1. Introduction

Hip Osteoarthritis is a musculoskeletal disease that progressively degenerates the hip joint and eventually leads to its dysfunction[

1]. The resulting pain causes lateral trunk bending that overloads other parts of the lower limb for compensation [

2]. Gradual deterioration often leads to advanced HOA that generally requires surgical treatment, namely THA. While THA is considered a successful operation that alleviates pain and restores walking functionality in most subjects, it has been pointed out in the literature that improvements do not return to normal post-THA [

3].

Medical imaging is the most common objective method used for diagnosis and therapeutic interventions in osteoarthritis [

4]. However, clinical symptoms are not consistent with results from imaging. In the context of assessing hip functionality, patient-based measures such as the Harris Hip Score, is the accepted standard in the evaluation of the rehabilitation progress post-THA [

5]. Due to the subjective nature of the questionnaires, biases can be introduced by the patient and the raters.

In recent decades, GA has been widely used for the examination of gait alterations based on motion data such as kinematics, kinetics, muscle activations, and spatio-temporal (ST) information. These gait features have known discriminating abilities and has seen applications in sports, security, and health informatics [

6].

In clinical settings, GA is extensively investigated focusing on pathological abnormalities of neuro-muscular and musculoskeletal diseases. Specifically for HOA and THA research related reports, gait classification, severity and progress prediction, and relevant parameter determination are the key focus [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Gait alterations could already be manifested prior to the outset of observable functional impairments, thus discriminating features are important for clinical applicability.

The large volume of information and diversity produced by GA is a prohibitive challenge for clinicians to fully interpret results. Additionally, traditional statistical methods have difficulty in synthesizing non-linear multi-dimensional gait data. To overcome these limitations, ML techniques have been increasingly employed in the analysis of gait data. ML algorithms are known to capture nonlinear patterns and especially its recent subset, DL models can handle big datasets with outstanding accuracy [

11,

12,

13].

In the context of HOA and THA gait research, ML algorithms have been employed to address a wide range of clinical topics. Such applications include determination of best discriminating parameters [

14,

15,

16], discriminating HOA or post-THA gaits with other pathologies [

17,

18,

19], distinguishing between healthy and HOA and/or post-THA gaits [

20,

21], and predicting risks and recovery after THA [

22,

23]. However, there is still hesitancy in acceptance from medical practitioners, as well as gap between development and practice due to the following factors: (1) applicability, which is the relevancy and feasibility of the studies with regards to HOA or THA research trends, (2) results interpretability [

24], which is mapping from input to output and results explanation that can foster trust from users, and (3) reliability, which is the performance, consistency and validity of the ML algorithms being developed for GA.

It is noteworthy to mention that few recent surveys have been published on the application of artificial intelligence in gait analysis for neuromuscular [

25,

26,

27] and musculoskeletal diseases [

28]. Jiao et al. [

26] focused on the automatic classification system for post-stroke gaits while Kohnehshahri et al. [

27] provided a comprehensive survey for cerebral palsy and stroke survivor subjects. Both survey papers have focused on ML methodologies as a data-driven technique in the analysis of gait patterns. Likewise, Franco et al. [

25] surveyed papers that applied DL and GA in Parkinson’s Disease for classification, diagnosis, and monitoring. Reviewed papers were categorized into gait acquisition method, namely wearable sensors and video capture. The common difficulty realized in these surveys was clinical utility and interpretability which limits application to real-world applications. Conspicuously, only a single musculoskeletal-related survey was published that investigated gait-related modifications after post-knee surgery through ML framework [

28]. Even so, only six articles were included in the survey, all of which focused on classification task utilizing non-DL methods while five articles are conducted on subjects after post-total knee arthroplasty.

Notably, to the best knowledge of the authors, no reviews have been conducted for HOA or post-THA gaits. Thus, the aim of this review is to examine reports that utilize ML techniques in HOA and post-THA subjects using biomechanical data from GA. By providing a comprehensive review of the current state of the field, benefits and limitations can be appraised thus providing information for future direction.

2. Methods

This systematic review follows the PRISMA guidelines in the selection of papers [

29].

2.1. Search Strategy

Databases were judiciously selected, based on their discipline, to improve search results. As such, two technological databases namely IEEE Xplore and ACM Digital Library, and two medical databases namely Embase and PubMed were selected. Additionally, Scopus was added for search as a hybrid of technological and medical databases. PICO strategy [

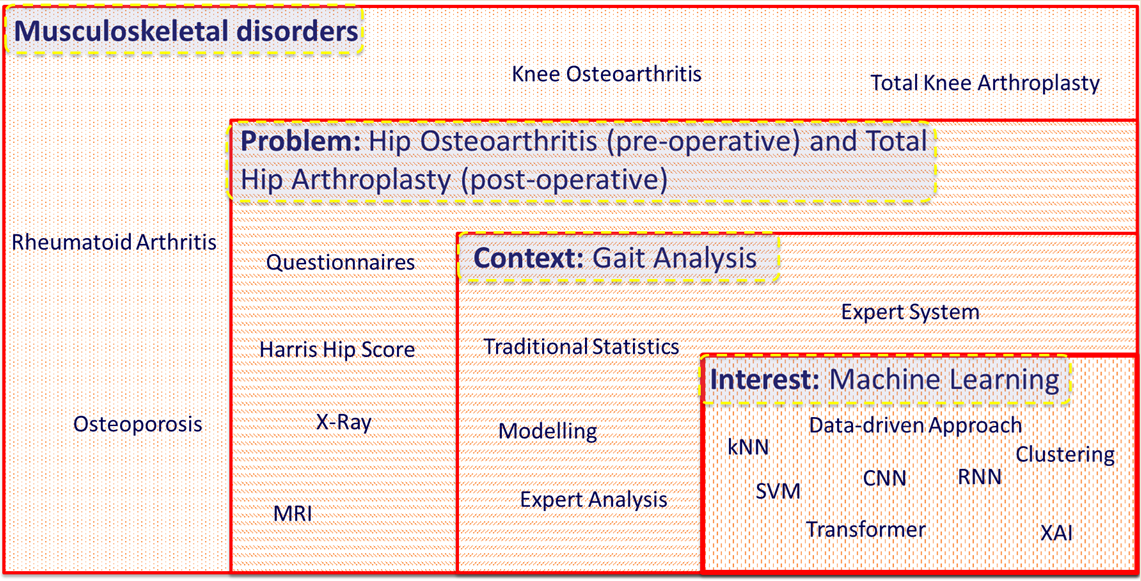

29] is utilized to formulate the search terms with Problem: HOA or THA, Interest: Machine Learning, and COntext: Gait Analysis. To comply with each database’s syntax requirements, the search string is adapted as shown in. The final search was completed on May 4, 2025. All identified reports are uploaded to Endnote 21 for screening and review.

Table 1.

Search String.

| Database |

Search Terms |

| PubMed |

(“osteoarthritis, hip”[MeSH Terms] OR “arthroplasty, replacement, hip”[MeSH Terms] OR “Hip Prosthesis”[MeSH Terms]) AND (“walking”[MeSH Terms] OR “gait”[MeSH Terms]) AND (“machine learning”[MeSH Terms] OR “classification”[MeSH Terms] OR “prediction algorithms”[MeSH Terms] OR “cluster analysis”[MeSH Terms] OR “Regression Analysis”[MeSH Terms] OR “Biometric Identification”[MeSH Terms]) |

| Embase |

(((‘hip osteoarthritis’)/exp) OR ((‘hip arthroplasty’)/exp) OR ((‘hip replacement’)/exp) OR ((‘hip prosthesis’)/exp)) AND (((‘walking’)/exp) OR ((‘gait’)/exp)) AND (((‘machine learning’)/exp) OR ((‘classification’)/exp) OR ((‘predictive model’)/exp) OR ((‘cluster analysis’)/exp) OR ((‘regression model’)/exp) OR ((‘biometry’)/exp)) |

| IEEE Xplore |

(“All Metadata”: “hip osteoarthritis” OR “All Metadata”: “hip arthroplasty” OR “All Metadata”: “hip replacement” OR “All Metadata”: “hip prosthesis”) AND (“All Metadata”: “walking” OR “All Metadata”: “gait”) AND (“All Metadata”: “machine learning” OR “All Metadata”: “deep learning” OR “All Metadata”: “classification” OR “All Metadata”: “prediction” OR “All Metadata”: “clustering” OR “All Metadata”: “regression” OR “All Metadata”: “biometric”) |

| ACM Digital Library |

[[All: “hip osteoarthritis”] OR [All: “hip arthroplasty”] OR [All: “hip replacement”] OR [All: “hip prosthesis”]] AND [[All: “walking”] OR [All: “gait”]] AND [[All: “machine learning”] OR [All: “deep learning”] OR [All: “classification”] OR [All: “prediction”] OR [All: “cluster”] OR [All: “regression”] OR [All: “biometric”]] |

| Scopus |

TITLE-ABS-KEY((“hip osteoarthritis” OR “hip arthroplasty” OR “hip replacement” OR “hip prosthesis”) AND (“walking” OR “gait”) AND (“machine learning” OR “deep learning” OR “classification” OR “prediction algorithm” OR “clustering analysis” OR “regression model” OR “biometrics information”)) |

2.2. Screening Method

Two reviewers independently screened identified articles in a two-step process: (1) Title and Abstract, and (2) Full-Text using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. At the end of each step, any discrepancies were addressed through face-to-face meeting with a third reviewer. Covidence software, a standard web-based tool for systematic reviews, is utilized in the study which streamlines the process, ensures effective collaboration through shared real-time system, and reduces risk of bias.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To determine relevance of the identified reports on the objectives of this review, specific inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied. Included studies require to satisfy the following conditions:

Studies that focus on HOA and THA on human subjects

Studies using artificial intelligence in the realm of ML and DL

Studies from January 2000 to May 04, 2025

Studies that deal with the analysis of gait utilizing input parameters such as kinematics, kinetics, ST, EMG, and vision data.

Thereafter, studies are excluded with the following conditions:

Studies that simulate HOA or post-THA gaits

Studies involving robot rehabilitation or prosthetic legs

Studies focusing on other musculoskeletal diseases (e.g., knee osteoarthritis)

Studies with input parameters that are not gait related

Non-English studies

2.4. Data Extraction

A single reviewer is tasked to extract data utilizing Covidence extraction template based on the PICO strategy as shown in

Table 2. In addition, general information such as authors’ names, institution, country, and publication year was also extracted.

2.5. Quality Assessment

Two reviewers assessed the quality of the included reports based on a set of questions through the RoB 2 tool (Risk of Bias) using the information acquired from extracted data. To properly synthesize the proposed methods, extracted data are categorized into reliability, applicability, and interpretability as described in Error! Reference source not found.. An article is considered of high quality for a given category if a majority of its domains are met.

Table 3.

Quality Assessment Description.

Table 3.

Quality Assessment Description.

| Domain |

Category |

Description |

| Dataset Information |

Reliability |

High Quality: > 100, demographic explained and balanced |

| |

|

Low Quality: < 50, demographic not summarized and unbalanced |

| ML Algorithm |

Reliability, Interpretability |

High Quality: Justification provided, feasible and ML interpretable/explainable |

| |

|

Low Quality: no justification, not interpretable, or not feasible |

| Validation Process |

Reliability |

High Quality: externally validated and/or validation clearly defined |

| |

|

Low Quality: no validation protocol |

| Performance and assessment |

Reliability and Applicability |

High quality: appropriate and >3 metrics, accuracy > 90%, error < 0.05, and confusion matrix described |

| |

|

Low quality: inappropriate or < 3 metrics, accuracy < 80%, error > 0.1, and confusion matrix not shown |

| Results |

Applicability and Reliability |

High Quality: benchmarked with other published studies and/or provide value to the state-of-the-art. |

| |

|

Low Quality: No benchmark or comparison |

| Study Design |

Applicability |

High Quality: appropriate study design and aims clearly stated |

| |

|

Low Quality: inappropriate study design and aims not clearly stated |

| Modality |

Applicability |

High Quality: data collection method described and (input features described or justified) |

| |

|

Low Quality: data collection not described; sensors not feasible |

| Input Features |

Applicability and Interpretability |

High Quality: input features described or justified and interpretable |

| |

|

Low Quality: data collection not described and/or not interpretable |

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

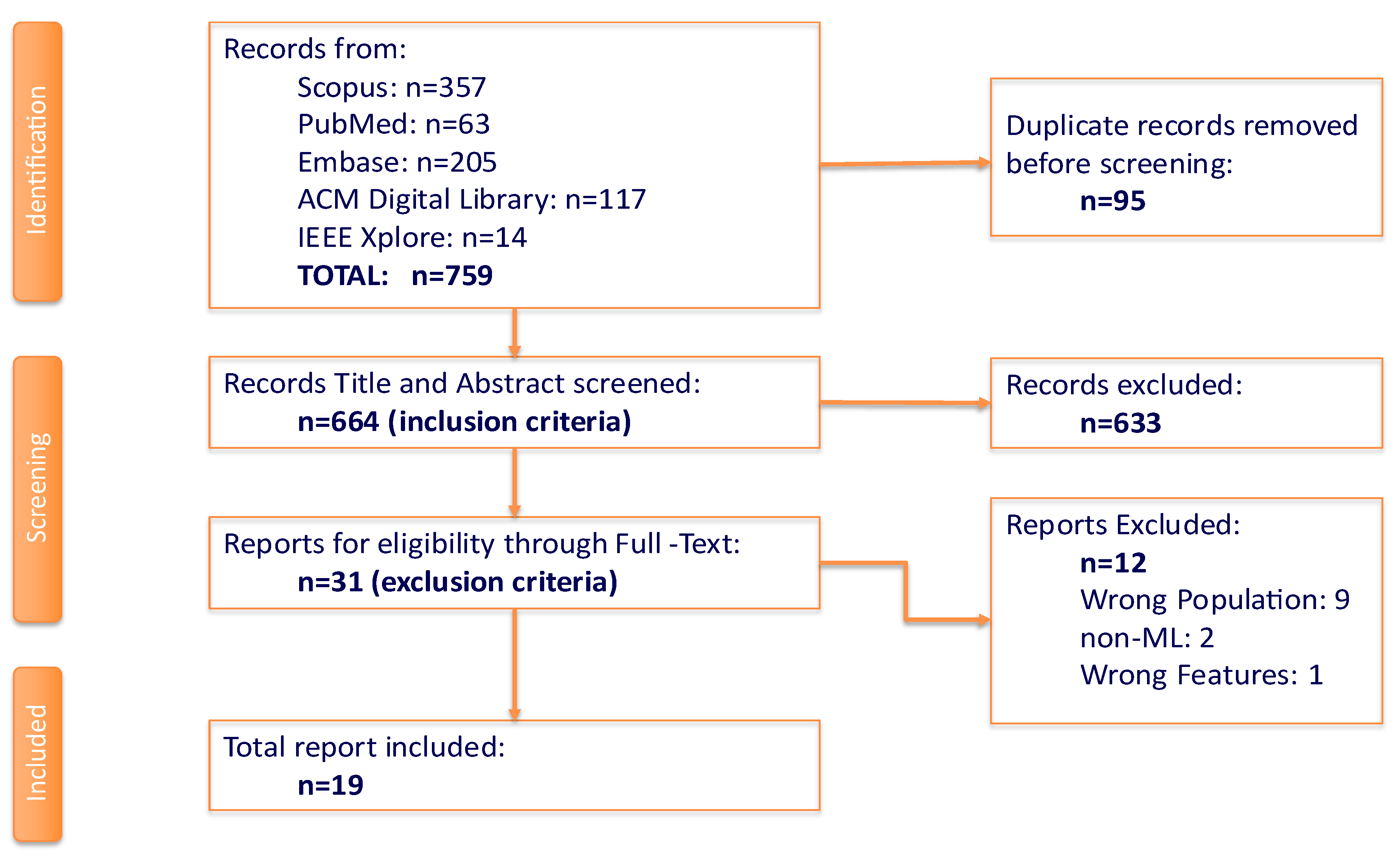

Figure 1 summarizes the workflow to achieve this systematic review. Initial search generated 759 articles: 375 from Scopus, 63 from PubMed, 205 from Embase, 117 from ACM Digital Library, and 14 from IEEE Xplore. Ninety-five duplicates were automatically removed by the Covidence software leaving 664 articles to be screened.

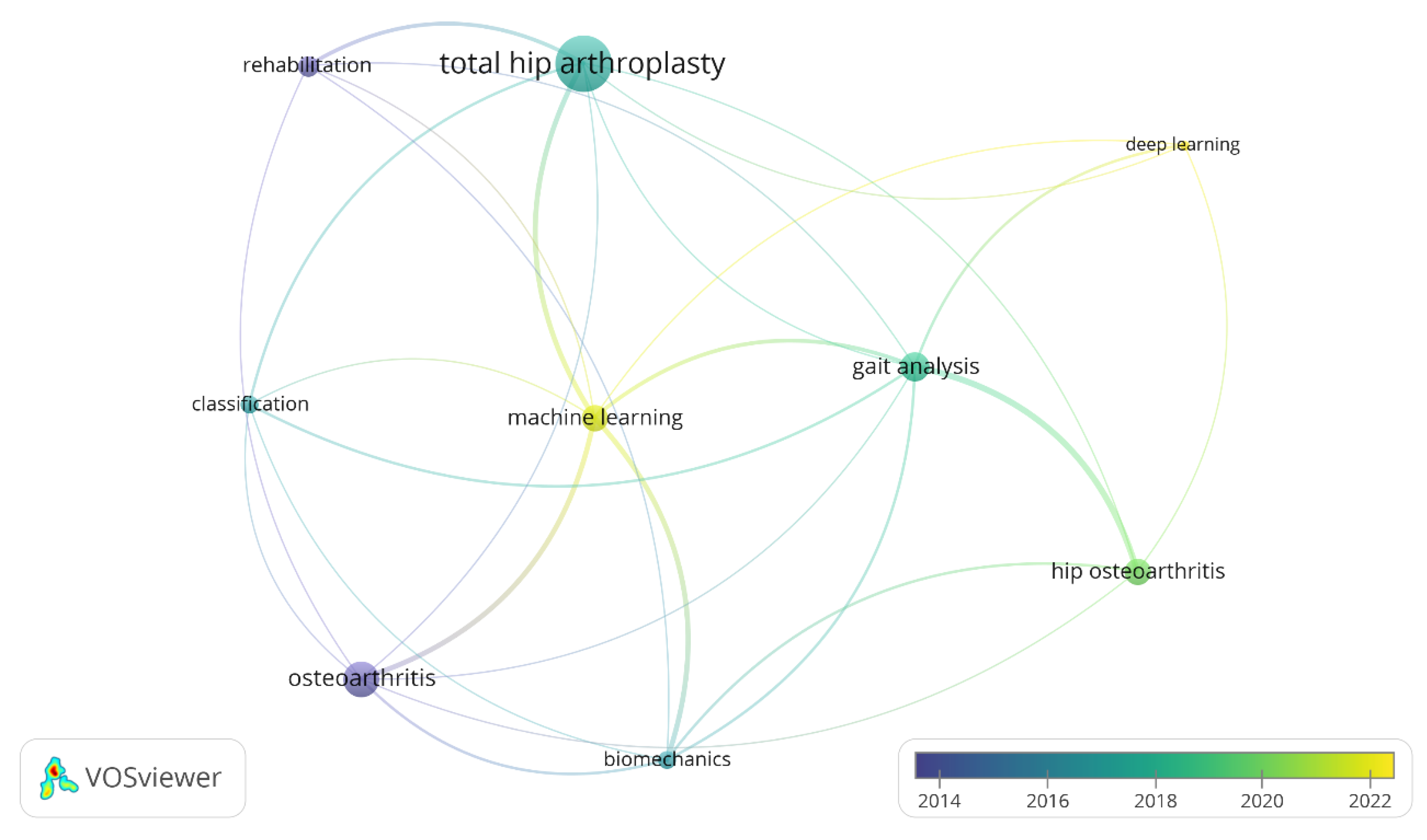

To understand the relationship between keywords used in the search, a visualization of similarities through VOSviewer

1 is designed as shown

Figure 2. Evidently, THA is the most extensively researched topic while DL and ML are the most recent. Also, strong connections are seen for ML on THA, GA, and HOA subjects demonstrating clear relations among these keywords for the papers screened on this review.

Two independent reviewers screened the titles and abstracts of the remaining articles based on the inclusion criteria of which 31 reports were eligible for full-text review. In the event of overlapping authorship, the said reviewer is not involved in any of the steps for the appraisal of the report. Subsequently, a single reviewer was tasked to download the eligible reports of which are available and accessible. Ten reports have met disagreements in vote, and with the involvement of a third reviewer, eight and two reports were excluded and included respectively in the next stage. A total of 12 reports were excluded with 9 as wrong population, 2 as non-ML method used, and a single report with incorrect input features utilized. A tally of 19 articles was finalized for data extraction and quality assessment.

3.2. Data Extraction

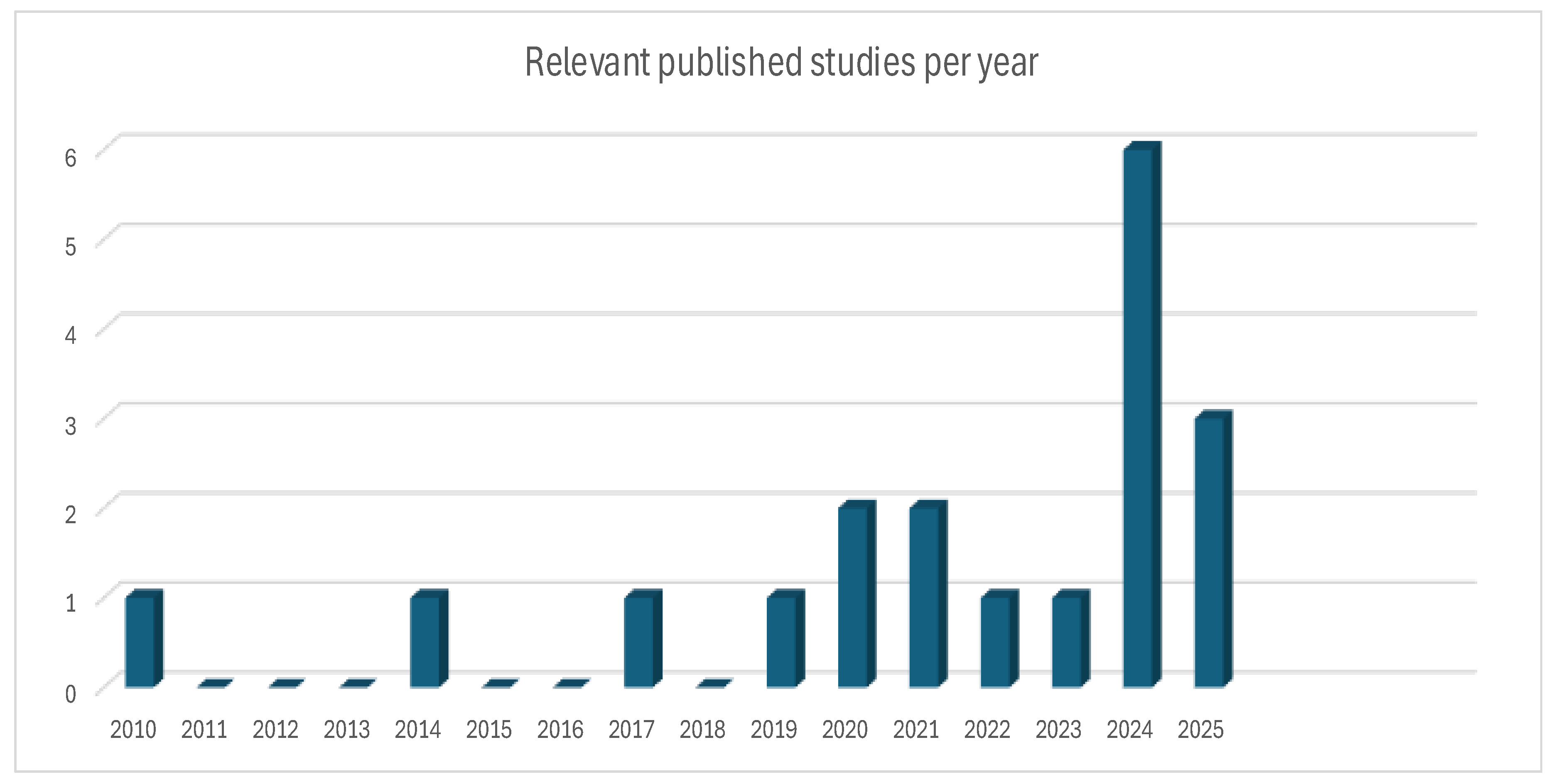

Out of the 19 included articles, 15 of these were published in the past 5 years with majority just in the recent couple of years as presented in

Figure 3. As such, DL methodologies were also introduced in these recent years[

15,

16,

30].

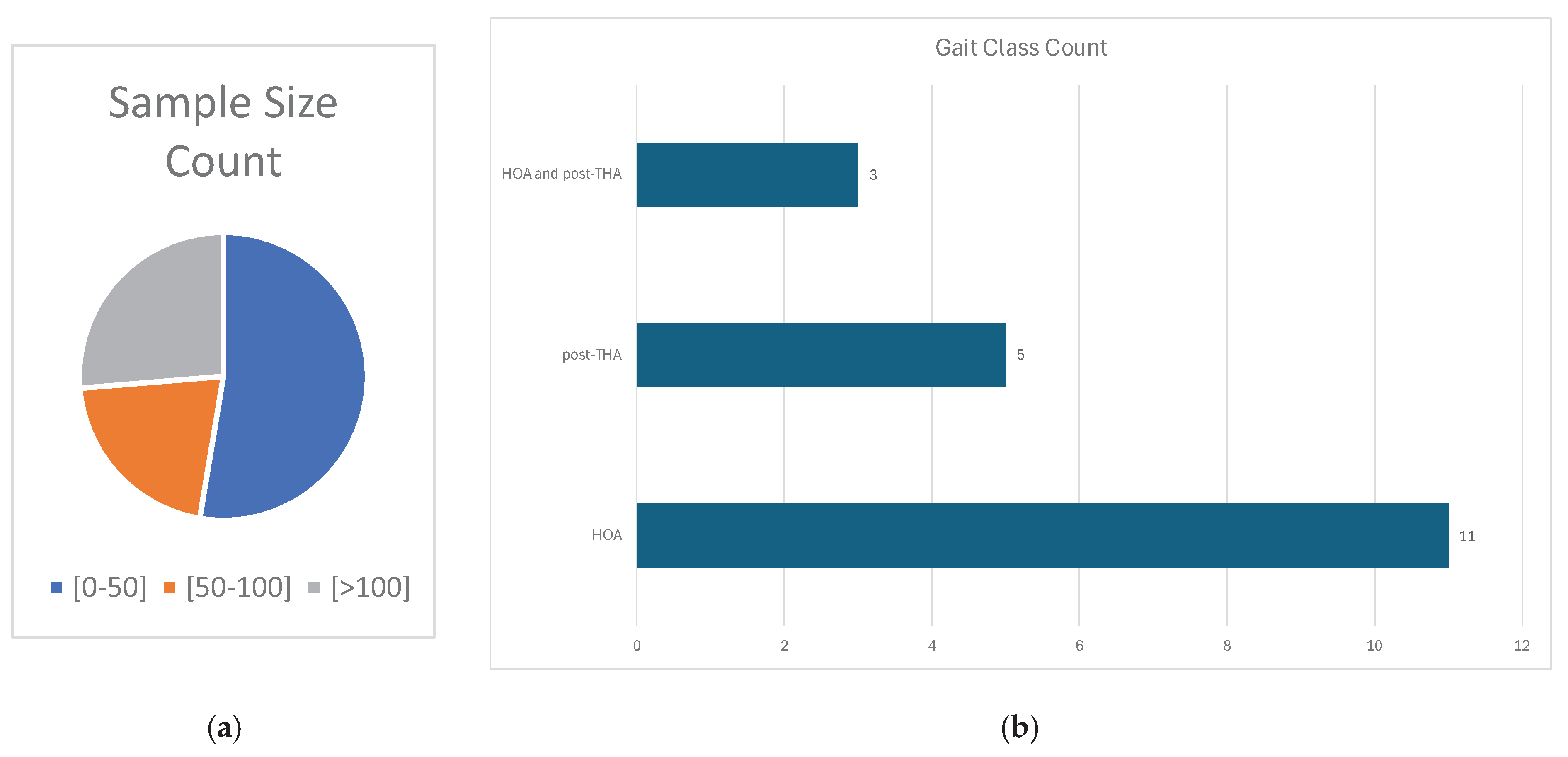

3.2.1. Dataset Information

Majority of the included studies employed a small number of participants with 10 articles utilizing 50 or less participants [

14,

17,

20,

21,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. Notably, 5 studies had sample sizes of 100 or more participants [

15,

16,

19,

36,

37] incorporating at least 1000 events for gait analysis. Information about sampling is summarized in

Figure 4a. Four articles have not elaborated the participants’ demographics [

17,

19,

20,

23] while three articles matched age and BMI of the participants for the classes [

14,

31,

38] and same number of articles have controlled gender-ratio [

18,

31,

32]. On the other hand, only two articles have utilized a public dataset [

39] that consists of healthy, and patients before and after THA operation [

15,

16].

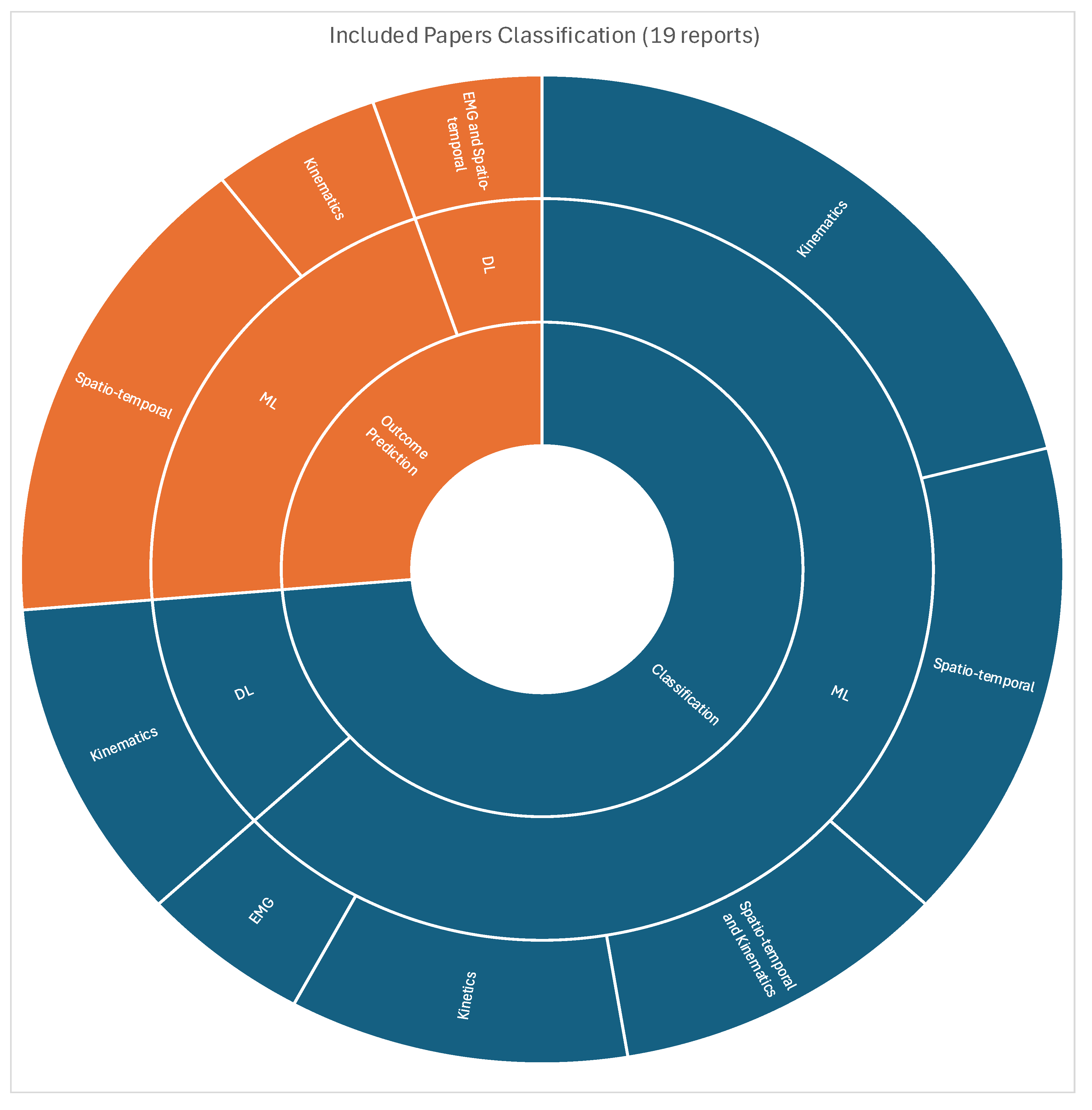

3.2.2. Problem Classification

Fourteen of the studies were classification tasks [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

31,

32,

34,

35,

36,

38] with 5 studies solely focused on the diagnosis of HOA gaits [

14,

15,

18,

31,

32]. Conspicuously, Choi et al. [

32] employed clustering method to further classify HOA gaits on severity levels. Four other studies focused on predicting outcomes of THA surgery through binary classification [

21,

34,

35], and multi-label classification with healthy and HOA gaits [

16]. Particularly, only Ghaffari et al. aimed at finding gait pattern differences between hip and knee osteoarthritis [

18].

The other five studies were prediction tasks [

22,

23,

30,

33,

37] with a variety of objectives. Cornish et al. [

30] predicted hip contact forces and kinematic angles of HOA subjects using EMG and pose estimates through vision-based marker-less system. Miyazaki et al. [

37] predicted gait patterns before and after THA surgery that is important for locomotive syndrome. Dindorf et al. [

33] predicted the most significant parameters of post-THA gaits and dimensionality reduction methods were employed. Additionally, Polus et al. [

22] predicted risk of fall for THA patients while Surmacz et al. [

23] predicted the recovery of patients after THA operation.

Figure 4b shows that only three studies have considered both HOA and post-THA gaits in their article [

16,

22,

37] while five studies focused only on post-THA gaits [

21,

23,

33,

34,

35].

3.2.3. Modality and Input Feature

Nine articles have utilized state-of-the-art 3-Dimensional Gait Analysis (3DGA) [

14,

15,

16,

19,

30,

31,

32,

33,

37] that may consist of optical cameras, inertial measurement units (IMU), force plates, and bipolar surface electrodes to accurately measure gait parameters. Seven articles only require wearable sensors of which a majority are IMU [

21,

33,

34,

35,

36,

38]. Interestingly, two recent studies only need the use of smartphones to acquire gait information[

22,

23] while another recent study proposed the use of marker-less vision-based system [

20].

Consequently, nine studies utilized kinematic parameters [

14,

15,

16,

18,

21,

33,

34,

35,

36], another nine studies employed ST parameters [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

30,

37,

38], two articles exclusively used kinetic parameters [

31,

32], and two articles have employed muscle activation information through electromyography (EMG) [

17,

30]. Feature extraction and selection was performed and explicitly discussed in ten articles [

19,

20,

21,

22,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38] and which is the main focus of a single study conducted by Miyazaki et al. [

37].

3.2.4. Machine Learning Algorithm

Majority of the included papers, 16 in total, utilized traditional ML or non-DL methods except for three recent papers [

15,

16,

30]. For these traditional ML methods, the most popular algorithm used is support vector machine (SVM) [

14,

19,

20,

21,

22,

31,

34,

35,

36,

38]. Other ML algorithms such as k-Nearest Neighbor (kNN) [

18,

19,

31,

38], random forest (RF) [

31,

33,

34], decision trees (DT) [

38], Fuzzy Inference System (FIS) [

19], and several types of regression models [

17,

23,

38] were also considered.

Seven articles conducted a comparable study on several ML methods [

17,

19,

22,

30,

31,

34,

38]. Notably, the article by Choi et al. [

32] is the only unsupervised methodology utilizing k-means clustering algorithm. For DL models, only long short-term memory (LSTM) and convolutional neural networks (CNN) were considered [

15,

16,

30]. On the other hand, interpretability and explainability concepts for ML methods were only examined in two articles [

34,

35].

Hyperparameter tuning was mentioned in in seven articles [

15,

16,

17,

18,

30,

36,

38] albeit only two papers explicitly discussed the method used: grid search by Ghaffari et al. [

18] and hyperband algorithm by Cornish et al. [

30].

Figure 5 describes the hierarchical extracted data according to problem classification, ML method, and input feature categories.

3.2.5. Performance and Validation

With the exception of Miyazaki et al. [

37] study on feature importance prediction, the rest of the articles have split their dataset into at least two groups, training set, validation set, and/or test set. Of these articles, ten studies have held out a set or group, explicitly not seen in training, for performance: test set [

16,

17,

18,

20,

23,

36], leave-one-subject-out (LOSO) [

30], leave-one-group-out (LOGO) [

22,

33], and other classes [

35]. Eleven studies employed some form of k-fold cross validation (CV) [

14,

15,

17,

19,

21,

22,

23,

31,

34,

36,

38], trained the dataset iteratively to find the best performing model.

Accuracy is the most adopted performance measure among the studies with a few exception articles: symmetric mean absolute percentage error (SMAPE) [

32], mean-square error (MSE) [

30], and cumulative contribution [

37]. Other performance measures, such as sensitivity, specificity, recall, and precision, were also added for further performance analysis of the developed model.

Apart from the recent DL-related studies, SVM is found to have the highest performance among the traditional ML methods [

19,

22,

33,

38] within 70-100%. DL models [

15,

16,

30] consistently provides superior performance with accuracy above 95% as reported in the articles.

3.2.6. Results Interpretation

In terms of ST parameters, gait speed is the most reported with the highest discriminating feature [

19,

20,

23,

38] followed by stride time [

19,

38]. For kinematic parameters, the sagittal hip angle is the highest discriminating feature as reported by eight articles [

14,

15,

16,

21,

32,

33,

34,

35] and followed by the sagittal angle of the knee [

14,

16,

33,

34,

35]. Subsequently, Nair et al. [

17] utilized EMG information and reported gluteus medialis as the most important muscle for classification during loading and mid-stance. The summary of extracted data for classification and prediction tasks are presented in

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6 and

Table 7.

3.3. Quality Assessment

Table 8 summarizes the quality assessment results of the reviewed articles in this study. Only one study had adequately achieved all quality categories [

34]. In the context of reliability, ten articles sufficiently addressed the hurdles [

15,

16,

22,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

37,

38]. Conspicuously, only two studies explicitly addressed interpretability [

34,

35] while all but two studies have adequately addressed concerns on applicability [

23,

31].

4. Discussion

The aim of this literature review is to examine ML method on gait information concerned with HOA and THA subjects. The intent of this section is to synthesize the results based on the previous section’s quality assessment expounding on key characteristics: dataset information, model validation and evaluation, model algorithm selection or design, interpretability and explainability, and feature identification.

4.1. Dataset Information

Firstly, the quantity and quality of data is the most important factor for reliability. Thus far, a sufficiently large and diverse dataset, in most studies included, is lacking. Fourteen studies utilizing less than a hundred participants. While there is no standard in the size of dataset, a relatively small sample size adversely affects the generalizability of ML algorithms for precise prediction of unforeseen data [

40]. To mitigate this issue, multiple trials are conducted for each participant, thus artificially increasing the dataset, but this can introduce bias and overfitting.

With regards to post-THA gait reports, measurements are conducted between 2-weeks to 6-months. A standardized time to conduct the measurement is strongly recommended as it can potentially enhance reliability in benchmarking comparison for the effectiveness of treatment and the performance of prediction capabilities of ML algorithms as well.

The most comprehensive and publicly available dataset was provided by Bertaux et al. [

39] quite recently. This fully described 3DGA dataset is composed of 80 healthy individuals and 106 patients with unilateral HOA before and after THA operation. The use of a publicly available dataset allows researchers to contribute to common bodies of knowledge and algorithm validation can be easily done through comparison of performance. Consequently, the kinematic information of the dataset has been used for the development of DL models [

15,

16] on classification problems. In addition, healthy, pre- and post-THA gait classes in one protocol is necessary for ML models to identify severity outcomes and provide insights into the effects of treatment [

11].

For ML research purposes, it is highly recommended to have another independent publicly accessible dataset that also contains pre-THA and post-THA gait data. Thus, results can be validated on the effects of treatment and rehabilitation. To achieve this, close collaboration with relevant institutions is necessary.

On the other hand, data quality is tied to data acquisition, diversity, and class balancing. Primarily, data acquisition has a significant contribution to quality, thus a complete description is necessary. Variability of marker or IMU placements by clinicians on anatomical landmarks can greatly affect reliability and robustness of raw measurements. The error can be introduced between subjects or before and after operation. Notably, less than half of the articles included were able to achieve this.

Subsequently, most of the included studies have provided generic demographic descriptions of the participants (gender, age, height, weight, etc.) describing limited diversity compounded with class imbalance that can lead to a risk of bias towards the majority class [

40]. Thus, dataset matching is crucial to improve generalizability of ML models. Arguably, data availability may not be known beforehand, thus dataset matching is an ongoing challenge towards deployment and application. To address this issue, generative artificial intelligence has been proposed recently as an effective method in data augmentation for ML models [

41]. Synthetic data are created with validation from domain experts to enhance dataset diversity.

4.2. Model Validation and Evaluation

Majority of the studies adopted CV methods to address overfitting, especially dealing with small datasets. LOSO or LOGO CV methods are widely accepted and recommended to evaluate models in terms of generalizability [

42] which is only considered in three studies [

22,

30,

33]. Moreover, as model training is achieved through iterative process, only a single study [

16] has explicitly split the dataset into three holding a test set for a final evaluation. Thus, most studies are vague in their model tuning approach.

It should be noted that all ML models considered in this review are tested and trained on the same dataset thus limiting its generalizability as samples have high comparability [

4]. A thorough external validation of ML models is necessary to ensure reliability before it can be considered for clinical utilization [

43]. Still significant barriers are seen on region-related differences such as institution policies in patient selection, demography and culture, and environment. A common protocol with the same ML platform could potentially address this issue.

While accuracy has been employed as the primary performance metric in most studies, other important metrics such as sensitivity, specificity, precision, and recall, are important as well for clinical utility. These other metrics were considered in eleven studies providing indicators on how a model performs with false predictions which are relevant in the medical context. A full confusion matrix of the results is also recommended to provide a whole picture of the performance [

44].

4.3. ML Algorithm Selection and Design

Several ML algorithms were considered in the study with SVM classifiers as the most popular being used in ten studies, generally the best performing model among traditional ML with reported accuracy of 70-100%. Noticeably, two similar articles [

34,

35] on post-THA gait classification reported perfect accuracy but closer scrutiny reveals small sample size suggesting prediction over-fitting. It should be noted that relatively earlier reports tend to have small sample size affecting the developed model’s generalizability.

Quite recently, DL framework has been proposed and has shown superior performance mainly due to its data-driven approach, as compared to traditional ML models, in related fields that require pattern recognition [

45]. Besides, it is a feature extracting architecture with attributes learned from its hidden layers. Thus, eliminating this time-consuming stage that oftentimes requires some handcrafting of features. In the past couple of years, three articles from the included reports have proposed DL methods for classification of before and after THA gaits [

15,

16], and prediction of HCF for HOA subjects [

30], respectively. The former achieved above 95% performance across features and benchmarked with previous classification studies employing SVM [

14,

21] which demonstrates its outstanding results. Otherwise, the latter is the first study to predict HCF, kinematic and kinetic information as well using ML methods achieving minimal errors and results in agreement with neuromusculoskeletal modelling.

On the other hand, a single study [

32] utilized an unsupervised learning model through k-means clustering analysis from GRF measurements of healthy subjects and HOA patients. Interestingly, it is revealed that gait patterns of HOA patients can be grouped into two clusters. The first cluster is similar to a healthy gait pattern and could require strengthening exercise while the second cluster is markedly different from the other clusters that points to hip replacement possibility or more stringent gait training. Additionally, this is the only study that attempts to correlate with KL severity grade of HOA.

It is noteworthy that this review reveals a palpable gap in feasibility studies in terms of computational and memory requirements. While hardware constraints are mostly settled in the recent decade with the introduction of cloud-edge computing and the use of graphics processing unit (GPU) [

46], a conscious consideration of this requirement can significantly improve practicality and effectiveness in real-world clinical applications.

4.4. Interpretability and Explainability

As more DL methods are applied in GA, it is evident that performance has reached its ceiling. However, the lack of prediction transparency and explainability [

24] is becoming a major hindrance for its practical application in clinical setting. The ‘black-box’ nature of ML methods makes their decision-making opaque due to unknown input – output mapping on the hidden layer leading to poor understanding of predictions.

To address this issue, Dindorf et al. [

34] explored explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) concepts to examine the influence of input representation on SVM model accuracy in the gait classification of healthy and after THA subjects. Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations (LIME) was used for the interpretation task and found that derived or intermediate features improve performance at the expense of interpretability. While the authors explicitly recommended combining different input representations, this may not be beneficial eventually due to unclear connections. Instead, it is advantageous to exploit DL methods with XAI to obtain optimum performance while not sacrificing interpretability.

Consequently, the same research group [

35] further investigated XAI to examine relevant gait features that lead to successful classification decision utilizing permutation feature importance algorithm [

47]. The selected input features were common. Discrete gait kinematic parameters, such as the sagittal hip trajectory, instead of abstract sensor, or transformed data, therefore providing clinicians with valuable interpretable information.

Efforts to increase transparency of DL models in the context of GA are still active ongoing research [

48,

49] with attention-based DL algorithms [

50] becoming popular with the use of attention maps to visualize hidden layers’ relationships providing transparent prediction outcomes. It is recommended that future ML algorithms not only provide accurate results but meaningful and interpretable information as well. Deeper insights into the gait events of joint kinematics and muscle activation parameters can guide clinicians with decision-making for suitable treatment strategies.

4.5. Feature Identification

Feature extraction and selection is an integral part of ML algorithm design to improve prediction performance. Yet, in the context of HOA gait studies, a pending research task is the determination of significant features that describe HOA or THA.

Regarding ST gait parameters, articles included aimed to corroborate results from previous analytical studies through supervised methods. While gait speed and stride time were found to be the most important features [

19,

20,

38], there are other parameters reported that could be relevant and needs some research. Accordingly, the study by Miyazaki et al. [

37] focused on predicting the most significant ST gait parameters for subjects who underwent unilateral THA due to HOA through PCA. Among 16 parameters, there are three components identified that account for more than 90% of contribution namely walking ability, stance phase, and asymmetry of support time. Multiple linear regression analysis further reveals that these are the most influential factors for clinical decisions.

Likewise, there is a positive development towards consensus on the identification of kinematic outcomes that can be utilized for the diagnosis and prediction for HOA patients. Kinematic trajectories from the sagittal plane of hip, knee, and foot are considered to be significantly relevant [

14,

15,

16,

32,

34,

35]. Aside from the trajectory itself, it is important for clinical applications to determine the gait event that leads to the correct prediction. This type of feature selection has been explored by Teufl et al.[

21] but it is recommended to utilize the whole kinematic trajectory as a feature and an interpretable method be able to detect the most important event in that single gait cycle. Hence, input feature can be mapped to output prediction providing explanation to the resulting classification.

Furthermore, a less explored gait feature is based on EMG patterns of muscle activation. Nair et al. [

17] investigated ML techniques in the classification of healthy and arthritic, both HOA and rheumatoid arthritis, subjects. While simple ML algorithms were employed more than a decade ago, with gluteus medialis muscles identified as important, it would be interesting to see existing DL frameworks applied to EMG patterns for validation of these results and further identify relevant but hidden patterns.

From these results, it is clear that utilizing a multi-modal system in a common ML platform is beneficial. Kinetic waveforms can be augmented to other parameters, potentially providing explanation to relevancy of gait events. Additionally, discarded features may hold clinical significance and it could be correlated with established and more prominent gait attributes. Interdependencies between features have potential to be discovered and verified providing crucial information for personalized rehabilitation strategies and further enhancing applicability of ML models.

Conversely, two articles in this review have not utilized clinical datasets and instead smartphones are employed to gather gait information in the real world to predict outcomes of THA operation. Polus et al. [

22] developed a fall risk prediction model based while Surmacz et al. [

23] a multi-class model for the prediction of recovery and rehabilitation based only on gait speed. These real-world applications are the next steps in monitoring patients outside of the clinical setting.

5. Conclusions

ML algorithms reveal promising results in gait analysis to classify and predict medical conditions of individuals with HOA and/or post-THA operation. Majority of the reviewed articles were published in the past five years underscored the evolving nature of the research field.

With recent advancements in DL framework, classification studies are achieving superior performance heading towards reliable platforms. Reports on the identification of key gait parametric outcomes are reaching a consensus which can improve HOA diagnosis and follow-up conditions in post-THA subjects. However, small sample sizes, adequate validation processes, and lack of focus on multi-class studies utilizing pre- and post-THA gaits in a single protocol are ongoing challenges that considerably affect clinical utility and generalizability. Further research on synthetic gait data through generative models is our research direction to mitigate these limitations. Another key characteristic that needs to be addressed is the interpretability of proposed ML models which have been seldom explored. Future research activities should explore XAI and attention-based models that provide information on the hidden layers thus increasing transparency.

The findings of this systematic review improve understanding of the current state of ML research in the context of gait analysis applied to HOA and post-THA subjects. Further identification of relevant gait parameters for clinical applications, and exploration of interpretable and reliable ML models can be instrumental for accurate treatment decision-making and optimal rehabilitation strategies.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used Conceptualization, R.P. (Roel Pantonial) and M.S. (Milan Simic).; methodology, R.P.; validation, R.P., M.S. and M.O. (Mohammed Salih); investigation, R.P. and M.O..; writing—original draft preparation, R.P..; writing—review and editing, R.P., M.O. and M.S..; supervision, M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data was created.

Acknowledgments

The first author Mr. Roel Pantonial acknowledges Research Training Program scholarship, funded by Australian Government for support in the study and research in the Development of New AI methodologies on gait analysis for biomedical, sports, and other applications. Authors also acknowledge Associate Professor Milena Simic Co-Lead of the Neuro-Musculoskeletal Research Collaborative Central Sydney (Patyegarang) Precinct, The University of Sydney, Discipline of Physiotherapy | School of Health Sciences | Faculty of Medicine and Health, for initial guidance and consultation in medical domain and PRISMA methodology for conducting Systematic Review

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ornetti, P.; Maillefert, J.-F.; Laroche, D.; Morisset, C.; Dougados, M.; Gossec, L. Gait analysis as a quantifiable outcome measure in hip or knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review. Jt. Bone Spine 2010, 77, 421–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. W. Whittle, Gait analysis: an introduction. Butterworth-Heinemann, 2014.

- Beaulieu, M.L.; Lamontagne, M.; Beaulé, P.E. Lower limb biomechanics during gait do not return to normal following total hip arthroplasty. Gait Posture 2010, 32, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, A.; Chen, H.; Chen, T.; Li, J.; Lu, S.; Fan, T.; Zeng, D.; Wen, Z.; Ma, J.; Hunter, D.; et al. The application of machine learning in early diagnosis of osteoarthritis: a narrative review. Ther. Adv. Musculoskelet. Dis. 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Park, S.J.; Gim, J.-A.; Kang, Y.J.; Choi, S.H.; Seo, S.H.; Kim, S.J.; Kim, S.C.; Kim, H.S.; Yoo, J.-I. Correlation between Harris hip score and gait analysis through artificial intelligence pose estimation in patients after total hip arthroplasty. Asian J. Surg. 2023, 46, 5438–5443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepas-Moghaddam, A.; Etemad, A. Deep Gait Recognition: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2022, 45, 264–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Constantinou, M.; Loureiro, A.; Carty, C.; Mills, P.; Barrett, R. Hip joint mechanics during walking in individuals with mild-to-moderate hip osteoarthritis. Gait Posture 2017, 53, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leigh, R.J.; Osis, S.T.; Ferber, R. Kinematic gait patterns and their relationship to pain in mild-to-moderate hip osteoarthritis. Clin. Biomech. 2016, 34, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longworth, J.A.; Chlosta, S.; Foucher, K.C. Inter-joint coordination of kinematics and kinetics before and after total hip arthroplasty compared to asymptomatic subjects. J. Biomech. 2018, 72, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujii, J.; Aoyama, S.; Tezuka, T.; Kobayashi, N.; Kawakami, E.; Inaba, Y. Prediction of Change in Pelvic Tilt After Total Hip Arthroplasty Using Machine Learning. J. Arthroplast. 2022, 38, 2009–2016.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Galarraga, O.; Garcia-Salicetti, S.; Vigneron, V. Deep Learning for Quantified Gait Analysis: A Systematic Literature Review. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 138932–138957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharthi, A.S.; Yunas, S.U.; Ozanyan, K.B. Deep Learning for Monitoring of Human Gait: A Review. IEEE Sensors J. 2019, 19, 9575–9591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, L.B.; Helmick, C.G.; Schwartz, T.A.; Renner, J.B.; Tudor, G.; Koch, G.G.; Dragomir, A.D.; Kalsbeek, W.; Luta, G.; Jordan, J.M. One in four people may develop symptomatic hip osteoarthritis in his or her lifetime. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2010, 18, 1372–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, D.; Tolambiya, A.; Morisset, C.; Maillefert, J.; French, R.; Ornetti, P.; Thomas, E. A classification study of kinematic gait trajectories in hip osteoarthritis. Comput. Biol. Med. 2014, 55, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantonial, R.; Simic, M. Transfer Learning Method for the Classification of Hip Osteoarthritis using Kinematic Gait Parameters. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 246, 4692–4701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantonial, R.; Simic, M. Novel Deep Learning Method in Hip Osteoarthritis Investigation Before and After Total Hip Arthroplasty. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, S.S.; French, R.M.; Laroche, D.; Thomas, E. The Application of Machine Learning Algorithms to the Analysis of Electromyographic Patterns From Arthritic Patients. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabilitation Eng. 2009, 18, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaffari, A.; Clasen, P.D.; Boel, R.V.; Kappel, A.; Jakobsen, T.; Rasmussen, J.; Kold, S.; Rahbek, O. Multivariable model for gait pattern differentiation in elderly patients with hip and knee osteoarthritis: A wearable sensor approach. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altilio, R.; Paoloni, M.; Panella, M. Selection of clinical features for pattern recognition applied to gait analysis. Med Biol. Eng. Comput. 2016, 55, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghidotti, A.; Regazzoni, D.; Rizzi, C.; Fiorentino, G. Applying Machine Learning to Gait Analysis Data for Hip Osteoarthritis Diagnosis. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2025, 324, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teufl, W.; Taetz, B.; Miezal, M.; Lorenz, M.; Pietschmann, J.; Jöllenbeck, T.; Fröhlich, M.; Bleser, G. Towards an Inertial Sensor-Based Wearable Feedback System for Patients after Total Hip Arthroplasty: Validity and Applicability for Gait Classification with Gait Kinematics-Based Features. Sensors 2019, 19, 5006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polus, J.S.; Bloomfield, R.A.; Vasarhelyi, E.M.; Lanting, B.A.; Teeter, M.G. Machine Learning Predicts the Fall Risk of Total Hip Arthroplasty Patients Based on Wearable Sensor Instrumented Performance Tests. J. Arthroplast. 2021, 36, 573–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surmacz, K.; Redfern, R.E.; Van Andel, D.C.; Kamath, A.F. Machine learning model identifies patient gait speed throughout the episode of care, generating notifications for clinician evaluation. Gait Posture 2024, 114, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. T. Ribeiro, S. Singh, and C. Guestrin, ““ Why should i trust you?” Explaining the predictions of any classifier,” in Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining, 2016, pp. 1135-1144.

- Franco, A.; Russo, M.; Amboni, M.; Ponsiglione, A.M.; Di Filippo, F.; Romano, M.; Amato, F.; Ricciardi, C. The Role of Deep Learning and Gait Analysis in Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review. Sensors 2024, 24, 5957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, Y.; Hart, R.; Reading, S.; Zhang, Y. Systematic review of automatic post-stroke gait classification systems. Gait Posture 2024, 109, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F. S. Kohnehshahri, A. F. S. Kohnehshahri, A. Merlo, D. Mazzoli, M. C. Bò, and R. Stagni, “Machine learning applied to gait analysis data in cerebral palsy and stroke: A systematic review,” Gait & Posture, 2024.

- Kokkotis, C.; Chalatsis, G.; Moustakidis, S.; Siouras, A.; Mitrousias, V.; Tsaopoulos, D.; Patikas, D.; Aggelousis, N.; Hantes, M.; Giakas, G.; et al. Identifying Gait-Related Functional Outcomes in Post-Knee Surgery Patients Using Machine Learning: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 20, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gotzsche, P.C.; A Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009, 339, b2700–b2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornish, B.M.; Pizzolato, C.; Saxby, D.J.; Xia, Z.; Devaprakash, D.; Diamond, L.E. Hip contact forces can be predicted with a neural network using only synthesised key points and electromyography in people with hip osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2024, 32, 730–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.; Choi, W.; Jeong, H.; Oh, S.; Jung, T.-D. One-Step Gait Pattern Analysis of Hip Osteoarthritis Patients Based on Dynamic Time Warping through Ground Reaction Force. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.; Jeong, H.; Oh, S.; Jung, T.-D. Instant gait classification for hip osteoarthritis patients: a non-wearable sensor approach utilizing Pearson correlation, SMAPE, and GMM. Biomed. Eng. Lett. 2025, 15, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dindorf, C.; Teufl, W.; Taetz, B.; Becker, S.; Bleser, G.; Fröhlich, U. Feature extraction and gait classification in hip replacement patients on the basis of kinematic waveform data. Biomed. Hum. Kinet. 2021, 13, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dindorf, C.; Teufl, W.; Taetz, B.; Bleser, G.; Fröhlich, M. Interpretability of Input Representations for Gait Classification in Patients after Total Hip Arthroplasty. Sensors 2020, 20, 4385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teufl, W.; Taetz, B.; Miezal, M.; Dindorf, C.; Fröhlich, M.; Trinler, U.; Hogan, A.; Bleser, G. Automated detection and explainability of pathological gait patterns using a one-class support vector machine trained on inertial measurement unit based gait data. Clin. Biomech. 2021, 89, 105452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dammeyer, C.; Nüesch, C.; Visscher, R.M.S.; Kim, Y.K.; Ismailidis, P.; Wittauer, M.; Stoffel, K.; Acklin, Y.; Egloff, C.; Netzer, C.; et al. Classification of inertial sensor-based gait patterns of orthopaedic conditions using machine learning: A pilot study. J. Orthop. Res. 2024, 42, 1463–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyazaki, S.; Fujii, Y.; Tsuruta, K.; Yoshinaga, S.; Hombu, A.; Funamoto, T.; Sakamoto, T.; Tajima, T.; Arakawa, H.; Kawaguchi, T.; et al. Spatiotemporal gait characteristics post-total hip arthroplasty and its impact on locomotive syndrome: a before-after comparative study in hip osteoarthritis patients. PeerJ 2024, 12, e18351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almuhammadi, W.S.; Agu, E.; King, J.; Franklin, P. OA-Pain-Sense: Machine Learning Prediction of Hip and Knee Osteoarthritis Pain from IMU Data. Informatics 2022, 9, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertaux, A.; Gueugnon, M.; Moissenet, F.; Orliac, B.; Martz, P.; Maillefert, J.-F.; Ornetti, P.; Laroche, D. Gait analysis dataset of healthy volunteers and patients before and 6 months after total hip arthroplasty. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halilaj, E.; Rajagopal, A.; Fiterau, M.; Hicks, J.L.; Hastie, T.J.; Delp, S.L. Machine learning in human movement biomechanics: Best practices, common pitfalls, and new opportunities. J. Biomech. 2018, 81, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dindorf, C.; Dully, J.; Konradi, J.; Wolf, C.; Becker, S.; Simon, S.; Huthwelker, J.; Werthmann, F.; Kniepert, J.; Drees, P.; et al. Enhancing biomechanical machine learning with limited data: generating realistic synthetic posture data using generative artificial intelligence. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1350135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staudenmayer, J.; Zhu, W.; Catellier, D.J. Statistical Considerations in the Analysis of Accelerometry-Based Activity Monitor Data. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2012, 44, S61–S67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.S.; Chan, P.K.; Wen, C.; Fung, W.C.; Cheung, A.; Chan, V.W.K.; Cheung, M.H.; Fu, H.; Yan, C.H.; Chiu, K.Y. Artificial intelligence in diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis and prediction of arthroplasty outcomes: a review. Arthroplasty 2022, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavazza, L.; Morasca, S. Common Problems With the Usage of F-Measure and Accuracy Metrics in Medical Research. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 51515–51526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. LeCun, Y. Bengio, and G. Hinton, “Deep learning,” nature, vol. 521, no. 7553, pp. 436-444, 2015.

- Kennedy, J.; Sharma, V.; Varghese, B.; Reaño, C. Multi-Tier GPU Virtualization for Deep Learning in Cloud-Edge Systems. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 2023, 34, 2107–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, A.; Rudin, C.; Dominici, F. All Models are Wrong, but Many are Useful: Learning a Variable’ s Importance by Studying an Entire Class of Prediction Models Simultaneously. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2019, 20, 1–81. [Google Scholar]

- Hosain, T.; Jim, J.R.; Mridha, M.; Kabir, M. Explainable AI approaches in deep learning: Advancements, applications and challenges. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2024, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slijepcevic, D.; Horst, F.; Lapuschkin, S.; Horsak, B.; Raberger, A.-M.; Kranzl, A.; Samek, W.; Breiteneder, C.; Schöllhorn, W.I.; Zeppelzauer, M. Explaining Machine Learning Models for Clinical Gait Analysis. ACM Trans. Comput. Heal. 2021, 3, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Vaswani et al., “Attention is all you need,” Advances in neural information processing systems, vol. 30, 2017.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).