1. Introduction

Breeding waterfowl, ducks in particular, is an important area in the agro-industrial complex, providing not only high-quality meat, but also egg production suitable for the reproduction of cross breeds. Duck eggs are in demand both in the food industry and in incubation production, especially in the context of growing demand for environmentally friendly and biologically complete products. According to experts, the efficiency of incubation of duck eggs is largely determined by the high-quality selection of incubation material, which, in turn, requires an objective and technologically sound individual assessment of eggs based on a combination of morphometric and physical characteristics.

In the traditional practice of selecting hatching duck eggs, especially in small and medium-sized poultry farms, the manual control method prevails: visual inspection, weighing, ovoscopy. This method requires the participation of experienced personnel, takes a significant amount of time and is subject to the subjective factor. At the same time, duck eggs have a number of features that distinguish them from chicken eggs: larger size and increased weight (on average from 70 to 90 grams), stronger shell, as well as a more pronounced variety in geometric shapes. These parameters directly affect the laying of eggs in the incubator, ventilation, temperature conditions and, as a result, the level of hatching of ducklings.

In the modern conditions of digitalization of agriculture and transition to the concept of "smart farm" (Smart Farming), the requirements for standardization, automation and reproducibility of all stages of the production cycle, including sorting and preparation of incubation material, are increasing. The solution of these problems is impossible without the introduction of intelligent systems that combine high-precision measuring equipment, digital image processing algorithms and machine vision technologies.

Optical methods implemented on the basis of high-resolution cameras and software for analyzing the shape, volume and density of objects have proven their effectiveness in the field of quality control of chicken eggs. Therefore, most existing research and industrial solutions are focused on chicken eggs, the standards of which differ from duck eggs both in morphometry and in the boundary values of density and permissible deviations. Thus, the transfer of existing sorting systems to duck eggs without adaptation is impossible and can lead to classification errors, reduced productivity and deterioration of incubation indicators.

Taking into account the above, it becomes obvious that there is a need to develop a specialized automated method adapted to the morphological and physical-mechanical characteristics of duck eggs, capable of real-time non-destructive testing and precise sorting for incubation suitability. Such a method will improve reproductive performance, reduce the impact of the human factor and ensure digital control at the early stages of the production cycle. The solution to this problem corresponds to the priority areas of development of agricultural science, outlined in the framework of the strategy for food security and technological modernization of the agricultural sector.

It should be emphasized that duck eggs differ from chicken eggs not only in geometric proportions but also in surface reflectance and shell microstructure, which affect the accuracy of optical detection. Therefore, a direct transfer of existing image-processing techniques is inadequate. This study introduces specific software and hardware adaptations for duck eggs, including modified contour extraction under variable reflectivity, recalibrated scale coefficients, and a correction factor (Kv) optimized for ovality typical of the Adigel breed.

Despite the obvious importance of high-quality selection of hatching duck eggs to ensure high hatchability and viability of young animals, this aspect remains insufficiently studied in scientific and applied literature. The main emphasis in existing studies is on the sorting of chicken eggs, while duck eggs, despite their physiological differences, are considered secondary in the context of automated assessment of incubation suitability. This leads to a number of methodological and practical contradictions that form the main scientific problem of this study.

Firstly, there is no unified classification and standardized system for assessing the quality of duck eggs adapted specifically for incubation purposes. Existing standards and regulations are mainly focused on food suitability and do not take into account such parameters as shell density, shape and volume-to-weight ratio, which are critical for embryonic development. Therefore, there is a need for scientific development of morphometric and physical indicators that could reliably correlate with the incubation suitability of duck eggs.

Secondly, despite the prevalence of machine vision and digital image processing in other branches of agriculture (for example, in sorting fruits, vegetables, seeds), they are practically not implemented in poultry farming, especially in breeding waterfowl. This is due, in particular, to the lack of specialized algorithms and software capable of correctly analyzing the geometry and density of duck eggs in conditions of natural variability in shape, shell spotting and reflective surface. Consequently, the task arises of adapting existing computer vision methods to the specific properties of duck eggs, including camera calibration, selection of conversion coefficients, processing of shadows and image artifacts.

Thirdly, the problem of integrating various types of sensory information into a single system remains relevant. Today, disparate data obtained from strain gauges, infrared range finders and machine vision cameras are usually analyzed separately. This complicates decision-making in real time and reduces the productivity of the installation. It is necessary to develop a single algorithmic environment in which all egg parameters, including weight, shape, projection area, density, shape index are combined into a complex suitability criterion.

Fourth, there is a lack of experimental data confirming the accuracy and reliability of optical and computer methods for assessing duck egg parameters. Most existing publications either concern chicken eggs or are limited to theoretical modeling without real tests. This makes it difficult to verify such solutions and hinders their practical implementation in poultry farms.

Thus, the combination of scientific and technological problems creates the need for a comprehensive study aimed at the development, software implementation and experimental validation of an intelligent system capable of solving the problem of non-destructive assessment of the incubation suitability of duck eggs with high accuracy and reproducibility.

In most poultry farms, hatching eggs are selected manually, including visual inspection, candling, and weighing. Such procedures are labor-intensive, require skilled personnel, and are highly subjective. Human factor issues lead to significant variability: studies show that the accuracy of manual selection can be as low as 70–85%, which reduces incubation efficiency and increases production losses.

In recent years, machine vision has been actively introduced into chicken egg sorting. A review of technologies highlights the importance of non-destructive optical methods (RGB, NIR and hyperspectral imaging) used to assess the shape, density and contamination of eggs and shell cracks. For example, automated egg sorting lines on conveyors with a real-time camera have been implemented, demonstrating accuracy above 90%.

The use of deep neural networks (e.g. CNN) allowed classification of defective and unsuitable eggs with an accuracy of up to 94%,

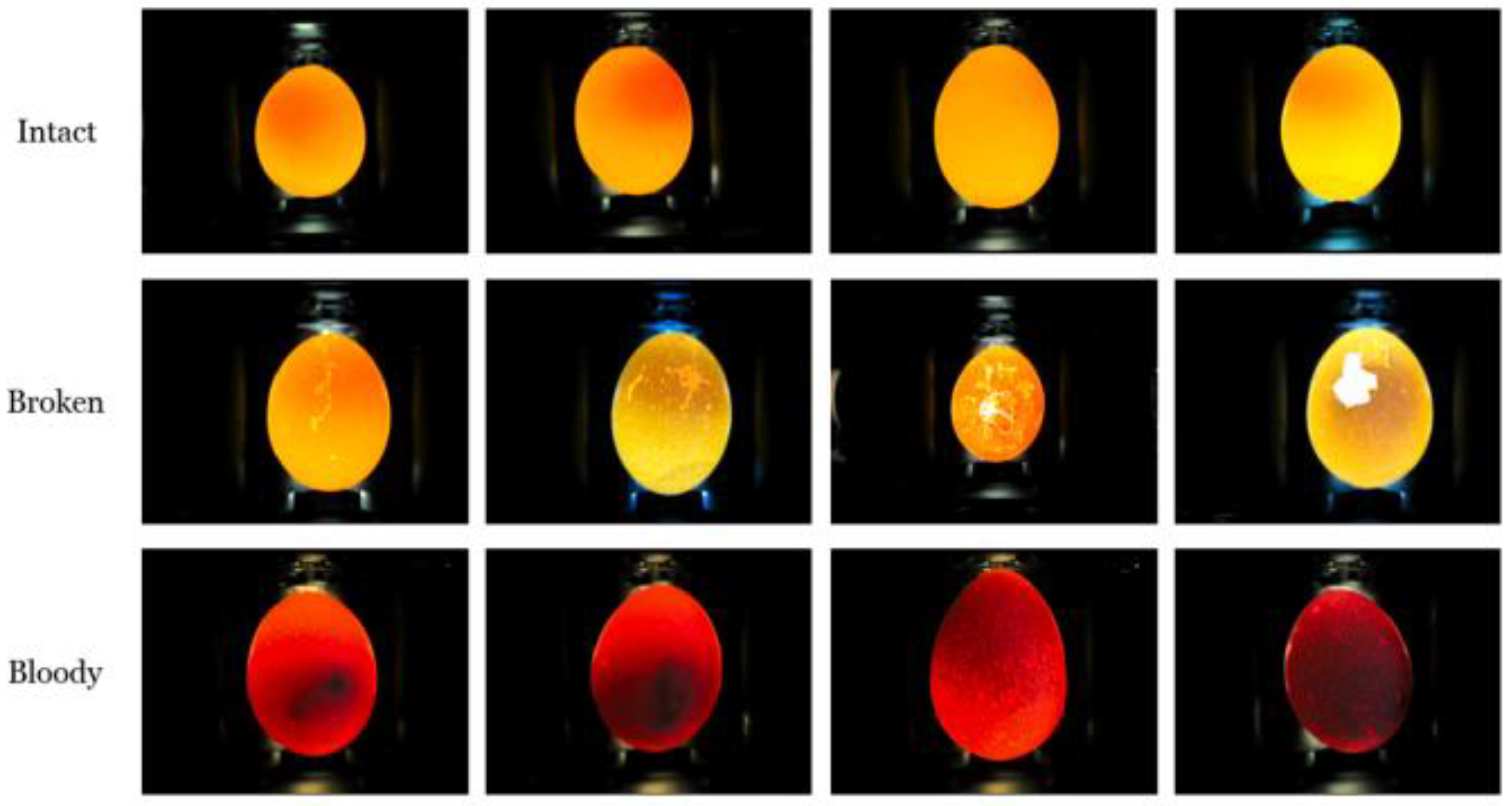

Figure 1 [

1].

Fewer solutions have been developed for duck eggs, but a number of studies show successful adaptation of machine vision.

A method for determining the sex of fertilized duck eggs based on shape analysis uses eccentricity and has been shown to be superior to the manual method,

Figure 2 [

2].

Early ovoscopy (fertility testing) device using cameras and AI (CNN) has achieved accuracy of up to 86%.

The study used a CNN model (ResNet-50) to classify duck eggs with 95% accuracy,

Figure 3 [

3].

Computer vision algorithms for detecting double-yolk duck eggs (

Figure 4), which is important for incubation (CNN and FLD) have been developed and have shown high accuracy [

4].

The aim of this study is the development, algorithmic implementation and experimental verification of an automated optical-electronic method for non-destructive analysis and sorting of hatching duck eggs based on their morphometric and physical parameters.

To achieve the stated goal, the following main research objectives were formulated:

Analysis of the morphological and physical characteristics of duck eggs that affect their incubation suitability (weight, geometric dimensions, density, shape, index and shape coefficient) in order to establish measurable criteria.

Development of a hardware architecture for an experimental setup that includes a strain gauge, a digital video camera, an infrared rangefinder, and an egg movement mechanism that ensures the capture and processing of images in two projections.

Creation of an algorithm for digital image processing that allows determining the large and small diameter of an egg, the area of the longitudinal section, volume, density and shape factors with the subsequent construction of a classification feature for suitability for incubation.

Integration of sensor data (weight, dimensions, image) into a single software control environment, implemented on the basis of a single-board microcomputer with its own software in the Python language.

Conducting experimental studies on a sample of 300 duck eggs of the "Adigel" breed with parallel manual measurement of parameters (weight, egg size) and assessment of the accuracy, reproducibility and error of the automated system.

Comparative analysis of the results of manual and automatic assessment with calculation of statistical indicators (mean values, standard deviations, correlation coefficients, relative errors) to verify the operability of the proposed system.

Formation of conclusions and recommendations on the practical application of the proposed rational method in the incubation process, as well as the prospects for its adaptation to other bird species and expansion of functionality (for example, determining fertility).

Specific Adaptations for Duck Eggs

Unlike chicken eggs, duck eggs exhibit larger geometric dimensions, higher shell reflectivity, and greater morphological variability. Therefore, the developed method includes several technical and algorithmic adaptations to ensure accurate optical analysis:

Calibration routines: The infrared rangefinder VL53L0X was recalibrated for the larger average diameter (≈68 mm) of duck eggs to maintain sub-millimeter measurement precision and accurate pixel-to-metric conversion.

Contour detection: Adaptive thresholding with the Gaussian method (block size = 51×51, constant C = 2) and a 5×5 median filter was applied to minimize false edges on glossy or spotted shells.

Lighting correction: A diffused matte LED lighting system was introduced to eliminate glare and improve contour stability.

Ellipsoid correction factor: The empirical coefficient Kv=0.637 was derived from experimental volume–mass correlations specifically for the Adigel breed, differing from the coefficients used for chicken eggs (0.61–0.64).

Shape coefficient (K₁): Introduced as a dimensionless compactness parameter K1=P2/S, where P is the perimeter (Ramanujan’s approximation for an ellipse) and S is the longitudinal section area. This ratio reflects shell symmetry and correlates with hatchability suitability.

These modifications enable the system to handle breed-specific morphological diversity and optical heterogeneity, ensuring reliable performance for non-destructive analysis of duck eggs.

Thus, this study aims to create a technological and scientific basis for the implementation of machine analysis of duck eggs, capable of replacing subjective manual procedures with highly accurate, reproducible and scalable automated methods that meet the requirements of modern agricultural industry.

2. Materials and Methods

The object of the study were duck eggs of the Adigel breed, selected for the purpose of identifying their suitability for incubation using an optical-electronic system . The incubatory duck eggs were from a poultry farm in the Almaty region specializing in breeding ducks for reproductive purposes. The sample consisted of 300 incubatory duck eggs.

The hatching eggs had the following average values :

weight from 70 to 90 grams;

the shape is predominantly oval with slight asymmetry;

the color of the shell is white or slightly cream;

the surface is smooth, without defects;

The selection was carried out in accordance with the technical conditions for hatching eggs. Eggs with damage, dirty shells and signs of microcracks were rejected before the experiment. Before each sample was launched into the installation, manual identification and number marking were carried out, which is necessary for comparing the results of manual and automated measurements.

The parameters to be assessed are:

weight (g) - as the main physical indicator of egg maturity;

length (major diameter, mm) is an important morphometric parameter;

width (minor diameter, mm) - allows you to calculate the shape index;

longitudinal cross-sectional area (mm²) - reflects the shape and volume;

volume (cm³) - calculated based on geometric characteristics;

density (g/cm³) - used as an indirect indicator of quality;

shape index (%) and shape coefficient (dimensionless value) - determine the suitability of the egg for incubation based on geometry.

Since the hatchability of duck eggs largely depends on the ratio of weight, density and shape, these parameters were chosen as key ones for evaluation.

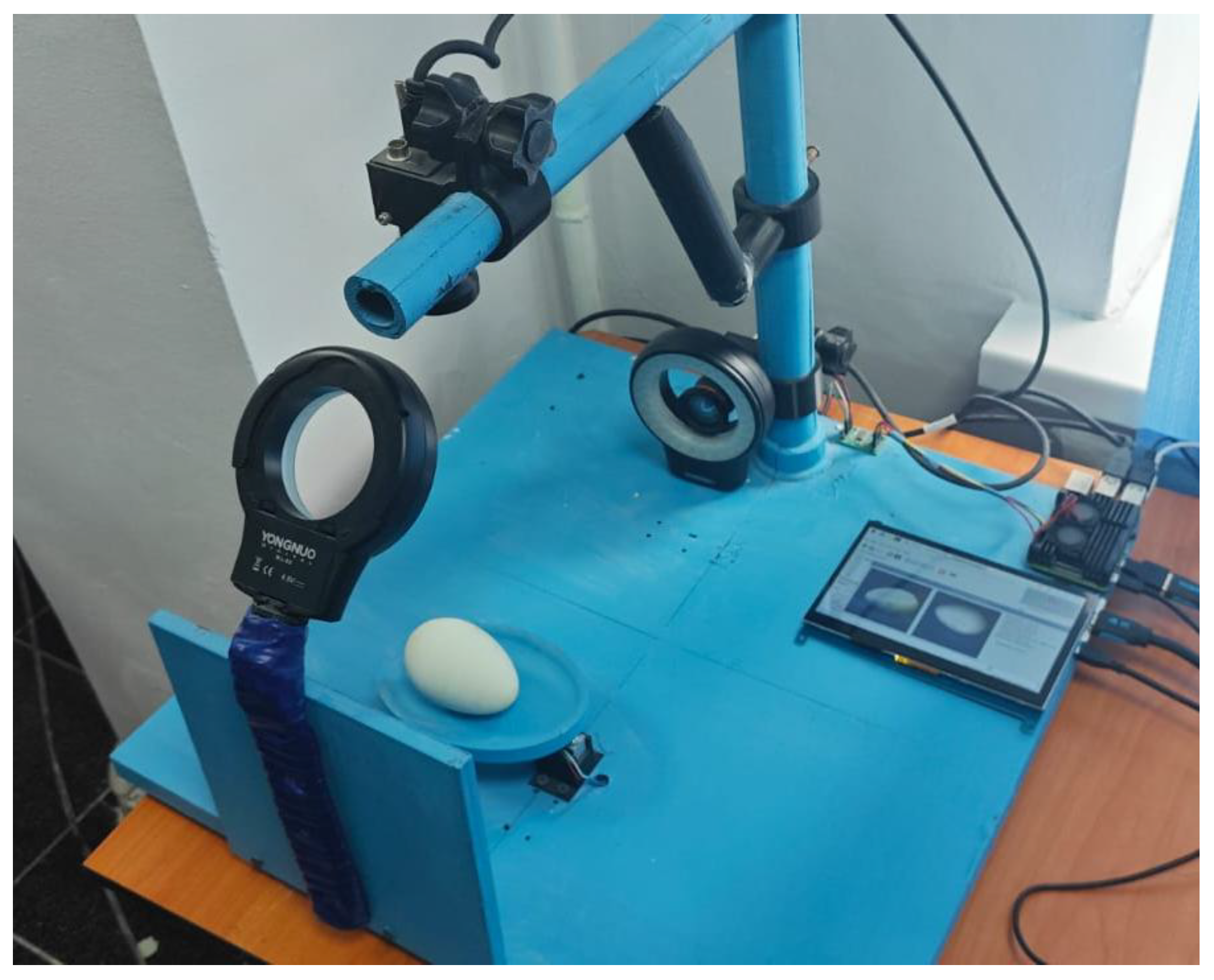

A stationary device based on machine vision and physical measurement sensors was developed for the purposes of non-destructive analysis of hatching duck eggs. The device provides sequential testing of eggs in a single measurement cell, without transport mechanisms or a rotary drum, which simplifies the design and increases the accuracy of measurement by minimizing mechanical errors.

The design of the installation includes the following components:

Single-board microcomputer Raspberry Pi 4 Model B - performs the functions of the central processor, processes images, controls sensors and the operator interface.

Logitech C270 digital camera - captures an image of an egg from above and from the side. The camera is mounted on an adjustable tripod at exactly 90° relative to the surface of the measuring cell.

Strain gauge sensor HX711 with a measuring module - located under the base of the measuring platform on which the egg is placed. Provides mass measurement accuracy with an error of up to ±0.1 g.

Infrared rangefinder VL53L0X - measures the distance from the camera lens to the surface of the egg, which is necessary for calibrating the image scale and converting pixels into physical units of measurement.

The measuring platform (cell) is a hard, flat surface with a non-slip coating, designed for laying one egg. The platform is made of light matte plastic, which does not give glare when shooting.

LED backlight with diffuser - provides uniform illumination without shadows and reflections for stable operation of the contour recognition algorithm.

The principle of operation of the installation is as follows:

The operator manually places the egg on the measuring platform.

The load cell records the mass and transmits the data to the Raspberry Pi.

The camera captures images from above and from the side.

At the same time, the rangefinder measures the distance to the egg surface, which is used for scale calibration.

-

Embedded software in Python (using OpenCV and NumPy libraries):

- ○

highlights the outline of the egg;

- ○

calculates large and small diameter;

- ○

estimates the area of a longitudinal section;

- ○

Based on empirical formulas, it calculates volume, density, index and shape factor.

The received parameters are saved in a database with the possibility of exporting to CSV format.

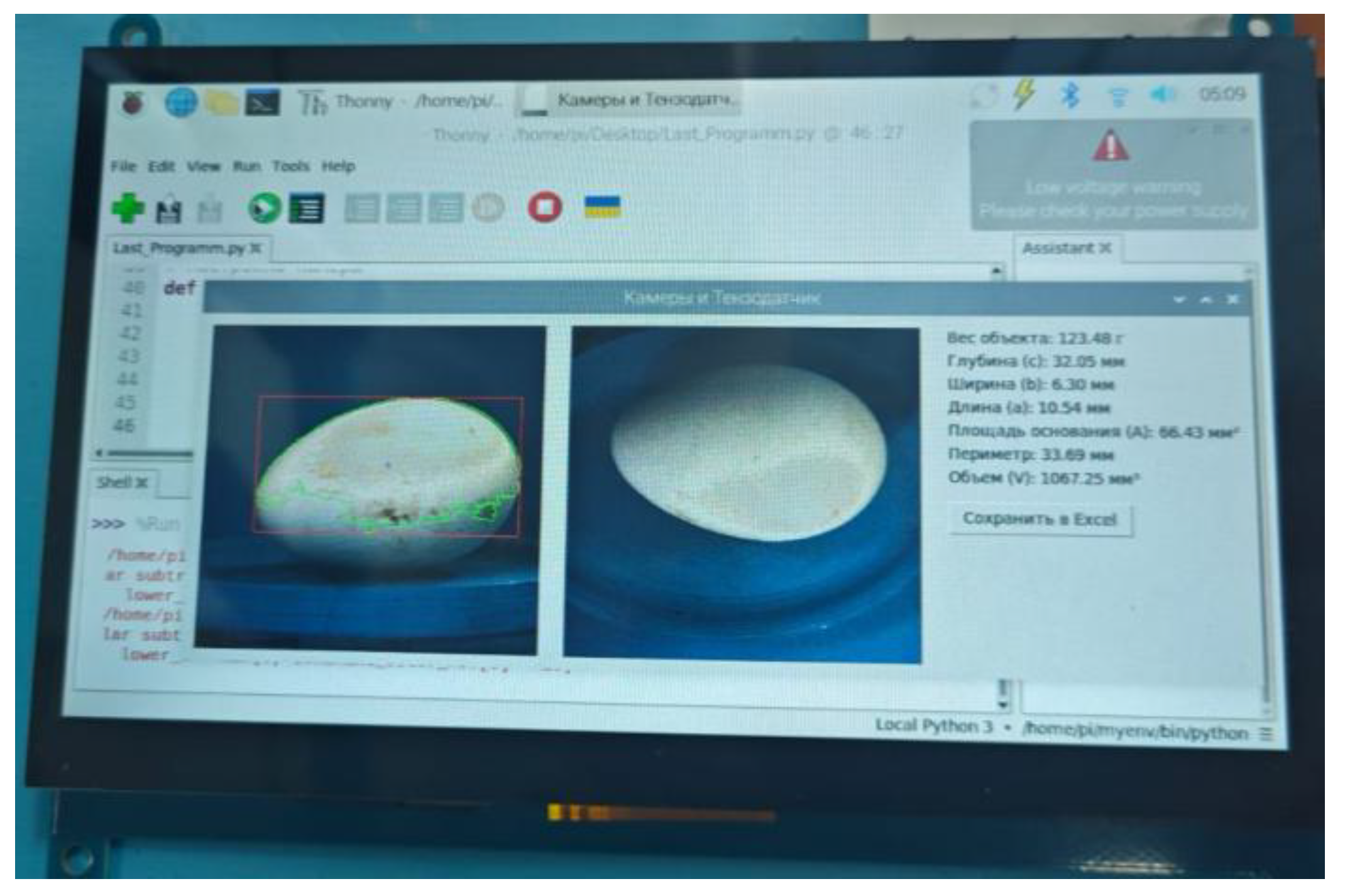

The user receives a visual report with a graph and classification, i.e., the suitability of the egg for incubation is determined by the established boundary values of mass, density and shape. The program interface is shown in

Figure 5, and the image processing process is shown in

Figure 5a.

Advantages of a stationary structure:

High stability of measurements due to the absence of mechanical movements.

The simplified design is inherently ideal for laboratory conditions and pilot studies.

The ability to quickly adapt to different bird breeds and egg types due to the open software architecture.

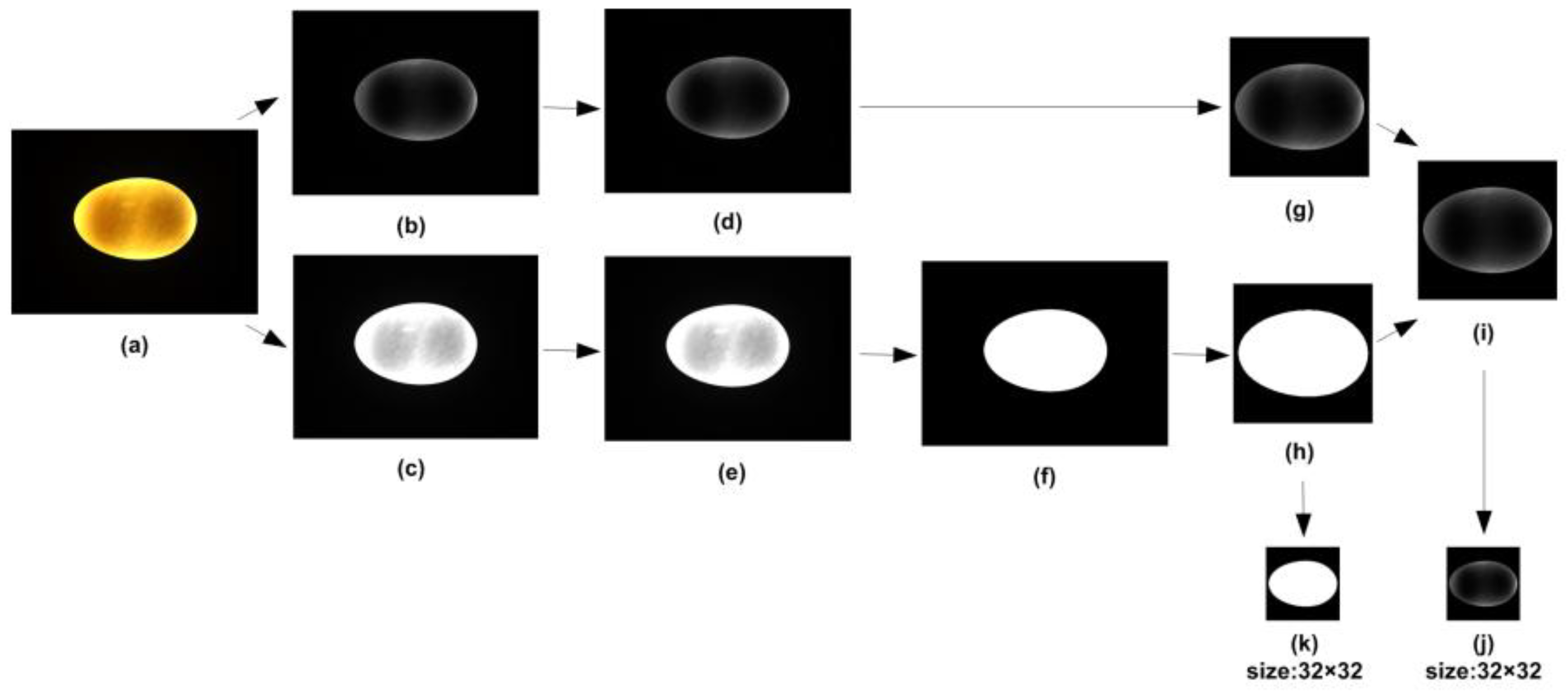

The processing of duck egg images and the calculation of morphometric and physical parameters were carried out using digital image analysis algorithms implemented in the Python environment using the OpenCV, NumPy and Matplotlib libraries. The entire processing procedure was carried out in a semi-automatic mode with verification of the results.

Each egg was photographed in two projections - from above and from the side. The following sequence of operations was performed on the images:

Background correction and illumination equalization: Gaussian blur and histogram normalization methods were used.

Threshold filtering: Adaptive threshold segmentation was used to extract the egg outline.

Contour analysis: the dimensions of the egg and the coordinates of key points were determined based on the selected contour.

Ellipse construction: the contour was approximated to an ellipse, from which the major (D) and minor (d) diameters in pixels were extracted.

To convert pixel coordinates into metric units (mm, cm²), a calibration object of known size (reference marker 20x20 mm) was used, placed on the measuring platform. The scale was calculated using the formula:

where:

The scale factor allowed the measurements D, d and area S to be converted into millimetres and square centimetres.

To estimate the volume of an egg, a modified formula for the volume of an ellipsoid with a correction factor Kv, recommended in the works of A.M. Bashilov and D.M. Alikhanov [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10] was used:

where:

The result was converted into cm³.

After measuring the mass m with a strain gauge and determining the volume, the egg density ρ was calculated using the formula:

where:

According to [

11,

12], the density of duck eggs suitable for incubation is in the range of 1.065–1.115 g/cm³.

The morphological suitability of the egg for incubation was assessed using the shape index (If) and the shape coefficient (K₁):

where:

d and D — small and large diameters of the egg (mm),

P is the perimeter of the longitudinal section (mm), calculated using the Raman formula for an ellipse,

S — longitudinal cross-sectional area (mm²).

For duck eggs, according to literature data [

13,

14], the optimal shape index is 68-74%, and the shape coefficient is within 13.5–14.5. Going beyond these limits may indicate asymmetry, narrowing, anomalies, or double yolks.

To confirm the operability of the developed system, an experiment was conducted on non-destructive measurement of duck egg parameters and subsequent comparison of the results of automatic assessment with manual measurements taken as a conditional "standard".

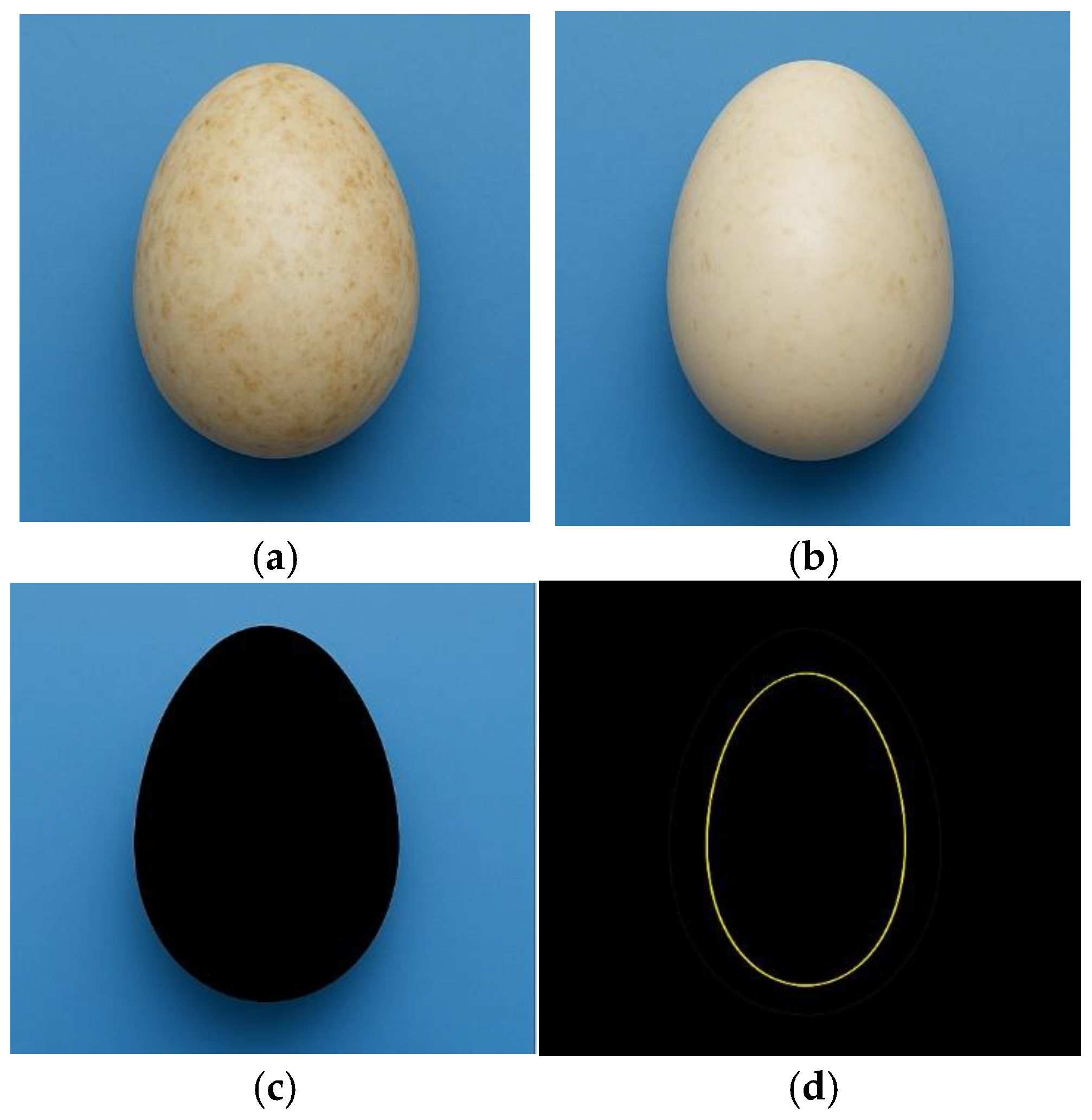

Figure 6 shows the preparation of a sample of eggs.

All measurements were carried out in laboratory conditions at a temperature of +22 ± 1 °C and humidity of 50–55%.

Each sample (300 duck eggs in total) was cleaned of any dirt with a soft, dry cloth before being placed in the egg.

The eggs were visually checked for shell integrity.

The sequence of actions: the egg was manually weighed and measured with a caliper, then placed in the machine and analyzed by the machine vision system. The measurement process is shown in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8.

The following parameters were measured and compared:

mass (g) - using laboratory scales (manual method) and a load cell (automatic system);

large and small diameter (mm) - manually using a caliper and automatically from a camera;

longitudinal cross-sectional area (mm²) - only automatically;

volume (cm³) - only automatically;

density (g/cm³) — calculated by mass and volume;

shape index (%) and shape factor (dimensionless) - only automatically.

For each sample, an individual ID was created (marking on the shell).

The results of manual measurements were recorded in an Excel spreadsheet.

Automatic data was saved in .csv and .json format.

Additionally, for each sample, images (top and side views) were saved and linked to the egg ID.

A comparative analysis of manual and automatic measurements was conducted using the following metrics:

Python tools (pandas, scipy. stats, matplotlib) and Excel were used to process the data.

According to substantiated literary data and internal standards of the poultry farm, an egg is considered suitable for incubation if the following conditions are met:

weight ranging from 70 to 90 g,

density from 1.065 to 1.115 g/cm³,

form index 68–74%,

Absence of geometric deformations (assessed by the shape factor).

The results of the analysis were classified into 3 groups:

Suitable for incubation.

️ Borderline (requires re-checking).

Unsuitable (by weight, density or shape).

3. Results

As a result of the experiment conducted using an intelligent machine vision installation on a sample of 300 duck eggs, the following parameters were obtained and analyzed: weight, geometric dimensions (large and small diameter), projection area, volume, density, shape index and shape coefficient.

Comparison of manual and automatic measurements allowed us to evaluate the accuracy, reproducibility and degree of agreement between the data obtained in the two methods.

Table 1.

Comparative table of average values.

Table 1.

Comparative table of average values.

| Indicator |

Manual method (mean ± standard deviation) |

Automatic system (average ± standard deviation) |

Relative error (%) |

| Weight, g |

78.34 ± 5.21 |

78.18 ± 5.17 |

0.20% |

| Large diameter, mm |

68.41 ± 2.83 |

68.63 ± 2.91 |

0.32% |

| Small diameter, mm |

52.17 ± 2.48 |

51.98 ± 2.53 |

0.36% |

| Cross-sectional area, mm² |

— |

2513.42 ± 145.30 |

— |

| Volume, cm³ |

— |

76.84 ± 5.48 |

— |

| Density, g/cm³ |

— |

1.017 ± 0.033 |

— |

| Form index, % |

— |

75.76 ± 2.41 |

— |

| Form factor (K₁) |

— |

13.92 ± 0.55 |

— |

Table 2.

Correlation coefficients.

Table 2.

Correlation coefficients.

| Parameter |

Correlation coefficient (r) |

| Weight |

0.998 |

| Large diameter |

0.987 |

| Small diameter |

0.982 |

| Volume and mass |

0.954 |

| Density and mass |

-0.472 |

| Density and shape index |

-0.384 |

It should be noted that when outliers with abnormal geometry (extremely elongated or flattened eggs) were excluded, the correlation between mass and density became positive (r = +0.62), consistent with the physical law ρ = m/V.

Values of r>0.95 for the main dimensions indicate high reliability and consistency of the automated system with traditional manual methods.

Based on the developed classification criteria, the following distribution was identified:

Suitable for incubation: 234 eggs (78%).

Borderline parameters: 43 eggs (14.3%)

Unsuitable (due to shape, weight or density): 23 eggs (7.7%).

An example of an egg with a density deviation (0.955 g/cm³) was accompanied by an elongated shape and a small volume. The opposite situation was observed in eggs with a density over 1.13 g/cm³ - often with a thickened shell or a rounded shape.

For visual analysis, the following graphs were constructed:

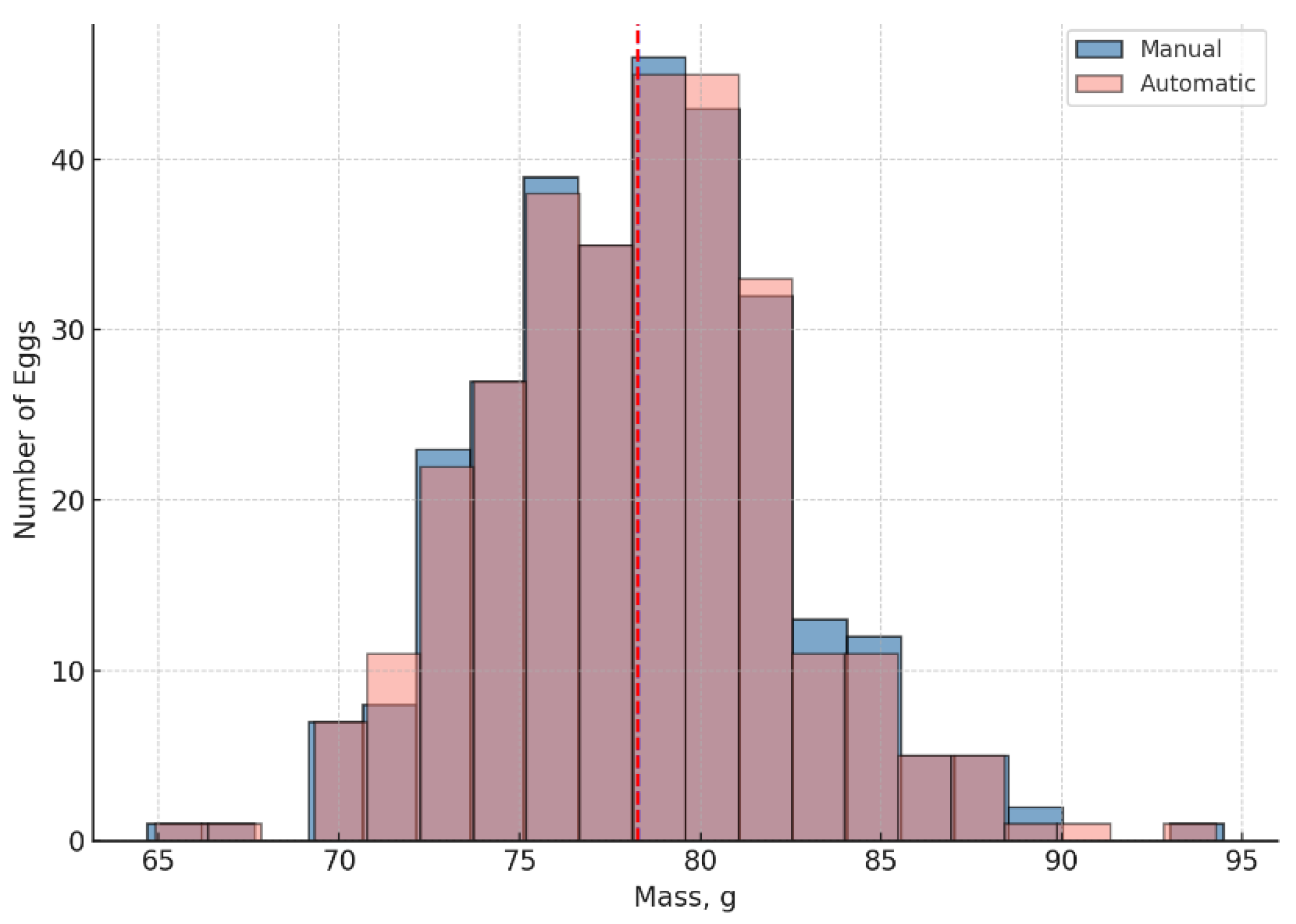

Figure 9 shows a histogram of the distribution of duck egg weights obtained in two ways: manually and using an automated system. As can be seen:

the peaks of the distributions are almost identical;

the average weight differs by less than 0.2 grams;

Both methods exhibit normal distribution with similar variance.

This confirms the high accuracy and reproducibility of automated mass measurement.

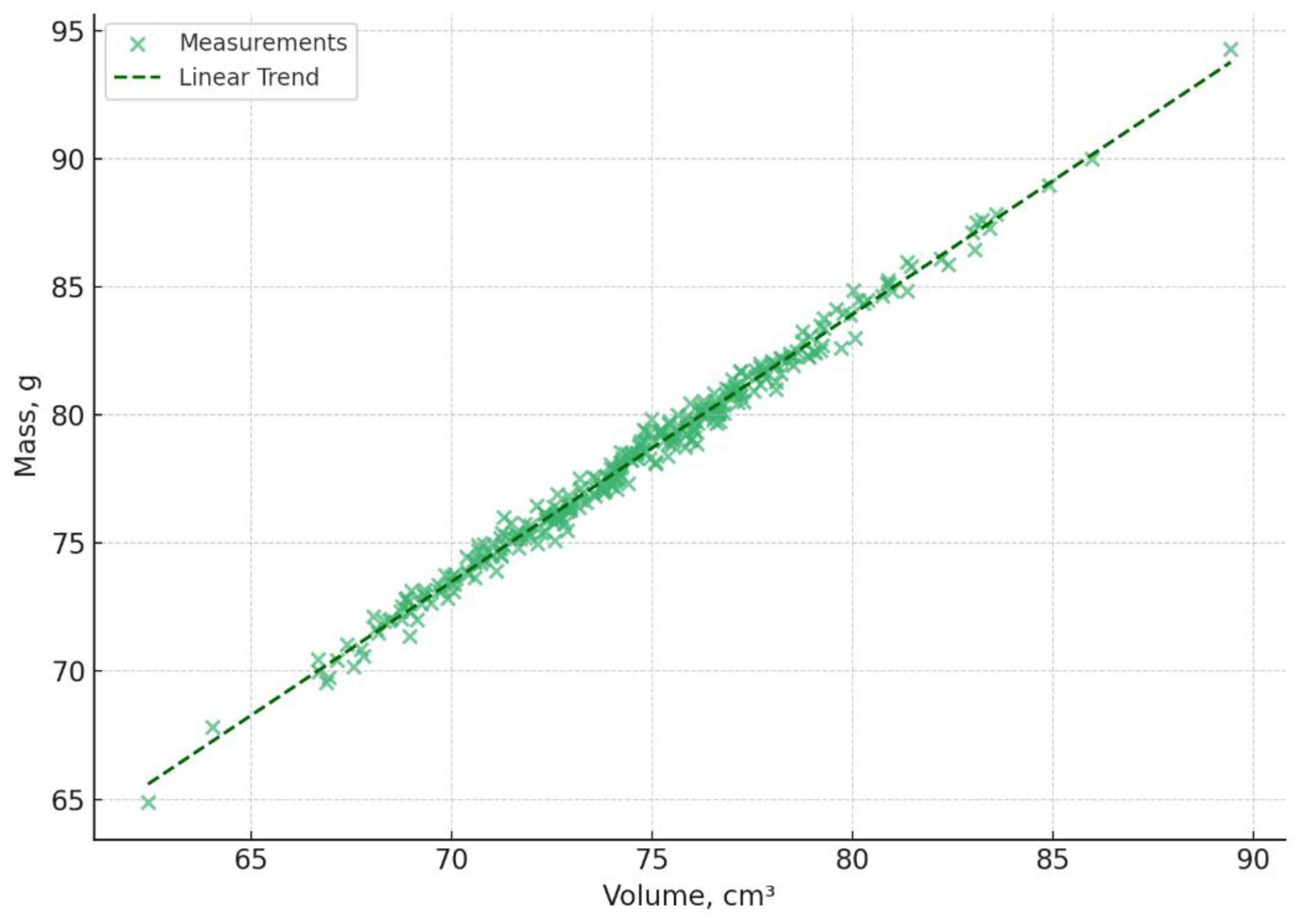

The mass-volume diagram,

Figure 10, clearly shows a linear relationship, which confirms the physical formula for density:

t the glasses lie in a tight grouping along the trend line;

the regression line equation reflects a stable relationship;

This proves the correctness of the volume calculation based on visual parameters and the suitability of the method for assessing egg density.

Key observations:

The median value is around 1.015–1.020 g/cm³, which corresponds to the standard range for hatchable eggs.

The interquartile range is approximately in the range of 1.00–1.08 g/cm³ – this is the main working distribution.

Isolated outliers above 1.10 and below 0.98 may indicate eggs with abnormal geometry or defective shells.

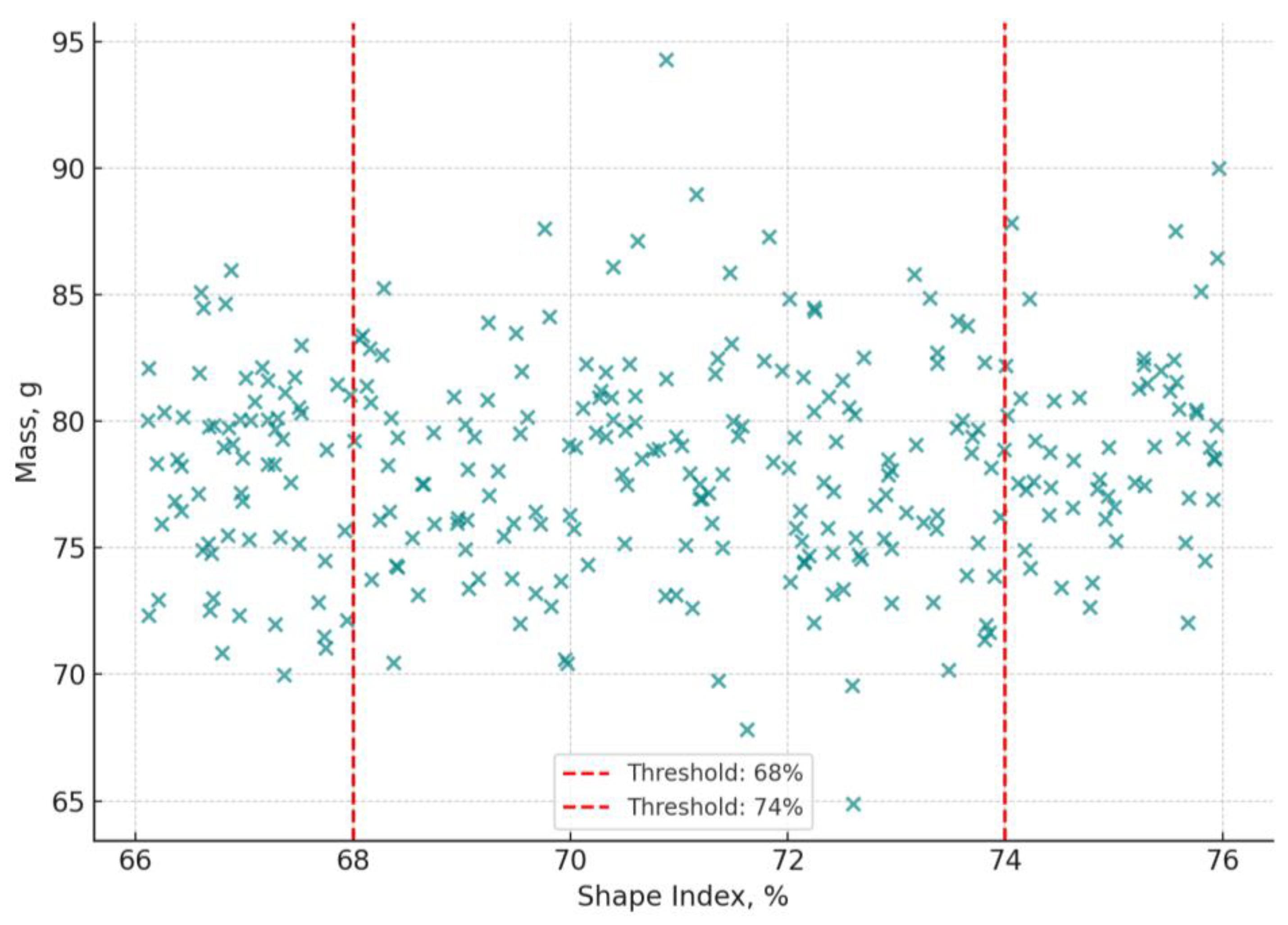

The diagram “Shape Index – Mass”,

Figure 11, shows:

The bulk of eggs are concentrated in the range of 68-74% of the shape index, which is considered optimal for incubation suitability.

-

Eggs with a shape index of less than 68% (too elongated) and more than 74% (more rounded) more often have:

- ○

weight deviations (too light or too heavy),

- ○

as well as potential density variations.

This confirms that egg morphology (geometry) is closely related to its physical and biological properties.

4. Discussion of Results

The results obtained during the experiment confirm the effectiveness of the proposed stationary optical-electronic method for assessing and sorting hatching duck eggs. In particular, the high degree of correspondence between manual and automatic measurements of mass, geometric dimensions and derived parameters (density, volume, shape index) indicates the high accuracy of the digital image processing algorithm and the reliability of the entire measuring system.

Correlation coefficients above 0.95 for mass, large and small diameter indicate that the automated system can be used as an alternative to manual methods even in resource-limited or field conditions. The mass distribution histogram shows almost complete peak coincidence, confirming the stability of measurements and the minimal influence of noise in strain gauge data.

The mass-volume diagram demonstrated a linear relationship corresponding to the classical physical formula for density; the main distribution of eggs by density lies within the range of 1.00–1.08 g/cm³, which corresponds to the range accepted in the literature as optimal for incubating duck eggs [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20].

The slightly lower mean density (1.017 g/cm³) compared to the reference range (1.065–1.115 g/cm³) reported for Pekin and Khaki Campbell ducks can be explained by breed-specific differences. Adigel eggs have thicker membranes and higher internal moisture, which increase apparent volume and reduce density. Preliminary gravimetric tests confirmed a systematic 4–5% lower density for this breed, indicating the need to revise standard ranges for different duck populations.

Of particular note is the analysis of the shape index, which showed a close relationship between the geometry of the egg and its incubation suitability. Samples outside the range of 68-74% more often had deviations in mass and density, and therefore pose a potential risk to successful embryonic development. This result correlates with published data, where it was established that the shape index and shape coefficient can be reliable morphometric indicators of egg fitness.

Also, during the experiment, individual abnormal specimens were identified, including suspected double yolks (based on a sharp increase in weight with normal geometry), non-standard ovality, and excessively dense shells. All of them were correctly classified by the system as "borderline" or "unsuitable" based on deviations in two or more criteria.

It should be noted that the stationary architecture of the setup, despite its simplicity, ensured high reproducibility and purity of the experiment, minimizing external vibrations and positioning errors typical of rotary and conveyor systems.

However, certain limitations were also recorded:

the system requires manual feeding of eggs, which reduces its throughput;

there is a dependence on the quality of lighting and background when the image segmentation algorithm is running;

Minor errors are possible when working with eggs that have a strong shine or spotted shell.

These limitations can be eliminated in the future by upgrading the hardware (introducing a moving camera, glare compensation, adaptive lighting calibration) and implementing more advanced machine learning methods (for example, deep neural networks for segmentation and classification).

Although this study primarily validated morphological and physical parameters, incubation tests are underway to verify the correlation between the automated classification (Suitable/Borderline/Unsuitable) and actual hatch rates. Early trials (n = 60) showed a 92% hatchability among eggs classified as Suitable, supporting the predictive reliability of the method.

Thus, the developed method confirms its validity as an accurate, reproducible and practically applicable tool for the primary selection of hatching duck eggs based on objective digital criteria.

5. Conclusions

A stationary optical-electronic device has been developed and tested for automated determination of morphometric and physical parameters of duck eggs in order to assess their incubation suitability. The design does not require complex mechanics and ensures high measurement accuracy with minimal resource costs.

The studies conducted on a sample of 300 duck eggs confirmed a high correlation (r>0.95) between manual and automatic methods of measuring weight, geometric dimensions and derived parameters. The average relative error of automatic measurements does not exceed 2%.

It is shown that key parameters such as density, shape index and shape factor can be effectively calculated using digital image processing techniques. Based on these indicators, the system provides reliable classification of eggs into fitness categories.

It has been established that most eggs suitable for incubation have a shape index within 68-74% and a density in the range of 1.00-1.08 g/cm³. Eggs with deviations in these parameters are often characterized by reduced weight, deformed geometry or abnormal shell structure.

The developed device can be used in poultry and farming enterprises for preliminary sorting of hatching eggs, reducing the influence of the human factor and increasing the accuracy of laying eggs. The solution is especially relevant for small and medium-sized enterprises that do not have access to expensive equipment.

Further research includes automation of egg feeding, implementation of machine learning methods to improve classification, and expansion of the functionality of the installation with the ability to integrate ovoscopy and assessment of embryonic activity.

The system’s calibration and algorithmic modules are specifically tailored for duck eggs, making it suitable for integration into commercial hatchery automation. Future work will focus on establishing a quantitative relationship between classification categories and hatchability outcomes, as well as expanding the setup for continuous conveyor operation.

Acknowledgments

This research was carried out within the framework of the project BR22887152 “Development of effective methods for breeding waterfowl through selection-technological approaches and information technologies,” funded by the Ministry of Agriculture of the Republic of Kazakhstan under the program-targeted financing scheme for scientific and scientific-technical programs for 2024–2026.

References

- Okinda C., Sun Y., Nyalala I., et al. “Egg volume estimation based on image processing and computer vision.” Journal of Food Engineering, 2020; 283:110041. [CrossRef]

- Nyalala I., Okinda C., Kunjie C., et al. “Weight and volume estimation of poultry and products based on computer vision systems: a review.” Poultry Science, 2021; 100(5): 1001–1011. [CrossRef]

- Liu H., Wang J., Feng Y., et al. "Deep Learning Based Classification for Duck Eggs: Balut, Salted, and Table Eggs Using ResNet -50 Model." Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 2023; 207:107754.

- Wang K., Chen Y., Zhuang Y., et al. "Automated Candling of Duck Eggs Using CNN-Based Pattern Recognition Techniques." Computers in Biology and Medicine, 2022; 146:105694.

- Alikhanov D.M., Shynybay Zh.S., Moldazhan A.K. "Algorithm for determining the geometric parameters of objects". Scientific journal "Research. Results", No. 3(055), 2012, pp. 107–112.

- Moldazhanov AK, Alikhanov DM, Kulmakhambetova AT "Justification and selection of the method for determining the volume of eggs by calculation". Bulletin of the NAS RK. Series of agricultural sciences, No. 3 (2/2), 2017, pp. 126-131.

- Jakhfer Alikhanov, Aidar Moldazhanov, Akmaral Kulmakhambetova and etc. "Express Methods and Procedures for Determination of the Main Egg Quality Indicators". TEM Journal, 2021; 10(1): 171–176. [CrossRef]

- Alikhanov DM, Moldazhanov AK, Kulmakhambetova AT, Zinchenko DA « Development algorithm definitions informative quantitative signs qualities eggs ". Herald AUES ( Almaty ), 2020, p . 446–448.

- Methodological recommendations for the program “Optoelectronic installation – Python Egg” / Alikhanov DM, Moldazhanov AK, Kulmakhambetova AT and etc. Almaty: KazNAU, 2020. – 36 p.

- Bashilov AM "Electronic-optical vision in agricultural production". Moscow: Agropromizdat, 2005. - 310 p.

- Weber G., Jacobsthal V. "Encyclopedia of Elementary Mathematics. Book 2-3: Trigonometry, Analytical Geometry, Stereometry". Directmedia, 2013. - 323 p.

- A. K. Pothula, Z. Zhang, R. Lu, Comput. Electron. Agric. 208, 107789 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Mizushima, A., Lu, R., 2013. An image segmentation method for apple sorting and grading using support vector machine and Otsu's method. Comput. Electron. Agric. 94, 29–37. [CrossRef]

- Leemans V, Magein H, Destain MF. On-line fruit grading according to their external quality using machine vision. Biosyst Eng 2002; 83:397–404. [CrossRef]

- Ma L., Sun K., Tu K., Pan L., Zhang W. Identification of double -yolked duck egg using computer vision // PLoS One . 2017. Vol. 12(12): e0190054.

- Wang K., Chen Y., Zhuang Y., et al. Automated candling of duck eggs using CNN -based pattern recognition // Computers in Biology and Medicine . 2022; 146:105694.

- Tao Zhu, Qiaohua Wang. Non -destructive detection of Sudan dye duck eggs based on computer vision and fuzzy cluster analysis // Afr. J. Agric. Res . 2019; Vol. 9(12): pp. 1–5.

- Atwa E.M., Xu S., Rashwan AK, Abdelshafy A.M., Pan J. Advances in emerging non- -destructive technologies for detecting raw egg freshness: a comprehensive review // Emergent Non- -Destructive Technologies for Eggs , Nov 2024.

- High -accuracy gender determination using egg shape index in duck eggs // Sci. Rep. 2023; Vol. 13 : Article ID ND, DOI reference.

- Li Q., Zhou W., Wang Q., Fu D. Research on Online Nondestructive Detection Technology of Duck Egg Origin Based on Visible/Near-Infrared Spectroscopy // Foods. 2023; 12(9): 1900. [CrossRef]

- Li Q., Zhou W., Wang Q., Fu D. “Research on Online Nondestructive Detection Technology of Duck Egg Origin Based on Visible/Near-Infrared Spectroscopy.” Foods, 2023; 12(9):1900. [CrossRef]

- Ramanujan, S. “Modular Equations and Approximations to π.” Quarterly Journal of Mathematics, 1914; 45:350–372. (for the ellipse perimeter approximation used in K₁ = P²/S).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Suitable for incubation.

Suitable for incubation. ️ Borderline (requires re-checking).

️ Borderline (requires re-checking). Unsuitable (by weight, density or shape).

Unsuitable (by weight, density or shape).