1. Introduction

Ultrasonography (US) is especially useful in percutaneous intravascular procedures as it provides accurate real-time visualization of vascular structures, enabling precise insertion of catheters or other instruments into the vessels, thereby reducing the risk of complications [

1]. At the end of the 20th century, percutaneous access to hepatic vessels was described as an alternative way for percutaneous intracardiac interventions [

2,

3]. The femoral vein or internal jugular veins are the current standard insertion sites; however, in cases of occlusion, agenesis, or other obstruction of these veins, transhepatic accesses can be a safe and effective therapeutic option [

4,

5]. Some researchers consider them to be a better option than standard insertion sites when performing single-access intracardiac procedures, such as left atrial catheterization, or when multiple simultaneous accesses are required, such as bilateral pulmonary artery branch stenosis or closure of large atrial septal defects without edge preservation [

6].

Many physicians may not be aware of the possibility of using transhepatic access, while others may avoid it due to concerns about potential complications such as intra/retroperitoneal bleeding, hemobilia, pneumothorax, pleural effusions, perforation of gall bladder or portal vein (PV) thrombosis [

7]. Furthermore, reliance on experience from the literature alone may not always be appropriate for each patient. Using US to visualize the vessel for transhepatic access can reduce the risk of failure and facilitate the selection of the most optimal access point. In addition to cardiac interventions, transhepatic approach can also be used to access the right anterior branch of the portal vein (RAB) when performing balloon angioplasty in PV stenosis or thrombosis [

8,

9]. Using US it is possible to personalize the best intravascular access points for specific intracardiac procedures. Our study used US to assess the anatomy of hepatic and portal veins. We also evaluated previously described access points and aimed to identify the best new accesses to the hepatic and the RAB vasculature for each individual using ultrasonography.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participant Eligibility

The study involved 100 Caucasian participants, 59 of whom were female and 41 were male. The inclusion criteria for the study was age between 18 and 65, while exclusion criteria included a history of liver and/or bile duct surgery, liver and/or bile duct biopsy, and other procedures that could potentially affect the anatomy of the studied area.

2.2. US Examination

The hepatic and portal veins variability and examination of access points were conducted using LOGIQ F8 GE US with a 3Sc transducer (1-3MHz). Each examination was reviewed and approved through consensus by all the authors. During the examination, the participants were in a semi-Fowler position.

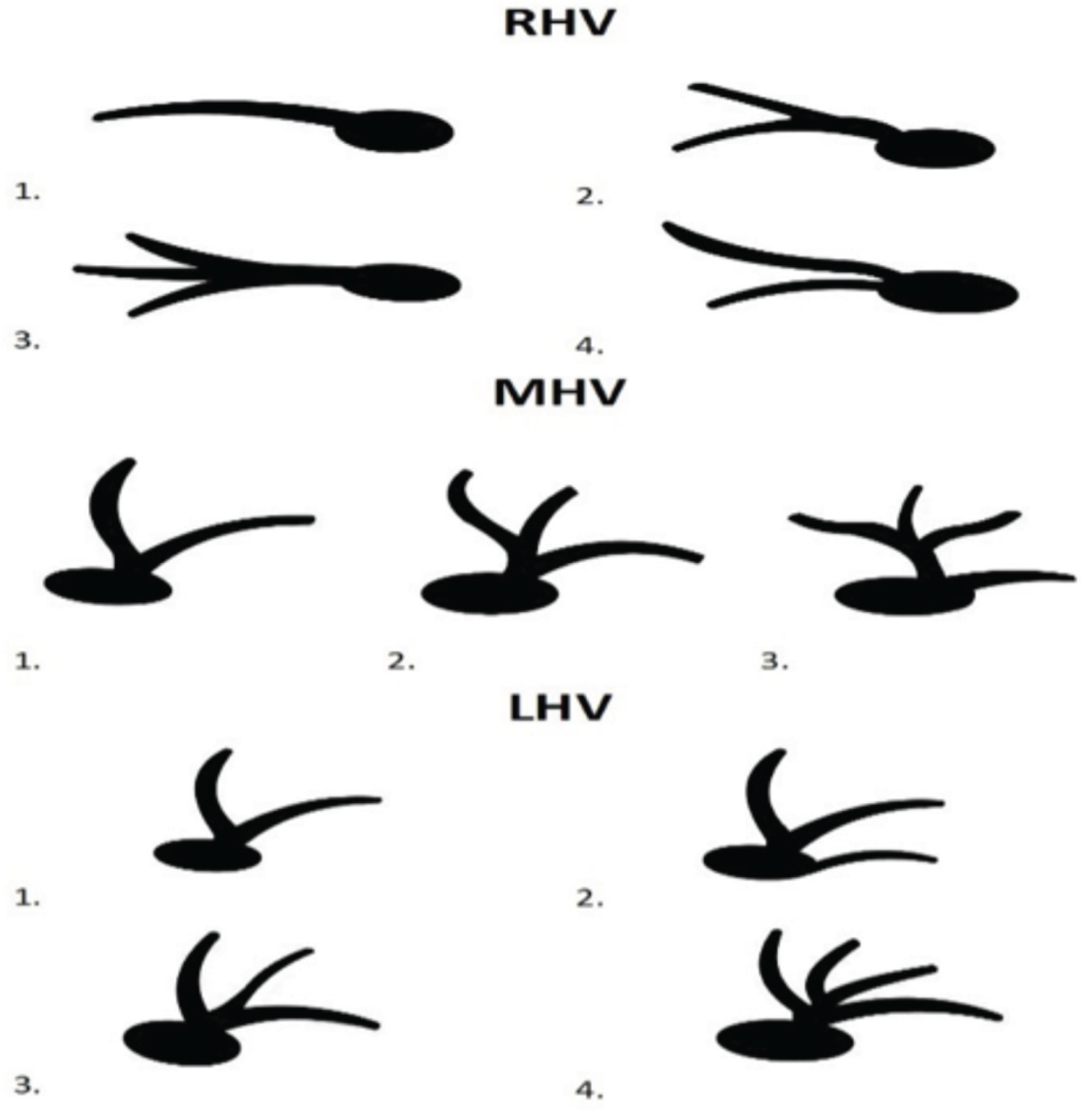

We identified the course of hepatic and portal veins and compared it according to the classification described by Soyer et al. as in

Figure 1 [

10].

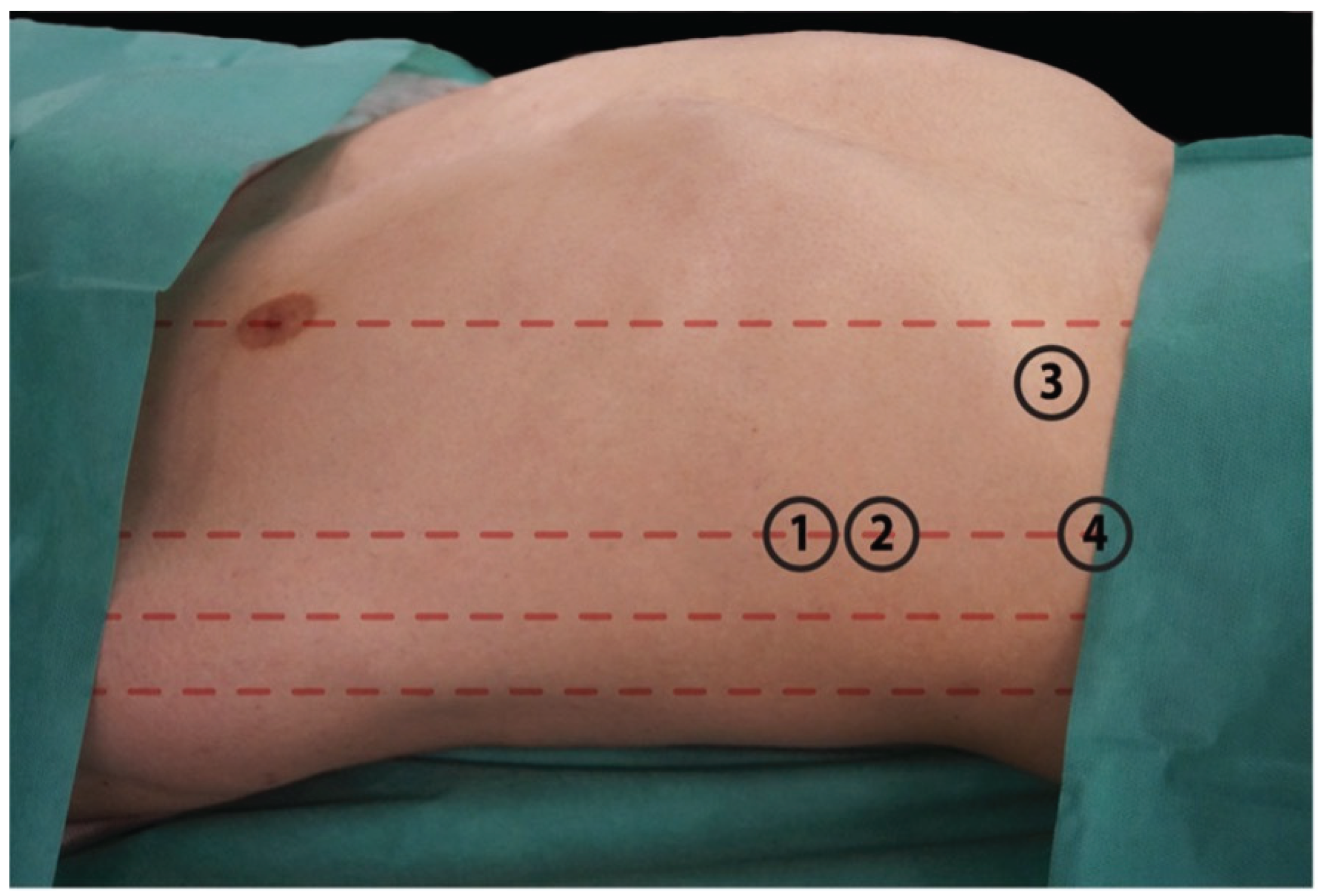

Three types of PV variation were observed. First, which represents normal anatomy, the branch that supplies the right lobe connects with the branch of the left lobe to form the PV. The second type refers to the immediate trifurcation of PV into the left main portal branch, right posterior portal branch, and right anterior portal branch. The third type describes a left main portal branch originating from the RAB. We verified the previously described access points: 1. the 7th intercostal space in anterior axillary line with transducer pointed at 90 degrees towards the skin; 2. the 8th intercostal space in anterior axillary line with transducer pointed at 45 degrees looking superiorly; 3. below costal arch in mid-distance between the xiphoid process and midaxillary line, with transducer directed at the right atrium of heart; 4. below costal arch in anterior axillary line with transducer directed at left shoulder joint [

7,

11,

12]. Those access sites are presented in

Figure 2.

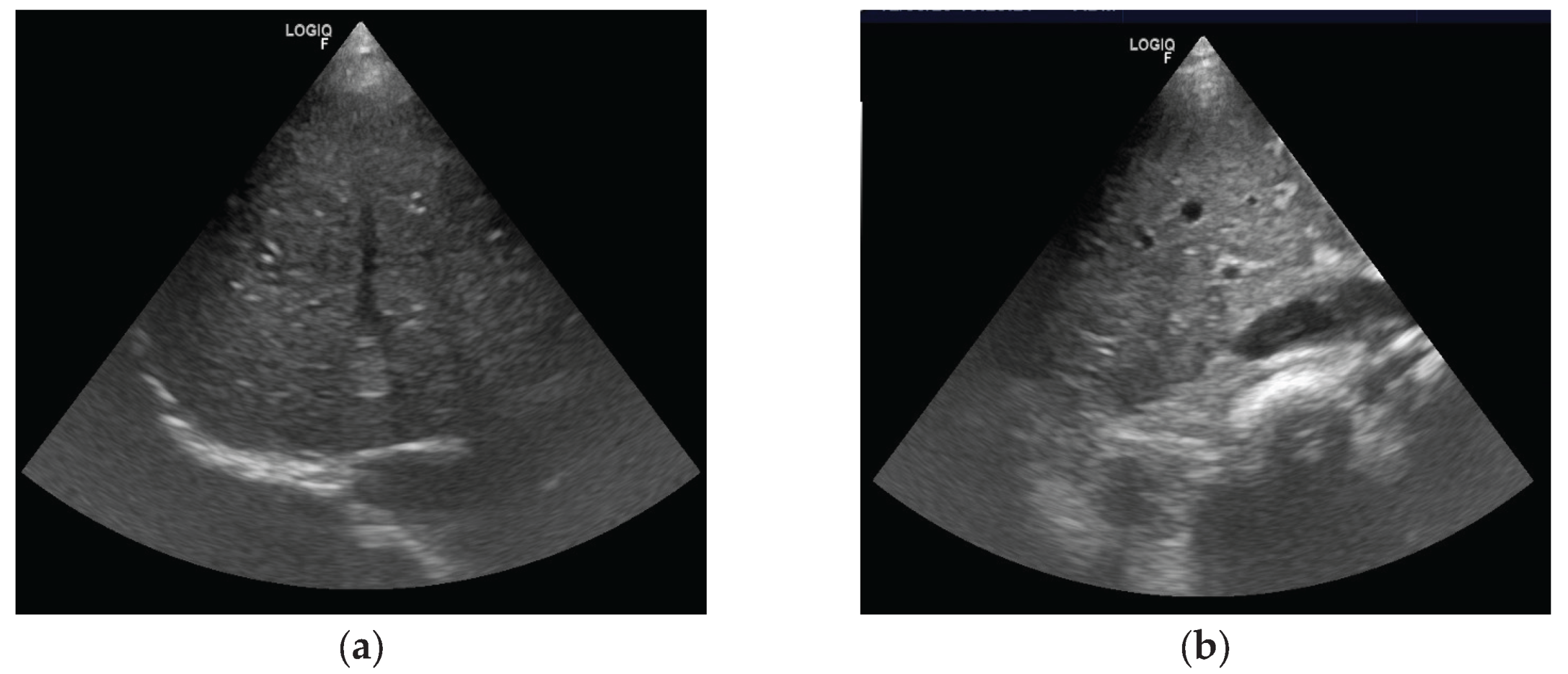

After identifying the vessel along the anticipated needle path during the percutaneous procedure, we assessed its position relative to the transducer. We then classified the approach as either in-plane or out-of-plane. In the in-plane approach, the vessel was aligned with the transducer’s long axis, allowing visualization of its course. In the out-of-plane approach, only a cross-sectional view of the vessel was visible.

Figure 3 illustrate the differences between these approaches. We then measured the distance from the skin surface to the vessel and the vessel’s diameter.

Afterward, we examined alternative access points to the middle hepatic vein (MHV), right hepatic vein (RHV), and RAB. For hepatic veins, we focused on the RHV and MHV, as they provide the most favorable angle for cardiac interventions. When identifying an alternative insertion point, we prioritized vessels aligned with the transducer plane. The transducer was positioned upward for hepatic vein identification and downward for the RAB. We selected vessels with the shortest distance to the transducer, the largest diameter, and no overlapping vessels, bile ducts, or other structures along the transducer axis.

3. Results

3.1. Hepatic Veins and Portal Vein Variations

Our study analyzed 100 participants aged 18 to 43 years (median age, 21 years).

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the study group.

The most common RHV variation observed was a division of the main trunk into two comparably sized branches, which joined the inferior vena cava (IVC) (47/100). In 44 participants, we observed a single RHV with small segmental branches. In 8 subjects, we observed three main branches of similar diameter, which joined together to form a short trunk leading to the IVC. In only one case, we observed the independent outlet of two hepatic veins, both of which drain to the IVC at the same level. Regarding the MHV and the LHV, single hepatic veins that led to the IVC were most frequently observed (in 64/100 and 66/99, respectively). In 36 cases of MHVs and 25 cases of LHVs, there was an increase in the number of major hepatic veins that formed a common trunk to the IVC. Out of these cases, 33 participants had two MHVs, and 21 had two LHVs. Additionally, the presence of 3 hepatic veins was identified in 3 cases involving MHVs and 4 cases involving LHVs. Among the 4 LHVs assessed, we observed an independent outlet of two veins to the IVC at the same level. Furthermore, we assessed the arrangement of the PV division in the hepatic hilum for all subjects. We observed the classic division of the PV into a right and a left branch in the majority of participants (88/100). In 7 subjects, we observed a division of the PV into three main branches, two of which diverged towards the right and one towards the left hepatic lobe. Additionally, in 5 participants, we observed the division of the main trunk of the PV into two right segmental branches, with the left branch then diverging from the RAB. The variability of hepatic veins and portal veins is summarized in

Table 2.

3.2. Accesses Based on Cardiological Guidelines

The results of the percutaneous hepatic vein access sites described in the literature are presented in

Table 3. The highest number of out-of-plane accesses was achieved with access number 1. In other cases, in-plane accesses were obtained more frequently. Among the selected access points, regardless of the plane in which the vessel was located, we were most successful in visualizing the direction of the MHV. The RHV was most frequently visible in access number 4. At access point 3, we commonly observed the large intestine, which lay along the transducer axis, rendering percutaneous access impossible.

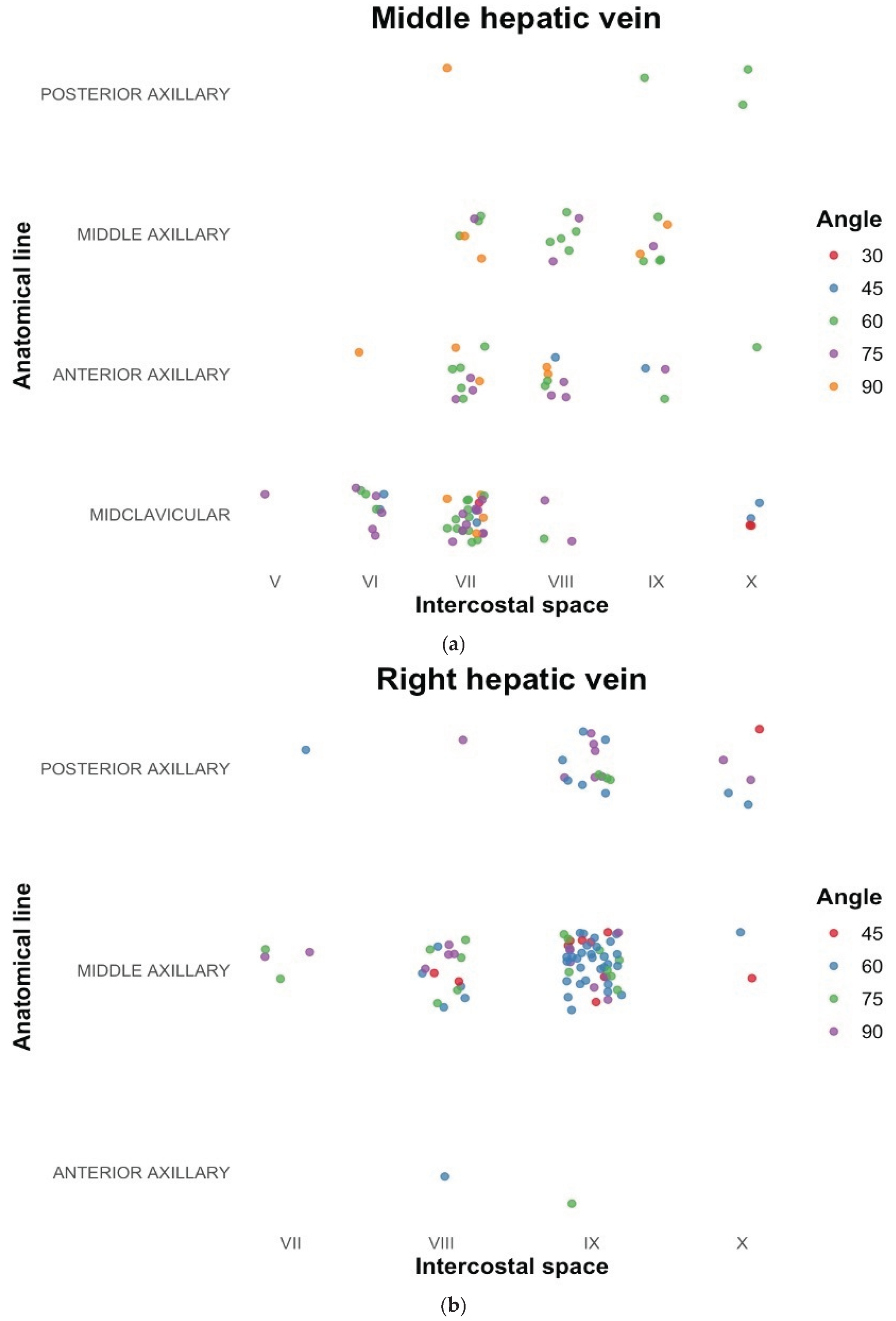

3.3. Evaluation of Transhepatic Accesses

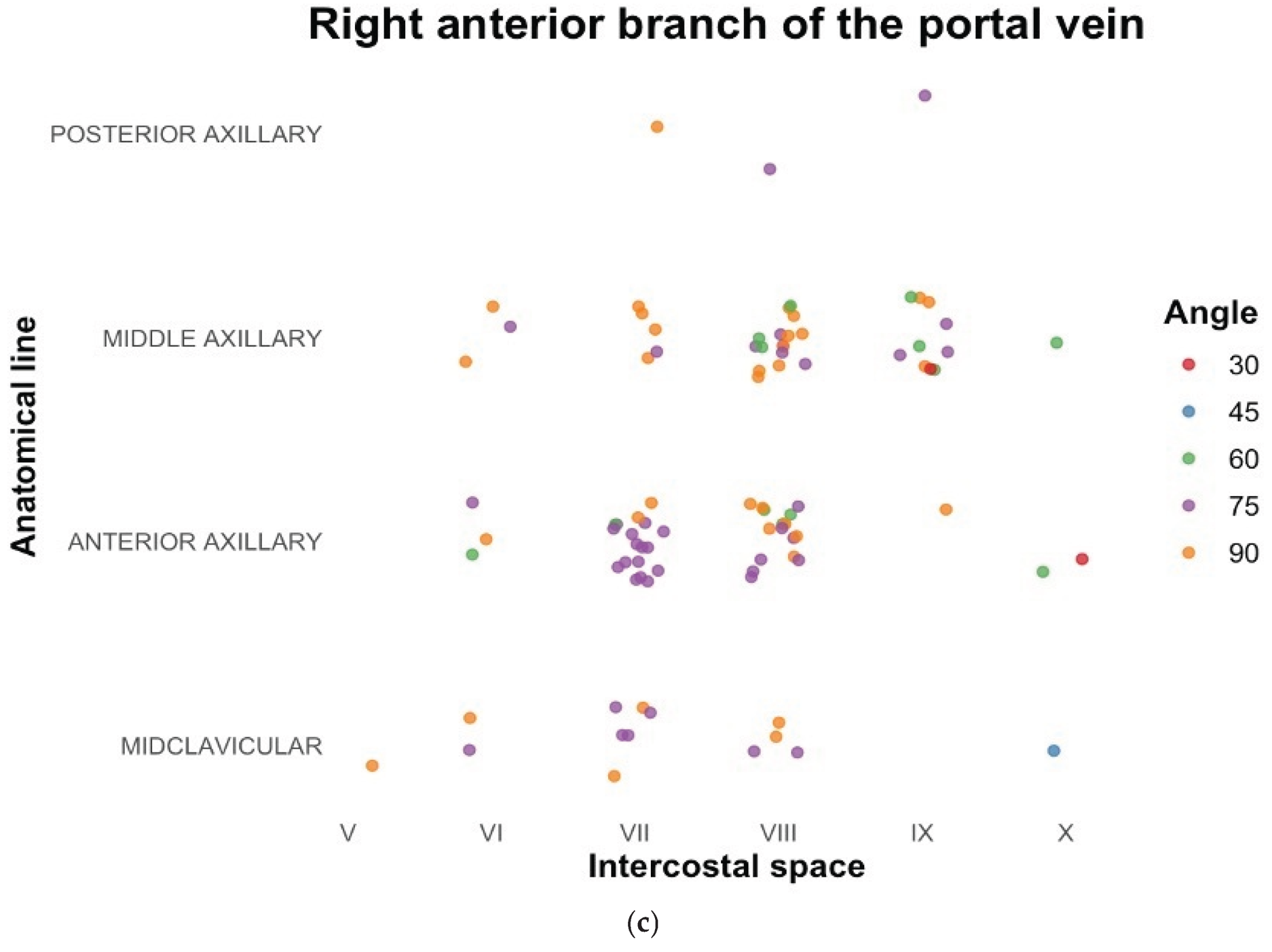

In our search for transhepatic vascular accesses, we found that the success rate of locating suitable access in the cephalic plane was significantly higher than reported in the literature. Certain locations were identified as more reliable for detecting veins in all the vessels examined in our study. For the MHV, the 7th intercostal space at the midclavicular line, with the transducer positioned upward at a 60-degree angle, appeared optimal. For the RHV, the 9th intercostal space at the midaxillary line, with the transducer positioned upward at a 60-degree angle, was identified as the most favorable site. Similarly, for the RAB, the preferred location was the 8th intercostal space in the anterior axillary line, with the transducer positioned downward at a 75-degree angle. The results of the most frequently obtained locations of alternative accesses are shown further on charts in

Figure 4a, 4b and 4c. Measurements of those vessels are presented in

Table 4.

4. Discussion

The variability of the hepatic veins and portal system is critical for liver surgery, including parenchymal resection or transplantation [

13]. For instance, access to the RAB is crucial, as it drains the largest liver segments (V and VIII) and is employed in PV recanalization following stenosis [

9]. Furthermore, it is instrumental in performing intravascular interventions, with the RHV and the MHV being the most suitable for transjugular intrahepatic portal systemic shunt placement [

14]. However, knowledge about variations of these significant vessels is not well established. It is essential to note that different authors describe various hepatic variations, depending on the study design, imaging modality used, and the relevance of each variation to specific interventions. When obtaining intravascular access to the liver for a cardiovascular intervention, the optimal course of the selected vessel for the specific intervention should be considered first and foremost. This information can be easily obtained using ultrasonography, enabling an individualized approach for each patient. In assessing the hepatic vasculature, we have followed the description of hepatic venous variability by Soyer et al. In contrast to that study, we made a distinction between two vessels that collected blood from a given liver segment, even if their diameters were not the same. Soyer et al. excluded vessel types that did not have the same diameter, treating them as one main vessel and the others that drain into it. In intravascular access to the hepatic veins, the diameter of the vessel through which the catheter is inserted is of secondary importance, as all those vessels are usually large enough to fit standard intravascular instrumentation. The angle at which the selected liver vessel is in relation to the target cardiovascular structure and the direction of the vessel in question appear to be much more important. Therefore, access to the MHV is typically utilized for atrial septostomy procedures and RHV access is commonly employed for interventions involving the tricuspid valve. We confidently modified the Soyer et al. classification to achieve a more adequate classification of hepatic vein variations in relation to cardiac interventions. Knowledge of the anatomical variability of the hepatic veins system and the use of US may allow for safe achievement of the chosen intravascular access, optimize the duration of the procedure, and reduce the risk of complications.

Literature provides descriptions of intercostal and subcostal access points. However, many studies lack precise information on needle placement [

15]. In our research, most access points were intercostal, while the subcostal approach also appears to be adequate. The subcostal approach minimizes the risk of injury to the neurovascular bundle and reduces the likelihood of pleural complications. Nevertheless, it may be associated with an increased risk of accidental colon puncture. The intercostal space and line in which puncture should be made is dependent on patients’ anatomical characteristics. The most common access was found for RHV, MHV, and RAB in the 9th, 7th, and 8th intercostal spaces, respectively. Authors usually do not note the angle of puncture in any measurable manner. In our opinion, standardized data on angles could potentially be useful in future procedures. Furthermore, a consensus on vascular patterns and nomenclature should be established to enable more standardized and measurable data comparison.

In our study, the out-of-plane access appeared easier to achieve than the in-plane approach. Therefore, we decided to compare our findings regarding this access with the literature. It was revealed that out-of-plane access was easier to obtain only at the 7th intercostal space and along the anterior axillary line. A recent study reported that the short-axis out-of-plane technique is associated with a higher incidence of posterior wall puncture [

16]. Therefore, heightened procedural awareness and care are essential when performing these interventions. The literature identifies hemorrhage as the most frequent complication associated with percutaneous transhepatic venous access. In the study by Qureshi et al., 124 transhepatic procedures were performed, with major adverse events reported in only 10 cases, comprising 6 instances of bleeding and 4 cases of heart block. Importantly, the study concluded that these diagnostic and interventional procedures did not result in a higher incidence of complications compared to procedures involving central venous line placement alone [

17]. There is a notable lack of studies directly comparing transhepatic in-plane and out-of-plane vascular access techniques. However, several studies investigating vascular access in other anatomical regions, such as the jugular vein, subclavian vein, and femoral vein, have reported no significant differences in efficacy or complication rates between in-plane and out-of-plane approaches [

18,

19]. When selecting the optimal needle insertion site, priority should be given to the orientation and angle of the target vessel, ensuring alignment for a precise approach. Additionally, it is essential to verify that no other vessels and/or bile ducts lie within the projected path of the needle. Based on these considerations, we propose that transhepatic in-plane access represents the preferred option.

Ultrasonographic examination enabled a personalized approach, and in most cases, the target vessel was successfully identified. The results of our study regarding access points for the transhepatic approach seem to be generally consistent with the literature. The transhepatic intravascular access to MHV in the 7th intercostal space, at the midclavicular line, with the transducer positioned upward at 60 degrees, and the RHV in the 9th intercostal space in the posterior axillary line with the transducer positioned upward at 60 degrees angle appear to be new potential solutions for cardiac intravascular interventions. These results may assist in identifying the appropriate vessel during intravascular procedures. However, in our opinion, individualized ultrasonographic evaluation is superior and provides the highest number of suitable transhepatic access points for transhepatic procedures.

The present study is subject to a few limitations. In this study, we followed the classification proposed by Soyer et al., which may not be the most precise. Furthermore, due to discrepancies in the vascular patterns previously described, it is challenging to compare our findings with those of other studies. Our study group is characterized by a limited range of age and BMI, which precludes us from providing a comprehensive representation of the variations that may be encountered in patients. The study does not include a detailed comparison with traditional vascular access methods, such as femoral or jugular vein approaches, as it was not the aim of this study.

5. Conclusions

Ultrasonographic evaluation enables a personalized identification of transhepatic access points, offering a greater number of suitable options compared with previously described anatomical landmarks. When selecting intravascular access for each individual, the vessel’s course and the needle-insertion angle are critical factors that should always be considered in relation to the localization of the intervention. By providing direct visualization of relevant anatomical structures, ultrasonography facilitates individualized procedural planning and may minimize the risk of complications during percutaneous transhepatic intravascular interventions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.R., M.P. and Ar.K.; methodology, J.R. and Ar.K.; investigation, J.R. and M.P; writing—original draft preparation, J.R.; writing—review and editing, M.P. and Ar.K.; visualization, J.R. and M.P.; supervision, Ad.K.; funding acquisition, not applicable. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Warsaw Medical University (approval code: 095, approval date: 12 June 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IVC |

Inferior vena cava |

| LHV |

Left hepatic vein |

| MHV |

Middle hepatic vein |

| PV |

Portal vein |

| RAB |

Right anterior branch of the portal vein |

| RHV |

Right hepatic vein |

| US |

Ultrasonography |

References

- Nicolaou, S.; Talsky, A.; Khashoggi, K.; Venu, V. Ultrasound-guided interventional radiology in critical care. Crit Care Med 2007, 35, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sommer, R.J.; Golinko, R.J.; Mitty, H.A. Initial experience with percutaneous transhepatic cardiac catheterization in infants and children. Am J Cardiol 1995, 75, 1289–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, M.J.; Hovsepian, D.M.; Balzer, D.T. Transhepatic venous access for diagnostic and interventional cardiovascular procedures. J Vasc Interv Radiol 1996, 7, 579–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kehagias, E.; Galanakis, N.; Tsetis, D. Central venous catheters: Which, when and how. British Journal of Radiology 2023, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhulipudi, B.; Bakhru, S.; Singh, J.R.; Koneti, N.R. Transhepatic device closure of atrial septal defect in children associated with interrupted inferior vena cava. Annals of Pediatric Cardiology 2022, 15, 160–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emmel, M.; Sreeram, N.; Pillekamp, F.; Boehm, W.; Brockmeier, K. Transhepatic approach for catheter interventions in infants and children with congenital heart disease. Clin Res Cardiol 2006, 95, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ebeid, M.R. Transhepatic vascular access for diagnostic and interventional procedures: techniques, outcome, and complications. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2007, 69, 594–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.S.; Kim, J.M.; Lee, J.S.; Choi, G.S.; Cho, J.W.; Lee, S.K. Stent insertion and balloon angioplasty for portal vein stenosis after liver transplantation: long-term follow-up results. Diagn Interv Radiol 2019, 25, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ju, C.; Li, X.; Gadani, S.; Kapoor, B.; Partovi, S. Portal Vein Thrombosis: Diagnosis and Endovascular Management. Rofo 2022, 194, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soyer, P.; Bluemke, D.A.; Choti, M.A.; Fishman, E.K. Variations in the intrahepatic portions of the hepatic and portal veins: findings on helical CT scans during arterial portography. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1995, 164, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLeod, K.A.; Houston, A.B.; Richens, T.; Wilson, N. Transhepatic approach for cardiac catheterisation in children: initial experience. Heart 1999, 82, 694–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarrabolu, T.; Balan, P.; Balaguru, D. Percuteneous vascular access for cardiac catherization. In Cardiac catheterization and imaging (From Pediatrics to Geriatrics), Vijayalakshmi, I.B., Ed.; Jaypee Publication: New Delhi, 2015; pp. 59–75. [Google Scholar]

- Sureka, B.; Sharma, N.; Khera, P.S.; Garg, P.K.; Yadav, T. Hepatic vein variations in 500 patients: surgical and radiological significance. Br J Radiol 2019, 92, 20190487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cam, I.; Gencturk, M.; Shrestha, P.; Golzarian, J.; Flanagan, S.; Lim, N.; Young, S. Ultrasound-Guided Portal Vein Access and Percutaneous Wire Placement in the Portal Vein Are Associated With Shorter Procedure Times and Lower Radiation Doses During TIPS Placement. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2021, 216, 1291–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, T.A.; Donnelly, L.F.; Frush, D.P.; O’Laughlin, M.P. Transhepatic catheterization using ultrasound-guided access. Pediatr Cardiol 2003, 24, 393–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, L.; Tan, Y.T.; Wei, T.; Li, H. Comparison between the long-axis in-plane and short-axis out-of-plane approaches for ultrasound-guided arterial cannulation: a meta-analysis and systematic review. BMC Anesthesiol 2023, 23, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, A.M.; Prieto, L.R.; Bradley-Skelton, S.; Latson, L.A. Complications related to transhepatic venous access in the catheterization laboratory--a single center 12-year experience of 124 procedures. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2014, 84, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Mao, Z.; Kang, H.; Hu, X.; Jiang, S.; Hu, P.; Hu, J.; Zhou, F. Comparison between the long-axis/in-plane and short-axis/out-of-plane approaches for ultrasound-guided vascular catheterization: an updated meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2018, 14, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, A.; Kumar, M.; Kumar, N.; Goyal, K.; Soni, K.D.; Yadav, A. Short-axis versus long-axis approach for ultrasound-guided vascular access: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Indian J Anaesth 2023, 67, S208–s217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).