Submitted:

14 October 2025

Posted:

15 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- An integrated overview of all relevant works proposing metaverse trust/reputation mechanisms. We summarize each scheme’s design, including token-based vs. score-based approaches, and highlight how they handle threats like Sybil attacks, collusion, whitewashing, etc.

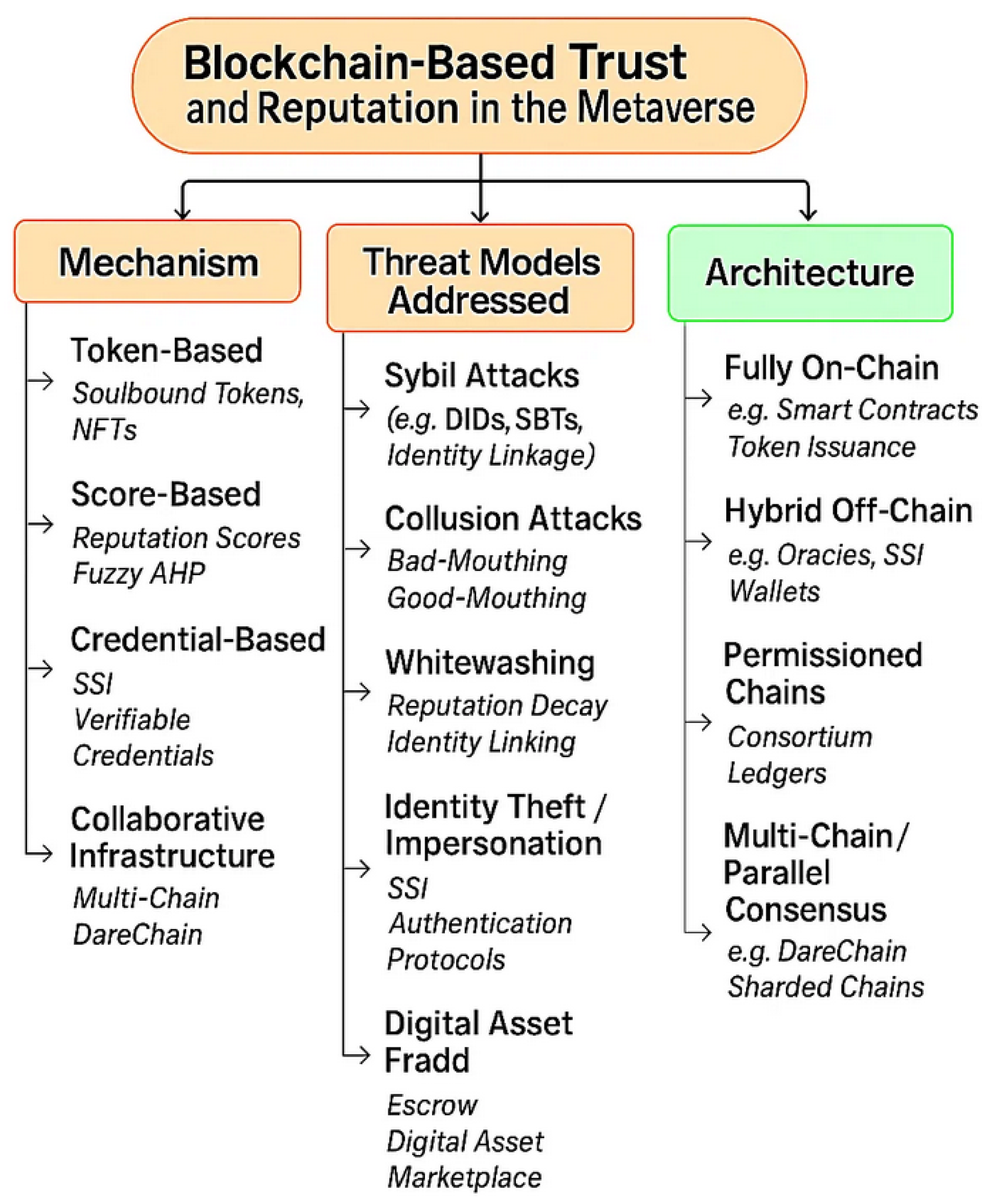

- A taxonomy classifying these schemes along multiple dimensions – the underlying mechanism, the threat models addressed, and the architecture.

- A comparative evaluation of the surveyed schemes on key criteria including security, scalability, user privacy, and interoperability. We include comparative tables and charts that compile quantitative results reported in the literature. This analysis reveals trade-offs between approaches.

- An outlook on unresolved issues and research directions for metaverse trust systems. We identify gaps such as cross-platform reputation portability, privacy-preserving reputation computations, standardizing trust tokens/credentials, decentralized governance of reputation, and real-time trust updates. We illustrate these challenges and link each to potential solutions or ongoing efforts.

2. Blockchain Integration in the Metaverse

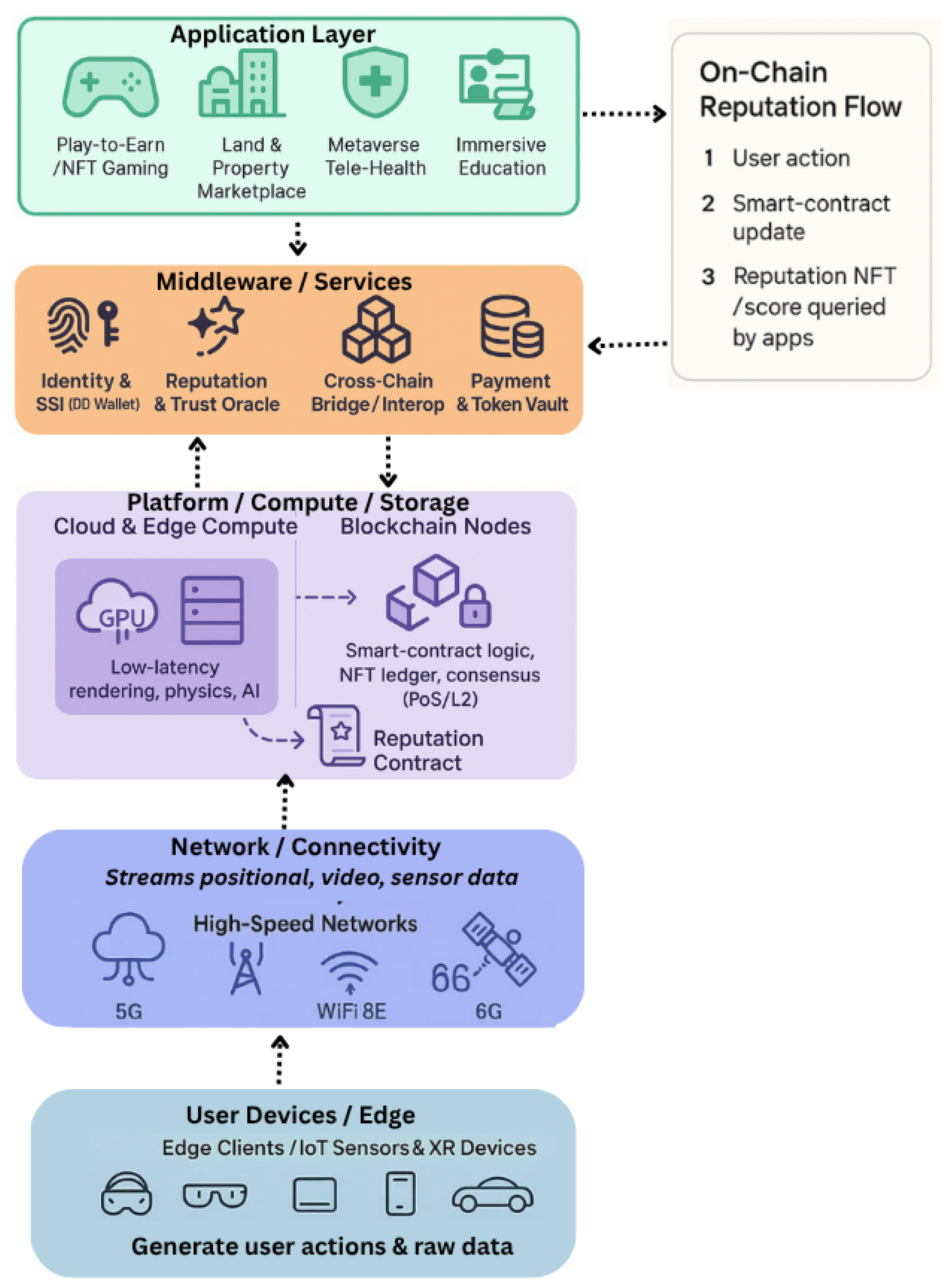

2.1. Architecture of Blockchain-Enabled Metaverse

2.2. Current Applications and Case Studies

- Gaming Metaverses: Many metaverse games are built on blockchain[20]. Decentraland is a virtual world where land plots are ERC-721 NFTs on Ethereum. Each “LAND” is an NFT minted by burning the MANA token [21]. Ownership is fully on-chain, and a decentralized marketplace allows buying/selling parcels. Sandbox is another voxel-based metaverse on Ethereum: users create 3D objects (via VoxEdit) as NFTs stored on IPFS, and trade them in a marketplace using the SAND ERC-20 token. The Sandbox also uses The Graph (an L2 indexer) for scalability. The Axie Infinity ecosystem (creaturebattling game) uses the Ronin sidechain to reduce Ethereum gas fees; players earn NFTs (Axies) and utility tokens (AXS, SLP) through gameplay. These platforms demonstrate blockchain’s value in games: guaranteeing true digital ownership, enabling player-driven economies, and securing scarce virtual goods[22].

- Virtual Real Estate: Metaverse worlds often have properties that mirror real estate [23]. Gadekallu et al. note that metaverse virtual land is treated as a scarce asset: “virtual land…is offered at auction and traded as NFTs” [21]. Platforms like Decentraland and The Sandbox regularly auction parcels, and secondary sales occur via smart-contract markets [2,3]. This NFT-based ownership provides provenance and transferability of virtual real estate. Companies are exploring commercial use of virtual land (e.g. virtual offices, retail in metaverse malls), all leveraging blockchain for transparent transactions.

- Healthcare: Blockchain in metaverse-enabled healthcare can secure patient data and digital health assets. For instance, patient records or VR-based therapy sessions could be anchored on a blockchain to ensure immutability and access control. Surveys by Wang et al. highlight that blockchain “ensures secure, immutable record-keeping” and gives patients control via cryptographic keys [24]. Ali et al. propose a metaverse health platform with Explainable AI where blockchain “provides data security for patients while enabling transparency, traceability, and immutability” of medical information [25]. Use cases include virtual hospitals, telehealth with encrypted records, and medical research data sharing under patient consent. By integrating blockchain, healthcare metaverses can protect privacy through encryption and access logs and comply with data regulations.

- Education: The educational metaverse benefits from blockchain by validating credentials and enabling novel learning economies. Karunarathne et al. observe that blockchain-metaverse integration revolutionizes education by “securely storing student records” and enabling immersive, virtual learning experiences [26]. For example, universities could issue diplomas or certificates as verifiable blockchain tokens within an educational VR world. Decentralized IDs on blockchain could manage access to virtual labs or collaborative simulations. Projects like Learning Economy and blockchain-based MOOC platforms already explore these ideas. Overall, blockchain can support trust in academic records and micro-credentialing in virtual campuses.

- Other Domains: Blockchain-metaverse applications also appear in industry and commerce. In supply-chain-oriented metaverses, digital twins of factories can be anchored to blockchains for traceability. In retail, brands are opening virtual stores on metaverse platforms, selling blockchain certified goods (e.g. luxury NFTs) to users. While beyond the four focal domains, these cases underline blockchain’s broad metaverse potential.

2.3. Benefits of Blockchain in Metaverse

- Data Integrity and Security: By design, blockchain provides tamper-resistant records. Transactions and asset histories are immutable and replicated across nodes, ensuring that no data can be altered without consensus . For sensitive data (medical records, identity details), blockchain encryption and consensus give users “complete control of their data”. Decentralized storage also reduces single points of failure.

- Trust and Transparency: In open metaverse economies, trust among participants is crucial. Smart contracts enforce rules transparently (e.g. fair auctions, loot generation) without needing intermediaries. As Ali et al. note, blockchain enables transparency and traceability in healthcare transactions , and more generally assures all stakeholders of system integrity. Public ledgers let anyone audit digital asset provenance.

- Digital Ownership (NFTs and Tokens): Blockchain makes digital scarcity possible. Non-fungible tokens (NFTs) represent unique virtual items (land, art, avatars). Users have provable ownership and can trade these assets on-chain . This creates novel economic opportunities: for example, players in The Sandbox truly own and can sell their creations, rather than renting them from a company. Tokenized economies (ERC-20/721 tokens) allow in-world currency (e.g. MANA, SAND) and novel finance (staking, DAOs) as part of the metaverse.

- Decentralization and Resilience: Unlike centralized servers, blockchain-based metaverses do not rely on a single authority. This can improve uptime and censorship-resistance; virtual property rights persist even if one company shuts down. Interoperability protocols (cross-chain bridges) can allow users to move assets between different metaverses . Decentralization also means collaborative governance (DAOs) can emerge for virtual communities.

- Automated Enforcement (Smart Contracts): Business logic on blockchain via smart contracts automates complex interactions. For example, royalties on NFT resale can be coded so creators always earn a percentage. In education, smart contracts could automatically unlock course content upon payment or credential verification. These programmable agreements reduce overhead and ensure rules are executed as intended.

3. PRISMA Flow of Study Selection

| PRISMA stage | Records (n) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Identification: total records from all databases | 1758 | IEEE, ACM, ScienceDirect, Scopus (2020–2025); search: blockchain & metaverse & (trust OR reputation) |

| Duplicates removed | 828 | ∼50% overlap across databases |

| Records after de-duplication (screened) | 930 | Title/abstract screening pool |

| Records excluded at title/abstract stage | 820 | Off-topic, language, or format filters |

| Full-text articles assessed for eligibility | 110 | Downloaded and reviewed in full |

| Full-text articles excluded | 87 | No trust mechanism; not metaverse-relevant; not blockchain-relevant; insufficient detail; non–peer-reviewed; duplicate concept |

| Studies included in qualitative synthesis | 23 | Papers analyzed in Tables 1–4 |

4. Related Work

4.1. Blockchain-Enabled Reputation Systems for Metaverse Platforms

4.2. Self-Sovereign Identity and Credential-Based Trust

4.3. Trust Architectures and Specialized Metaverse Domains

5. Taxonomy of Metaverse Trust Schemes

- Token-Based Mechanisms: These use crypto-tokens to represent trust or reputation. Reputation tokens may be fungible or non-fungible. Soulbound Tokens (SBTs) are a prominent example – an SBT is essentially a tokenized credential or badge that signifies some trusted attribute of a user and cannot be transferred [39]. Token-based schemes lean on blockchain’s strength in handling assets: trust is embodied as an asset owned by the user. This category typically excels in portability and Sybil-resistance. However, purely token-based approaches may struggle with granularity – a token often represents a coarse achievement rather than a nuanced behavior history – and with privacy, since on-chain tokens are publicly visible. For example, a user’s collection of reputation NFTs or SBTs can signal their trust level across the metaverse, but it also means anyone can inspect and correlate those credentials. Token-based designs must balance these trade-offs, and in practice they are often combined with other methods e.g., using on-chain tokens to summarize off-chain scores.

- Score-Based Mechanisms: These compute a numerical reputation score for each user or entity, often through algorithms aggregating feedback over time. The score might be stored on-chain or off-chain with secure checkpoints on-chain. Score-based schemes can incorporate complex logic to reflect trust dynamics [28,29]. They offer flexibility and fine-grained updates. Many are designed to address collusion and whitewashing through algorithmic defenses. On the flip side, maintaining scores often requires continuous monitoring and computation, raising scalability concerns in very large systems if every interaction triggers a score update.

- Credential-Based Mechanisms: These approaches leverage verifiable identity credentials and attributes as the basis for trust. Rather than (or in addition to) tracking behavior, a user’s reputation comes from what they are (their credentials) — for example, possessing a valid ID, a proven skill certificate, or endorsements from trusted parties. Self-Sovereign Identity (SSI) frameworks fall in this category: users have decentralized identifiers (DIDs) and present verifiable credentials to establish trust in anonymity-preserving ways. Credential-based trust is often implemented via tokens that represent credentials (in fact, SBTs can be seen as one form of credential token), or through on-chain registries of verified attributes. Mebrahtom et al. [42] demonstrate this approach by integrating a decentralized identity wallet with an on-chain registry; participants must provide authentic credentials e.g., proof of a verified real-world identity or qualification, which are then tokenized or referenced on-chain. This requirement raises the bar for attackers—Sybil attacks are mitigated because each identity must have unique, verifiable attributes, and impersonation is harder if reputation is tied to cryptographic proofs of identity. Song et al.[40] similarly blend credential-based trust with behavior scoring: in their fuzzy AHP-based reputation mechanism, factors like the presence of certain SBT badges or verified traits of an avatar are weighted alongside that avatar’s actions. Credential-based schemes thus anchor trust to confirmed qualities of the user. They can provide strong identity authenticity and initial trust bootstrap, at the cost of requiring robust privacy safeguards and interoperability. Ongoing efforts in standards e.g., decentralized identity and Trust-over-IP models aim to ensure that credential-based trust credentials can be widely accepted across different metaverse platforms without compromising user privacy.

- Collaborative Infrastructure Approaches: Some emerging solutions build trust into the infrastructure of the metaverse itself, rather than focusing on a single metric or token. We term these collaborative infrastructure mechanisms: they propose a network architecture where multiple blockchain networks or modules work together to uphold trust. The idea is to support trust and reputation as a cross-platform service, enabling various metaverse domains to collaborate in sharing trust data securely. DareChain [46] is an example of this category – a blockchain-based trusted collaborative network infrastructure for the metaverse. DareChain introduces a collaborative-worker multi-chain system in which a main “collaborative” chain coordinates with multiple specialized side-chains to manage one-to-one mapping of physical entities to digital avatars, record their interactions, and enforce trust rules across different applications. By using a layered smart contract model and a new consensus algorithm, this infrastructure can handle large-scale interactions in parallel while ensuring consistency and security. The collaborative infrastructure approach effectively blurs mechanism and architecture: trust is maintained through the architecture’s design. Such designs address challenges like interoperability and scalability of trust – for instance, DareChain enables cross-chain queries and transactions so that reputation or asset data from one virtual world can be trusted in another, creating a unified trust fabric. This approach is still nascent, but it points toward metaverse-scale trust systems where the network of blockchains itself provides core trust services including identity validation, asset provenance, secure transaction processing, for any number of higher-level applications. It complements the other mechanism types by ensuring that trust is holistically supported at the infrastructure level, an approach crucial for an interconnected future metaverse.

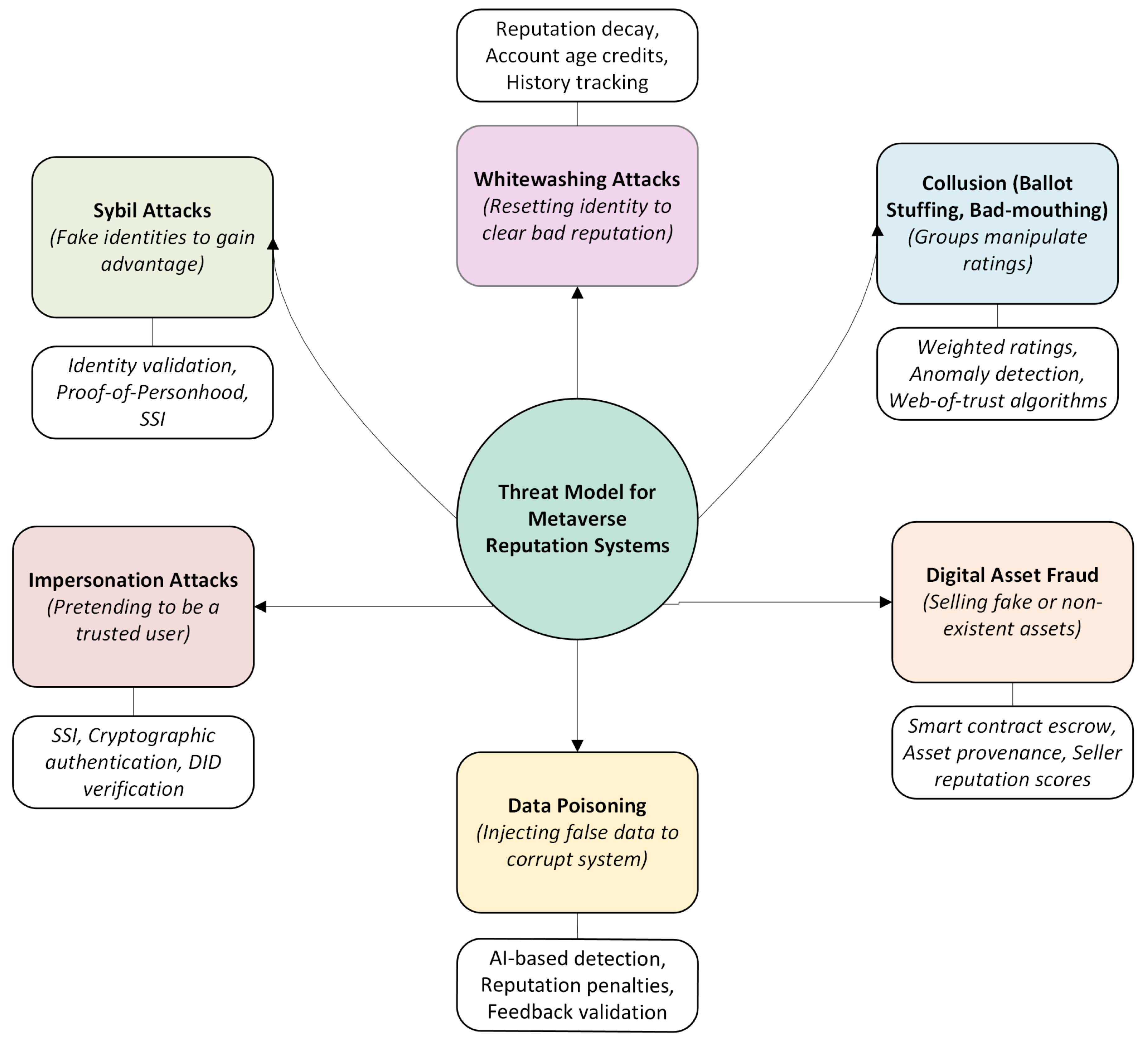

- Sybil Attacks: A Sybil attack is when one user creates many fake identities to exploit the system e.g., to gain extra rewards or distort reputation scores [57]. Solutions typically aim to limit the ability to spawn endless credible identities. Approaches based on unique identity or proof-of-personhood directly mitigate Sybils. For example, requiring users to register a decentralized identity (DID) backed by some real-world verification, or issuing a non-transferable token per human as in SBTs, makes it hard for one person to manage many identities without detection [39]. Credential-based schemes naturally help here: if each participant must provide verifiable attributes or undergo an identity attestations process [42] , Sybil nodes are thwarted because an attacker cannot easily fabricate multiple valid credentials. Some score-based systems also indirectly limit Sybils by design—new identities start with neutral or low reputation and must invest time and good behavior to become influential, so a swarm of fresh Sybil bots remains ineffective until they earn trust over many interactions. In Figure 2, approaches like SSI-based identity frameworks and SBT credential systems are grouped under Sybil-resistant solutions, as they raise the cost of obtaining multiple trustworthy identities in an otherwise anonymous metaverse [41].

- Collusion Attacks: Collusion involves attackers working together to deceive the reputation system. This can take the form of bad-mouthing where a group of malicious users unfairly low-rating a target to undermine their reputation or ballot-stuffing/good-mouthing where a group conspiring to boost each other’s trust with false positive feedback[58]. Decentralized reputation schemes use various techniques to defend against collusion. Many algorithms incorporate statistical detection of anomalous rating patterns, for instance, spotting if a cluster of avatars always rate each other positively or always down-vote a particular victim. Others leverage the web-of-trust concept: they weigh feedback by the rater’s own reputation or relationship to the ratee, so a set of low-reputation newcomers colluding will have minimal influence. Some solutions use ground truth anchors by cross-checking ratings against actual outcomes – e.g., if users rate a seller as honest but all of the seller’s transactions are disputed, the system can flag those ratings as likely collusive. Blockchain can assist by transparently logging all feedback, making it easier to audit for collusion after the fact. Awan et al.[27] incorporate reputation-driven voting schemes to filter out dishonest feedback and reportedly detect coordinated rating attacks with high accuracy. In Figure 2, we list Awan’s trust management framework under collusion defenses, since it explicitly demonstrated the ability to identify both bad-mouthing and ballot-stuffing attacks [27]. Generally, combining algorithmic filters to identify suspicious rating behavior with trust weighting forms the core of collusion resistance in these systems.

- Whitewashing Attacks: In a whitewashing attack, a user who has accumulated a bad reputation simply discards that identity and re-enters the system with a brand new identity [59]. This is a classic challenge in reputation systems, exacerbated in open metaverse environments where creating a new avatar can be trivial. Countermeasures focus on making reputation sticky to users or imposing penalties for starting over. One approach is identity linkage: even if a user switches accounts, the system tries to link the new identity to the old so that the negative history follows them [14]. Another common defense is reputation decay and time-based weighting: recent behavior counts more than old behavior, and longdormant identities lose reputation strength. This means an attacker cannot simply shelf an identity until community memory fades; by the time they return, their prior reputation has decayed, and they must prove themselves again. Some systems also issue “age credits” – trust is partly a function of how long an identity has been around and active. Whitewashing is thus discouraged because a fresh identity lacks longevity-based trust and any attempt to rapidly build high reputation will be tempered by cautious algorithms. Awan et al.[27] address whitewashing by tracking entities’ history even across join/leave cycles and using dynamic reputation aging; their prototype caught nearly all whitewashing attempts in simulations by detecting when a supposedly “new” node behaved too similarly to a recently departed bad actor. Similarly, Song et al. [40] include a decay factor in their fuzzy reputation model so that users cannot regain full trust instantly after rejoining. In Figure 2, schemes with such features are categorized under the whitewashing mitigation group. By ensuring that reputation cannot be fully reset or quickly rebuilt, these systems maintain accountability over time.

- Identity Theft/Impersonation: Beyond fake accounts, a serious threat is when an attacker hijacks or mimics a real user’s identity to exploit their established trust. In the metaverse, this might involve stealing private keys to an avatar, or creating a lookalike avatar/profile to fool others [60]. Blockchain-based trust systems tackle impersonation primarily through strong authentication and secure identity management. If trust is tied to cryptographic identities that are controlled by users, an attacker cannot impersonate someone without also compromising their private key. This drives the adoption of SSI authentication protocols in the metaverse. For example, Patwe et al. [41] propose a blockchain-enabled interoperable authentication scheme where each user is uniquely identified in the physical world and linked to their avatars. Their scheme uses cryptographic challenges and blockchain records to ensure that when an avatar tries to interact across platforms, it proves that it has the correct private keys and credentials. This prevents an impostor from masquerading as someone else’s avatar because they would fail the authentication checks without the victim’s keys. More generally, systems that use verified credentials inherently resist impersonation: an attacker trying to pose as, say, a certified doctor in a metaverse clinic would need that doctor’s verifiable credential, which is digitally signed and nearly impossible to forge without issuing authority. Mebrahtom et al. [42] emphasize identity authenticity in their reputation design: By requiring that each participant’s identity be validated and bound to their reputation records, they close the door to opportunistic identity theft. In summary, by binding reputation to secure digital identities and requiring cryptographic proof of identity claims, these trust frameworks greatly reduce the risk of impersonation. Users may also be alerted via blockchain logs if an identity key is changed or used in suspicious ways, adding transparency that helps detect account takeovers in a decentralized manner.

- Digital Asset Fraud: Metaverse ecosystems feature marketplaces for digital assets that introduce risks of fraud in transactions. Examples include sellers deceiving buyers with counterfeit or non-existent assets, or buyers defaulting after receiving an item. Trust mechanisms have evolved to address these transactional fraud scenarios. A straightforward approach is the use of smart contract escrow services: When two parties trade a digital asset, a blockchain smart contract can hold the buyer’s payment in escrow and only release it to the seller once the asset is verifiably transferred to the buyer’s ownership. This trustless escrow removes the need to trust the counterparty’s promise, as the contract ensures a fair exchange or refunds the buyer if the conditions are not met. Decentralized marketplaces like OpenSea [61] are beginning to use such mechanisms to protect against fraud in NFT trades. Another vital component is provenance tracking. Because blockchain inherently records ownership history, buyers can check the chain of custody of a digital asset to verify its authenticity and that the seller has rightful ownership. This helps prevent the sale of forged or stolen virtual goods. Reputation systems can layer on top of this by assigning trust scores to asset sellers and buyers based on their past transaction behavior. For example, a seller with many successful, dispute-free sales will develop a high reputation, while a seller involved in prior frauds or transaction failures will be flagged with a low score. Future trust frameworks may integrate these reputations directly into marketplace smart contracts—only allowing high-reputation sellers for certain high-value trades, or requiring extra collateral from a low-reputation participant. By linking reputation events with actual on-chain transactions, the system can also filter out false feedback. Initial research indicates that users are more willing to engage in metaverse commerce when they see such protections in place. In fact, a recent study found that trust in the platform or brand remains a decisive factor for users’ purchase intentions in the metaverse, despite the presence of “trustless” blockchain tech [51]. This underscores the need for robust anti-fraud measures. In Figure 2, we illustrate digital asset fraud countermeasures as a distinct category of threat response. Together, these measures ensure that digital asset transactions can be conducted with confidence in their fairness and validity [41].

- Fully On-Chain: These systems execute reputation logic entirely on a blockchain. On-chain architectures maximize transparency and tamper-resistance – all actions affecting trust are recorded on the ledger for anyone to audit. For example, a smart contract based rating system might log every feedback and compute trust scores within contract code. The downside is cost and performance: on-chain operations incur gas fees and latency, and complex computations may be impractical on-chain. Nonetheless, some proposals strive for on-chain implementations. Mebrahtom et al.’s [42] cross-platform trust uses Ethereum contracts for verification. If blockchain scalability improves (sharding, Layer-2), on-chain trust management might become more viable.

- Hybrid Off-Chain: The majority of practical designs take a hybrid approach, where heavy computation is done off-chain and the blockchain is used as an anchor or arbiter of trust data. In these architectures, intensive tasks happen off-chain — for example, on a set of decentralized oracles, on cloud servers, or within user devices— and only the resulting trust indicators or cryptographic proofs are posted to the blockchain [63]. This offloads work to where it can be done faster and cheaper, while still leveraging blockchain to secure and share the outcomes. Xu et al. [14] exemplify this with their “trustless architecture”: they compute trust within local groups and then use a blockchain layer to merely connect groups and enforce decisions. The blockchain in their design triggers On-Demand Trusted Computing Environments and records group trust levels, but the heavy lifting of calculating those trust levels is done off-chain within each group. Similarly, Song et al. [40] envision their fuzzy reputation algorithm running on a network of nodes that periodically write updated scores or proofs to an on-chain registry. The hybrid design aims to achieve scalability while still maintaining verifiability. A risk in hybrid models is the trust one must place in the off-chain components, if those nodes collude or malfunction, they could feed incorrect data on-chain. To mitigate this, many solutions decentralize the off-chain layer too: for instance, use multiple independent oracles and require consensus among them before accepting a trust update, or use cryptographic techniques such as zero-knowledge proofs, secure enclaves, to prove that offchain calculations were done correctly. In our classification, a number of schemes fall under “hybrid”: they leverage blockchain for what it’s good at without letting it become a bottleneck. This approach is generally the most practical for today’s metaverse scale, and indeed most current implementations, even in Web2, like centralized reputation services, have an analogue of off-chain processing with on-chain anchoring now being introduced for added transparency.

- Permissioned Chains: While many metaverse trust systems assume a public, permissionless blockchain environment, some are built on permissioned (consortium or private) blockchains. In permissioned architectures, only approved entities can participate in validating transactions and updating the ledger [64]. This model can be attractive for enterprise metaverse applications or specific domains where participants are vetted and the volume of interactions is high. The trust mechanism itself might still be token-based or score-based, but it runs on a closed blockchain network with controlled access. The benefits include higher throughput, lower and more predictable transaction costs, and the ability to enforce organizational governance rules on reputation data. For example, the Blockchain Trust and Reputation Model (BTRM) was prototyped on Hyperledger Fabric, a permissioned ledger [29]. In that system, IoT devices in a controlled environment share a Fabric blockchain to store and update reputations; the permissioned setup ensures only authorized devices and servers partake in consensus, which improves performance and privacy. Similarly, one could imagine a consortium of metaverse platforms forming a permissioned chain to exchange reputation scores among themselves without exposing data on a public network. The trade-off is reduced decentralization and transparency to the wider public – users have to trust the consortium governance. Our taxonomy explicitly includes this dimension now: some solutions operate on consortium ledgers, which we classify under permissioned chain architecture. It’s worth noting that permissioned vs. permissionless is often orthogonal to the mechanism; a token-based or credential-based scheme could be deployed on either type of chain depending on the context. In any case, permissioned chain approaches show that blockchain-based trust can be adapted to closed-world settings where openness is traded for performance or regulatory compliance.

- Multi-Chain/Parallel Consensus: As metaverse applications scale, a single blockchain might become a bottleneck for trust management. New architectures therefore explore multi-chain or sharded designs, where the workload is distributed across multiple ledgers running in parallel [62]. In such designs, different aspects of trust might be handled on different chains, or multiple chains might each serve a subset of users and then interoperate. This category overlaps with the earlier “collaborative infrastructure” concept and emphasizes the architectural aspect of using several blockchains together. Xia et al. [30] present a reputation-aided consensus mechanism for a multi-chain metaverse: in their approach, each blockchain shard maintains local reputations and prioritizes reputable nodes for block production, and they introduce a way to carry a user’s trust score from one chain to another so that an avatar doesn’t have to rebuild trust from scratch on each world. This not only speeds up consensus on each chain but also addresses interoperability by linking trust across platforms. Another example is the aforementioned DareChain architecture [46], which explicitly uses a collaborative multi-chain system: a main chain coordinates global state and identity, while numerous worker chains handle specific domains or regions of the metaverse, all following a unified trust protocol. By running many chains in parallel, DareChain achieves high throughput for trust-related transactions and can isolate certain operations to specific chains. The multi-chain approach inherently requires mechanisms for cross-chain communication and consistency — e.g., relay protocols or bridges that carry reputation information from one chain to another, and consensus algorithms that can scale out. The advantage is scalability and specialization: one chain’s congestion or attacks need not bring down the whole system, and each chain can be optimized for a particular trust context while still contributing to an overall trust picture. The challenge is ensuring that these parallel chains maintain a coherent global trust view and that no inconsistencies or exploits arise when moving assets or reputations between chains. As blockchain technology advances, we expect more metaverse trust solutions to adopt multi-chain architectures or layer-2 networks to meet the massive scale of a fully immersive digital universe.

6. Benchmark Analysis

6.1. Privacy and Data Governance

6.2. Interoperability and Standardization

6.3. Scalability and Performance

| Scheme | Scalability Strategy | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Awan et al. [27] | Decentralized trust decisions; trust-weighted consensus reduces agreement steps so reputable nodes drive consensus. Reputation monitoring avoids expensive recovery from misbehavior. | Processes 2000 nodes in 340 ms vs 520 ms baseline ( faster). Integrating trust improved latency; near-linear scaling; graceful degradation; better throughput at scale. |

| Tu et al. [29] — BTRM | Dynamic updates and permissioned chain. Not every interaction triggers on-chain tx; reputation updates are batched/periodic. Uses Fabric’s high TPS; idle users pruned. | On Fabric, practical runtimes for reputation updates; scaled to large IoT pools without linear cost growth; low latency by limiting heavy computation frequency. |

| Xu et al. [14] | Metaverse partitioned into trust groups; computations scale per group. Edge compute for local loads; blockchain coordinates groups; minimizes on-chain ops; groups subdividable. | Conceptual (no numerics). Qualitatively scales: new users add load only to their group. Hypergraph trust supports incremental growth; avoids single bottlenecks. |

| Li et al. [46] — DareChain | Collaborative multi-chain: parallel chains (shards) handle different interactions. Consensus scales with chains/nodes; layered contracts distribute load. | High throughput via parallelism; overall TPS grows nearly linearly with added chains; low per-tx latency as each shard handles smaller load; maintains security/privacy. |

| Mebrahtom et al. [42] | Off-chain interactions with on-chain verification. SSI setup amortized; no redundant re-checks per login; blockchain can be fast layer-2 backend. | Prototype on Ethereum: . Qualitatively supports thousands of logins/checks concurrently. |

| Patwe et al. [41] | SSI-based hybrid. Auth via off-chain wallet interactions, on-chain validation. Heavy compute peer-to-peer/client-side; chain logs events/revocations; no central auth server. | Measured auth ; comms 1256 bits. Lightweight enough for real-time VR login. Throughput limited by base chain; modern chains handle 100s–1000s TPS. |

| Kuru et al. [49] | Federated learning on device data; distributes compute across devices/edge. Blockchain stores checkpoints, not every interaction. | Early-stage concept. Scales with device count; per-user (tens of ms for light models). |

| Xia et al. [30] | Lightweight consensus reduces messaging; reputation streamlines leader election. Multi-chain design: shards handle regions/contexts in parallel. | Simulations show higher throughput per chain; filtering low-rep nodes may reduce consensus from O(n) to O(m), ; capacity increases with more shards. |

| Liu et al. [62] | Permissioned PBFT with trust scores. Offloads reputation off-chain/in parallel; PBFT uses weights; dynamic node set. | Simulations: dozens of vehicles per region with sub-second blocks. PBFT efficient with filtering; large scale via partitioned regional chains. |

| Lotfi et al. [45] | Localized feedback loops; each region computes trust locally; regions run in parallel; incentive throttling; if on blockchain, use regional permissioned chains or DAG. | Dozens to few hundred vehicles in real time. For millions, hierarchical clusters; near-linear scale by deploying more servers; needs fast/sharded chains. |

| Truong et al. [36] | On-chain escrow contracts; every trade hits the chain. Batch on high-TPS networks; reputation updated per trade/audit. | Secure trading focus. Typical L1 escrow: few hundred ms. Thousands/sec possible on L2. Reputation writes are small; scales with chain improvements. |

| Song et al. [40] | Hierarchical fuzzy trust: split factors, compute in parallel off-chain, aggregate; updates periodic or on significant change. | No explicit metrics (prototype). Off-chain heavy lifting; on-chain only final scores/proofs. Supports very large user sets with distributed compute. |

| Soulbound Tokens [39] | Static reputational credentials; mint/read/store are efficient; updates infrequent; batch issuance supported. | Seen at NFT scale (millions of tokens). L2/sidechains give high throughput/low cost. Internet-scale feasible; per-user data small. |

7. Open Challenges and Future Directions

7.1. Cross-Platform Reputation Portability:

7.2. Privacy-Preserving Reputation:

7.3. Reputation Governance and Trust Constitution:

7.4. Dynamic and Real-Time Reputation:

7.5. Sybil Resistance vs. Openness:

7.6. Scalability to Massive Scale:

7.7. User Experience and Transparency:

7.8. Unified Evaluation and Collaboration:

8. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

References

- Aygun, R.C.; Vural, T.; Zhang, L. Blockchain’s Role in Metaverse Trust and Transactions. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Metaverse Computing, Networking and Applications (MetaCom), 2023, pp. 786–792. [CrossRef]

- Decentraland Foundation. Decentraland Official Website, 2025. Accessed: 2025-06-17.

- The Sandbox Team. The Sandbox Official Website, 2025. Accessed: 2025-06-17.

- Metaverse Standards Forum. Unified Reputation Management for Metaverse Entities. Technical Report Version 1.0, Metaverse Standards Forum, 2025. Approved for Public Distribution; Last update: May 12, 2025.

- Ghosh, A.; Hassija, V.; Chamola, V.; El Saddik, A.; et al. A Survey on Decentralized Metaverse using Blockchain and Web 3.0 technologies, Applications, and more. IEEE Access 2024.

- Gadekallu, T.R.; Huynh-The, T.; Wang, W.; Yenduri, G.; Ranaweera, P.; Pham, Q.V.; da Costa, D.B.; Liyanage, M. Blockchain for the metaverse: A review. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.09738 2022.

- Qayyum, A.; Butt, M.A.; Ali, H.; Usman, M.; Halabi, O.; Al-Fuqaha, A.; Abbasi, Q.H.; Imran, M.A.; Qadir, J. Secure and Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence-extended Reality (AI-XR) for Metaverses 2024. 56. [CrossRef]

- Sathya, A.R. Blockchain: The Foundation of Trust in Metaverse; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2023; pp. 117–129. [CrossRef]

- Jim, J.R.; Hosain, M.T.; Mridha, M.F.; Kabir, M.M.; Shin, J. Toward Trustworthy Metaverse: Advancements and Challenges. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 118318–118347. [CrossRef]

- Truong, V.T.; Le, L.; Niyato, D. Blockchain meets metaverse and digital asset management: A comprehensive survey. Ieee Access 2023, 11, 26258–26288.

- Pattanayak, S.; Ramkumar, M.; Gupta, S. Blockchain Empowered Metaverse: Enhancing User Engagement through Trust, Collaboration, Authenticity, And Governance. Information Systems Frontiers 2025. [CrossRef]

- Perey, C. Interoperability is a Fundamental Requirement for the Open Metaverse. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Symposium on Emerging Metaverse (ISEMV). IEEE, 2024, pp. 21–24.

- Al-kfairy, M.; Alomari, A.; Al-Bashayreh, M.; Alfandi, O.; Altaee, M.; Tubishat, M. A Review of the Factors Influencing Users’ Perception of Metaverse Security and Trust. In Proceedings of the 2023 Tenth International Conference on Social Networks Analysis, Management and Security (SNAMS), 2023, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Guo, Y.; Hu, Q.; Xiong, Z.; Yu, D.; Cheng, X. A trustless architecture of blockchain-enabled metaverse. High-Confidence Computing 2023, 3, 100088. [CrossRef]

- Sky Mavis. Axie Infinity, 2024. Accessed: 2024-07-03.

- Sky Mavis. Ronin Blockchain, 2024. Accessed: 2024-07-03.

- Dapper Labs. Flow Blockchain. https://flow.com/, 2024. Accessed: 2025-07-03.

- Immutable. What is Immutable X? https://docs.immutable.com/x/what-is-immutablex/, 2024. Accessed: 2025-07-03.

- Mourtzis, D.; Angelopoulos, J.; Panopoulos, N. Blockchain integration in the era of industrial metaverse. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 1353.

- Gil, R.M.; Gutiérrez-Ujaque, D.; Teixidó, M. Analyzing the metaverse: Computer games, blockchain, and 21st-century challenge. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction 2024, 40, 6758–6775.

- Huynh-The, T.; Gadekallu, T.R.; Wang, W.; Yenduri, G.; Ranaweera, P.; Pham, Q.V.; da Costa, D.B.; Liyanage, M. Blockchain for the metaverse: A Review. Future Generation Computer Systems 2023, 143, 401–419. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.T.; Hoang, D.T.; Nguyen, D.N.; Dutkiewicz, E. Metachain: A novel blockchain-based framework for metaverse applications. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 95th Vehicular Technology Conference:(VTC2022-Spring). IEEE, 2022, pp. 1–5.

- Duan, H.; Li, J.; Fan, S.; Lin, Z.; Wu, X.; Cai, W. Metaverse for Social Good: A University Campus Prototype. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Multimedia (MM ’21), New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 153–161. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhu, M.; Chen, X.; Liu, R.; Ge, J.; Song, Y.; Yu, G. The application of metaverse in healthcare. Frontiers in Public Health 2024, 12. Section: Digital Public Health, . [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Abdullah.; Armand, T.P.T.; Athar, A.; Hussain, A.; Ali, M.; Yaseen, M.; Joo, M.I.; Kim, H.C. Metaverse in healthcare integrated with explainable AI and blockchain: enabling immersiveness, ensuring trust, and providing patient data security. Sensors 2023, 23, 565.

- Karunarathne, L.; Ganesan, S.; Somasiri, N.; Pokhrel, S. Navigating the Future: Blockchain-based Metaverse in Education. Journal of Information Technology and Digital World 2024, 6, 373–387.

- Awan, K.A.; Din, I.U.; Almogren, A.S.; Seo-Kim, B. Blockchain-Based Trust Management for Virtual Entities in the Metaverse: A Model for Avatar and Virtual Organization Interactions. IEEE Access 2023, pp. 1–1. Published January 2023, . [CrossRef]

- Awan, K.A.; Ud Din, I.; Almogren, A.; Kim, B.S. Enhancing Performance and Security in the Metaverse: Latency Reduction Using Trust and Reputation Management. Electronics 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Tu, Z.; Zhou, H.; Li, K.; Song, H.; Yang, Y. A Blockchain-based Trust and Reputation Model with Dynamic Evaluation Mechanism for IoT. Computer Networks 2022, 218, 109404. [CrossRef]

- Xia, P.; Li, J.; Shi, L.; Cao, B.; Tan, W.; Weng, J.; Liu, Y.; Han, Z. A Reputation-Aided Lightweight Consensus Service Framework for Multi-Chain Metaverse. IEEE Network 2024, 38, 201–210. [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, M.F.; Mohtasin, G.; Subhan, M.; Tuli, E.; Kim, D.S.; Lee, J.M. Meta-Governance: Blockchain-Driven Metaverse Platform for Mitigating Misbehavior Using Smart Contract and AI. IEEE Transactions on Network and Service Management 2024, PP, 1–1. [CrossRef]

- Dimitriou, T. Decentralized reputation. Cryptology ePrint Archive, Paper 2020/761, 2020.

- Baccour, E.; Erbad, A.; Mohamed, A.; Hamdi, M.; Guizani, M. A Blockchain-Based Reliable Federated Meta-Learning for Metaverse: A Dual Game Framework. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2024, 11, 22697–22715. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Gao, Z.; Du, H.; Niyato, D.; Kang, J.; Xiong, Z.; Zheng, Z. Blockchain-Based Efficient and Trustworthy AIGC Services in Metaverse. IEEE Transactions on Services Computing 2024, 17, 2067–2079. [CrossRef]

- Kharvi, P.L. A Design Science Framework for Measuring Trust and Security in the Metaverse Space: A Holistic Approach to Digital Trustworthiness. Doctor of science in cybersecurity dissertation, Marymount University, College of Business, Innovation, Leadership, and Technology, 2025. Committee: Andrew Hall (Chair), Nathan Green, Susan Conrad, Glenn Robertson (External Reviewer). Dean: Anne Magro.

- Truong, V.T.; Le, H.D.; Le, L.B. Trust-Free Blockchain Framework for AI-Generated Content Trading and Management in Metaverse. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 41815–41828. Received 15 February 2024, accepted 8 March 2024, published 18 March 2024, current version 22 March 2024, . [CrossRef]

- Ud Din, I.; Habib Khan, K.; Almogren, A.; Zareei, M.; Arturo Pérez Díaz, J. Securing the Metaverse: A Blockchain-Enabled Zero-Trust Architecture for Virtual Environments. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 92337–92347. [CrossRef]

- Ghirmai, S.; Mebrahtom, D.; Aloqaily, M.; Guizani, M.; Debbah, M. Self-Sovereign Identity for Trust and Interoperability in the Metaverse, 2023, [arXiv:cs.CR/2303.00422].

- Ohlhaver, P.; Weyl, E.G.; Buterin, V. Decentralized Society: Finding Web3’s Soul. Technical Report 4105763, SSRN Electronic Journal, 2022. Posted: 11 May 2022; Last revised: 6 Feb 2024.

- Song, X.; Xu, G.; Huang, Y. A Fuzzy AHP-based trust management mechanism for self-sovereign identity in the metaverse. Applied Soft Computing 2025, 174, 112994. [CrossRef]

- Patwe, S.; Mane, S.B. Blockchain-enabled secure and interoperable authentication scheme for metaverse environments. Future Internet 2024, 16, 166.

- Mebrahtom, D.; Hadish, S.; Sbhatu, A.; Aloqaily, M.; Guizani, M. Trust But Verify - Blockchain-Empowered Decentralized Authentication Schema on the Metaverse: A Self-Sovereign Identity Approach. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Intelligent Metaverse Technologies & Applications (iMETA), 2023, pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Gebre, D.; Hadish, S.; Sbhatu, A.; Aloqaily, M.; Guizani, M. Establishing Trust and Security in Decentralized Metaverse: A Web 3.0 Approach. ACM Transactions on Multimedia Computing, Communications, and Applications 2024, 20, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Ling, A.; Butakov, S. Trust framework for self-sovereign identity in metaverse healthcare applications. Data Science and Management 2024, 7, 304–313. Open Access; retrieved via DOAJ.

- Lotfi, I.; Qaraqe, M.; Ghrayeb, A.; Niyato, D. VMGuard: Reputation-Based Incentive Mechanism for Poisoning Attack Detection in Vehicular Metaverse. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2025, 74, 10255–10267. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Kong, L.; Min, X.; Zhang, B. DareChain: A Blockchain-Based Trusted Collaborative Network Infrastructure for Metaverse. International Journal of Crowd Science 2023. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Feng, J.; Wu, C.; Chen, C.; Pei, Q. Reputation management for consensus mechanism in vehicular edge metaverse. IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications 2023, 42, 919–932.

- Awan, K.A.; Ud Din, I.; Almogren, A.; Rodrigues, J.J.P.C. QSTMF: Quantum-Secured Trust Management Framework for VANETs in Web 3.0 and Metaverse. ACM Trans. Auton. Adapt. Syst. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Kuru, K.; Kuru, K. Blockchain-Based Decentralised Privacy-Preserving Machine Learning Authentication and Verification With Immersive Devices in the Urban Metaverse Ecosystem. Preprints. https://doi. org/10.20944/preprints202402 2024, 317, v1.

- Cao, Y.; Cao, J.; Cui, Z.; Bai, D.; Zhang, M.; Wen, L. PolyTwin: Edge Blockchain-empowered Trustworthy Digital Twin Network for Metaverse. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Metaverse Computing, Networking, and Applications (MetaCom), 2024, pp. 81–88. [CrossRef]

- Islam, S. Trust in digital asset transactions in a web 3 based metaverse. Master’s thesis, OULU Business School, University of OULU, 2023.

- Civic Technologies, Inc.. Civic Whitepaper: A Secure Identity Ecosystem. https://www.civic.com/, 2021. Accessed: 2025-06-17.

- Chainlink Labs. Chainlink 2.0: Next Steps in the Evolution of Decentralized Oracle Networks. https://research.chain.link/whitepaper-v2.pdf, 2021. Accessed: 2025-06-17.

- Vijitha, S.; Anandan, R. Blockchain-based decentralized identifier in metaverse environment for secure and privacy-preserving authentication with improved key management and cryptosystem. Peer-to-Peer Networking and Applications 2025, 18. Received: 05 April 2024; Accepted: 13 May 2025; Published: 12 June 2025, . [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Cao, J.; Bai, D.; Wen, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, R. MAP the Blockchain World: A Trustless and Scalable Blockchain Interoperability Protocol for Cross-chain Applications, 2024, [arXiv:cs.CR/2411.00422].

- Ding, Y.; Huang, W.; Liang, H.; Wang, Y.; Yang, C.; Wang, H. A Fast Cross-Chain Protocol Based on Trusted Notary Group for Metaverse. International Journal of Network Management 2025, 35, e2302, [https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/nem.2302]. e2302 nem.2302. [CrossRef]

- Kausar, F.; Senan, F.M.; Asif, H.M.; Raahemifar, K. 6G technology and taxonomy of attacks on blockchain technology. Alexandria Engineering Journal 2022, 61, 4295–4306.

- Hameed, K.; Barika, M.; Garg, S.; Amin, M.B.; Kang, B. A taxonomy study on securing Blockchain-based Industrial applications: An overview, application perspectives, requirements, attacks, countermeasures, and open issues. Journal of Industrial Information Integration 2022, 26, 100312.

- Ferrag, M.A.; Derdour, M.; Mukherjee, M.; Derhab, A.; Maglaras, L.; Janicke, H. Blockchain technologies for the internet of things: Research issues and challenges. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2018, 6, 2188–2204.

- Garg, K. Digital identities in the metaverse: Privacy, security, and user authentication in virtual financial systems. International Journal of Financial Engineering 2024, 11, 2442009.

- OpenSea: NFT Marketplace. https://opensea.io/. Accessed: 2025-06-23.

- Liu, W.; Cao, B.; Peng, M.; Li, B. Distributed and parallel blockchain: Towards a multi-chain system with enhanced security. IEEE Transactions on Dependable and Secure Computing 2024.

- Lin, Q.; Gu, B.; Nawab, F. RollStore: Hybrid Onchain-Offchain Data Indexing for Blockchain Applications. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2024.

- Kausar, F.; Sadiq, M.A.K.; Asif, H.M., Convergence of Blockchain in IoT Applications for Heterogeneous Networks. In Real-Time Intelligence for Heterogeneous Networks: Applications, Challenges, and Scenarios in IoT HetNets; Al-Turjman, F., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 71–86. [CrossRef]

- Hemphill, T.A. The ‘metaverse’and the challenge of responsible standards development. Journal of Responsible Innovation 2023, 10, 2243121.

- Trust Over IP Foundation. Trust Over IP Foundation, 2025. Accessed: 2025-06-30.

- Roblox Corporation. Roblox, 2025. Accessed: 2025-06-30.

- Epic Games. Fortnite, 2025. Accessed: 2025-06-30.

- Fiege, U.; Fiat, A.; Shamir, A. Zero knowledge proofs of identity. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the nineteenth annual ACM symposium on Theory of computing, 1987, pp. 210–217.

| Scheme (Year) | Mechanism Type | Blockchain Platform | Architecture | Target Context | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trust-based Metaverse Framework (2023) | Score-based reputation (PoT consensus) | Assumed permissionless (Ethereum-like) | Mostly on-chain (smart contracts + monitoring) | General metaverse (resource sharing, VR/AR) | [28] |

| DEM-BTRM IoT Trust Model (2022) | Score-based reputation + decay | Permissioned (Hyperledger Fabric prototype) | Hybrid (off-chain calc, on-chain storage) | IoT/Metaverse crossover (trust in IoT data) | [29] |

| Rep-aided Consensus (2024) | Score-based reputation (weighted consensus) | Multi-chain Metaverse (sharded chains) | On-chain integrated (consensus protocol level) | Blockchain infrastructure for metaverse | [30] |

| SSI Web3 Trust (2024) | Credential-based trust (SSI, DIDs) | Permissionless (Ethereum smart contracts) | Hybrid (off-chain wallet + on-chain verify) | Cross-platform user identity & auth | [38] |

| Fuzzy AHP Trust (SSI-based) (2025) | Hybrid score (multi-factor fuzzy) | Not specified (conceptual, any chain) | Hybrid (compute off-chain, publish on-chain) | Metaverse digital identity reputation | [40] |

| Trustless Architecture (2023) | Local trust groups (scores per group) | Not specified (generic blockchain layer) | Hybrid (blockchain + off-chain enclaves) | General metaverse (resource & security mgmt) | [14] |

| VMGuard Vehicular (2024) | Score-based reputation (feedback loop) | Blockchain not explicitly used; possible extension | Off-chain currently (could use blockchain log) | Vehicular metaverse (IoV data integrity) | [45] |

| Soulbound Tokens (2022) | Token-based reputation (non-transferable) | Ethereum and others (concept level) | On-chain tokens (issued via smart contract) | Web3 social trust (metaverse credentials) | [39] |

| DareChain (2023) | Collaborative multi-chain | Permissionless multi-chain | On-chain parallel consensus | Enterprise metaverse (govt, finance) | [46] |

| Blockchain SSI Auth (2024) | Credential-based (SSI) | Ethereum | Hybrid (wallet + smart contract) | Cross-platform user authentication | [41] |

| DPPML Authentication (2024) | Privacy-preserving ML-based | Conceptual urban metaverse | Hybrid (FL + blockchain) | Urban metaverse authentication | [49] |

| Vehicular Trust Consensus (2024) | Score-based PBFT consensus | Permissioned PBFT | Hybrid (off-chain rep/on-chain PBFT) | Vehicular edge metaverse | [47] |

| DID-Based Metaverse Authentication (2025) | Credential-based (DID + ILWKM-CS crypto) | Not specified (any DID-enabled chain) | Hybrid: DID issuance off-chain, login/auth proofs on-chain | E-learning metaverse – secure avatar login | [54] |

| Trust Framework for SSI (2024) | Credential-based (medical SSI) | Permissioned/private healthcare chain | Hybrid: patient/doctor credentials off-chain; smart-contract checks on-chain | Secure tele-medicine VR hospital scenarios | [44] |

| MetaTrade (2024) | Blockchain DAM (escrow-based) | Ethereum (EVM-compatible) | On-chain (smart contracts) | AI-generated content trading | [36] |

| Decentralized SSI Trust Framework (2024) | Credential-based (SSI wallet + verifiable credentials) | Ethereum smart contracts | Hybrid: mobile SSI wallet & dApp off-chain; auth proofs on-chain | Cross-domain avatar authentication & access control | [43] |

| QSTMF (2025) | Quantum-secured trust + blockchain reputation | Consortium chain + quantum cryptography | Hybrid (on-chain/off-chain/quantum) | Vehicular metaverse (Web 3.0/VANETs) | [48] |

| MAP (2024) | Trustless cross-chain interoperability (relay chain + zk-SNARK light clients) | Multi-chain; Ethereum; MAP relay chain | Decentralized, non-custodial, scalable | Web 3.0/metaverse; DeFi; NFTs | [55] |

| Meta-Learning (2024) | Federated meta-learning with blockchain-based reputation and dual-game incentives | Custom blockchain (smart contract) | Decentralized; transparent; incentive-aligned (Stackelberg/coalition games) | Metaverse (AI service, avatar reputation) | [33] |

| PolyTwin (2024) | Proof-of-Consistency for DTs using edge AI + blockchain | Private/consortium blockchain among edge clusters | Edge-AI + blockchain; on-chain validation | Digital twins (PolyCampus, PolyExchange) | [50] |

| AI Generated Content (2024) | Blockchain-trustworthy AIGC with semantic comm + smart contracts | Consortium blockchain | Decentralized; verifiable; incentive-aligned (Stackelberg, IRM) | Metaverse (AIGC, personalized content) | [34] |

| Trusted Notary Group Cross-Chain (2024) | Fast cross-chain via trusted notary committee protocol | Multi-chain; consortium/permissioned | Notary group–based; semi-decentralized; high-throughput | Asset/data transfer; cross-domain interop | [56] |

| Blockchain-Enabled Zero-Trust Architecture (2024) | Collaborative infrastructure (zero-trust model) | General (EVM-compatible or similar) | Hybrid (on-chain + off-chain) | General metaverse (virtual environment security) | [37] |

| Scheme (Reference) | Sybil | Collusion | Whitewashing | Impersonation | Asset | Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| / ID | Fraud | Poisoning | ||||

| SSI-based interoperable authentication [41] | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Soulbound-Token (SBT) credential system [39] | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Credential-based DID attestation [42] | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Reputation-driven voting [27] | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| Fuzzy reputation with decay [40] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Smart-contract escrow & provenance [61] | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| DEM-BTRM [29] | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Sybil-resistant consensus [30] | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Local-trust groups [14] | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| VMGuard [45] | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| DareChain [46] | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| DPPML Auth [49] | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| ILWKM-CS [54] | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| SSI (medical) [44] | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Trust-aware PBFT [62] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| MetaTrade [36] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| SSI Trust Framework [43] | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Blockchain-Enabled Zero-Trust [37] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Scheme | Security (Attack Resilience) | Scalability (Performance) | Privacy (Data Exposure) | Interoperability (Cross-platform) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TrustMgmt [27] | High – multi-attack resistant | Medium – public chain (some optimizations) | Low – on-chain data visible | Low – platform-specific (Ethereum only) |

| PerfTrust [28] | Medium – specific threat focus | High – custom blockchain consensus (low latency) | Low – no privacy features | Low – platform-specific (private chain) |

| MetaGov [31] | Medium – stops harassment but Sybils possible | High – permissioned chain real-time AI | Medium – private chain logs identifiable | Low – tied to one platform (not portable) |

| PrivRep [32] | High – Sybil/whitewash proof | Low – heavy crypto public chain overhead | High – strong anonymity | High – user-centric shareable token |

| DEM-BTRM [29] | High – multiple attack mitigation via dynamic evaluations | High – permissioned blockchain efficient batching | Medium – partially identifiable transaction data | Medium – potential for multi-chain support |

| RepConsensus[30] | High – Sybil-resistant via reputation-weighted consensus | High – multi-chain sharded approach | Medium – data visible across shards | High – cross-chain reputation portability |

| LocalTrust [14] | Medium – local group trust reduces widespread attacks | High – scalable via local computations | High – local trust not globally visible | Medium – dependent on cross-group trust bridges |

| VMGuard [45] | High – data poisoning protection via reputation | High – regional feedback loops scale efficiently | Medium – vehicle data logs identifiable | Medium – city-wide application interoperability |

| DareChain [46] | High – attack resistant via parallel consensus | High – parallel chains increase throughput | High – data obfuscation layers | High – designed for enterprise interoperability |

| DPPML Auth [49] | High – impersonation protection via federated learning | Medium – federated computation scales linearly | High – privacy via federated learning | Medium – urban metaverse focused |

| Vehicular PBFT[62] | High – Sybil and collusion-resistant via PBFT | Medium – limited by PBFT nodes (<100 nodes) | Medium – data partially identifiable | Medium – edge-specific interoperability |

| SSI Trust Framework [44] | Medium – strict credential checks in healthcare | Medium – permissioned ledger fits hospital workloads | Very High – patient-driven consent | Medium – domain-specific but standards-compliant |

| ILWKM-CS [54] | High – ILWKM-CS mutual auth | Medium – lightweight crypto; global scale not yet measured | High – no personal data on-chain | Low – built for one e-learning metaverse |

| MetaTrade [36] | High – fraud resistance via smart contract escrow | Medium – blockchain dependent transaction speed | Medium – transaction details visible on-chain | High – portable digital asset standards |

| ZeroTrust-BC Framework [37] | High – multi-vector attack mitigation using blockchain-based zero-trust | High – scalable with fast response and low overhead | Medium – audit trail on-chain with strong access control | Medium – platform-agnostic design, not cross-chain tested |

| Challenge | Mapped Solutions |

|---|---|

| Cross-platform portability | • Token and credential standards (VCs, DIDs) • Cross-chain bridges and oracles |

| Privacy-preserving computation | • Zero-knowledge proofs (SNARKs/STARKs) • Differential privacy for analytics |

| Governance & fairness | • Token/credential standards for voting eligibility • DAO-based parameter voting and auditability |

| Real-time updates | • Real-time off-chain caches • Layer-2 rollups (optimistic/ZK) |

| Sybil resistance vs. openness | • Zero-knowledge proofs for eligibility • Proof-of-personhood options (privacy-preserving) |

| Data integrity & false inputs | • AI fraud/forgery filters at the edge • On-chain audit trails and provenance |

| Massive-scale performance | • Cross-chain bridges & oracles for load isolation • Layer-2 rollups; real-time off-chain caches |

| User experience & transparency | • On-chain audit trails surfaced in UX • Progressive-disclosure interfaces |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).