Submitted:

15 October 2025

Posted:

17 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

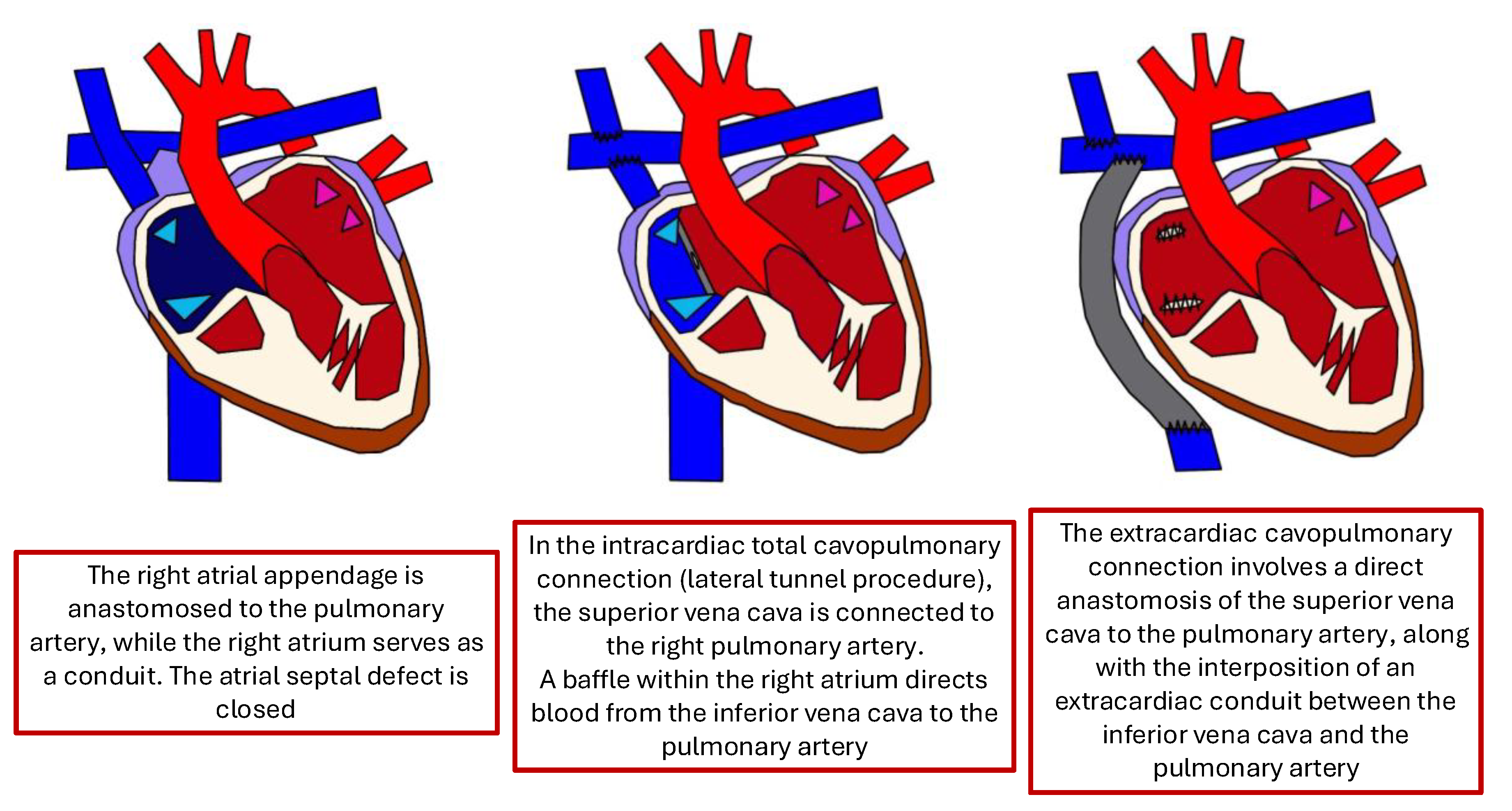

1. Introduction

- The suction effect generated by left atrial relaxation during diastole.

- The action of the respiratory and muscular pumps, driven by the negative intrathoracic pressure during inspiration, which enhances inferior vena cava return and promotes pulmonary vessel recruitment.

- The maintenance of low pulmonary vascular resistance, provided there is no mechanical obstruction within the Fontan conduit, the main pulmonary arteries, or the pulmonary veins.

- Systolic Failure Phenotype (SFP): the single ventricle’s pumping ability deteriorates, leading to a reduced ejection fraction. Clinically, patients may experience fatigue, ascites and exercise intolerance. Hemodynamically, this group is characterized by a low cardiac index, often less than 2,2 L/min/m2, and variable Fontan pressures. These patients are typically the most ill and often require early evaluation for transplant due to poor outcomes with medical therapy alone.

- Preserved Systolic Function with Elevated Pressure (PFP): In this phenotype, the ventricle itself is functioning normally in terms of contractility, but the Fontan circuit develops resistance. Elevated pressures within the Fontan pathway—often due to increased pulmonary vascular resistance, conduit stenosis, or lack of compliance—lead to systemic venous congestion. Patients may present with peripheral edema, liver congestion, and ascites. Despite a preserved cardiac output, end-organ dysfunction progresses, and clinical management often focuses on relieving congestion or improving Fontan flow dynamics.

- Lymphatic Failure Phenotype (LFP): Some patients with Fontan circulation develop complications related to abnormal lymphatic flow, even in the absence of severe hemodynamic derangements. These patients may present with protein-losing enteropathy, plastic bronchitis, or chylous effusions. This phenotype is increasingly recognized because of chronic central venous hypertension impairing lymphatic drainage, especially from the gut and lungs. Management often requires targeted lymphatic interventions, such as lymphangiography-guided embolization or specialized dietary and pharmacologic therapies.

- Normal Hemodynamics Phenotype (NHP): A subset of patients may exhibit clinical symptoms of Fontan failure despite having normal cardiac function and pressures. These cases can be particularly challenging to diagnose and manage, as standard hemodynamic evaluations appear normal. The underlying mechanisms are not fully understood but may involve diastolic dysfunction, subtle microvascular issues, or autonomic imbalance. Despite “normal” measurements, these patients may have reduced exercise tolerance or quality of life and require a multidisciplinary approach to evaluation.

2. Fald Epidemiology

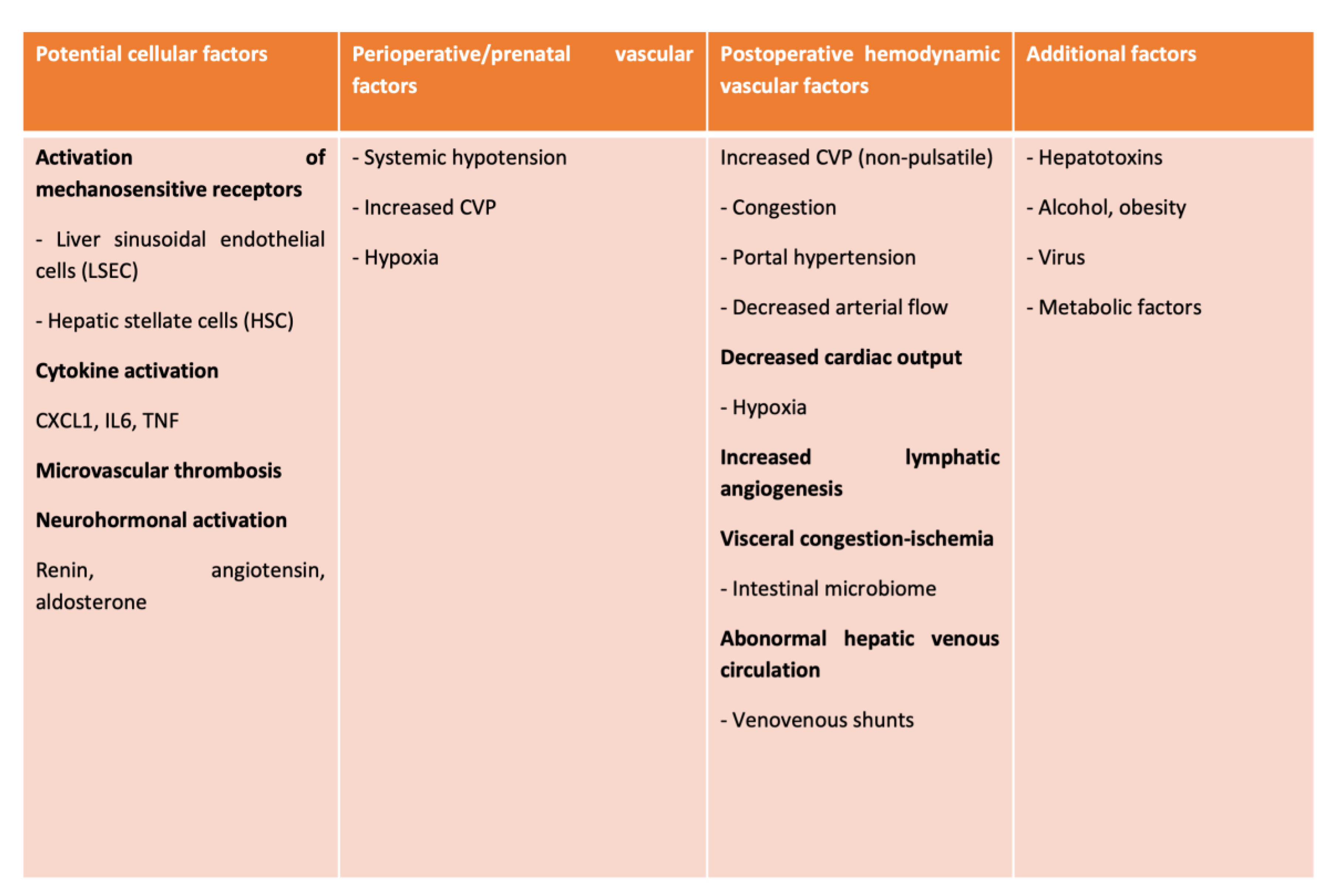

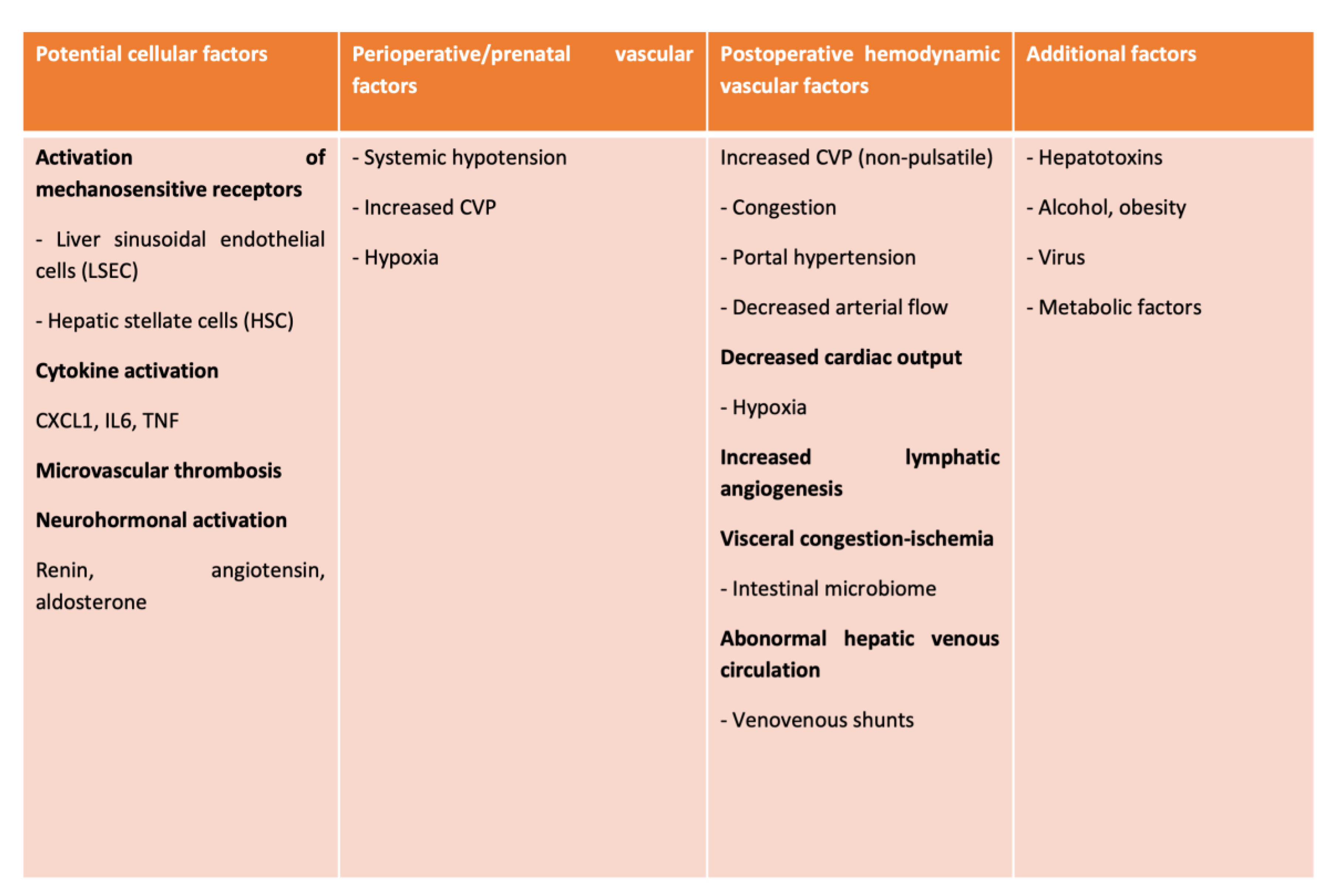

3. Pathophysiology

4. Clinical Presentation

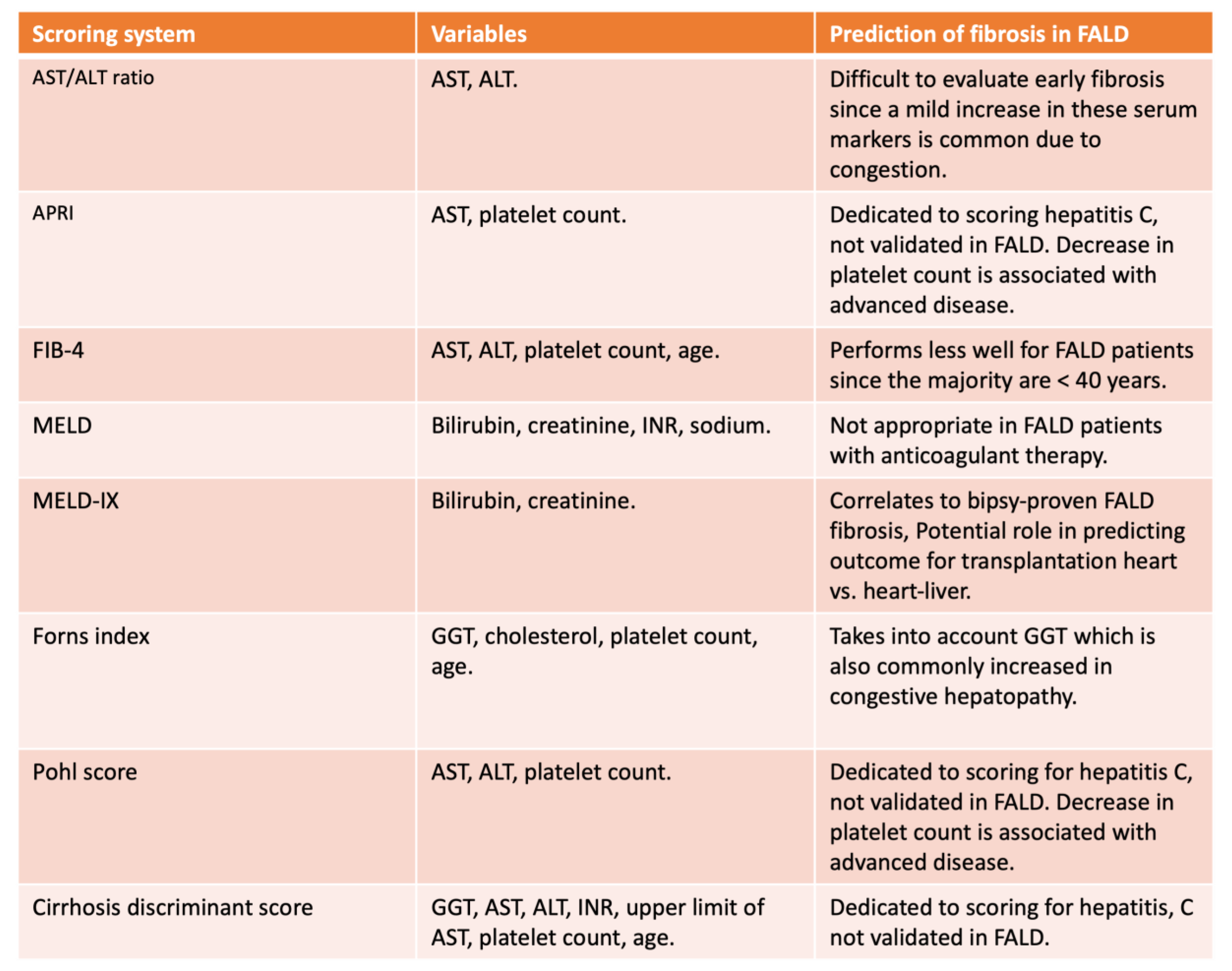

5. Diagnosis

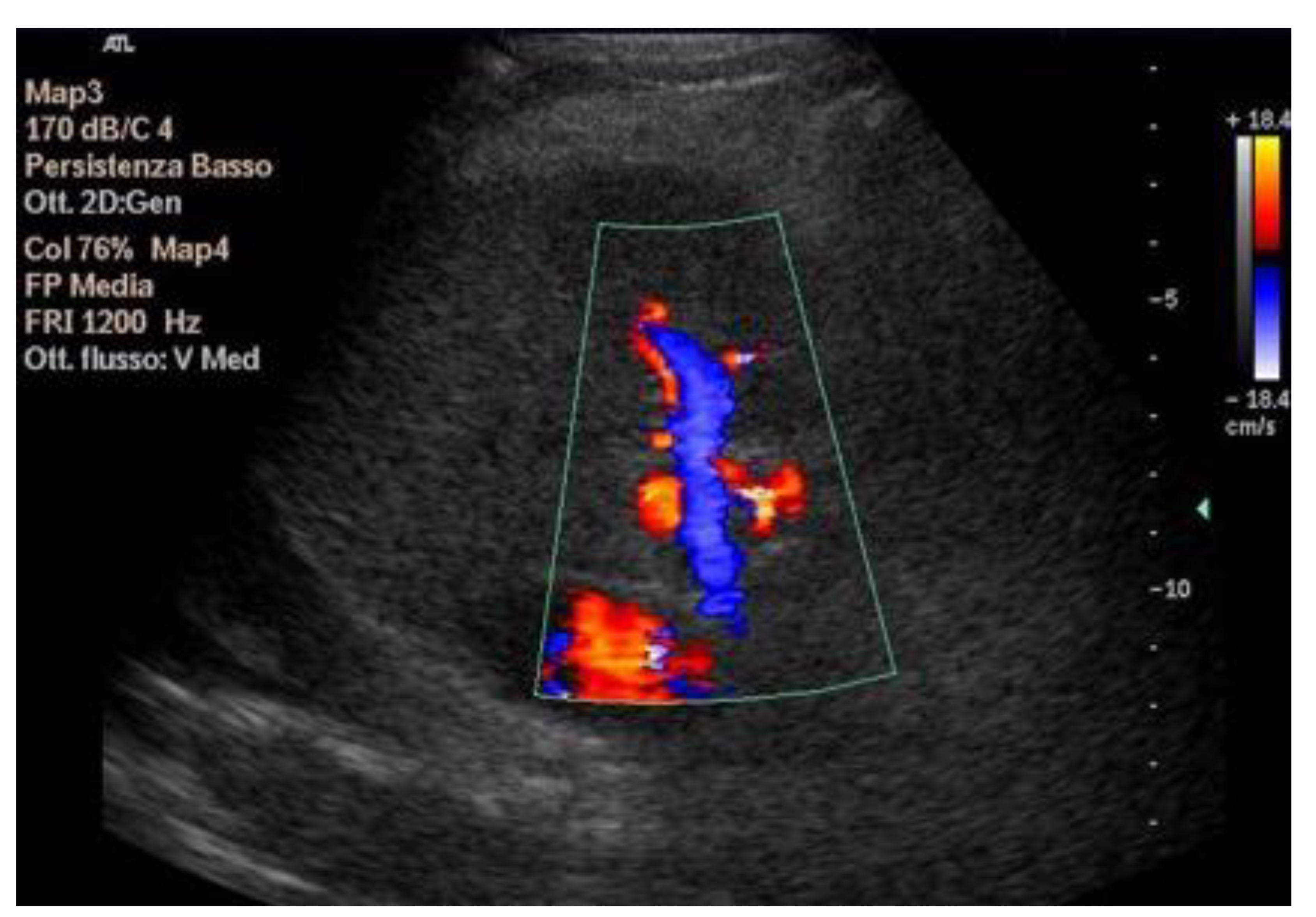

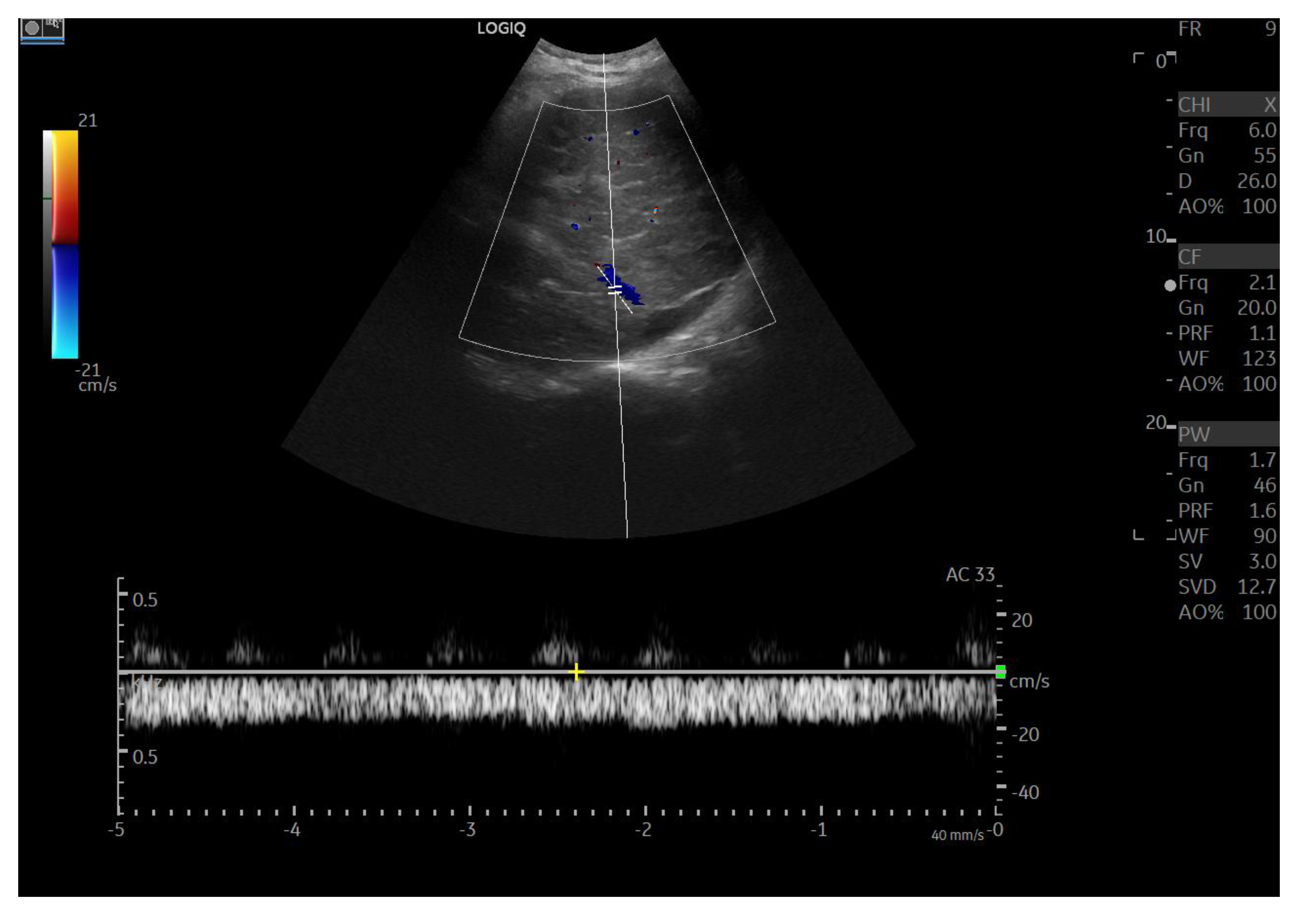

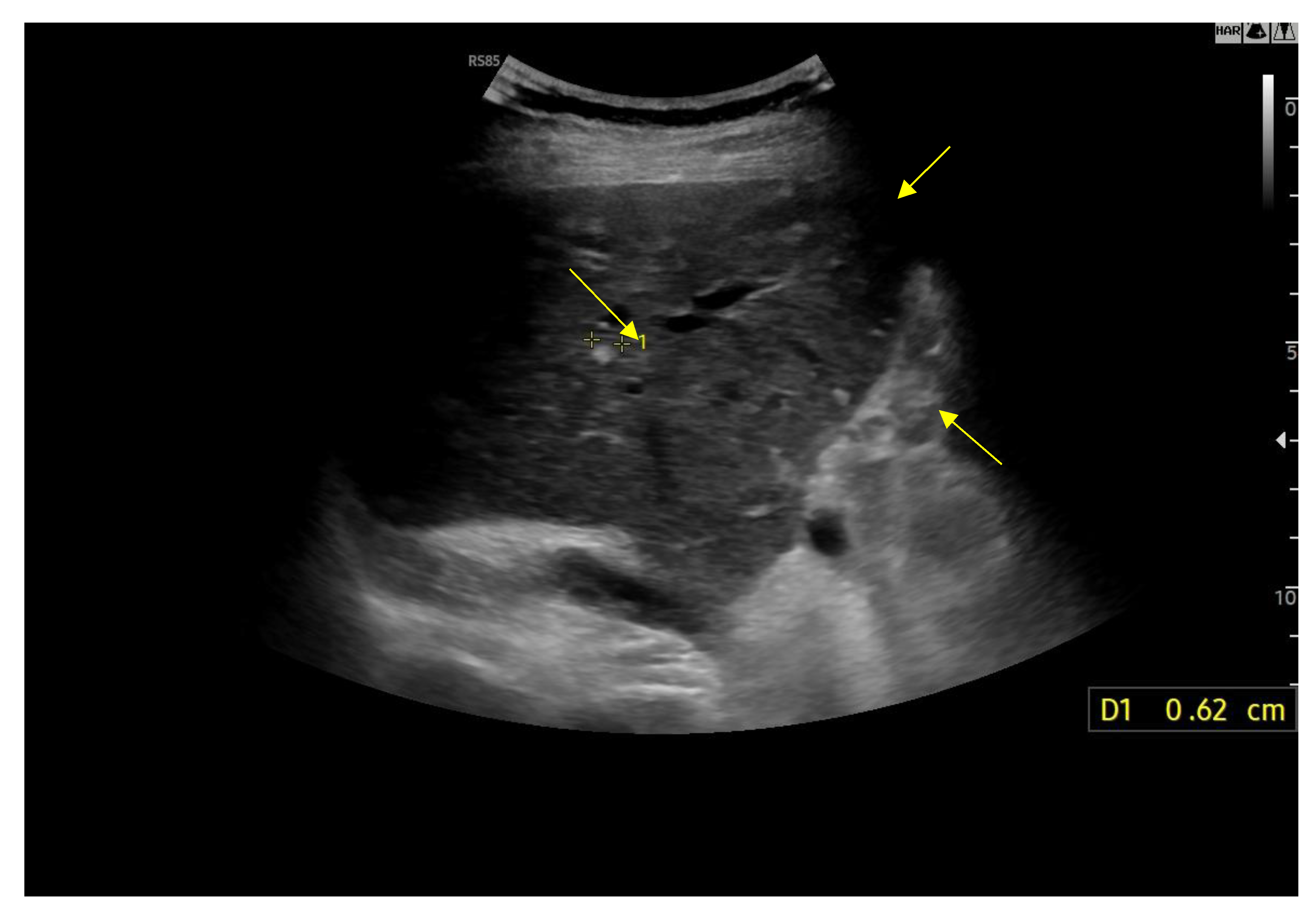

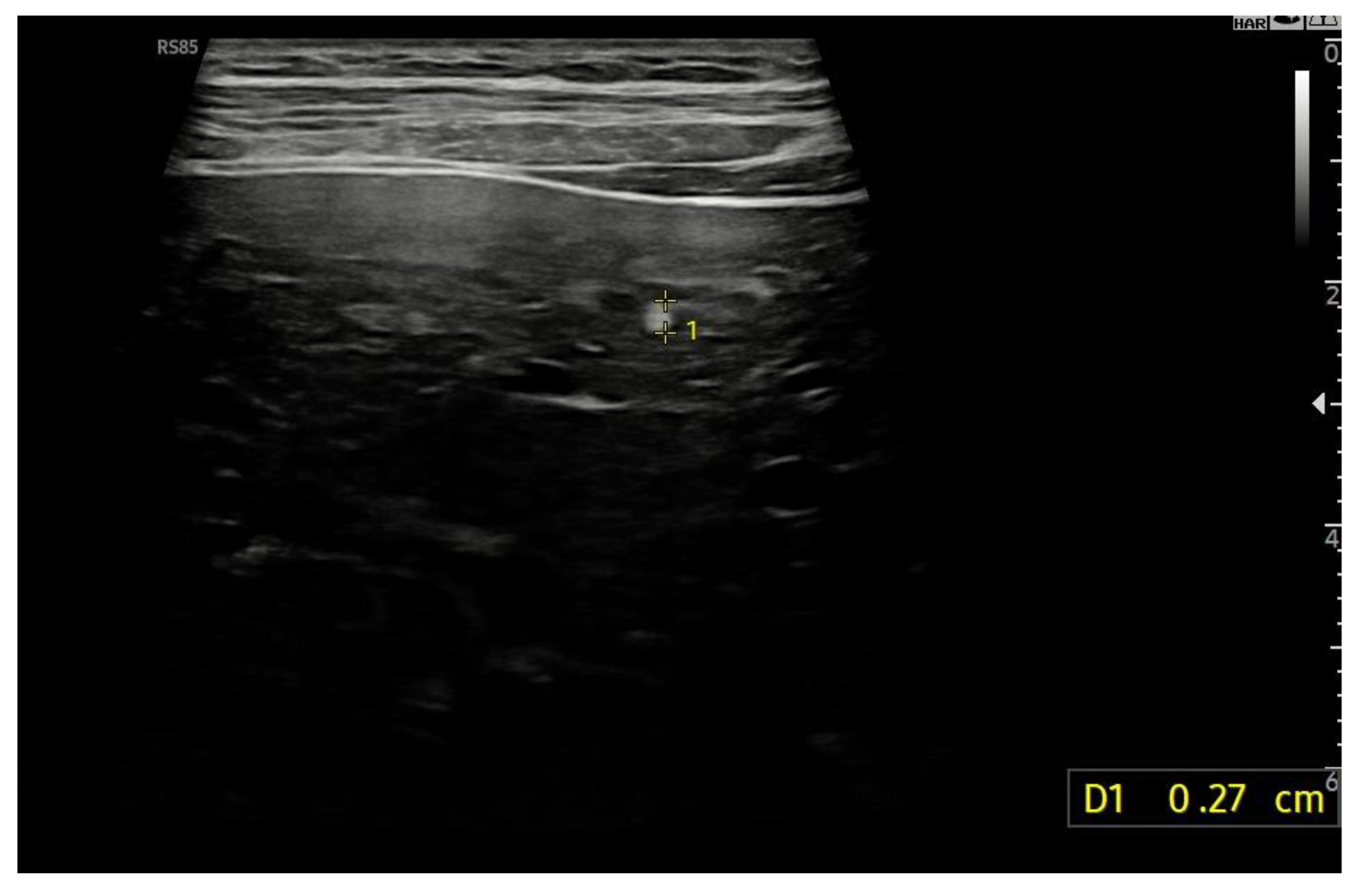

7. Imaging

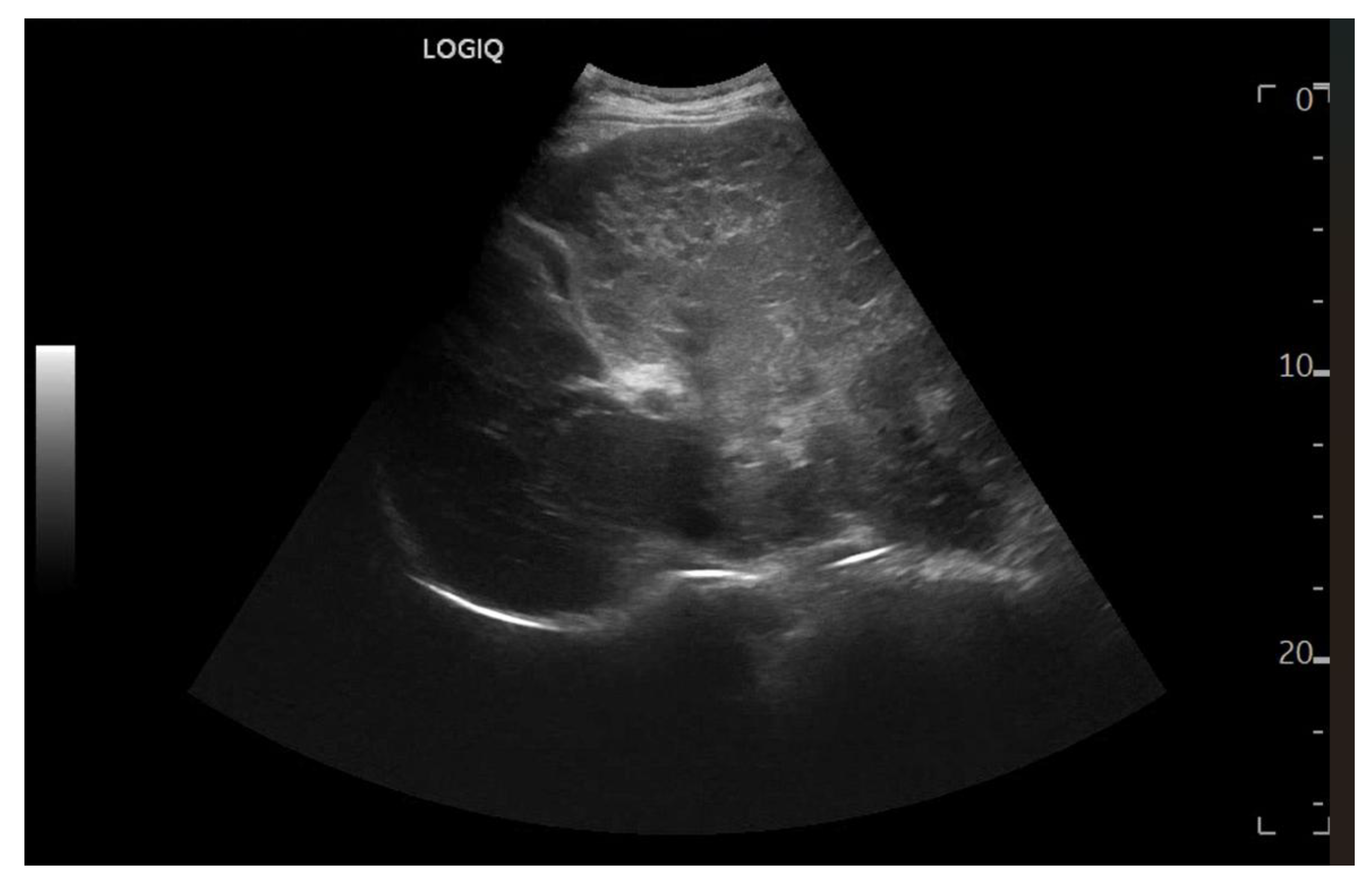

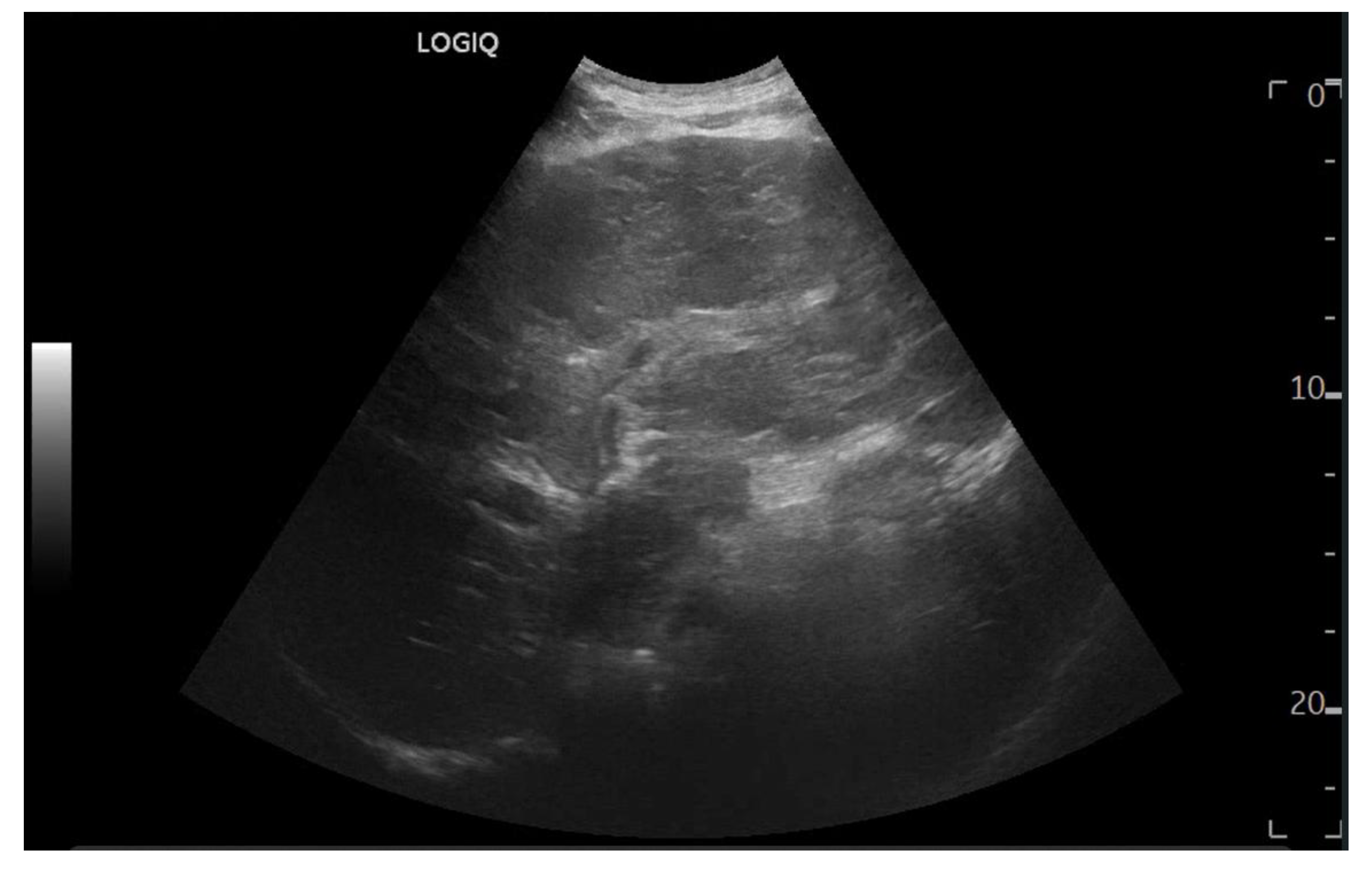

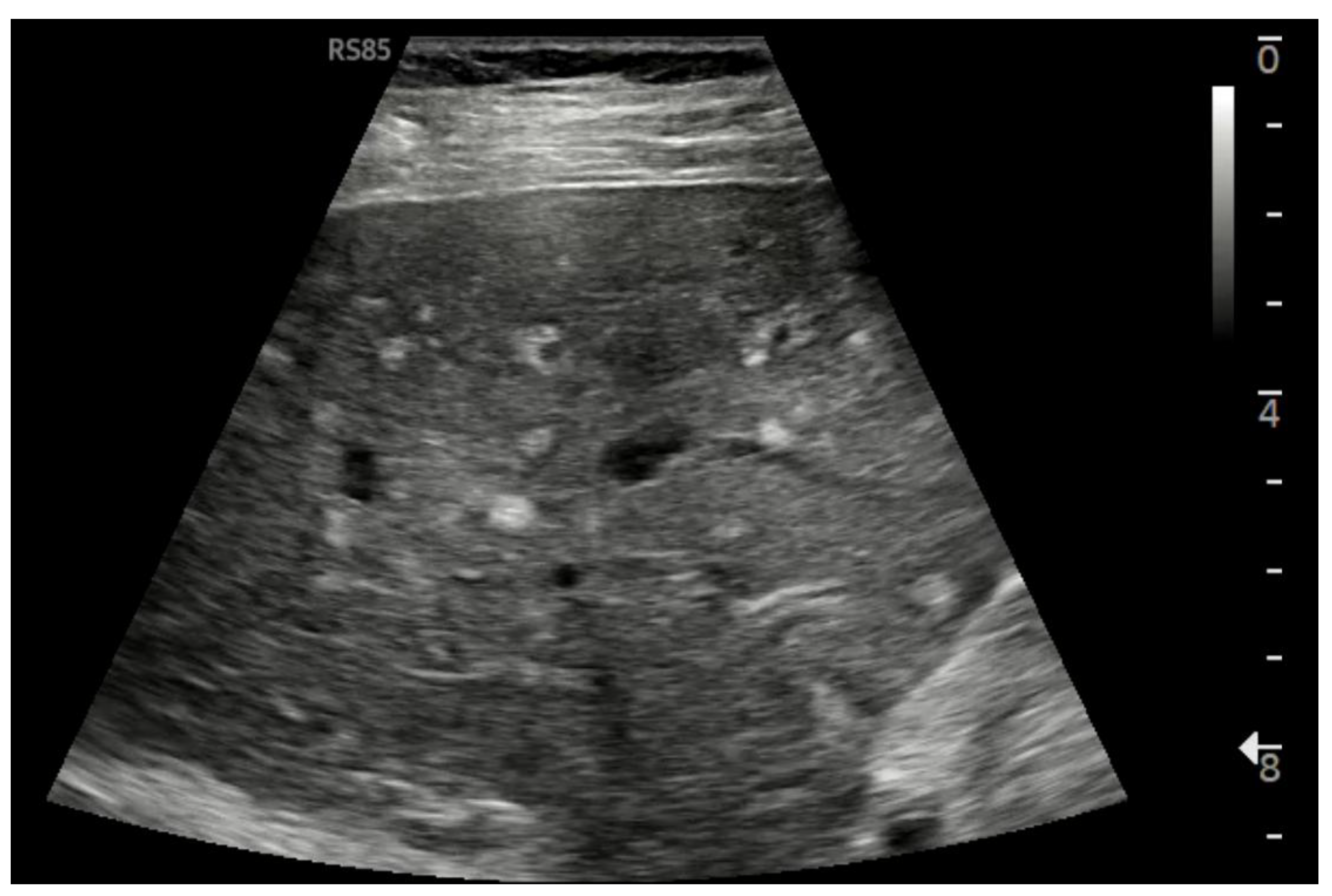

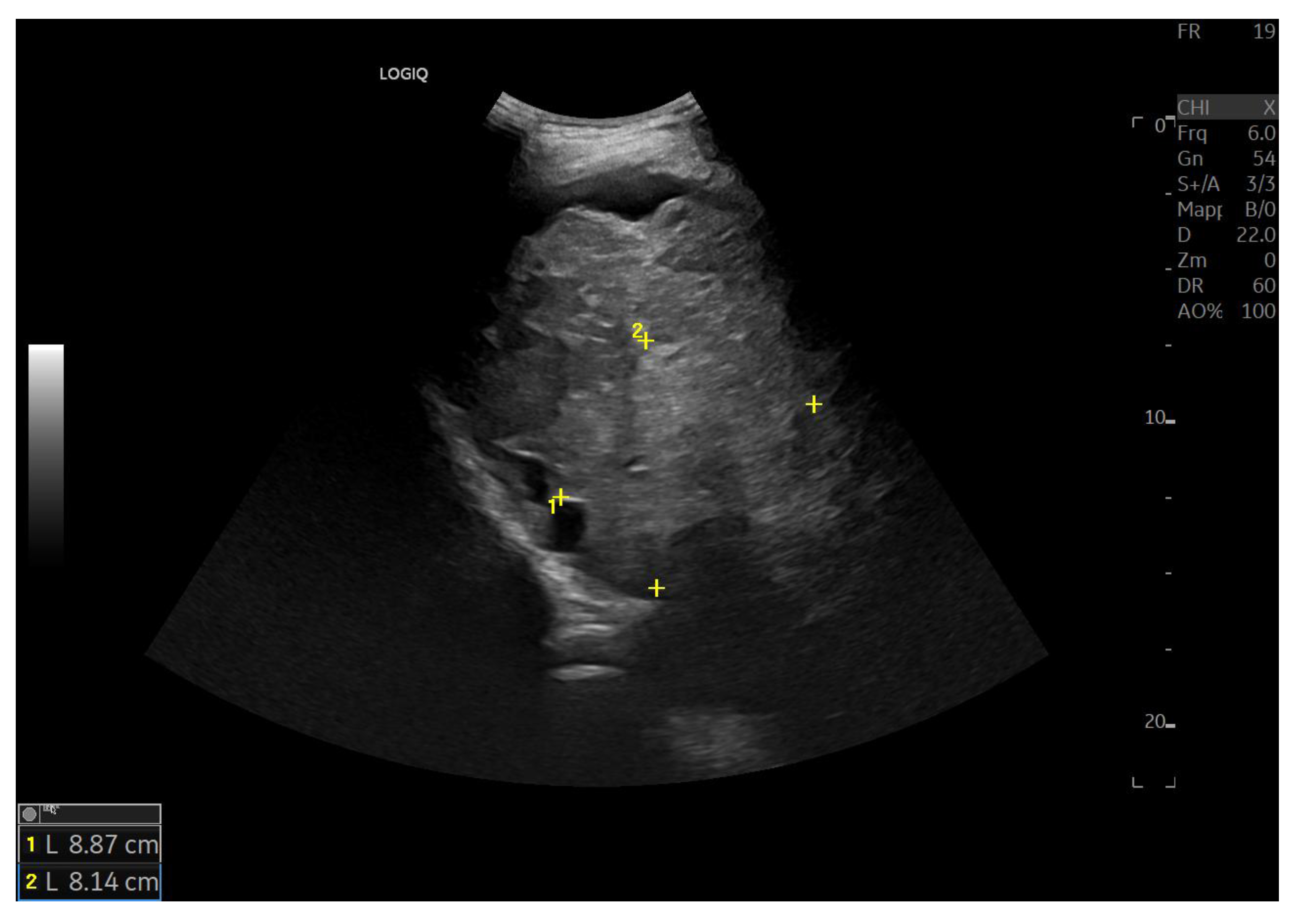

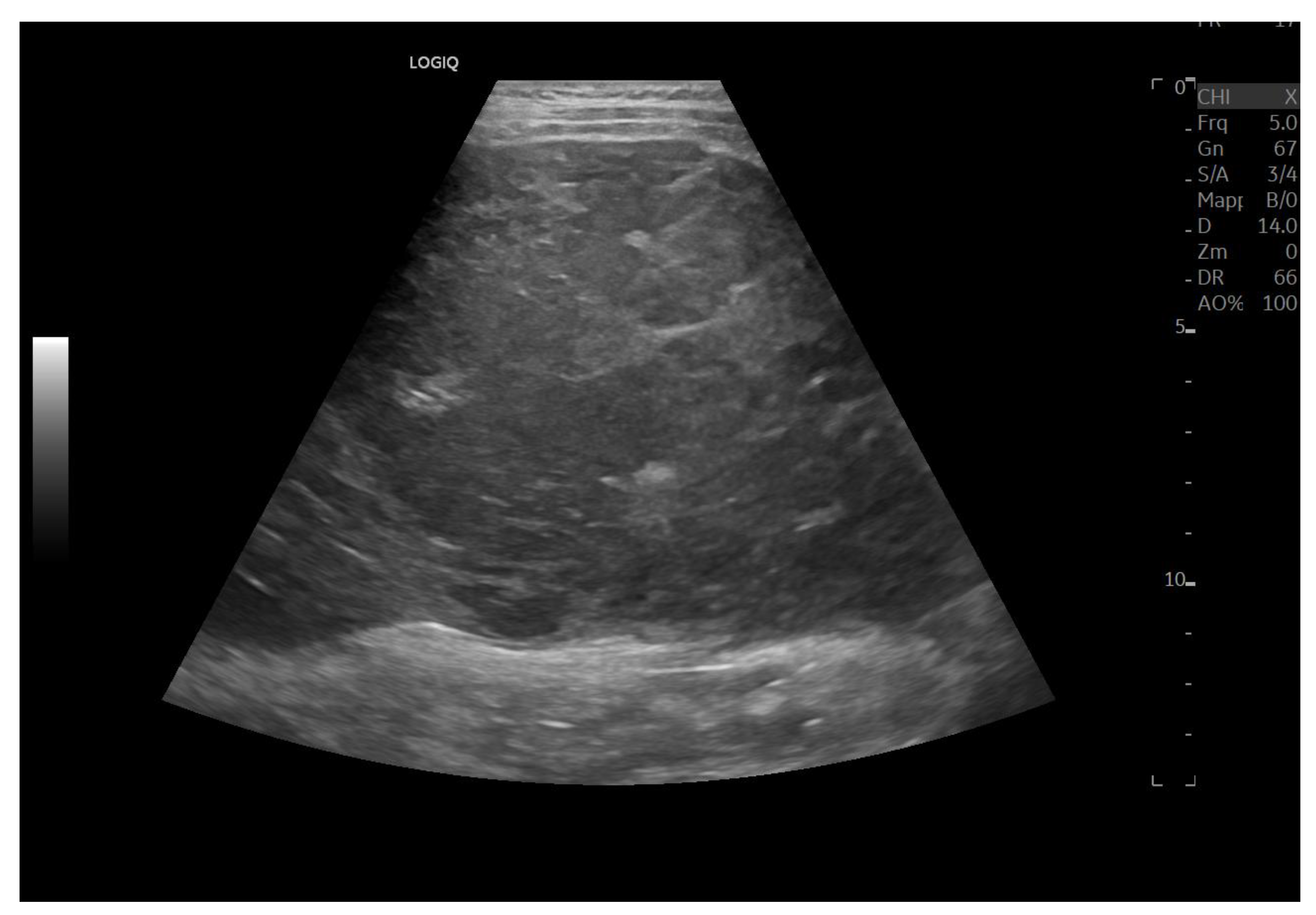

8. B-Mode Findings

8.1. Ultrasound Differentiation of Liver Nodules

9. Hepatocellular Carcinoma (Hcc) in Fald

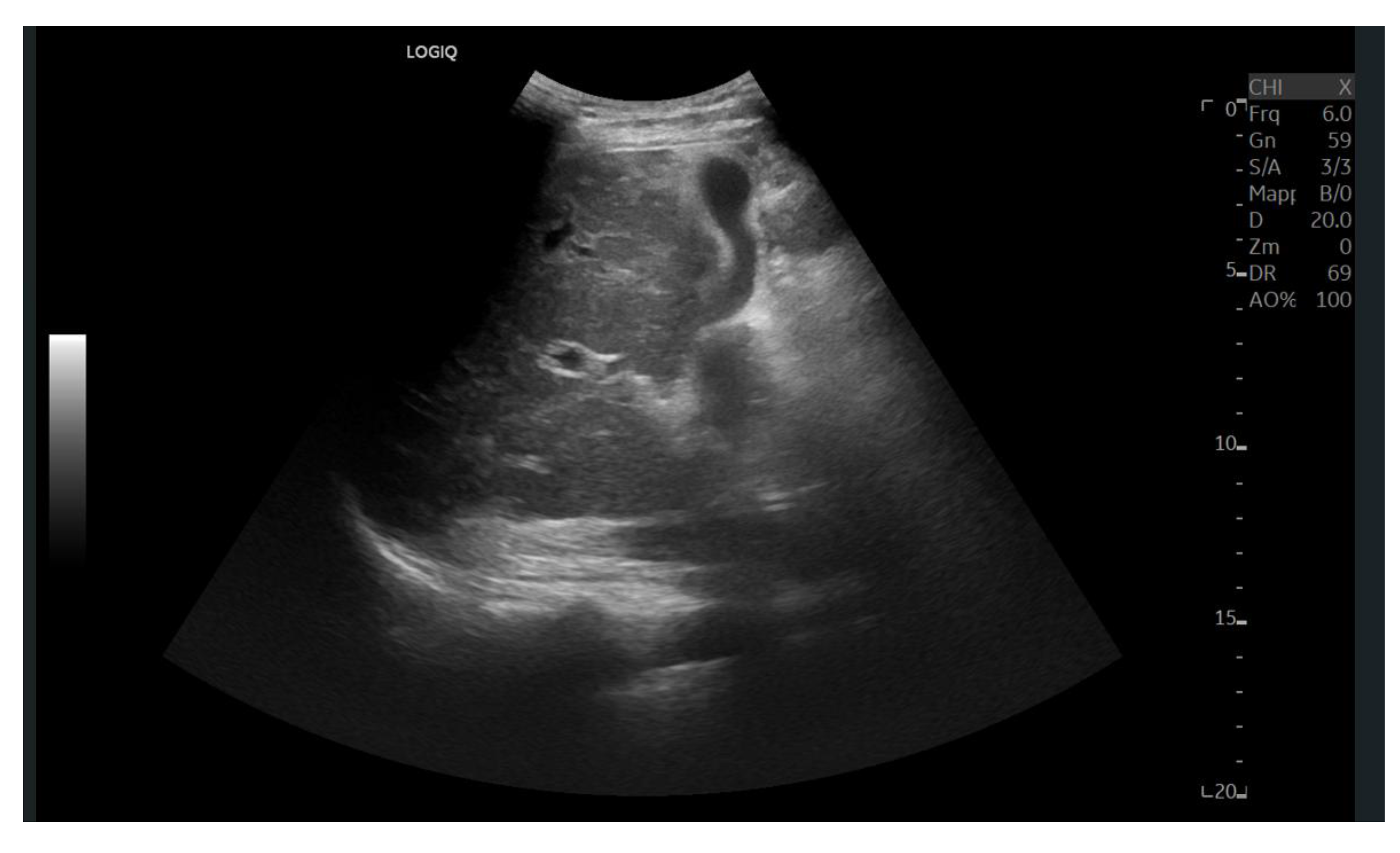

10. Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound (Ceus) in Fald

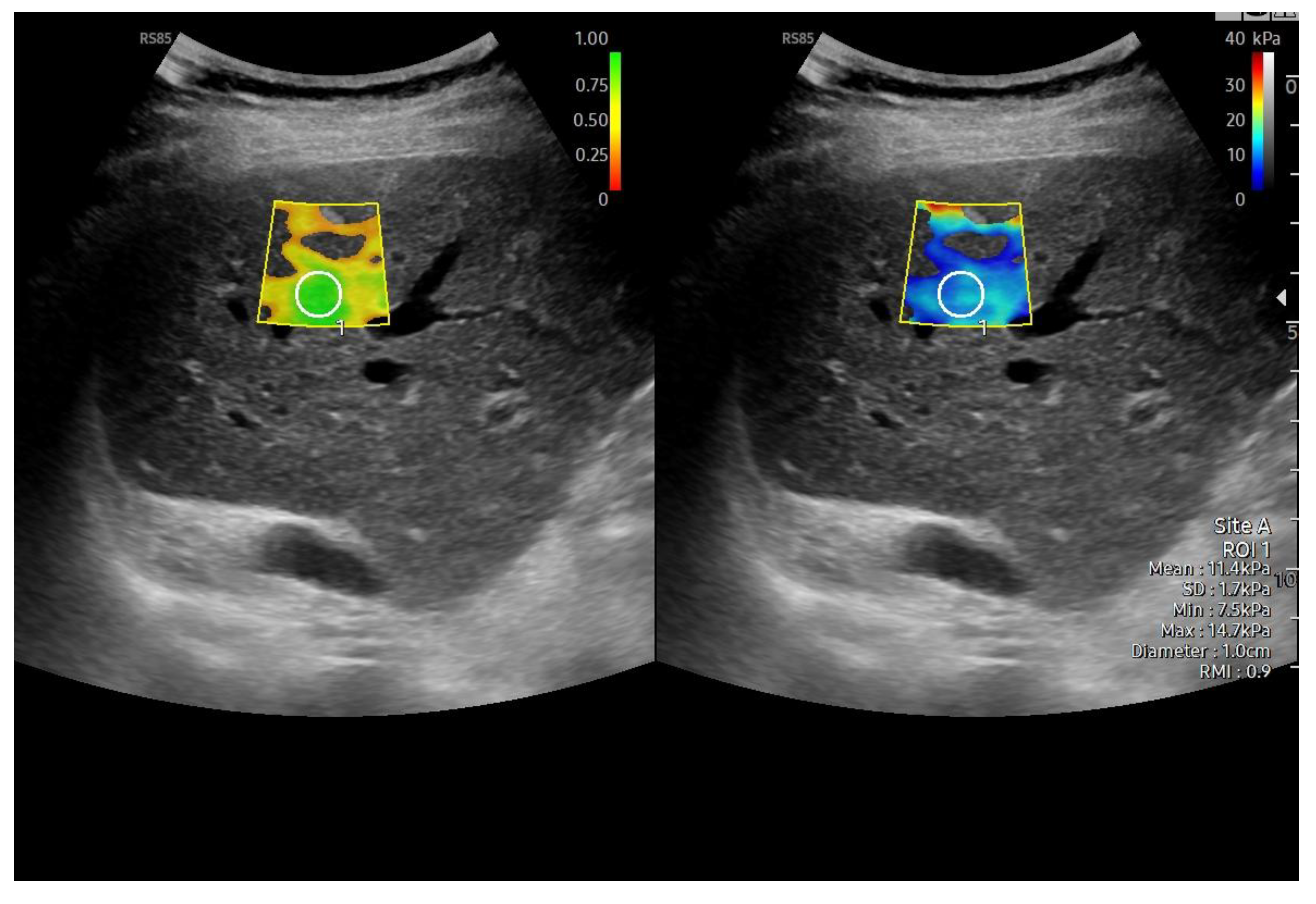

11. Liver & Spleen Stiffness

12. Liver Ultrasound-Guided Biopsy

13. Ultrasound Follow-Up

14. Conclusion

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kreutzer G, Galíndez E, Bono H, De Palma C, Laura JP. An operation for the correction of tricuspid atresia. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1973, 66, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björk VO, Olin CL, Bjarke BB, Thorén CA. Right atrial-right ventricular anastomosis for correction of tricuspid atresia. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1979, 77, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Téllez L, Payancé A, Tjwa E, Del Cerro MJ, Idorn L, Ovroutski S, et al. EASL-ERN position paper on liver involvement in patients with Fontan-type circulation. J Hepatol. 2023, 79, 1270–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao JY, Wales KM, d'Udekem Y, Celermajer DS, Cordina R, Majumdar A. Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Prognosis for Fontan-Associated Liver Disease: A Systematic Review and Exploratory Meta-Analysis. JACC Adv. 2025, 4, 101694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon-Walker TT, Bove K, Veldtman G. Fontan-associated liver disease: A review. J Cardiol. 2019, 74, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emamaullee J, Martin S, Goldbeck C, Rocque B, Barbetta A, Kohli R, et al. Evaluation of Fontan-associated Liver Disease and Ethnic Disparities in Long-term Survivors of the Fontan Procedure: A Population-based Study. Ann Surg. 2022, 276, 482–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilscher MB, Johnson JN. Fontan-Associated Liver Disease. Semin Liver Dis. 2025, 45, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ignee A, Gebel M, Caspary WF, Dietrich CF. [Doppler imaging of hepatic vessels - review]. Z Gastroenterol. 2002, 40, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich CF, Lee JH, Gottschalk R, Herrmann G, Sarrazin C, Caspary WF, et al. Hepatic and portal vein flow pattern in correlation with intrahepatic fat deposition and liver histology in patients with chronic hepatitis C. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998, 171, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonetto DA, Yang HY, Yin M, de Assuncao TM, Kwon JH, Hilscher M, et al. Chronic passive venous congestion drives hepatic fibrogenesis via sinusoidal thrombosis and mechanical forces. Hepatology. 2015, 61, 648–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilscher MB, Sehrawat T, Arab JP, Zeng Z, Gao J, Liu M, et al. Mechanical Stretch Increases Expression of CXCL1 in Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells to Recruit Neutrophils, Generate Sinusoidal Microthombi, and Promote Portal Hypertension. Gastroenterology. 2019, 157, 193–209.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, H. LSEC stretch promotes fibrosis during hepatic vascular congestion. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019, 16, 262–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietrich CF, Trenker C, Fontanilla T, Görg C, Hausmann A, Klein S, et al. New Ultrasound Techniques Challenge the Diagnosis of Sinusoidal Obstruction Syndrome. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2018, 44, 2171–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra H, Wolff D, van Melle JP, Bartelds B, Willems TP, Oudkerk M, et al. Diminished liver microperfusion in Fontan patients: A biexponential DWI study. PLoS One. 2017, 12, e0173149. [Google Scholar]

- Durongpisitkul K, Driscoll DJ, Mahoney DW, Wollan PC, Mottram CD, Puga FJ, et al. Cardiorespiratory response to exercise after modified Fontan operation: determinants of performance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997, 29, 785–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohuchi H, Mori A, Nakai M, Fujimoto K, Iwasa T, Sakaguchi H, et al. Pulmonary Arteriovenous Fistulae After Fontan Operation: Incidence, Clinical Characteristics, and Impact on All-Cause Mortality. Front Pediatr. 2022, 10, 713219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daems JJN, Attard C, Van Den Helm S, Breur J, D'Udekem Y, du Plessis K, et al. Cross-sectional assessment of haemostatic profile and hepatic dysfunction in Fontan patients. Open Heart.

- Skubera M, Gołąb A, Plicner D, Natorska J, Ząbczyk M, Trojnarska O, et al. Properties of Plasma Clots in Adult Patients Following Fontan Procedure: Relation to Clot Permeability and Lysis Time-Multicenter Study. J Clin Med.

- McCrindle BW, Michelson AD, Van Bergen AH, Suzana Horowitz E, Pablo Sandoval J, Justino H, et al. Thromboprophylaxis for Children Post-Fontan Procedure: Insights From the UNIVERSE Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e021765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong J, Tanaka M, Iwakiri Y. Hepatic lymphatic vascular system in health and disease. J Hepatol. 2022, 77, 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka M, Iwakiri Y. Lymphatics in the liver. Curr Opin Immunol. 2018, 53, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox DA, Ginde S, Tweddell JS, Earing MG. Outcomes of a hepatitis C screening protocol in at-risk adults with prior cardiac surgery. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2014, 5, 503–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lange C, Möller T, Hebelka H. Fontan-associated liver disease: Diagnosis, surveillance, and management. Front Pediatr. 2023, 11, 1100514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiesewetter CH, Sheron N, Vettukattill JJ, Hacking N, Stedman B, Millward-Sadler H, et al. Hepatic changes in the failing Fontan circulation. Heart. 2007, 93, 579–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnoletti G, Ferraro G, Bordese R, Marini D, Gala S, Bergamasco L, et al. Fontan circulation causes early, severe liver damage. Should we offer patients a tailored strategy? Int J Cardiol. 2016, 209, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Amico G, De Franchis R. Upper digestive bleeding in cirrhosis. Post-therapeutic outcome and prognostic indicators. Hepatology. 2003, 38, 599–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohuchi, H. What are the mechanisms for FALD and how can we prevent the progression? Int J Cardiol. 2018, 273, 121–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen JH, Khodami JK, Moritz JD, Rinne K, Voges I, Scheewe J, et al. Surveillance of Fontan Associated Liver Disease in Childhood and Adolescence. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2022, 34, 642–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillman JR, Trout AT, Alsaied T, Gupta A, Lubert AM. Imaging of Fontan-associated liver disease. Pediatr Radiol. 2020, 50, 1528–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae JM, Jeon TY, Kim JS, Kim S, Hwang SM, Yoo SY, et al. Fontan-associated liver disease: Spectrum of US findings. Eur J Radiol. 2016, 85, 850–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koizumi Y, Hirooka M, Tanaka T, Watanabe T, Yoshida O, Tokumoto Y, et al. Noninvasive ultrasound technique for assessment of liver fibrosis and cardiac function in Fontan-associated liver disease: diagnosis based on elastography and hepatic vein waveform type. J Med Ultrason (2001). 2021, 48, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown MJ, Kolbe AB, Hull NC, Hilscher M, Kamath PS, Yalon M, et al. Imaging of Fontan-Associated Liver Disease. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2024, 48, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths ER, Lambert LM, Ou Z, Shaaban A, Rezvani M, Carlo WF, et al. Fontan-associated liver disease after heart transplant. Pediatr Transplant. 2023, 27, e14435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid MU, Frenkel Y, Kuc N, Golowa Y, Cynamon J. Transfemoral-Transcaval Liver Biopsy (TFTC) and Transjugular Liver Biopsy (TJLB) in Patients with Fontan-Associated Liver Disease (FALD). Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2024, 47, 875–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borquez AA, Silva-Sepulveda J, Lee JW, Vavinskaya V, Vodkin I, El-Sabrout H, et al. Transjugular liver biopsy for Fontan associated liver disease surveillance: Technique, outcomes and hemodynamic correlation. Int J Cardiol. 2021, 328, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francalanci P, Giovannoni I, Tancredi C, Gagliardi MG, Palmieri R, Brancaccio G, et al. Histopathological Spectrum and Molecular Characterization of Liver Tumors in the Setting of Fontan-Associated Liver Disease. Cancers (Basel).

- Emamaullee J, Khan S, Weaver C, Goldbeck C, Yanni G, Kohli R, et al. Non-invasive biomarkers of Fontan-associated liver disease. JHEP Rep. 2021, 3, 100362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feeley M, Hopkins K, Grinspan LT, Schiano T, Love B, Chan A, et al. Challenges in Accurate Diagnosis of HCC in FALD: A Case Series. Pediatr Cardiol. 2023, 44, 1447–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Amato J, Bianco EZ, Camilleri J, Debattista E, Ellul P. Hepatocellular carcinoma in Fontan-associated liver disease. Ann Gastroenterol. 2025, 38, 133–142. [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich CF, Shi L, Löwe A, Dong Y, Potthoff A, Sparchez Z, et al. Conventional ultrasound for diagnosis of hepatic steatosis is better than believed. Z Gastroenterol. 2022, 60, 1235–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatore V, Borghi A, Peri E, Colecchia A, Li Bassi S, Montrone L, et al. Relationship between hepatic haemodynamics assessed by Doppler ultrasound and liver stiffness. Dig Liver Dis. 2012, 44, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng RQ, Wang QH, Lu MD, Xie SB, Ren J, Su ZZ, et al. Liver fibrosis in chronic viral hepatitis: an ultrasonographic study. World journal of gastroenterology. 2003, 9, 2484–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seol JH, Song J, Kim SJ, Ko H, Na JY, Cho MJ, et al. Clinical predictors and noninvasive imaging in Fontan-associated liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatol Commun.

- Garagiola ML, Tan SB, Alonso-Gonzalez R, O'Brien CM. Liver Imaging in Fontan Patients: How Does Ultrasound Compare to Cross-Sectional Imaging? JACC Adv. 2024, 3, 101357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thrane KJ, Müller LSO, Suther KR, Thomassen KS, Holmström H, Thaulow E, et al. Spectrum of Fontan-associated liver disease assessed by MRI and US in young adolescents. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2021, 46, 3205–3216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu X, Han L, Zhou Z, Tu J, Ma J, Chen J. Effect of liver abnormalities on mortality in Fontan patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2024, 24, 385. [Google Scholar]

- Heering G, Lebovics N, Agarwal R, Frishman WH, Lebovics E. Fontan-Associated Liver Disease: A Review. Cardiol Rev.

- Wells ML, Fenstad ER, Poterucha JT, Hough DM, Young PM, Araoz PA, et al. Imaging Findings of Congestive Hepatopathy. Radiographics. 2016, 36, 1024–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatsuka T, Soroida Y, Nakagawa H, Shindo T, Sato M, Soma K, et al. Identification of liver fibrosis using the hepatic vein waveform in patients with Fontan circulation. Hepatol Res. 2019, 49, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannini E, Botta F, Borro P, Risso D, Romagnoli P, Fasoli A, et al. Platelet count/spleen diameter ratio: proposal and validation of a non-invasive parameter to predict the presence of oesophageal varices in patients with liver cirrhosis. Gut. 2003, 52, 1200–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsia TY, Khambadkone S, Deanfield JE, Taylor JF, Migliavacca F, De Leval MR. Subdiaphragmatic venous hemodynamics in the Fontan circulation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001, 121, 436–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsia TY, Khambadkone S, Redington AN, De Leval MR. Instantaneous pressure-flow velocity relations of systemic venous return in patients with univentricular circulation. Heart. 2000, 83, 583. [Google Scholar]

- Hsia TY, Khambadkone S, Redington AN, de Leval MR. Effect of fenestration on the sub-diaphragmatic venous hemodynamics in the total-cavopulmonary connection. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2001, 19, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNaughton DA, Abu-Yousef MM. Doppler US of the liver made simple. Radiographics. 2011, 31, 161–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno FL, Hagan AD, Holmen JR, Pryor TA, Strickland RD, Castle CH. Evaluation of size and dynamics of the inferior vena cava as an index of right-sided cardiac function. Am J Cardiol. 1984, 53, 579–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camposilvan S, Milanesi O, Stellin G, Pettenazzo A, Zancan L, D'Antiga L. Liver and cardiac function in the long term after Fontan operation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008, 86, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutty SS, Peng Q, Danford DA, Fletcher SE, Perry D, Talmon GA, et al. Increased hepatic stiffness as consequence of high hepatic afterload in the Fontan circulation: a vascular Doppler and elastography study. Hepatology. 2014, 59, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cura M, Haskal Z, Lopera J. Diagnostic and interventional radiology for Budd-Chiari syndrome. Radiographics. 2009, 29, 669–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Téllez L, Rodríguez de Santiago E, Minguez B, Payance A, Clemente A, Baiges A, et al. Prevalence, features and predictive factors of liver nodules in Fontan surgery patients: The VALDIG Fonliver prospective cohort. J Hepatol. 2020, 72, 702–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallihan DB, Podberesky DJ. Hepatic pathology after Fontan palliation: spectrum of imaging findings. Pediatr Radiol. 2013, 43, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çolaklar A, Lehnert SJ, Tirkes T. Benign Hepatic Nodules Mimicking Hepatocellular Carcinoma in the Setting of Fontan-associated Liver Disease: A Case Report. Euroasian J Hepatogastroenterol. 2020, 10, 42–44. [Google Scholar]

- Kogiso T, Tokushige K. Fontan-associated liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma in adults. Sci Rep. 2020, 10, 21742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiina Y, Inai K, Sakai R, Tokushige K, Nagao M. Hepatocellular carcinoma and focal nodular hyperplasia in patients with Fontan-associated liver disease: characterisation using dynamic gadolinium ethoxybenzyl diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid-enhanced MRI. Clin Radiol. 2023, 78, e197–e203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandwana SB, Olaiya B, Cox K, Sahu A, Mittal P. Abdominal Imaging Surveillance in Adult Patients After Fontan Procedure: Risk of Chronic Liver Disease and Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2018, 47, 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josephus Jitta D, Wagenaar LJ, Mulder BJ, Guichelaar M, Bouman D, van Melle JP. Three cases of hepatocellular carcinoma in Fontan patients: Review of the literature and suggestions for hepatic screening. Int J Cardiol. 2016, 206, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum J, Vrazas J, Lane GK, Hardikar W. Cardiac cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in a 13-year-old treated with doxorubicin microbead transarterial chemoembolization. J Paediatr Child Health. 2012, 48, E140–E143. [Google Scholar]

- Möller T, Klungerbo V, Diab S, Holmstrøm H, Edvardsen E, Grindheim G, et al. Circulatory Response to Rapid Volume Expansion and Cardiorespiratory Fitness in Fontan Circulation. Pediatr Cardiol. 2022, 43, 903–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosch IB, Andresen B, Diep LM, Diseth TH, Möller T. Quality of life and emotional vulnerability in a national cohort of adolescents living with Fontan circulation. Cardiol Young. 2022, 32, 874–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim TH, Yang HK, Jang HJ, Yoo SJ, Khalili K, Kim TK. Abdominal imaging findings in adult patients with Fontan circulation. Insights Imaging. 2018, 9, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells ML, Hough DM, Fidler JL, Kamath PS, Poterucha JT, Venkatesh SK. Benign nodules in post-Fontan livers can show imaging features considered diagnostic for hepatocellular carcinoma. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2017, 42, 2623–2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rychik J, Veldtman G, Rand E, Russo P, Rome JJ, Krok K, et al. The precarious state of the liver after a Fontan operation: summary of a multidisciplinary symposium. Pediatr Cardiol. 2012, 33, 1001–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu FM, Kogon B, Earing MG, Aboulhosn JA, Broberg CS, John AS, et al. Liver health in adults with Fontan circulation: A multicenter cross-sectional study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017, 153, 656–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reig M, Forner A, Ávila MA, Ayuso C, Mínguez B, Varela M, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Update of the consensus document of the AEEH, AEC, SEOM, SERAM, SERVEI, and SETH. Med Clin (Barc). 2021, 156, 463.e1–e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zander T, Zadeh ES, Möller K, Goerg C, Correas JM, Chaubal N, et al. Comments and illustrations of the WFUMB CEUS liver guidelines: Rare focal liver lesion - infectious parasitic, fungus. Med Ultrason. 2023, 25, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong Y, Wang WP, Zadeh ES, Möller K, Görg C, Berzigotti A, et al. Comments and illustrations of the WFUMB CEUS liver guidelines: Rare benign focal liver lesion, part I. Med Ultrason. 2024, 26, 50–62. [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y, Guggisberg E, Wang WP, Zadeh ES, Görg C, Möller K, et al. Comments and illustrations of the WFUMB CEUS liver guidelines: Rare benign focal liver lesion, part II. Med Ultrason. 2024, 26, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulut OP, Romero R, Mahle WT, McConnell M, Braithwaite K, Shehata BM, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging identifies unsuspected liver abnormalities in patients after the Fontan procedure. J Pediatr. 2013, 163, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wettere M, Purcell Y, Bruno O, Payancé A, Plessier A, Rautou PE, et al. Low specificity of washout to diagnose hepatocellular carcinoma in nodules showing arterial hyperenhancement in patients with Budd-Chiari syndrome. J Hepatol. 2019, 70, 1123–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang A, Abukasm K, Moura Cunha G, Song B, Wang J, Wagner M, et al. Imaging of hepatocellular carcinoma: a pilot international survey. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2021, 46, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich CF, Dong Y, Kono Y, Caraiani C, Sirlin CB, Cui XW, et al. LI-RADS ancillary features on contrast-enhanced ultrasonography. Ultrasonography. 2020, 39, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraioli G, Barr RG, Berzigotti A, Sporea I, Wong VW, Reiberger T, et al. WFUMB Guideline/Guidance on Liver Multiparametric Ultrasound: Part 1. Update to 2018 Guidelines on Liver Ultrasound Elastography. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2024, 50, 1071–1087. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraioli G, Barr RG, Farrokh A, Radzina M, Cui XW, Dong Y, et al. How to perform shear wave elastography. Part I. Med Ultrason. 2022, 24, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraioli G, Barr RG, Farrokh A, Radzina M, Cui XW, Dong Y, et al. How to perform shear wave elastography. Part II. Med Ultrason. 2022, 24, 196–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich CF, Shi L, Wei Q, Dong Y, Cui XW, Löwe A, et al. What does liver elastography measure? Technical aspects and methodology. Minerva Gastroenterol (Torino). 2021, 67, 129–140. [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich CF, Ferraioli G, Sirli R, Popescu A, Sporea I, Pienar C, et al. General advice in ultrasound based elastography of pediatric patients. Med Ultrason. 2019, 21, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraioli G, Wong VW, Castera L, Berzigotti A, Sporea I, Dietrich CF, et al. Liver Ultrasound Elastography: An Update to the World Federation for Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology Guidelines and Recommendations. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2018, 44, 2419–2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich CF, Bamber J, Berzigotti A, Bota S, Cantisani V, Castera L, et al. EFSUMB Guidelines and Recommendations on the Clinical Use of Liver Ultrasound Elastography, Update 2017 (Long Version). Ultraschall Med. 2017, 38, e16–e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deorsola L, Aidala E, Cascarano MT, Valori A, Agnoletti G, Pace Napoleone C. Liver stiffness modifications shortly after total cavopulmonary connection. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2016, 23, 513–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egbe A, Miranda WR, Connolly HM, Khan AR, Al-Otaibi M, Venkatesh SK, et al. Temporal changes in liver stiffness after Fontan operation: Results of serial magnetic resonance elastography. Int J Cardiol. 2018, 258, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munsterman ID, Duijnhouwer AL, Kendall TJ, Bronkhorst CM, Ronot M, van Wettere M, et al. The clinical spectrum of Fontan-associated liver disease: results from a prospective multimodality screening cohort. Eur Heart J. 2019, 40, 1057–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleiger A, Salzmann M, Kramer P, Danne F, Schubert S, Bassir C, et al. Severity of Fontan-Associated Liver Disease Correlates with Fontan Hemodynamics. Pediatr Cardiol. 2020, 41, 736–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemello L, Padalino M, Zanon C, Benvegnu L, Biffanti R, Mancuso D, et al. Role of Transient Elastography to Stage Fontan-Associated Liver Disease (FALD) in Adults with Single Ventricle Congenital Heart Disease Correction. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis.

- Nagasawa T, Kuroda H, Abe T, Saiki H, Takikawa Y. Shear wave dispersion to assess liver disease progression in Fontan-associated liver disease. PLoS One. 2022, 17, e0271223. [Google Scholar]

- Gill M, Mudaliar S, Prince D, Than NN, Cordina R, Majumdar A. Poor correlation of 2D shear wave elastography and transient elastography in Fontan-associated liver disease: A head-to-head comparison. JGH Open. 2023, 7, 690–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarasvaraparn C, Thoe J, Rodenbarger A, Masuoka H, Payne RM, Markham LW, et al. Biomarkers of fibrosis and portal hypertension in Fontan-associated liver disease in children and adults. Dig Liver Dis. 2024, 56, 1335–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolia R, Alremawi S, Noble C, Justo R, Ward C, Lewindon PJ. Shear-wave elastography for monitoring Fontan-associated liver disease: A prospective cohort study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2024, 79, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Téllez L, Rincón D, Payancé A, Jaillais A, Lebray P, Rodríguez de Santiago E, et al. Non-invasive assessment of severe liver fibrosis in patients with Fontan-associated liver disease: The VALDIG-EASL FONLIVER cohort. J Hepatol. 2025, 82, 480–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadros M, Abadía M, Castillo P, Martín-Arranz MD, Gonzalo N, Romero M, et al. Role of transient elastography in the diagnosis and prognosis of Fontan-associated liver disease. World journal of gastroenterology. 2025, 31, 103178. [Google Scholar]

- Imoto K, Goya T, Azuma Y, Hioki T, Aoyagi T, Nagata H, et al. Strain elastography for detecting advanced Fontan-associated liver disease: a retrospective study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2025, 25, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakae H, Tanoue S, Mawatari S, Oda K, Taniyama O, Toyodome A, et al. Fontan-Associated Liver Disease: Predictors of Elevated Liver Stiffness and the Role of Transient Elastography in Long-Term Follow-Up. Cureus. 2025, 17, e85336. [Google Scholar]

- Abadeer M, Greer J, Reddy S, Divekar A, Schooler GR, Fares M, et al. The Importance of Hepatic Surveillance After Single-Ventricle Palliation: An Interventional Study Validating Liver Elastography. Pediatr Cardiol.

- Lo Yau Y, Coppola JA, Lopez-Colon D, Purlee M, Vyas H, Saulino DM, et al. Correlation of Liver Fibrosis on Ultrasound Elastography and Liver Biopsy After Fontan Operation: Is Non-invasive Always Better? Pediatr Cardiol. Pediatr Cardiol. 2025.

- Yau YL, Purlee MS, Brinkley LM, Gupta D, Saulino DM, Lopez-Colon D, et al. A Tense Race: Correlation of Liver Stiffness with Ultrasound Elastography and Hemodynamics in Fontan Patients. Congenit Heart Dis. 2025, 20, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serai SD, Elsingergy MM, Hartung EA, Otero HJ. Liver and spleen volume and stiffness in patients post-Fontan procedure and patients with ARPKD compared to normal controls. Clin Imaging. 2022, 89, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padalino MA, Chemello L, Cavalletto L, Angelini A, Fedrigo M. Prognostic Value of Liver and Spleen Stiffness in Patients with Fontan Associated Liver Disease (FALD): A Case Series with Histopathologic Comparison. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis.

- Venkatakrishna SSB, Ghosh A, Gonzalez IA, Wilkins BJ, Serai SD, Rand EB, et al. Spleen shear wave elastography measurements do not correlate with histological grading of liver fibrosis in Fontan physiology: a preliminary investigation. Pediatr Radiol. 2024, 54, 1998–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliyev B, Bayramoglu Z, Nişli K, Omeroğlu RE, Dindar A. Quantification of Hepatic and Splenic Stiffness After Fontan Procedure in Children and Clinical Implications. Ultrasound Q. 2020, 36, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenssen C, Hocke M, Fusaroli P, Gilja OH, Buscarini E, Havre RF, et al. EFSUMB Guidelines on Interventional Ultrasound (INVUS), Part IV - EUS-guided Interventions: General aspects and EUS-guided sampling (Long Version). Ultraschall Med. 2016, 37, E33–E76. [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich CF, Lorentzen T, Appelbaum L, Buscarini E, Cantisani V, Correas JM, et al. EFSUMB Guidelines on Interventional Ultrasound (INVUS), Part III - Abdominal Treatment Procedures (Long Version). Ultraschall Med. 2016, 37, E1–e32. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall TJ, Stedman B, Hacking N, Haw M, Vettukattill JJ, Salmon AP, et al. Hepatic fibrosis and cirrhosis in the Fontan circulation: a detailed morphological study. J Clin Pathol. 2008, 61, 504–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg DJ, Surrey LF, Glatz AC, Dodds K, O'Byrne ML, Lin HC, et al. Hepatic Fibrosis Is Universal Following Fontan Operation, and Severity is Associated With Time From Surgery: A Liver Biopsy and Hemodynamic Study. J Am Heart Assoc.

- Castéra L, Foucher J, Bernard PH, Carvalho F, Allaix D, Merrouche W, et al. Pitfalls of liver stiffness measurement: a 5-year prospective study of 13,369 examinations. Hepatology. 2010, 51, 828–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Souza BA, Fuller S, Gleason LP, Hornsby N, Wald J, Krok K, et al. Single-center outcomes of combined heart and liver transplantation in the failing Fontan. Clin Transplant.

- Rychik J, Atz AM, Celermajer DS, Deal BJ, Gatzoulis MA, Gewillig MH, et al. Evaluation and Management of the Child and Adult With Fontan Circulation: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019, 140, e234–e84. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon JS, Lee DH, Cho EJ, Song MK, Choi YH, Kim GB, et al. Risk of Liver Cirrhosis and Hepatocellular Carcinoma after Fontan Operation: A Need for Surveillance. Cancers (Basel).

- Pundi K, Pundi KN, Kamath PS, Cetta F, Li Z, Poterucha JT, et al. Liver Disease in Patients After the Fontan Operation. Am J Cardiol. 2016, 117, 456–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogiso T, Sagawa T, Taniai M, Shimada E, Inai K, Shinohara T, et al. Risk factors for Fontan-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS One. 2022, 17, e0270230. [Google Scholar]

- Sagawa T, Kogiso T, Sugiyama H, Hashimoto E, Yamamoto M, Tokushige K. Characteristics of hepatocellular carcinoma arising from Fontan-associated liver disease. Hepatol Res. 2020, 50, 853–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamura K, Sakamoto I, Morihana E, Hirata Y, Nagata H, Yamasaki Y, et al. Elevated non-invasive liver fibrosis markers and risk of liver carcinoma in adult patients after repair of tetralogy of Fallot. Int J Cardiol. 2019, 287, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kogiso T, Tokushige K. Fontan-associated liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma in adults. Scientific Reports. 2020, 10, 21742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Possner M, Gordon-Walker T, Egbe AC, Poterucha JT, Warnes CA, Connolly HM, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma and the Fontan circulation: Clinical presentation and outcomes. Int J Cardiol. 2021, 322, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Téllez L, Payancé A, Tjwa E, del Cerro MJ, Idorn L, Ovroutski S, et al. EASL-ERN position paper on liver involvement in patients with Fontan-type circulation. Journal of Hepatology. 2023, 79, 1270–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Phenotype | Ventricular Function | Fontan Pressure | Cardiac Index | Key clinical features | Prognosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SFP (Systolic) | Reduced | Variable | Low | Heart failure symptoms | Poor, high transplant risk |

| PFP (Preserved) | Normal | Elevated | Normal or mildly low | Systemic congestion | Intermediate |

| LFP (Lymphatic) | Variable | Normal or low | Variable | Protein-losing enteropathy, plastic bronchitis | High morbidity |

| NHP (Normal) | Normal | Normal | Normal | Nonspecific symptoms | Variable, challenging diagnosis |

| Feature | FALD vs Cardiac Cirrhosis | FALD vs Other Cirrhosis (e.g. viral, metabolic) |

|---|---|---|

| Pathophysiology | Passive hepatic congestion due to chronically elevated central venous pressure | Chronic injury leads to progressive fibrosis and cirrhosis |

| Histological findings | Sinusoidal dilation and perivenular fibrosis | Development of bridging fibrosis and nodular architecture in all |

| Imaging features | Hepatomegaly, heterogeneous liver texture, signs of venous congestion | Nodular surface, altered vascular flow patterns, and signs of portal hypertension |

| Clinical progression | Often indolent onset with progression over years | Progressive decompensation common to all advanced cirrhosis |

| Complications | Risk of HCC present in all advanced stages | HCC risk shared across etiologies |

| Portal hypertension | May develop in late stages due to sinusoidal and post-sinusoidal resistance | Common in all cirrhotic patterns, but from different hemodynamic origins. |

| Feature | FALD vs Cardiac Cirrhosis | FALD vs Other Cirrhosis (e.g. viral, metabolic) |

|---|---|---|

| Etiology | Congenital heart disease with Fontan circulation | Non-cardiac: viral hepatitis, alcohol, MASLD, autoimmune causes |

| Hemodynamics | Consistently elevated CVP due to absent sub-pulmonary ventricle | Typically unrelated to central venous pressure |

| Age of onset | Pediatric or adolescent onset due to congenital heart repair | Usually manifests in adulthood |

| Liver biochemistry | Mild, non-specific transaminase elevation; often preserved synthetic function | May show higher AST/ALT, and impaired bilirubin, albumin, INR in advanced stages |

| Histopathology | Patchy fibrosis with central congestion and sinusoidal dilation; portal tracts relatively spared | Portal-based fibrosis, lobular inflammation, steatosis or bile duct injury |

| Fibrosis pattern | Predominantly centrilobular with variable progression | Diffuse or periportal depending on underlying disease |

| Progressive dynamics | Slow, heterogeneous; shaped by Fontan physiology and systemic venous congestion | Related to ongoing inflammatory, toxic or metabolic insult |

| Imaging | Imaging Modality | FNH-like Nodules Features | Differential Clues from HCC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrasound | B-mode | Small, hyperechoic, sometimes multiple lesions | HCC may be iso- or hypoechoic, larger, with irregular margins |

| CEUS (Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound) | Hyperenhancement in arterial phase; centrifugal enhancement; central stellate vasculature; no washout | HCC often shows rapid washout in portal/late phase and lacks central stellate pattern | |

| CT | Arterial Phase | Hyperenhancing compared to liver parenchyma | HCC may also be hyperenhancing, but more likely to show irregular margins or washout later |

| Portal/Delayed Phase | Generally iso- or hyperattenuating; occasional mild washout due to parenchymal congestion | HCC often shows true washout, distinguishing it from regenerative nodules | |

| MRI | T1-weighted | Iso- or mildly hypointense; central scar hypointense | HCC is often more heterogeneous and may have intense arterial enhancement |

| T2-weighted | Iso- or mildly hyperintense; central scar hyperintense | HCC may be more heterogeneous, with areas of necrosis or hemorrhage | |

| Hepatobiliary Phase | Hyperintense due to hepatobiliary contrast retention (differentiates from HCC) | HCC typically appears hypointense due to lack of contrast uptake | |

| DWI | No diffusion restriction (helps distinguish from HCC) | HCC typically restricts diffusion (appears hyperintense on DWI) |

| Study | Sample Size | Modality | Comparator | Main Findings |

| Sakae et al. (2025) [100] | 37 | TE (FibroScan®) | Serum markers (FIB-4, GGT), clinical parameters | FIB-4, GGT, and age at Fontan were independently associated with elevated LSM; TE correlated with liver fibrosis risk. |

| Imoto et al. (2025) [99] | 46 | SWE, Platelet count, LFI | Liver biopsy results | Platelet <185k + LFI >2.21 predicted aFALD with high sensitivity; proposed a 2-step algorithm for screening. |

| Lo Yau et al. (2025) [102] | 29 | US elastography, Liver biopsy | METAVIR vs congestive hepatic fibrosis score | Weak correlation between US elastography and histologic fibrosis. 86% had METAVIR > F2; median shear wave 1.97 m/s. |

| Yau et al. (2025) [103] | 56 | SWE, Hemodynamic assessment | Cardiac catheterization, Echocardiography parameters | No significant correlation between SWE and pre-/post-Fontan hemodynamics. No association with systolic function or AV valve regurgitation on echo. Liver stiffness measurements appear independent of cardiac output parameters. |

| Cuadros et al. (2025) [98] | 91 | TE (FibroScan®) | Clinical outcomes, fibrosis markers | Elevated LSM predicted major events and mortality in Fontan patients; validated prognostic value of TE. |

| Téllez et al. (2025) [97] | 217 | TE, Biopsy, FonLiver score | Other non-invasive tests (APRI, FIB-4, MELD) | FonLiver score outperformed traditional markers; strong diagnostic tool combining TE and platelet count. |

| Bolia et al. (2024) [96] | 48 | SWE | Liver stiffness, biomarkers | SWE showed weak correlation with established FALD markers; limited predictive utility. |

| Jarasvaraparn et al. (2024) [95] | 66 | APRI, FIB-4, TE | Histologic and imaging findings | APRI and FIB-4 were moderately predictive in adults but not effective in children. |

| Gill et al. (2023) [94] | 25 | 2D SWE, TE | Liver stiffness measurements | Poor concordance between SWE and TE; questioned reliability of elastography. |

| Nagasawa et al. (2022) [93] | 27 | SWD, 2D SWE | Fibrosis stage (biopsy) | SWD more accurate than SWE for detecting significant fibrosis. |

| Chemello et al. (2021) [92] | 52 | TE | Portal hypertension and clinical stage | LS and LSPS effectively staged FALD and identified portal hypertension risk. |

| Schleiger et al. (2020) [91] | 145 | TE, FibroTest®, US | Fontan duration, clinical severity | Fibrosis scores strongly associated with Fontan duration and clinical severity. |

| Munsterman et al. (2019) [90] | 49 | US, TE, MRI/CT, Biopsy | Histology and imaging findings | Universal fibrosis found; varices and nodules inconsistently reflected severity. |

| Egbe et al. (2018) [89] | 22 | MRE | MELD score, outcomes | Annual MRE-LS progression correlated with worsening MELD and clinical outcomes. |

| Surveillance Component | AHA Recommendations (2019) | EASL-ERN Recommendations (2023) |

|---|---|---|

| Multidisciplinary Care Team | Fontan/single-ventricle clinics with experienced personnel | Specialized clinics with hepatologist, cardiologist, radiologist |

| Cardiac MRI | Every 2–3 years for anatomic and functional assessment | Every 2–3 years to evaluate Fontan flow and anatomy |

| CT Angiography | When clinically indicated | Not specifically emphasized unless MRI is contraindicated |

| Cardiac Catheterization | Every 10 years or when clinically indicated | When MRI contraindicated or invasive data needed |

| Liver Ultrasound + Elastography | Annual ultrasound with elastography | Annual surveillance as first-line imaging tool |

| Liver MRI with Hepatobiliary Contrast | Annual MRI from adolescence; use hepatobiliary contrast if biopsy is considered | Baseline at 10 years; repeat every 1–2 years in high-risk |

| Liver Biopsy | If imaging is inconclusive and LI-RADS fails to differentiate | Mandatory when malignancy cannot be ruled out by imaging alone |

| Serum AFP Monitoring | Use AFP >7 ng/dl as alert threshold; >10 ng/dl = high risk | AFP >10 ng/mL requires advanced imaging or biopsy |

| Timing of HCC Surveillance | Start 10 years after Fontan; consider earlier in high-risk patients | Begin at 10 years post-Fontan; earlier if MELD >19, APRI/FIB-4 elevated |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).