Submitted:

15 October 2025

Posted:

16 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

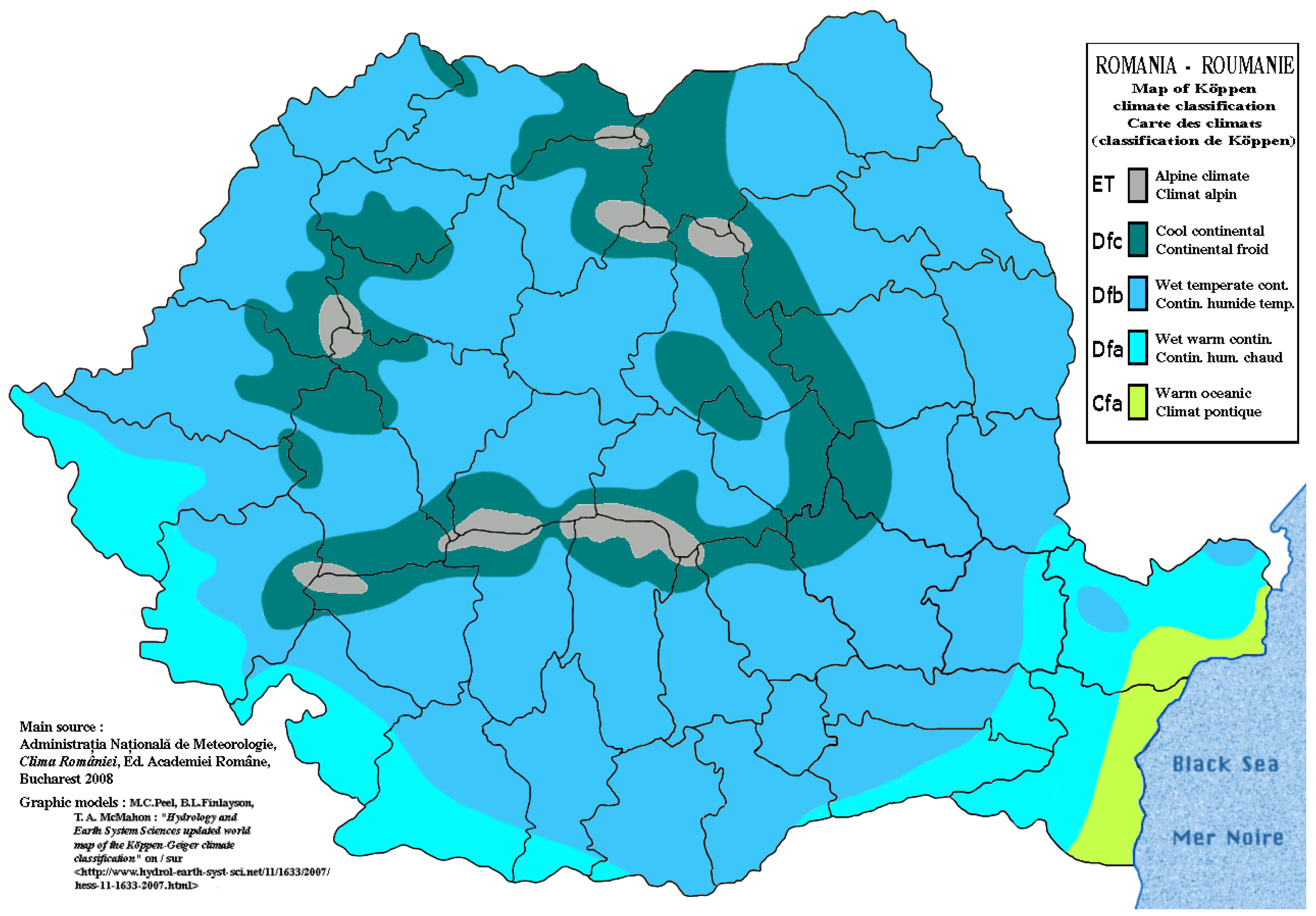

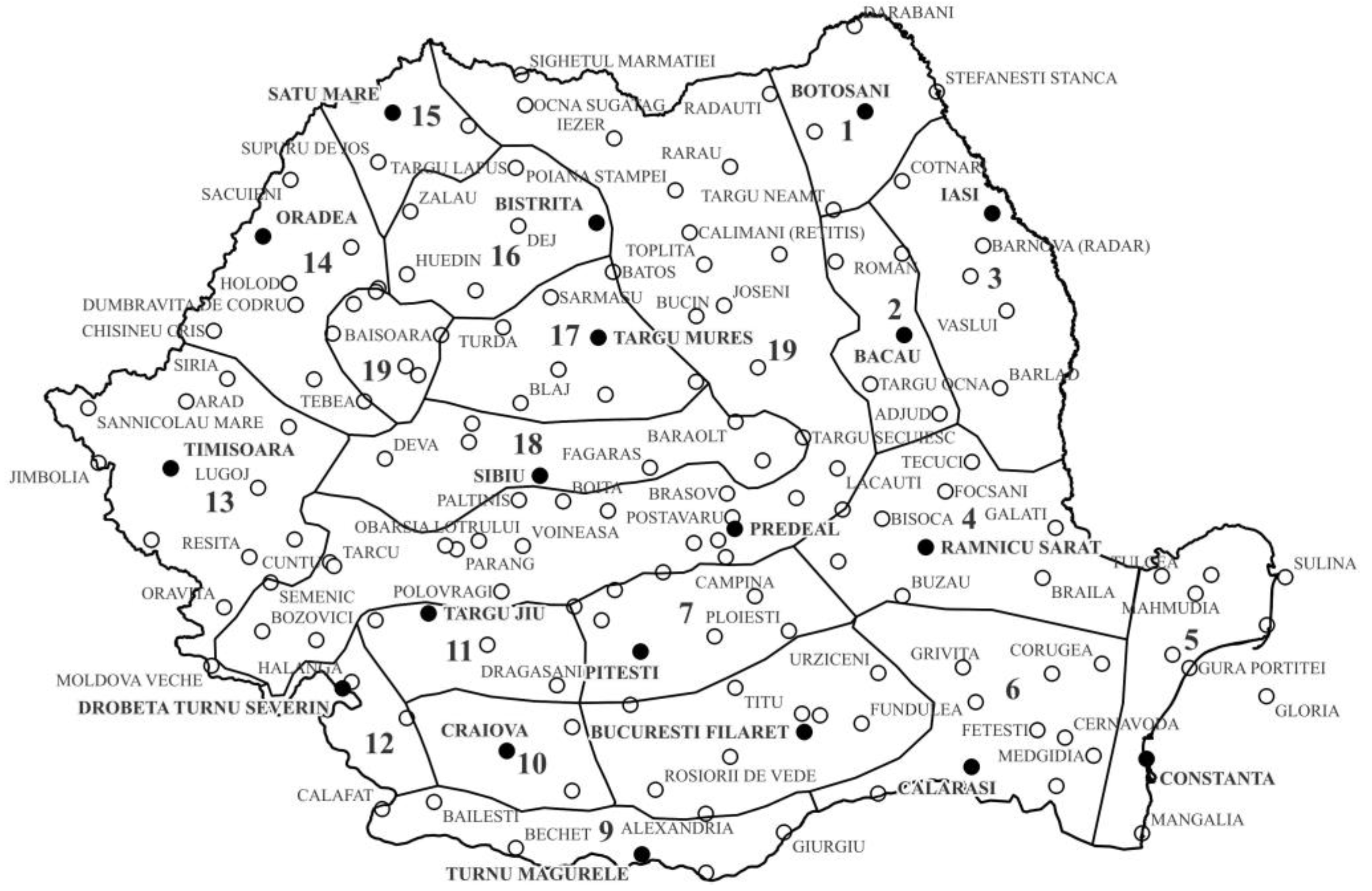

2.1. Study Area

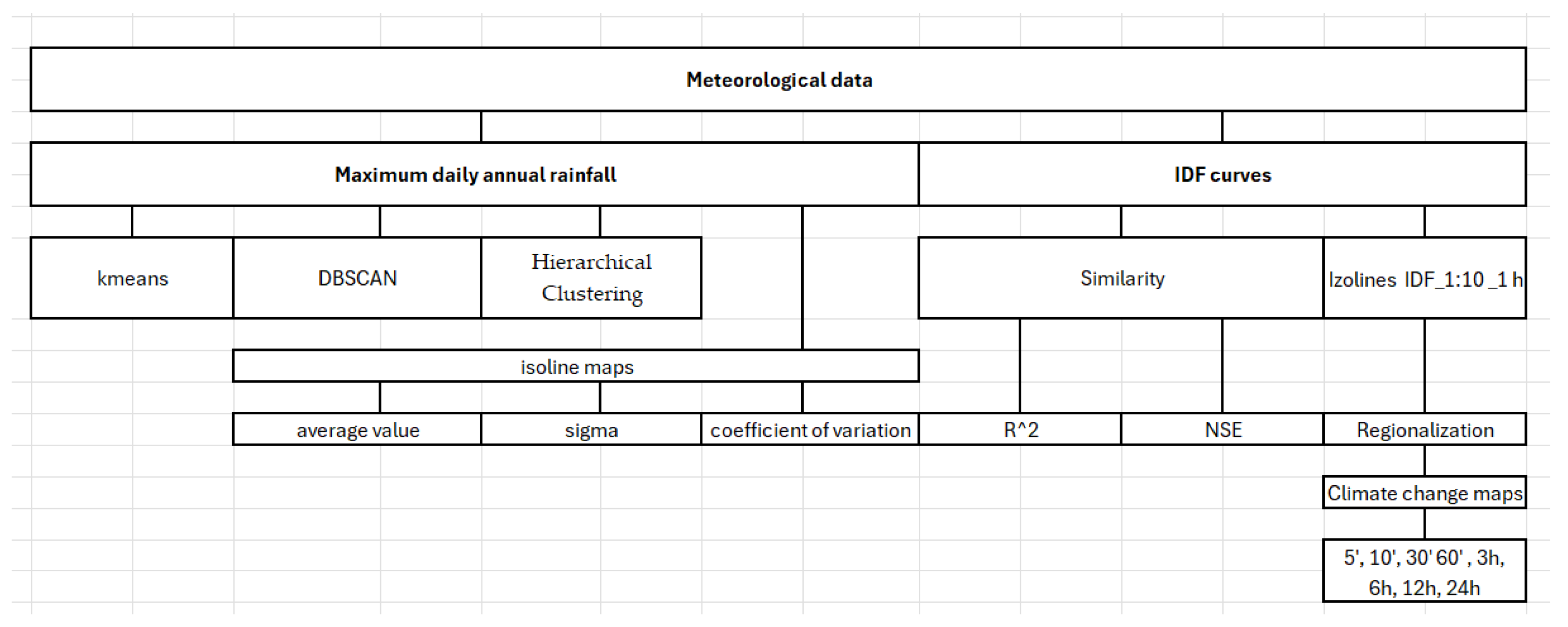

2.2. Research Framework

- The first approach used the annual maximum daily rainfall. The stations were grouped according to their coefficient of variation, applying different clustering methods: k-means, DBSCAN, and Hierarchical Clustering.

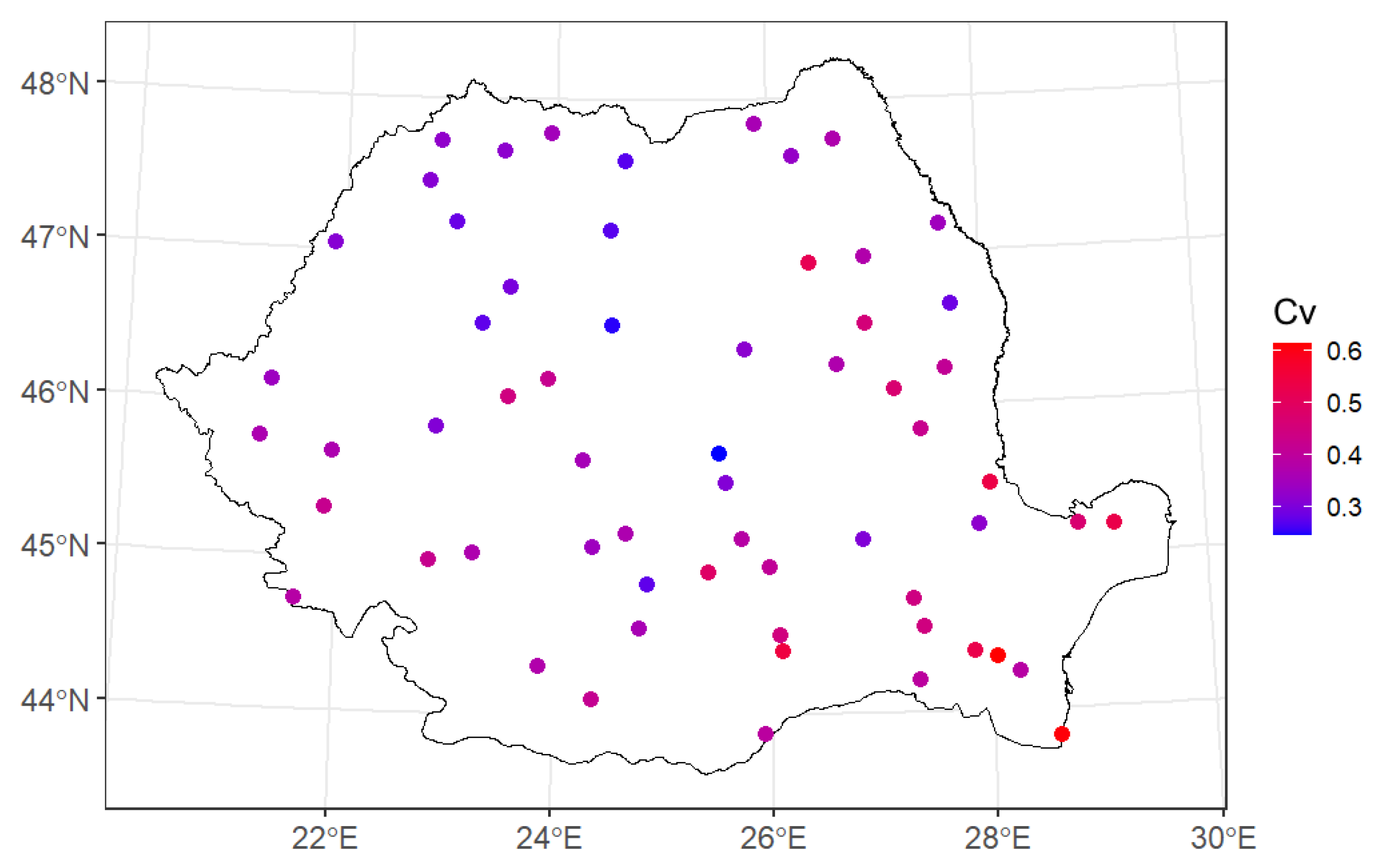

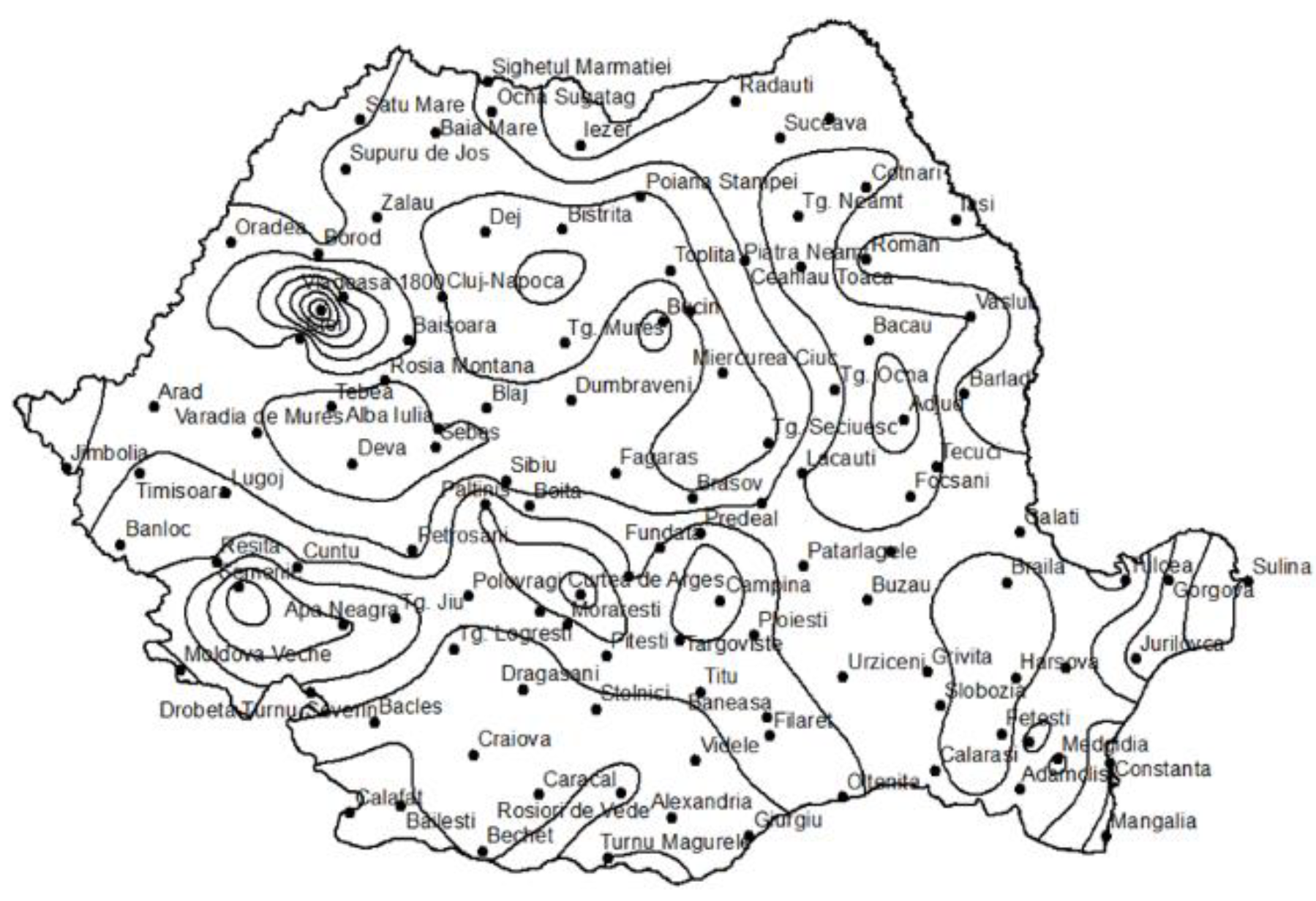

- For the same annual maximum daily rainfall of the meteorological stations, contour maps were obtained for each parameter (mean value, standard deviation, coefficient of variation) which were then analyzed in relation to their plausibility.

- Another attempt at regionalization consisted in searching for similarities between any pair of two stations. Similarity was accepted for the correlation coefficient and the Nash-Sutcliffe efficiency coefficient higher than 0.99.

- Another approach was regionalization based on the 1-hour rainfall depth for each station corresponding to the frequency of 1:10.

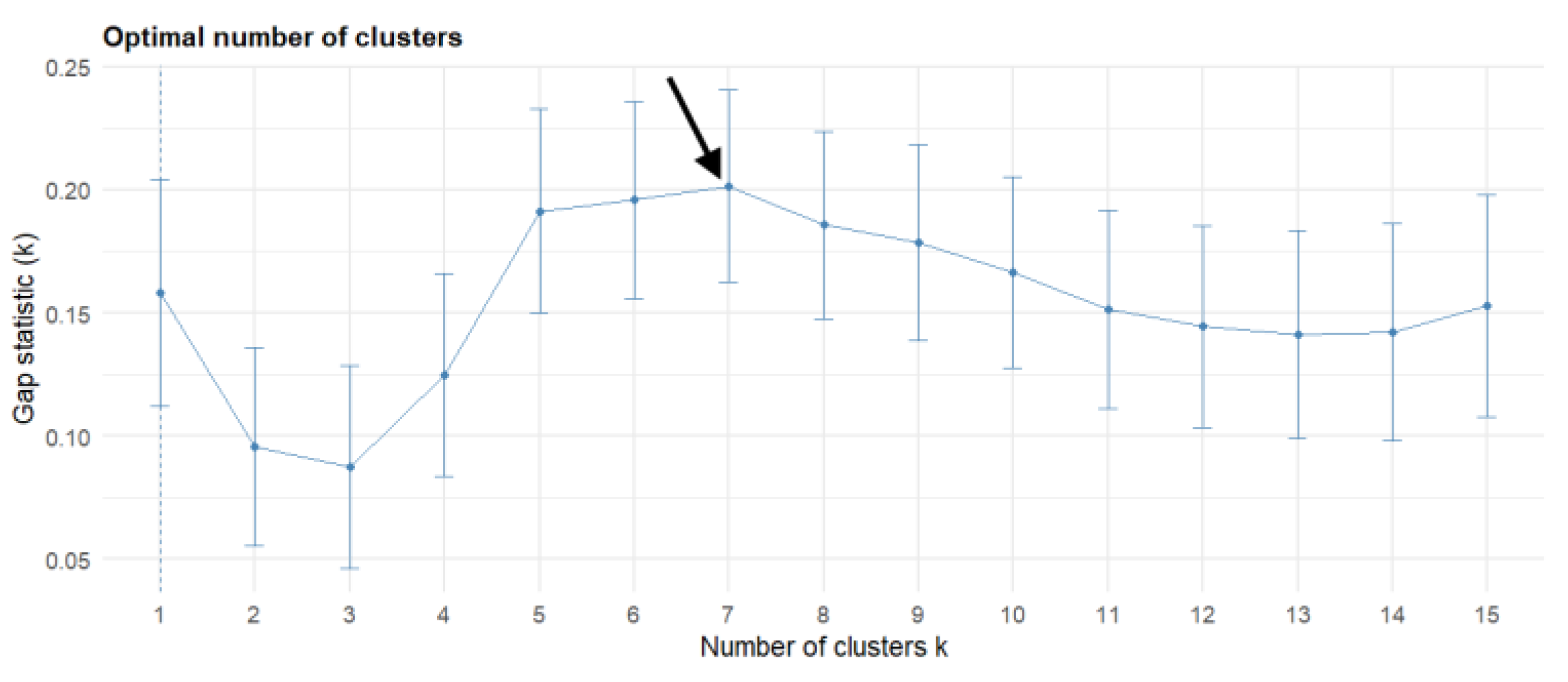

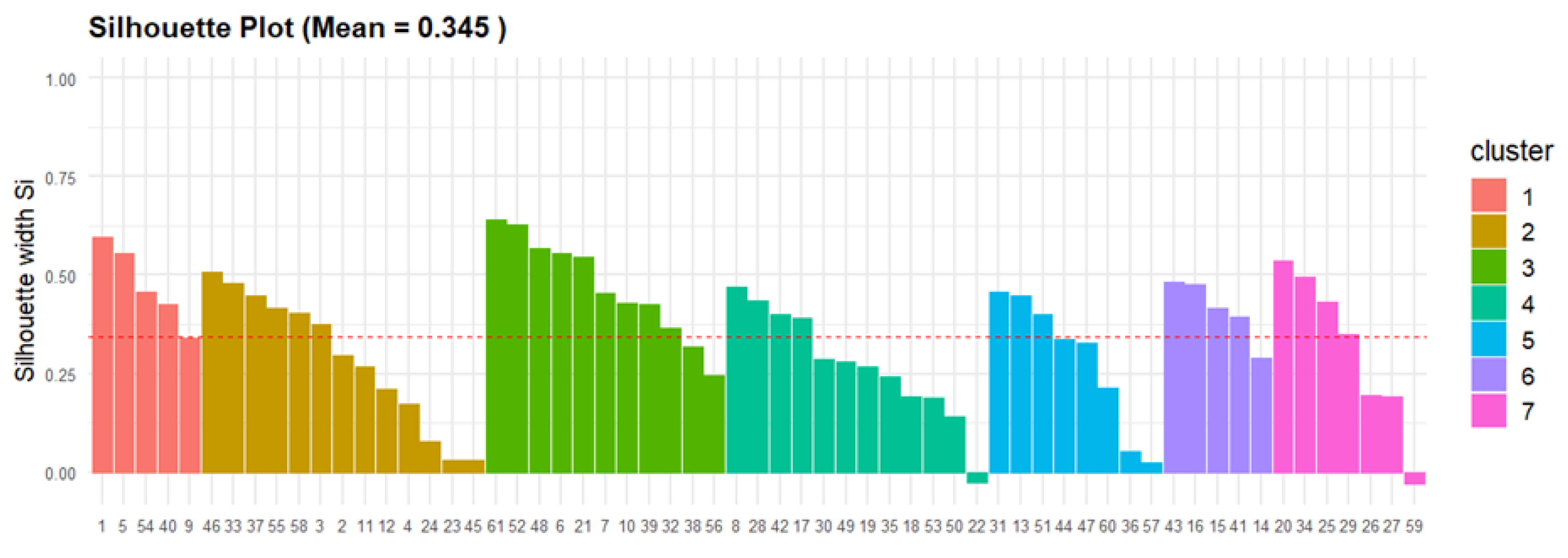

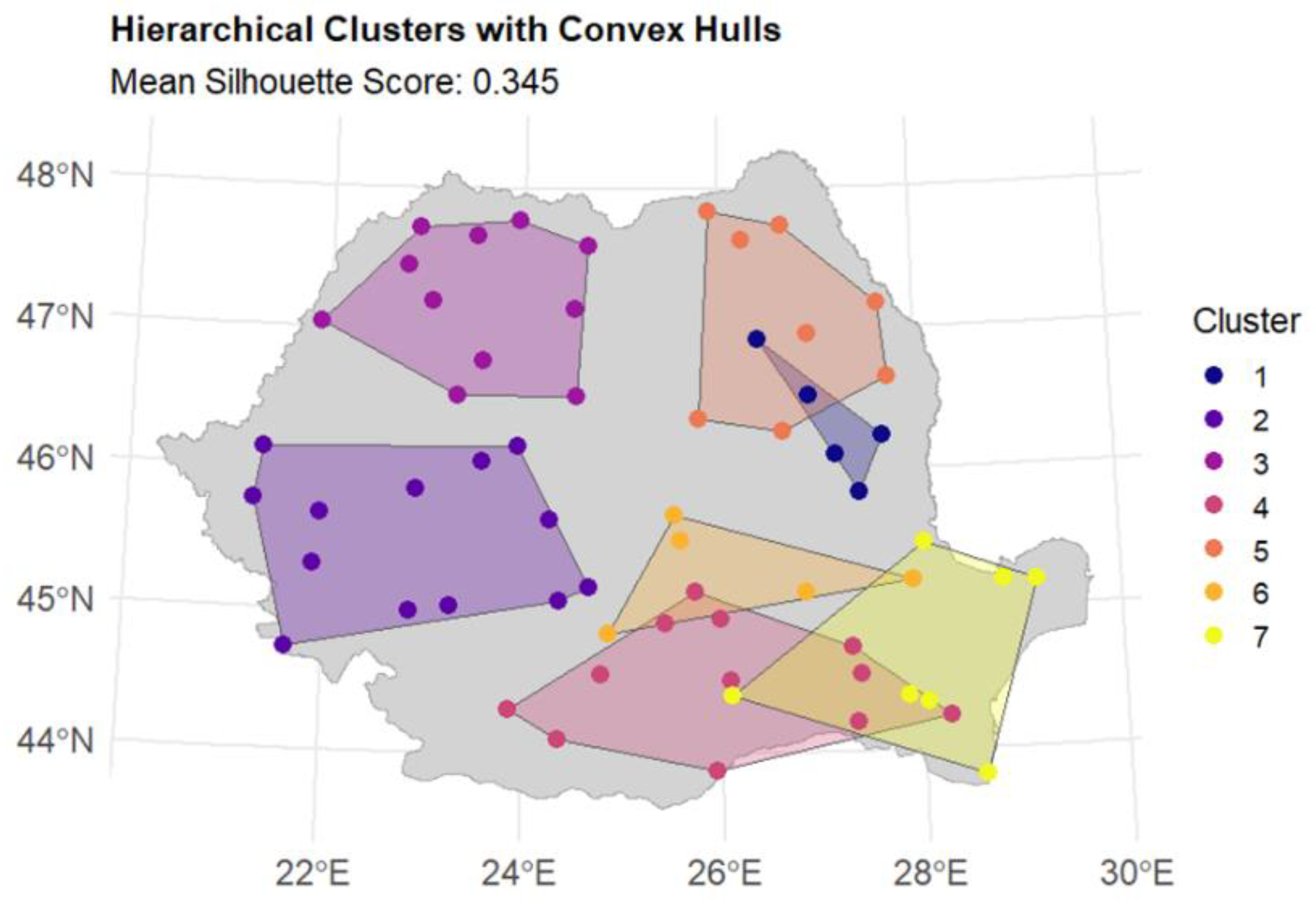

2.2.1. Clustering

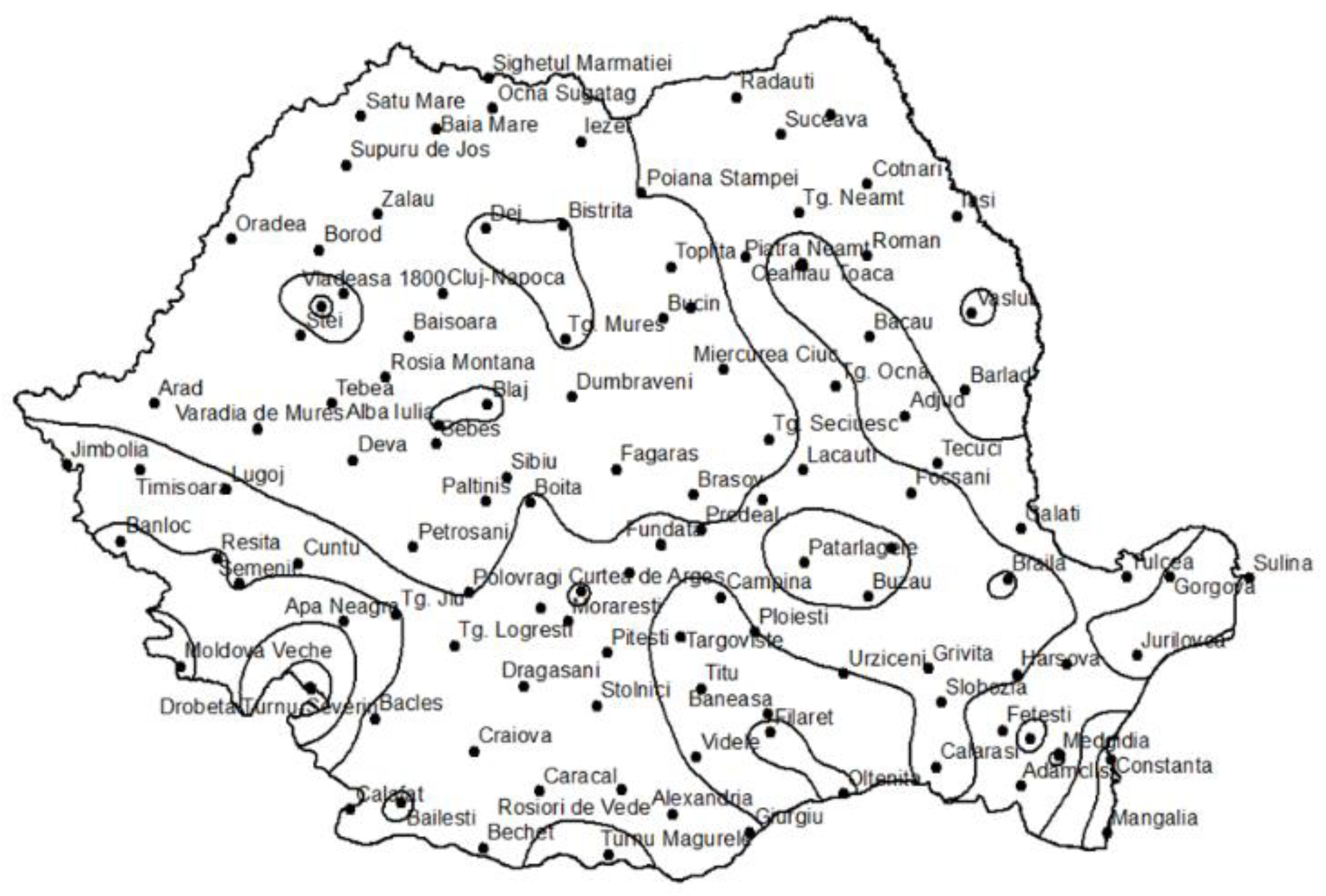

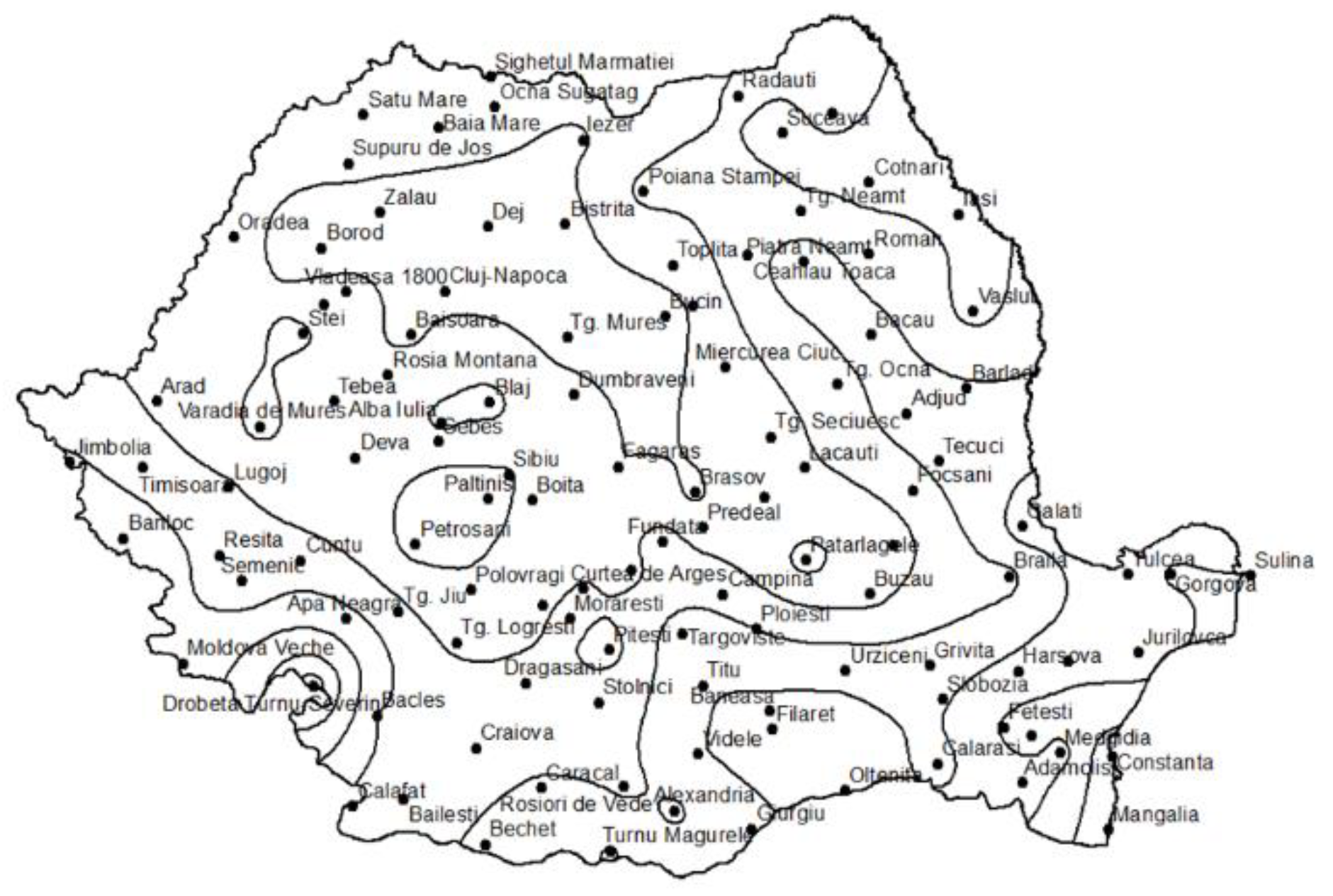

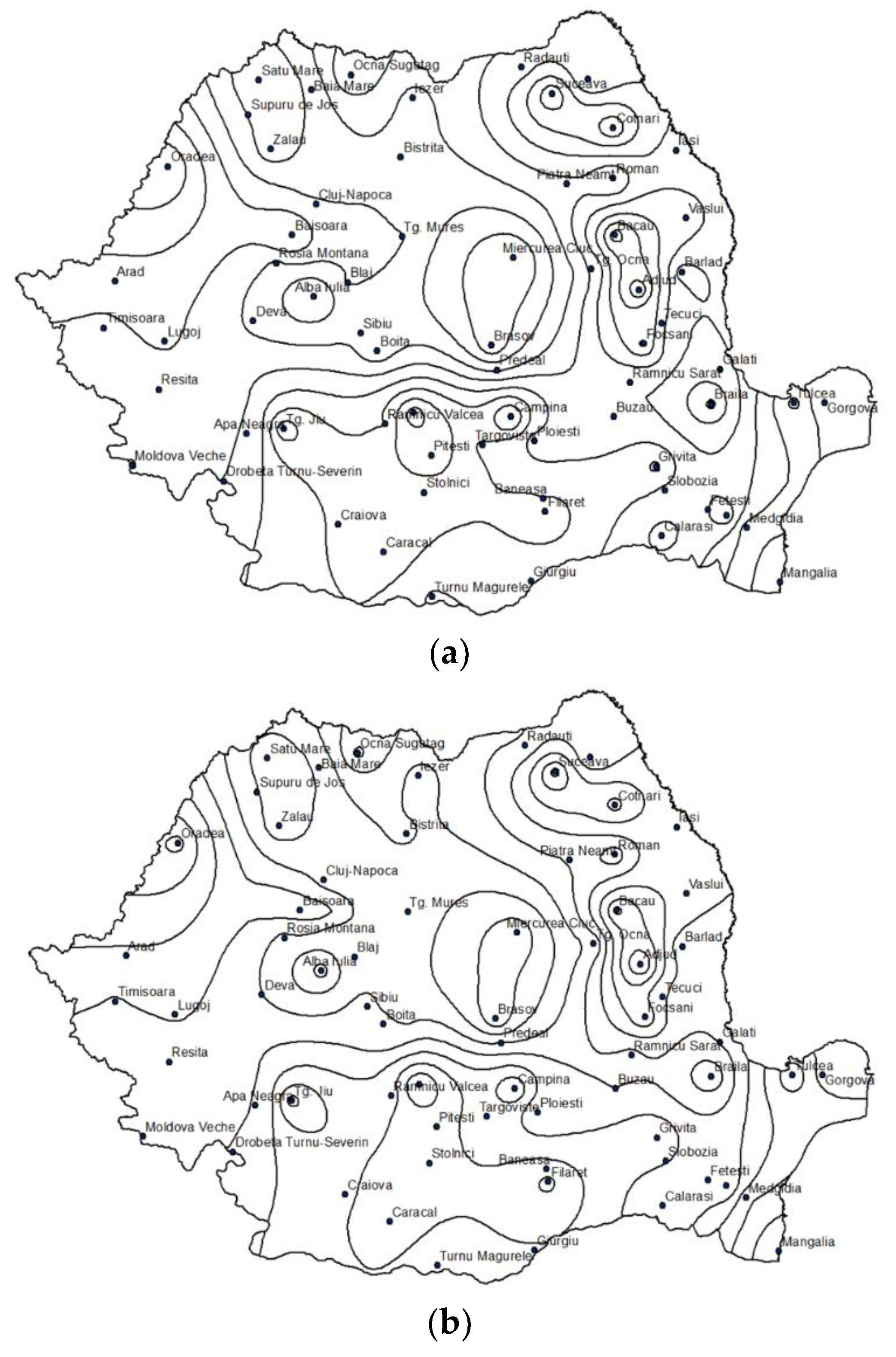

2.2.2. Isolines of statistical parameters of the annual series of maximum daily rainfall

2.2.3. Similarities between meteorological stations

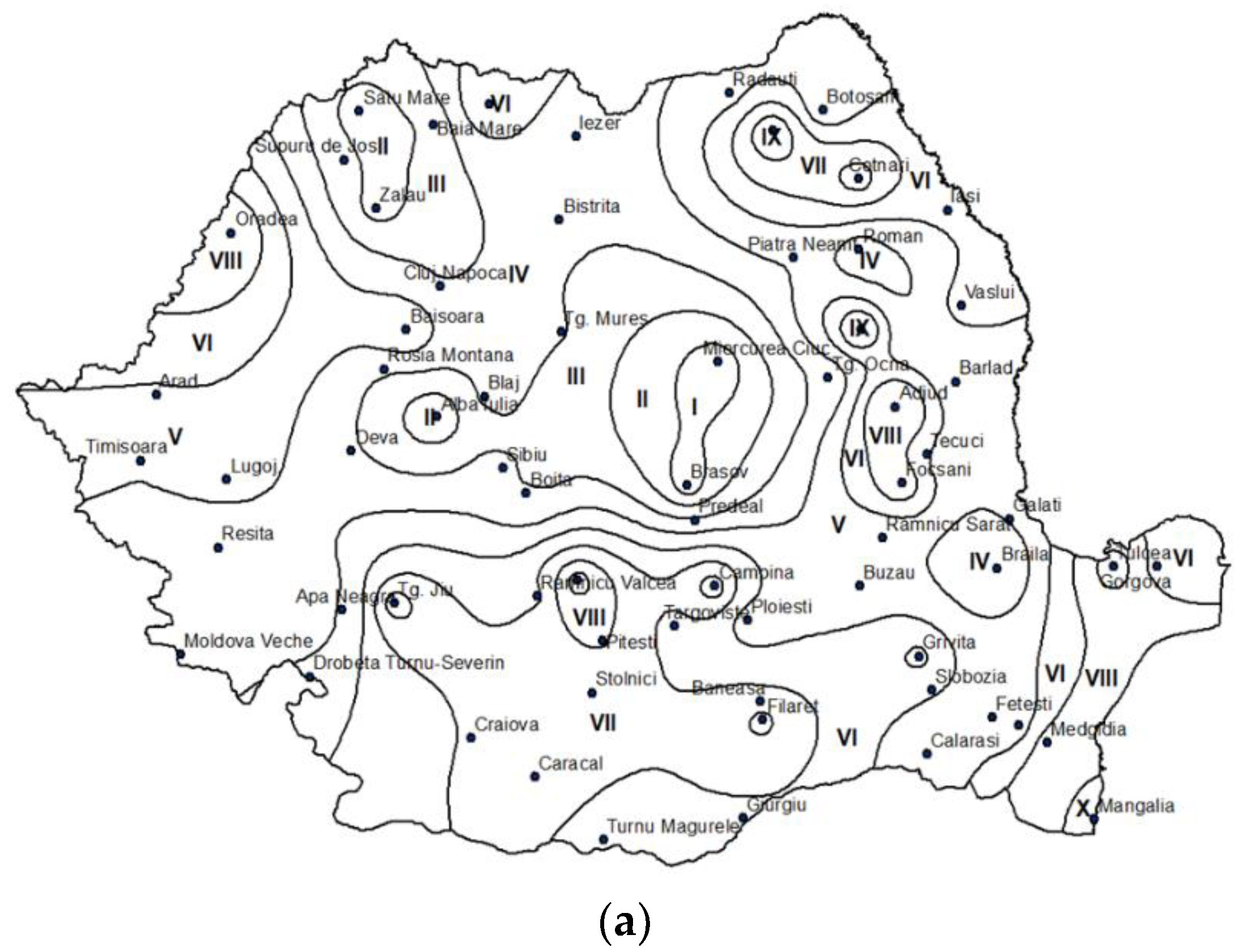

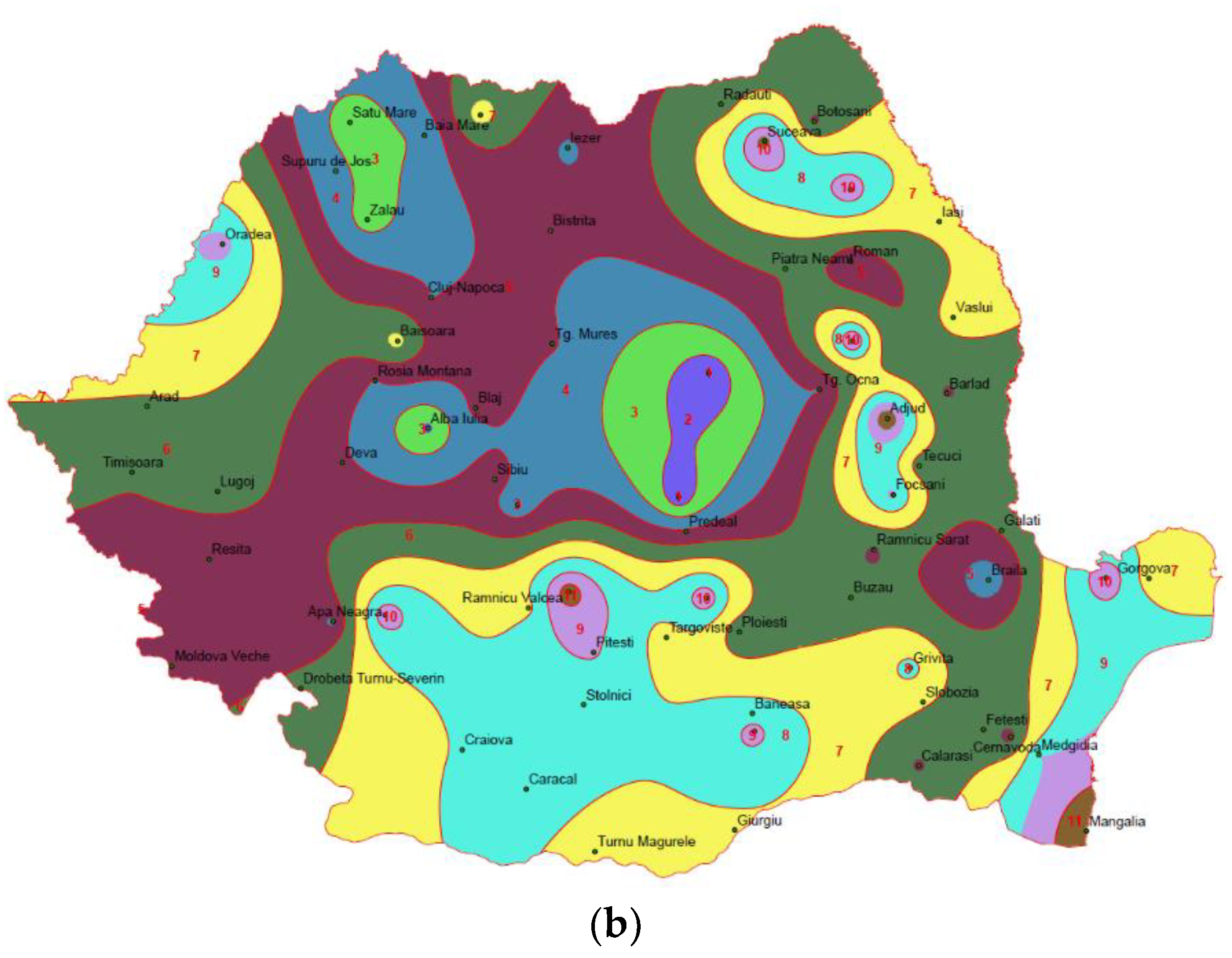

2.2.4. Isolines of the 1-hour accumulated rainfall depth corresponding to the frequency of 1:10

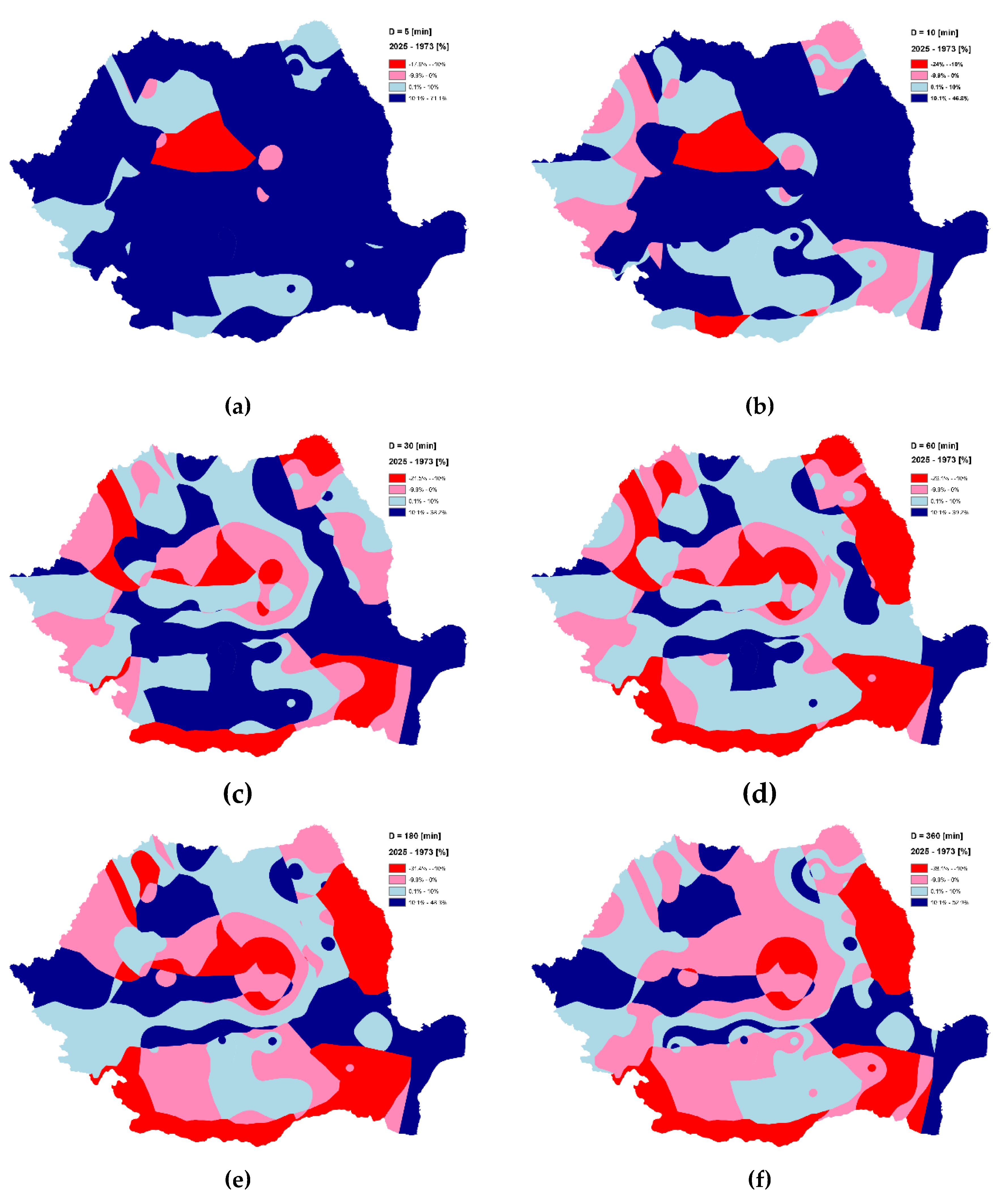

2.2.5. Investigating climate change

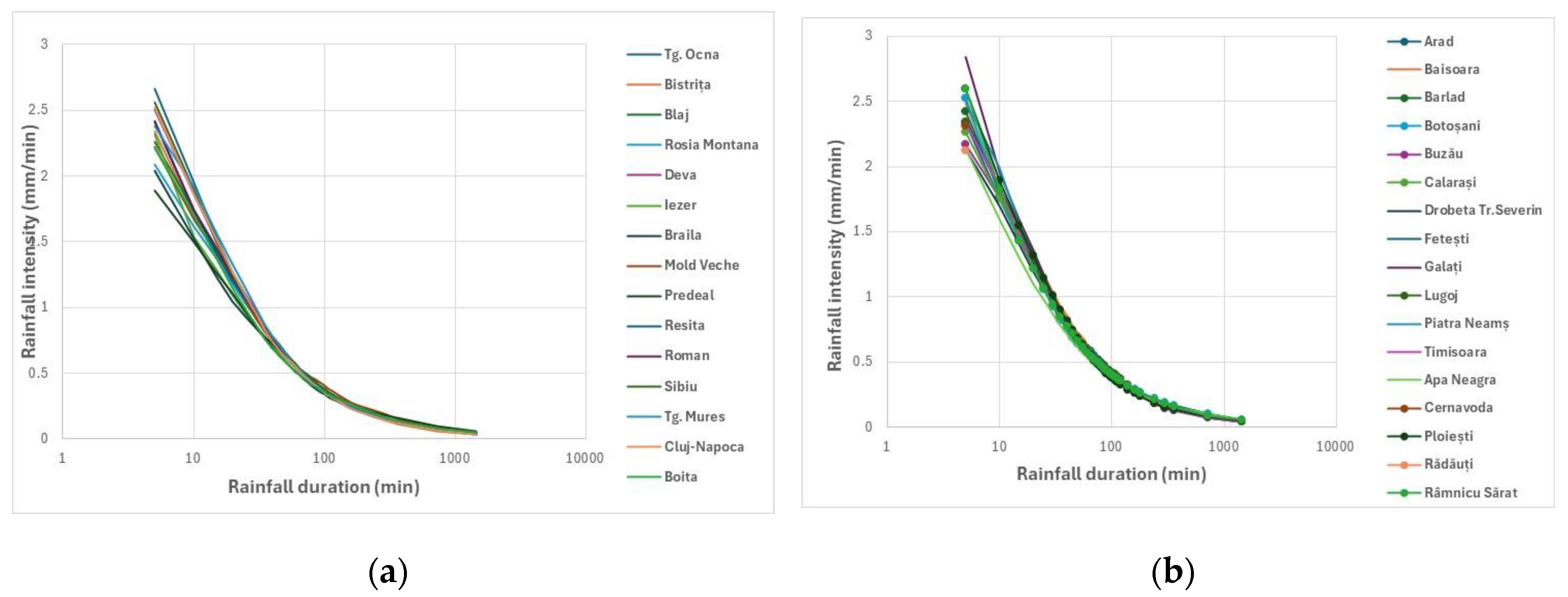

2.2.6. Using the Sherman relation for IDF curves

3. Results

3.1. Clustering

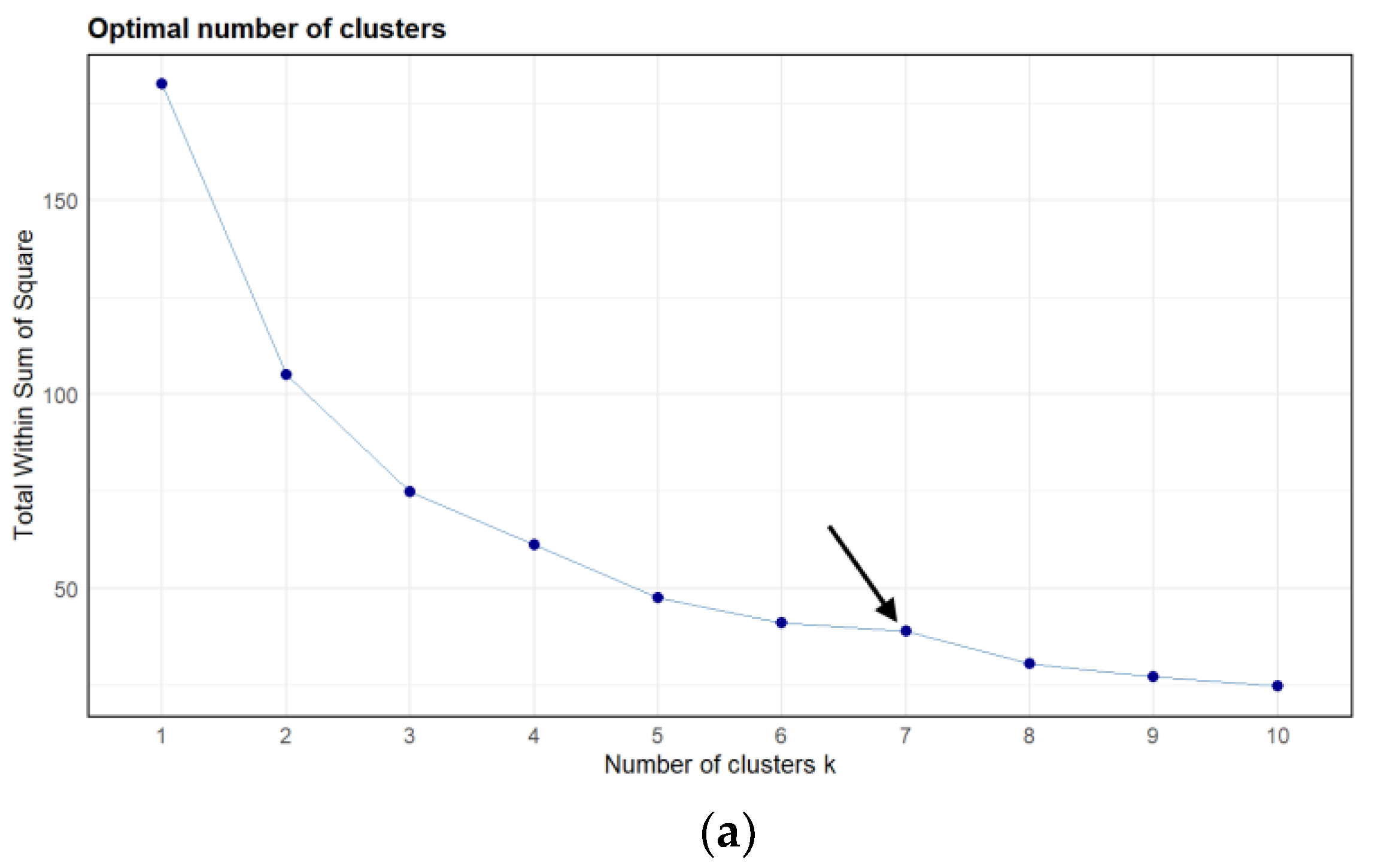

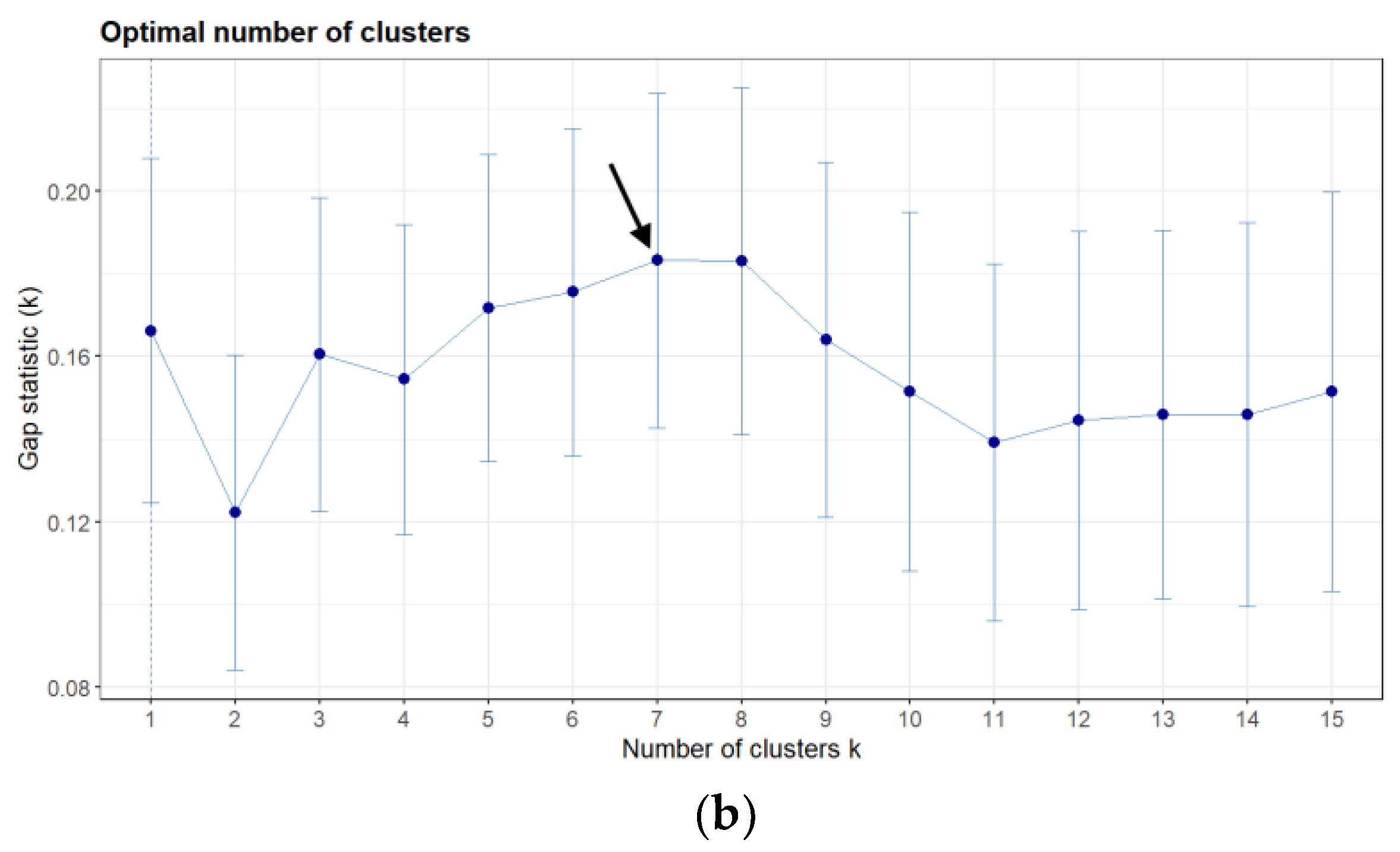

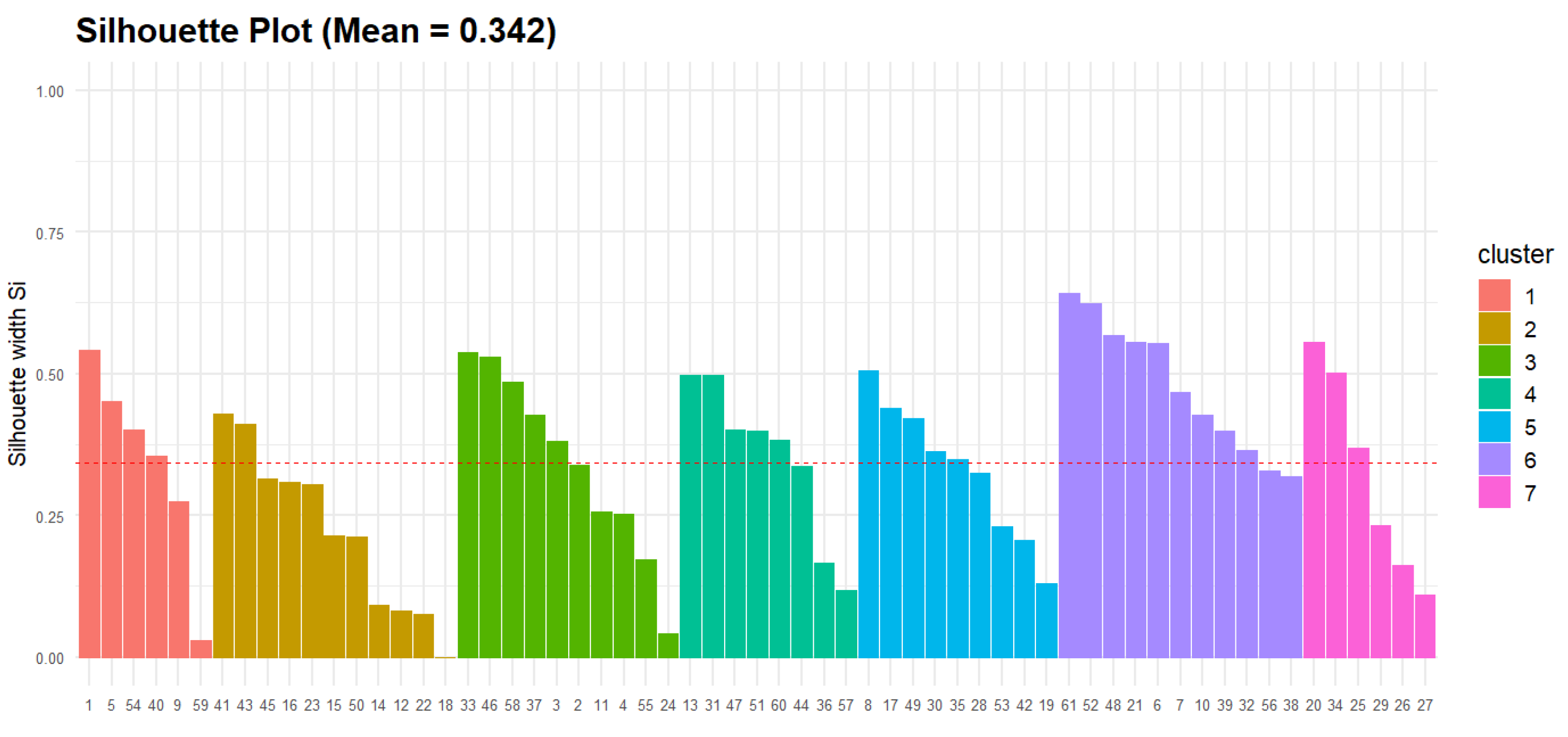

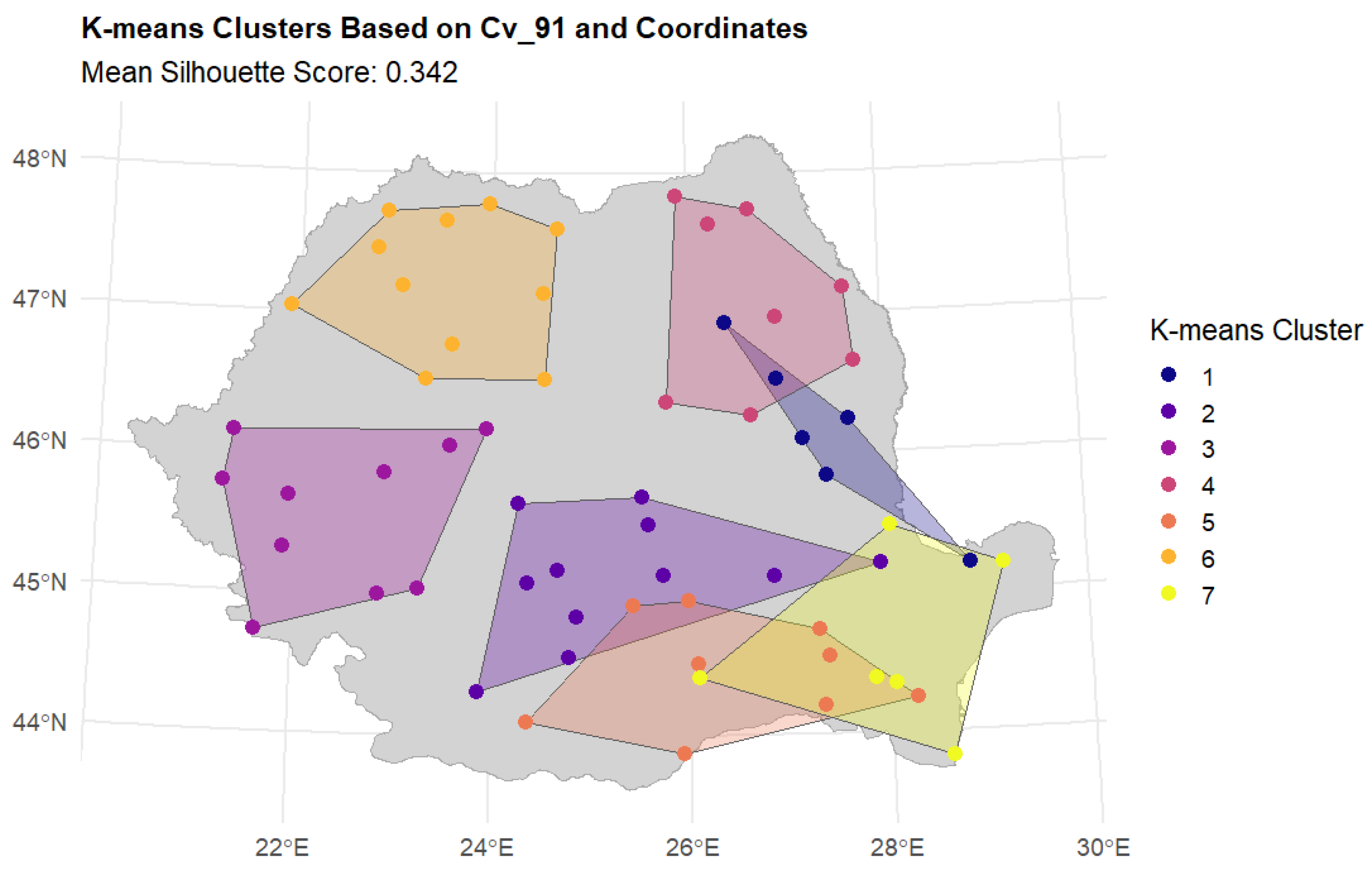

- k-means

- DBSCAN

- Hierarchical Clustering

3.2. Isolines of the Main Parameters for the Annual Maximum Daily Rainfall

3.3. Similarities Between Meteorological Stations

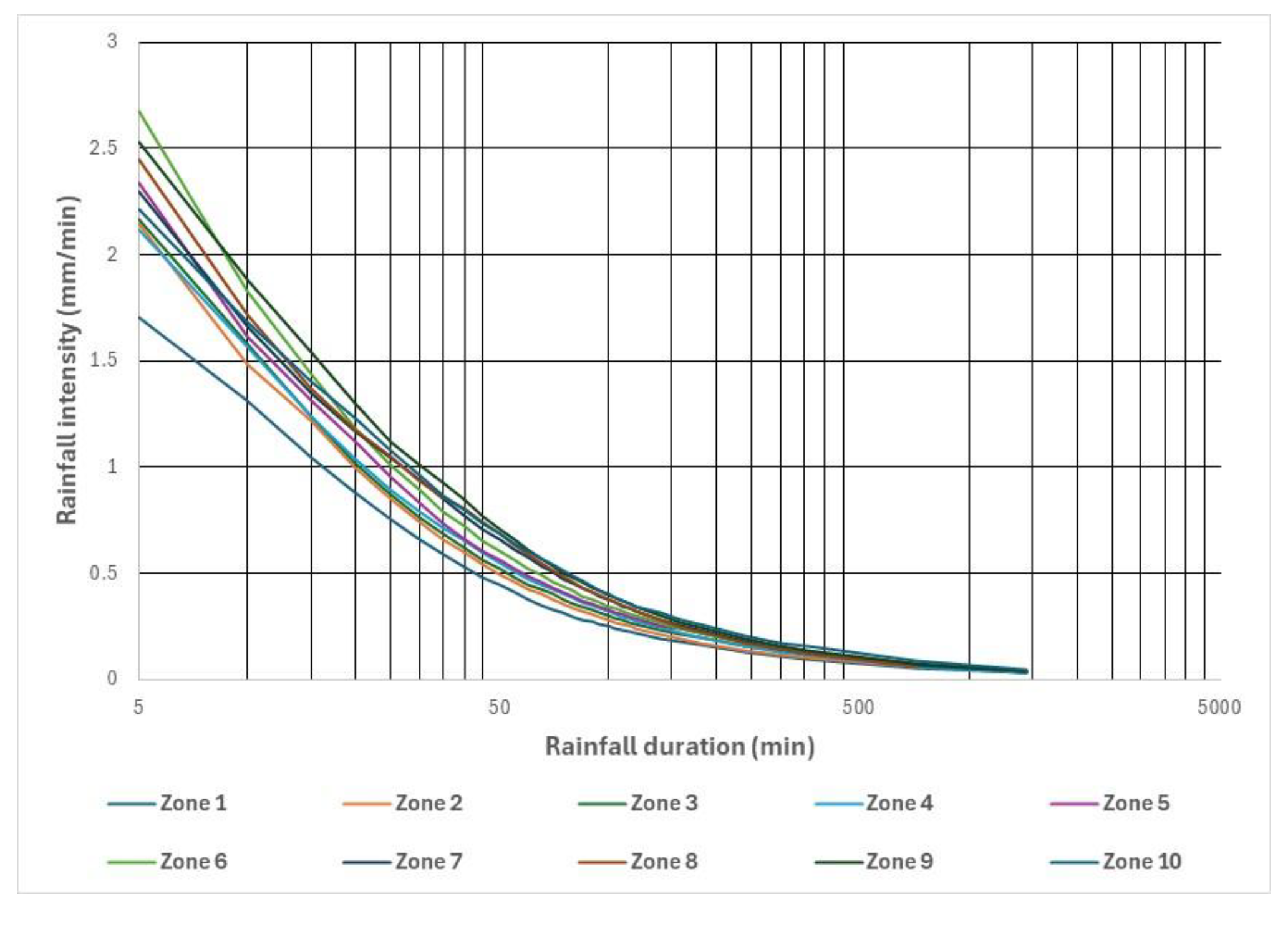

3.4. Regionalization Based on 1-Hour Accumulated Rainfall Depth

3.5. Climate Change Investigation

4. Discussion

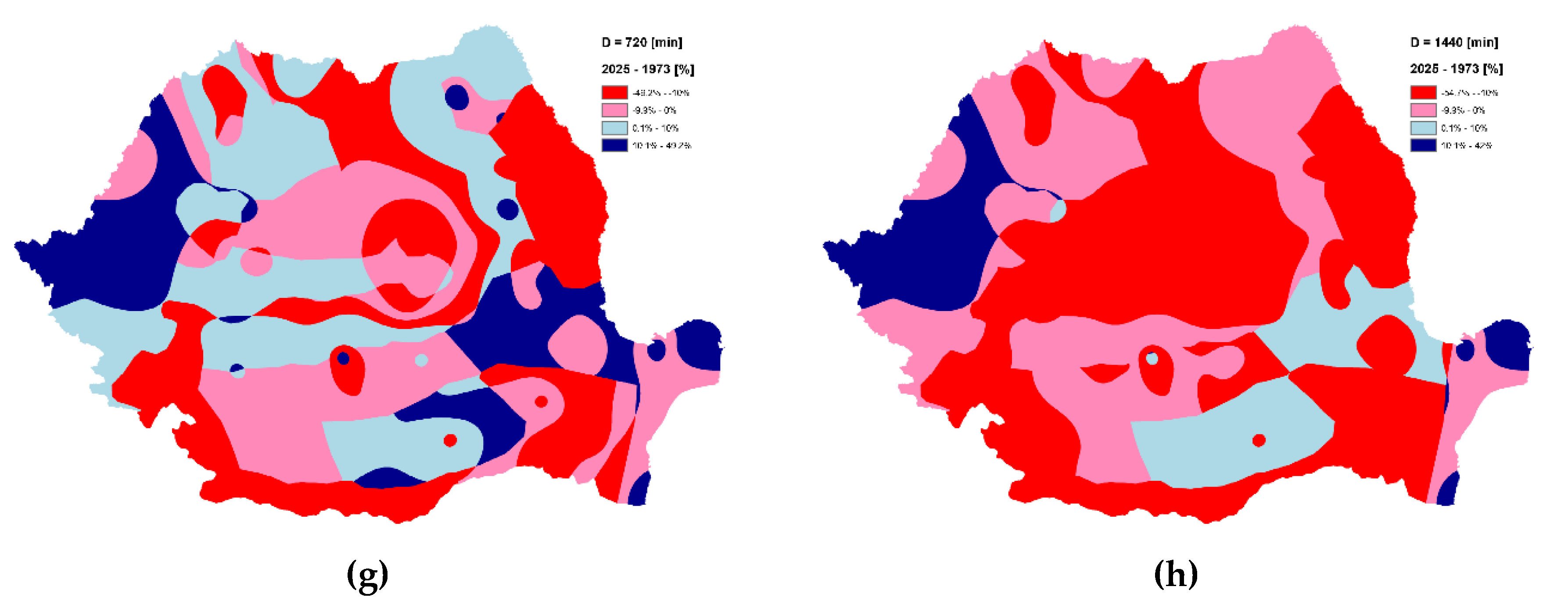

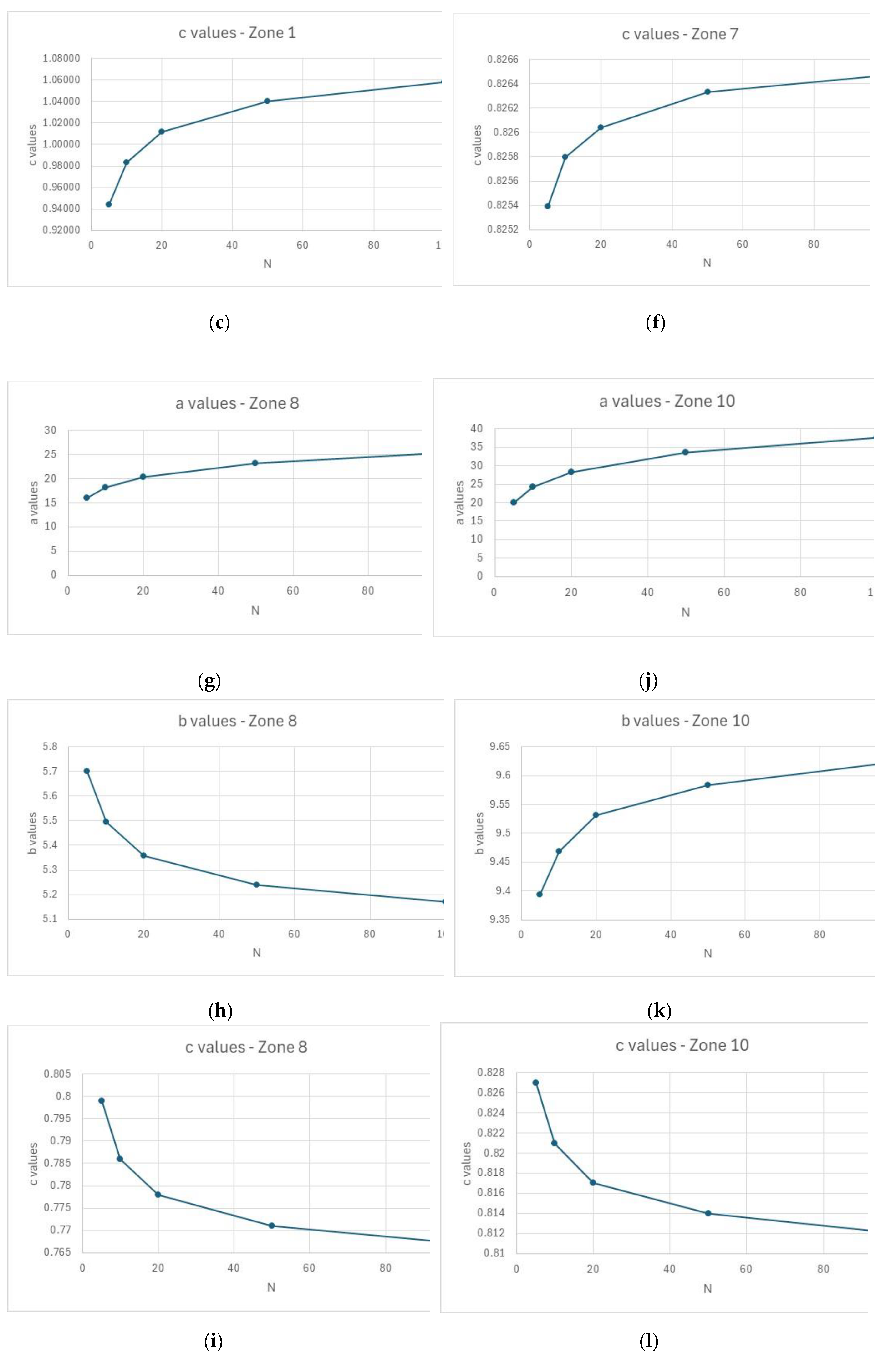

4.1. Considerations Regarding the Coefficients a, b and c

| Coefficients |

Zone I |

Zone II |

Zone III |

Zone IV |

Zone V |

Zone VI |

Zone VII |

Zone VIII |

Zone IX |

Zone X |

| 21.182 | 16.975 | 16.239 | 16.350 | 14.865 | 16.368 | 18.144 | 16.017 | 24.502 | 19.942 | |

| 9.337 | 5.594 | 5.526 | 6.304 | 4.679 | 3.933 | 7.444 | 5.701 | 8.442 | 9.394 | |

| 0.944 | 0.878 | 0.854 | 0.843 | 0.817 | 0.829 | 0.8254 | 0.799 | 0.876 | 0.827 |

| Coefficients |

Zone I |

Zone II |

Zone III |

Zone IV |

Zone V |

Zone VI |

Zone VII |

Zone VIII |

Zone IX |

Zone X |

| 29.873 | 18.400 | 20.543 | 20.224 | 19.170 | 20.601 | 21.645 | 18.181 | 31.405 | 24.184 | |

| 10.228 | 5.298 | 5.906 | 6.371 | 4.950 | 3.918 | 7.431 | 5.494 | 8.824 | 9.468 | |

| 0.983 | 0.865 | 0.874 | 0.850 | 0.833 | 0.835 | 0.8258 | 0.786 | 0.888 | 0.821 |

| Coefficients |

Zone I |

Zone II |

Zone III |

Zone IV |

Zone V |

Zone VI |

Zone VII |

Zone VIII |

Zone IX |

Zone X |

| 39.095 | 19.837 | 24.824 | 23.947 | 23.368 | 24.683 | 24.999 | 20.325 | 38.174 | 28.306 | |

| 10.897 | 5.085 | 6.193 | 6.418 | 5.136 | 3.912 | 7.421 | 5.359 | 9.100 | 9.532 | |

| 1.012 | 0.855 | 0.888 | 0.854 | 0.844 | 0.840 | 0.8260 | 0.778 | 0.896 | 0.817 |

| Coefficients |

Zone I |

Zone II |

Zone III |

Zone IV |

Zone V |

Zone VI |

Zone VII |

Zone VIII |

Zone IX |

Zone X |

| 51.953 | 21.747 | 30.553 | 28.812 | 28.904 | 29.969 | 29.349 | 23.158 | 47.065 | 33.607 | |

| 11.555 | 4.872 | 6.491 | 6.470 | 5.320 | 3.906 | 7.418 | 5.240 | 9.368 | 9.584 | |

| 1.040 | 0.845 | 0.903 | 0.859 | 0.855 | 0.844 | 0.8263 | 0.771 | 0.905 | 0.814 |

| Coefficients |

Zone I |

Zone II |

Zone III |

Zone IV |

Zone V |

Zone VI |

Zone VII |

Zone VIII |

Zone IX |

Zone X |

| 62.371 | 23.198 | 34.910 | 32.444 | 33.112 | 33.938 | 32.605 | 25.289 | 53.766 | 37.645 | |

| 11.974 | 4.744 | 6.664 | 6.495 | 5.430 | 3.903 | 7.410 | 5.170 | 9.519 | 9.624 | |

| 1.058 | 0.839 | 0.912 | 0.862 | 0.862 | 0.847 | 0.8265 | 0.767 | 0.909 | 0.812 |

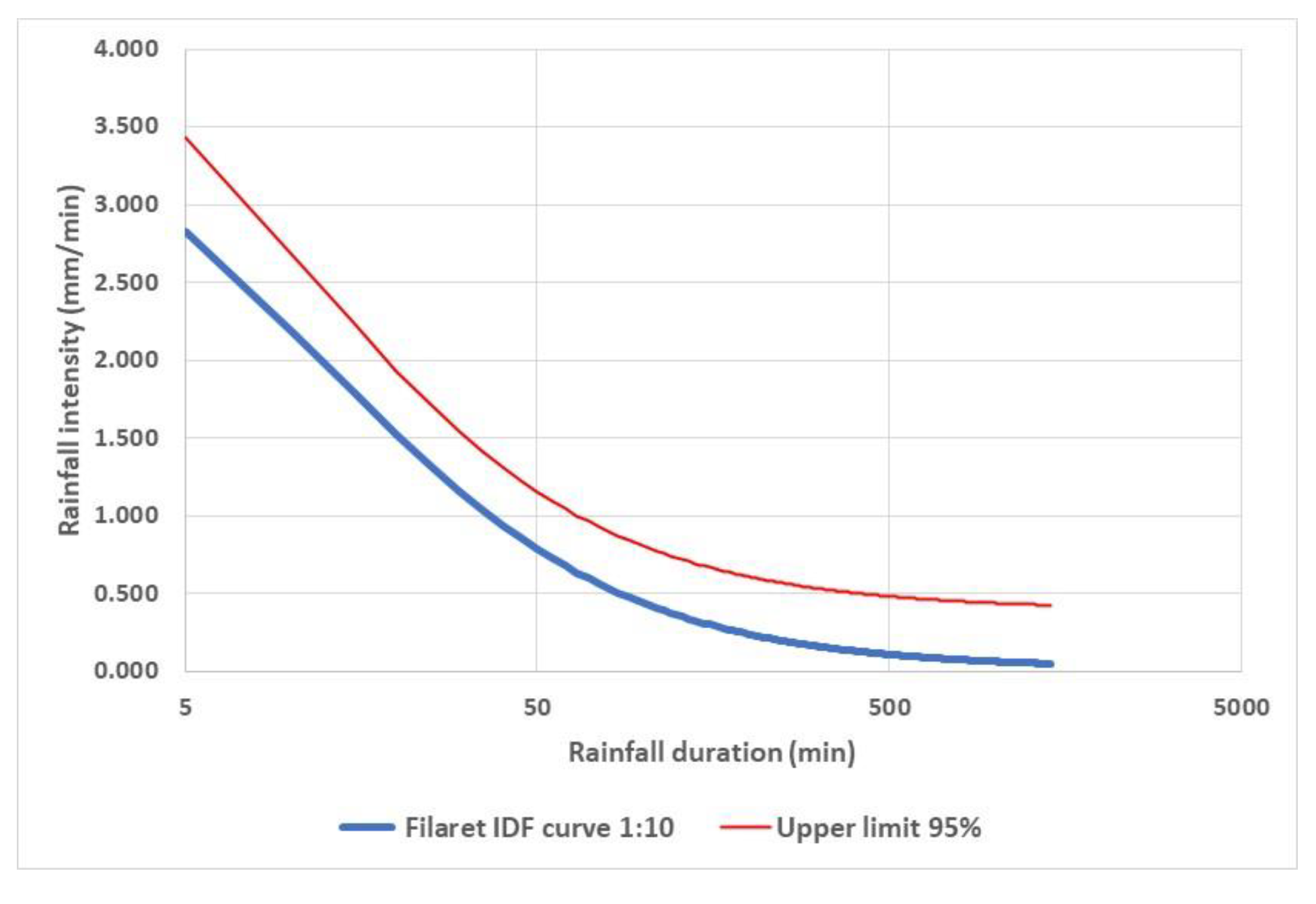

4.2. Variability Inside the Homogeneous Zones

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IDF | Intensity-Duration-Frequency curves |

| AFA | At-site frequency analysis |

| AFE | Annual frequency of exceedance |

| RFA | Regional frequency analysis |

| STAS | State standard (or state norms in Romania) |

| ANM | National Administration of Meteorology, Bucharest, Romania |

| HG | Government Decision, Romania |

| ASRO | National Romanian Standardization Organism |

| CT186 | Technical Committee “Water Supply and Sewerage” from ASRO |

References

- Chow, V.T. , Maidment, D.R., Mays, L.W. Applied Hydrology; McGraw-Hill: New York, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Maidment, D.R. Handbook of Hydrology; McGraw-Hill, New York, USA, 1993; pp. 18.50-18.52.

- Koutsoyiannis, D.; Kozonis, D.; Manetas, A. (1998). A mathematical framework for studying rainfall intensity-duration-frequency relationships. Journal of Hydrology. [CrossRef]

- Kite, G.W. Frequency and Risk Analysis in Hydrology; 4th Printing; Water Resources Publications: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 1988; pp. 4–26. [Google Scholar]

- Stedinger, J.R.; Vogel, R.M.; Foufoula-Georgiou, E. Frequency Analysis of Extreme Events. In Handbook of Hydrology; Maidment, D.R., Ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1993; p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Meylan, P.; Favre, A.C.; Musy, A. Hydrologie Fréquentielle - Une science predictive. Presses Polytechniques et Universitaires Romandes. EPFL. Lausanne. Switzerland, 2008; pp.

- Ben-Zvi, A. Rainfall intensity–duration–frequency relationships derived from large partial duration series. Journal of Hydrology 2009, 367, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, V.T. Handbook of Applied Hydrology; McGraw-Hill: New York, USA, 1964; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Yevjevich, V. Probability and Statistics in Hydrology; Water Resources Publications: Littleton, Colorado, USA, 1972; pp. 68–82. [Google Scholar]

- Cunnane, C. A particular comparison of annual maxima and partial duration series methods of flood frequency prediction. Journal of Hydrology.

- Cunnane, C. Unbiased and biased estimators of the distribution of maximum daily precipitation. Water Resources Research, 14.

- Cunnane, C. One-dimensional and multi-dimensional frequency analysis of floods. Hydrological Sciences Journal, 34.

- Cunnane, C. Statistical distributions for flood frequency analysis. 1989b. World Meteorological Organization. Operational Hydrology Report, /: 718. Secretariat of the World Meteorological Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, pp. 1-61. WMO e-Library, https, 25 September 3376; =1. [Google Scholar]

- Koutsoyiannis, D. , 2004a. Statistics of extremes and estimation of extreme rainfall: I. Theoretical investigation. 20 August; 04.

- Drobot, R.; Draghia, A.F.; Ciuiu, D.; Trandafir, R. Design Floods Considering the Epistemic Uncertainty (Appendix A). Water 2021, 13, 1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, H.; Rasmussen, P.F.; Rosbjerg, D. Comparison of annual maximum series and partial duration series methods for modeling extreme hydrologic events. 1. At-site modeling. Water Resources Research, 33.

- Madsen, H.; Pearson, C. P.; Rosbjerg, D. Comparison of annual maximum series and partial duration series methods for modeling extreme hydrologic events. 2. Regional modeling. Water Resources Research, 33.

- Martins, E.S.; Stedinger, J.R. Historical information in a generalized maximum likelihood framework with partial duration and annual maximum series. Water Resources Research, 2559; 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis Jr, D.S; Stedinger, J.R. Bayesian MCMC flood frequency analysis with historical information. Journal of Hydrology.

- England Jr, J.F.; Cohn, T.; Faber, B.; Stedinger, J.R.; Thomas Jr., W.O.; Veilleux, A.G.; Kiang, J.E.; Mason Jr., R.R. Guidelines for Determining Flood Flow Frequency Bulletin 17 C. Chapter 5 of Section B, Surface Water, Book 4, Hydrologic Analysis and Interpretation. Techniques and Methods 4–B5, Version 1.1, 19. U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia, pp. 5-18. 20 May.

- Madsen, H.; Mikkelsen, P. S. ; Rosbjerg, D; Harremoës, P. Regional estimation of rainfall intensity-duration-frequency curves using generalized least squares regression of partial duration series statistics. Water Resources Research, 1239; 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsoyiannis, D. , 2004b. Statistics of extremes and estimation of extreme rainfall: II. Empirical investigation of long rainfall records. Hydrological Sciences–Journal des Sciences Hydrologiques.

- Nhat, L.M.; Tachikawa, Y.; Takara, K. Establishment of Intensity-Duration-Frequency Curves for Precipitation in the Monsoon Area of Vietnam. Annals of Diss. Prev. Res. Inst. Kyoto Univ.

- Koutsoyiannis, D. On the appropriateness of the Gumbel distribution in modelling extreme rainfall. In Proceedings of the ESF LESC Exploratory Workshop, Bologna, Italy, 24-25 October 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, K.B.; Lai, S.H.; Faridah, O. RainIDF: automated derivation of rainfall intensity–duration–frequency relationship from annual maxima and partial duration series. Journal of Hydroinformatics 2013. IWA Publishing, 15.4, pp. 1224-1233. [CrossRef]

- Nhat, L.M.; Tachikawa, Y.; Sayama, T.; Takara, K. Derivation of Rainfall Intensity-Duration-Frequency Relationships for Short-Duration Rainfall from Daily Data. Proc. of International Symposium of Managing Water Supply for Growing Demand, Bangkok, Thailand, 16-b. IHP Technical Document in Hydrology. No. 6, pp. 89-96. 20 October.

- Takeleb, A.M.; Fajriani, Q.R.; Ximenes, M.A. Determination of Rainfall Intensity Formula and Itensity-Duration-Frequency (IDF) Curve at the Quelicai Administrative Post, Timor-Leste. Timor-Leste Journal of Engineering and Science, 3.

- Van de Vyver, H. Bayesian estimation of rainfall intensity–duration–frequency relationships. Journal of Hydrology, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, M.K.; Gupta, V. Identification of Homogeneous Rainfall Regimes in Northeast Region of India using Fuzzy Cluster Analysis, Water Resource Management 2014, 28, pp. 4491–4511 DOI 10.1007/s11269-014-0699-7.

- Kim, S.; Sung, K.; Shin, J.-Y.; Heo, J.-H. At-Site Versus Regional Frequency Analysis of Sub-Hourly Rainfall for Urban Hydrology Applications During Recent Extreme Events. Water 2025, 17, 2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deidda, R.; Hellies, M.; Langousis, A. A critical analysis of the shortcomings in spatial frequency analysis of rainfall extremes based on homogeneous regions and a comparison with a hierarchical boundaryless approach. Stochastic Environmental Research and Risk Assessment 2021, 35, pp. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minguez, R. ; S. Herrera, S. Spatial extreme model for rainfall depth: application to the estimation of IDF curves in the Basque country. Stochastic Environmental Research and Risk Assessment, 3117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://en.wikipedia. 28 September 2025.

- Stănescu, V.Al.; Drobot, R. Non-structural measures for flood management (in Romanian). Ed. HGA, Bucharest, Romania, 2002, pp. 80-86.

- EN 752:2017/pr.A1 - Drain and sewer systems outside buildings - Sewer system management. 2017.

- Schmitt, T. G.; Schilling, W.; Sasgrov, S.; & Nieschulz, K. P. Flood risk management for urban drainage systems by simulation and optimization. Proceedings of 9th International Conference on Urban Drainage, Portland, Oregon, USA, 8-. 13 September.

- Schmitt, T. G.; Thomas, M.; Ettrich, N. Analysis and modeling of flooding in urban drainage systems. Journal of Hydrology, 4. [CrossRef]

- NP 133-2022 Regulation on the design, execution and operation of water supply and sewerage systems of localities, vol. II, Sewerage Systems (In Romanian). Ministry of Development, Public Works and Administration. 2022. Bucharest, Romania.

- STAS 9470-73. Maximum rainfall. Intensity-Duration-Frequency (in Romanian). Romanian Institute of Standardization. 1973. Bucharest, Romania.

- Yang, S.; Wang, X.; Guo, J.; Chang, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Ju, S. Trend Analysis of Extreme Precipitation and Its Compound Events with Extreme Temperature Across China. Water 2025, 17, 2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsoyiannis, D.; Baloutsos, G. Analysis of a long record of annual maximum rainfall in Athens, Greece, and design rainfall inferences. Natural Hazards 2000, 22(1), 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, Y-M. ; Chu, H-J.; Pan, T-Y.; Yu, H-L. Investigating common trends of annual maximum rainfall during heavy rainfall events in southern Taiwan. Journal of hydrology 2011, 409, 3, pp. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugină, A.M. Alternative Hydraulic Modeling Method Based on Recurrent Neural Networks: From HEC-RAS to AI. Hydrology 2025, 12, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everitt, B.S.; Landau, S.; Leese, M.; Stahl, D. Cluster Analysis, 5th ed.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2011; pp. 1–330. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, A.K. Data Clustering—50 Years Beyond K-Means. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2010, 31(8), 651–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legendre, P.; Legendre, L. Numerical Ecology, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ester, M.; Kriegel, H.P.; Sander, J.; Xu, X.A. Density-Based Algorithm for Discovering Clusters in Large Spatial Databases with Noise. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD-96), Portland, OR, USA, CA, USA, 2–4 August 1996; AAAI Press: Menlo Park; pp. 226–231. [Google Scholar]

- Daszykowski, M.; Walczak, B. Clustering of Multivariate Data—A Survey. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2009, 96(2), 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Charrad, M.; Ghazzali, N.; Boiteau, V.; Niknafs, A. NbClust—An R Package for Determining the Relevant Number of Clusters in a Data Set. J. Stat. Softw. 2014, 61(6), 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig, C.; Meila, M.; Murtagh, F.; Rocci, R. (Eds.) . Handbook of Cluster Analysis; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Saxena, A.; Mittal, M.; Goyal, L.M. Comparative Analysis of Clustering Methods. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2015, 118(21), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, F. C. Generalized rainfall-duration-frequency relationships. J. Hydraul. Div., Am. Soc. Civ. Eng. 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Lakatos, M.; Szentes, O.; Cindric Kalin, K.; Nimac, I.; Kozjek, K.; Cheval, S.; Dumitrescu, A.; Irașoc, A.; Stepanek, P.; Farda, A.; et al. Analysis of Sub-Daily Precipitation for the PannEx Region. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, T.D.; Andrieu, H.; Hamel, P. Understanding, management and modelling of urban hydrology and its consequences for receiving waters: A state of the art. Advances in Water Resources, 51. [CrossRef]

- Neyman, J. Outline of a Theory of Statistical Estimation Based on the Classical Theory of Probability. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A. Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 1937. [CrossRef]

- STAS 9470-2005. Maximum rainfall. Intensity-Duration-Frequency (in Romanian). ASRO. 2025. Bucharest, Romania.

- Decision, No. 766/1997 for the approval of regulations on quality in construction (in Romanian). Government of Romania, 21 November.

|

Design storm frequency 1 (1 in “n ” years) |

Location |

Design flooding frequency (1 in “n ” years ) |

| 1:1 | Rural areas | 1:10 |

| 1:2 | Residential areas | 1:20 |

| City centers, industrial/commercial areas | ||

| 1:2 | - with flooding check | 1:30 |

| 1:5 | - without flooding check | - |

| 1:10 | Underground railway/ underpasses | 1:50 |

| Station | Station | NSE | Distance (km) |

| Arad | Turnu Măgurele 1 | 0.998964 | 387.3 |

| Lugoj | 0.997717 | 69.62 | |

| Timișoara | 0.997184 | 49.48 | |

| Fetești 1 | 0.996895 | 546.98 | |

| Bârlad 1 | 0.996293 | 488.40 | |

| Călărași 1 | 0.996179 | 517.82 | |

| Bârlad | Timișoara 1 | 0.997894 | 501.07 |

| Deva 1 | 0.99780 | 368.00 | |

| Fetești 1 | 0.997723 | 206.34 | |

| Lugoj 1 | 0.996971 | 450.42 | |

| Roman | 0.996583 | 93.51 | |

| Sibiu 1 | 0.996486 | 273.08 | |

| Blaj | Reșița | 0.996858 | 184.99 |

| Cernavoda 1 | 0.996398 | 382.33 | |

| Roman 1 | 0.996066 | 245.34 | |

| Moldova Veche | 0.995229 | 238.97 | |

| Călărași | 0.995084 | 346.32 | |

| Lugoj | Turnu Măgurele 1 | 0.998139 | 319.84 |

| Timișoara | 0.998116 | 51,61 | |

| Vaslui 1 | 0.993912 | 371,58 | |

| Târgu Mureș | 0.993226 | 225.84 | |

| Piatra Neamț 1 | 0.992969 | 370.17 | |

| Sibiu | 0.992005 | 176,41 |

| No. | Building importance category1 | Safety coefficients |

| 1 | Exceptional | 1.20 |

| 2 | Special | 1.10 |

| 3 | Common | 1.05 |

| 4 | Reduced importance | 1.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).