A New Lab Partner: Robots in Chemistry

Imagine a robot that can work 24/7 in your chemistry lab—no lunch breaks, no distractions, no complaints about lab politics. For many of us, the idea of a robot assistant was just a dream during those long hours of titration and synthesis, when we wished someone (or something) could do the repetitive work for us. We joked that ChatGPT could help with assignments, but it couldn’t hold a beaker. At least, we thought, our hands-on skills made us irreplaceable by AI.

But now, robots are entering our territory—and it’s both exciting and a little unsettling. At the University of Liverpool, a mobile robotic chemist autonomously performed 688 experiments in just 8 days [

1,

2], discovering photocatalysts that were six times more active than previous ones [

2]. This kind of achievement would typically take a team of experienced human chemists several months to complete. Is this the beginning of “Human vs Robot,” or the start of a new era of “Human and Robot” collaboration?

The Synthesis Struggle: Why Chemistry Feels Like a Maze

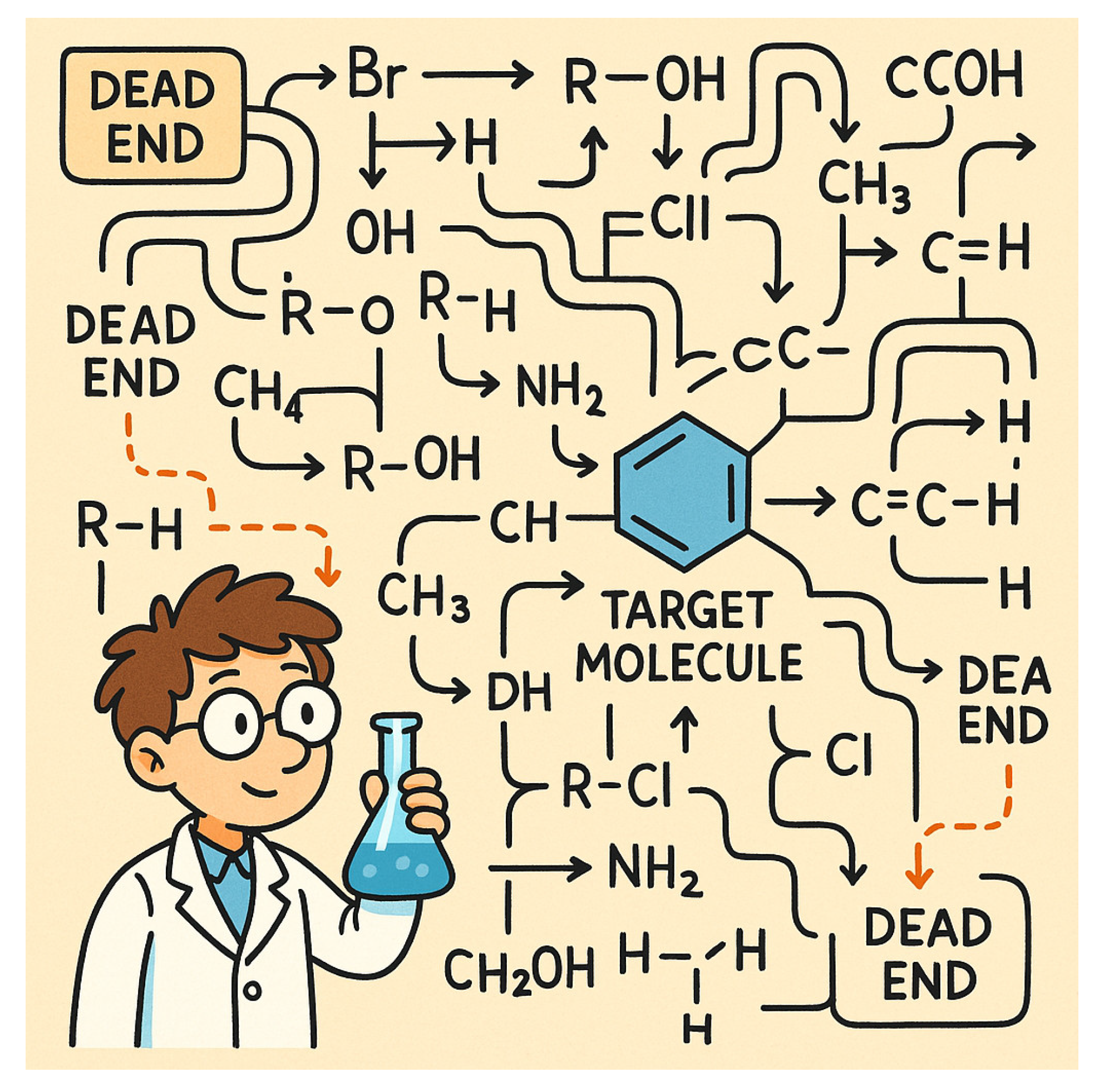

Figure 1.

The Synthesis Maze.

Figure 1.

The Synthesis Maze.

Every chemistry student knows the frustration of synthesis-staring at a target molecule with no GPS to guide you. People outside the lab often think it’s just manual labour—mix A with B, add some heat, say ‘Gilly Gilly Hogus Fogus,’ and magic happens. But the real magic doesn’t happen in the beaker; it happens in your brain, after hours of failed attempts and endless ‘let’s try this’.

The truth is, the retrosynthetic search space is an astronomical combinatorial maze [

3]. It’s like a puzzle where difficulty increases exponentially with each move. At every step, there are more than 10,000 possible transformations to consider, and with each additional reaction step, the search space grows exponentially [

3]. Designing a synthetic route for a novel molecule is not just hard—it’s overwhelming. It’s like trying to find your way to a new city with only a pile of old, incomplete maps, never sure if you’re on the right road.

Why Human Intuition Isn’t Enough

Human intuition, as powerful as it is, has its limits. We’re constrained by our experience, the equipment available, and sometimes even as silly as scheduling conflicts. The strategies we choose are often subjective, shaped by the chemistries we know best [

4]. That means we might miss a key disconnection or overlook a creative solution simply because it’s outside our comfort zone.

Traditional approaches to synthesis planning have always suffered from incompleteness, infeasible suggestions, and human bias [

5]. For students, this means that even after hours of work, the “right answer” can feel just out of reach.

From Rulebooks to Algorithms: The Rise of AI

As scientists, we can’t just complain about a problem—we need a solution. For the parts of synthesis where brainpower isn’t essential, we can delegate the work to machines, just like we use calculators for long calculations. But in chemistry, the “calculator” is now much more powerful: it can handle multi-directional, complex decisions, and even “think” to a certain extent—that’s what we call artificial intelligence (AI).

In the early days, rule-based expert systems tried to help by encoding chemists’ knowledge as a set of rules [

3]. These systems, developed since the 1960s, aimed to emulate human retrosynthesis planning [

6] But they depended heavily on human input, were labour-intensive, and couldn’t overcome human bias. Manual encoding of reaction rules required significant effort from many experts, and these systems often suffered from incompleteness, infeasible suggestions, and inherent bias [

7,

8].

As technology evolved, so did the complexity of synthesis. The more we explored, the more we realized how deep and precise the challenges really are. We need a new approach—one that can learn from vast amounts of data, spot patterns and trends that are too broad or too subtle for us to see. This is where machine learning comes in.

Machine Learning in Action: Suitable Example

Take the Molecular Transformer model, for example. It has demonstrated a 90.4% top-1 accuracy for reaction prediction and is 89% accurate in classifying whether a prediction is correct (uncertainty estimation). It outperforms all known algorithms in the reaction prediction literature and has been used by thousands of organic chemists worldwide for more than 40,000 predictions In a study by [

9], 80 random reactions were given to 11 chemists and the model. The Molecular Transformer in the same test achieved a top-1 accuracy of 87.5%, significantly higher than the best human (76.5%) and the best graph-based model (72.5%). Just like this we have more efficient models like IBM Rxn and AiZynthFinder [

10] that we can explore.

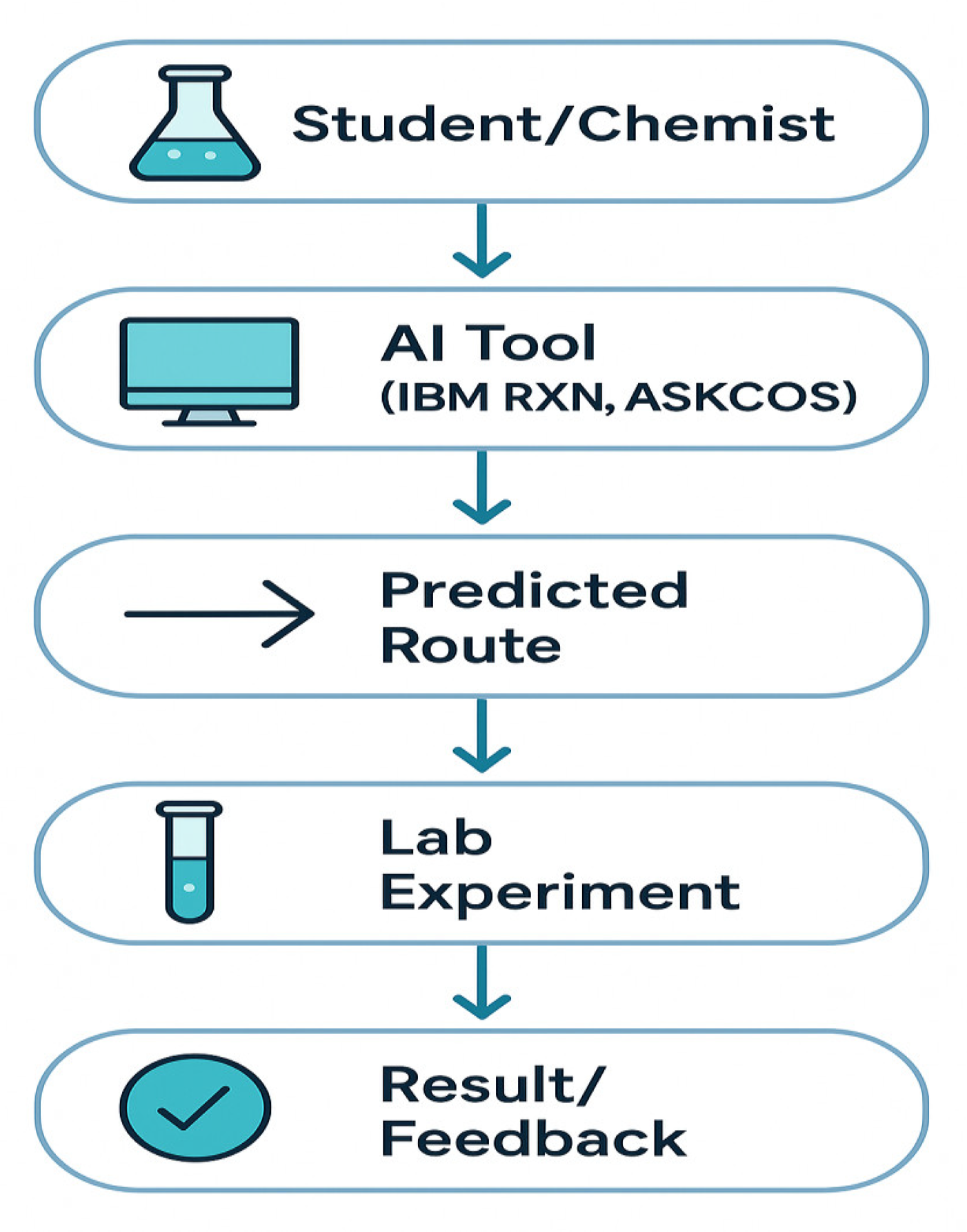

Figure 2.

How AI Fits in the Lab.

Figure 2.

How AI Fits in the Lab.

So, can AI outperform humans? In some ways, yes. But the real question is: do we fight it, or do we work with it? In the era of Google Maps, we can’t be stuck with an atlas. The atlas is our foundation, but to move forward, we need to embrace new tools.

The Limits of AI: Why Chemists Still Matter

No tool is perfect just like us—not even the flashiest AI. Machine learning models are only as good as the data they’re fed. The same way if we never truly understand from our failures, we will again fail; If the training set is full of “greatest hits” reactions or only the success stories, the AI will happily ignore the weird, rare, or just plain stubborn chemistry that often shows up in real research [

11,

12]. Training a model is the same as teaching a toddler, the better you make them prepare for real life, all success and failures, the better they would perform

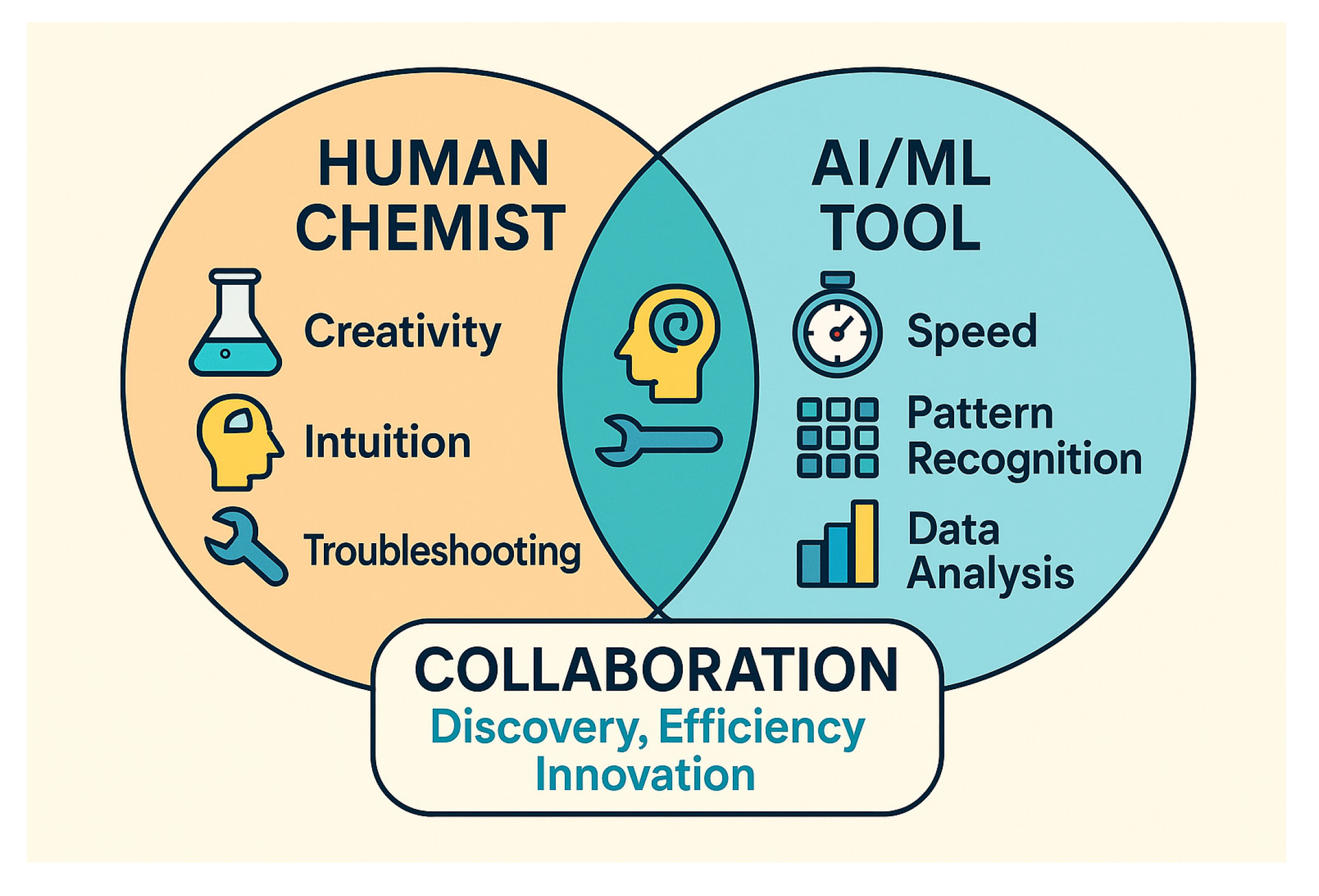

Figure 3.

Human vs. AI VS. Human+AI.

Figure 3.

Human vs. AI VS. Human+AI.

And then there’s the problem of generalization or we can call the “overconfident student” problem. Sure, ML can ace the test on familiar molecules, but throw it a truly oddball substrate or a reaction that’s never been seen before, and it might give you an answer that makes no sense at all [

11]. It’s like asking Google Maps for directions in a city where half the streets are missing from the map—sometimes you end up in a dead end, or worse, circling the same block, or worst case you fall from a half-prepared flyover. The model can’t tell you why a reaction failed, or what to do when your TLC plate looks like modern art instead of a single spot. It doesn’t get frustrated, but it also doesn’t get inspired. Reinforcement learning works to solve this, but it’s a long way forward

Let’s not forget: human chemists bring something to the table that no algorithm can replicate—intuition, creativity, and the ability to spot a “crazy idea” that just might work. We’re the ones who notice when a reaction smells off, or when a colour change hints at something unexpected. AI can suggest a route, but it can’t improvise when the NMR looks weird or the product refuses to crystallize.

So, for now, the real magic happens when humans and machines work together. AI is a powerful tool, but it’s not a replacement for the chemist’s brain—or their gut feeling. The next breakthrough will come from those who know how to use both.

Conclusion: The Next Breakthrough Is You

The chemistry lab is changing. We’re living through a revolution in chemistry and the whole field of science, and it’s happening faster than most of us realize Robots can now run experiments while we sleep, and AI can suggest synthetic routes faster than we can flip through a textbook. The tools we’ve explored—from IBM RXN to AiZynthFinder—aren’t just research curiosities anymore. They’re becoming as essential to modern chemistry from spectroscopy to chromatography to drug discovery.

But the real magic still happens when human curiosity meets machine intelligence. The best discoveries will come from those who know how to use both—who can ask the right questions, spot the unexpected, and use AI as a tool, not a crutch. AI just made our personalised mini laboratory for each of us, but still, we are the lead So, whether you’re just starting out or already deep in research, don’t be afraid of the robots. Learn to work with them. The next big breakthrough in chemistry might just come from your collaboration—with a little help from your new digital lab partner.

The lab of the future isn’t human versus machine. It’s human with machine. And that future starts with your next experiment.

References

- Tobias, A. V.; Wahab, A. Autonomous ‘Self-Driving’ Laboratories: A Review of Technology and Policy Implications. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2025, 12, 250646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burger, B. A Mobile Robotic Researcher. dphil, University of Liverpool, 2020. https://livrepository.liverpool.ac.uk/3087073 (accessed 2025-07-22).

- Ishida, S.; Terayama, K.; Kojima, R.; Takasu, K.; Okuno, Y. AI-Driven Synthetic Route Design Incorporated with Retrosynthesis Knowledge. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2022, 62, 1357–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Struble, T. J.; Alvarez, J. C.; Brown, S. P.; Chytil, M.; Cisar, J.; DesJarlais, R. L.; Engkvist, O.; Frank, S. A.; Greve, D. R.; Griffin, D. J.; Hou, X.; Johannes, J. W.; Kreatsoulas, C.; Lahue, B.; Mathea, M.; Mogk, G.; Nicolaou, C. A.; Palmer, A. D.; Price, D. J.; Robinson, R. I.; Salentin, S.; Xing, L.; Jaakkola, T.; Green, William. H.; Barzilay, R.; Coley, C. W.; Jensen, K. F. Current and Future Roles of Artificial Intelligence in Medicinal Chemistry Synthesis. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 8667–8682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradshaw, J.; Kusner, M. J.; Paige, B.; Segler, M. H. S. Barking up the Right Tree: An Approach to Search over Molecule Synthesis Routes Using AI; 2020. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Kong, M.; Mei, Y.; Yuan, L.; Huang, Z.; Kuang, K.; Wang, Z.; Yao, H.; Zou, J.; Coley, C. W.; Wei, Y. Artificial Intelligence for Retrosynthesis Prediction. Engineering 2023, 25, 32–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coley, C. W.; Green, W. H.; Jensen, K. F. Machine Learning in Computer-Aided Synthesis Planning. Acc Chem Res 2018, 51, 1281–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Automated System for Knowledge-Based Continuous Organic Synthesis (ASKCOS). https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/trecms/AD1195755 (accessed 2025-07-22).

- Coley, C. W.; Jin, W.; Rogers, L.; Jamison, T. F.; Jaakkola, T. S.; Green, W. H.; Barzilay, R.; Jensen, K. F. A Graph-Convolutional Neural Network Model for the Prediction of Chemical Reactivity. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 370–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shields, J. D.; Howells, R.; Lamont, G.; Leilei, Y.; Madin, A.; Reimann, C. E.; Rezaei, H.; Reuillon, T.; Smith, B.; Thomson, C.; Zheng, Y.; Ziegler, R. E. AiZynth Impact on Medicinal Chemistry Practice at AstraZeneca. RSC Med. Chem. 15, 1085–1095. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karande, P.; Gallagher, B.; Han, T. Y.-J. A Strategic Approach to Machine Learning for Material Science: How to Tackle Real-World Challenges and Avoid Pitfalls. Chem. Mater. 2022, 34, 7650–7665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raccuglia, P.; Elbert, K. C.; Adler, P. D. F.; Falk, C.; Wenny, M. B.; Mollo, A.; Zeller, M.; Friedler, S. A.; Schrier, J.; Norquist, A. J. Machine-Learning-Assisted Materials Discovery Using Failed Experiments. Nature 2016, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).