Submitted:

16 October 2025

Posted:

17 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Methodological Approach

2. Literature Review

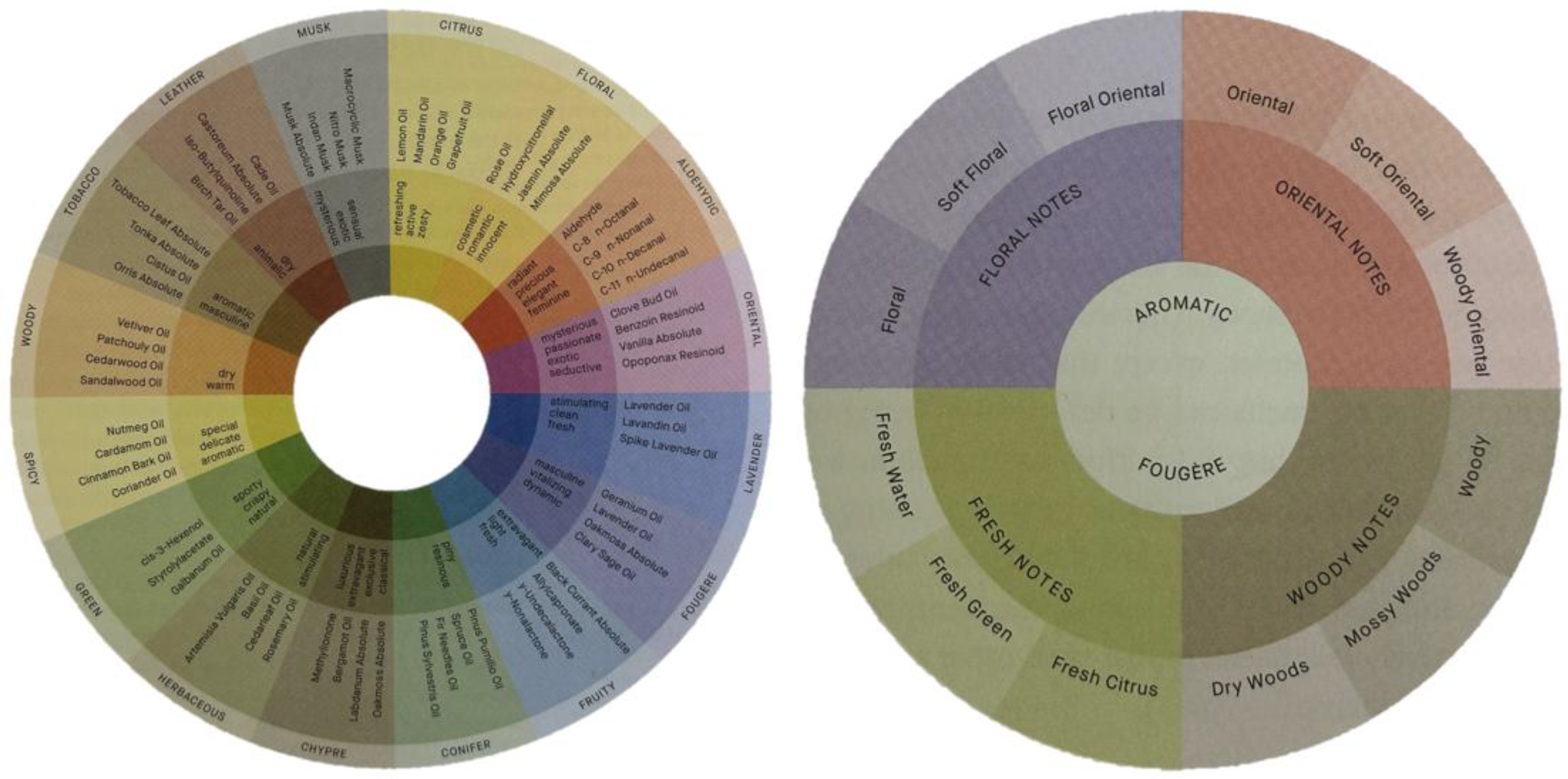

2.1. Historical Evolution of Olfactory Classifications

2.2. Semiotic Approaches for Structuring Sensory Meaning

2.3. Crossmodal Correspondences Between Odor and Color

3. Empirical Foundation: Interviews and Case Study

3.1. Semi-Structured Interviews: Academia and Industry

3.2. Case Study: EveryHuman’s Algorithmic Perfumery

4. Results

4.1. Construction of the OAC

4.2. Application of the OAC

4.2.1. Investigate

4.2.2. Attribute

4.2.3. Designate

4.2.4. Test

5. Discussion

7. Conclusion

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CMF | Color, Material and Finish |

| GPT | Generative Pre-trained Transformer |

| NCS | Natural Colour System |

| OAC | Olfactory Attribution Circle |

| RGB | Red, Green and Blue |

| SME | Small and Medium Enterprise |

Appendix A

| nº | Question |

|---|---|

| 1 | Could you tell me a bit about your professional or academic background and your involvement in research or work that, in some way, considers the sensory aspects of spaces and products and their perceptual effects on people? |

| 2 | How do you see the role of sensory stimuli, with a focus on olfactory stimuli, in experience design within built environments, such as retail spaces and exhibition spaces? What do you think are the benefits that solutions involving olfactory stimuli can bring to both people and businesses? |

| 3 | Which senses do you consider to be most explored in sensory design nowadays? Are there any, in your opinion, that are still underutilized? |

| 4 | Could you share examples of innovative solutions for each of the senses in physical environments? |

| 5 | Which companies or initiatives do you know that stand out for creating solutions for commercial and exhibition spaces? |

| 6 | What new technologies do you believe have the greatest potential to transform the field of olfactory design in built environments? |

| 7 | How can regenerative and sustainable design practices be integrated into the development of olfactory solutions in built environments? What precautions should professionals take to ensure that the solutions adopted are aware? |

| 8 | What are the main methodological challenges that arise when implementing effective olfactory design strategies in SMEs? |

| 9 | Is there a recommended approach or methodology for defining and selecting olfactory solutions to be adopted in a project? What would be the first step in this process? |

| 10 | How do you see the future of Sensory Branding and Experience Design in built environments in the coming years? |

| nº | Question |

|---|---|

| 1 | Could you tell me a bit about the history of the company and how it started getting involved in the development of olfactory solutions for people or built environments? |

| 2 | What are the main challenges faced in integrating olfactory solutions into different types of spaces and sectors? |

| 3 | How does the company develop olfactory solutions? What technologies and methodologies do you use? |

| 4 | Does the company collaborate with designers, architects, and marketing professionals to implement olfactory solutions? |

| 5 | What are the main emerging trends and innovations in the field of sensory experiences? |

| 6 | What benefits does the integration of your olfactory solutions offer to the user? Is there a process to measure the impact (effectiveness) of these benefits? |

| 7 | Does the company integrate sustainable and regenerative practices in the development of olfactory solutions? Which ones? |

| 8 | Does the company customize olfactory solutions for different types of brands and people? Is there a process that guides this customization? |

| 9 | How do you see the adoption of olfactory experiences by SMEs (small and medium enterprises)? What do you think are the main obstacles in implementing sensory solutions for SMEs? |

| 10 | Is there a possibility of making customized olfactory solutions more accessible and scalable for SMEs? What kind of tools or resources would be necessary? |

Appendix B

|

Appendix C

References

- Malnar, J. M.; Vodvarka, F. Sensory design; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pallasmaa, J. The eyes of the skin: architecture and the senses; Wiley: Hoboken, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zumthor, P. Atmospheres: architectural environments - surrounding objects; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Krishna, A. (Ed.) Sensory marketing: research on the sensuality of products; Routledge: Oxfordshire, United Kingdom, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Krishna, A. An integrative review of sensory marketing: Engaging the senses to affect perception, judgment and behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 2012, 22, 332–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hekkert, P. Design aesthetics: Principles of pleasure in design. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 48, 157–172. [Google Scholar]

- Velasco, C.; Spence, C. (Eds.) Multisensory packaging: Designing new product experiences; Palgrave Macmillan: London, United Kingdom, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, C. Olfactory-colour crossmodal correspondences in art, science, and design. Cogn. Res. Princ. Implic. 2020, 5, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, C. Senses of place: architectural design for the multisensory mind. Cogn. Res. Princ. Implic. 2020, 5, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Imschloss, M.; Adler, S. Scent. In Multisensory Design of Retail Environments: Vision, Sound, and Scent, 2nd ed.; Publisher: Springer Wiesbaden, Wiesbaden, Germany, 2024; pp. 53–71. [Google Scholar]

- Haverkamp, M. Synesthetic design: handbook for a multisensory approach; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Engen, T. The perception of odors; Academic Press: Oxford, United Kingdom, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, J.; Aletta, F.; Radicchi, A. Editorial: smells, well-being, and the built environment. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herz, R.S. The role of odor-evoked memory in psychological and physiological health. Brain Sci. 2016, 6, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boden, M. A. AI: Its nature and future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, United Kingdom, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- McCormack, J.; Gifford, T.; Hutchings, P. Autonomy, authenticity, authorship and intention in computer generated art. In Computational Intelligence in Music, Sound, Art and Design; Ekárt, A., Liapis, A., Castro Pena, M.L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; vol. 11453, pp. 35–50. [Google Scholar]

- Shneiderman, B. Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence: Three Fresh Ideas. AIS Trans. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2020, 12, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shneiderman, B. Human-centered artificial intelligence: Reliable, safe & trustworthy. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2020, 36, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candy, L.; Edmonds, E. Practice-based research in the creative arts: foundations and futures from the front line. Leonardo 2018, 51, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantosalo, A.; Toivonen, H. Modes for creative human-computer collaboration: Alternating and task-divided co-creativity. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Computational Creativity (ICCC 2016), Paris, France, 27 June–1 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Henshaw, V. , McLean, K., Medway, D., Perkins, C., & Warnaby, G. (Eds.). Designing with smell: practices, techniques and challenges; Routledge: Oxfordshire, United Kingdom, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Barbara, A.; Mikhail, R.A.A. The Odor of Colors: Correspondence from a Cross-Cultural Design Perspective. In Proceedings of the International Colour Association (AIC) Conference 2021, Milan, Italy, 30 August–3 September 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Deroy, O.; Spence, C. Crossmodal correspondences: Four challenges. Multisens. Res. 2016, 29, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spence, C. Using ambient scent to enhance well-being in the multisensory built environment. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvale, S., & Brinkmann, S. (2009). InterViews: Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Yin, R. K. Case study research and applications: design and methods, 6th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Martone, G. La grammatica dei profumi; Gribaudo: Milan, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K. Triangulation 2.0. J. Mixed Methods Res. 2012, 6, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howes, D. (Ed.) Empire of the senses: the sensual culture reader; Berg: Oxford, United Kingdom, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lupton, E. , & Lipps, A. (Eds.). The senses: design beyond vision; Princeton Architectural Press: New York, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Piesse, G. W. S. The art of perfumery: And methods of obtaining the odors of plants; Lindsay & Blakiston: Philadelphia, USA, 1857. [Google Scholar]

- Jellinek, P. Die psychologischen grundlagen der parfümerie; Hüthig: Heidelberg, Germany, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Henning, H. Der geruch; Johann Ambrosius Barth: Leipzig, Germany, 1916. [Google Scholar]

- McLean, K. Communicating and mediating smellscapes: The design and exposition of olfactory mappings. In Designing with Smell: Practices, Techniques and Challenges; Henshaw, V., McLean, K., Medway, D., Perkins, C., Warnaby, G., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 67–77. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff, K. The semantic turn: a new foundation for design; CRC Press: Boca Raton, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, K.W.; Lenau, T.; Ashby, M.F. The Aesthetic and Attributes of Products. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Engineering Design (ICED ’03), Stockholm, Sweden, 19–21 August 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Classen, C.; Howes, D.; Synnott, A. Aroma: the cultural history of smell; Routledge: Oxfordshire, United Kingdom, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Pastorelli, O. Le parole del profumo., 2nd ed.; Tecniche Nuove: Milan, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pastorelli, O.; Levi, S. Leggere il profumo; Tecniche Nuove: Milan, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, C.T. dos. Requisitos de Linguagem do Produto: Uma Proposta de Estruturação para as Fases Iniciais do PDP. Doctoral Thesis, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, Brazil, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Santaella, L. Semiotica Aplicada; Cengage: São Paulo, Brazil, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Eco, U. A Theory of semiotics; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Barthes, R. Elements of semiology; (A. Lavers & C. Smith, Trans.); Hill and Wang: New York, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Pastoureau, M. Noir: Histoire d’une couleur; Seuil: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gage, J. Color and meaning: Art, science, and symbolism; University of California Press: Oakland, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Heller, E. Psychology of color: effects and symbolism, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, A. The beginner’s guide to colour psychology; Kyle Cathie Ltd: London, United Kingdom, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, S. Color Image Scale; Kodansha International: Tokyo, Japan, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Albers, J. Interaction of color; Yale University Press: New Haven, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Desmet, P.M.A.; Hekkert, P. Framework of product experience. Int. J. Des. 2007, 1, 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Boeri, C. An educational experience on the exploration and experimentation of colour associations and relationships. J. Int. Colour Assoc. 2019, 24, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Boeri, C. Color and the emotional character of interiors. In Proceedings of the First Russian Congress on Color, Smolensk, Russia, 18–20 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, A.N.; Martin, R.; Kemp, S.E. Cross-modal correspondence between vision and olfaction: the color of smells. Am. J. Psychol. 1996, 109, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, A. N. What the nose knows: the science of scent in everyday life; Crown: New York, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp, S.E.; Gilbert, A.N. Odor intensity and color lightness are correlated sensory dimensions. Am. J. Psychol. 1997, 110, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrot, G.; Brochet, F.; Dubourdieu, D. The color of odors. Brain Lang. 2001, 79, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schifferstein, H. N. J., & Tanudjaja, I. (2004). Visualising fragrances through colours: The mediating role of emotions. Perception, 33(10), 1249–1266. [CrossRef]

- Demattè, M.L.; Sanabria, D.; Spence, C. Cross-modal associations between odors and colors. Chem. Senses 2006, 31, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevenson, R.J.; Prescott, J.; Boakes, R.A. Confusing tastes and smells: how odours can influence the perception of sweet and sour tastes. Chem. Senses 1999, 24, 627–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herz, R. S. The scent of desire: discovering our enigmatic sense of smell; HarperCollins: New York, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Herz, R.S. A naturalistic analysis of autobiographical memories triggered by olfactory, visual and auditory stimuli. Chem. Senses 2009, 29, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herz, R.S.; Eliassen, J.; Beland, S.; Souza, T. Neuroimaging evidence for the emotional potency of odor-evoked memory. Neuropsychologia 2004, 42, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levitan, C.A.; et al. Cross-cultural color-odor associations. PLoS One 2014, 9, e101651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, C. Crossmodal correspondences: A tutorial review. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 2011, 73, 971–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camgöz, N.; Yener, C.; Güvenç, D. Effects of hue, saturation, and brightness on preference. Color Res. Appl. 2002, 27, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurlbert, A.C.; Ling, Y. Biological components of sex differences in colour preference. Curr. Biol. 2007, 17, R623–R625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Österbauer, R.A.; Matthews, P.M.; Jenkinson, M.; Beckmann, C.F.; Hansen, P.C.; Calvert, G.A. Color of scents: Chromatic stimuli modulate odor responses in the human brain. J. Neurophysiol. 2005, 93, 3434–3441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevenson, R.J.; Rich, A.; Russell, A. The nature and origin of cross-modal associations to odours. Perception 2012, 41, 606–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, R.J.; Oaten, M. The effect of appropriate and inappropriate stimulus color on odor discrimination. Percept. Psychophys. 2008, 70, 640–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; et al. Olfactory modulation of colour working memory: How does citrus-like smell influence the memory of orange colour? PLoS One 2018, 13, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellner, D.A. Color–odor interactions: a review and model. Chemosens. Percept. 2013, 6, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellner, D.A.; Whitten, L.A. The effect of color intensity and appropriateness on color-induced odor enhancement. Am. J. Psychol. 1999, 112, 585–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zellner, D.A.; Kautz, M.A.; Hall, S.; Durlach, P. Influence of color on odor identification and liking ratings. Am. J. Psychol. 1991, 104, 547–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottfried, J.A.; Dolan, R.J. The nose smells what the eye sees: Crossmodal visual facilitation of human olfactory perception. Neuron 2003, 39, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozota, B. Design management: using design to build brand value and corporate innovation. Allworth Press: New York, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, D. A. Emotional design: why we love (or hate) everyday things; Basic Books: New York, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Böhme, G. Atmosphäre: essays zur neuen Ästhetik; Suhrkamp: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Merleau-Ponty, M. Phénoménologie de la perception. Gallimard: Paris, France, 1945. [Google Scholar]

| Phase | Method | Output | Purpose/Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Systematic literature review | Theoretical foundation, identification of validated attributes | Reveal research gap and conceptual grounding |

| 2 | Semi-structured interviews |

Practice-based insights | Identify inclusion, intensity and feasibility concerns |

| 3 | Case study – EveryHuman |

Observation evidence of AI-mediated olfactory personalization | Evaluate potential and limits of AI in olfactory design |

| 4 | AI-assisted exploration |

Mapping of essences- attributes-colors |

Generate crossmodal correspondences |

| 5 | Analytical cross- comparison |

Olfactory Attribution Circle (OAC) | Triangulate findings and refine tool |

| Theme | Key Insight |

|---|---|

| Materials | Intrinsic odors of materials shape atmospheres. |

| Inclusivity | Semantic attributes preferred over gendered/age-based categories. |

| Feasibility & SMEs | Barriers include cost and lack of design culture; need approaches and affordable technologies. |

| Intensity | Balance is critical: avoid overstimulation or imperceptibility. |

| AI Role | Potential for exploration vs. skepticism on cultural nuance. |

| Strategic Potential | Olfactory design as memory, identity, and differentiation tool. |

| Sustainability | Refill, reuse, authenticity, and crafted imperfection as sensorial values. |

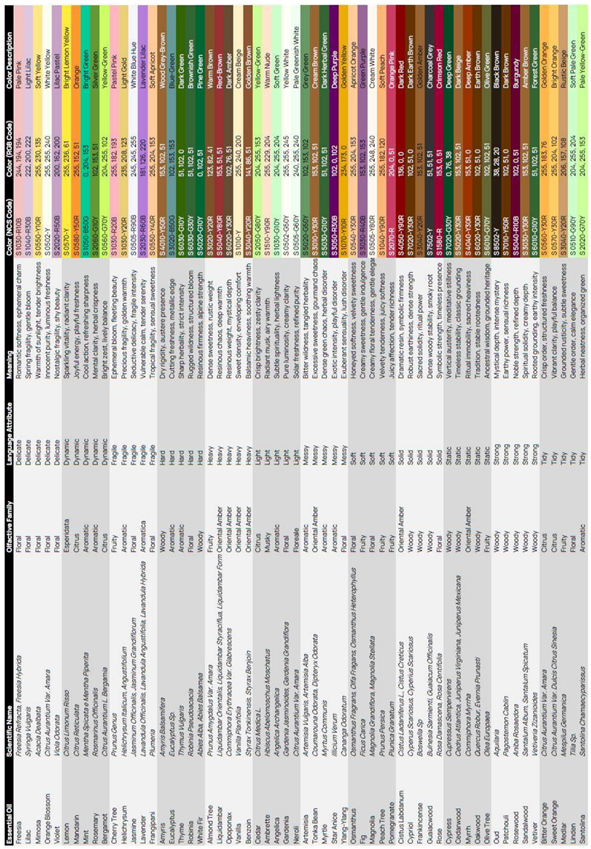

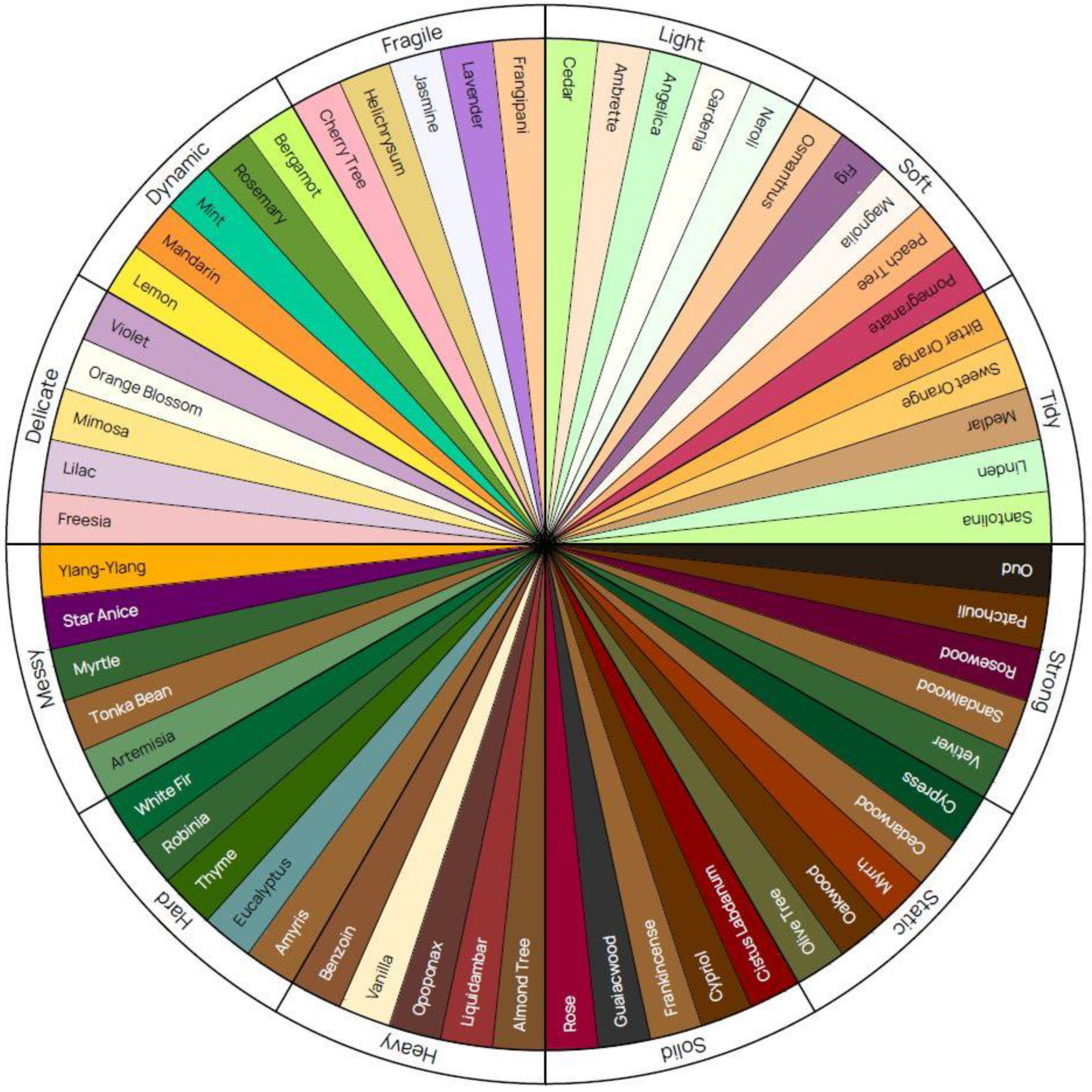

| Step | Action | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Provide AI with dataset of 60 essences (common names, scientific names, olfactory families). | Ground the system in reliable taxonomy. |

| 2 | Introduce the 12 bipolar attributes and instruct AI to distribute essences equally (5 per attribute). | Create balance across the semantic approach. |

| 3 | Analyze outputs: resolve duplications (e.g., Rose allocated to both Solid and Soft; Pomegranate in Soft and Messy). Iterative refinement applied. | Ensure semantic clarity and uniqueness. |

| 4 | Request AI to associate each essence with a color (initially in NCS, later converted into RGB for digital applications). | Establish crossmodal correspondences aligned with chromatic coding. |

| 5 | Evaluate AI results for semantic coherence and cultural resonance; manually refine inconsistencies. | Guarantee conceptual and aesthetic accuracy. |

| 6 | Attempt to generate visual diagram (circle segmented into 12 equal parts, each with attribute, essences, and colors). | Test AI’s capacity for visual representation. |

| 7 | Recognize limitations: AI was unable to segment the circle evenly or apply color codes consistently. | Identify scope and boundaries of AI assistance. |

| 8 | Author creates final consultation table and visual OAC diagram based on AI descriptions | Assert authorship and ensure usability. |

| Phase | Key Question | Main Actions | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Investigate | What atmosphere and identity are desired? | Ethnography, observation, user insights | Cultural and sensory identity map |

| Attribute | How is identity linguistically expressed? | Workshops, word clustering, OAC mapping |

Selection of bipolar attributes |

| Designate | How can identity be materialized? | Olfactory composition, color palette, material selection |

Sensory design strategy |

| Test | Does the experience communicate the intended identity? | User evaluation, affective measures |

Validation and refinement |

| Dimension | Empirical Evidence (Literature) |

Phenomenological Interpretation |

Design Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Odor-Color | Schifferstein & Tanudjaja (2004); Velasco et al. (2015) | Congruent hues reinforce perceptual clarity | Harmonize chromatic and olfactory values |

| Odor-Language | Krippendorf (2006); Boeri (2019) | Semantic attributes shape sensory meaning | Use bipolar descriptors for inclusivity |

| Odor-Memory | Herz (2016); Spence (2020) | Scents evoke embodied recall | Design for emotional resonance |

| Overall Congruence | Merleau-Ponty (1945); Böhme (1993) | Embodied unity and aesthetic coherence | Design atmospheres as unified fields |

| Outcome | Description |

| Structured Methodology | Proposes a four-phase process—Investigate, Attribute, Designate, Test. |

| Inclusive Semantic Attributes |

Avoids stereotyped divisions, promoting inclusivity and broad participation. |

| Systematic Congruence | Confirms consistent mapping across attributes, scents and colors. |

| AI: Creative Partner | Reveals AI possibilities and limitations as a creative partner for designers |

| Importance of Balance and Intensity |

Evidences the importance of calibrating intensity and diffusion when designing for Smell |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).