1. Introduction

In the digital era, social media has profoundly reshaped how people discover, plan, and engage with outdoor recreation and travel experiences [

1]. Visual platforms such as TikTok, Instagram Reels, and YouTube Shorts have emerged as influential channels that not only shape destination image but also drive recreational behavior, particularly among younger audiences who are highly responsive to emotionally engaging and trend-driven content [

2,

3]. Beyond serving as information sources, social media platforms foster parasocial connections, or one-sided emotional bonds that audiences form with content creators or influencers, through which viewers develop a sense of familiarity, trust, and inspiration despite the absence of real interaction. These perceived relationships, combined with emotionally resonant and algorithmically amplified narratives, significantly enhance the persuasive power of social media. At the same time, broader global tourism trends reveal shifting expectations among travelers. There is a growing demand for authentic, experience-based, and sustainable forms of tourism, as visitors increasingly seek meaningful connections with nature, local culture, and communities rather than standardized mass tourism products [

4]. The rise of wellness and outdoor-oriented tourism reflects post-pandemic preferences for open spaces, health-focused activities, and nature immersion, while the experience economy drives visitors to prioritize creativity, participation, and storytelling over passive sightseeing. Moreover, sustainability and climate awareness have become central to travel decision-making, with destinations under pressure to balance tourism growth with ecological integrity and community well-being [

5].

As a result, social media has evolved into a behavioral force that not only amplifies these global tourism shifts but also shapes destination choices, recreational preferences, and visitor engagement, far beyond its traditional role as a marketing tool [

6,

7].

This transformation is especially relevant for nature-based tourism, which has witnessed significant global growth over the past decade [

8,

9]. In Thailand, the popularity of national parks has increased significantly, with the Department of National Park, Wildlife, and Plant Conservation (DNP) reporting over 20 million local and international visitors in 2022 alone (DNP, 2022). The Tourism Authority of Thailand [

11] also noted a marked increase in domestic interest in nature-oriented travel, particularly in the post-pandemic period, as travelers increasingly sought outdoor experiences that offered physical distancing, health benefits, and opportunities to reconnect with nature after prolonged periods of urban confinement and travel restrictions. However, this surge in visitation has not reflected a corresponding rise in environmental awareness. According to the National Park Office, most visitors are primarily motivated by recreation, family enjoyment, and the desire to escape daily routines. In contrast, activities that promote environmental learning, appreciation, or stewardship remain underdeveloped [

12,

13].

This situation reveals a critical communication gap. Although national parks possess significant potential to promote sustainable behavior, current messaging strategies often fail to align with visitors’ interests and media consumption patterns. Traditional approaches (such as static signage or passive interpretive materials) are increasingly ineffective in an era where travelers engage with dynamic video content and are influenced by viral trends. Without targeted, engaging, and platform-specific communication, the opportunity to influence tourist behavior toward sustainability risks being overlooked or disconnected from actual visitor experiences.

One promising strategy for enhancing visitor engagement in protected areas is the application of creative tourism, which emphasizes active participation, co-creation, and experiential learning [

14,

15]. Unlike passive forms of recreation, creative tourism encourages visitors to connect more deeply with natural and cultural landscapes through hands-on, immersive experiences [

16]. In the context of national parks, this approach can foster emotional attachment to place, encourage environmental stewardship, and differentiate parks from conventional tourism destinations [

17]. However, realizing these benefits requires more than offering creative activities. It also demands effective, targeted communication strategies that reflect how modern tourists consume information. In today’s digital landscape, social media platforms such as TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube have become central to shaping destination image and influencing tourist behavior, particularly among younger demographics who seek personalized, visually compelling, and emotionally engaging content [

18,

19].

This study responds to this challenge by examining the landscape of creative tourism activities currently offered in Thailand’s national parks, segmenting visitors based on their behavioral and media engagement patterns and developing tailored social media strategies for each group. The goal of this research is to reposition national parks not only as spaces of natural beauty and recreation but also as dynamic platforms for participatory learning and sustainable visitor engagement. By aligning creative tourism design with platform-specific communication strategies, this research contributes to more effective recreation planning and management in an era of rapidly evolving digital interaction.

Research Objective:

To examine the range of creative tourism activities offered in Thailand’s national parks.

To identify distinct visitor segments based on behavioral patterns, interests in creative activities, and media engagement preferences.

To develop segment-specific social media communication strategies aimed at fostering participatory learning and promoting sustainable visitor engagement.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Characteristics of Creative Tourism Activities in National Park

Creative tourism is a form of tourism that emphasizes active participation, personal expression, and meaningful interaction between visitors and the places they visit. As defined by Richards and Raymond [

14], it allows travelers to develop their creative potential by engaging in authentic, hands-on experiences that go beyond passive consumption. Unlike conventional mass tourism, which often centers on sightseeing, creative tourism invites visitors to co-create their experiences through activities such as crafts, culinary workshops, storytelling, and nature-based learning. This approach not only enhances visitor satisfaction but also fosters deeper emotional connections to place, encourages cultural and environmental appreciation, and supports community-based development [

20,

21].

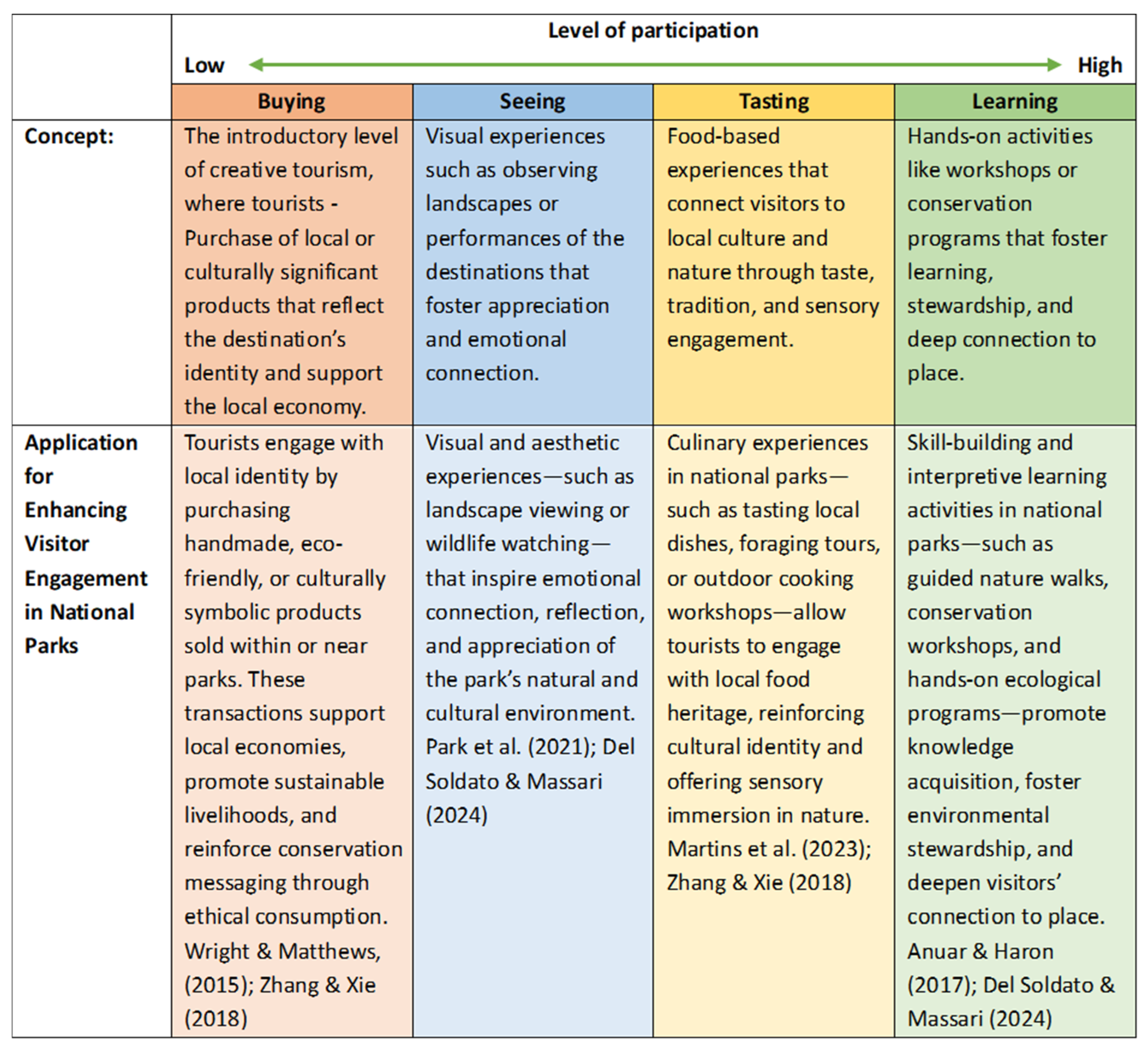

Building upon Richards’ [

14] typology of creative tourism, this study adopts his framework of four main forms of engagement: Buying, Seeing, Tasting, and Learning. These categories provide a structured framework for understanding the ways in which tourists interact with destinations through participatory and experience-driven activities (

Figure 1). While this framework has been widely applied in urban and cultural tourism contexts, it holds strong potential for nature-based tourism, particularly within national parks. Protected areas are increasingly seen not only as recreational destinations but as platforms for education, emotional connection, and sustainable development. Applying the creative tourism typology in these settings allows park managers to design experiences that are both meaningful for visitors and supportive of conservation goals. By appealing to diverse visitor motivations, whether sensory, aesthetic, intellectual, or ethical, creative tourism in national parks offers a powerful tool to enrich visitor experiences, enhance environmental awareness, and distinguish these destinations from conventional tourism offerings.

Buying dimension refers to the purchase of local products that reflect the cultural and ecological identity of a destination. In national parks, this often includes souvenirs, artisanal crafts, and natural goods, which serve as both tangible memories and support for the local economy [

23,

24]. Tourists are drawn to products that signal authenticity and environmental value, making creative retail experiences an important part of their journey.

Seeing includes visual and observational activities such as viewing landscapes, wildlife, and local art or performances. These experiences can inspire reflection and foster environmental awareness [

25], often contributing to a stronger sense of place attachment. Even passive activities like hiking or birdwatching may be reframed as creative when they evoke emotional responses or artistic appreciation [

26].

Tasting encompasses gastronomic activities, which are increasingly recognized as key drivers of tourist satisfaction and cultural connection [

27]. In natural areas, this may involve sampling seasonal produce, dining in nature-based settings, or learning traditional cooking recipes using local ingredients. There are experiences that integrate sensory pleasure with cultural storytelling.

Learning represents the most participatory form of creative tourism, involving workshops, conservation volunteering, or interpretive programs. Such activities not only enrich the visitor’s knowledge but also foster a sense of stewardship and connection to place [

28]. This aligns with tourists’ growing desire for meaning-driven travel experiences.

2.2. Segmentation of Creative Tourists

Creative tourism is a form of tourism that prioritizes active visitor participation, hands-on learning, and meaningful cultural or environmental engagement, moving beyond passive sightseeing to foster deeper, more personal experiences. Scholars have developed various typologies to classify creative tourists based on motivations, values, and levels of engagement. For example, Tan, Luh, and Kung [

29] identified five profiles, including novelty-seekers and environmentally conscious learners, while [

30] grouped tourists into clusters such as “Novelty-Seekers,” “Knowledge and Skills Learners,” and “Leisure Creative-Seekers,” each with distinct experience expectations. In an urban context, [

31] identified creative tourists in East London as trendsetters and cultural browsers who valued authenticity and atmosphere. However, these studies primarily focus on urban or cultural settings, and creative tourism in natural environments (particularly protected areas) remains significantly underexplored in literature. This research gap is noteworthy given the potential of nature-based destinations to apply creative tourism principles in designing novel, participatory experiences that foster sensory, emotional, and educational engagement with both nature and local culture.

Recent literature highlights the value of activity-based segmentation, which classifies tourists according to the types of experiences they seek (what they want to see, learn, taste, or do), offering stronger behavioral insights and practical applications than traditional demographic or motivational segmentation [

32,

33,

34]. Unlike abstract motivations or static demographics, activity-based segmentation is grounded in observable behaviors, making it highly relevant for experience design and product development. For example, Stemmer et al. [

34] demonstrated that tourists’ specialization in activities such as hiking or birdwatching influenced their preferences for specific tourism products, enabling more tailored and meaningful experiences. Similarly, [

30] found that different creative activity clusters required varying patterns, levels of depth, and facilitation approaches.

This segmentation approach also enhances communication and marketing strategies, particularly in digital environments. Pesonen and Tuohino [

35] observed that rural wellness tourists with different activity preferences exhibited distinct patterns in how they searched for and engaged with online content. Moreover, Pesonen [

32] showed that activity-based segments were more effective than motivational ones in targeting digital promotions, making them a valuable tool for platform-specific media planning.

This study responds to the key research gap by applying activity-based segmentation to creative tourists in national parks which remains underrepresented in the literature. It further links each segment to appropriate creative experiences and tailored digital communication strategies, contributing to both personalized visitor’s experience design and strategic outreach in nature-based tourism, especially in protected areas.

2.3. Typology of Social Media Content and Media Type

The role of content marketing in shaping tourist behavior has been widely explored across various tourism contexts [

36,

37]. However, there is limited consensus on how to categorize the different types of social media content in a way that reflects their distinct functions. To address this gap, recent tourism communication and destination branding literature has proposed multidimensional frameworks for classifying social media content. Building on these approaches, this study introduces a four-part typology tailored to protected area contexts: conservation education, scenic media, promotional information, and park mission [

38,

39]

Each content type engages audiences differently, as explained by the Elaboration Likelihood Model [

40]. Conservation education, such as scientific or interpretive content, aligns with the central route of persuasion, requiring cognitive engagement and supporting environmental learning [

41,

42]. Scenic media, including nature photography and wildlife videos, appeals to the peripheral route through visual and emotional resonance. Promotional content, like event updates, can activate both routes depending on clarity and perceived usefulness. Park mission content, such as ranger profiles or behind-the-scenes storytelling, fosters trust and reinforces long-term conservation attitudes [

43].

Applied to national parks, this typology reveals how social media can support both marketing and educational goals. Scenic and promotional media may be most effective in attracting attention and motivating visits, particularly during pre-trip planning. Meanwhile, conservation and mission-driven content can deepen post-visit reflection, foster place attachment, and promote pro-environmental behaviors. Despite growing use of visual storytelling [

18] and interpretive education [

44], few studies assess how content types influence behavior in protected areas. By exploring this relationship, the current study offers strategic insights for aligning digital communication with sustainable tourism goals in national parks.

2.4. Typology of Media Type

Media format plays a pivotal role in shaping message effectiveness and influencing tourist behavior. Different formats (such as photographs, text, short-form videos, long-form videos, and livestreams) engage audiences through varying psychological mechanisms. For example, scenic photographs shared on social media have been shown to significantly increase national park visitation by leveraging visual appeal and social proof, such as likes or shares [

18]. Conversely, text-based content like reviews or educational posts fosters cognitive trust and supports thoughtful decision-making, particularly among information-seeking audiences [

45].

Short-form videos, popular on platforms like TikTok and Instagram Reels, enhance emotional engagement and encourage parasocial interactions, especially among younger users who respond well to peripheral cues [

46]. Their perceived authenticity and entertainment value have been linked to increased travel intention and content sharing [

47]. Long-form videos, by contrast, offer narrative richness and are more suitable for conveying destination identity or complex themes. While livestreaming remains underutilized in national park contexts, studies in virtual tourism and hospitality suggest it can create a real-time sense of presence and stimulate affective responses [

48].

This study examines how different media formats influence visitor engagement and decision-making related to national park experiences. By analyzing media preferences across visitor segments, the findings aim to guide the development of tailored communication strategies. These insights support the use of format-specific messaging to promote creative and sustainable tourism, encouraging deeper engagement and responsible visitation in protected areas.

3. Materials and Methods

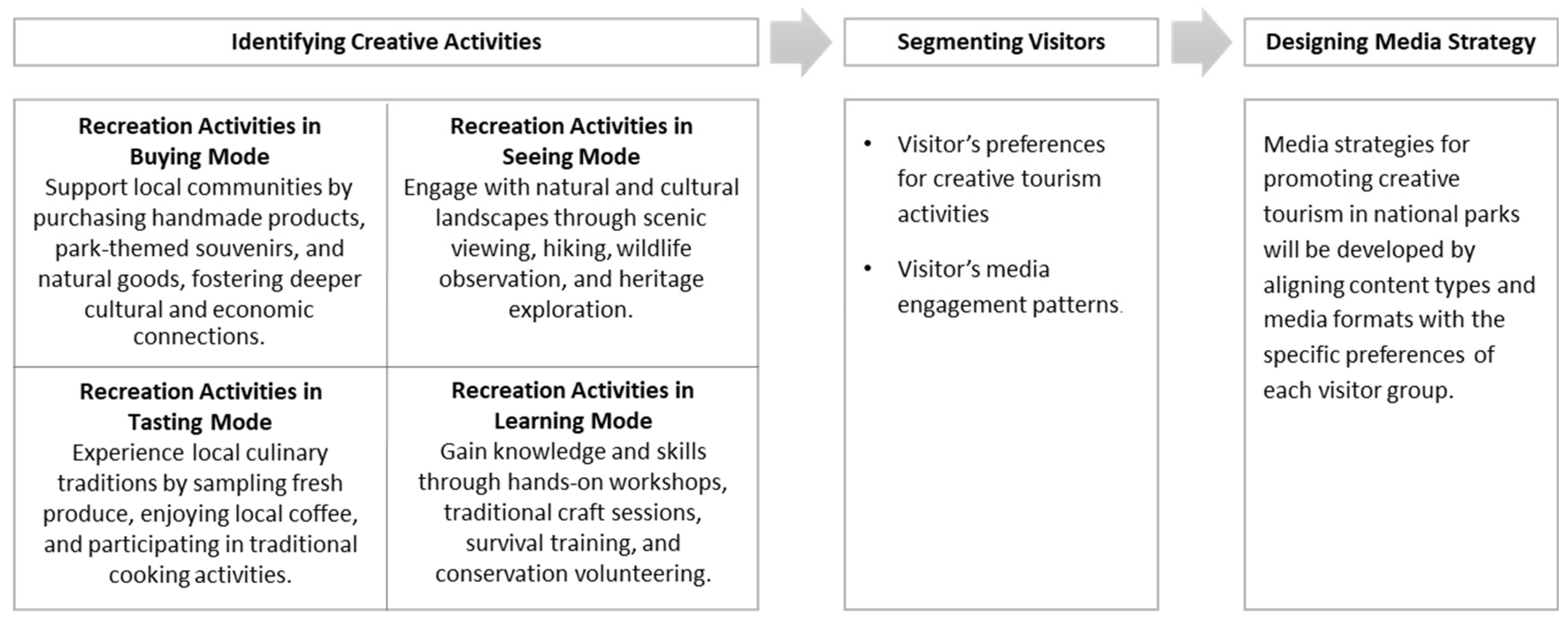

3.1. Research Framework

The research framework consists of three main parts aligned with the study’s objectives. Part 1, Creative Tourism Activity Analysis, outlines a sequential process that begins with the identification and categorization of creative tourism activities within Thailand’s national parks, encompassing both terrestrial and marine sites. These activities are analyzed and grouped into key thematic dimensions through exploratory factor analysis, providing a structured understanding of the creative tourism landscape. In this study, creative tourism activities are defined as participatory, experience-based engagements that involve learning, cultural exchange, and personal expression within natural settings

The second part: Visitor Segmentation. This part focuses on clustering visitors based on their preferences for creative tourism activities and their media engagement patterns. The segmentation process reveals distinct visitor profiles that reflect varying levels of interest, motivation, and digital behavior in the context of national park experiences. Understanding these profiles allows for a more nuanced approach to communication and service design.

The third part: Strategic Social Media Communication. The final part involves developing targeted social media strategies for each visitor segment. By aligning content types and media formats with the specific preferences of each group, the framework supports the creation of effective communication approaches that foster participatory learning and promote sustainable engagement. These strategies provide the foundation for actionable recommendations to enhance creative tourism experiences and improve the management of national parks in an increasingly digital environment.

3.2. Data Collection

3.2.1. Part 1: Identification of Creative Tourism Activities in National Parks

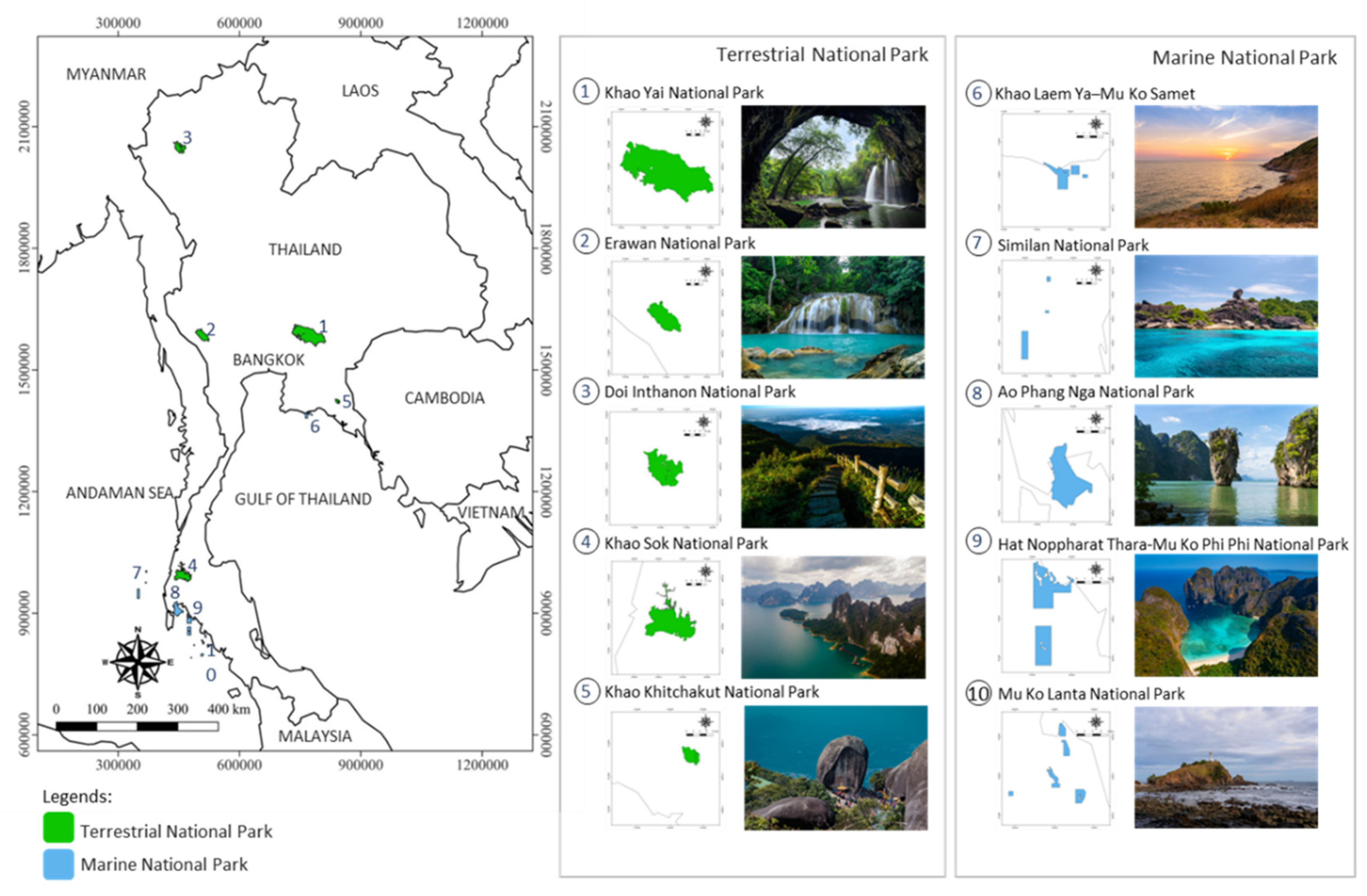

This part of the study aimed to identify creative tourism activities offered within Thailand’s national parks using a two-phase approach. In the first phase, secondary data were reviewed from a range of sources, including official national park websites, social media platforms (e.g., Facebook), and previous academic studies related to creative tourism in Thailand. These exploratory reviews provided contextual insights that informed the development of a preliminary inventory of creative tourism activities and contributed to the formulation of activity-based questionnaire items. The selection of national parks was guided by their high popularity among both domestic and international tourists. Ten national parks were chosen, comprising five terrestrial parks (Khao Yai, Erawan, Doi Inthanon, Khao Sok, and Khao Khitchakut) and five marine parks (Khao Laem Ya, Hat Noppharat Thara, Mu Ko Lanta, Mu Ko Similan, and Ao Phang Nga) [

10] (

Figure 3). Field visits to these sites allowed for direct observation and systematic documentation of creative tourism practices, ensuring contextual relevance, empirical validity, and practical applicability of the identified activities. The field survey was conducted between January and November 2024, capturing seasonal variations.

3.2.2. Part 2: Visitor Segmentation

Research Tools: This study applied a structured questionnaire as the primary data collection instrument. The questionnaire comprised four sections. The first two sections gathered demographic data and trip characteristics to describe the respondent profile and travel behavior. The third section focused on media influence, assessing how different media formats (e.g., photos, text, videos, short videos, and live streaming) and content types (e.g., conservation education, scenic imagery) impacted travel decisions. Respondents evaluated media types using a five-point Likert scale and identified relevant content themes.

The fourth section examined preferences for creative tourism activities in national parks. Respondents were asked to rate 20 activity items, identified from the findings in Part 1, using a five-point Likert scale. Content validity of the questionnaire was reviewed by three experts using the Index of Item-Objective Congruence (IOC), with revisions made according to their recommendations. A pilot study involving 30 participants from the target population was conducted to refine the instrument. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was determined to be 0.89, indicating a notably high level of reliability for the questionnaire. Additionally, the questionnaire received approval from the Institutional Review Board.

Sample Size and Sampling Method: Three national parks were selected for the questionnaire survey, drawn from the ten sites identified in the previous phase. According to the DNP [

10], Thailand’s designated national park system comprising 109 terrestrial and 24 marine parks. To reflect the proportional distribution of the sample included two terrestrial national parks (Erawan and Doi Inthanon) and one marine national park (Mu Ko Similan). Participants were selected using a systematic sampling method with every third group of visitors invited to participate. Respondents were approached after completing their visit to ensure they were familiar with the available activities and to minimize response bias based on limited or incomplete experiences. To enhance the representativeness of the sample, the distribution of respondents between terrestrial and marine parks was aligned with the five-year average visitor statistics from the ten highest-performing national parks. Based on these data, approximately 54.5% of the sample was drawn from terrestrial parks (n = 618), and 45.5% from the marine park (n = 515). The minimum required sample size was calculated using Yamane’s formula, applying a 95% confidence level and a 5% margin of error. Using the combined annual visitor population of the three selected parks in 2022 (N = 2,020,346), the minimum required sample size was estimated at approximately 400 respondents. The final sample size of 1,133 exceeds this threshold, ensuring strong statistical reliability. Visitor survey was conducted between January and June, 2024. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the DNP under the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment.

3.3. Data Analysis

3.3.1. Part 1: Identification of Creative Tourism Activities in National Parks

The data analysis for this phase involved qualitative synthesis and thematic classification. First, content from secondary sources was reviewed to identify recurring patterns, descriptions, and examples of creative tourism activities. These data were coded and organized to develop an initial inventory of activities aligned with the definition of creative tourism, emphasizing participation, cultural engagement, and learning. In the second phase, field observations from ten selected national parks were used to validate and refine this inventory. Observational data were recorded using structured field notes, photographs, and informal interviews with park staff or local stakeholders. The collected data were compared against the initial list to confirm existing activities, identify new or unlisted practices, and eliminate those no longer offered or irrelevant to the study context. To categorize creative tourism activities, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted to identify the underlying dimensions based on respondents’ interests. Visitors rated their interest in a list of selected recreational activities using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not interested, 5 = very interested). The list of activities was developed through earlier qualitative phases and grounded in Richards’ [

22] creative tourism framework. Although the four-category framework (Seeing, Learning, Tasting, Buying) was conceptually informed by prior literature, EFA was used to empirically examine the dimensional structure of tourist interest data. The extracted factors from EFA were then used to segment tourists through cluster analysis, supporting further interpretation of activity preferences and behavior patterns.

3.3.2. Part 2: Visitor Segmentation

To segment visitors based on their creative tourism preferences in Thailand’s national parks, a multi-step analytical approach was applied. This process included descriptive analysis, EFA, and cluster analysis, along with supporting inferential statistical tests (

Table 1).

Descriptive Analysis: Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the demographic and trip characteristics of the respondents. This included variables such as age, gender, education level, travel group type, and purpose of visit. These data provided a general profile of national park visitors and served as a contextual foundation for the segmentation process.

Cluster Formation: Using respondents’ raw mean scores from the three groups of factors including 1) level of interest in creative tourism activities, 2) social media use patterns, and 3) tourism characteristics, cluster analysis was applied to group individuals by their dominant interests. Each respondent was assigned to a cluster corresponding to the factor with the highest mean score. A group of clusters was created for respondents with equally high scores across multiple factors, representing a diverse interest profile.

Comparative and Inferential Analysis: To compare segments, mean scores across media format preferences and content influence were analyzed. Media format influence was rated using a 5-point Likert scale, while content influence was measured with binary (Yes/No) responses. Chi-square tests were used to assess statistical differences in demographic and trip-related variables across clusters. Where significant associations were found, post-hoc comparisons were conducted. All tests were performed at a 95% confidence level (p < 0.05), with confidence intervals reported as appropriate.

4. Results

4.1. Identification and Factor Analysis of Creative Tourism Activities

4.1.1. Identification Process and Activity Selection

A comprehensive review of 133 national parks in Thailand, including 130 terrestrial and 26 marine parks, combined with findings from field observations, identified a total of 25 unique recreational activities. This diversification of activities reflects the ecological and functional diversity of Thailand’s protected areas. The 23 activities were reported in terrestrial national parks. The most frequently observed activities in terrestrial parks included 1) nature study along nature trail (100.00%), 2) camping (87.69%), 3) enjoying the scenic beauty of a waterfall (80.77%), 4) exploring native plant species in the park (72.31%), 5) bird watching (70.77%) and 6) observing butterflies (70.77%). In marine national parks, 21 recreational activities were recorded. The overall pattern of activity offerings was largely consistent with those observed in terrestrial parks, though with slight variations in emphasis due to the coastal and marine context. The most frequently observed activities included 1) nature study along nature trail (100.00%), 2) exploring native plant species in the park (96.15%), 3) bird watching (88.46%), 4) observing butterflies (88.46%), 5) camping (61.54%), and 6) snorkeling (65.22%). These findings indicate a strong overlap in core nature-based activities offered across both park types, with additional water-based recreation (such as snorkeling) playing a more prominent role in marine parks. The consistency of activities such as nature study, flora observation, and wildlife watching emphasizes their foundational role in passive outdoor recreation and environmental interpretation within Thailand’s protected area system.

To ensure alignment with the principles of creative tourism, a refinement process was conducted to evaluate 27 identified outdoor recreation activities. Creative tourism emphasizes active participation, experiential learning, cultural exchange, and the co-creation of value between visitors and host communities. Based on this framework, five activities, including rafting, bicycling, trail running, windsurfing, and scuba diving, were excluded from further analysis due to their emphasis on physical challenge, adventure-oriented experiences, passive entertainment, or limited cultural and educational engagement The remaining 20 activities demonstrated strong potential to foster experiential learning, cultural interaction, and meaningful visitor engagement within protected areas (

Table 2). These activities were classified into four thematic categories, adapted from Richards’ (2011) creative tourism framework: (1) Buying Mode – Supporting local communities through the purchase of handmade products, park-themed souvenirs, and natural goods, thereby fostering deeper cultural and economic connections. (2) Seeing Mode – Engaging with natural and cultural landscapes through scenic viewing, hiking, wildlife observation, and heritage site exploration. (3) Tasting Mode – Experiencing local culinary traditions by sampling fresh produce, enjoying locally brewed coffee, and participating in traditional cooking practices. (4) Learning Mode – Acquiring knowledge and skills through hands-on workshops, traditional craft sessions, survival training, and conservation volunteering.

These 20 activities were retained for EFA to identify the underlying dimensions of creative tourism in national park contexts.

4.1.2. Factor Analysis of Creative Tourism Activities

An EFA was conducted to examine the underlying dimensions of tourists’ interest in creative tourism activities. Participants rated their level of interest in each of the 20 activities using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not interested, 5 = very interested). The EFA revealed meaningful shifts in how items are clustered, underscoring the value of exploratory methods in identifying data-driven patterns. The resulting four dimensions served as the empirical foundation for subsequent cluster analysis, aimed at segmenting tourists based on their creative tourism preferences (

Table 3). The extracted dimensions are as follows:

Group 1: Nature-based learning (α = 0.819; Eigenvalue = 10.51; 52.57% variance): This dimension includes six items related to workshops, survival skills training, birdwatching, and conservation volunteering. It reflects tourists’ interest in participatory, educational, and skill-building experiences in natural settings.

Group 2: Scenic immersion (α = 0.827; 8.06% variance): Comprising five items, this dimension emphasizes aesthetic and emotionally resonant experiences such as hiking, viewing landscapes, and visiting cultural or historical sites, highlighting a preference for reflective and scenery-based recreation.

Group 3: Community participation (α = 0.845; 7.13% variance): This factor relates to engagement with local economies, including shopping for and purchasing locally made goods. It reflects both economic support and symbolic interaction with host communities.

Group 4: Culinary activities (α = 0.803; 4.95% variance): This dimension captures interest in food-related experiences, including tasting local cuisine, enjoying regional coffee, and participating in traditional cooking practices, indicating a preference for gastronomic and cultural immersion.

The findings from the EFA reveal four distinct dimensions of tourist interest in creative tourism activities within Thailand’s national parks: Nature-based learning, Scenic immersion, Community participation, and Culinary activities. These dimensions offer valuable insights into the evolving preferences of park visitors and reflect a broader shift from passive sightseeing to more interactive, experience-driven forms of recreation. The results also illustrate the diversification of visitor motivations along the active–passive spectrum. The extracted dimensions range from active engagement (e.g., workshops, volunteering, cooking) to passive or reflective recreation (e.g., landscape viewing, cultural site visits), supporting existing research that suggests modern outdoor recreation increasingly incorporates learning, cultural discovery, and personal growth, rather than being solely focused on physical challenge or escapism [

49]. The coexistence of both action-oriented and contemplative experiences indicates that national parks support a wide range of visitor expectations. This is an important consideration for future programming, interpretation, and infrastructure development.

4.2. Visitor Segmentation

4.2.1. Demographic Profiles of Respondents

Demographic Profiles: According to the 1,133 survey respondents, the sample was predominantly female (72.69%), followed by male (22.33%) and individuals identifying as LGBTQ+ (4.98%). A majority of respondents (55.25%) were classified as Generation Z (born approximately 1997–2012), with Generation Y (Millennials) accounting for 37.86%. In terms of regional background, most respondents (75.55%) were from non-local areas, indicating that the sample largely comprised domestic tourists traveling from outside the selected national parks. Regarding education background, 66.46% held at least a bachelor’s degree, while 5.36% had qualifications above that level. Income data showed that 64.78% earned below the national average, 24.45% were at the average, and 10.8% earned above it, reflecting a broad representation of middle- to lower-income visitors.

Trip Characteristics: The primary motivation for travel was relaxation (82.32%), followed by visiting new places (47.68%) and spending time with family (40.46%). Popular activities included photography (75.60%) and sightseeing (68.03%). Most respondents traveled with friends (48.90%) or family (43.95%), reflecting a preference for shared travel experiences. A majority were first-time visitors (61.3%). In terms of trip duration, the most common were 1-day trips (31.51%), followed by 3 days/2 nights (27.27%) and 2 days/1 night (23.83%), indicating a tendency toward short to medium-length visits. Travel decisions were most influenced by recommendations from friends (51.37%) and online influencers (40.60%), while traditional sources such as travel agents and offline media played a minimal role, highlighting the increasing impact of digital platforms on travel behavior.

Media Influence: The results indicate that visual and audiovisual formats had a stronger influence on national park travel decisions than text-based content (x̄ = 3.02, SD = 1.14). Formats with highest influence include photos (x̄ = 4.06, SD = 0.90), streaming content (x̄ = 4.01, SD = 0.87), and short videos (x̄ = 3.96, SD = 0.92). This highlights the persuasive impact of visually rich and emotionally engaging media, underscoring the role of visual storytelling in tourism communication. Regarding content types, scenic media emerged as the most influential, with 80.14% of respondents reporting it affected their decision to visit parks. Educational content, such as tutorials and cultural information, followed at 56.13%. In contrast, promotional materials (37.42%) and park mission messaging (30.19%) were seen as less impactful. These findings suggest that tourists are more receptive to engaging, visually driven content than to formal or institutional messaging.

Preferences for Creative Tourism Activities: Based on the 20 selected activities, watching the sunrise and sunset at scenic viewpoints received the highest average preference score (x̄ = 4.13, on a 5-point scale), followed by hiking to panoramic viewpoints within national parks (x̄ = 4.02, SD = 0.893) and enjoying scenic and unique landscapes (x̄ = 4.00, SD = 0.907). When analyzed by category, visitors expressed the greatest interest in scenic immersion (x̄ = 3.84, SD = 0.735), followed by culinary-based activities (x̄ = 3.88, SD = 0.788), nature-based learning and conservation engagement (x̄ = 3.70, SD = 0.784), and community participation (x̄ = 3.55, SD = 0.730). These results suggest a strong preference for immersive experiences in natural settings, complemented by interest in cultural and participatory activities related to food and learning.

4.2.2. Visitor Segmentation and Behavioral Profiles

Clustering Visitors Based on Creative Tourism Preferences: A cluster analysis was conducted using standardized scores derived from the four creative tourism activity groups identified through the EFA. The analysis categorized respondents into five distinct visitor clusters based on their patterns of interest in creative tourism experiences within national parks (

Table 4). These clusters reflect diverse motivations and preferences for engaging in outdoor recreational activities. The five clusters are described as follows:

Cluster 1: Local advocates (6.18%): Representing the smallest segment, this group exhibited the highest interest in community participation (x̄ = 3.96), particularly activities supporting local products and handicrafts. Their moderate interest in other activity types suggests a focused preference for community-centered tourism experiences.

Cluster 2: Nature explorers (25.50%): This group showed a strong preference for scenic immersion (x̄ = 4.28), including hiking, wildlife viewing, and photography. Their relatively lower interest in community or food-based activities highlights a nature-oriented tourism profile focused on outdoor recreation.

Cluster 3: Food enthusiasts (20.48%): This cluster demonstrated the highest interest in culinary-based activities (x̄ = 4.31), such as local cuisine, cooking workshops, and tasting regional specialties. Their secondary interests in nature and community activities reflect a tourism preference centered on gastronomy.

Cluster 4: Nature-Based Learners (7.59%): A smaller segment, these visitors prioritized nature-based learning (x̄ = 4.00), showing a strong inclination toward educational and skill-building activities like survival training, conservation workshops, and birdwatching. Their interest reflects a deeper engagement with environmental learning.

Cluster 5: Diverse enthusiasts (40.25%): As the largest segment, this group expressed consistently high interest across all four activity types, particularly in scenic immersion (x̄ = 4.04) and culinary activities (x̄ = 4.03). This broad enthusiasm suggests a well-rounded tourist profile that is highly receptive to diverse creative tourism offerings within national parks.

Additionally, statistical testing confirmed significant differences in creative tourism interests across the five clusters. These findings express the heterogeneity of visitor preferences and highlight the opportunity for national parks to develop targeted programs and interpretive strategies. By recognizing the unique interests of each cluster, national parks can design more inclusive, engaging, and sustainable tourism experiences that enhance visitor satisfaction while supporting conservation and local community goals.

The characteristic of visitors in each cluster: Based on visitors’ preferences for creative tourism activities combined with their behavioral profiles,

Table 5 presents an in-depth profile of five visitor clusters identified through their creative tourism preferences, preferred media formats, and trip characteristics.

The results reveal distinct patterns in visitor characteristics, creative tourism interests, and media preferences across the five identified clusters. In terms of creative tourism interests, each group exhibited unique preferences. Local advocates focused strongly on community-based activities, such as supporting local products and crafts. Nature explorers prioritized outdoor recreation and scenic immersion, while Food enthusiasts showed the highest interest in culinary experiences, including local cuisine and cooking workshops. Nature-Based Learners gravitated toward educational and conservation-themed activities, such as survival training and birdwatching. Meanwhile, Diverse enthusiasts showed high interest across all activity types, particularly in nature and food, making them the most broadly engaged segment. These differences express the variety of motivations driving visitors’ participation in creative tourism within national parks. Media preferences also varied by group, with a strong overall trend toward visual content. Photos, short videos, and streaming media were consistently more influential in shaping travel decisions than text-based content. Nature explorers, Food enthusiasts, and Diverse enthusiasts showed a clear preference for visual and experiential media formats, indicating a desire for immersive storytelling and engaging imagery. In contrast, Local advocates and Nature-based learners demonstrated more interest in text-based and educational media, suggesting a preference for detailed, informative content. Across all groups, influence from friends, online influencers, and personal motivation played a significant role in shaping travel behavior, highlighting the importance of peer networks and digital engagement in promoting creative tourism.

5. Discussion

5.1. Key Insights and Theoretical Contributions

This study contributes to the expanding literature on creative tourism, digital communication, and outdoor recreation in nature-based settings by empirically identifying five distinct visitor segments within Thailand’s national parks, based on their preferences for creative activities and media engagement. The segmentation, comprising Local advocates, Nature explorers, Food enthusiasts, Nature learners, and Diverse enthusiasts, expresses varying degrees of behavioral participation, learning orientation, and sensory preference. These findings reinforce the value of activity-based segmentation in protected area tourism, as supported by McKercher et al. [

31] and Stemmer et al.[

33], and offer practical direction for designing visitor-centered and resource-sensitive experiences.

A key theoretical contribution of this study lies in illustrating how the concept of creative tourism that normally applied in culture-based tourism contexts can be effectively extended to nature-based and outdoor recreation environments. The activity groupings identified in this study, including nature learning, scenic immersion, local food experiences, and community participation, closely align with Richards’ [

22] creative tourism framework, which emphasizes participatory, skill-based, and sensory-rich engagement. This alignment suggests that national parks can promote creativity through nature-based experiences, such as guided hikes, birdwatching workshops, edible plant walks, or conservation volunteering. These activities do not only involve recreation, but also encourage reflection, learning, and cultural appreciation. Importantly, this study also highlights how creative tourism preferences interact with media consumption behaviors. Visitors favoring experiential and sensory-rich outdoor activities, such as Nature explorers and Food enthusiasts, tended to engage more with visual and audiovisual content, such as photos, short videos, and streaming media. Conversely, learning-oriented groups, including Nature-Based Learners and Local advocates, presented stronger responsiveness to text-based and educational content. This pattern supports the Elaboration Likelihood Model [

40], where visitors with greater cognitive involvement respond through central processing routes, favoring detailed, informative content, while more emotionally driven or recreation-focused users respond to peripheral cues, such as imagery and storytelling.

In summary, this study suggests that integrating creative tourism and outdoor recreation frameworks offers a promising path for enriching visitor experiences in national parks. By recognizing the diversity in motivations and media preferences, park managers can develop more inclusive, meaningful, and sustainable tourism programs that blend nature, culture, and creativity while reinforcing conservation values and supporting local community engagement.

5.2. Strategic Guidelines and Implications for Developing Creative Tourism in Thailand’s National Parks

The key findings of this study confirm that Thailand’s national parks are well-positioned to support and expand creative tourism, moving beyond traditional models of passive sightseeing toward more participatory, experience-based engagement. The four activity dimensions identified including 1) Nature-based learning, 2) Scenic immersion, 3) Community participation, and 4) Culinary activities. These results demonstrate that visitors are increasingly motivated by meaningful interactions with nature, culture, and local communities. Based on these insights, five key guidelines are proposed:

Broaden the Creative Tourism Landscape in Nature-Based Contexts: Normally, creative tourism is often associated with urban and heritage settings, but this study confirms its relevance in natural environments. Activities such as birdwatching workshops, survival training, forest cooking, craft-making, and conservation volunteering align with participatory and skill-building principles central to creative tourism [

22]. National parks can thus be positioned not only for recreation but also for learning, cultural exchange, and personal development.

Design Targeted Programs for Distinct Visitor Segments: The five visitor clusters (Local advocates, Nature explorers, Food enthusiasts, Nature Learners, and Diverse Enthusiasts) demonstrate the need for differentiated programming. Creative activities should reflect each segment’s motivations and behaviors. For example, immersive visual content for Nature explorers, culinary sustainability for Food enthusiasts, and community-based workshops for Local advocates.

Enhance Community Engagement and Local Economic Participation: The growing interest in local culture and products presents a need to better integrate community enterprises into park experiences. While such offerings exist, they often lack visibility or depth. Strengthening interpretation and creating emotional connections can increase tourist engagement and benefit local livelihoods.

Leverage Media Strategies to Deepen Engagement: While visual media broadly influence all groups, learning-oriented segments also respond to text-based content. Communication should match content format to function—short videos for visual appeal, infographics for education, and livestreams for real-time interaction. Segment-specific media strategies can strengthen both emotional and cognitive engagement.

Promote Transformative Engagement: Creative tourism should enhance emotional engagement to encourage reflection, learning, and environmental stewardship. By embedding conservation messages within participatory experiences (such as QR-tagged scenic trails or behind-the-scenes storytelling) parks can shift visitors from passive consumption to active advocacy. This approach aligns with transformative learning theory and supports long-term sustainability goals. To support this,

Table 6 presents a set of transformative strategies, offering illustrative examples of how each visitor segment can be engaged through tailored activities and content that extend their interests into deeper learning and connection.

By identifying distinct visitor segments, park managers can design targeted programs that align with diverse motivations and foster inclusive participation. These strategies form a practical framework for enhancing visitor satisfaction while supporting sustainability, conservation, and local engagement. Co-creating tourism products with communities ensures authenticity and equitable economic benefits. Equally important is aligning digital content with visitor preferences—using scenic visuals, educational materials, and interactive formats. Finally, embedding conservation narratives through interpretive tools and participatory experiences fosters emotional connection and pro-environmental behavior. This holistic approach helps national parks fulfill their educational and conservation missions while enriching tourism outcomes.

5.3. Implementation Plan

To operationalize these insights and ensure their integration into both site-level management and broader tourism development policies, a phased action plan is proposed.

5.3.1. Short-Term (1-12 Months): Foundation and Quick Wins

In the first year, the priority is to strengthen the foundation for targeted visitor engagement. Firstly, segment-specific media initiatives will be created for different visitor groups, such as visually rich short videos for Nature Explorers, culinary-focused audiovisual content for Food Enthusiasts, culturally grounded storytelling for Local Advocates, educational infographics and live-stream workshops for Nature Learners, and multi-format campaigns for Diverse Enthusiasts. Secondly, park staff will receive training in digital storytelling, conservation messaging, and visitor engagement, ensuring that human resources are equipped with the skills needed to support creative tourism. This reflects research stressing the importance of staff development and preparedness for resilience in national parks [

50] and the role of digital storytelling in enhancing visitor experience [

51]. Thirdly, to maintain consistency and relevance, a seasonal content calendar will also be established. This calendar will outline communication themes and activities throughout the year, aligning with park events, peak tourism periods, and natural highlights such as blooming seasons, wildlife migrations, or cultural festivals. By linking content to these recurring events, the calendar helps ensure that messaging is timely, engaging, and aligned with visitor interests. In addition, rapid feedback tools such as online surveys, polls, and social media analytics will be used to assess audience response and make agile adjustments. These practices are consistent with sustainability-oriented monitoring frameworks that emphasize continuous assessment and adaptive management [

52,

53].

5.3.2. Medium-Term (1–3 Years): Scaling and Integration

In the medium term, creative tourism will be integrated into both park management and provincial tourism strategies. Firstly, partnerships with local communities are needed. Local communities will be engaged as co-creators of tourism products that align with visitor segments, drawing on evidence that co-creation strengthens visitor experiences and generates shared value [

54]. Second, collaborations with influencers can expand audience reach. Partnerships with influencers will be developed to expand market reach, supported by research showing their influence on visit intentions [

55]. Thirdly, to ensure accountability and adaptive management, a monitoring and evaluation system will be established to measure levels of visitor engagement, benefits for local communities, and ecological impacts. Additionally, an annual Creative Tourism Festival will be introduced to showcase co-created products, reinforce brand identity, and enhance resilience through the promotion of both cultural and natural heritage [

50].

5.3.3. Long-Term (3–5 Years): Sustainability and Policy Integration

In the long term, creative tourism will be institutionalized as a policy priority within protected area management. Firstly, a unified national branding initiative, “Thailand’s Creative National Parks,” will position the country as a leader in sustainable and creative nature-based tourism, drawing on customer-based brand equity principles [

56]. Secondly, longitudinal monitoring will be conducted to generate data that informs evidence-based policymaking, ensuring a careful balance between conservation objectives and tourism development [

52,

53]. Thirdly, targeted international campaigns will promote Thailand’s national parks in the global market, leveraging technology-driven competitiveness and responsible tourism positioning [

57]. Lastly, to support capacity building and innovation, flagship parks will establish Learning and Innovation Centers dedicated to training, research, and knowledge exchange, serving as regional hubs that strengthen resilience and drive long-term adaptation in creative tourism [

50].

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Limitations of Research: Firstly, the selected site focused on national parks with high visitation may overrepresent mainstream tourists while underrepresenting niche markets such as highly motivated creative tourists who prefer less visited or alternative destinations. Secondly, the findings rely on participants’ self-reported preferences and media influence, which may be affected by recall bias or social desirability. This limits the accuracy of media behavior interpretation. Finally, while content type and media format were analyzed, their combined or interactive effects were not explored, potentially missing nuanced insights into how content design influences tourist decision-making.

Future research should prioritize longitudinal studies to understand how visitor motivations and media preferences evolve over time, especially in today’s rapidly shifting digital landscape. Broader societal trends, including post-pandemic recovery, climate change awareness, and technological innovation, are reshaping how people engage with outdoor recreation and nature-based experiences. Second, research should expand beyond high-visitation parks to include lesser-known, community-managed, or ecotourism areas across diverse ecological zones. This would offer a more holistic view of creative tourism opportunities and visitor diversity. Third, exploring the interaction between content types (e.g., scenic, educational, cultural) and media formats (e.g., videos, livestreams, infographics) can clarify how message design influences engagement and behavior. Finally, future studies should test segment-specific communication and programming strategies through field experiments or pilot projects. Measuring outcomes such as visitor satisfaction, pro-environmental behavior, or conservation awareness will offer practical insights for tourism planners and park managers. These findings would strengthen efforts to design sustainable, engaging, and inclusive tourism experiences in protected areas.

6. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the practical value of combining activity-based visitor segmentation with media preference analysis to inform the development of creative tourism and digital communication strategies in national parks. Using a mixed-methods approach, the research integrated document analysis of 133national parks in Thailand, field surveys across 10 national parks, and a structured visitor survey with 1,133 respondents. The analysis identified five distinct visitor segments namely, 1) Local advocates, 2) Nature explorers, 3) Food enthusiasts, 4) Nature Learners, and 5) Diverse Enthusiasts, each exhibiting unique preferences for creative tourism activities and media formats. The findings illustrate a clear paradigm shift in tourism promotion, from generic messaging to more targeted, participatory storytelling. Emotionally engaging visual content resonates strongly with sensory-driven tourists, while cognitively rich and informative materials are more effective for learning-oriented visitors. These differentiated approaches not only enhance visitor satisfaction and engagement but also support broader goals of environmental stewardship, sustainability, and a stronger sense of place within protected areas.

Practically, this research offers a flexible framework for designing creative tourism programs that integrate both cultural and natural elements. It reaffirms that nature-based destinations can deliver immersive, skill-based, and reflective experiences comparable to those in cultural settings. By aligning activity design with visitor motivations and communication preferences, national parks can better serve diverse audiences while reinforcing conservation values and community engagement. While this study focuses on national parks in Thailand, the framework can be adapted for application in other protected areas worldwide. Guidelines recommended for creative tourism development are presented including 1) broadening the creative tourism landscape in nature-based contexts, 2) designing targeted programs for distinct visitor segments, 3) enhancing community engagement and local economic participation, 4) leveraging media strategies to deepen engagement, and 5) promoting transformative. Future research could build on these findings by exploring longitudinal changes in visitor behavior, assessing the real situation effectiveness of customized media strategies, and examining behavioral outcomes such as conservation support, repeat visitation, and community impact. Such efforts will be essential for developing tourism models that are not only engaging and inclusive but also resilient, educational, and ecologically responsible.

Author Contributions

Kinggarn Sinsup: Writing– original draft, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Conceptualization. Sangsan Phumsathan: Writing– review & editing, Visualization, Supervision, Methodology, Conceptualization.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and exempted from ethical review by the Kasetsart University Research Ethics Committee (KUREC) (protocol code KUREC-SSR66/139; date of exemption: 15 November 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The author would like to express sincere gratitude to the National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT) for financial support under the Royal Golden Jubilee Ph.D. Program (Grant No. N41A650068). Appreciation is also extended to the Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation (DNP), Thailand, for their valuable cooperation and support during the data collection process in national park areas.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EFA |

Exploratory Factor Analysis |

| DNP |

Department of National Parks, Wildlife, and Plant Conservation |

References

- Kamarulzaman, N.D.; Hanafiah, M.H.; Nazlan, N.H.; Cham, T.-H. Overtourism and social media: The impact of social media attachment on tourists’ decision-making behaviour. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korani, Z.; Hall, C.M.; Heris, J.A. From pixels to places: How Instagram redefines urban tourism in Isfahan. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2025, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iddawala, J.; Lee, D. Regenerative tourism: Context and conceptualisations. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

UN Tourism.World Tourism Barometer; UN Tourism: Madrid, Spain, 2024; Volume 22, Issue 2 (May 2024). [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Gössling, S.; Scott, D. (Eds.) The Routledge Handbook of Tourism and Sustainability; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Stylidis, D.; Quintero, A.D. Understanding the effect of place image and knowledge of tourism on residents’ attitudes towards tourism and their word-of-mouth intentions: Evidence from Seville, Spain. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2022, 19, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, R.A.; Chim-Miki, A.F.; Valente, D. Influence factors on intention to revisit and recommend small non-coastal tourism destinations: Insights from a low-density territory. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmford, A.; Beresford, J.; Green, J.; Naidoo, R.; Walpole, M.; Manica, A. A global perspective on trends in nature-based tourism. PLoS Biol. 2009, 7, e1000144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, J.E.; Ortiz, L.; Smith, B.K.; Devineni, N.; Colle, B.; Booth, J.F.; Rosenzweig, C. New York City Panel on Climate Change 2019 Report Chapter 2: New methods for assessing extreme temperatures, heavy downpours, and drought. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2019, 1439, 30–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of National Park, Wildlife and Plant Conservation (DNP). Public Data Thailand National Park Service Visitor Statistics. Available online: https://catalog.dnp.go.th/dataset/stat-tourism (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Tourism Authority of Thailand. The Survey on Travel Behavior of Thai People 2022. Available online: https://intelligencecenter.tat.or.th/articles/49764 (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation (DNP). The Management of National Parks Adheres to the Policies Outlined in the National Parks Act, Enacted in the Year B.E. 2562; Department of National Parks: Bangkok, Thailand, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Phumsathan, S.; Manowaluilou, N.; Udomwitid, S. Moving away from mass tourism to creative tourism—How to get started: A case study of creative tourism development of Trat province, Thailand. In Proceedings of the 6th Advances in Hospitality and Tourism Marketing and Management Conference, Guangzhou, China; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, G.; Raymond, C. Creative tourism. ATLAS News 2000, 23, 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Wessels, J.-A.; Douglas, A. Exploring creative tourism potential in protected areas: The Kruger National Park case. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2022, 46, 1482–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Pongsakornrungsilp, P.; Klamsaengsai, S.; Ketkaew, K.; Tonsakunthaweeteam, S.; Li, L. Influence of creative tourist experiences and engagement on Gen Z’s environmentally responsible behavior: A moderated mediation model. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E.R.; Rice, W.L.; Armatas, C.A.; Thomsen, J.M. The effect of place attachment and leisure identity on wildland stewardship. Leis. Sci. 2024, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichman, C.J. Social media influences national park visitation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2310417121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackenzie, A.L.; Dundas, S.J.; Zhao, B. The Instagram effect: Is social media influencing visitation to public lands? Land Econ. 2024, 100, 256–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, I.; Lim, W.M.; Aggarwal, A. Creative tourism: Reviewing the past and charting the future. Benchmarking Int. J. 2025, 32, 109–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, C.; Remoaldo, P.; Alves, J.A.; Lopes, H.S. A bibliometric analysis on creative tourism (2002–2022). J. Tour. Cult. Change 2024, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. Creativity and tourism: The state of the art. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 1225–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anuar, A.N.A.; Haron, M.S. Souvenirs purchase among tourists: Perspectives in national park. J. Tour. Hosp. 2017, 6, 1000287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Soldato, E.; Massari, S. Creativity and digital strategies to support food cultural heritage in Mediterranean rural areas. Eur. Med. J. Bus. 2024, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, H.; Pinheiro, A.J.; Gonçalves, E.C. Place attachment in protected areas: An exploratory study. PASOS Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2023, 21, 473–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xie, P.F. Motivational determinants of creative tourism: A case study of Albergue Art Space in Macau. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 1240–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Muangasame, K.; Kim, S. ‘We and Our Stories’: Constructing Food Experiences in a UNESCO Gastronomy City. Tour. Geogr. 2021, 23, 753–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P.A.; Matthews, C. Building a culture of conservation: Research findings and research priorities on connecting people to nature in parks. PARKS 2015, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.-K.; Luh, D.-B.; Kung, S.-F. A taxonomy of creative tourists in creative tourism. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappalepore, I.; Maitland, R.; Smith, A. Prosuming creative urban areas: Evidence from East London. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 44, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaho, Y. Conceptualizing the adventure tourist as a cross-boundary learner. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2024, 47, 100795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, B.; Tolkach, D.; Ng, E. Choosing the optimal segmentation technique to understand tourist behaviour. J. Vacat. Mark. 2023, 29, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesonen, J.A. Targeting Rural Tourists in the Internet: Comparing Travel Motivation and Activity-Based Segments. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2015, 32, 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stemmer, K.; Fredman, P.; Lindberg, K.; Veisten, K. How does activity specialization affect nature-based tourism package choice? Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2023, 23, 412–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remoaldo, P.; Serra, J.; Marujo, N.; Alves, J.; Gonçalves, A.; Duxbury, N. Profiling the participants in creative tourism activities: Case studies from small and medium-sized cities and rural areas in Portugal. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 36, 100746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesonen, J.A.; Tuohino, A. Activity-based market segmentation of rural well-being tourists: Comparing online information search. J. Vacat. Mark. 2017, 23, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Gretzel, U. Role of social media in online travel information search. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, M.M.; Di Felice, M.; Mura, M. Facebook as a destination marketing tool: Evidence from Italian regional destination management organizations. Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 321–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, R.; Conduit, J.; Fahy, J.; Goodman, S. Social media engagement behaviour: A uses and gratifications perspective. J. Strateg. Mark. 2016, 24, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasci, A.D.A.; Gartner, W.C. Destination image and its functional relationships. J. Travel Res. 2007, 45, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T. The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. In Berkowitz, L. (Ed.) Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1986; Volume 19, pp. 123–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, S.H. Environmental Interpretation: A Practical Guide for People with Big Ideas and Small Budgets; Fulcrum Publishing: Golden, CO, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ballantyne, R.; Packer, J. Using tourism free-choice learning experiences to promote environmentally sustainable behaviour: The role of post-visit ‘action resources’. Environ. Educ. Res. 2011, 17, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilligoss, B.; Rieh, S.Y. Developing a unifying framework of credibility assessment: Construct, heuristics, and interaction in context. Inf. Process. Manag. 2008, 44, 1467–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, R.; Packer, J.; Hughes, K. Tourists’ support for conservation messages and sustainable management practices in wildlife tourism experiences. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 658–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Liu, F.; Liu, W.; Liu, S.; Chen, Y.; Xu, D. Effects of information quality on information adoption on social media review platforms: Moderating role of perceived risk. Data Sci. Manag. 2021, 1, 13–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahtar, A.Z. The impact of Instagram Reels on youths’ trust and their holiday intention. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2023, 13, 15901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jie, Y.; Xingqin, Q.; Yensen, N. The marketing of destination distinctiveness: The power of tourism short videos with enjoyability and authenticity. Curr. Issues Tour. 2024, 27, 2217–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M. Parasocial interactions in digital tourism: Attributes of live streamers and viewer engagement dynamics in South Korea. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huyser, M.M.; van der Merwe, P.; Ali, A. Contingency strategies to foster resilience in national parks during crisis events such as COVID-19. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2025, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korani, Z.; Hall, C.M.; Heris, J.A. From Pixels to Places: How Instagram Redefines Urban Tourism in Isfahan. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2025, 1–30, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glyptou, K. Operationalising tourism sustainability at the destination level: A systems thinking approach along the SDGs. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2022, 21, 95–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.N.; Muhs, C.; Andraz, J.; Nunes, R.; Lança, M.; Silva, J.A. An assessment model of the Algarve as a sustainable tourism destination: A conceptual framework. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2024, 22, 367–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, A.C.; Mendes, J.; Valle, P.O.; Scott, N. Co-creation of tourist experiences: A literature review. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 21, 369–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Wang, L.; Liu, H. Influencer marketing and destination visit intention: The interplay between influencer type, information format, and picture color hue. J. Travel Res. 2025, advance online publication. [CrossRef]

- Konecnik, M.; Gartner, W.C. Customer-based brand equity for a destination. Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 400–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yolcu, S.; Şahin, A.; Dirsehan, T. Gaining ground: How technology fuels hotel competitiveness—A systematic review of the literature. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2025, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).