Submitted:

29 April 2025

Posted:

30 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Construction and Analysis of the Radical Reaction Database (RadicalDB)

2.1.1. Data Collection Strategy for RadicalDB

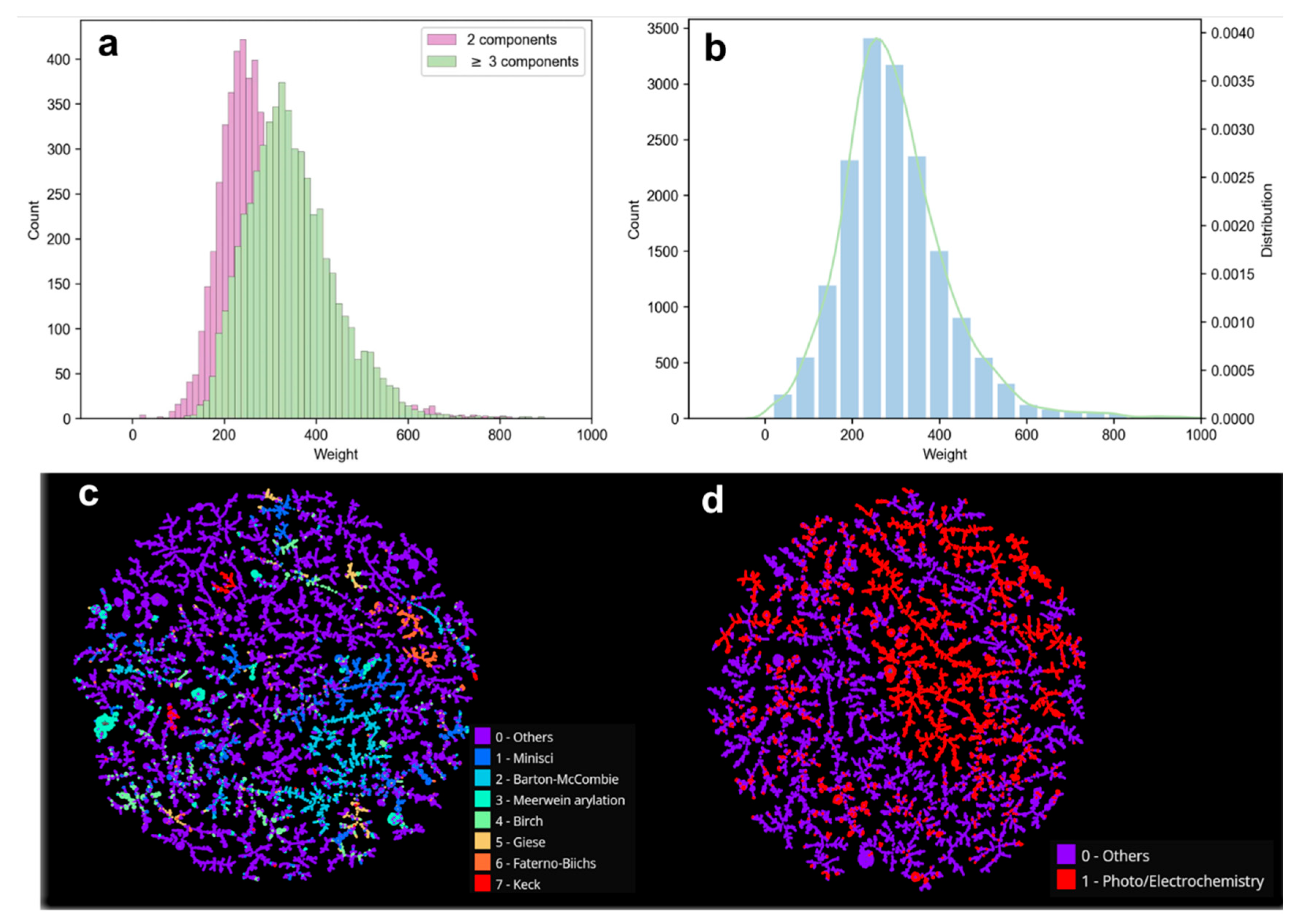

2.1.2. Composition and Distribution of RadicalDB Data

2.2. Training and Testing of the Radical Reaction Retrosynthesis Prediction Model (RadicalRetro)

- (1)

- Training Strategy for Mol-Transformer. Mol-Transformer typically employs transfer learning[25,51] to enhance its performance. In this study, a multi-task strategy[52] was used by combining the USPTO dataset with the target dataset (RadicalDB) for training, allowing the Transformer model to learn both the USPTO dataset (containing 1M reactions) and the chemical reaction features of RadicalDB. The ratio for mixed sampling was set at 9:1 (USPTO: RadicalDB).

- (2)

- Training Strategy for LocalRetro. First, DGL-LifeSci (https://github.com/awslabs/dgl-lifesci) was used to initialize the features of atoms and bonds, with the molecules in RadicalDB represented as graphs where vertices denote atoms and edges denote bonds. The message passing neural network (MPNN)[53] was applied to update the features of each atom, considering its neighboring atoms and bonds. Local reaction templates were then extracted by comparing the atomic mapping differences between products and reactants. This process resulted in the identification of 2,877 radical reaction retrosynthesis templates, including 2,227 bond-changing templates and 1,342 atom-changing templates. LocalRetro applies a global reaction attention mechanism (GRA)[48] to account for non-local effects in chemical reactions, using template classifiers to score the templates. During retrosynthesis analysis, the model predicts a set of local reaction templates for each chemical center, and these predicted templates are ranked by score to derive the final reactants.

- (3)

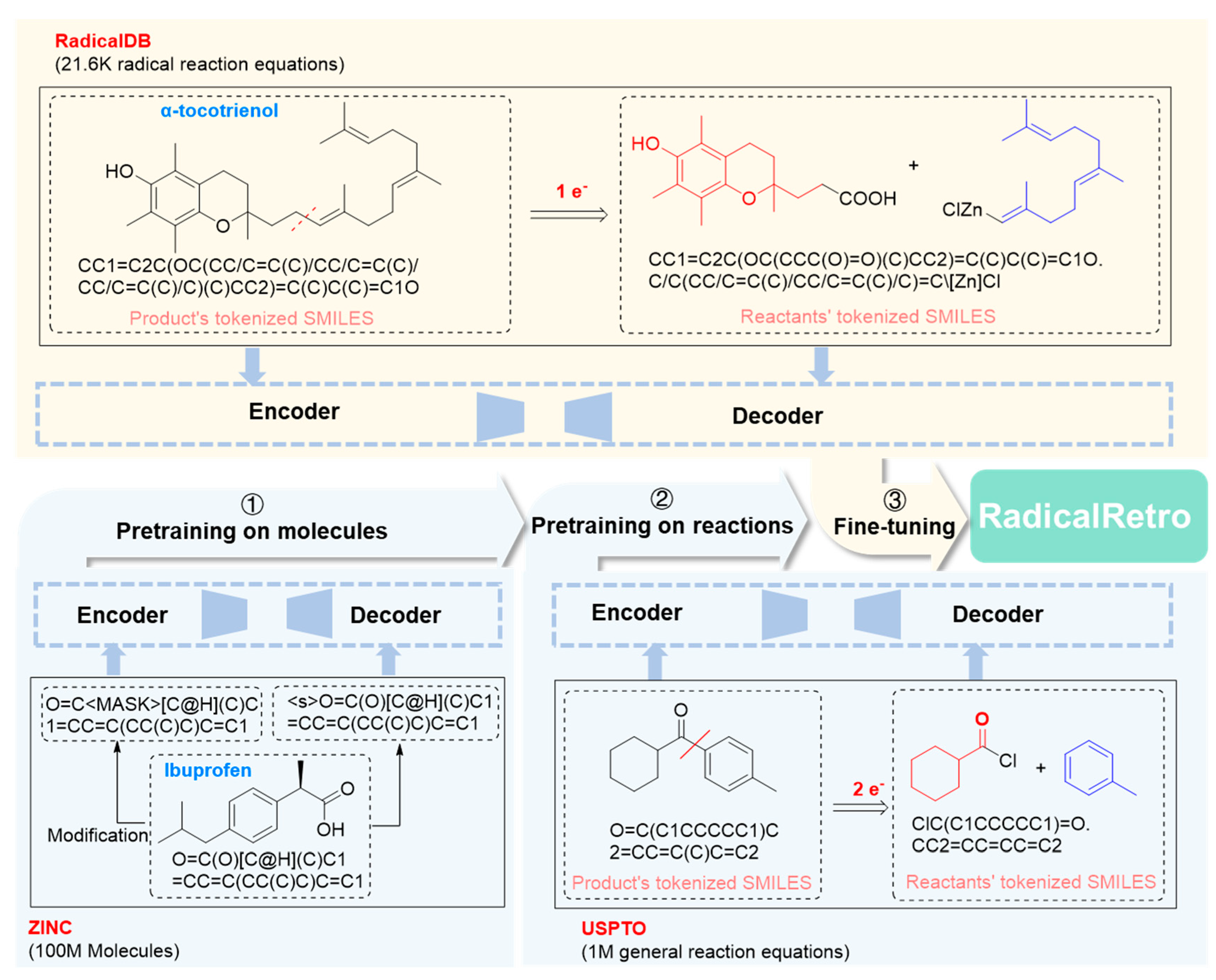

- Training Strategy for Chemformer. First, the ZINC-15 dataset[54] (containing 100 million molecules) was used for molecular pretraining. The pretraining process involved masking molecular SMILES codes, primarily through a span-masking algorithm, where short sequences within the SMILES were randomly replaced with a single "<MASK>" token to help the model better understand the combination patterns of atoms and bonds. Next, reaction pretraining was conducted using the USPTO dataset[26] (containing 1M reactions), allowing the model to learn chemical reaction patterns and features. Finally, fine-tuning was performed on the RadicalDB to help the model grasp the specifics and patterns of radical reactions. The resulting retrosynthesis Chemformer model, after molecular pretraining, reaction pretraining, and RadicalDB fine-tuning, is named RadicalRetro (Figure 2).

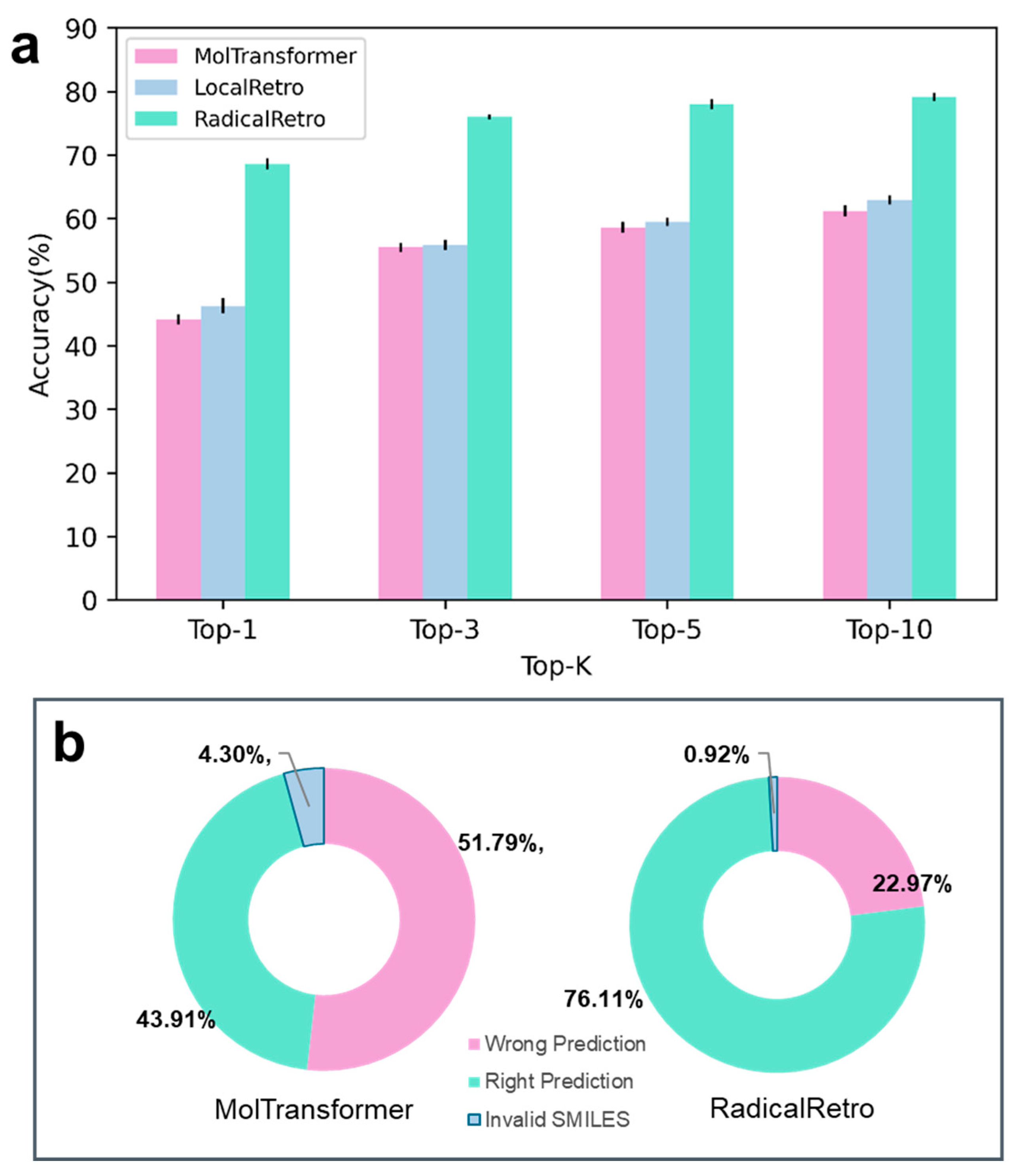

3. Test Results and Analysis

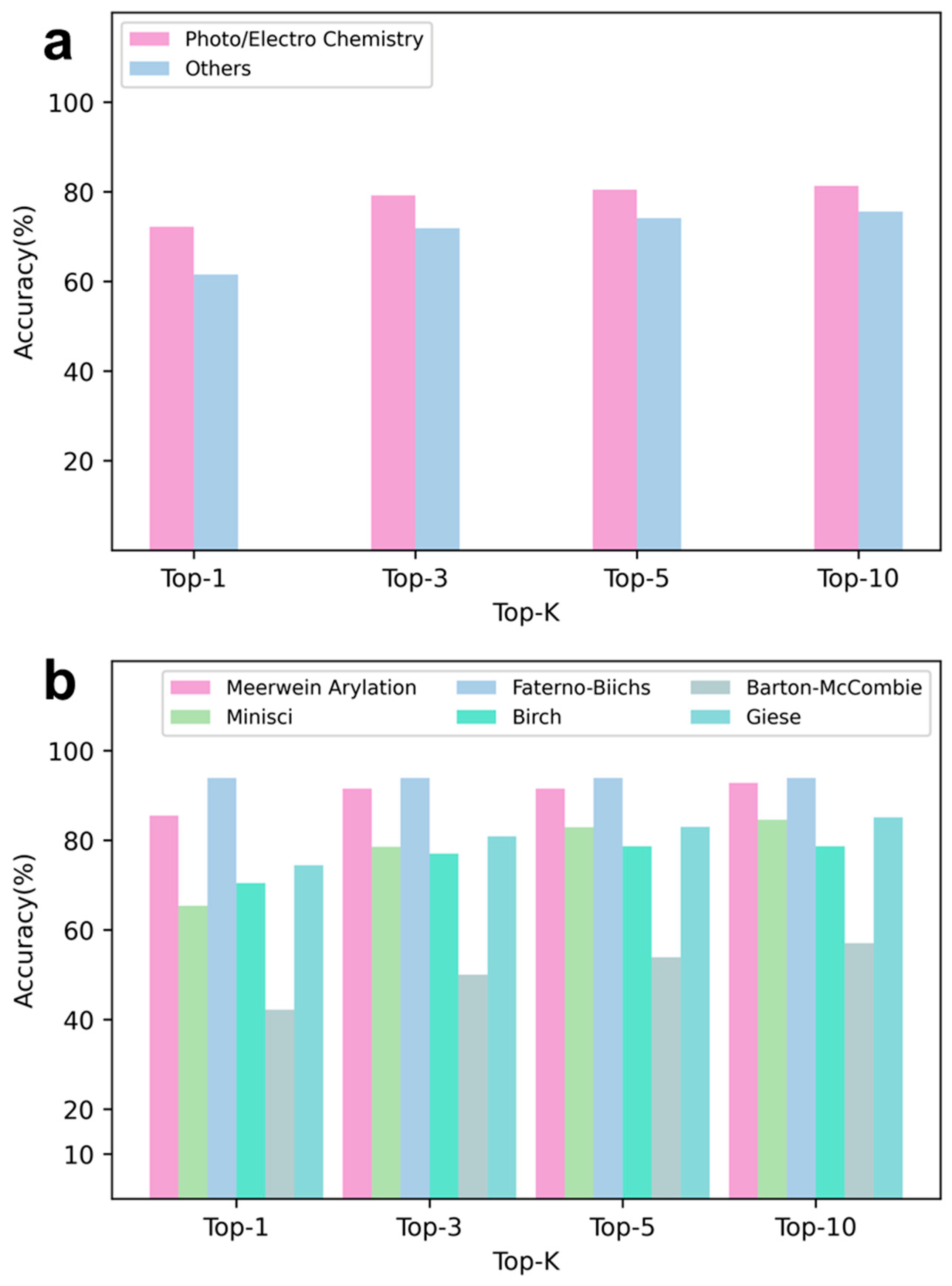

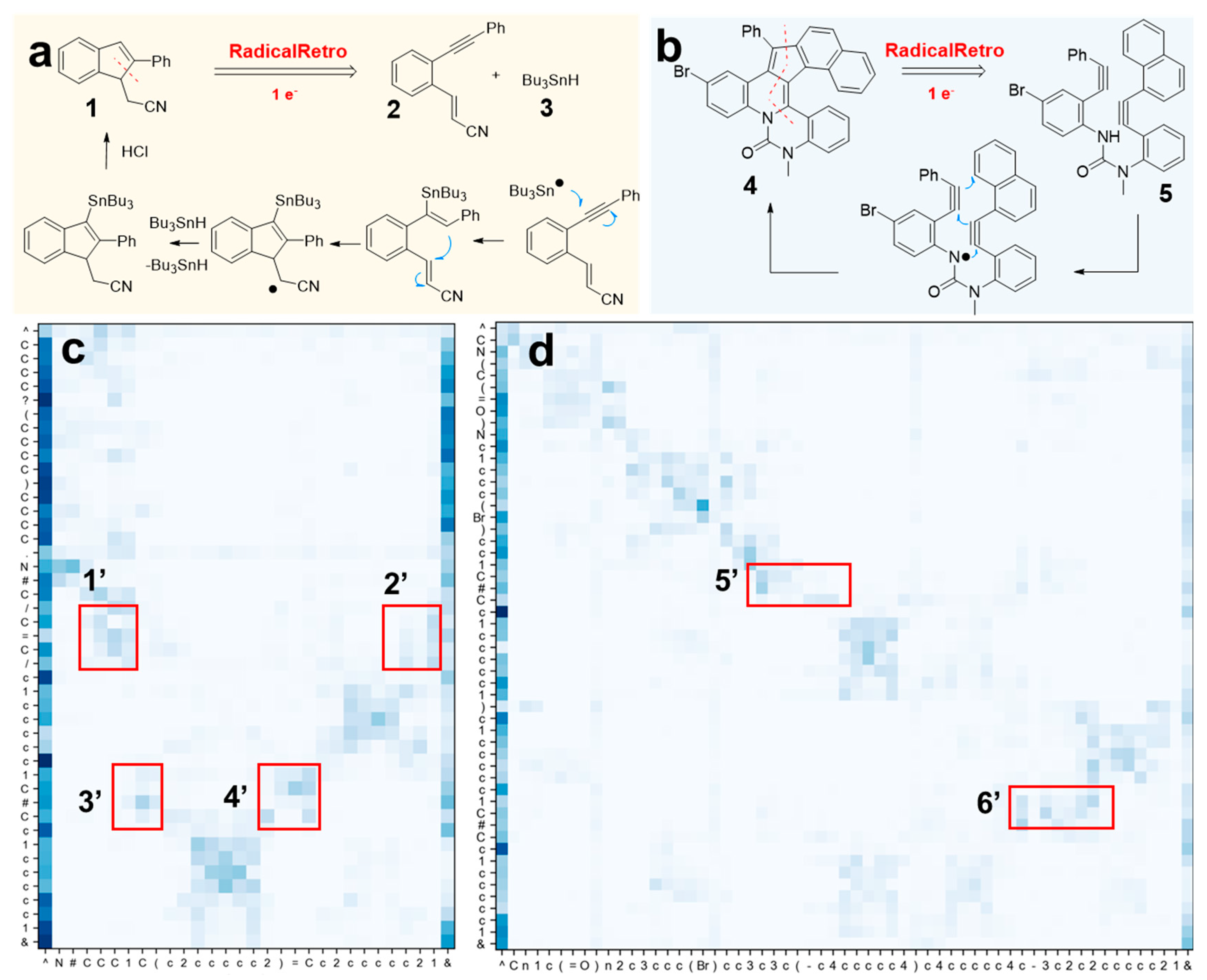

Interpretability of RadicalRetro

4. Application of RadicalRetro in Synthesis

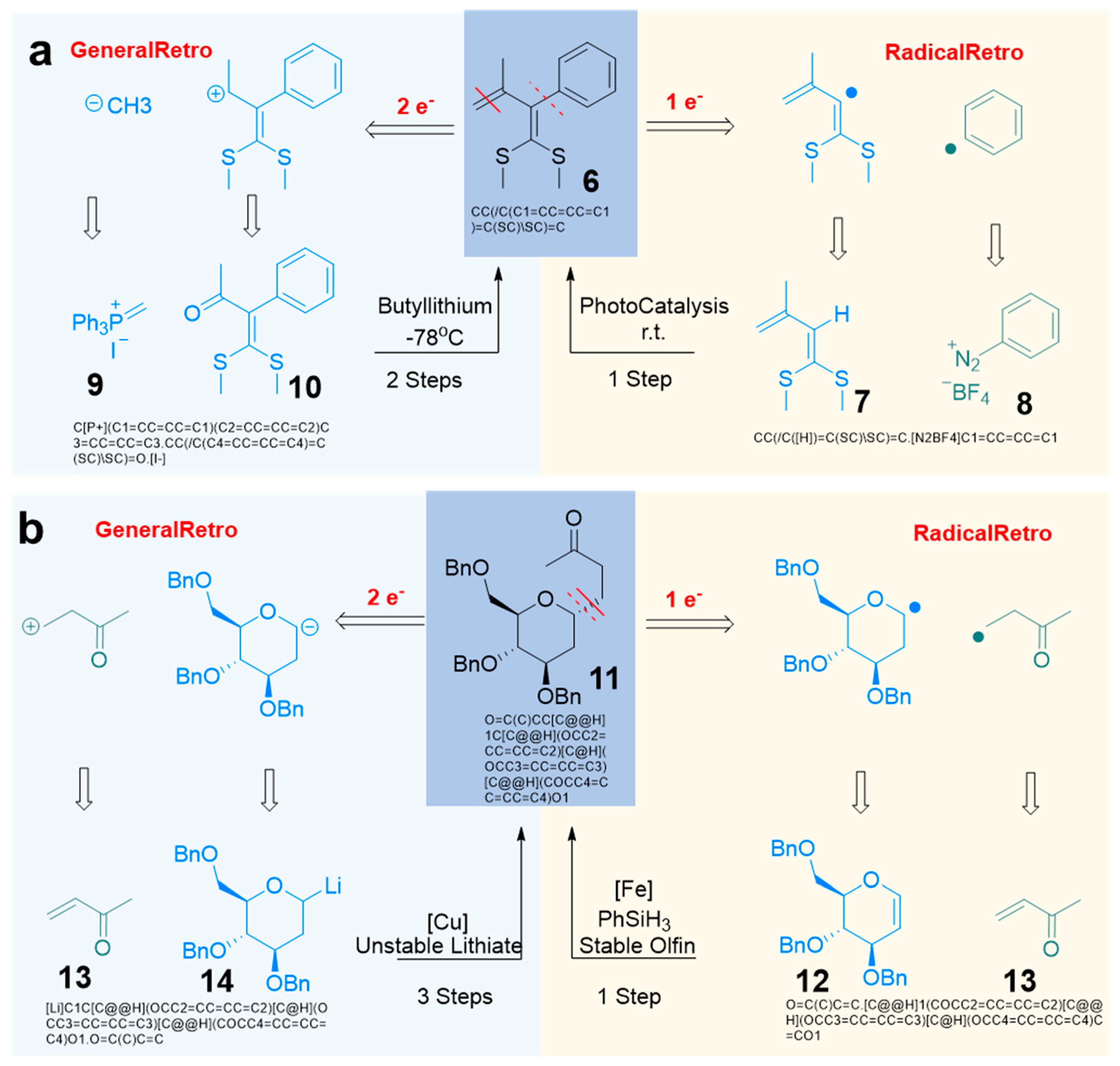

Retrosynthetic Analysis Using Radical Reaction Characteristics

5. Conclusions

6. Method

6.1. Deep Learning Models and Parameters

6.1.1. Chemformer

6.1.2. Mol-Transformer

6.1.3. LocalRetro

6.2. Training Strategy

6.3. Testing Method

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability

Code Availability

Acknowledgments

Competing Interests

References

- Corey, E. J. Robert Robinson Lecture. Retrosynthetic Thinking—Essentials and Examples. Chem. Soc. Rev. 1988, 17, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niwa, T.; Uetake, Y.; Isoda, M.; Takimoto, T.; Nakaoka, M.; Hashizume, D.; Sakurai, H.; Hosoya, T. Lewis Acid-Mediated Suzuki–Miyaura Cross-Coupling Reaction. Nature Catalysis 2021, 4, 1080–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Rogge, T.; Ackermann, L.; Shi, Z. Metal-Catalysed C–Het (F, O, S, N) and C–C Bond Arylation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 8903–8953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhoyare, V. W.; Sosa Carrizo, E. D.; Chintawar, C. C.; Gandon, V.; Patil, N. T. Gold-Catalyzed Heck Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 8810–8816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashita, Y.; Yasukawa, T.; Yoo, W.-J.; Kitanosono, T.; Kobayashi, S. Catalytic Enantioselective Aldol Reactions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 4388–4480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Young, T. A.; Duarte, F.; Lusby, P. J. Synergistic Noncovalent Catalysis Facilitates Base-Free Michael Addition. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 17743–17750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Földes, T.; Madarász, Á.; Révész, Á.; Dobi, Z.; Varga, S.; Hamza, A.; Nagy, P. R.; Pihko, P. M.; Pápai, I. Stereocontrol in Diphenylprolinol Silyl Ether Catalyzed Michael Additions: Steric Shielding or Curtin–Hammett Scenario? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 17052–17063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guisán-Ceinos, M.; Martín-Heras, V.; Tortosa, M. Regio- and Stereospecific Copper-Catalyzed Substitution Reaction of Propargylic Ammonium Salts with Aryl Grignard Reagents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 8448–8451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J. M.; Harwood, S. J.; Baran, P. S. Radical Retrosynthesis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 1807–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petzold, D.; Giedyk, M.; Chatterjee, A.; König, B. A Retrosynthetic Approach for Photocatalysis. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 2020, 1193–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.; Bera, T.; Dubey, G.; Saha, J.; Laha, J. K. Uses of K2S2O8 in Metal-Catalyzed and Metal-Free Oxidative Transformations. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 5085–5144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinz, A.; Bresien, J.; Breher, F.; Schulz, A. Heteroatom-Based Diradical(Oid)s. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 10468–10526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitre, S. P.; Overman, L. E. Strategic Use of Visible-Light Photoredox Catalysis in Natural Product Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 1717–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tian, Y.-M.; König, B. Energy- and Atom-Efficient Chemical Synthesis with Endergonic Photocatalysis. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2022, 6, 745–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novaes, L. F. T.; Liu, J.; Shen, Y.; Lu, L.; Meinhardt, J. M.; Lin, S. Electrocatalysis as an Enabling Technology for Organic Synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 7941–8002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rein, J.; Zacate, S. B.; Mao, K.; Lin, S. A Tutorial on Asymmetric Electrocatalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2023, 52, 8106–8125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Laha, J. K. Growing Utilization of Radical Chemistry in the Synthesis of Pharmaceuticals. Chem. Rec. 2023, 23, e202300207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, H. The Persistent Radical Effect: A Principle for Selective Radical Reactions and Living Radical Polymerizations. Chem. Rev. 2001, 101, 3581–3610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, P.; Li, W. Synthesis of BCP Nitriles Enabled by a Metallaphotoredox-Based Multi-Component Reaction. Chem Catal. 2023, 3, 100618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Boob, A. G.; Volk, M. J.; Liu, X.; Cui, H.; Zhao, H. Machine Learning-Enabled Retrobiosynthesis of Molecules. Nat. Catal. 2023, 6, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Song, J.; Feng, Z.; Liu, T.; Jia, L.; Yao, S.; Hou, T.; Song, M. Recent Advances in Deep Learning for Retrosynthesis. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2024, 14, e1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Xu, X.; Hsieh, C.-Y.; Ding, K.; Xu, H.; Xu, R.; Hou, T.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, H. Retrosynthesis Prediction with an Iterative String Editing Model. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Probst, D.; Manica, M.; Nana Teukam, Y. G.; Castrogiovanni, A.; Paratore, F.; Laino, T. Biocatalysed Synthesis Planning Using Data-Driven Learning. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnigan, W.; Hepworth, L. J.; Flitsch, S. L.; Turner, N. J. RetroBioCat as a Computer-Aided Synthesis Planning Tool for Biocatalytic Reactions and Cascades. Nat. Catal. 2021, 4, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesciullesi, G.; Schwaller, P.; Laino, T.; Reymond, J.-L. Transfer Learning Enables the Molecular Transformer to Predict Regio- and Stereoselective Reactions on Carbohydrates. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beliveau, S.; Ma, J. Recent Developments in AI and USPTO Open Data, 2022.

- Radestock, S. Optimising Chemical Information Workflows: Integrating Reaxys - Use Cases and Applications. J. Cheminform. 2013, 5, P39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaulton, A.; Hersey, A.; Nowotka, M.; Bento, A. P.; Chambers, J.; Mendez, D.; Mutowo, P.; Atkinson, F.; Bellis, L. J.; Cibrián-Uhalte, E.; Davies, M.; Dedman, N.; Karlsson, A.; Magariños, M. P.; Overington, J. P.; Papadatos, G.; Smit, I.; Leach, A. R. The ChEMBL Database in 2017. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D945–D954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somerville, A. N. SciFinder Scholar (by Chemical Abstracts Service). J. Chem. Educ. 1998, 75, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Han, J.; Su, A.; Qiao, H.; Zhang, C.; Tang, J.; Shen, X.; Sun, B.; Yu, W.; Zhai, S.; Wang, X.; Wu, Y.; Su, W.; Duan, H. Providing Direction for Mechanistic Inferences in Radical Cascade Cyclization Using a Transformer Model. Org. Chem. Front. 2022, 9, 2498–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Yu, W.; Luo, Y.; Liu, T.; Su, A. Developing Lead Compounds of eEF2K Inhibitors Using Ligand–Receptor Complex Structures. Processes 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Song, J.; Feng, Z.; Liu, T.; Jia, L.; Yao, S.; Wu, M.; Hou, T.; Song, M. Root-Aligned SMILES: A Tight Representation for Chemical Reaction Prediction. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 9023–9034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.-M.; Wang, J.-J.; Xiong, Y.; Wu, X. Visible-Light-Driven Multicomponent Reactions for the Versatile Synthesis of Thioamides by Radical Thiocarbamoylation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202409605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, G. A.; Pillitteri, S.; Van der Eycken, E. V.; You, S.-L.; Sharma, U. K. Multicomponent Reactions and Photo/Electrochemistry Join Forces: Atom Economy Meets Energy Efficiency. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 2313–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, A. F.; Moreira, R.; Rodrigues, T. Synthetic Organic Chemistry Driven by Artificial Intelligence. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2019, 3, 589–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, D.; Reymond, J.-L. Visualization of Very Large High-Dimensional Data Sets as Minimum Spanning Trees. J. Cheminform. 2020, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahy, W.; Plucinski, P.; Jover, J.; Frost, C. G. Ruthenium-Catalyzed O- to S-Alkyl Migration: A Pseudoreversible Barton–McCombie Pathway. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 10944–10948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemirovich, T.; Kostal, V.; Copko, J.; Schewe, H. C.; Boháčová, S.; Martinek, T.; Slanina, T.; Jungwirth, P. Bridging Electrochemistry and Photoelectron Spectroscopy in the Context of Birch Reduction: Detachment Energies and Redox Potentials of Electron, Dielectron, and Benzene Radical Anion in Liquid Ammonia. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 22093–22100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gant Kanegusuku, A. L.; Roizen, J. L. Recent Advances in Photoredox-Mediated Radical Conjugate Addition Reactions: An Expanding Toolkit for the Giese Reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 21116–21149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M. W.; Snyder, S. A. A Concise Total Synthesis of (+)-Scholarisine A Empowered by a Unique C–H Arylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 12964–12967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.-J.; Luo, M.-P.; Yuan, H.; Liu, G.-K.; Wang, S.-G. Photocatalytic Enantioselective Radical Cascade Multicomponent Minisci Reaction of β-Carbolines Using Diazo Compounds as Radical Precursors. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2402272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Jung, Y. Deep Retrosynthetic Reaction Prediction Using Local Reactivity and Global Attention. JACS Au 2021, 1, 1612–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwaller, P.; Laino, T.; Gaudin, T.; Bolgar, P.; Hunter, C. A.; Bekas, C.; Lee, A. A. Molecular Transformer: A Model for Uncertainty-Calibrated Chemical Reaction Prediction. ACS Cent. Sci. 2019, 5, 1572–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, R.; Dimitriadis, S.; He, J.; Bjerrum, E. J. Chemformer: A Pre-Trained Transformer for Computational Chemistry. Mach. Learn.: Sci. Technol. 2022, 3, 015022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhai, Y.; Gong, Z.; Duan, H.; She, Y.-B.; Yang, Y.-F.; Su, A. Transfer Learning across Different Chemical Domains: Virtual Screening of Organic Materials with Deep Learning Models Pretrained on Small Molecule and Chemical Reaction Data. J. Cheminform. 2024, 16, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; Lin, L.; Liu, B.; Xiao, Y.; Xiong, X. A Multi-Task Transfer Learning Method with Dictionary Learning. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2020, 191, 105233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- X. Fan; M. Gong; Z. Tang; Y. Wu. Deep Neural Message Passing With Hierarchical Layer Aggregation and Neighbor Normalization. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2022, 33, 7172–7184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tingle, B. I.; Tang, K. G.; Castanon, M.; Gutierrez, J. J.; Khurelbaatar, M.; Dandarchuluun, C.; Moroz, Y. S.; Irwin, J. J. ZINC-22─A Free Multi-Billion-Scale Database of Tangible Compounds for Ligand Discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023, 63, 1166–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Qiu, J.; Chen, G.; Liu, H.; Liao, B.; Hsieh, C.-Y.; Yao, X. RetroPrime: A Diverse, Plausible and Transformer-Based Method for Single-Step Retrosynthesis Predictions. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 420, 129845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, D. P.; McCorkindale, W.; Lee, A. A. Quantitative Interpretation Explains Machine Learning Models for Chemical Reaction Prediction and Uncovers Bias. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novaes, L. F. T.; Liu, J.; Shen, Y.; Lu, L.; Meinhardt, J. M.; Lin, S. Electrocatalysis as an Enabling Technology for Organic Synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 7941–8002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Su, W.; Yu, J. Generation of Aryl Radicals from in Situ Activated Homolytic Scission: Driving Radical Reactions by Ball Milling. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 4557–4565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Ward, R. M.; Schomaker, J. M. Mechanistic Aspects and Synthetic Applications of Radical Additions to Allenes. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 12422–12490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabor Gozzi, G.; Bouaziz, Z.; Winter, E.; Daflon-Yunes, N.; Aichele, D.; Nacereddine, A.; Marminon, C.; Valdameri, G.; Zeinyeh, W.; Bollacke, A.; Guillon, J.; Lacoudre, A.; Pinaud, N.; Cadena, S. M.; Jose, J.; Le Borgne, M.; Di Pietro, A. Converting Potent Indeno[1,2-b]Indole Inhibitors of Protein Kinase CK2 into Selective Inhibitors of the Breast Cancer Resistance Protein ABCG2. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Mohamed, R. K.; Manoharan, M.; Phan, H.; Alabugin, I. V. Drawing from a Pool of Radicals for the Design of Selective Enyne Cyclizations. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 5650–5653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takase, M.; Narita, T.; Fujita, W.; Asano, M. S.; Nishinaga, T.; Benten, H.; Yoza, K.; Müllen, K. Pyrrole-Fused Azacoronene Family: The Influence of Replacement with Dialkoxybenzenes on the Optical and Electronic Properties in Neutral and Oxidized States. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 8031–8040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.-W.; Mao, Z.-Y.; Song, J.; Xu, H.-C. Electrochemical Synthesis of Polycyclic N-Heteroaromatics through Cascade Radical Cyclization of Diynes. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 5810–5813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monfette, S.; Turner, Z. R.; Semproni, S. P.; Chirik, P. J. Enantiopure C1-Symmetric Bis(Imino)Pyridine Cobalt Complexes for Asymmetric Alkene Hydrogenation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 4561–4564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Bedi, D.; Cheng, L.; Unruh, D. K.; Li, G.; Findlater, M. Cobalt(II)-Catalyzed Stereoselective Olefin Isomerization: Facile Access to Acyclic Trisubstituted Alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 8910–8917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yang, X.; Wu, P.; Yu, Z. Photoredox-Catalyzed C–H Arylation of Internal Alkenes to Tetrasubstituted Alkenes: Synthesis of Tamoxifen. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 6248–6251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, S. R.; Ebrahimzadeh, M. A. O-Glycoside Quercetin Derivatives: Biological Activities, Mechanisms of Action, and Structure–Activity Relationship for Drug Design, a Review. Phytother. Res. 2022, 36, 778–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguchi, H.; Hojo, K.; Suginome, M. Boron-Masking Strategy for the Selective Synthesis of Oligoarenes via Iterative Suzuki−Miyaura Coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 758–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, J. C.; Gui, J.; Yabe, Y.; Pan, C.-M.; Baran, P. S. Functionalized Olefin Cross-Coupling to Construct Carbon–Carbon Bonds. Nature 2014, 516, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).