Submitted:

17 October 2025

Posted:

17 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Wildlife Tourism

1.2. Community-Based-Management

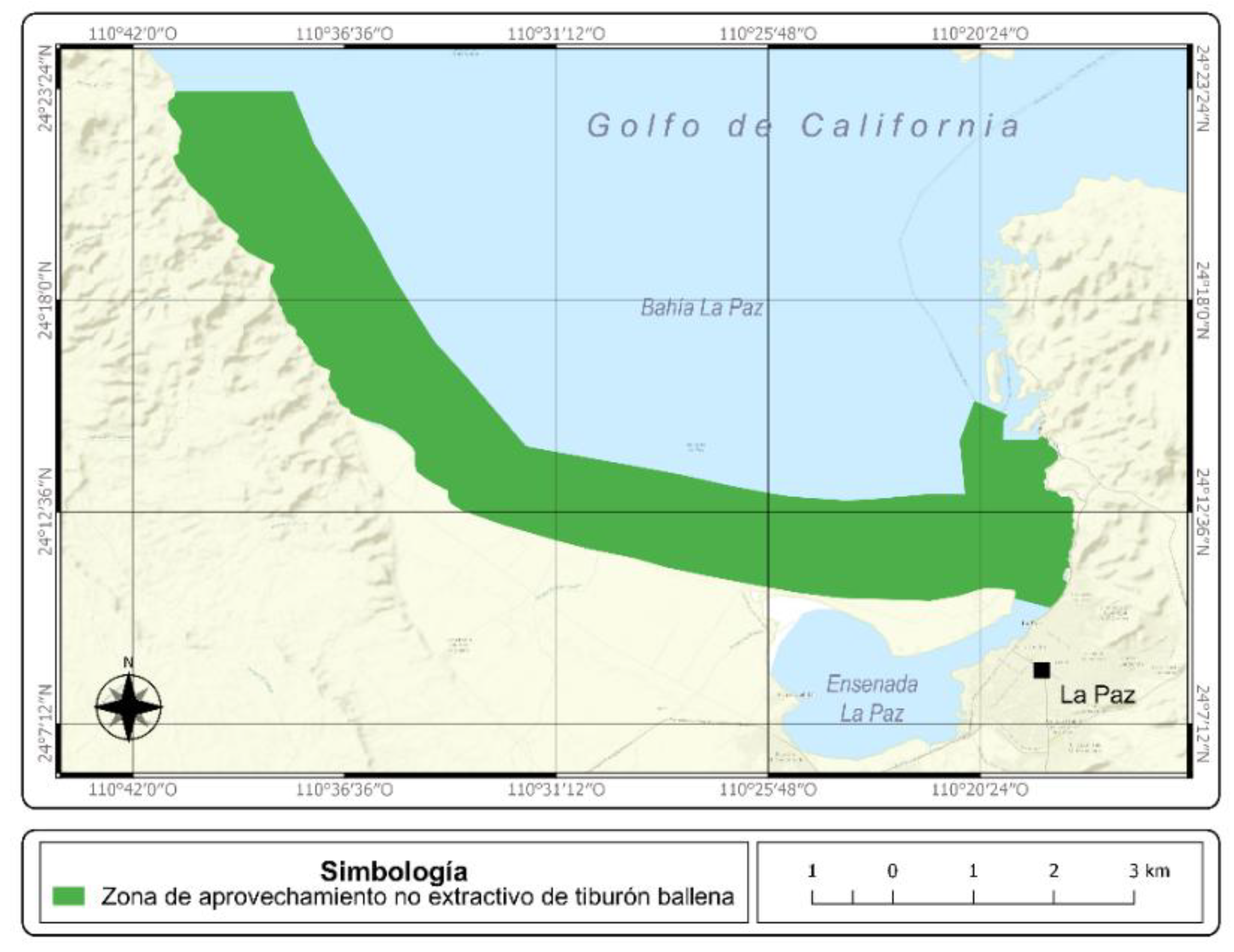

1.3. Whale Shark Wildlife Tourism in La Paz Bay, Mexico

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling

2.2. Travel Cost Method

2.3. Recreational Demand Estimation

3. Results

3.1. Data

3.2. Econometrics

| Variable | Description |

| V | Dependent, number of trips in the last 5 years, (V≥0) |

| dom | 1: If the visitor is domestic or local, 0: Other |

| alone | 1: If the visitor travels alone, 0: Other |

| lgroup | Natural logarithm for the number of tourists on board the boat, including the interviewee |

| sanct | 1: If the visitor agrees to inform citizens and visitors that the WS area is a natural sanctuary; 0: Other |

| gguide | 1: If the visitor considers that the guide had a good performance during the tour, 0: Other |

| rules | 1: If the visitor was informed about the rules to carry out the WS wildlife tourism activity; 0: Other |

| first | 1: If the visitor is visiting the WS area for the first time |

| consd | 1: If the visitor considers that the conservation status of the WS area is deficient, 0: Other |

| couple | 1: If the visitor visits the WS area with his couple/wife, 0: Other |

| Dependent: V | Poisson Model | |||

| TP | TPOME | TPTTC | TPTTCOME | |

| n=334 | n=334 | n=334 | n=334 | |

| ltp | -0.7198 | |||

| [0.1229]** | ||||

| ltpome | -0.2087 | |||

| [0.0391]** | ||||

| ltpttc | -0.6449 | |||

| [0.1230]** | ||||

| ltpttcome | -0.5804 | |||

| [0.1063]** | ||||

| dom | 0.3809 | 0.2588 | 0.3384 | 0.2296 |

| [0.0819]** | [0.0822]** | [0.0791]** | [0.0739]** | |

| alone | -0.7283 | -0.5016 | -0.7323 | -0.5566 |

| [0.1970]** | [0.1435]** | [0.1945]** | [0.1500]** | |

| group | -0.8575 | -0.7316 | -0.8428 | -0.7865 |

| [0.3175]** | [0.3165]* | [0.3201]** | [0.3163]* | |

| sanct | -0.6054 | -0.4869 | -0.5753 | -0.5268 |

| [0.0894]** | [0.0858]** | [0.0890]** | [0.0860]** | |

| gguide | 2.0483 | 2.3514 | 2.1046 | 2.2958 |

| [0.2075]** | [0.2002]** | [0.2041]** | [0.1929]** | |

| rules | 0.1672 | 0.1492 | 0.1632 | 0.1547 |

| [0.0524]** | [0.0696]* | [0.0570]** | [0.0624]* | |

| first | -1.0402 | -1.0732 | -1.0251 | -1.046 |

| [0.0631]** | [0.0637]** | [0.0640]** | [0.0637]** | |

| consd | 0.3212 | 0.3394 | 0.3243 | 0.3299 |

| [0.0841]** | [0.0849]** | [0.0848]** | [0.0842]** | |

| couple | -0.6101 | -0.5983 | -0.6131 | -0.6057 |

| [0.0903]** | [0.0824]** | [0.0867]** | [0.0842]** | |

| _cons | 3.0114 | 2.5788 | 3.0912 | 3.0205 |

| [0.4343]** | [0.3751]** | [0.4792]** | [0.4467]** | |

| Chi2 Wald (10) | 716.47 | 712.41 | 712.64 | 715.54 |

| Pr>Chi2 Wald (10) | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| Pearson R2 | 0.8422 | 0.8329 | 0.8390 | 0.8374 |

| Pseudo LL | -535.09301 | -543.5885 | -537.0061 | -542.02082 |

3.3. Willingness to Pay

| Concept | Poisson Model | Average | |||

| TP | TPOME | TPTTC | TPTTCOME | ||

| WTP | 8.00 | 27.00 | 9.00 | 10.00 | 13.50 |

| WS-REV | 304,600 | 1,028,025 | 342,675 | 380,750 | 514,013 |

| Upper value per WS | 4,173 | 14,083 | 4,694 | 5,216 | 7,041 |

| Average value per WS | 3,016 | 10,178 | 3,393 | 3,770 | 5,089 |

| Lower value per WS | 2,361 | 7,969 | 2,656 | 2,952 | 3,985 |

| Source: Author’s elaboration | |||||

4. Discussion

4.1. Environmental Valuation

4.2. Community-Based-Management

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Author(s)/ Year | Area/Site | Specie | US$* |

| Wilson & Tisdell, 2002 | South-Eastern Queensland, Australia | W ST |

17 189 043 509 666 |

| Enríquez et al., 2003 | Phuket Islands, Thailand | WS | 3 554 722 |

| Topelko & Dearden, 2005 | Belize | WS | 4 204 918 |

| Rowat & Engelhardt, 2007 | Seychelles | WS | 7 687 869 |

| Catlin et al., 2010 | Ningaloo, Australia | WS | 5 409 485 |

| Vianna et al., 2011 | Viti Levu, Fiji Islands | S | 4 626 350 |

| Du Preez et al., 2012 | Aliwal Shoal Marine Protected Area, South Africa |

S | 473 501 |

| Vianna et al., 2012 | Palau, Island | S | 25 672 131 |

| Cisneros-Montemayor et al., 2013 | Belize Mexico |

S S |

469 054 16 127 156 |

| Cagua et al., 2014 | South Ari, Maldive Islands | WS | 5 855 738 |

| Ruiz-Sakamoto, 2015 | Revillagigedo National Park, Mexico |

S | 8 377 049 |

| Schwoerer et al., 2016 | Eastern Pacific Coast Baja California Sur, Mexico | W | 281 185 |

| Huveneers et al., 2017 | Australia | S | 43 237 704 |

| Cisneros-Montemayor et al., 2019 | Mexico | S | 12 400 000 |

| Cisneros-Montemayor et al., 2020 | Baja California Sur, Mexico | SS | 47 000 000 |

| Oropeza-Cortés et al., 2023 | Laguna San Ignacio, Mexico | GW | 908 502 |

|

Source: Author’s elaboration Note: GW: grey whale, S: sharks, SS: several species, ST: sea turtles, W: whales, WS: whale shark *Direct expenditure in 2020 updated US$ | |||

References

- Armitage, D. 2005. Adaptive capacity and community-based natural resource management. Environmental Management 35:703–715, DOI: 10.1007/s00267-004-0076-z.

- Beal, D.J. 1995. Sources of variation in estimates of cost reported by respondents in travel cost surveys. Aust. J. Leis. Recreat., 5(1), pp. 3–8.

- Beckley, L.E., G. Cliff, M.J. Smale. & L.J.V. Compagno. 1997. Recent strandings and sightings of whale sharks in South Africa, Environmental Biology of Fishes 50 pp. 343–348.

- Bennett, NJ, Katz L, Yadao-Evans W, Ahmadia GN, Atkinson S, Ban NC, Dawson NM, de Vos A, Fitzpatrick J, Gill D, Imirizaldu M, Lewis N, Mangubhai S, Meth L, Muhl E-K, Obura D, Spalding AK, Villagomez A, Wagner D, White A and Wilhelm A. 2021. Advancing Social Equity in and Through Marine Conservation. Front. Mar. Sci. 8:711538. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.711538.

- Berkes, F. 2007. Community-based conservation in a globalized world. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(39), 15188-15193. [CrossRef]

- Brooks, J., Waylen, K.A. & Mulder, M.B. 2013. Assessing community-based conservation projects: A systematic review and multilevel analysis of attitudinal, behavioral, ecological, and economic outcomes. Environ Evid 2, 2. [CrossRef]

- Cagua, E.F., N. Collins, J. Hancock & R. Rees. 2014. Whale shark economics: a valuation of wildlife tourism in South Ari Atoll, Maldives. PeerJ, 2:e515, DOI 10.7717/peerj.515.

- Cameron C.A. & F.A. Windmeijer. 1997. An R-squared measure of goodness of fit for some common nonlinear regression models. Journal of Econometrics, 77(2), 329-342. [CrossRef]

- Cameron, AC & PK. Trivedi. 2007. Regression analysis of count data. 6th Ed., Econometric Society Monographs, Num. 30, Cambridge University Press, USA., p. 411.

- Cameron, C.A. & F.A. Windmeijer. 1996. R-Squared Measures for Count Data Regression Models with Applications to Health-Care Utilization. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics , Apr., 1996, Vol. 14, No. 2 (Apr., 1996), pp. 209-220. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1392433.

- Cárdenas-Torres, N., Enríquez-Andrade, R., & Rodríguez-Dowdell, N. 2007. Community-based management through ecotourism in Bahia de los Angeles, Mexico. Fisheries Research, 84(1), 114-118. [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas-Torres, N., R. Enríquez-Andrade & N. Rodríguez-Dowdell. 2005. Community-based management through ecotourism in Bahia de los Angeles, Mexico. The First International Whale Shark Conference: Promoting International Collaboration in Whale Shark Conservation, Science and Management, 9-12 May, Perth, Western Australia, p. 67.

- Carrillat, F. A., M. Mazodier & C. Eckert. 2024. Why advertisers should embrace event typicality and maximize leveraging of major events. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 52:1585–1607, . [CrossRef]

- Catlin J., R. Jones, T. Jones, B. Norman & D. Wood. 2010. Discovering wildlife tourism: a whale shark tourism case study, Current Issues in Tourism, 13:4, 351-361, DOI: 10.1080/13683500903019418.

- Chen, H.L., R.L. Lewinson, L. An, Y.H. Tsai, D. Stow, L. Shi & S. Yang. 2020. Assessing the effects of payments for ecosystem services programs on forest structure and species biodiversity. Biodiversity and Conservation, (29), pp. 2123–2140, DOI: . [CrossRef]

- Child, B. 1996. The practice and principles of community-based wildlife management in Zimbabwe: the CAMPFIRE programme. Biodivers Conserv 5, 369–398. [CrossRef]

- Christiersson, A. 2003. An Economic Valuation of the Coral Reefs at Phi Phi Island. A Travel Cost Approach. Tesis de maestría en Economía, Lulea University of Technology, p.55.

- Cisneros-Montemayor, A.M.A. Townsel, C.M. Gonzales, A.R. Haas, E.E. Navarro-Holm, T. Salorio-Zuñiga & A.F. Johnson. 2020. Nature-based marine tourism in the Gulf of California and Baja California Peninsula: Economic benefits and key species. Nat Resour Forum. 44:111–128.

- Cisneros-Montemayor, A.M., E.E. Becerril-García, O. Berdeja-Zavala & A. Ayala-Bocos. 2019. Shark ecotourism in Mexico: Scientific research, conservation, and contribution to a Blue Economy. Advances in Marine Biology, 85:1, pp. 71-92. [CrossRef]

- Cisneros-Montemayor, A.M., M. Barnes-Mauthe, D. Al-Abdulrazzak, E. Navarro-Holm & R. Sumaila. 2013. Global economic value of shark ecotourism: implications for conservation. Fauna & Flora International, Oryx, 47(3), pp. 381–388 doi:10.1017/S0030605312001718.

- Clark E. & D.R. Nelson. 1997. Young whale sharks, Rhincodon typus, feeding on a copepod bloom near La Paz, Mexico. Environmental Biology of Fishes 50: 63–73.

- Clawson, M. & L. Knetsch. 1996. Economics of Outdoor Recreation. Resource for the Future [RFF], (Ed.), 328 p.

- Cox, M., G. Arnold & S. Villamayor-Tomás. 2010. A review of design principles for community-based natural resource management. Ecology and Society 15(4): 38. [online] URL: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol15/iss4/art38/.

- Czajkowski, M., M. Giergiczny, J. Kronenberg & J. Englin. 2019. The Individual Travel Cost Method with Consumer-Specific Values of Travel Time Savings. Environmental and Resource Economics (2019) 74:961–984.

- De Silva-Dávila, R., & J.R. Palomares-García. 1998. Unusual larval growth production of Nyctiphanes simplex in Bahía de la Paz, Baja California Sur, Mexico, Journal of Crustacean Biology, 18, 490–498. [CrossRef]

- Dressler, W., Büscher, B., Schoon, M., Brockington, D., Hayes, T., Kull, C.A., J. McCarthy & Shrestha, K. 2010. From hope to crisis and back again? A critical history of the global CBNRM narrative. Environmental Conservation, 37(1), 5–15. doi:10.1017/S0376892910000044.

- Du Preez, M., M. Dicken & S.G. Hosking. 2012. The value of tiger shark diving within the Aliwal Shoal marine protected area: A travel cost analysis. South African Journal of Economics Vol. 80:3 September, pp. 387-399.

- Eckert, S.A. & B.S. Stewart. 2001. Telemetry and satellite tracking of whale sharks, Rhincodon typus, in the Sea of Cortez, Mexico, and the North Pacific Ocean. Environ. Biol. Fish. 60, pp. 299–308.

- Emerton, L. 2001. The nature of benefits and the benefits of nature: why wildlife conservation has not economically benefited communities in Africa. In African wildlife and livelihood: the promise and performance of community conservation. D. Hulme and M. Murphee (eds). London: James Curry, pp. 208-226.

- Esmail, N., McPherson, J. M., Abulu, L., Amend, T., Amit, R., Bhatia, S., Bikaba, D., Brichieri-Colombi, T. A., Brown, J., Buschman, V., Fabinyi, M., Farhadinia, M., Ghayoumi, R., Hay-Edie, T., Horigue, V., Jungblut, V., Jupiter, S., Keane, A., Macdonald, D.W., . . . Wintle, B. 2023. What’s on the horizon for community-based conservation? Emerging threats and opportunities. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 38(7), 666-680. [CrossRef]

- Forest Trends & The Katoomba Group. 2010. Payments for Ecosystem Services: Getting Started in Marine and Coastal Ecosystems: A Primer. Forest Trends, The Katoomba Group and UNEP (Eds.), p. 80.

- Graham, R.T. & Roberts, C.M. 2007. Assessing the size, growth rate, and structure of a seasonal population of whale sharks (Rhincodon typus Smith 1828) using conventional tagging and photo identification, Fisheries Research 84 pp.71–80.

- Greiber, T. 2009. Payment for Ecosystem Services. Legal and Institutional Framworks. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland, xvi+296 p.

- Grima, N., S.J. Singh, B. Smetschka & L. Ringhofer. 2016. Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES) in Latin America: Analysing the performance of 40 case studies. Ecosystem Services, 17, pp. 24-32. [CrossRef]

- Gruber, J.S. 2010. Key Principles of Community-Based Natural Resource Management: A Synthesis and Interpretation of Identified Effective Approaches for Managing the Commons. Environmental Management 45, 52–66. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, T., Chen, S. & Mohanty, S. 2025. More the merrier: Effects of plural brand names on perceived entitativity and brand attitude. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 35(1), 150-157. [CrossRef]

- Haab, T. & K. McConnell. 2002. Valuing Environmental and Natural Resources: The Econometrics of Non-Market Valuation. Edward Elgar Publishing (Ed.), p. 326.

- Hacohen-Domené A., F. Galván-Magaña & J. Ketchum-Mejia. 2006. Abundance of whale shark (Rhincodon typus) preferred prey species in the southern Gulf of California, Mexico. Cybium 2006, 30(4) suppl.: 99-102.

- Hanley, N., Shogren, J.F. & White, B., 2001. Introduction to Environmental Economics. Oxford University Press, New York, p. 368.

- Hellerstein, D. 1995. Welfare estimation using aggregate and individual observation models: a comparison using Monte Carlo techniques. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 77(3), pp. 620-630.

- Hernández-Trejo, V., J. Urciaga-García, M.A. Hernández-Vicent & L.O. Palos-Arocha. 2009. Valoración económica del Parque Nacional Bahía de Loreto a través de los servicios de recreación de pesca deportiva. Región y Sociedad, Vol. XXI, Núm. 44, enero-abril, pp. 195-223. http://redalyc.uaemex.mx/src/inicio/ArtPdfRed.jsp?iCve=10204408.

- Heyman, W.D., Graham, R.T., Kjerfve, B. & Johannes, R.E. 2001. Whale sharks, Rhincodon typus, aggregate to feed on fish spawn in Belize. Marine Ecology Progress Series 215 pp. 275–282.

- Higginbottom, K. 2004. Wildlife Tourism: Impacts, Management and Planning. Cooperative Research Centre for Sustainable Tourism Pty Ltd., Australia, p. 302.

- Hilbe, J.M. 2011. The Negative Binomial Regression. Cambridge University Press, London, UK, p. 553.

- Hueth, D. & E. Strong. 1984. A critical review of the travel cost, hedonic travel cost and household production models for measurement of quality changes in recreational experiences, Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, 13(2), pp. 89-107.

- Huveneers, C., M.G. Meekan, K. Apps, L.C. Ferreira, D. Pannell & G.M.S. Vianna. 2017. The economic value of shark-diving tourism in Australia. Rev Fish Biol Fisheries 27, 665–680 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.F., C. Gonzales, A. Townsel & A.M. Cisneros-Montemayor. 2019. Marine ecotourism in the Gulf of California and the Baja California Peninsula: Research trends and information gaps. Scientia Marina 83(2), June, pp. 177-185, Barcelona (Spain), . [CrossRef]

- Ketchum J.T. 2003. Distribución espacio-temporal y ecología alimentaria del tiburón ballena (Rhincodon typus) en la Bahía de La Paz y zonas adyacentes en el suroeste del Golfo de California. Master Thesis, p. 91, CICIMAR-IPN, La Paz.

- Ketchum, J.T., F. Galván-Magaña, & P. Klimley. 2013. Segregation and foraging ecology of whale sharks, Rhincodon typus, in the southwestern Gulf of California, Environmental Fish Biology, 96, pp. 779–755. [CrossRef]

- Koch, D-J. & M. Verholt. 2020. Limits to learning: the struggle to adapt to unintended effects of international payment for environmental services programmes. Int Environ Agreements, (20), pp. 507-539, DOI: . [CrossRef]

- Leh, F.C., Mokhtar, F.Z., Rameli, N., & Ismail, K. (2018). Measuring Recreational Value Using Travel Cost Method (TCM): A Number of Issues and Limitations. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 8(10), pp. 1381–1396.

- Milder, J.C., S.J. Scherr & C. Bracer. 2010. Trends and Future Potential of Payment for Milder, J. C., S. J. Scherr, and C. Bracer. 2010. Trends and future potential of payment for ecosystem services to alleviate rural poverty in developing countries. Ecology and Society 15(2): 4. [online] URL: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol15/iss2/art4/.

- Nelson, J.D., 2004. Distribution and foraging ecology by whale sharks (Rhincodon typus) within Bahia de Los Angeles, Baja California Norte, Mexico. MSc Thesis, University of San Diego, p. 118.

- Norman, B.M. & Stevens, J.D. 2007. Size and maturity status of the whale shark (Rhincodon typus) at Ningaloo Reef in Western Australia, Fisheries Research 84 pp. 81–86.

- Oropeza-Cortés, M.G., V. Hernández-Trejo & E. Romero-Vadillo. 2023. Economic valuation of recreational gray whale watching at San Ignacio Lagoon, Mexico. El Periplo Sustentable, 45, Jul-Dec, pp. 183-200. DOI . [CrossRef]

- Pearce, D.W. & R.K. Turner. 1990. Economics of natural resources and the environment. JHU Press.

- Pendleton, L.H. & J. Rooke. 2007. Using the Literature to Value Coastal Uses – Recreational Saltwater Angling in California. COVC (Coastal Ocean Values Center) Working Paper, pp. 1-36.

- Petatán-Ramírez, D., D.A. Whitehead, T. Guerrero-Izquierdo, M.A. Ojeda-Ruiz & E.E. Becerril-García. 2020. Habitat suitability of Rhincodon typus in three localities of the Gulf of California: Environmental drivers of seasonal aggregations. Journal of Fish Biology, 97(4), pp. 1177-1186.

- Ramírez-Macías, D. & G. Saad. 2016. Key elements for managing whale shark tourism in the Gulf of California. The 4th International Whale Shark Conference, 16-18 May, Doha, Qatar., p. 2.

- Ramírez-Macias, D. 2005. Characterization of Molecular Markers for populational studies of the whale shark (Rhincodon typus, Smith 1828) of the Gulf of California. The First International Whale Shark Conference: Promoting International Collaboration in Whale Shark Conservation, Science and Management, 9-12 May, Pert Western Australia, pp. 86.

- Randall, A. 1994. A diffilculty with the travel cost method. Land Economics 70(1), pp. 88-96.

- Reyes-Salinas, A., R. Cervantes-Durante, A. Morales-Pérez & J.E. Valdez-Holguín. 2003. Seasonal variability of primary productivity and its relation to the vertical stratification in La Paz bay, B.C.S. Hidrobiológica, 13, pp. 103–110.

- Rodger K., A. Smith, C. Davis, D. Newsome & P. Patterson. 2010. A framework to guide the sustainability of wildlife tourism operations: examples of marine wildlife tourism in Western Australia, Sustainable Tourism Pty Ltd (Ed.), p. 69.

- Rodríguez-Dowdell, N., R. Enríquez-Andrade & N. Cárdenas-Torres. 2007. Property rights-based management: Whale shark ecotourism in Bahia de los Angeles, Mexico. Fish. Res. 84, pp. 119-127.

- Rolfe, J. & P. Prayaga. 2007. Estimating values for recreational fishing at freshwater dams in Queensland. Aust. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 51(2), pp. 157-174. http://dx.doi.org/10.1011/j.1467-8489.2007.00369.x.

- Rowat, D. & Gore, M. 2007. Regional-scale horizontal and local-scale vertical movements of whale sharks in the Indian Ocean off Seychelles, Fisheries Research 84, pp. 32–40.

- Rowat, D., & Engelhardt, U. 2007. Seychelles: A case study of community involvement in the development of whale shark ecotourism and its socio-economic impact. Fisheries Research, 84(1), 109-113. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Sakamoto, A.T. 2015. Estimación del valor económico total y catálogo de foto identificación de la manta gigante (Manta birostris Walbaum, 1792) en el Archipiélago de Revillagigedo. Tesis de Licenciatura. UABCS., p. 46.

- Schwoerer, T., D. Knowler & S. Garcia-Martinez. 2016. The value of whale watching to local communities in Baja, Mexico: A case study using applied economic rent theory. Ecol Econ, 127, pp. 90-101.

- Secretaria de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales, SEMARNAT. 2018. Plan de Manejo de Rhincodon typus (tiburón ballena) para realizar la actividad de aprovechamiento no extractivo a través de la observación y nado en la Bahía de La Paz, B.C.S. Temporada 2018. México, p. 41.

- Shaw, D. 1998. On-site samples: Regression problems of non-negative integers, truncation and endogenous stratification. Journal of Econometrics, 37(2), 211-223 pp.

- Smith, K. & Y. Kaoru. 1990. Signals or Noise? Explaining the Variation in Recreation Benefit Estimates. American Journal of Agricultural Economics. 72(2), 419-433 pp.

- Stevens, J.D. 2007. Whale shark (Rhincodon typus) biology and ecology: A review of the primary literature. Fis. Res. 84, pp. 4-9.

- Sustainable Travel Tech: Innovations in Eco-Friendly Tourism. 2024. https://visitworld.live/sustainable-travel-tech-innovations-in-eco-friendly-tourism/. Accessed 11-Nov.

- Taylor, J.G. 2007. Ram filter-feeding and nocturnal feeding of whale sharks (Rhincodon typus) at Ningaloo Reef, Western Australia, Fisheries Research 84 pp. 65–70.

- Taylor, J.G., 1996. Seasonal occurrence, distribution and movements of the whale shark, Rhincodon typus, at Ningaloo Reef, Western Australia. Mar. Freshw. Res. 47, pp. 637–642.

- The Economics of Ecosystem Services and Biodiversity. TEEB. 2012. Why Value the Oceans? A Discussion Paper. The Economics of Ecosystems & Biodiversity.

- Tisdell, C.A. 2002. The Economics of Conserving Wildlife and Natural Areas, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK.

- Topelko, K.N. & P. Dearden. 2005. The Shark Watching Industry and its Potential Contribution to Shark Conservation, Journal of Ecotourism, 4:2, 108-128, DOI: 10.1080/14724040409480343.

- Turner, R.K., D.W. Pearce & I. Bateman. 1993. Environmental Economics. An Elementary Introduction. JHU Press (Ed.), p. 328.

- Valentine, A.V.P. & Curnock, M. 2001. Wildlife Tourism Research Report No. 11, Status Assessment of Wildlife Tourism in Australia Series, Tourism Based on Free-Ranging Marine Wildlife: opportunities and responsibilities. CRC for Sustainable Tourism, Gold Coast, Queensland.

- Vásquez-Lavín, F., A. Cerda-Urrutia & S. Orrego-Suaza. 2007. Valoración Económica del Ambiente. Thomson Learning (Ed.), p. 368.

- Vianna, G.M.S., J.J. Meeuwig, D. Pannell, H. Sykes & M.G. Meekan. 2011. The socio-economic value of the shark-diving industry in Fiji. Australian Institute of Marine Science. University of Western Australia. Perth, p. 26.

- Vianna, G.M.S., M.G. Meekan, D.J. Pannell, S.P. Marsh & J.J. Meeuwig. 2012. Socio-economic value and community benefits from shark-diving tourism in Palau: A sustainable use of reef shark populations. Biological Conservation, 145, pp. 267-277.

- Vivekanandan E. & M.S. Zala. 1994. Whale shark fishery off Veraval. Indian Journal of Fisheries. 41, pp. 37-40.

- Wells, M.P. 1998. Socio-economic and political aspects of biodiversity conservation in Nepal. International Journal of Social Economics, 25(2/3/4): 226-243.

- Whitehead D.A., U. Jakes-Cota, F. Pancaldi, F. Galván-Magaña & R. González-Armas. 2020. The influence of zooplankton communities on the feeding behavior of whale sharks, Gulf of California. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 91: e913054, . [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, D.A., D. Petatán-Ramírez, D. Olivier, R. González-Armas, F. Pancaldi & F. Galvan-Magaña. 2019. Seasonal trends in whale shark Rhincodon typus sightings in an established tourism site in the Gulf of California, Mexico. J. Fish Biol., 95:982–984, DOI: 10.1111/jfb.14106.

- Wilson, C. & C. Tisdell. 2002. Conservation and Economic Benefits of Wildlife-based Marine Tourism: Sea Turtles and Whales as Case Studies. Working Paper #64, Working Papers on Economics, Ecology and The Environment, School of Economics, The University of Queensland, pp. 19.

- Wolfson F.H. 1987. The whale shark Rhincodon typus, Smith 1828, off Baja California, México (Chondrichthyes: Rhincodontidae). Mem. Vth Symp. Biol. Mar., UABCS, 5: pp. 103-108.

- Womersley, F. C., Humphries, N. E., Queiroz, N., Vedor, M., da Costa, I., Furtado, M., Tyminski, J. P., Abrantes, K., Araujo, G., Bach, S. S., Barnett, A., Berumen, M. L., Lion, S. B., Braun, C. D., Clingham, E., Cochran, J. E. M., de la Parra, R., Diamant, S., Dove, A. D. M., ... Sims, D. W. 2022. Global collision-risk hotspots of marine traffic and the world’s largest fish, the whale shark. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 119(20), Article e2117440119. [CrossRef]

- Wooldrige, J.M. 2002. Econometric Analysis Cross Section and Panel Data. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. MIT Press. 777 p.

- Wunder, S. 2005. Payment for environmental services: Some nuts and volts. CIFOR Ocassional Paper No 42. Center for International Forestry Research, Jakarta, Indonesia.

- Zhang, F., Wang, X., Nunes, P.A.L.D. & Ma, C. 2015. The recreational value of gold coast beaches, Australia: An application of the travel cost method. Ecosystem Services, 11, pp. 106-114. [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, A., P. Dearden & R. Collins. 2015. Participant crowding and physical contact rates of whale shark tours on Isla Holbox, Mexico, Journal of Sustainable Tourism, DOI: 10.1080/09669582.2015.1071379.

- Ziegler, J. & P. Dearden. 2021. Whale Shark Tourism as an Incentive-based Conservation Approach. Whale Sharks: Biology, Ecology, & Conservation. Edited by Alistair D. M. Dove and Simon J. Pierce, 2nd Ed. Taylor & Francis. Chapter 10, (Azikiwe & Bello, 2020b) Azikiwe, H., & Bello, A. (2020b). Book title. Publisher Name. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).