Submitted:

15 October 2025

Posted:

16 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Cell Cultures

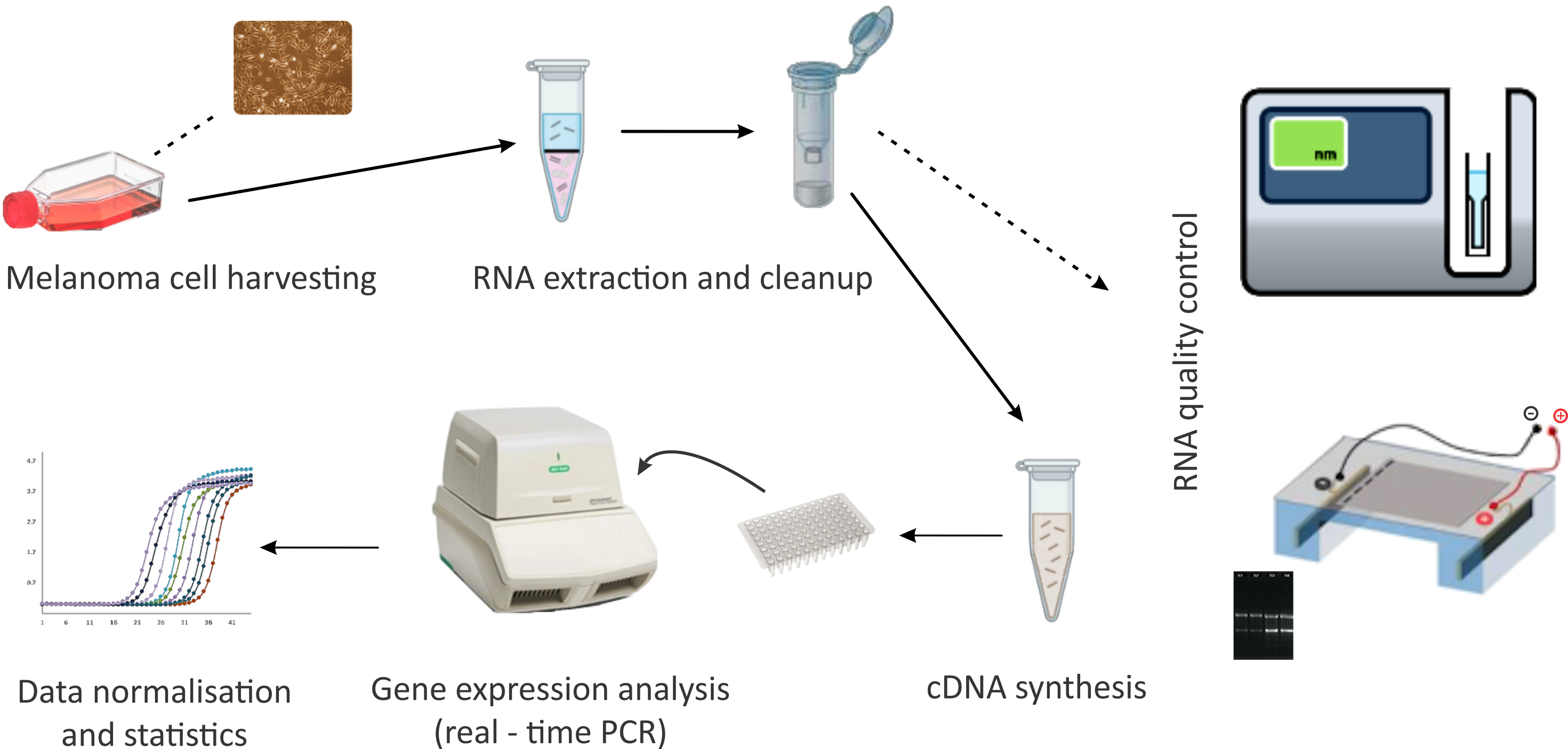

2.3. RNA Isolation and Real-Time PCR

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Yamaguchi, Y.; Brenner, M.; Hearing, V.J. The Regulation of Skin Pigmentation *. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 27557–27561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, M.; Hearing, V.J. The Protective Role of Melanin Against UV Damage in Human Skin†. Photochem. Photobiol. 2008, 84, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cichorek, M.; Wachulska, M.; Stasiewicz, A.; Tymińska, A. Review Paper<br>Skin Melanocytes: Biology and Development. Adv. Dermatol. Allergol. Dermatol. Alergol. 2013, 30, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borovanský, J.; Riley, P.A. Physiological and Pathological Functions of Melanosomes. In Melanins and Melanosomes. In Melanins and Melanosomes; Borovanský, J., Riley, P.A., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Weinheim, Germany, 2011; ISBN 978-3-527-32892-5. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.Y.; Kosmadaki, M.; Yaar, M.; Gilchrest, B.A. Cellular Mechanisms Regulating Human Melanogenesis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2009, 66, 1493–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae-Harboe, Y.-S.C.; Park, H.-Y. Tyrosinase: A Central Regulatory Protein for Cutaneous Pigmentation. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2012, 132, 2678–2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Videira, I.F. dos S.; Moura, D.F.L.; Magina, S. Mechanisms Regulating Melanogenesis*. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2013, 88, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Mello, S.; Finlay, G.; Baguley, B.; Askarian-Amiri, M. Signaling Pathways in Melanogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, S.; Wakamatsu, K. Chemistry of Mixed Melanogenesis—Pivotal Roles of Dopaquinone. Photochem. Photobiol. 2008, 84, 582–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, J.D.; Peles, D.; Wakamatsu, K.; Ito, S. Current Challenges in Understanding Melanogenesis: Bridging Chemistry, Biological Control, Morphology, and Function. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2009, 22, 563–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondo, T.; Hearing, V.J. Update on the Regulation of Mammalian Melanocyte Function and Skin Pigmentation. Expert Rev. Dermatol. 2011, 6, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buscà, R.; Ballotti, R. Cyclic AMP a Key Messenger in the Regulation of Skin Pigmentation. Pigment Cell Res. 2000, 13, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, H.; Moro, O. Involvement of Microphthalmia-Associated Transcription Factor (MITF) in Expression of Human Melanocortin-1 Receptor (MC1R). Life Sci. 2002, 71, 2171–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vachtenheim, J.; Borovanský, J. “Transcription Physiology” of Pigment Formation in Melanocytes: Central Role of MITF. Exp. Dermatol. 2010, 19, 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slominski, A.; Wortsman, J. Neuroendocrinology of the Skin1. Endocr. Rev. 2000, 21, 457–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Malek, Z.A.; Swope, V.B. Epidermal Melanocytes: Regulation of Their Survival, Proliferation, and Function in Human Skin. In Melanoma Development: Molecular Biology, Genetics and Clinical Application; Bosserhoff, A., Ed.; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2011; ISBN 978-3-7091-0371-5. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.-Y.; Wu, C.; Yonemoto, L.; Murphy-Smith, M.; Wu, H.; Stachur, C.M.; Gilchrest, B.A. MITF Mediates CAMP-Induced Protein Kinase C-β Expression in Human Melanocytes. Biochem. J. 2006, 395, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denning, M.F. Specifying Protein Kinase C Functions in Melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2012, 25, 466–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegner, M. All Purpose Sox: The Many Roles of Sox Proteins in Gene Expression. SOX Transcr. Factors 2010, 42, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubic, J.D.; Young, K.P.; Plummer, R.S.; Ludvik, A.E.; Lang, D. Pigmentation PAX-ways: The Role of Pax3 in Melanogenesis, Melanocyte Stem Cell Maintenance, and Disease. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2008, 21, 627–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solano, F. Melanins: Skin Pigments and Much More—Types, Structural Models, Biological Functions, and Formation Routes. New J. Sci. 2014, 2014, C. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, S.; Zhang, W.; Wakamatsu, K.; Ito, S.; Hearing, V.J.; Kraemer, K.H.; Brash, D.E. Melanin Acts as a Potent UVB Photosensitizer to Cause an Atypical Mode of Cell Death in Murine Skin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2004, 101, 15076–15081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariano, A.; Bigioni, I.; Scotto d’Abusco, A.; Baseggio Conrado, A.; Maina, S.; Francioso, A.; Mosca, L.; Fontana, M. Pheomelanin Effect on UVB Radiation-Induced Oxidation/Nitration of l-Tyrosine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 23, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasti, T.H.; Timares, L. MC1R, Eumelanin and Pheomelanin: Their Role in Determining the Susceptibility to Skin Cancer. Photochem. Photobiol. 2015, 91, 188–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, P.A. Melanogenesis and Melanoma. Pigment Cell Res. 2003, 16, 548–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanetti, R.; Prota, G.; Napolitano, A.; Martinez, C.; Sancho-Garnier, H.; Østerlind, A.; Sacerdote, C.; Rosso, S. Development of an Integrated Method of Skin Phenotype Measurement Using the Melanins. Melanoma Res. 2001, 11, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, A.M.; Lo, J.; Fisher, D.E. How Does Pheomelanin Synthesis Contribute to Melanomagenesis?: Two Distinct Mechanisms Could Explain the Carcinogenicity of Pheomelanin Synthesis. BioEssays 2013, 35, 672–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, M.K.; Sinha, P.; Clements, V.K.; Rodriguez, P.; Ostrand-Rosenberg, S. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells Inhibit T-Cell Activation by Depleting Cystine and Cysteine. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusmartsev, S.; Nefedova, Y.; Yoder, D.; Gabrilovich, D.I. Antigen-Specific Inhibition of CD8+ T Cell Response by Immature Myeloid Cells in Cancer Is Mediated by Reactive Oxygen Species. J. Immunol. 2004, 172, 989–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyle, J.L.; Haupt, H.M.; Stern, J.B.; Multhaupt, H.A.B. Tyrosinase Expression in Malignant Melanoma, Desmoplastic Melanoma, and Peripheral Nerve Tumors. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2002, 126, 816–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, G.L.; Scheer, W.D.; Levine, E.A. Detection of Tyrosinase MRNA from the Blood of Melanoma Patients. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 1996, 5, 293–296. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wakamatsu, K.; Fukushima, S.; Minagawa, A.; Omodaka, T.; Hida, T.; Hatta, N.; Takata, M.; Uhara, H.; Okuyama, R.; Ihn, H. Significance of 5-S-Cysteinyldopa as a Marker for Melanoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranadive, N.S.; Shirwadkar, S.; Persad, S.; Menon, I.A. Effects of Melanin-Induced Free Radicals on the Isolated Rat Peritoneal Mast Cells. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1986, 86, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

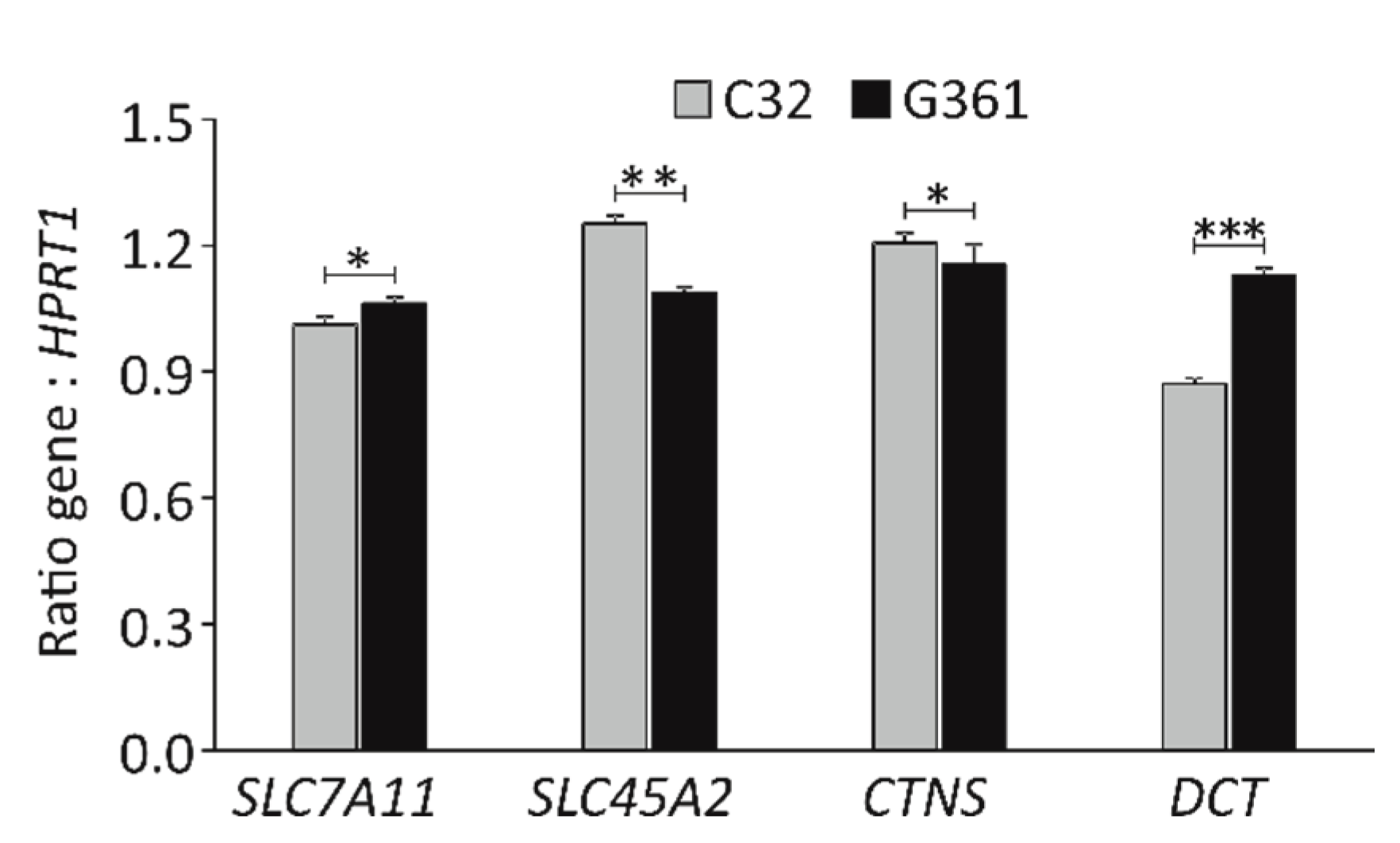

- Galván, I.; Inácio, Â.; Romero-Haro, A.A.; Alonso-Alvarez, C. Adaptive Downregulation of Pheomelanin-related Slc7a11 Gene Expression by Environmentally Induced Oxidative Stress. Mol Ecol 2017, 26, 849–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premi, S. Role of Melanin Chemiexcitation in Melanoma Progression and Drug Resistance. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premi, S.; Wallisch, S.; Mano, C.M.; Weiner, A.B.; Bacchiocchi, A.; Wakamatsu, K.; Bechara, E.J.H.; Halaban, R.; Douki, T.; Brash, D.E. Chemiexcitation of Melanin Derivatives Induces DNA Photoproducts Long after UV Exposure. Science 2015, 347, 842–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, T.; Hearing, V.J. Direct Interaction of Tyrosinase with Tyrp1 to Form Heterodimeric Complexes in Vivo. J. Cell Sci. 2007, 120, 4261–4268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slominski, R.M.; Sarna, T.; Płonka, P.M.; Raman, C.; Brożyna, A.A.; Slominski, A.T. Melanoma, Melanin, and Melanogenesis: The Yin and Yang Relationship. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 842496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyman, M.; Walsdorf, R.E.; Wix, S.N.; Gill, J.G. The Metabolism of Melanin Synthesis—From Melanocytes to Melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2024, 37, 438–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costin, G.-E.; Hearing, V.J. Human Skin Pigmentation: Melanocytes Modulate Skin Color in Response to Stress. FASEB J. 2007, 21, 976–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aberdam, E.; Bertolotto, C.; Sviderskaya, E.V.; Thillot, V. de; Hemesath, T.J.; Fisher, D.E.; Bennett, D.C.; Ortonne, J.-P.; Ballotti, R. Involvement of Microphthalmia in the Inhibition of Melanocyte Lineage Differentiation and of Melanogenesis by Agouti Signal Protein *. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 19560–19565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vachtenheim, J.; Novotna, H.; Ghanem, G. Transcriptional Repression of the Microphthalmia Gene in Melanoma Cells Correlates with the Unresponsiveness of Target Genes to Ectopic Microphthalmia-Associated Transcription Factor. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2001, 117, 1505–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harno, E.; Gali Ramamoorthy, T.; Coll, A.P.; White, A. POMC: The Physiological Power of Hormone Processing. Physiol. Rev. 2018, 98, 2381–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakamatsu, K.; Zippin, J.H.; Ito, S. Chemical and Biochemical Control of Skin Pigmentation with Special Emphasis on Mixed Melanogenesis. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2021, 34, 730–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galván, I.; Inácio, Â.; Dañino, M.; Corbí-Llopis, R.; Monserrat, M.T.; Bernabeu-Wittel, J. High SLC7A11 Expression in Normal Skin of Melanoma Patients. Cancer Epidemiol. 2019, 62, 101582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chintala, S.; Li, W.; Lamoreux, M.L.; Ito, S.; Wakamatsu, K.; Sviderskaya, E.V.; Bennett, D.C.; Park, Y.-M.; Gahl, W.A.; Huizing, M.; et al. Slc7a11 Gene Controls Production of Pheomelanin Pigment and Proliferation of Cultured Cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2005, 102, 10964–10969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiaverini, C.; Sillard, L.; Flori, E.; Ito, S.; Briganti, S.; Wakamatsu, K.; Fontas, E.; Berard, E.; Cailliez, M.; Cochat, P.; et al. Cystinosin Is a Melanosomal Protein That Regulates Melanin Synthesis. FASEB J. 2012, 26, 3779–3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppula, P.; Zhang, Y.; Zhuang, L.; Gan, B. Amino Acid Transporter SLC7A11/XCT at the Crossroads of Regulating Redox Homeostasis and Nutrient Dependency of Cancer. Cancer Commun. 2018, 38, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohbayashi, N.; Fukuda, M. Recent Advances in Understanding the Molecular Basis of Melanogenesis in Melanocytes. F1000Research 2020, 9, F1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ancans, J.; Tobin, D.J.; Hoogduijn, M.J.; Smit, N.P.; Wakamatsu, K.; Thody, A.J. Melanosomal PH Controls Rate of Melanogenesis, Eumelanin/Phaeomelanin Ratio and Melanosome Maturation in Melanocytes and Melanoma Cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2001, 268, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ota, K.; Zhou, D.; Zippin, J. 2321: Soluble Adenylyl Cyclase (SAC) Regulates Melanogenesis and Melanocyte Response to UVB. J. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2017, 1, 7–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, L.; Escobar, I.E.; Ho, T.; Lefkovith, A.J.; Latteri, E.; Haltaufderhyde, K.D.; Dennis, M.K.; Plowright, L.; Sviderskaya, E.V.; Bennett, D.C.; et al. SLC45A2 Protein Stability and Regulation of Melanosome PH Determine Melanocyte Pigmentation. Mol. Biol. Cell 2020, 31, 2687–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarrola-Villava, M.; Fernandez, L.P.; Alonso, S.; Boyano, M.D.; Peña-Chilet, M.; Pita, G.; Aviles, J.A.; Mayor, M.; Gomez-Fernandez, C.; Casado, B.; et al. A Customized Pigmentation SNP Array Identifies a Novel SNP Associated with Melanoma Predisposition in the SLC45A2 Gene. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e19271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Talukder, A.H.; Lim, S.A.; Kim, K.; Pan, K.; Melendez, B.; Bradley, S.D.; Jackson, K.R.; Khalili, J.S.; Wang, J.; et al. SLC45A2: A Melanoma Antigen with High Tumor Selectivity and Reduced Potential for Autoimmune Toxicity. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2017, 5, 618–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chi, W.; Tao, L.; Wang, G.; Deepak, R.N.V.K.; Sheng, L.; Chen, T.; Feng, Y.; Cao, X.; Cheng, L.; et al. Ablation of Proton/Glucose Exporter SLC45A2 Enhances Melanosomal Glycolysis to Inhibit Melanin Biosynthesis and Promote Melanoma Metastasis. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2022, 142, 2744–2755.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Fukunaga-Kalabis, M.; Li, L.; Herlyn, M. Developmental Pathways Activated in Melanocytes and Melanoma. Adv. Melanocyte Melanoma Biol. 2014, 563, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muinonen-Martin, A.J.; O’Shea, S.J.; Newton-Bishop, J. Amelanotic Melanoma. BMJ 2018, 360, k826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.-Z.; Zheng, H.-Y.; Li, J. Amelanotic Melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2019, 29, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzierżęga-Lęcznar, A.; Kurkiewicz, S.; Tam, I.; Marek, Ł.; Stępień, K. Pheomelanin Content of Cultured Human Melanocytes from Lightly and Darkly Pigmented Skin: A Pyrolysis-Gas Chromatography/Tandem Mass Spectrometry Study. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2017, 124, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, J.N.; Schmidt, H.; Steiniche, T.; Madsen, M. Identification of Robust Reference Genes for Studies of Gene Expression in FFPE Melanoma Samples and Melanoma Cell Lines. Melanoma Res. 2020, 30, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Osseiran, S.; Igras, V.; Nichols, A.J.; Roider, E.M.; Pruessner, J.; Tsao, H.; Fisher, D.E.; Evans, C.L. In Vivo Coherent Raman Imaging of the Melanomagenesis-Associated Pigment Pheomelanin. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 37986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neves, A.C. de O.; Zougagh, M.; Ríos, Á.; Tauler, R.; Wakamatsu, K.; Galván, I. Pheomelanin Subunit Non-Destructive Quantification by Raman Spectroscopy and Multivariate Curve Resolution-Alternating Least Squares (MCR-ALS). Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2021, 217, 104406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, M.; White, C. Amelanotic Malignant Melanoma. Semin Cutan Med Surg 1997, 16, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, W.L.; Patel, R.R.; Leonard, A.; Firoz, B.; Meehan, S.A. Amelanotic Melanoma: A Detailed Morphologic Analysis with Clinicopathologic Correlation of 75 Cases. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2012, 39, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.-N.; Wakamatsu, K.; Ito, S.; McCormick, S.A. Comparison of Eumelanin and Pheomelanin Content between Cultured Uveal Melanoma Cells and Normal Uveal Melanocytes. Melanoma Res. 2009, 19, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yang, J. Identification of Significant Genes with a Poor Prognosis in Skin Cutaneous Malignant Melanoma Based on a Bioinformatics Analysis. Ann. Transl. Med. 2022, 10, 448–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, S.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, B.; Yang, N.; Chen, S.; Shen, J.; Bao, G.; Wu, X. KIT Is Involved in Melanocyte Proliferation, Apoptosis and Melanogenesis in the Rex Rabbit. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Wang, H.; Li, C. Signal Pathways of Melanoma and Targeted Therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pu, Y.; Lei, M.; Chen, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Shao, X.; Liu, L.; Chen, J. Hey1 Promotes Migration and Invasion of Melanoma Cells via GRB2/PI3K/AKT Signaling Cascade. J. Cancer 2021, 12, 6979–6988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, G.P. Functional and Therapeutic Significance of Akt Deregulation in Malignant Melanoma. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2005, 24, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagliardi, P.A.; Puliafito, A.; Primo, L. PDK1: At the Crossroad of Cancer Signaling Pathways. AGC Kinases Cancer Metastasis Immunocheckpoint Regul. Drug Resist. 2018, 48, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Nguyen, V.; Clark, K.N.; Zahed, T.; Sharkas, S.; Filipp, F.V.; Boiko, A.D. Down-Regulation of FZD3 Receptor Suppresses Growth and Metastasis of Human Melanoma Independently of Canonical WNT Signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2019, 116, 4548–4557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.-H.; Fang, X.-Q.; Lim, W.-J.; Park, J.; Kang, T.-B.; Kim, J.H.; Lim, J.-H. Cinobufagin Suppresses Melanoma Cell Growth by Inhibiting LEF1. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ainger, S.A.; Yong, X.L.; Wong, S.S.; Skalamera, D.; Gabrielli, B.; Leonard, J.H.; Sturm, R.A. DCT Protects Human Melanocytic Cells from UVR and ROS Damage and Increases Cell Viability. Exp. Dermatol. 2014, 23, 916–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roider, E.; Lakatos, A.I.T.; McConnell, A.M.; Wang, P.; Mueller, A.; Kawakami, A.; Tsoi, J.; Szabolcs, B.L.; Ascsillán, A.A.; Suita, Y.; et al. MITF Regulates IDH1, NNT, and a Transcriptional Program Protecting Melanoma from Reactive Oxygen Species. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dankort, D.; Curley, D.P.; Cartlidge, R.A.; Nelson, B.; Karnezis, A.N.; Damsky Jr, W.E.; You, M.J.; DePinho, R.A.; McMahon, M.; Bosenberg, M. BrafV600E Cooperates with Pten Loss to Induce Metastatic Melanoma. Nat. Genet. 2009, 41, 544–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurette, P.; Coassolo, S.; Davidson, G.; Michel, I.; Gambi, G.; Yao, W.; Sohier, P.; Li, M.; Mengus, G.; Larue, L.; et al. Chromatin Remodellers Brg1 and Bptf Are Required for Normal Gene Expression and Progression of Oncogenic Braf-Driven Mouse Melanoma. Cell Death Differ. 2020, 27, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Yu, J.; Huang, F.; Zhu, Y.-Y.; Chen, D.-D.; Zhang, Z.-X.; Xie, Z.-C.; Liu, Z.-Y.; Hou, Q.; Xie, N.; et al. SLC7A11-Associated Ferroptosis in Acute Injury Diseases: Mechanisms and Strategies. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 27, 4386–4398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopkins, Z.H.; Carlisle, R.P.; Frost, Z.E.; Curtis, J.A.; Ferris, L.K.; Secrest, A.M. Risk Factors and Predictors of Survival Among Patients with Amelanotic Melanoma Compared to Melanotic Melanoma in the National Cancer Database. J. Clin. Aesthetic Dermatol. 2021, 14, 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Bin, B.-H.; Bhin, J.; Yang, S.H.; Shin, M.; Nam, Y.-J.; Choi, D.-H.; Shin, D.W.; Lee, A.-Y.; Hwang, D.; Cho, E.-G.; et al. Membrane-Associated Transporter Protein (MATP) Regulates Melanosomal PH and Influences Tyrosinase Activity. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0129273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, S.; Wakamatsu, K. Human Hair Melanins: What We Have Learned and Have Not Learned from Mouse Coat Color Pigmentation. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2011, 24, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

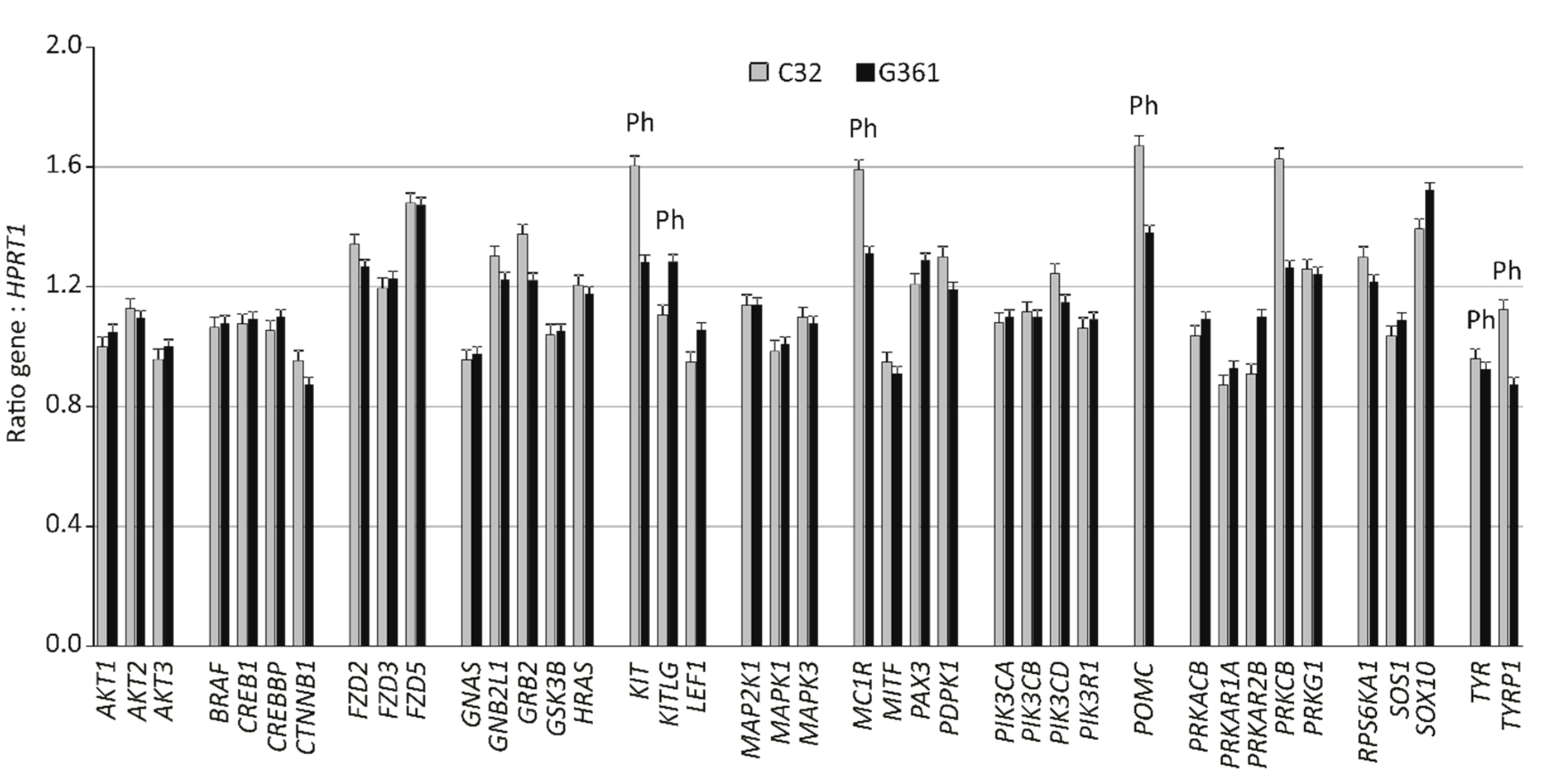

| Gene name | Gene symbol | UniGene ID | R (fold) | P-value | |

| Dopachrome tautomerase/tyrosinase related protein 2(*) | DCT/TYRP2 | Hs.307865 | 37 | 0.008 | |

| Protein kinase cAMP-dependent, type II regulatory subunit beta | PRKAR2B | Hs.433068 | 16 | 0.006 | |

| KIT ligand | KITLG | Hs.1048 | 11 | 0.005 | |

| Lymphoid enhancer binding factor 1 | LEF1 | Hs.555947 | 5 | 0.001 | |

| SRY-box transcription factor 10 | SOX10 | Hs.376984 | 4 | 0.001 | |

| Paired box 3 | PAX3 | Hs.42146 | 3 | 0.015 | |

| Protein kinase, cAMP-dependent type I regulatory subunit alpha | PRKAR1A | Hs.280342 | 2 | 0.008 | |

| Protein kinase, cAMP-dependent, catalytic, beta | PRKACB | Hs.487325. | 2 | 0.005 | |

| v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog 1 | AKT1 | Hs.525622 | 2 | 0.011 | |

| Son of sevenless homolog 1 | SOS1 | Hs.709893 | 2 | 0.002 | |

| v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog 3 | AKT3 | Hs.498292 | 2 | 0.009 | |

| CREB binding protein | CREBBP | Hs.459759 | 2 | 0.006 | |

| Solute carrier family 7 member 11(*) | SLC7A11 | Hs.390594 | 2 | 0.010 | |

| Gene name |

Gene symbol |

UniGene ID | R (fold) | P-value |

| Protein kinase C beta | PRKCB | Hs.460355 | 305 | 0.002 |

| KIT-proto-oncogene, receptor tyrosinase kinase | KIT | Hs.479754 | 165 | 0.012 |

| Proopiomelanocortin | POMC | Hs.1897 | 108 | 0.006 |

| Melanocortin 1 receptor | MC1R | Hs.513829 | 88 | 0.018 |

| Tyrosinase-related protein 1 | TYRP1 | Hs.270279 | 38 | 0.005 |

| Growth factor receptor-bound protein 2 | GRB2 | Hs.444356 | 12 | 0.012 |

| Solute carrier family 45 member 2(*) | SLC45A2 | Hs.278962 | 10 | 0.010 |

| 3-phosphoinositide dependent protein kinase 1 | PDPK1 | Hs.459691 | 6 | 0.009 |

| Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-biphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit delta | PIK3CD | Hs.518451 | 5 | 0.002 |

| Ribosomal protein S6 kinase A1 | RPS6KA1 | Hs.149957 | 4 | 0.010 |

| Frizzled class receptor 2 | FZD2 | Hs.142912 | 4 | 0.006 |

| Guanine nucleotide binding protein subunit-2-like 1 | GNB2L1 | Hs.5662 | 4 | 0.012 |

| Catenin (cadherin-associated protein) beta 1 | CTNNB1 | Hs.476018 | 3 | 0.005 |

| Melanocyte inducing transcription factor | MITF | Hs.166017 | 3 | 0.024 |

| Cystinosin, Lysosomal Cystine Transporter(*) | CTNS | Hs.187667 | 2 | 0.004 |

| HRas proto-oncogene, GTPase | HRAS | Hs.37003 | 2 | 0.005 |

| AKT serine/threonine kinase 2 | AKT2 | Hs.631535 | 2 | 0.001 |

| Frizzled class receptor 5 | FZD5 | Hs.17631 | 2 | 0.003 |

| Tyrosinase | TYR | Hs.503555 | 2 | 0.015 |

| Protein kinase cGMP-dependent type I | PRKG1 | Hs.407535 | 2 | 0.009 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).