1. Introduction

For many children, the abstract concept of time can be a source of frustration and anxiety, particularly in the structured environment of an assessment. The rigid temporal structure of assessments, characterized by a clearly defined beginning, middle, and end, can have a significant impact on students' cognitive abilities. To address this challenge, visual timers are becoming increasingly common in classrooms and therapy settings. They help children visualize and manage their time (Grey et al., 2009; Gast & Tawney, 2014; Janeslätt et al., 2014). This is especially relevant given children's perception of time develops gradually with age (Droit-Volet, 2013, 2016) and tools that make time concrete can facilitate this process (Neufeld & Stewart, 2023; Tartas, 2010). By supporting the development of time perception and management, visuals timers can play a crucial role in school settings.

Hallez and Rebecchi (2024) demonstrated that the presence of a visual timer during a math assessment reduced children’s assessment-related anxiety and improved performance. Performance improvements were particularly striking in students having strong attentional skills. However, although their study highlighted the potential benefits of visual timers, Hallez and Rebecchi (2024) did not specifically analyze whether and to what extent children looked at and used the visual timer during the task. Nor did they investigate whether timer use was associated with a reduction in off-task behaviors. Building on this work, the present study aims to replicate these findings while also examining how children interact with the visual timer, an analysis crucial for developing more equitable and effective classroom practices. The findings could enhance our understanding of children’s time management under evaluative conditions and inform pedagogical practices aimed at supporting both academic performance and well-being.

1.1. Keeping Track of Time and Attention Capacities

Research over recent decades has demonstrated that humans, like all animals, possess an internal clock system that allows them to measure time. However, while our brains have built-in mechanisms for tracking time, this system does not always lead to accurate time estimation. Humans often perceive time as either expanded or contracted, judging it to be longer or shorter than it actually is. This distortion in time perception is influenced by several factors, such as the attention allocated to processing time (Nobre & Coull, 2010). When our attention is diverted from the passage of time, we tend to perceive durations as shorter. This tendency to underestimate time when distracted has been widely documented in behavioral studies using the dual-task paradigm (Brown et al., 2013; Casini & Macar, 1997, 1999; Champagne & Fortin, 2008; Hemmes et al., 2004; for a review, see Block et al., 2010). In this paradigm, participants judge the duration of a stimulus either alone or while simultaneously performing a secondary, non-temporal task (e.g., calculation, color discrimination, or memory task). Regardless of the specific secondary task used, results consistently show that perceived duration is shorter in the dual-task condition compared to the single-task condition.

For instance, Hallez and Droit-Volet (2017, 2019) found that 5- to 8-year-old children's performance on both time reproduction and color discrimination tasks declined when performed simultaneously. Interestingly, authors also showed that this bias decreases with increasing selective attention abilities. Selective attention allows individuals to prioritize stimuli that are relevant to their own needs and goals, filtering out distractions and enabling them to focus on what matters most (Johnston & Dark, 1986; Treisman, 1964). This suggests that time processing, in the context of an evaluation, competes for attentional resources, creating a cognitive load that can negatively impact performance on both temporal and non-temporal tasks (Hallez & Droit-Volet, 2017, 2019; Irwin-Chase & Burns, 2000).

Since attention plays a fundamental role in time estimation, researchers have therefore formalized an attentional mechanism into internal clock models. According to the pacemaker-accumulator model (Gibbon et al., 1984), all individuals possess an “internal clock” that allows them to process time, composed of a pacemaker, a switch, and an accumulator. This theoretical model posits that time perception relies on a three-component system. First, an internal pacemaker generates neural pulses at a constant rate, serving as the raw units of subjective time. Second, an attentional switch regulates the transmission of these pulses to the next stage. When attention is directed towards monitoring duration, the switch opens. Conversely, when attention is absorbed by a non-temporal task or stimulus, the switch tends to close, blocking the pulses. Finally, an accumulator sums the total number of pulses that have passed through the switch, with this total forming the basis for our internal representation of elapsed time. This mechanism explains how engaging in a task can lead to an underestimation of duration, as attention is diverted from timekeeping.

Indeed, the perceived duration directly depends on the number of stored pulses: more pulses meaning a longer perceived duration. A decrease in attention to time can affect the “switch” by causing it to flicker between open and closed states during the timing process. This “flickering” switch” phenomenon means that the switch intermittently fails to remain open, preventing some pulses from the pacemaker from reaching the accumulator. Consequently, fewer pulses are stored, leading to an underestimation of the elapsed time.

This explains why distractions can make time seem to fly by and why individuals with attention deficits, such as those with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, often struggle with time estimation (Nejati & Yazdani, 2020). Evaluating behaviors related to attentional and executive functions therefore allows us to examine whether the visual timer can act as an external support for temporal regulation and exert an influence. Moreover, the use of a visual timer could be a way to compensate for inequalities in evaluation situations. More recent neurocomputational models further emphasize the central role of attention in time perception, suggesting that it is not just a simple on/off switch but a complex process that integrates temporal information with other cognitive functions (Hallez et al., 2023). Therefore, the cognitive load associated with simultaneously processing time while performing a mathematical task reduces performance on the mathematical task (Hallez & Rebecchi, 2024). In a timed test without a visual timer, the participant relies on their internal clock, which consumes cognitive resources in addition to the task. This study hypothesizes that the presence of a visual timer would free up cognitive space and therefore improves performance. In addition, it would reduce dependence on the internal clock. Given these attentional difficulties, a visual timer could help reduce off-task behaviors (such as motor instability and inattention) and provide support for temporal organization during a task.

1.2. Evaluation Anxiety

In close connection with attentional skills, it is also relevant to consider the concept of evaluation anxiety. This refers to the anxiety experienced in evaluative situations (Zeidner, 1998). Zeidner identifies two components of evaluation anxiety: a cognitive component (worrying about one’s own performance) and an emotional component (physiological arousal - e.g., sweaty palms, racing heart - and negative emotions). The phenomenon of performance decline among individuals experiencing evaluation anxiety is well-documented in university and high school students (Fenouillet et al., 2023; Prokofieva et al., 2024).

The cognitive mechanisms involved in evaluation anxiety appear to center on attention, as described in the cognition–attention interference theory (Sarason, 1984) and, more recently, in the attentional control theory (Eysenck et al., 2007). These theories propose that deficits in attentional control play a central role in the development of anxiety. A 2019 meta-analysis by Shi et al., which included 58 studies, confirmed the link between anxiety levels and deficits in attentional control. According to this hypothesis, individuals experiencing evaluation anxiety divide their attention between the task at hand and distracting thoughts of doubt, worry, and self-criticism. This divided attention reduces focus on the task and leads to poorer performance.

In this context, time constraints in assessments are a factor to consider, especially since they are widely adopted in education systems worldwide, with the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) being one example among many, which imposes time limits to ensure standardization and comparability across countries (OECD, 2025). However, these constraints are known to exacerbate assessment anxiety (Zeidner, 1998), a finding confirmed by international studies (Owens et al., 2014; Sussman and Sekuler, 2022). Thus, while time limits ensure the implementation of more easily comparable and standardized assessments, they may also intensify attentional disruptions and further impair the performance of anxious students.

This aligns with the findings of Hallez and Rebecchi (2024), who observed that time-constrained assessments without a visual timer resulted in higher evaluation anxiety and lower math scores among participants. However, this study suggests that the use of a visual timer may be sufficient to reduce the cognitive load associated with temporal processing during such assessments, thereby allowing children to better regulate their anxiety within a time-constrained context.

1.3. The Role of Executive Functions and On-Task Behaviors

The positive impact of the visual timer observed in Hallez and Rebecchi's (2024) study may be partly attributed to a general effect on executive functions. Executive functions encompass a set of higher-order cognitive processes that enable goal-directed behavior, including planning (the ability to create a roadmap to reach a goal or to complete a task), working memory (the ability to hold and manipulate information in mind over short periods), inhibition (the ability to control one's attention, behavior, thoughts, and/or emotions to override a strong internal predisposition or external lure), and cognitive flexibility (the capacity to switch gears and adjust to changed demands, priorities, (Diamond, 2013, 2020). In the context of a timed assessment, these functions are crucial for effectively managing time, maintaining focus, and regulating emotions. Similar to its potential role in emotional regulation, the visual timer may also support executive functions by offloading some of the cognitive demands associated with time monitoring. The timer may act as an external support for temporal processing, reducing the burden on executive functions and allowing students to better regulate their cognitive resources.

Difficulties in executive functions can lead to decreased on-task behaviors (McCloskey et al., 2018) including fidgeting, daydreaming, or engaging in activities unrelated to the task. It is thus hypothesized that the visual timer may promote on-task behaviors by supporting executive function. By making the passage of time more salient and predictable, the visual timer may create a more structured and supportive environment that fosters on-task behaviors and reduces off-task behaviors, such as fidgeting or motor impulsivity. Additionally, the timer may help to structure the task into smaller, more manageable intervals, enhancing the students' sense of progress.

1.4. Aim of the Study

Building on previous findings, this study investigates the effects of using a visual timer on elementary school students' performance, anxiety levels, and behaviors during a mathematics assessment. The first objective of this study is to replicate the findings of Hallez and Rebecchi (2024) regarding the positive effects of visual timers on anxiety and performance in an exam context. Specifically, we hypothesize that: (1) pupils' mathematical performance will be higher in the visual timer condition compared to the timed assessment without a visual timer; and (2) the assessment with a visible timer will result in lower evaluation anxiety compared to the evaluation without a visible timer.

Furthermore, this study expands upon previous research by investigating how children interact with the Time-Timer and to what extent they utilize it, while also analyzing the timer's influence on their behavior throughout the task. This is an aspect that, to our knowledge, has not yet been investigated. We hypothesize that the visual timer condition will improve on-task behaviors with (3) fewer inattentive behaviors and (4) reduced motor instability compared to the no-timer condition. As an exploratory measure, we will also analyse how often children look at the Time-Timer to gain insight into their engagement with it. Finally, we will analyze whether individual cognitive processes, specifically selective attention and executive functions, moderate the relationship between the use of visual timers and the outcomes mentioned above (performance, anxiety, behavior). We hypothesized that (5) the extent to which individuals benefit from the visual timer will be related to their underlying cognitive abilities, particularly selective attention and executive functions. Individuals with stronger attentional abilities and executive functions may be better equipped to utilize the timer effectively, leading to greater improvements in on-task behaviors and potentially academic performance.

To test our hypotheses, 44 children aged 7 to 9 will participate in a mathematical assessment under two counterbalanced conditions: with and without a visual timer. This age range, similar to Hallez and Rebecchi (2024), was chosen because it represents a critical period marked by substantial maturation in explicit time judgment abilities (Droit-Volet, 2016; Droit-Volet & Zélanti, 2013; Hallez & Droit-Volet, 2020), making it an ideal in which to study the effects of interventions targeting time perception.

2. Method

2.1. Study Design

This quantitative study, conducted in French schools, investigated the impact of visual timers on mathematical performance, test-related anxiety, and off-task behaviors among students aged 7 to 9 years during a timed assessment. We employed a within-subjects design with two assessment contexts: one without a timer and one with a visual timer. Each participant took two versions of a mathematics test, administered on two separate mornings, one week apart, and always at the same time.

2.2. Participants

The study was conducted with a sample of 44 students (24 boys and 20 girls) enrolled in two schools located France [precise location was blanked to ensure anonymity during the review process]. The students were from 3 different class groups (i.e., 2 CE2 classes and 1 CE1 class, which correspond to grades 3 and 2 in the US system). At the time of the study, they were aged between 7 years 1 month and 9 years 0 months (mean age: 8.1 years, standard deviation: 0.5) and all participants were native French speakers and followed a typical French curriculum. The children’s parents signed written informed consent for participation in this study. The study adhered to the Helsinki Declaration and received approval from (1) the Academic School for Continuing Education of the academy where the experiment took place, (2) the Department of National Education Services of the region, and (3) the national education inspector.

2.3. Instruments

To answer our research questions, we relied on a set of standardized assessments, questionnaires, and observational measures targeting mathematics performance, assessment anxiety, attentional control, and executive functioning.

2.3.1. Mathematics Assessment

The assessment materials were drawn directly from the open-access exercises provided in the study by Hallez & Rebecchi (2024). These consisted of two mathematics tests adapted from Exercise 7 of the national mathematics assessment administered in September 2022 to all first-year elementary students (CE1) in the French education system. Each version included 14 multiple-choice calculations and 14 calculations requiring written answers. To ensure appropriate difficulty for second-year students (CE2), the latter authors also developed two versions of a more challenging task. Each student completed two versions of the assessment, with the difficulty level adjusted based on their class.

2.3.2. Evaluation Anxiety Questionnaire (STA)

To measure children's anxiety in evaluative situations, we used the French version of the State Test Anxiety questionnaire (STA; Beaudoin & Descrichard, 2009; Zeidner, 1998). This 6-item questionnaire, with responses on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = "not at all" to 6 = "very much"), has been validated in individuals aged 15 to 68 years. In our study, it demonstrated good internal consistency for our younger participants (Cronbach's alpha = 0.80; McDonald's omega = 0.80).

2.3.3. Conners' Questionnaire

The Conners' scales (1969) were used to assess behaviors related to children's attentional and executive functions. They are primarily used in clinical practice and research to identify children and adults with risk of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (for a review, see Pagán et al., 2023). The abbreviated version, consisting of 10 items with a 4-point Likert scale response format, is extremely short and easy to complete. It can be completed by any external observer (parent, teacher, tutor) and yields a unidimensional score for evaluating the intensity of hyperactive behaviors (Nguyen et al., 2024).

2.3.4. Behavioral Observation Grid

During each mathematical assessment, student behaviors unrelated to the task were observed and counted. These were classified into two categories inspired by subtests of the NEPSY-II neuropsychological assessment (Kemp et al., 2012): inattentive behaviors (e.g., turning head towards a distraction, looking out the window) and motor instability behaviors (e.g., getting up, fidgeting in the chair, changing pens). In addition, in the visual timer condition, the number of times the child looked at the timer was also recorded as a third dimension.

2.3.5. Neuropsychological Tests

Two neuropsychological tests were taken from the TEA-Ch battery: Test of Everyday Attention for Children (Manly et al., 1999). The Sky Search test measures selective attention in the visual modality. The child is presented with a sheet containing 130 spaceships of 5 different types. The child's task is to circle all pairs of identical spaceships as quickly as possible, ignoring distractors. Attentional quality is estimated by calculating the speed/accuracy ratio. The Doing Two Things at Once test measures sustained and divided attention in the visual and auditory modalities. The child must circle pairs of identical spaceships, while counting the laser-like gunshots heard during the task.

Two other tests were taken from the FEE battery: Child Executive Functions Assessment Battery (Roy et al., 2021). The Stroop test is a classic neuropsychological test (Stroop, 1935) that assesses the ability to inhibit a dominant interfering response. In the version used in this study, two control conditions are proposed: color naming, which allows consideration of the child's language skills, and the reading condition, which aims to reinforce the automaticity of reading color names. The condition of reading color names written in incongruent ink occurs in a third stage to measure the interference effect. The Trail Making Test is another widely used neuropsychological test (Reitan, 1958) that assesses mental flexibility. In the FEE battery version, the child must first connect numbers in ascending order and then letters in alphabetical order. After these two control conditions, the child is asked to connect the numbers and letters alternately (1-A-2-B-3-C...), this condition requiring them to switch from one category to another with each item.

2.4. Procedure

After obtaining consent from the children and their parents, we collected data from January to April 2024. The mathematics assessment tasks were administered individually in a quiet place near the classroom; each child was exposed to two different contexts in two different days: without a timer and with a timer. A potential order effect was controlled by counterbalancing the two assessment contexts.

Before each test, standardized instructions were given orally "Today, you will take a math test. On the first page, you need to find the result of each calculation and then circle it. When you have finished the first page, you turn the page: on the second page, you need to find the result of each calculation and then write it down. The goal is to go as fast as possible to get the most correct answers. If you don't know, don't circle anything and move on to the next calculation. There are a lot of calculations, it's normal not to be able to do everything."

In the context without visual timer, last sentence was - "This test is timed: you will only have 5 minutes. At the end of the 5 minutes, you will hear a buzzer, and you will have to put your pencil down, even if you have not finished". In the visual timer context, the last sentence was : "This test is timed: you will only have 5 minutes. You will be able to see the time passing with the timer. At the end of the 5 minutes, you will hear a buzzer, and you will have to put your pencil down, even if you have not finished."

The evaluation of evaluation anxiety using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory scale was carried out immediately after the instructions for the mathematics assessment task were given. The individual administration of the neuropsychological tests was carried out following the two mathematics assessments, on a third day; the order of presentation of the tests was randomized.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

A power analysis was performed using G*Power (version 3.1) to determine the required sample size for a paired-samples t-test (two-tailed, α = 0.05, 1–β = 0.80). Estimating a medium effect size (Cohen's dz = 0.50), the required sample size was estimated at N = 34. To account for potential variables, we planned to recruit at least 40 participants. Our final sample size was N = 44, exceeding the planned minimum.

Correct answers on the math test were counted for each child in both conditions (with and without a visual stopwatch). Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, skewness, and kurtosis) were calculated to summarize the data. All variables, except the number of errors, met the assumption of univariate normality, as indicated by skewness and kurtosis values between –2 and +2. Following these checks, repeated-measures ANOVAs were performed on correct responses, with Holm corrections (results were identical to Bonferroni corrections). Effect sizes were reported using η² and partial η². To further explore significant ANOVA effects, paired-samples t-tests were performed.

3. Results:

3.1. Math Performance & Evaluation Anxiety

Table 1 descriptively presents the calculation scores rates and anxiety scores obtained by the students (n = 44) in the two experimental contexts (i.e., with a visual timer and without a visual timer).

While a slight increase in math scores was observed in the visual timer condition, a paired-samples t-test showed no significant difference in performance between the timer and no-timer conditions, t(44) = -0.44, p = 0.66, Cohen’s d = -0.067. Note that similar results where found when the analysis was run on the number of errors made by the children.

Notwithstanding, the analysis on anxiety (STA scores) showed a significant effect of the experimental condition. The paired t-test confirmed that anxiety levels were significantly lower in the presence of a visual timer compared to the situation without a visible time (t(43) = 2.77, p =.008).

3.2. Off-Task Behavior and Glances at the Time Timer

Observation of behaviors during the task revealed a significant effect of the timer’s visibility on inattentive and motor instability behaviors (cf

Table 2). A Wilcoxon test confirmed that the number of inattentive behaviors was significantly lower in the presence of a timer (W = 55, n = 44, z = 2.803,

p =.002). A similar, but less pronounced, effect was observed for motor instability behaviors (W = 72, n = 44, z = 1.852, p = .03).

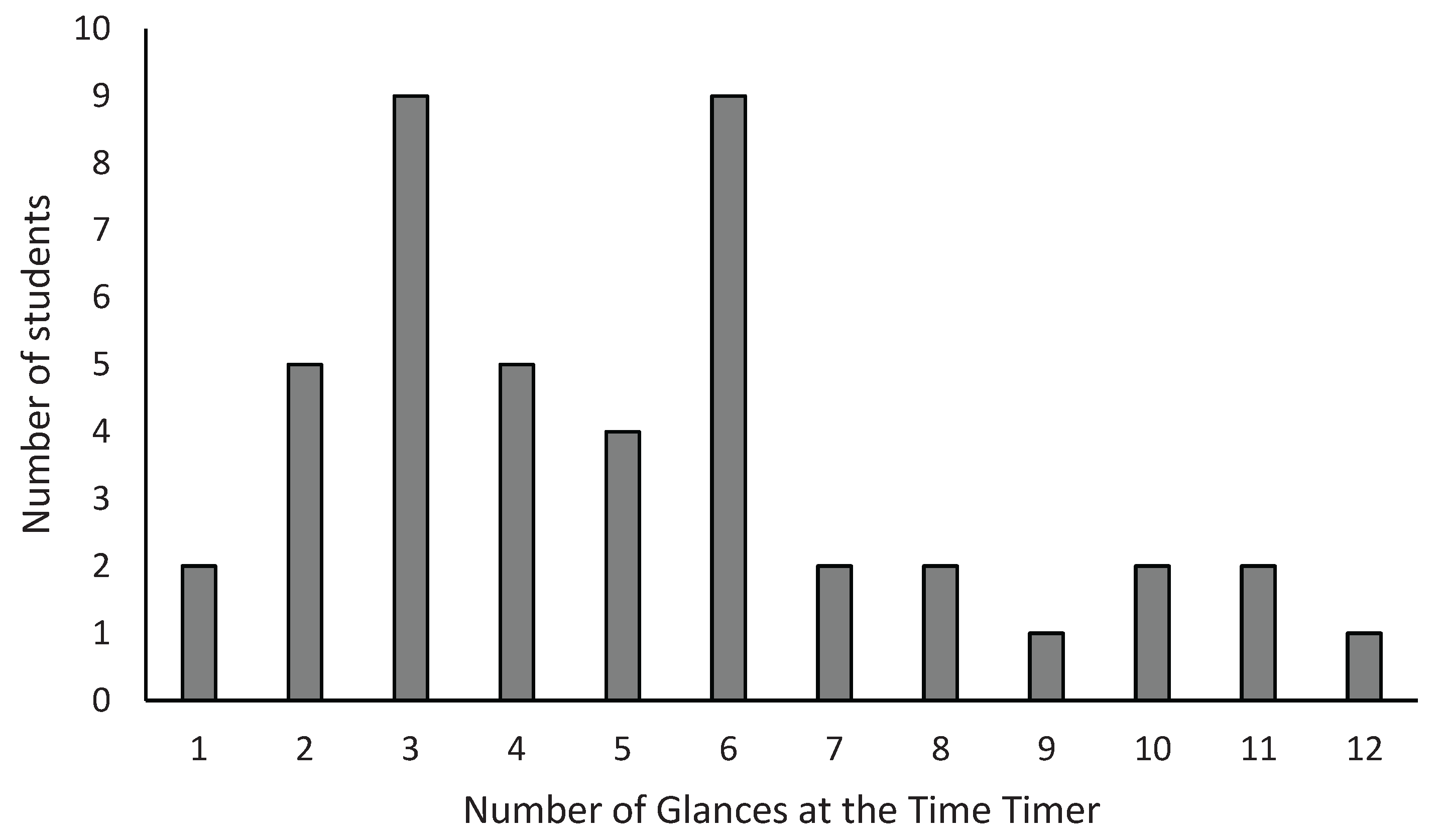

Examining children’s engagement with the Time Timer in the visible timer condition reveals heterogeneous usage patterns.

Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of visual attention directed towards the Time-Timer. Notably, two students did not look at the device, whereas a quarter of the participants (n = 10) engaged in frequent visual checks (more than 7 instances). The remaining students (n = 32) looked at the Time-Timer between one and seven times during the five-minute assessment.

3.3. Relationship with Neuropsychological Tests

Correlation analyses were conducted to explore the relationship between the effects of the timer found in our study and scores on neuropsychological tests. A significant correlation was found between the decrease in inattentive behaviors in the presence of the timer and risk of ADHD measured with the Conners’s questionnaire (

Table 3). Specifically, the beneficial effects of timer from non-visible to visible assessment was higher for children with higher risks of ADHD scores (r = 0.39, p = 0.03). Other correlations were not significant.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to investigate how the use of a visual timer impacted mathematical performance, the evaluation anxiety and on-task behaviors of 7- to 9-year-old students during a school assignment. We expected that using the timer would generally improve student performance, reduce anxiety, and decrease the number of off-task behaviors. We also postulated that these effects could be dependent upon the student’s executive functioning and attentional abilities.

First, our study successfully replicated the findings of Hallez & Rebecchi (2024) regarding evaluation anxiety. Specifically, participants in the visible-timer condition demonstrated a significant reduction in anxiety levels relative to the condition without a visible timer. While both of our experimental conditions involved time limitations, it is the explicit presence of the timer in one condition that appears to have reduced anxiety. While prior research often reports a link between time pressure and heightened anxiety in assessment situations (Caviola et al., 2017; McDonald, 2001), our results highlight that providing a clear indication of remaining time may, in fact, mitigate these effects. This finding thus offers a more nuanced perspective on the relationship between time pressure and anxiety, suggesting that the way time pressure is presented can significantly influence its impact. In the absence of a visible timer, individuals may experience heightened worry and rumination about the remaining time. This uncertainty likely consumes attentional resources, diverting them from the mathematical task. Conversely, the visible timer may lessen this cognitive burden by providing a clear and concrete representation of the time constraint.

Consequently, more attentional resources could be mobilized to engage in the task, particularly in mathematical problem solving, which was the focus of our experiment. Yet, our study found no significant impact of the timer's visibility on participants' performance. This contrasts with some prior research and warrants further consideration. Several factors may contribute to this lack of a discernible effect. One key difference lies in the testing environment: whereas the study that reported this effect employed group-administered assessments, our experiment involved individual testing sessions. This was necessary to precisely quantify gaze behavior toward the timer and other task-unrelated actions. The individual testing format, particularly the experimenter's direct observation, may have optimized arousal and performance even in the condition without a visible timer. In this condition where participants were aware of the time constraint but lacked a visual cue, the presence of the experimenter might have served as a salient performance cue. A substantial body of research in social psychology underscores the significant influence of an observer's presence on individual performance (Cottrell, 1972). Cottrell's work further suggests that the observer's perceived status can modulate this effect, with an "expert" observer tending to enhance motivation and performance. Moreover, the social control hypothesis (Guérin, 1983) posits that the proximity of others and the direction of their gaze are important factors in social facilitation. Therefore, in our individual testing setting, the experimenter's direct observation may have acted as a potent activating factor, potentially maximizing participants' performance even when a timer was not visually present. This could have created a ceiling effect and reduced any potential for the timer to further enhance performance.

Although the timer's visibility did not translate into measurable performance gains, its effects were particularly notable at the behavioral level, impacting how children managed their attention and activity during the task. Indeed, our results revealed a notable influence of the timer's visibility on participants' behavior during the task. Specifically, the presence of a visible timer corresponded with a reduction in both inattentive and motor instability behaviors. This suggests that when participants had a clear awareness of the remaining time, they exhibited greater focus and further controlled behavior. These findings align with the broader literature on the effects of time awareness on cognitive performance. For instance, research has shown that providing individuals with time-relevant information can enhance their self-regulation and task engagement (e.g., Kanfer & Ackerman, 1989). In the context of our study, the visible timer may have served as a regulatory cue, prompting participants to allocate their attention more effectively and minimize extraneous movements. This interpretation is also consistent with the attention control theory (Eysenck et al., 2007) previously exposed. By potentially mitigating uncertainty-related anxiety, the visible timer may have facilitated a more focused and deliberate approach to the task, resulting in fewer instances of inattentive and restless behaviors.

Beyond its role in reducing anxiety, the impact of a visible timer could more broadly influence the ability to reduce cognitive load and free up additional attentional resources. This hypothesis seems to be supported by our results, particularly the finding that the effects of the visual timer on reducing off-task behaviors were more pronounced for children at higher risk for ADHD. This aligns with research suggesting that external aids and environmental modifications can be effective strategies for managing ADHD symptoms (DuPaul et al., 2011; Evans et al., 2018). Nonetheless, our study found limited evidence for a relationship between participants' cognitive abilities, as measured by standard neuropsychological tests, and the observed variations in anxiety and behavior associated with the timer's presence. If the effect of a visible timer had been solely attributable to attentional resources or executive functions, one would have anticipated replicating these effects on the other variables. A potential explanation for this inconsistency is the possibility of a non-linear relationship between these variables. Alternatively, it could be attributed to the Conners' questionnaire's primary focus on attentional and executive function impairment (Pagán et al., 2023). Future research should specifically investigate the efficacy of visual timers as an intervention for children diagnosed with ADHD.

It should also be noted that other individual differences, not measured in this study, could also play a role. For instance, students' perceived competence in mathematics (i.e., their self-efficacy; Bandura, 1997, 2006; Honicke & Broadbent, 2016) or their general attitudes towards mathematics (Hwang & Son, 2021) might influence their anxiety between conditions and how they respond to the timer. Students with low self-efficacy might experience heightened anxiety even with a timer present, while those with positive attitudes towards school might be more receptive to its regulatory influence.

This observed variation in the frequency of glances at the Time-Timer, ranging from no glances to over twelve within the five-minute assessment, further complicates the interpretation of its impact. While the data indicates that many children did visually engage with the timer, suggesting its potential utility as a time management tool, the high frequency of glances observed in some participants (25%, n=10, looked at it more than 7 times) raises questions about optimal usage patterns. It is possible that, for some children, particularly those in this age group (7-9 years old), the novelty of the Time-Timer led to excessive monitoring, potentially diverting attentional resources away from the task itself. This could be especially true if children are not accustomed to using such a tool for time management. The Time-Timer, although intended to reduce cognitive load, might have inadvertently increased it for some students who became overly focused on tracking the time. This highlights the importance of considering individual differences in how children interact with and adapt to new tools. Future research should investigate the potential benefits of providing explicit instruction and practice in using the Time-Timer, to determine whether familiarization and training can lead to more effective and less distracting usage patterns.

One limitation of this study is that the testing environment was individual. This condition, necessary for accurate behavioral observation, may have introduced a ceiling effect on performance, as the experimenter's presence is a powerful predictor of performance, even in the absence of a visible timer. Future research should explore these effects in a more naturalistic classroom setting with group-administered tasks. Furthermore, the study's focus on a relatively small sample of French students necessitates further investigation on a larger and more diverse scale to enhance generalizability. Furthermore, exploring the relationship between age, prior experience with visual timers, and the frequency of glances could shed light on developmental factors that influence the efficacy of this tool.

5. Conclusion

To conclude, this study highlights the multifaceted impact of visual timers, specifically the Time-Timer, on students' cognitive, emotional, and behavioral dimensions during timed math assessments. While the timer did not directly enhance math performance in this particular context, its significant effect on reducing anxiety and promoting on-task behaviors, particularly for students at higher risk for ADHD, underscores its potential as a valuable tool in educational settings. Ultimately, the Time-Timer may serve as a simple yet powerful tool for fostering a sense of control and reducing anxiety, allowing students to better focus on the task at hand and reach their full academic potential. However, the observed variability in usage patterns, particularly frequent glances, also highlights the need for further research on optimal implementation strategies. Future research could explore these strategies, particularly in group classes and over extended periods of use. This work would help clarify the optimal conditions under which visual timers most effectively promote learning and engagement. This is crucial for developing equitable classroom practices, as a one-size-fits-all approach may inadvertently neglect the students most in need of support.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.H; methodology, Q.H; formal analysis, Q.H. investigation, Q.H. writing—original draft preparation, V.V & Q.H.; writing—review and editing, V.V & Q.H., supervision, Q.H; project administration, Q.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. In line with the national procedures governing research within French educational institutions, the study protocol was submitted to and approved by the relevant academic authorities.

Hierarchical approval was granted by the Departmental Directorate of National Education Services (DSDEN), the Academic Unit for Research, Development, Innovation, and Experimentation (CARDI) for the Rhône academic region, the District Superintendent, and the Principal of the participating school. In the context of the French education system, this multi-level validation process constitutes the required ethical and procedural authorization for conducting research with minors in a school setting. Therefore, a separate review by a university-based Institutional Review Board (IRB) was not required.

Informed Consent Statement

Prior to participation, informed consent was obtained from the parents of the minor participants. The consent of the directors of the schools was also obtained.

Declaration of interest

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Declaration of generative AI in scientific writing

Authors used Gemini 2.0 Advanced, for assistance with English phrasing and spelling during the preparation of this scientific document. All content was subsequently reviewed, edited, and approved by authors. The tool was solely used for traduction. Authors take full responsibility for the content of the publication

Acknowledgement

Authors would like to thank [blanked to respect anonymity for the review process], who contributed to the data collection.

References

- Bandura, A., & Wessels, S. (1997). Self-efficacy (pp. 4-6). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bandura, A. (2006). Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents, 5(1), 307-337.

- Beaudoin, M. , & Desrichard, O. (2009). Validation of a Short French State Test Worry and Emotionality Scale. Revue internationale de psychologie sociale 22, 79–105.

- Block, R. A. , Hancock, P. A., & Zakay, D. (2010). How cognitive load affects duration judgments: A meta-analytic review. Acta psychologica. [CrossRef]

- Brown, S. W. , Collier, S. A., & Night, J. C. (2013). Timing and executive resources: dual-task interference patterns between temporal production and shifting, updating, and inhibition tasks. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. [CrossRef]

- Casini, L. , & Macar, F. (1997). Effects of attention manipulation on judgments of duration and of intensity in the visual modality. Memory & cognition. [CrossRef]

- Casini, L. , & Macar, F. (1999). Multiple approaches to investigate the existence of an internal clock using attentional resources. Behavioural Processes. [CrossRef]

- Caviola, S. , Carey, E., Mammarella, I. C., & Szucs, D. (2017). Stress, time pressure, strategy selection and math anxiety in mathematics: A review of the literature. Frontiers in Psychology, 8. [CrossRef]

- Champagne, J. , & Fortin, C. (2008). Attention sharing during timing: Modulation by processing demands of an expected stimulus. Perception & psychophysics. [CrossRef]

- Cottrell, N. B. (1972). Social facilitation. In C. G. McClintock (Ed.), Experimental social psychology (pp. 185-236). New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

- Diamond, A. (2013). Executive functions. Annual review of psychology, 64. [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A. (2020). Executive functions. In Handbook of clinical neurology (Vol. 73, pp. 225-240). Elsevier.

- DuPaul, G. J. , Weyandt, L. L., & Janusis, G. M. (2011). ADHD in the classroom: Effective intervention strategies. Theory into practice, 50, 35–42.

- Droit-Volet, S. (2013). Time perception in children: A neurodevelopmental approach. Neuropsychologia. [CrossRef]

- Droit-Volet, S. (2016). Development of time. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 8, 102-109. [CrossRef]

- Droit-Volet, S. , & Coull, J. T. (2016). Distinct developmental trajectories for explicit and implicit timing. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 150, 141–154. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Droit-Volet, S. , & Hallez, Q. (2019). Differences in modal distortion in time perception due to working memory capacity: a response with a developmental study in children and adults. Psychological Research, 83. [CrossRef]

- Droit-Volet, S. , & Zélanti, P. S. (2013). Development of time sensitivity and information processing speed. PloS one 8(8), e71424. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, S. , Ling, M., Hill, B., Rinehart, N., Austin, D., & Sciberras, E. (2018). Systematic review of meditation-based interventions for children with ADHD. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. [CrossRef]

- Eysenck, M. W. , Derakshan, N., Santis, R., & Calvo, M. G. (2007). Anxiety and cognitive performance: Attentional control theory. Emotion, 7, 336–353.

- Fenouillet, F. , Prokofieva, V., Lorant, S., Masson, J., & Putwain, D. W. (2023). French Study of Multidimensional Test Anxiety Scale in Relation to Performance, Age, and Gender. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment 41(7), 828–834. [CrossRef]

- Gast, D. L. , & Tawney, J. W. (2014). Scientific research in educational and clinical settings. In Single case research methodology (pp. 19-30). Routledge.

- Gibbon, J. , Church, R. M., & Meck, W. H. (1984). Scalar timing in memory. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 423(1), 52–77. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grey, I. , Healy, O., Leader, G., & Hayes, D. (2009). Using a Time Timer™ to increase appropriate waiting behavior in a child with developmental disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 30. [CrossRef]

- Guérin, B. (1983). Social facilitation and social monitoring: A test of three models. British Journal of Social Psychology, 22. [CrossRef]

- Hallez, Q. , & Droit-Volet, S. (2017). High levels of time contraction in young children in dual tasks are related to their limited attention capacities. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 161, 148–160. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallez, Q. , & Droit-Volet, S. (2019). Timing in a dual-task in children and adults: when the interference effect is higher with concurrent non-temporal than temporal information. Journal of Cognitive Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Hallez, Q. , & Droit-Volet, S. (2020). Identification of an age maturity in time discrimination abilities. Timing & Time Perception.

- Hallez, Q. , Mermillod, M., & Droit-Volet, S. (2023). Cognitive and plastic recurrent neural network clock model for the judgment of time and its variations. Scientific Reports 13(1), 3852. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallez, Q. , & Rebecchi, K. (2024). Evaluation and Time Constraint: Impact of Time Processing on Mathematical Performance. The Journal of Experimental Education. [CrossRef]

- Hemmes, N. S. , Brown, B. L., & Kladopoulos, C. N. (2004). Time perception with and without a concurrent nontemporal task. Perception & Psychophysics. [CrossRef]

- Honicke, T. , & Broadbent, J. (2016). The influence of academic self-efficacy on academic performance: A systematic review. Educational Research Review, 17. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S. , & Son, T. (2021). Students' Attitude toward Mathematics and Its Relationship with Mathematics Achievement. Journal of Education and e-Learning Research, 8.

- Irwin-Chase, H. , & Burns, B. (2000). Developmental Changes in Children’s Abilities to Share and Allocate Attention in a Dual Task. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 77. [CrossRef]

- Janeslätt, G. , Kottorp, A., & Granlund, M. (2014). Evaluating intervention using time aids in children with disabilities. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy 21(3), 181–190. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, W. A. , & Dark, V. J. (1986). Selective attention. Annual Review of Psychology 37(1), 43–75. [CrossRef]

- Kanfer, R. , & Ackerman, P. L. (1989). Motivation and cognitive abilities: An integrative/aptitude-treatment interaction approach to skill acquisition. Journal of applied psychology. [CrossRef]

- Korkman, M., Kirk, U., & Kemp, S. (2012). NEPSY II: Manuel d’administration. ECPA – Pearson.

- Li, W. , Lee, A. M., & Solmon, M. A. (2005). Relationships among dispositional ability conceptions, intrinsic motivation, perceived competence, experience, and performance. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 24(1), 51–65. [CrossRef]

- Manly, T., Robertson, I. H., Anderson, V., & Nimmo-Smith, I. (1999). The Test of Everyday Attention for Children (TEA-Ch). Bury St. Edmunds, UK: Thames Valley Test Company.

- McCloskey, G., Perkins, L. A., & Van Diviner, B. (2008). Assessment and intervention for executive function difficulties. Routledge.

- McDonald, A. S. (2001). The Prevalence and Effects of Test Anxiety in School Children. Educational Psychology, 21. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V. , Montout, C., Mura, T., Purper-Ouakil, D., & Lopez-Castroman, J. (2024). Concordance and validity between versions of the ADHD Conners scale for Parents. L'encephale. [CrossRef]

- Nejati, V. , & Yazdani, S. (2020). Time perception in children with attention deficit–hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): Does task matter? A meta-analysis study. Child Neuropsychology, 26. [CrossRef]

- Neufeld, J. , & Stewart, I. (2023). A behavioral approach to the human understanding of time: Relational frame theory and temporal relational framing. The Psychological Record, 73. [CrossRef]

- Nobre, A. C., Nobre, K., & Coull, J. T. (Eds.). (2010). Attention and Time. Oxford University Press, USA.

- OECD (2023), PISA 2022 Results (Volume I): The State of Learning and Equity in Education, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris. [CrossRef]

- Owens, M. , Stevenson, J., Hadwin, J. A., & Norgate, R. (2012). When does anxiety help or hinder cognitive test performance ? The role of working memory capacity. British Journal Of Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Pagán, A. F. , Huizar, Y. P., & Schmidt, A. T. (2023). Conner’s Continuous Performance Test and adult ADHD: A systematic literature review. Journal of Attention Disorders, 27, 231–249.

- Prokofieva, V. , Fenouillet, F., & Romero, M. (2024, October). The effects of assessment instruction and test anxiety on divergent components of creative problem-solving tasks. In Frontiers in Education (Vol. 9, p. 1440248). Frontiers Media SA. [CrossRef]

- Qu, F. , Shi, X., Zhang, A., & Gu, C. (2021). Development of Young Children’s Time Perception : Effect of Age and Emotional Localization. Frontiers In Psychology, 12. [CrossRef]

- Reitan, R. M. (1958). Validity of the Trail Making Test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 8. [CrossRef]

- Roy, A. , Le Gall, D., Roulin, J.-L., & Fournet, N. (2020). Un nouveau dispositif d’évaluation des fonctions exécutives chez l’enfant : la batterie FÉE. ANAE, 167, 393–402.

- Sarason, I. G. (1984). Stress, anxiety and cognitive interference: Reactions to tests. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46. [CrossRef]

- Shi, R. , Sharpe, L., & Abbott, M. (2019). A meta-analysis of the relationship between anxiety and attentional control. Clinical Psychology Review, 72. [CrossRef]

- Stroop, J. R. (1935). Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 18. [CrossRef]

- Sussman, R. F. , & Sekuler, R. (2022). Feeling rushed? Perceived time pressure impacts executive function and stress. [CrossRef]

- Tartas, V. (2010). Le développement de notions temporelles par l'enfant. Développements, 4. [CrossRef]

- Treisman, A. M. (1964). Selective attention in man. British Medical Bulletin.

- Zeidner, M. (1998). Test anxiety: The state of the art. New York: Plenum.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).