1. Introduction

In recent years, the use of polymer-based composites for bone tissue regeneration purposes has gained momentum as an alternative to metal-based composites due to their excellent physicochemical and mechanical characteristics and their biocompatibility with the biological system in humans (Nurlidar et al., 2018; Senra & Vieira Marques, 2020; Teo et al., 2016). Ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene (UHMWPE), a semi-crystalline polymer with a molecular weight of over 3.1 million dalton, has been proven to be utilized as bone composite materials for bone regeneration and orthopedic applications due to its unique structural and mechanical properties similar to natural bone, high wear and impact resistance, and biocompatibility (Bracco & Oral, 2011; Kang et al., 2016; Maksimkin et al., 2013; Senra et al., 2020). However, the surface of pristine UHMWPE lacks polar groups, resulting in high biological and chemical inertness, which makes it difficult to bond with bone tissue (Han et al., 2023; Van Vrekhem et al., 2018).

To address the limitations of bioinert UHMWPE, several attempts have been made to improve the bioactivity of the UHMWPE-based composite, allowing it to directly bond to the bone and become an ideal material for bone replacement (Fang et al., 2005; Macuvele et al., 2017). Hydroxyapatite (HA; Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2) is an inorganic material whose structure and chemical composition resembles natural bone. Because of its excellent bioactivity and biocompatibility, HA has been commonly used as an implant material in bone tissue regeneration (Grøndahl et al., 2014; Haider et al., 2017). Previous reports showed that reinforced UHMWPE with HA enhanced the bioactivity properties of the composites (Macuvele et al., 2017; Senra et al., 2020). In addition, HA has been commonly used as a coating material to improve the integration of implant materials with bone (Lane et al., 2011; Paital & Dahotre, 2009). However, UHMWPE and HA have no physical or chemical bonding because of their poor compatibility (Macuvele et al., 2019; Senra et al., 2020). The use of surface-modified UHMWPE that contains hydrophilic groups, such as carboxyl, carbonyl, and hydroxyl groups, may improve the interfacial binding performance between the UHMWPE and HA (Chhetri & Bougherara, 2021; Haider et al., 2017; Han et al., 2023).

Chitosan is one of the most naturally abundant and renewable polymers and is highly important in bone tissue regeneration in terms of physicochemical and biological properties including biocompatibility, osteoinductivity, low toxicity, and antibacterial and anti-inflammatory activities (Fasolino et al., 2019; Islam et al., 2020; Rahayu et al., 2022). The presence of functional groups in the chitosan backbone allows it to be impregnated with numerous materials, such as HA, to generate a composite material with bioactive and osteoinductive ability that can be used in bone regeneration (Fu et al., 2017; Koski et al., 2020).

In the present study, we fabricated a porous composite from surface-modified UHMWPE, HA, and chitosan. A composite with a porous structure shows promise as a three-dimensional porous scaffold for bone defect replacement because it can facilitate cell adhesion and bone tissue ingrowth, improving the mechanical fixation of the implant at the implantation sites (Idumah, 2021; Olalde et al., 2020; Pal & Pal, 2006). Sodium chloride (NaCl) is commonly used as a porous agent because of its good intrinsic physical properties, such as solubility, high melting points, non-toxicity, and affordability (Zhao et al., 2018).

Polymer-based composites ideally must meet sterility standards to certify the patient’s safety without compromising their claimed properties (Darwis et al., 2015; Silindir & Özer, 2012). Sterilization using high-energy ionizations, such as gamma rays and electron beams, is an environmentally friendly technique since no harmful chemicals are used and can be applied to the final packaging (Casimiro et al., 2019; Darwis et al., 2015). However, this technique can lead to deterioration of the mechanical properties of medical devices. Previous reports have shown that using gamma irradiation to sterilize UHMWPE composites generates free radicals within the composites, leading to the degradation of the mechanical properties and performance of the UHMWPE-based materials, thus affecting their clinical use (Herczeg & Song, 2022; Tipnis & Burgess, 2018).

In this study, we fabricated porous composites of surface-modified UHMWPE, HA, and chitosan. We hypothesized that using surface-modified UHMWPE can improve interfacial bonding performance between the UHMWPE, HA, and chitosan in the composite; therefore, this composite would be suitable for bone regeneration. Furthermore, we investigated the effect of gamma-irradiation and different chitosan concentrations in the composites on the physicochemical and mechanical characteristics of the composites.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

UHMWPE (surface-modified, powder, average particle size 125 µm), chitosan (low molecular weight, deacetylation degree ≥ 75%), and HA (powder) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). Sodium chloride was obtained from Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany). All reagents were analytical grade and used without any additional processing.

2.2. Fabrication of Porous Composite Containing UHMWPE, Chitosan, and HA

The UHMWPE powder was coated with chitosan by dispersing the UHMPWE powder in the chitosan solution. The mixture of UHMWPE and chitosan (UHMWPE_CHI) was stirred for 4 hours at room temperature and then dried at 50 °C for 24−48 hours.

The UHMWPE_CHI was then coated with HA by dispersing the UHMWPE_CHI powder in 5 mL of HA suspension in 0.02 M sodium hydroxide. The mixture of UHMWPE, chitosan, and HA (UHMWPE_CHI_HA) was stirred for 4 hours at room temperature and then dried at 50 °C for 24−48 hours. The dried UHMWPE_HA_CHI was then sieved, which gives a particle size of ≤300 µm. The final concentrations of UHMWPE, chitosan, and HA in the composites are presented in

Table 1.

The dried UHMWPE_HA_CHI composite was then mixed with NaCl (particle size ≤ 300 µm) at a ratio of 1:1 (g/g) and then molded using a hot press apparatus (Toyoseiki, Tokyo, Japan) at upper and lower plate temperatures of 150 °C and a pressure of 3.5 MPa for 10 min. The composite has a diameter of about 8 mm and a thickness of about 5 mm. After hot pressing, the obtained composite was cooled at RT, washed ten times under stirring with demineralized water to remove the NaCl, and dried at 50 °C.

The porous UHMWPE_HA_CHI composites were then vacuum-sealed and irradiated at a gamma cell facility (cobalt-60; Gamma Cell 220 Upgraded, Izotop, Hungary) at irradiation doses of 25 and 50 kGy. The dose rate was measured to be 3.1 kGy/h using a Fricke solution dosimeter (ASTM 51026, 2015).

2.3. Characterization of Porous UHMWPE Composites

The morphology of the UHMWPE composites was observed under low vacuum conditions using a scanning electron microscope (SEM; Quanta 650; Thermo Fischer, Massachusetts, USA) equipped with energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX; Oxford Instruments, UK) at an acceleration voltage of 12 kV without any coating.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was carried out in PANalytical EMPYREAN diffractometer (Almelo, Netherlands) using Cu-Kα (λ = 0.154 nm) radiation, operated at 40 kV and 30 mA. The scanning was performed in the 2θ range of 5−80° at a step of 0.001°/s.

The Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra of the composites were recorded in the range 400–4000 cm–1 using a Prestige-21 FT-IR spectrometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) based on the KBr method with 45 scans and a resolution of 2 cm–1. IRsolution software from Shimadzu was then used to analyze the FTIR spectra of the composites.

The hydrophilicity of the composites was measured using an optical contact angle meter (Face CA-X, Artisan Technology Group, USA) by dropping demineralized water on the surface of the UHMWPE composite. Five-time measurements were performed and averaged to assess the hydrophilicity of the composites.

An unconfined compression test of the cylindrical-shaped composites (5 mm in height and 8 mm in diameter) was conducted on a universal testing machine (Zwick Roell; Z005, Ulm, Germany) with a load cell of 2.5 kN and a test speed of 5 mm/min. A minimum of five samples of each composite were measured and averaged. The compression test was performed on composite deformations up to 70%. TestXpert III testing software was then used to analyze the results. The compressive modulus of the composites was determined using the slope of a linear region of a stress-strain curve of the composite under compression.

Thermal properties of the UHMWPE composites were assessed using differential scanning calorimetry (DSC; DSC-60; Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). The samples were crimped in an aluminium pan and measured at a temperature of 30–250 °C. DSC analysis was performed under a nitrogen atmosphere (20 mL/min) with a heating rate of 10 °C/min. The results were then analyzed using TA.60 software from Shimadzu.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out using the one-way analysis of variance routine of KaleidaGraph 4.5 (Synergy Software, Reading, PA, USA), followed by Tukey’s honestly significant difference test. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Fabrication and Characterization of The UHMPWE Composites

The surface of pristine UHMWPE lacks polar groups resulting in high chemical inertness and poor interfacial binding adhesion, which make it difficult to bind with hydrophilic materials, such as HA and chitosan (Han et al., 2023; Van Vrekhem et al., 2018). In this study, surface-modified UHMWPE was used to improve the interfacial binding performance between the UHMWPE, HA, and chitosan. The use of surface-modified UHMWPE may improve interfacial bonding between the components in the composite because of the presence of hydrophilic groups, such as carboxyl, carbonyl, and hydroxyl groups, in the surface-modified UHMWPE groups. Possible interactions between the surface modified UHMPE, HA, and chitosan are presented in

Figure 1.

Optical and SEM images were used to investigate the morphology of the composites at different concentrations of chitosan. The results showed that the UHMWPE composites had porous structures as a result of NaCl dissolution, and the pores were distributed irregularly in the UHMWPE composites (Figures 2A−C). The SEM images showed particles were brighter than the surrounding area of the composites because of the higher electron reflection by the higher-atomic number element (calcium atom; Ca), which indicated higher HA deposition in those areas (

Figure 2D−F). The UHMWPE and chitosan have a low electron reflection ratio because they contain only low-atomic-number elements (carbon (C), hydrogen (H), nitrogen (N), and oxygen (O)), resulting in darker areas than Ca-containing areas.

The HA was deposited on the UHMWPE because the hydrophilic groups, such as carboxyl, carbonyl, and hydroxyl groups, present in the surface-modified UHMWPE, have the potential to bind the HA and chitosan. Interestingly, the HA deposition on the surface of the UHMWPE composites containing chitosan is higher than that on the composite without chitosan (

Figure 2D−F). This is because chitosan may serve as a binder for the HA, thus increasing the number of HA depositions on the surface of UHMPWE. Previous reports showed that the amino and hydroxyl groups in chitosan can bind the calcium ions of the HA (Koski et al., 2020; Said et al., 2021). These results indicated an improvement in binding performance between the surface-modified UHMWPE and HA in the presence of chitosan.

EDX mapping was used to study the elemental distribution in the UHMWPE composites. The EDX mapping images showed that the composites comprise C (

Figure 3A−C) and O (

Figure 3D−F) elements from surface-modified UHMWPE and chitosan, and Ca (

Figure 3G−I) and phosphorus (P;

Figure 3J−L)) elements from HA. Importantly, the EDX analysis of the composites revealed the absence of sodium (Na) and chlorine (Cl) elements, which indicates that NaCl as the porous agent dissolved completely during the washing process. The absence of NaCl also indicates interconnections between the pores in the composites. Previous reports confirmed that the interconnected porous structure of the composites is an important property of bone composite materials because it may facilitate cell-matrix interaction, cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation during bone regeneration (Nurlidar et al., 2017; Olalde et al., 2020).

Figure 4 displays XRD patterns of surface-modified UHMWPE and UHMWPE_HA_CHI composites. The most intense peaks observed at 2θ = 21.4° and 23.9° attributed to the (110) and (200) planes of an orthorhombic unit cell of UHMWPE, while less intense peaks located at 2θ = 36.6° and 44° represent the crystallographic planes of UHMWPE (020) and (220), respectively (Feng et al., 2021). The presence of HA in the composites was assigned by the peaks at the 2θ values of 31.7°, 32.9°, and 34.0° correspond to the (211), (300), and (202) planes of HA, respectively (Florkiewicz et al., 2021; Nurlidar et al., 2015).

Figure 4 also revealed that with the presence of HA and chitosan, the diffraction peak slightly shifts toward a larger 2θ value, which is the most prominent for UHMWPE_HA_CHI 0.5. This means that the incorporation of HA and chitosan results in lowered d-spacing of the (110) and (200) planes of the UHMWPE (Q. Wang et al., 2016), indicating that the microstructure of UHMWPE becomes dense by the presence of HA and chitosan. These findings suggest the integration of HA and chitosan in the composites, which are also validated by the SEM-EDX data. These findings indicate the interaction between surface-modified UHMWPE, HA, and chitosan can induce structural modifications that manifest as changes in the XRD peak positions.

3.2. Gamma-irradiation of The UHMPWE Composites

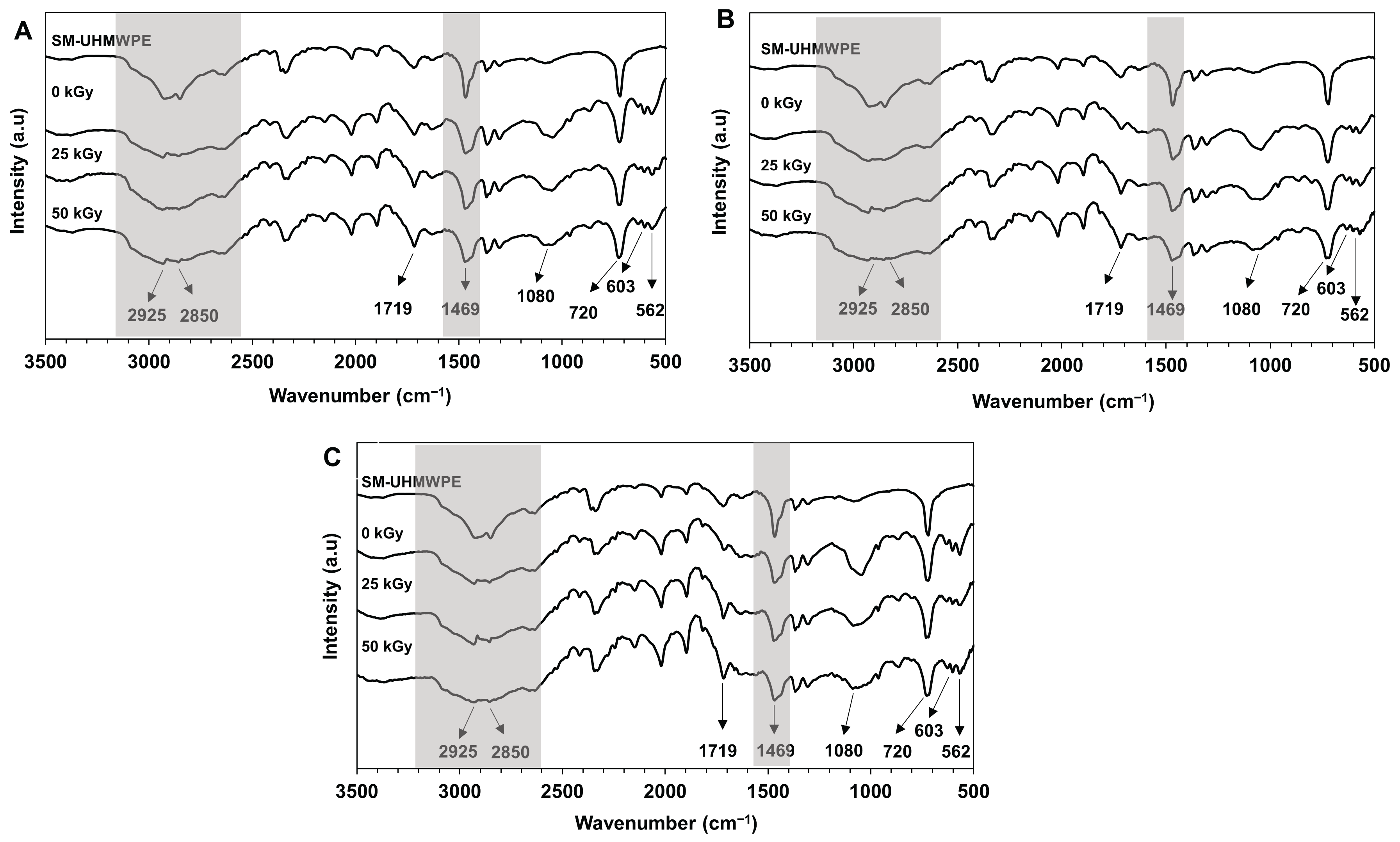

Sterilization of the polymeric composites using gamma rays may change the physicochemical and mechanical characteristics of the composites. In this study, to confirm the changes in functional groups of the UHMWPE composites after gamma irradiation, FTIR analyses were performed.

Figure 5 shows the FTIR spectra of UHMWPE composites before and after gamma-irradiation of 25 and 50 kGy. The spectra showed the characteristic peak of surface-modified UHMWPE at 1719 cm

−1, which was attributed to the oxidized groups in the surface-modified UHMWPE structure (Al-Ghamdi et al., 2022). This peak intensity increased with increasing irradiation doses (

Figure 5). This could be due to gamma-irradiation, which may cause polymer degradation, resulting in the breakage of the polymer linkage and the formation of the oxidized groups in the polymer structure (Al-Ghamdi et al., 2022; Han et al., 2023; Nayak et al., 2021).

Figure 4.

XRD patterns of the surface-modified UHMWPE (A), UHMWPE_HA_CHI 0 (B), UHMWPE_HA_CHI 0.1 (C), and UHMWPE_HA_CHI 0.5 (D).

Figure 4.

XRD patterns of the surface-modified UHMWPE (A), UHMWPE_HA_CHI 0 (B), UHMWPE_HA_CHI 0.1 (C), and UHMWPE_HA_CHI 0.5 (D).

Furthermore, all spectra showed strong peaks at 1469 and 720 cm

−1 due to bending and rocking vibration of the −CH− groups in the UHMWPE structure, respectively (Macuvele et al., 2017; H. Wang et al., 2015). The two peaks at 2925 and 2850 cm

−1 correspond to the C−H stretching modes (asymmetric and symmetric) of the −CH

2− groups of the UHMWPE (Macuvele et al., 2017). The broadening of the absorption peaks in the FTIR spectra of UHMWPE composite (

Figure 5: grey areas) in comparison with the spectrum of surface_modified UHMWPE suggests interactions between HA and chitosan with the oxidized group in the surface-modified UHMWPE structure. It is reported that the C−H vibrational modes in a semi-crystalline polymer microstructure are influenced by nearby polymer chains, resulting in a broad peak absorption (Ennis & Kaiser, 2010).

The presence of HA in the UHMWPE composites is indicated by the appearance of characteristic FTIR peaks of HA at 562, 603, and 1080 cm−1, which are ascribed to PO43- bending vibration (Nurlidar & Kobayashi, 2019). Interestingly, the peak at 1080 cm−1 became broader with increasing irradiation doses. It could be generated by gamma irradiation-induced oxidation in the UHMWPE structure, which leads to an increase in the number of oxidized groups in the UHMWPE structure. Therefore, the interaction between the surface_modified UHMWPE, HA, and chitosan increased.

To further confirm the structural changes in the UHMWPE composites after gamma irradiation, a water contact angle measurement was conducted (

Table 2). The value of the water contact angle may illustrate the hydrophilicity of the composite and it may highly depend on the chemical composition of the composites and the presence of polar functional groups such as carboxyl and hydroxyl groups in the composites. UHMPWE generally is hydrophobic because it contains only C-H and C-C bonds, however, the surface-modified UHMWPE is less hydrophobic because it contains some hydrophilic groups, such as carboxyl, carbonyl, and hydroxyl groups. As can be seen in

Table 2, the UHMWPE composite containing HA and chitosan had a lower water contact angle in comparison to surface-modified UHMWPE (

p <

0.001), indicating the increase in hydrophilicity of the UHMWPE composites in the presence of chitosan and HA. In addition, increasing irradiation doses tends to decrease the water contact angle of the composites, even though the decrease is not significant (

p > 0.05). These indicate the changes in structural changes in the UHMWPE composites as confirmed by FTIR results. Similar observations have been observed in electron beam and gamma-irradiated UHMWPE composites (Grubova et al., 2016; Nayak et al., 2021). Furthermore, Grubova et al. reported that electron beam irradiation induced the formation of the carbonyl group in the UHMWPE composites, decreased the water contact angle, and thus controlled cell proliferation and growth (Grubova et al., 2016).

The mechanical properties of the composites before and after gamma-irradiation were determined using a compression testing method to get compressive modulus and compressive strength data. The compressive modulus describes the relative stiffness or rigidity of the composites; stiff composites will have a high modulus value, requiring greater force to deform the composites (Boughton et al., 2018; Vaidya & Pathak, 2019). The results presented in

Table 3 revealed that the compressive modulus and strength of the UHMWPE composites decreased as the chitosan concentration increased (

p < 0.0001), and the composite with no chitosan (UHMWPE_HA 8_CHI 0) showed the highest compressive modulus and strength. These suggest that the addition of chitosan significantly decreases the stiffness of the UHMWPE composites; composites with high chitosan content (UHMWPE_HA 8_CHI 0.5) were easily broken when subjected to large deformation compared to those with lower chitosan content. This is most likely due to the greater concentration of chitosan causing chitosan agglomeration in the composites. The higher the chitosan concentration, the greater the interfacial binding with the UHMWPE and HA, thus inducing agglomeration. These results are in agreement with the previous publication, which reported that incorporation of collagen into the UHMWPE composite resulted in a decrease in the composite’s mechanical properties (Senra et al., 2020). In addition, the properties of polymer networks depend on their density. UHMWPE composites containing HA and a high concentration of chitosan (UHMWPE_HA_CHI 0.5) have a more dense network as previously described by XRD data, therefore this composite is more rigid and sometimes even brittle compared to UHMWPE with no chitosan. Even though the results showed a significant decrease in the compressive strength of the composites with increasing chitosan concentrations (

p < 0.05), however, the compressive strength values for all the composites are comparable to those reported for cancellous bone (Metzner et al., 2021; M. Wang & Wang, 2019).

Statistical analyses on the effect of gamma irradiation on the mechanical properties of UHMWPE composites showed that there was no significant difference in both compressive modulus and compressive strength of the UHMWPE composites irradiated at either 0, 25, or 50 kGy (p > 0.05). These indicate that irradiation doses up to 50 kGy did not affect the stiffness and strength of the UHMWPE composites. Therefore, the UHMWPE composites in this study could be promising biomaterials for bone tissue regeneration. Importantly, gamma-irradiation up to 50 kGy did not affect the compressive strength of the composites, confirming that gamma-irradiation can be used to sterilize the UHMWPE_HA_CHI composites without affecting their mechanical properties.

Thermal analyses using DSC showed that gamma irradiation tends to increase both melting temperature and degree of crystallinity of the composites compared with unirradiated composites (

Table 4). Similar findings are reported in prior publications, which suggested that ionizing radiation causes an increase in crystallinity and melting temperature (Bhateja, 1982; Deng & Shalaby, 2001). The increase in the degree of crystallinity was explained earlier as resulting from chain scission of the amorphous region, followed by recrystallization of the broken chains (Bhateja, 1982; Deng & Shalaby, 2001). These new recrystallization zones require a higher temperature for melting and thus increase the melting peak temperature of the composite as shown in

Table 4.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, the present study effectively leverages the compatibility of UHMWPE, HA, and chitosan by using surface-modified UHMWPE. A hot press method with NaCl addition as a porogen was successfully used to fabricate porous composites of UHMWPE, HA, and chitosan. The interconnected porous structure and the successful integration of the components in the composites were confirmed through SEM-EDX-mapping images, XRD, FTIR and water contact angle measurements. Furthermore, FTIR analysis indicated modifications in the UHMWPE composites due to oxidation in the UHMWPE and chitosan structures. Even though increasing chitosan concentration in the composites reduced the composite’s stiffness and strength. However, mechanical tests revealed that the composites exhibited good mechanical properties and gamma-irradiation up to 50 kGy has a negligible effect. These results affirm the potential of the composite as a bioactive composite for bone regeneration.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) through Coordinated Research Project F23035 (Contract number 24427).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Al-Ghamdi, H., Farah, K., Almuqrin, A., & Hosni, F. (2022). FTIR study of gamma and electron irradiated high-density polyethylene for high dose measurements. Nuclear Engineering and Technology, 54(1), 255–261. [CrossRef]

- Bhateja, S. K. (1982). Changes in the crystalline content of irradiated linear polyethylenes upon ageing. Polymer, 23(5), 654–655. [CrossRef]

- Boughton, O. R., Ma, S., Zhao, S., Arnold, M., Lewis, A., Hansen, U., Cobb, J. P., Giuliani, F., & Abel, R. L. (2018). Measuring bone stiffness using spherical indentation. PLoS ONE, 13(7), 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Bracco, P., & Oral, E. (2011). Vitamin E-stabilized UHMWPE for total joint implants: A review. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 469(8), 2286–2293. [CrossRef]

- Casimiro, M. H., Ferreira, L. M., Leal, J. P., Pereira, C. C. L., & Monteiro, B. (2019). Ionizing radiation for preparation and functionalization of membranes and their biomedical and environmental applications. Membranes, 9(12). [CrossRef]

- Chhetri, S., & Bougherara, H. (2021). A comprehensive review on surface modification of UHMWPE fiber and interfacial properties. Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing, 140, 106146. [CrossRef]

- Darwis, D., Erizal, Abbas, B., Nurlidar, F., & Putra, D. P. (2015). Radiation Processing of Polymers for Medical and Pharmaceutical Applications. Macromolecular Symposia, 353(1), 15–23. [CrossRef]

- Deng, M., & Shalaby, S. W. (2001). Long-term γ irradiation effects on ultrahigh molecular weight polyethylene. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research, 54(3), 428–435. [CrossRef]

- Ennis, C. P., & Kaiser, R. I. (2010). Mechanistical studies on the electron-induced degradation of polymethylmethacrylate and Kapton. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics, 12(45), 14902–14915. [CrossRef]

- Fang, L., Leng, Y., & Gao, P. (2005). Processing of hydroxyapatite reinforced ultrahigh molecular weight polyethylene for biomedical applications. Biomaterials, 26(17), 3471–3478. [CrossRef]

- Fasolino, I., Raucci, M. G., Soriente, A., Demitri, C., Madaghiele, M., Sannino, A., & Ambrosio, L. (2019). Osteoinductive and anti-inflammatory properties of chitosan-based scaffolds for bone regeneration. Materials Science and Engineering C, 105(April). [CrossRef]

- Feng, M., Li, W., Liu, X., Huang, M., & Yang, J. (2021). Copper-polydopamine composite coating decorating UHMWPE fibers for enhancing the strength and toughness of rigid polyurethane composites. Polymer Testing, 93(September 2020). [CrossRef]

- Florkiewicz, W., Słota, D., Placek, A., Pluta, K., Tyliszczak, B., Douglas, T. E. L., & Sobczak-Kupiec, A. (2021). Synthesis and characterization of polymer-based coatings modified with bioactive ceramic and bovine serum albumin. Journal of Functional Biomaterials, 12(2). [CrossRef]

- Fu, C., Bai, H., Zhu, J., Niu, Z., Wang, Y., Li, J., Yang, X., & Bai, Y. (2017). Enhanced cell proliferation and osteogenic differentiation in electrospun PLGA/ hydroxyapatite nanofibre scaffolds incorporated with graphene oxide. PLoS ONE, 12(11), 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Grøndahl, L., Jack, K. S., & Goonasekera, C. S. (2014). Inorganic polymer composites for bone regeneration and repair. In Bone Substitute Biomaterials. [CrossRef]

- Grubova, I. Y., Surmeneva, M. A., Shugurov, V. V., Koval, N. N., Selezneva, I. I., Lebedev, S. M., & Surmenev, R. A. (2016). Effect of Electron Beam Treatment in Air on Surface Properties of Ultra-High-Molecular-Weight Polyethylene. Journal of Medical and Biological Engineering, 36(3), 440–448. [CrossRef]

- Haider, A., Haider, S., Han, S. S., & Kang, I. K. (2017). Recent advances in the synthesis, functionalization and biomedical applications of hydroxyapatite: a review. RSC Advances, 7(13), 7442–7458. [CrossRef]

- Han, N., Zhao, X., & Thakur, V. K. (2023). Adjusting the interfacial adhesion via surface modification to prepare high-performance fibers. Nano Materials Science, 5(1), 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Herczeg, C. K., & Song, J. (2022). Sterilization of Polymeric Implants: Challenges and Opportunities. ACS Applied Bio Materials, 5(11), 5077–5088. [CrossRef]

- Idumah, C. I. (2021). Progress in polymer nanocomposites for bone regeneration and engineering. Polymers and Polymer Composites, 29(5), 509–527. [CrossRef]

- Islam, M. M., Shahruzzaman, M., Biswas, S., Nurus Sakib, M., & Rashid, T. U. (2020). Chitosan based bioactive materials in tissue engineering applications-A review. Bioactive Materials, 5(1), 164–183. [CrossRef]

- Kang, X., Zhang, W., & Yang, C. (2016). Mechanical properties study of micro- and nano-hydroxyapatite reinforced ultrahigh molecular weight polyethylene composites. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 133(3), 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Koski, C., Vu, A. A., & Bose, S. (2020). Effects of chitosan-loaded hydroxyapatite on osteoblasts and osteosarcoma for chemopreventative applications. Materials Science and Engineering C, 115(April), 111041. [CrossRef]

- Lane, J. M., Mait, J. E., Unnanuntana, A., Hirsch, B. P., Shaffer, A. D., & Shonuga, O. A. (2011). Materials in fracture fixation. In Comprehensive Biomaterials (Vol. 6). Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Lermontov, S. A., Maksimkin, A. V., Sipyagina, N. A., Malkova, A. N., Kolesnikov, E. A., Zadorozhnyy, M. Y., Straumal, E. A., & Dayyoub, T. (2020). Ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene with hybrid porous structure. Polymer, 202(April), 122744. [CrossRef]

- Macuvele, D. L. P., Colla, G., Cesca, K., Ribeiro, L. F. B., da Costa, C. E., Nones, J., Breitenbach, E. R., Porto, L. M., Soares, C., Fiori, M. A., & Riella, H. G. (2019). UHMWPE/HA biocomposite compatibilized by organophilic montmorillonite: An evaluation of the mechanical-tribological properties and its hemocompatibility and performance in simulated blood fluid. Materials Science and Engineering C, 100(February), 411–423. [CrossRef]

- Macuvele, D. L. P., Nones, J., Matsinhe, J. V., Lima, M. M., Soares, C., Fiori, M. A., & Riella, H. G. (2017). Advances in ultra high molecular weight polyethylene/hydroxyapatite composites for biomedical applications: A brief review. Materials Science and Engineering C, 76, 1248–1262. [CrossRef]

- Maksimkin, A. V., Kaloshkin, S. D., Tcherdyntsev, V. V., Chukov, D. I., & Stepashkin, A. A. (2013). Technologies for Manufacturing Ultrahigh Molecular Weight Polyethylene-Based Porous Structures for Bone Implants. Biomedical Engineering, 47(2), 73–77. [CrossRef]

- Metzner, F., Neupetsch, C., Fischer, J. P., Drossel, W. G., Heyde, C. E., & Schleifenbaum, S. (2021). Influence of osteoporosis on the compressive properties of femoral cancellous bone and its dependence on various density parameters. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, C., S., A., Kundu, B., Singh, S., Sivakumar, S., Balla, V. K., & Balani, K. (2021). Radiation-induced effects on micro-scratch of ultra high molecular weight polyethylene biocomposites. Journal of Materials Research and Technology, 11, 2277–2293. [CrossRef]

- Nurlidar, F., Budianto, E., Darwis, D., & Sugiarto. (2015). Hydroxyapatite Deposition on Modified Bacterial Cellulose Matrix. Macromolecular Symposia, 353(1), 128–132. [CrossRef]

- Nurlidar, F., & Kobayashi, M. (2019). Succinylated bacterial cellulose induce carbonated hydroxyapatite deposition in a solution mimicking body fluid. Indonesian Journal of Chemistry, 19(4), 858–864. [CrossRef]

- Nurlidar, F., Kobayashi, M., Terada, K., Ando, T., & Tanihara, M. (2017). Cytocompatible polyion complex gel of poly(Pro-Hyp-Gly) for simultaneous rat bone marrow stromal cell encapsulation. Journal of Biomaterials Science, Polymer Edition, 28(14), 1480–1496. [CrossRef]

- Nurlidar, F., Yamane, K., Kobayashi, M., Terada, K., Ando, T., & Tanihara, M. (2018). Calcium deposition in photocrosslinked poly(Pro-Hyp-Gly) hydrogels encapsulated rat bone marrow stromal cells. Journal of Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine, 12(3), e1360–e1369. [CrossRef]

- Olalde, B., Ayerdi-Izquierdo, A., Fernández, R., García-Urkia, N., Atorrasagasti, G., & Bijelic, G. (2020). Fabrication of ultrahigh-molecular-weight polyethylene porous implant for bone application. Journal of Polymer Engineering, 40(8), 685–692. [CrossRef]

- Paital, S. R., & Dahotre, N. B. (2009). Calcium phosphate coatings for bio-implant applications: Materials, performance factors, and methodologies. Materials Science and Engineering R: Reports, 66(1–3), 1–70. [CrossRef]

- Pal, K., & Pal, S. (2006). Development of porous hydroxyapatite scaffolds. Materials and Manufacturing Processes, 21(3), 325–328. [CrossRef]

- Rahayu, D. P., De Mori, A., Yusuf, R., Draheim, R., Lalatsa, A., & Roldo, M. (2022). Enhancing the antibacterial effect of chitosan to combat orthopaedic implant-associated infections. Carbohydrate Polymers, 289(49), 119385. [CrossRef]

- Said, H. A., Noukrati, H., Youcef, H. Ben, Bayoussef, A., Oudadesse, H., & Barroug, A. (2021). Mechanical behavior of hydroxyapatite-chitosan composite: Effect of processing parameters. Minerals, 11(2), 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Senra, M. R., & Vieira Marques, M. de F. (2020). Synthetic polymeric materials for bone replacement. Journal of Composites Science, 4(4). [CrossRef]

- Senra, M. R., Vieira Marques, M. de F., & de Holanda Saboya Souza, D. (2020). Ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene bioactive composites with carbonated hydroxyapatite. Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials, 110(June). [CrossRef]

- Silindir, M., & Özer, A. Y. (2012). The effect of radiation on a variety of pharmaceuticals and materials containing polymers. PDA Journal of Pharmaceutical Science and Technology, 66(2), 184–199. [CrossRef]

- Teo, A. J. T., Mishra, A., Park, I., Kim, Y. J., Park, W. T., & Yoon, Y. J. (2016). Polymeric Biomaterials for Medical Implants and Devices. ACS Biomaterials Science and Engineering, 2(4), 454–472. [CrossRef]

- Tipnis, N. P., & Burgess, D. J. (2018). Sterilization of implantable polymer-based medical devices: A review. International Journal of Pharmaceutics, 544(2), 455–460. [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, A., & Pathak, K. (2019). Mechanical stability of dental materials. Applications of Nanocomposite Materials in Dentistry, 285–305. [CrossRef]

- Van Vrekhem, S., Vloebergh, K., Asadian, M., Vercruysse, C., Declercq, H., Van Tongel, A., De Wilde, L., De Geyter, N., & Morent, R. (2018). Improving the surface properties of an UHMWPE shoulder implant with an atmospheric pressure plasma jet. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Xu, L., Hu, J., Wang, M., & Wu, G. (2015). Radiation-induced oxidation of ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene (UHMWPE) powder by gamma rays and electron beams: A clear dependence of dose rate. Radiation Physics and Chemistry, 115, 88–96. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M., & Wang, C. (2019). Bulk properties of biomaterials and testing techniques. Encyclopedia of Biomedical Engineering, 1–3, 53–64. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., Wang, H., Fan, N., Wang, Y., & Yan, F. (2016). Combined effect of fibers and PTFE nanoparticles on improving the fretting wear resistance of UHMWPE-matrix composites. Polymers for Advanced Technologies, 27(5), 642–650. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B., Gain, A. K., Ding, W., Zhang, L., Li, X., & Fu, Y. (2018). A review on metallic porous materials: pore formation, mechanical properties, and their applications. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, 95(5–8), 2641–2659. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).