrocytes and pericytes actively aligning and interacting with the endothelium [

36,

37]. Moreover, physiologically relevant expression and localization of BBB membrane transporters, tight junction proteins, and extracellular matrix components, as well as cytokine production, were observed, with permeability values comparable to those observed in rat brains [

36,

37]. Importantly, TFR1 expression in BMECs increases during the formation of the MVNs [

37] and is ultimately higher in BMECs cultured as MVNs than in 2D monocultures [

36], highlighting how such approaches enhance physiological relevance and are therefore particularly suitable for studying TF-mediated delivery. Previous studies have shown that nanoparticle size and functionalization can be effectively evaluated for BBB permeability using this BBB MVN model alone or combined with a tumour spheroid [

38,

39].

In this study, we investigated whether TF-functionalized liposomes encapsulating MAPT-ASOs could enhance BBB permeability using the previously published and well-characterized 3D BBB MVN in vitro model [

36,

37,

38]. We hypothesized that TF-functionalization would enhance the permeability of MAPT-ASO–loaded liposomes across the BBB MVN in vitro model. To test this, TF-functionalized and control liposomes were perfused through the BBB MVNs and MAPT-ASO delivery was monitored by fluorescent labelling and confocal microscopy to assess translocation across the BBB over 24 hours. This work not only evaluates transferrin-targeted liposomes as a delivery strategy for MAPT-ASOs but also introduces novel methodologies for leveraging the 3D BBB MVN model as a versatile platform for nanoparticle evaluation.

3. Discussion

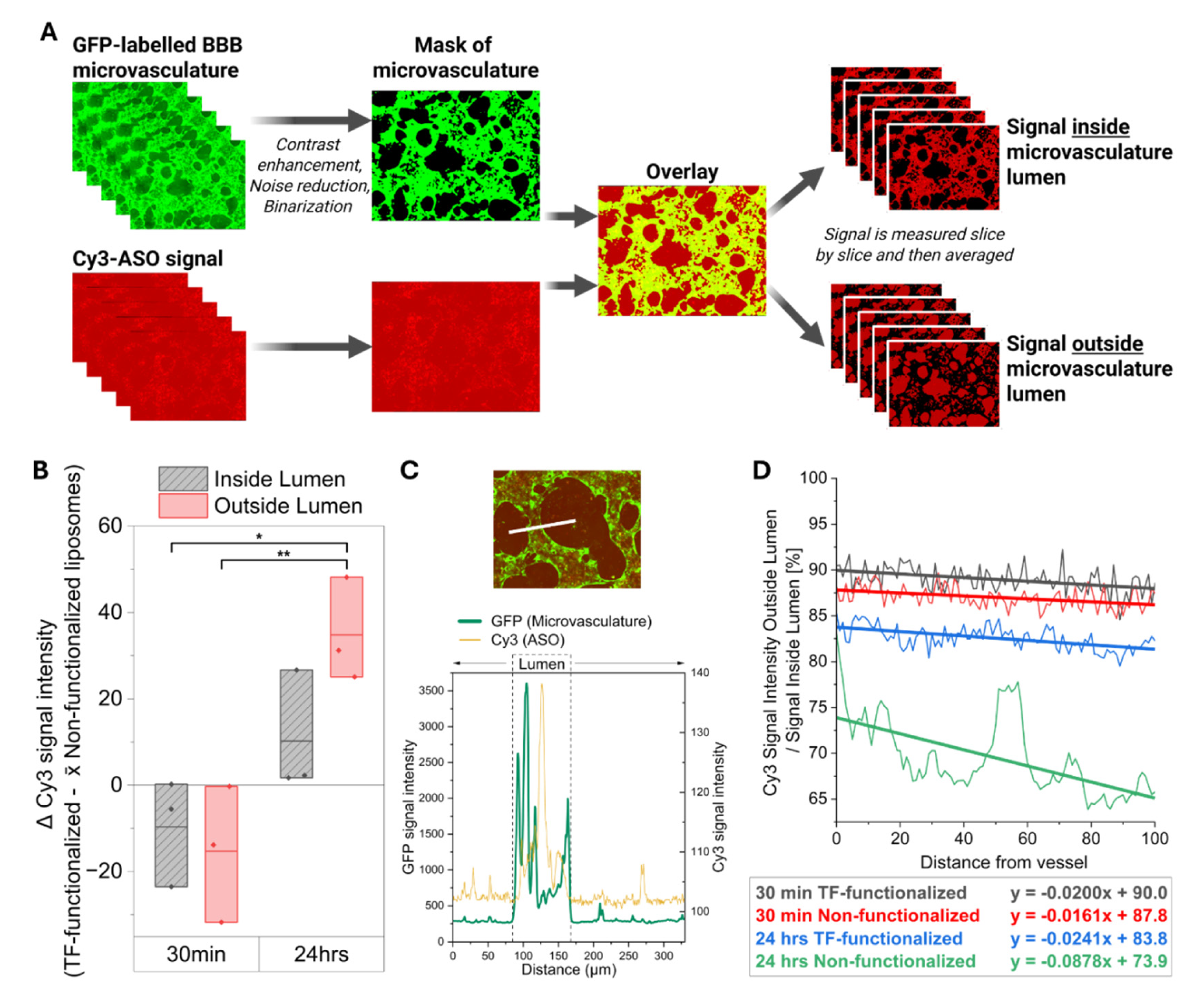

In this study, we evaluated whether transferrin-functionalized liposomes loaded with antisense oligonucleotides targeting the MAPT gene (MAPT-ASO) could enhance delivery across the BBB in a 3D in vitro model of human brain microvasculature. After demonstrating that the here used MAPT-ASO was indeed effective in lowering tau levels and protecting against axonal degeneration, we then showed that transferrin-functionalized liposomes were able to enhance the delivery of the MAPT-ASO across the BBB after 24 hours compared to the non-functionalized liposomes. This has direct implications for developing novel therapeutic strategies to protect against tau pathology in AD but also provides further evidence and methodologies to use the 3D microvascular BBB in vitro model for nanoparticle testing.

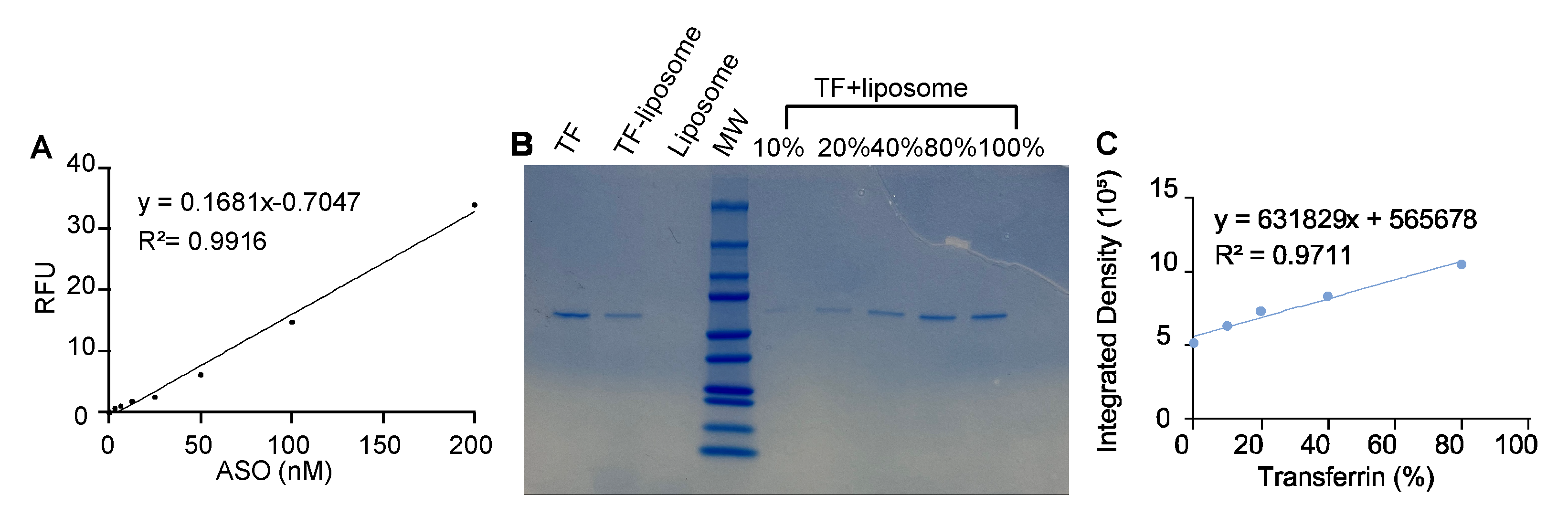

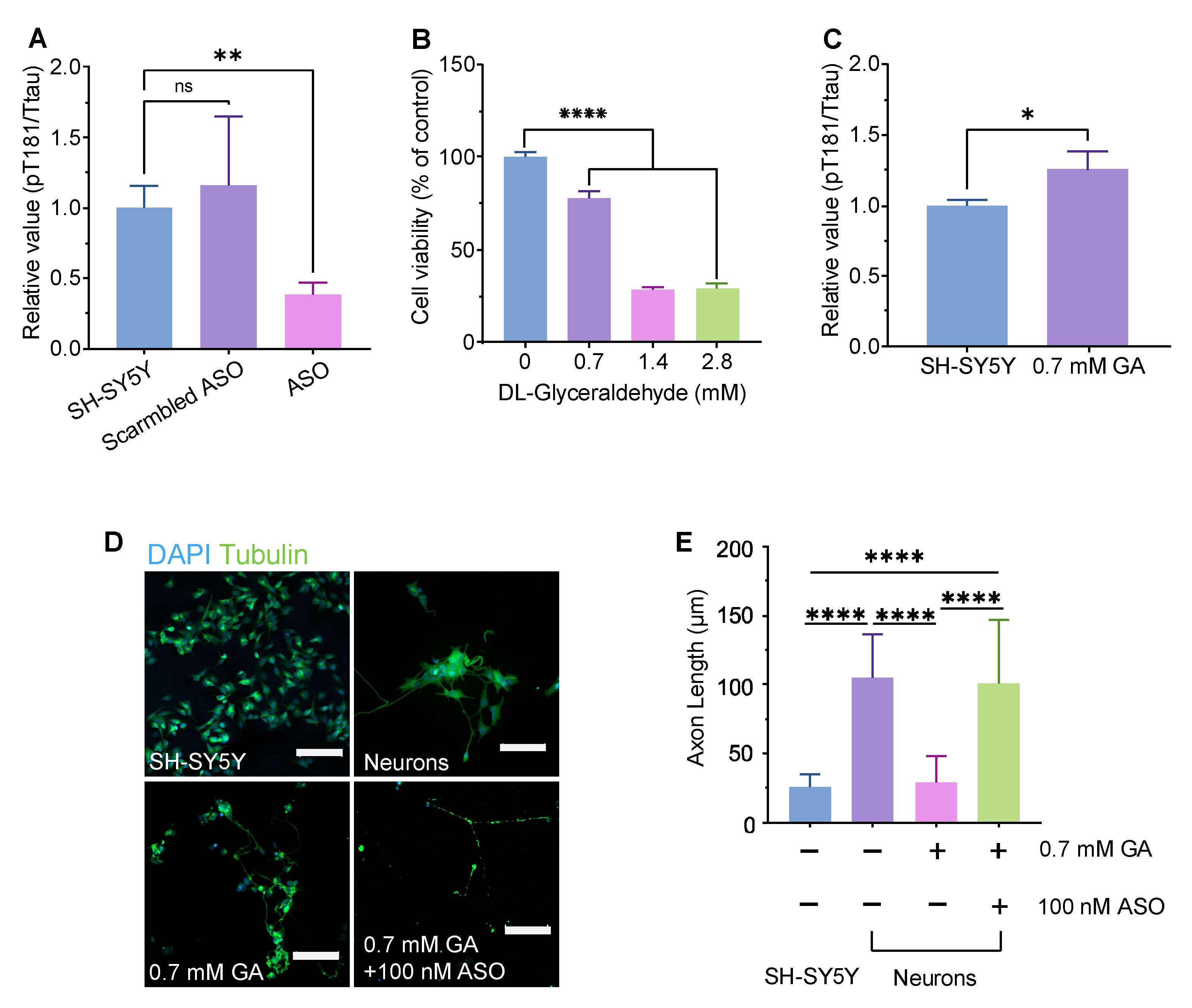

The ASO used here is a fully phosphorothioate oligo directly targeting human MAPT pre-mRNA. By hybridizing to MAPT mRNA, the ASO recruits RNase H1 to cleave the target transcripts, thereby lowering MAPT mRNA and reducing tau protein synthesis [

44]. Using a well-established DL-glyceraldehyde (GA)–induced axonal degeneration approach in SH-SY5Y–derived neurons [

40], we found that GA reduced viability in a dose-dependent manner (0.7–2.8 mM). CLSM revealed marked neurite fragmentation after 0.7 mM GA, which was rescued by co-treatment with the MAPT-ASO. GA significantly shortened axons relative to untreated neurons, whereas GA + MAPT-ASO significantly increased axon length compared with GA alone. In parallel, the MAPT-ASO significantly lowered the pT181/total Tau ratio versus both untreated and scramble-ASO controls. These results illustrate that MAPT knockdown reduces pathogenic tau phosphorylation at Thr181 and mitigates axonal damage under metabolic stress in this neuronal model. These findings align with prior human data showing that intrathecal administration of this MAPT-targeting ASO produces reductions in CSF tau species and engages its intended RNase-H mechanism in patients with early AD [

16]. Future studies should evaluate the long-term effects of MAPT-ASO treatment on neuronal connectivity and synaptic function, as well as its efficacy in in vivo models of Alzheimer’s disease.

The liposomes prepared in this study exhibited a particle size of 132.8 nm, which increased only modestly to 139.4 nm after TF functionalization. This size falls within the optimal range for crossing the BBB via receptor-mediated transcytosis and is also favourable for efficient endocytosis by neuronal cells. The slight decrease in PDI from 0.201 to 0.189 further confirms that the liposome population remained highly monodisperse and uniform during TF attachment. The slightly negative ζ-potential (−4.04 and −4.65 mV) indicates minimal electrostatic stabilization; however, steric hindrance from PEG chains likely ensures colloidal stability, while near-neutral charge may reduce nonspecific interactions and improve biocompatibility. During perfusion in the microvasculature BBB network model, some aggregation was visible, further highlighting the need for additional improvements in colloidal stability in future formulations. However, during storage at 4 °C, the liposomes remained stable over 7 days, showing no significant change in size, confirming the robustness of the formulation. Transferrin was covalently conjugated to the liposome surface via the carboxyl group of DSPE-PEG(2000)-COOH, allowing stable grafting while preserving the protein’s orientation and functionality for receptor recognition, which is critical for efficient receptor-mediated uptake. The ASO encapsulation efficiency (48.3 ± 1.6%) and TF grafting rate (39.2 ± 11.2%) are sufficient to demonstrate payload delivery and receptor-mediated targeting in this study, though affinity-based or density-based separation techniques could further improve payload retention and reduce variability. Overall, these physicochemical characteristics, combined with TF functionalization, support receptor-mediated transport across the BBB and effective ASO delivery to neuronal cells.

As expected, TF-functionalized liposomes improved MAPT-ASO delivery across the BBB, consistent with numerous previous studies exploiting the transferrin receptor for drug delivery. In contrast to prior work using a 3D microvasculature BBB model with iPSC-derived endothelial cells (iPSC-ECs), we employed human primary brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMECs) to evaluate nanoparticle transport. In 2D cultures, BBB-relevant genes, including genes interesting for drug delivery such as transferrin receptor (TFR1) and Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor-Related Protein 1 (LRP1), were higher in BMECs compared to iPSC-ECs and HUVECs [

38]. However, the difference between iPSC-ECs and HBMECs diminished when cultured in the 3D co-culture model, suggesting that interactions with astrocytes and pericytes may play a more critical role than endothelial cell source, a notion we similarly observed recently also in HUVECs [

36,

45]. However, BMECs can sustain microvascular networks for longer periods than iPSC-ECs and, in our experience, are easier to incorporate into the microvasculature model [

36].

Earlier studies assessed liposome permeability based on changes in fluorescence intensity within the first 5–30 minutes after nanoparticle administration, a strategy commonly used for barrier integrity testing with tracers such as dextran. However, while this approach is appropriate for detecting paracellular leakiness, TF-functionalized liposomes primarily cross the BBB via receptor-mediated transcytosis, a process that typically requires 1–4 hours in vitro across endothelial monolayers. Moreover, PEGylated liposomes in humans (e.g., Doxil®) exhibit a circulation half-life of approximately 20 to 50 hours, further supporting that longer assessment periods are necessary to capture this sustained exposure and also the slower kinetics of transcellular transport. Indeed, we observed a marked increase in MAPT-ASO delivery efficiency across the extravascular space only after 24 hours. Within the immediate perivascular region, TF-functionalized liposomes provided only a modest improvement after 30 minutes, but this effect became much more pronounced by 24 hours. This finding is particularly relevant as neurons in vivo are typically located within 10–20 µm of brain capillaries, underscoring that TF-functionalized liposomes can substantially enhance MAPT-ASO delivery to their potential neuronal targets over time.

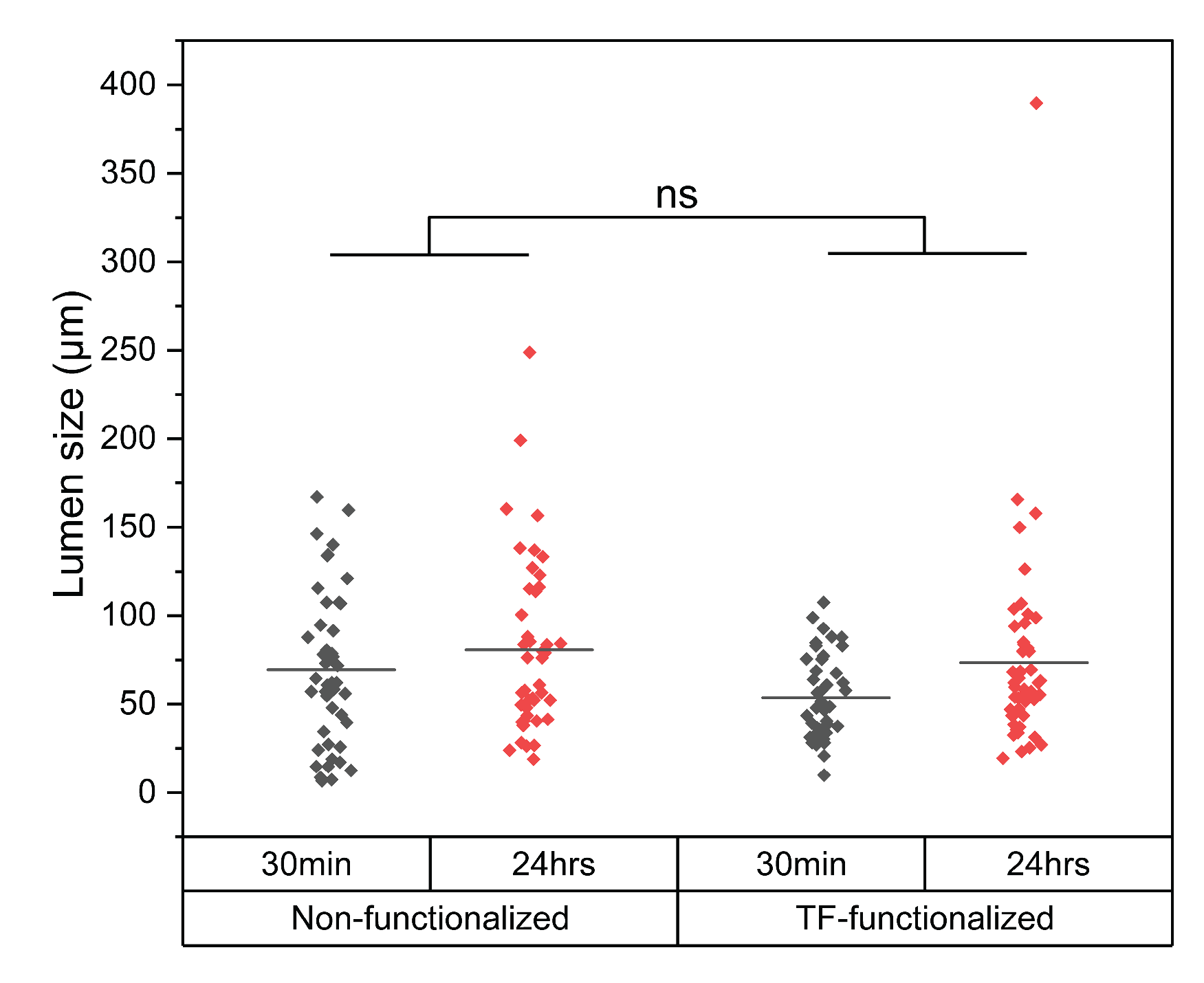

Since liposomes circulate through the brain microvasculature under flow, which likely affects margination and ligand-receptor binding [

46,

47], we applied transient fluid flow using a simple hydrostatic pressure-driven setup, as previously described [

48,

49,

50]. This approach produced a more homogeneous distribution of liposomes across the MVNs compared to static conditions. Consistent with prior reports, we observed that transient fluid flow also promoted larger vessel diameters [

49]. Due to the induced shear stress and the associated beneficial signalling in BMECs [

51], previous studies have shown that fluid flow can extend BBB MVN model viability and enhances MVN perfusability [

48,

49]. Therefore, future studies incorporating stable flow generated by micropumps could support long-term liposome testing, including pre-conditioning and repeated dosing. Integrating such flow systems with robotic handling and automated image analysis would convert the BBB MVN model into a predictive high-throughput platform, as exemplified by other commercially available BBB organ-on-chip systems [

34]. The self-assembled BBB MVN model recapitulates essential microvascular architecture and employs human-derived cell types, features that are expected to enhance translational fidelity relative to simpler BBB in vitro models. Future studies should pursue rigorous validation and directly benchmark the model’s predictive accuracy against in vivo and human clinical data, thereby establishing its suitability as a high-throughput platform for systematic evaluation of BBB drug delivery strategies [

29].

Our study is limited by its focus on liposome-mediated ASO delivery in healthy conditions. Given that BBB dysfunction is a key feature of AD pathology, future work should evaluate liposome-mediated ASO delivery in an AD context. Previous studies have modelled AD in BBB MVNs by co-culture with neurons carrying familial AD (FAD) mutations, resulting in significantly altered gene expression and permeability in MVNs [

48,

50]. However, MVN morphology and perfusability were also significantly altered, making efficient nanoparticle perfusion in AD-impacted MVNs difficult to achieve.

4. Materials and Methods

Cell Culture, ASO Transfection and Protein Extraction

SH-SY5Y cells (ATCC, VA, USA) were cultured in Essential Medium Eagle Medium (EMEM, Sigma Life Science, DE) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS, Sigma Life Science) and 1% (v/v) Penicillin-Streptomycin (P/S, Sigma Life Science) in 6-well plates for 24 hours. Cells were then transfected with 1.35 mM scrambled ASO or ASO using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher, Oxford, UK). Scrambled ASO sequence: 5’-ACCCTTCGAGCTTGAGAGTT-3’; ASO sequence: 5’-GCTTTTACTGACCATGCGAG-3’. After an additional 72 h of incubation, cell lysates were prepared. First, SH-SY5Y cells were detached by 0.25% trypsin-EDTA (Gibco, UK) for 2 min. After the cells were centrifuged at 125× g for 5 min, the resulting pellets were washed twice with ice-cold PBS (Gibco). Radio-Immunoprecipitation Assay buffer (RIPA, Thermo Fisher) supplemented with 1× phosphatase and protease inhibitor (Thermo Fisher) was prepared as the lysis buffer to lyse cell pellets for 30 min on ice. Then, the lysates were centrifuged at 12500 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. Subsequently, the supernatant was collected and transferred into a new microcentrifuge tube for subsequent use.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent (ELISA) Assay

ELISA assays for pT181 and total tau (Thermo Fisher) were performed according to the manufacturer’s protocols. For pT181 quantification, 50 µl of each sample was mixed with 50 µl of detection antibody solution and incubated at 4 °C for 17 hours. For total tau quantification, 50 µl of each sample was mixed with 50 µl of standard dilution buffer and incubated at room temperature for 2 hours. Following incubation, wells were aspirated and washed four times with 1× Wash Buffer. Subsequently, 100 µl of the corresponding conjugate solution (anti-rabbit IgG HRP for pT181; human total tau–biotin conjugate followed by streptavidin–HRP for total tau) was added to each well and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. After washing, 100 µl of stabilized chromogen was added and incubated for 30 min in the dark. Reactions were terminated with 100 µl of Stop Solution, and absorbance was measured at 450 nm within 2 hours.

Cell Viability Assay

SH-SY5Y cells were cultured in MEM supplemented with 10% v/v FBS and 1% v/v P/S in 96-well plates for 24 hours, followed by treatment with glyceraldehyde (GA, Thermo Fisher) at a concentration of 0, 0.7, 1.4, and 2.8 mM. All assays were performed after an additional 24 h incubation. MTT solution was then added to each well to a final concentration of 0.455 mg/ml. After 2 hours of incubation, the 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-Diphenyltetrazolium Bromide (MTT, Thermo Fisher) solution was removed, and 100 µl of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Thermo Fisher) was added to each well. The absorbance was measured at 490 nm by a Tecan plate reader. Data was analysed using One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Neuron Differentiation

Based on slight modifications of methods previously reported by Uras et al. [

40], SH-SY5Y cells were differentiated using the established three-stage protocol and then challenged with GA to generate the GA-induced neuronal model. Specifically, SH-SY5Y cells were diluted to 1.5 × 10

5 cells/ml, and 2 ml of the suspension were seeded into 35 mm petri dishes. After 2 days, the medium was replaced with differentiation medium #1 and subsequently changed every 48 h for 5 days. After that, the cells were cultured in differentiation medium #2 for 2 days. Cells were then detached and seeded onto extracellular matrix (ECM) coated dishes. For ECM coating, the ECM solution was diluted 1:100 in cold DMEM, and 2 ml of the mixture was added to each 35 mm dish. After overnight incubation, the solution was aspirated and the dishes were air-dried. One day after seeding on ECM coated dishes, the medium was replaced with differentiation medium #3 and then changed every 3 days to maintain neuronal health. Neurons were treated either with 0.7 mM GA alone or with GA plus 100 nM ASO delivered using Lipofectamine 2000, and incubated for 72 hours.

4.1. 2D Immunofluorescence Staining, Imaging, and Neurite Analysis

Glass coverslips were coated with poly-L-lysine for 1 hour at room temperature, rinsed three times with sterile water then dried completely. SH-SY5Y cells were seeded on a glass-based dish for differentiation. Before fixation, cells were rinsed briefly in PBS-T and were fixed in 4% PFA for 10 min at room temperature. Samples were washed three times with PBS-T and blocked with 1% BSA for 30 min. After blocking, samples were incubated overnight at 4 °C with Alexa Fluor® 488 (ab195879), washed three times in PBS-T. Samples were subsequently stained with DAPI for 15 min then washed three times in PBS-T. The samples were imaged by Axio Observer Z1/7 Confocal Microscope. Z-stack images were acquired covering a distance of 138 μm. NeuronJ plug in after background subtraction, with distinct colours assigned to individual traces. Neurite lengths were quantified with the Measure tracing function, and results were analysed by ANOVA.

Liposome Preparation

The liposomes were prepared by the thin-film hydration method. DSPC, CHOL, DSPE-PEG(2000) and DSPE-PEG(2000)-COOH (Avanti Polar Lipids, Birmingham, UK) were dissolved in chloroform (Thermo Fisher) with a molar ratio of 2:1:0.11:0.021, then the solution was evaporated at 35 ℃ under the vacuum condition to remove the organic solvent until the thin film formed. Residual chloroform residue was further removed by overnight incubation in a vacuum desiccator at room temperature. The thin-film was then hydrated with 4 ml of PBS with Cyanine3-MAPT-ASO (Cy3-MAPT-ASO). The suspension was vortexed and sonicated (40 kHz 25 ℃, Allendale Ultrasonics, UK) at room temperature for 10 minutes to prepare liposomes containing ASO and followed by extrusion 21 times through a 100 nm polycarbonate membrane to reduce particle size. Free Cy3-MAPT-ASOs were separated from liposomes by dialysis through 10,000 molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) SnakeSkin™ Dialysis Tubing (Thermo Fisher). After the MAPT-ASO loaded liposome was prepared, it was activated by 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC·HCl) and N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide (sulfo-NHS, Thermo Fisher) for 15 min at room temperature at pH 5.5. TF was added into the active liposome solution and incubated overnight at 4 ℃ at pH 7.5. Free TF was separated from TF-ASO-liposome by dialysis through 300,000 MWCO Spectra/Por® Dialysis Membrane (Cole-Parmer, Cambridgeshire, UK).

Particle Size Determination and Morphology Observation of Liposomes

The Zetasizer Nano (Malvern Instruments Ltd., Worcestershire, UK) was used to characterize the particle size and zeta-potential of the liposomes. The morphology of the liposome was determined by cryogenic transmission electron microscopy (JEM 2100+, JEOL, Japan).

Determination of Encapsulation Efficiency and Conjugation of Transferrin

The fluorescence intensity of Cy3-MAPT-ASO was used to prepare a calibration curve. After dialysis, the fluorescence intensity of samples was determined via Plate Reader (Tecan, Switzerland), the Cy3 excitation spectrum was obtained at 585 nm emission, and the emission spectrum was obtained at 540 nm excitation, gain was 100. The encapsulation efficiency, expressed as entrapment percentage, was calculated through the following relationship (1):

Where CA is the MAPT-ASO concentration in dialysed liposomes, and CAt is the MAPT-ASO concentration initially introduced.

Total TF (Thermo Fisher) input was normalized to 100%. A TF calibration curve was generated from serial dilutions of TF, each standard was mixed 1:1 with liposomes and processed identically to samples. Liposomes and TF were served as control groups. Equal volumes were resolved by SDS–PAGE on the same gel, followed by Coomassie staining. Band intensity of TF was quantified in ImageJ and fitted to the TF calibration curve. The TF grafting yield on liposomes was calculated from the calibrated TF amount relative to the 100% input.

Stability Study

The stability of liposomes and TF-liposomes was evaluated after storage at 4 ℃ for 14 days. Particle size was determined by ZetaSizer Nano with DTS1070 folded capillary zeta cell. Results were then processed using one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). Ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test was used to compare size differences between samples at different time points (Day 7 and Day 14, respectively).

Microfluidic Device Making

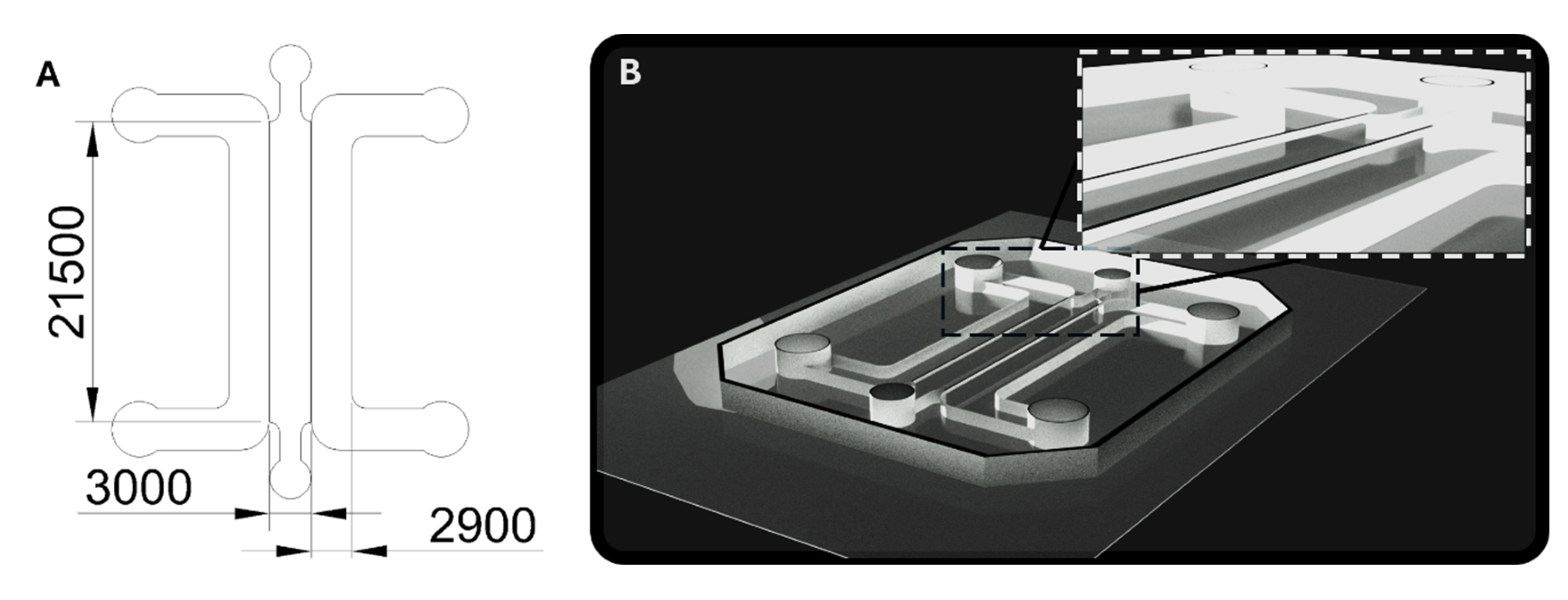

Soft lithography techniques were applied to fabricate microfluidic devices made from polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS, Sylgard 184 Silicone Elastomer Kit Dow, Dow, Cheadle, UK). An acrylic mold, 1000 µm thick, was laser-cut based on a design (see

Figure A2A) created in AutoCAD (version 2025.0.1, Autodesk, San Francisco, CA, USA), and subsequently affixed to an acrylic base. PDMS was prepared by combining the base elastomer with its curing agent in a 10:1 ratio, following the manufacturer’s guidelines. The resulting mixture was degassed for 30 minutes in a desiccator to eliminate trapped air. After degassing, the PDMS was poured into the molds to a depth of 8 mm and cured in an oven at 80 °C for 1.5 hours. Once cured, the PDMS structures were extracted from the molds, and 2 mm and 1.5 mm diameter inlet and outlet ports were created for the medium and hydrogel channels, respectively, using a biopsy puncher. The PDMS components were then soaked in deionized water and sterilized via autoclaving. After drying overnight at 80 °C, the PDMS chips were bonded to #1 glass coverslips using a Corona plasma treatment system (Elveflow, Paris, France). Before device seeding, hydrophobicity was restored by placing the microfluidic chips at 80 °C for at least 4 hours.

2D Cell Culture of BMECs, Astrocytes and Pericytes

Cells were maintained in a humidified incubator (37 °C, 5% CO2). Green fluorescent protein (GFP) labelled human brain microvascular cells (BMECs) (AngioProteomie, Boston, MA, USA; #cAP-0002GFP, Lot: 2022062302) were cultured in VascuLife vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) medium (Lifeline Cell Technology, Frederick, MD, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Cells were expanded in human fibronectin-coated (3 µg/cm2, Life Technologies) flasks and media was changed every other day. Cells were passaged using TrypLE Express (Life Technologies) and used at passage 2-4 for experiments.

Primary human brain vascular pericytes (ScienCell; Carlsbad, CA, USA; Cat#1200, Lot: 33155) and human brain astrocytes (ScienCell; #1800, Lot: 34727) were cultured as recommended by the manufacturer. Pericytes and astrocytes were expanded using pericyte medium (ScienCell, #1201) and astrocyte medium (ScienCell) in flasks coated with poly-L-lysine (2 μg/cm2, ScienCell). Cells were used at passages 2 or 3 for experiments and detached using 0.05% trypsin/EDTA (ScienCell).

BBB MVN Model Establishment

To establish the 3D microvascular BBB in vitro model, cells were incorporated into a fibrin hydrogel consisting of fibrinogen and thrombin, as described previously [

36]. 6 mg/ml bovine fibrinogen (Merck Life Science, Gillingham, UK) was prepared in PBS (calcium/magnesium free, Life Technologies) by incubation for 2 hours at 37 °C, followed by filtration through a 0.2 μm filter. Thrombin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was initially prepared at a concentration of 100 U/ml by dissolving 1 KU thrombin powder in 10 ml PBS (calcium/magnesium free), followed by a 1:25 dilution in Vasculife VEGF endothelial medium prepared with 0.1875 U/mL heparin and 2% FBS. Thrombin and fibrinogen solutions were prepared under sterile conditions and kept on ice during all procedures.

hBMECs, astrocytes and pericytes were detached, centrifuged, and resuspended in culture media to be counted. Cells were spun down again separately and resuspended in thrombin and then combined. The thrombin-cell mixture was mixed in equal parts with fibrinogen to form the fibrin hydrogel. Cells were seeded within the fibrin hydrogel at a final concentration of 20 million cells/ml, 1.5 million cells/ml and 3 million cells/ml for BMECs, pericytes and astrocytes, respectively. The fibrin-cell mixture was immediately injected into the central channel of the microfluidic device. Seeded devices were placed in a sterile humidified petri dish and fibrin was allowed to polymerize for 30 min within an incubator (37 °C, 5% CO2). Finally, Vasculife VEGF endothelial medium prepared with 0.1875 U/mL heparin and 2% FBS was added to the media channels. Media was changed every day in the devices.

To prevent liposomes from freely diffusing into the hydrogel without entering the MVN first, a monolayer of HBMECs was seeded along the gel interface at day 5 of device culture. To improve cell attachment, media channels were emptied and coated with human fibronectin diluted in culture media (0.03 mg/mL, Life Technologies) for 10 min. BMECs were detached and seeded into one media channel at a concentration of 1.5 million cells/ml in device culture media. The device was tilted 45° for 10 min to improve monolayer formation along the gel via gravity. Subsequently, the same was done for the opposing media channel.

3D Immunofluorescence Staining & Imaging

At day 7 of BBB MVN culture, immunofluorescence staining was performed, in a similar fashion as described previously [

36]. Briefly, media was removed and devices were washed and then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA; Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA, USA) overnight at room temperature (RT). Subsequently, devices were washed 3 times for 5 minutes with PBS at RT. Cell membranes were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS for 20 min at RT, followed by blocking in 0.1% normal goat serum (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) prepared in 0.1% Triton X-100 for 1.5 hours at RT. Immunostaining was performed using a primary antibody against glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP; #ab33922, Abcam) diluted 1:100 in the blocking buffer and incubated for 24 hours at 4 °C. Devices were washed 3 times for 5 minutes. Subsequently, secondary antibodies (anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 647; ##4414, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA) were diluted in PBS and applied for 2 hours at RT. For visualization of filamentous actin, samples were incubated with phalloidin probes (165 nmol; #A12381, Invitrogen) for 20 min at RT. Nuclear staining was performed with DAPI (1:1000; Sigma-Aldrich) for 15 min. Finally, samples were washed again with PBS (3 times, 5 min each at RT) before imaging on an inverted confocal microscope (BC43, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Liposome Perfusion Across the BBB MVNs

6 days after BBB microfluidic devices were seeded, TF-functionalized liposomes and non-functionalized liposomes were perfused through the MVNs at a concentration of 30 μg/ml. All liposomes were freshly prepared before each experiment and vortexed for 10 s before their use. For liposome perfusion, all media was removed and on one side, the filled media channel (~100 μl) was replaced with 80 μl. Then pipette tips, with the ends cut to fit tightly, were inserted into the openings of the media channels. On the side where no media was present, 250 μl of liposome solution was added to one tip. This setup allowed liposomes to flow across the media channel (similarly to arterial flow) but also into the MVNs (capillary flow) due to the hydrostatic pressure difference between the two media channels.

Liposome Permeability Measurements and Quantifications

30 min after liposomes were perfused into the microvasculature, z-stacks of a region of interest (ROI) (1223 μm x 1583 μm) in the central part of the gel channel were taken by confocal microscopy (BC43, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Z-stacks covered the whole depth of the microvasculature. The same procedure was performed again 24 hours later with the same imaging settings.

To quantify whether liposomes travelled outside the microvasculature, a FIJI [

41] macro was applied to each of the z-stacks (

Figure 4A) [

42]. In summary, the binary mask of the vasculature was used to either quantify the signal intensity of liposomes within this outline or outside of this outline to obtain information about the mean fluorescent signal intensity inside or outside the vasculature, respectively [

42]. Mean signal intensity for each z-slice was then averaged across the z-stack to obtain overall intensity values. Because the analysis was performed using an automated macro, all measurements were effectively blinded to experimental conditions. Raw measurements from TF-liposomes were normalized to the control measurement for each measurement day to prevent day-to-day variability in microscope imaging intensity, using the Formula (2) below:

To further understand kinetics of liposomes exiting the microvasculature, the intensity profile across a vessel and the surrounding 100 μm was assessed. For this, confocal z-stacks were combined via average intensity projections. Manually and in a blinded fashion, the intensity of GFP and Cy3 signal was then measured across a set distance by applying the ‘Line’ and ‘Plot profile’ functions in FIJI [

41]. To determine the borders of the microvasculature, the intensity profile from GFP expressed at the microvasculature was inspected in Origin Pro (version 2024b, OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA) and its ‘Level Crossing’ application (

Figure 3C). From this, the intensity of fluorescence from the Cy3-ASOs was then plotted along the 100 μm adjacent to the microvasculature, normalized to intensity within the lumens, and corrected by subtracting background noise. The intensity profile of at least 50 evenly distributed measurements across 3 biological replicates was averaged.

Liposome Toxicity Assessment via Microvasculature Network Analysis

Following the same workflow in Origin Pro as described in the previous section, vessel size was measured by determining the borders of the microvasculature via the intensity profile from the GFP expressed at the microvasculature. Vessel sizes were compared between different experimental conditions.

Statistics

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 10, GraphPad Software, Boston, Massachusetts USA) or Origin Pro software. The ANOVA test is used to compare the differences between three or more groups of normally distributed samples. Results with a P-value <0.05 were considered as significant. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; ****P<0.0001. n indicates the number of independent experiments performed for the same procedure.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K., X.S., Z.Z. and E.M.; methodology, S.K., X.S., Z.Z. and E.M.; software, S.K. and X.S.; validation, S.K. and X.S.; formal analysis, S.K. and X.S.; investigation, S.K. and X.S.; resources, Z.Z. and E.M.; data curation, S.K. and X.S.; writing—original draft preparation, , S.K. and X.S.; writing—review and editing, G.M., G.S.W., Z.Z. and E.M.; visualization, S.K. and X.S.; supervision, G.M., G.S.W., Z.Z. and E.M.; project administration, Z.Z. and E.M.; funding acquisition, Z.Z. and E.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.