Submitted:

15 October 2025

Posted:

16 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Material and Methods

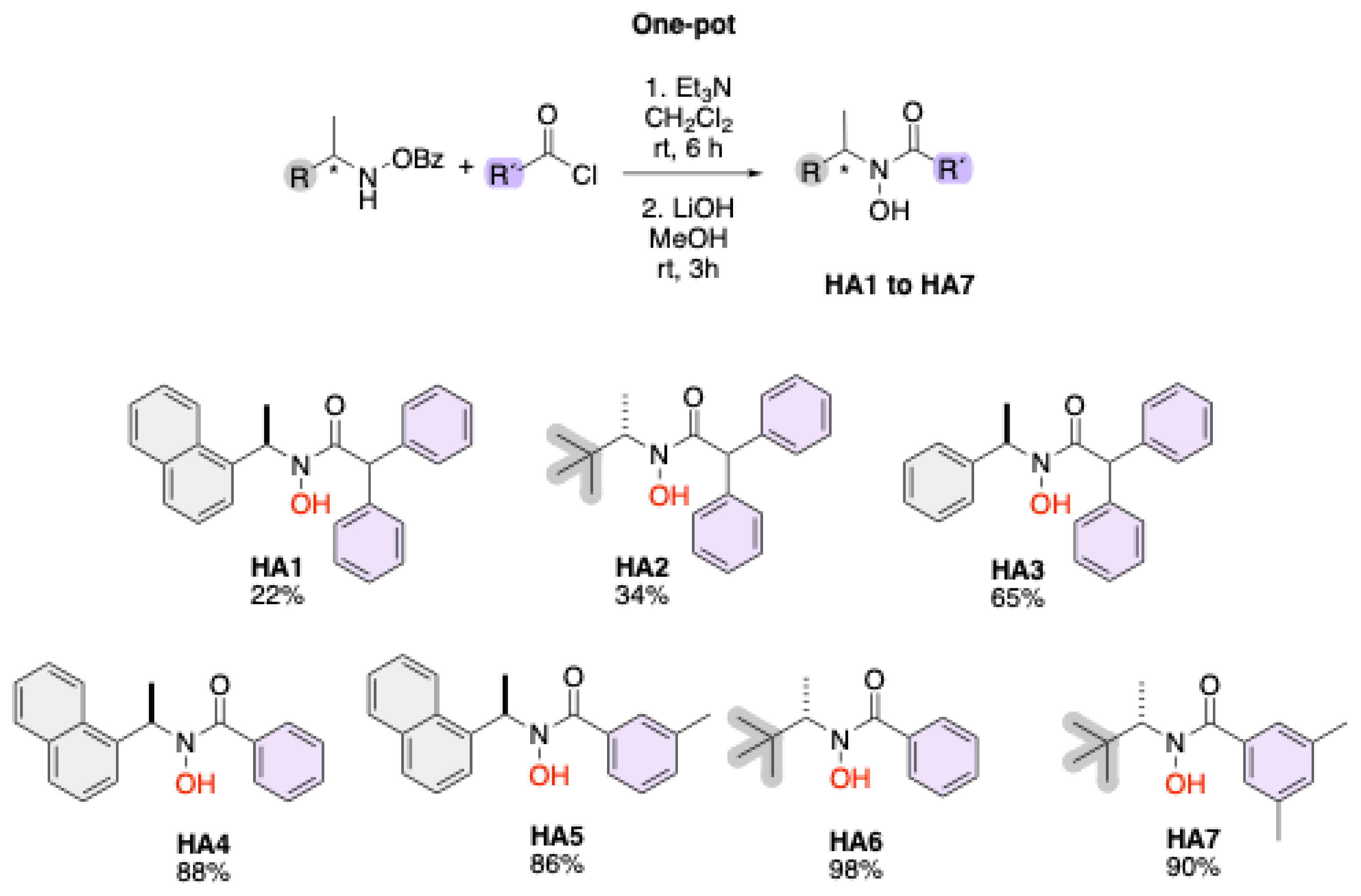

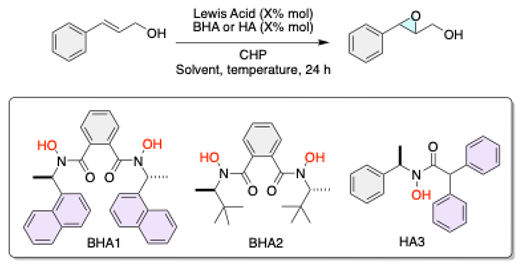

- Synthesis of Chiral BHA´s and HAs; General Procedure,

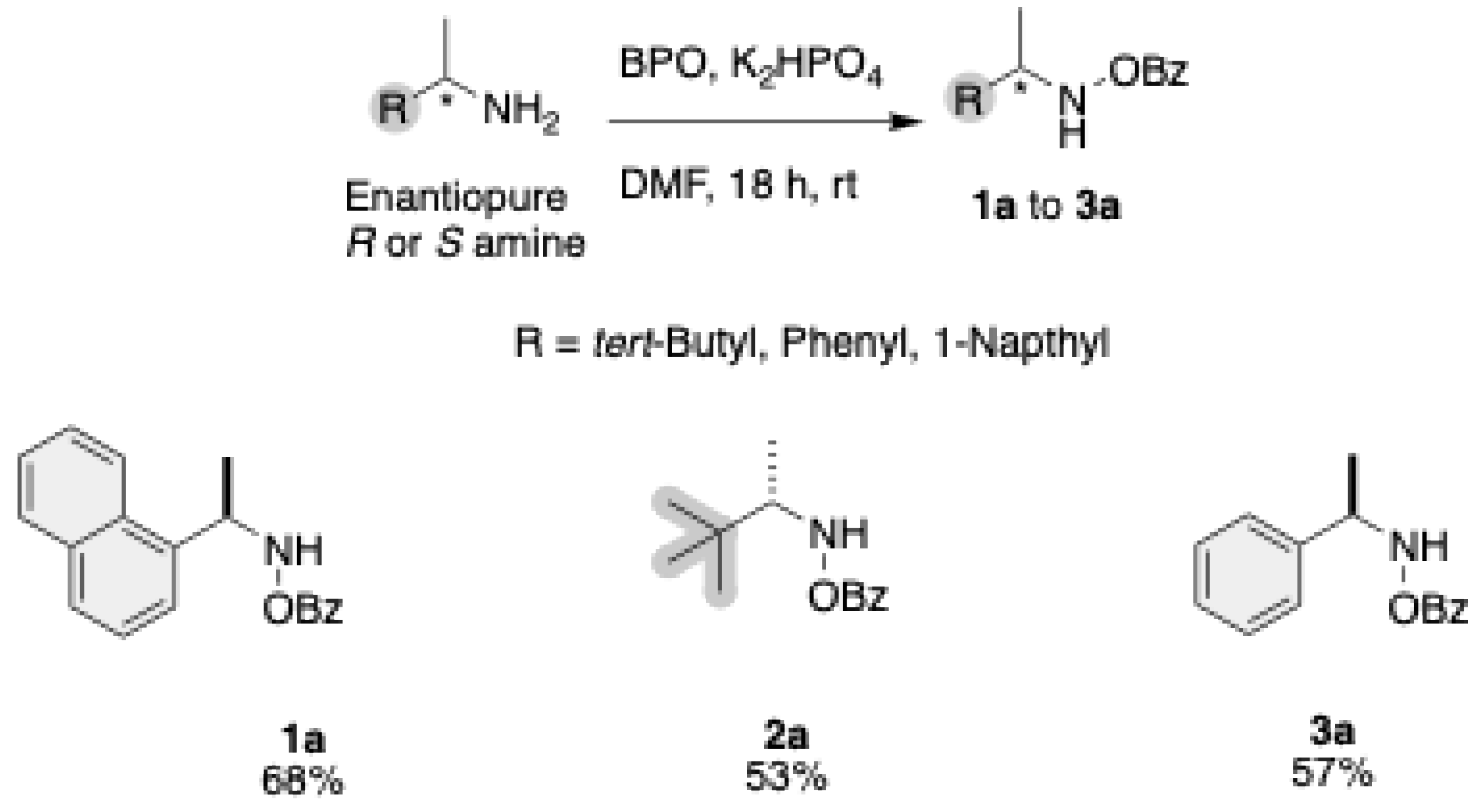

- Synthesis of Synthesis of N-OBz amines (1a to 3a); General Procedure A

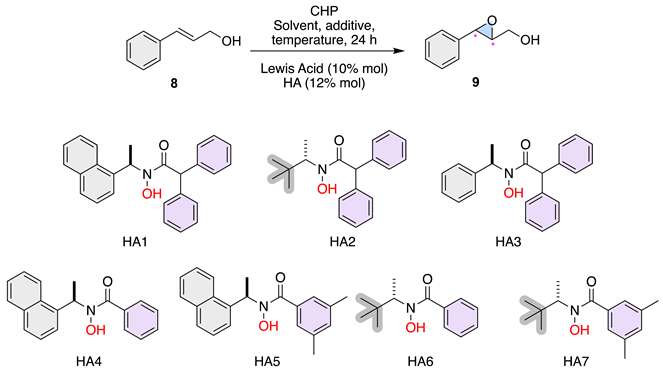

- Asymmetric Epoxidation of Allylic Alcohol; General Procedure D

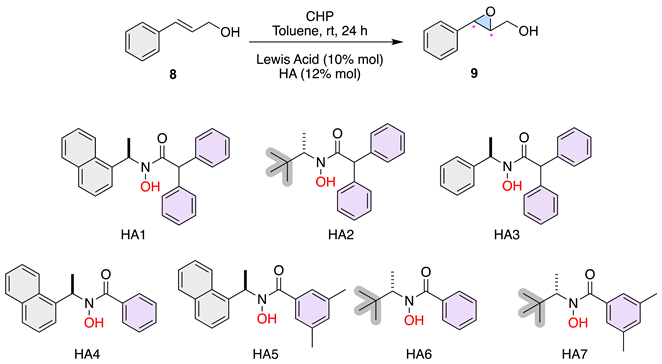

- Synthesis of ((2R,3R)-3-Phenyloxiran-2-yl)methanol (9)

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis of N-Obz Amines

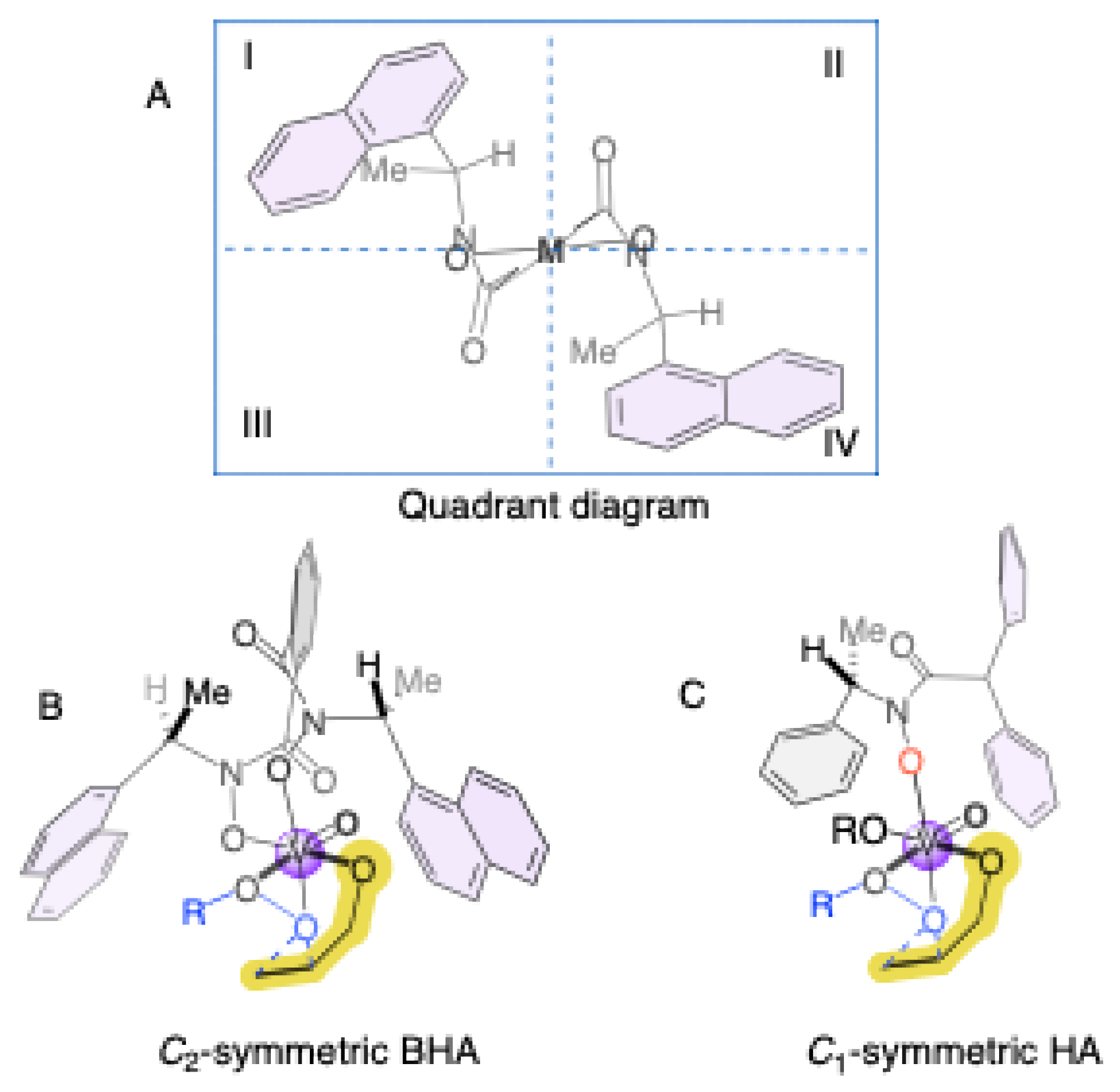

3.2. Analysis of Epoxidation Reaction Conditions

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Lewis Acid (% mol) |

HA (% mol) |

Solvent | Additive | Temperature | Conversion (%) | e.e.b (%) |

| 1 | VO(OiPr)3 (10) | HA2 (12) |

CH2Cl2 | - | r.t. | ≥99 | 23 |

| 2 | VO(OiPr)3 (10) | HA2 (12) |

CH3CN | - | r.t. | ≥99 | 4 |

| 3 | VO(OiPr)3 (10) | HA3 (12) |

CH2Cl2 | - | r.t. | ≥99 | 71 |

| 4 | VO(OiPr)3 (10) | HA3 (12) |

CH3CN | - | r.t. | ≥99 | 63 |

| 5 | VO(OiPr)3 (5) |

HA2 (7) |

Toluene | - | r.t. | ≥99 | 8 |

| 6 | VO(OiPr)3 (5) |

HA2 (7) |

Toluene | - | r.t. | ≥99 | 55 |

| 7 | Ti(OiPr)4 (1.05 eq) |

HA3 (1.05 eq) |

CH2Cl2 | - | r.t. | 0 | n.d. |

| 8 | VO(OiPr)3 (10) | HA2 (12) |

Toluene | MS 4Å | r.t. | ≥99 | 18 |

| 9 | VO(OiPr)3 (10) | HA2 (12) |

Toluene | MgO | r.t. | ≥99 | 22 |

| 10 | VO(OiPr)3 (10) | HA2 (20) |

Toluene | - | r.t. | ≥99 | 25 |

| 11a | VO(OiPr)3 (10) | HA7 (20) |

Toluene | - | r.t. | ≥99 | 7 |

| 12 | VO(OiPr)3 (10) | HA1 (12) |

Toluene | - | 0 °C | ≥99 | 19 |

| 13 | VO(OiPr)3 (10) | HA3 (12) |

Toluene | - | 0 °C | ≥99 | 23 |

| 14 | VO(OiPr)3 (10) | HA2 (12) |

Toluene | - | 0 °C | ≥99 | 21 |

| 15 | VO(OiPr)3 (10) | HA6 (12) |

Toluene | - | 0 °C | ≥99 | 8 |

| 16 | VO(OiPr)3 (10) | HA7 (12) |

Toluene | - | 0 °C | ≥99 | 4 |

| 17 | VO(OiPr)3 (10) | HA4 (12) |

Toluene | - | 0 °C | ≥99 | 14 |

| 18 | VO(OiPr)3 (10) | HA5 (12) |

Toluene | - | 0 °C | ≥99 | 24 |

| 19 | VO(acac)2 (10) | HA2 (12) |

Toluene | - | 0 °C | ≥99 | 17 |

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgements

References

- Li, Z.; Yamamoto, H. Hydroxamic Acids in Asymmetric Synthesis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46 (2), 506–518. [CrossRef]

- Pawar, T. J.; Bonilla-Landa, I.; Reyes-Luna, A.; Barrera-Méndez, F.; Enríquez-Medrano, F. J.; Díaz-de-León-Gómez, R. E.; Olivares-Romero, J. L. Chiral Hydroxamic Acid Ligands in Asymmetric Synthesis: The Evolution of Metal-Catalyzed Oxidation Reactions. ChemistrySelect 2023, 8, e202300555. [CrossRef]

- Olivares-Romero, J. L.; Li, Z.; Yamamoto, H. Hf(IV)-Catalyzed Enantioselective Epoxidation of N-Alkenylsulfonamides and N-Tosyl Imines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134 (12), 5440–5443. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yamamoto, H. Zirconium(IV)- and Hafnium(IV)-Catalyzed Highly Enantioselective Epoxidation of Homoallylic and Bishomoallylic Alcohols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132 (23), 7878–7880. [CrossRef]

- Olivares-Romero, J. L.; Li, Z.; Yamamoto, H. Catalytic Enantioselective Epoxidation of Tertiary Allylic and Homoallylic Alcohols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135 (9), 3411–3413. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yamamoto, H. Tungsten-Catalyzed Asymmetric Epoxidation of Allylic and Homoallylic Alcohols with Hydrogen Peroxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136 (4), 1222–1225. [CrossRef]

- Pawar, T. J.; Valtierra-Galván, M. F.; Rodríguez-Hernández, A.; Reyes-Luna, A.; Bonilla-Landa, I.; García-Barradas, O.; Barrera-Méndez, F.; Olivares-Romero, J. L. Synthesis of Novel C₂-Bishydroxamic Acid Ligands and Their Application in Asymmetric Epoxidation Reactions. Synlett 2023, 34, 2496–2502. [CrossRef]

- Medford, A.; Vojvodic, A.; Hummelshøj, J.; Voss, J.; Abild-Pedersen, F.; Studt, F.; Bligaard, T.; Nilsson, A.; Nørskov, J. K. From the Sabatier Principle to a Predictive Theory of Transition-Metal Heterogeneous Catalysis. J. Catal. 2015, 328, 36–42. [CrossRef]

- Suto, Y.; Tsuji, R.; Kanai, M.; Shibasaki, M. Cu(I)-Catalyzed Direct Enantioselective Cross-Aldol-Type Reaction of Acetonitrile. Org. Lett. 2005, 7 (17), 3757–3760. [CrossRef]

- Pfaltz, A.; Drury, W. J. Design of Chiral Ligands for Asymmetric Catalysis: From C₂-Symmetric P,P- and N,N-Ligands to Sterically and Electronically Nonsymmetrical P,N-Ligands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004, 101 (16), 5723–5726. [CrossRef]

- Cussó, O.; Cianfanelli, M.; Ribas, X.; Gebbink, R. J. M. K.; Costas, M. Iron-Catalyzed Highly Enantioselective Epoxidation of Cyclic Aliphatic Enones with Aqueous H₂O₂. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138 (8), 2732–2738. [CrossRef]

- Trost, B. M.; Donckèle, E. J.; Thaisrivongs, D. A.; Osipov, M.; Masters, J. T. A New Class of Non-C₂-Symmetric Ligands for Oxidative and Redox-Neutral Palladium-Catalyzed Asymmetric Allylic Alkylations of 1,3-Diketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137 (7), 2776–2784. [CrossRef]

- Trost, B. M.; Hung, C.-I.; Koester, D. C.; Miller, Y. Development of Non-C₂-Symmetric Prophenol Ligands: The Asymmetric Vinylation of N-Boc Imines. Org. Lett. 2015, 17 (15), 3778–3781. [CrossRef]

- Pfaltz, A. Recent Developments in Asymmetric Catalysis. Chimia 2001, 55 (9), 708–714. [CrossRef]

- RajanBabu, T. V.; Casalnuovo, A. L. Role of Electronic Asymmetry in the Design of New Ligands: The Asymmetric Hydrocyanation Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 6325–6326. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Yamamoto, H. Direct N–O Bond Formation via Oxidation of Amines with Benzoyl Peroxide. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 2124–2129.

- Zhang, W.; Basak, A.; Kosugi, Y.; Hoshino, Y.; Yamamoto, H. Enantioselective Epoxidation of Allylic Alcohols by a Chiral Complex of Vanadium: An Effective Controller System and a Rational Mechanistic Model. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44 (28), 4389–4391. [CrossRef]

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Lewis Acid (% mol) |

HA (% mol) |

Solvent | Temperature (°C) |

Conversion (%) | e.e.a (%) | |

| 1 | VO(OiPr)3 (10) | BHA1 (10) |

CH2Cl2 | -20 | 14 | 9 | |

| 2 | VO(OiPr)3 (10) | BHA2 (10) |

CH2Cl2 | -20 | 11 | 7 | |

| 3 | VO(OiPr)3 (10) | HA3 (12) |

Toluene | r.t. | ≥99 | 19 | |

| 4 | VO(OiPr)3 (10) | HA7 (12) |

Toluene | r.t. | ≥99 | 49 | |

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Lewis Acid (10% mol) |

HA (12% mol) |

Conversion | e.e.a | |||

| 1 | Ti(OiPr)4 | HA3 | 0 | n.d. | |||

| 2 | VO(OiPr)3 | HA3 | ≥99 | 19 | |||

| 3 | Ti(OiPr)4 | HA2 | 0 | n.d. | |||

| 4 | VO(OiPr)3 | HA2 | ≥99 | 22 | |||

| 5 | VO(OiPr)3 | HA1 | ≥99 | 15 | |||

| 6 | VO(OiPr)3 | HA6 | ≥99 | 4 | |||

| 7 | VO(OiPr)3 | HA7 | ≥99 | 49 | |||

| 8 | VO(OiPr)3 | HA4 | ≥99 | 11 | |||

| 9 | VO(OiPr)3 | HA5 | ≥99 | 30 | |||

| 10 | VO(acac)2 | HA2 | ≥99 | 19 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).