Submitted:

15 October 2025

Posted:

16 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Results

2.1. Clinical Evaluation and MRS metabolites

2.2. Neuropsychiatric Evaluation and MRS metabolites

2.3. Neuropsychological Assessment and MRS metabolites

Discussion

Materials and Methods

Participants

Subjects’ Assessment

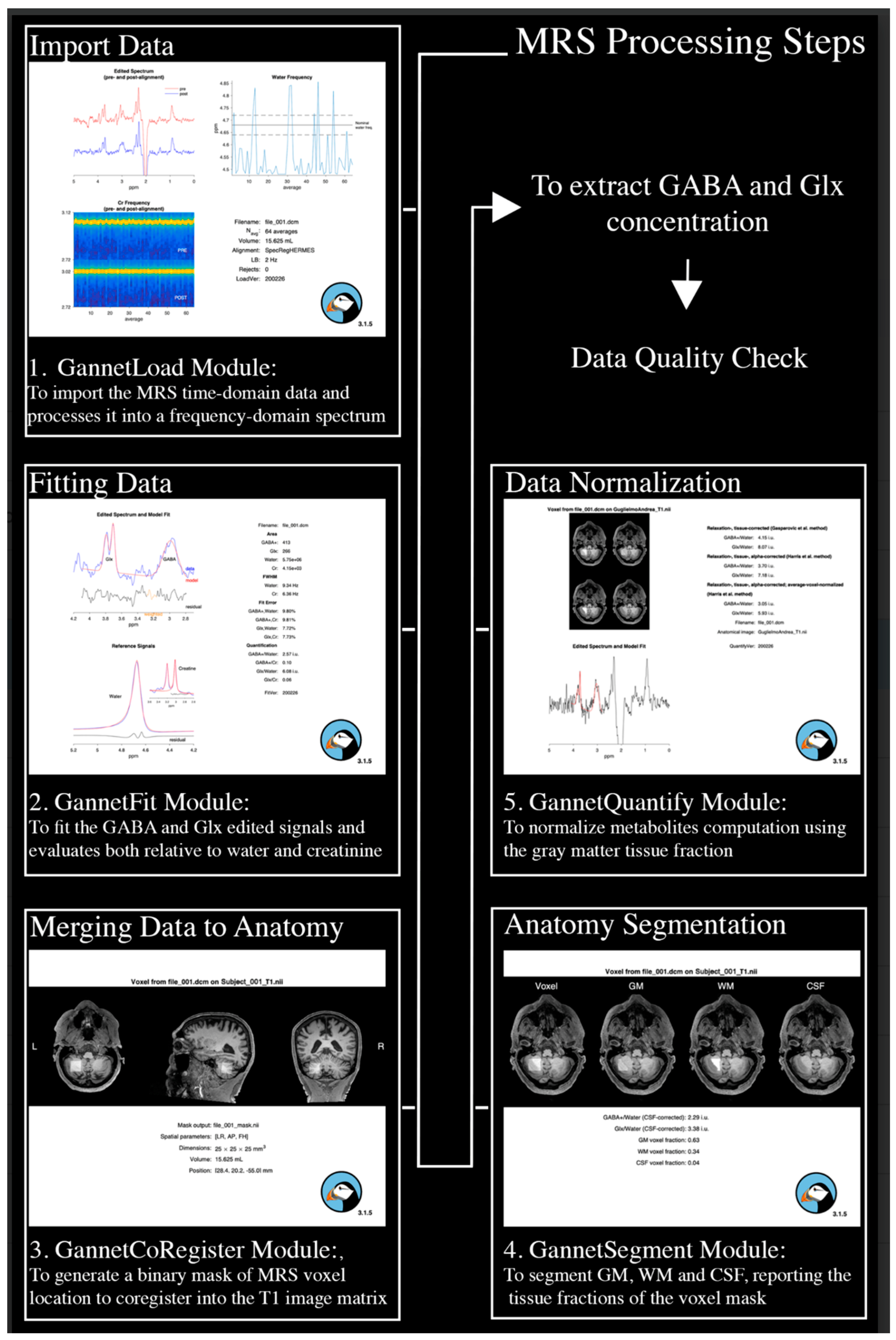

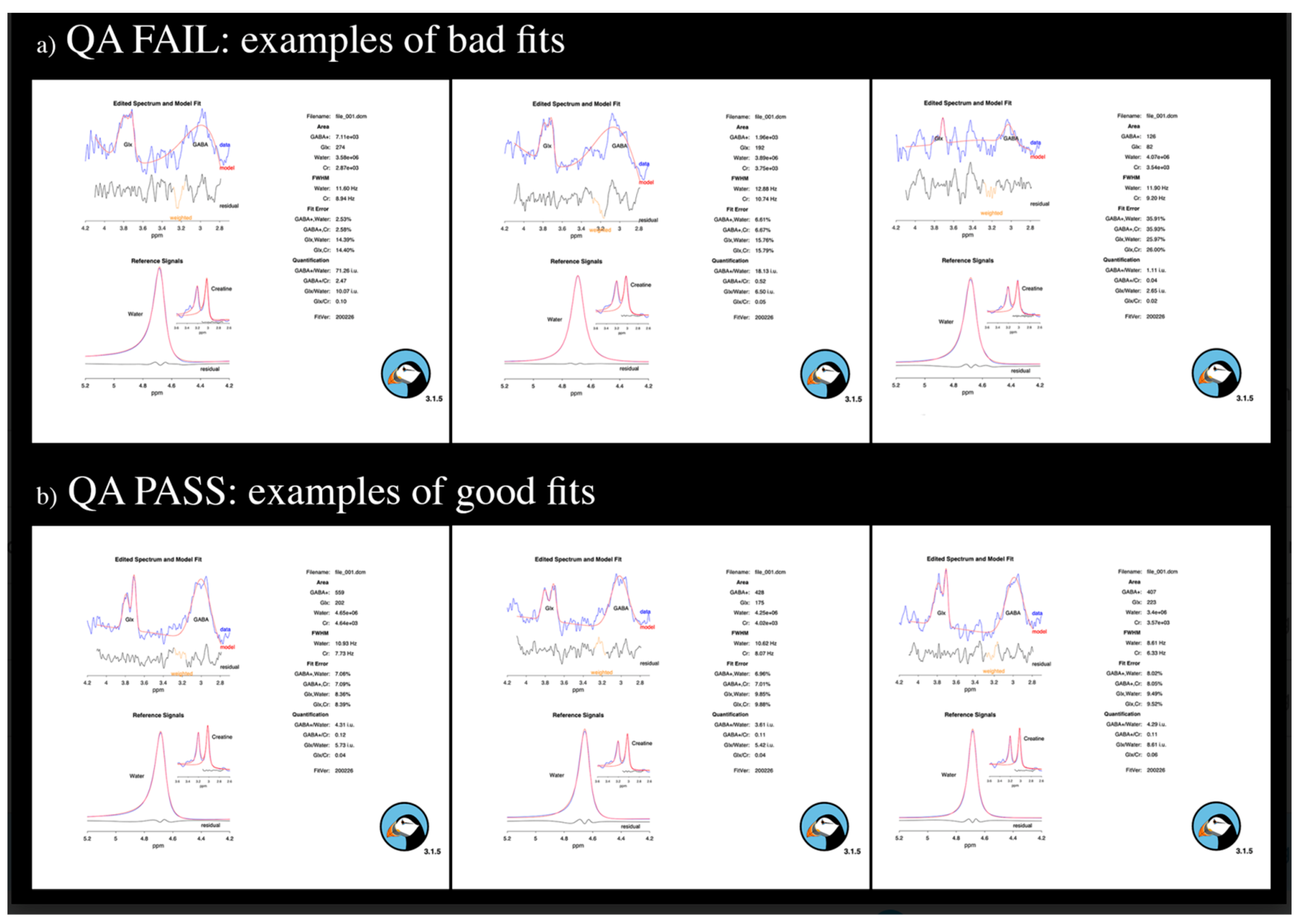

Neuroimaging Procedure

Statistical Analyses

Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bostan, A.C.; Strick, P.L. The Cerebellum and Basal Ganglia Are Interconnected. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2010, 20, 261–270. [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Le, W.; Jankovic, J. Linking the Cerebellum to Parkinson Disease: An Update. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2023, 19, 645–654. [CrossRef]

- Kerestes, R.; Laansma, M.A.; Owens-Walton, C.; Perry, A.; van Heese, E.M.; Al-Bachari, S.; Anderson, T.J.; Assogna, F.; Aventurato, Í.K.; van Balkom, T.D.; et al. Cerebellar Volume and Disease Staging in Parkinson’s Disease: An ENIGMA-PD Study. Mov. Disord. 2023, 38, 2269–2281. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dan, X.; Hu, Y.; Sun, J.; Gao, L.; Zhou, Y.; Ma, J.; Doyon, J.; Wu, T.; Chan, P. Altered Cerebellar Resting-State Functional Connectivity in Early-Stage Parkinson’s Disease Patients With Cognitive Impairment. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 678013. [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Mattis, P.; Tang, C.; Perrine, K.; Carbon, M.; Eidelberg, D. Metabolic Brain Networks Associated with Cognitive Function in Parkinson’s Disease. Neuroimage 2007, 34, 714–723. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solstrand Dahlberg, L.; Lungu, O.; Doyon, J. Cerebellar Contribution to Motor and Non-Motor Functions in Parkinson’s Disease: A Meta-Analysis of FMRI Findings. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.H.; Chen, B.; He, J.Q.; Qi, Y.M.; Yan, Y.Y.; Jin, S.X.; Chang, Y. Patterns of Cerebellar Cortex Hypermetabolism on Motor and Cognitive Functions in PD. npj Park. Dis. 2025, 11, 83. [CrossRef]

- Buddhala, C.; Loftin, S.K.; Kuley, B.M.; Cairns, N.J.; Campbell, M.C.; Perlmutter, J.S.; Kotzbauer, P.T. Dopaminergic, Serotonergic, and Noradrenergic Deficits in Parkinson Disease. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2015, 2, 949–959. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiesman, A.I.; da Silva Castanheira, J.; Fon, E.A.; Baillet, S.; PREVENT-AD Research Group; Quebec Parkinson Network Structural and Neurophysiological Alterations in Parkinson’s Disease Are Aligned with Cortical Neurochemical Systems. medRxiv Prepr. Serv. Heal. Sci. 2023, 2023.04.04.23288137. [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, B.; Al-kuraishy, H.M.; Al-Gareeb, A.I.; Elekhnawy, E.; Alharbi, H.; Alexiou, A.; Papadakis, M.; Batiha, G.E.S. Role of GABA Pathway in Motor and Non-Motor Symptoms in Parkinson’s Disease: A Bidirectional Circuit. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2024, 29. [CrossRef]

- Steel, A.; Mikkelsen, M.; Edden, R.A.E.; Robertson, C.E. Regional Balance between Glutamate+glutamine and GABA+ in the Resting Human Brain. Neuroimage 2020, 220. [CrossRef]

- Fortel, I.; Zhan, L.; Ajilore, O.; Wu, Y.; Mackin, S.; Leow, A. Disrupted Excitation-Inhibition Balance in Cognitively Normal Individuals at Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2023, 95, 1449–1467. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, P.W.; Lui, S.S.Y.; Hung, K.S.Y.; Chan, R.C.K.; Chan, Q.; Sham, P.C.; Cheung, E.F.C.; Mak, H.K.F. In Vivo Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid and Glutamate Levels in People with First-Episode Schizophrenia: A Proton Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy Study. Schizophr. Res. 2018, 193, 295–303. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, C.E.; Ratai, E.M.; Kanwisher, N. Reduced GABAergic Action in the Autistic Brain. Curr. Biol. 2016, 26, 80–85. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasanta, D.; He, J.L.; Ford, T.; Oeltzschner, G.; Lythgoe, D.J.; Puts, N.A. Functional MRS Studies of GABA and Glutamate/Glx – A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2023, 144. [CrossRef]

- Klietz, M.; Bronzlik, P.; Nösel, P.; Wegner, F.; Dressler, D.W.; Dadak, M.; Maudsley, A.A.; Sheriff, S.; Lanfermann, H.; Ding, X.Q. Altered Neurometabolic Profile in Early Parkinson’s Disease: A Study with Short Echo-Time Whole Brain MR Spectroscopic Imaging. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10. [CrossRef]

- Piras, F.; Vecchio, D.; Assogna, F.; Pellicano, C.; Ciullo, V.; Banaj, N.; Edden, R.A.E.; Pontieri, F.E.; Piras, F.; Spalletta, G. Cerebellar GABA Levels and Cognitive Interference in Parkinson’s Disease and Healthy Comparators. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Högl, B.; Stefani, A.; Videnovic, A. Idiopathic REM Sleep Behaviour Disorder and Neurodegeneration - An Update. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2018, 14, 40–56. [CrossRef]

- Iranzo, A.; Fernández-Arcos, A.; Tolosa, E.; Serradell, M.; Molinuevo, J.L.; Valldeoriola, F.; Gelpi, E.; Vilaseca, I.; Sánchez-Valle, R.; Lladó, A.; et al. Neurodegenerative Disorder Risk in Idiopathic REM Sleep Behavior Disorder: Study in 174 Patients. PLoS One 2014, 9. [CrossRef]

- Galbiati, A.; Verga, L.; Giora, E.; Zucconi, M.; Ferini-Strambi, L. The Risk of Neurodegeneration in REM Sleep Behavior Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Studies. Sleep Med. Rev. 2019, 43, 37–46. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fereshtehnejad, S.M.; Yao, C.; Pelletier, A.; Montplaisir, J.Y.; Gagnon, J.F.; Postuma, R.B. Evolution of Prodromal Parkinson’s Disease and Dementia with Lewy Bodies: A Prospective Study. Brain 2019, 142, 2051–2067. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, S.V.; Libourel, P.A.; Lazarus, M.; Grassi, D.; Luppi, P.H.; Fort, P. Genetic Inactivation of Glutamate Neurons in the Rat Sublaterodorsal Tegmental Nucleus Recapitulates REM Sleep Behaviour Disorder. Brain 2017, 140, 414–428. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goetz, C.G.; Tilley, B.C.; Shaftman, S.R.; Stebbins, G.T.; Fahn, S.; Martinez-Martin, P.; Poewe, W.; Sampaio, C.; Stern, M.B.; Dodel, R.; et al. Movement Disorder Society-Sponsored Revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS): Scale Presentation and Clinimetric Testing Results. Mov. Disord. 2008, 23, 2129–2170. [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, M. The Assessment Of Anxiety Rating Scale. Br. J. Med. Psychol. 1959, 32, 50–55. [CrossRef]

- Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G.K. Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio 1966, 78, 490–498.

- Robert, P.H.; Claire, S.; Benoit, M.; Koutaich, J.; Bertogliati, C.; Tible, O.; Caci, H.; Borg, M.; Brocker, P.; Bedoucha, P. The Apathy Inventory: Assessment of Apathy and Awareness in Alzheimer’s Disease, Parkinson’s Disease and Mild Cognitive Impairment. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2002. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagby, R.M.; Taylor, G.J.; Parker, J.D.A. The Twenty-Item Toronto Alexithymia Scale-II. Convergent, Discriminant, and Concurrent Validity. J. Psychosom. Res. 1994, 38, 33–40. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlesimo, G.A.; Caltagirone, C.; Gainotti, G.; Facida, L.; Gallassi, R.; Lorusso, S.; Marfia, G.; Marra, C.; Nocentini, U.; Parnett, L. The Mental Deterioration Battery: Normative Data, Diagnostic Reliability and Qualitative Analyses of Cognitive Impairment. Eur. Neurol. 1996, 36, 378–384. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, H.E. A Modified Card Sorting Test Sensitive to Frontal Lobe Defects. Cortex 1976, 12, 313–324. [CrossRef]

- Caffarra, P.; Vezzadini, G.; Dieci, F.; Zonato, F.; Venneri, A. A Short Version of the Stroop Test: Normative Data in an Italian Population Sample. Nuova Riv. di Neurol. 2002, 12, 111–115.

- Osterrieth, P.A. Le Test de Copie d’une Figure Complexe; Contribution à l’étude de La Perception et de La Mémoire. Arch. Psychol. (Geneve). 1944.

- Carlesimo, G.A.; Buccione, I.; Fadda, L.; Graceffa, A.; Mauri, M.; Lorusso, S.; Bevilacqua, G.; Caltagirone, C. Standardizzazione Di Due Test Di Memoria per Uso Clinico: Breve Racconto e Figura Di Rey. Nuova Riv. di Neurol. 2002, 12, 1–13.

- Song, Y.; Gong, T.; Xiang, Y.; Mikkelsen, M.; Wang, G.; Edden, R.A.E. Single-Dose L-Dopa Increases Upper Brainstem GABA in Parkinson’s Disease: A Preliminary Study. J. Neurol. Sci. 2021, 422. [CrossRef]

- Takashima, H.; Terada, T.; Bunai, T.; Matsudaira, T.; Obi, T.; Ouchi, Y. In Vivo Illustration of Altered Dopaminergic and GABAergic Systems in Early Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Terkelsen, M.H.; Hvingelby, V.S.; Pavese, N. Molecular Imaging of the GABAergic System in Parkinson’s Disease and Atypical Parkinsonisms. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2022, 22, 867–879. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Nuland, A.J.M.; den Ouden, H.E.M.; Zach, H.; Dirkx, M.F.M.; van Asten, J.J.A.; Scheenen, T.W.J.; Toni, I.; Cools, R.; Helmich, R.C. GABAergic Changes in the Thalamocortical Circuit in Parkinson’s Disease. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2020, 41, 1017–1029. [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Ai, K.; Zhang, B.; Lui, S. The Immediate Alteration of Cerebellar Glx/GABA and Cerebello-Thalamo-Cortical Connectivity in Patients with Schizophrenia after Cerebellar TMS. Schizophrenia 2025, 11, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Herold, C.J.; Cheung, E.F.C.; Chan, R.C.K.; Schröder, J. Neurological Soft Signs and Brain Network Abnormalities in Schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 2020, 46, 562–571. [CrossRef]

- Lozza, C.; Baron, J.C.; Eidelberg, D.; Mentis, M.J.; Carbon, M.; Marié, R.M. Executive Processes in Parkinson’s Disease: FDG-PET and Network Analysis. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2004, 22, 236–245. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firbank, M.J.; Parikh, J.; Murphy, N.; Killen, A.; Allan, C.L.; Collerton, D.; Blamire, A.M.; Taylor, J.P. Reduced Occipital GABA in Parkinson Disease with Visual Hallucinations. Neurology 2018, 91, e675–e685. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, C.; Chen, Z.; Cai, M.; Zhang, P.; Li, H.; Chen, X.; Qi, Q.; Yang, R.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; et al. Cerebellar Large-Scale Network Connectivity in Parkinson’s Disease: Associations with Emotion, Cognition, and Aging Effects. Brain Imaging Behav. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chau, S.W.; Chan, J.W.; Chu, W.C.; Abrigo, J.M.; Mok, V.C.; Wing, Y.K. Large-Scale Network Dysfunction in α-Synucleinopathy: A Meta-Analysis of Resting-State Functional Connectivity. eBioMedicine 2022, 77. [CrossRef]

- Bansal, K.; Cattaneo, Z.; Oldrati, V.; Ferrari, C.; Grossman, E.D.; Garcia, J.O. A Modulator of Cognitive Function: Cerebellum Modifies Human Cortical Network Dynamics via Integration. bioRxiv 2024, 2024.09.12.612716. [CrossRef]

- Iranzo, A.; Santamaria, J.; Pujol, J.; Moreno, A.; Deus, J.; Tolosa, E. Brainstem Proton Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy in Idopathic REM Sleep Behavior Disorder. Sleep 2002, 25, 867–870. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, G.; Ueki, Y.; Oishi, N.; Oguri, T.; Fukui, A.; Nakayama, M.; Sano, Y.; Kandori, A.; Kan, H.; Arai, N.; et al. Nigrostriatal Dopaminergic Dysfunction and Altered Functional Connectivity in Rem Sleep Behavior Disorder with Mild Motor Impairment. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 435662. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dauvilliers, Y.; Schenck, C.H.; Postuma, R.B.; Iranzo, A.; Luppi, P.H.; Plazzi, G.; Montplaisir, J.; Boeve, B. REM Sleep Behaviour Disorder. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2018, 4, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Brooks, P.L.; Peever, J.H. Impaired GABA and Glycine Transmission Triggers Cardinal Features of Rapid Eye Movement Sleep Behavior Disorder in Mice. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 7111–7121. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assogna, F.; Liguori, C.; Cravello, L.; Macchiusi, L.; Belli, C.; Placidi, F.; Pierantozzi, M.; Stefani, A.; Mercuri, B.; Izzi, F.; et al. Cognitive and Neuropsychiatric Profiles in Idiopathic Rapid Eye Movement Sleep Behavior Disorder and Parkinson’s Disease. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Honeycutt, L.; Gagnon, J.F.; Pelletier, A.; Montplaisir, J.Y.; Gagnon, G.; Postuma, R.B. Characterization of Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms in Idiopathic REM Sleep Behavior Disorder. J. Parkinsons. Dis. 2021, 11, 1409–1416. [CrossRef]

- Vacca, M.; Assogna, F.; Pellicano, C.; Chiaravalloti, A.; Placidi, F.; Izzi, F.; Camedda, R.; Schillaci, O.; Spalletta, G.; Lombardo, C.; et al. Neuropsychiatric, Neuropsychological, and Neuroimaging Features in Isolated REM Sleep Behavior Disorder: The Importance of MCI. Sleep Med. 2022, 100, 230–237. [CrossRef]

- den Brok, M.G.H.E.; van Dalen, J.W.; van Gool, W.A.; Moll van Charante, E.P.; de Bie, R.M.A.; Richard, E. Apathy in Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Mov. Disord. 2015, 30, 759–769. [CrossRef]

- Davidson, J.R.T.; Ballenger, J.C.; Lecrubier, Y.; Rickels, K.; Borkovec, T.D.; Stein, D.J.; Nutt, D.J. Pharmacotherapy of Generalized Anxiety Disorder. In Proceedings of the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry; 2001; Vol. 62, pp. 46–52.

- Schmahmann, J.D. Disorders of the Cerebellum: Ataxia, Dysmetria of Thought, and the Cerebellar Cognitive Affective Syndrome. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2004, 16, 367–378. [CrossRef]

- Leggio, M.; Olivito, G. Topography of the Cerebellum in Relation to Social Brain Regions and Emotions. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Elsevier B.V., 2018; Vol. 154, pp. 71–84.

- Lee, Y.J.; Guell, X.; Hubbard, N.A.; Siless, V.; Frosch, I.R.; Goncalves, M.; Lo, N.; Nair, A.; Ghosh, S.S.; Hofmann, S.G.; et al. Functional Alterations in Cerebellar Functional Connectivity in Anxiety Disorders. Cerebellum 2021, 20, 392–401. [CrossRef]

- Stagg, C.J.; Bachtiar, V.; Amadi, U.; Gudberg, C.A.; Ilie, A.S.; Sampaio-Baptista, C.; O’Shea, J.; Woolrich, M.; Smith, S.M.; Filippini, N.; et al. Local GABA Concentration Is Related to Network-Level Resting Functional Connectivity. Elife 2014, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Ferini-Strambi, L.; Di Gioia, M.R.; Castronovo, V.; Oldani, A.; Zucconi, M.; Cappa, S.F. Neuropsychological Assessment in Idiopathic REM Sleep Behavior Disorder (RBD): Does the Idiopathic Form of RBD Really Exist? Neurology 2004, 62, 41–45. [CrossRef]

- Fantini, M.L.; Farini, E.; Ortelli, P.; Zucconi, M.; Manconi, M.; Cappa, S.; Ferini-Strambi, L. Longitudinal Study of Cognitive Function in Idiopathic REM Sleep Behavior Disorder. Sleep 2011, 34, 619–625. [CrossRef]

- Park, G.; Jo, H.; Chai, Y.; Park, H.R.; Lee, H.; Joo, E.Y.; Kim, H. Static and Dynamic Brain Morphological Changes in Isolated REM Sleep Behavior Disorder Compared to Normal Aging. Front. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1365307. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Cai, Y.-C.; Liu, D.-Y.; Yu, J.; Wang, J.; Li, M.; Xu, B.; Wang, T.; Chen, G.; Northoff, G.; et al. GABAergic Inhibition in Human HMT+ Predicts Visuo-Spatial Intelligence Mediated through the Frontal Cortex. Elife 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Niendam, T.A.; Laird, A.R.; Ray, K.L.; Dean, Y.M.; Glahn, D.C.; Carter, C.S. Meta-Analytic Evidence for a Superordinate Cognitive Control Network Subserving Diverse Executive Functions. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 2012, 12, 241–268. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Zhou, L.; Chen, Z.; Luo, N.; Niu, M.; Li, Y.; Kang, W.; Liu, J. Dynamic Functional Connectivity Impairments in Idiopathic Rapid Eye Movement Sleep Behavior Disorder. Park. Relat. Disord. 2020, 79, 11–17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firbank, M.J.; Pasquini, J.; Best, L.; Foster, V.; Sigurdsson, H.P.; Anderson, K.N.; Petrides, G.; Brooks, D.J.; Pavese, N. Cerebellum and Basal Ganglia Connectivity in Isolated REM Sleep Behaviour Disorder and Parkinson’s Disease: An Exploratory Study. Brain Imaging Behav. 2024, 18, 1428–1437. [CrossRef]

- Dyke, K.; Pépés, S.E.; Chen, C.; Kim, S.; Sigurdsson, H.P.; Draper, A.; Husain, M.; Nachev, P.; Gowland, P.A.; Morris, P.G.; et al. Comparing GABA-Dependent Physiological Measures of Inhibition with Proton Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy Measurement of GABA Using Ultra-High-Field MRI. Neuroimage 2017, 152, 360–370. [CrossRef]

- Boucherie, D.E.; Reneman, L.; Ruhé, H.G.; Schrantee, A. Neurometabolite Changes in Response to Antidepressant Medication: A Systematic Review of 1H-MRS Findings. NeuroImage Clin. 2023, 40. [CrossRef]

- Daniel, S.E.; Lees, A.J. Parkinson’s Disease Society Brain Bank, London: Overview and Research. In Proceedings of the Journal of Neural Transmission, Supplement; 1993; pp. 165–172.

- Sateia, M.J. International Classification of Sleep Disorders-Third Edition Highlights and Modifications. Chest 2014, 146, 1387–1394. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goetz, C.G.; Poewe, W.; Rascol, O.; Sampaio, C.; Stebbins, G.T.; Counsell, C.; Giladi, N.; Holloway, R.G.; Moore, C.G.; Wenning, G.K.; et al. Movement Disorder Society Task Force Report on the Hoehn and Yahr Staging Scale: Status and Recommendations. Mov. Disord. 2004, 19, 1020–1028. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association DSM 5; 2013; ISBN 9780890425541.

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. “Mini-Mental State”. A Practical Method for Grading the Cognitive State of Patients for the Clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emre, M.; Aarsland, D.; Brown, R.; Burn, D.J.; Duyckaerts, C.; Mizuno, Y.; Broe, G.A.; Cummings, J.; Dickson, D.W.; Gauthier, S.; et al. Clinical Diagnostic Criteria for Dementia Associated with Parkinson’s Disease. Mov. Disord. 2007, 22, 1689–1707. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, K.R.; Healy, D.G.; Schapira, A.H. Non-Motor Symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease: Diagnosis and Management. Lancet Neurol. 2006, 5, 235–245. [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T., Steer, R.A., & Brown, G.K. Beck Depression Inventory-Second Edition (BDI-II) | Men’s Health Initiative.

- Weintraub, D.; Hoops, S.; Shea, J.A.; Lyons, K.E.; Pahwa, R.; Driver-Dunckley, E.D.; Adler, C.H.; Potenza, M.N.; Miyasaki, J.; Siderowf, A.D.; et al. Validation of the Questionnaire for Impulsive-Compulsive Disorders in Parkinson’s Disease. Mov. Disord. 2009, 24, 1461–1467. [CrossRef]

- First, M.B.; Williams, J.B.W.; Karg, R.S.; Spitzer, R.L. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 ® -Research Version; American Psychiatric Association, 2015.

- First, M.B. SCID-5-PD : Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Personality Disorders : Includes the Self-Report Screener Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Screening Personality Questionnaire (SCID-5-SPQ); American Psychiatric Association, 2016; ISBN 9781585624744.

- Reitan, R.M. Trail Making Test, Manual for Administration and Scoring; Tucson, AZ: Reitan Neuropsychology Laboratory., 1992.

- Tkáč, I.; Starčuk, Z.; Choi, I.Y.; Gruetter, R. In Vivo 1H NMR Spectroscopy of Rat Brain at 1 Ms Echo Time. Magn. Reson. Med. 1999, 41, 649–656. [CrossRef]

- Gruetter, R.; Tkáč, I. Field Mapping without Reference Scan Using Asymmetric Echo-Planar Techniques. Magn. Reson. Med. 2000, 43, 319–323. [CrossRef]

- Tkáč, I.; Gruetter, R. Methodology of 1H NMR Spectroscopy of the Human Brain at Very High Magnetic Fields. Appl. Magn. Reson. 2005, 29, 139–157. [CrossRef]

- Edden, R.A.E.; Puts, N.A.J.; Harris, A.D.; Barker, P.B.; Evans, C.J. Gannet: A Batch-Processing Tool for the Quantitative Analysis of Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid–Edited MR Spectroscopy Spectra. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2014, 40, 1445–1452. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Near, J.; Edden, R.; Evans, C.J.; Paquin, R.; Harris, A.; Jezzard, P. Frequency and Phase Drift Correction of Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy Data by Spectral Registration in the Time Domain. Magn. Reson. Med. 2015, 73, 44–50. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| HC (N=18) | iRBD (N=18) | dnPD (N=20) | t, chi2, F | df | p | |

| Age, mean (sd) | 67 (9.5) | 68.6 (8.3) | 67.1 (10) | 0.154 | 2;53 | 0.858 |

| Sex, male (%) | 11 (61) | 13 (72) | 13 (65) | 0.512 | 2 | 0.774 |

| Years of education, mean (sd) | 13.2 (3.8) | 13.3 (4.3) | 12.8 (4.7) | 0.065 | 2;53 | 0.937 |

| Age of onset, mean (sd) | - | 65.3 (8.5) | 65.7 (9.9) | -0.14 | 36 | 0.889 |

| Age of diagnosis, mean (sd) | - | 67.3 (8.5) | 66.5 (10) | 0.258 | 36 | 0.798 |

| RBD illness duration, (years) mean (sd) | 3.28 (2.1) | - | - | - | ||

| dnPD illness duration, (years) mean (sd) | - | - | 1.45 (1) | - | - | - |

| Antidepressant, yes (%) | 1 (5) | 1 (5.6) | 3 (15) | 1.41 | 2 | 0.494 |

| Benzodiazepines, yes (%) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 3 (15) | 3.32 | 2 | 0.191 |

| MDS-UPDRS I, mean (sd) | - | 5.78 (2.8) | 6.6 (3.6) | - 0.779 | 36 | 0.441 |

| MDS-UPDRS II, mean (sd) | - | 0.89 (1.4) | 5.20 (3.2) | -5.261 | 36 | <0.0001* |

| MDS-UPDRS III, mean (sd) | - | 2.55 (2.3) | 25.9 (9.4) | -10.287 | 36 | <0.0001* |

| H&Y, median | - | - | 2 | - | - | - |

| Symptoms laterality, right (%) | - | - | 11 (55) | - | - | - |

| ICDs, no (%) | - | 18 (100) | 19 (95) | 0.924 | 1 | 0.336 |

| NMSS, mean (sd) | - | 28.3 (20.4) | 33.8 (23.1) | -.778 | 36 | 0.442 |

| HC (N=18) | iRBD (N=18) | dnPD (N=20) | F, H | df | p | |

| Metabolites concentrations | ||||||

| GABA_L | 3.71 (0.48) | 3.79 (0.46) | 3.53 (0.46) | 1.59 | 2;52 | 0.214 |

| GABA_R | 3.95 (0.57) | 4.07 (0.74) | 3.95 (0.53) | 0.225 | 2;50 | 0.799 |

| GABAavg | 3.87 (0.35) | 3.96 (0.43) | 3.76 (0.40) | 1.166 | 2;49 | 0.322 |

| Glx_L # | 6.83 (0.75) | 7.27 (1.12) | 6.55 (1.27) | 3.446 | 2 | 0.179 |

| Glx_R | 6.92 (1.23) | 7.15 (1.16) | 7.47 (1.36) | 0.886 | 2;52 | 0.418 |

| Glxavg | 6.95 (0.86) | 7.19 (0.95) | 7.01 (1.13) | 0.248 | 2;50 | 0.781 |

| Glx/GABA_L | 1.88 (0.28) | 1.93 (0.29) | 1.88 (0.36) | 0.174 | 2;51 | 0.841 |

| Glx/GABA_R # | 1.76 (0.24) | 1.77 (0.33) | 1.95 (0.24) | 7.216 | 2 | 0.027* |

| Glx/GABAavg | 1.81 (0.22) | 1.82 (0.17) | 1.89 (0.19) | 0.943 | 2;48 | 0.396 |

| Neuropsychiatric scores | ||||||

| HARS # | 2.78 (3.26) | 7.83 (4.46) | 8.15 (6.37) | 15.688 | 2 | <.001* |

| BDI-Som # | 1.61 (1.33) | 3.67 (2.2) | 3.35 (2.13) | 10.521 | 2 | 0.005* |

| BDI-Tot # | 3.44 (3.1) | 7.78 (5.9) | 7.20 (6.1) | 8.192 | 2 | 0.017* |

| Apathy Scale # | 0.94 (1.21) | 3.06 (4.80) | 3.10 (2.81) | 7.136 | 2 | 0.028* |

| TAS-F1 | 7.9 (1.02) | 9.44 (3.76) | 9.0 (2.86) | 1.276 | 2 | 0.528 |

| TAS-F2 | 8.67 (3.77) | 8.72 (4.4) | 9.15 (2.9) | 0.777 | 2 | 0.678 |

| TAS-F3 | 15.44 (4.74) | 15.78 (4.73) | 16.75 (3.53) | 2.436 | 2 | 0.296 |

| TAS Tot. | 32.11 (7.35) | 34.56 (9.3) | 34.70 (4.3) | 1.965 | 2 | 0.374 |

| Neuropsychological performance | ||||||

| Rey’s 15w Immediate Recall | 48.22 (7.67) | 36.61 (8.08) | 38.85 (9.77) | 9.304 | 2;53 | <.001* |

| Rey’s 15w Delayed Recall # | 10.89 (2.63) | 8 (3.05) | 8.45 (2.93) | 9.084 | 2 | 0.011* |

| WCST-msf Pers. Err. # | 0.44 (0.86) | 1.78 (1.93) | 1.65 (2.28) | 7.473 | 2 | 0.024* |

| Post Hoc Comparisons | |||||||||

| HC vs iRBD | HC vs dnPD | iRBD vs dnPD | |||||||

| Mean Diff. | U | p | Mean Diff. | U | p | Mean Diff. | U, t | p | |

| Metabolites concentrations | |||||||||

| Glx/GABA_R # | -0.01 | 135 | 0.744 | -0.19 | 86 | 0.017* | -0.18 | 93 | 0.03* |

| Neuropsychiatric group differences | |||||||||

| HARS # | -5.05 | 52 | <.001* | -5.05 | 66 | <.001* | -0.320 | 165 | 0.67 |

| BDI-Som # | -2.06 | 72 | 0.004* | -2.06 | 89.5 | 0.007* | 0.320 | 160.5 | 0.564 |

| BDI-Tot # | -4.34 | 79 | 0.008* | -4.34 | 101 | 0.021* | 0.580 | 170 | 0.769 |

| Apathy Scale # | -2.12 | 127 | 0.279 | -2.12 | 85.5 | 0.004* | -0.040 | 145 | 0.317 |

| Neuropsychological groups differences | |||||||||

| Rey’s 15w Immediate Recall | 11.61 | 11.6 | <.001* | 11.61 | 9.37 | 0.004* | -2.240 | -2.24 | 1 (Bonf.p) |

| Rey’s 15w Delayed Recall # | 2.89 | 76.5 | 0.007* | 2.89 | 97.5 | 0.015* | -0.450 | 159 | 0.553 |

| WCST-msf Pers. Err. # | -1.34 | 89 | 0.012* | -1.34 | 108 | 0.021* | 0.130 | 168 | 0.716 |

| Correlation Analyses | ||||

| Glx/GABA_R ~ Neuropsychiatric Measures | ||||

| Spearman’s coefficient | R2 | p | ||

| iRBD | HARS # | -0.50 | 0.25 | 0.043 |

| BDI-Som # | -0.63 | 0.40 | 0.007 | |

| BDI-Tot # | -0.60 | 0.36 | 0.010 | |

| TAS-F1 | -0.52 | 0.27 | 0.032 | |

| dnPD | No significant correlations | |||

| HC | No significant correlations | |||

| Glx/GABA_R ~ Neuropsychological Measures | ||||

| iRBD | Copy of R-O picture | 0.54 | 0.29 | 0.024 |

| WCST-msf Pers. Err | -0.58 | 0.34 | 0.015 | |

| dnPD | No significant correlations | |||

| HC | Rey’s 15w Delayed Recall | 0.51 | 0.26 | 0.038 |

| Copy of R-O picture | 0.58 | 0.34 | 0.015 | |

| SWCT-Color, time | -0.593 | 0.35 | 0.012 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).